PROGRAM NOTES

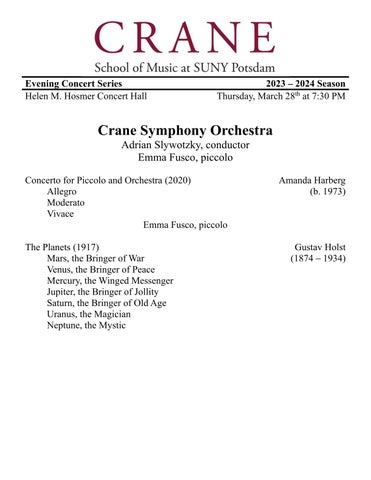

Concerto for Piccolo and Orchestra (2020) Amanda Harberg

Every woodwind has a unique musical personality. Born from a military flute in the middle ages, the piccolo, the highest instrument in the orchestra, is commonly associated with a piercing sound that can penetrate through an entire mighty orchestra.

Due to its very high register, the piccolo’s solo repertoire is quite limited.

When Regina Helcher Yost first approached me about commissioning a piece for piccolo and piano, the challenge seemed daunting. How was I supposed to come up with an effective recital piece for this extreme little instrument?

Each time I write for a new instrument, I strive to connect with what makes that particular instrument unique. What kind of music will make the instrument sparkle and come to life? What kind of material would be most satisfying to play?

For me, the key to unlocking the potential and the beauty of the piccolo is to explore its haunting and expressive lower register and to embrace its singing middle range. I only use the high register when structurally necessary, and try not to stay there for very long. Besides its singing qualities, the piccolo is also remarkably agile and capable of exciting virtuosity.

My Piccolo Concerto was born out of two consortium/crowd-sourcing commissions. It began as a Sonata for Piccolo and Piano, commissioned by Regina Helcher Yost, who spearheaded a group of 23 distinguished performers who co-commissioned the sonata, and premiered the piece in 2018.

Erica Peel, piccoloist of the Philadelphia Orchestra, and I became friends in 2019. Erica has given me great inspiration throughout our numerous collaborations. In 2020, she asked if I would compose a concerto that she would premiere at the 2020 National Flute Convention’s Gala Concerto concert. I suggested orchestrating the sonata, and we agreed that the piece would lend itself particularly well to an orchestrated and expanded concerto version.

When Erica commissioned me to transform the sonata into a concerto, we agreed that it would make most sense to use a string orchestra plus harp and percussion. Afull orchestra would likely overshadow the piccolo in terms of balance, whereas a string orchestra would act as the perfect foil to the piccolo’s metallic brilliance. Erica had many great ideas for how to push the piccolo to new heights in the last movement. She even figured out how to channel her inner Jethro Tull through singing and playing simultaneously during the rock-and-roll influenced last movement. We had many happy moments of brainstorming together throughout the orchestration process.

Erica, like Regina, put together a fundraising campaign to help support my work on this project. Unfortunately, like most live events around the world, the 2020 convention was canceled because of Covid-19. But as some doors temporarily closed, others happily opened, and the Philadelphia Orchestra scheduled the premiere of my concerto for their Digital Stage series.

Commissioning is invaluable to the continuation of our art. Without Regina Helcher Yost’s initiative in putting together the sonata consortium, and without Erica Peel envisioning the concerto version, and without the generous support of the piccolo community and friends, I would not have discovered this music inside myself. I am endlessly grateful to everyone who supported me in creating this work.

Note by the Composer

Emma Fusco is a junior Flute Performance and Music Education double major from Poughkeepsie, NY. She is the first prize winner of the 2023 Crane Concerto Competition. Emma has performed with the Crane Symphony Orchestra, Wind Ensemble, Flute Ensemble, WestAfrican Drum and Dance Ensemble, and Irish Ensemble. She has also represented the WoodwindArea for the Crane Student Honors Recital. In addition to her Crane ensemble appearances, Emma has performed as piccoloist with both the Orchestra of Northern New York and the Northern Symphonic Winds.

Currently, Emma is the President of the Crane Collegiate NAfME chapter, and she is a member of the Pi Kappa Lambda Music Honor Society. Emma remains active as a peer tutor and a private flute instructor in the North Country. She is also a SUNY Potsdam Presidential Scholar with research focusing on the representation of Indigenous andAmerican history through the development of western flute practices. Emma would like to thank her parents and Nana for their

unwavering support, her private teacher and the educators who have inspired her along her musical journey, Dr. Brian Dunbar and Dr. Keilor Kastella for their guidance and dedication, and the Crane Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Dr.Adrian Slywotzky for this opportunity.

The Planets (1917) Gustav Holst

Gustav Holst had an insatiably curious intellect, and he responded to a remarkable variety of interests and inspirations. In his twenties, for example, he became interested in the Hindu pantheon and Indian literature and, frustrated by the lack of good English translations of Sanskrit texts, he took up study of the language and ultimately translated some 30 Sanskrit hymns himself.

In 1913 Holst’s interest turned to astrology, and he began work on The Planets soon thereafter. It took Holst two years to complete the piece, working on it during scraps of free time on weekends and vacations while he juggled two demanding teaching jobs. Holst owned a book titled What is a Horoscope and How is it Cast?, and he made a hobby of casting horoscopes himself. Thus the individual movements of this suite are inspired not by the gods whose names they bear, but by Holst’s study of human personalities and behaviors as influenced by the motion of the planets.

The suite generally follows the order of the planets moving outward from the sun, but by starting with Mars, Holst went out of order. Mars is relentless and violent, but this movement isn’t only about war and aggression it is also the turbulent genesis of the whole suite. In the beginning of the movement, as an ominous melody gradually evolves above rhythmic primordial rumbling, we seem to be witnessing the creation of a new world.

Venus appears as the antithesis of Mars cool, quiet, spare. The music begins with a simple rising melody played by a single horn and answered by a choir of woodwinds. Harps, flutes and horns introduce a stately walking figure that will recur throughout the movement. Asoulful arpeggio played by the cellos opens the door to more overtly emotional expression, culminating in a melody played at first by a single violin but then taken up by all the violins.

Composed in the age of the telephone and telegraph, Mercury nevertheless seems to evoke a more modern conception of communication and the flow of information, with bits of data in the form of electrical impulses jumping across

circuits, or synapses within the human machine. Tiny musical fragments flit across the orchestra from one instrument to another, tracing scales and arpeggios that switch rapidly between the keys of B-flat and E. A single violin introduces a simple six-bar melody this is a message that will be repeated eleven times altogether, each time by new voices and with a new harmonization.

Although the melodies in Jupiter seem uncannily familiar, as though we’ve heard them all somewhere before, Holst wrote that the music does not come from a specific source rather, it is “the musical embodiment of ceremonial jollity.” The movement captures a variety of celebratory moods: an exuberant outpouring, a raucous dance, a hymn.

Saturn marks the passage of time with a harmony that rises and falls regularly, like slow breathing. The basses introduce a melody that moves slowly and unfolds gradually. The music intensifies over time, and ultimately the “breathing” figure is transformed into a fast, urgent pulsation marked by the tolling of bells. After this urgency dissipates, the bass melody returns; it is transported to higher and higher registers as the harmony brightens, allowing the movement to close in a mood of beatific acceptance. Saturn was Holst’s favorite movement.

According to What is a Horoscope, people affected by Uranus’s “adverse and material” side can turn “eccentric, strange and erratic.” This movement is the perfect illustration, with its angular melodies, gleefully bizarre harmonies, and conflicting meters layered on top of each other. The mischief culminates in a devilish jig.

Neptune returns to the 5/4 time signature in which Mars began the suite, but the atmosphere could not be more different. We have traveled to the farthest reaches of the solar system. If Mars captured a moment of creation, Neptune is our departure from that creation we float away into the ethereal void, guided by mysterious celestial voices.