The following is a distillation of transcripts prepared in 1984 by Nick Marchant and Jeremy Addis for“The Future”,the intended final chapter of their book“Kilkenny Design – 21Years of Design in Ireland”.It never made it to the finished book partly because time ran out for the publication deadline and partly because some of the predictions were considered to be politically sensitive. The“missing chapter”,as it was referred to, is presented here for the first time.

In this context,it may be of historical interest to note that in 1983,Nick started writing a book with the title“Design in a Developing Economy” as a personal venture.The following year,it was adopted as a vehicle for promoting the KDW's 21st anniversary and developed under its new title with Jeremy's professional assistance.Our aim however remained to make the book less or a celebration of KDW’s work and more of a demonstration of what a relatively small investment in design could achieve in influencing the quality of industrial growth.

In considering the future,we looked to the 1990s and,at most,the millenium.Since we now live in a future well beyond that,it is worth remembering that in 1984 personal computers and word processors were in their infancy and not available to the authors of this book who prepared transcripts in hand writing and with an aged typewriter – and no one of course, had heard of the“information super highway”,later to be known as the internet, which of course changed everything.....

Nick Marchant,November 2025

It is easy to suppose that a small country, new to nationhood and to industrialisation, can at best only trim its sails to the winds of international economy and industrial change, and cannot determine its own course.

It is true that Ireland suffered staggering blows in the trade recession of the early 1980s. Encouraged by the beginnings of industrial success in the 1960s and then by its acceptance into the European Economic Community, it over-borrowed in the following decade.While tasting the first fruits of economic independence from Britain, its currency was still tied to sterling and the expectations of its people were no less firmly tied to British standards of living, of wages and of social welfare. So that within Ireland, every factory closure, every redundancy, every falling-off of export markets or increase in energy costs had a doubly depressing effect.

Furthermore, it is on young people that unemployment falls particularly heavily and Ireland has by far the youngest population of all European countries with about half of its population under the age of 25.

And yet to be small among large industrial nations, to be new to industrialisation and to be young are all ultimately advantages: each in its way provides flexibility and readiness for change that larger, more developed economies, lack. In fact everything that seems to make Ireland weak and dependent may equally be shown as enabling it to pioneer.With a total population less that of many cities in larger countries, it nevertheless boasts all the organs of state of the most developed, but with the advantage

that each is comparatively small and flexible so that new strategies can be implemented relatively easily and quickly within and between them.

In its first two short decades, KDW has seen, and in many ways epitomised, the flexing of the muscles of a country that in less than a lifespan has pulled itself from a backward agricultural province to a state no less respected in its trade than in its political contributions to the United Nations and the European Community and in its cultural influence.

Ireland's very lack of raw materials and its now imperative need to earn its keep and pay its debts by utilising its own main resources, labour and agriculture, may mean perforce that it is embarked on courses that other countries, more slow to react, must eventually follow.

When recessions bite, there is the regenerative tendency for small industrial enterprises to spring up in the aftermath of major collapses: enterprises that naturally seed themselves where the ground is fallow, capitalising on a skill or a particular gap in the market.

Ireland's Industrial Development Authority saw this coming and provided for it with imagination and KDW has been well placed to add to that support in its special spheres of influence. It has found that by adopting a holistic approach to an enterprise's design needs and deploying a multi-disciplinary design team, the needs of small enterprises can be precisely met. KDW's immediate future is closely bound up with the demands

of such firms together with those of Ireland's emerging larger industrial enterprises as well as inward investment by overseas manufacturers.

At the time of writing, the growth characteristics of Ireland's industry point towards a less wasteful, more resourceful structure and one that by its nature tends to lean on the sort of improvisation design, connection making and market-tailoring that recur time and time again in the projects illustrated in this book.

In other countries the function of design promotion agencies is perhaps, by instigation and encouragement, to make themselves unnecessary. In Ireland, the relative smallness of industrial units makes it less possible for each to afford its own design and product development resources and it is clear from KDW's own rapid change and development and from the reliance of its clients on help not just in design but in ancillary fields, that there will be a steadily growing need for design resources in Ireland in the future.

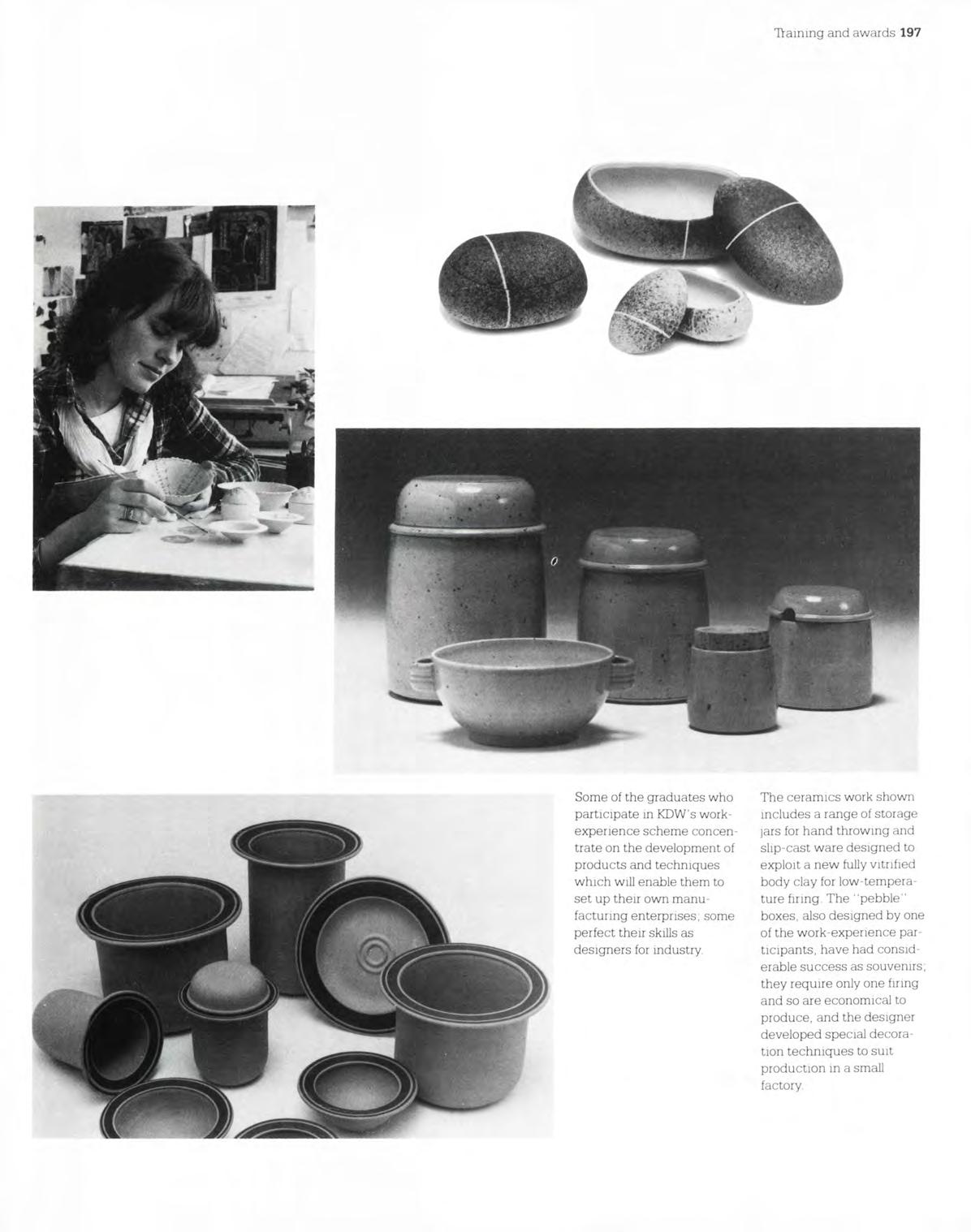

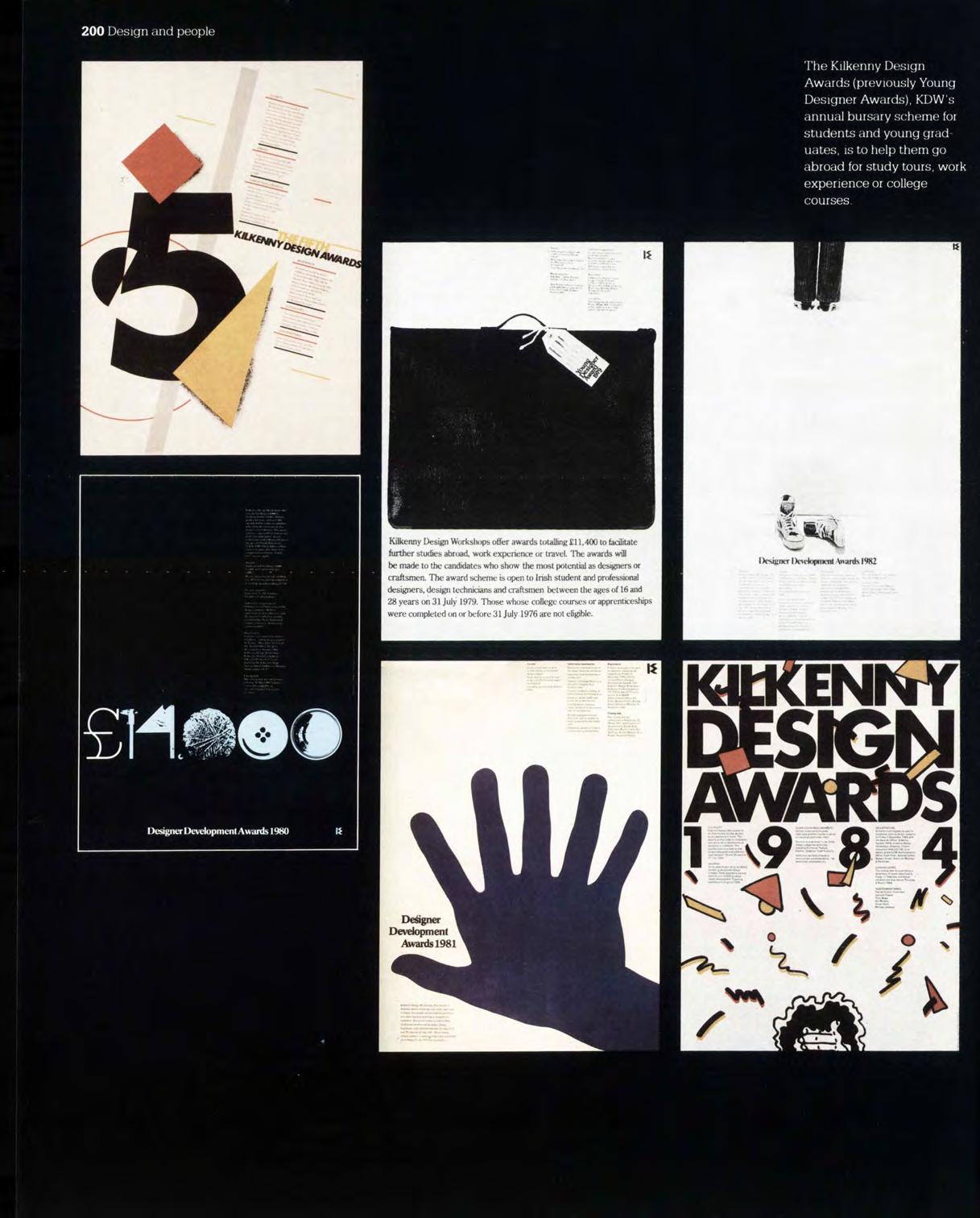

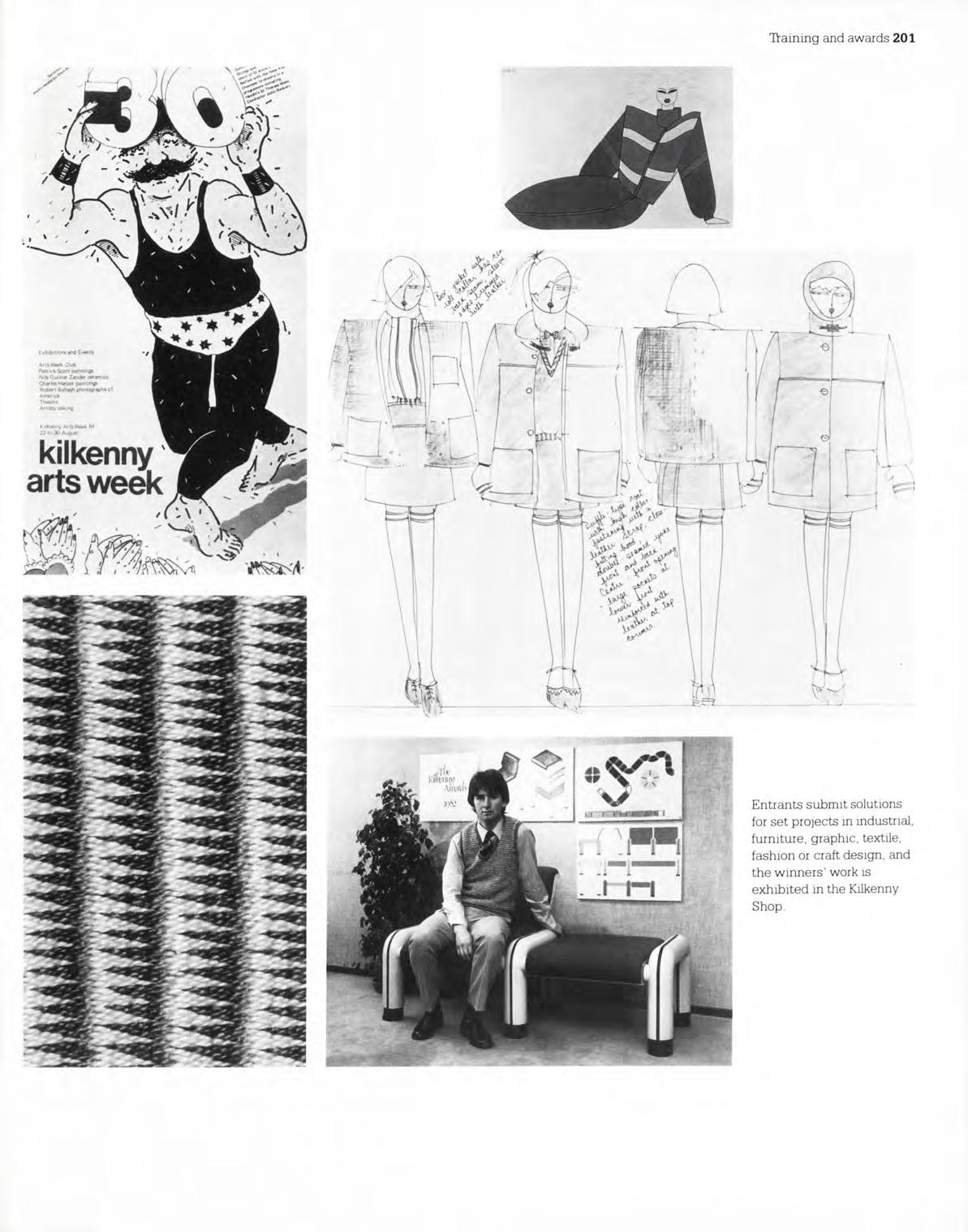

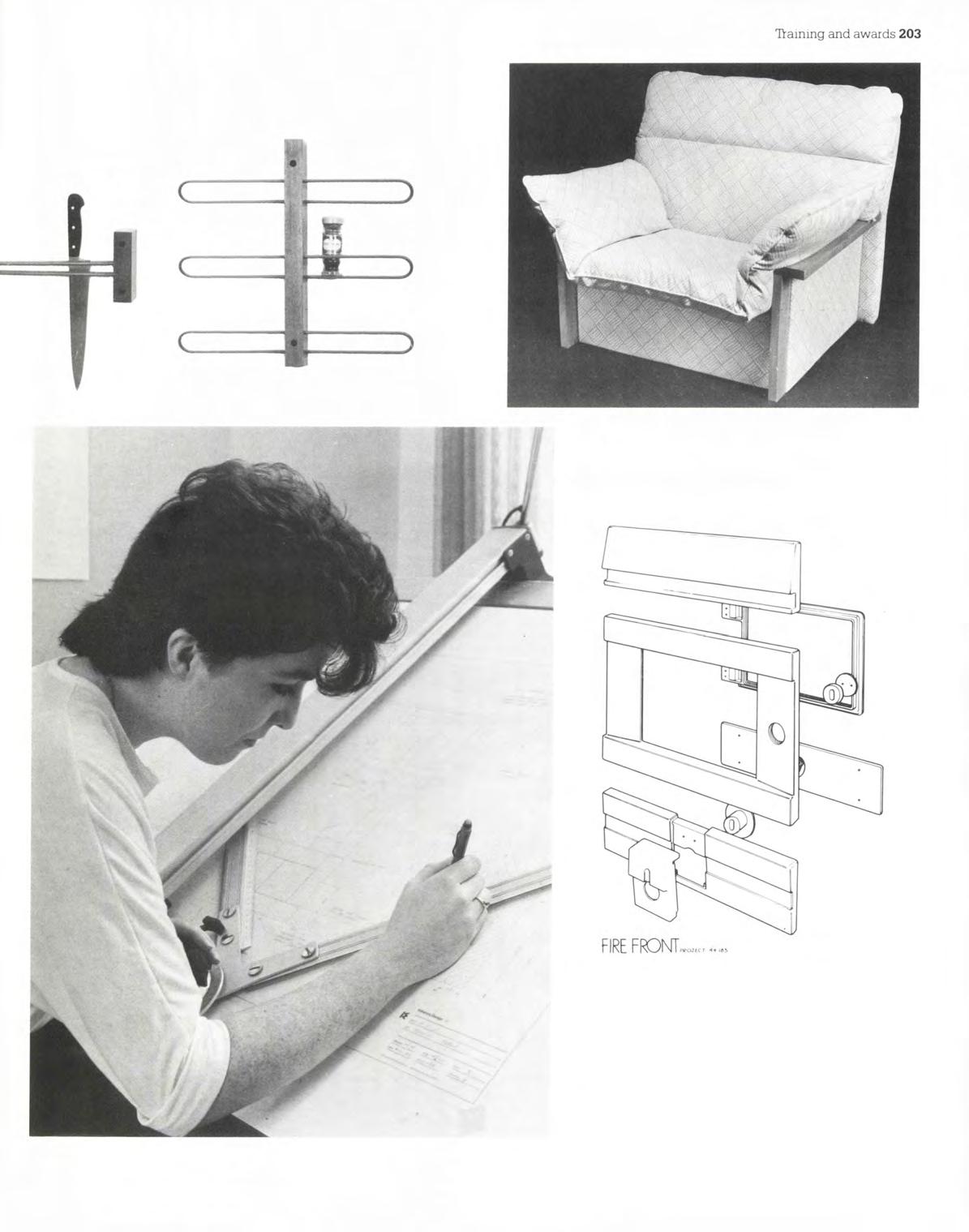

However, there are other factors at work: In the late 1970s/early 1980s there was a growing awareness of the need for industrial design education in Ireland in response to the growth of industry and the encouragement of KDW, although the field was still relatively nascent. In 1984 a Degree course in Industrial Design has been validated at the National College of Art and Design (NCAD). This is likely to significantly boost the future design profession in Ireland and help to enable the transition from state design intervention to

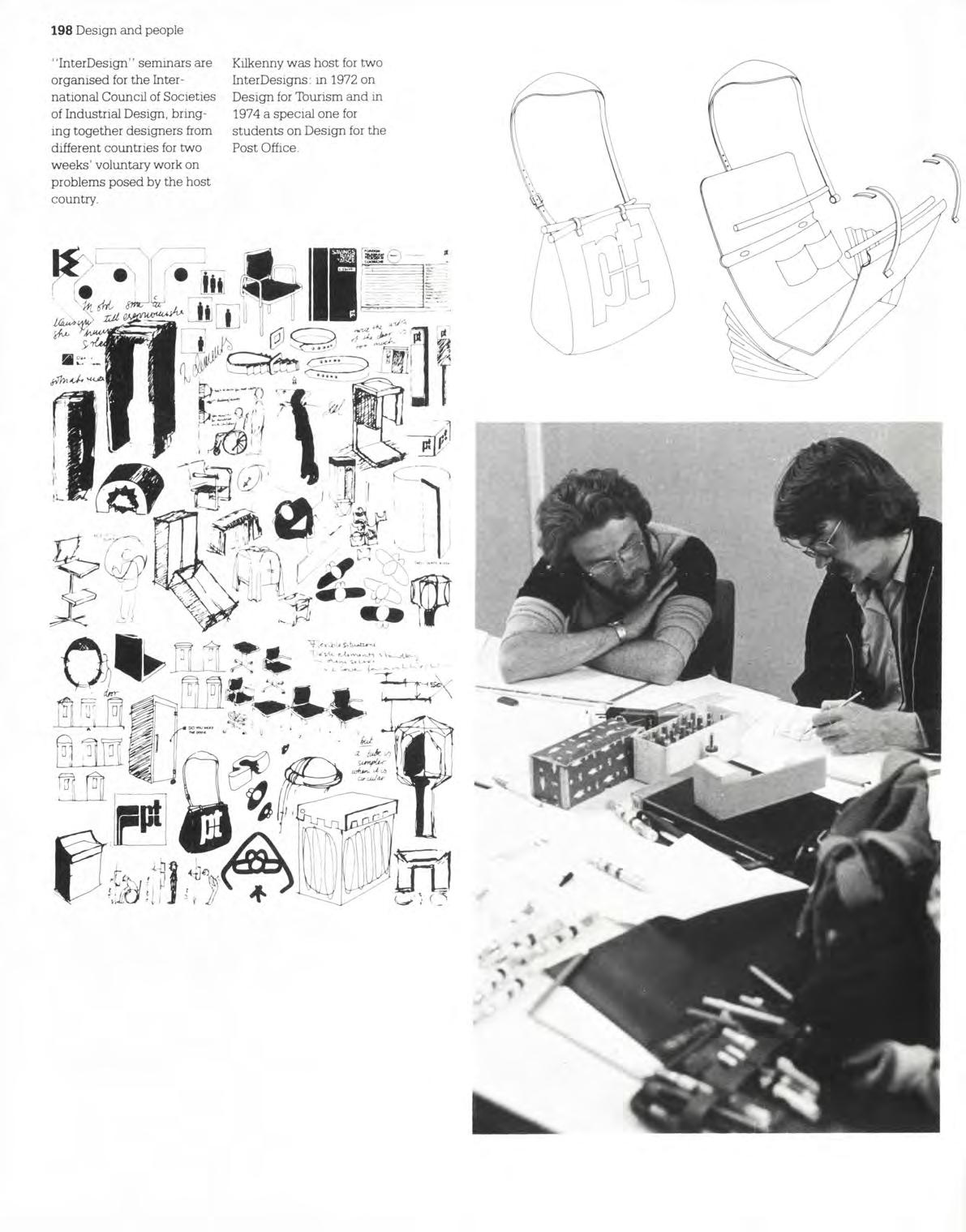

private practice.Years previously, in the early 1970s, KDW had started to provide work experience to young Irish students wishing to make a career in design, formalising this in 1978 by launching its Butler House graduate training scheme, with a similar and complementary aim.

It seems inevitable therefore that the design services provided by KDW will, some years hence, become replaced by, or partially replaced by, or in some way transition into, private enterprise. Hopefully such a transition would be carefully planned and orderly without loss of expertise or facilities. However, the need for some degree of state funding of design, particularly for small or emergent enterprises seems unlikely to be obviated. Private design agencies are unlikely to be willing or able to work at reduced rates for small companies who are unable to finance their basic design needs themselves. For Irish industry with its bias towards firms that are smaller than average for the type of business that they are engaged in, an ongoing solution to this problem is likely to be essential.

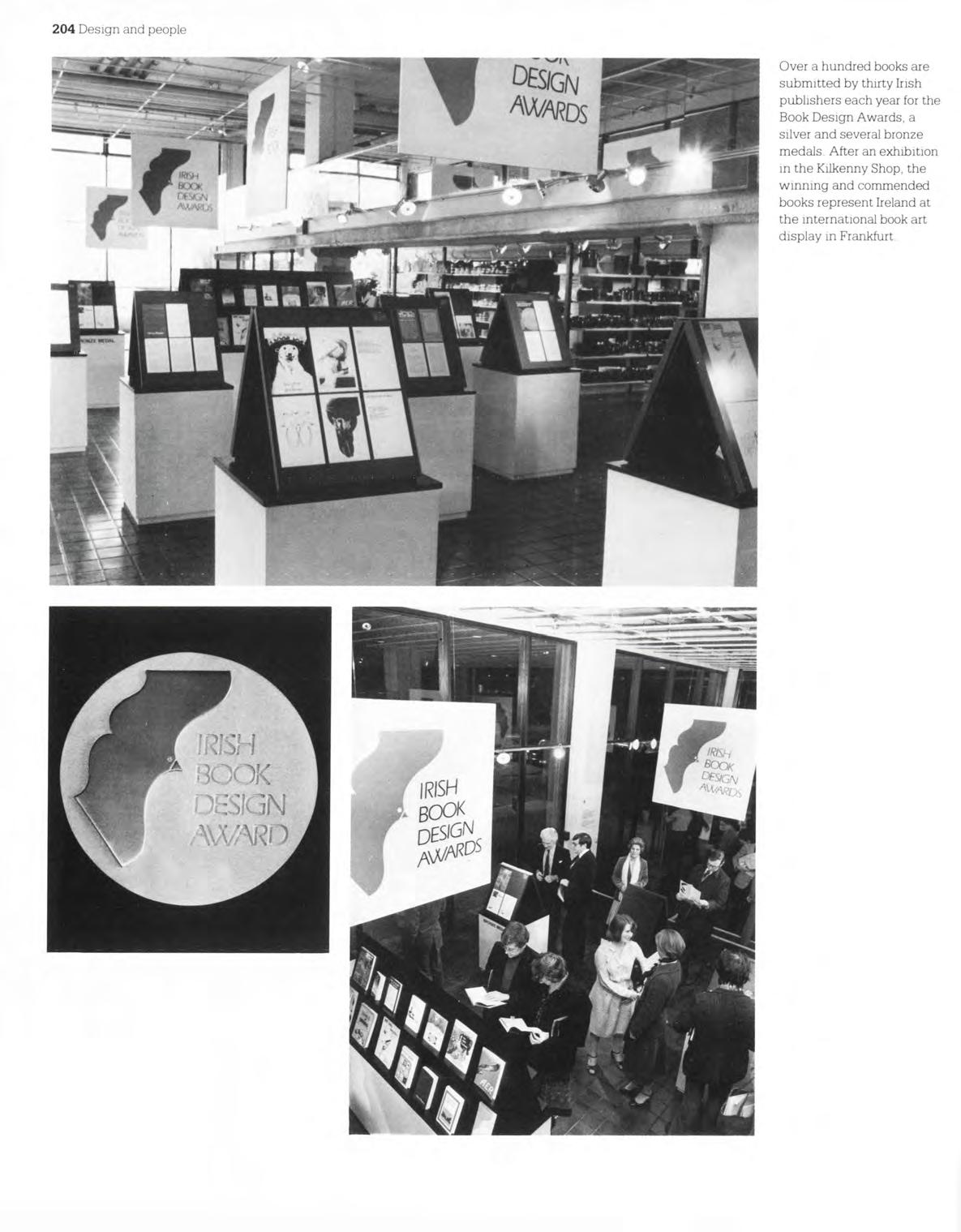

Design services have always been central to KDW's offering but are not the whole story. The promotion of design, not just to industry but also to the general public, has also been an integral part of its remit and is completely independent of whether design services are provided by the state or by private practice. In other countries, including Britain and many other European countries, design promotion agencies are provided by the state and organise exhibitions and other events to demonstrate the value of design. In fact, of the 34 nations

that belong to the International Council of Societies of Industrial Design (ICSID), 22 have state assisted design promotional agencies. In “Design in Ireland”, the 1961 report of the Scandinavian Design Group in Ireland, the authors emphasised the need to raise and nurture the public interest in design: “One cannot expect to alter the standard of Irish product design if, at the same time, a home market is not created for the new, quality products.” From the outset, KDW has therefore insisted that good design performance in industry is to be found as a direct corollary of critical design awareness among its potential customers and consumers. One thing that has made KDW unique internationally is that it combined this role with the provision of practical design and technical services to industry but if its design services are privatised, some state funding of Design Promotion is still likely to be needed.

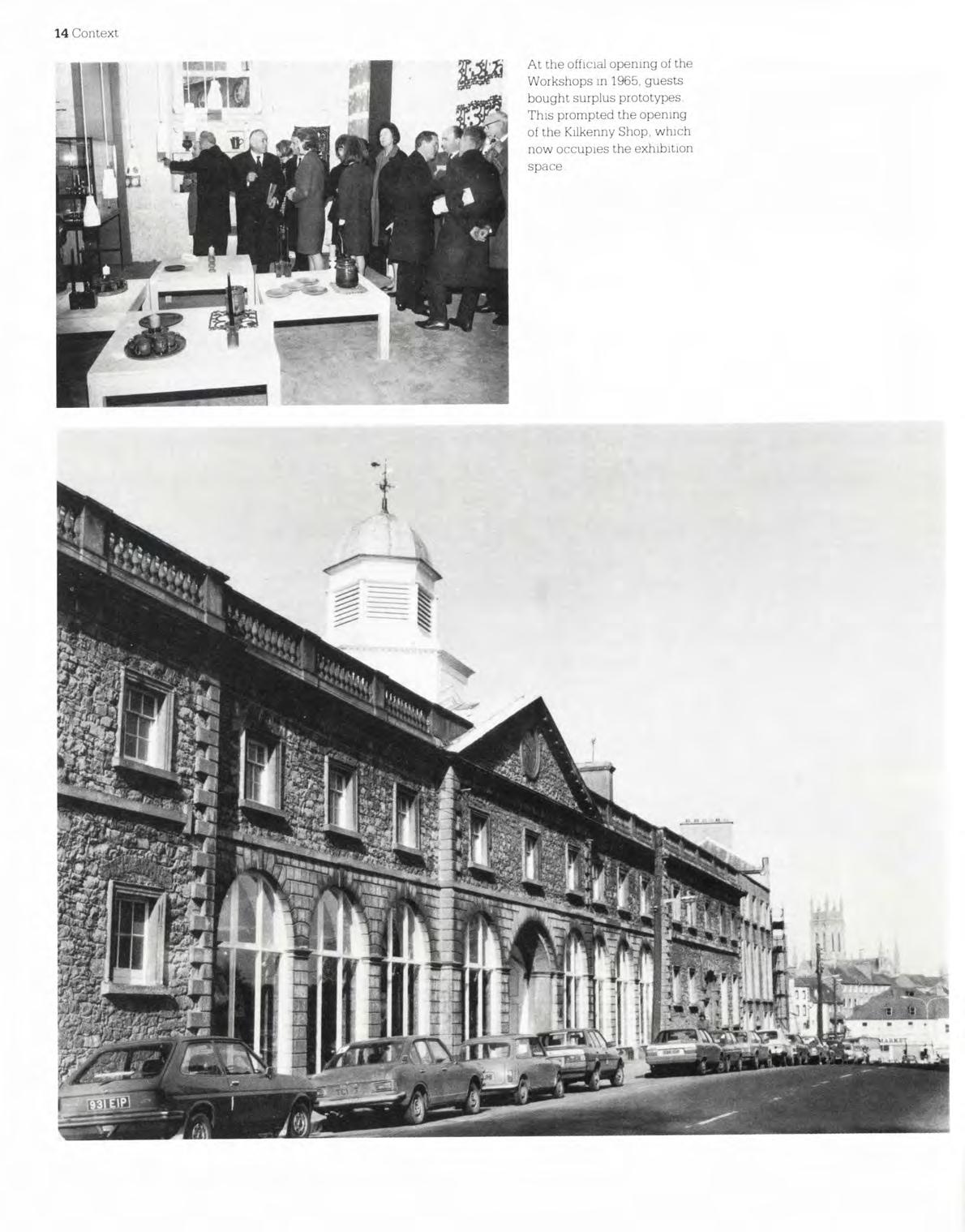

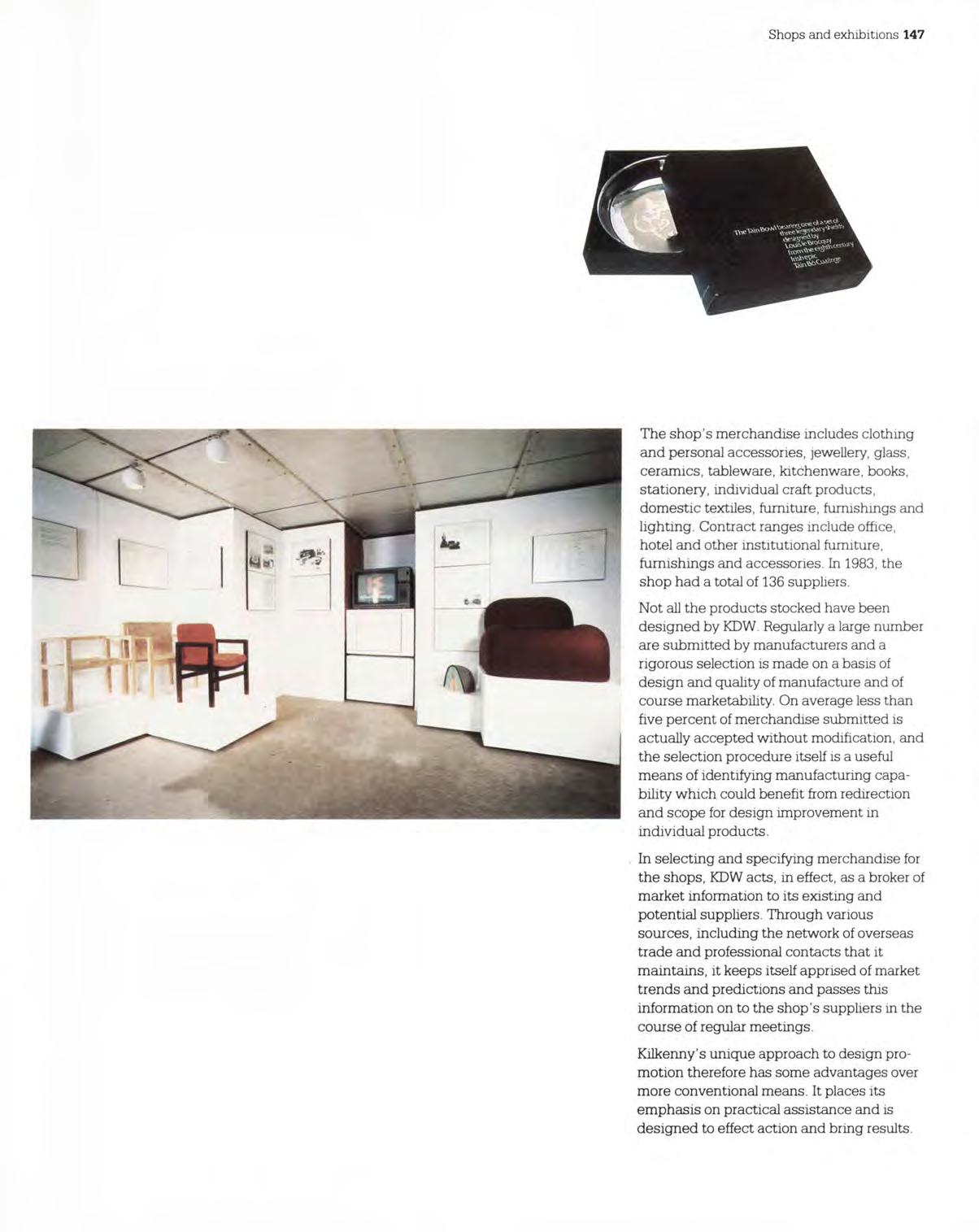

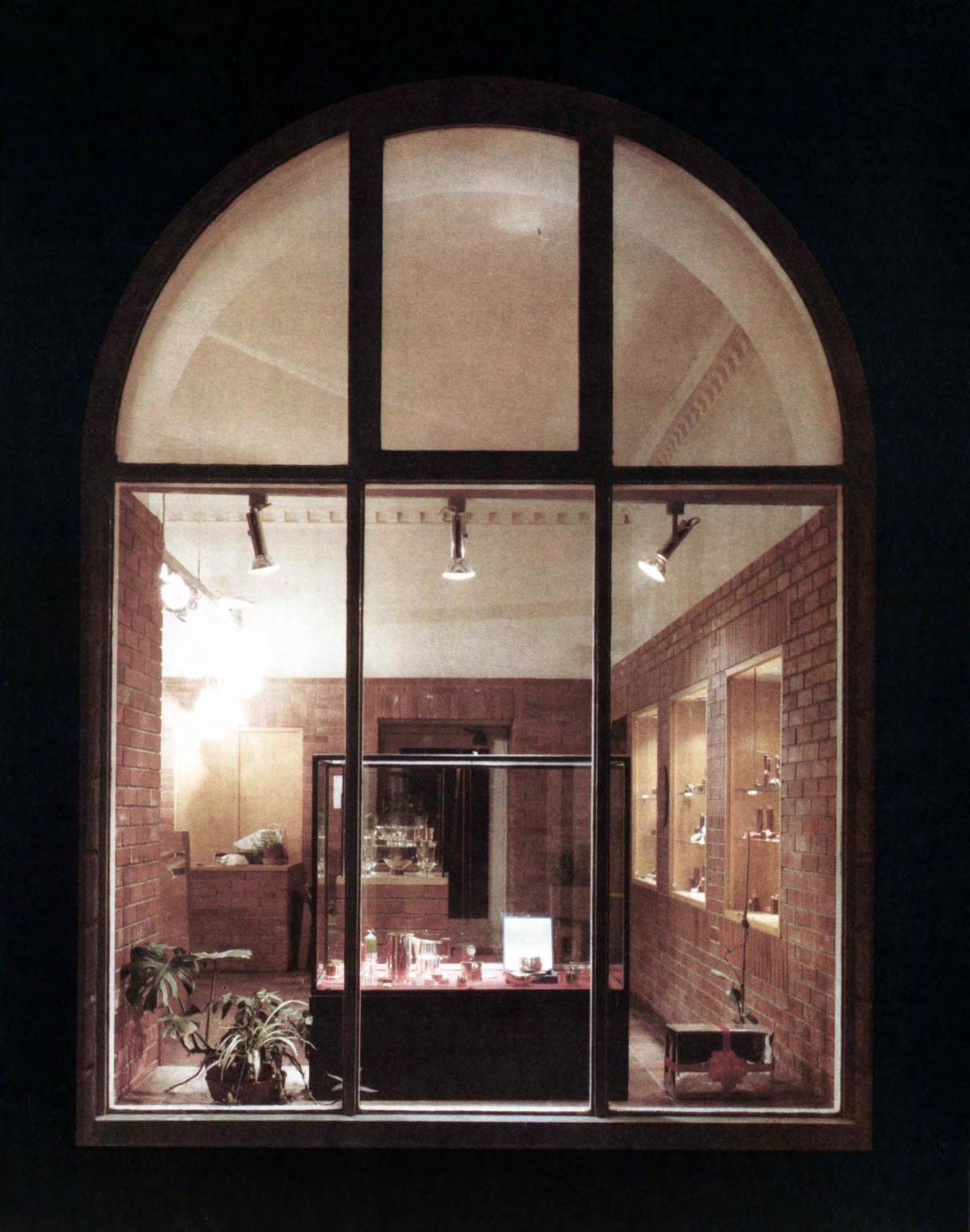

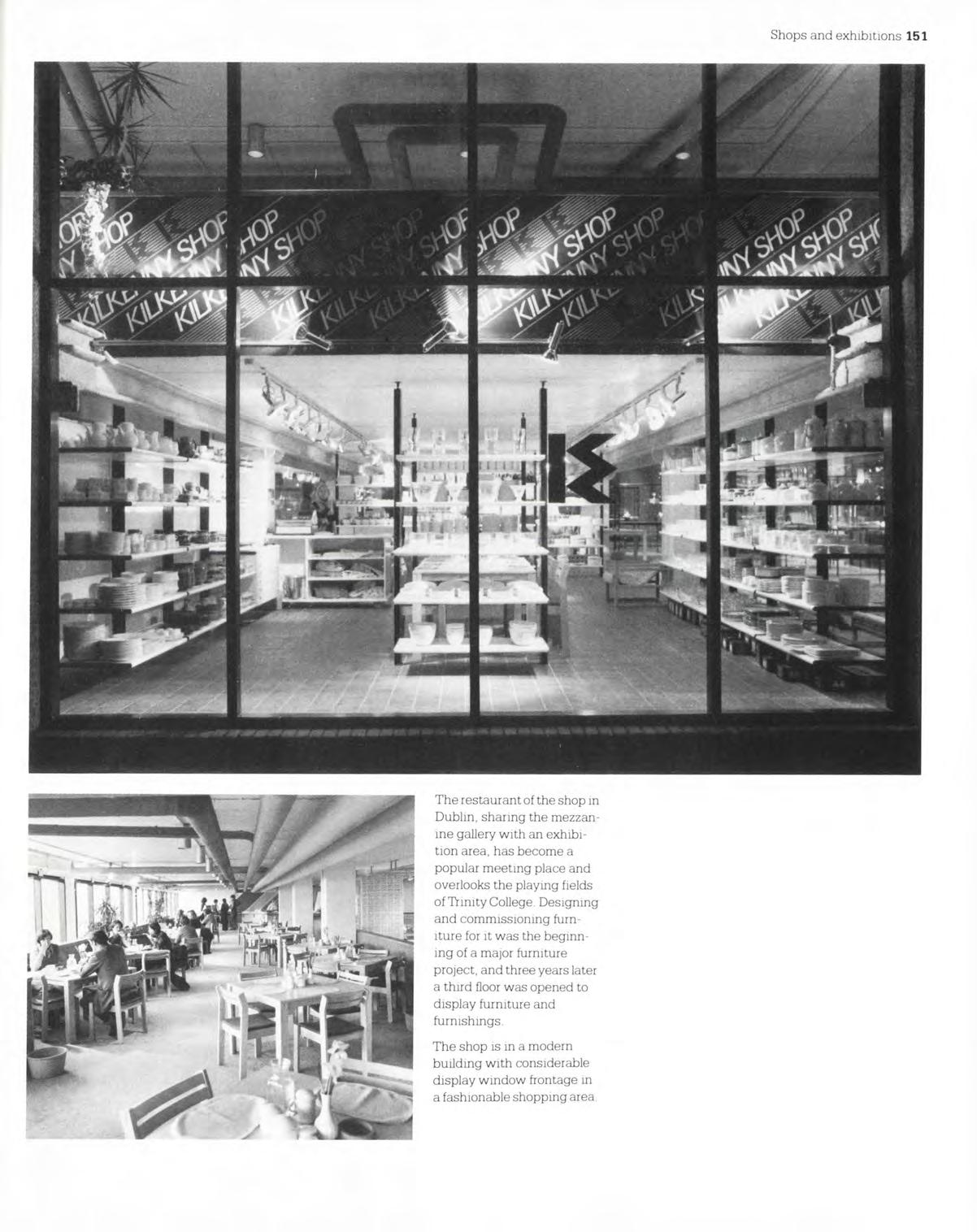

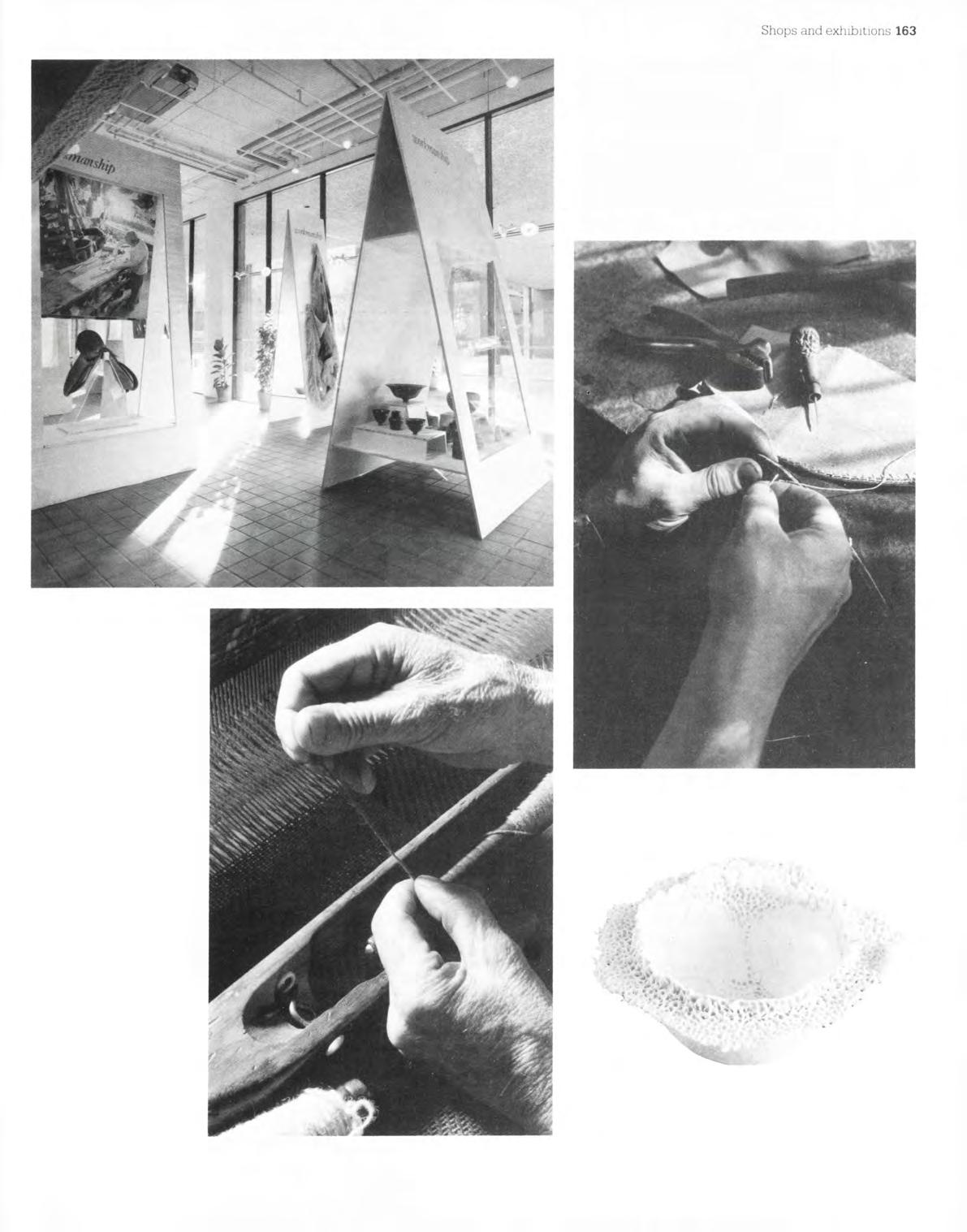

At the consumer level, KDW raises public design consciousness through the operation of permanent retail exhibition centres, the presentation of Irish and foreign design exhibitions, the provision of lectures and the operation of a library of design reference material.

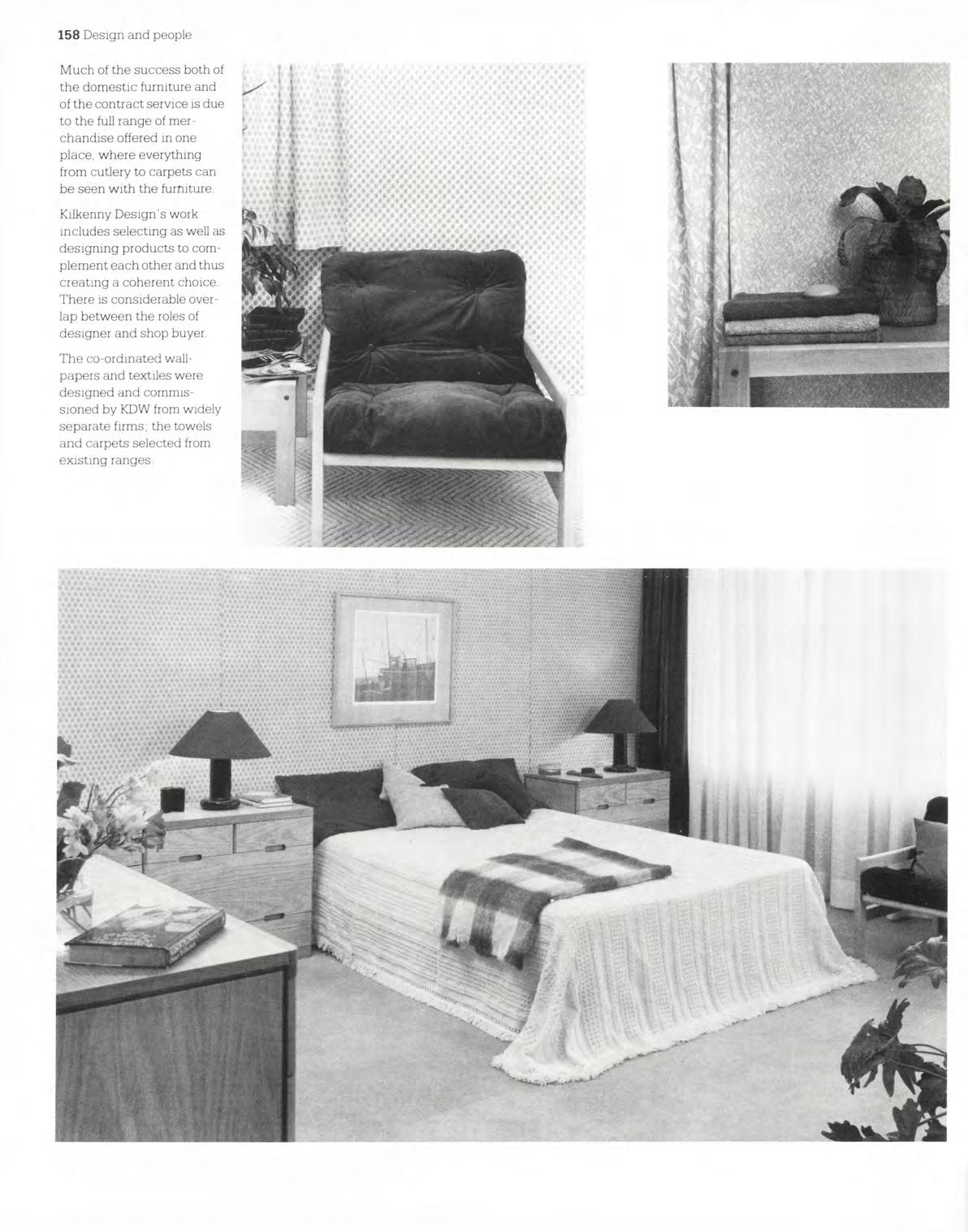

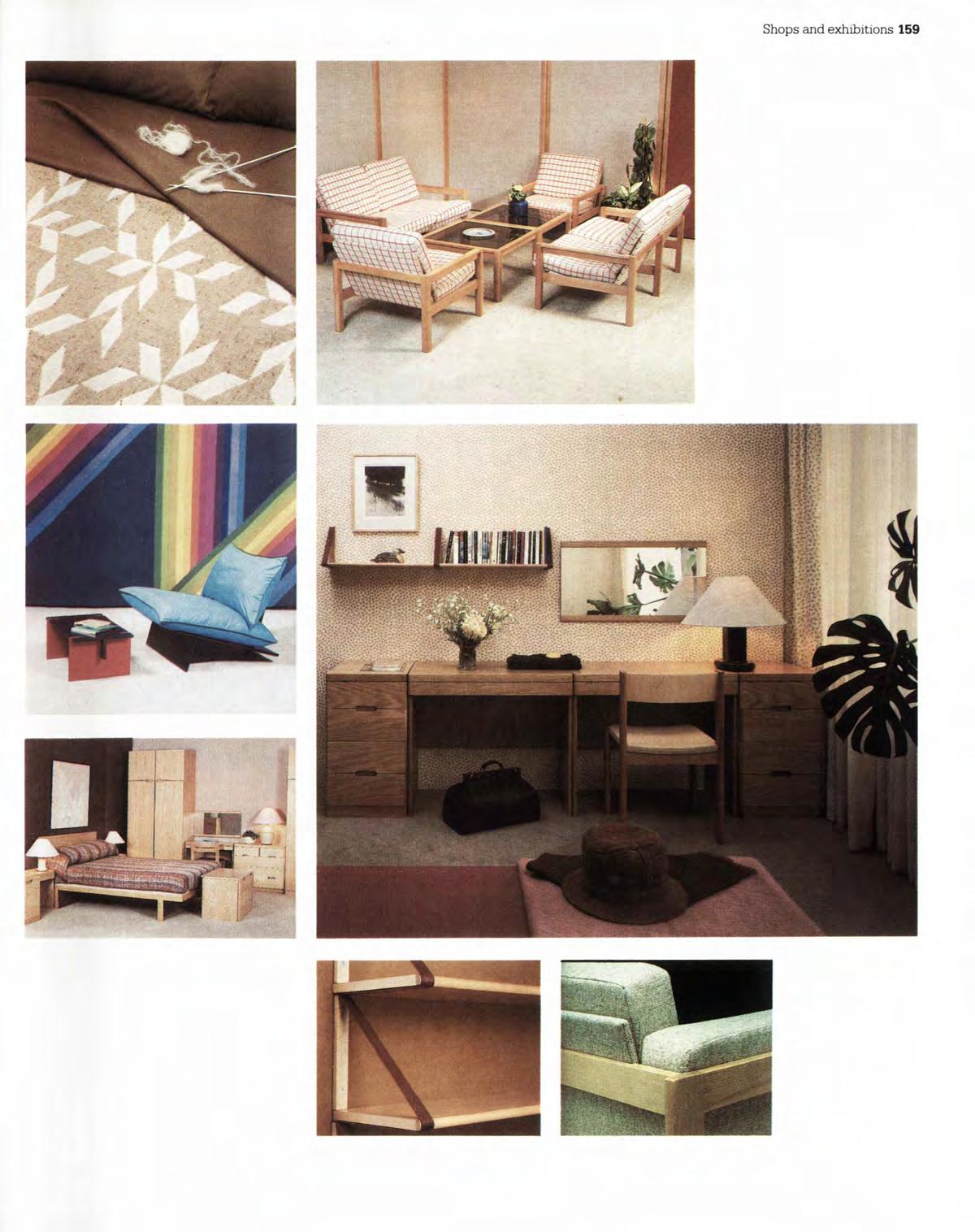

The Kilkenny Shops – which present to the public a cross-section of the best of Irish design and workmanship in useful, everyday products – have been particularly successful in connecting consumer need with manufacturing capability but they do much more than that. Importantly, they are key tools in market led product development. They are not merely

commercial undertakings. They give shelf space to promote and prime the market for new products. This includes craft products where the Kilkenny Shops act as a valuable proving ground for crafts people. It also includes industrially produced consumer products such as furniture where the ability to sell through the Kilkenny Shops and the ability of KDW to also wholesale abroad has been a powerful incentive for Ireland's manufacturers. Some government grant assistance is required for the shop to undertake these product development roles but it is an extremely efficient means of assisting industry and craftspeople. It is to be hoped that the value of this unique initiative will be understood in the future and the essence of the Kilkenny Shops preserved in a non-commercial context.

In summary therefore, there are parts of KDW's role that are likely to change in some way or be phased out at some time in the future as its objectives are met, enabled by the growth and development of private enterprise. Practical design and technical assistance are chief among these. There are other parts of KDW's role, such as Design Promotion, that are much less likely to become redundant and are likely to need to be maintained by the state. The future of the Kilkenny Shops may largely depend on their ability to continue to steer the difficult path between commercial and noncommercial activities, their strength depending on the marrying of the two. The big question of course is whether KDW, with its complex matrix of interrelated activities, is only viable as the sum of all of

its parts. Whatever the outcome, Kilkenny Design Workshops is likely to remain world renowned as an unique initiative in kick starting design in a developing economy.