W ESTERN M ICHIGAN U NIVERSITY C OOLEY L AW R EVIEW

Volume 38 Spring 2023

Articles

Issue 1

A Step in the Right Direction: The H-1B Program is Finding a New Light

Maria J. Pierre

Justice Affordable to All: A Comparison of Bail Reform Across America

Riley Stheiner

Memory: The Past, Present & Future of Law School Exams

Matthew Marin & Amanda Fisher

Reading Between the Wines: Granholm v. Heald’s Implications for Other Industries

Tyler R. Smotherman

Distinguished Briefs

Rouch World, LLC & Uprooted Electrolysis, LLC v. Michigan Department of Civil Rights & Director of the Department of Civil Rights

Tonya Celeste Jeter

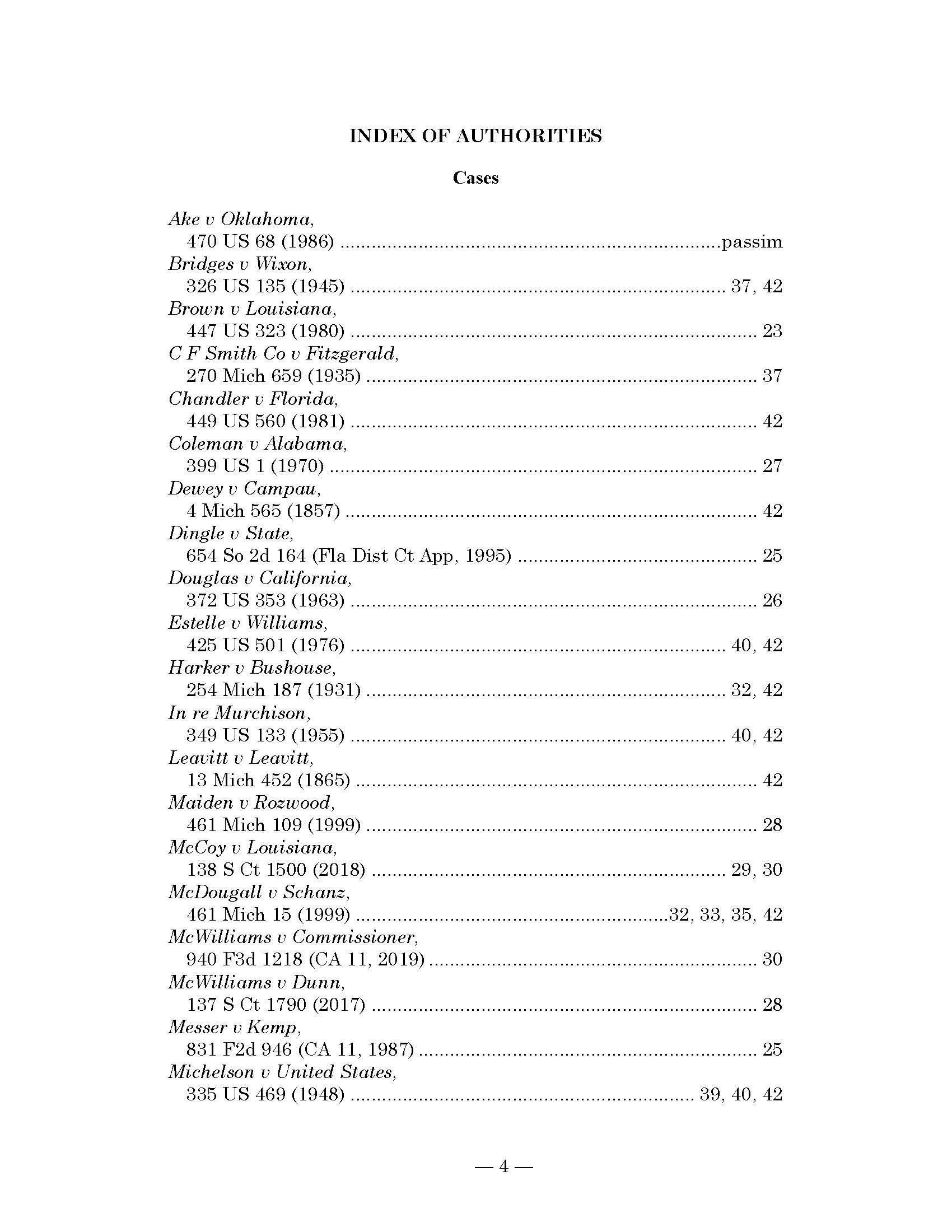

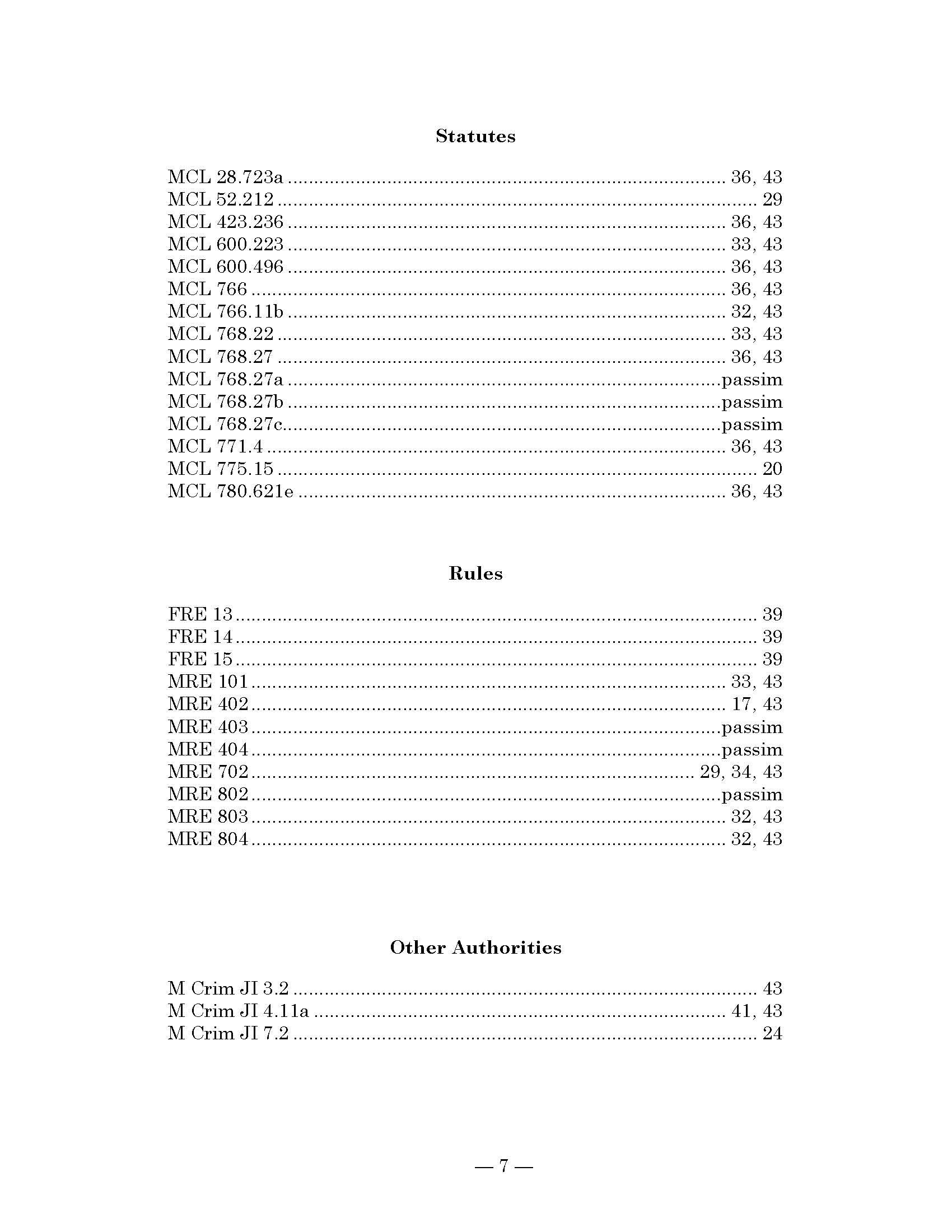

People of the State of Michigan v. Robert Lance Propp

Steven Helton

A Publication of Western Michigan University

Thomas M. Cooley Law S chool

I

Cite this volume as: 38 W. MICH. U. T.M. COOLEY L. REV. (2023). The Western Michigan University Thomas M. Cooley Law Review is published three times annually by the students of the Western Michigan University Thomas M. Cooley Law School, 300 South Capitol Avenue, P.O. Box 13038, Lansing, Michigan 48901.

Subscriptions: Special Patrons, $50 per year; Law Firm Benefactors, $100 per year; regular subscriptions, $30 per year. Inquiries and changes of address may be directed to the Law Review, care of the Western Michigan University Thomas M. Cooley Law School, phone number 1 (517) 371-5140, ext. 4501.

The Western Michigan University Thomas M. Cooley Law Review welcomes submission of articles. Manuscripts should be typed, double-spaced, with footnotes. Citations in manuscripts should follow the form prescribed in The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation (19th or 20th Ed.). We regret that unsolicited manuscripts cannot be returned. E-mail to LawReview@cooley.edu in Microsoft Word format.

Editorial Policy: The views expressed in papers published herein are to be attributed to their authors and not to the Western Michigan University Thomas M. Cooley Law Review, its editors, or the Western Michigan University Thomas M. Cooley Law School.

The Western Michigan University Thomas M. Cooley Law Review is a member of the National Conference of Law Reviews. Printed by The Sheridan Press, 450 Fame Ave., Hanover, Pennsylvania 17331. Nonprofit postage prepaid at Lansing, Michigan, and at additional offices.

Back issues and volumes, as well as complete sets, are available from William S. Hein & Co., Inc., 1285 Main Street, Buffalo, New York 14209, phone number 1 (800) 828-7571.

Printed on recycled paper.

Copyright 2023 by Western Michigan University Thomas M. Cooley Law School.

W ESTERN M ICHIGAN U NIVERSITY THOMAS M. COOLEY LAW SCHOOL

James McGrath, President & Dean

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Hon. Louise Alderson, Chairman

Aaron V. Burrell

Thomas W. Cranmer

Hon. Michael P. Hatty

Kenneth V. Miller

Hon. Bart Stupak

Mitchell S. Zajac

Mustafa Ameen

Christina Corl

John M. Dunn

Hon. Jane Markey

Lawrence P. Nolan

Jordan V. Sutton

PROFESSOR, FOUNDER, AND PAST PRESIDENT

The Honorable Thomas E. Brennan (deceased)

DEANS EMERITI

Michael P. Cox, Dean and Distinguished Professor Emeritus

Keith J. Hey, Dean and Distinguished Professor Emeritus

Robert E. Krinock, Dean and Professor Emeritus (deceased)

Don LeDuc, Dean Emeriti

DISTINGUISHED PROFESSORS EMERITI

Frank Aiello

David Berry (deceased)

Jeanette Buttrey

Terrence Cavanaugh

Julie Clement

Mary D’Isa

Cynthia Faulkner

Gary Bauer

Ronald Bretz

Evelyn Calogero

Karen Chadwick

Pat Corbett

Mark Dotson

Norman Fell

Curt Benson

Kathleen Butler

Paul Carrier

Dennis Cichon

David Cotter

Heather Dunbar

Gerald Fisher

Hon. Anthony Flores Judith Frank (deceased) Marjorie Gell

Elliot Glicksman (deceased) Lisa Halushka

James Hicks

John Kane

Mara Kent

Gerald MacDonald

Jeffrey L. Martlew

Nelson Miller

Lawrence Morgan

Kimberly O’Leary

Emily Horvath

Eileen Kavanagh

R. Joseph Kimble

Dena Marks

Dan McNeal

Ann Miller Wood

Maurice Munroe

Charles Palmer

James Peden Ernest Phillips

John Rooney (deceased)

Devin Schindler

Chris Shafer

Brent Simmons

Lauren Rousseau

John Scott

Dan Sheaffer

Paul Sorenson

John Taylor Gina Torielli

Gerald Tschura

Victoria Vuletich

Christopher Hastings

Peter Jason (deceased)

Peter Kempel (deceased)

Dorean Koenig (deceased)

John Marks

Helen Mickens

Marla Mitchell-Cichon

John Nussbaumer

Nora Pasman-Green

Philip Prygoski (deceased)

Marjorie Russell

Charles Senger

Jane Siegel

Norman Stockmeyer

Ronald Trosty

William Wagner

i

Cynthia Ward

Nancy Wonch

William Weiner

PROFESSORS EMERITI

F. Georgeann Wing

Sherry Batzer

Heather Garretson

Paul Marineau

Florise Neville-Ewell

James Carey

Lewis Langham

Donna McKneelen

Norman Plate

Dan Ray Kevin Scott

David Tarrien L. Patricia Thorpe-Mock

DEANS

Lisa DeMoss

Ashley Lowe

Monica Navarro

Toree Randall

Ronald Sutton

Karen Truszkowski

Tracey Brame

Associate Dean of Experiential Learning and Practice Preparation & Director of the Innocence Project & Professor

Danielle Hall

Associate Dean for Admissions, Financial Aid & Registration

Amy Timmer

Associate Dean of Students and Acting Dean of Graduate Programs

Katherine Gustafson

Assistant Dean of the Tampa Bay Campus & Associate Professor

Duane A. Strojny

Associate Dean for Library and Instructional Support & Professor

Paul J. Zelenski

Senior Vice President and Associate Dean of Enrollment & Student Services

PROFESSORS

Tammy Asher

Brendan Beery

Bradley Charles Mark Cooney

Renalia DuBose

Joseline Hardrick

Emily Horvath

Tonya Krause-Phelan

Michael McDaniel

Matthew Marin

David Finnegan

Richard C. Henke

Barbara Kalinowski

Mable Martin-Scott

Michael K. Molitor

Florise Neville-Ewell

Jeffrey Swartz Patrick Tolan

Christine Zellar-Church

ADJUNCT PROFESSORS

Erika Breitfeld

Mark Dotson

Dustin Foster

James Hicks

Linda Kisabeth

Daniel Matthews

Martha Moore

Monica Nuckolls

Joan Vestrand

Wafa Adib-Lobo

James Anderton V

Patrick Batterson

Michael Behan

Joseph Burgess

Terrence Cavanaugh

Patrick Corbett

Rich DiGiacomo

Chad Engelhardt

Giuliana Allevato

Andrew Arena

Sherry Batzer

Sonya Beverly

Daniel Cardwell

Steve Cernak

Debbie Crockett

Michelle Donovan

Steven Fantetti

Hon. Tony Flores Hon. Richard Garcia

Hon. Jack Gilbreath

Nathan Goetting

Mustafa Ameenuddin

Amy Bandow

Gary Bauer

Mark Brewer

James Carey

Russel Church

Elizabeth Devolder

Steve Dulan

William Fleener

Laura Genovich

Christi Henke

ii

Robert Heitmeyer

Daniel Houlf

Caroline Johnson-Levine

Lewis Langham

Peggy MacDougall

Daryl Manning

Holly Hicks

Hon. Curtis Ivy

Sheila Lake

Michael Leffler

Colin Maguire

Paul Marineau

Hon. Catherine McEwen Scott Mertens

Christian Montesinos

Nicholas Nazaretian

Kimberly O’Leary

John Pierce

Toree Randall

Tami Salzbrenner

Joseph Shada

Samantha Sliney

John Taylor

Victor Veschio

Graham Ward

Julie Mullens

Bentley Nettles

Sarah Ostahowski

Karen Poole

Jennifer Rosa

Jalitza Serrano

Ben Shotten

James Sterken

David Tirella

James Vlasic

Deirdre White

Clarence Hollins

Julie Janeway

Salvatore LaMendola

Randall Leonard

Steven Mann

John McDaniel

Marla Mitchell-Cichon

Thomas Myers

John Nicolucci

Jennifer Paillon

Teri Quimby

Christopher Sabella

Traci Schenkel

Eric Skinner

Edward Sternisha

Gregory Ulrich

Sarah Walker

Zena Zumeta

iii

WESTERN MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY COOLEY LAW REVIEW TRINITY 2023

BOARD OF EDITORS

Adam Ostrander Editor-in-Chief

Michala Ringquist Executive Managing Editor

Sarah Tanner Interim Executive Managing Editor

Ethan Loch Executive Articles Editor

Hannah Murphy Executive Publicity Editor

Samantha Hulliberger Managing Articles Editor

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Elizabeth Zywicki

Zachary Walters

Melissa Bianchi

Cameron Wilson

Adam Kimball

Kristin Duffy

Francesca Camacho

Norelle Miranda

Maria Pierre Executive Symposium Editor

Wyatt Wells Interim Executive Symposium Editor

Hope Teachout Executive Notes Editor

Caroline Quandt Managing Notes Editor

Professor Mark Cooney Faculty Advisor

vii

DAWN C. BEACHNAU AWARD

This award is presented to the member of the Western Michigan University Cooley Law Review Voting Board of Editors who made the most significant contributions to the Law Review through leadership and dedication.

Trinity 2023 Recipient: Ethan Loch & Hope Teachout

JOHN D. VOELKER AWARD

This award is presented to the Senior Associate Editor of the Western Michigan University Cooley Law Review who made the most significant contributions to the publication of the Law Review.

Trinity 2023 Recipient: Melissa Bianchi

EUGENE KRASICKY AWARD

This award is presented to the Assistant Editor of the Western Michigan University Cooley Law Review who made the most significant contributions to the publication of the Law Review.

Trinity 2023 Recipient: Adam Kimball

viii

WESTERN MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY COOLEY LAW REVIEW

HILARY 2023

BOARD OF EDITORS

Nancy Zieah Editor-in-Chief

Adam Ostrander Interim Editor-in-Chief

Michala Ringquist Executive Managing Editor

Samira Montlouis Executive Articles Editor

Jessica Sivillo Executive Notes Editor

Hannah “Leah” Ortiz Executive Publicity Editor

Samantha Hulliberger Managing Articles Editor

Professor Mark Cooney Faculty Advisor

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Julia Card

Alexandra Calzaretta

Aniela Bosca

Elizabeth Zywicki

Zachary Walters

Melissa Bianchi

Tyrone Laury

Cameron Wilson

Maria Pierre Executive Symposium Editor

Ethan Loch Interim Executive Articles Editor

Hope Teachout Interim Executive Notes Editor

Hannah Murphy Interim Executive Publicity Editor

Ronja Lugo Akergren Managing Notes Editor

v

DAWN C. BEACHNAU AWARD

This award is presented to the member of the Western Michigan University Cooley Law Review Voting Board of Editors who made the most significant contributions to the Law Review through leadership and dedication.

Hilary 2023 Recipient: Michala Rinquist

JOHN D. VOELKER AWARD

This award is presented to the Senior Associate Editor of the Western Michigan University Cooley Law Review who made the most significant contributions to the publication of the Law Review.

Hilary 2023 Recipient: Julia Card

EUGENE KRASICKY AWARD

This award is presented to the Assistant Editor of the Western Michigan University Cooley Law Review who made the most significant contributions to the publication of the Law Review.

Hilary 2023 Recipient: Tyrone Laury

vi

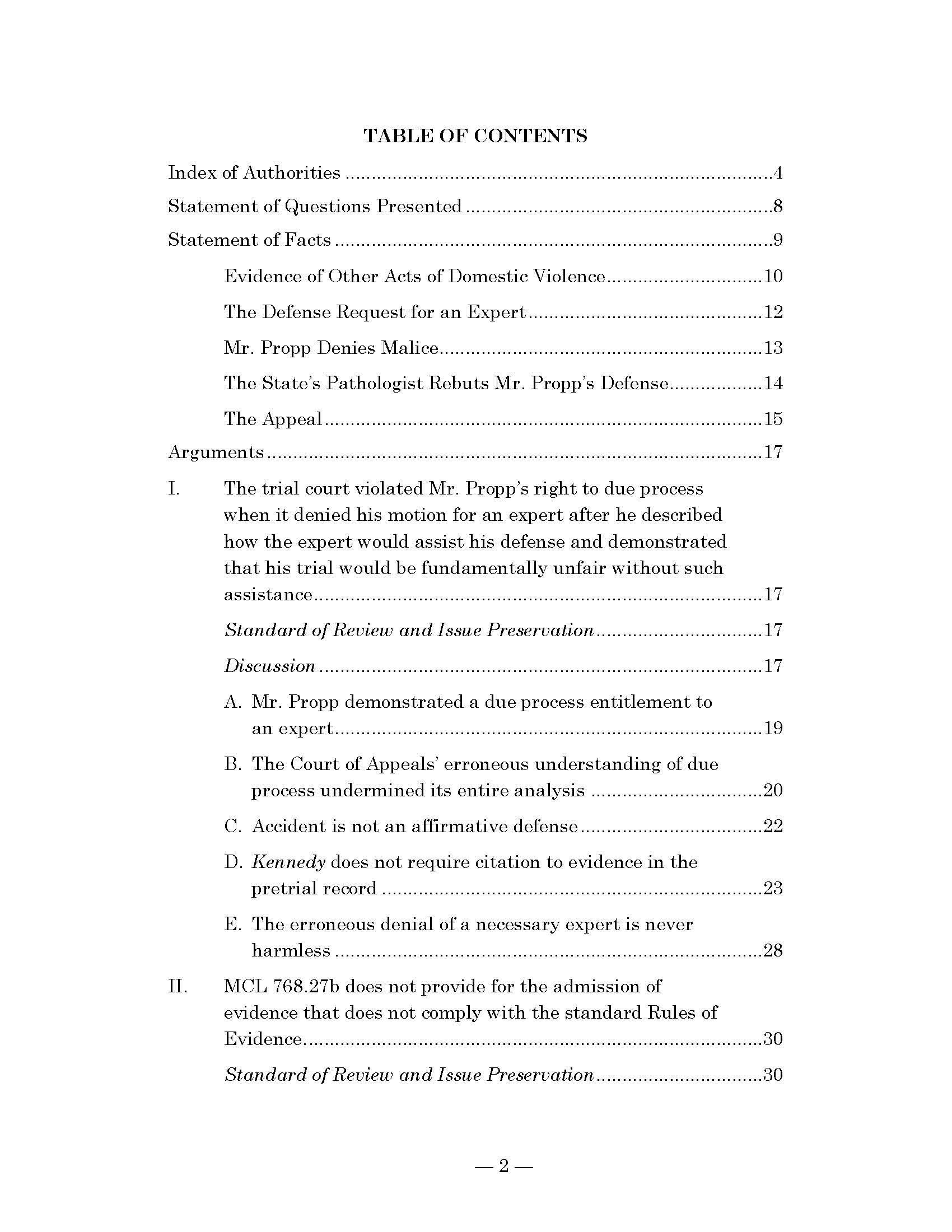

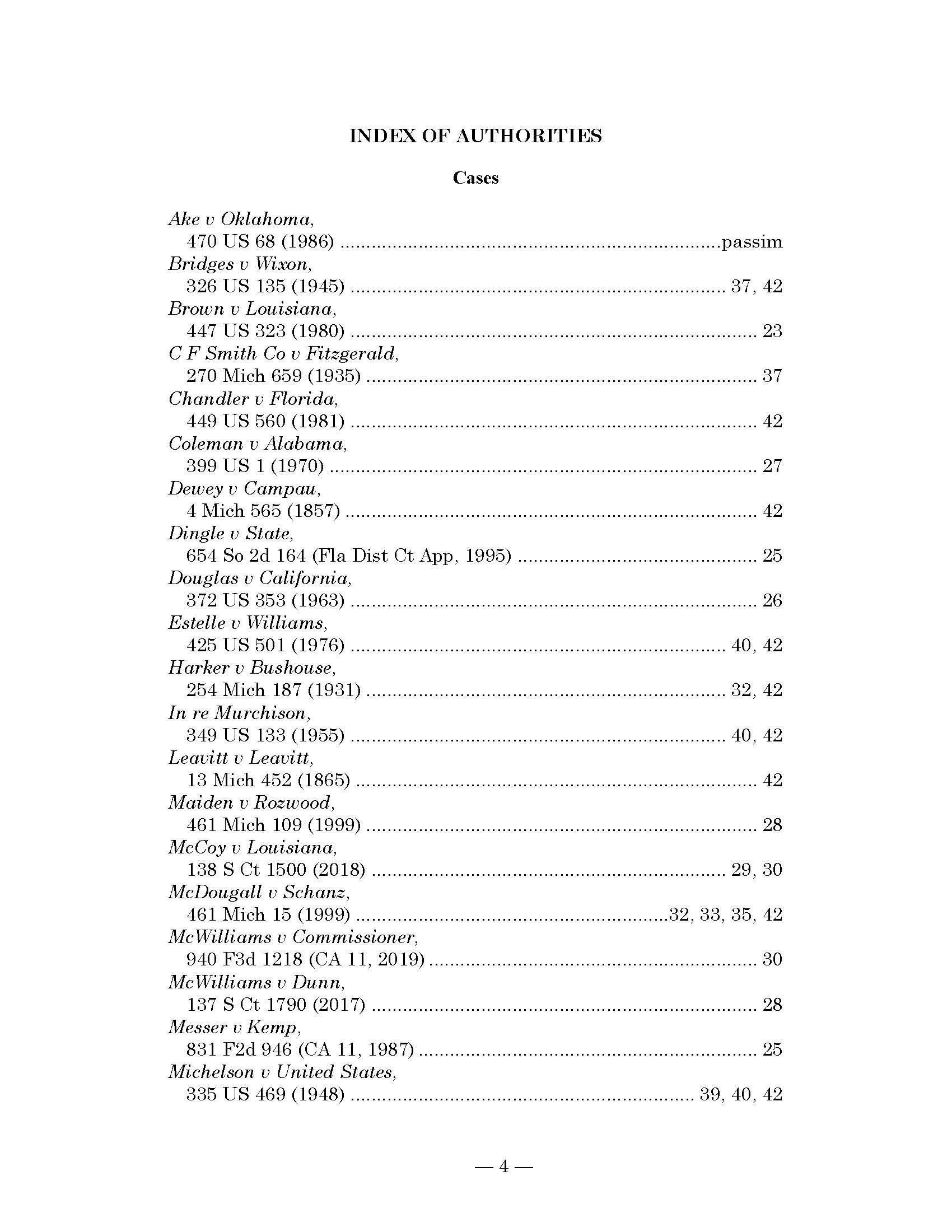

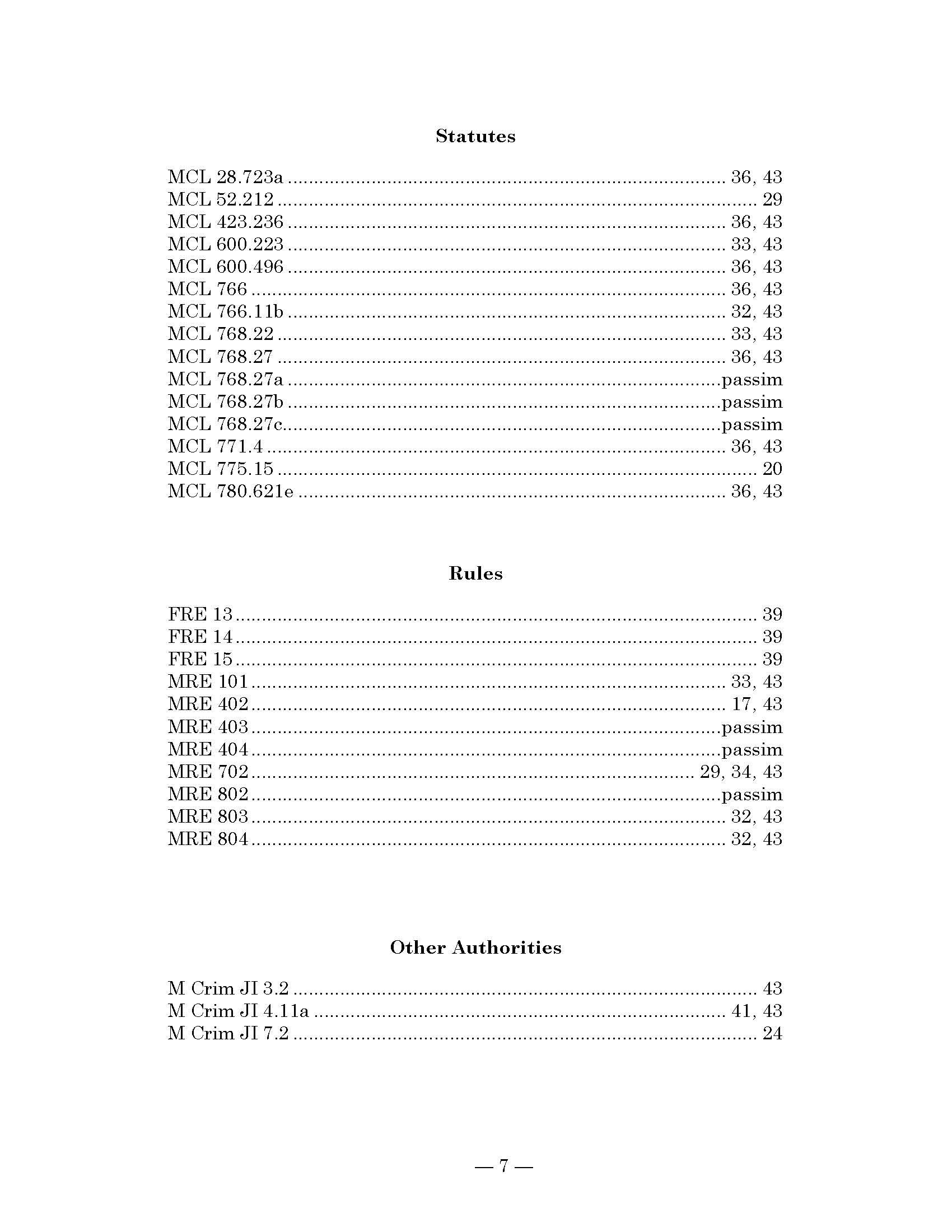

CONTENTS

From the Editor …………………………………………………………....xi

ARTICLES

A Step in the Right Direction: The H-1B Program is Finding a New Light

Maria J. Pierre…………………………………………………….1

Justice Affordable to All: A Comparison of Bail Reform Across America

Riley Stheiner……………………………………………………..13

Memory: The Past, Present & Future of Law School Exams

Matthew Marin & Amanda Fisher……………………………….29

Reading Between the Wines: Granholm v. Heald’s Implications for Other Industries

Tyler R. Smotherman……………………………………………..49

DISTINGUISHED BRIEFS

Rouch World, LLC & Uprooted Electrolysis, LLC v. Michigan Department of Civil Rights & Director of the Department of Civil Rights

Tonya Celeste Jeter…………………………………………....….75

People of the State of Michigan v. Robert Lance Propp

Steven Helton …………119

ix

Volume 38 Spring 2023 Issue 1

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

Dear Reader,

The Executive Board of Editors of the Western Michigan University Thomas M. Cooley Law School Law Review is proud to present to you the first issue of the 38th volume of our journal. The Board, myself in particular, would like to thank you for your support of this critical publication. Each member of the Cooley Law Review has dedicated untold hours to create this issue, and without your support, there is no reason for us to do what we do.

This issue contains an array of articles addressing some of the most pressing legal issues of our time. The first article addresses immigration in the United States and the state of the H-1B visa caps. The second article tackles equal and equitable bail bonds in our criminal justice system. The third article takes on the state of law school exams in a post-COVID world. And the fourth article addresses the impact of Granholm v. Heald on interstate commerce.

Additionally, this issue contains two award-winning briefs of the 2022 Distinguished Briefs Awards hosted by the Western Michigan University Thomas M. Cooley Law Review.

Many articles were submitted for consideration. These articles were chosen by the Law Review Board of Editors because they offered unique, insightful perspectives on their subject matter. As we have since our inception, several decades ago, we strive to bring exceptional, provocative perspectives to the table to further thoughtful discussion about the law. We are sure that is exactly what these articles will do. Thank you again for your continued support.

With Great Appreciation,

Adam N. Ostrander

xi

A STEP IN THE RIGHT DIRECTION: THE H-1B PROGRAM IS FINDING A NEW LIGHT

MARIA J. PIERRE1

I. INTRODUCTION

H-1B Cap. What else is there to say – if you know, you know. The H-1B program applies to employers who want to hire nonimmigrant foreign nationals in specialty occupations. A specialty occupation requires the applicant to have a bachelor’s degree (or equivalent) and highly specialized knowledge. The H-1B Cap process is applicable to foreign nationals who have not had H-1B visa status before

How does the process work for first-time H-1B visa holders? There is an annual cap of 65,000 for new H-1B visa holders, with an additional 20,000 for noncitizens with master’s degrees or higher from a U.S. institution. The H-1B visas are allocated during a certain time of the fiscal year by a randomized lottery system – this lottery system is referred to as the “H-1B Cap.” An H-1B Cap application is not considered to be selected if the randomized lottery does not select that H-1B Cap application.

The H-1B Cap process invokes an array of feelings; applicants commonly experience frustration, anxiety, and high stress levels. For instance, if the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (“USCIS”) did not select an individual’s H-1B Cap application, then all of one’s hard work, blood, sweat, and tears could be meaningless.

Gladly, the system is far removed from those dark days. In March 2020, the H-1B selection process stepped into the light by creating a registration system. This system helps cut out the tedious work on the

1. Maria J. Pierre received a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from the University of San Diego in 2011, completed her certified Paralegal certificate in 2013 from USD, and obtained her Master of Science in Law from Champlain College in 2017. Maria has worked in the Business Immigration field since 2013 and will continue to practice in this field of law after obtaining her Juris Doctorate in 2024. Maria is the Executive Symposium Editor of WMU Cooley Law Review, a member of the American Immigration Lawyers Association, a member of the Phi Alpha Delta Society of Scholars, and a member of Sigma Gamma Rho Sorority, Inc.

front end of the H-1B application process. Under the new system, a beneficiary is selected for the H-1B Cap, and then the individual prepares an H-1B Cap application. If the H-1B beneficiary is not selected, the individual will no longer waste time and resources while preparing for the case.

Emily C. Callan’s article, Is the Game Still Worth the Candle (or the Visa)? How the H-1B Visa Lottery Lawsuit Illustrates the Need for Immigration Reform, 2 provided alternative solutions for Congress and the USCIS to cure problems in the H-1B Cap process and the entire H-1B program. Since the article’s publication in 2016, President Joe Biden’s Administration has slightly improved this visa program. The Biden Administration offers solutions to help cure the “ills” Callan addressed in her article. Part II of this article provides an in-depth background of the H-1B program and the H-1B Cap registration system. Part III provides alternatives to Callan’s proposed “cures” to the H-1B program. Finally, Part IV states a conclusion.

II. BACKGROUND

A. Statutory Provisions

In 1952, the Immigration and Nationality Act (“INA”) “first established an H-1 nonimmigrant visa classification for temporary workers ‘of distinguished merit and ability.’”3 The Homeland Security Act of 2002 disbanded INA on March 1, 2003,4 and the newly-formed Department of Homeland Security (“DHS”) absorbed the constituent parts under three agencies: Customs and Border Protection (“CBP”), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (“ICE”), and USCIS to “retain[] its commitment to welcoming lawful

2 Emily C. Callan, Is the Game Still Worth the Candle (or the Visa): How the H-1B Visa Lottery Lawsuit Illustrates the Need for Immigration Reform, 80 ALB. L. REV. 335, 347 (2016).

3. RODNEY A. MALPERT, ET AL., BUSINESS IMMIGRATION LAW: STRATEGIES FOR EMPLOYING FOREIGN NATIONALS § 4.03 (2015).

4 USCIS, Overview of INS History, USCIS HIST. OFF. & LIBR., 11 (2012), https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/factsheets/INSHistory .pdf (last visited Aug. 1, 2022)

2 W. MICH. U. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 38:1

immigrants and supporting their integration and participation in American civic culture.”5

B. Regulations

The two U.S. Administrative agencies responsible for the H-1B Program are USCIS and the Department of Labor (“DOL”).6 “The USCIS authorizes actual H-1B classification for a particular foreign national beneficiary, based on a petition submitted by the employer[.]”7 The H-1B application describes the H-1B specialtyoccupation position that will be performed and the foreign national’s qualifications for the intended job.8 Before the H-1B application is submitted, whether the application is Cap or non-Cap, the “DOL reviews and certifies the employer’s labor condition application (‘LCA’).”9 The DOL certifies “the employer’s obligations regarding wages and working conditions” for the employment opportunity.10 These two agencies have “promulgated detailed regulations” regarding the H-1B application.11 For example, employers are not allowed to file “multiple H-1B petitions for the same employee,”12 and there is a “minimum five-day period at the beginning of the fiscal year’s filing ‘season’ during which H-1B petitions are received by USCIS.”13

C. The H-1B Cap Selection Process

The most recognized feature of the H-1B program is the H-1B Cap selection process. The H-1B Cap season is “[o]ne of the more widely known and frustrating features of the H-1B program[.]”14 It “is the annual numerical limit on usage of the H-1B category[.]”15

2023] FINDING A NEW LIGHT 3

5. Id. 6 Malpert, supra note 1, at 5 7 Id. 8 Id. 9 Id. 10 Id. 11. Id. 12 Id. at 7. 13 Id. 14 Id. 15 Id.

“The law specifies that foreign nationals who are subject to the limitation shall be issued visas or otherwise provided the status ‘in the order in which petitions are filed for them.’”16

USCIS begins accepting and processing H-1B petitions at the start of the filing period for a given year (April 1) and continues to accept and process petitions in chronological order of filing until it determines, using projections based on historical rates of approval, denial, and revocation, that enough petitions have been filed to ensure that the number of approved petitions for qualifying beneficiaries will meet the year’s cap.17

The H-1B application can be “filed up to six months [before] the requested start date.”18 This means the “filing period for each fiscal year actually starts the previous April 1, with petitions asking for October 1 start dates.”19 The H-1B Visa Reform Act of 2004 allows beneficiaries that hold “a master’s or higher degree from a U.S. institution” to be exempt from the 65,000 annual caps.20 These higher education beneficiaries have a separate annual cap limit of 20,000.21

Before 2020, employers were required to submit full H-1B applications before knowing “whether a visa number would be available, given that demand for visa numbers usually outstrips supply.”22 However, in March 2020, for the 2021 fiscal year, USCIS changed its registration process.23 A completed H-1B application was no longer required.24 “The purpose of this new process was to reduce the burden on U.S. employers, and the agency, caused by requiring employers to submit complete H-1B petitions and supporting documentation [before] knowing whether a visa number would even be available.”25 USCIS announces its next year’s dates in advance, “during which a U.S. employer must register electronically for each

16 Id. (quoting 8 U.S.C. § 1184(g)(3)).

17 Id. (quoting 8 C.F.R. §§ 214.2(h)(8)(ii)(A), 214.2(h)(8)(ii)(B)).

18. Id. (quoting 8 C.F.R. § 214.2(h)(9)(i)(B)).

19. Id.

20 Id. at 8 (quoting 8 U.S.C. § 1184(g)(5)(C)).

21 Id.

22

American Immigration Council, The H-1B Visa Program and its Impact on the U.S. Economy, AM. IMMIGR. COUNCIL 3 (Apr 2020), https://www.immigrationresearch.org/system/files/the_h-1b_visa_program_ a_primer_on_the_program_and_its_impact_on_jobs_wages_and_the_ economy.pdf (last visited Aug. 1, 2022).

23 Id.

24 Id.

25 Id. at 3-4.

4 W. MICH. U.

COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 38:1

foreign national for whom the employer intends to file an H-1B petition.”26

In contrast to the copious amount of information USCIS previously required, the electronic registration process now requires a U.S. employer to pay a $10 registration fee for each H-1B candidate, along with limited information about the petitioner and beneficiary.27 “If USCIS receives more registrations than visa numbers available,”28 a lottery occurs to select the registrants who can file full H-1B applications.29 “USCIS will select registrations for the 65,000 visa numbers first and then for the 20,000 master’s exemption visa numbers.”30

When the registrants are selected, the employers are electronically notified, and the employer then has 90 days to file an H-1B application.31 If the USCIS does not receive enough petitions to meet the visa numbers, “USCIS has the option to make additional selections.”32

III. ANALYSIS

A. Proposed Solution No.1: Congress Should Increase the H-1B Visas Numbers

In her article, Callan suggests that this solution is the “easiest legislative fix” to the H-1B paradox – “for Congress to simply increase the number of visas that may be issued each year.”33 This proposed solution has been pursued, and it is the cause for multiple bills proposed annually.34 Still, the Biden Administration will most likely not raise the H-1B Cap numbers.35

35. Patrick Thibodeau, Biden Wants Permanent Work Visas, Not More H-1Bs, TECHTARGET (Oct. 29, 2021), https://www.techtarget.com/ searchhrsoftware/news/252508840/Biden-wants-permanent-work-visas-notmore-H-1Bs (last visited Aug. 1, 2022)

2023] FINDING A NEW LIGHT 5

26 Id. at 4. 27. Id. at 3. 28. Id. at 4. 29 Id. 30 Id. 31 Id. 32 Id. 33. Callan, supra note 1, at 347. 34. Id.

If the Biden Administration will not increase the H-1B visa numbers, how does this solution help immigrants pursuing this nonimmigrant visa type? The answer lies in Employment-Based green cards. The Biden Administration is relaxing some of the stringent restrictions that the Trump Administration placed on businesses pursuing employment-based green cards.36 The Biden Administration is working with lawmakers to increase this green card category that would allow foreign nationals to remain and live in the U.S. permanently.37

Why are green cards preferred over H-1B visas? Foreign nationals who have obtained H-1B visas can work for up to six years without special permission, and only “[u]nder certain circumstances, USCIS may extend . . . authorization beyond the six-year limit.”38 In contrast, if a beneficiary’s employer does not opt-in for a green card, then the foreign national must leave the U.S., or scramble to find another favorable alternative to remain and continue to work in the United States.

However, a foreign national can find an employer to sponsor their green card and extend the six-year limitation for three more years if the foreign national has an approved I-140.39 The American Competitiveness in the 21st Century Act (“AC-21”) permits a foreign national to continue to extend their H-1B visa in one to three-year increments, depending on the status of their 1-140 petition.40 This extension can be continued until the foreign national’s priority date is current and their status is adjusted from H-1B visa holder to Lawful Permanent Resident–a non-citizen green card holder.41

38 USCIS, 6.5 H-1B Specialty Occupations, DEP’T OF HOMELAND SEC., https://www.uscis.gov/i-9-central/form-i-9-resources/handbook-foremployers-m-274/60-evidence-of-status-for-certain-categories/65-h-1bspecialty-occupations (last visited Aug. 1, 2022)

39 Kyle Knapp, How Long an H-1B Worker Can Stay in the United States, NOLO 2, https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/how-long-h-1bworker-can-stay-the-united-states.html (last visited Feb. 17, 2023).

40 H-1B Visa Extension, VISANATION, https://www.immi-usa.com/h1bvisa/h1b-visa-extension/ (last visited Feb. 17, 2023).

41. Dep’t Homeland Sec., Lawful Permanent Residents (LPR), DEP’T HOMELAND SEC., https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/lawfulpermanent-residents (last visited Aug. 01, 2022) See also 8 U.S.C. § 1184(g)(8)(C).

6 W. MICH.

U. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 38:1

36 Id. 37 Id.

The problem with Biden’s green card push is that getting a green card for some foreign nationals depends on their birth country. For a foreign national from any given country, there is a 7% limitation for green cards issued annually for that country.”42 For example, as of August 2022, USCIS is accepting Indian Nationals in the EB-2 category (members of the professions holding advanced degrees or persons of exceptional ability) to file their green card applications if they have a December 1, 2014, priority date.43

However, USCIS cannot review and adjudicate its applications if the foreign national’s priority date is before January 1, 2015.44 This means, for instance, that in 2022, an Indian National with a priority date of June 1, 2022, is not allowed to file their green card application until their priority date is “current;” the priority date will not be current for the next eight years, and that is if those dates do not retrogress.

Eight years is a generous estimate, and the more accurate estimate is closer to a decade or more for some countries. This is where AC-21 extensions can help Indian and Chinese Nationals remain in a prolonged H-1B visa status until they are permitted to apply for their green cards.45 This devastating news does not spread across the board. Foreign nationals from the Philippines, Mexico, and all other nationals have priority dates that are considered “current;” these nationals can file their green card applications shortly after receiving their I-140 approval notice, or they can file I-140 applications simultaneously with their green card applications.46

B. Proposed Solution No.2: Congress Should Create More Visa Categories

Callan suggests that “Congress should create more employment visa categories” that would “craft an entirely new temporary

42 Thibodeau, supra note 33

43 Dep’t of State–Bureau of Consular Affairs, Visa Bulletin: Immigrant Numbers for August 2022, DEP’T OF STATE 3-4, https://travel.state .gov/content/dam/visas/Bulletins/visabulletin_august2022.pdf (last visited Aug. 1, 2022).

44 Id. at 5.

45

6.5 H-1B Specialty Occupations, supra note 36

46 Visa Bulletin, supra note 41, at 4.

2023] FINDING A NEW LIGHT 7

employment visa category that foreign nationals could utilize [if] their H-1B petitions are not selected in the lottery.”47

Although the Biden-Harris Administration is not creating new employment visa categories, this Administration is expanding the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (“STEM”) fields to help attract “global talent to strengthen our economy and technological competitiveness, and benefit working people and communities all across the country.” 48 With this initiative, the DHS announced new actions to have more “predictability and clarity for pathways for international STEM scholars, students, researchers, and experts to contribute to innovation and job creation efforts across America.49 These actions will allow international STEM talent to continue to make meaningful contributions” to America.50 To list a few of the announcements:

1. Department of Homeland Security Secretary Mayorkas is announcing that 22 new fields of study are now included in the STEM Optional Practical Training (OPT) program through the Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP). The program permits F-1 students earning Bachelors, Masters, and Doctorates in certain STEM fields to remain in the United States for up to 36 months to complete Optional Practical Training after earning their degrees. . . . The added fields of study are primarily new multidisciplinary or emerging fields, and are critical in attracting talent to support U.S. economic growth and technological competitiveness.

2. DHS . . . update[d] its policy manual related to “extraordinary ability” (O-1A) nonimmigrant status regarding what evidence may satisfy the O-1A evidentiary criteria. . . . [This] status is available to persons of extraordinary ability in . . . science, business, education, or athletics. . . . DHS is clarifying how it determines eligibility for immigrants of exceptional abilities, such as PHD holders, in the (STEM) fields.

47 Callan, supra note 32, at 347.

48 FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Actions to Attract STEM Talent and Strengthen our Economy and Competitiveness, THE WHITE HOUSE (Jan 21, 2022), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room /statements-releases/2022/01/21/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administrationactions-to-attract-stem-talent-and-strengthen-our-economy-andcompetitiveness/ (last visited Aug. 1, 2022)

49 Id

50 Id.

8 W. MICH.

U. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 38:1

3. With respect to immigration, DHS is issuing an update to its policy manual on how U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), a DHS component, adjudicates national interest waivers for certain immigrants with exceptional abilities in their field of work. The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) provides that an employer can file an immigrant petition for a person of exceptional ability or a member of the professions with an advanced degree. . . .USCIS may waive a job offer requirement, allowing immigrants whose work is in the national interest to petition for themselves, without an employer.51

The above announcements are designed to remove some of the barriers placed on the legal immigration system.52 Although these STEM programs do not create new H-1B Employment Visa categories, they do lessen the previously stringent requirements that once made qualifying for these categories more challenging and contribute to the feasibility of obtaining a green card.

C. Proposed Solution No.3: USCIS Should Implement and Adhere to New and Existing H-1B Regulations

USCIS is not empowered to make new laws, as this authority is reserved solely for Congress.53 Nonetheless, the agency is authorized to promulgate its own regulations to execute its duties.54 The USCIS regulations have been made law frequently.55

Callan implies that USCIS does not follow its revoking mandate.56 When an approved H-1B application is not used, the petitioner is supposed to notify the Service Center Director about the unused H-1B application.57 At that point, the application is considered revoked; USCIS is to tally the number of unused H-1B applications and take into account the number of unused petitions for

51. Id.

52 Id.

53 See, e.g., 8 C.F.R. § 2.1 (2016) (stating that the Secretary of Homeland Security may delegate the authority to any employee of the DHS–including USCIS employees–to create regulations to administer and enforce immigration laws).

54. Id.

55 Legislation, USCIS, https://www.uscis.gov/laws-and-policy/legislation (last updated July 9, 2020).

56 Callan, supra note 32, at 349.

57 See, 8 C.F.R. § 214.2(h)(8)(ii)(B).

2023] FINDING A NEW LIGHT 9

the next fiscal year.58 “By its own admission, USCIS does not adhere to this regulation because the agency ‘allegedly’ takes into account these potential scenarios. . . when conducting the initial lottery.”59 However, there is no way for USCIS to accurately predict how many approved petitions will go unused;60 the agency has no empirical method to ensure that it accepts enough petitions to fulfill the Cap.61

Callan also proposed creating more new categories – preferential categories – that would result in more available H-1B visa numbers.62 This was done for Chilean and Singaporean foreign nationals by creating the H-1B1 category.63 The H-1B1 Program allows employers to temporarily employ foreign workers from Chile and Singapore in the U.S. on a nonimmigrant basis in specialty occupations.64 Current laws limit the annual number of qualifying foreign workers who may be issued an H-1B1 visa to 6,800, with 1,400 from Chile and 5,400 from Singapore.65 A similar visa category was created for the Australian National – the E3 Visa Category.66 This visa category bypasses the H-1B visa category and allows an annual 10,500 visas for Australian Nationals.67

58 Id.

59 Callan, supra note 32, at 349.

60 Off of Inspector Gen , USCIS Approval of H-1B Petitions Exceeded 65,000 Cap in Fiscal Year 2005, DEP’T HOMELAND SEC 5 (Sept 2005), https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/library/P34.pdf

61. Id.

62. Callan, supra note 32, at 350.

63 Dep’t of Lab., H-1B, H-1B1 and E-3 Specialty (Professional) Workers, EMP. & TRAINING ADMIN. (ETA), https://www.dol.gov/agencies/eta /foreign-labor/programs/h-1b (last visited Aug. 1, 2022)

64 Id.

65 Id.

66. USCIS, E-3 Specialty Occupation Workers from Australia, DEP’T HOMELAND SEC. (last updated May 4, 2022), https://www.uscis.gov /working-in-the-united-states/temporary-workers/e-3-specialty-occupationworkers-from-australia.

67 Dep’t of Lab., supra note 60

10 W. MICH. U.

COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 38:1

The Biden Administration, however, does not want to create new H-1B categories. Instead, the Administration wants foreign nationals to bypass the H-1B visa category; Biden’s new policies encourage foreign nationals to apply directly for their green card. With a green card, six-year limitations on how long a foreign national can remain in the United States do not exist.68 Also, there are no limitations on foreign nationals traveling while their green cards are processed, which is an abandonment of a visa applicant’s status.69

To help speed up the adjudication process of pending green cards, on February 18, 2022, USCIS encouraged applicants to change the underlying basis of their green card applications to the first or second employment-based categories.70 This is encouraged because, statutorily, visas cannot be made available to applicants who are in the third employment-based category.71 The green card alternative does not directly address the H-1B visa numbers, nor does it address the issue of USCIS not adhering to its own provisions. It does, however, speak to the Biden administration’s future vision to move away from the H-1B visa category completely.

Biden’s proposed green card alternative appears to be a wonderful substitute for the H-1B program. Still, it comes with its own series of problems, such as the availability of a given country’s allowed visas, priority dates, and the excessively long wait times for some countries such as China and India. It is a step in the right direction. If more applicants can qualify for green cards, then more applicants can bypass the H-1B program. This, in turn, will help prevent the allotted H-1B visa numbers from depleting and allow those who do not qualify for the first and second employment-based green card categories an opportunity to receive an H-1B visa until they can adjust their status and obtain a green card. Hopefully, as the Biden Administration continues, it will also continue to urge

68. USCIS, Green Card, DEP’T HOMELAND SEC., https://www.uscis.gov /green-card (last visited Feb. 17, 2022)

69 USCIS, Chapter 2 – Lawful Permanent Resident Admission for Naturalization, DEP’T HOMELAND SEC. Vol. 12, Part D, Ch. 2, § B. https://www.uscis.gov/policy-manual/volume-12-part-d-chapter-2 (last visited Aug. 1, 2022).

70. USCIS, USCIS Urges Eligible Applicants to Switch Employment-Based Categories, DEP’T HOMELAND SEC. (Feb. 18, 2002), https://www.uscis.gov/newsroom/alerts/uscis-urges-eligible-applicants-toswitch-employment-based-categories (last visited Aug. 1, 2022)

71 Id.

2023] FINDING A NEW LIGHT 11

Congress to create favorable immigration reform laws that will continue to help benefit our nation.

IV. CONCLUSION

The H-1B program will likely not achieve the coveted status of perfection anytime soon. At this point, it is a common fact that all presidential administrations have recognized the importance of the H1B category and how the H-1B category directly correlates to our nation’s economic growth and technological competitiveness. Although the government has not directly addressed Callan’s proposed alternatives, the Biden Administration has offered alternate solutions to bypass the H-1B program altogether by issuing green cards a step in the right direction.

12 W. MICH. U. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 38:1

JUSTICE AFFORDABLE TO ALL: A COMPARISON OF BAIL REFORM ACROSS AMERICA

RILEY STHEINER

I. INTRODUCTION

There are approximately 536,000 pretrial detainees, making up 70% of the United States jail population.1 Sixteen-year-old Kalief Browder was arrested after being accused of stealing a backpack.2 Browder’s family could not post his bail, which led to his three years of incarceration at Rikers Island without a trial.3 He maintained his innocence for the more than one thousand days he spent on Rikers Island while “waiting for a trial that never happened.”4 He attempted suicide several times while held in solitary confinement for two years.5 The case was eventually dropped, and Browder was released from incarceration.6 He tragically committed suicide in 2015 after battling mental health issues stemming from his long period of incarceration.7 Kalief Browder’s story and the psychological damage he sustained from his time in pretrial incarceration represents the negative effects sustained by defendants who cannot post bail.8 Americans are afforded the constitutional protection of innocence until proven guilty under the Fifth Amendment, “yet they will suffer the harms of incarceration unless they have enough money to pay

1. Adureh Onyekwere, How Cash Bail Works, BRENNAN CTR. FOR JUSTICE (Feb. 24, 2021), https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work /research-reports/how-cash-bail-works.

2 Id

3 Nicholas P. Johnson, Cash Rules Everything Around the Money Bail System: The Effect of Cash-Only Bail on Indigent Defendants in America’s Money Bail System, 36 BUFF. PUB. INT. L.J. 29, 30 (2017).

4 Jennifer Gonnerman, Kalief Browder 1993-2015, THE NEW YORKER (June 7, 2015), https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/kaliefbrowder-1993-2015.

5 Id.

6. David K. Li, Family of Kalief Browder, Young Man Who Killed Himself after Jail, Gets $3.3M from New York, NBC NEWS (Jan. 24, 2019), https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/family-kalief-browder -young-man-who-killed-himself-after-jail-n962466.

7 Id.

8 Onyekwere, supra note 1.

bail and buy their freedom.”9 In addition to being contradictory to constitutional rights, pretrial detention is counterproductive as it “coerc[es] people to forfeit their rights and plead guilty” to reduce their possible sentence.10 Additionally, “research shows[] the longer someone is held in pretrial detention, the more likely they are to be rearrested later.”11

Despite its effects, the purpose of money, or cash, bail is to release a defendant while guaranteeing that they will return to court for their future hearings or trial.12 If the defendant fails to appear at any required court appearances, the bail is forfeited to the government.13 In determining the amount of bail, judges have broad discretion to raise or lower the standard amount that is set for the alleged offense.14

It is clear and undisputed that the current system and utilization of pretrial detention is unfair and needs to change. While reform efforts have begun at both state and local levels, efforts have yet to be sparked in some regions. This comment will first discuss the history of the money bail process, early calls for reform, a comparison of reform as it has been implemented thus far, and each strategy’s possible success and failures.

II EMERGENCE OF THE CASH BOND SYSTEM

A right to bail was not included in the federal Constitution but was included in most state constitutions.15 Previous bail systems did not utilize a prepayment of bail, and instead, guarantees were paid only if a defendant defaulted by not attending their required court dates.16. As adopted from English law, the money for bail was provided by someone with whom the defendant had a personal

9. After Cash Bail: A Framework for Reimagining Pretrial Justice, THE BAIL PROJECT (last visited Dec. 4, 2021), https://bailproject.org/aftercash-bail/.

10 Id. 11 Id.

12 Onyekwere, supra note 1.

13 Id.

15. Alexa Van Brunt & Locke E. Bowman, Toward a Just Model of Pretrial Release: A History of Bail Reform and a Prescription for What’s Next, 108 J CRIM. L & CRIMINOLOGY 701, 712-13 (2018).

16 Id. at 713.

14 W. MICH. U. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 38:1

14. Id.

relationship and who ensured they returned to court.17 The use of “third-party assurance” continued to be a key part of the bail system in America as it evolved over time.18

In the nineteenth century, when the population of the United States began to disperse geographically, the nature of the bail system changed.19 Communities fractured as people moved away from their place of birth and families; this required defendants to pay their own bail bond.20 This led to a rising “commercial industry [which] allowed individuals to ‘bail out’ even if lacking a personal surety or the requisite funds.”21 However, these funds were not available without cost.

If a defendant is unable to pay their determined bail amount, they may use a private or commercial bail bond company, which “agree[s] to pay for a defendant’s bail obligation in exchange for a nonrefundable fee, called a bond premium, that may be anywhere from 10 to 15 percent of the bail amount.”22 The remainder of the fee can be secured through collateral, and if a defendant misses a court appearance, the bond company will use the collateral to recoup the full amount they were required to pay to the court.23

“Bail practices are frequently discriminatory, with Black and Latino men assessed higher bail amounts than white men for similar crimes by 35 and 19 percent on average, respectively.”24 Without the resources to pay bond premiums, defendants are forced to await their trial in jail.25 Defendants held in pretrial detention are four times more likely to be sentenced to prison than defendants released before trial.26 Those in pretrial detention are also more likely to make rushed decisions to reduce their time behind bars, including pleading guilty to a lower charge, “rather than chancing a higher charge and longer sentence.”27

Arthur L. Beeley published one of the first studies showing the injustices of the bond system; the study focused on the bail and

17

. Id. at 713-14.

18 Id. at 714.

19 Id. 20 Id. 21 Id. at 715.

2023] BAIL REFORM ACROSS AMERICA 15

Id. 24 Id.

Id. 26 Id. 27 Id.

22. Onyekwere, supra note 1. 23.

25

detention practices in Cook County, Illinois, in 1927.28 “Beeley found that most defendants remained in the Cook County Jail, not because they were considered any great flight risk, but because they could not afford bail.”29 While this study is almost 100 years old, Beeley’s “findings about the arbitrary imposition of pretrial detention and its negative effects on the poor were the same that spurred later bond projects and reform efforts.”30

III. INEQUALITY: THE DRIVE FOR REFORM

The bail system in America needs reform, and luckily, changes are already occurring. Illinois became the first state to end the cash bail practice entirely in February 2021.31 In 2017, New Jersey eliminated mandatory cash bail.32 Initiatives in specific cities, such as Philadelphia, have ended cash bail use for low-level offenders and allowed over 1,700 people awaiting trial to be released.33 There have been no negative impacts found on recidivism or courtroom appearances. In fact, Philadelphia’s First Judicial District has reported record-high appearance rates.34 “As we look to a future after cash bail, it is clear that transformational change will require a clear commitment to move past the incarceration paradigm and reimagine how society responds to poverty, mental illness, substance abuse, and violence.”35

When implemented effectively, bail reform allows defendants, who would otherwise show up to court and pose no risk to their community, to return to their families and work while awaiting trial.36 “Bail reform may reduce the concentrated costs the criminal justice system imposes on poor people and communities. . . and allow

28. Van Brunt & Bowman, supra note 15, at 717.

29 Id.

30 Id. at 718.

31 Onyekwere, supra note 1.

32 Id.

33 Id.

34. Id.

35 After Cash Bail: A Framework for Reimagining Pretrial Justice, supra note 9.

36 Gloria Gong, The Next Step: Building, Funding, and Measuring Pretrial Services (Post-Bail Reforms), 98 N C L REV 389 (2020).

16 W. MICH.

U. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 38:1

local governments to redirect scarce funds away from the machinery of incarceration toward prevention and reinvestment.”37

A. Undermining the Presumption of Innocence

In the nineteenth century, state and federal courts agreed that the United States Constitution entitled the accused to pretrial release, except when charged with a capital offense.38 Around the same time, there was also debate that denial of bail violated a defendant’s presumption of innocence.39

“The ultimate goal of bail reform is to reduce pretrial incarceration rates. Bail reform seeks to align this goal with ensuring pretrial justice and preserving the presumption of innocence.”40 Cash bail conflicts with this constitutional protection that is fundamental to the American criminal law system.41 Jail sentences are regularly handed down as punishment; however, cash bail forces people to remain in jail before being convicted simply because they cannot pay.

42

B. The Cost and Effect of Money Bail

The high costs of money bail affect individual defendants and their families when they have to post bonds directly or are subjected to the high interest rates and non-refundable fees of commercial bail bondsmen.43 Defendants who are unable to pay their bail costs are

37 Id.

38 Shima Baradaran, Restoring the Presumption of Innocence, 72 OHIO ST. L J 723, 730 (2011).

39 Id.

40 Dana Kramer, Bail Reform: A Possible Solution to Missouri’s Broken Public Defender System?, 85 MO. L. REV. 314 (2020).

41. Tracey Meares & Arthur Rizer, The “Radical” Notion of the Presumption of Innocence, THE SQUARE ONE PROJECT, at 16 (last visited Mar. 26, 2023), https://www.safetyandjusticechallenge.org/wp-content/uploads /2020/05/CJLJ8161-Square-One-Presumption-of-Innocence-Paper-200519WEB.pdf.

42. Eli Savit & Victoria Burton-Harris, Policy Directive 2021-02: Policy Eliminating the Use of Cash Bail and Setting Standards for Pretrial Detention, WASHTENAW CNTY., at 1 (last visited Dec. 7, 2021), https://www.washtenaw.org/DocumentCenter/View/19064/Cash-BailPolicy.

43 Gong, supra note 36, at 390.

2023] BAIL REFORM ACROSS AMERICA 17

already at a financial disadvantage, and they are further disadvantaged by losing wages during pre-trial detention.44 The fee incurred by defendants to bail bondsmen “trap[s] poorer people in a cycle of debt and poverty.”45 Defendants who cannot afford their bail are in a weak bargaining position as it relates to not only plea bargains but also to commercial bondsmen.46

Commercial bondsmen provide two justifications for the industry.47 First, their profession requires privatization to maintain a high level of skill and experience and to ensure that high rates of court appearances are maintained.48 However, fleeing in modern times is far more difficult than it was in the nineteenth century, and there is a lack of statistical evidence to support the commercial bond industry’s claims.49

For example, Washington D.C. eliminated cash bail in the 1960s and has almost entirely eliminated the commercial bond industry.50 Despite this, D.C. has high rates of court appearances, with ninetyfour percent of defendants released pretrial and ninety-one percent of defendants appearing at trial.51 The Brooklyn Bail Fund, a charitable bail fund that provides bail to defendants for free, has reported that ninety-five percent of clients make their required court appearances.52

“The second purported justification for commercial bail is that the industry promotes public safety.”53 However, the sole financial interest of these private companies is to prevent the flight of a defendant, not to prevent crime.54 There is no way to differentiate how commercial bail bondsmen incentivize their clients to attend court versus deterring them from committing crimes.55

In 2007, the American Bar Association (ABA) provided four reasons to support their recommendation to abolish the commercial

45. Savit & Burton-Harris, supra note 42, at 2.

46. James Gordon, Corporate Manipulation of Commercial Bail Regulation, 121 COLUM. L REV. F. 115, 121-22 (2021).

122.

18 W.

MICH. U. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 38:1

44 Id.

49

Id. 51. Id. 52 Id. 53 Id. 54 Id. 55 Id.

47 Id. at

48 Id.

Id. at 123. 50

bail industry.56 The first reason is that a defendant’s ability to contract with commercial bondsmen does not promote the aim of protecting public safety.57 Second, the existence of the commercial bondsmen industry “transfers the decision of which defendants are an acceptable flight risk to the commercial bondsman.”58 Third, there is an apparent lack of transparency as to the contractual terms that a defendant has with the commercial bondsman.59 “[F]ourth, the industry discriminates against low-income defendants who cannot afford the nonrefundable premium, regardless of whether the defendant is a flight risk or poses a risk to public safety.”60 Put simply, the ABA recommends abolishing the commercial bail industry because it does nothing to further the societal aims of bail.

Neither history nor policy justify or provide an adequate explanation for the necessity of the commercial industry.61 As money bail becomes less utilized citywide or nationwide, the commercial bail industry will not be as easily sustained. Therefore, as money bail decreases, so will the use of the commercial bail industry.

C. Judicial Interpretation of Prejudicial Bail

Recently, the Supreme Court of Nevada entertained a writ of mandamus filed by two men, Frye and Valdez-Jimenez, who were restricted to pre-trial detention.62 The petitioners argued that their bail amounts, $250,000 and $40,000, respectively, were excessive and violated their due process and equal protection rights.63 Petitioners argued that imposing money bail in an amount they could not afford to pay “denied them substantive and procedural due process and equal protection under the Nevada and United States Constitutions.”64

Petitioners’ contentions required the Nevada Supreme Court to review the constitutionality of the State’s “statutory scheme for

56 Id. at 120.

57 Id.

58 Id. at 120-21.

59 Id. at 121.

60 Id.

61. Id. at 124.

62 See Valdez-Jimenez v. Eighth Judicial Dist. Court of Nev., 460 P.3d 976, 981 (Nev. 2020).

63 Id. at 980-81.

64 Id. at 983-84.

2023] BAIL REFORM ACROSS AMERICA 19

pretrial release,” including the presumption of money bail and requiring defendants to show good cause for release on non-monetary conditions.65

[The court concluded that b]ail may be imposed only where necessary to ensure the defendant’s appearance or to protect the community is also mandated by substantive due process principles. Because bail may be set in an amount that an individual is unable to pay, resulting in continued detention pending trial, it infringes on the individual’s liberty interest. And given the fundamental nature of this interest, substantive due process requires that any infringement be necessary to further a legitimate and compelling governmental interest.66

The court held that when bail is set greater than is necessary to serve the purpose of the use of bail, a defendant is denied their “rights under the Nevada Constitution to be ‘bailable by sufficient sureties’ and for bail not to be excessive.”67 The holding of this case stressed the importance of due process protections in order “to safeguard against pretrial detainees sitting in jail simply because they cannot afford to post bail.”68

The court upheld the purpose of bail, when necessary, to ensure that a defendant will appear in court when required and to promote community safety.69 However, when a defendant is arrested and remains detained, they have the right to a hearing at which evidence must be provided to show that bail is necessary to ensure the defendant will not flee.70 However, at the time of the court’s decision, the defendants were no longer subject to pretrial detention, so their petitions for writ of mandamus were denied.71 However, the court used this case as an opportunity to denounce excessive cash bail and protect defendants’ due process rights through individualized considerations of bail.

65 Id. at 984.

66 Id. at 984-85.

67. Id. at 988.

68 Id. at 980.

69 Id. at 988.

70 Id.

71 Id.

20 W. MICH. U. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 38:1

D. Enacting Policies to Support Bail Reform

The Washtenaw County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office in Michigan released Policy Directive 2021-02 enacting a no-cash-bail policy.72 This policy directive states, “Assistant Prosecuting Attorneys (APAs) will be required to fill out the Bond Information Form in all cases. APAs may not seek cash bond in any case.”73

This directive still allows for “unsecured appearance bonds, surety bonds, and where lawful categorical denial of pretrial release.”74 A preference will also be shown for the least restrictive release conditions while still considering public safety as a concern.75 This means that in most cases, defendants will be released on their own personal recognizance.76 In some cases, additional conditions will be placed on a defendant to avoid flight risks. These conditions include drug and alcohol testing, driving restrictions, GPS tethers, no contact orders, travel restrictions, house arrest, firearm and weapon restrictions, or release to a responsible member of the community.77

A directive such as this seems to be a small step. While cash bail is no longer being used in Washtenaw County, the county is utilizing other techniques to deter defendants from fleeing and to encourage behaviors that would reduce their likelihood of recidivism and possible danger to the public. Washtenaw County reported that in March 2020, there were 332 people in the county jail, and by the end of April, after releasing non-threatening defendants and those on cash bonds less than $1,000, only 147 remained.78 Further, the county did not find that the directive caused a crime wave.79 “Our . . . experience demonstrates that, as in Washington D.C. and New Jersey, bail reforms can be implemented locally without threatening public safety.”80

Implementation of bail reform at the local level will be discussed in later sections of this comment.

72 Savit & Burton-Harris, supra note 42, at 7.

73 Id. at 8.

74 Id.

75 Id.

76. Id.

77 Id. at 9-12.

78 Id. at 4-5.

79 Id. at 5.

80 Id.

2023] BAIL REFORM ACROSS AMERICA 21

E. Weaknesses of Current Reform

To make significant strides in the effort for bail reform, attorneys must have the time and resources to zealously advocate for their clients, especially clients with insufficient means to defend against pretrial detention. Public defenders have limited time and resources, and the Missouri Public Defender System is an example. This program has been underfunded and understaffed since the legislation to represent indigent defendants passed.81 This is an issue for indigent defendants in Missouri, as their attorney’s ability to advocate on their behalf is “imperative to protecting indigent defendant’s pretrial procedural rights.”82 Based on the Missouri Public Defender’s current funding, its attorneys are forced to choose which cases require their attention.83 This leads to “misdemeanors and lesser felonies the cases that would benefit the most from representation at bail hearings generally go[ing] uninvestigated” due to a lack of time for motion practice, a lack of legal research, and high caseloads.84

“[I]ncreas[ing] funding and. . . manpower would reduce the number of cases appointed to each public defender. This, in turn, would afford public defenders the time to represent indigent defendants at initial appearances.”85 If more defendants could be released from pretrial detention, return home to be with their families, and have the opportunity to work and earn money to support their household, bail reform would be successful. To ensure that the promises of bail reform are delivered, it must be supported by wellfunded and well-staffed legal aid programs for indigent defendants, primarily our public defender system.86

The state of Illinois passed the Bail Reform Act of 2017 in response to the number of defendants subjected to pretrial detention because they could not afford to post money bail.87 Elgie Sims, an Illinois representative who sponsored the bill, reasoned that the bail system in Illinois was broken, and the reform would ensure those who were a threat to public safety would remain detained, but those

81 Kramer, supra note 40, at 301.

82 Id. at 318.

83 Id.

84. Id.

85 Id.

86 Id. at 319.

87 David Taseff, The Illinois Bail Reform Act of 2017: Roadmap to Reform, or Reform in Name Only?, 38 N ILL. U L REV. 528, 531 (2018).

22 W. MICH.

U. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 38:1

who were poor or suffering from mental health and substance abuse issues would not.88

In an effort to reduce the number of pretrial detainees, the Bail Reform Act authorized a statewide risk-assessment tool, called the Public Safety Assessment, to be used in all bail cases.89 The Act provides that defendants with low-level and nonviolent offenses will be released in a substantial number of criminal cases.90 Where a bond is set above an amount that a detainee can pay, a “mandatory bond review within seven calendar days is likely to process eligible arrestees out of the county jails faster, and more efficiently.”91

The Act, however, is not without its flaws.

[T]he Act’s greatest weakness lies not in its reforms, but rather, its lack thereof. Left unchanged by the Act is a provision in the Bail Code in direct conflict with the presumption that all conditions of bond shall be non-monetary in nature.92

Although a defendant may not have to sit in jail while waiting for their court dates, they may be subject to a separate risk assessment and subject to GPS surveillance that they have to pay for.93 Thus, although the conditions of release may be “non-monetary,” they are still very much monetary in nature and a source of unexpected expense. “GPS monitoring as an alternative to pretrial incarceration appears to be ingenious;” the cost for a GPS ankle bracelet is $800 total, or it can range from around $60 to $143 per day to house an inmate in different county jails in Illinois.94 While the yearly taxpayer cost of GPS, $2,815, is less than that of the yearly cost for an inmate housed in the Cook County Jail, $8,151, the cost is being transferred from the taxpayer to the defendant.95

In addition to the costs assessed to defendants during pretrial, “an estimated forty percent of the jail population in the United States has some form of chronic mental illness.”96 In 2008, the Illinois Mental

2023] BAIL REFORM ACROSS AMERICA 23

88 Id. 89 Id. at 541. 90 Id. at 543. 91 Id. 92. Id. at 544. 93 Id. 94 Id. at 547. 95 Id. 96 Id. at 549.

Health Court Act authorized each Chief Judge of the judicial circuits to establish a mental health court program.97 However, a study in 2015 found that six of the twenty-one responding courts had no plans to establish a mental health court, and six more were still in the planning process.98 Having several mentally ill inmates and no concrete plan to establish resources shows a blatant lack of concern for these inmates. While Illinois has attempted to take steps to reform the issues that cash bail poses for arrestees and defendants, they have instead imposed alternate ways on those already burdened by a lack of resources or by the criminal justice system. There is still work to be done in Illinois.

IV. A COMPARISON OF REFORM

While implementing bail reform and coinciding resources in areas such as Missouri, Illinois, and Washtenaw County, Michigan, have previously been discussed, there are further efforts in the United States to reform the discriminatory effects of the money bail system.

A Statewide Reform

At a state level, California passed the California Money Bail Reform Act of 2017 (known as SB 10), the first piece of legislation to completely abolish monetary bail.99 SB 10 received heavy criticism as a progressive piece of legislation that allows for high-risk defendants to avoid “preventative detention unless certain motions are made and granted by the court.”100 For a judge to order a defendant to be held in pretrial detention, there must be a “substantial likelihood that no nonmonetary condition or combination of conditions of pretrial supervision will reasonably . . . assure public safety.”101 While this has been noted as a progressive move towards bail reform, possibly due to its early passage date, it is comparable to legislation passed years later by other states, such as Missouri, that

97 Id.

98 Id.

99. Ashley Mullen, Incarceration or E-Carceration: California’s SB 10 Bail Reform and the Potential Pitfalls for Pretrial Detainees, 104 CORNELL L. REV. 1867, 1876 (2019).

100 Id. at 1884-85.

101 Id. at 1885.

24 W. MICH. U. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 38:1

considered non-monetary conditional release techniques before utilizing money bail.102

Kentucky’s reforms are unique compared to other states’ reforms. In the state of Kentucky, there are no corporate bondsmen, although a judge still has the option to give money bail to defendants.103 As previously discussed, the commercial bail bondsmen system is predatory to defendants and represents one of many issues to be reformed with the current utilization of bail. Kentucky is one of the few states where the bail bondsmen system is illegal.104 Kentucky also saw statewide reform in 2011 when House Bill 463 passed, significantly changing the state’s pretrial detention policies.105 House Bill 463 altered drug laws and post-incarceration processes in the state, including the probation and parole process.106 Kentucky has taken a unique approach to bail reform compared to other states. It has seen statistical success, with overall pretrial releases increasing from five percent to seventy percent of all defendants in the first year.107

The state of Missouri saw bail reform changes when its Supreme Court adjusted Missouri Court Rules of Criminal Procedure 21, 22, and 23 in January 2019, which changed their use of pretrial detention.108 These adjustments created a procedure in which defendants, who are arrested subject to a warrant, must appear before a judge within forty-eight hours to determine whether they must be detained or whether a conditional release is proper.109 The court must first consider nonmonetary conditional release and whether this will prevent the defendant from fleeing before their court date.110 If a defendant requires monetary conditional release, the court must consider the defendant’s “ability to pay and cannot impose a higher

102 Kramer, supra note 40, at 312-13.

103 Patrick Orsagos, A Tour of Bail: How Other States Have Reformed the Money Bail System, WV PUB. BROAD. (Aug. 23, 2021), https://www .wvpublic.org/top-stories/2021-08-23/a-tour-of-bail-how-other-states-havereformed-the-money-bail-system.

104 Robert Veldman, Pretrial Detention in Kentucky: An Analysis of the Impact of House Bill 463 During the First Two Years of its Implementation, 102 KY. L J 777, 780 (2013-14).

105 Id. at 777.

106. Id. at 783.

107 Id. at 789.

108 Kramer, supra note 40, at 312.

109 Id.

110 Id. at 312-13.

2023] BAIL REFORM ACROSS AMERICA 25

payment than necessary to ensure the defendant appears at trial or the community’s safety. Only upon a determination by clear and convincing evidence may a court detain a defendant pretrial.”111

New Jersey’s bail reform efforts in 2017 “aimed to replace judicial discretion regarding pretrial detention with an objective, scientific assessment based on empirical data and risk factors.”112 These assessments, called Public Safety Assessments, are similar to those of Illinois and recommended the conditions of release to be based on nine risk factors.113 Each of the nine factors add points to a defendant’s raw score; points that total into a raw score, which is converted into a six-point scale.114 A score of one is the lowest risk, and a score of six is the highest risk; a score is determined for three categories: failure to appear, new criminal activity, and risk of new violent criminal activity.115

The death of Kalief Browder sparked bail reform in New York state. The main goal of this reform was to “diminish economic inequality in its bail and pretrial detention systems.”116 The state saw a forty percent reduction in pretrial prison populations within three months.117 New York had some of the harshest critics, with some suggesting that bail reform was to blame for a rise in crime after passing significant changes to the bail laws in 2020.118 However, the data clears the smoke of speculation. Out of the crimes committed in New York City in early 2020, eighty-four crimes (in a city of over eight million people) were committed by people released from pretrial detention without bail related to a different crime.119

While many of these states have seen successful implementations of bail reform, West Virginia is not without its growing pains. In June 2020, West Virginia passed HB 2419 to limit bail amounts and shrink its jail population.120 Coincidentally, West Virginia passed the bill at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic when jails and

111. Id. at 313.

112. Id. at 309.

113 Id.

114 Id. at 309-10.

115 Id. at 310.

116 Daniel Chasin, Two Steps Forward, One Step Back: How New York’s Bail Reform Saga Tiptoes Around Addressing Economic Inequality, 43 CARDOZO L. REV. 273, 279-80 (2021).

117 Id. at 280.

118 Savit & Burton-Harris, supra note 42, at 5.

119 Id.

120 Orsagos, supra note 105.

26 W. MICH. U. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 38:1

prisons across the United States released defendants to prevent the spread of the disease.121 However, by mid-March 2021, regional jails were at 144% of maximum capacity.122 Despite these issues, the state’s judges and the legislature have strived to reduce mass incarceration in their region. They must now continue to reform the current bail system in hopes of returning defendants to their families and jobs and protecting community safety.123

B Local Reform

As previously discussed, the Washtenaw County Prosecutor’s Office has implemented a strategy to proscribe cash bail from being utilized by Assistant Prosecuting Attorneys.124 Washington D.C. has not utilized cash bail or the commercial bail industry since reforms in 1960. 125 Reform for using money bail need not always be passed legislatively or even at a state level. Washtenaw County and Washington D.C. are examples of successful implementations of local reform.

V. CONCLUSION

Cash bail is discriminatory to impoverished defendants, as it deprives them of their due process rights. Those defendants are forced to sit in jail, missing their family, and losing out on wages while awaiting a trial or even mere initial court date (as Kalief Browder did on Rikers Island for three years126) because their household could not afford to pay their bail premium. Defendants are not entirely out of options; most states have a thriving commercial bail bondsman industry that provides predatory interest rates and requires a nonrefundable fee, further consigning the defendant to a cycle of poverty.

The inequality that our current system of cash bail imposes on defendants is slowly becoming a thing of the past as states implement nonmonetary conditional release, establish risk assessment systems,

121 Id.

122. Id.

123 Id.

124 Savit & Burton-Harris, supra note 42, at 6.

125 Gordon, supra note 46, at 123.

126 Johnson, supra note 3, at 30

2023] BAIL REFORM ACROSS AMERICA 27

and abolish the commercial bondsman industry. Further, local reform allows more defendants to remain out of jail before a guilty plea or verdict is reached. Further reforms with the use of mental health courts are currently being implemented in Illinois,127 and additional funding of public defender programs to provide more individualized advocacy to indigent defendants can affect the number of defendants who are subjected to pretrial detention.128 Justice must be affordable to all.

127 Taseff, supra note 87, at 549-50.

128 Kramer, supra note 40, at 319.

28 W. MICH.

U. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 38:1

MEMORY: THE PAST, PRESENT & FUTURE OF LAW SCHOOL EXAMS

MATTHEW MARIN & AMANDA FISHER1

I. INTRODUCTION

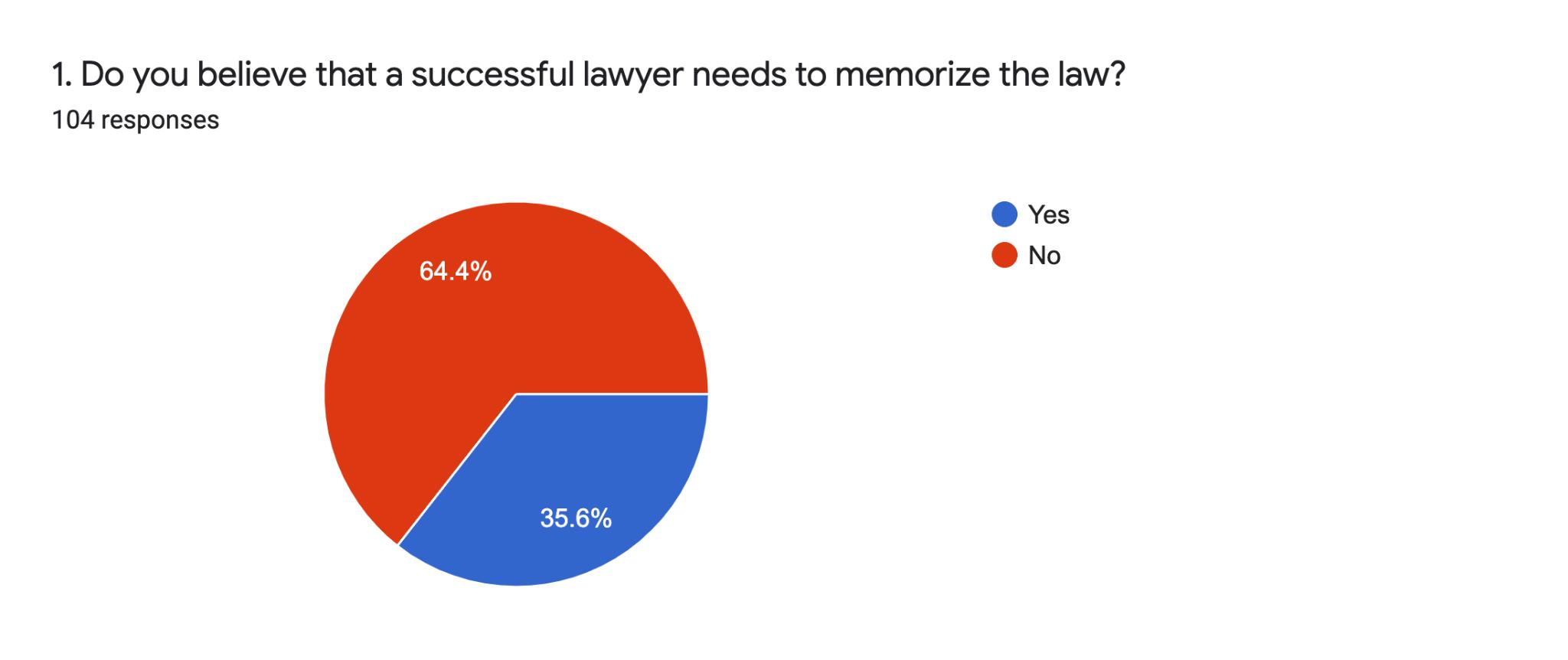

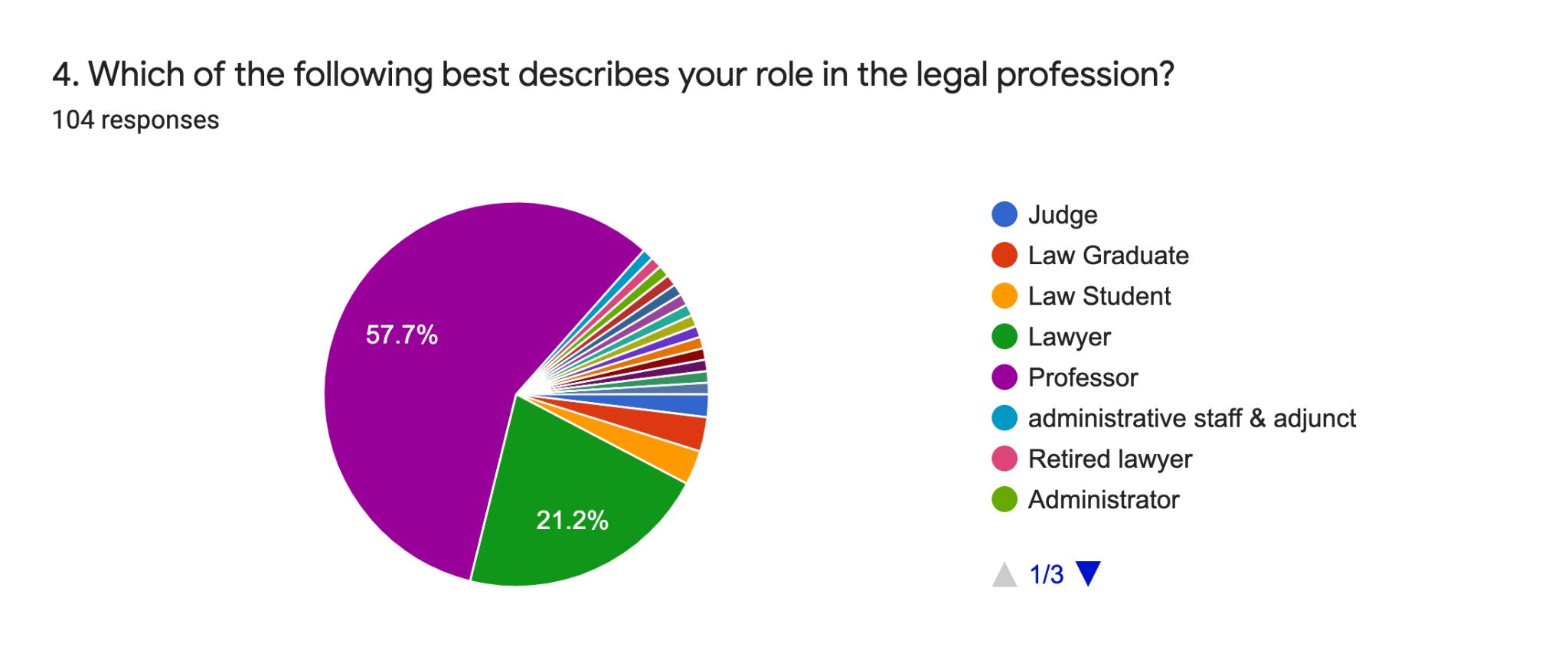

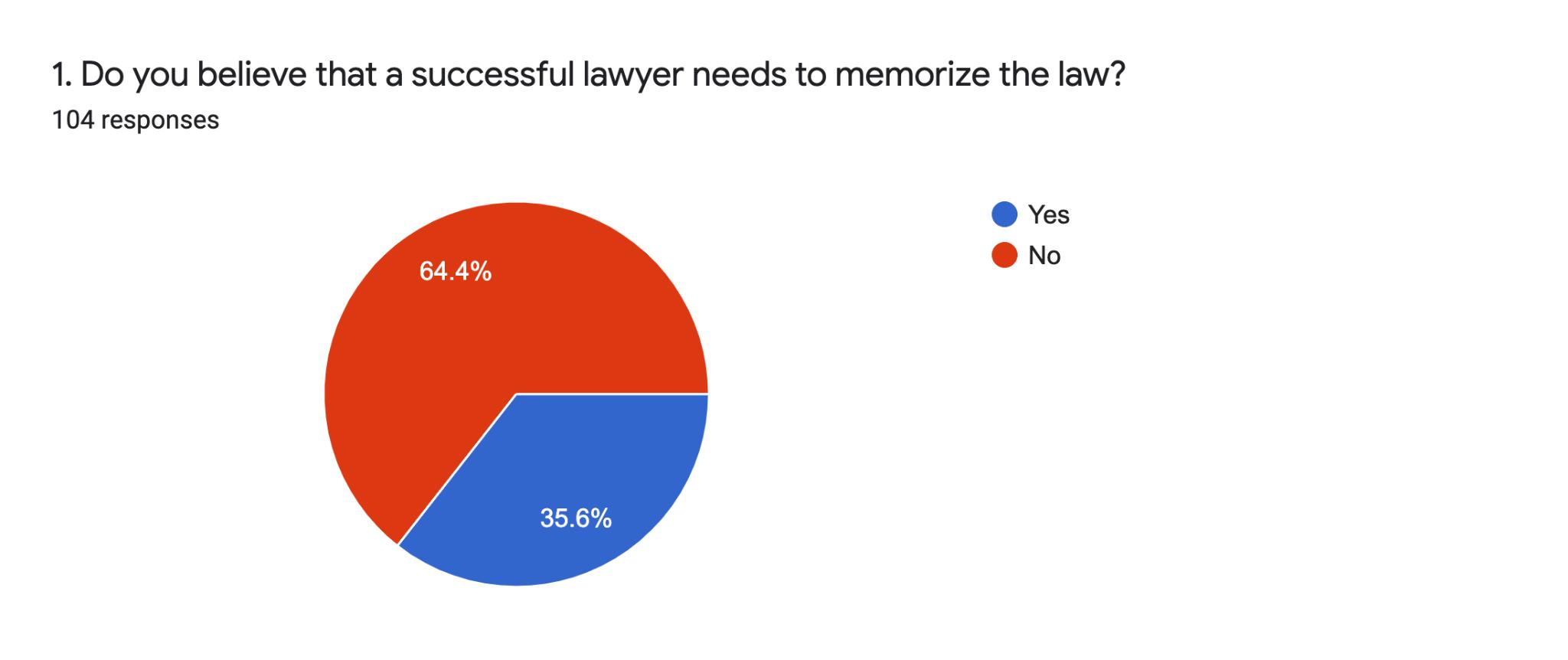

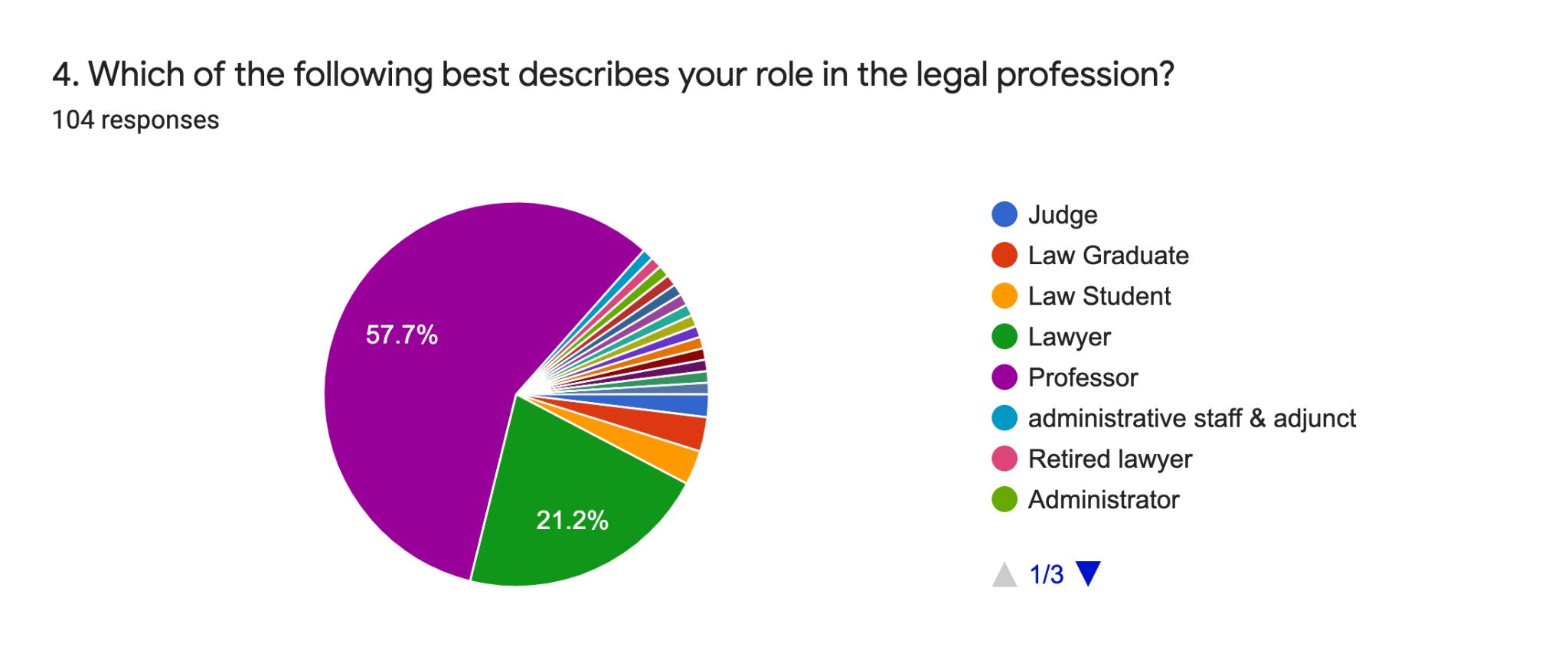

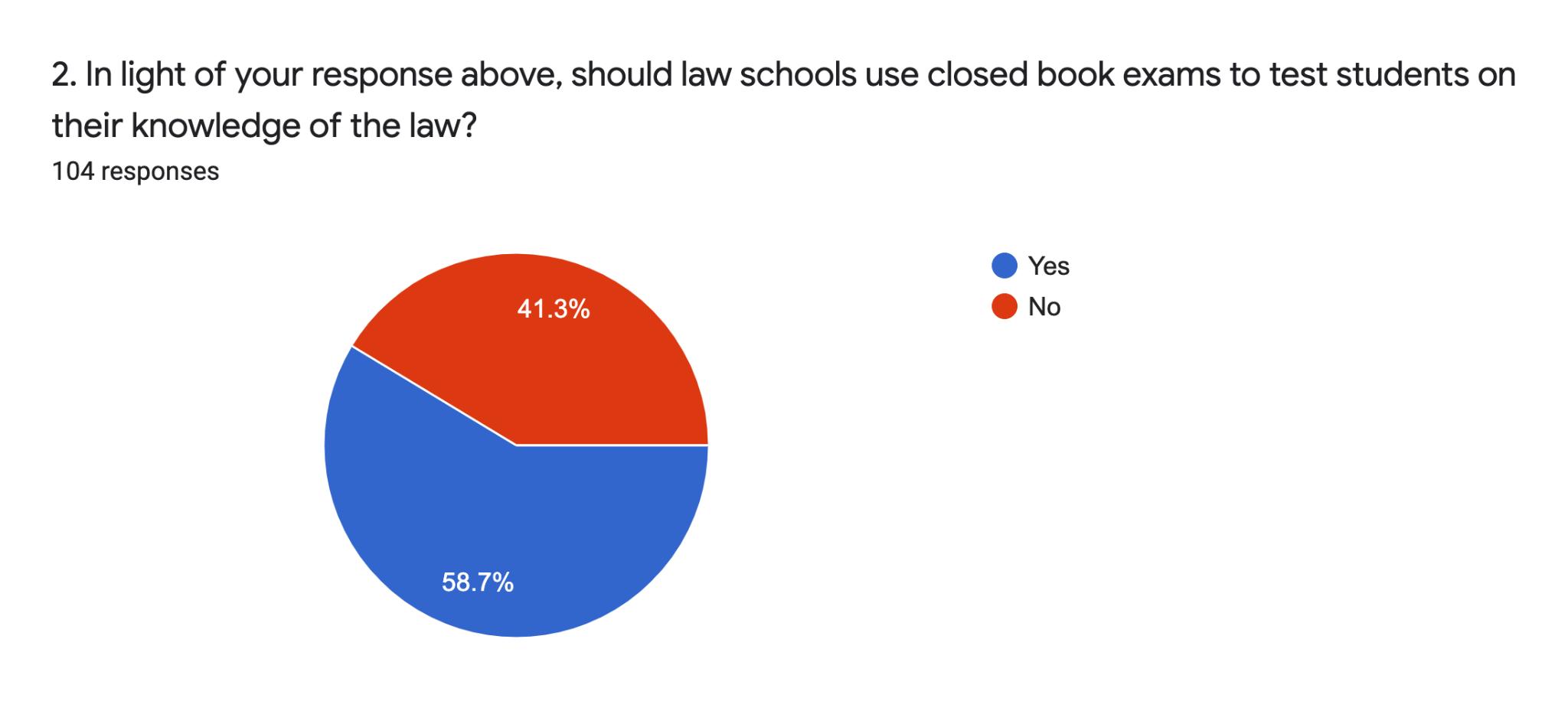

Lawyers must have a basic understanding of the rules of law. To prepare students for practice, law schools must help students memorize copious amounts of law, concepts, and values, because memorization is ingrained in acquiring licensure. But do licensed attorneys actually practice based on rote memorization? Is an attorney expected to memorize and never consult or look up rules and other authorities? In essence, does pure memorization of rules produce successful lawyers?

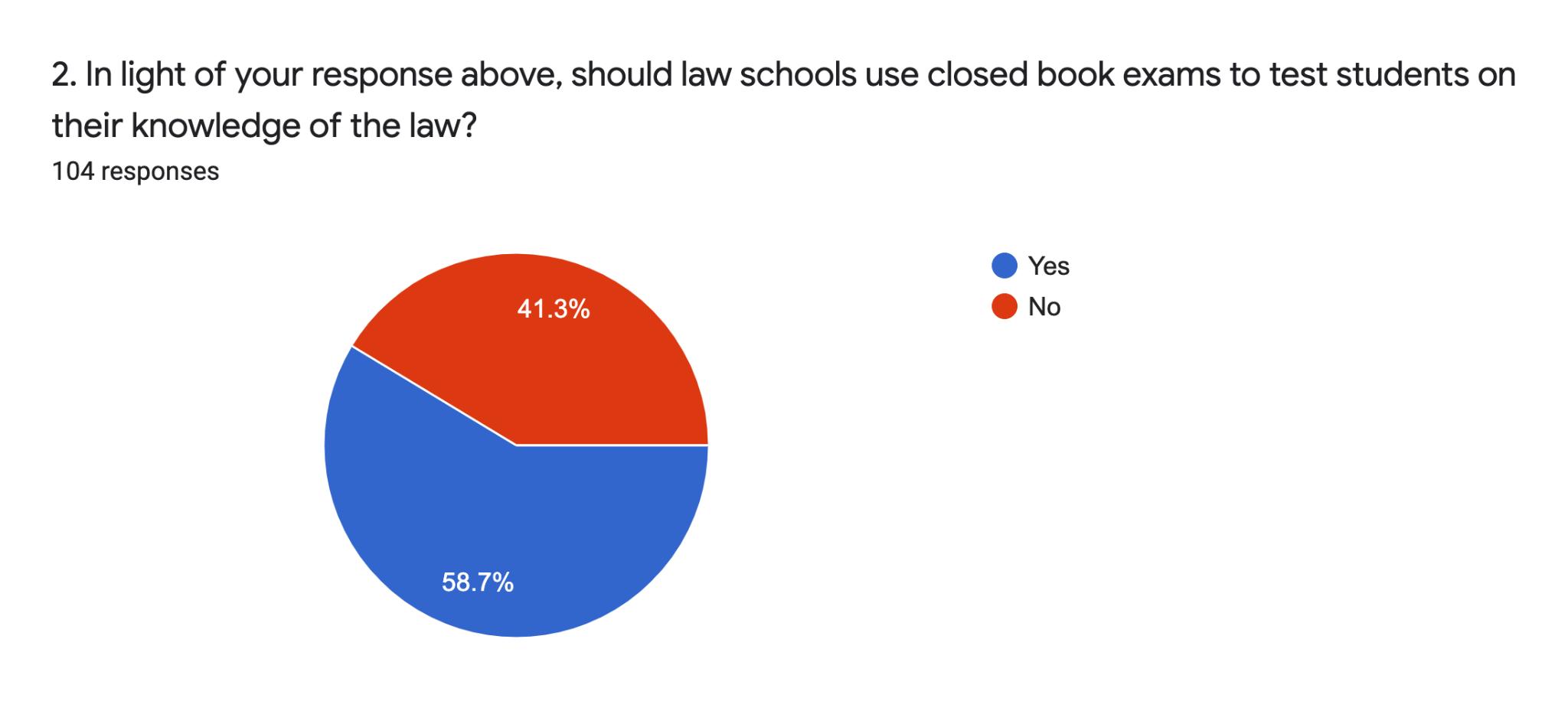

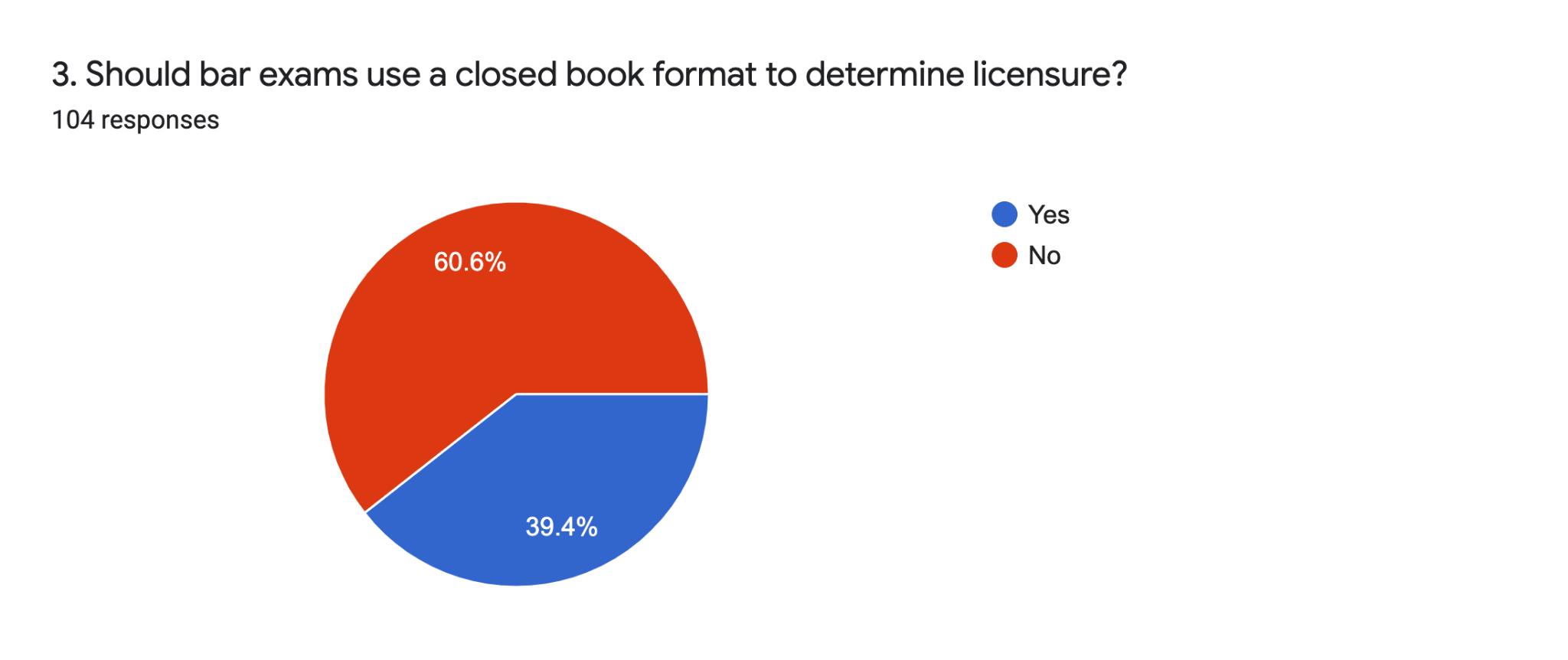

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many law schools transitioned to online instruction and final examinations. Though some institutions had open-book exams pre-COVID-19, anecdotally, these exams were reserved for electives and non-bar tested subjects. Because of this shift to a virtual environment, law schools had to adapt and implement online (and in some cases, untimed) final exams. Now, as most law schools transition back to traditional instruction in person, closed-book final exams have returned. But should it be that way? A knee-jerk response would be to say “yes” because licensure still demands rote memorization. But as more jurisdictions transition to other modes of testing, such as performance tests, where the law is provided in a writing task, and because of the modifications that COVID-19 caused, this is the perfect opportunity to reassess going back to “business as usual.” It is long past time to realign law school and bar examinations with how the actual practice of law is conducted.

1. Matthew Marin is an Associate Professor of Law and Director of Academic Support Services at WMU-Cooley Law School. Amanda Fisher is an Assistant Professor of Law at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville School of Law The Authors produced this research and Article for the Hamilton Luger Law School COVID Care Crisis Symposium, Part II, and it was presented on June 17, 2022.

II. BACKGROUND Assessments

Assessment is a process that can help students improve their learning.2 In particular, assessments ensure that an instructor is teaching well, provide law schools with the information needed to change curriculum, and assist with setting policy.3 Interestingly enough, the concept of assessment, though not new, was incorporated into law school curriculum fairly recently.4 Many other disciplines have used multiple forms of assessment for a long time.5 Formative assessment is used to monitor students’ learning, assess knowledge, and help improve learning.6 A subcategory of formative assessment is diagnostic assessment, which is used to identify learners’ difficulties in certain areas and to provide insight into the learner’s weaknesses for remediation.7 Another common type of assessment is portfolio assessment.8 Here, teachers give students certain tasks, and learning is assessed based on collective work.9 Other categories include self-assessment and peer assessment. Lastly is summative assessment, which is performed or assessed at the final stage of a course.10 Summative assessment “refers to the cumulative assessments, [and it] usually occur[s] at the end of a unit or topic coverage, that [is] intended to capture what a student has learned, or

2 ANDREA SUSNIR FUNK, THE ART OF ASSESSMENT: MAKING OUTCOMES ASSESSMENT ACCESSIBLE, SUSTAINABLE, AND MEANINGFUL 14 (2017).

3. Id.

4 Id. at 13; see also ABA Standards 301, 302, 314, and 315.

5 James S. McGrath & Andrew P. Morriss, Assessments All the Way Down, 21 GREEN BAG 2d 139, 146 (2018) (“[P]rior to [ABA standards that went into effect in 2016], not many law schools performed regular program assessment, although it is the norm in virtually every other discipline.”)

6. Muhammad Saeed et al., Teachers’ Perceptions About the Use of Classroom Assessment Techniques in Elementary and Secondary Schools, BULLETIN OF EDUCATION & RESEARCH, Apr. 2018, at 117; see also Haifa F. Bin Mubayrik, New Trends in Formative-Summative Evaluations for Adult Education, SAGE J., July-Sept. 2020, at 10 (stating that “formative evaluation is used to alter and improve learning.”)

7. Saeed et al., supra note 7, at 118.

8. Id.

9 Id. (stating that portfolio assessment will provide information about a student’s performance on longitudinal observation and assess progress over that time).

10 Bin Mubayrik, supra note 8, at 3.

30 W. MICH.

U. COOLEY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 38:1

the quality of the learning, and judge performance against some standards.”11 In addition, it is used to determine whether the student has met course learning objectives; summative assessments generally utilize all topics covered in the course when testing.12

In 2014, the American Bar Association (ABA) required that law schools start providing formative assessments rather than basing their curriculum around one final, summative exam.13 In conjunction with the adoption of Standards 314 and 404, the ABA also released a transition memo that further clarified the assessment mandates: (1) faculty engagement in creating learning outcomes; (2) how the curriculum encompasses the outcomes and the integration of teaching and assessment of the outcomes in the curriculum; (3) how and when students receive feedback regarding their progression on the outcomes; and (4) efforts to gather information on students learning and to use that information.14 This caused law schools to shift from the traditional model that utilized one final examination to one that incorporates additional assessments throughout the term.15 Though it does not fall under the umbrella of law-school testing, the ultimate

11 National Research Council, Classroom Assessment and the National Science Education Standards, NATIONAL ACADEMICS PRESS, 25 (2001).

12 Bin Mubayrik, supra note 8, at 3.

13 Victoria L. VanZandt, Assessment Mandates in the ABA Accreditation Standards and Their Impact on Individual Academic Freedom Rights, 95 U. DET. MERCY L. REV. 253, 253 (2018).

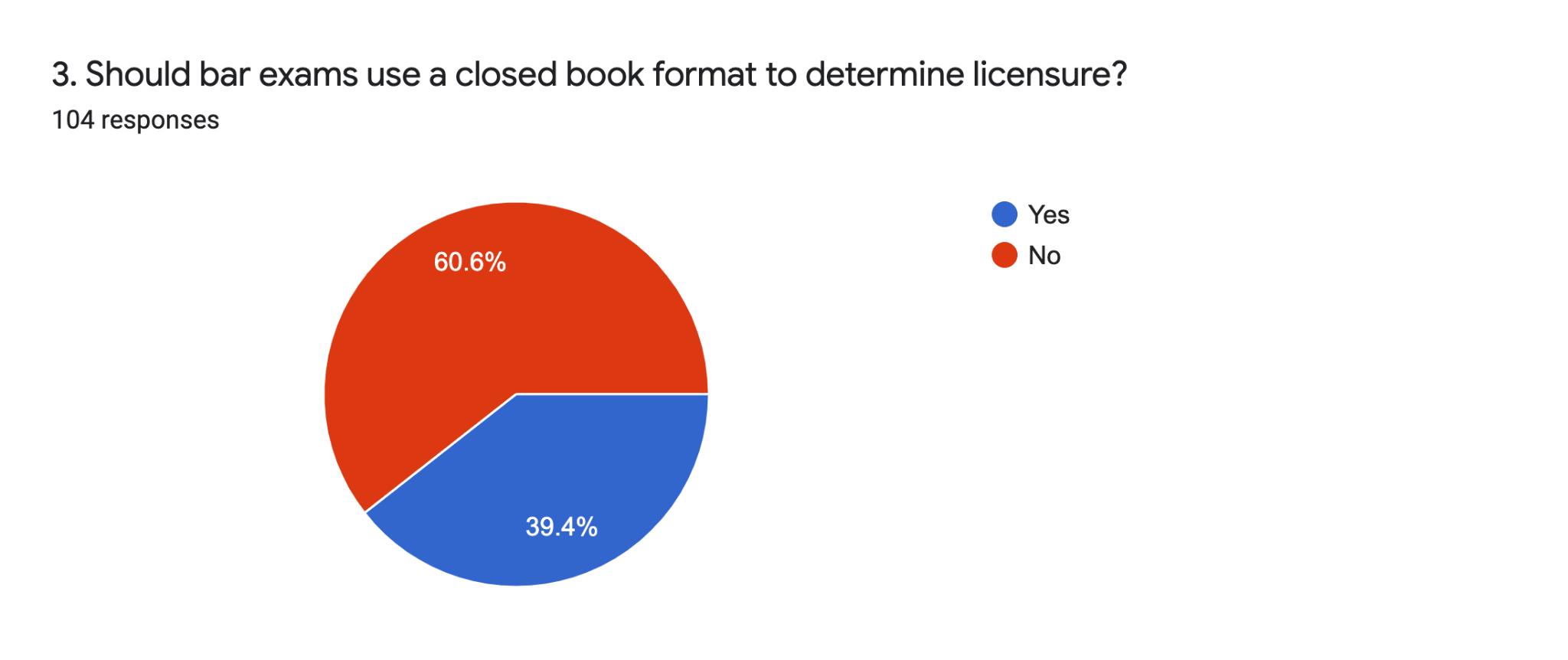

14. Id. See also Transition to and Implementation of the New Standards and Rules of Procedure for Approval of Law Schools, A.B.A.(Aug. 13, 2014), http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/legal _education_and_admissions_to_the_bar/governancedocuments/2014 _august_transition_and_implementation_of_new_aba_standards_and_rules. authcheckdam.pdf.