Madagascar Protected Area Outlook 2025

A Conservation Assessment of Terrestrial Protected Areas in Madagascar

The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of each or any participating Madagascar Protected Area consortium partner, author, or editor.

The Madagascar Protected Area consortium partners and authors are pleased to acknowledge the support of FAPBM, MEDD and Conservation Allies who provided support to produce this publication.

Published by: Madagascar Protected Area consortium partners, Antananarivo, Madagascar.

Authors: Madagascar Protected Area Consortium Partners composed of: Ministère de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable (MEDD), Fondation pour les Aires Protégées et la Biodiversité de Madagascar (FAPBM), Madagascar National Parks (MNP), Antrema Miray (AMI), ASITY Madagascar, Association Analasoa, Association Fanamby, Association FARAFATSI, Association Fosa, Association Makirovana, Association Mazava-Nature, Association Mitsinjo, Association Natiora, Association TAMIA, Association Environnementale pour la Recherche l’Éducation la Conservation et le Développement Durable (E–RECODEV), Fikambanana Bongolava Maitso (FBM), Groupe d’Etude et de Recherche sur les Primates de Madagascar (GERP), IMPACT Madagascar, Madagascar Biodiversity Partnership (MBP), Madagascar Wildlife Conservation (MWC), Madagasikara Voakajy (MV), Ny Tanintsika, Planet Madagascar, SADABE, University of Antananarivo Plant Biology and Ecology (MBEV), Université de la SAVA (USAVA) and VIHY.

Editors: Rakotoarisoa, Solofo Eric; Andriajaona, Aubin ; Andriamihajarivo, Tefy ; Andriamparany, Solonantenaina; Andrianjafy, Sarindra Ellarissa; Andrianome Jean Bien Aimé; Andriandrainy, Dorian; Belalahy, Rodriguez Tertius; Edmond, Roger; Emeline; Lehavana, Adolphe; Malalaharivony, Hasina; Miandrimanana, Cyprien; Nasoavina, Christain; Rabarisoa, Rivo; Ranaivoarisoa,Faly, Rabevao, Edgar; Rahajanirina, Narcisse; Raharijaona, Alain Sandy Liva; Raharison Jean-Luc; Raherison, Marco; Rakotoarinivo, Toky Hery; Rakotoarisoa, Ony; Rakotondrabe, Andriamihaja rado; Ralisata, Mahefatiana; Ramahefamanana, Narindra; Ramaroson, Rova; Ramiandra, Velojaona Audlin; Ranaivoson, Rija; Ranaivoson, Rindra; Randimbiharinirina, Doménico; Randriamamonjy, Voahirana; Randriamialisoa; Randrianjatovo, Solofoson; Randrianjafizanaka, Ranirison, Patrick; Soary Tahafe; Rasoamanana, Elysée Noro; Rasoanaivo, Faly Harisoa; Rasolondravoavy, Charles; Raveloarimalala, Mialisoa Lucile; Razafimanahaka, Hanta Julie; Razakafamantanantsoa, Antso; Vavy Viviane; Tsiavahananahary, Tsaralaza Jorlin

Copyright: © 2025 Madagascar Protected Area Consortium Partners

Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission, provided the source is fully acknowledged.

Citation: Rakotoarisoa, S.E.; Andriajaona, A. ; Andriamihajarivo, T. ; Andriamparany, S.; Andrianjafy, S.E.; Andrianome J.B.A.; Andriandrainy, D.; Belalahy, R.T.; Edmond, R.; Emeline; Lehavana, A.; Malalaharivony, H.; Miandrimanana, C.; Nasoavina, C.; Rabarisoa, R.; Rabevao, E.; Rahajanirina, N.; Raharijaona, A.S.L.; Raharison J-L.; Raherison, M.; Rakotoarinivo, T.H.; Rakotoarisoa, O.; Rakotondrabe, A.R.; Ralisata, M.; Ramahefamanana, N.; Ramaroson, R.; Ramiandra, V.A.; Ranaivoarisoa,F.; Ranaivoson, R.; Ranaivoson, R.; Randimbiharinirina, D.; Randriamamonjy, V.; Randriamialisoa; Randrianjatovo, S.; Randrianjafizanaka, S.T.; Ranirison, P.; Rasoamanana, E.N.; Rasoanaivo, F.H.; Rasolondravoavy, C.; Raveloarimalala, M.L.; Razafimanahaka, H.J.; Razakafamantanantsoa, A.; Vavy V.; Tsiavahananahary, T.J.. Madagascar Protected Area Outlook 2025: A conservation assessment of terrestrial Protected Areas in Madagascar, September 2025. Antananarivo, Madagascar. 84 pp.

ISBN-13: 978-0-982761 -4

Layout by: Staci Weber

Printed by: Fondation pour les Aires Protégées et la Biodiversité de Madagascar (FAPBM)

Email: mail@fapbm.org or solofo@conservationallies.org

Website: www.fapbm.org

This publication has been made possible by support from:

Foreword

By Alain Sandy Liva RAHARIJAONA

Former Executive Director of FAPBM, Team Lead, Madagascar 30x30

It is with great commitment to Madagascar’s natural heritage that we present the second edition of the Madagascar Protected Areas Outlook. This conservation assessment represents a landmark effort: the very first analysis that systematically examines deforestation across the entire network of terrestrial Protected Areas in Madagascar. By bringing together data, insights, and comparative trends, it provides an unprecedented overview of the strengths and vulnerabilities of our Protected Area system.

Like any pioneering initiative, this Outlook is both a strength and a challenge. Its greatest strength lies in offering, for the first time, a replicable, transparent, and publicly accessible assessment of deforestation across all 109 terrestrial Protected Areas. This creates a common foundation upon which policymakers, conservation organizations, and communities can build shared strategies for biodiversity conservation. At the same time, the work is not without its weaknesses. Data limitations, methodological constraints, and the complexity of pressures facing Madagascar’s forests mean that this document is not perfect. Yet it is the best picture we currently have, and one that is both urgently needed and critically important.

Beyond serving as an assessment, this Outlook is also designed as a practical tool. It supports the Malagasy Government, Protected Area managers, donors, and other stakeholders in making informed decisions, setting priorities, and directing resources where most needed. In this way, the Outlook becomes not only a diagnostic exercise but also a roadmap for action.

We emphasize that this report should not be seen as a final product, but as the beginning of a continuous and collaborative process. The Outlook will be updated every year, enriched by new data, strengthened by the contributions of a growing network of scientists, conservation practitioners, and institutions working in Madagascar. With each edition, our collective understanding of the challenges and opportunities for Protected Areas will improve, as will the strategies needed to ensure their long-term survival.

We invite all actors to view this Outlook as both a warning and a call to action: a warning about the scale of threats to Madagascar’s forests, and a call to unite efforts in protecting the irreplaceable biodiversity that defines our island nation.

Executive Summary

A year ago, we published the first edition of the Madagascar Protected Area Outlook 2024 (Rakotoarisoa et al. 2024), providing a comprehensive assessment of forest cover loss across all terrestrial Protected Areas (PAs) in the country. This 2025 update integrates the latest deforestation data until December 31st, 2024, sourced from Global Forest Watch, offering new insights into trends, progress, and emerging threats to Madagascar’s PAs.

This analysis reaffirms that forest cover loss remains the most critical indicator of tracking PA effectiveness and vulnerability. With the world striving to meet global biodiversity and climate targets, the status of Madagascar’s terrestrial PAs is of global significance.

Despite being among the world’s poorest nations, Madagascar hosts an unmatched concentration of unique and endemic biodiversity, isolated for over 80 million years.

As a reflection of the critical importance of biodiversity conservation, Madagascar has 3,759 endemic Threatened species according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (2025), which is almost twice as many as any other country in the world. This demonstrates that Madagascar is the

#1 Biodiversity Hotspot on the planet and that conservation attention and support is not only vital here, but imperative to avert an extinction crisis.

In this updated analysis, we reassessed forest loss trends across all 109 terrestrial PAs, incorporating 2024 data. While total forest loss remains stubbornly high, several major positive developments emerged in 2024, which is a very encouraging shift.

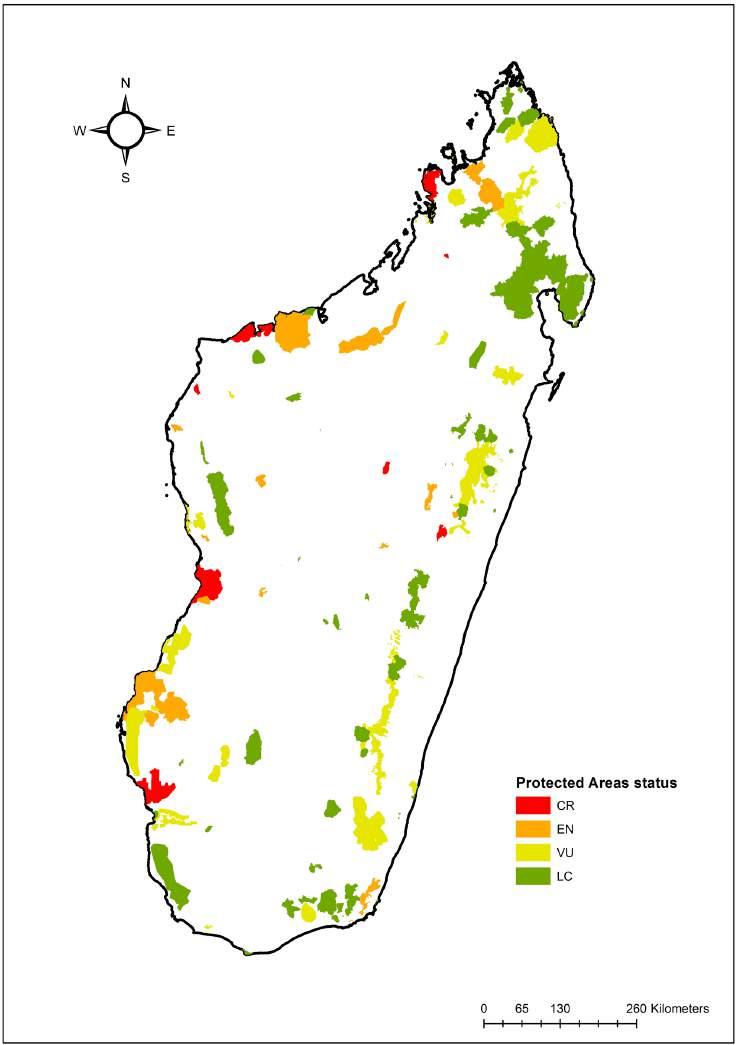

Through our threat classification system, PAs are ranked based on projected forest loss:

CR Critically Endangered

Near total forest loss expected in <10 years

EN Endangered

Near total forest loss expected in <25 years

VU Vulnerable

Near total forest loss expected in <40 years

LC Least Concern

Stable forest cover or low risk, but conservation dependent.

2025 Updates and Changes from Outlook

2024:

There has been a decrease of 8,185 hectares in overall deforestation across the 109 terrestrial PAs from 2023 to 2024, although over 31,598 hectares of forest were lost in 2024. More than 50% (57) PAs

saw reduced deforestation rates in 2024, 17 PAs saw unchanged rates, and 35 PAs showed worsening trends. Importantly, the most threatened PAs from the Outlook 2024 saw reduced deforestation rates, which is thanks to various actions, but particularly PA enforcement efforts in recent years.

These changes include:

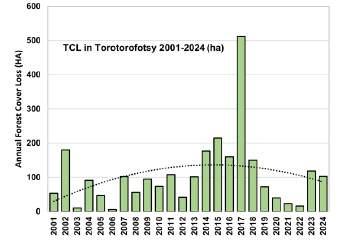

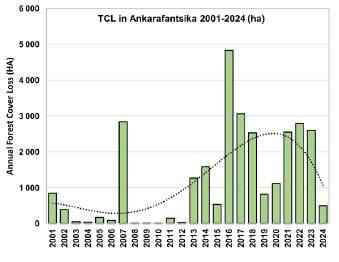

█ Critically Endangered PAs = 9: decreased from 13 in 2023 thanks to strategic PA enforcement efforts at these extremely threatened sites. Former CR PAs with reduced deforestation include Ankarafantsika, Torotorofotsy, Manjakatompo, and the Complexe Anjozorobe-Angavo.

█ Endangered PAs = 18: 3 sites decreased to Vulnerable, while 4 sites were added from CR. Former EN PAs with reduced deforestation include Manombo, COFAV, Corridor Ankeniheny-Zahamena, Makirovana-Tsihomanaomby, and Kirindy Mitea.

█ Vulnerable PAs = 22: rose from 19 as 3 sites added from EN.

█ The number of Least Concern PAs remained stable at 60

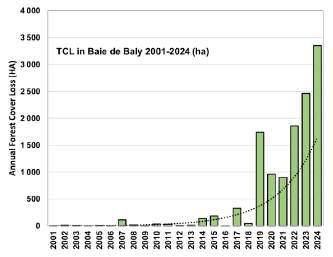

█ PAs of increased concern are Bora (increased rank to 2nd most threatened PA) and Baie de Baly (increased rank to 4th most threatened PA).

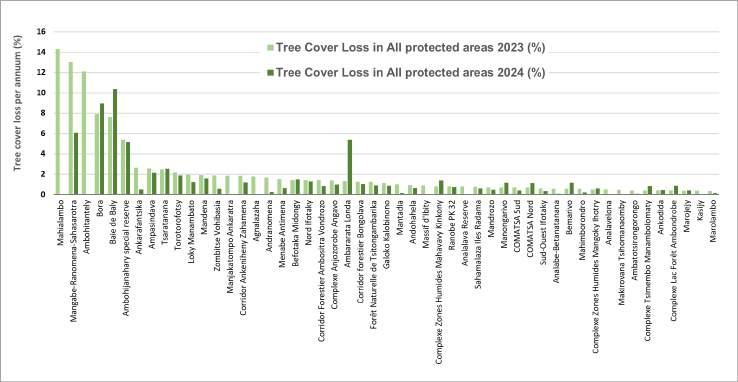

█ Encouragingly, the PA with the maximum average annual forest loss rate declined from 7.16% in 2023 to 4.51% in 2024 (Mangabe-Ranomena-Sahasarotra).

Madagascar’s terrestrial PAs cover 11.9% of the national territory, totaling 6,999,081 hectares. However, only 3.30 million hectares of forest cover remain inside PAs, representing 47.23% of the entire 109 PAs or just 5.6% of the country’s area.

Our assessment continues to show that 47% of PAs have lost more than half of their original tree cover, with 24 PAs losing over 75%. Eight PAs have lost more than 50% of their tree cover since their designation as a PA (Bora has lost 85.2%).

While the overall trend indicates major threats to forest integrity across much of the PA system, the Outlook appears more positive provided PA enforcement efforts are sustained and expanded. We hope this updated Outlook informs donors, policymakers, and conservationists of the urgent need for enhanced, targeted support.

Malagasy conservation organizations and MEDD remain the most competent, able, and committed to lead these efforts.

Résumé Opérationnel

Il y a un an, nous avons publié la première édition de Madagascar Protected Areas Outlook (Rakotoarisoa et al. 2024), offrant une évaluation complète de la perte de couvert forestier dans l’ensemble des Aires Protégées (AP) terrestres du pays. Cette mise à jour 2025 intègre les données de déforestation les plus récentes jusqu’au 31 décembre 2024, issues de Global Forest Watch , et fournit de nouvelles perspectives sur les tendances, les progrès et les menaces émergentes qui pèsent sur les APs de Madagascar.

Cette analyse confirme que la perte de couvert forestier demeure l’indicateur le plus critique pour suivre l’efficacité et la vulnérabilité des APs. Alors que le monde s’efforce d’atteindre les objectifs mondiaux en matière de biodiversité et de climat, l’état des APs terrestres de Madagascar revêt une importance planétaire.

Malgré sa position parmi les pays les plus pauvres du monde, Madagascar abrite

une concentration inégalée de biodiversité unique et endémique, isolée depuis plus de 80 millions d’années.

En témoigne l’importance cruciale de la conservation de la biodiversité: selon la Liste Rouge de l’UICN des espèces menacées (2025), Madagascar compte 3 768 espèces endémiques menacées, soit presque deux fois plus que tout autre pays au monde. Cela démontre que Madagascar est le Hotspot de biodiversité n°1 sur la planète, et que l’attention et le soutien à la conservation ne sont pas seulement vitaux ici, mais indispensables pour éviter une crise d’extinction.

Dans cette mise à jour, nous avons réévalué les tendances de perte forestière dans l’ensemble des 109 APs terrestres, en intégrant les données de 2024. Bien que la perte totale de forêts demeure élevée, plusieurs évolutions positives majeures sont apparues en 2024, un changement très encourageant.

Notre système de classification des menaces classe les APs selon la perte forestière projetée:

Perte totale attendue en <10 ans.

Perte totale attendue en <25 ans.

Perte totale attendue en <40 ans

ou faible

Principales évolutions 2025 par rapport à l’Outlook 2024:

█ Diminution de 8 185 hectares de déforestation totale dans les 109 APs terrestres entre 2023 et 2024, bien que plus de 31 598 hectares aient été perdus en 2024.

█ Plus de 50 % des APs (57) ont connu une baisse du rythme de déforestation en 2024, 17 sont restées stables et 35 ont vu leurs tendances s’aggraver.

█ Les APs les plus menacées dans l’édition 2024 ont montré une réduction de la déforestation, grâce notamment aux efforts récents de renforcement de l’application des lois.

Ces changements incluent:

█ AP en danger critique (CR) = 9: contre 13 en 2023, grâce aux efforts stratégiques de gestion et de contrôle. Parmi elles: Ankarafantsika, Torotorofotsy, Manjakatompo et le Complexe Anjozorobe-Angavo.

█ AP en danger (EN) = 18: 3 sites sont passés en Vulnérable, tandis que 4 autres ont été ajoutés depuis la catégorie CR. Exemples: Manombo, COFAV, Corridor Ankeniheny-Zahamena, Makirovana-Tsihomanaomby et Kirindy Mitea.

█ AP vulnérables (VU) = 22: contre 19 auparavant, avec 3 sites ajoutés depuis EN.

█ AP en préoccupation mineure (LC): reste stable à 60.

Les APs les plus préoccupantes sont désormais Bora (2ᵉ plus menacée) et Baie de Baly (4ᵉ plus menacée).

À noter: le taux moyen de perte forestière annuelle maximale d’une AP est passé de 7,16 % en 2023 à 4,51 % en 2024 (Mangabe-Ranomena-Sahasarotra).

Les APs terrestres de Madagascar couvrent 11,9 % du territoire national, soit 6 999 081 hectares. Cependant, seulement 3.30 millions d’hectares de couvert forestier subsistent dans les APs, représentant 47,23 % de l’ensemble des 109 APs, ou à peine 5,6 % de la superficie du pays.

Notre évaluation montre également que 47 % des APs ont perdu plus de la moitié de leur couvert forestier initial, dont 24 APs avec plus de 75 % de perte. Huit APs ont perdu plus de 50 % de leur couvert forestier depuis leur désignation (Bora a perdu 85,2 %).

Si la tendance générale reflète encore de fortes menaces pour l’intégrité forestière d’une grande partie du réseau des APs, les perspectives apparaissent plus positives à condition que les efforts de contrôle et de protection soient maintenus et renforcés.

Nous espérons que cette nouvelle édition de l’Outlook guidera les bailleurs, décideurs et acteurs de la conservation sur l’urgence d’un soutien accru et ciblé.

Les organisations malgaches de conservation et le Ministère de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable (MEDD) demeurent les plus compétentes, capables et engagées pour mener ces efforts.

Famintinana

Herintaona lasa izay ny namoahana voalohany ny boky Madagascar Protected Areas Outlook 2024 (Rakotoarisoa et al . 2024), izay nanome tatitra feno momba ny fahaverezan’ny rakotra ala tao anatin’ireo Faritra Arovana (AP) an-tanety 109 manerana an’i Madagasikara. Ity tatitra faharoa 2025 ity dia manampy ny vaovao farany momba ny fandripahana ala hatramin’ny 31 Desambra 2024, avy amin’ny Global Forest Watch, ka manolotra fijery vaovao momba ny fironana, ny fandrosoana ary ny loza vaovao mitatao amin’ireo AP eto Madagasikara.

Ny fanadihadiana dia manamafy fa ny fahaverezan’ny rakotra ala dia mbola mijanona ho famantarana lehibe indrindra amin’ny fandrefesana ny fahombiazan’ny AP sy ny faharefoany. Raha mbola miady mafy izao tontolo izao hahatratra ireo tanjona iraisam-pirenena momba ny toetrandro sy ny fiarovana ny zavaboary, dia manana ny lanjany maneran-tany ny toe-draharaha mikasika ny AP an-tanety eto Madagasikara.

Na dia isan’ny firenena mahantra indrindra aza i Madagasikara, dia manana harena voajanahary maro tsy manam-paharoa ary tsy fahita maneran-tany, izay efa nisaraka ary nitokana nandritra ny 80 tapitrisa taona mahery.

Araka ny tatitry ny IUCN Red List (2025), i Madagasikara dia manana karazan-javamananaina miisa 3 768 tsy fahita n’aiza n’aiza izay tandindonin-doza, izay saika avo roa heny noho ny an’ny firenena hafa rehetra. Izany no mahatonga an’i Madagasikara ho isan’ireo faritra “Hotspot Biodiversity” voalohany maneran-tany, ary tsy maintsy atao laharam-pahamehana ny fiarovana azy mba hisorohana krizin’ny fahalaniana taranaka ireo karazan-javamananaina misy ao aminy.

Amin’ity fanavaozana ity dia nodinihinay indray ny fironan’ny fahaverezan’ny ala ao anatin’ireo AP 109 an-tanety, miaraka amin’ny antontan’isa 2024. Na dia mbola avo be aza ny totalin’ny ala very, nisy fivoarana miabo hita tamin’ny taona 2024, izay manome fanantenana.

Rafitra fanasokajiana ny loza mitatao amin’ny AP:

CR Tena Tandindomin-doza Indrindra

Ho ringana ao anatin’ny <10 taona

EN Tandindomin-doza

Ho ringana ao anatin’ny <25 taona

VU Marefo

Ho ringana ao anatin’ny <40 taona.

LC Kely Fanahiana

Rakotra ala mbola milamina na ambany tsindry

Fanavaozana 2025 raha oharina amin’ny Outlook 2024:

█ Nihena 8 185 ha ny ala very tao anatin’ny AP an-tanety 109 tamin’ny 2024 raha oharina tamin’ny 2023, na dia mbola 31 598 ha mahery aza no very tamin’ny taona 2024.

█ 57 AP (mihoatra ny 50%) no nahitana fidinan’ny fandripahana ala, 17 tsy niova, ary 35 niharatsy.

█ Ireo AP tandindonin-doza indrindra tamin’ny 2024 dia nihena ny tahan’ny fandripahana, noho ny fampiharana lalàna sy fiarovana hentitra tao anatin’ny taona vitsivitsy.

Fiovana lehibe:

█ CR = 9 (raha 13 tamin’ny taona 2023). Tafiditra amin’izany ny Ankarafantsika, Torotorofotsy, Manjakatompo, ary Complexe Anjozorobe-Angavo.

█ EN = 18 (nisy ireo AP 3 lasa VU, ary 4 avy amin’ny CR). Tafiditra ao Manombo, COFAV, Corridor Ankeniheny-Zahamena, Makirovana-Tsihomanaomby, ary Kirindy Mitea.

█ VU = 22 (raha 19 tamin’ny taona 2023).

█ LC = 60 (tsy niova).

Ireo AP atahorana indrindra amin’izao: Bora (lasa laharana faha-2 amin’ny tena tandindonin-doza) sy Baie de Baly (lasa laharana faha-4).

Ny tahan’ny fandripahana faratampony isan-taona indrindra tamin’ny AP iray dia nihena satria raha 7,16% tamin’ny 2023 dia nihena lasa 4,51% tamin’ny 2024 (Mangabe-Ranomena-Sahasarotra).

Ny AP an-tanety eto Madagasikara dia mandrakotra 11,9%-n’ny velaran-tanin’i Madagasikara, mitentina 6 999 081 ha. Kanefa 3,30 tapitrisa ha monja ny rakotra ala sisa tavela ao anatin’ireo AP, izany hoe 47,23%-n’ny AP rehetra, na 5,6%-n’ny velaran-tanin’i Madagasikara ihany.

Tsikaritra ihany koa fa 47% amin’ny AP no very mihoatra ny antsasaky ny rakotra ala nisy hatrizay, ary 24 AP no very mihoatra ny 75%. Faritra Arovana 8 no very mihoatra ny antsasaky ny rakotra ala hatramin’ny nananganana azy ho faritra arovana (ny Bora no be indrindra, very 85,2%).

Raha toa ka manambara ny fironana ankapobeany fa mbola misy loza goavana mitatao ho an’ny ampahany betsaka amin’ireo

rakotra ala sisa tavela ao anatin’ny tambajotran’ny AP, dia hita fa misy fiovana miabo ary misy ny fanantenana raha toa ka tohizana sy ampitomboina ny asa fampiharana lalàna sy fiarovana.

Manantena izahay fa ity tatitra vaovao ity dia hanampy ireo mpamatsy vola, mpanao politika, ary mpiaro ny tontolo iainana hahatakatra bebe kokoa ny maha-maika ny fanohanana fanampiny sy voatokana ho an’ireo fariitra arovana. Ny fikambanana malagasy miaro tontolo iainana sy ny Ministeran’ny Tontolo iainana sy ny Fampandrosoana Lovainjafy (MEDD) no mbola mitana ny andraikitra lehibe sy manana fahaiza-manao hitarika izany ezaka izany.

Madagascar Protected Area Consortium Partners

ASITY Madagascar https://asity-madagascar.org/

Association Analasoa

Association Antrema Miray (AMI)

Association Environnementale pour la Recherche, l'Éducation, la Conservation et le Développement Durable (E-RECODEV)

Association Fanamby

Association FOSA

Association Famelona

Association FARAFATSI

Association Makirovana

Association Mazava Nature

Association Mitsinjo

Association Natiora

Association TAMIA

https://www.antrema.mg/

https://association-fanamby.org/

https://www.fosa.mg/fr/

https://famelona.mg/

https://associationmitsinjo.wordpress.com/

Fikambanana Bongolava Maitso (FBM)

Fondation pour les Aires Protégées et la Biodiversité de Madagascar (FAPBM)

Groupe d’Etude et de Recherche sur les Primates de Madagascar (GERP)

IMPACT Madagascar

Madagascar Biodiversity Project (MBP)

Madagascar National Parks (MNP)

Madagascar Wildlife Conservation (MWC)

Madagasikara Voakajy (MV)

Ministère de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable (MEDD)

Ny Tanintsika

Planet Madagascar

SADABE

Université de la SAVA (USAVA)

University of Antananarivo, Plant Biology & Ecology (MBEV)

VIHY

https://www.bongolavamaitso.mg/

https://www.fapbm.org

http://www.gerp.mg/

https://impactmadagascar.org/

https://madagascarpartnership.org/

https://www.parcs-madagascar.com/

http://www.madagascar-wildlifeconservation.org

https://www.madagasikara-voakajy.org/

https://www.environnement.mg/

https://www.nytanintsika.org/en/

http://www.planetmadagascar.org/

https://sadabe.org/

https://www.facebook.com/p/Universitéde-la-SAVA-officiel-100063958548039/

https://mbev.univ-antananarivo.mg

https://vihy.mg/

Introduction

Much like the isolated, ancient, and biologically rich islands of Hawaii and New Zealand, Madagascar was only colonized by humans in the past two millennia. And in less than a thousand years, the island has lost the majority of its original forest cover along with large portions of its extraordinary and evolutionarily unique wildlife.

Yet unlike those other islands, Madagascar continues to face these mounting conservation challenges with some of the most limited financial resources in the world. Despite this, it remains a top global conservation priority, arguably more important for biodiversity than any other island on Earth, and comparable in ecological significance to entire continents.

Given this urgency, the Outlook partners initiated the first Madagascar Protected Area Outlook in 2024 (Rakotoarisoa et al 2024), providing a nationwide, quantitative assessment of forest loss across terrestrial PAs up to December 2023. The results showed that 9 PAs were classified as Critically Endangered, 18 PAs were classified as Endangered, 22 PAs were classified as Vulnerable, and 60 PAs were classified as Least Concern.

This 2025 edition builds on that foundation by incorporating 2024 tree cover loss data, offering an expanded view of current threats and trends in the shifting conservation landscape.

Using high-resolution satellite data accessible via Global Forest Watch ( globalforestwatch.org), we reassess the condition of Madagascar’s forests. In doing so, we aim to provide an updated, data-driven perspective

on the short- and long-term survival prospects of the country’s 109 terrestrial PAs.

To ground this analysis in real-world experience, we organized the “Protected Areas in Peril Forum 2024” , held in Andasibe from July 1–5, 2024. This forum brought together 34 expert PA managers, NGO leaders, researchers, and donors who contributed invaluable local knowledge and feedback that directly informed the Outlook.

This updated Outlook provides a refined tool for prioritizing conservation action, funding, and support at a time when the global community is seeking clear, measurable results in halting biodiversity loss and meeting targets under the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework.

As with the previous edition, this assessment focuses solely on terrestrial ecosystems, excluding Madagascar’s Marine PAs due to limitations in remote sensing for evaluating marine threats.

It is important to note that >99.9% of 3,768 endemic Threatened species depend on native terrestrial habitat, while there is just one endemic Threatened marine species. Therefore, safeguarding the network of 109 terrestrial PAs is critical for the survival of the greatest concentration of species restricted to one country and threatened with extinction.

We hope that this updated Outlook will not only continue to guide decision-makers and donors but also reaffirm the urgency and opportunity of acting now to safeguard Madagascar’s irreplaceable natural heritage.

History of Deforestation in Madagascar

Summary of deforestation in Madagascar:

Approximately 98.02% (57.5 million hectares) of Madagascar was forested.

Pre-human colonization

Estimated 27% of Madagascar is forested (Harper et al., 2007).

Human colonization

Madagascar’s interior was colonized within the last 1,300 years.

A detailed understanding of Madagascar’s historical forest cover, its subsequent loss, and the drivers of deforestation is provided in the Madagascar

Protected Area Outlook 2024.

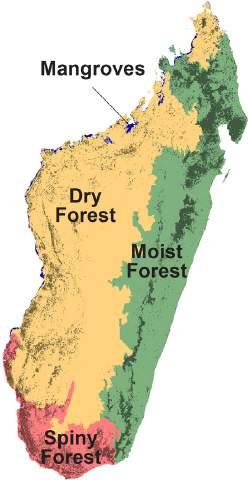

Figure 1: Approximate distribution of ecoregions and forest types in Madagascar, divided along climatic ecoregions with forest types: the moist forest in the East (dark green), the dry forest in the West (bright green), the spiny forest in the South (pale green), and the mangroves on the West coast (blue). Map adapted from Vieilledent et al. (2018).

1950s

Estimated 21% of Madagascar is forest (Guichon, 1960).

1960

Only 11.8% of Madagascar’s primary forest cover remains while 40.4 million hectares of forest have been lost, which is equivalent to over 70.2% of the original primary forest lost.

2000

5.7% of Madagascar retains primary humid forest cover.

2024 2024

11.9 million hectares of tree cover, representing 20.7% of Madagascar.

History of Protected Areas in Madagascar

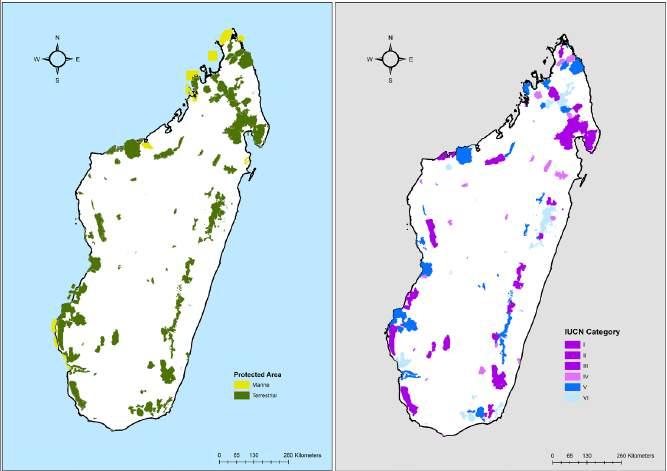

The first PAs in Madagascar were established in 1927 by the French colonial authorities, with the designation of 10 Réserves Naturelles Intégrales (RNI) covering 433,372 hectares (Andriamampianina, 1987). These sites were strictly protected, with little to no human activity allowed. Over the following seven decades, an additional 35 PAs were created, expanding protection at an average rate of five sites per decade.

A pivotal moment came at the IUCN World Parks Congress in Durban in 2003, when the President of Madagascar announced a commitment to triple the national PA coverage, expanding from 1.7 million hectares to 6 million hectares. This led to the creation of the “Système des Aires Protégées de Madagascar (SAPM)”, designed to include new categories of PAs that better integrated biodiversity conservation with sustainable use and community management. Between 2003 and 2015, the network grew dramatically, with a 160% increase as 67 new terrestrial PAs were established.

Today, Madagascar’s network includes 109 terrestrial PAs and 14 marine PAs, together covering approximately 11.9% of the national land surface. These sites are managed under a diverse governance system that includes Madagascar National Parks (MNP), the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development (MEDD), and a wide range of national and international NGOs and community-based organizations.

Recent Developments and Challenges (2020–2025)

Since the Madagascar Protected Areas Outlook 2024 (Rakotoarisoa et al. 2024), several new trends have shaped the evolution of Madagascar’s PA system:

█ Expansion of marine conservation: While terrestrial PAs remain the backbone of the system, increasing international and national attention has been directed toward Madagascar’s marine ecosystems. In recent years, 178 Locally Managed Marine Areas (LMMAs) have gained official recognition, complementing the 14 nationally designated Marine PAs.

█ Community engagement: The System of Protected Areas of Madagascar (SAPM) has continued to evolve, with greater emphasis on co-management and community governance. Traditional practices, such as dina and titiky social pacts, are increasingly recognized as valuable tools for local stewardship and sustainable management.

█ International commitments: Madagascar has aligned its conservation strategy with global targets such as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (2022), which calls for protecting at least 30% of land and sea by 2030 (30x30). Dialogues are ongoing about how to expand coverage and strengthen existing sites to meet this target.

█ Pressures and risks: forest clearance for agricultural expansion remains the primary driver posing serious challenges. Forest loss within PAs remains uneven, with some sites experiencing stabilization while others face rising threats.

█ Monitoring and evaluation: The Outlook 2025 introduces a comparative analysis of changes since the Outlook 2024, making it possible to track which PAs have improved, deteriorated, or remained stable and to assess the effectiveness of the country’s PA network.

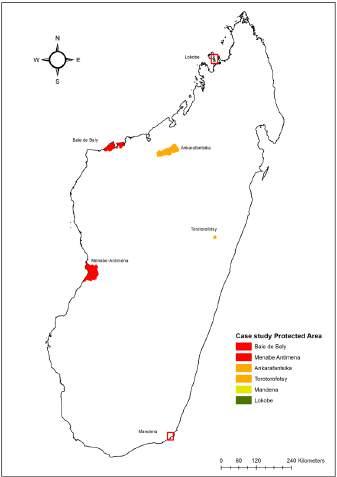

Figure 2: Map of Protected Areas across Madagascar in 2025 (left) and distribution of 109 terrestrial PAs across Madagascar (right) with color code to show the IUCN Protected Area category assigned. Several sites (5) lacking a specific category were assigned to the lowest protection category VI.

Protected Areas Outlook Objective

This updated Madagascar Protected Areas Outlook aims to provide an evidence-based assessment of the current state of Madagascar’s terrestrial PAs, using the most recent deforestation data (including 2024 data) to track changes since the first edition. By comparing forest cover trends across all terrestrial PAs, the report evaluates both progress and emerging challenges in forest and biodiversity conservation. The updated analysis seeks to identify areas of improvement, highlight sites at increasing risk, and assess the effectiveness of past management responses. Building on these findings, it offers targeted, forward-looking recommendations to strengthen protection, enhance resilience, and guide adaptive management strategies for the coming years.

Protected Area Outlook Methodology 2025

Outlook Data

To achieve the objectives of this second edition of the Outlook, we compiled and analyzed public datasets from the following sources, building upon much of the data from the first edition:

1) Protected Area polygons and data were obtained from the Madagascar Protected Areas website (www.protectedareas.mg) and the World Database on Protected Areas (www. protectedplanet.net). ArcGIS was used to calculate the surface area of each terrestrial PA. The surface unit used for this study is the hectare (ha).

2) Global Forest Watch forest loss data (www.globalforestwatch.org) was used to analyze deforestation for each site. The data used for the analysis of tree cover loss are based on satellite data available between 2001 and 2024. To avoid overestimation or underestimation of tree cover, we followed the recommendation of Rafanoharana et al. (2023). For this, the tree cover densities used for humid forests were set between 50% and 75%, 10% for dry spiny forests (in the south and southwest), and 30% for the remainder (dry forests and woodlands in the highlands). The data source credit is as follows: “Hansen/UMD/Google/USGS/NASA, accessed through Global Forest Watch” and citation is Hansen et al. (2013).

Global Forest Watch offers comprehensive, global, and annually updated data on forest changes. It is regarded as one of the best sources for mapping deforestation, with its high spatial resolution and wide application across sectors such as government, academia, and civil society. As methodologies and satellite technology improve, there will be occasional inconsistencies, but the overall trend is toward better accuracy and more detailed detection of forest loss. Awareness of these changes is crucial for correctly interpreting and using the data.

Hansen et al. (2013) summarize the evolution and improvements in tree cover loss data. The key improvements include enhanced algorithms, better satellite data (e.g., Landsat 8), and increased satellite coverage, allowing for more accurate detection of forest loss, especially smaller disturbances. However, these advancements have introduced some inconsistencies in the data over time. The article provides guidelines for analyzing trends and suggests using 3-year moving averages to account

for these inconsistencies. Future updates, such as the new algorithm version 2.0, aim to improve the consistency of historical data while addressing challenges like distinguishing between different types of forest loss. Despite occasional inconsistencies, Global Forest Watch data remains the most valuable and easily accessible resource for conservationists to understand global deforestation trends.

As with the Outlook 2024, only 109 terrestrial PAs were assessed, since forest cover change is the most reliable and comparable indicator across sites. Marine PAs and those with more than 95% of their surface area in the sea or inland water bodies were excluded from the analysis.

Historic Forest Cover Assessment

As in the Outlook 2024, a detailed review of the literature and available evidence on Madagascar’s pre-human vegetation was undertaken to distinguish between natural grasslands and anthropogenic transformation. This assessment is detailed in the 2024 edition Annex ( “Ancient or Anthropogenic: the myth of natural grasslands in Madagascar”).

Google Earth Pro was used to map areas where the existence of forests was unlikely (sea, lakes, rivers, rocky areas), ensuring that forest loss estimates were restricted to originally forested areas.

The extent of forest cover at the date of creation of each PA was also established. For areas created after 2000, Global Forest Watch data provided accurate historical figures (covering 61% of PAs). For older PAs, extrapolated estimates were used.

Protected Area Outlook Assessment

The methodology for assessing each PA’s status remains unchanged from the first

CR Critically Endangered

Forest cover loss >2% per annum. EN

Endangered

edition. Forest loss datasets were analyzed and categorized into four Threat categories:

Forest cover loss between >1% and 2% per annum VU

Vulnerable

Forest cover loss between 0.5% and 1% per annum.

LC Least Concern

annum

These thresholds are based on 20-year averages combined with the most recent 3-year averages to account for accelerating or decelerating trends. Additional site information (e.g., responsible management organizations) is compiled but does not influence the categorization.

Outlook Analysis:

For each PA, the following analyses were performed:

1. Total Forest Cover (TFC) loss compared current forest cover with the original forest cover (pre-human).

2. Conservation Outlook (CO) was assessed by ranking Forest Cover Loss (FCL) averages across 5-year intervals (2005–2009, 2010–2014, 2015–2019, 2020–2024), plus the most recent averages (2022–2024). This provided weighted trends to establish priorities for conservation action.

Outlook 2025 Additions:

In addition to updating datasets through 2024, this second edition includes a comparative analysis of results between the Outlook 2024 and this Outlook 2025. This allows us to:

█ Identify PAs that have changed their Threat category.

█ Track the evolution of deforestation trends between the two assessments.

█ Provide insights into the effectiveness of conservation interventions recently undertaken.

This comparative component strengthens the Outlook’s role as a longitudinal monitoring tool for Madagascar’s PAs, enabling stakeholders to better understand year-toyear changes and prioritize adaptive management strategies.

Review Process

The review process followed a similar participatory approach as in the Outlook 2024 (Rakotoarisoa et al . 2024). Following the data analysis, results were shared at the Madagascar Protected Area Consortium Partners meeting held at the FAPBM office on 10th September 2025 with the Ministère de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable (MEDD), and a further 36 participants representing more than 20 Malagasy environmental organizations (IUCN Members, conservation NGOs, and PA managers). Preliminary findings were discussed with conservation partners to validate interpretations and integrate feedback. This collaborative process ensures that the Outlook 2025 remains as accurate, relevant, and actionable as possible.

█ By 2024, 79.2% of total forest cover (45.5 million ha) had been lost in Madagascar.

Protected Area Outlook Results 2025

Outlook Summary Data

Deforestation Across Madagascar:

█ 58.7 million ha of terrestrial land area in Madagascar.

█ Pre-human: 57.5 million ha (98.02%) of Madagascar was dominated by forest.

█ By 2000, 70.2% of total forest cover (40.4 million ha) had been lost in Madagascar.

█ By 2024, 79.2% of total forest cover (45.5 million ha) had been lost in Madagascar.

█ Between 2001–2024, 5.15 million ha of forest cover was lost.

█ Between 2015–2024, 2.85 million ha of forest cover was lost.

█ Between 2001–2024, 1.5 million ha of humid primary forest was lost.

█ Today, 11.9 million ha of forest cover survives in Madagascar. Of that, only 5.7 million ha of humid primary forest cover survives.

█ In 2024, 231,218 ha of Forest Cover Loss was reported across Madagascar.

Deforestation in Protected Areas:

█ 11.9% of Madagascar’s land is within the 109 PAs (6,999,081 ha).

█ 95.8% of the 109 PAs were originally forested (pre-human).

█ 41.3% of forest was lost in PAs by 2010 (2.77 million ha of forest lost).

█ 49.15% of forest cover was lost in PAs by 2024 (3.3 million ha of forest lost).

█ 17.2% (710,885 ha) of forest cover was lost in PAs between 2001–2024.

█ 10.2% of forest lost in PAs in the past decade (389,088 ha).

█ 1.1% average annual forest loss inside all PAs over the past 10 years.

█ In 2024, 33,622 ha of forest cover loss was reported inside 109 terrestrial PAs.

█ 4 PAs have lost more than 50% of their forests since 2001 (MangabeRanomena-Sahasarotra, Ranobe PK32, Ampasindava, Mahialambo).

█ 31 PAs have lost more than 20% of their forests since 2001.

█ 15 PAs have seen worse deforestation since 2015 (>20% of forest loss).

█ A total of 3,422,155 hectares of forest cover remain across the 109 terrestrial protected areas, representing 50.8% of their combined surface area.

Total Forest Cover (TFC) Changes Across Madagascar

To assess any forest losses within PAs, Rakotoarisoa et al . (2024) provided analysis on historic and modern-day forest losses in Madagascar.

In summary, with a land surface area of 58.7 million hectares (slightly larger than the area of France), Madagascar was estimated to originally be covered by 57.5 million hectares of forest around 700 A.D. By the time the first PAs were established in Madagascar in 1927, the majority of the cooler and moist highlands had been colonized and deforested, while a greater extent of forests survived in the eastern rainforests and the lowlands.

By 2000, the first detailed satellite forest cover assessment showed that only 29.7% (17.1 millions ha) of the original tree cover survived in Madagascar. From 2001 to 2024, an additional five million ha were lost. Alarmingly, nearly 3 million ha of total tree cover was lost in the last decade. The deforestation rate is equivalent to 1.85% per year (285,222 ha). During the same period, approximately one-third (1.1 million ha) of humid primary forest was lost.

Today, almost two-thirds of intact primary forests are restricted to 109 PAs, while onethird (2.2 million ha) are unprotected but heavily fragmented. Future research will focus on the location of these unprotected forests, but a tentative review shows that the majority are in the buffer zones of PAs.

Without decisive actions to mitigate deforestation, we project that >95% of total forest cover will be lost or heavily degraded and fragmented within the next 3–4 decades.

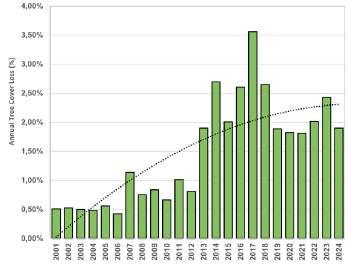

Figure 4: Percentage of annual total forest cover loss across Madagascar between 2001–2024 representing the combined loss of 5.15 million hectares of forest. A 2pt polynomial trendline shows a significant increase in deforestation, especially in the past decade (data: Global Forest Watch, 2025).

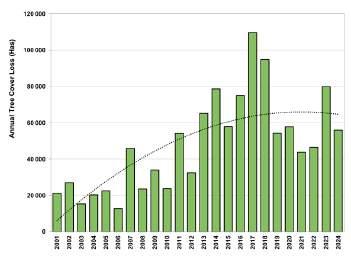

Figure 5: Annual Humid Forest Cover Loss in hectares across Madagascar between 2001–2024 (2pt polynomial trendline), with humid forest making up 23% of total tree cover loss in the same time period (data: Global Forest Watch, 2025).

Recent Forest Cover Change Across Madagascar’s Protected Areas

A total of 11.9% of Madagascar’s land area (6,999,081 ha) is protected by 109 PAs.

These PAs were originally estimated to be 95.8% forested (pre-human colonization), but by 2010 they had already lost 41.3% of their forest cover (2.77 million ha) and by 2024, 49.15% of their forests had been lost (3.30 million ha of forest lost).

Unfortunately, 10.21% of PA forest cover has been lost over just the last decade (389,088 ha lost from 2015–2024) at an average rate of 1.07% forest loss per year. Alarmingly, 15 PAs have seen accelerating deforestation since 2015 with more than 20% of forest cover lost in less than a decade. Four PAs have lost more than 50% of their forests since 2001 (Ranobe PK32, Mangabe-RanomenaSahasarotra, Ampasindava, Mahialambo).

Projections indicate >50%

of all

tree cover in PAs will be destroyed by 2026.

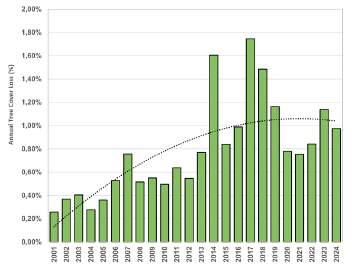

7: Annual proportion of Forest Cover Loss from 2015 to 2024 within the 45 terrestrial PAs created in 2015 (in dark green) compared to annual average tree cover loss across Madagascar (in pale green). This demonstrates an approximately 50% lower deforestation rate in newly created PAs (data: Global Forest Watch 2025).

A comparison between forest loss in newly created (2015) PAs compared to the deforestation rate across all of Madagascar aimed to assess if the creation of PAs can stop or reduce the pressures on forests. Figure 7 shows that consistently, the deforestation rate is 50% lower in new PAs than for Madagascar as a whole. However, after ten years since the creation of the 45 new PAs, the deforestation rate remains at an average 1.1 % tree cover lost a year in these areas.

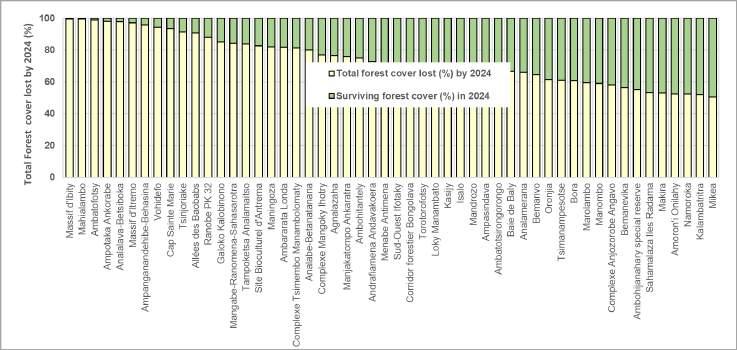

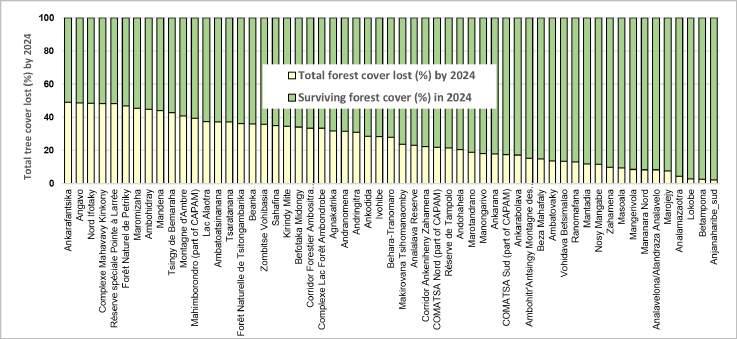

Present-day Forest Cover in Terrestrial Protected Areas

We assessed the present-day extent of forest coverage across all 109 PAs, excluding non-forest areas, such as open water and rocky outcrops. This is for natural forest cover as of 1 st January 2025, but deforestation may have taken place many years before the establishment of the PA. However, it is important to establish the present-day extent of natural forest cover within each PA to assess both its importance for conservation and just how perilous future deforestation could impact this site. This can also be valuable for potential restoration efforts as PAs can still be recovered, although preventing further primary forest loss is absolutely critical.

The extent of natural forest cover loss in PAs is alarming as almost 50% of all natural forest cover inside PAs has been lost to-date. In summary:

█ Almost half of the PAs (51) have lost more than 50% of tree cover (collectively 2.45 million hectares of tree cover were lost inside those PAs).

█ About one quarter of the PAs (28) have less than 25% of surviving forest cover (collectively they have lost over 240,254 hectares of forest cover).

█ A total of 3.3 million hectares of tree cover, representing 49.2% of all tree cover in terrestrial PAs, has been lost.

Deforestation inside PAs has collectively emitted an estimated 1.734 Gt CO2 into the atmosphere, equivalent to approximately 50% of the annual CO2 emissions of the European Union. While CO2 emissions are an extremely concerning impact of forest loss, this also represents a potential opportunity for support to reforest and restore areas and offset emissions from other countries. But caution is needed, as ongoing deforestation remains extremely high and must be reduced and stopped before any restoration benefits truly have a globally significant impact.

Six PAs had already lost over 95% of their original forest cover by the time they were established in 2015, so these sites are considered to be questionable from the perspective of viable biodiversity conservation and ecological functionality.

Table 1: Six PAs established in 2015 with >95% tree cover lost at the time of declaration and to date.

Conservation Outlook for Each Protected Area

Ensuring a bright future for Madagascar’s PAs is vital for maintaining ecological balance and ensuring the survival of the island’s incredible and unique terrestrial biodiversity.

CR Critically Endangered

Through the analysis of each PA, we explore the probable trends in deforestation and habitat degradation in order to assess future conservation priorities using the Conservation Outlook criteria (detailed in methodology). The results also enabled us to allocate a threat category:

Alarming forest losses (>2% per annum) indicating that intact primary forests will likely vanish within 10 years.

EN Endangered

Significant forest losses (>1 to 2% per annum) and/or deterioration indicating a high probability of losing intact primary forest within 25 years.

VU Vulnerable

Increasing annual forest losses (>0.5 to 1% per annum) and projected to lose intact primary forest within 50 years.

LC Least Concern

Limited to no forest losses (0 to 0.5% per annum) and considered stable forest cover.

While some areas show signs of successful management and conservation, others reveal the urgent need for targeted interventions. By highlighting the current status of these sites and their challenges, we aim to foster a greater understanding of the

ongoing deforestation and the critical role of effective conservation strategies. A summary of the most Threatened PAs (Critically Endangered, Endangered and Vulnerable) are presented in Table 2.

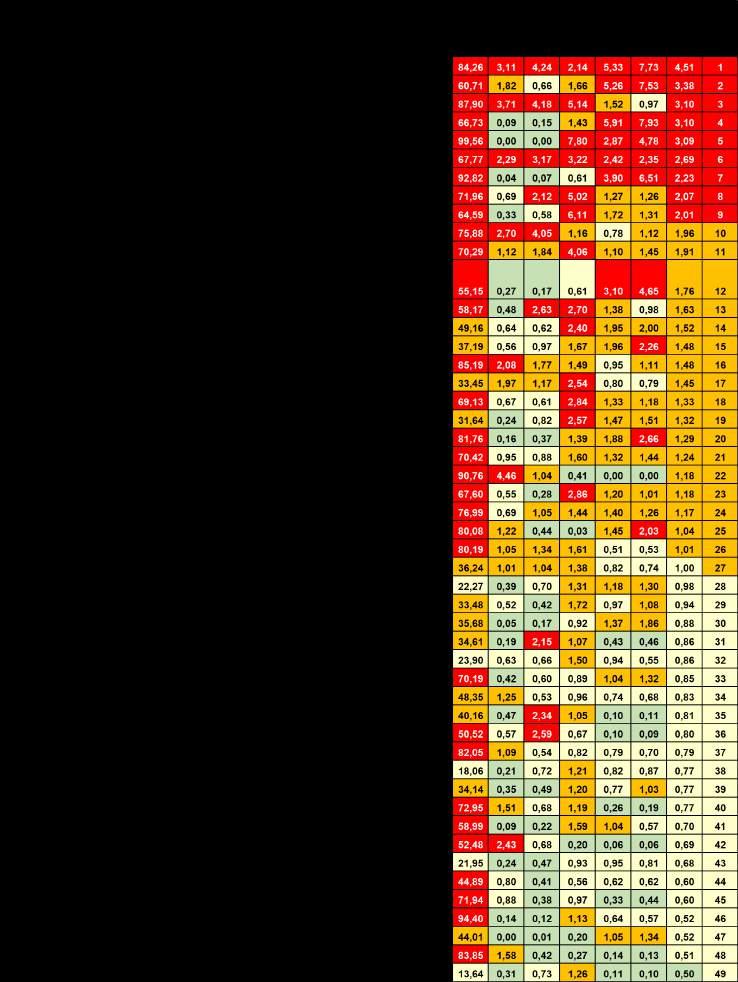

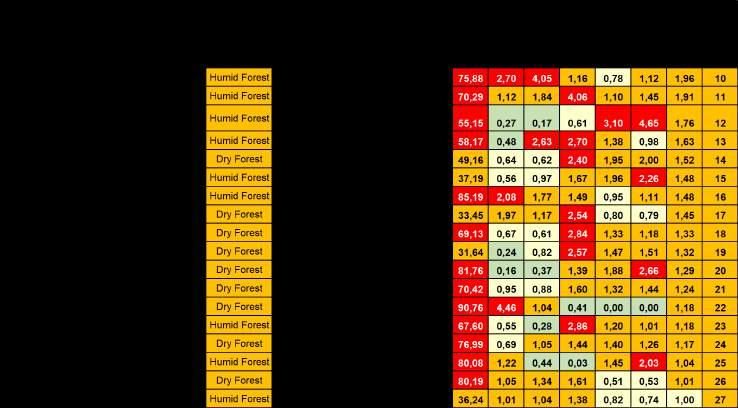

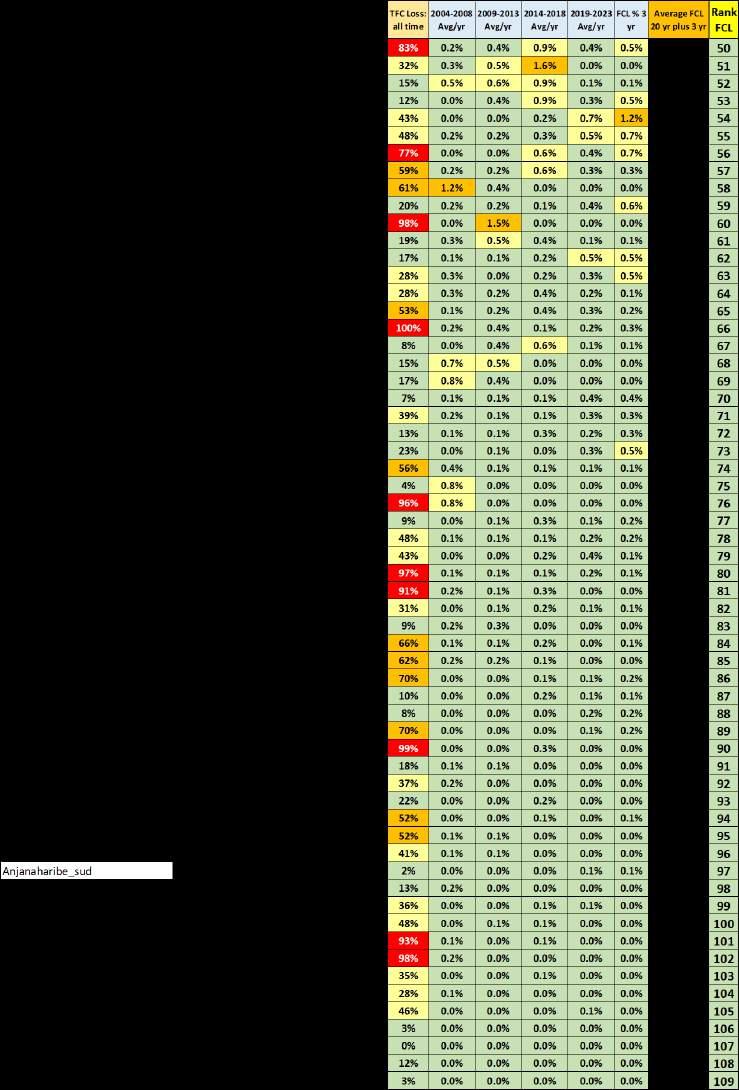

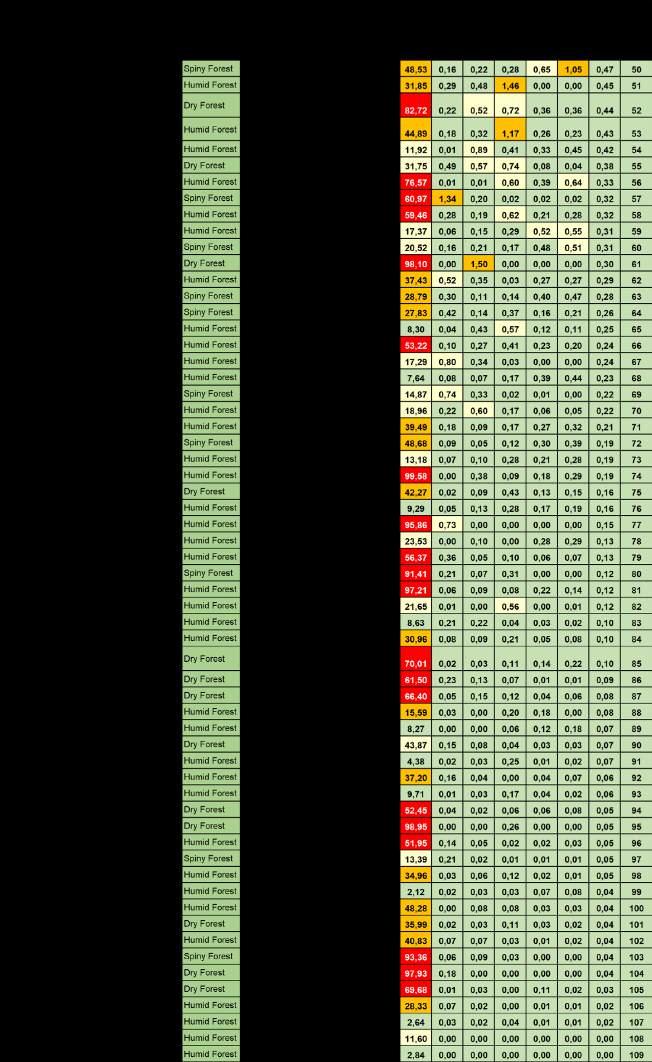

Table 2: Summary of key data related to 49 Critically Endangered, Endangered and Vulnerable PAs including ranking according to average Forest Cover Loss in five year periods from 2005–2024 and average annual deforestation rates from the past three years (2022–2024).

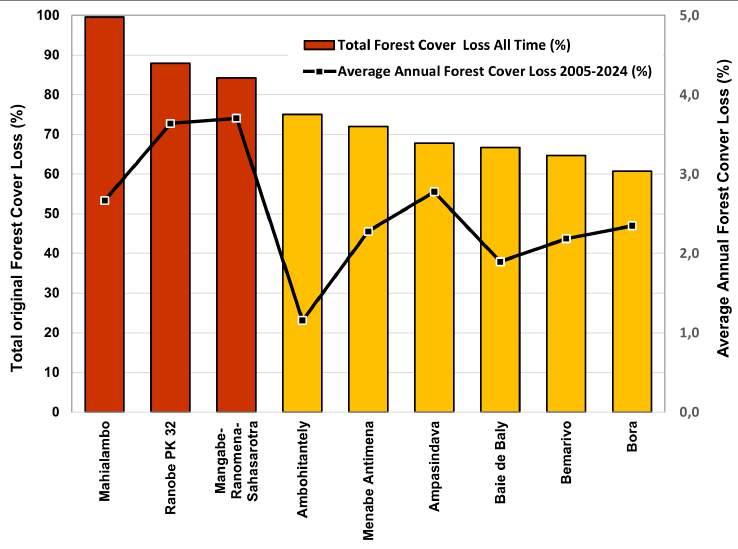

Critically Endangered Protected Areas in Madagascar

Nine sites or 8% of terrestrial PAs (581,152 ha) were classified as Critically Endangered (CR). These sites have experienced an annual average forest loss exceeding 2% per annum (the average across 9 sites was 2.9%) while, on average, less

than 24.6% of original forest cover survives (>75% of original forest cover has already been destroyed). Since being designated as PAs (including 3 PAs declared in 2015), average forest losses have been lower at 56%.

These nine PAs are composed of a combination of IUCN categories. However, one globally important National Park, Baie de Baly, is

considered CR and of particular concern as deforestation rates have accelerated in recent years, especially in 2024.

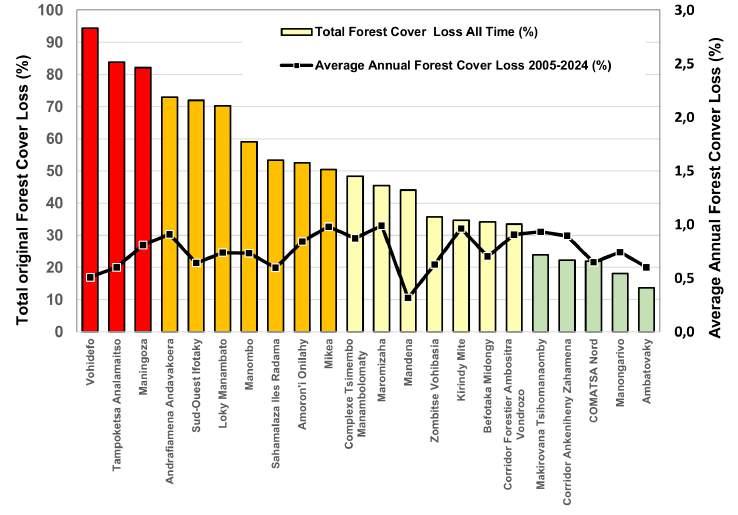

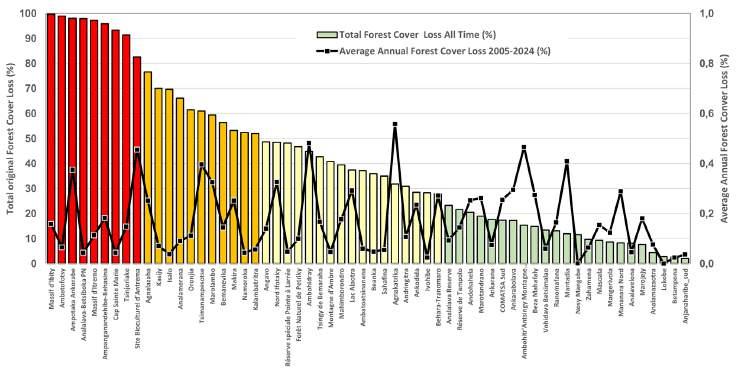

Figure 11: Nine Critically Endangered PAs ordered by the >2% average annual Tree Cover Loss percentage between 2005–2024 (red dotted line) and bar chart showing the Total Tree Cover loss at each PA with corresponding fills: red (CR), orange (EN).

More than 33% of CR sites fall under category V of the IUCN classification (harmonious landscapes), where some human activities such as agriculture and traditional practices are permitted under controlled conditions and specific zones. This may explain their CR status, as many are newly designated PAs (since 2015), where human activities were previously uncontrolled. However, almost all these sites continue to decline, even after gaining protection.

There are three PAs - Mangabe-RanomenaSahasarotra, Bora and Ranobe PK32 established between 2007–2015 - that stand

out as extremely concerning and ranked as the top three most threatened PAs in Madagascar despite conservation efforts taken; and probably some of the most threatened PAs on earth. It is possible that these three PAs will lose all ecologically functional, intact forest within the next five years. Ranobe PK32 is particularly complicated as it lacks a manager after WWF, who created the site, withdrew as the manager the year after the high-profile declaration. These three CR PAs need particular attention to conserve their ecological functions and important biodiversity.

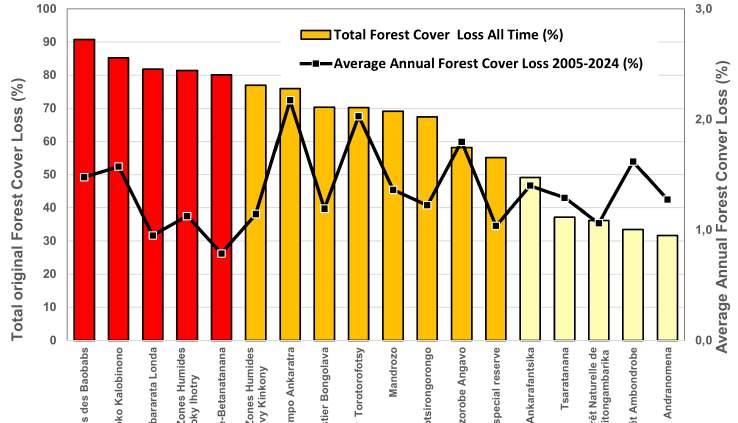

Endangered Protected Areas in Madagascar

A total of 18 terrestrial PAs were classified as Endangered (EN) because of annual average forest loss between >1 and 2% per annum (the average across 18 sites was 1.3%) while, on average, less than 36% of original forest cover survives (>50% of original forest cover has already been destroyed). Over 55% of

the 18 PAs were declared in 2015, but since declaration have seen an average 0.4% increase in annual Forest Cover Loss over the prior decade. Endangered PAs cover over 1.36 million hectares, representing 20% of the entire area of all PAs in Madagascar.

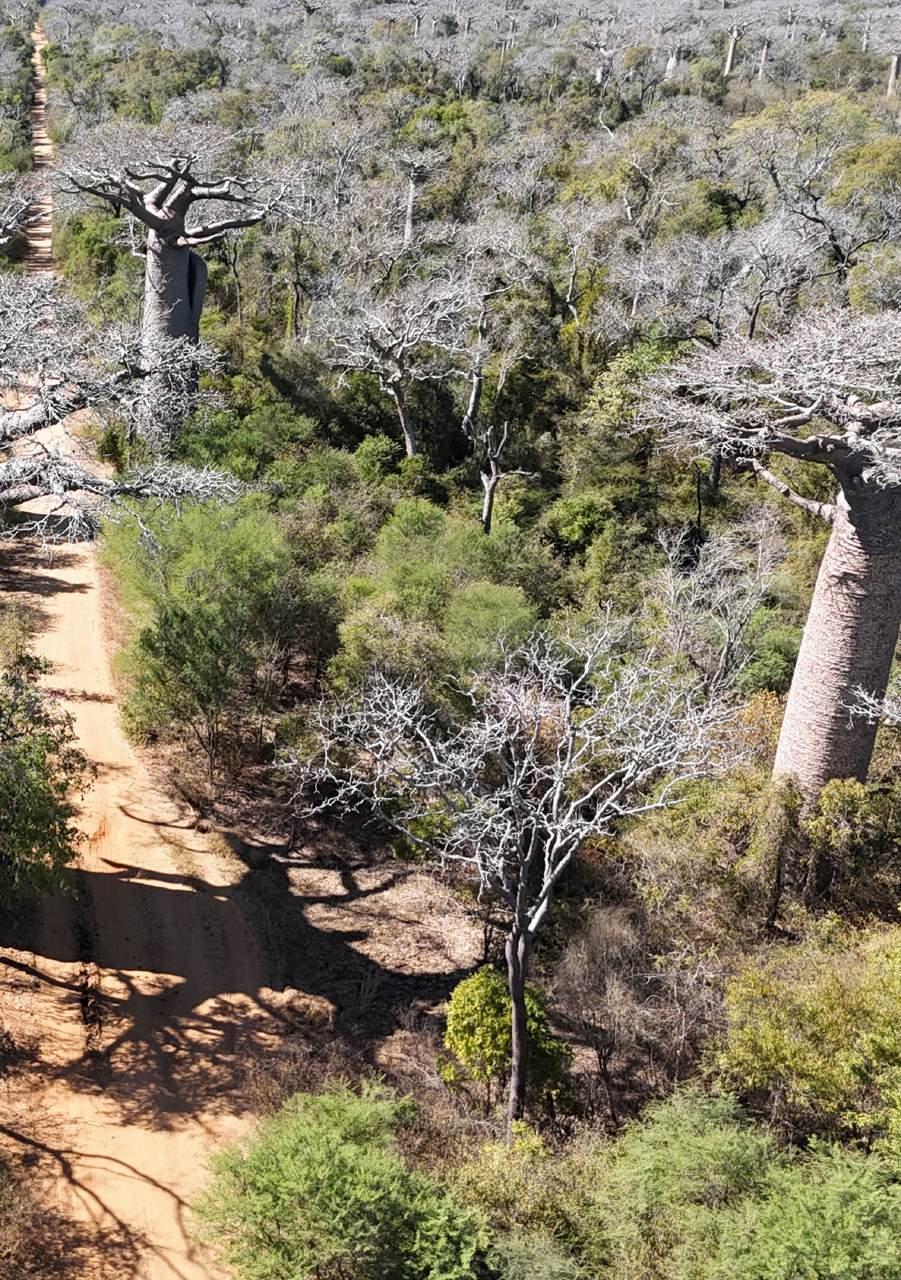

Eleven sites have lost more than 60% of their total forest cover. Allée des Baobabs has lost 90.8% of natural forest cover, although this was almost entirely prior to being declared a PA in 2015. The annual average deforestation rates were 4.46% and 1.04% between 2005–2009 and 2010–2014, respectively.

Since 2019 when major restoration efforts began, Allée des Baobabs has served as an excellent example of a conservation success story with almost zero forest loss with an intense community program preventing fires, restoring forests (especially Baobabs), and locally operated ecotourism.

Of the Endangered PAs, more than 50% are classified as category V (harmonious landscape), where human activities are permitted under control.

Categories IV and VI are also well represented (11% and 22%). Three sites are classified as strict PAs (IUCN Category I, II and III), being Ankarafantsika National Park, Tsaratanana National Park and Allée des Baobabs.

Figure 12: Eighteen Endangered PAs ordered by the >1–2% average annual Forest Cover Loss percentage between 2005–2024 (orange dotted line) and bar chart showing the total forest cover loss at each PA with corresponding color fills: red (Critically Endangered), orange (Endangered) and yellow (Vulnerable).

Vulnerable Protected Areas in Madagascar

A total of 22 terrestrial PAs were classified as Vulnerable (VU) because of annual average forest loss between >0.5–1% per annum (the average across 19 sites was 0.75%). Vulnerable PAs cover 2.30 million hectares, representing 33% of the area of all PAs in Madagascar.

Most of these PAs have experienced significant deforestation in the past, with, on average, less than 51.5% of the original tree cover surviving across the 22 sites (>48% of original tree cover has already been destroyed).

Table 5: Summary of key data related to Vulnerable PAs.

Seven of the 22 PAs were declared in 2015, but since declaration those sites have had an average 0.7% increase in annual Forest Cover Loss over the prior decade (2005–2014). In the past ten years, nine sites have recorded an annual average tree cover loss of more than 0.8%, while only three sites have lost less than 0.5% (Amoron’i Onilahy, Mikea and Tampoketsa-Analamaitso). This category includes five National Parks (Mikea Forest, Kirindy-Mitea, Midongy Atsimo, Sahamalaza Iles Radama, and Zombitse-Vohibasia).

Figure 13: Twenty-two Vulnerable PAs ordered by the bar chart showing total FCL at each PA with corresponding color fills: red (CR), orange (EN), yellow (VU) and green (LC), plus the 1 to <0.5% average annual Forest Cover Loss percentage between 2005–2024 (yellow dotted line).

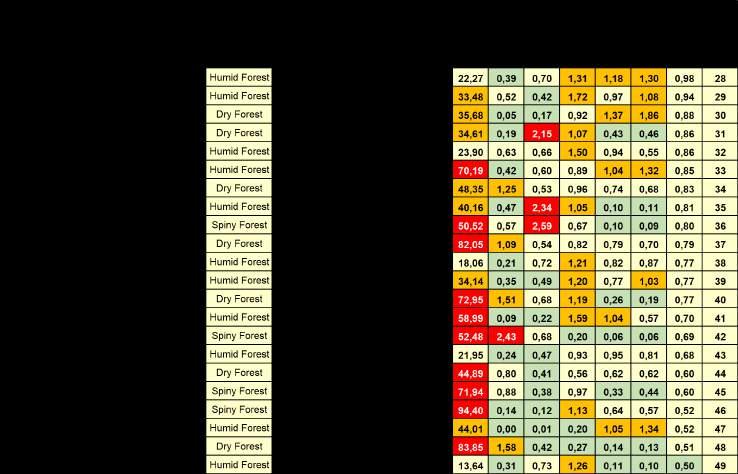

Least Concern Protected Areas in Madagascar

A total of 60 terrestrial PAs, the majority (55%) of all PAs, were classified as Least Concern (LC) because annual average forest loss over the past two decades is below <0.5% per annum (the average across 60 sites was 0.17% per annum). Least Concern PAs cover 2.75 million hectares, representing 39% of the area of all PAs in Madagascar.

A total of 20 Least Concern PAs (33%) have lost more than 50% of their initial tree cover. Only 8 Least Concern PAs have lost more than 90% of all forest cover, which is of concern, except that deforestation has now abated. Since being declared PAs, 7 sites have lost more than 10% of their tree cover.

Almost all Least Concern PAs have seen a stable or decreasing average annual forest

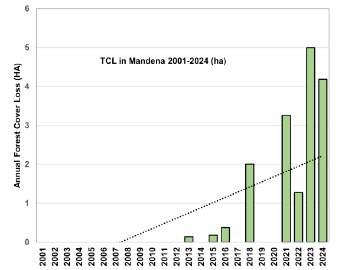

cover loss over the last 20 years, except Mandena, which has seen an increase in deforestation in recent years. However, all these sites are dependent on protected area management to remain stable.

Importantly, 4 Least Concern PAs have not experienced any deforestation in the last ten years. The majority (28.3%) of PAs in this category are classified as IUCN category II (national park), which can be attributed to the regular presence of national park agents and restrictions on human activities. Category V is also well represented (31%), indicating successful management of PAs with local populations. A further two Least Concern PAs have experienced less than 0.05% forest loss over the past 20 years.

Table 6: Summary of key data related to Least Concern Protected Areas including ranking according to average Forest Cover Loss in five year periods from 2004-2023 and deforestation rates from the past three years.

7: Summary of key data related to Least Concern PAs prioritized by Total Forest Cover Loss - all time, at each PA.

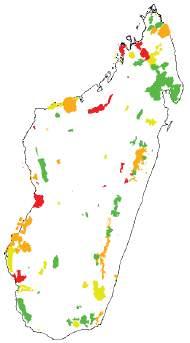

Summary of Priority Protected Areas Requiring Intervention

Applying FCL across five periods together with Total Forest Cover loss within each PA has enabled a transparent and replicable PA Threatened classification system (CR, EN, VU, LC) that can clearly identify PAs in Madagascar in need of additional protection efforts.

To be clear, all PAs are important to protect. But with limited resources for conservation,

CR Critically Endangered

the need to prioritize additional funds for PAs should consider Critically Endangered and Endangered PAs as an imperative for future support. While the majority of PAs are Least Concern, the most threatened PAs (CR, EN, VU) represent over 61% of the total area (4.25 million ha) under protection, highlighting the significant scale of issues facing Madagascar.

For Critically Endangered PAs we draw special attention to Mangabe-RanomenaSahasarotra, Mahialambo, Ampasindava, Baie de Baly, Bora, Ranobe PK 32 (an orphan site with mining interests), and Menabe Antimena.

EN Endangered

For Endangered PAs, eight sites have experienced significant forest cover losses in recent years with uncontrolled, destructive activities. Of those, five are of particular concern: Tsaratanana National Park, Analabe-Betanatanana, Bongalava, Ambohijanahary and Torotorofotsy.

VU Vulnerable

For Least Concern PAs, these sites are generally less exposed to deforestation over the past two decades, which can be attributed to good governance and effective protection strategies, despite significant losses of their initial forest cover that predates their protective declaration.

LC Least Concern

For Least Concern Protected Areas, these sites are generally less exposed to deforestation over the past two decades, which can be attributed to good governance and effective protection strategies, despite significant losses of their initial forest cover that predates their protective declaration.

Priorities by Forest Type in Madagascar

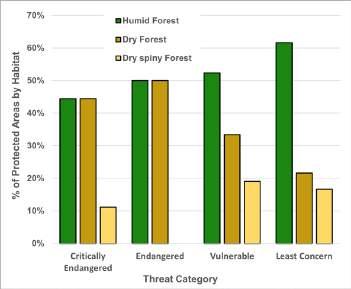

Humid forest comprises 54% of the areas under protection (3.79 million ha), while Dry forest comprises 39% (2.13 million ha) and Spiny forest comprises 15% (1.06 million ha) of PAs in Madagascar. When total Forest Cover Loss is compared across forest types, they are remarkably similar with between 13.8–16.7% lost in each forest type.

A review of the Threat category broken down by forest type highlights that dry forests (33 PAs) are proportionally the most threatened habitat type with >60% having a Threat category (CR, EN, VU). Conversely, two-thirds of Spiny forest PAs (15 PAs) are Least Concern. Ranobe PK32 is an outlier being Critically Endangered, primarily because it lacks a manager responsible for the area. Humid forest (61 PAs or 56% of all PAs) has an 11–15% distribution of sites across Threatened categories with 61% being Least Concern.

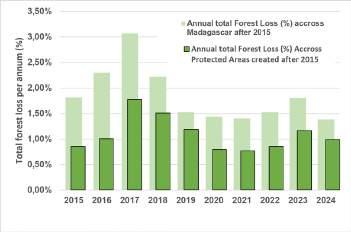

Comparison 2023 vs 2024

Across Madagascar, overall deforestation decreased between 2023 and 2024 with 231,219 hectares lost in 2024 or 1.9% of the country’s total tree cover compared to 2.4% in 2023. The downward trend reflects encouraging progress in addressing the drivers of deforestation at the local and national scale.

These results appear consistent with global deforestation trends across habitats, whereby dry forests are more prone to destruction by large-scale fires. They are also often overlooked, with attention focusing on humid and wet tropical forests that are more biodiverse despite the high levels of endemism in dry forests.

A positive trend was also observed within Madagascar’s 109 terrestrial PAs. In 2024, tree cover loss within PAs was limited to 33,623 hectares or 1.0% of the PA remaining forest area, compared to 1.1 % in 2023. This figure (forest loss) remains half that of the national average (1.0% vs. 1.9%), highlighting the continued role of the PA system in mitigating deforestation pressures.

Performance dynamics of individual PAs

█ In 2024, 57 PAs improved, 35 deteriorated, and 17 remained stable.

█ A total of 13 PAs experienced a shift in their threat status, with 10 showing improvement and 3 deteriorating (see table 8).

█ In many cases, PAs improved their performance without necessarily changing the threat category: 47 PAs lowered their relative rank, suggesting incremental but meaningful reductions in forest loss.

PA Changing Category

Ankarafantsika

complexe Anjozorobe Angavo

Manjakatompo Ankaratra

Threat Category 2023 Threat category 2024

corridor Ankeniheny Zahamena

corridor Forestier Ambositra Vondrozo

kirindy Mitea

Makirovana tsihomanaomby

Ambararata londa

Ambohidray

Ambohijanahary special reserve

table 8: comparison of the threat category changes between 2023 and 2024.

o ne striking case is the Mangaber anomena- s ahasarotra, which while still at the top of the most threatened PAs,

categorized as cr, achieved a substantial reduction in forest loss, from 13.1% in 2023 to 6.0% in 2024.

Protected Areas with Increasing Forest Loss 2023 to 2024 (Deterioration)

Some PAs recorded worsening trends in forest loss, including Bora, Baie de Baly, Ambararata Londa, Complexe Zones Humides Mahavavy-Kinkony, Manongarivo, COMATSA Nord, Bemarivo, Complexe Tsimembo-Manambolomaty, Lac Alaotra, Maningoza, Angavo, Behara-Tranomaro, Vohidefo, Andrafiamena-Andavakoera, Mikea, Tsingy de Bemaraha, Amoron’i Onilahy, Pointe à Larrée, Ambohitralanana, Antsingy Montagne des Français, Beanka, Betampona, Nosy Mangabe, and Oronjia.

Protected Areas with Decreasing Forest Loss 2023 to 2024 (Improvement)

Other PAs demonstrated substantial recovery and reduced forest pressure. Notable examples include:

█ Mahialambo, with a dramatic reduction from 14% in 2023 to 0% in 2024.

█ Mangabe-Ranomena-Sahasarotra, from 13% to 6%.

█ Ankarafantsika from 2.6% to 0.5%.

█ Ambohitantely, ZombitseVohibasia, Manombo, Menabe Antimena, Ranomafana, Makira, Zahamena, among others.

Overall Trends and Interpretation

The 2024 results reinforce the importance of Madagascar’s PAs as buffers against deforestation. While pressures remain unevenly distributed—with some sites facing

intensified threats the general decrease in forest loss, both nationally and within PAs, underscores the value of sustained conservation efforts.

Several factors likely contributed to this improvement:

█ Strengthened PA governance and management, including community-based natural resource management and improved surveillance.

█ Law enforcement and policy measures may have reduced large-scale illegal logging and land clearing in certain hotspots.

█ Increased collaboration with local communities, offering alternative livelihoods and incentives for sustainable land use.

█ International support and funding, providing much-needed resources for conservation programs, capacity building and technology training, essential equipment, and collaboration with law enforcement.

Together, these elements highlight that targeted investments in PA management and broader landscape-level interventions can significantly curb deforestation, even in a context of persistent socio-economic pressures.

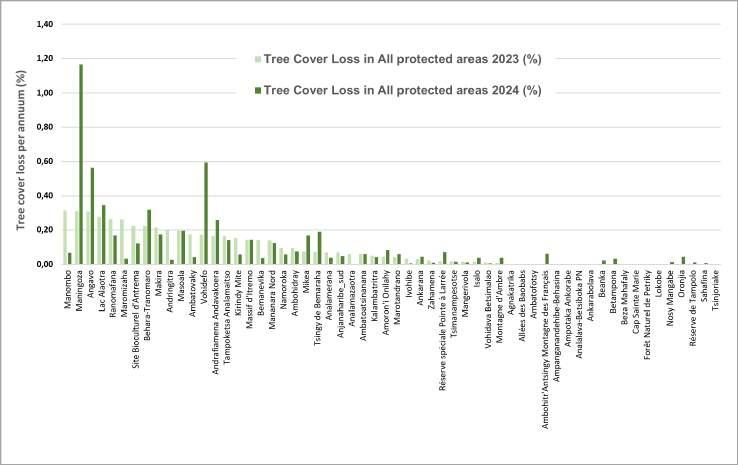

Figure 16 and 17: Shows comparison between percentage of total tree cover lost in 2023 (pale green) and 2024 (dark green) (Data: Global Forest Watch, 2025).

Protected Area Case Studies

Critically Endangered

Menabe-Antimena (Association Fanamby)

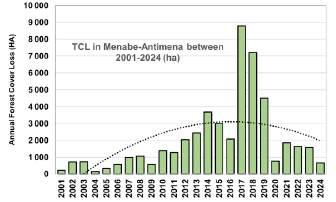

The Menabe-Antimena New Protected Area (NAP), officially designated in 2015 as a Harmonious Protected Landscape (Category V), covers over 209,389 hectares between Morondava and Belo-sur-Tsiribihina (Figure 24). It is managed by Fanamby in collaboration with Madagascar National Parks (MNP), Durrell, CNFEREF (Centre National de Formation, d’Etudes et de Recherche en Environnement et Forestier,) and WWF. It harbors a striking mosaic of dry deciduous forests, coastal mangroves, and inland wetlands, including Lakes Kimanaomby and Bedo, which play vital hydrological and ecological roles. The site is internationally renowned for the Avenue of the Baobabs, an iconic landscape that combines ecological, cultural, and tourism values. Menabe is also a biodiversity hotspot, home to unique endemic species such as Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur (Microcebus berthae), the world’s smallest primate, alongside other globally threatened fauna.

The PA delivers critical ecosystem services—climate regulation, aquifer recharge, soil protection, and food security—while underpinning local livelihoods through ecotourism, beekeeping, rice cultivation, and non-timber forest products. Baobabs also hold deep cultural importance, acting as heritage markers for local communities.

Yet Menabe has faced some of the most alarming deforestation rates in Madagascar. The PA has lost nearly 72% of its original forest cover with more than 44.4% of that occurring within the last 15 years. Between 2015 and 2019, the average percentage of annual forest loss exceeded 5%, with dramatic peaks between 2017–2019 when more than 21,356 ha were cleared in three years. This was largely due to slash-and-burn agriculture, maize expansion, charcoal production, bushfires, and uncontrolled migration.

In recent years, however, stronger management has produced measurable improvements. Community patrols, firebreaks, mixed brigades, and technological monitoring (drones, SMART, GIS) have curbed illegal activities, dismantled hundreds of unauthorized camps, and significantly reduced fire hotspots. As a result, annual forest loss dropped from nearly 1,916 ha in 2021 to 1,569 ha in 2023, and by 2024 the rate of forest loss fell by 58.2% (only 656 ha loss), marking a turning point in site management. Villages actively engaged in fire prevention were rewarded with zebu cattle, incentivizing further community involvement.

Thanks to these interventions, Menabe-Antimena has improved its ranking within the Critically Endangered (CR) category, moving from position 6 to 8. While the site remains CR due to its severe deforestation history—particularly the massive clearances of 2017–2019—the recent progress demonstrates that Menabe could shift to the Endangered (EN) category if current efforts are sustained and expanded. This case highlights the decisive role of law enforcement, community participation, and consistent funding in reversing destructive trends and securing both biodiversity and cultural landscapes.

Critically Endangered

Baie de Baly (Madagascar National Parks)

Baie de Baly National Park, located in northwestern Madagascar near Soalala (Figure 24), covers a unique landscape where dry deciduous forests meet coastal ecosystems. Established in 1997, the park is managed by Madagascar National Parks in collaboration with E-RECODEV. It is internationally recognized as the last stronghold of the Critically Endangered Angonoka tortoise (Astrochelys yniphora), one of the rarest tortoises in the world, and also shelters key species such as the Madagascar fish eagle (Haliaeetus vociferoides – CR) and the Madagascar big-headed turtle (Erymnochelys madagascariensis –CR). The park combines terrestrial and marine habitats, including mangroves, savannas, and coral reefs, making it a site of high ecological and cultural value.

Despite this importance, Baie de Baly faces an unprecedented conservation crisis. By 2024, the park had already lost 66.7% of its original forest cover. Deforestation has accelerated sharply in recent years: over 32% of forest cover was lost in the past five years alone, and in 2024, the park recorded an alarming 14.36% loss (3,347 ha) in just one year. The main drivers include slash-and-burn agriculture, expansion of maize and cassava cultivation, bushfires, charcoal production, and increasing human migration into the park’s buffer zones. These pressures are fragmenting habitats, threatening the survival of its flagship species, and degrading ecosystem services vital to surrounding communities.

Baie de Baly now stands among the most threatened National Parks in Madagascar, with deforestation rates among the highest in the entire PAs system. If current trends continue unchecked, projections suggest that the remaining forest cover could be almost entirely lost within the next decade.

Urgent action is needed: enhanced law enforcement, strong collaboration with local communities, sustainable livelihood alternatives, and targeted international support are essential to halt deforestation. Without serious and immediate conservation measures, Baie de Baly’s unique ecosystems—and the survival of the Angonoka tortoise—are at imminent risk.

Endangered

Torotorofotsy (ASITY Madagascar)

Torotorofotsy PA, covering about 9,787 ha of marshes and surrounding humid forests in the Alaotra-Mangoro Region near Andasibe (Figure 24), is one of Madagascar’s most important wetland ecosystems. Recognized as a Ramsar Site since 2005 and granted national PA status in 2015, the site is managed by ASITY Madagascar in collaboration with Mitsinjo Association and community-based organizations (COBAs), with support from Ambatovy as a biodiversity offset site. This management framework has strengthened local involvement in conservation, patrolling, and ecological monitoring, helping to stabilize pressures on the marsh in recent years.

The site is globally significant for its biodiversity, hosting the Critically Endangered Golden mantella (Mantella aurantiaca), several Critically Endangered lemurs including the Indri (Indri indri) and Diademed sifaka (Propithecus diadema), and rare wetland birds such as Meller’s duck (Anas melleri – EN), the Malagasy pond heron (Ardeola idae – EN), and the Slender-billed flufftail (Sarothrura watersi – EN), one of the rarest birds in the world. Torotorofotsy also provides vital ecosystem services by regulating floods, securing water supplies for local communities, and sustaining downstream rice systems.

Despite its importance, Torotorofotsy has faced severe pressures, including marsh conversion to rice fields, watershed deforestation, artisanal gold mining, and wildlife trafficking. These threats led to extensive forest loss—over 70% historically, with 32% lost in the last decade alone. In the first edition of the Madagascar Protected Areas Outlook , the site was assessed as Critically Endangered. However, management improvements, stakeholders (Mitsinjo Association and community engagement), and a notable decline in deforestation between 2018 and 2022 have contributed to a more hopeful trajectory. Although pressures resurfaced in 2023, the rate of forest loss decreased slightly in 2024.

Reflecting these recent trends and stronger conservation responses, Torotorofotsy has now been reassessed from Critically Endangered to Endangered in this second edition of the Outlook. This shift illustrates that while the site remains fragile, positive management interventions are making a measurable difference. The future of Torotorofotsy will ultimately depend on sustained law enforcement, effective landuse management, and the active participation of surrounding communities to safeguard its unique marsh–forest system and the iconic Golden mantella.

20: Annual forest cover loss in Torotorofotsy from 2001 to 2024.

Endangered

Ankarafantsika (Madagascar National Parks)

Established in 1927 and covering 136,700 hectares, Ankarafantsika National Park located in NW of Madagascar (Figure 24), is emblematic of the challenges facing Madagascar’s PAs. The PA is managed by Madagascar National Parks in collaboration with FOSA Association, Planet Madagascar and Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust. Since the early 2000s, waves of migrants practicing slash-andburn agriculture (hatsake) and charcoal production have driven severe deforestation, compounded by weak enforcement and lack of sanctions. Once forests outside the park were depleted, pressure shifted inside its boundaries. This loss threatens not only biodiversity but also the park’s vital role as the sole water reservoir for Marovoay, the country’s second rice granary.

In the first edition of the Madagascar Protected Areas Outlook, Ankarafantsika was classified as Critically Endangered. By 2023, it had lost nearly 49% of its original forest cover, with more than 33,500 ha disappearing since 2001, over half of it due to fire. The annual loss rate peaked at 4.9% in 2016 and averaged 3.8% between 2020 and 2023, pushing the site into crisis.

However, 2024 marked a turning point. Deforestation dropped dramatically, with only 0.51% (505.9 ha) lost compared to 2.64% (2,598 ha) in 2023, a reduction of over 80% in a single year. This improvement, attributed to stronger law enforcement, fire management, and community engagement, allowed the park’s status to shift from Critically Endangered (CR) to Endangered (EN) in the second edition of the Madagascar Protected Areas Outlook

Despite this progress, Ankarafantsika remains under heavy pressure. Its longterm recovery will require consolidating gains through law enforcement, livelihood alternatives, ecological restoration, and protection of water resources. If sustained, the park could serve as a model of recovery for other critically threatened PAs in Madagascar.

Vulnerable

Mandena (QMM)

The Mandena Protected Area, located 6–10 km north of Tolagnaro (Fort Dauphin) in southeastern Madagascar (Figure 24), covers about 437 hectares of littoral forest and wetlands, one of the rarest and most threatened ecosystems in the country. Established partly as a biodiversity offset linked to mining activities in the region, Mandena is now community-managed through the Mandena Management Committee (COGEMA) and also serves as a hub for ecological research and restoration, with nurseries, seed banks, and reforestation trials.

Mandena harbors unique biodiversity adapted to its white-sand substrate, including orchids, carnivorous plants (Nepenthes), reptiles, and diverse birdlife. At least six species of lemurs are recorded, among them the Red-collared brown lemur ( Eulemur collarisEN) and the Southern woolly lemur ( Avahi meridionalis - EN). Despite its small size, the site plays a critical role in safeguarding the last remnants of littoral forest in the Tolagnaro region and provides opportunities for ecological research and environmental education.

For two decades, Mandena maintained relatively stable forest cover, losing only 6.3% of its forest. However, pressures have increased sharply in recent years: over 4% of the total forest loss occurred in just the last three years, reflecting a continuous rise in deforestation. This deterioration is mainly linked to agricultural expansion, fuelwood collection, and increasing human pressure around the site.

In the first edition of the Madagascar Protected Areas Outlook, Mandena was assessed as Least Concern due to its relatively good ecological state and effective community management. However, the recent surge in forest loss has undermined its resilience, leading to its reassessment as Vulnerable in the Outlook 2024.

Mandena illustrates both the potential and fragility of small, community-managed reserves. While it remains a critical refuge for Madagascar’s littoral forests, its rapid decline in the past three years shows the urgent need for reinforced law enforcement, sustainable livelihood alternatives, and continued investment in ecological restoration. Without stronger measures, this unique ecosystem risks further degradation despite its global conservation importance.

Figure 22: Annual forest cover loss in Mandena from 2001 to 2024.

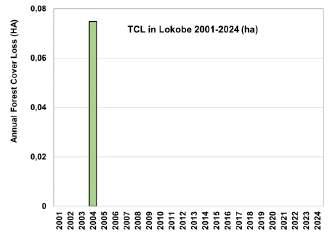

Least Concern

Lokobe (Madagascar National Parks)

Located on the island of Nosy Be in northwestern Madagascar (Figure 24), Lokobe National Park is the only remaining primary forest on the island and a stronghold of the Sambirano ecoregion. Covering 847 hectares, it shelters rich biodiversity, including the iconic Black lemur (Eulemur macaco ), numerous reptiles, amphibians, and rare plant species. Beyond its ecological value, Lokobe stands out as the best-preserved PA in Madagascar, ranking 109th out of 109 PAs in the Outlook 2024 assessment—because over the last 20 years, no deforestation has been recorded.

Lokobe’s exceptional conservation status is the result of an interplay between cultural, legal, and community-based mechanisms:

█ Cultural Heritage: Declared sacred centuries ago under Malagasy royalty, Lokobe was placed under “ala fady” (taboo) protection by Queen Soanaomby, with King Andriamaitso buried within its forest. This spiritual reverence has long discouraged destructive practices.

█ Legal Safeguards: Lokobe has been formally recognized and managed as a National Park under Madagascar National Parks, ensuring institutional protection.

█ Community Collaboration: Local communities are central to safeguarding the park, enforcing taboos, participating in management, and benefiting from sustainable practices.

█ Eco-tourism: Lokobe is a leading eco-tourism destination on Nosy Be. Guided visits, canoe access, and wildlife experiences generate income for local communities, creating incentives to preserve the forest.

█ Modern Management Tools: While tradition provides legitimacy, management has also embraced monitoring, surveillance, and education to ensure longterm resilience.

Lokobe exemplifies how tradition and innovation can converge to achieve durable conservation. Its resilience over two decades contrasts sharply with the alarming trends in most of Madagascar’s PAs. However, sustained vigilance remains necessary, especially as pressures from tourism growth and surrounding land-use change could eventually spill over into the park.

Lokobe is a living example of how cultural taboos, community stewardship, and sustainable tourism can complement legal frameworks to halt deforestation. It offers valuable lessons for other PAs in Madagascar: when local values align with modern conservation strategies, even small, vulnerable ecosystems can achieve long-term protection.

Outlook Conclusions

Madagascar’s terrestrial PAs remain the last critical refuge for >99% of the island’s extraordinary endemic biodiversity. Encouragingly, forest loss inside PAs has declined between 2023 and 2024, and ten PAs have improved their threat status thanks to targeted PA enforcement, community engagement, and leadership. These successes confirm that effective protection is possible when adequate measures and resources are in place.

However, overall, the outlook remains fragile. Almost half the PAs continue to face escalating pressures from slash-and-burn agriculture, charcoal production, illegal logging, and artisanal mining. Poverty and rapid population growth exacerbate these threats, but a critical underlying factor is the limited enforcement of existing environmental laws combined with a lack of PA funding.

Without credible deterrence and resources, even well-managed PAs are at risk.

Looking forward, the future of conservation in Madagascar depends above all on strengthening law enforcement and longterm funding streams . Clear boundaries, consistent patrolling, and effective prosecution of environmental crimes are essential to protect what remains. Enforcement is not an alternative to community engagement but its foundation: without strong legal safeguards, it risks being undermined by unchecked deforestation.

To achieve this, the Annex outlines how “Conservation Brigades” are being deployed to save PAs and safeguard communities. In summary, several steps are imperative:

█ Reinforce law enforcement capacity by ensuring well-trained, adequately equipped forest agents and joint patrols with law enforcement where needed.

█ Strengthen judicial collaboration so that nature crimes are not treated lightly but lead to real sanctions that deter future infractions.

█ Secure sustained funding for enforcement, especially where threats are greatest.

█ Pair enforcement and reduced deforestation and fire alerts (GFW data) with community support and partnerships, so that local populations are empowered as co-stewards.

█ Embed enforcement within national and international commitments, positioning Madagascar as a leader in demonstrating that biodiversity protection requires both people-centered approaches and strong legal safeguards.