6th November 2025

Hosted by The Construction IT Alliance

Edited Dr. Alan Hore

Dr. Barry McAuley

Professor Roger West

Published in 2025 ISBN 978-1-911652-00-7

Published by The Construction IT Alliance.

© Copyright Declaration: All rights of papers in this publication rest with the authors.

This publication is part of the proceedings of the CitA BIM Gathering Conference held on the 6th November 2025.

This publication can only be sourced online at www.bimgathering.ie.

Organisation Committee

Dr. Alan Hore

CitA (Conference Chair)

Suzanne Purcell

CitA

Aidan O’Connell

Punch Consulting

Sandra Gannon

IBM

Mary Flynn

Dublin City Council

Seán Dennison

GS1 Ireland

Dr. Claire Penny

TPS LTD

Gerard Nicholson

Atlantic Technological University

Sean Carroll

Munster Technological University

Scientific Committee

Dr. Alan Hore CitA

Professor Roger West

Trinity College Dublin

Barry McAuley

Technological University Dublin

Dr. Ken Thomas

South East Technological University

Dr. Martin Taggart

Atlantic Technological University

Dr. Conor Shaw

LUT University

Dr. Daniel McCrum

University College Dublin

Dr. Jason Underwood

Salford University

Professor Ibrahim Motawa

Ulster University

Dr. Malachy Mathews

Technological University Dublin

The 2025 CitA BIM Gathering carries special significance as it marks the 25th anniversary of the Construction IT Alliance (CitA), founded in 2000 in DIT Bolton Street with a clear purpose: to build a collaborative community that could accelerate the digital transformation of the Irish construction sector. Over the past 25 years CitA has grown from a small group of digital advocates into a national leader in BIM, digital construction, and more recently focusing on Modern Methods of Construction (MMC).

Our 2025 Gathering, held on 6 November in Dublin, was one of our strongest events to date. Under the theme “Realising Visions, Advancing Automation,” the conference brought together industry, academia, technology providers and government stakeholders at a time when the construction sector faces profound challenges: housing delivery, sustainability targets, productivity pressures and an urgent need for new skills. The discussions reinforced the sector’s shared ambition to use digital processes, reliable data and automation as enablers of better, faster and more sustainable project outcomes.

This year’s proceedings present 20 peer-reviewed papers reflecting the growing maturity and diversity of digital construction research. They cover topics including BIM for temporary works, automated compliance checking, heritage façade preservation, digital twins, simulation, data quality, safety, intelligent workflows and automated quantity

take-off. Many papers highlight the evolving relationship between BIM and MMC, emphasising the need for structured data, interoperable processes and industrialised approaches to design and construction. Others focus on people—skills, decision-making and organisational readiness. Collectively, these contributions demonstrate how BIM has advanced from a modelling tool to a strategic driver of transformation across the built environment.

As we celebrate 25 years of CitA, the principles that shaped the organisation in Bolton Street— collaboration, openness and shared learning— remain central to our mission. The success of the 2025 Gathering is a testament to the strength of the community that has formed around those values and its continuing commitment to digital excellence.

I would like to thank all authors, reviewers, delegates, partners and sponsors for their contribution to this year’s Gathering and for supporting CitA’s ongoing work. We look forward to building on this momentum as we enter the next chapter of CitA’s journey.

Dr. Alan Hore

Chair,

CitA BIM Gathering 2025

Best Innovation/Impact Papers

Sponsored by BAM UK and Ireland

Overall Best Paper Towards Urban-Scale Renovation: Integrating Multi-Agent Urban Digital Twin Framework with the RINNO Suite.

Omar Doukari and Marzia Bolpagni

Highly Commended BIM properties for a Psychological-Based Code Compliance Checking for Mental Healthcare facilities.

Silpa Singharajwarapan and Ibrahim Motawa

Automating Quantity Take-off and Data Validation in a BIM-Based Workflows.

Sean Auden and Malachy Mathews

Best Emerging Researcher Paper

Sponsored by Garland Consulting Engineers

Overall Best Paper

A critical review of the use of Generative Pre-trained Transformers (GPT) models in the generative design process of cleanroom architectural design.

Kemil Naidoo and Kieran O Neill

Highly Commended

A Process Map identifying pathways for integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools and techniques into clash management workflows within the design process of large-scale residential buildings.

Bruna Gil Donnarummo and Emma Hayes

Barriers and Enablers to Digital Document Approval in Common Data Environments within the Irish Construction Industry.

Ciara Sinden

Best Industry - Academic Collaboration Paper

Sponsored by John Paul Construction

Overall Best Paper Building the Future – The Role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Construction Management in Ireland and the UK.

Taseen Muhammad, Colin Harte, Daniel Clarke Hagan, Mary Catherine Greene and Michael Curran

Highly Commended Benchmarking Organisational BIM Certification in Ireland: Motivations, Benefits, and Future Needs.

Davitt Lamon, Barry McAuley and Mark Mulville

Visualising Embodied Carbon for Building Design.

Killian Collins and Malachy Mathews

CitA BIM Gathering Conference 2025 Sponsors

Platinum Sponsors

Gold Sponsors

Silver Sponsors

Theme 1: AI, Automation and Data-Driven Workflows

A process map integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI) tool and techniques into clash management workflows within the design process of large-scale residential buildings.

Bruna Gil Donnarummo and Emma Hayes, Technological University Dublin.

Building the future – The role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in construction management: in Ireland and the UK.

Taseen Muhammad, Colin Harte, Michael R. Curran, Daniel Clarke Hagan - Atlantic Technological University Sligo and Mary Catherine Green, Glenveagh Properties Plc.

A systematic analysis of the emerging synergy: Exploring the integration of BIM and AI for the future of construction.

Taseen Muhammad, Colin Harte, Michael R. Curran, Teni Bada, Enda Mitchell and Daniel Clarke Haga, Atlantic Technological University Sligo, Michael Curran, University of Limerick and Mary Catherine Greene, Glenveagh Properties Plc.

A critical review of the use of Generative Pre-trained Transformers (GPT) models in the generative design process of cleanroom architectural design.

Kemil Naidoo and Kieran O’Neill, Technological University Dublin.

AI agents and generative design: Reshaping architectural workflows for the built environment. Bruno Martorelli, MCROM Architects.

Theme 2: BIM Adoption, Maturity, Policy and Digital Delivery

Benchmarking organisational BIM certification in Ireland: Motivations, benefits, and future needs. Davitt Lamon, Barry McAuley and Mark Mulville, Technological University Dublin.

Building Information Modelling in Ireland 2025: A retrospective review of the BIM in Ireland 2019 report.

Barry McAuley, Technological University Dublin, Roger West, Trinity College Dublin (retired) and Alan Hore, Construction IT Alliance.

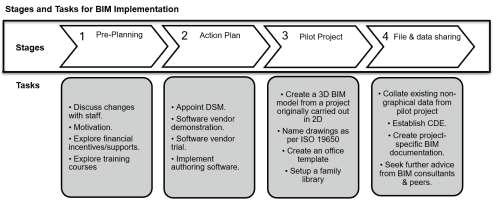

Navigating the CWMF mandate for a small architectural firm.

Ian McDonnell, AKM Design Group and Claire Simpson, Technological University Dublin.

Professionals’ perceptions of BIM effectiveness in construction projects: A comparative study between the United Kingdom and Saudi Arabia

Lina T. Karad, Pablo M. Rodriguez, Marzia Bolpagni, Northumbria University.

Barriers and enablers to digital document approval in Common Data Environments within the Irish construction industry.

Challenges & opportunities for construction SMEs.

Ciara Sinden, John Sisk & Son

Theme 3: Advancing Intelligent BIM Workflows

BIM for temporary works.

Craig Wilson, Strathclyde University and Ibrahim Motawa, Ulster University.

BIM properties for a psychological-based code compliance checking for mental healthcare facilities.

Silpa Singharajwarapan, Strathclyde University and Ibrahim Motawa , Ulster Universitye.

BIM for preserving building facades.

Panagiotis, Strathclyde University and Ibrahim Motawa, Ulster University.

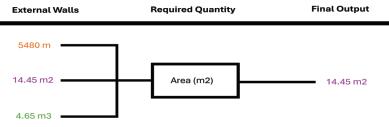

Automated quantity take-off and data validation in a BIM-based workflow.

Sean Auden and Malachy Mathews, Technological University Dublin.

Towards urban-scale renovation: Integrating multi-agent urban digital twin framework with the RINNO suite.

Omar Doukari and Marzia Bolpagni, Northumbria University.

Theme 4: MMC, Industry 4.0 and Emerging Construction Technologies.

Prospects and challenges of 3D concrete printing in Ireland.

Thomas Flynn, Paul Hamilton, Daniel Clarke Hagan, Atlantic Technological University Sligo, Michael Curran, University of Limerick and Mary Catherine Greene, Glenveagh Properties Plc.

Investigating the use of blockchain in the Irish Construction Industry.

Caoimhe Clarke Hagan, Daniel Clarke Hagan, Mairead Lynam, Atlantic Technological University Sligo, Michael Curran, University of Limerick and Mary Catherine Greene, Glenveagh Properties Plc. .

Theme 5: Sustainability, Circularity & Carbon Reduction

ARISE: Catalysing sustainable energy skills development through digital recognition and upskilling pathways.

Barry McAuley, Technological University Dublin, Eduardo Rebelo and Andrew Hamilton, Belfast Metropolitan College, Anna Moreno, Institute BIM Italy, Antonio Aguiar Costs, Universidade de Lisboa, Dijana Likar, Institute for Research in Environment Civil Engineering and Energy, Jan Cromwijk, Centraal Register Techniek, Paulo Carreira, Instituto Superior Tecnico and Paul McCormack, Hydrogen Ireland.

Visualising embodied carbon for building design. Killian Collins and Malachy Mathews, Technological University Dublin.

Sustainability – Use of BIM and construction waste management.

Shahida Kizhakke Thalakkal, Marzia Bolpagni and Talib E. Butt, Northumbria University.

Bruna Gil Donnarummo, brunadonnarummo@gmail.com

Technological

University Dublin

Emma Hayes, emma.hayes@tudublin.ie

Technological

University Dublin

Abstract

Building Information Modelling (BIM) is widely used to pre -check multidisciplinary designs, facilitate early clash detection and reduce coordination issues in early design stages. However, despite these advancements, traditional clash avoidance, detection, and resolution remain labour-intensive and time-consuming, limiting coordination effectiveness. Persistent inefficiencies, such as excessive false positives, manual filtering and grouping, and delayed conflict resolution decisions continue to constrain BIM’s potential to fully optimise coordination. This research aimed to investigate pathways and techniques - including machine learning, genetic algorithms, knowledge-based rules, and natural language processing - for integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI)into clash management and make this process faster, more accurate, and better suited to complex projects such as large -scale residential projects. The outcome was a structured process map address ing the gap between BIM and AI in clash management workflows according to BIM specialists’ feedback, offering practical AI-supported possibilities to optimise decision -making, reduce manual interventions, and improve design model quality.

Keywords: BIM Coordination, Artificial Intelligence, Clash Management

Over the past two decades, advancements in digital tools have significantly transformed the way designers work. Previously, they would sketch ideas on paper, then use AutoCAD to create drawings, and more recently, they would collaborate on Building Information Models (BIM) in the cloud to improve coordination and productivity. Now, AI promises to disrupt the Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) industry once again.

While data-driven insights can optimise the BIM process. There is limited expertise in identifying pathways and responsibilities for AI integration . Combined with a gap in research and practice, most studies focus on separate applications of BIM or AI (Zhang et al., 2022).This means professionals still spend considerable time coordinating design teams across disciplines, especially for complex challenges like clash management (Hsu et al., 2020).

Donnarummo and Hayes (2025), A Process Map integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI) into clash management workflows

During the design stages of large-scale residential BIM projects, models produced by various specialists, such as architects, structural and civil engineers, mechanical and electrical designers, are combined to pre-check designs visually and automatically identify clashes to mitigate the main projects’delay-causing factors (Pérez-Garcia et al., 2024).

In BIM workflows, the most important concern is how all potential issues can be identified early, coordinated efficiently and easily solved in a short period (Luo et al., 2022). However, the precision of clash detection within BIM -based processes is not sufficiently high and methods to simplify and optimise the work of BIM project teams during clash management have been underexplored (Akhmetzhanova et al., 2022).

Automated methods are urgently needed to quickly process large amounts of geometric data from a wider range of construction projects, and to reduce the need for manual intervention, minimising human errors or omissions (Pärn et al., 2018).

In light of this evolving approach, the purpose of this research is to develop a process map that identifies pathways to integrate AI -based solutions - including both AI tools and AI agents - to optimise clash management within the AEC industry’s design process. By examining existing workflows and evaluating the potential of AI to improve their efficiency, four objectives were outlined for this research, each providing context for the next objective:

1) To assess the existing key tasks in clash management workflows to identify gaps or time-consuming activities and investigate possibilities for AI to enhance efficiency.

2) To identify the typical clashes in large -scale residential buildings during the design stage and explore opportunities for utilising data from previous projects.

3) To identify the barriers to the adoption of AI in clash management workflows, informing an understanding of the challenges currently faced by the industry.

4) To develop a Process Map refined by BIM professionals to provide actionable insights tailored to specific needs to integrate AI into existing clash management workflows.

2. Literature Review

Design clash is comparable to ''collision'' or ''conflict'' and is defined as a positioning error where elements overlap each other when the original individual drawings or BIM models are merged (Pärn et al., 2018). Clashes can vary in nature, including "h ard" clashes, where two objects physically occupy the same space and "soft" clashes, where one object interferes with the operating or maintenance space of another (Akhmetzhanova et al., 2022).

Clash management includes two procedures: detecting clashes and solving clashes, which are traditionally integrated (Hu and Castro -Lacouture, 2018). This paper also includes clash avoidance in the study, since effective collaboration (leading to clash avoidance) and coordination (leading to clash detection and resolution) are key processes of the overall design development (Chahrour et al., 2021).

In a BIM project, clashes are identified in multi-disciplinary BIM models, and manually filtered, compiled, and presented during design coordination meetings where design teams collaborate to analyse the conflicts and discuss effective solutions. However, the detection precision of design clashes is not sufficiently high because the detection algorithms in BIM are too simple (Zhang et al., 2022). As long as two building components are spatially overlapping or within a given distance, they are recognised

Donnarummo and Hayes (2025), A Process Map integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI) into clash management workflows

as conflicts and included in the detection report (Lin and Huang, 2019) . Identifying and analysing this, given clash data, is still a labour-intensive task dependent on BIM managers and BIM coordinators (Akhmetzhanova et al., 2022).

Given the growing pressure for optimising design automation, research increasingly explores AI-driven solutions for clash management. Lin and Huang (2019) developed a machine learning method that can automatically filter irrelevant clashes, increasing detection accuracy by 15%–17%. Similarly, Hu and Castro-Lacouture (2018) applied supervised machine learning to distinguish relevant from irrelevant clashes, demonstrating how historical data and expertise can enhance the process

In terms of clash resolution, Liu et al. (2024) proposed an advanced genetic algorithm to automatically generate clash solutions based on spatial networks and priority constraints. A genetic algorithm is a heuristic search algorithm that mimics the evolutionary mechanism of natural selection, where strong individuals survive and the weak die, and only promising solutions are allowed to survive in the population (Yüksel et al., 2023). In their study, Liu et al. (2024) produced an automatic range of optimal solutions suggested to accelerate the decision -making to resolve clashes in underground parking in a residential project. The best solutions were based on the minimisation of both the number of elements involved and the minimum moving distance of components as optimisation objectives.

Moreover, a few studies highlight that proactive methods for avoiding clashes receive little attention, with research primarily focusing on detection and resolution. Teams often take a reactive approach, addressing clashes only after they occur (Pärn et al., 2018). AI-powered knowledge-based systems, however, can analyse patterns from past projects to help design teams anticipate and prevent clashes (Hsu et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2022).

In large-scale residential projects, the repetitive layouts and standardised MEP systems create predictable spatial conflicts, offering opportunities for AI -driven optimisation. Despite AI’s potential to enhance clash management efficiency and accuracy, most studies focus on a single discipline or task (Hu et al., 2023) rather than structure pathways and tools for the AI integration process. There is a lack of workflows that incorporate automation tools, faster decision -making supported by AI, dependency analysis, and proactive clash prevention strategies.

To address this gap, a structured process map establishing pathways for both AI agents and AI-assisted workflows could serve as a practical guide for AI adoption, reducing the labour-intensive research for innovation techniques to increase productivity and simplify BIM design coordination.

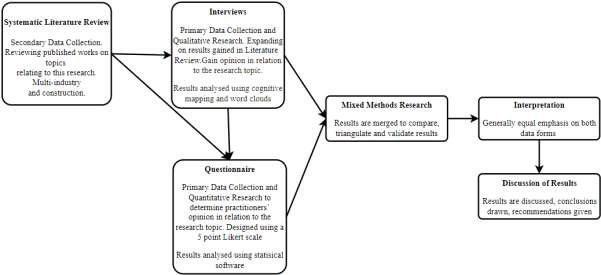

To achieve a comprehensive understanding of AI integration in clash management, this qualitative research employed a theory triangulation approachsummarised in Fig. 1, combining multiple theories to simultaneouslyleverage the strengths of different methods and mitigate their weaknesses. The methodology included: a literature review of peer-reviewed papers to identify gaps in traditional BIM clash management and explore potential AI tools; semi-structured and open-ended interviews with experienced BIM and Digital Construction stakeholders in Ireland and the United Kingdom to capture a holistic representation of the clash management process and detailed information about current AI knowledge; and follow-up focus groups to

Donnarummo and Hayes (2025), A Process Map integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI) into clash management

critique, refine, and validate the proposed Process Map, eliciting additional perspectives not initially considered by the researcher.

Figure. 1. Summary of how the research triangulates to gather and validate diverse perspectives

By integrating these research methodologies, this iterative approach allowed the intersection of theoretical knowledge with practical industry perspectives. The literature review established a theoretical foundation, while interviews provided industry -specific insights that, through thematic analysis, identified key patterns forming the basis of the Process Map, which was further refined through focus groups to ensure its validity.

The findings from the coded, interpreted, and visually interconnected data collected through interviews, following a thematic analysis process, are summarised below:

The first set of topic-based interview questions focused on the participants’ experience with clash management in large -scale residential projects and the types of clashes often encountered in these buildings. Most of the responses focused on common clashes between different disciplines and where they tend to happen. Clashes involving MEP were mentioned by seven participants, occurring both between MEP and other disciplines, such as structure and architecture, as well as among MEP systems themselves.

In terms of building locations, recurring areas where clashes are usually found include corridors and ceiling voids, as reported by four interviewees. Other common areas included lift lobbies, plant rooms, risers, and roofs.

A few participants noted these clashes are not unique to residential buildings, as conflicts are similar across building types. All participants agreed that standardisation of these types of buildings is highly beneficial since similar floor plates and stacked apartment units make the clash management process quicker. Once one level is coordinated and all clashes are resolved, the same reference level can be copied to

Proc. of the CitA BIM Gathering Conference2025, November 6th 2025, Dublin Ireland

other levels. However, four professionals noted that bigger concerns arise when the typical layout changes, such as on top floors or basements.

The following set of interview questions relate d to understanding the current clash avoidance, detection, and resolution workflows according to the BIM and digital construction stakeholders.

Clash avoidance primarily occurs through collaboration in Common Data Environments such as ACC or BIM 360, where BIM managers communicate prevention strategies based on prior experience and lessons learned, although some participants noted these documents are not always reviewed by designers. Clash detection extends beyond automated testing, involving manual filtering, grouping, and visual inspection of models, with early prioritisation guided by the number of disciplines involved, cost, impact to surrounding areas, level of importance, and project programme. Experience also informs the focus on critical zones such as MEP, structural, and fire protection areas. Finally, clash resolution typically takes place during coordination meetings, where responsibilities are discussed and assigned across disciplines, supported by tools such as Plannerly and clash matrices to track and monitor progress.

Based on feedback from all the interviews, low-quality models from design teams were highlighted as a major issue. These models often contained errors and inconsistencies attributed to factors such as vague or late client decisions, poor quality checks, an d inexperienced modelling staff. Another challenge, mentioned by three participants, concerns the lack of information included, often due to consultants being brought into the project too late or models not aligning with BIM guidelines.

Additionally, all interviewees noted that manual processes were a major source of inefficiency. Tasks like creating and assigning issues, applying clash rules, and developing reports were still done manually, slowing progress and increasing risk.

The stakeholders also mentioned that significant time was spent going through all the detected clashes to ensure they were actual issues and classifying and grouping them. Particularly when it comes to conflicts irrelevant in design phases, when less experienced staff lacked the knowledge to filter out low -priority clashes, it often resulted in an overwhelming volume of clashes and wasted time in coordination meetings.

In terms of inefficiencies, data was sometimes poorly recorded, making it difficult to track previous decisions, issue resolution, or the biggest cost and impact of unresolved or undetected issues over time. Interestingly, it was noted by two interviewees that, despite many similar large-scale residential projects having been delivered in the past, information from previous coordination efforts was often not properly recorded or carried forward. As a result, valuable lessons and decisions were lost, reducin g the opportunity to improve efficiency in future projects.

Additionally, a lack of engagement was highlighted by four of the interviewees. Design teams were not actively attempting to avoid or resolve clashes, and in some cases, both clients and design teams struggled to fully grasp the visual impact of their

Proc. of the CitA BIM Gathering Conference2025, November 6th 2025, Dublin Ireland

decisions on the model and overall coordination. On top of that, models received for coordination were sometimes outdated due to designers not sharing latest versions.

Regarding the interview findings related to addressing the identified inefficiencies in clash management using AI, interviewees shared a range of ideas about the potential to automate repetitive tasks, mainly related to clash detection – filtering, issues classification, issues creation, assigning responsibilities, and understanding priorities. Seven specialists expressed strong interest in using AI to support decision -making, especially for less experienced staff, and to optimise coordination between design teams and BIM managers through improved modelling understanding and communication. Participants also suggested that AI could be used to identify priority areas based on cost, impact, unassigned clashes, or zones with high issue concentrations from lessons learned, while certain clashes could be automatically deprioritised at specific project stages, such as perpendicular MEP services pass ing through walls without openings during early design phases.

When discussing AI techniques, participants mainly highlighted AI’s ability to understand and generate written information, as well as to respond to pre -defined knowledge-based rules inputted by experts. A summary containing the main techniques pointed out by the interviewees is listed below:

Machine learning enables systems to discover hidden patterns in large datasets and use those insights for automated decision -making. This makes processes more objective, data-driven, and less dependent on manual observation or specialist judgement (Pan and Zhang, 2021). According to the interviewees and as noted in the clash detection section of the proposed Process Map (Figure 3), ML could be trained on data from previous projects to become an AI -agent that recognises patterns in clash types to group and classify them and go beyond this by automatically assigning issues based on data extracted from the project clash matrix.

Additionally, ML has the potential to identify common problems to understand where clashes are likely to occur, produce project-specific clash matrices and create lessonslearned models by analysing past data where the clashes were coordinated and resolved. However, although machines that are trained from previous projects were viewed as valuable, six participants noted that this information is often not properly recorded and that huge amounts of data from past clashes would be needed to identify patterns and predict where clashes are likely to occur.

Knowledge-based rules use a symbolic representation of domain knowledge (e.g. experience of experts and previous cases) to build knowledge -based systems rather than using complex algorithms. Specifically, experts are interviewed to retrospectively share their experiences in similar cases, such as how to determine the types of BIM clashes to find an applicable action or conclusion (Zhang et al., 2022)

According to the interviews, knowledge -based systems are seen as more promising techniques when compared to machine learning. This is largely because clash detection involves rule-based decisions that might need to be flexible depending on the type of project and stage, such as identifying false positives, assigning priority levels, or determining which clashes can be ignored based on known previous input,

Proc. of the CitA BIM Gathering Conference2025, November 6th 2025, Dublin Ireland

(2025),

as these decisions typically do not require large volumes of previous data or interpretation. As an interviewee noted, this kind of automation does not require subjective judgement; it is often a simple yes or no decision, but there is still a need for an expert to input the rules, as illustrated in the Process Map proposed in this research.

When it comes to improving accuracy and efficiency in clash management, six interviewees recognised that the predefined rules could help distinguish between relevant and irrelevant clashes, such as minor overlapswhich are well-known in practice not to require action, allowing teams to focus on meaningful issues.

Finally, three stakeholders mentioned the potential for knowledge -based rules to understand the priority areas that are to be checked in a given project time, and also the priority clashes that are to be resolved considering programme, cost and impact.

Although participants did not explicitly reference genetic algorithms, their insights aligned with the core principles of this technique to address its use in resolution optimisation based on multiple objectives that are to be considered when adjusting elements to resolve a clash (e.g. cost, impact, priority, design intent preservation). According to Yüksel et al. (2023), during the design phase of engineering design, GAs can be used in the decision-making and evaluation process, and compared to classical methods to evaluate best clash solutions, they can save time and labour.

In line with this, an interviewee also emphasised the value of AI to explore a wide range of design alternatives to identify solutions that balance multiple objectives to understand the best design strategies to avoid clashes, for example, identifying optimal modelling choices to position elements that minimise the likelihood of conflicts. This approach was considered as an AI tool to support decisions in the clash resolution section of the suggested process map.

Natural Language Processing (NLP) drives computers to process, explore, and interpret language-related data in the form of text and words. It supports a human -like understanding of language, allowing for more accurate content analysis and reducing ambiguity in interpretation (Pan and Zhang, 2021).

According to six interviewees, a possible way to simplify the clash management process would be to use AI to provide a clash summary and classification, making it easier for everyone involved in the process to understand the nature and context of clashes. As mentioned by one of the BIM professionals, tools like ChatGPT could potentially look at an image, understand what is clashing, and provide useful descriptions. This kind of tool could help go through large lists of clashes and make it easier to prioritise them and share the right information with the right people.

Also, four participants mentioned that automating clash reports , including descriptive titles, comments, and responsible disciplines to solve the issue , would help to save time and reduce the burden of manual documentation.

Overall, NLP was viewed not simply as a reporting tool but as a communication technique to address the gap between raw detected clash data and meaningful project insights. From this perspective, these AI -based solutions are identified as relevant during all clash management stages due to their potential to support humans in interpreting, summarising, and generating text data.

Proc. of the CitA BIM Gathering Conference2025, November 6th 2025, Dublin Ireland

(2025),

Additionally, other tools and techniques mentioned by the interviewees to optimise the clash management workflows were the possibility for AI plug -ins to be connected to existing software that professionals are already familiar with . This includes live clash detection while modelling to avoid the overwhelming amount of conflicts in the models, and immersive technologies like Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality to support decision-making, particularly for less experienced team members.

Despite the potential benefits of AI in clash management identified by the interviewees, this research also sought to understand the barriers to adopting AI in BIM coordination workflows. These barriers are summarised in the pie chart in Fig. 2 and further explained below.

Figure. 2. Significant barriers to AI adoption in BIM Coordination workflows according to stakeholders’ interviews

Four participants noted that their companies are still not using AI for clash management, specifically due to issues such as poor engagement, lack of reliable datasets, and concerns about complexity - especially in terms of tasks relying on human judgement which are not easy for AI to interpret. Participants explained that many clashes require discussions between different disciplines, consideration of project priorities, and sometimes even negotiation between teams. Because projects are always different, it is hard to create one-solution that could suit all the projects.

This complexity also connects to the cost of using AI since creating or implementing AI tools that can deal with clash management tasks can be expensive. Smaller companies may not have the budget or the right people to support this technology. For them, the high costs and the need for technical knowledge make it even harder to start using AI in their projects.

Concerns were also raised around taking responsibility in the context of fully AI automation for specific tasks, with an interviewee commenting that fully automated solutions are unlikely to be adopted for complex tasks and decisions because accountability must be assigned to a human rather than a tool when errors occur. Also, trust in the technology itself was mentioned by four participants, especially in cases where results have not been proven or where data security could be at risk.

In summary, the findings informed the development of the Process Map by identifying specific clash management stages where AI could be effectively integrated, with

Proc. of the CitA BIM Gathering Conference2025, November 6th 2025, Dublin Ireland

Donnarummo and Hayes (2025), A Process Map integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI) into clash management workflows

pathways for improvement and automation. Interview feedback validated the sequence and practicality of the process. The initial map, based on the researcher’s interpretation, was refined through focus groups , with stakeholders previously interviewed, providing feedback on its structure and usefulness.

Participants noted that rather than an all-encompassing AI solution, the map’s strength lies in helping organisations identify and refine specific tasks where AI tools or AI agents can be applied, instead oftrying to optimise every aspect of the clash management process at once. In this sense, the proposal was seen as more viable when presented as a modular framework with targeted tools and techniques. Another critical discussion was in terms of limiting the process map to large -scale residential projects. One participant noted that AI is highly customisable and the framework can be adapted to various project types.

Additionally, three participants noted that the process map itself helped them save time during their own research into AI applications. The clarity and detail of the diagram made it easier to understand the areas where specific AI agents and tools could be introduced in clash management workflows to address their needs. One participant even mentioned that a few techniques presented in the meeting have already begun to be tested within their company to optimise coordination processes. Based on the focus groups insights, the proposed Process Map was revised and finalised as an outcome of this research, as illustrated in Fig. 3 below.

To use the Process Map effectively, teams should begin by pinpointing which clash management stage - avoidance, detection, or resolution - presents the greatest

Proc. of the CitA BIM Gathering Conference2025, November 6th 2025, Dublin Ireland

challenges in their coordination context. Next, they select specific tasks that are timeconsuming, laborious, or low accuracy in their workflows. Using the integration points marked by gear icons, teams can identify the most suitable AI -driven technique to improve that task and understand whether the solution would function as a fully automated AI tool or as an AI agent to support decision-making.

During early project stages, teams can align their model coordination strategies with the top section of the Process Map prior to and during the modelling process, ensuring models are structured and classified in a way that supports data extraction for AI processing. At this point, the map guides teams to apply predictive AI tools that assess likely clash zones before full model deve lopment, allowing for clash avoidance rather than just detection or resolution.

In the detection section, the Process Map guides the coordination team through the preparation and execution of clash identification and analysis. Automated tools identify clashes, followed by filtering to remove irrelevant or low -priority issues. AI-supported techniques can assist in grouping, prioritising, and assigning clashes to responsible teams, ensuring only actionable issues move to resolution

In the resolution stage, activities focus on addressing clashes in a coordinated and optimised manner, based on factors such as model ownership, clash impact, design intent, and cost. AI-driven tools can help flag which clashes require immediate attention and which can be temporar ily accepted. Once clashes are detected and prioritised, AI agents can proactively suggest adjustments by analysing patterns from past coordination cycles and BIM experts’ inputs.

In the final stages of the process, AI can assist in tracking resolution actions, ensuring that accepted clashes are documented and monitored, and decisions regarding responsibilities are recorded. The cycle repeats weekly or bi -weekly to confirm that agreed changes are implemented and to check for new clashes that should be addressed in subsequent cycles. Crucially, the workflow is not linear; it includes iterative loops that ensure clashes are managed as the project evolves.

Overall, the Process Map is designed to be a modular and adaptable tool that helps coordination teams focus on the most problematic areas within clash management rather than on all activities involved in the process. By identifying the most labourintensive activities and aligning them with suitable AI techniques, teams can make informed decisions about where automation or AI support can bring value.

This paper presented an investigation to develop a Process Map to be used as a practical guide for BIM specialists to identify pathways for integrating AI -based solutions within their existing workflows. The suggested approach was explored to indicate actionable strategies for AI techniques to be implemented to address specific coordination needs during the design phase of projects. This responds to growing interest in the applicability of AI to enhance BIM coordination processes, as highlighted by Zhang et al. (2022), who emphasise the lack of existing knowledge in research and practice combining BIM and AI.

The research identified that appropriately targeted automated agents and humanassisted tools could address inefficiencies in clash management, including manual filtering, rule creation, delayed decisions, labour -intensive issue assignment, and irrelevant clashes. Techniques such as machine learning, knowledge -based rules,

Proc. of the CitA BIM Gathering Conference2025, November 6th 2025, Dublin Ireland

Donnarummo and Hayes (2025), A Process Map integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI) into clash management

genetic algorithms, and natural language processing were identified as supporting automation and improving consistency in BIM coordination. There are limitations to this research; the Process Map was not tested in live projects, making it a strategic framework rather than an industry -validated solution. Future research should focus on empirical testing to evaluate its practical effectiveness and scalability, as well as exploring adoption barriers and potential over-reliance on automated assumptions.

References

Akhmetzhanova, B., Nadeem, A., Hossain, M.A., Kim, J.R., 2022. Clash Detection Using Building Information Modeling (BIM) Technology in the Republic of Kazakhstan. Buildings 12, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12020102 [Accessed at 20/04/2025]

Chahrour, R., Hafeez, M.A., Ahmad, A.M., Sulieman, H.I., Dawood, H., RodriguezTrejo, S., Kassem, M., Naji, K.K., Dawood, N., 2021. Cost -benefit analysis of BIM-enabled design clash detection and resolution. Constr. Manag. Econ. 39, 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2020.1802768 [Accessed at 21/04/2025].

Hsu, H.-C., Chang, S., Chen, C.-C., Wu, I.-C., 2020. Knowledge-based system for resolving design clashes in building information models. Autom. Constr. 110, 103001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2019.103001

Hu, Y. and Castro-Lacouture, D. (2018) ‘Clash Relevance Prediction Based on Machine Learning’, Journal of Computing in Civil Engineering, 33(2), p. 04018060. Clash Relevance Prediction Based on Machine Learning | Journal of Computing in Civil Engineering | Vol 33, No 2[Accessed at 20/04/2025]

Hu, Y., Xia, C., Chen, J., Gao, X., 2023. Clash context representation and change component prediction based on graph convolutional network in MEP disciplines. Adv. Eng. Inform. 55, 101896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2023.101896 [Accessed at 20/04/2025]

Lin, W.Y., Huang, Y.-H., 2019. Filtering of Irrelevant Clashes Detected by BIM Software Using a Hybrid Method of Rule -Based Reasoning and Supervised Machine Learning. Appl. Sci. 9, 5324. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9245324 [Accessed at 21/04/2025].

Liu, X., Zhao, J., Yu, Y., Ji, Y., 2024. BIM-based multi-objective optimization of clash resolution: A NSGA-II approach. J. Build. Eng. 89, 109228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.109228 [Accessed at 21/04/2025].

Luo, S., Yao, J., Wang, S., Wang, Y., Lu, G., 2022. A sustainable BIM -based multidisciplinary framework for underground pipeline clash detection and analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 374, 133900.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133900 [Accessed at 21/04/2025].

Pan, Y., Zhang, L., 2021. Roles of artificial intelligence in construction engineering and management: A critical review and future trends. Autom. Constr. 122, 103517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2020.103517 [Accessed at 21/04/2025].

Pärn, E.A., Edwards, D.J., Sing, M.C.P., 2018. Origins and probabilities of MEP and structural design clashes within a federated BIM model. Autom. Constr. 85, 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2017.09.010 [Accessed at 21/04/2025].

Proc. of the CitA BIM Gathering Conference2025, November 6th 2025, Dublin Ireland

Donnarummo and Hayes (2025), A Process Map integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI) into clash management workflows

Pérez-García, A., Martín-Dorta, N., Aranda, J.Á., 2024. Enhancing BIM implementation in Spanish public procurement: A framework approach. Heliyon 10, e30650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e30650 [Accessed at 21/04/2025].

Yüksel, N., Börklü, H.R., Sezer, H.K., Canyurt, O.E., 2023. Review of artificial intelligence applications in engineering design perspective. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 118, 105697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105697 [Accessed at 21/04/2025].

Zhang, F., Chan, A.P.C., Darko, A., Chen, Z., Li, D., 2022. Integrated applications of building information modeling and artificial intelligence techniques in the AEC/FM industry. Autom. Constr. 139, 104289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2022.104289 [Accessed at 21/04/2025].

Proc. of the CitA BIM Gathering Conference2025, November 6th 2025, Dublin Ireland

Taseen (Taz) Muhammad, taseenmuhammad2@hotmail.com

Atlantic Technological University Sligo

Colin Harte,colin.harte@atu.ie

Atlantic Technological University Sligo

Michael R. Curran, michael.curran@ul.ie

University of Limerick

Daniel Clarke Hagan,daniel.clarkhagan@atu.ie

Atlantic Technological University Sligo

Mary Catherine Greene,mary-catherine.greene@glenveagh.ie

Glenveagh Properties Plc

Abstract

This research critically examines the transformative impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies on construction practices, analysing their benefits, challenges, and ethical implications. A sequential mixed -methods approach integrates a literature review, semi-structured interviews, and a questionnaire survey. Results highlight AI’s potential to enhance project management, optimise resources, and improve safety through predictive analytics and real-time monitoring. Key challenges include high implementation costs, training demands, data security risks, and accountability concerns. Findings emphasise the need to balance efficiency with ethical considerations for sustainable growth. This work offers a novel integrative perspective, providing actionable insights for stakeholders adopting AI in construction management practices.

Keywords: Artificial Intelligence (AI), Construction Management, Digital Transformation.

1. Introduction

Construction is a dynamic activity which blends the attributes of expertise, experience, and efficiency. The integration of AItechnology in construction practices has enabled the industry to make significant strides in these areas, particularly in enhancing professional expertise, leveraging collective experience, and improving overall efficiency Regarded as the next potential frontier in the industry ( Pan and Zhang, 2023), AI has led to the creation of innovative tools such as AI drones (Choi et al., 2023) and more efficient procedures that have increased safety and quality. However, there are significant challenges including high implementation costs, extensive training requirements, and the need for government regulations(Taiwo et al., 2024) Expensive AI systems can limit access for small- and medium-sized firms (SMEs), while workforce upskilling demands considerable time and resources. Furthermore, the absence of robust regulatory frameworks creates uncertainty around accountability, data security, and ethical deployment.

As a result, this research study aims to analyse real-world applications and address implementation challenges to explore the practical implications of incorporating AI in construction practices in Ireland and the UK The rapid advancement of AI mak es research in this area both timely and essential. AI technologies offer significant potential to enhance project efficiency and productivity (Obiuto et al., 2024) by optimising scheduling, resource allocation, and decision -making, leading to substantial time and cost savings for construction firms and their clients. Additionally, AI-driven solutions such as real-time monitoring and predictive analytics contribute to safer work environments by minimising accidents and improving compliance with safety protocols(Musarat et al., 2024) Embracing AI also fosters innovation and competitiveness, positioning organisations at the forefront of technological progress in construction(Rane, 2023). Therefore, this research seeks to provide an understanding of both the opportunities and complexities of AI adoption, enabling construction professionals to make informed decisions that drive safer, more efficient, and innovative industry practices.

The integration of AI is transforming the construction industry, offering new opportunities for innovation, efficiency, and safety.Driven by labour shortages, the COVID-19 pandemic, and global sustainability objectives such as the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals which promote innovation, sustainable infrastructure, and responsible production , AI adoption is growing rapidly It is reshaping processes from project planning and predictive maintenance to safety management, supply chain optimisation, and Building Information Model ling (BIM) integration (Blanco et al., 2018; Gidiagba et al., 2024; Egwim et al., 2023). AI is defined as an area of computer science focused on developing machines capable of performing cognitive tasks that typically require human intelligence (Sarker, 2022; Mondal, 2020). Haenlein and Kaplan (2019) argue that its emergence from science fiction into real-world applications illustrates its rapid technological progression.

2.1Key Applications of AI in Construction

AI enhances planning by optimising resource allocation, sequencing, and schedule predictions. It supports integrated demand forecasting and production planning, reducing delays and improving coordination ( Blanco et al., 2018). AI-enabled predictive maintenance systems monitor equipment health in real -time, allowing for proactive interventions. This reduces downtime and extends asset lifespans (Edwards et al., 1998) Gidiagba et al. (2024) support that when combined with the Internet of Things (IoT), AI can predict failure patterns and automate maintenance schedules. Construction sites are inherently hazardous, and AI significantly enhances safety management. Machine learning algorithms process data from wearables and environmental sensors to identify risk patterns and prevent accidents (Abioye et al., 2021; Egwim et al., 2023). Predictive analytics enables early detection of unsafe conditions, thus improving site safety (Cain, 2023; Be ll, 2023). Regarding supply chains and logistics, Ivanova et al. (2023) argue that AI automates construction logistics by integrating sensor networks and intelligent control systems. This facilitates real-time monitoring of materials, reduces delays, and improves supply chain efficiency. Furthermore, AI complements BIM by improving data analysis, energy tracking, and visual analytics. Bouabdallaoui et al. (2021) highlight that BIM’s 3D modelling capabilities support stakeholder collaboration, while AI enhances its predictive and operational capabilities.

Proc. of the CitA BIM Gathering Conference2025, November 6th, 2025, Dublin Ireland

To meet the demands of an AI-enabled future, Levesque (2018) argues that education systems must evolve. Southworth et al. (2023) and Hié and Thouary (2023) agree that integrating AI into core curricula prepare s students for emerging job roles, ensuring a proactive and adaptable workforce . Long (2022) emphasises the need for interactive training, as these tools allow safe experimentation and faster upskilling (Oren, 2023) , but according to Illanes et al. (2018),large-scale retraining requires coordinated efforts across governments, academia, and industry.Construction remains one of the most hazardous industries (Baker et al., 2020), yet AI technologies are improving health and safety in various ways.Bell (2023) highlights the importance of p redictive analytics, with Cain (2023) supporting its ability toidentify high-risk patterns from previous accidents and near misses. However, Hovnanian et al. (2019) believe that the adoption of predictive analytics can pose challenges due to the variety and unpredictability of construction projects, and mid-project changes in progress-tracking systems.

In the field of robotics, the unstructured and unpredictable character of building projects has traditionally restricted the usage of robots. Nonetheless, repetitive and predictable operations such as welding, tiling and bricklaying can be maximised using robotics. Wearable technologies are becoming commonplace on -site, and examples such as smart helmets and sensor vestsallow for real-time monitoring of workplace conditions and health (Farhadi, 2023). However, issues remain about data quality and trust, raising concerns about the device’s reliability (Canali et al., 2022). Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) provide realistic simulations for emergency response and equipment handling, allowing workers to practice real-world scenarios in risk-free settings (Yoo et al., 2023)

The rapid development of AI requires strong regulations to oversee its use, and some governance frameworks have emerged worldwide to ensure responsible AI deployment. The European Union (EU) (2024) AI Act is the world’s first comprehensive AI law classifying systems by risk and promotes trust, transparency, and public safety. Canada’s AI and Data Act (AIDA) addresses high-impact AI systems and establishes oversight through an AI and Data Commissioner (Medeiros and Beatson, 2022), and globally, the United Nations (UN) (2024) advocate for inclusive and ethical AI usage. Cath (2018) argues that ethical governance remains a key element ofAI policy, concentrating on crucial concerns such as fairness, transparency and product distribution. As AI systems become integral to construction, cybersecurity risks grow . Bradley (2024) reveals that many firms are unprepared and ill -equipped for cyberattacks, with a startling disparity between awareness and action.AI systems can be prone to breaches if resilient cybersecurity measures are not implemented, thus, calls for robust legal and ethical frameworks to mitigate these threats have been made (Humphreys et al., 2024). Therefore, further research in this area isnecessary.

While the literature demonstrates rapid progress in AI applications for planning, safety, and logistics, significant gaps remain in understanding how these technologies can be systematically integrated into everyday construction practices, particularly within an Irish and UK context. Existing studies often examine AI benefits in isolation rather than through a combined operational, managerial, and ethical lens. Consequently, this research seeks to bridge that gap by exploring the real -world challenges and opportunities of AI adoption across multiple stakeholder perspectives in the both the Irishand UK construction industries.

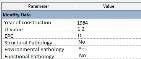

According to Clarke-Hagan et al. (2018) construction managers who undertake research to successfully solve the problems faced by the construction industry need to adopt a strong methodological approach, that considers both ontological and epistemological viewpoints.As a result, this study employs a sequential mixedmethods approach to investigate the adoption and impact of AI in construction management. Mixed methods research was deemed appropriate for capturing both measurable trends and nuanced, lived ex periences of industry professionals (MolinaAzorín, 2016; Shorten and Smith, 2017). The design enabled triangulation across qualitative and quantitative data sources, enhancing the reliability and depth of findings. Following an informative literature review, the qualitative component consisted of three semi-structured interviews with construction professionals based in Ireland and the UK. Participants were selected using purposive and convenience sampling, focusing on roles directly involved in AI implementation and project delivery, and included a Project Manager, Graduate Engineer and BIM Coordinator. The Project Manager provides strategic and operational insight into AI adoption at the site and project level, the Graduate Engineer represents emerging am navigating AI-enabled workflows, and the BIM Coordinator offers technical expertise on digital modelling and AI-integrated BIMprocesses. Collectively, these roles capture perspectives across managerial, technical, and early-career practitioner viewpoints. Semi-structured interviews were selected for their flexibility in exploring complex themes (De Jonckheere and Vaughn, 2019). Interviews were transcribed and analysed thematically using an inductive coding approach, revealing emerging themes including automation anxiety, regulatory uncertainty, and skills transition.

To complement the interviews, the quantitative component consisted of a structured questionnaire disseminated online to professionals across the Irish and UK construction sectors Out of the 52 respondents, 17 were based in Ireland, 15 in the United Kingdom, 10 in Canada, and the remaining 10 were located across various countries in Europe. Fitzpatrick et al. (2024) support the use of online questionnaires due to increased response rates through ease of access, and greater individual anonymity compared to face-to-face interviews.Fifty valid responses were collected , with the anonymous survey primarily reaching site engineers, quantity surveyors, and recent graduates through targeted industry contacts, ensuring practical insights while maintaining respondent confidentiality and anonymity. While the qualitative interviews included a BIM Coordinator to capture AI-integrated digital workflow perspectives, the survey did not specifically target BIM professionals. The survey included closed and Likert-scale questions exploring AI familiarity, current implementation, perceived risks, and anticipated benefits. Descriptive statistical methods were applied to identify key trends. According to Albers (2017), quantitative data is essential for measuring adoption levels and identifying patterns that support generalisability This methodological design allowed the study to combine the detailed personal insights of practitioners with broad industry-wide perspectives. By integrating qualitative depth with quantitative reach, the research provides a well-rounded foundation for assessing AI’s transformative role in construction management

To provide a clear and succinct overview, the results have been summarisedwith key findings illustrated in Tables 1 and 2 The tables outline the main insights gathered from each data source, highlighting core themes and participant responses related to the implementation, perception, and impact of AI within the construction industry The

research revealed three major challenges impacting the adoption of AI in construction: graduate capability, regulatory gaps, and data security concerns, alongside two dominant benefits: enhanced project efficiency and improved safety. Each is explored through integration of interviews, survey data, and literature Three construction professionals participated in semi-structured interviews: Interviewee A, a Project Manager; Interviewee B, a Graduate Engineer; and Interviewee C, a BIM Coordinator. These participants were selected to capture perspectives across managerial, technical, and early-career roles directly involved in AI adoption within construction projectsacross Ireland and the UK.

4.1.1

AI graduate capabilities and education gaps were widely reported across both interviews and survey responses. Interviewees expressed concern about higher education’s ability to equip students with practical AI competencies, particularly in data analytics and machine learning. Interviewe e A called for ‘programmatic reviews’ of construction management higher education pr ogrammes, while Interviewee B advocated for greater industry exposure and hands -on training and practical experience Similarly, Interviewee C emphasised the importance of educational changes in preparing students for a labour market increasingly dominated by AI, arguing that adaptability and AI competency are critical. The literature reinforces these views, as Southworth et al. (2023) and Hié and Thouary (2023) urge the integration of AI into core education program mes, while Levesque (2018) argues curricula must be adaptive and evolve to prepare students not only for today’s demands, but for future roles that AI will create. Survey results echoed these conc erns: 65% of respondents did not believe graduates possessed adequate AI -related skills for the construction industry, and 94% agreed that educational institutions must do more to prepare students. To address this gap, stronger academic-industry partnerships are essential, along with AI-focused curricula that combine theoretical and applied learning. Ongoing continual professional development and upskilling options can help to ensure that the workforce remains competent in the face of rapid advancements in AI technology

Regulatory frameworks were another pressing concern. Interviewees were united in emphasising the lack of clear AI regulation, particularly regarding ethical use and misinformation. Interviewee A voiced concerns over AI’s ability to generate plausible but false content, warning that unregulated AI could undermine public trust. Interviewee B noted the importance of regulations in setting ethical standards that respects human rights, and Interviewee C argued for the critical role of regulations in directing both local and global development of AI, ensuring that deployment across industries like construction remains safe and compliant with building codes. These perspectives are aligned with wider policy efforts. The EU (2024) AI Act has been recognised as a pioneering legal framework designed to promote trustworthy AI , while the UN (2024) has called for global cooperation to mitigate risks.Survey results reflect a similar consensus: 79% of participants rate government regulation as extremely important to ensure ethical and safe AI deployment. This highlights a shared industry concern about the consequences of unregulated AI development and supports the growing demand for legal structures that can keep pace with technological change.

As AI becomes increasingly integrated into construction operations, data security has emerged as a critical issue. Interviewee A describe d current AI data use as ‘unregulated’, warning of the risks associated with rapid AI evolution. Interviewee B highlighted the need for proactive security strategies, including encryption and transparent policies, to build trust with users and clients. The literature supports these concerns, with Bradley (2024) identifying a significant gap between the growing cybersecurity risks of AI and the weak protective measures adopted by many firms. Hackers areexploiting flaws in AI systems, while Brundage et al. (2020) warn of AI’s dual-use potential which optimises both construction tasks and cyberattacks. These concerns were validated by the survey as 65% of participants expressed serious worry about AI-related data breaches. As projects increasingly rely on AI -powered tools and digital infrastructure, companies must prioritise cybersecurity frameworks and promote a culture of ethical, responsible AI u se to strengthen against attack.

THEME

SUMMARY OF INSIGHTS FROM INTERVIEWS

AI Understanding AI is widely recognised as transformative but still misunderstood; seen as both promising and potentially disruptive.

Integration and Use Cases

Perceived Benefits

Safety Enhancements

Predictive Maintenance

Supply Chain Optimisation

Workforce Preparation

Ethical Concerns

Implementation Barriers

Applied in areas like remote site walk-throughs, predictive analytics, satellite imagery, and AI chatbots.

Improved efficiency, risk management, safety, design accuracy, and client collaboration.

Used for facial recognition, real-time site access control, Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) monitoring, and hazard detection.

Recognised for its future role in cost-saving and reducing emergency repairs; but not fully deployed yet across all sectors.

Applied for material prediction, stock control, and sustainability tracking.

Emphasis on continuous learning, industry collaboration, and education reform to prepare future graduates.

Risks include job displacement, data privacy, and unregulated AI development. Call for accountability and strong governance.

High costs, lack of regulation, limited technical skill, and distrust remain major obstacles.

Sector Comparison AI adoption in construction seen as slower compared to healthcare due to SME constraints and limited incentives.

Government and Regulation

Consensus on need for international standards, investment, and targeted incentives to support responsible AI adoption.

4.2.1 Project Efficiency

One of the most consistent themes in both the interviews and literature was AI’s role in enhancing project management efficiency. Interviewee A highlight ed how AI supports early decision-making by providing data visualisations that improve feasibility assessments, saving time and money. Interviewee B emphasised AI's role in optimising resource allocation and automating routine tasks, which significantly reduces downtime and improves operational efficiency. Interviewee C shared a specific application of AI in satellite imaging for accurate mapping, which has streamlined planning and execution phases, notably in measuring roofing and facade

materials. This precision in planning directly contributes to cost savings and waste reduction, marking a significant enhancement in project efficiency. AI’s influence on cost, quality, and time is central to project success, and Matel et al. (2022) note A I’s ability to produce more accurate cost estimates. Furthermore, Mohapatra et al. (2023) link AI’s predictive capabilities to improved quality outcomes, while Ivanova et al. (2023) and Datta et al. (2024) report AI’s effectiveness in expediting planning a nd reducing risk during the pre-construction phase. Regarding the survey results, 79% of respondents believed AI is ‘extremely effective’ at improving efficiency and reducing costs. Moreover, 75% agreed AI contributes significantly to sustainability and construction quality. Despite these benefits, stakeholders must also remain alert to challenges such as data quality, automation risks, and implementation costs.

QUESTION TOPIC

AI Familiarity

Premature Adoption Concern

Job Displacement

Data Security Concerns

AI and Safety

Graduate AI Skills Readiness

Need for AI Education

Importance of Government Regulation

Ethical Governance Role of Government

Incentives for AI Integration

AI and Project Efficiency (Cost & Delay Reduction)

AI and Sustainability

Overall Impact of AI on Construction

KEY FINDINGS

89% had used AI technology in some form.

65% disagreed AI was released too early; 14% felt it was.

38% saw job loss as likely; 44% were neutral.

89% expressed concern about AI-related data breaches.

83% believed AI significantly enhances safety in construction.

77% felt graduates lack adequate AI skills for the industry.

94% agreed more dedicated AI programs are needed.

94% said regulation of AI is crucial; none disagreed.

90% supported stronger state-led ethics in AI.

92% supported financial or regulatory incentives for AI adoption.

87% said AI would be effective or very effective in improving cost control and reducing delays.

89% believed AI enhances project quality and sustainability.

90% viewed the overall impact as positive or very positive; only 4% reported a negative view.

AI has demonstrated a clear role in improving health and safety practices on-site, with Interviewee A discussing the example of using AI-driven facial recognition during the COVID-19 pandemic to manage site access and enforce social distancing .Interviewee B pointed to computer vision systems used to monitor personal protective equipment (PPE) compliance, as real-time monitoring supports immediate corrective action s. Interviewee C focused on AI’s predictive analytics in roofing, which can identify structural risks and potential dangers before they materialise. This aligns with findings from Baker et al., (2020) who note that AI has already contributed to reduced injury rates in construction by detecting risks before they become apparent to human supervisors. Predictive analytics are enabling earlier interventions by identifying patterns of risk (Cain, 2023; Bell, 2023), and robotics and wearables also support safer operations by automating dangerous tasks and monitoring worker conditions to

prevent accidents (Farhadi, 2023). The survey results are mostly positive regarding AI's role in improving safety, with 73% of respondents viewing AI as ‘extremely effective’ at enhancing safety, and 7 5% supported measures to accelerate its integration. However, some challenges persist , as Hovnanian et al. (2019) warn that unpredictable site conditions can affect AI accuracy, and there is an ongoing need to address legal and cultural resistance to emerging safety technologies.

This exploratory study aimed to examine if AI is transforming construction management practicesin Ireland and the UK, with a focus on measurable impacts on project efficiency, site safety, planning accuracy, and resource management. Using a mixed-methods approach including a literature review, semi-structured interviews, and a questionnaire survey, the research found that AI is increasingly influencing core construction functions. For example, 79% of survey respondents indicated that AI is highly effective in improving project efficiency, 75% reported it significantly enhances safety, and 77% felt that current graduates lack adequate AI -related skills for industry needs. Tools such as predictive analytics and automated scheduling systems support earlier and more informed decision-making, improve coordination, and reduce delays and material waste. Real-world applications, including satellite imaging and sensorbased monitoring, are contributing to measurable improvements in project planning and execution. Technologiessuch as wearables, computer vision, and predictive analytics are also being used to detect hazards, monitor compliance, and prevent accidents on-site, improving health, safety and welfare.

However, despite these benefits, adoption remains constrained by several critical challenges. Skills gaps between graduates and industry expectations limit workforce readiness, with many graduates lacking hands -on experience with AI tools and companies having limited capacity to deliver in-house AI training. Higher education institutions must update curricula to integrate AI more comprehensively, while companies should invest in continuous professional development. Regulatory uncertainty and ethical oversight also pose significant barriers. Participants highlighted the absence of clear legal frameworks for issues such as data ownership, algorithmic bias, and automated decision -making. While initiatives like the EU AI Act represent progress, further industry engagement is needed to develop practical, enforceable standards that reflect the realities of construction management practices.

Data security remains a dominant concern, and as AI relies heavily on project and personnel data, the risk of cybersecurity breaches remains high. Interviewees emphasised embedding robust security measures such as encryption, regular audits, and clear data usage policies throughout the AI lifecycle to build trust and ensure compliance. The financial burden of AI implementation, particularly for SMEs, further limits adoption. Without targeted funding, public -private partnerships, or staged investment models, smaller companies risk being excluded from AI's potential benefits. Although this study was conducted within the Irish and UK construction sectors, the findings provide insights that are broadly applicable to construction management practices internationally. In conclusion, AI is demonstrating measurable improvements in key construction metrics such as efficiency, safety, and planning accuracy, but its transformative potential depends on concurrent investments in workforce capability, regulatory frameworks, ethical governance, and infrastructure. The key contribution of this study lies in highlighting both the benefits of AI adoption and the conditions necessary to ensure itsethical, effective, and inclusive integration into construction management practice in Ireland, the UK and beyond.

Proc. of the CitA BIM Gathering Conference2025, November 6th, 2025, Dublin Ireland

References

Abioye, S.O., Oyedele, L.O., Akanbi, L., Ajayi, A., Delgado, J.M.D., Bilal, M., Akinade, O.O. and Ahmed, A., (2021). Artificial intelligence in the construction industry: A review of present status, opportunities and future challenges. Journal of Building Engineering, 44

Albers, M.J., (2017). Quantitative data analysis – In the graduate curriculum. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication , 47(2), pp.215-233.

Baker, H., Hallowell, M.R. and Tixier, A.J.P., (2020). AI -based prediction of independent construction safety outcomes from universal attributes. Automation in Construction, 118.

Bell, R., (2023), How contractors are using AI and analytics to reduce risk and improve safety, available at: https://blogs.oracle.com/construction -engineering/post/aianalytics-improve-safety

Blanco, J.L., Fuchs, S., Parsons, M. and Ribeirinho, M.J., (2018), Artificial intelligence: Construction technology's next frontier. The Building Economist, (Sep 2018).

Bouabdallaoui, Y., Lafhaj, Z., Yim, P., Ducoulombier, L. and Bennadji, B., (2021). Predictive maintenance in building facilities: A machine learning -based approach. Sensors, 21(4).

Bradley, P.J., (2024), Four Takeaways from the McKinsey AI Report, available at: https://www.tripwire.com/state-of-security/four-takeaways-mckinsey-ai-report

Brundage, M., Avin, S., Clark, J., Toner, H., Eckersley, P., Garfinkel, B., Dafoe, A., Scharre, P., Zeitzoff, T., Filar, B. and Anderson, H., (2018). The malicious use of artificial intelligence: Forecasting, prevention, and mitigation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.07228.

Cain, D., (2023), Construction Safety using AI, available at: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/ai-construction-safety-david-cain/

Canali, S., Schiaffonati, V. and Aliverti, A., (2022). Challenges and recommendations for wearable devices in digital health: Data quality, interoperability, health equity, fairness. PLOS Digital Health, 1(10), p.e0000104.

Cath, C., (2018). Governing artificial intelligence: ethical, legal and technical opportunities and challenges. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 376(2133), p.20180080.

Choi, H.W., Kim, H.J., Kim, S.K. and Na, W.S., (2023). An overview of drone applications in the construction industry. Drones, 7(8), p.515.

Clarke-Hagan, D., Spillane, J. and Curran, M., (2018), 'Mixed Methods Research: A Methodology in Social Sciences Research for the Construction Manager’, in proceedings of annual RICS COBRA Conference, 23 -24 April 2018, London, England, Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors

Datta, S.D., Islam, M., Sobuz, M.H.R., Ahmed, S. and Kar, M., (2024). Artificial intelligence and machine learning applications in the project lifecycle of the construction industry: A comprehensive review. Heliyon.

DeJonckheere, M. and Vaughn, L.M., (2019), Semi structured interviewing in primary care research: a balance of relationship and rigour. Family medicine and community health, 7(2), p.e000057.

Proc. of the CitA BIM Gathering Conference2025, November 6th, 2025, Dublin Ireland

Edwards, D.J., Holt, G.D. and Harris, F.C., (1998). Predictive maintenance techniques and their relevance to construction plant. Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering, 4(1), pp.25 -37.

Egwim, C.N., Alaka, H., Demir, E., Balogun, H., Olu -Ajayi, R., Sulaimon, I., Wusu, G., Yusuf, W. and Muideen, A.A., (2023). Artificial intelligence in the construction industry: A systematic review of the entire construction value chain lifecycle. Energies, 17(1), p.182.

European Union, (2024). Shaping Europe’s digital future, available at: https://digitalstrategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/regulatory-framework-ai

Farhadi, F., (2023), Top 12 Wearable Technology in Construction Industry, available at:https://neuroject.com/wearable-technology-in-construction/

Fitzpatrick, C, Curran, M R, Clarke-Hagan, M , Spillane, J P and Bradley, J.G., (2024) Is a Compressed Workweek Viable for Work -Life Balance in the Irish Construction Industry? An Exploratory Study into a Four -Day Week, In: Thomson, C and Neilson, C.J., (Eds) Proceedings of the 40th Annual ARCOM Conference, 2-4 September 2024, London, UK, Association of Researchers in Construction Management, 309-318.

Gidiagba, J.O., Nwaobia, N.K., Biu, P.W., Ezeigweneme, C.A. and Umoh, A.A., (2024), Review on the evolution and impact of iot -driven predictive maintenance: assessing advancements, their role in enhancing system longevity, and sustainable operations in both mechanical and electrical realms. Computer Science & IT Research Journal, 5(1).

Haenlein, M. and Kaplan, A., (2019). A brief history of artificial intelligence: On the past, present, and future of artificial intelligence. California management review, 61(4), pp.5.

Hié, A. and Thouary, C., (2023), How AI Is Reshaping Higher Education, available at: https://www.aacsb.edu/insights/articles/2023/10/how-ai-is-reshaping-highereducation

Hovnanian, G., Kroll, K. and Sjödin, E., ( 2019), How analytics can drive smarter engineering and construction decisions, available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/operations/our-insights/how-analyticscan-drive-smarter-engineering-and-construction-decisions

Humphreys, D., Koay, A., Desmond, D. and Mealy, E., (2024). AI hype as a cyber security risk: The moral responsibility of implementing generative AI in business. AI and Ethics, 4(3), pp.791-804.

Illanes, P., Lund, S., Mourshed, M., Rutherford, S. and Tyreman, M., (2018), Retraining and reskilling workers in the age of automation , available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/retraining-andreskilling-workers-in-the-age-of-automation