THE NEW CRANBROOKIAN

Introducing Cranbrook’s student-run magazine: explore a collection of articles by students and interviews with alumni and public figures, alongside photos and artwork.

Founded and edited by sixth-form students Gemma Brassley, Annabelle Castro-Edwards and Eve Morgan, The New Cranbrookian is a celebration of the writing and creativity of Cranbrook’s students.

conducted by

Additional photography/artwork [except headshots]

Cover illustrations by Eve Morgan and Gemma Brassley

Leading the Far-Right - Gemma Brassley

Interview with Jacqueline Winspear

British Farming: We Reap What We Sow - Annabelle Castro-Edwards

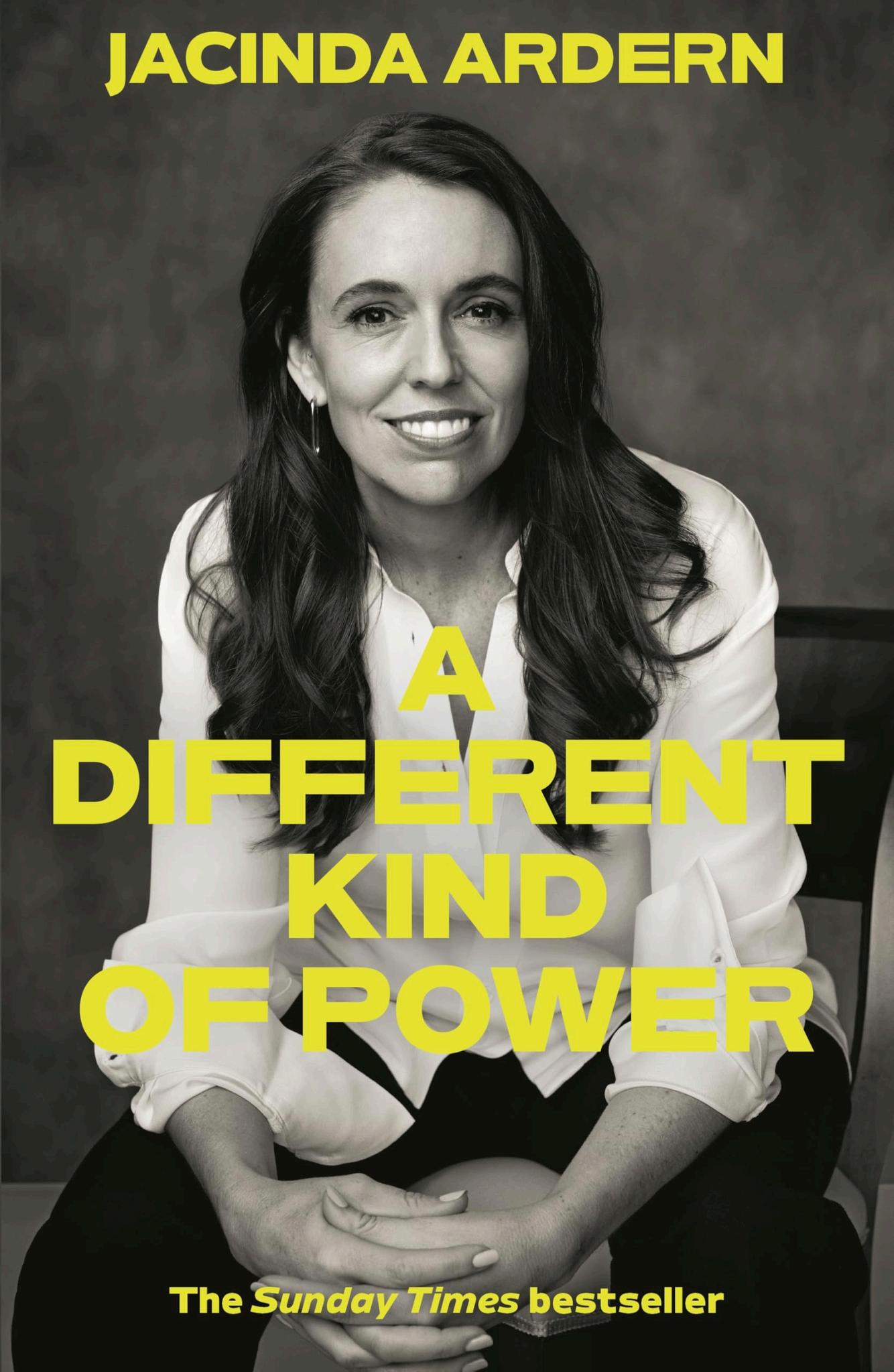

Book Review: A Different Kind of Power - Gemma Brassley

Jacinda Ardern on Imposter Syndrome

Benjamin Greaves-Neal: Filmmaker

The Crane’s Brook: Lessons from the Medieval Past - Dr Michael Warren

The Beatles’ Cultural Impact - Florrie Martin

South Africa’s Eastern Cape: Wildlife Photography - Rachel & Matthew Bright

Make Athens Great Again - Eve Morgan

Francesca Read-Cutting: Senior Marine Biologist

Trump: An Unprecedented President? - Mr Young Min

World War 1 & Canadian Identity - Lucinda Hunter

Olivia Dean: Daily Mail Journalist

From Waste to Warmth: Reusing Computer Heat - Rowan Smith

Gender Quotas in Politics: Tokenism or Real Progress? - Lucy Wells

Mary Tudor: A Microcosm of Women in Power - Aurelia King

Toni Brodelle: Parliamentary Spokesperson

Gemma Brassley

In recent years, Western Europe has witnessed a sharp rise in support for far-right political parties. Given their associations with misogyny and traditional patriarchal systems, it may come as a surprise that many of the most powerful figures leading these movements are women. Marine Le Pen, Alice Weidel, and Giorgia Meloni are all key players within their respective parties in France, Germany, and Italy: Le Pen as the former president of the National Rally, Weidel as co-chair of Alternative for Germany (AfD), and Meloni as Prime Minister of Italy and leader of the ironically named ‘Brothers of Italy’ party. So, how can women thrive in spaces that are often perceived as deeply anti-feminist?

To answer this question, it is first necessary to establish what is defined as ‘feminism’. While advocacy for women’s rights can be traced back through much of human history, feminism in its modern sense emerged in late 18th-century Europe as a social and political movement dedicated to achieving equality between the sexes. It advocates for women to have the same rights, opportunities, and agency as men. Feminist movements have campaigned, and continue to campaign, for a wide range of women’s rights. These include, but are not limited to, the right to vote, work, receive fair pay, access education, own property, have equal standing within marriage, take maternity leave, access abortion, and be protected from gender-based violence and sexual assault. Yet it is precisely this vision of equality and liberation that comes into conflict with the rise of women in far-right politics

Since 2022, Giorgia Meloni has served as the Prime Minister of Italy, the first ever woman to hold the post. Ranked 3 in the Forbes list of the World's 100 Most Powerful Women in 2024, Meloni is a Catholic, and strongly conservative, appealing to traditional values through the well-known nationalist slogan ‘Dio, patria, famiglia’ or 'God, fatherland, family'. In her 2011 book We Believe, Meloni wrote: "I am a right-wing woman, and I proudly support women's issues. In recent years we have had to suffer contempt and racism by feminists. ... Perhaps as far as feminism is conceived in this way, it is more a question of ideology than of gender and substance." With headlines from left-wing British media outlets at the time of the election including “Far-right leader posted sexualised clip of herself during election campaign, favours curbs on abortion and is against ‘pink quotas’”, many critics accuse her of being ‘anti-woman’ They argue that her policies, particularly around abortion, LGBTQ+ rights, and gender roles, undermine the very freedoms feminist movements have fought for. Yet Meloni portrays her politics as a redefinition of womanhood, not one founded in liberation from traditional structures, but in the embrace of them. She positions herself as proof that women can lead without subscribing to progressive feminism, a stance that has proved extremely controversial across Italy and beyond

While Meloni's leadership centres on redefining the female position within traditionalist frameworks, Alice Weidel's presence in the AfD challenges expectations in a different way: by seemingly contradicting the extremist party’s very ideology. To cite NBC, “She has two children with a Sri Lankanborn woman, speaks Chinese and previously worked at global financial institutions an unconventional profile for the leader of a male-dominated far-right party that venerates traditional family values, fosters deep antiimmigrant sentiments and promotes populist economic policies.” With the AfD opposing gay-marriage and the expansion of laws allowing same-sex couples to adopt children, Weidel with her female partner and two adopted sons hardly seems like the ideal candidate. Furthermore, her Sri-Lankan partner, and their children divide their time between Switzerland and Berlin, providing a sharp contrast with the AfD’s hardline antiimmigration stance. This contradiction between her personal life and political ideology has sparked accusations of hypocrisy.

Indeed, in the past Weidel has referenced the importance of children being raised in a traditional one-mother, one-father families and has said that the legalisation of same-sex marriage is unimportant. This has fuelled debate as many accuse her of being opportunistic, using her identity to soften the party's image while upholding policies that undermine her own lifestyle.

Perhaps the most notorious of these figures is Marine Le Pen, convicted in March 2025 for embezzlement of EU parliament funds for her party’s own gain. Following in her father’s footsteps, Marine Le Pen rose through the ranks of France’s far-right political movement, ultimately taking the helm of the National Front (now National Rally) in 2011. The Party was founded in 1972 by her father Jean-Marie Le Pen, a holocaust denier and extremist on race and immigration Although Marine Le Pen’s ideology is less overtly radical than her father’s, her politics remain rooted in nationalism, anti-immigration sentiment, and Euroscepticism. In 2017, journalist Agnes Poirier suggested Marine Le Pen was “using her gender to give the National Front a veneer of respectability and modernity.”

In fact, this is an accusation that has been levelled at all three of the women discussed in this article Appointing a female leader can serve as a strategic move to shield the party from accusations of misogyny, and in the case of Weidel from allegations of homophobia as well. However, while such critiques may hold some weight, it would be misogynistic in itself to dismiss these women as mere ‘figureheads’; their political influence and agency extend far beyond mere symbolic representation.

So, whilst their success doesn’t signal a victory for feminism, it provides a reminder that women holding positions of authority and progressive politics don’t always go hand in hand; perhaps these figures demonstrate that shattering the glass ceiling is not, in itself, a definite victory for women

Political and social history - especially at this momentintime Europeinthe1930’scomesto mind.

Have you ever experienced or witnessed discriminationinthecreativeindustry?

Goodquestion,especiallyasI’mrespondingon thedayaleadingGuardianarticlehadthissubheader: “Bullying and harassment towards womenisstillrifewithinthecreativeindustries, according to a survey that found seven out of 10 of its female workforce had experienced toxicbehaviour.”

Another, broader interpretation of “discrimination” is “putting people in a box”whichhappensinanyindustry,howeverI’llgive a few examples of the creative world, so this answerwillbealongone-sorryaboutthat. Oneistheassumptionthatyoumustwinyour spurs for achievement to be authentic in a creative field. Writers, artists, actors and musicianscantoilforyearstryingtomakeitto the first rung of success, however, when a “creative” gains accolades with the first song, the first novel, first film or lands a prestigious award, they can often be on the sharp end of negative rhetoric from others who crave success-thatisbullyingbyanothernameand it’sdamaging Howmanytimeshavepeoplesaid (with a wink and a nudge) of actors and other creatives who experience early success, “Well, weknowhowtheygotthere!”

Annabelle Castro-Edwards

As a trading nation, the UK is heavily reliant on foreign imports We drive German cars, we drink Ethiopian coffee, we wear Indonesian clothes, and we use Californian phones. Following the massive deindustrialisation after the end of the Second World War, very few of the goods we consume are still labelled “Made in Britain”.

There is an exception to this trend; an industry rooted in a rich history of high standards and embedded in the rural way of life. Despite facing increasing foreign competition, British farming refused to die with the rest of the country’s production

Food and drink remains Britain’s largest manufacturing sector, worth £148 billion according to the NFU. It provides jobs for fourteen per cent of the nation’s workforce, yet occupies a huge seventy per cent of its land area. As a result, it is intertwined with rural life, serving as the main source of income for many families as well as holding cultural significance. Additionally, these landscapes can be preserved and protected from the ever-growing threat of development.

Sixty-one per cent of the food we consume is grown in Britain The majority of this is cereal produce; in 2023, over ninety per cent of oats, barley and wheat were domestically grown. This figure also includes seasonal fruits, such as Kentish apples and Worcestershire plums. In the summer months, such produce can be found in most of our supermarkets, and we enjoy our own beer in pubs all year round. However, this figure also represents part of a long-term decline in self-sufficiency, falling far short of the seventy-eight per cent of produce consumed in 1984 being British-grown

The remaining thirty-nine per cent of our food is imported. Although this figure includes crops that we cannot grow, such as spices and exotic vegetables, it also accounts for meat, seafood and fresh produce, the prices of which British farmers simply cannot compete with. For example, thirty per cent of our beef is imported, reaching 200,000 tonnes in 2022. Around a third of this is from Ireland, with remaining suppliers including Brazil and Australia. Whilst these foreign supplies are essential to meet demands, they often do not meet the same standards to which we produce our own beef; most notably, regulations on quality and the use of artificial hormones.

The state of our seafood consumption is even more concerning. Despite being an island nation, British waters are depleted, rendering us heavily reliant on seafood trade. 133,000 tonnes of fish products were imported in 2023; that year, only around twenty per cent of fish consumed had been caught in British waters. Large quantities of imports are from China, raising health concerns due to the presence of pollutants, antibiotics and microplastics in Chinese farmed fish Furthermore, investigations by the EJF have revealed numerous breaches of fishing and human rights laws aboard Chinese distant-water fishing vessels with direct links to UK supermarkets. Due to insufficient screening processes, we are very much in the dark about the quality of seafood we import from China.

There are undeniably benefits to consuming imported produce Many other countries are renowned for their high-quality exports, such as Norwegian fish, Irish beef, Dutch vegetables and Spanish oranges. Such trades allow us to enjoy off-season produce as well as exotic and scarce foods. They can even alleviate pressure on British production; after all, we have never been entirely self-sufficient, and it is unlikely that we ever will be.

However, there is no denying that British farming is already under internal threat. Changes to Agricultural and Business Property Relief, also known as the ‘farm tax’, means that even farms that have been in families for generations can become unviable overnight. Profits must be put towards increased taxes, leaving little room for innovation. Where there are no profits, assets must be sold, greatly limiting the ability to produce goods at prior levels.

According to FarmingUK, this has resulted in farms and rural businesses disappearing twice as quickly as they are being replaced, a particularly worrying decline. In addition to undermining individual farms and local economies, this threatens Britain’s food security as a nation, making us even more reliant on the cheap imports that already dominate the market and make it ever harder for our own produce to compete.

It is clear that the future of British food consumption rests on the endorsement of our own production. Farming is a disappearing industry If we do not continue to support our farms, the families they provide for and the high-quality goods they produce, we will succumb to a future of cheap imports of contentious quality and origin.

We will reap what we sow.

Gemma Brassley

Just one day before learning the result of the election that could make her New Zealand’s next prime minister, Jacinda Ardern sat in the bathroom of a friend’s house, clutching a pregnancy test and counting down the seconds.

The very next day, Ardern became the youngest female head of government in the world, and seven months later, she became only the second world leader ever to give birth while in office

Released in June 2025, her biography A Different Kind of Power reflects upon her journey from a young girl in the rural town of Murupara to the leader of New Zealand’s Labour Party, and prime minister. The daughter of a policeman, Ardern writes of her upbringing in the Mormon church, and her journey through politics to her self-described “unexpected” leadership.

Ardern is perhaps most well-known for the effectiveness of her leadership when dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as her compassionate handling of both the Whakaari/White Island volcanic eruption and Christchurch mosque shootings. Indeed, her responses in the aftermaths of these tragedies came to define her as a leader renowned for her empathy Through her own words, Ardern reflects upon these moments, moments when the nation could so easily have fractured, where she instead inspired unity and strength.

Considering the legacy she would like to leave behind, Ardern recalls: “I wanted to be remembered for kindness ” It is a value taught to us from infancy, celebrated in countless school assemblies, woven through religion and culture, and yet, too often, it is dismissed in politics as a sign of weakness rather than strength. Empathy and sensitivity are perceived as liabilities in leaders, incompatible with power and resilience, rather than the very qualities that demonstrate humanity.

Her response to the Christchurch terror attack was both immediate and unifying. Her words in her first address to a shocked and mourning nation, “They are New Zealanders They are us ” , seem a world away from the current political climate in the UK, where racial riots erupted on the streets of Britain this summer. Less than a month after the terrorist gunman killed 51 people, all but one member of New Zealand's Parliament voted to change gun laws. Ardern’s conclusion “That every crisis asks clearly and unequivocally for action to be taken” is a principle she demonstrated here through moralclarity and decisive reform.

Her authenticity is compelling, as she seamlessly balances reflection on serious issues with moments of humour and warmth For an international audience, it offers a wonderfully clear insight into the history, culture, and politics of New Zealand, through the lens of her personal experience and leadership. A Different Kind of Power is a great success; Ardern’s prose is a testament not only to her skill as a writer but to the enduring influence of a leader who proved that kindness and empathy are traits of strength, not weakness.

In A Different Kind of Power, Ardern reflects openly upon the quiet fear that she was never truly good enough, that she didn’t deserve to be in the roles she held or the rooms she occupied. It is a fear she recognises as imposter syndrome, one that shadowed her from childhood debates to the highest office in the country. She very kindly summarised her thoughts on this subject for The New Cranbrookian:

You hear people refer to imposter syndrome a lot. In my mind, it’s best expressed as a confidence gap. And when most people experience a feeling that they’re not quite the right person for the job, or they’re asked to do something they feel ill equipped for, then they will try and compensate. They’ll prepare. They’ll ask for advice. They’ll bring humility and an open mind to a problem. And aren’t these the kinds of responses we want from our leaders? For so long we have been told imposter syndrome is a weakness. But perhaps it’s not?

Perhaps it’s a strength.

“There’s no one pathway to a career or to happiness… life is so much more complex and stranger, madder, and better than that”

For Cranbrook alumnus Ben Greaves-Neal, filmmaking is more than a career ambition, it’s a journey that began in his teenage years and continues to shape the way he sees the world. From acting as a child, to studying at the London Film Academy during COVID, to starting his own production company, Slate 32, Ben has embraced the challenges and possibilities of life in the arts.

His journey in the film industry began at a young age: “I used to do acting as a child... I definitely shifted to the other side of the camera [and] developed a love for being behind the camera and storytelling.” At 15 years old, as a new boarding student at Cranbrook, Ben recalls “Everyone was very nice, but I was just feeling a little alone, I guess. And it was one weekend and I found in a charity shop a DVD of a movie called True Romance... I remember just putting it into my laptop and watching it and thinking… this film’s really, really speaking to me so much... it really made me think, I’d love to tell stories like this and I’d love to try and make films”

We discussed barriers to the industry, with Ben noting “I think one real discrimination is just a discrimination against young people, regardless of their backgrounds or who they are. It’s really difficult to be taken seriously... I’ve found there is quite a lot of blocks to getting things like funding, [for] people to believe that you can actually pull something off.”

Ben co-wrote and co-produced Deserters, a short film set during the First World War. “It was an amazing experience and we ended up being BAFTA eligible with it”, an incredible achievement. His next step was directing Stray Tales, “a sort of dark comedy about a messed up man’s quest to find a missing cat”. Ben feels privileged to have been able to work on both of these films: “I’ve felt very lucky to have been able to have made them because they’re passion projects, really.”

Asked what advice he’d give to his teenage self, Ben offers: “If you have an idea that you’re passionate about, be it creative or be it practical or political, or just even travelling, hold on to that idea. Don’t hold on to the way that it’s going to come about. Just be flexible.”

He draws from his childhood passion to give him inspiration and ambition for the future, keeping one dream in particular close to heart: “My childhood dream one day would be… to take over Doctor Who one day… It’s important to hold on to those childhood dreams and [it’s] what keeps me going.”

Dr Michael Warren

Cranbrook has a rich and fascinating history which is a distinct part of many residents’ pride in their home town. The very first Cranbrook was a tiny site of importance for rural communities leading their swine from the coast into woodland pasture locations in the once very substantial Weald. There was a chattering stream in a clearing. A brook. And there were birds. Cranes. Huge, resplendent birds with feathery tail-bustles, the biggest wingspan of any bird in Britain, standing over a metre tall, with a song so resonant it rings like the sound of time itself.

Cranes aren’t the only creatures to appear in our place-names. Far from it; there are many other birds (owls, woodpeckers, eagles, ravens, sparrows, bittern … ), as well as mammals, insects, fish, flowers and trees the whole spectrum of Britain’s flora and fauna. What all this points to, besides revealing the astonishing natural history of our ancient lands, is the profoundly integrated relationships our ancestors had with their environments

People named places after the natural world because they understood how much they depended upon it and readily accepted that they were utterly a part of that world. We stand to learn something very important from those old ways.

The worrying problem in the twenty-first century is that far too many of us take as ‘fact’ what is actually a fundamental error the belief that modern humans are separate to everything else. We are not. We’ve forgotten a crucial truth in our pursuit of ‘progress’, a pursuit that has slowly and insidiously led with escalating speed in the twenty-first century to ever-poorer mental health because there has never been a time in our history when we have been more introverted and disconnected from the physicalities and vitalities of the real world, which is to say, nature.

Little wonder, then, that the most recent survey by the Office for National Statistics reported that around half of UK citizens feel no connection to their neighbourhoods, or that the very latest research on this topic states that people’s connection to nature has declined by 60% since 1800 (no coincidence— the beginning of the Industrial Revolution), and that we risk a genuine ‘extinction of experience’ if we don’t look to make changes. Detachment from nature is a detachment, in the end, from ourselves.

Think on that. Place-names, plain on road signs all around but which most of us hardly ever give a second thought to, as a guide to better living, reminding us that nature is not just wonderful, but essential to everything we are.

My book, The Cuckoo’s Lea, explores these lessons in its journeys around Britain. We must find meaning in place again, through birds and other wild lives, if we are to ensure our emotional and physical survival.

We need these spirits of place.

Florrie Martin

The Beatles are said to be the greatest band of all time. And when people say it, they rarely treat it as an opinion, it’s delivered as fact, just as Muhammed Ali is the greatest boxer, or Shakespeare is the greatest playwright. With 19 number one albums, 20 chart-topping singles, an estimated 600 million albums sold, and many prestigious awards collected, The Beatles were undoubtedly commercially successful. But in my view, their most important achievement isn’t about charts or sales.

Let’s rewind to February 1964. The Beatles arrived in the USA and appeared on the Ed Sullivan show during the thick of their first American Tour. It was viewed by a recordbreaking 73 million people across the country a number unheard of for the time

For many, this would be the first time that they had heard any British music before, and thus began a movement of music called British Invasion. This movement would be joined by a number of musical acts, such as The Rolling Stones, The Who, The Kinks, The Animals, The Yardbirds and many others too. The American audiences were enchanted by the music, and what they were seeing on their television screens was new to them too. The sound was fresh. The look was different. The impact? Immediate.

Within a week, “I Want To Hold Your Hand” topped the charts. Seven weeks later, it was replaced by another song of theirs, “She Loves You”. But beyond the music, The Beatles saw things others were ignoring. Amidst the growing tensions of the Civil Rights movement, they noticed racial segregation at their shows. Black audience members were placed at the back. Separate entrances were used. And so, in response, The Beatles made a bold move: they refused to perform for segregated audiences. It was i en into their contract with no ptions. In fact, The Beatles were almost ped from playing a large concert in or Bowl, Jacksonville due to their policy. ed by John Lennon, the band stood gly against the venue organisers before would allow it to go ahead. For a British in 1960s America, this was more than ement. It was an act of protest.

impact didn’t stop there. The Beatles ined masculinity Their influence ed down to bands like The Ramones Led Zeppelin, whose own style and of rebellion were direct echoes of what Beatles began. Their self-written songs expressive, gentle, romantic, and ne, whereas most artists at the time other people writing their songs for , such as Elvis Presley and Frank ra.

And then there was worldwide “Beatlemania”, a phrase coined by a Scottish promoter named Andi Lothian. The Beatles' appeal to young girls, the main driving force behind the phenomenon, also contributed to dismantling the crushing gender norms. They were able to scream at concerts, expressing joy and desire publicly – things that were previously frowned upon. Even their music challenged these norms: they covered girl-group songs like “Please Mr. Postman” and “Baby It’s You”, an extremely unusual thing to do as a male band.

During the Vietnam War, as grim footage filled television screens, The Beatles refused to stay silent. All four members voiced their opposition to the war. They promoted peace through interviews, television appearances, and eventually their music. Lennon’s activism – most notably his ‘BedIn for Peace’ – became a powerful anti-war symbol. They weren’t politicians, but they knew the influence they held and the platform they had, so they used it.

Their alignment with 1960s popular culture deepened as the hippie movement grew. George Harrison in particular delved into Indian spirituality, studying and learning various instruments such as the sitar, tabla and tamboura with Ravi Shankar. Their music fused East and West, and it would inspire other pieces such as ‘Maker’ by The Hollies and ‘Paper Sun’ by Traffic. Songs like ‘Within You Without You’ and ‘Love You To’ carried spiritual messages through Indian instrumentation, while ‘All You Need Is Love’, broadcast live to a record-breaking 400 million people through the world’s first television link, distilled a simple, lasting truth into a global anthem

So, what would a world without The Beatles look like?

For one, countless artists – from Black Sabbath to Oasis – might never have found their voice. But more than that, the cultural landscape itself would be poorer. The Beatles helped break down barriers: between men and women, between generations, between cultures. They made it acceptable for musicians to speak on politics, to stand for what they believed in, and to imagine a better world.

We often celebrate The Beatles for their music, and rightly so. But their true legacy is bigger than a catalogue of hits, endless list of awards, and multi-platinum albums. It’s the conversations they sparked, the walls they helped to tear down, and the message they left behind: that love, unity, and peace are not just ideals – they’re actions.

And The Beatles acted.

Rachel & Matthew Bright

These incredible photographs were captured by Rachel and Matthew on their recent trip to the Eastern Cape of South Africa

Eve Morgan

Arguably, one of the most significant messages in Plato’s Republic is that the reluctant ruler is the one most suited to govern, rather than the ruler who seeks office and competes against others to attain it. To explain this idea, he presents the analogy of ‘the ship of state’. In Plato’s analogy, the current owner of the ship is less than optimal; he’s rather deaf and short sighted, with limited knowledge of naval matters; entirely unsuited to being in command. As a result, the sailors each think that they should be the one to take charge instead, despite having limited knowledge of the skills required to captain the ship. They compete for the position, but since they can’t actually prove their skill as a captain, they rely on two tactics: brute force, and persuasion, neither of which are of much use when it comes to navigation. As expected, the ship descends into anarchy, perhaps even sinks, and the voyage fails. Sound familiar? Our word ‘governor’ comes from the Greek kubernetes and Latin gubernator meaning ‘helmsman’, so perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised

In effect, what Plato is conveying with this analogy is the idea that democracy rewards those who are practiced in persuasion, not in the skills required to govern, since those who really do possess the ability to navigate a ship will spend their time developing that skill, instead of clamouring for attention. Plato could never have guessed how greatly this would apply over two thousand years later, in a world dominated by the presence of media, the most powerful tool to broadcast the image that you think will attract the greatest support. Democracy prioritises personal gain, as it fashions a position of power into something to be won, a glittering prize, which in turn creates leaders absorbed in themselves and their image, rather than the good of a community as a whole.

Unsurprisingly, Plato’s figurative sailors are corrupt; they think highly of anyone who contributes towards their gaining power, and so they reward them, calling them an ‘accomplished seaman’ and a ‘naval expert’, whilst criticising anyone who opposes them. We’d like to think this doesn’t apply to our own modern society, but the recent American election is hard to ignore. When the owner of a social media platform worth $44 Billion is given the dubious role of ‘special government employee’ in return for his support, it’s not so difficult to see what Plato was getting at

The alternative, as Plato sees it, is essentially a totalitarian state which he names Kallipolis, where a select group of the best men (evidently philosophers), are forced to take time away from their philosophising in order to govern the community. However, as has been noted frequently over the millennia following Plato’s life, there are several inherent flaws in this system, which suggest it would be ineffective when practically applied. Principally, a ruler with an apathy of ruling is not the ideal figure to take charge of a community, because in being compelled to rule against their will, their eudaimonia or ‘happiness’ will suffer, and consequently so will their ability as a leader. As well as this, a totalitarian state like Plato’s Kallipolis is essentially a breeding ground for contempt, as it removes the natural outlet for spirit and competitiveness, known to the Greeks

as thymos, which can be found in competing for office, thus risking the dangerous territory of civil war.

Undoubtedly, there are several flaws aside from this, but the main point to take away here is that while Plato may have been a great thinker, he didn’t have the practical answers to the societal problems he saw every day, as the political situation in Athens rapidly declined.

Then again, it appears that we aren’t in the greatest position to judge, when the man chosen to lead the world’s biggest superpower is a convicted felon. The suggestion of complete societal reform may be a step too far, but perhaps it would be wise to consider the necessity of some sort of change, before we find ourselves going the same way as Plato’s sailors…

From organising an animal-themed day at school to attending the United Nations Ocean Conference, Cranbrook alumna Francesca Read-Cutting’s remarkable journey is a testament to her commitment and determination. Her career in marine restoration has taken her across the world, and it all started with a teenage passion she refused to outgrow. We discussed her journey from Cranbrook corridors to international work on climate and conservation efforts.

Reflecting on her school days, Francesca remembers being told that teenage passions were just phases to “grow out of” But for her, that wasn’t true. “I think I'd give myself the advice that a lot of people can tell you that whatever you believe in as a teenager is just a quick passion moment... But now, my entire job is around marine restoration,” she says.

While at Cranbrook, she was involved with Eco-Schools and organised a successful Animal Day. At the time, it felt like “a bit of a fad,” she recollects. “Now I get to make money from that but more importantly I get to be connected with people that have those same shared values... I find that very empowering.” Her advice to current students is simple but powerful: “If you really believe in something and you’re very passionate about it, you’ll definitely find a way of finding other people that feel that way too.”

After A-Levels in History, Physics, and Maths, and Latin at AS, she wasn’t sure what was next: “I was originally looking at doing everything from linguistics to criminology to journalism.” She took two years out instead of going straight to university. “I didn't think university was going to be for me,” she says But during her travels, a scuba diving trip changed everything. “It was one of the most amazing experiences of my life. And I basically Googled, how could I make scuba diving a job?” After conducting some research this led her to marine biology, but the path into the industry wasn’t straightforward. Most university websites stated they required Biology A Level as a pre-requisite for applying to their Marine Biology course, including her preferred choice - Newcastle University However, Francesca was determined not to be blocked by a formality, deciding instead to reach out directly to a lead lecturer on Newcastle’s Marine Biology course. By demonstrating she had plenty of passion outside of academia, such as pursuing her divemaster qualification and advocating for climate positive changes at school, she was successful at securing her spot via an interview.

After completing her studies at Newcastle, she didn’t immediately find a job relating to her degree, a common experience many students can relate to. “I got a job not at all related to marine biology... but I never gave up.” She saved up to do another internship with the Global Rewilding Alliance, connecting with people involved in “incredibly inspirational projects” around the world.

Now, Francesca is working on the Ocean Justice Series, bridging social science and marine management through a collection of webinars and discussions focused on promoting equity, diversity, and inclusion within the marine and coastal sector. They work on issues such as making the industry more accessible to those from working class backgrounds, decolonising the ocean sector, and addressing the barriers faced by those with disabilities. She notes “1/4 people are disabled in the UK, which is then a massive barrier to being able to actually form a connection with the ocean, but then also advocate for it. And we're losing out on a lot of people that could be massive champions for the ocean”. However, she is hopeful that meaningful change is underway, with “amazing organisations… getting to the root of those barriers and creating massive opportunities out of them.”

Discussing boundaries, she references that sexism remains a problem in her field, though she has been lucky to work with supportive colleagues. “There are several organisations trying to tackle [sexism] like Women in Ocean Science and She Changes Ocean” she says. She believes in listening and tackling root causes, not simply punishing without understanding “If more people could just listen to the person who’s had the experience, and also meet the person who did the wrong thing with empathy, we could actually help them channel their energy in a different way.” This creates not just inclusive workplaces, but transformative ones where growth and accountability are strongly interconnected.

Having grown up in Belgium, Francesca spoke English and Flemish and understood French from a young age, an experience that shaped both her love of languages and her awareness of differences in culture. “That’s where my interest in linguistics came from. I loved Latin because I started realising these languages actually all shared a lot of very similar roots,” she explains. But more importantly, it taught her how different things can be from one place to another, and how those differences are rooted not in universal truths, but in national and local ways of thinking. “You're often being told that something has to be the way it is,” she says, “but actually in a completely different country, it just isn't like that at all.” That realisation opened up something more profound: “Why is that? What fundamentally is at the root of that? If you ask those questions, you start to see how much of our world is built on assumptions.” Understanding this is powerful. “Anything is possible, you just have to create the frameworks for it. You have to create the words for it. You have to create the language for it. And then suddenly, things don’t seem as impossible.”

For Francesca, “having it all” isn’t about chasing a high salary or a luxury lifestyle It’s about building a career that lets her work on what she loves, earn a living from it, and make a true positive impact. In doing so, she proves that changing the world might just start with refusing to let go of what matters most to you.

Challenge what feels fixed. The limits we think are real often just come from the way we've been taught to see the world.

Mr Young Min

When Trump first announced that he was running for the Republican candidacy to run as president in 2015, he said that he would be the “greatest (jobs) president that God ever created” His claims have characteristically ballooned since then. In his first address to Congress in March this year, he asserted, without references, “It has been stated by many that the first month of our presidency ... is the most successful in the history of our nation,” and that, “what makes it even more impressive is that, do you know who number two is, George Washington? How about that?”. He has certainly broken a number of records as the first president to come to power without holding any previous political or military office, as the first president with multiple criminal indictments, as the first billionaire president to serve a second term, and as the first president to win after losing the popular vote twice But how far is Trump really a president of firsts? In the presidential history of the United States, you might be surprised how many previous holders of the post can claim to have got there before him

The first president, often compared to Trump, as an unconventional, insurgent outsider is Andrew Jackson in 1828. As a man from the west, with an ordinary background (although relatively wealthy, like Trump, when he ran for president), with a frontiersman reputation who would take back the government for the ‘little guy’ from the bankers, Easterners, and urbanites who had led the country since the creation of the Republic When Newt Gingrich, a Republican supporter of Trump was asked, in a podcast, if Trump was stable enough to become president, he said “Sure, he is at least as reliable as Andrew Jackson” Jackson had first stood for election in 1824, and had won the most electoral college votes, but in a four-horse race, no one had a majority leading to Congress appointing a former president’s son John Quincy Adams Jackson, like Trump in 2020, felt that his election had been stolen by the establishment. When Jackson then handsomely won in 1828, Washington was swamped by his frontiersmen supporters to ensure he was inaugurated, taking over the White House, with the echoes of the 6 January 2021 invasion of the Capitol.

Another president that Trump, perhaps surprisingly judges himself against in greatness is Abraham Lincoln who ended slavery in the US in 1863. Trump claimed in 2024, that he himself had been “the best president for the black population since Abraham Lincoln.” But perhaps a more useful similarity lies in the divisiveness of both presidencies In 1860 the one issue that split the country was whether slavery should expand into the new territories of the west, not just over the morality of slavery, but whether the spread of slave labour to places being settled by white farmers would undermine their livelihoods. The threat in 1860 was from this “slave power” threatening the prospects of ordinary white northerners, so likewise in Trump’s messaging today, the threat of powerful forces attacking ordinary Americans that only he, not the complacent Democrats, can save Like Trump, Lincoln was seen as an untested outsider. Lincoln was a self-educated lawyer from Illinois raised on the frontier, coming to Washington to take on a complacent elite In 1854 large slave-owners were able to push through the Kansas-Nebraska Act and opened up the possibility of the spread of slave competition for white farmers. This provoked Lincoln to make a stand His election in 1860, on a minority of the popular vote from slave-free states, like Trump’s electoral college victories, lead to the secession of southern states that the provoked the Civil War

Warren G Harding, elected in 1920, also has similarities to Trump’s presidencies, in this case, as representing a break from an outward-looking, interventionist America to one of inward isolationism. Following Woodrow Wilson who had taken the US into the First World War, a war to make the world “safe for democracy”, Harding promised to change back, putting America first. The 1917 Russian Revolution abroad and the wave of violent strikes at home were seen as evidence of the threat of Communists and immigrant terrorists. He characterised the new League of Nations as conceived for “world supergovernment”. As well as immigration restrictions Harding promised tariffs and tax cuts These ideas are all echoed in Trump’s anti-immigrant policies today in his campaign against immigration – the ‘Wall’ on the Mexican boarder in his first term, and now his ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) raids in major US cities where the agency’s budget is set to expand by $150 billion. And internationally, Trump has promised to end “forever wars” of intervention He has signaled a withdrawal from cooperation with multilateral organisations such as the UN. At his address to the UN General Assembly, he questioned, “What is the purpose of the United Nations? All they seem to do is write a strongly worded letter and then never follow that letter up. It’s empty words.”

The accusation of the expansion of presidential power beyond accepted norms by Trump, is not new either. The 1968 campaign that brought Richard Nixon to power had a backdrop of war abroad in Vietnam and war at home over Black Civil Rights and sexual permissiveness. Nixon sought to fight back for the ‘great silent majority’ and restore law and order and traditional values over the domination of liberal ideas As he said in a 1968 radio address, shortly after his electoral victory, “the days of a passive Presidency belong to a simpler past… Let me be very clear about this: the next President must take an activist view of his office.” The Watergate Scandal that brought Nixon down and exemplified his excessive power was commented on by Arthur M. Schlessinger (whose book The Imperial Presidency criticised how presidents had used war-making power to unofficially extend the powers of their office) in his journal, as providing, “the climax and, I trust, denouement” of this use of power Similar to Nixon, Trump in his first inauguration coined the phrase “American carnage” to describe the inner cities as crime ridden, where ordinary people had been forgotten by the political elite To solve this, Trump sees presidential power as the solution and in his first 100 days of his second term, Trump signed 143 executive orders, more than any other president since Franklin D Roosevelt in 1933 at the start of the New Deal.

Trump is now embroiled in controversies over the application of the Alien Enemies Act 1798 to deport individuals accused of being illegal immigrants and his threat to use the 1807 Insurrection Act to empower his use of the National Guard in Democrat run cities such as Chicago

Trump is undoubtedly a consequential figure. But he is not the first to suggest that the country was in a crisis that only the president could solve through the use of extraordinary powers. He is not the first to suggest that the key to America’s greatness is for the country to concern itself with its own affairs, economy and its borders Nor is he the first to see himself as an insurgent outsider who, in spite of his own background, speaks for the common man. But whatever the 47th president of the United States claims to be, or becomes by the end of his term in office, he is not likely to be as unique or as unprecedented as he might want to think.

(Acknowledgement: I’m indebted to the series by Adam Smith – Trump: The Presidential Precedents, available on BBC Sounds)

Lucinda Hunter

As a colony of the British Empire, Canada entered the First World War known primarily for its links to Great Britain. However, by the war’s end, Canada had gained a new sense of independence.

Canadians entered the war because their motherland (England) had called for aide But another reason for joining the allies was because they had strong trading connections with England; they traded things like lumber and animal hides, amongst other products. This trade brought in a healthy profit for the Canadian government, and so the politicians in charge at the time did not want to disrupt this relationship. Canadian citizens were, at first, positive about the war, even excited. However, when the heavy death toll and struggle of war became apparent, public opinion shifted and became decidedly negative

Canada distinguished itself as a successful corps; they were known for completing missions and tasks. This reflected well on Canada’s overall image as it showed the country as being reliable and effective in critical situations, and existing as an independent nation.

Due to its geographic proximity to the United States and its historical roots in the British Empire, Canada was often identified as an underdog in popular culture, overshadowed by these world powers This was strongly disproven by Canada’s performance in the war. Despite being provided with shoddy equipment and playing secondary, supporting roles to Great Britain, the Canadian corps had major victories at Hill 70, Passchendaele, Amiens, Arras and Canal du Nord (not to mention their success at Vimy Ridge which is known as ‘The Birth of Canada’).

The Canadian soldiers were not experienced, indeed the term “citizen soldiers” was used to describe these boys and men. At the outset of the war, there were over 400,000 volunteers, however conscription started in 1917, leading to 125,000 more men joining. The total population of Canada at the time was only 8 million, compared to 46 million in Britain and 99 million in the USA. Hundreds of thousands of Candian volunteers managed to do what other nation’s armies could not, to take Vimy Ridge and to find victory in the Battle of the Somme and at Passchendaele.

Economically, Canada punched above its weight, producing over 66 million shells, and the gross national debt went from $544 million to almost $2 5 billion (1919) Canada raised approximately $660 million of this in 1918 alone.

Canada entered the First World War as a small, relatively untested dominion of the British empire. It emerged as a nation respected for its bravery, sacrifice, and effectiveness on the world stage. From the muddy trenches of Ypres to the ridges of northern France, Canadian soldiers forged a reputation out of proportion to their country’s size In doing so, Canada shed much of its underdog status and stepped forward with a clearer, prouder sense of nationhood.

She does not, however, frame rejection in a negative light. “I’ve had a lot of failures in my career, but they’ve ended me up in a good place.” Failures have not only guided Olivia’s path: they have shaped her as a person. “I definitely used to take criticism incredibly personally, because I used to value myself entirely on how academically successful I was.” In an environment pressurised by time and performance, she believes it is important to remember that criticisms are not personal. “Always believe that you are good enough,” she reiterates, “because you probably areotherwise, they wouldn’t have found you.”

“A lot of things I’ve done are down to luck,” Old Cranbrookian Olivia admits regarding her experiences within the journalism industry. “I always wanted to be a writer. I got work experience placements at national papers through other people’s parents, who were successful journalists ” She is refreshingly aware that her entrance into the industry was aided by fortunate connections and the privilege of a good education. However, she equally stresses the importance of “grabbing the bull by the horns,” as she describes her approach to taking the opportunities presented to her. “I felt bad about that at the time, like I hadn’t deserved it,” she admits. “But honestly? You can’t change the system. Anyone would take the opportunity in your position.” Moreover, Olivia comments that whilst the opportunities she accessed undeniably augmented her career, good fortune is not everything; “What I’ve realised is: once your foot is in the door, you do have to be good to stay.”

Olivia finished her A-levels in 2018, leaving Cranbrook for Queens’ College, Cambridge. Now an editor and journalist for the Daily Mail, her career proves that success is not merely down to luck. She reflects “I got rejected from about eight jobs, and for some of these I’d done three rounds of interviews. It reminded me that a lot of my current jobs were down to luck.”

Discussing barriers to the industry, Olivia acknowledges her position in a maledominated field. However, she reflects “Women’s journalism is respected because it’s a massive money-spinner. Even if they don’t understand it, even if they think it’s petty and pointless, it is still respected.” It is a strange parallel, she adds; even if her work is looked down on, it is noticed nonetheless. “Our voices, quite contradictorily, are heard.”

From fashion houses to national newsrooms, Olivia’s experiences have reinforced her convictions that a sense of belonging is created by not where you come from, but rather how you show up. “Don’t fall victim to impostor syndrome. Hold on to the opportunities that have been given to you,” she urges students. Speaking on her experiences of both education and the workplace, she believes this applies especially to girls “I think a lot of girls don’t recognise the fact that they are good enough to be where they are. Boys always think they’re good enough, sometimes too good.”

Reflecting on her experiences at Cranbrook and afterward, her path reinforces a simple truth: you have to believe you deserve your place, even without being told directly.

Rowan Smith

From gaming rigs to giant data centres, computers waste huge amounts of energy as heat. Here’s how we could capture it to warm homes, cut costs, and lower emissions.

Computers waste energy in many ways, from small electrical losses inside components to the heat that escapes from cooling fans. While most of these losses are either too small or complex to capture, heat is different. It’s widespread, predictable, and in many cases, reusable. From your phone warming up while charging to vast data centers powering the internet, computing produces a constant stream of excess heat Right now, most of it simply drifts away unused... but what if we could put it to work?

When an electrical current flows through a computer’s components, such as the processor, graphics card and power supply, some energy is lost as heat High performance systems can get hot enough to need powerful liquid cooling systems just to keep running. In data centres, which house hundreds of computers running around the clock, cooling can use up to 40% of the total energy consumption. This creates a cycle of inefficiency: energy is used to power the computers and then even more energy is used to keep them cool. What a waste.

Some places have found creative ways to capture and reuse all the heat that is generated. For example: in Stockholm, Sweden, a data centre channels heat directly into its city heating network, helping warm thousands of homes. In the UK, Deep Green uses server heat to warm swimming pools and in France Qarnot Computing builds ‘computer radiators’ that heat homes while performing cloud computing tasks. Some individuals have even used ducting methods to redirect warm air from their PC’s exhaust into their rooms – a small but semipractical way to use energy more efficiently.

These emerging technologies could make heat reuse much more effective:

· Thermoelectric Generators: convert heat into a current utilising the Seebeck effect. These are becoming more efficient as new materials are developed.

· Phase-Change Materials: capture then store heat for later use, like thermal batteries.

· Liquid Immersion Cooling: involves submerging computers in a special fluid that effectively captures heat for later use.

One challenge is that computer heat, though sometimes exceeding 100 °C in core components, is generally considered low-grade energy. This means it is not hot enough, in a practical sense, to efficiently generate electricity or drive large-scale industrial processes.

Some people also argue that we should focus on making computers more efficient so they produce less heat in the first place, but growing demand for computing power means there will always be waste heat to manage. Many people also argue that instead of reusing computer’s heat, efforts should focus on producing fully renewable energy. While this is important for reducing emissions, it doesn’t address the fact that computers, and other electronics, still generate large amounts of wasted energy that could be captured. Reusing this energy would complement renewable energy rather than replace it.

Heat reuse won’t solve all our energy problems, not by a long shot, but it could be part of a smarter, cleaner system. As our world becomes more reliant on powerful computing and artificial intelligence, finding ways to capture and reuse this heat could cut energy bills, lower emissions and make better use of the electricity we already produce In the future, your living room could be warmed by a computer working hard miles away.

Lucy Wells

Gender Quotas – Gender quotas in politics are mechanisms, either legislated or voluntary, that aim to increase representation in political bodies like parliaments or parties.

Tokenism – The fact of doing something only to show that you are following rules, doing what is expected or seen to be fair, rather than because you genuinely believe it is the right thing to do.

Since the dawn of modern politics, it has been abundantly and depressingly clear that men dominate the political sphere. However, in recent times, there have been attempts to shift this patriarchal model to allow for more gender representation and equality in society This change begins with our leaders One way in which parliaments have tried to increase the number of women in political positions is by using gender quotas, which mandate that a party has a minimum number of female candidates or elected officials. It can be argued though that this is merely done to lift the reputation of a party as ‘diverse’ and is in fact performative, with men still monopolising politics and women continuing to face disadvantages in today’s political ecosystem.

Gender quotas take many forms and vary in effectiveness. The first example is legal candidate quotas, such as those in Bolivia. Here parties are legally obliged to have the same number of male and female candidates. This creates firm structural barriers to encourage female political participation and proved effective with women constituting 59% of parliamentarians in Bolivia. Other types include reserved seats, such as in Rwanda, which by 2023 had the highest percentage of female parliamentarians globally at 61%. Voluntary party quotas, such as those in Germany and France, depend on internal party rules rather than legislation.

In terms of visibility, quotas appear effective. Increased female representation is essential because it draws greater attention to women’s issues including gender-based violence Furthermore, quotas may drive real change as they help break down male-dominated and backward-thinking structural barriers. They overcome biased party selection processes, financial constraints, and cultural norms deeply rooted in many regions. In the UK, it was not until 1919 that a woman was elected as an MP, and even today, there are significantly more male MPs than female around 59.5% men to 40% women. Quotas are clearly effective in increasing representation and counteracting obstacles such as biased candidate selection.

But evidence suggests that quotas can also serve as instruments of tokenism. This means women are placed in political positions only to portray a party’s ‘progressive’ reputation. In reality, women elected through quotas are often unable to hold true power or act independently Their presence can be purely performative and serves the interests of the party rather than genuine gender equality. One aspect of this is that the power women hold tends to be symbolic rather than substantive, with party loyalty limiting their autonomy

Women placed in politics through quotas can sometimes be mere placeholders, with parties manipulating quotas to act as ceilings rather than pedestals In France from 2007 to 2012, women were placed in ‘circonscriptions perdues’, or districts where they had no chance of winning. The use of quotas can be counterproductive, with women used as tools to bolster a party’s image.

In conclusion, it is evident that quotas can be counter-productive and exemplify populist ‘tokenism’, or performative change. This makes sense: men who hold power want to keep it. They may present a façade of wanting more women in politics, but often position them in unwinnable seats under the guise of quotas. While there are definitely positive aspects to gender quotas, they can also accentuate gender differences and undermine meritocracy. As Martin Luther King Jr. said, “We should all be judged by the content of our character,”; equality should be inherent in politics, not forced or undermined by quotas.

Aurelia King

Mary Tudor’s legacy is stained by blood, as the only Tudor monarch to receive a cruel and accusatory nickname. Her brother, sister and father receive no such foul treatment but are fully known not to be God’s angels, so one must ask, why? Why is it that Mary is the main source of such vitriol? It is because she was a woman.

It is undeniable that “Bloody Mary” has been villainised through history for the burning of nearly 300 Protestants in 1555, a brutal and horrifying act that claimed the lives of men, women, children, and even clergy. It was, of course, a horrifying act. Yet, it is important to remember that such shocking cruelty was not unique to her reign. Henry VIII, for instance, ordered the execution of two of his wives for alleged crimes that men of his time committed freely, without consequence. Edward VI’s government sanctioned the deaths of nearly 200 Catholics for their faith, and Elizabeth I oversaw the killing of innocent peasants who dared to protest peacefully for their beliefs. All four Tudor monarchs, regardless of the length or success of their rule, inflicted pain, suffering and death Yet, Mary is the only monarch that we as a modern society still remember as the embodiment of evil and tyranny This enduring vilification reveals more about societal prejudice than her deeds: a reflection of how history punishes empowered women while excusing the brutality of men.

To understand the ‘why’, we must look at the context of the old world and the psychology of the new. During the reign of Mary Tudor, England was in a state of religious uproar. King Henry, a Catholic, preceded Edward, a hardline Protestant, before the crown passed to Mary, a hardline Catholic. The people of England were sharply divided, and due to invention and increasing popularity of the printing press, Lutheran ideas spread globally. The two sides of England could voice their beliefs and dissatisfaction with a newly astonishing ease, then influencing how monarchs were seen by the public.

This is where John Foxe’s ‘Acts and Monuments’ or ‘Book of Martyrs’ comes into play; one of the most crucial sources from this period Foxe’s writing was a work of Protestant propaganda that painted the burnings as tragic suffering at the hands of true evil, Mary Tudor. Due to the religious upheaval of the time, many shaped their entire view of the Queen from this book. Historian John Guy reminds us that “we must be aware of the bias of John Foxe”, that the Protestants “who prefer us to believe that Mary did nothing but persecute” were the ones to write the history of her reign. Indeed, could it not be because she was the first women in a position of this great a power to take such a strong stance for her beliefs that she was attacked so heavily?

However the argument then comes to Elizabeth Tudor, for she too was a woman on the throne of England, even in the same period as her halfsister. So, why is she put on a pedestal as the golden Queen while Mary’s reputation rusts? This is where we turn to modern day psychology. As a society, we are programmed to dislike change, sudden change that completely throws our understanding off-balance In a time of little scientific understanding and rigid social values, having a women in any kind of power made no sense, as women were seen as weakminded, and easily-corrupted To have someone so fragile on the throne of England, a superpower of the world, made people feel unsafe.

There are many sources from the period exposing how greatly people feared for England’s stability and that they thought it was foolish to have a women in such power. However, these occurrences also show that men of the time did not like a role they had deemed theirs for centuries to be “taken” by a women. Queen Elizabeth, even as the monarch ruling through the golden age, called herself a prince and said that although she had the weak and feeble body of a women, she had the strength and heart of a king. This serves as a clear reminder that women would never be seen as strong or rightfully in power unless they were to act as a man.

Even though our modern society is much m accepting of such change, we still see wom being put down, ignored and blamed by m who feel threatened by female power I ha described Mary as “a microcosm of women power” because she represents what wom across the centuries have experienced, a continue to experience on their journey empowerment. Mary was the first born Henry VIII but her 9 year old brother got throne first. Mary wished to marry but father and younger brother stopped her to ke her under their control. When Mary fin married she was said to be foolish as husband would just use her. People assum that she would not or could not stand up herself and therefore she must have be foolish for putting herself and England in su danger, and even when Mary wanted to do socially acceptable thing and have children, s was told that she was too old, told that she w wrong for putting producing heirs in front ruling a global superpower. Even when s protected her faith as a devout Catholic, s was slandered and disgraced. Unfortunate due to misogynistic bias in history, women ha forever been valued less than men and th stories buried so they would soon be forgott or never taught at all.

Would you find it shocking to know that without Mary Tudor setting up trade negotiations with the Baltic regions, Elizabeth would never have recovered from the poor harvests in the 1590s? Or that without Mary working with her parliament to pass the Act of Regal Power (which stated that queens held power as fully, wholly, and absolutely as their male predecessors) Elizabeth would not have been as respected as she was by her parliament and people? Perhaps Mary’s actions in 1554 when she was faced with a protestant rebellion and she gave a “remarkable speech at the Guildhall” attacking Wyatt as a “wicked traitor”? She “defended her religion and choice of husband and called Londoners to stand firm in support” in the words of historian Whitehall. A speech so well received that the people of London refused Wyatt entry at Ludgate, effectively ending the rebellion without as much bloodshed. Of course not, because when people saw Mary Tudor, a woman in a man's place, they knew that if they could make her look like the devil, that is all anyone would ever see.

p g g j

the CEO of a company, to a woman who decides she does not want to get married or have kids, or a woman who does not follow what men think is their right to demand, certain men use anything they can to drag her down For Mary it was making her look like an evil ruler, for Matilda it was blaming her for war, even for Elizabeth, it was saying she was only strong because she was more masculine than feminine, and for the women of the modern day, the list is endless.

Mary Tudor was the first for many things and that scared people. It scared both men and women who expected certain traits and roles of the sexes, so when Mary took the throne and started making changes, people panicked. No matter how much good she did for England, ‘Bloody Mary’ would never escape the tarnish that such hatred incited, and for many women today it is the same, no matter how hard they try to do good, to do what they believe is best for them, others will stop at nothing to make sure their reputation falls in ruins.

Toni Brodelle is the current parliamentary spokesperson for Wycombe and a member of a House of Lords task group on human rights in the Middle East, having devoted her career to standing against injustice in all forms. We met with her to discuss her journey, from a student to a teacher, activist, and political figure, and to ask what advice she would give to young people hoping to create meaningful change.

She explained that her motivation has always stemmed from a deep-rooted intolerance of injustice “I’ve never been able to tolerate injustice,” she says plainly Even as a student, she was compelled to act. “I set up Amnesty International at our school because I was so incensed by some of the things I was seeing.”

Her work soon expanded into international activism, particularly in relation to Syria and Palestine She became involved in selecting speakers for a TED event and met the president of the Pay It Forward Foundation. Their conversation would be pivotal. “He said, ‘We’d really like for you to come and help us in terms of developing our reach.’” Toni went on to help expand the organisation’s reach from 2 global chapters to 75

However it was her encounters with asylum seekers stranded across Europe that sharpened her focus Soon her interest in why people had been forced to flee grew: “The more I found out, the less I could keep quiet about it,” she says. “If there’s something wrong, you don’t get to sit there and say, ‘Someone should do something about that,’ unless you’re going to be the person.”

As her expertise in the Syrian conflict deepened, she began working more closely with legal teams, the media, and eventually Parliament. “You very quickly become noticed if you’re the kind of person who will speak out and roll up your sleeves,” she observes. Her current work involves advocating for victims of war crimes, and she is involved in a potentially landmark case that could result in the first prosecution of its kind in the UK “War crimes work takes time, sometimes decades,” she says. “But you have to be tenacious in believing that it’s for the best.”

Despite her growing involvement and influence in political spaces, Toni initially resisted the idea of standing for election “Party politics is tribal It’s really dirty. I didn’t want to be involved in any of that.” But a conversation with Lord Roberts of Llandudno changed her view. “He said to me, ‘If good people don’t get involved, then you abandon it to those people.’ That stuck with me.”

As a teacher, a mother, and an advocate for justice, Toni felt she couldn’t stand by. “If you really believe that your voice matters, then you need to get up and be a part of making things better.”

We asked what advice she would give to her teenage-self, and her answer was clear-cut: “Never allow anybody to tell you that you can’t… starting with yourself. You don’t have to wait to be a certain age to make a change.” Toni is also a firm believer in the power of kindness, not as sentimentality, but as a strategic force. “There are very few problems in the world that couldn’t be resolved by kindness to ourselves, to others, and to the environment”. She believes this is an trait that underpins good leadership, referencing Lord Roberts of Llandudno as demonstrating this: “in all the time I've worked with him, which is 10 years now, I've never heard him do or say anything unjust or unkind He's always been profoundly fair, and I think we need more of that ”

Yet her work, especially in politics, has not been without obstacles. “I have been discriminated against, particularly in politics, on the grounds of being female… all the time. Being a mother. Being a single mother.” She warns against internalising such discrimination: “Never, ever allow anybody’s perception of you to become your reality You don’t need anybody’s permission to take up space.”

She notes that the political sphere remains heavily dominated by a narrow demographic. It’s still a space for the “pale, male, and stale… and that has to change ” However, she is encouraged by the increase in female representation and supports groups such as 50:50 Parliament, as well as mentoring women entering the field. Still, she warns that the fight for equality is far from over: “Misogyny is real… This is something… you don’t ever become complacent about.”

Her outlook is shaped not only by political experience but by motherhood. A few days after giving birth to her first child, she remembers “lying in hospital with her in my arms… I had never felt such a profound sense of peace You know And I, and I just remember thinking there is nothing that I wouldn't do to protect this moment” That experience transformed how she saw the world. “There were other mothers in extremely challenging circumstances, whether it was through poverty, whether it's through natural disasters, whether it's through oppression, whatever it was that didn't have that moment of peace.”

Wrapping up our conversation, one message remains clear throughout: action matters. Toni's journey is a reminder that speaking up, especially when others stay silent, can truly lead to meaningful change

The New Cranbrookian would not exist without the support of so many wonderful people. We would like to thank Mrs Corney, Mr Clark, Mrs Williams, Mr Young Min and Mr Tomlinson for their help, and the CSPA for their generous donation. Additionally, we are immensely grateful to everyone who has made a contribution towards our costs, written an article, supplied us with photography and artwork, or allowed us to interview them. The magazine has taken many months to compile, and without the work of students, alumni, parents, teachers past and present and many more, we could not have succeeded in printing such a broad and engaging collection.

We look forward to passing the reins over to our team of Year 12 editors who are already working on the next edition of The New Cranbrookian.