CLARITAS

A JOURNAL OF CHRISTIAN THOUGHT

FEATURING

Why Cornell Can’t Love You Down Bad? Good.

The Customer Is Not Always Right

FEATURING

Why Cornell Can’t Love You Down Bad? Good.

The Customer Is Not Always Right

is the Latin word for “clarity,” “vividness,” or “renown.” For us, Claritas represents a life-giving truth that can only be found through God.

Cornell Claritas is a Christian thought journal that reviews ideas and cultural commentary. Launched in the spring semester of 2015, it is written and produced by students attending Cornell University. Cornell Claritas is ecumenical, drawing writers and editors from all denominations around a common creedal vision. Its vision is to articulate and connect the truth of Christ to every person and every study, and it strives to begin conversations that involve faith, reason, and vocation.

If I asked you to give me a definition of love, you would probably respond with something pithy and Cornell-worthy. To will the good of the other. But this would be a bit of a lie, wouldn’t it?

We more likely understand love, for good or bad, in a series of moments. A tender word de-escalating an argument. Apologetic rambling during a breakup. The look in a mother’s eyes. The pangs of loneliness in our dorm rooms.

These moments aren’t translatable, so we resort to cliches in explaining love to one another. Think of all the things we say love is: Blind. A choice. Patient and kind. All you need. Dopamine. A verb. Eternal. Equally applicable to Terrace burritos and your mother.

With this issue of Claritas, we’re hoping to move beyond these cliches to specific perspectives on love: Loving institutions that can’t return the feeling. Loving by noticing our surroundings. Loving customers at Dunkin’ Donuts. But despite their uniqueness, each article, poem, and art piece stems from a central truth, a truth so beautiful that we’ll never grow tired of saying it. God created humanity and then died for its sins, and he did so out of pure love.

If these pages push you even a step closer to understanding that fact, we’ll consider the nagging emails to writers and late-night editing in Rockefeller Hall well worth it. We hope you’ll have a conversation with a friend about what you read. Because although we don’t know exactly who you, the reader, are, we created the Love issue because we love you. And what good is love if it’s not shared?

Love, Jack Kubinec Editor-in-Chief

Editor-in-Chief, Editor

Jack Kubinec

Jason Lan Business Manager, Editor

Joaquin Rivera Managing Editor, Contributor, Editor

Jacob Brogdon Production Manager, Editor

Estelle Hooper Design Manager, Editor Blog Manager, Editor

Krystal Ohuabunwa

Debbie Jung Social Media Manager, Designer

David Johnson Contributor, Editor

Annina Bradley Social Media Manager, Contributor, Editor

Alexander Burnett Blog Manager, Editor

Christine Shi Contributor

Raena Prude Contributor

Jesusla Sinfort Contributor

Frank Fang Contributor

Kimberly Valadez Contributor

Dara Gonzalez Contributor Contributor

Katherine Becking

Jennalee Dunn Contributor

Mairead Clas Contributor

Kailyn Liu Contributor

Nate Lo Editor

Joe Dill Editor

Peter Biles Advisor, Editor

Jackie Kim Designer

Michelle Liu Contributor, Designer

Charlie Hill Designer

Ro-Ann Shen Designer

Editor-in-Chief, Editor

Jack Kubinec

Jason Lan Business Manager, Editor

Joaquin Rivera Managing Editor, Contributor, Editor

Jacob Brogdon Production Manager, Editor

Estelle Hooper Design Manager, Editor Blog Manager, Editor

Krystal Ohuabunwa

Debbie Jung Social Media Manager, Designer

David Johnson Contributor, Editor

Annina Bradley Social Media Manager, Contributor, Editor

Alexander Burnett Blog Manager, Editor

Christine Shi Contributor

Raena Prude Contributor

Jesusla Sinfort Contributor

Frank Fang Contributor

Kimberly Valadez Contributor

Dara Gonzalez Contributor Contributor

Katherine Becking

Jennalee Dunn Contributor

Mairead Clas Contributor

Kailyn Liu Contributor

Nate Lo Editor

Joe Dill Editor

Peter Biles Advisor, Editor

Jackie Kim Designer

Michelle Liu Contributor, Designer

Charlie Hill Designer

Ro-Ann Shen Designer

Joaquin Rivera | trading our disappointment with Cornell for love of our neighbors

Joaquin Rivera | trading our disappointment with Cornell for love of our neighbors

I love Cornell.

No, really. This is a really special hilltop where I have had my best memories, my greatest friends, and my deepest growth. But an interesting question I often ponder is: Does Cornell love me back? Can this institution, with its vast resources, satisfy the craving for love that I and all my fellow students have? Well, you can’t say it hasn’t tried. Vice President Ryan Lombardi bombards me with emails that express how much he appreciates me. Cornell tosses us a few free sweatshirts, free popcorn a few days a week, and a whopping 20 free pages for printing. Generous gifts, sure, but their positive benefit just isn’t quite balanced with the stress I am having about my Labor Law final.

Now, I don’t mean to slander everyone behind these various institutions. I have had great personal interactions with Ryan Lombardi (never got a selfie though). And it makes sense that we want this institution to care for us. After all, it has the distinction of being an Ivy League institution with a massive endowment, and has frequently espoused a commitment to caring for the wellbeing of the community.

[1] However, I think it is vain to look to Cornell for love. Everywhere on campus, I can see signs of despair. An etching on a desk in the Olin Stacks reading “F*** school.” Writing on a chalkboard saying “Why can’t anyone just give me a job?” A Reddit post on r/ Cornell from four months ago states “I was glancing at the reddit’s [sic] of each of the Ivy League schools and there were a lot more panic/existential dread posts on [Cornell’s] IMO.”[2] We want to be valued. We want someone to stand beside us in our trials. Free popcorn in Willard Straight won’t solve that need.

Students have tried to remedy this by turning the lack of love into anger directed at Cornell. A Daily Sun article lambasts Cornell for its misguided approach to new housing. [3] Yet

another describes how Cornell’s athletic infrastructure is not “Ivy League material.”

[4] Obviously, it is a good thing to hold the university accountable, but is there a point to which all this negativity creates more harm than good?

I recently attended a presentation by a senior who talked about the lessons she had learned throughout college. Her primary involvement on campus had been to advocate for more student support, and she had been on the frontline directly speaking to President Martha Pollack and organizing rallies on Ho Plaza. She was proud of the work that she did, but the constant activism burnt her out. In her final months here at Cornell, she found that the best way to help this campus was not to rage at the administration, but simply, to love. She sought to personally help individuals who needed her help. She brought those around her together by hosting meals and other events. So perhaps asking “How can Cornell love us better?” is the wrong question, and we should rather focus on how we can love Cornell better. Isolation, stress for a prelim, and anxiety about our futures grip us all. What if instead of blaming and raging at this institution, we devoted our thoughts to understanding that the person sitting next to us in Human Bonding is also suffering, and just needs love?

In her final months here at Cornell, she found that the best way to help this campus was not to rage at the administration, but simply, to love.

We are not wrong in hoping for help from a larger power. Sometimes we can feel discouraged by the small scale effect of our efforts. We can feel that it is unrealistic to maintain a constant disposition of love. We want to believe in a greater significance behind our actions. And Cornell is not that greater power.

The Bible speaks of a God that understands our struggles and brokenness. He understands that we need more than 20 pages of printing. We need a Savior. It speaks of Jesus, God in flesh, who came down to Earth and helped those around Him. It was prophesied that He would come and save the world, and people thought that this would look like a violent overthrow of the institutions of their day. But that’s not what He did. He loved and ministered to the people around Him. He did not wait for people to love Him before He reciprocated, instead loving everyone first because they were his people. He healed those in society

that no one else wanted to touch. He sat down and ate with those whom everyone else considered unforgivable. He taught a vision of love that was sacrificial, serving, and humble. And most of all, He lived out that vision of life in the most compelling act of love, by being nailed to a cross and dying a slow death, taking our sins with Him.

Now I am not saying that as Cornell students, we should not ever criticize this university. There certainly is a place for those Daily Sun articles that point out the flaws of this institution. Jesus, too, spoke against the leaders of His day. Perhaps most famously, Jesus went into the Temple and overturned the tables of all people who were trying to sell goods there. But this was not the core of Jesus’ ministry. He understood that to bring change, He was to set His eyes on those around Him. And to change their hearts, He poured out His own. This is powerfully demonstrated in Chapters 4-5 of the Gospel of Matthew. Chapter 4 describes the famous Temptation of Christ, in which Satan directly approaches Jesus and tries to win Jesus’ allegiance by offering gifts. One particular offer from Satan is that he will give Jesus dominion over the world only if Jesus bows down to Satan. But Jesus rejects this. Instead, in Chapter 5, Jesus preaches the famous Beatitudes, saying, “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven. Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted. Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the world.” [5] The radical message of Jesus was that we should not be wrapped up in society’s perception of power and what it means to bring change, but that we should see the value in everyone around us, and that true change starts by recognizing that fact.

There is a famous Bible passage that reads “[God] will judge between the nations and will settle disputes for many peoples. They will beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation will not take up sword against nation, nor will they train for war anymore”. [6] It’s a verse most often interpreted as referring to the

Christian idea of heaven or to the idea that nations should demilitarize and focus more on peaceful development. But I think this verse can powerfully apply to our lives on campus. Except for some crazy clubs on campus like the Historical European Martial Arts club (yes, I am a part of this), we don’t really have the problem of literal swords on campus. But I think we have many instances where we use our resources and talents for more militant or blunt means, rather than for loving those around us. For instance, what if we took all our metaphorical “swords” that we constantly wave at Cornell in the literal form of disparaging speech and articles, and used all that energy to instead attend to the needs of our peers?

For instance, what if we took all our metaphorical “swords” that we constantly wave at Cornell in the literal form of disparaging speech and articles, and used all that energy to instead attend to the needs of our peers?

I’ll admit, when I opened this piece by saying that I loved Cornell, it was a bit of an empty statement. Yes, I can say I love this place for what it has given me, but the Christian way of loving something should extend far beyond that reason alone. In a post by the Cornell Undergraduate Admissions about the “Top Ten Reasons to Choose Cornell”, they tell us that we should love this place because it offers us friends, scenery, professors and alumni. [7] But what if these things fail, is our only option then to hate Cornell? Is it possible to see Cornell in its entirety, beyond the “Top Ten Reasons”, seeing even all the brokenness and faults, and still choose to love it? The 20th century writer G.K. Chesterton in his book Orthodoxy gives a brilliant picture of the significance of loving the institutions we find ourselves in. He talks about the dilapidated London neighborhood of Pimlico, and discusses what it would mean for someone to love Pimlico, writing “Let us suppose we are confronted with a desperate thing—say Pimlico… It is not enough for a man

to disapprove of Pimlico: in that case he will merely cut his throat or move to Chelsea. Nor, certainly, is it enough for a man to approve of Pimlico: for then it will remain Pimlico, which would be awful.” [8] A love of Pimlico cannot be pure pessimism, nor can it be pure acceptance of everything that is going on. One could argue that we are here at Cornell for such a short time, that it may not justify what may be vain efforts to make it better. But Cornell is here permanently, and our actions can change it for the better for all those in the future. We are forever linked to this campus, and not just through LinkedIn. We are forever linked to this campus, and not just through LinkedIn.

Given these connections, what are we to then do? Chesterton goes on, “The only way out of it seems to be for somebody to love Pimlico: to love it with a transcendental tie and without any earthly reason.” Sure, there could be a number of earthly reasons why you might give some love to Cornell. Maybe you are thankful for your professors, the dining halls, or maybe you really are obsessed with the Willard Straight popcorn. But the point is that love should not be transactional. We should seek to give more than we are given. Back when I was a senior in high school and in a frantic search for a place to give money to for the next four years, my eyes were set on Princeton (forgive

me). In my research on Princeton, I came upon a video where current students were being interviewed. One of them was asked something like “What do you think old alumni would think of all the changes that have happened to Princeton?” To which the student replied, “Well, to start, I hope that they don’t think it’s their Princeton anymore. It’s our Princeton.” And while their Princeton never became my Princeton, much to my chagrin on Ivy admission day, I am nevertheless struck by that quote in relation to Chesterston’s message here. Yes, the four years here could potentially be treated as a burden to bear, but why should we not see it as a gift to steward? These four years should not be just another generic period of time where thousands of students simply exist as cogs in a machine. Rather, these four years should be embraced as a unique and vibrant time where a different mix of wonderful people are different from the period before. Thus, we should love this place, because we are here, because it is ours.

love that has been the cause for flourishing cultures, saying, “If men loved Pimlico, arbitrarily, because it is THEIRS, Pimlico might be in a year or two fairer than Florence… This, as a fact, is how cities did grow great… Men did not love Rome because she was great. She was great because they had loved her.” Chesterton mentions the city of Florence, a beautiful city, built on the wealth of great families of the Renaissance. But just because it was great once does not mean that it would necessarily remain that way. People had to be there to love it and nurture what was there. How many other great cities have been lost to time and abandoned? Although not everyone can agree that Cornell as a whole is great, I’m sure everyone has some part of life here that means something. Those things do not just magically remain great, but the task is for us to help maintain what is good about them. And in the same way that we have to love in order to maintain what is great, our love can also remake what is broken. Every action of love, no matter how insignificant it may feel to us, serves to shape the future of the places we inhabit.

And what ties together Chesterton’s argument is that our connection to the places we inhabit is linked to the connection we share with God. Psalm 24:1 reads “The earth is the Lord’s and everything in it, the world and all who live in it.” Cornell is the Lord’s, and we are the Lord’s, so we should honor this place and care for it as we would our fellow brothers and sisters. We ought to love because, and we have the ability to love, because He showed love to us. He gave us the command that we ought to love our neighbors. No qualifications attached. He did not say that we should love if someone acts like this or if we are in a good mood and not busy at the time with a problem set. We are where we are because we are the instruments of God’s plan to show His love and compassion to the world. So how could we waste our time looking down on Cornell with apathy and negativity?

it back. No, we won’t have Daily Sun articles praising or tearing down our individual actions, yet our actions nevertheless have tangible meaning that improves the lives of those around us. Maybe I can’t change how Cornell loves me. But I sure can try to change how I love Cornell and all the wonderful people that I share life with on this little campus on a hill. G.K. Chesterton said that by showing an arbitrary love to Pimlico, it may soon surpass the beauty of Florence. I will end by echoing the sentiment, and contend that if we really try to love this university with a transcendental love, we might actually be the standard for “Ivy League material” one day.

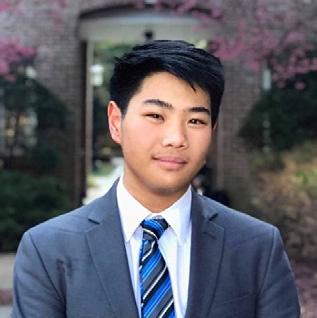

Joaquin Rivera is a sophomore in ILR, but also has a minor in Classics, which everyone says fits his vibe better. He’s from Houston, sorta, because his family moved out over the summer. As Managing Editor, he vigorously tracks the progress of every article, and oddly enjoys doing it. He also loves acting in Shakespeare shows, drinking white chocolate steamers, and telling everyone about Rome.

[1] Lombardi, Ryan. Preparing for February Break, email, 2023

[2] Annual-Pomelo-1508, Reddit, December 17, 2022. ”Which Ivy League has the most stressed students? : r/Cornell (reddit.com)

[3] Brendan Kempff, “What Cornell got Wrong about Housing.” Cornell Daily Sun. February 9, 2022

[4] Brendan Kempff. “We’re not Ivy League Material.” Cornell Daily Sun. March 9, 2023.

[5] Matthew 5:3-5 (NIV)

[6] Isaiah 2:3 (NIV)

[7] Angela Herrera-Canfield, “Top Ten Reasons to Choose Cornell.” Cornell University Undergraduate Admissions Office. March 16, 2015. “Top Ten” Reasons to Choose Cornell | Cornell University Undergraduate Admissions Office

[8] Chesterton, G.K, Orthodoxy, 1908.

Chesterton then finishes the thought by arguing that it is this transcendental

Cornell’s job is not to love me. It can try to please me, and whether it does or not, my mission should be to love

Thus, we should love this place, because we are here, because it is ours.

Katherine Becking | learning to live with loneliness

Katherine Becking | learning to live with loneliness

When I was growing up, my family moved to a new state about every two years because of my dad’s career in the Army. More often than not, I would start the school year in a brand-new place where I didn’t know anyone. Leaving our old town, old home, and old friends was painful. And in my mind, the only way to overcome my grief was to make new friends. As such, I have spent years of my life trying to get people to like me.

As an introvert, it always took me a long time to develop friendships. In many places we lived, I was lonely until just before we moved away. My junior year of high school was an especially dark time. We had just moved, and my dad had deployed to Afghanistan. In my loneliness, I became numb to everything good in life. Despite my desire to make friends, I was too bitter and exhausted to talk to anyone at school. I felt like I had been left outside to freeze in a blizzard. I would wake up in the middle of the night to eat oatmeal, cry, and yearn for the day that we would live somewhere long enough to put down roots and build lasting relationships.

Weary from hours of studying, we scrawl melodramatic messages on the desks in Olin Library: “Is anyone out there? / To love / To laugh with.”

Indeed, relationships are generally more fulfilling than status and material wealth. An 80-year long Harvard study on aging found that “close relationships, more than money or fame, are what keep people happy throughout their lives.” [2] But often, we take this to the extreme. We treat the people we love as if they can cure all our mortal afflictions.

We treat the people we love as if they can cure all our mortal epitomizes this view. In the song “Cornelia Street”, she describes her relationship with Joe Alwyn as “my religion” (although in another song she admits that maybe “it’s a false god”). [3,4] The couple has since broken up. The idea that we can attain perfect happiness just by finding someone who truly loves us is appealing, but it falls apart in reality.

This holds true in my own experience. Now that I am in college, I have more close friends than my high school self could have imagined. I live in a warm cocoon of community, and most of the time, I am content and grateful. But there are moments (usually when I’ve been awake for too long) when loneliness seeps back into my mind like cold air through my leaky dorm window. I feel left out or worry that my friends are sick of me. I feel like my gifts and personality are underappreciated. No one here really knows who I am.

But there are moments (usually when I’ve been awake for too long) when loneliness seeps back into my mind like cold air through my leaky dorm window.

These feelings reveal an uncomfortable truth: human relationships fall short of providing complete happiness. We are reluctant to admit it because it’s terrifying. Love is the best thing we have in this world, and if other people can’t bring us joy, then what can? Are we cursed to be forever dissatisfied with life?

Actually, yes. As a Christian, I believe that we were created by God, and designed to be in relationship with Him and with other people. But we turned

away from God to seek happiness on our own terms. Separated from the Giver of life and love, we became separated from each other.

The biblical story of the Tower of Babel can be interpreted as a retelling of the fall. In Genesis 11, humanity decides to build a tower to the heavens to “make a name for [them]selves.” [5] God sees their pride and says, “Come, let us go down and there confuse their language, so that they may not understand one another’s speech.” [6] Humanity then abandons the tower and disperses throughout the earth.

This story is generally used to explain the existence of different languages in the world, but it also serves as a metaphor for the emotional isolation of individuals. Because of our rebellion against God, there are barriers of communication between us. We may speak the same language as our friends, but our speech is limited and our understanding is too narrow to comprehend the depths of one another’s hearts.

Furthermore, even if we could fully understand others, we are too selfish to love them unconditionally. Both secular research and the Bible attest to this fundamental issue. One study by Indian researchers found that if given superpowers, people would generally use them for selfish gain rather than to benefit society. [7] Psalm 53 says that “all have become corrupt, there is no one who does good.” [8] Because of our sin and mortality, we can only experience a shadow of the love and community for which we were made. This is why we feel dissatisfied and lonely even when we are surrounded by loved ones.

The evidence of human brokenness is all around us. Some friends cancel lunch plans to do work. Others aren’t there when we need their support. Many Cornellians share Daily Sun writer Vanessa Olguín’s experience of losing touch with high school friends who they were so sure would be in their lives forever. [9] It often feels, as one library graffiti artist states in blue gel pen, that “Love Sucks”. [10]

Fortunately, although human love is fallible and insufficient, God’s love is perfect and fulfilling. He understands us completely because He made us and knows our every thought. God even became one of us as Jesus Christ, experiencing the same emotions that we do. Jesus was chronically misunderstood, and His friends abandoned Him in His darkest hour. He was “despised and rejected by men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief.” [11] No one else could fathom what it was like to be a perfect person in a fallen world. Whatever loneliness we feel, Jesus has felt more, and He can empathize with us.

Furthermore, God’s perfect character allows Him to love us despite knowing us completely. This is naturally hard for us to accept. We tend to think God is as easily repulsed as we are, when in fact He is more gracious than we can imagine. In Isaiah 55, God says that “as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways and my thoughts than your thoughts.” [12] One commentator writes that this passage specifically refers to God’s thoughts being “thoughts of love and compassion that stretch to a degree beyond our mental horizon.” [13] I sometimes worry that if my friends knew me better, they wouldn’t really like me. Regardless of whether that is true, God will never cease to love us even though He sees our worst offenses.

God made us out of love and for love. Our gut instinct that love is the best

thing in the world is true. We just have to remember that it is God’s love, not human love, that has the power to heal and fulfill us. All other loves are mere shadows of His abundant and everlasting grace.

Love from other people can never take the place of God’s love. And unfortunately, in this life, we will always be a little bit lonely. We live in the suspenseful time after Jesus has defeated death but before God has renewed the whole earth. We are not instantly cured of our selfishness and isolation when we put our faith in God. When Christ returns and redeems the whole world, we will be fully healed of our loneliness. But until then, we must live with it.

Surrendering to the inevitability of loneliness may seem depressing, but in fact it is freeing. It allows us to stop seeking fulfillment in human relationships. I have been blessed with a loving family, but their love never felt like enough, so I spent years trying to win the approval of my peers. Yet now that I have several close friends, I am still discontent. I continue to seek validation from ever-widening circles of people. I need everyone to love me, and it’s exhausting. Yet I know that it is futile to chase the approval of others. The great thing about God’s love is that we

don’t have to chase after it. He readily extends it to us.

Additionally, when we realize that human relationships are inherently flawed, we can stop holding those we love to an impossible standard of perfection. For a long time, I have had complicated feelings about my dad. On the one hand, he is gentle, wise, and patient. His life is one of the best pictures of selflessness that I have, and his love as a father reflects God’s fatherly love. On the other hand, my dad’s career in the Army has caused me deep grief and depression by requiring us to move so frequently. I often resent his choice of career, especially since he was a military kid himself and as a teenager swore that he would never inflict this lifestyle on his own family. It is extremely hard to reconcile my dad’s love and goodness with the pain I experienced growing up. In my heart, I know that he is a fallen human, and that I cannot expect him to be perfect. I am gradually building a bridge of forgiveness as I internalize this reality.

There is one more bright side to the fallibility of human relationships: they make grace more visible. There is something beautiful about friendships that persist through disagreement and conflict. My friends disappoint me sometimes, and I have disappointed them, but we still love each other. Our

brokenness is an opportunity for grace and forgiveness to shine. And it is an even greater opportunity for God to reveal His much more abundant grace to the world. This is essentially the reason for everything. God has designed all of human history to tell the story of His love. He created us, let us stray from Him, and redeems us all for His glory. One of my favorite songwriters puts it this way: “Maybe it’s a better thing… To be more than merely innocent / But to be broken, then redeemed by love.”

Katherine Becking is a sophomore studying Civil Engineering. Don’t ask her where she’s from. When she’s not tutoring for math classes, she can be found staring vacantly into the middle distance. She also enjoys painting, mixing concrete, and walking in the arboretum.

[1] Unknown Artist. n.d. Untitled Graffiti. Pencil on wood. Olin Library. Ithaca, New York.

[2] Mineo, Liz. 2023. “Over Nearly 80 Years, Harvard Study Has Been Showing How to Live a Healthy and Happy Life.” Harvard Gazette, April 5, 2023. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/ story/2017/04/over-nearly-80-years-harvardstudy-has-been-showing-how-to-live-a-healthyand-happy-life/.

[3] Swift, Taylor. “Cornelia Street.” Track 9 on Lover. Republic Records, 2019.

[4] Swift, Taylor. “False God.” Track 13 on Lover. Republic Records, 2019.

[5] Genesis 11:4 (ESV)

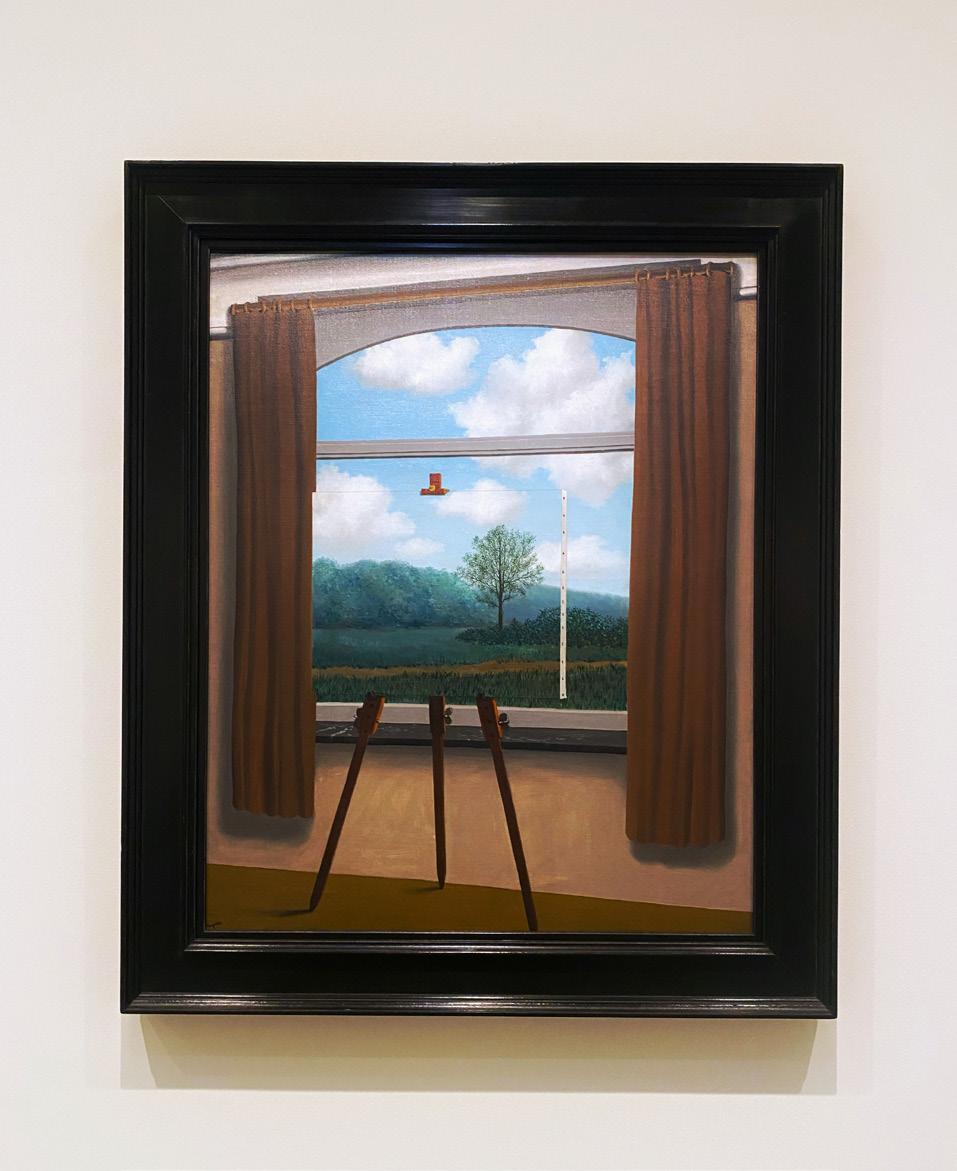

As previously mentioned, the window in my dorm room is far from airtight. One morning I woke up with ice on the inside of the glass. But I actually like it. The leaky window reminds me of how cold it is outside and makes me grateful for the warmth that I have from the radiator (and from the curtains which are somehow better insulators than the window). Likewise, I have started to see moments of loneliness as a reminder of the hope I have in Christ. My friends and family can never fill the void in my soul that was meant to be filled by God. But one day, my relationship with God and others will be fully repaired, and I will dwell in the warm house of the Lord with everyone I love.

[6] Genesis 11:7 (ESV)

[7] Das-Friebel, Ahuti, Nikita Wadhwa, Merin Sanil, Hansika Kapoor, and V. Sharanya.

2019. “Investigating Altruism and Selfishness Through the Hypothetical Use of Superpowers.” Journal of Humanistic Psychology, July. https://doi. org/10.1177/0022167817699049.

[8] Psalm 53:3 (NIV)

[9] Olguín, Vanessa. 2022. “Friendships of Proximity.” The Cornell Daily Sun. January 30, 2022. https://cornellsun.com/2022/01/30/olguinfriendships-of-proximity/.

[10] Unknown Artist. n.d. Untitled Graffiti. Pen on wood. Olin Library. Ithaca, New York.

[11] Isaiah 53:3 (ESV)

[12] Isaiah 55:9 (ESV)

[13] Ortlund, Dane C. 2021. Gentle and Lowly. pg 158.

[14] Peterson, Andrew. “Don’t You Want to Thank Someone.” Track 10 on Light for the Lost Boy. Centricity Music, 2012.

I have started to see moments of loneliness as a reminder of the hope I have in Christ.

I am kind of a music freak. If you see me on campus, I’ll have my AirPods in. My Spotify wrapped had almost 100,000 minutes last year. I analyze song lyrics in my free time and have a really bad habit of using them in my English essays (usually not to the amusement of my professors). I need music like I need breathing: I have my songs for crying, songs for laughing, and songs for studying in Uris Library, songs for being in love, songs for running my heart out, songs for dreaming about fantasy worlds, and songs for driving to Target. I am the girl at a concert who is screaming the words with her hands outstretched, as if she’ll somehow be able to communicate to the performer how much the lyrics mean to her—even while she is simply a speck in the crowd, washed out by the stadium lights.

At the New Student Convocation in August of 2019, President Martha E. Pollack delivered a speech discouraging Cornellians from wearing headphones around campus. She warned them that the destructive technology can seal them off from genuine human connection. While the message ultimately alluded to a larger theme of belonging and

exploration here at Cornell, it no doubt stirred a conversation that challenged the normalized practice of wearing headphones, especially for young people. [1] Thirty years ago, it may have been rare for a young person to choose to listen to their favorite song over partaking in a conversation with a friend, but today the popularity of music has soared in prominence— fueled by new streaming platforms, the buzz of social media, and a technologyinducing pandemic. These days, the average Spotify user listens to music for 148 minutes every day, devoting time to 40 artists weekly. [2] Notably, over half of Spotify’s user base is made up of millennials and younger people.

It is no surprise that those most wellversed in technology are readily consuming music at a rate even the meteoric rise in streaming services cannot keep up with. Things have changed, and teenagers find that throwing on a pair of headphones and tuning the world out is a relaxing, enjoyable distraction from the burden of real-life adversity. Music has a distinguished role in adolescent culture: I’m sure we all have at least one friend who badgers us on our opinion on the latest pick for Slope Day, or raves about the release of Taylor Swift’s latest album. It isn’t just the accessibility of streaming services that has created this addictive buzz around music—it is also social media platforms that propel the obsession even further than it could have been decades ago, when teens were burning CDs or jamming out to Billy Joel and Madonna on hi-fi cassette decks.

In other words, it isn’t just about the music anymore. We live in an era where fans can interact with celebrities on an intimate level—not only can they resonate with lyrics or scream their hearts out at the occasional concert, but they can watch comedic interviews on YouTube, connect with the anonymous public through internet fandoms, and

comment on their favorite musician’s Instagram post, eagerly anticipating a reply. Celebrities and popular artists are well aware of the marketing advantage that a veil of authenticity can offer them, and they are more than happy to offer us the candid TikTok video or the sporadic live stream. But for us, it almost feels like we know them personally.

This phenomenon, known as a “parasocial relationship,” described by University of Chicago sociologists Donald Horton and R. Richard Wohl as a “seeming face-to-face relationship between spectator and performer.” [3] This false sense of intimacy is also not always unintentional: Horton and Wohl note that TV personalities and musicians often “use the mode of direct address, talking as if they were conversing personally and privately” with their fans. [3] It is no secret that the overall experience of the consumer benefits from an individualized relationship with the performer: after all, it feels good to feel special. International popstar Taylor Swift’s official Instagram announcement for her “Eras Tour” is tinged with false intimacy as she writes, “I can’t WAIT to see your gorgeous faces out there. It’s been a long time coming.” [4] Yet, the superstar implies that the faces in a stadium of 60,000 people would be visible, and while most fans were at least vaguely aware of the frivolity of the announcement, her warmhearted sentiment no doubt helped sell tickets.

Unfortunately, there is a dark side. Harmless fandoms can quickly turn

It is no secret that the overall experience of the consumer benefits from an individualized relationship with the performer: after all, it feels good to feel special.

into obsessive celebrity cults where fans find themselves debating about the musician rather than the music, feeling passionately that they have a say in a stranger’s private affairs. In this era of false internet intimacy, a change in Swift’s dating life floods tabloids and comment sections, and the sight of any dreamy A-lister in a new paparazzi photo will unleash a host of Buzzfeed articles and frenzied TikTok videos. Superfans feel that they have a right to these normalized invasions of privacy not simply because of the alluring entertainment of celebrity drama, but also because they experience the illusion of a private, face-to-face relationship. Since the fan hysteria of Beatlemania in the early ‘60s, or girls drooling over heartthrobs like Jim Morrison and Roger Daltrey in the ‘80s, the typical superfan has been inflated into something several times more severe. Their love has turned from obsessive to suffocating, from joyous to feverish—to the point where regular strangers are being exalted to a level of idolatry that rivals that of a god.

Their love has turned from obsessive to suffocating, from joyous to feverish—to the point where regular strangers are being exalted to a level of

idolatry that rivals that of a god.

Ultimately, parasocial relationships are what promote our celebrities to such high pedestals. After all, they speak to us through their music, they relate themselves to us, and they treat us like old childhood friends: naturally, it can be easy to forget that the records they make are sold to millions of other people. This leads to the feeling that celebrities are inhuman or omniscient in some way; that they can somehow know us personally while also performing on a worldwide stage. The reality is that no one has that power except God. With God, we are no longer a shout into the void, and a relationship in the parasocial sense is inherently impossible. When we pray, He listens. With a celebrity, we are simply reduced to a nameless speck in a crowd of thousands.

As a Christian, I often see a problem with the extreme devotion to celebrities that much of secular culture tends to ignore. To pour your highest level of admiration into another human (as many superfans do) is to worship an idol, a false god. As God says to the Jews in Exodus 20:2-3,

I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery. You shall have no other gods before me. [5]

I regularly catch myself placing my obsessions with music or celebrity culture above my faith, and I’m not alone. While it can feel shameful, secular culture is particularly aware of this fervent aspect of the superfan and has completely normalized it, at times cheekily self-aware about the Christian sinfulness of it all (my favorite example is the satirical and infamous religious candle where Jesus’ face is photoshopped and replaced with a portrait of Harry Styles or The Rock. Seriously, search it up—you can find unlimited renditions on Etsy).

The idea of “love” when it comes to celebrity fan culture can be a tricky game. I come across the word all the time while I’m scrolling comment

sections or watching a gushing speech from the Grammys, and I rarely take a moment to contemplate the gravity of it. I’m sure we’ve all been at a concert when some desperate fan screams “I LOVE YOU!” into the gaping silence between sets—their voice painfully echoes, and the performer on stage undoubtedly hears them and offers an uncomfortable nod. Yet, we rarely take a moment to ponder what the word ‘love’ may really mean to a fan who is instinctually screaming it across rows of seats: how can they truly “love” someone they have never met?

The truth is, the person that they are loving is a made-up version of someone that they have contrived, an illusion of perfection. However, love, in the Christian sense, allows for us to see our favorite celebrities as human and love them ever more for it. The Bible is always elevating broken people, and Jesus’ love inherently searches for that brokenness and yearns to make us whole again. Sin is a fundamental element of human existence, so to hold anyone to a standard of perfection is a foolish feat. The apostle Matthew was a tax collector before he was a follower of Jesus, a man who was vehemently hated by the Jews for upholding a profession typically known for being notoriously unjust. [6] The average man would have thought it impossible to reform Matthew, yet Jesus welcomed him with open arms.

In Matthew 5:43-45, Jesus says: You have heard that it was said, “Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven.”

And in Ephesians 4:32, Be kind to one another, tenderhearted, forgiving one another, as God in Christ forgave you. [8]

At its core, Christian love is defined by forgiveness and is inexhaustible in its nature. Sadly, it struggles to fit into the modern, secularized definition of the word—especially when it comes

to celebrity culture. Social media has made us feel so much closer to the A-listers and internet personalities that we idolize, and the typical love of the superfan tends to deny even the chance that their deity could contain humanlike flaws. What follows is a vicious cycle: Without any means with which to accept the mistakes that our celebrities make (and trust me, they do make mistakes), fan culture can turn ugly and unforgiving. In return, celebrities are forced to cover up any flaw that could risk them getting “canceled” in order to maintain the image of divinity that has been brutally assigned to them.

Celebrities are forced to cover up any flaw that could risk them getting “canceled” in order to maintain the image of divinity that has been brutally assigned to them.

The looming consequence of cancel culture leads to an empty form of love that is inherently un-Christian. The superfan’s love is one born out of idolization, and not many people in the media today do well with the slapping fact that celebrities are sinners. Forgiveness is scarce and ‘loving your enemy’ is an idea seen as even more appalling as fans dig up old tweets and analyze every action with a scrutinizing

eye. For them, a mistake is a deal-breaker, a career-ending factor that they can wield like a weapon. In this way, the media’s infamous superfan— perhaps pictured as a tearyeyed teenage girl begging for Harry Styles to sign her forehead with Sharpie— wields an unlikely power. The superfan’s love can simultaneously create a top hit on the Billboard Hot 100 and catastrophically destroy a career.

Not many people in the media today do well with the slapping fact that celebrities are sinners.

As a young person, I have noticed how the craze around celebrity culture has become a notable facet of the adolescent experience. Teenagers and collegeaged students alike are widely known to show unrivaled displays of devotion to celebrities, and our enthusiasm has made us a target for social media marketing teams and Spotify playlist curators (the teen beats playlist alone has over 2 million likes. Yet, I beg the question: Why is it so easy for us to fall victim to the media’s celebrity delusion and frenzied cancel culture? Perhaps we are searching for guidance, for a way to live our lives with a greater sense of purpose. Perhaps we’re lonely and yearn for more meaningful relationships than those that we share with our peers. Or perhaps President Pollack was right: Our obsession with music has sealed us off from the world, to the extent that the made-up impression of a stranger with over 20 million monthly listeners holds more legitimacy than the relationships in our own lives.

Regardless of the reason, the fervent kind of love that we offer to these distant and glamorized figures will never lead to fulfillment. After all, the pedestal that they stand on is nonetheless a shaky one: With one mistake, we’re typing out hate comments on their Instagram post and boycotting streams. It is

through God alone that we can achieve the closeness that we yearn for—and the acknowledgment of this is the first step to healing our society’s obsessive celebrity cult. God’s glory reaches far and wide, shining on every facet of our lives. Therefore, I propose we redefine what it means to be a superfan as a Christian: to recognize the humanity we all share and love our brothers and sisters in a way that acknowledges flaws. To accept the musician as human and not to fault them for it. When loving becomes forgiving, it becomes boundless, and it becomes infinite—it is the only love we will ever need.

Mairead is a freshman from Connecticut studying English in the college of Arts and Sciences. When she’s not in classes or at track practice, she enjoys reading, writing, making pinterest boards, and listening to way too much music.

[1] Nutt, David. “Students urged to connect and engage – without headphones.” Cornell Chronicle. August 29, 2019.

[2] Nadia. “50+ Statistics Proving Spotify Growth is Soaring.” Siteefy. December 11, 2022.

[3] Donald, Horton. Wohl, Richard. “Mass Communication and Para-Social Interaction.” Department of Sociology, University of Chicago.

[4] Taylor Swift, Instagram. November 1, 2022.

[5] Exodus 20:2-3, ESV.

[6] Denman, Brett. “The Apostle Matthew.” Oregon Live. October 22, 2010.

[7] Matthew 5:43-45, ESV.

[8] Ephesians 4:32, ESV.

It is through God alone that we can achieve the closeness that we yearn for—and the acknowledgment of this is the first step to healing our society’s obsessive celebrity cult.

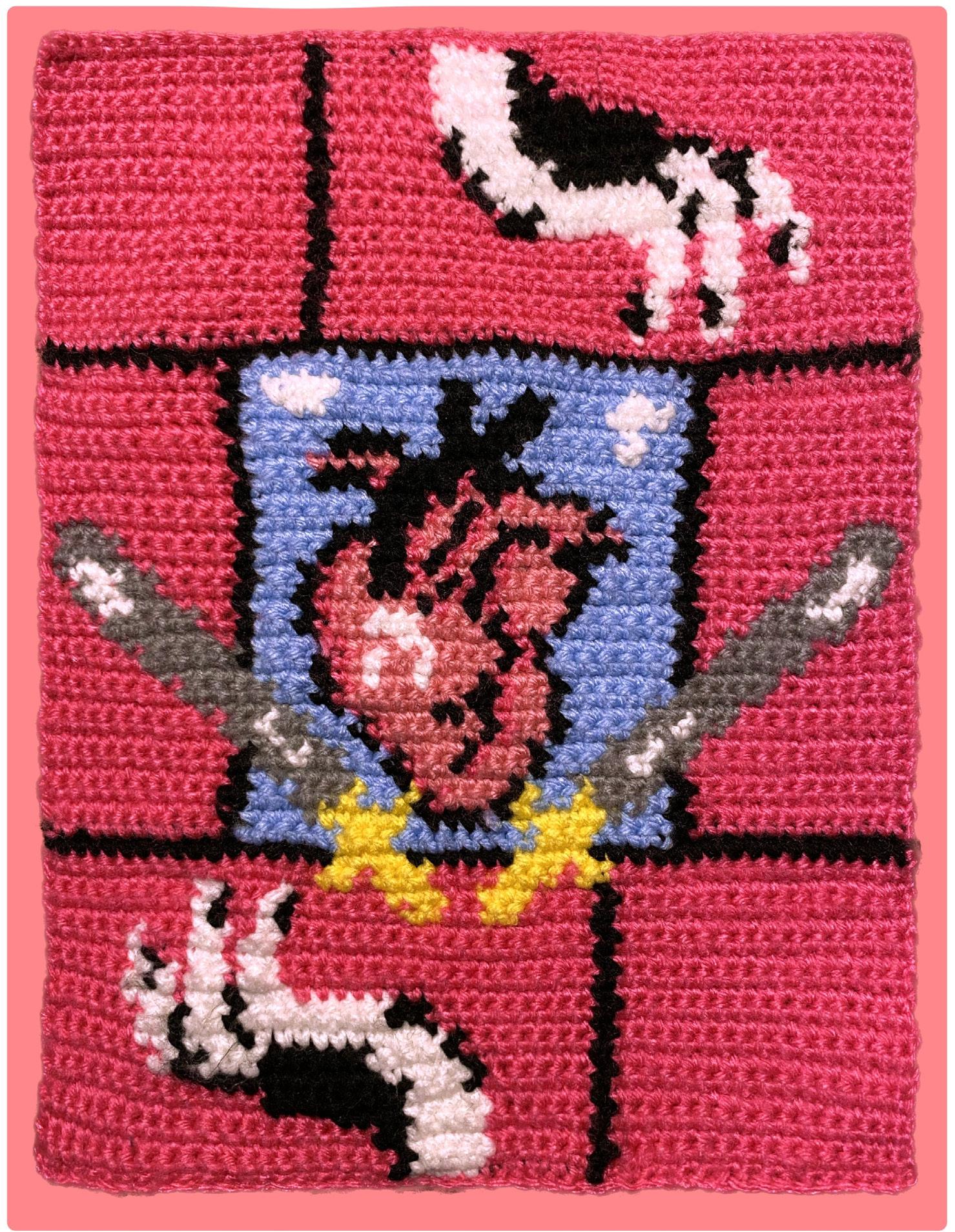

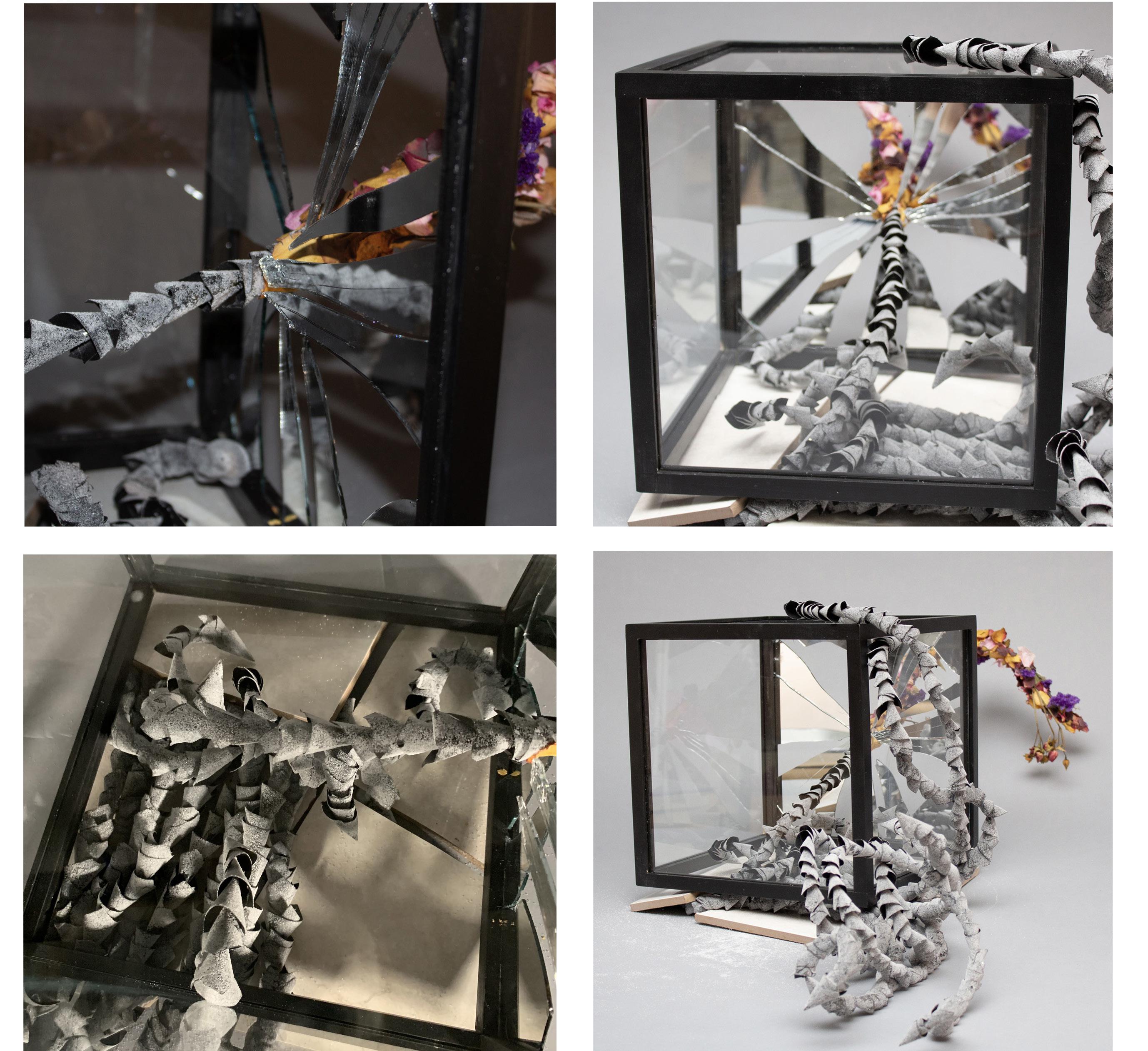

An anatomical heart is encased in a glass case, guarded by two swords. Two hands reach out from different directions but are blocked by walls surrounding the case.

This piece is inspired by the folk art of Milagros in Mexico, which often depicts hearts being struck by swords or on fire. They are carried as religious tokens of small miracles and represent love and gratitude.

I wanted to present two different meanings to protecting your heart: being protected from the dangers of the world and building barriers which prevent love from entering.

Love is not an easy task. It may be easy to say that you love food, an artist, or time with your loved ones, but letting the love settle in your heart is a long process. Being human means being imperfect and often those who love us, hurt us. While we may forgive, it’s often hard to forget. We guard our hearts against further hurt by not allowing others to love us or love them in return and become cold as we claim we are protecting ourselves.

While hands may reach out to hurt us, they also extend to help. We can guard our hearts from the dangers of the world, but in turn, we may also be depriving ourselves of love. I wanted to reflect on how much we guard our hearts and who we should truly be guarding against. We should allow ourselves to be loved and love others deeply and unconditionally. Although we may experience pain, forgiveness and love will always overcome.

Dara is a sophomore from Laredo, Texas studying English. She enjoys reading more than writing, cultivating playlists for fictional characters, watching animated shows to appease her inner child, making silly Photoshop edits at 3 AM, and learning Kpop choreography.

Dara Gonzalez | 8.5” x 10.5”, acrylic yarn, crochet hook 2.5 mmI wonder if he knows how good his hair looks messed up like that. How I feel when he acknowledges my existence, when he looks at me when we talk. What intrigue and depth of person lies behind those—quick, he’s looking, be cool and mysterious! … Last week I saw him smile to himself at what Sam said from the corner of my eye. I wonder why. He was falling asleep during class today. Maybe he was up late last night… I hope he’ll be at the meeting next week. I just want to be in the same room as him. I could talk to him forever… Agh, I’m so distracted! I shouldn’t be thinking about him this much. But I can’t help myself!

Even though we’ve all probably been down bad before, we might feel embarrassed to have these kinds of thoughts, thinking they’re “of the flesh.” We might even pull out our go-to Bible passage on romance: “The unmarried man is anxious about the things of the Lord, how to please the Lord. But the married man is anxious about worldly things, how to please his wife, and his interests are divided.” [1] Surely distractions like crushes have no place in the mind of someone who wants to give their undivided attention to the Lord.

Is that really what the Bible has to say about romance? That it’s unholy and unproductive? Are we who want to let the Word of God inform our romantic lives destined to just suppress all thoughts and feelings of love or attraction and brute-force our thoughts towards “the things of the Lord?” Pastor Jacob Gerber offers a more nuanced view: “He’s not saying that the married life is unholy, and the unmarried life is not... He’s saying that they are different circumstances, in which all of us are called to pursue holiness.” [2] Taking into view all of Scripture, Paul’s statement is not meant to turn us away from romantic love completely, but to ensure that we are not naïve about the (good) complications of lifelong love in marriage, and that whether married or single, our first desire is to be holy and devoted to the Lord. In another one of his letters, the same Paul that wrote the verses above states that marriage represents the covenantal sacrificial relationship between Christ and The Church, suggesting a high view of marriage and the love it embodies. [3] And if we want to challenge the idea that the Bible dismisses romance as a distraction, there is no better place to look than the Song of Songs.

The book of Song of Songs is an erotic poem (in God’s Holy Word!) that falls under the wisdom literature of the Bible. There is debate about its author, but many attribute it to Solomon, king of Israel circa 960 BCE. [4] There are three main characters: an unnamed young woman, an unnamed young man, and an audience of friends and family, the “daughters of Jerusalem.” The song is all about the love between the betrothed couple, capturing “the joys, insecurities, sorrows, and frustrations

that accompany the journey of love.” [5] And lest we think that it is just an irrelevant side story in the Bible’s Godcentered narrative, Pastor James L. Harvey reminds us that “God is there... superintending it all.” And it’s not just Christians that see Song of Songs as having everything to do with God— Rabbi Akira, one of the greatest Jewish rabbis of the late first century, said that “while all of the sacred writings are holy, the Song of Songs is the holy of holies!” [6]

In chapter 5 of this love poem, the woman’s friends and family ask her, “What is your beloved more than another beloved?” [7] Her response is a poem of praise for her lover:

My beloved is radiant and ruddy, distinguished among ten thousand. His head is the finest gold; his locks are wavy, black as a raven.

His eyes are like doves beside streams of water, bathed in milk, sitting beside a full pool . . .

His lips are like lilies, dripping liquid myrrh . . . [8]

Behold, the “holy of holies” of the sacred writings, going on and on about how beautiful the face of a man is! And this is fairly mild for Song of Songs. After praising her beloved’s facial features, she makes her way downward, visiting every part of his body with vivid imagery. He pours back to her praises of her hair, her lips, her breasts, her naked belly, her hips, the allure of her “garden,” and “at least allusions to the genitalia” (I’ll leave the discovery of those as an exercise for you, dear reader). [9]

So, if this is in the Bible, there must be a good way to delight in our and each other’s physical beauty. Our desires, in themselves, are good and given by God. Just think about it: there’s something so powerful about the way our world changes when we have a crush on someone. We notice them all the time. We dwell on the things they say or do. We dream of being closer to them, and do everything we can to make that dream come true, even at the expense of other

things. Attraction can so effortlessly bring out an attention, adoration, and zeal that no amount of intellect or brute force could ever conjure up.

The woman in Song of Songs knows this very well: “love is strong as death,” she sings. [10] Death is the strongest thing known to man: no one can overcome it. But love is stronger. You may know this power very well, too. But have you ever considered why it is?

The woman tells us, when she goes on to call love “the very flame of the Lord.” Love is a fire, the flame of the Lord. God created love. He is love. [11] That’s precisely why love is so strong: it comes from the very character of our infinitely strong Lord. And because it is from Him, it is also for Him. He alone deserves our worship. Just as a helpful campfire can rage into a devastating forest fire if not contained properly, love is so dangerous and destructive when it is directed away from God, who alone deserves our worship.

Love is a fire, the flame of the Lord. God created love. He is love. That’s precisely why love is so strong: it comes from the very character of our infinitely strong Lord.

Along with all the expressions of longing and delight throughout the Song of

Songs, the woman repeats this warning:

I adjure you, O daughters of Jerusalem, that you not stir up or awaken love before it pleases. [12]

Fully aware of the strength of love, she knows very well that if we get too deep in love too fast, our desire can become bad for us. The New Testament book of James gives greater insight into why this is: “But each person is tempted when he is lured and enticed by his own desire. Then desire when it has conceived gives birth to sin, and sin when it is fully grown brings forth death.” [13]

There’s nothing quite like high school drama to illustrate desire giving birth to sin. In the classic teen comedy Mean Girls, Regina, the mean, manipulative “queen bee” of North Shore High, is dating Aaron, one of the hottest and most popular guys in the school. Naturally, Cady, the new girl, develops a crush on Aaron. In her efforts to win Aaron over and bring Regina down, Cady devises various plots to sabotage Regina, including telling Aaron she was cheating on him. She finally succeeds in breaking Aaron and Regina up, but in the process she fails to obtain what she really wanted, Aaron’s love, because he realizes that she has become just like Regina. Cady’s desires had led to jealousy, betrayal, the destruction of friendships, and the loss of herself.

Furthermore, sin isn’t just negative actions that we do. Thoughts of a person and how they see us can consume our minds and crowd out thoughts of loving those around us, our sense of God, and our sight of important spiritual realities. Our attraction can take hold of us and have authority over our reasoning and actions more than God’s Word (or just common sense!). When this happens, we begin to make compromises, become divided in our loyalties, and ultimately worship someone other than God, which is sin that leads to spiritual death. Even Solomon, the putative author of the very Song of Songs, to whom God gave “wisdom and understanding beyond measure,” beyond “all other men,” was led astray by his wives to worship other gods, causing the downfall of himself and all Israel. [14]

In conclusion, we should eradicate all our desires and commit to celibacy for life… is absolutely not what I am saying.

Martin Luther says, “You cannot prevent the birds from flying in the air over your head, but you can prevent them from building a nest in your hair.” [15] We cannot help but experience attraction and temptation. Although the consequences of unguarded desire are severe, we’ve seen that our desires in themselves can be good. So what do we do when the birds fly over our heads?

Instead of shooting them down, I submit that we should recognize our feelings of attraction as given by God, pray and watch that they do not give rise to sin, and channel them toward the one who created them for Himself.

First, when thoughts of attraction first arrive, our view of attraction as God-given frees us to not immediately repress them but to be curious about them. As we are deliberately, intricately “knitted” together in our wombs by God, [16] what we are attracted to in a person tells us about ourselves, and we can thank God for how He made us and the person we are attracted to. Even better, we can consider how the attractive aspects of a person reflect the perfect character and love of Christ, the “prototype for anything truly admirable you’ve ever admired in anybody.” [17]

Just as a helpful campfire can rage into a devastating forest fire if not contained properly, love is so dangerous and destructive when it is directed away from God, who alone deserves our worship.

For example, mystery. Nothing gets me more than someone who doesn’t feel the need to bare their whole selves to the world. I like to think this is because of how God created me, reserved,

low-key, observant. But if I am drawn towards mystery, I need look no further than my Lord. Consider what Paul says of Him in Romans 11: “Oh, the depth of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are his judgments and how inscrutable his ways!” [18]

Still, we must guard these thoughts carefully, knowing how easily they can bear bad fruits. Martin Luther explains, “We cannot help but suffer attacks [temptations], and even be mired in them, but we pray here that we may not fall into them and be drowned by them.” [19] It may be easy to read this as an exhortation towards self-control. But the word “pray” is key, because it necessarily involves the help and presence of God. Without God, trying to control our desires won’t work. Why would we even want to avoid giving into them? Trying to avoid sin without having a foundational understanding of God’s goodness and sovereignty will, at best, trap us in cycles of repression, guilt, and resentment. But when we turn our hearts to God in prayer, the glory and love of God become bigger in our sight and more weighty in our hearts, giving us greater desire and strength to overcome temptation and not fall into sin. So, preventing our desires from leading to sin is inseparable from turning our desires instead towards God.

This requires admitting that sometimes we are attracted to the wrong things. Sometimes, these things are obviously problematic (e.g., meanness, entitlement, mental illness). Other times, what we most admire is not bad, but it is not what is most beautiful in God’s eyes. In Proverbs, we see that physical beauty is not as praiseworthy as the fear of the Lord, which reflects one’s character and right relationship with God: “Charm is deceitful, and beauty is vain, but a woman who fears the Lord is to be praised.” [20] Let us consider again the woman’s song about her beloved. Although she’s praising her beloved’s body, the deeper meaning within her poetic lines points “not at any extraordinary beauty of [Christ’s] body (...he had no form nor comeliness, Isa. 53:2);

but his divine glory.” [21] What we are attracted to can and should be molded to Christ and the things that make Him glorious. This is not His looks, money, or status (of which He had little), but His character, his sovereignty, and His love for us.

As we pray for the spiritual eyes to see as God sees, God applies his transforming grace to us, changing us and what we love. Coming full circle, loving God first and foremost also changes how we love. Godly love is driven by commitment and patience in God’s timing, not by impatience or volatile feelings. Godly love is not self-centered but seeks to serve the other. With it, we see those we are attracted to for who they are, created and loved by God, with their thoughts, feelings, needs, and wants, not through the lens of how they can satisfy our desires. Rather than spending time with or seeking affirmation from them because of how it makes us feel, it seeks the interests of the other before our own. [22] Pursuing godly love requires us to examine whether our love is based in selfish desires or in the selfless love of God. If it is selfish and objectifying, loving our crush can even mean consciously not pursuing them to keep a risky, off-base infatuation from growing. But insofar as our love comes from and takes after the perfect love of God, let our love abound more and more, leading to abundant joy and fullness of life, to the glory and praise of God. [23]

If it is true that another’s love and desire fuels our own, then Jesus Christ should be the most attractive person of all.

In summary, our thoughts of attraction do not have to keep us from loving God. Just think of the strength of attraction expressed in Song of Songs, which beautifully captures how we love as humans, and ultimately how Jesus loves us. Our attraction, with the vitality of the desires they conjure, can actually fuel our love for Him and love for others.

Lastly, there is a component of

attraction that goes beyond someone’s appearance or personality. It seems to be a fundamental law that we are more attracted to people when they show attraction or care for us.

If it is true that another’s love and desire fuels our own, then Jesus Christ should be the most attractive person of all. While we showed no interest in or love towards Him, Jesus loves us with the strongest love, the love that the woman in the Song of Songs sings of, “strong as death”. In His love, Christ died for us to save us from the rightful wrath of God, because that’s how much He wants us to be in a relationship with Him. So let’s look upon Jesus, our beautiful Savior. Let’s love Him “because He first loved us.” [24] Let’s say together with the woman in Song of Songs, to our beloved Jesus and anyone who will listen, “This is my beloved and this is my friend.” [25]

Christine Shi is a senior from Boston, MA. Don’t ask her what she studied. But do talk to her about who you are, what you love, what’s been perplexing or troubling you! She derives joy and fulfillment from swimming and gymnastics, music, having real conversations, and simple, earnest service.

[1] 1 Corinthians 7:32-34 (ESV)

[2] Gerber, Jacob. “‘Undivided Devotion to the Lord’ (1 Corinthians 7:32–40).”

Harvest Community Church (PCA), October 27, 2019. https://harvestpca.org/sermons/ sermon-undivided-devotion-to-the-lord-1corinthians-732-40/.

[3] Ephesians 5:22-32

[4] “TGC Course: Introduction to Song of Solomon.” The Gospel Coalition. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.thegospelcoalition. org/course/song-of-solomon/.

[5] Harvey, James L. “Why Study the Book of Song of Solomon?” Crossway, June 8, 2018. https://www.crossway.org/articles/why-study-thebook-of-song-of-solomon/.

[6] Mishnah Yadayim 3:5

[7] Song of Songs 5:9

[8] Song of Songs 5:10-13

[9] Shanks, Andrew. “What’s the Difference between Erotica and Song of Solomon?”

The Gospel Coalition, May 15, 2013. https:// www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/whatsthe-difference-between-erotica-and-song-ofsolomon/.

[10] Song of Songs 8:6

[11] 1 John 4

[12] Song of Songs 8:4

[13] James 1:14-15

[14] 1 Kings 4:29-31

[15] Luther, Martin. Martin Luther’s Small and Large Catechisms. Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2019.

[16] Psalm 139:13

[17] Ben Hutton, “Made His Own” (message to Cru Cornell, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, April 21, 2023).

[18] Romans 11:33

[19] Tappert, T. G. The Book of Concord: The Confessions of the Evangelical Lutheran Church. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1959.

[20] Proverbs 31:30

[21] Henry, Matthew. 1706. Matthew Henry Commentary on the Whole Bible (Complete). Vol. 1. N.p. https://www.biblegateway.com/ resources/matthew-henry/Song.5.9-Song.5.16.

[22] Philippians 2:3-4

[23] Philippians 1:9-11

[24] 1 John 4:19

[25] Song of Songs 5:16

We weren’t perfect You know, I’ll admit it Yet, somehow, we were always smiling Always holding each other in prayer

Together, I spent many of my firsts: My first birthday, my first concert

My first beach trips, and my first graduation

But then, that all came crashing down

At the end of a twelve hour shift

During a car ride ‘crosstown

And I don’t believe it, I can’t Your silence pierces my ears Your actions cloud my mind

I’m nauseous just trying to find a way out

But then I saw your car drive by And you didn’t stop

So I thought, can I be the one who is wrong?

I talk to myself, time and time again

And still, nothing makes sense

But it happened, what shouldn’t have happened

So I no longer expect anything from you For my patience for you has run out And my mind borders on insanity

Yet, in the confusion, I wonder

I wonder if I ever truly meant something to you

If I ever meant what you led me to believe And if so, why you hurt me this way?

I followed your words without objections All I ever did was for our sake, its true And never had I doubted your directions I guess I truly loved you

Yet, the little voice in my head was right When it warned against you That you would only be a mistake But I believed you were the exception And turns out, you are worse than that

You’re convinced this between us love, but it isn’t Your words were full of selfish commands and no understanding But I didn’t notice

I didn’t notice the meaning behind your surprise coffee Sunday mornings, Didn’t notice the timeliness of your more frequent visits, Or of your sudden disappearances And now, of your unannounced questions

I’m determined to move on, but it seems you aren’t but don’t worry If you don’t know, I can teach you

I erased our pictures, threw away your gifts Stopped reading my Bible, and threw away our notes Deleted our songs, and threw away our movies Erasing every trace of you

Because after all, it was right The voice in my head

When it said that you would only be a mistake

I wonder what has become of you I heard it’s not working, you and your new love How funny

My arms froze when you ran to theirs It wasn’t until then that I understood what role I played That we only loved each other when it fit best

Even though I still wish to forget you Truthfully, I haven’t

The memories are very much alive

I hate the songs we used to sing I hate your reassuring I love you’s I hate your gentle eyes and soothing voice But that isn’t what I hate the most

I hate how badly you define love

I hate that you only drove by and never dared to say goodbye

I hate that your memories still haunt my present But what I hate the most is that I don’t hate you

I never thought it possible That I’ll become hollow

That I’ll despise the things I once loved Nor that this would be thanks to you

I don’t like to hate, it’s exhausting But you’ve earned it and force me And yet, what I hate the most is that I don’t hate you Even now, I love you, although differently If I didn’t, I wouldn’t be here And if I put up with you, it’s because at times I was happy too

I love the firsts we shared I love you even if you didn’t say goodbye And I love that you still ask for me Sunday nights

Isn’t it funny, though? How you now come to me And you come with your heart in pieces

It could have been me

Who still cared for your heart

But you cruelly turned away And stabbed mine

Don’t get me wrong, we’ll never be the family we were We can only cherish it

Yet, in the midst of all, I am left with one disgrace: To miss what didn’t happen And like an idiot, I still do

When I first arrived at Cornell for freshman move-in, I remember being struck by my dorm’s floor-to-ceiling windows and motion sensing light fixtures. The paint still smelled fresh.

I was one of the lucky ones, I thought— assigned to a brand new dorm. The North Campus Residential Expansion was finally complete, ready to welcome the class of ’26 and to foster a “cohesive community.” [1] My neighbors would be from all over the world. I was ecstatic.

While I unpacked, my suitemate Emily* knocked on my door to introduce herself. Her roommate Angie* followed, clad in Cornell gear and a sincere smile. Standing on the patch of patterned carpet between our half decorated rooms, we excitedly shared our hometowns and majors—answering all the typical orientation week questions.

Yet, following our first interaction, a blurry whirlwind ensued. In the busyness of determining the fastest walk to Morrison, donning shower shoes, reading syllabi, and learning the ropes of the TCAT bus system, I ceased to see Emily and Angie, save for the occasional moments we’d cross paths, extending small smiles.

As time passed and sunsets came sooner, we slipped into an awkward two-step. Encountering each other in our hotel-like hallway, we’d pull out our phones to avoid eye contact. At night, we’d brush our teeth standing next to each other in heavy silence. It became our convention.

But Social Isolation,” an article from The Cornell Sun headlined in the fall. [2] When I reflected on my own freshman dorm experience, this statement didn’t feel too disparate from reality. Residents kept their doors closed. My relationship with my suitemates—a once promising flame—had extinguished.

I knew it was my responsibility in part. But I was busy. During my first weeks at Cornell, I reveled in the newfound freedom of building my schedule entirely around myself, color coding squares of time onto my Google Calendar.

Cornell’s ecosystem is uniquely designed for ambitious students: Convention on campus is to accomplish great things for our respective selves. We pack our schedules full of boxes to check off. Yet, in our culture of self-ambition, saturated with the words “self improvement” and “self realization,” we must not miss the very word of God. The second greatest commandment—which follows only loving God with all of our hearts, souls, minds, and strength—reads:

“Love your neighbor as yourself.”

[3] It echoes. “As yourself.” This commandment is meant to set the foundation for how we live. Through orienting ourselves towards it and the first, all other subsequent commandments are fulfilled. So often, however, I race through my day, never taking in the myriad faces of Cornell, never wondering how I can better love each one. I extend apathy to the residents in my dorm—my physical neighbors.

I reveled in the newfound freedom of building my schedule entirely around myself, color coding squares of time onto my Google Calendar.

The Gospel of Luke recounts a man well acquainted with Jewish law asking Jesus, “And who is my neighbor?” Jesus replies by sharing the Parable of the Good Samaritan:

During a time of strong hostility between the Israelites and the Samaritans—two neighboring tribes animus toward each other because of religious difference— an Israelite fell among robbers along his

journey from Jerusalem to Jericho. He was stripped, beaten, and left half dead. While he lay wounded, a priest and a

Levite walked along the road without stopping, denying aid to their fellow Israelite. Only did a Samaritan, the expected enemy, have compassion. He bound up the man’s wounds, poured out his expensive oils and wine, and carried the man to an inn on his own donkey.

This Samaritan, who reached across lines of social class, religious division, and deep-seated antipathy to demonstrate unexpected love and mercy, proved to be a neighbor, Jesus revealed. [4]

I, on the other hand, realized I had not.

Jesus described in the story of the Good Samaritan.

Repeatedly throughout the Bible, God characterizes love as a radical departure from expectation. In the Gospel of John, Jesus is depicted washing His disciples’ feet. The all-powerful Creator lowers Himself to His knees. A humble God is almost paradoxical. Understandably confused, Simon Peter, one of Jesus’ disciples asks, “Lord, are you going to wash my feet?” Jesus replies, “You do not realize now what I am doing, but later you will understand.” [5]

Today, with the image of Christ’s broken body on the cross, we can understand. The love God lavishes on us is nothing we could ever earn or afford. Yet He humbled Himself to take on human flesh, exemplifying a servant’s love for the sake of our salvation. [6] In our broken nature, we need Him to wash our feet to enter a relationship with Him and be freed from our bondage to sin.

True neighborly love, as it’s biblically characterized, transcends a doormat inscribed “Welcome!” It surpasses Mr. Rogers’ neighborly friendliness [7]. It breaks with convention. The Good Samaritan, who would have been expected to revel in the beaten Israelite’s brokenness, had compassion. When God washes His disciples’ feet, He stumps Peter, one of His closest followers. This picture of love, as God paints it, should serve as a stark example for how we ought to live today.

True neighborly love, as it’s biblically characterized, transcends a doormat inscribed “Welcome!”

to my suitemates about grabbing a meal together. Sitting beneath Appel’s warm ceiling light, slices of sheet pizza between us, my roommate and I conversed with Emily and Angie for the first time in months. Our talk was small, but refreshing. A minor shift occurred. When we returned to our dorm, our subsequent interactions were characterized by rekindled friendship.

Today, on a larger scale, relationships seek rectification. The faces we might pass on our rush to class long to be seen. Cornell’s 2021 Undergraduate Experience Survey reports 22.9% of respondents disagreeing with the statement “I’ve found a community where I feel I belong.” [8] Furthermore, Gen. Z is described as the “loneliest generation.” A survey from Cigna reports individuals aged 18-22 scoring high on the UCLA loneliness scale. [9] Initiatives on campus like Anabel’s Grocery and the Basic Needs Coalition care for our immediate neighbors with essentials such as food, housing, health, and finances. [10] Yet, despite these inspiring initiatives, a deeper need remains. Loneliness is still experienced in crowded rooms; brokenness still hides behind closed doors. With such need, it merits asking: Are you loving like the Good Samaritan?

The faces we might pass on our rush to class long to be seen.

Beyond neglecting friendships with those in my dorm, I had watched sour cream slip off my plate at Okenshields, leaving the task of cleaning it up for the dining hall staff. I’d sped past acquaintances on my walk to class without saying, “Hi.” My way of loving was far from the extraordinary love

My shiny new dorm had become a place for little more than switching off my bedroom light within good comfort. It seemed acceptable. I could go a whole semester not once conversing with my suitemates. But it no longer sat right with me.

Freshly convicted, I stepped outside of my own comfort and reached out

C.S Lewis writes “To love at all is to be vulnerable.” [11] Slowing down to strike up a conversation with a dining hall employee might require initial discomfort. Loving is not always easy or free. It may come at the expense of a shattered heart. But in experiencing the abundance of God’s inconceivable love, what overflows empowers us to love unabashedly. This bold love can bring to life what was dormant, like Ho Plaza’s cherry blossoms in springtime. It can reignite flickering flames of friendship.

If we are to truly love our neighbors as

ourselves, we are to love across social barriers, outside of expectation, and beyond what is often convenient— clearing our calendars for a hurting friend, breaching silence with a kindhearted “hello,” and not taking acquaintances for granted, whatever barriers in our way.

*=Pseudonyms

[1] “The North Campus Residential Expansion.” Student and Campus Life, n.d. https://ncre. cornell.edu/.

[2] “Similar to Last Year, New North Campus Dorms Provide Luxury But Social Isolation” The Cornell Sun, 2022

[3] Mark 12:30-31 NIV

[4] Luke 10:25-37 ESV

[5] John 13:3-8 NIV

[6] John 3:16 ESV

[7] “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” Song Lyrics, Fred Rogers, 1967

[8] 2021 Cornell Undergraduate Experience Survey, pg. 142

[9] 2018 Cigna U.S Survey of 20,000 Americans on loneliness

[10] Basic Needs Coalition / Anabel’s Grocery Website

[11] C.S. Lewis, The Four Loves, 1960

Annina is a first-year studying Government and French from Boise, ID. Any time you might find her audibly obsessing over spring foliage, reviewing food, making aesthetic Spotify playlists, or studying outside if it’s above freezing. She also commonly publicizes that Idaho is more than just the potato state.

In experiencing the abundance of God’s inconceivable love, what overflows empowers us to love unabashedly.

Michelle Liu

Michelle Liu

flew to another city to win over a crush of mine. One week and $300 later, I flew home in the friend zone, lamenting my decisions and rethinking my life. My mind flashed to Paul’s admonition in 1 Corinthians: “Now to the unmarried and the widows I say: It is good for them to stay unmarried, as I do. But if they cannot control themselves, they should marry, for it is better to marry than to burn with passion.” [1] Perhaps, it would be better for me to stay single forever, like Paul. I would save so much time and heartache. I could have donated that $300 to a charity or my church instead of indulging in a fruitless romantic pursuit. When I went to my dad with my heartbreaking news, he had the nerve to rub salt in my open wound by proposing that he arrange a marriage for me (because even he could see that I was hopeless).

He might have had a point. Wouldn’t it be easier if my parents just chose someone for me? Since I clearly “burn with passion,” it would be a win-win! During my era of singleness, I could harness my burning passion toward a more productive avenue, such as my