69 minute read

AADMD

Reporting the Evolving and Increasing

U.S. Population With Disabilities

Advertisement

By H. Barry Waldman, DDS, MPH, PhD Steven P. Perlman, DDS, MScD, DHL (Hon), Rick Rader, MD, FAAIDD, FAADM Allen Wong, DDS, EdD, DABSCD

In the past, except for an aged grandparent, individuals with disabilities “did not exist.” They were sequestered in outof-town institutions or in backrooms of homes. Health professionals had little to no formal educational experiences to provide needed services for these individuals.

Change began in the final decades of the last century. Geraldo Rivera’s 1972 report on “the horrors” in Willowbrook State School in New York State for individuals with mental and physical disabilities became the national catalyst to awaken the public to the desperate needs for change.1

The eventual increasing awareness of the numbers of youngsters and the not-so-young with disabilities filled professional journals and the general public literature. Movies, television and computer reports now provide a staggering reign of information about the growing population of individuals with disabilities and their needs. Nevertheless, the health profession schools did not adopt formal requirements for preparing the next generation of health providers to care for individuals with disabilities.

For example, it was only by a nefarious act by one of the writers of this paper (HBW), that U.S. dental and dental hygiene schools are now required for accreditation purposes to provide didactic and clinical experiences for the care of individuals with disabilities.2

The task is how to compact and highlight specific information to ensure an awareness of the needed services for the increasing numbers of individuals with many disabilities who live in our communities.

An estimated 3.5 percent of people with disabilities live in institutional

Table 1

Civilian population with disabilities: 2010-2020 3 Total U.S. Population population with disabilities Proportion

2010 308,291,000 38,463,000 12.5% 2015 320,399,000 42,050,000 13.1% 2020 328,294,000 44,862,000* 13.4% * Living in the community

Table 2 Five states with the greatest NUMBER of civilian persons with disabilities: 2020 4

group quarters, which include nursing facilities/skilled nursing facilities and adult correctional facilities.3

The massive 2020 and 2021 University of New Hampshire Institute on Disability Annual Disability Statistics and Demographics are examples of the critical and yet overwhelming data that are now available.3,4

There are situations where summary highlights may be of more value to demonstrate the dramatic developments in the numbers and distribution of individuals with disabilities.

For example:

1. Between 2010 and 2020, there was an increase of more than 6 million U.S. residents with disabilities (from 38.4 to 44.8 million individuals). (Table 1) 2. In 2020, there were 4.4 million residents with disabilities in California. (Table 2) 3. In 2020, 19.6% of the residents of West Virginia were reported to have a disability. (Table 3) 4. In 2020, among U.S. residents (with wide ranges by states): • 27 % had hearing disabilities • 18% had vision disabilities • 30% had cognitive disabilities • 49% had ambulatory disabilities • 20% had selfcare disabilities • 37% had independence disabili ties (Table 4) 5. In 2020, among U.S. residents ages 18-64 years, 75% of individuals without disabilities were employed, compared to 37.9% of individuals with disabilities. (Table 5) 6. In 2020, 12.0% of metropolitan residents, compared to 17.9% of rural residents, had a disability. (Table 6) 7. In 2020, 88.4% civilian residents with disabilities and 87.0% without disabilities had health insurance coverage. (Table 7) 8. In 2020, among civilians ages 18-64 years with disabilities living in the community 45.8% had private insurance 53.4% had public insurance. (Table 8) 9. In 2020, 21% of individuals with disabilities smoked, compared 11% of individuals without disabilities; 40% of individuals with disabilities were obese, compared to 29% of individuals without disabilities; 13% of indi-

viduals with disabilities, compared to 16% of individuals without disabilities were binge drinkers. (Table 9) Let’s not forget about children with disabilities; especially their education. In 2017, about 1 in 6 (17%) children aged 3-17 years were diagnosed with a developmental disability, as reported by parents. Some groups of children were more likely to have been diagnosed with a developmental disability than others: Boys compared to girls. Non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black chilCalifornia 11.3% dren compared to Hispanic Texas 12.2% children or non-Hispanic Florida 14.2% children of other races. New York 12.3% Children living in rural Pennsylvania 14.5% areas compared to children living in urban areas. Children with public health insurance compared to uninsured children and children with private insurance.5 The most common type of disability among children 5 years and older in 2019 was cognitive difficulty. There were regional differences in childhood disability prevalence in 2019, with the highest rates observed in the South and the Northeast and the lowest rate observed in the West.6

Special Education - Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA)

IDEA is the nation’s special education law. Schools must find and evaluate students thought to have disabilities— at no cost to families. To qualify for IDEA services, a child must have a disability and need special education to make progress

Population Proportion of with disabilities total population

4,409,000 3,573,000 3,085,000 2,371,000 1,857,000 Table 3

Five states with the greatest PROPORTION of civilian persons with disabilities: 2020 4

West Virginia 19.6%

Arkansas 19.2%

Kentucky 18.4%

Oklahoma 17.8%

Mississippi 17.8%

Proportion Population of population with disabilities

350,000 579,000 821,000 711,000 523,000

in school. While overall, 14.4% of public-school students were served by IDEA in 2019-20, that number varies by race and ethnicity.

White students - 14.7% served under IDEA

Black students - 16.6%

Hispanic students - 13.8%

Asian students - 7.1%

Pacific Islander students -11.2%

American Indian/Alaska Native students - 18.3%

Two or more race students - 15.4%

Although research has shown that students often do better in school when they have a teacher of the same race, just over 83.5% of special education high school teachers in public schools are White, according to the most recent data available, but only about half of all students receiving special education services are White, according to 2017-18 data.7,8

Overall: One cannot truly comprehend the full impact (of the almost 45 million women, men and children with disabilities) on the individuals themselves, their families, friends, and the economy of the nation. While economics may be the obvious first factor, the prevailing emotional realities, demands on the full range of health, educational and social personnel, hospitals, nursing homes, assisted living facilities, special school programs and beyond will continue to increase. Only by a continued comprehensive understanding of the impact on individuals, their families, education, employment potential, the general economy, and so forth in a range of reports, can we expect to plan for the future.

Table 6 Prevalence of individuals with disabilities in urban and rural areas in the United States employed civilians with and without disabilities age 18-64 years living in the community: 2020 4

Metropolitan areas 12.0% Micropolitan areas 15.5% Non-core areas 17.9% Table 4

United States and states with highest and lowest proportion of civilian persons with each disability category (individuals may be included in more than one disability) 4

Type of Proportion of Population disability population with disabilities

Hearing

United States 27.1% 11,926,000 Highest - Alaska 38.1% 32,000 Lowest - Dist. Col. 14.7% 11,000

United States 18.2% 8,032,000 Highest- Louisiana 23.2% 176,000 Lowest- Minnesota 13.3% 86,000

United States 39,7% 7,472,000 Highest - Maine 45.2% 98,000 Lowest - Wyoming 31.5% 24,000

United States 49.4% 21,779,000 Highest - Arkansas 54.6% 315,000 Lowest - Utah 38.2% 130,000

United States 20.2% 8,l916,000 Highest - New York 23.5% 557,000 Lowest - Utah 15.0% 51,000

United States 37.1% 16,356,000 Highest - Hawaii 44.9% 74,000 Lowest - Wyoming 28.0% 21,000

Vision

Cognitive

Ambulatory

Self Care

Independent

Table 5 United States employed civilians with and without disabilities age 18-64 years living in the community: 2020 4

Without disabilities 133,949,000 75.0% With disabilities 7,975,000 37.9%

Hearing disabilities 52.4% Vision disabilities 45.5% Cognitive disabilities 29.1% Ambulatory disabilities 23.9% Self-care disabilities 14.8% Independent living 17.7%

Median annual income full-time civilian workers 18-64 years of age:

Without disabilities $50,223 With disabilities $42,504

Civilians ages 18-64 years living in the community in poverty:

Without disabilities 11.9% With disabilities 27.8%

H. Barry Waldman, DDS, MPH, PhD is SUNY Distinguished Teaching Professor Department of General Dentistry, Stony Brook University, NY.

Steven P. Perlman, DDS, MScD, DHL (Hon) is Global Clinical Director, Special Olympics, Special Smiles, Clinical Professor of Pediatric Dentistry, The Boston University Goldman School of Dental Medicine.

Rick Rader, MD, FAAIDD, FAADM, DHL (hon) is Director, Habilitation Center, Orange Grove Center; President, American Association on Health and Disability; Member, National Council on Disability; Board, American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry; National Medical Advisor, National Alliance for Direct Support Professionals; Board, National Task Group on Intellectual Disabilities and Dementia Practices.

Allen Wong, DDS, EdD, DABSCD is a professor and the director of the Dugoni School of Dentistry AEGD and Hospital Dentistry program in the San Francisco area, and is the Global Clinical Advisor to the Special Olympics Special Smiles. He is current president of the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry (AADMD).

Table 7 Health insurance coverage United States and states civilians ages 1864 years living in the community by disability status: 2020 4

With Without disabilities disabilities

United States 88.4% 87.0% Highest - Mass. 97.1% 96.3% Lowest - Texas 78.3% 75.2%

Table 8 Health insurance coverage - United States and states civilians ages 18-64 years with disabilities living in the community by insurance type: 2020 4

Private Public insurance insurance

United States 45.8% 53.4% Highest - Hawaii 61.4% Highest - Dist. of Col. 68.8% Lowest - New Mexico 33.6% Lowest - South Dakota 40.3%

REFERENCES

1. Geraldo Rivera’s 1972 expose of Willowbrook State School. Available from http://www.preservepennhurst.org/default.aspx?pg=1642 Accessed May 2, 2022. 2. Waldman, H. B. I’m a liar and proud of it. Or, my introduction to reality. Exceptional Parent Magazine. 42:20-21, December 2012. 3. University of New Hampshire. Institute on Disability. 2020 Annual Disability Statistics and Demographics. Available from https://disabilitycompendium.org/sites/default/files/user-uploads/Events/2021_ release_year/Final%20Accessibility%20Compendium%202020%20 PDF_2.1.2020reduced.pdf Accessed April 24, 2020. 4. University of New Hampshire. Institute on Disability. 2021 Annual Disability Statistics and Demographics. Available from: https://disabilitycompendium.org/sites/default/files/user-uploads/ Events/2022ReleaseYear/2021_Annual_Disability_Statistics_Compendium_WEB.pdf Accessed May 1, 2022. 5. Zablotsky B, Black LI, et al. Prevalence and rends of developmental disabilities among children in the US: 2009–2017. Pediatrics. 2019; 144(4):e20190811 6. Young NAE, Childhood disability in the United States: 2019; 3/25/21. Available from: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2021/acs/acsbr-006.html 7. Riser-Kopitsky, M. Has the number of students served in special education increased? Available from: www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/special-education-definition-statistics-and-trends/2019/12?utm_source=goog&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=ew+specific+content&ccid=ew+specific+content&ccag=special+education+statistics&cckw=disability%20 statistics&cccv=content+specific+ad&s_kwcid=AL!6416!3!591656523530!b!!g!!disability%20statistics&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIqpOFj7be9wIVkrjICh16FAgnEAAYASAAEgI_XPD_BwE Accessed May 14, 2022. 8. Lee, AMI. What is the individuals with disability act (IDEA)? Available from: https://www.understood.org/en/articles/individuals-with-disabilities-education-act-idea-what-you-need-to-know? utm_source=google-search-grant&utm_medium=paid&utm_campaign=evrgrn-may20-fm&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIyICsx7je9wIV1cqUCR3CBgajEAAYASAAEgJSlvD_BwE

Table 9 Prevalence of individuals in the United States with and without disabilities by special factors 2020 4

With Without disabilities disabilities

Smoking 21.7% 11.7% Obese 40.4% 29.8% Binge drinking 13.1% 16.4%

PART ONE How and Why

I Recently Visited UKRAINE

By Seth Keller, MD

Seth and a new friend My recent decision to go to Ukraine, in light of the current crisis that the Russian Federation has placed upon the Ukrainian people and its government, turned out to be relatively easy for me. I arrived back in the U.S. on Monday, June 12 at 2 am, after spending three flights and what seemed like forever to finally get back home.

I am an international leader in the neurological care of adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD) and have worked for over 25 years in the field. I have worked to advance much-needed education, training and supports for families and caregivers. This was done in a number of state-run IDD institutions. I have worked with community, state and national advocacy groups, and have been schooled on the history of how people with IDD have been marginalized, devalued and segregated—and on how disability rights are an ongoing battle that have to be protected and respected.

The great need for early intervention of someone born with IDDs, and their continuing need for supports—for some, throughout their life time and for them to have the rights like everyone else to be part of society, culture and access to services—has become deep rooted in my sensibilities. The rich history of disability activism has helped people with disabilities gain more access to rights and services, more now than ever in the U.S., and in many parts across the globe. I’ve no doubt appreciated that the U.S. still has far to go in many ways in furthering access to quality services especially medical, psychologic, and oral health, in particular to adults, and that other countries were much further behind in their care of those with IDD. The basic rights to live in one’s community and to be valued as a citizen with worth were not being provided to countries across the world.

An email and then chat with my friend, Marisa Brown, launched my journey and work with Disability Rights International (DRI). Marisa is retired from the faculty of the Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development, University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities (UCDD) in Washington, DC. I have worked with Marisa on a

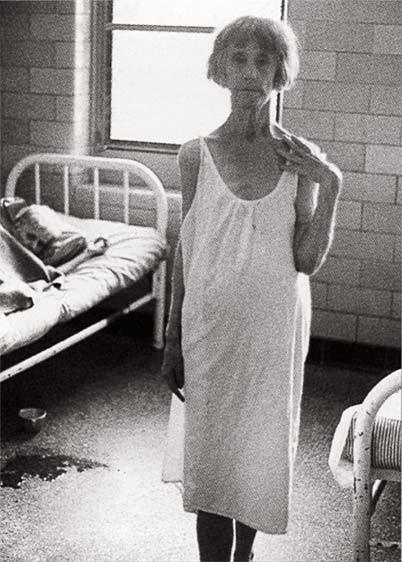

Alone and lack of stimulation

number of projects and deeply appreciated all of her wonderful IDD advoacy work. She also has been working with DRI, and they were looking for someone to go to Ukraine with them who had a strong IDD presence in health and social understanding. I was so honored and appreciative that she thought of me. But before I signed on, I had to appreciate why Ukraine, why now, and what was DRI?

Caring for people with IDD has become a passion of mine for over 25 years. The great appreciation of their healthcare, social, and personal needs is matched by the clarity that they often have a great number of complex health concerns requiring lifelong attention and intervention to help best ensure that the individual has hope for a well- deserved quality of life and happiness (including the support of the family and caregivers).

It has been apparent during my long years in the field, that access to quality services especially for adults with IDD, remains a challenge across the United States. I have been schooled in the long, sad history in the U.S. of how people with IDD have been devalued, marginalized, and segregated into institutions for life. It wasn’t really until the 1960s and 1970s that the horrible care of those with IDD was exposed to the general public; enough to help wake people up and begin to appreciate that those with IDD deserved the same rights as other citizens. The Olmstead decision in 1999 by the U.S. Supreme Court helped to further the push for deinstitutionalization across the US. It is apparent that deep-seated ignorance, cultural biases, and national priorities can still impact and how fast (and to what degree) change can happen within any society. That is true where it come to how those with IDD have been treated in the past, and certainly still very true to this day. Ukraine is a clear reminder of that.

The institutionalization of those with IDD across the world has been going on since at least the 1800s. The “normalization” of how this practice of care be done and supported by the government and by society has deep roots, often based on ignorance, stigma and bias against those with disabilities. Societies believed that

they were being just in their warehousing of those with IDD, who also were often placed with the mentally insane, homeless, criminal, and those deemed to be morally corrupt. Over years, societies began to segregate out these various types of individuals into their own facilities.

It was deemed that societies had created an appropriate place to care and house these individuals. Terminology was used to help subdivide them

into various categories “which would provide a clinical manner reference in their abilities and level of function. Terms such as moron, imbecile, and feebleminded were applied in this fashion. The term “mental retardation” was felt to be just another term used to define individuals, which also provided additional labeling and categorization and stigma.

My early views of those with IDD were from my work as a neurologist in several of New Jersey’s state-run institutions. My life experiences, and certainly my education and training in medical school, as well as neurology residency, did not provide a grounding or exposure to those with IDD, either socially, ethically or medically. I went into my work at the institution rather ignorant. My level of an “expert” was quickly tested as soon as I began my employment there.

People with IDD have a very high prevalence of neurologic complications, including epilepsy, movement disorders, spasticity—and challenging behaviors such those associated with autism and epilepsy, often beginning as young child, the often persisting throughout their lifetime. Many individuals may continue to experience seizures despite being offered various combinations of seizure medications, electric stimulation devices, dietary changes, and even some receiving surgery. The individuals that I was caring for have had lifelong disabilities associated with their neurologic complications. Most have received various degrees of care since they were very young, or even since birth. It became rapidly clear in my growth in the field of developmental medicine, that I was being exposed to an Ukraine has over 100,000 people with IDD in their institutions and orphanages. They have created a system in which babies and children are identified at a very young age as being uneducable, and therefore, the solution for them is to be taken care of by the state. extremely narrow view of life, and that institutional care was not the norm but rather a parochial way in which those with IDD were being cared for. Helping provide them with rights, freedom of choice, and equity became a driving force for me. This was important to me, not only as a person, but also as a neurologist in developmental care, including as president of the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry (AADMD). Living at home with families and receiving community-based supports are rights that all people, including those with IDD, deserve. When offered the opportunity to go to Ukraine and help support a just cause, I was eager to seize this opportunity, though may not have really appreciated it until it hit me on the head.

For over 30 years, Disability Rights International (DRI) and its Executive Director, Eric Rosenthal, have been aggressively and without pause fighting to promote the human rights and full participation in society of people with disabilities. DRI has committed to a worldwide campaign to draw attention to, and end, the pervasive and abusive practice of institutionalizing children with disabilities. DRI has been central in supporting and promoting international law which has led to the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Article 32 of the CRPD seeks to end international support for new institutions and segregated service systems.

So why Ukraine, and why now, while Ukraine is now fighting against an aggressive attack from Russia? The institutionalization of children with IDD has been ingrained in the Soviet bloc culture and has remained even when the Berlin wall came down and each of the various countries previously within the sphere of the Soviet Union influence became independent. DRI and other watchdog organizations have been going into these various countries for decades reporting on abuse and neglect, and fighting to end institutionalization and to push for family and community integration. DRI has been working in many of these countries, including Romania, Serbia, Moldova, Bulgaria, Ukraine, and others. A number of reports have been created that bolster the great need for reform and further documentation of abuse and neglect. Governmental bodies, international advocacy organizations and local IDD support

organizations have all be brought together to help fight and promote the human rights of those with IDD and to end the dread of institutionalization. Despite many years of these efforts,

Life in a crib Ukraine has remained extremely slow and backwards in their progress.

Ukraine has over 100,000 people with IDD in their institutions and orphanages. They have created a system in which babies and children are identified at a very young age as being uneducable, and therefore, the solution for them is to be taken care of by the state. Ukraine has not created family and community supports. They have not created an early intervention program to help with social or physical needs of individuals with IDD. They deem that their institutions are the best for them. No doubt their culture has greatly devalued people with IDD, and they have set a very low bar on the prospect that people with IDD can be helped. Ukraine had been discussing their own reforms for people with IDD, including the decisions on institutionalization, but had decided to stall and basically kick the timing and implementation of any reforms and family and community supports for another day. Then the war began. Ukraine has many institutions throughout the country. They house people of various ages, from babies, all the way up to adults. The levels of their disabilities vary. DRI has documented on many of their videos, pictures and reports that social and personal neglect is rampant, and that many of their needs for nutrition, physical stimulation, and therapies are not being met. Untreated spasticity, and hydrocephalus are just a few conditions which have been noted. The war with Russia has led to the displacement of many individuals who had been in institutions close to battle in the east of the country and moved to institutions in the west. DRI had recently gone into Ukraine in April 2022 alongside a BBC crew which further brought to light the terrible ongoing issues. DRI decided it was imperative to go right back into Ukraine to further expand upon their previous visit and to push even harder on shining a light on what was going on.

The thought that the timing for reform, planning and support for those now with IDD should wait until the war was over is impossible to imagine. I had these thoughts, and certainly these questions were mentioned to me as I was contemplating my own decision whether or not to go into Ukraine to support DRI.

I had a number of detailed conversations with Marisa Brown about DRI and her recent visit to Ukraine, plus a straightforward conservation with Eric Rosenthal about this effort, and about my role. We were going to enter Ukraine from the southwest through the city of Suceava, Romania. We were going to be supported by a wonderful Ukrainian advocate and guide, Halyna Kurlyo. We were going to remain very far away from where the battle was taking place far to the east.

My wife, family and neurology partners all supported my decision to go, so off I went on June 3, 2022.

The second part of this article about the journey will pick up upon my arrival in Ukraine in the city of Chernivtsi. Witnessing the institutions firsthand and its conditions, with signs of war were all around us. Meeting with local governmental leaders to discuss their thoughts and action plans, plus having an international news presence and how it impacted the story was all quite surreal.

Seth M. Keller, MD is a board-certified neurologist in private practice with Neurology Associates of South Jersey. He specializes in the evaluation and care of adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD) with neurologic complications. Dr. Keller is on the Executive Board of the Arc of Burlington County, as well as on the board for The Arc of New Jersey Mainstreaming Medical Care Board. Dr. Keller is the Past President of the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry (AADMD). He is the co-president of the National Task Group on Intellectual Disabilities and Dementia Practices (NTG).

Diagnostic Overshadowing:

By Emily Johnson, MD

The Pitfalls of Prejudicial Thinking

- Sir Heneage Ogilvie

Ikeep a list of my patients who have passed away. Currently, the names reside on a sticky note in my office – I keep promising myself to upgrade the display. I try to play a small part in keeping each of their memories alive. There’s one patient on the list whose death I continue to wonder about. In the months leading up to it, I saw him many times, knowing there was something wrong but not knowing what. He was non-speaking, so it was always hard to know what he was feeling, hard to know what direction to take a workup. He had a variety of abnormal labs, but there was no obvious pattern. I spoke with other doctors to get input and ideas of what the underlying diagnosis could be. I had assumed I had time to sort it all out. It crushed me when he passed, not only because I truly loved him as a patient, but also because I had to face the fact that I missed a diagnosis, that perhaps someone better or smarter might have figured it out. The family opted not to do an autopsy, so I will never know what I missed. A physician’s job is to diagnose, but inevitably, whether we want to admit it or not, we all miss from time to time.

There are countless reasons patients go undiagnosed or misdiagnosed, and we are fortunate when we have the opportunity to identify and learn from the experience. Upon first thought, most would probably assume that all missed diagnoses arise from knowledge-based errors, in which a clinician just does not know enough to identify the underlying diagnosis, as in the story described above. Knowledge-based errors are a clear issue and one that clinicians spend their careers working to avoid. Medical and dental school, residencies, and fellowships are all designed to help us avoid knowledge-based errors. Assuming the correct diagnosis is ultimately discovered, knowledge-based errors are also some of the easiest to identify and learn from. Unfortunately, they are far from the only types of errors that lead to missed diagnosis.

On the other end of the spectrum, missed diagnoses also arise from a variety of bias-based errors. In these cases, a clinician has the sufficient underlying knowledge to make the correct diagnosis but is unable to do so because of some underlying bias, which may be in relation to a group of people or simply due to the way in which information was presented and an inability to get themselves out of a certain train of thought. As these biases are, by nature, not something the clinician is consciously aware of, they are much more difficult to identify and learn from. Undoubtedly, we have all made these errors, many of which we never even realize. These are also errors that likely disproportionately affect marginalized patients.

Not long ago, a patient of mine with Down syndrome came to my office with staff from his group home to address “sundowning.” He had carried a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease for a few years at the time, originally diagnosed by an outside provider. When his group home staff had complained to his psychiatrist that he was falling asleep at day program, typically in the later afternoon and not sleeping through the night, the psychiatrist attributed it to the Alzheimer’s disease and recommended that he get a referral to a neurologist to discuss treatment options. I conveniently saw this patient in the later afternoon, when the symptoms typically arose. I walked in the room, and immediately knew that a sleep study, rather than a neurology referral, was the better initial course of action. He was slumped over in his wheelchair, sound asleep. I had seen this many times before, in particular with patients with Down syndrome. As I suspected, he in fact had severe obstructive sleep apnea, and his symptoms ultimately improved with BiPAP therapy.

Just last week, I met a new patient with autism who came in with recurrent episodes of anorexia. He would refuse to eat or drink, resulting in multiple hospitalizations for dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities. He was notably underweight. I assumed a significant workup had been done, but his parents told me that they had a CT in the ER and were later told no one could find a cause and it was probably his autism. As this was a new problem, and he has had autism his whole life, that assessment was absurd to me. It is obvious that the true underlying diagnosis has been notably delayed.

Diagnostic overshadowing is a common diagnostic error that results from a clinician’s assumption that a given sign or symptom is a direct result of a previously identified diagnosis, when it is in fact due to a separate process. In the case described above, the sleep

Concrete Recommendations for Clinicians to Avoid Diagnostic Overshadowing

Reconsider your assessment or diagnosis if the presenting issue is new and the condition you are attributing it to is old.

Always consider behavior to be a form of communication and commit to figuring out what it is communicating.

Educate or re-educate yourself on disabilities, syndromes, and mental health diagnoses as well as commonly (and uncommonly) associated diagnoses.

Consult with colleagues or specialists on any case you feel uncertain about. Make it an opportunity for everyone to learn.

When working with patients from any marginalized background, make it a habit to second guess yourself and ask what you may be missing or what information may change your assessment.Listen to family members, caregivers, and others close to the individual. They likely have an exceptional sense when something isn’t right.

Make our practices accessible from a physical and behavioral perspective for all patients.

ADVOCACY RECOMMENDATIONS

Educate leadership and colleagues on what is mandated by the ADA.

Identify inaccessible clinics, exam rooms, etc., within your own institution and advocate for a concrete plan to fix issues within your organization.

Offer yourself as a resource to provide education on treating marginalized populations within your own organization.

Advocate for education regarding diagnostic overshadowing in health professional schools and residency curriculums.

Advocate that all health professional students have required concrete didactic and hands on experience with people with all types of disabilities and other marginalized populations. and behavior changes were incorrectly attributed to a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease when they in fact were due to sleep apnea. Individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities are at particularly high risk for errors due to diagnostic overshadowing, as new symptoms or concerns are all too easily attributed to a patient’s underlying disability, rather than a potential new diagnosis. It is easy to imagine how this would exacerbate the health disparities that this population already faces.

In June 2022, the Joint Commission released a Sentinel Event Alert regarding diagnostic overshadowing in populations facing healthcare disparities. The perils of Diagnostic Overshadowing were brought to the attention of the Joint Commission as a result of a robust and ongoing collaboration with the National Council on Disability (NCD).

At first glance, a newsletter article may seem relatively insignificant, although the potential impact of this alert should not be overlooked. The Joint Commission is a critical body in healthcare regulation and improving patient safety in hospital systems across the United States. They create policies and standards regarding patient safety and formally evaluate hospital systems. It is unprecedented that they would call out a specific issue relating to the healthcare of patients with IDD and other health disparities such as diagnostic overshadowing. It is clearly a step in the right direction, and it is a hopeful sign that policies and procedures could be implemented healthcare system-wide to improve the safety of care provided to individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

As clinicians, patients, and family members, we have an opportunity to continue to advocate for policies and standards that further improve safety

for patients with IDD, including as it relates to diagnostic overshadowing. The Joint Commission advocates for improved training, improved listening, improved interviewing techniques, improved data collection, using intersectional frameworks in patient care, and improving compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Given that the ADA was signed over 30 years ago, and there are still countless hospitals and healthcare practices not meeting accessibility requirements, it is clear that legislation and alerts such as the aforementioned alert are not enough.

As professionals in IDD care, we have the obligation to run with the framework outlined by the Joint Commission

and make it an implemented reality. We must create actionable steps to reduce diagnostic overshadowing as outlined in boxes one and two. We must advocate within our own institutions, but also within the entire healthcare system. We have the opportunity to ensure that these recommendations are made to have a true impact on the quality of There are countless reasons patients go undiagnosed or misdiag“ nosed, and we are fortunate when we have the opportunity to identify care provided to individuals with intellectual disabilities. and learn from the experience. Emily Johnson, MD is medical director of a primary care clinic for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities in Colorado Springs, CO and VP Policy and Advocacy of the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry. She is also lucky to have both a brother and son who have Down syndrome.

A Passion for Supporting

the IDD Community

and Proud Supporter of HELEN: The Journal of Human Exceptionality

Almost 30 years ago, Eunice Kennedy Shriver asked Dr. Steve Perlman to create a health program for the Special Olympics. “Healthy Athletes” is now the largest public health program in the world for children and adults with Intellectual/Developmental Disabilities.

HELEN: The Journal of Human Exceptionality is the next step to helping provide healthcare professionals, caregivers, families, and advocates with resources and education to better support this under-served, marginalized and invisible population.

Steve Perlman, DDS, MScD, DHL (Hon.) has extensive experience through his private practice and his role as Clinical Professor, Boston University School of Dental Medicine; has an Academic Appointment at the

University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine; is Co-founder and Past President of the AADMD.

SleepApnea

and DownSyndrome

By Hampus Hillerstrom

Sleep apnea is a potentially serious disorder that affects more than 50% of children with Down syndrome and more than 80% of adults with Down syndrome (compared to an estimate of 5-10% in the general population). Untreated sleep apnea can affect behavior and cardiovascular health, impact cognitive development, and, in some cases, accelerate the onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

WHAT IS SLEEP APNEA?

Sleep apnea occurs when air is not passed normally in and out of the lungs while sleeping. Experts define sleep apnea as Experts define sleep apnea as a decrease in breathing (hypopnea) or complete cessation of breathing (apnea), resulting in a decreased oxygen in the blood and/or an arousal from sleep. (The International Classification of Sleep Disorder-3). The pauses in breathing usually last 10 to 20 seconds but can last as long as 120 seconds.

TYPES OF SLEEP APNEA

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA): The airway closes when the person breathes in. Respiratory effort continues but the obstruction prevents movement of air into and out of the lungs. This is the type of sleep apnea most prevalent in people with Down syndrome. Central sleep apnea: This is a less common type of sleep apnea. In this case, the brain fails to transmit the appropriate signals to the respiratory muscles, resulting in the muscles not being able to circulate oxygen in and out of the lungs. This type of sleep apnea is common among patients who have suffered from heart failure, stroke, or brain injury.

Complex sleep apnea: This type of sleep apnea is diagnosed often during treatment of obstructive sleep apnea, after the obstruction has been treated and central apneas are observed.

RISK FACTORS FOR SLEEP APNEA

The most common form of sleep apnea is obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Risk factors include: • A narrowed airway from factors including enlargement of the soft palate, local fat deposition, or an enlarged tongue • Obesity: this is a major risk factor; however, many

obese people do not have sleep apnea, and some people with sleep apnea are not obese • Large neck circumference • Being male • Being older • Family history • Use of alcohol or sedatives and smoking (generally uncommon among people with Down syndrome) • Chronic inflammation of the nasal passages • Enlarged lymph tissue such as tonsils and adenoids • OSA is significantly more common in people with Down syndrome

WHY IS OSA COMMON IN PEOPLE WITH DOWN SYNDROME? Individuals with Down syndrome have a higher predisposition to obstructive sleep apnea due to certain anatomical and physiological characteristics of the airways such as a relatively small midfacial region with a relatively large tongue, which contribute to the compromised airway.

Other conditions common in people with Down syndrome are chronic inflammation of the nasal passages, enlarged lymph tissue (including the tonsils and adenoids), and obesity, which are all added risk factors for sleep apnea.

The general decline in muscle tone in individuals with Down syndrome is another important contributing factor. Open airways are dependent on muscle tone, in this case the pharynx.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of sleep apnea begins with recognition of the symptoms. A physician will perform a physical exam that often reveals obesity and excessive soft tissue in the mouth, pharynx, and neck. In some cases, with advanced disease, the right side of the heart is weakened and findings of failure of that part of the heart may be seen. The laboratory tests are usually normal except low oxygen and high carbon dioxide may be found. (Advocate Medical Group)

An overnight sleep study is needed to definitively diagnose sleep apnea. This study entails recording eye movements, muscle tone, electroencephalogram (EEG) to measure brain waves, and electrocardiogram (EKG) to measure the electrical activity of the heart. The test also records respiratory movements, nasal and oral air movement, and oxygenation of the blood. Experts from the American Pediatrics Association recommend that all children with Down syndrome have a sleep study conducted by the time they are four years old.

STANDARD TREATMENT OPTIONS If obstructive sleep apnea is diagnosed, there are several standard options for treatment: • For patients who are obese, doctors recommend weight loss. Dr. Allen Wong • Sometimes, sleep apnea worsens when the patient sleeps on their back. Therefore, encouraging the person to sleep on their side or on their abdomen can be helpful. Doctors recommend placing a sock on the back of the pajama top and placing a tennis ball inside the sock. This will keep the person from sleeping on their back. • Adenotonsillectomy: this is the first-line approach for most children. However, it is unlikely to resolve obstructive sleep apnea in children with Down syndrome since 65 to 73% of patients have some OSA after adenotonsillectomy. • Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP): In this treatment, pressurized air is delivered through a mask and hose, helping the person’s airway stay open through sleep. Although highly effective, it is often difficult for people to stick with the treatment because of the discomfort of wearing the mask. For example, only 46% of children with Down syndrome adhere to CPAP treatment.

ALTERNATIVE/EMERGING APPROACHES

As sleep apnea research advances, doctors and specialists are beginning to see results in some non-traditional treatments: • Weight loss • Dental approaches, such as palate expansion and Mandibular advancement device • Myofunctional therapy (speech therapy) • Anti-inflammatory medications, as small improvements seen with Singulair® or intranasal steroid treatments • Hypoglossal Nerve Stimulation: This treatment involves a surgically implanted device that is FDA approved for adults 18 years of age and older with moderate or severe sleep apnea, including adults with Down syndrome.

The device has been shown to be effective, with an average 68% reduction over 12 months. The device works to stimulate the tongue to open the airway at night. To learn more about sleep apnea and other sleep disorders go to www.LuMindIDSC.org/sleep and sign up to myDSC, a free library of Down syndrome resources at www.myDSC.org.

OPPORTUNITIES

Down Syndrome and Sleep Apnea

Mosaic Sleep Apnea Study for Sleep Apnea in Children with Down Syndrome

This study from the University of Arizona is seeking to investigate the use a combination of atomoxetine (a medication approved by the FDA in children for the treatment of ADHD) and oxybutynin (a medication approved by the FDA in children for overactive bladder).

The company developing this approach is Apnimed, Inc. These medications, which have been shown to treat obstructive sleep apnea in a small study of adults without Down syndrome, are thought to treat obstructive sleep apnea by increasing airway muscle strength, which is known to be lower in children with Down syndrome.

They are actively recruiting participants for the clinical trial ages 6-17 with Down syndrome. For more information, contact Silvia Lopez at slopez1@arizona.edu.

LuMind IDSC is working with principal investigator Dr. Chris Hartnick, of Massachusetts Eye & Ear, to accelerate research of this approach for children.

If you are interested in learning more about this study, and whether your child would be an appropriate candidate, please contact the research team at Massachusetts Eye and Ear by emailing Christopher_Hartnick@meei. harvard.edu. Hampus Hillerstrom is President/ CEO of LuMind IDSC Foundation. Previously, he co-founded and served in executive roles at biotech company Proclara Biosciences. Hampus also worked at venture capital firm HealthCap, pharma company AstraZeneca, and investment bank Lazard. Hampus holds a master’s degree in economics from University of St. Gallen, MBA from Harvard Business School, and MSc in Health Sciences and Technology from MIT/Harvard. Hampus lives in the Boston area with his wife and children. Their oldest son, Oskar, has Down syndrome.

The LuMind IDSC Foundation (LuMind IDSC) envisions a world where every person with Down syndrome thrives with improved health, independence, and opportunities to reach their fullest potential. LuMind IDSC accelerates research to increase availability of therapeutic, diagnostic, and medical care options and provides resources, connections, and support to a vibrant community of individuals with Down syndrome and their families. Visit www.LuMindIDSC.org.

This article is included in the upcoming monograph “Sleep and Sleep Disorders in People with Disabilities” published by HELEN: The Journal of Human Exceptionality.

RESOURCES

Sleep Apnea by Paula Cho, Advocate Medical Group

Preventing Sleep Apnea by Dr. Brian Chicoine, Medical Director, Adult Down Syndrome Center Advocate Medical Group, 2020

Sleep disordered breathing and ventilatory support in children with Down syndrome by Trucco, et.al. 2018

Relationship between obstructive sleep apnea cardiac complications and sleepiness in children with Down syndrome Konstantinopoulou, et.al. 2016

Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Young Infants with Down Syndrome Evaluated in a Down Syndrome Specialty Clinic Goffinski, Stanley, et. al. 2015

Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults with Down Syndrome, Trois et al. 2009

TIPS

for Good Sleep Habits at Home

Regular Sleep Schedule: Maintain a consistent sleep pattern, getting up at the same time every day.

Relaxing Bedtime Routine:

Spend time before bed relaxing: read a book, have a shower or bath.

Eat Well: Try to eat a balanced, healthy diet. Avoid heavy, fatty, fried, or spicy food late in the evening if you get indigestion, Bananas, yogurt or healthy cereal are good bedtime snacks.

Good Sleep Environment: Keep your bedroom aired, cool and comfortable with a quality mattress and bedding. Block Out Noise and Light: Make sure the bedroom is dark and quiet or use white noise, a fan or music to mask external noise.

Only Sleep and Intimacy: Avoid watching TV or using other devices, such as cell phones, in bed.

Exercise and Daylight: Try to do regular exercise, but not too intense before bedtime.

Spend time outside in the daytime. Even a short walk during the day can improve sleep.

Avoid Stimulants: Don’t drink coffee, sugary or energy drinks in the evening.

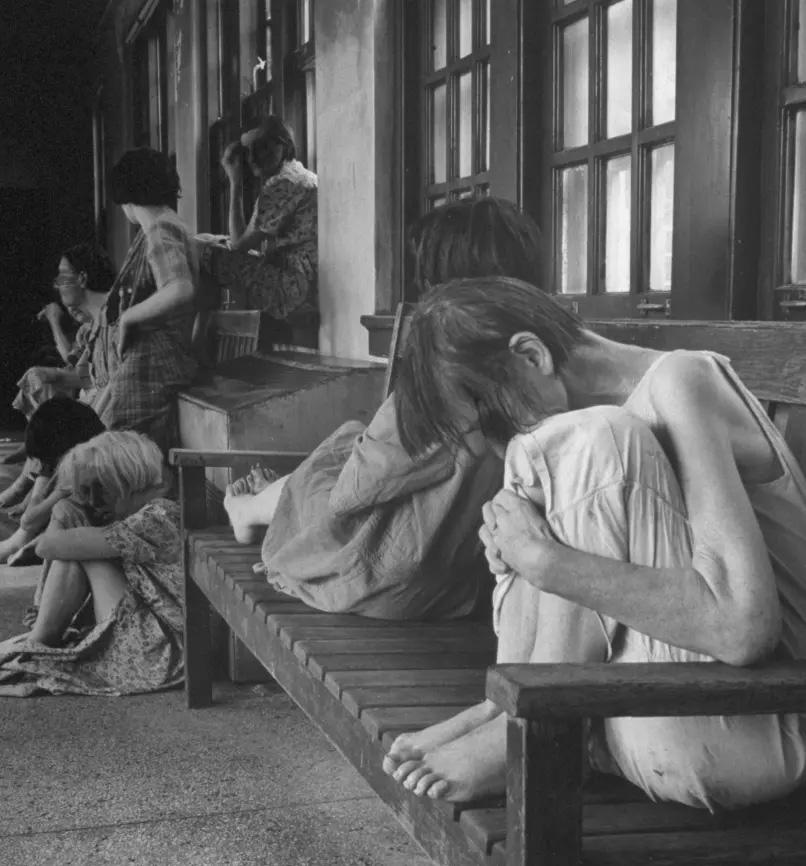

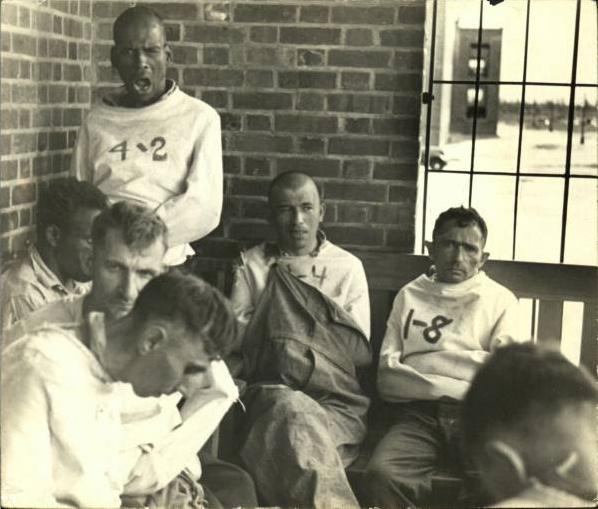

Patients in Ohio’s Cleveland State Mental Hospital - 1946 Photo: Mary Delaney Cooke

Boy with leprosy lesions

Say Cheese:

A Brief History of Medical Photography

How medical photography dehumanized the individuals it was designed to benefit

By Rick Rader, MD, FAAIDD, FAADM

Mental Institution #21, East Louisiana State Mental Hospital - 1963 Photo: Richard Avedon

Readers of HELEN: The Journal of Human Exceptionality will probably be familiar with celebrated photographer Rick Guidotti and his program Positive Exposure. Rick has transformed both medical photography and medical education by his sensitive, realistic and artistic photographic images of real people with real conditions. For 25 years, Positive Exposure has collaborated globally with nonprofit organizations, hospitals, medical schools, educational institutions and advocacy groups to promote a more equitable and compassionate world where individuals and communities at risk of stigma and exclusion are understood, embraced and celebrated.

Unfortunately, medical photography has not always served to portray individuals with disabilities as valued, humanistic and personable.

Anyone who has ever had their photograph taken has heard the expression, “Smile, say CHEESE.” The use of the phrase “Say cheese” first appeared around the 1940’s and has (seemingly) legitimate physiological evidence to elicit a smile. Brooke Nelson in the blog “Taking Pictures?” suggests “The ch sound causes you to clench your teeth, and the long ee sound parts your lips, making a facial expression that resembles a grin.”

One thing is certain; medical photographers never encouraged or promoted patients to smile or “say cheese.” In fact, the closest thing to a smile on a patient’s medical photograph was when they demonstrated a wide shot of some oral pathology.

So, while “Say Cheese” is an invitation to smile, the reality is that when referring to historical medical photograph the reference to “Cheese” might be an acronym for (C.H.E.E.S.E.) Clinical, Horrific, Exclusionary, Exasperating, Specimens, and Exaggerations. And if you threw in a “D” for Cheese “D” it results in Dehumanizing.

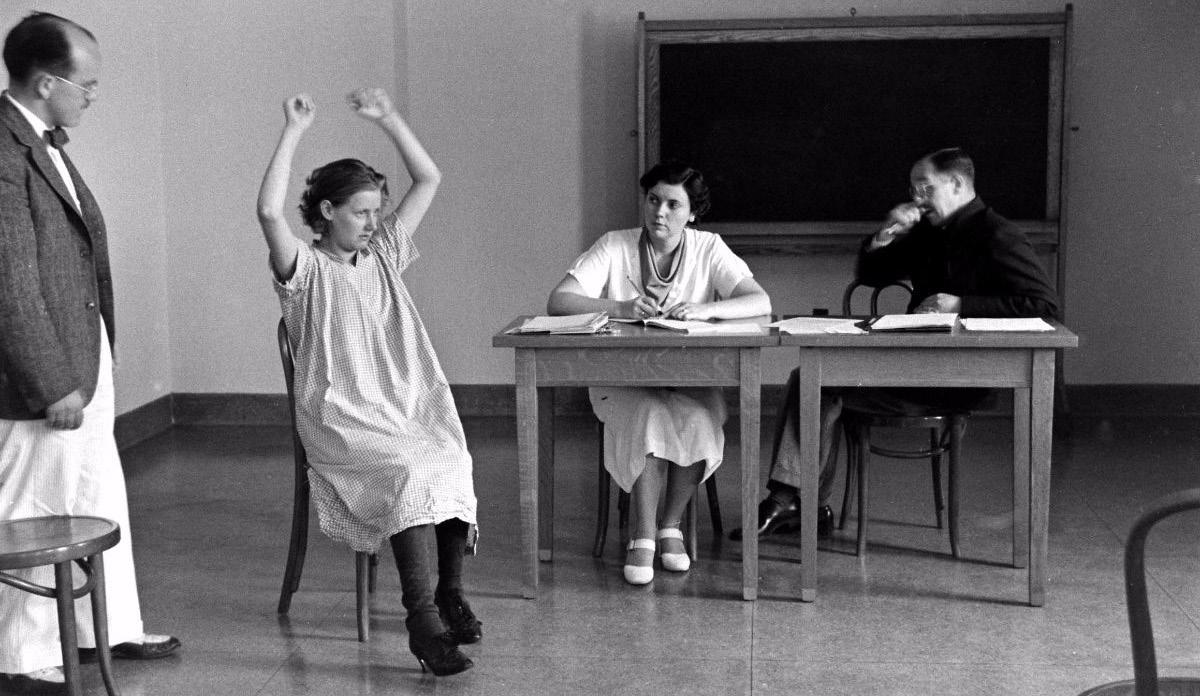

During the 19th century, physicians used photographs as consultation tools in obtaining second opinions for challenging cases. They would also use them as “before” and “after” treatments and use them for personal advertising endorsements to promote their practices. These early photographs employed the “daguerreotype process” which was developed by Louise Daguerre, an early pioneer of the photographic process. The first use of photography in medicine was in 1839 by the physician Alfred Donne, and is credited with the first medical textbook using photographs. Most of the photographs were micrographs from microscopes of platelets, leukemia and Trichomonas vaginalis cells. The earliest medical portrait of a patient was in 1840; it depicted a woman with a large goiter.

Photography was also used in psychiatry to capture the facial features of “the insane” for diagnostic purposes. Photographs of patients were also used to show the patients the positive results of ongoing therapies.

Virtually every medical specialty

has employed photographs of patients, specimens, procedures and outcomes. Virtually every war since the American Civil War has provided an abundant supply of dramatic subjects of horrific war wounds, trauma and “make-shift” treatment protocols. One would think they would serve as much for rationale diplomatic solutions of conflict in addition to clinical education.

While this article showcases medical photography, we would be remiss if we did not mention the contributions of medical illustrators and artists.

Early medical textbooks used drawings and illustrations to depict clinical conditions, most notably the ones used to guide medical students in dissecting bodies in introductory anatomy classes. The most applauded anatomical illustrator was the 16th century Belgium artist Andreus Vesalius (text called “On the Fabric of the Human Body.”) Of note is the American physician-illustrator Dr. Frank Netter (1906-1991); his remarkably illustrated books helped to educate generations of physicians, and are still used today.

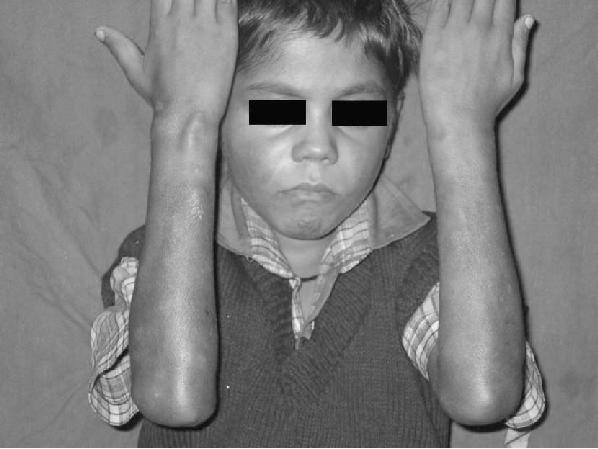

The typical patient photograph employed several standardized features. The patients were naked and had their facial features (eyes and mouths) covered up with black stripes to conceal their identity. They were often depicted alongside measurement references to provide approximate heights. The subjects were typically in the “standard anatomical position,” which included a human standing, looking forward, feet together and pointing forward, with none of the long bones crossed from the viewer’s perspective. They often had their arms extended from their sides with their palms facing forward. They were expressionless and appeared as if they were specimens on a microscope slide or in a petri dish.

While the “patient exhibit photographs” did not intend to dehumanize or depersonalize them, the fashion in which they were displayed reflected the way clinical case studies were employed. The emphasis was on the clinical features of the disease, illness or disorder. The single dimension of the photo did not allow for a “patient narrative.” It was intended to emphasize and capture the visual novelty of the condition.

During World War II, the Air Force widely distributed cards to civilians, featuring black and white images of popular enemy aircraft, each one a unique design and configuration. It was intended for civilians to report any enemy aircraft sightings to the defense forces. Of course it did not provide any means to identify the pilots or crew; they were simply created to signify one plane from the other. The same could be said of the patient

Typical medical photo of an individual with Marfan syndrome

- Ansel Adams

Psychiatric hospital evaluation

photos…the emphasis was not on “who” the person was, but “what” condition the person had. The photographs also reflected how medical education was conducted; it often was cold and calculated and did not emphasize empathy and compassion.

And while hidden camera photos are considered more like photographic exposes of the inhumane conditions and treatments in state institutions for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities than medical education photographs, they can be credited with the closure of many state facilities. Most notable are the ones taken inside the Willowbrook School and in the book, Christmas in Purgatory (A Photographic Essay on Mental Retardation) by Burton Blatt and Fred Kaplan (1974).

Photography, like medicine itself, has come a long way; and while photographs are no substitute for actual patient contact, they certainly have a role in helping students and clinicians recognize both subtle and gross features of specific conditions. Luckily, the next generation of physicians will have access to the photos of Rick Guidotti, who has managed to incorporate the human side of human subjects and remove them from both the microscope slide and the petri dish.

In terms of medical photographs demonstrating how certain conditions impact on the lives of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, I conclude with an observation from famed American portrait photographer Annie Leibovitz, “A thing that you see in my pictures is that I was not afraid to fall in love with these people.”

Guaranteed, you will be seeing more of these photos in the pages of HELEN: The Journal of Human Exceptionality.

A patient in a restraining chair at the West Riding Lunatic Asylum in Wakefield, Yorkshire, England - 1869 Photo: Wellcome Library, London

Health Equity

FOR PEOPLE WITH IDD

By David A. Ervin, BSC, MA, FAAIDD

In early 2014, over a bottle of Malbec and talk of health and healthcare for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) in the dining room of my house at the time, my mentor, friend and colleague, Dr Leslie Rubin, and I, committed at that point for years to health equity for people with IDD. We dreamed of bringing together for some sort of planning event for all the major advocacy organizations, healthcare community provider associations, and any others that might be interested in combining efforts to push for health equity for people with IDD. We envisioned all these organizations and all of their leadership coming together to establish an agenda and make commitments to addressing and resolving rampant health disparities experienced by people with IDD. Surely, we believed, if the major organizations dedicated to people with IDD were to come together in common purpose, real, substantive and lasting work could be done to achieve health equity.

The next day, I started calling around to the organizations with which I spent the most time to see if we could tempt them into such a coming together. I’m fairly certain it was Maggie Nygren, the immensely talented CEO of the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD), who put me in contact with a person of whom I’d never heard who had recently become president of an organization of which I’d never heard. That newly-minted president was Dr Matt Holder, and the organization he would lead was the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry (AADMD). Matt and I would end up working very closely and collaboratively over the ensuing months, and we were ultimately joined by an unprecedented array of organizations, literally from around the world, for the Global Summit on Innovations in Health and IDD in Los Angeles in Summer 2015.

Through that work, I came to know Matt well, but I also met the driving forces of the AADMD. People whose names and reputations preceded them, but with whom I’d never meaningfully worked—absolute legends in health advocacy for people with IDD at a time when there weren’t many, all committed to health equity for people with IDD.

Soon, I would begin working more consistently with AADMD. As I did so, I got to know more and more intimately the organization’s raison

d’etre. The more I came to know and understand, the more I wanted deeper involvement. This was “my tribe”, and I searched for ways to work with and become part of their work. I should note that I’m not a clinician. I used to be, but those days AADMD members are advocating for change at levels ranging from the local “ are long lost to my passions for system design and development, for practical and translational research, for geeky policy work, and for community supports and advocacy. Someone once told me I’m a ‘pracademic,’ an amalgam of a practitioner and academic, to the federal to the galactic! which fits me perfectly! The AADMD’s mission is “to provide a forum for healthcare professionals who provide clinical care to people with IDD and improve the quality of healthcare for individuals with IDD.” I love this, of course, but as a pracademic, I’m still not a clinician and certainly not a healthcare professional. So, I dutifully and religiously paid my Associate Member dues, attended conferences, made presentations, and contributed wherever and however I could to further the work of the AADMD. Through the eight-plus years that have passed since my first chat with Matt, I’ve worked with the Board of the AADMD on strategic planning and positioning, on developing tools

and policy statements that deepen the impact and lengthen the reach of the organization. It has been and remains work I cherish. It never occurred to me to give a second thought to my Associate Member status.

This summer, at their historic One Voice Conference in Orlando, Florida, I became the first-ever Honorary Member of AADMD. Unbeknownst to me, the Board of Directors unanimously bestowed this honor on me in recognition of my dedication to and work with and for the AADMD. It’s an astonishing honor. As I told outgoing President, Allen Wong, the purpose and work of AADMD is something to which I have been and will remain, so long as they’ll have me, utterly committed.

AADMD is the leading health advocacy, health equity organization at the nexus of healthcare and IDD. They proudly and accurately boast that since 2002, they have led the effort to improve the quality of healthcare for people with IDD. Per Past President, Dr Steve Sulkes, “AADMD members are training future healthcare leaders, structuring healthcare systems that more effectively respond to patients’ needs, developing evidence-based health guidelines, and advocating for change at levels ranging from the local to the federal to the galactic!”

I’ve known Allen and Steve and Matt and all of the AADMD leadership for eight magnificent years, and I have watched in wonder as they build an ever-expanding tent for ALL of us committed to health equity for people with IDD. Even a non-clinician like me. As the inaugural Honorary Member in this 20-year-old organization, I happily urge you to join our cause. There is so much work still to do, so much ground still to cover, so many miles still to travel.

As we grow our leadership in the health equity space, and as we seek to grow our impact, we welcome you to our work. It will take all of us. Professional Members, Associate Members, health science students, even International Members. And, in my case, the first-ever Honorary member.

David A. Ervin, BSC, MA, FAAIDD, is CEO of Jewish Foundation for Group Homes, a nonprofit supporting people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) in Maryland and Virginia. With more than 30 years in the field, Mr. Ervin has extensive professional experience working in and/or consulting to organizations and governments in the U.S. and abroad. He is a published author and speaks internationally on health, wellness and healthcare for people with IDD and other areas of expertise.

Every person has the right to live well. ™

Sevita is proud to be a Founding Sponsor of the AADMD’s New Publication, Helen: The Journal of Human Exceptionality

SevitaHealth.com

I Went All

By Edward Barbanell and Got Myself Some Clout

My name is Edward Barbanell. I was born with Down syndrome. To me, that diagnosis does not control my life. It is a meaningless word. I now know that I could succeed at whatever I try to do. I don’t and won’t accept the limitations people place on me. Never have, never will!

I don’t know what it was, but I’ve always had something in me that allowed me to forget about what everyone else was doing, to forget about what was normal, to forget about what was expected of me and my disability. My whole life I’ve been sliding headfirst into new situations and new opportunities. I love challenging people’s expectations of me.

Being born with a disability means I inherited unique abilities and challenges - challenges that I have worked hard to endure and overcome with the help of my loving family, friends and programs such as Special Olympics. As we know, inheriting these challenges is something that I could never control. I’d be lying to you, and we’d all be lying to ourselves if we didn’t admit that being born with a disability can be frustrating at times. It’s an incredible test of our resolve to overcome adversity. It tests us, it tests our families, our communities and our political leaders. I can accept the disability that I’ve inherited because I have learned what it takes to overcome the challenges that come with it.

I have what it takes to lead a joyous and fulfilled life!

I have the love and support of my family and friends!

I have the desire to get as much out of life as anyone else!

Acting

My interest in acting came about when my mother’s friend, a part-time actor, was practicing ShakespearBeing born with a disability means I inherited unique abilities and “ ean monologues. I was fascinated and asked if he could practice some speeches with me. I learned the Romeo and Juliet monologue and enjoyed rehearsing it in challenges - challenges that I have my home-made Shakeworked hard to endure and overspearean costume. In 2000, there was an come with the help of my loving acting competition for family, friends and programs such youths with disabilities called “The Rising Star.” as Special Olympics. I eagerly entered and performed my monologue. To my great delight I won first prize for my age division, and a check for one hundred dollars. I felt truly special as I had interacted with the audience and realized that I could succeed if I believed in myself. A year later, my mother read an article describing the Ricardo Montalban acting competition for actors

Photo courtesy: Special Olympics

with disabilities, which was going to be held in Los Angeles. I was very eager and excited to enter the competition. My mother, my aunt and I flew out to California. I was surrounded by seasoned actors with physical and intellectual disabilities. I found out that everyone had come with an acting partner. Neither my mother nor my aunt felt that they could be my acting partner! I desperately wanted to compete, and performed my Romeo monologue. The judges applauded my performance, introduced me to an agent who represented actors with disabilities, and awarded me the second place scholarship prize!

I was ecstatic when, several months later, I was cast in the role of Billy, Johnny Knoxville’s roommate, in the movie “The Ringer” produced by the Farrelly Brothers. The movie taught people about awareness and inclusion. The movie humanized people with intellectual disabilities and showed their capabilities, talents and skills. Tim Shriver, the CEO of Special Olympics, spent a great deal of time on the set, making sure that it was appropriate. I even ad-libbed lines, such as “Medicare, Medicaid, or Aflac.” The Farrelly Brothers loved the line and it was a humorous addition to the movie. One day, when we were driving to the set, I started to recite my Romeo. The Farrelly Brothers had been having a problem with the final scene of the movie and had not gotten approval to use the lines from a familiar sitcom. After hearing my monologue, Peter Farrelly decided, instead, to end the movie with the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet. In true Hollywood fashion, Shakespearean costumes and sets were sent to our Austin location. Ricky Blitt, the writer, rewrote the ending; and the rest is history! After the movie premiered, people wanted to meet me, shake my hand and ask for my autograph. Instead of staring at me because of my disability, they were staring at me because they recognized me, and wanted to talk to me “the Hollywood Star.” From 2006 -2015 I was honored to be invited to serve as a Board member for Special Olympics International. I was privileged to travel and speak at Special Olympic games in Iowa, Alaska, New Jersey, New York, Washington, D.C., Nebraska, Wyoming, China, Morocco, Greece, and Panama. In Boise, Idaho, Johnny Knoxville and I spoke about looking at ways to promote inclusion and pride for people with different abilities. We spoke about how we hoped that The Ringer would knock down stereotypes of persons with disabilities, and change attitudes all in good taste.

Helping End the Use of the “R” Word

In 2009, I was instrumental in starting a campaign to end the use of the “R” word. I spoke Andy and The Orphans cast in Boca Raton, FL. Photo courtesy: Amy Pasquantonio

about the “dignity revolution” which would change negative attitudes into positive attitudes. I promoted the concept of unified sports, which brought persons with disabilities together with athletes without disabilities. We must also provide support and guidance through education, healthy athlete screening, and sports training.

The following is a rap I wrote, with my mother’s help, about “Ending the R word”: As leaders we must all find a way to teach people to stand up and care, And I propose we do that by ending the use of a word that’s most unfair. Often you’ll hear someone say “retarded” without blinking an eye, Unaware of the hurt they cause when they let that word carelessly fly. We have the same needs as all of you, Love, respect, and camaraderie too. We are sensitive, caring and very aware, Don’t use the R word and please don’t stare. As leaders we can change attitudes, And use of the R word is definitely rude. We have to make society conscious about that word’s hurtful effect, And get them on board to empathize and reject. The Farrelly Bros. took a big chance When they cast me in The Ringer and let me do the steam room dance! I went all Hollywood and got myself some clout, Which comes in handy when you have a message to shout. We must erase the stigma when people say retarded, We hate that word, it needs to be discarded. They banned the word retarded when they passed Rosa’s law, I stood next to President Obama and helped him correct that legislative flaw.

We’re on our way, but our journey “has just begun, I need your help, COME ON IT’LL BE FUN!

Broadway Dream Fulfilled

Everyone repeated the R pledge: to support the elimination of the derogatory use of the R-word from everyday speech and promote acceptance, inclusion and respect for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. This event is celebrated annually on March 31st.

I have been blessed to have appeared in TV shows such as Comedy Central, Workaholics, Fantasy picpFactory, Loudermilk, Jackass 3D and Ridiculousness. My greatest experience, however, was when I met a young playwright, Lindsey Ferrentino, who had written a play called Amy and the Orphans, about a female with Down syndrome. She was interested in having me portray the lead, as Andy, a male with Down syndrome, in matinee performances. The play was going to be performed at the Roundabout Theatre in New York City for four months. I met with Lindsey one afternoon, and I told her about my various acting experiences. She listened and taped my monologues as Puck in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” “Henry V,” and Romeo. She was excited and impressed with my speeches and told me that she was signing me up for the Andy and the

Orphans. My Broadway dream had been fulfilled. I moved up to New York for five months and enjoyed acting in every one of my performances. I never missed a show! I kept singing the Frank Sinatra reprise from “New York, New York” - “If I can make it there, I’ll make it anywhere!” That was the greatest accomplishment for an actor with Down syndrome! The play was very successful and it made the public aware that they should not put limitations on people with disabilities. As an added bonus, a producer in Florida bought the rights to the play and I performed Andy and the Orphans for another six weeks. The performances were sold out! Although my most well known job is acting, everyone is aware that actors need employment between gigs. I have been working in the food industry for the past 20 years. I enjoy interacting with people and being there to serve them. I have always advocated for employers to hire more people with disabilities.

Conquering Sports

Special Olympic sports The play was very successful has been another fulfilling part of my life. I participate and it made the public aware in bowling and basketball, that they should not put and I especially love tennis. We are taught skills, particlimitations on people with disabilities. ipate in competitions, enjoy a sense of camaraderie and learn sportsmanship. This has always provided me with a sense of pride and accomplishment. Special Olympics offers a Healthy Athletes screening program directed by Dr. Steve Perlman. Doctors with various specialties (dentistry, ophthalmology, podiatry, hearing) volunteer to examine the athletes and make assessments and recommendations for follow-up care. This aspect of Special Olympics has been a life-saving experience for many special needs athletes.

Edward as Romeo

I am very grateful to all those volunteer specialists who are part of this team.

I am currently serving as a Global Ambassador for Special Olympics; as a spokesperson, advocate, actor, and athlete. We are united by a vision to make the world a better place for people with different abilities by inclusion in all aspects of the work force, on the playing field and in life. As I tell the athletes:

BELIEVE IN YOURSELF!

NEVER GIVE UP!

REACH FOR THE STARS!

SAVE THE DATE!

TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 6 – WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 7, 2022

Achieving Equitable Oral Health for Those with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: A Promise, A Pledge, A Plan

Hosted by the University of the Pacific, Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry San Francisco, CA

Join us for the Santa Fe Group’s Fall Program, a two-day gathering that celebrates the 25th anniversary of the Santa Fe Group and honors co-founder Dr. Arthur A. Dugoni. • Hear from nationally known experts in the field of oral health and advocacy • Build understanding of healthcare disparities from a medical perspective, implicit bias in healthcare, the basics of developmental disabilities and more • Engage in breakout sessions to discuss issues of inclusion, health concerns and other topics • Participate in live simulations of patient experiences with selfadvocates and parents • Discuss overcoming barriers to care, including physical, financial, insurance,attitudes, training and access • Learn about communication, etiquette and empathy; transitioning the patient for a lifetime of health and building the oral health team of the future to care for people with IDD

AND MUCH MORE TO BE ANNOUNCED!

Follow Edward on Socials!

Edward Barbanell

@edbarbanell Edward Barbanell

REGISTRATION OPENS SOON!

FOR MORE INFORMATION CONTACT ALLEN.WONG@AADMD.ORG. WE HOPE TO SEE YOU IN SEPTEMBER!

santafegroup.org

*Breakfast, luncheon, and refreshments will be served on both days

The Gathering of the Big Three

at the AADMD’s Historic One Voice for Inclusive Health Conference

By Rick Rader, MD FAAIDD, FAADM Photos by Karen Tiu

Charles Scharf, the CEO of Wells Fargo, summed up my own feelings about meetings with, “Meetings should have as few people as possible, but all the right people.”

It was apparent that the American Academy of Developmental Medicine

and Dentistry (AADMD) subscribed to this axiom in creating a milestone historic meeting at their annual meeting on June 14th in Orlando, Florida.

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first (and only) time the Presidents of the American Medical Association (AMA) and the American Dental Association (ADA) met to discuss the state of healthcare for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities and the role of organized medicine and dentistry.

The AADMD knew the conversation had to be focused, revealing and impactful, and they certainly recruited the right person to serve as the facilitator. The Honorable Neil Romano is a respected advocate for people with disabilities with over 40 years of experience working for five presidents in the area of employment for people with disabilities, healthcare promotion and human rights. He received a

Presidential appointment as the Chairperson at the National Council on Disability (NCD, www.ncd.gov), and continues to serve as a council member, as well as a Presidential appointment as the Chair of the President’s Committee on People with Intellectual Disabilities (www.pcpid.gov). Neil was a former Assistant Secretary of Labor in the Division of Disability Employment. He was the creator of Oral Health America’s National Spit Tobacco Education Program (NSTEP) which, at the time, was the largest and most successful program promoting oral healthcare in the world. Neil is fluent and well versed in the long standing and shameful health disparities experienced by people in the disability community.

As luck would have it, both the ADA and AMA Presidents came from the primary care trenches, where healthcare for patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities are either derailed, neglected, undertreated, or begin a pathway to appropriate comprehensive and collaborative healthcare.

Dr. Cesar Sabates, President of the American Dental Association, was a general dentist and had numerous patients with disabilities.

He was the first Cuban-American dentist to be elected as the President of the American Dental Association and has a keen appreciation of the struggles inherent in belonging to marginalized populations.

Dr. Gerald Harmon has a Family Medicine practice in South Carolina and understands how patients with disabilities have been historically stigmatized, devalued, and often considered a burden by medical practitioners.

As stated at the beginning of this article, “…all the right people.”

Dr. Sabates and Dr. Harmon acknowledged the historic shortcomings of both physicians and dentists in not having the skills, training and experience that is required to provide access to competent care for people with (all) disabilities across the lifespan. Mr. Romano reminded the audience that of the 192 medical schools and 66 dental schools in the United States, few offer any standardized curriculum in the clinical treatment of patients

Left to Right: Dr. Carl Tyler, Hon. Neil Romero, Dr. Allen Wong, Dr. Gerald Harmon, Dr. Cesar Sabates, Dr. Rick Rader

with disabilities. Research has demonstrated that the overwhelming majority of medical and dental school graduates personally feel they do not have confidence in their ability to provide competent care. Interestingly enough, those same students overwhelmingly would like to treat patients with complex needs.

Several significant concerns that contribute to healthcare disparities were discussed and included poor reimbursement, problems with communication, high turnover of support staff, clinician bias and negative attitudes about people with disabilities, lack of knowledge of disability syndromes, erroneous belief that care requires “specialization”, and time constraints dictated by managed care organizations.

The questions posed during the Presidents’ fireside chat took aim at the history of disregarding people with disabilities, in both the medical and dental profession. Dr. Sabates and Dr. Harmon acknowledged the historical shortcomings of physicians and dentists who were under-educated, ill-equipped, and unwilling to treat people with disabilities. They renewed their commitment to move both the ADA and AMA towards addressing this national disparity of care.

The AMA and ADA Presidents outlined plans to provide clinical competency training to both medical and dental students, and assured people with intellectual disabilities would be appointed to the committees that develop those plans.

The fireside chat with Dr. Sabates and Dr. Harmon was hosted at the AADMD’s One Voice Conference, the only conference that brings all health disciplines together for IDD. This year’s 20th Anniversary conference, held in Orlando, FL, was held directly before the Special Olympics USA Games. The conference theme “The Way Forward: How to Live Well” explored how to pick up the pieces following the pandemic and allow the IDD patient population to live well – especially during times of crisis.