5 minute read

Nothing is Written

Rick Rader, MD, FAAIDD, FAADM - Editor in Chief

THE CASE OF the Elephant, the Bridge,

Advertisement

and the Determined Parent

Iwas duped.

Growing up, thanks to my vast comic book collection, I believed that Superman was the Man of Steel.

It was not until I took a college economics course that I learned that Andrew Carnegie was actually the Real Man of Steel.

The mid-1800s saw incredible innovations across America. We saw the development and distribution of railroads, cameras, telephones, electric lights, and oil supplies. Not to be overshadowed by those behemoths of ingenuity, we also saw the invention of Levi Strauss and his “blue jeans.”

The major mode of transporting goods was with steamboats. When rail cargo was offloaded, it was put on steamboats, ferried across the wide and swift Mississippi River and then reloaded onto other trains. The major obstacle was the Mississippi River and constructing a bridge across it was thought to be “unbuildable.” Up until this time, “iron” was the material that built America. Iron machines were invented to do the work on farms, in factories, and buildings.

At the onset of the Civil War, Carnegie, an immigrant from Scotland, owned the Keystone Bridge Company. It was about this time that a civilization-changing discovery was made. When you took a mixture of iron and carbon metals from the earth, heated them at very high temperatures, you wound up with steel, a material that was stronger than iron.

Jo Carol Hebert, writing in Smarty Pants Magazine for Kids (that’s really the name!) brings the story forward: “In 1867, Carnegie sets out to do the impossible. Build a road-railway bridge across the wide waterway to the Mississippi River to St. Louis. It was the longest bridge ever and the first time to use steel on a large scale. The bridge would not only span the river, it would link the East of America to the Western Frontier.” So, this was a big deal.

From the very beginning, it was a project with a vast array of problems, frustrations and financial setbacks; but

Carnegie was tenacious, and seven years later, the bridge was built and ready for the first public crossover.

At the time, bridge building was apparently not an exact science. One in four bridges failed, and trains, passengers, and cargo were thrown into a watery grave. The public was expectedly both skeptical and cynical about this steel stuff, and no one was willing to be the first to test it out.

Carnegie was faced with a bridge with no takers and started to hear it referred to as “Carnegie’s Folly.”

Carnegie had heard that elephants had a natural instinct that would cause them to hesitate to walk across foundations that were unstable and unsafe. They used their trunks to test the structural integrity of surfaces and only placed each foot in tested spots.

On the opening day of the bridge, Carnegie found the biggest elephant around and proceeded to have him march across the bridge. The elephant stepped lively and never hesitated.

The Eads Bridge, named after the designer, still stands today, over a hundred years since that pachyderm sauntered across the bridge.

While it took an 11,000-pound beast to demonstrate how we can rely on the strength of things we built, it only takes a 120-pound female (give or take) to demonstrate how strong her resolve is regarding the strength of parents of children with special health care needs.

The disability rights movement is currently the strongest, most influential and steadfast in its history. It evolved because of the discovery that if you take equal parts of parental anger, frustration and determination, and mix it with equal parts of collaboration, diligence and perseverance, and heated them at high temperatures, you’d wind up with something steel-like – something we call, “Human Exceptionality.”

This quote from T.E. Lawrence implies that nothing is inevitable, life consists of choices, and how the individual can make an impact on his/her destiny. The disability community continues to reinforce and remind me of this; hence the name for my monthly musings.

- Rick Rader, MD, FAAIDD, FAADM

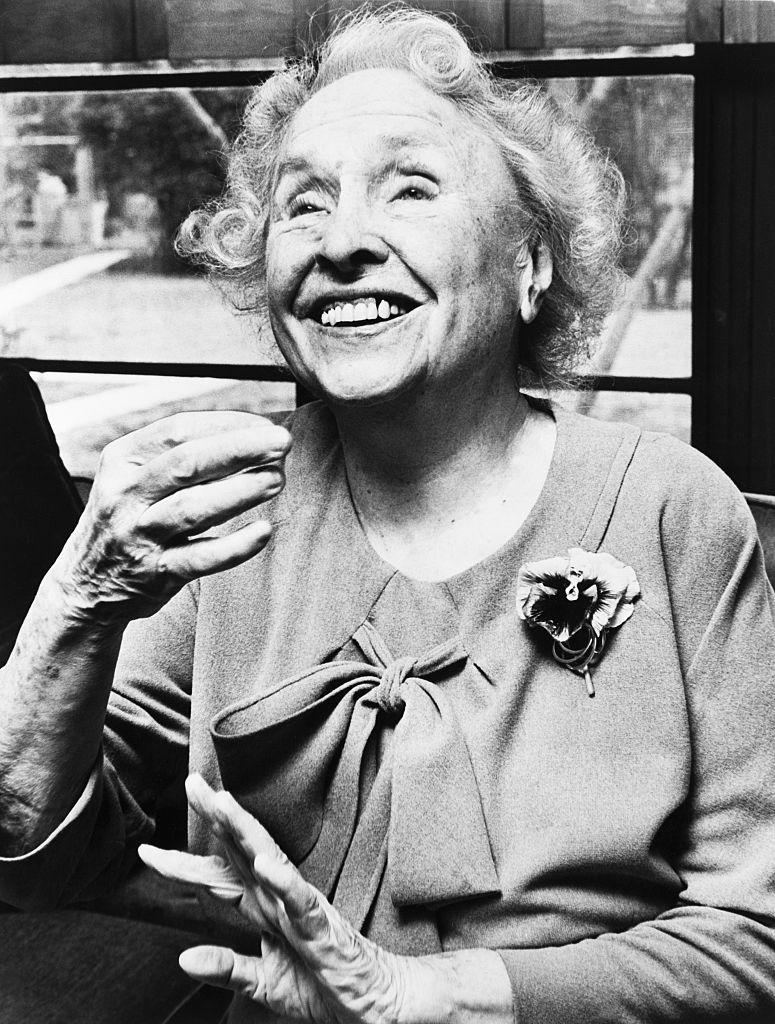

Why Helen?

Alone we can do so little; together we can do so much.

- Helen Keller

HELEN: The Journal of Human Exceptionality pays tribute to Helen Keller. Ms. Keller is perhaps the most iconic disability rights advocate and an example of how an individual with complex disabilities found and used her stamina, perseverance, resilience and determination to accomplish great things.

She lost her sight and hearing at the age of 19 months, in an age where there was no early intervention, no special education, no bona fide therapies, and little hope for individuals with severe disabilities. She became the first deaf-blind person to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree, wrote 14 books, and delivered hundreds of speeches. She campaigned for women’s suffrage, labor rights and world peace, supported the NAACP, and was an original member of the American Civil Liberties Union. She visited 35 countries around the globe, advocating for those with disabilities.

Helen personifies the spirit, mission and vision of The Journal of Human Exceptionality. Her remarkable life is a reflection of her determination; she inspired us with her words, “What I’m looking for is not out there, it is in me.”

Collaborative Organization Mission Statements

Helen: The Journal of Exceptionality is proud to be endorsed by the nation’s leading organizations that advocate for people with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD).

The AADMD is resolved:

To assist in reforming the current system of healthcare so that no person with IDD is left without access to quality health services.

To prepare clinicians to face the unique challenges in caring for people with IDD.

To provide curriculum to newly established IDD training programs in professional schools across the nation.

To increase the body and quality of patient-centered research regarding those with IDD and to involve parents and caregivers in this process.

To create a forum in which healthcare professionals, families and caregivers may exchange experiences and ideas with regard to caring for patients with IDD.

To disseminate specialized information to families in language that is easy to understand.

To establish alliances between visionary advocacy and healthcare organizations for the primary purpose of achieving better healthcare.

It is the purpose of the American Academy of Developmental Dentistry (AADD) to establish postdoctoral curriculum standards for training dental clinicians in the care of patients with IDD, to establish clinical and didactic training materials and programs to promulgate these standards, and through its certifying entity – the American Board of Developmental Dentistry – to grant board-certification to those dentists who have successfully completed these training programs.

The American Academy of Developmental Medicine (AADM) is a medical society dedicated to addressing the complex medical needs of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities across the lifespan. It incorporates clinician training and awareness, teaching, advocacy, research, board certification, health equity, interdisciplinary collaboration, inclusive care delivery models and shared decision making.