THEGARDAN

We’re pleased to share this latest issue of The Gardan Journal — filled with your poetry, artwork, stories, images, joy, and pain. Issue 09 raises questions of fear and reward, it asks us to trust in time and process. It brings us back to nature, and holds us to account. As Lorene Garrett writes “I came to this Rocky Gardan not expecting to hear my fear echoed in shrill coyote hollers.”

For many of us, our artwork is a way to process uncertainty. We use the creative act to unearth the underlying feelings that drive our actions, our emotions, and our fears about what comes next and how to proceed. Mary Dingee Fillmore reminds us that:

Sometimes the horizon’s clear: a distant charcoal line, sometimes a mere idea in the shifting fog.

The simple act of sharing your stories in these pages is an act of fearlessness. A defiance of fear. Sue Herne calls this act of sharing “An Odd Nourishment,” saying “I bring you my sorrow…placed carefully on the table.”

We invite you to share your work with us anytime by submitting to The Gardan online at www.craigardan.org/gardan. Issues are published annually and directly reflect your voices.

Whatever this season brings for you, may you be fearless in your approach to art and life. — Michele Drozd 10.31.24

Craigardan is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization with a mission to encourage the human imagination to interpret the world with philosophical, ecological, and artistic perspective.

To ful fi ll our mission, Craigardan supports artists, chefs, craftspeople, farmers, scholars, and writers through residencies, social justice initiatives, our community farm, and other public programs.

Located in the heart of the Adirondacks, Craigardan’s artist-in-residence program strives to cultivate a rich and collaborative place-based experience for all people working in all disciplines. Our strong interdisciplinary foundation encourages creative thinking and collective problem solving by welcoming diversity in all of its forms.

Muriel Luderowski, President

Allison Eddy, Vice-President

Gayle Burnett, Treasurer

Loren Michael Mortimer, Secretary

CRAIGARDAN

www.craigardan.org info@craigardan.org 518.242.6535

The Gardan , a project of Craigardan, is an offering to our creative community near and far, delivering a small piece of our program — along with inspiration and ongoing support — to encourage you to self residency wherever you are.

The Gardan is intended to foster conversations about creativity and its processes among and across all disciplines. We welcome contributions from artists and thinkers, activists and farmers, environmentalists and chefs at any and all stages of creative development.

We hope that The Gardan will unite you with your extended family of creative thinkers and bring a breath of Adirondack air to your inbox.

Each issue can be found online at www.craigardan.org/gardan.

We invite your contributions of words, images, video, fi eld notes, sound, and any other way you wish to connect to us, and to each other.

Issues are curated by our editors. Complete guidelines for content submission are online at www.craigardan.org/ gardan

The Gardan is guided by our staff and fully supported by Craigardan’s funding and the efforts of our board and volunteers.

Erica Berry

Michele Parker Randall

Lanse Stover

Michele Drozd, Executive Director

With special thanks to editors Mary Barringer and Kate Moses.

9216 NYS Route 9N, Elizabethtown, NY 12932

AMY CHENEY-SEYMOUR

BETSY POWER

BONNIE SPARLING

CAPERTON TISSOT

CHRISTIE GARDINER

CHRISTOPHER LOCKE

DANIELLE LEVSKY

DENNIS DELAY

DUANE L HERRMANN

GEORGE OKUDAYE-STEPENS

JACKIE HALL

JAMES B. KOBAK JR

JOE BECKER

KEITH KOZLOFF

KIKI LIU

LAURA VON ROSK

LORENE GARRETT

MARGARET WISS

MARTHA VINING

MARY DINGEE FILLMORE

MICHELE ZELKOWITZ

SEAN O’SHELL

SOPHIA BRANDT

SUE ELLEN HERNE

SUMA NAGARAJ

TAMAR BORDWIN

TYLER BARTON

WILLIAM CAMPONOVA

COVER

FRONT: “Clover” by Joe Becker. Ellicott City, MD

BACK: “Untitled” by Joe Becker. Ellicott City, MD

By Margaret Wiss

York, NY

2020 | Film Stills | Weston, MA

2022 | Film Stills | Truro, MA

Coronavirus uprooted life. When the pandemic hit New York City where I was finishing my MFA in dance at NYU’s Tisch School for the Arts, I left. As a choreographer and dancer lacking formal space, people, touch, and a community, I was forced to reassess what dance meant to me. Upon returning to Massachusetts, I began to do daily dance studies in an open farm field, working with the landscape, my daily dance sequences, technology, and a composer, Mike Brun, remotely.

My work has become increasingly site-sympathetic in recent years. The landscape is my primary collaborator, emphasizing the absence of others but also the presence of space, time, and nature. In a world searching for direction, I am reminded that this is the place of now as I practice presence and hope to capture the essential moment. I believe COVID-19 revealed how important mundane movement and our environment are to our navigation and sanity.

I chose to document these site-generated improvisations by bisecting the frame of my body; only my torso remains. The images highlight the expansive sky and remind me to have hope. I am without legs, without roots perhaps but finding serenity in the simplest of organic matter. While in stillness, I am reminded that there is motion all around – the wind brushing my hair, the weeds rustling beneath my feet.

At the beginning of this project I believed I would end my study with the pandemic. After two years it seemed COVID maybe forever lingering, forever in the air. Therefore I have repeated the process of my work in the field in a new location — a location molded by the air and quickly visually adaptable. The Provincetown Dunes were the perfect place and I became an artist-in-residence for the Peaked Hill Dunes Trust in 2022. During my time in the dunes, I repeated the improvisational ritual. This experience enhanced my work by adding a new conversation, a new texture. My fieldwork in Massachusetts focused so much on looking up, and instead the dunes grounded me. They are constant bodies, but are impermanent, shifting with the breath of the environment. Similar to the state of the pandemic, over these years I have found an ease, a settling in this very unsettled world and landscape.

By Michele Parker Randall (’23, ’24) Sanford, FL

Nighttime holds no peril that cannot be shaken by porch light. I take off my shoes, my clothes, and sit; I watch the streetlights dim. Here begins evening; five. Light spills out of eyes that cannot see mine, the sea a staircase of salt when I step into it; four. Though blinds down, light-ponds strike paths from every window. Light of eyes not mine; three. Even laundry—elegant now in the machinery of it, in red-square shine and chrome—chimes Mahler instead of a reminder bell. I forget my mouth can be anything but that which opens, helpless with spindly moonlight; two. Drawing in breath—

why do they call it “drawing”?—how hard to name the thing I ache for as every day begins to gather up its threads. I want a photograph of the dark pink art of a lung. One; hand knotting, twisting, holding close. You wouldn't think the landscape even noticed light gone powder blue, but when I ask the question,

I ask it of everything: the plastic milk crate left aside, the cow pasture where gray herons wade and wander, the grudging symmetry of the strawberry rows.

Poem and sculpture by Betsy Power (’24) Portland, OR

She performs the expected tasks gentle curves appropriate demeanor the refined reflection

Just another a-not-her a pre-conceived notion rend-her-ed invalid before her first breath

Yet a whisper an inner an in-her she knows she cannot reach cannot name obscured still now even from herself

A twin born of a more just landscape a her a hidden in plain sight

My Dear Beloveds

Lorene V. Garrett

(’17, ’23) Rio Vista, California

With much gratitude and love for Kate Moses & the Bookgardan 5 Cohort: Ann Monroe-Mullen, Meg Lamme, Michelle St. Romain Wilson, and Tara Badstubner

My dear beloveds, I came to write in community with Bookgardan sisters, to call on letters to leap through galaxies, fly beyond years of fear to land memoir words on the flank of Hurricane Mountain.

My dear beloveds, I came to write paragraphs birthed by sentences, ignited by images so explosive they’d punch through the high-stepped threshold to reach Craigardan Cabin 4.

My dear beloveds, I came to write between the peeks of Owl Head and LimeKiln, Iron Mountain, Blueberry and Cobble Hills, their coarse skins glorious, knotted, bursts of lemon and burnt sienna.

My dear beloveds, I came to write beneath a night sky flinging luminosity so bright it unveiled the clarity of God, the breath of the Universe, and of course, Tom Hanks’ interpretation of an Oscar winning role.

My dear beloveds, I came to write within the questions: Is that Venus? Are you real? What do you need? Do otters hold hands? Is this Hallmark, ABC Afterschool Special? Can you tell me how long the words will take?

My dear beloveds, I came to write, wanting words to slip into my mind, like a wood mouse tiptoeing through the outdoor kitchen, like a lamb nose skirting fence top.

I came to write, not to whisper words away. Not to exhume blocks sowed by decades of workshop wisdom: No story. No tension. No conflict. Always scene, not summary. What has the author come to say?

I came to this Rocky Gardan not expecting to hear my fear echoed in shrill coyote hollers. The barrier between me and my expression, almost impenetrable. Each letter, each phrase requiring coaxing, like squash tossed into the Farmhouse pen to rouse housed chickens.

My Bookgardan sisters, I came to the mountains and with you, rain seeded creativity. With you, pumpkin bread culled self-discovery. With you, my words surrendered, and finally delivered.

By Christie Gardiner (’24) Pleasant Grove, UT

The night is hot when we drag a mattress to the back yard, to see the stars falling in August. Each streaking piece of iron-nickel metal, sulphide, and carbide minerals bring surprised screams of giggling delight. I am under your right arm; he is under your left. A sandwich of children your children.

You will leave them. You will not speak of them. You will let them fall from your arms like stars from the sky, their fire trails burning hot before they disappear.

By Christopher Locke Essex, NY

I said go long, the football unzipping the air between my daughter and me. She leapt, eyes closed. This is where I break her nose, I thought, but just like that she hauled it in, more surprised than me. Soft hands, I said. She smiled and chucked it back, the ball tumbling like a shot duck, which is an insult to ducks everywhere, shot or otherwise. But neither of us cared, and we managed a back and forth perfectly suited for the day: the sky rinsed blue, the garden freshly turned with new rows of basil and rosemary, and the wind content to lift our shouts and our cries into space more rarified than gratitude itself.

Kiki Liu (’24)

Los Angeles, CA

“Mesmerized by the changing light and the shadows, the juxtaposition of the hard and soft, the merging of smoothness and fizziness, where the temporal and eternal crosses paths, creativity finds its harmony.”

Entranced by the enchanting allure of shifting transparency and translucence, reminiscent of delicately woven spider webs and the ethereal grandeur of high-fired porcelain, I collected a selection of slip recipes, each possessing its own unique properties. The porcelain chips are delicately nestled upon the woven base, and I assemble these fragments into petite stacks or arrange them side by side.

Maple Parfait

Martha Vining Asheville, NC

Maple syrup has been produced in the North Country for hundreds of years. The recipe below for Maple Parfait/Mousse is from, ‘The Little Gem’, published in 1916. Compiled by the Ladies of the Baptist Church, Keeseville, NY and published by the Adirondack Record in Ausable Forks, NY.

Community cookbooks first appeared in the United States during the Civil War as a way of raising funds to offset medical costs for soldiers injured in the war. Eventually, local churches and thousands of charities published community cookbooks to raise money for all sorts of projects.

Maple Parfait or Mousse

Beat yolks of 4 eggs; add slowly 1 cup hot maple syrup; cook in double boiler until coating is formed on spoon; cool and add 1 pint thick beaten cream. Pack in mold for 3 hours, in ice and salt. -Clara M. Baber

Hiroshima (sic)

Sean O’Shell

Tupper Lake, NY

. . .

The clouds determined which cities would be bombed and the bombers rubbed blood on every hand that ever waved water vapor.

There are actually hundreds of types of love and some are fairly treatable. There are exciting discoveries on the horizon. It could be a thing of the past.

but what would we die of?

your hand stirs blood your voice is silent to the cycle the bombers will chart the cities you free of vapors

they are curing one love at a time

so many loves erased if anything could curl the tracks of a black hole, wouldn't that be it? and how long would it take?

is one coming to cure this world right now?

some cities wait for presidents to apologize, and don't mind the hum some sities call their kids bombers and sell miracles for ice

the telescopes squint who listens?

the kids are running all the cities they're having too much fun this lesson was skipped for the aptitude battery.

My Grandmother Died of Hypothermia

Amy Cheney-Seymour

Saranac Lake, NY

I don’t want to unzip my soul and loose the stiff buttons of deep pocket tragedy to the sound of dry fingers snapping.

I do not want to parade her life, ending first blackened and split feet cradled on chlorine sheets in the beeping ICU. Can we start in the middle, shall I tell you of her pet squirrel gray tail twittering, snapping peanut shells?

She was a farmer’s daughter and a plumber’s wife who rode her pet cow for miles.

A mother of nine who raised five, the most of them lived but I slipped some Laura Belle, Laura the beautiful, Memée, crocheted thousands of afghans, sold rolls at the Marcy Club, preferred butter pecan ice cream, spoke French first and English last. Isn’t that better than final agitated hours or do you want to know what happened that January night, how she pushed the heavy door open, and slipped, in search of blue shivering stars.

James B. Kobak Jr.

New York, NY

A pox on Persephone, her price too dear

The fresh-frocked Spring debuts again today. Like clockwork now the shuttling goddess nears

From the drear dark realm where she was locked away

A shock to see the goddess reappear

Though her mother’s noxious curse won’t let her stay

The restocked mud-brown earth makes all too clear

The toxic debt for life that all must pay

For Spring but frolics in our hemisphere

On icy phlox she wends her wanton ways-Blithe, taunting doxy escaping death each year

While our blocked, broken path leads just one way. Goddess of paradox, half hope, half fear: Your wheat-gold locks, your garlands, your bouquets, Your mocking scents: none of that long lingers here

Every seed you strew stocked with its own decay

By Michelle Zelkowitz

Elizabethtown, NY

After stopping my bicycle on the side of the road, I pulled the back of my t-shirt up to my neck. “Lenny, look at it,” I said. “It feels all crusty. What is it?”

With the tip of his forefinger, Lenny gently touched my back. “Stop! Just look at it. What does it look like?”

“It looks like a bad sunburn. How does it feel?”

“Well, it’s driving me crazy, I replied while digging my nails into my back. “Are you sure it’s just a sunburn?”

“I think you better see a doctor. There are blisters.” “Blisters? Why didn't you say that to begin with?”

Three weeks into the bicycle trip, I had to see a doctor. I hated doctors, especially dentists. When I was about eight years old, my mom dragged me to the dentist to get my front teeth repaired after I had fallen on the concrete while skipping rope. I can still hear the dentist's drill. It sounded like the high-pitched cry of a band of wolves calling each other during the night. What would some hick doctor do to me?

We were in some godforsaken town in Wyoming and this doctor told me I had a second-degree burn and needed to stay out of the sun. What did he expect me to do? Lenny suggested we take a train, a freight train. “Really,” I thought to myself and then out loud. “A freight train! Why can’t we find a regular one?”

“We don’t have much money.” And that was that. To avoid the sun, we rode our bikes late in the day and arrived at the freight yard at twilight. Lenny checked with the stationmaster. “When would the next train be heading north?”

“Just before sunrise.”

It was going to be a long wait until 5 am. So we selected a spot on the gravel near the tracks to put out our Ensolite pads and sat. With nothing

much to do in the dark, I started scratching my back. “You shouldn’t do that,” Lenny scolded.

“What are we supposed to do all night?”

“Sleep,” Lenny said while searching for something in his saddlebags.

“My back is burning up. How can I sleep?”

Lenny began lathering cortisone cream on my back.

“Stop! It's just making me itch even more.”

“Just hold still. Give it a few minutes.”

Impatiently, I pulled my sleeping bag out of its stuff sack and laid on my stomach somewhat uncomfortable, but fell fast asleep.

Before dawn, we were awakened by the whistle of a train. I hopped up and stuffed my sleeping bag back into its sack while Lenny did the same. Then we raced to catch the train and almost went on the wrong one. Luckily, the stationmaster spotted us from his stance by the engine and yelled, “That’s not your train.” We were about seven cars back when he started signaling to us that our train would be the next one to arrive.

By Jaclyn Hall Akwesasne, NY

It stopped only briefly before the conductor yelled, “Go to the rear.” While we were walking our bikes and gear past empty flatbeds and cattle cars, the train moved slowly back and forth, unloading some of its cars. Suddenly, it halted and the stationmaster motioned for us to climb aboard. Lenny threw our saddlebags in and lifted our bikes one by one into the cattle car. Then he helped me. The first step was too high for me to reach so Lenny lifted my leg in clasped hands. But before I could grab the bar to pull myself the rest of the way I fell back. So Lenny jumped into the car and stretched his arm out. Just as I clutched it, the train jerked forward. My feet dangled in the chilly air before my knees hit the hard wooden floor. Even though the door was open it smelled of urine and manure. Yet that was not the worst part. It was the lack of light and not being able to

see our surroundings. I felt isolated as I shuffled away from the open door. Before I realized it, the train started moving, and the morning light shined into the car. Then, of course, we could see the interior, the filthy floorboards and walls. This was a place where animals were placed for transport and I felt like I didn’t belong.

For a while, Lenny stood by the open door.

“Please be careful,” I said, concerned he might get thrown out if the train suddenly jerked as it had been doing off and on. But mostly, it just rolled along, clacking and clanging as trains do. It was a bit boring being on a train for several hours, but not as much as I expected it to be. At times I gazed out the door and imagined being on my bike, whisking past grasses, wildflowers, and distant snowcapped mountains and thinking how beautiful it was in Wyoming.

“I think we are coming to the Thermopolis Canyon,” Lenny said as he extended his head out the door. And before I had a chance to stand next to him and get a better look, we were in pitch blackness. Lenny swayed to the floor and I scooted up to him.

“How long is this tunnel, you think?” I asked. “Don’t know.”

“What’s that smell? It’s awful. I feel like I’m breathing in gasoline.”

“It’s diesel.”

“That’s worse.”

The fumes of engine smoke started filling the car and our lungs. We both coughed. Oh, how I wished I was in a passenger car like the one I traveled on my American Youth Hostel bicycle trip. Now that was fun like a Disneyland ride. The dome car was 2 stories high and you could look out the windows at the expansive landscape or up into the blue sky and watch the clouds pass by. In this train car, I couldn’t see anything, not even my own hand. I couldn’t wait to get out!

“Where’s your hand? Let me hold it,” I said. “Here, do you feel better?”

I clasped his hand, squeezed it, and said, “So I thought we would have a good view of the canyon.”

“Guess we are going through it, not next to it.”

“You bet we are. I don’t know why I believe what you tell me.”

Lenny wrapped his arm around me and snuggled. He was about to kiss me when the train moved into the light.

“We should be coming to our stop soon,” he noted, looking out the door.

An hour passed and we were still stuck in the cattle car. As usual, Lenny just told me what I wanted to hear. He figured we had another 70 miles to go but neglected to tell me.

For a while, I stood, balancing myself against the cold metal door, rocking sideways, peering outside. For five hours we watched the sagebrush twirling and bouncing in the wind and a few groups of antelope running beside the train as it advanced between 25-30 miles per hour, twice the speed at which we biked. Occasionally, we heard a whistle, and the train stopped to release or add a car or two. Otherwise, the ride was uneventful.

“At last,” I said, noticing some old wood-framed buildings near the tracks.

“We made it,” Lenny said.

“You can’t be sure. Can you now?” Then we heard the whistle blow: 2 long blasts, 1 short, and another long blast. We were approaching a station. “Maybe you are right for once,” I said. “Thank goodness and good riddance to this place. I feel sorry for the cows.”

We both laughed with relief as the train slowly came to a stop. It jerked for the last time. I couldn’t wait to jump off.

In the yard toward the train's rear, I saw three men. I didn’t see bags attached to sticks over their shoulders, the stereotype of Hobos. Were they, like us, just catching a ride? Either way, I wouldn’t have wanted to be in a pitch-black tunnel with three strange men.

Lenny and I survived the freight train ride without injury, except for maybe some lung damage, but what did we know at 20-something? We were as they say young and stupid, especially I with a sunburned back. I will never forget this harrowing hair-brained idea of Lenny’s.

by Sue Herne (’24) Hogansburg, NY

I bring you my sorrow,

placed carefully on the table.

A mismatched, yet striking, part of the table setting; everyone has brought their own.

Set to the right of each plate, by the glass, they sit mute yet felt in the air.

We wave our hands by our faces as if we could brush our sorrows away and let our pleasantries carry them off on a cool breeze, but they fall onto our plates.

We eat them. An odd nourishment takes place as we all accidentally take a bite or two of someone else’s grief, amidst the jokes and banter.

Suma Nagaraj (’24) Bangalore, India

Sunday. Bring home groceries day. The vestiges of last night’s alcoholic excess gnaws on your nerves, the beginnings of a hangover that can only be quelled by coffee and toast with butter. ‘Buy one, get one free!’, screams the alert from the supermarket in a text message, a service you don’t remember subscribing to. Wily marketing that actually means old eggs need to make way for new ones on the shelves so business can continue apace. The smell from the living room is one of ennui commingling with the sweetish stench of stale onion rings and empty beer bottles. Oh, the blasted chicanery of pretense youth. You walk around, shoving all evidence of another wasted Saturday night into a trash bag.

The afternoon will require application of thought to the many things that lie ahead: the coming week, stoicism in the face of gaslighting that’s all too common now at the workplace, bills to pay, all those things that make up a life that somehow arrives despite all those roads of yesterday paved with good intentions and forgotten dreams, but who cares about all that? It’s still morning time.

You fold the newspaper neatly, clear breadcrumbs off the table, check your visage in the hallway mirror, notice no errant cowlicks that need to be gelled and smoothed into place, no poppy seeds sticking to your teeth, nothing that needs you to stop in your tracks to reassess. But you still do. Because mirror, mirror on the wall.

Not bad. Not bad at all.

Your unerring muscle memory makes you reach for the keys hanging from one of the

hooks under your wall sconce, two and a half steps from the door, so that you don’t have to crane your neck or twist your torso any more than you should to reach for them. Age can be a pain in the ass, but it teaches you things.

Off you go. *

As you stand debating whether to buy the fat-free or Vitamin-D enriched milk in the dairy section, you see her. That is to say, the corner of your eyes, long used to always being on the lookout for the sight of her, spy her unmistakable gait, legs sheathed in spandex, cardigan wrapped around her waist, feet in soft-heeled flip-flops that make no noise, disappearing into the personal hygiene aisle. Your eyes, ever furtive, ever hopeful, manage to get the tiniest glimpse of her from the back, and the line of capillaries that connects your eyes, heart, and loins clicks distinctly into place.

How long has it been? Two years? Five? Ten? 14 years, seven months, week three, day four into the eighth month, to be precise. But who’s counting?

Is it possible she is finally in your city like your friend told you she was? Has she changed much? Branching from that question, how much is too much? Or, for that matter, too little? What do you expect to see? That frisson of anticipation laced with fear slowly advances from the base of your spine to the nape of your neck. What will you tell her if you do come face-to-face with her? If nothing else strikes you when your eyes meet, you tell yourself, you will resort to the time-tested and failsafe ‘Hello.’

She is nowhere to be seen. Your eyes dart back and forth and everywhere in between, frantically, but alas, no sight of her. Was it your imagination? Is it possible that you might be hallucinating? You’re now torn between the absolute terror of seeing her again and the distinct possibility of you-may-never.

But no, your eyes weren’t deceiving you! There she is!

Thank god. She turns ever so slightly, and you see the large pink birthmark on the right side of her neck. You’re struck by how intimately you know its crests and troughs, its sharp edges on the top and the delicate concavity at the bottom, as if it is always in attempt of receding into itself. You’ve traced that pattern on possibly every surface imaginable: the walls of your house, the sand at the beach, breakfast oatmeal, on the pillowcase, all those women’s backs that have been in your bed since, and sometimes, in the puddle that drips down off you onto the floor as you emerge from the shower cubicle, in that space between the rug and the sink.

You lose her again. *

By now, the desperation to seek her out and say those unspoken words trumps the fear of not being able to ever say them. You briefly consider just hanging out near the cash counters –she’s sure to show up in one of the queues, sooner than later. As you round the bend, you see her walk into the frozen foods section.

Lemon sorbet. Of course. You remember how you’d learned to develop a taste for it even though your tongue rejected the sharpness every time she invited you to dig in. The bitter aftertaste as the citrus registered on your taste-buds had nothing on the full-throated mmm that escaped her lips those long-ago nights.

What will you say? Hasn’t it all been leading up to this very moment, here, now?

You slowly advance towards her as her hands deftly reach into the shelf to pick out two tubs of lemon sorbet. You think you might now know what a man dying of thirst in the desert feels like upon sighting a mirage. You’re not even a tad remorseful about your mind resorting to lazy clichés.

You send up a silent, fervent prayer to the speech Gods up above to help line up those words in your head into one coherent sentence as you bridge the distance.

You’re now close enough that your breaths will sync in a minute. She looks up. As recognition dawns in her eyes, your phone jangles somewhere deep in your back pocket. Unbeknownst to you, your left hand, long accustomed to reaching for it even when you don’t want it to, pulls the phone out, and your eyes, long accustomed to being servile to the white-collar diktats of your life, glances at the screen.

It’s your wife calling.

Lament

Tamar Bordwin

Hastings-on-Hudson, NY

Lying here in this golden-blue light with ants making their way up my legs and that warm, wet-green smell pressing me down into the earth, I find I am awake.

You say I owe you nothing, but you have already named a thousand birds for me and you clutch your ribs when I sing too loudly.

I wish I could have been made of myself.

These trees have been growing for five hundred years, and I think they might fall over soon. I think I sense the roots weaning themselves off the soil.

Sometimes at night, while we sleep or fight or make love, something winds its way past our hut;

sometimes the trail it leaves is still there in the morning; sometimes it is not, but always I feel its waxy presence as it passes.

When the sun drops beneath the endless stretch of shimmering sand and cool ropes of air run along the ground and up my skirts, I let myself glance back, just for a second. Most days, great, meaty pillars of wind rise to block my view and fill my tired eyes with sand, but on some days, if I turn quickly enough, I can just make out the garden in the distance, that evil blue wisp of moisture rising on the horizon, creating bubbling rivers of creation from itself, casting me out a thousand times over.

Impostor, Unveiled

Danielle Levsky Philadelphia, PA.

I hesitate to accept the invitation that lands in my inbox— to bare the knots in my psyche,

unfurl the tangles of my identity, ponder my authenticity, and create something from my brain, something true

An invitation for me, because of who I am. They want me uncoiled, exposed in all my shortcomings.

How would it feel to be unmasked like the Phantom?

Layers of me peeling, a sprouting potato.

Go on, Sappho. This is just, it is true. Must I defend my right to stand exposed in this skin claimed by discordant identities?

My feet carry the residue of repression. How many times have I grasped at my self, only to watch my reflection fragment between worlds seen and unseen?

I witness my stories under blue light, humming in a Minor Key. Again, I learn to understand the luxury of accepting oneself. Again, I bite the pillow when the audience looks at me.

Forget the labels.

Someone offered pronoun buttons at rehearsal. I wanted to grasp them in my palm until it bled, but I stayed quiet, drawing my stage directions from an Old Country well of self-doubt.

What I want most is to stop wanting—

Yearning for a partner that does not exist, yearning for a family that simply understands, yearning for a kiss that lives only in fiction,

Yearning for a homeland without war, without the need for resilience.

Yearing to release the phantom pain of missing people and places, swallowed by history's hunger.

Here, at the footlights, the fear that blinds me. What my self would do if it unraveled to bare all, to declare that I owe no explanation to anyone, not even to myself.

Duane L Herrmann

Topeka, KS

I had no choice, again – no choice, I had to work the fields money was needed and that's all I could do.

My back ached, there was no end. Someday, someday I want a different, better, easier LIFE!

One where I can relax and tell the boss to leave.

A fantasy, I know, but maybe someday…

By Jackie Hall Akwesasne, NY

Generations of practicing patriarchs continue to add to the disempowerment of women. Whether it be with malicious intent or not, this practice began somewhere around the time Western society shifted from nomadic hunter-gatherer societies to settled agricultural communities which then led to the establishment of patriarchal systems within these societies.

The same cannot be said for Onkwehonwe people (Original People of this land), specifically the Rotinoshionni who have always had both a society of hunter-gathers and an “agricultural” society; these were the roles and responsibilities of both men and women. It was not until the first colonizer stepped foot on the shores of turtle island with orders to indoctrinate our minds and dispossess us of our lands, that the systemic disempowerment of our women began.

Unfortunately, we as the Kanienkehaka have not been able to escape patriarchy’s reach, nor could many other Onkwehonwe who were forcibly assimilated. Once Church and State got their hands on our children, they proceeded to “kill the Indian and save the man.” Patriarchy has become so prevalent in what was once a matrilineal society, that it is now very difficult to practice the Kaianerekowa without major resistance from those who are perceived to be in positions of power.

In our ancient practice, known as the Kaianerekowa, the need to fight for gender equality did not exist because the women held power just the same as the men. We all carried out our distinct roles and responsibilities according to our clans, and according to gender.

The way we organized ourselves as a people was intrinsically structured in a way that we were able to achieve a series of shared goals for the benefit of the collective; whether it was at a clan level,

nation level, or confederacy level. Our system of governance was so sophisticated that citizens from other nations attempted to duplicate the Kaianerekowa in an effort to create a de facto constitution enforceable in the “New World” in an effort to break away from the citizenship they left behind.

Our governance structure and forest diplomacy were remarkable enough for the newcomers to draw inspiration from, but they could not allow the savage Indians to have intellect and diplomacy without first adopting their Christian god, who was believed to be superior to any other gods or goddess.

The Kaianerekowa is a living body of principles derived from the natural world. To be maintained, it must be practiced and adhered to according to our cycle of ceremonies, which requires us to uphold our roles and responsibilities as men and women. This includes the understanding that every living being is of equal value, that we are not superior to one another and there certainly is not one entity who carries supreme power over the collective.

We all carry our own power/sparks. When brought together as a clan, nation, or confederacy, we become one of the most powerful forces reckon with. But to become that powerful force, we must all bring our sparks back together and allow our council fires to burn once again. That may mean working to uplift our people’s spirits so that they may gather themselves and reignite that which was meant to burn inside them.

For far too long, oppressive forces have made sure to keep us scattered and divided so that we are unable to reignite our ancient council fires and reclaim our power. When we begin to rebuild ourselves and our families adhering to the

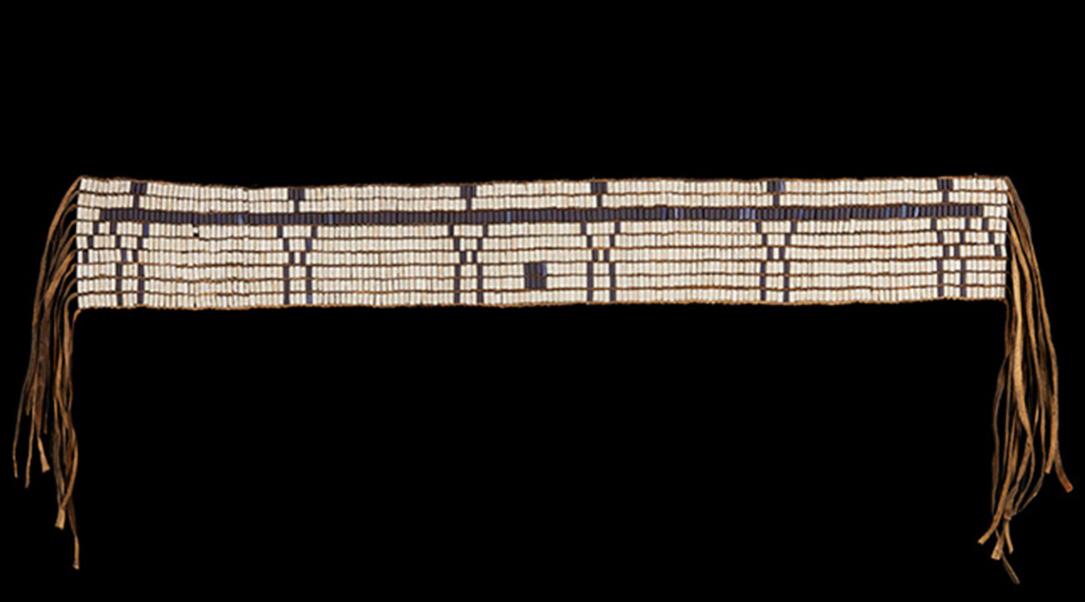

The Women's Nomination belt, is representative of when women have the task of selecting new male representatives of individual clans amongst the six nations, which make up the Rotinoshionni confederacy. The women's nomination belt is still in use today, and it is one of the most important wampum belts in Rotinoshionni and U.S. history. Jigonhsaseh, the first clan mother, helped form the Rotinoshionni confederacy and its oral constitution, known as the Kaianerekowa, which is said to have inspired the creation of the U.S. Constitution.

generational knowledge that has been encoded into the foundation of the Kaianerekowa, our living body of principles, then we can begin to address the root of the problem we face as Onkwehonwe people in this modern day.

Knowing that our practices have been in place long before the first colonizer stepped foot on our shores, and that only the mindset of our people has changed due to all the assimilative tactics implemented across turtle island; it is apparent that we need to reclaim and regulate our familial structures and encourage our people to think critically in order to determine for ourselves how to bring generational wealth back into the lives of our families.

There is a lot of unlearning that we must do, and it starts with understanding the origins of patriarchy and how it continues to impact human life.

There is an understanding amongst those who continue to practice the Kaianerekowa that no human can control the natural world. As the natural world continuously moves through cycles, so do we as a natural people. Those who have maintained their connection to mother earth are aware of these natural cycles.

When we talk about patriarchy from an Onkwehonwe perspective, It is seen as nothing more than a mechanism to disempower one gender in particular in order to gain control over our bodies, lands, and resources.

It was only through “Interpreted Jurisdiction” that colonizers were able to make claim on lands that were left in its natural state, because they appeared to be uninhabited by humans. When in fact, we as Onkwehonwe are a natural people,

who’s guiding principles are to leave the land better then when we came.

The Kanienkehaka were historically a seminomadic people who would build villages throughout our territory to sustain our families for a period of time. The villages would then be moved elsewhere to allow the land to rest. Now, we are forced to live on small plots of contaminated lands, degraded by corporations who have no connection or concern for the land or our future generations.

A modern-day example of how patriarchy is still in effect is the functioning BIA Tribal Council, established on just about every “federally recognized” Tribal land allotment, continuing the notion that we are a bunch of domestic dependents incapable of governing our own bodies, lands, and resources.

After the attempts at completely exterminating us had failed, Church and State attempted to completely assimilate those of us who remained so that we would forget who we are, forget our songs, our language, and our traditional ecological knowledge. Once they realized they were unsuccessful in completely assimilating us into western society, Church and State went on to actively disempower and sterilize our women to the point that now our own people have begun to model the same behavior, replacing our roles and responsibilities with power and control.

Once this issue can be acknowledged within our own familial structures, then and only then will our people become empowered and inspired to fulfill their roles and responsibilities once again.

“When we talk about patriarchy from an Onkwehonwe perspective, It is seen as nothing more than a mechanism to disempower one gender in particular in order to gain control over our bodies, lands, and resources.”

By Caperton Tissot Saranac Lake, NY

We haven't really lost winter with its lacy white woods, air sparkling with crystals, tracks of rabbits, fox and hare, the peace, the stillness, a white Christmas. We do miss the rugged challenge of cold, the pleasure of snuggling into down jackets and underneath quilts, the satisfaction of gathering by a wood fire while fierce winds batter the windows. But this loss of rugged white days will pass. They will return. Yes, blizzards will return, just like the old days, bringing snow-filled streets and snow-laden trees, the cheer of school closures, sleds whooshing down the nearest hill, red-tipped noses, laughter and ski trips through bowed conifers. It's just a fluke, this warm weather. It won't happen again. Winter will return in all its festive glory.

And yet, damn it, this change of weather is all due to a warming planet, to burning fossil fuel, to oil companies' refusal to promote renewable energy. Management of those companies knew what they were doing. For years, they and others have lied about their role in accelerating climate change. And now our massive carbon footprint stomps on the earth with total disregard, creating devastating floods, fires, tornadoes and hurricanes, the loss of cherished lives and homes. Politicians knew it was coming, we all knew it was coming. Scientists had predicted it, yet little or nothing has been done to solve the problem. And now change is here to stay. A culture of ruggedness, a tradition of helping each other when the going gets rough, a booming winter economy, all is disappearing. Northern folks have always celebrated the season. Now jubilation is washing away. Makes my blood boil.

If we just create more publicity, provide more facts, refuse to invest in carbon producing industries, if we vote an environmentalist for president, make global warming the #1 ballot issue, maybe all this will be reversed. If we stop turning a blind eye to the climate problem, then maybe winter will stop melting into pools of mud.

It's too late now. Heartbreaking. Cloudy, gray and soggy outside when there should be snow. Dark skeletal trees, ground covered in dead leaves, even the houses seem draped in mourning. It crushes the spirit, robs us of winter's joy. This morning the weather service issued a fog alert instead of a snow alert. Hard to look out the window; all is murky out there, visibility reduced to nothing. This is the North Country, for God's sake, not Florida. Our tourist economy is dead, folks laid off from work, restaurants closed. Even wildlife is affected. Snowshoe hares and ermine in their white winter coats stand out against the dark earth, easy targets for enemies. How tragic the death of traditional winters.

But we best get used to it, learn to accept the new reality. December, January and February too, have mostly been gobbled up by autumn. We will find fewer occasions for skating, skiing and sledding. There will be only rare days of woodlands draped in white lace lit by sparkling crystals and blue light shadowing the snowy landscape as the sun sinks behind mountains. Perhaps no more white Christmases. What do we do? Stop embracing the seasons, stop celebrating? I think not. There will be winter months but they may be warm and green. Let us accept what is, for time cannot be turned back. The moment has come to open our hearts to joy so we can dance again.

The steps of grieving behind us, arriving at acceptance, we can now move forward, climb out of the darkness, move on with our lives. The time is now.

By the Bay of Fundy

Mary Dingee Fillmore Burlington, VT

Every soft grey is here like a dove’s shaded breast: it’s in the sea and sky, waves meeting clouds.

Sometimes the horizon’s clear: a distant charcoal line, sometimes a mere idea in the shifting fog.

Once, my hair was grey but now it’s white until the moon rises turns it silver too

like the waters she calls to the sky

Tyler Barton Saranac Lake,

NY

Sing my story to me like a shard

It’s hard here Had to move a lot “poetically and profoundly”

I was renting stories about renting Other people’s comments That I had written about I have rented for art

I attended my doctor’s poem That small flames are licking the sides of

On Occasion I Am Reminded of Honey, Feather, William Camponovo (’23) Brooklyn, NY

On Occasion I Am Reminded of Honey, Feather, scalpel, whip, pre-determined objects laid in front of the performer inviting any viewer to inflict pain or pleasure as they might dare, if. Come on. It was pain. Always pain. For six hours they went, whipping her, cutting, pricking, suspense and delivery, body and hair, with scissors. Spectators observed a gun on the table and loaded a corresponding bullet to prepare

simply: they could. This world. Our markets writhe in post-foraging apathy. Unsold half-rotted produce from soggy morning air

pecked at by the curious birds longs for municipal pardon. Silent Giordano Bruno—positioned in the central square—

defecated from above, micturated from below, stands in his pile of shit. Marble beneath worsens for wear, and our alfresco, civic monuments await due reverence in the form of abusive prayer.

Oh, I’ve since come around to thorns having beauty, penetrating the performing artist’s patient stomach, bare.

On occasion I am reminded of honey, feather, scalpel, whip, I’ll proceed to tell you about this violence. It is only fair.

Given such bounty of terror in this plane, it would be selfish not to share.

Cut melon—ripe, moist, flayed—drips in uncanny temporary second skin. Your prosciutto gives glib asylum, swaddling there.

William Camponovo (’23) Brooklyn, NY

Raise this vertical flag instead of speaking and I will know you by your flapping. I will play an imaginary theremin that responds in kind, arms akimbo, gesture—“Ta-daaaaa!. . .” of our melismata, change it up, go lower, like scene in the movie when the corrupt cop brings his finger and thumb to his face, forming a “C” around the curvature of mouth. C for “contemplative.” C like “Scalawag,” silent S.

Someone else—not you, not me—fishes out the baby rattle from the grand piano and all are relieved finally to hear our old favorites, but you and I do not like how they sound without the baby rattle so we plead put it back. . .

A low-flying pass of a jet airliner overhead and the glasses in the cupboard kiss frantically, wildly. Porcelain miscegenated, they throw it all out. Watch this you say, deflating a balloon I blew by sucking in its air. “Violence and puns! Violence and puns!” you imitate. Uncanny. Good Riddance, Part Four, you title it.

You spit at fountains in wintertime so they might remember the sensation of running water. I remember never to forget when crossing one-way streets to thank them for doing half the work for me. Public servants we are: let us go to work. Who are you to tell me the sun and I are too hungover to perform today. The bed needs its time to rest, too. We are in this separate together.