Copyright © 2025 Conceptions Southwest

Published by the Student Publication Board

The University of New Mexico

All rights revert to contributors upon publication

c/o Student Publications

MSCO3-2230

1 University of New Mexico

Albuquerque NM 87131-0001

Printed by Starline Printing Company

7777 Jefferson St NE

Albuquerque NM, 87109 505-345-8900

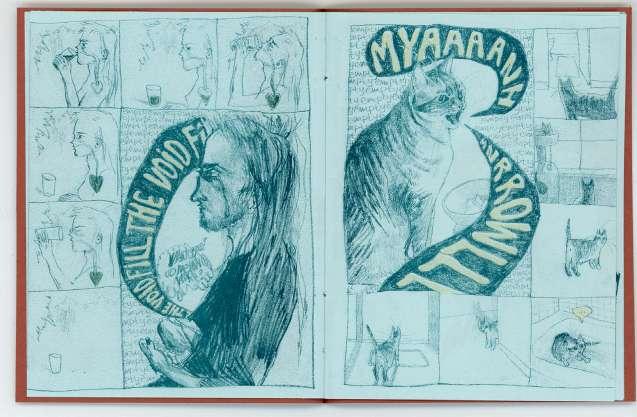

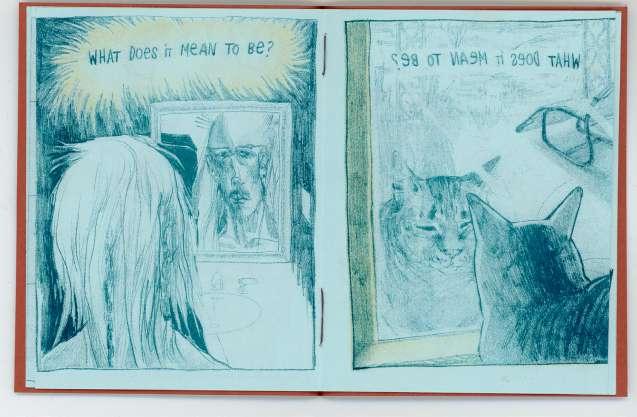

Cover design by Raychel Kool

Cover image by Anna Yarrow

Interior design by Kelsa Mendoza, Raychel Kool, Isabella Young, and Morgan Tracy

Fonts: Mongolian Baiti, Masqualero Groove

Conceptions Southwest is the fine arts and literary magazine created by and for the University of New Mexico community. Conceptions Southwest staff consists entirely of student volunteers directed by an editor-in-chief selected by UNM’s Student Publication Board. Submissions are accepted from all UNM undergraduates, graduates, continuing education students, faculty, staff, and alumni. This issue is brought to you by the Associated Students at The University of New Mexico (ASUNM) and the Graduate Professional Student Association (GPSA).

Copies and back issues are available in the Daily Lobo Classified Advertising Office, Marron Hall, Room 107. The Conceptions Southwest office is located in Marron Hall, Room 225. To order copies of the magazine, please contact csw@unm.edu or visit www.csw.unm.edu.

Breathe it all out as stardust and art.

-butterfliesrising

Founded in 1889, the University of New Mexico sits on the traditional homelands of the Pueblo of Sandia. The original peoples of New Mexico – Pueblo, Navajo, and Apache –since time immemorial, have deep connections to the land and have made significant contributions to the broader community statewide. We honor the land itself and those who remain stewards of this land throughout the generations and also acknowledge our committed relationship to Indigenous peoples. We gratefully recognize our history.

KelsaMendoza,Editor-in-Chief

he vulnerability from thousands of artists has compelled Conceptions Southwest onward for forty-eight trips around the sun. Throughout my time with this supremely special publication, I have witnessed so many works that shimmer with honesty, risk, and imagination. For yet another edition, I am stunned by the new ways in which our community puts words to a feeling, captures an experience, and makes us live a thousand different lives.

To my beautiful editors, Raychel and Isabella: working beside you has been my greatest dream. Both of you are a never-ending source of inspiration for me, and I hope to see where the stars lead you next.

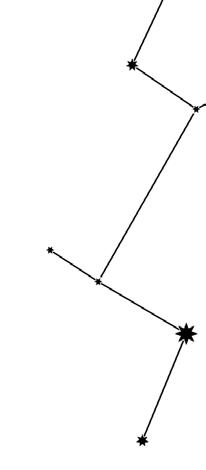

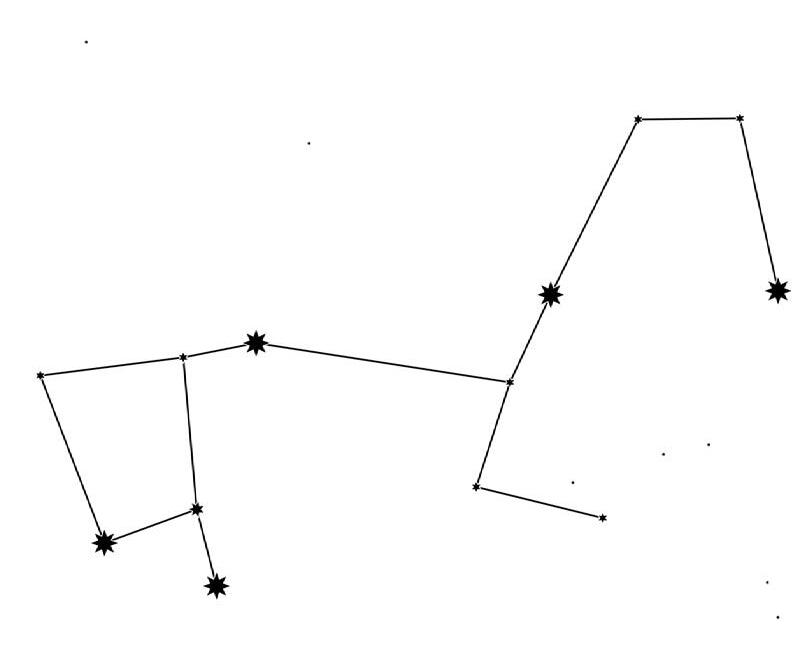

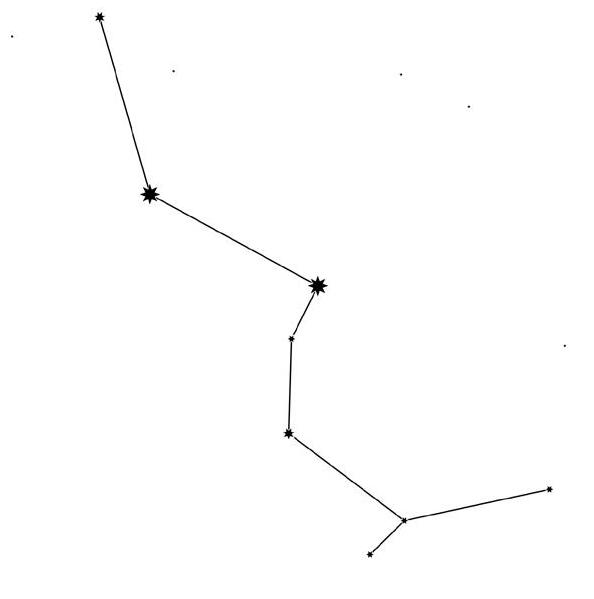

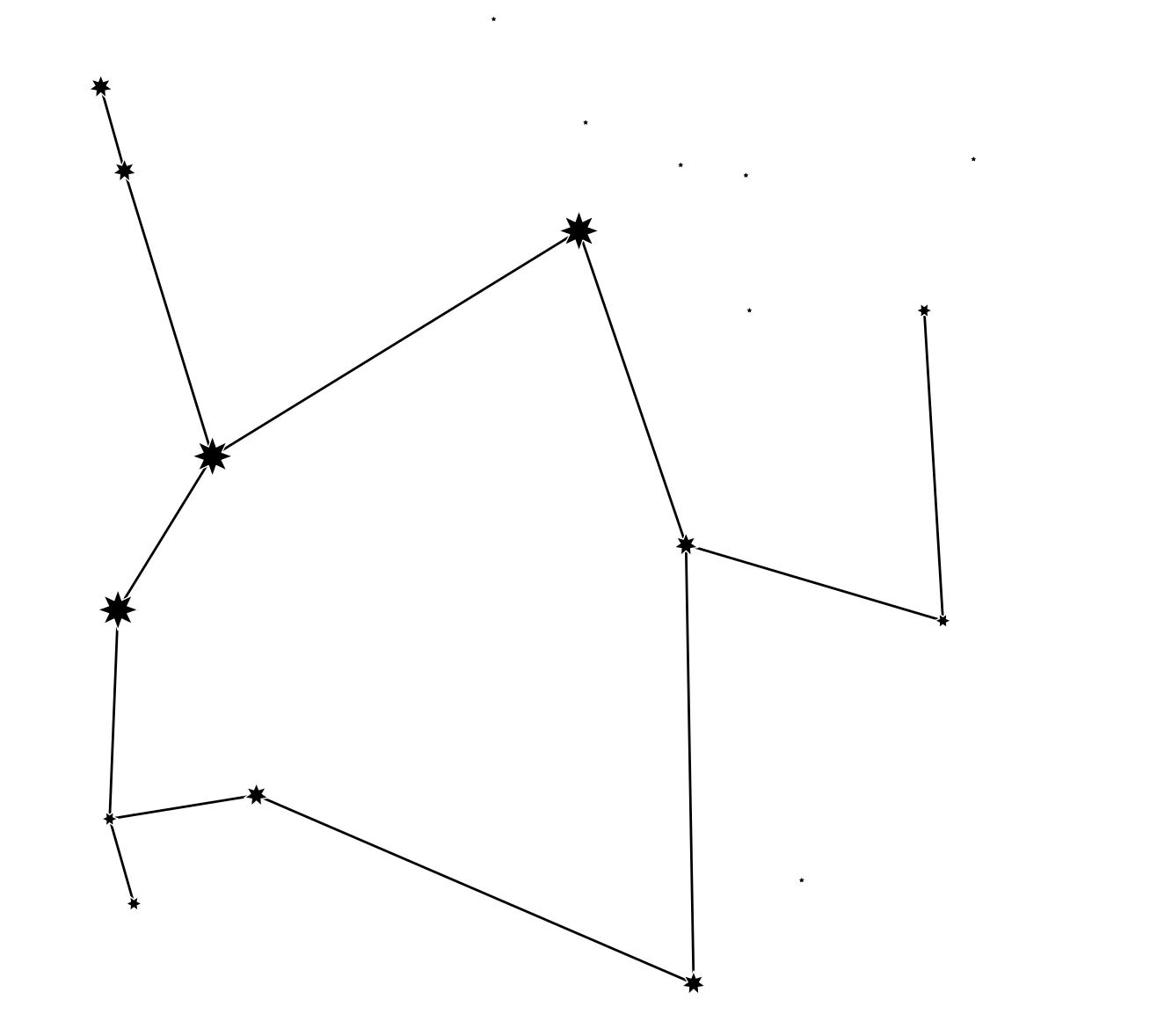

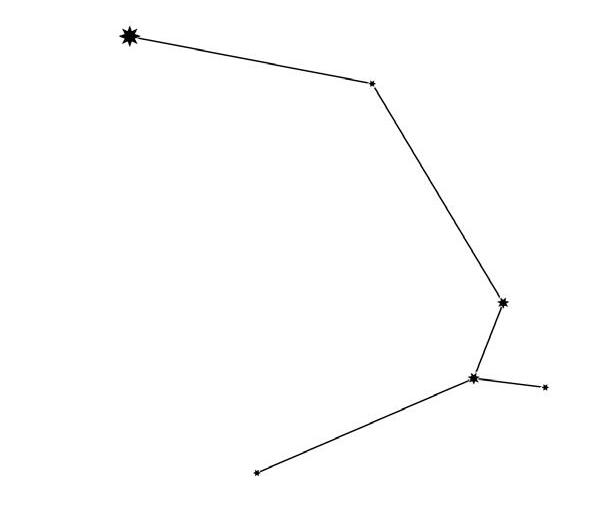

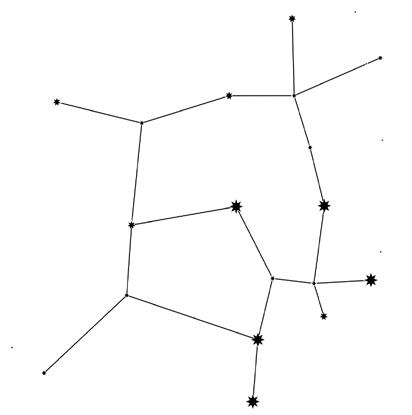

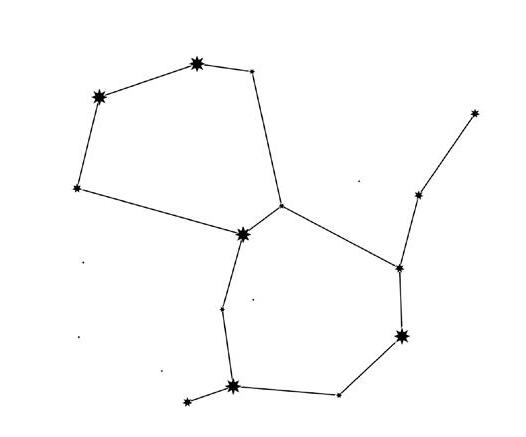

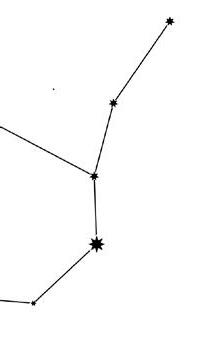

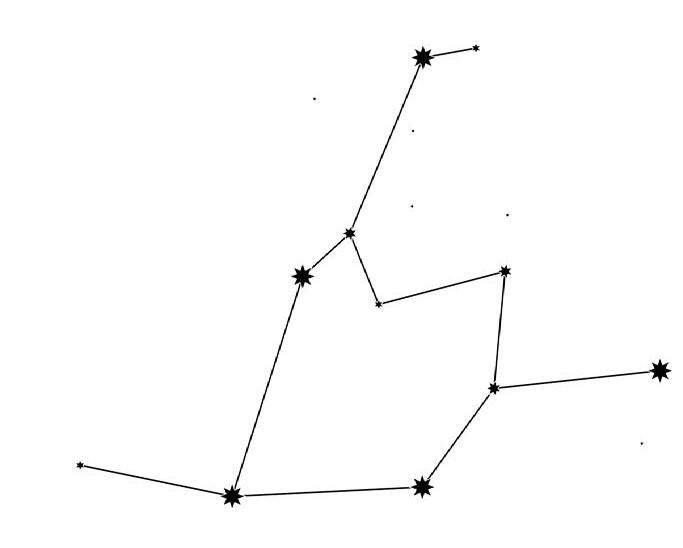

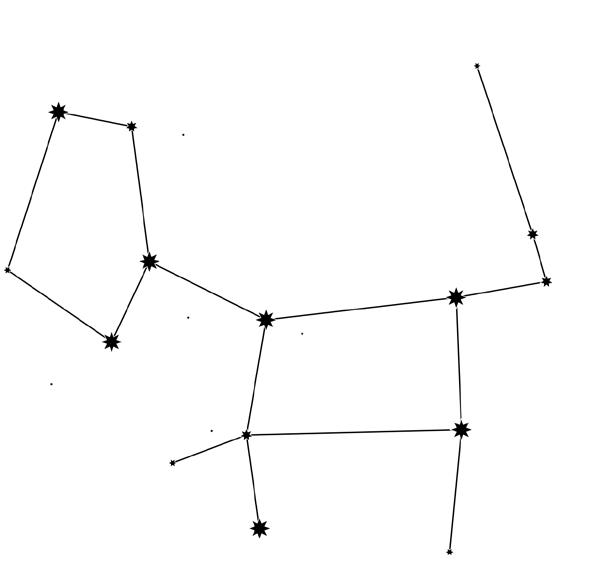

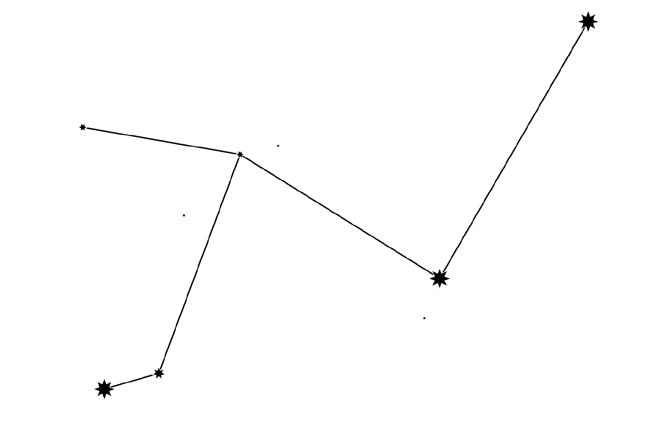

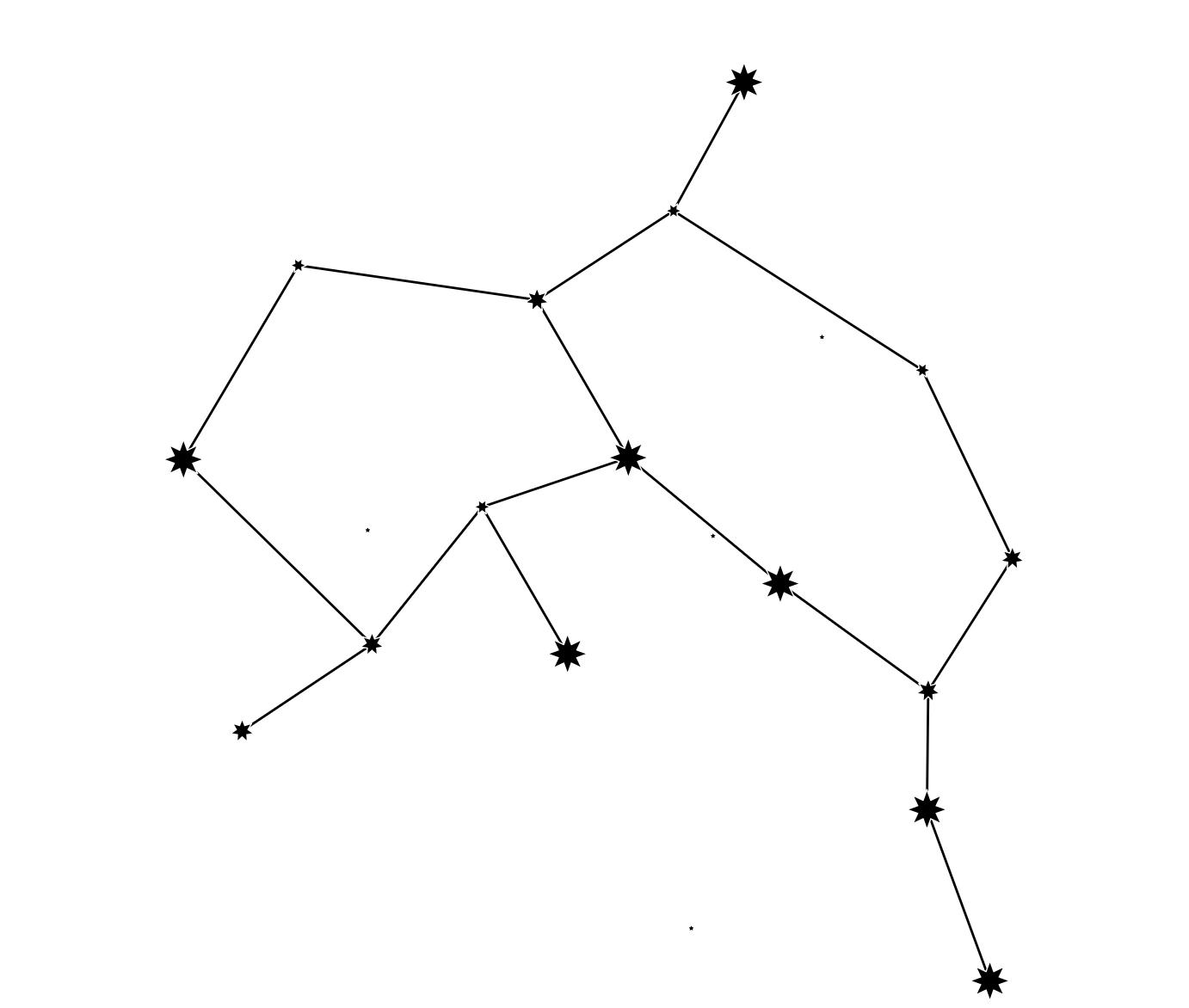

Every year, this is proof to me that all our contributors are connected, and we, as the staff and editors, are connected to them too. Using the threads that bind us together, we find meaning in all of this vastness. On our own, we glow. Together, we map a constellation of different stories. Our staff, although small, curated this edition’s contents with love. Seeing everyone’s different creative skills emerge is what makes this process so special. To all of you who helped make this happen, I loved knowing which pieces spoke to you and why. I loved every vision you had for this publication. This is your baby as much as it is mine.

Raychel, I will always look up to you as my friend, a teacher, and my favorite artist. You are as real as they come, and this edition would be nothing without you.

Isabella, your strength and determination are a pillar to everyone around you. Everything you touched this year became magic, and I am so honored to have watched that unfold.

To all that read this magazine, thank you for giving power to those who express themselves here.

May you find something in these pages that lights your way, however briefly.

Poem for Jesse Pinkman

El amor todo lo puede:

The Surgery

Dog Head Woman

Birth of Pearl

Stopgapping

You or Someone Like You

Nell Johnson

Savina María Romero

Nic Hinson

Sophia M. Eagle

Renata Sophia Amaris Gonzales

Nic Hinson

Nell Johnson

Stage Directions/Transubstantiation

Coins

Timelapse

Birdcage

Ferried/The North Sea

Summer’s End by the Falls

A Solaz

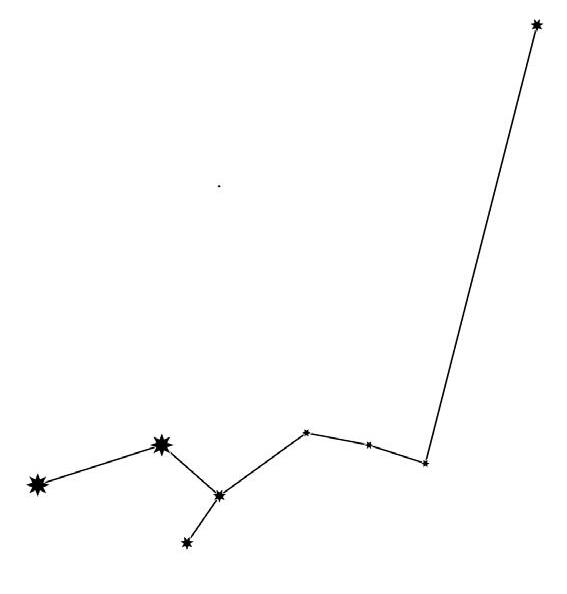

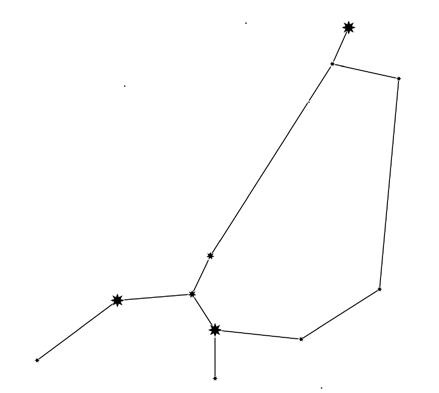

On the Ways We Scale the Universe

Nell Johnson

Nell Johnson

Drew Sowers

Erin Benton

Erin Benton

Erin Benton

Savina María Romero

Victoria Nisoli

On the Ground and in the Air

The Life of a Dying Man

The Fabled Astronauts are Remembered

The Wasp and the Roach

Nic Hinson

Kimberly Scott

Addison Key

Thomas J. Crowe

Justine Witkowski

Addison Fulton

Rudy Carrillo

Colton Campbell

Soda, Coke, or Pop?

Death Before Detransition

Am I Stupid or Something

Cunt

Patrona Santa Frida

Eater

Reyes Reynaga

Reyes Reynaga

Claudia Valeria Marin X E Oaks

Isabella Romero

Viola Murphy

Limited Opportunities in a Boundless, Fullfilling Life; El Trastorno Alimenticio Silencioso

Chimayo

Tierra y Libertad

Pueblo Roots

Santa Lucia White Fires

Valeria Hines

Isabella Romero

Blanca Bañuelos-Hernandez

Tide in Timelapse

A Chair in a Yard

Tucked Away (1)

Tucked Away (2)

Tucked Away (3)

We Felt Butterfly

Circle of Life

Studies in Protest (1)

Studies in Protest (4)

Truchell Calabaza

Adrian Allocca

Leo Brocker

Drew Sowers

Drew Sowers

Sachi Barnaby

Sachi Barnaby

Sachi Barnaby

Anna Yarrow

Anna Yarrow

Jimmy Himes-Ryann

Jimmy Himes-Ryann

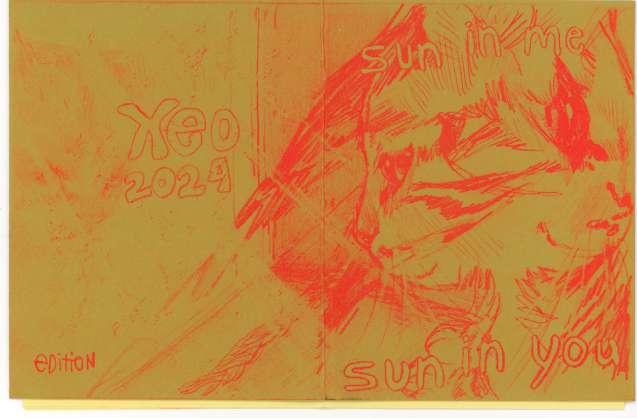

Casa Luna Sun in Me, Sun in You X E Oaks

Sydney Hopkins X E Oaks

yellow-gold, you were wood-carved boygirl in a beanie 311 in the 505 pushing dope in the alley behind Frontier where gas glittered on the asphalt for you, Golden Pride, red chile, never cayenne. In Santa Fe, eggshells and yellow petals swim on canvas. You’ve always had bad trips; you’ve opened so many doors, seen Anything, watched those mountains burn around you like cramps, green birth you never wanted, and known yourself as yellow, yellow, yellow, yellow coming around the mountain, yellow coming around the mountain road now,

foamplateprintsonpaper,8.5”x5.5”

Here we are.

Of plastic prayer beads, and stories of miracle cures of spit and mud, Of herb bundles and egg remedies and cut potatoes on naked skin for fevers.

Here we are.

Of old cookie tins to hold sewing needles, of soft Blue Bird flour sack rags, Of quilts of old flannel sleeves and cotton tablecloths, stuffed with rag bits for winter.

Here we are.

Of summer wind chimes fashioned from old coke cans and super glue, spinning scratchy, Of little crosses of wood or husk, or palm or scrap, or metal bits off broken cars.

Here we are.

With a hand in the pocket, and a rosary in the hand, as we wait for busses or wash countertops— Gracias a Dios. Gracias a Dios. Diosito de mi vida. Gracias a Dios.

Here we are.

Scalpels unwound the papier-mâché of your body. Slips of paper were stripped back, Slick from inked headlines, Local anesthesia, national news.

Something inside is beating

Oh doctor, what appears there?

Editorials scarred into Bloody cardboard tubing?

Sterile, gloved fingers dipped into glue

Anoint your slack body like a baptism, Mad-made shapes

Misalign the words on your skin.

Cremains of old news

Fill the dumpsters out back

Like paper shreds of past lives, Birth certificates and credit cards.

Headlines are reconstituted

Like ransom notes

For your new body, Your body, the news.

Ikeep all my old journals and sketchbooks in stacked cardboard boxes like monuments to my prepubescence. I read through them when I’m stricken by self-hatred. I look for the little girl who wrote them and try to feel sympathy for her. I think I feel it. She’s somewhere inside me, maybe. She’s alive somewhere inside me, maybe.

• • •

I wrote my first diary entry in fourth grade when my English teacher (who was also my math, history, and science teacher) assigned it to me. The prompt was: What would you do on your perfect day? Mine contained thrilling details such as sleeping in, getting ice cream, and becoming the temporary president of the United States. My perfect cursive helped mask the occasional misspellings.

In red pen at the top: Great work! Veryimaginative. What a rush. I still have it. I still read it. It rests between the covers of a tattered, black composition notebook, aching and hopeful. The friction of the pages blurred my pencil marks, but that red pen stayed. • • •

When I was eleven, underneath the yellow LEDs of my ceiling light, I would write stream-of-consciousness ramblings to appease my scared, dumb animal brain. I would focus on the wobbling sound of my pen, never lifting it from paper and never looking down at the page. My dry, unblinking eyes were trained on the small brown door to my room, closed but not locked. I had long since memorized the wood grain. Only the small box of my room was safe from the night, illuminated by a shivering golden bulb. My brain kept telling me: Someone’s waiting outside the door. They can see you. They can hear your soft child breaths. They willhurtyou,eveniftheydon’twant to. They’re going to come in.

I thought that, by writing my nonsense down, some of it would stay

on the page. Purifying automatism. By writing it out, I could banish the part of myself that was convinced of constant danger. Being scared was a near-inextricable part of me. I wanted to stop being scared.

I have this memory that I can’t place in the timeline of my life. Having been told and retold so many times, the story has slipped and fell between years. This is how my dad tells it: Whenyouwerelittle,youhadthis teeny-tiny notebook. You used to write in incredibly small script that I could barely read. One day, you handed this notebook to me with a tiny poem scrawled carefully in pencil. I asked you, “Where did you copy this from?” and I remember you got offended. “I wrote it,” you said, andthepoemwassotouching,so intelligent, so beyond your years thatIbarelybelievedit. He tears up at that last part. This feels like gross parental exaggeration to me, to the point that I get embarrassed whenever he tells it. I don’t remember the poem at all. I wish I did. What precious part of me

snuck out of my soul and onto that page?

For a short period in middle school, I was doggedly focused on filling entire sketchbooks as fast as I could, wanting to catalog my fumbling journey to becoming a “real artist.” They need to be cohesive andthemed,Ithought.They need to have the same color scheme. This is my blue period, like Picasso. They needed to clearly showcase my level of skill so I could compare them, obsessively, with younger and older works. I dedicated myself to auto-vivisection. Over and over, I tore myself apart. What did this progression say about me? About my journey? Stagnation was a brick wall pressing against my back. Every second not spent improving was wasted. Still, I couldn’t help wasting. I spent days in bed, staring down

my popcorn ceiling, ruminating. Wallowing. I kept expecting the surface tension of my body to break open and dissolve into the old mattress, the white sheets, the damned popcorn ceiling. I felt the air falling on my chest like silt settling in water.

Not able to bear the thought of deterioration, I justified this slow dissolution as “filling up the tank”: I couldn’t take part in the act of creation without sacrificing some part of myself. I had exorcised too much of my soul and lay fractured and pathetic. This is regeneration. I’m hibernating to become whole. Then, when I’m whole, I can again give myselfaway.

• • •

One Christmas in high school, a friend that I don’t speak to anymore gifted me a small notebook with a brown and gold cover. A red ribbon bookmark nestled gracefully between

the cover and the first page. I didn’t touch it for the better part of a year. Once I did, I became ebullient, boiling with life. Words danced across pages in big loopy scripts—stretching moments into immortality, cementing minor emotions forever in writing, important and lovable. I would set the pen down and reread them over and over again, trying to understand what I was. The person who wrote it seconds ago had flown out of me. Reading it was a dialogue between myself and a stranger I was intruding on, like I walked in on them while they were changing, metamorphous. Wet ink ran insipidly on blemished cream pages. The words lay dead.

I have so much disdain for my reader and the reader is myself, roving over my body (of work) interminably, being proud of it and hating myself, and wanting to write something better, and not writing except when it’s required, or when it’s these stupid fictionalized diary entries that I’ve crammed full of loathing, rationalization for my loathing, and masturbatory groveling at the feet of my loathing. I wanted to write it down to get it out of me—to make something beautiful. Or educational.

Or real. I’m thinking of changing the font size so this looks longer, like there’s more of me.

If I stop writing now, this version of me shrinks and crumbles away. I savor final paragraphs like last meals. I’m getting smaller now, withering as I run out of things to say. Words, newborn fragments of my soul, dither in the pale hope that the sentence isn’t over. I don’t want to die.

• • •

I might do the same. I might tell them that their body can grow with them, that their body is alive (even if they can't feel it), that their soul won't break

I’m thinking of changing the font size so this looks longer, like there’s more of me.

In ninth grade, a teacher sent me to the guidance counselor’s office because I turned in a poem about my soul outgrowing my body. I was angry at the time. In her warm, circular office, the guidance counselor asked questions like, “What’s going on at home?” and “Are you okay?” I stared at the pitch leaves of her potted fern and lied.

Why should I be punished for putting myself in my work? For honesty?

Now, if I had a student who told me that their body was crushing them, that they felt stifled by growth, that their skin was only a fragile layer between themself and nonexistence,

open. I'd sit listening, hands at my sides, feeling rushes of air penetrate my lungs and circle through me, quiet and living.

I’d known Rain Yates my whole life, but only in the way that everyone knew the Yates family for raising at least a third of the drunks, perverts, and felons of Lusitania, Kentucky. We never actually talked until the summer my mom left. It’d been a long time coming, but I still hoped that wherever she was, she was suicidal with guilt for leaving me two days before I graduated high school, along with my twelve-yearold sister and a seven-month-old infant. It drove my old man crazier than he already was, and on the nights he actually found his way home, he was out of his mind. There was one time when he told my sister he’d set the house on fire with all of us inside it, drive off, and start a new life by himself. He got as far as soaking a rag with Pine-Sol and cramming it into an old Heaven Hill bottle before passing out on the kitchen floor while looking for a lighter.

I knew I should’ve been acting like an older brother and taking care of the girls, but I just couldn’t do it. I wanted the hell away from that house and everyone inside it, so one night, I walked nearly three miles over

hills and briars to Greene General Store and bought a forty instead. I sat down at the edge of the gravel parking lot and opened it right there, watching as the occasional semi rumbled by. It was a Sunday, and at that time of day, truckers were about the only ones you saw until you hit the 60. It was between them that Rain’s beater truck came crawling up the little hill Greene’s was situated on. He drove the same asbestos-blue Ford Ranger that Cathy Stratton’s son used to drive, only it had sat in Cathy’s front yard for five years before Rain slapped a couple grand in her hand and bought it. From what I’d heard, she actually took good care of it until her son came back from college one Christmas and told her he was gay. After that, Rain probably could’ve just stolen it, and she wouldn’t

have cared. I sometimes wondered how much of that story was true, but didn’t care much either way. I just wondered if the fenders had been missing before or after he bought it.

He didn’t see me until he came out with three cartons of cigarettes under one arm and a case of beer with the other, looking like a jackass in his white t-shirt with the neck cut out and a pair of neon green and orange swim trunks squeezing his muscular legs.

“Good time for a cold drink, man. It’s hotter than two rats fucking in a wool sock out here,” he said to me, throwing the beer in the back of the truck. He had a bunch of other shit already piled up back there like he was going camping. “Thought you lived across town.”

“I do.”

“What, then?” He rubbed the back of his buzzed head.

“You walk here?”

“Just needed to get out,” I said, taking another sip. The glass stuck to my lips and the beer was already getting flat. “Beats being at home.”

Rain nodded like he was pondering something serious. “I get that. You’re there with them two little girls, right?”

“Yeah. Old man’s no help either. Fucking drunk.”

“Wonder what that makes you.”

“Probably another drunk.”

He was quiet for a minute and picked at one of the carton’s flimsy tabs. “I was just screwing around up north of the holler a few months ago and came across an old pole shack. It’s right along the river so I wanted to wait until the weather got warmer and see what it’d be like to camp up there. You can come with, if you want.”

The answer was yes before he’d even finished talking. The state I was in, I would’ve hopped in a truck with anyone who didn’t share a last name with me. It was even better that Rain was basically a stranger, because as long as I was with him, I could be no one. I didn’t have a life

or an obligation to anything, and as I climbed into the seat next to him, I found more comfort in that limbo than I ever had in my own bed. • • •

The pole shack was busted and dry rotted when we got there, built out of bloated, gray wooden slats with screens nailed over glassless windows. I pulled a mummified raccoon from one of the darker corners and Rain had me toss it into the river. I stood on the bank and watched it float for a few seconds, swirling in gentle circles over a calmer bit of water before sinking. Hanging from one of the oaks beside me was a girl’s t-shirt, probably pink before being worn down to a murky gray by the elements.

his shirt and swung it up onto the same branch the shirt had been hanging from. A blown-out barbed wire tattoo encircled his right nipple and seemed to move in every direction

I didn’t have a life or an obligation to anything...

he did. “Doesn’t really matter, though. Whoever’s it is ain’t here no more. We’re men. We gotta make it ours.”

“Sure,” I said. “You don’t think anyone’s gonna come out here looking though, do you?”

“Looks wound up there pretty good.”

“Damn right it is.” He grunted, snatched it down, and tossed it into the river. Unlike the raccoon, the water carried it downstream and out of sight.

“You see anything like that the last time you were up here?”

“I don’t think so.” Rain took off

“You worried about that?”

“I don’t know.” I shrugged. “I just don’t want to steal someone’s spot.”

“I don’t think anyone’s coming and going from this shithole except us. It’s all good. I’ve got something for you though. Close your

eyes and hold out your hand.”

I did as he asked, listened to him dig around in the pocket of his trunks for a

...when I opened my eyes, I was holding a little pile of psilocybin mushrooms.

second before something light and dry hit my palm. At first, I thought he was fucking with me and just put some dirt and driedup weeds in my hand, but when I opened my eyes, I was holding a little pile of psilocybin mushrooms.

Rain grinned at me through a set of cigarettestained teeth. “Like I said, man, ain’t no one here but us.”

• • •

I spent most of that summer in the pole shack high out of my mind. My favorite little trick was to take a gob of peanut butter,

spread it between two pieces of bread, throw a handful of mushrooms in between, and eat it like a sandwich. Rain laughed at me for it, but it was the only way they didn’t taste like dog shit. He chewed on the caps as they were, often enough that I only saw him eat real food every couple of days. I was already skinny as a rail; the only real dramatic change I went through was my hair growing down to my shoulders. Rain, on the other hand, was shrinking in his clothes, and there were times it felt like he was haunting the place more than he was camping in it.

In a way, we were both ghosts—it was September, and no one had come looking for us. I could’ve lived like that forever, haunting Lusitania until all that was left of me was a t-shirt hanging from a tree. Being lost to time felt like the best thing to be then, and I believed we could actually do it.

One night, I even told him so.

“We should just stay here,” I said. “Maybe go into town when we start running out of provisions, but that’s

all. Just live up here and not have to be anyone.”

Rain sucked his teeth. “Sounds heavy.”

“Not really. Not like there’s much back there for us anyway.”

“Can I tell you something, Vern?” I held my breath. “Sure.”

“I ain’t told my folks or no one about it, but I got a floorhand job lined up on a field just outside Odessa.”

“Odessa…” I echoed. “That’s Texas, right?”

“Yeah.” He suddenly sounded guilty. “I gotta be there by the end of next week. It doesn’t have to stop you from staying, though. You can still figure out whatever shit you got going on, you know?”

Like I had any reason to stay there if he was in fucking Texas. I tried to picture what kind of trees grew out in a place like that. If there weren’t any, a rig, with his shirt tied around it in some eyesore of an oil field. A naked oak along the riverbank in our lonely stretch of Kentucky. Suddenly states apart. Gone forever. Hypocrite. Traitor. Lying piece of shit. “So, what? You’re just gonna leave?”

“It ain’t personal. This summer’s

been one of the best I’ve ever had.” He sighed. “My family’s been living and dying in this holler since the Civil War, man. I just gotta get out. Be something, you know?” I said nothing, scratching at the mosquito bites that encircled the protruding joint of my ankle. Be something, I thought. What anawfulthingtowant.

Dog Head Woman, asleep

Or dead at the bus stop. Your eyes are glass, dark taxidermy marbles,

Head of a northern dog, Brown twisted body of a woman, Laid on the hot pavement,

Stare at the traffic passing by, Blank and unaware.

Dog Head Woman, dark skin,

Skin of Crazy Horse, face of wolf, Body of the sinner, body of sins, Did you think you'd make it here?

Your kids look for you In every pack of rez dogs That run wild in the hazy afternoon,

But you're none the wiser, Dog Head Woman, You ran far away and what of it?

A white woman could love you, But not your heart, not your hands, Only the ears, the snout, the innocent part of you,

Dog Head Woman, asleep on the pavement, Or Perhaps Mercifully Dead

Ignored at the bus stop, in the city, on a busy afternoon.

In Moscow, the sun never seems to shine. As Oscar and Juliette step off their plane onto the wet tarmac, the rain pours down. Juliette opens a black umbrella; it unfolds and blocks out the already weak sun but does little to protect her face from the stinging, bitter rain, whipped by the wind. Her wet hair gets into her mouth. It’s November. She’s got wool mittens for nuclear winter.

Oscar has no umbrella, nor enough hair to get wet or get in his mouth. Though he is in the military no longer, he keeps his hair buzzed close to the skull. It’s too short to even tell what color it is.

When Oscar left the military, he became an ambassador. He did two tours in Iraq. His specialty is arms negotiation. Most of his job is telling foreign ministers how big and beautiful American bombs are and just how happy he’d be to use them. That’s what he’s here to do—bully Moscow into submission.

The thought makes her shudder. Before Juliette became an ambassador, she worked for the National Parks Service. She loves wind, solar, black bears, and red wolves. She goes over her

talking points in her mind. America is transitioning to clean energy. We are no longer dependent on Russian oil. We won’t pay so much for it. You ought tojoinusbeforeit’stoolate for us all.

Victor Petrov, Russian minister, stood before them, black coat flapping in the wind and rain like the gums of an enormous, snarling black dog. That made Victor the teeth, bared as he is.

“Welcome, Americans.” “Thanks for having us. Oscar Moore.” Oscar says. He reaches for Petrov’s hand and shakes it, hard, like he’s trying to wrench the arm from the socket. Petrov is one of those mean, hungry-looking Russian politicians with nicotine stains on his fingers and a certain lovelessness behind the eyes.

“And you?”

Oscar is already trying to pick a fight. That’s how all wars start: men like Oscar

trying to rip off the arms of men like Victor Petrov.

She’ll win her own way. Charm. Peace. Light and love. She’ll show them.

“Juliette Rodgers. Jewel of the Inland Empire.”

“I thought you were American. You are American embassy, no?”

Russians couldn’t detect even an ounce of vulnerability from them. They especially couldn’t detect any internal division.

But Juliette and Oscar had never agreed on anything in their careers. He was a pig-headed man who loved beer and guns, and she was the woman who was going to save the world.

She’ll win her own way. Charm. Peace. Light and love. She’ll show them.

“I am. Inland Empire is California. Near San Bernardino?”

Not a hint of recognition in Petrov’s eyes.

“Never mind. I’m the other American ambassador, yeah. Can’t spell USA without us, right, Oscar?”

“Right,” he says, flatly.

They’d promised on the flight that they’d be a united front. If they were going to find and chip away at any vulnerability the Russians had, then the

Petrov leads them through the damp, cobbled streets to the American Embassy in Russia, the location chosen for the meeting. The building was once astonishingly white, gold, and shiny, a NeoByzantine daydream meant to make Americans feel safe this deep behind enemy lines.

Now, in the rain, the building looks grimy and grim. Its airy, arched windows are carved into the steady, blocky façade.

• • •

“Is it just us, then?” Oscar asks. “No one else from your side is joining us?”

“Just me. No one else in Ministry finds this important,” Petrov says. She chuckles, though her heart squeezes, her teeth clench, and her cheeks flush. It pisses her off. What

could be more important than the collective future of the entire planet and/or world peace? Russians. Men. Politicians. She’s learned in many years of bureaucracy to try her best to smile through it. Be charming. Soldier on.

“So-vee-it, then!” She tries to joke.

“What?”

“Well, So-Vee-It. It sounds like ‘so be it,’ as in ‘it is what it is,’ but also ‘Soviet,’ like the Soviet Union. Get it?”

“Soviet Union dissolved in 1980s. You know this,” Petrov says.

“Yeah, I do. I was trying to be funny.”

“Hm.”

“Alright,” Oscar says. “Let’s stop beating around the bush. POTUS says Russia needs to slow its nuclear developments—”

“And increase its clean energy developments!” Juliette cuts in.

“... Right… by the end of the next fiscal year, otherwise, the US will strangle your economy with sanctions. And while we’re at it, we may strangle a couple of your leaders.”

“Your POTUS is tyrant. Russian production will stay as is. If you do not want war, why don’t you want us

to have weapons, hm?”

Oscar’s hand tightens. His fist isn’t even hidden under the table. Juliette could roll her eyes. Here wego,Mr.Americana.

“How dare you? I joined the US military to take down tyrants. When I was in Iraq, I saw men blown to bits, fighting for their right to be free.”

Victor laughs in his face and Juliette sees Oscar’s cheeks go a bloody red. He looks like a child on the verge of a screaming fit as he starts to snarl, “Comm—”

“Let’s talk about clean energy! Listen, then we need to band together as a world to prevent climate change. Otherwise—”

“Mutually assured destruction?”

“Well, no. C’mon. It’s not the Cold War, it’s global warming. But, if we go down, we go down together. And the US and Russia are the biggest

Oscar stamps on her foot under the table. She bites her tongue to prevent sound escaping as his old military boots smash her sensible black heels.

“The US is the biggest power, and Russia is up there, I guess,” Oscar corrects.

“Whatever. What we mean to propose is a Green New Deal with some nice red accents. Vhat do you think of that?”

“Do you make fun of my accent?”

“No! I mean, maybe a little. Just to cut the tension, a littl—”

“Okay. I need to talk to you. C’mon,” Oscar says, grabbing her harshly and dragging her out of the room.

“You need to pull yourself together. This is not playtime. Enough with the laughing, and the jokes. You’re getting us nowhere.”

“Oh, like you’re getting anywhere? You two are in some weird dickmeasuring competition about nuclear arms! That’s getting us nowhere,” Juliette snaps.

“You need to strong-arm guys like this, okay? He’s Russian. He doesn’t get our morals. Or our sense of humor,” Oscar grumbles.

“Our? You’re meaning to tell me you get my morals? Or my humor?”

Oscar is silent as he thinks, brow furrowed, staring out the ornate window at the sky, watching for airplanes. “No. I don’t get it either.”

They re-enter the room, where Victor has been waiting. He rises to meet them.

“Here, I call you cab to hotel.”

“We’re not staying in the embassy? Why?” Oscar demands.

“There’s been a bomb threat,” Victor answers flippantly. And Juliette knows he’s not joking.

It’s late but not quiet at the Hotel Indigo. Outside, traffic rushes and thrums. As night falls, the sky turns from rain to snow to falling sheets of grayish ice, dripping like the drool of an enormous, hungry beast. Out in global powers.”

the street, Juliette thinks she hears a baby crying. Or maybe a stray cat, wailing out into the night. The covers on the beds of the Hotel Indigo are white and stiff, cleaned past the point of comfort. She longs for home; she longs for victory. All this way, and for what? To stand drenched in sorrow and drizzling rain. Oscar smokes Marlboro Reds in all weather. She looks for him in the alcove and sees nothing. She drops to the bed, still in her work clothes and heels, and tries to close her eyes.

Something taps on her door. “What?!” she calls, no idea what she’s expecting. Maybe a cleaning lady? In the dead of night? Things are different over here, but not that different, right? Maybe an assassin. Wouldn’t that be nice?

pearl-clutching, Christian fear of sex and perversion.

“...Sure.”

The opens the door, undoing twist locks and deadbolts until she’s standing face to face with Victor Petrov, still clad in that black coat. Snow melts into the wool, weighing it down, pulling him into the depths of the Earth, oil puddle that he is.

“So, what did you want to talk about? Trying to do some under the table, backrooms deal?” Juliette asks.

She longs for home; she longs for victory.

“We got nowhere today,” she hears a voice from the other side of the door, slick and heavily accented.

“Minister Petrov?”

“Ambassador. May I come in?”

Juliette is reminded that Bram Stoker’s Dracula was based in part on Vlad the Impaler. A menacing figure held at bay by nothing but courage and pure hearts. He was based, too, on a

“You’re stubborn. Hateful. Everything you say we are,” Petrov replies.

“That’s not true. But your worldview is contradictory to mine. In-com-pat-i-ble,” Juliette says.

“Do you think that’s true?” He asks.

“I want peace.”

“So do I.”

“You build bombs.”

“Bombs are good for peace, if you build them big enough. What good is

or a declaration of war. She sits as well.

“I want to try another tactic,” Victor says. He smells like oil and cologne, like a war about to start. “You like pretty things,” he says. “All Americans do. You have your Cadillacs.”

“What good is the planet, except a place to fight?”

the planet, except a place to fight?”

“You’re sick,” she says, moving to slam the door in his face.

“Wait,” he says, jamming his hand in the doorway. She slams it anyway, hard against his hand but it doesn’t close and he doesn’t flinch. “We… I cannot afford more sanctions. People are hungry. Restless. Hungry people bite. May I come in?”

“So get bit,” she snarls, but steps aside anyway, letting him stand closer to her than is comfortable. It’s a tiny place with no seat but the bed, which he does, in fact, sit on. She cannot tell if it’s a gesture of surrender,

“I drive a Kia.”

“You like pretty things more than all rest, though. Do you like pretty little birds? Rivers? Field of wildflower, yes? That’s why you came all the way here. So you say. Do you like ballet?”

“What?”

“That’s what we have that’s the most beautiful in all the world. Ballerinas.”

“You’re not a ballerina.”

“But you still think I am pretty.”

She freezes. Is he? He’s got the dead eyes of a shark. He’s got soft hair. He’s got blood on his hands. He’s got a slender body; maybe in another life he was a Russian ballerina. He works for a fascist regime. But then again… doesn’t she? Hasn’t she said that, in her most angry moments? In her most frightened ones? He’s a complex, unsolvable, high-stakes problem. And to someone like her, that makes him irresistible. All she wants

to do is stick her hands where they don’t belong.

“I could get you elected in America, you know,” Victor murmurs.

She readjusts, reaches behind her, fumbles blindly as best she can with her cellphone and tucks it under the pillow.

“I don’t want that,” Juliette says. “I’m an honest politician.”

“No such thing.”

to just kick him away. Jam her heel into his crotch. Tell him to go fuck himself and fall out of a window. But…

Well, she did say she was an honest politician.

“Yes.”

“There is. There’s me. And the American people value that about me.”

“Are you trying to be funny again?”

“No.”

“Good. Is not funny. America is ridiculous and foolish country. In Russia, our politicians don’t lie about being liars.”

“Jules! I was wrong!” The door slams open. On the other side is Oscar in his undershirt and boxers, holding his phone cord like a lasso in a stupid cowboy film. “The outlets are different here—I should’ve gotten one of those stupid adapters at the airport—can I borrow one of yours?”

“So you admit it? But… you work for the government.”

“Please. Everyone in Russian government knows Russia is terrible. And everyone in Russia knows Russian government is terrible.”

“Hm.”

“Madam Ambassador, do you want to have sex with me?”

He crawls onto the bed, head tipped to the side, bowing towards the joint of her neck and shoulder. She feels the cold war getting hotter, and hotter. She ought

And here’s the Russian minister, sprawled in her lap. Here’s her, with her shirt half-unbuttoned.

“You didn’t lock the door behindyou!?”

“They are supposed to lock automatically. Hm. I guess that was not true,” Victor says.

“What the hell is this?” Oscar demands, as soon as he and Juliette lock eyes.

“Negotiation?” she

“You and your stupid, hippie bullshit. This is treason, probably. I’m not actually sure. But probably.”

“I thought you were not fan of international law.”

“Shut up, commie.”

“You shut up, Oscar. You’re gonna start a nuclear war and I don’t even have my bra on. Jesus. Now who’s the overly emotional sex. Victor, get off of me.”

He does, rolling off of her and onto his back. She moves to redress, but Oscar tugs her to the side and holds his hand up to his mouth to whisper in her ear, as though his palm could do more than billions of dollars to the NSA, in terms of preventing Russian spying.

“This is about war. Power. It’s an arms deal. We’re talking about bombs and missiles. Alright? Not whatever the fuck this is,” Oscar whispers.

“Oh, you want to talk

about power? Missiles?” Victor says as he leans back and lets his legs spread before the American embassy. “Mine’s bigger.”

In a room, a big red button waits to be pushed. It glows and pulses into the night. Almost there, almost there, almost there.

But not quite.

“Jesus, did they teach that move at Yale Law?”

Not yet.

“I thought American military man would have more stamina.”

Not tonight.

“Right there, right there, right there!”

In the Hotel Indigo, Oscar collapses onto his elbows, face down into industrial pillows.

“Are these from the damn USSR?” Oscar asks.

“No,” Victor answers from where he lays, staring at the ceiling and panting. “Why do you ask?”

“‘S scratchy.”

“Poor little American soldier boy. Do you want your cotton from your Egypt? Your cigars from your Cuba?” Victor retorts. suggests.

“Don’t bring up Cuba, you commie piece of shit.”

Juliette says nothing, her mind reeling and tumbling like a damn Russian acrobat, legs akimbo and spread eagle (did he really?). She reaches for her blouse, blue as the American sky where it’s been tossed carelessly to the floor (did she really?).

“Oscar. Whiskey,” Victor demands.

“Nooo,” Oscar whines.

“Oscar, whiskey,” Victor repeats.

“Christ, you got an echo, now, Victor?”

Victor kicks him under the blanket as best he can, given their… positions.

Oscar sighs, “We don’t have ice. I only drink it on the rocks.”

“Get some,” Juliette hisses. This could be a chance for her, she’s realizing. Hasn’t this been what America’s been looking for all this time? A moment where Russia is vulnerable?

or vending machine, some shrapnel of American comfort. Or maybe he’ll go outside, plunge his hands in the dirty Russian gutters filled with snow and rain and sleet.

Not that it matters, Juliete is learning. It all tastes the same in the dark. Victor leans over and around her, reaching for two boxes on the nightstand—cigarettes and matches. Did they really?

“You’re gonna start a nuclear war and I don’t even have my bra on.”

He lights one and holds it out to Juliette.

“I don’t smoke.”

But there’s Oscar. With his military haircut, his grating voice, and his bombs. He’ll put them right back on the warpath. Hadn’t her college friends always said, Make love not—

“Fine,” he spits on the ground and leaves, presumably to find an icebox

He eyes her, and she resists the urge to dress faster or pull the blankets around herself. Here she is. The whole truth and nothing but the truth. America, in the flesh.

She takes a cigarette.

“I don’t smoke,” she

repeats, even as Victor lights it, and she breathes in deep.

“No. I suppose you don’t,” he says, without a hint of humor in his voice.

“Not everything is what it first seems to be, is it?”

Juliette shifts and pulls out the phone she stashed under the pillow when this all began. Sure enough, it’d worked. She’s been recording this all. A perverse shudder runs through her. Hotel Indigo, her Watergate, her Berlin Wall, her great service to her country.

“You’re going to agree to Oscar’s arms deal, and my clean energy commitment,” she says. Victor just laughs at her.

“I won’t.”

“You will.You’lldowhat I want. Otherwise, I release this.”

She holds up the phone, showing him the recording. The audio levels are jagged and high, like a rapidly beating heart.

“You’re blackmailing?

Not very honest politician thing to do.”

“Well, maybe you were right.”

“And what if I still don’t do what you want? Hm? What will you do with me then?”

“You had sex with me. With us,” Juliette reminds.

“You had sex with me. And with him.”

He was right. She didn’t like that. Didn’t like what she’d had to do, how she’d had to bend and hold her breath and close her eyes. But she had. That’s what it took.

“More importantly,” she continues. “You criticized your regime. You admitted to wanting to interfere in American elections.”

“Mutually assured destruction. Just like good old days,” he muses, taking a deep drag and lapsing into stony silence once more.

Juliette licks her lips. They taste like ash and war. She takes a steadying breath, readying herself to say her piece.

“I believe that love can save the world, I really do.”

“Hah. Now that’s good joke.”

To trace the lines of my spiral heart and follow the shoreline on my hallowed chest feel the polished stone, that precious little pearlescent piece deep inside me, that’s been so kept away.

I want someone to hold my little conch shell body, and touch its ridges. I want someone to see me curiously, and cradle my spindly thorns between those fingertips and press me close to their ear.

They’ll mark this moon sliver of time and say, This is the first time I’m really listening to your heartbeat. They’ll hear ocean tides pound and splatter those lonely points. All sacred places without name finding their way into my DNA. No return address, and no escape. I must wait out this terrible storm. Slam and crash into walls and doors, pour all of myself out those bay windows, and at last land in the little sand dollar bank.

All rounded pieces and open vessels. All sunburnt seaweed tresses.

My heart was starting this new and incredible act— of cracking wide open in the face of frenemy/ or foe/ or forever.

But there is no spackle/ or paste/ or faith to seal this crack back shut. I am unzipped by age. There’s no cure for this ailment. What we call seasickness is what I call being in my own body. The constant churning of storm, or of sobbing sea.

But that’s how pearls are made, right? As a defense against villains. Nothing to enter my husk or damage my fragile little body.

I am tender meat. I am tangy pearls under tongue. I am sacred shell.

I am/ I am/ I am.

I think I confuse getting better with moving on. Like old wounds with fingers stuck in, The bleeding is over but the flesh is open, Bow-strings of muscle whistling in cold air. Getting better can’t beat getting to bed, Where I blood-stain my sheets and don’t wash them And where I look at the world through a tiny black window And congratulate myself for surviving a minute, then another.

I have to plug up so I don’t spill over, Pray to baths of foaming, dirty water Like Narcissus, Where I wash and don’t feel clean. Sometimes, I skim fingers over top, Stare at mud clumping the drain, And think of solutions less clear, More permanent.

I can’t stop stopgapping or it’s over. There’s no coming back from certainty. I could push my fingers deeper into wounds, Part muscle like velvet, Find a switch, turn off pumps, Plumbing hidden under thin skin, And go somewhere un-temporary, Crystal springs of heaven.

I walk the earth with fingers in dams That won’t heal if they don’t bleed.

Liberated orange and black bed socks

girls on the run with a shelf of empty

sketchbooks, labels stuck on olive

jars, cherry stems tied taut, Hester Prynne,

Audrey Horne, you are my queen of hearts

in the world where I am man and devil and those are both red, scorching things about me

autofiction scrawled anywhere but a bar bathroom stall

if I’m being so bossy and honest I’d say I wish I wasn’t free

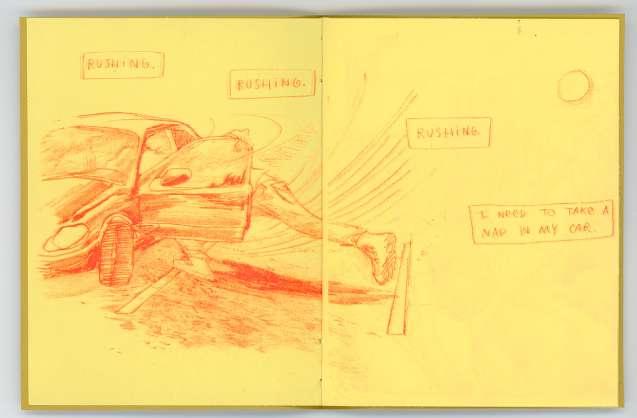

Hey carnales, two thousand and twenty-four is pretty bitchin’ so far, eh?

Everyone’s talking about how far we have advanced into the twentyfirst century. It's just plain gobstopping glorious to think about where we came from to get here. All that shiny shit, that marvelous mierda, reminds me of a fable I heard one day at Ghetto Smith’s while wandering through the dog food aisle.

It's a story about the New Mexican astronauts; los recuerdan? They came from the South with their sister the scientist in an attempt to reconcile el Norte with la neta, if such a thing is possible.

I imagine there is all sorts of stuff on the interwebz about this. Maybe you ought to Google it when you are done here: This story is about the time those two, nursed on atomic infusions and the dull knife of continuously magical circumstance, were gifted with petroleum-powered caballos mecánicos.

for exploration that was dangerous and therefore had to be studied, modeled, processed, and then undertaken with the utmost gravity.

Additionally, there would be no supervision or support on actual missions, just the endless sage, wrecked cars, spiders, and occasional cows encountered on trails that had been carved out by the agents of men who had been making movies about an imaginary version of Albuquerque. They wanted a way to conveniently strand their hero in the Sandia Mountains, near the end of the fifth reel, like he was el vaquero más solitario del mundo or something like that.

La historia suena así…

The dirt bikes were a good idea because they introduced a format

One of the motorcycles was painted green; the other was red. That configuration had nothing to do with the mythos of the popular culture in those parts regarding

two fruitful colors. In this case, let us say that the patterns and spectral traces differentiating one vehicle from the other symbolized springtime and blood, respectively.

from the corner of one's eye and waiting to be fully observed to be made real.

Mud leapt up into the air as the spacemen approached.

The devices were put to use; a practice concerned with the depiction of new experience was initiated, and lonesome guitar songs played over the entire narrative as it unwound—a plain reflection of the awesome and empty mesa that stretched outward and to the east from the main observation laboratory.

The two New Mexican astronauts then prepared a mixture of gasoline and oil, imagining the far shore as just over the looming mountains, a bright and exotic locale similar to the levant seen vaguely

And so with their sparkly protective headgear properly applied—one had big blue stars on it, like the Cowboys in Dallas once wore in their fabled infancy—the two New Mexican astronauts zoomed through several very compact iterations of the eleventh dimension which were craftily disguised as this or that neighbor's backyard, right out into the middle of the vasty plain.

En ese desierto, algunos de los cactus estaban brotando flores colorido, y birds made from stones. Mud leapt up into the air as the spacemen approached. There was a shift in the sand where a serpent had slithered by, and a beverage storage unit abandoned long ago by another explorer whose size the astronauts determined to be in excess of three meters, and who therefore probably came from one of the moons of Jupiter.

The only problem was that the whole scene lacked nuance. The two New Mexican astronauts fiddled

with the idea of strapping a portable radio-wave receiver to one of the dirtbikes but decided it wouldn't be the same because meaningful tuneage would just get lost out there among the eroding arroyos, saben?

When they arrived at the foothills preceding the inside-of-awatermelon–colored mountain, they paused and noted its grandeur. One of them swore he could see other humans dancing on the very top, on the southernmost peak. But they were so small, they might have just been some sort of vulgar insect life, one of the astronauts proclaimed. Qué lástima, quoth the other. Fearful of such potentially barbaric entities, they retreated.

On the journey back, one of our heroic travelers, the one with the name like a wolf (the other was called after the highest of clouds), ran over a small rodent. Basta!, each cried out to the other as the little rat’s blood drained away into la tierra.

Saddened by death and then made wondrously indifferent by life, they hauled ass back to their floating chante and parked los motocicletas in a dark room filled with ghosts. The

two New Mexican astronauts spent the intervening days listening to A Night at the Opera and Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, smoking Salem brand cigarettes stolen from the captain's quarters.

At night they would take out their microscopes and consult encyclopedias while the wind churned and rattled as if telegraphed from a much loftier world. Finally, their research completed, the New Mexican astronauts settled into their labyrinthine headquarters and took a nap. Shortly after the solstice, the dirt bikes became small birds con plumaje inexplicable that flew off towards the sea, singing “The Ballad of Danny Bailey” and weeping loudly as they went aloft.

For Associate Professor AlbinoCarrillo(1964-2022).

architectureproposal

I’ve never met a playwright but I’d like you to show me your script

Do you hear my voice rattling like the Hermetic Devil’s?

Last night I knew what that meant and wouldn’t rise to record it

I will need you to trust me I will need you to manage the stage

I will need you to bruise my arms and laugh when I do not drag properly the table

at which Goody Proctor breaks salty bread and drinks bitter wine

I’m just not quite sure how to become someone else when I step into the light

I thought I would live in that RV forever, pulling red curtains around our bed for privacy, eating off quail placemats your mother gave us, searching for a Mexican grocery store boarded up by border patrol years before, buying stale tortillas at 7–Eleven with coins I found in the place you keep your camo hats, watching videos you sent of your lawn work, printing your pay stubs on yellow paper, taking care of your thumb-sized brother who never stopped crying, even after I gave him thimblesful of milk and canola oil. I can’t be a virgin for you forever. I can’t not have you, even on the bed that all can see. I can’t mother your brothers or your sorrowful blue eyes or your smooth, seeking voice. I am too awake for that, groping around for you or a phone with a set alarm. So long ago, I learned to lull myself to sleep with want. Now it makes me hollow, the way a ringtone sounds after many mornings alone.

Poetry

This is how I will remember you Standing a ways off Taking the tide in Timelapse

Sometimes I picture your life As years condensed into minutes Images flashing across a screen Childhood in film grain, a changing world, Uncertainty, loneliness, love

I watch it bleed into mine And I want you to know the Timelapse slows Each Sunday morning In your car

When you let me sit up front And we listened To In Rainbows

And you were drumming on the wheel And I was mumbling along

If I compared life to A well-skipped stone Would you understand What each moment of contact Was meant to represent?

Equate each arch to a year and see them grow smaller and smaller

Until the stone sinks Or lands across

All this to say

I’m afraid

That time is collapsing

That life is leaving Where do I put that fear? How can I make it smaller?

Show me the video at least

Let’s watch the water race through time And find out

If making it smaller

Has taken anything from it

eptember is almost over. The weather has cooled enough for hot air balloons to launch in the mornings. Migration season is near.

The Rio Grande Valley is a major route for migratory birds, and in late September, they begin to arrive. At night, they roost in the low river on sandbanks. At dawn, they rise from the river’s bosque to search out fields in which to forage. Sandhill cranes have overwintered up and down the Middle Rio Grande Valley for generations. They come from the north, from parts of Canada, Alaska, and even Siberia. In the past, they fed in the seasonal wetlands along the river, but more recently, the birds rely on agricultural fields and restored wetlands. These ancient birds follow ancestral migratory paths year after year, but I only noticed them a few years ago. Until then, I had lived my life without knowing about these remarkable birds.

I was pregnant with my third baby when we moved to this rural area. I stayed at home with my children for ten years before returning to the workforce. Being a mother of three young children kept me close to

the ground. I often sat on the floor with my kids; at first, when they would lie on a playmat and observe the small world of our home around them, then as they learned to sit up by themselves, and then crawl. I sat on the floor and read to them and played with them, showing them how to stack blocks, how to roll a ball, how to hold a cloth book and turn its pages. Even when standing, my eyes were fixed downward, watching my children. We went for walks and looked at the ground, searching for bugs, or flowers, or an interesting rock. I was with my three children nearly every hour of nearly every day while my husband worked and went to school. I treasure the time I had with them when they were small. But at times, there was something there with

me which I did not yet recognize as loneliness. • • •

One particularly difficult morning, everyone was out of sorts. The oldest would not let me brush her hair and batted my hand away every time I tried; the second found out that meat came from animals and was devastated; and the third wanted to wear

enough to enjoy our visit and return home with our canvas bag full of books. One was a picture book of the Japanese folktale “The Crane Wife.” It is a story of kindness, love, and greed. It begins and ends with poverty and loneliness. Oncetherewasapoorweaverwho lived alone…

These seem like small things. I assure you they were not.

the red shirt, not the green one, but the red one was in the laundry. These seem like small things. I assure you they were not. We needed a change of scenery. I scrounged around the house looking for change to put some gas in the perpetually empty tank. We managed to make it to the library and distract ourselves

It is a magical thing to watch someone weave, especially if they are using one of those large looms, the ones the size of a dining table. The thread is carefully strung to create the warp, and once that’s done, the weaving begins. With steady rhythmic movements, the weaver sends the shuttle back and forth between the warp threads while alternating the thread pattern through which the weft thread travels. It is a slow and ponderous activity for a beginner, but captivating when done by an expert.

Our drive to the library took us into town and past quite a bit of farmland. As someone who grew up in suburbia, the farms held a special kind of fascination for me. As I

passed the farms again and again, each season’s pattern emerged, and I recognized a small measure of the rhythm of farm life (albeit from the driver’s seat of my car). In the spring, fields were plowed and sown, irrigated with river water from the acequias, the irrigation ditches; seeds sprouted, covering the red-brown earth in a green haze; crops grew, either alfalfa or corn. By summer, the corn was tall and shining green, and the alfalfa was in bloom, a hovering cloud of bees and small yellow butterflies visible just above the tiny purple flowers. The end of summer brought harvest time, and the fields were dotted with the pale gold of dry corn stalks and green-gold bales of hay. In the winter, the fields rested and became a feeding place for wintering birds. In the spring, I pointed out the new lambs and calves to my kids as we drove past. Anytime we went anywhere, birds foraged in the fields. Different birds at different times of the year. I pointed them out to the kids, and naturally, the kids asked if I knew their names. I did not, and so we went to the library and searched

for them. We discovered that, in the summer, the cattle egrets—bright white birds with pale yellow shoulders—and the white faced ibis with their dark iridescent feathers stalked the irrigated fields. Soaring above them on thermals were turkey vultures, attentive to the dead. We often saw kestrels, diminutive raptors the size of an adult’s hand; shining black ravens with black beaks; and tiny goldfinches flitting among the tall grasses edging the fields. But best of all, in the autumn, huge flocks of migrating birds arrived. Snow geese and Ross’ geese, white with black-tipped wings; many species of ducks; starlings flying in the mystery of murmuration; and sandhill cranes. Since then, the cranes catch my eye, again and again. I often pull over on the side of the road to

watch them.

I can clearly see the convergence of factors that drew my attention skyward and caused me to look up and around. First, there was the picture book, with its lovely watercolor illustrations. The story itself was new to me, though the archetypes felt familiar. Then, I attended a class where I learned to weave. Different methods of weaving on different types of looms, from simple and primitive to modern and highly technical. Though none of the methods I learned could really be considered simple. To me, it seemed like magic. And finally, I, like a child, looked and saw that the world was bigger than the small sphere within which I moved, bigger than my little family in our little house. It is amazing what you can see when you pay attention.

Once there was a poor weaver wholivedalone.Onesnowyday, hefoundaninjuredcrane,whose wing was shot through with an arrow.Hetookthebirdhomeand shared his meager meals with thebirdandcaredforittenderly. When the bird recovered and was strong enough, it left the poor weaver and flew into the wintersky.

Crane hunting is legal in New Mexico. It’s supposed to be a sign of a healthy population, when there are enough birds to hunt. A friend refers to the cranes as “the ribeye of the sky,” and I can’t help but laugh and shudder. Hunters submit applications to a permit lottery, and only a few are granted each season. Limits are placed on how many birds may be harvested.

“The Crane Wife” is a story that could have developed in many places—anywhere with a migrating bird population and a tradition of weaving and storytelling. This story could happen anywhere. It could happen here.

I mark each year by the arrival of the cranes. The heat breaks and September breathes a cool sigh of

relief. The sunflowers bloom along the side of the road through late summer, just after the prickly pear fruits swell on their cactus pads. The sunflowers fade, and the leaves of the cottonwoods turn vibrant yellow, then shimmer gold. The hay and corn are harvested. October approaches, and in the sky, you can see the cranes. At first, they look like smoke from folks burning their weeds. But the soft gray smudges grow larger, and more solid, and move faster than smoke. They bring the cold with them. They are winter’s birds. Just look at them. They are the color of winter clouds and fallow fields.

Once, I saw a great flock slowly descending onto a field. There were cranes on the ground and in the air and in between. It was as if I were watching a slowmoving funnel cloud stretching from ground to sky, higher than any house or tree, and cranes were circling their way down. Around and around they soared, and the ones close to the ground had their legs extended out in front of them. Cranes, when they land, remind me of parachuters,

or an airplane engaging its landing gear. If I had a magic spell to call the cranes to me, is this how they would come? I imagine standing at the center of all that movement, surrounded by a swirling cloud of birds and feathers and rattling cries.

Did you know that sandhill cranes are monogamous and that they mate for life? They perform complex courtship rituals

If I had a magic spell to call the cranes to me, is this how they would come?

that include a series of movements that resemble dancing, offering gifts to one another, and calling and responding to each other as if in song. Their long slender throats conceal a looping windpipe that creates

their distinctive rattling call. They travel in family groups and recognize each other’s calls and use them to locate one another among hundreds of birds.

A few years ago, one early winter morning, I drove to work while it was still dark. There were

as tall as I am) and taking it home. It was probably ill or injured. Why else would it be standing there? I am no wildlife expert. I drove on. I was already late for work.

Time has passed, and not always with ease and kindness.

few lights on the two-lane highway that comprised part of my drive. As the road widened out to include a center turning lane, I saw a crane. It stood in the middle of the road, unmoving and unbothered by the trucks and cars driving past. My headlights shone on it and then I was past it, wondering if I had really seen it. For just a moment I thought about stopping. I imagined trying to coax it into my car (the bird was

I was preoccupied for the rest of my day. I imagined taking the bird home, calling work, and explaining that I couldn’t make it in today because I had a crane to nurse back to health. Or explaining to my family that we need to make room in our small house for this

wild creature. Besides, it might be magical. I don’t need a crane wife, but if it turned out to be a bird that was also a woman, maybe she could be my crane friend. I would not insist that she weave magical cloth, but if she wanted to weave, I would get her a loom. And if she chose to shut herself away for three days and nights to weave a wondrous cloth using thread from her feathers, I would not disturb her. I would not drive her away with demands that took her gift, freely given, and constricted it until her very life was drawn from her like thread through a needle. I would tell her she could

come and go as she liked. In the spring, when the air warmed and the wind began to blow, if she wanted to return north with her family, I would wish her a safe journey and look for her return in the fall.

Something about seeing these cranes—these large birds—in flight makes me catch my breath. Every time. When I drive down a side road between farms, and cranes fly across my path, just above the car, or when I stand on a bridge over the Rio Grande and hundreds of cranes converge to roost in the riverbed, I catch my breath and my heart lifts. This is what I mean: Cranes fly above me, and I can see their gray-silver feathers with patches of clay-brown that they’ve applied to their bodies with their beaks as a camouflage; I can see their sharp beaks and sometimes their amber eyes; their long, scaly legs are tucked close to their bodies. Just below my throat, my breath catches; my shoulders fall back as my chin lifts and my head tilts towards the sky. I breathe and feel as if my heart is expanding. I experience a feeling of lightness as the birds diminish from my field of vision.

My children are older now, and all but one have left home, though they occasionally return. Our relationships have changed over the years. Time has passed, and not always with ease and kindness. But the rhythm of the seasons remains the same. It is mid-September now. In a week or two, the cranes will return, and my heart will lift as I look to the morning and evening skies.

And the mother was terribly kind. She met the father staged across a room, positioned on the dance floor of a frat house. He drove her to court-ordered community service appointments, looking straight into her eyes, telling her, “I love this life we have.” He talked about things like Gettysburg and bought little figurines of Abraham Lincoln to place on his bookcase. The two of them would dress up the presidential dolls like high-strung women, fashioning him in the daughter’s Barbie clothes, dresses, and heels. The mother looked at her children, four of them, and wondered if they liked her. She started collecting Dalí paintings and imagining her children in the bizarre landscapes. She insisted the children themselves looked like melting clocks and cursed the persistence of memory, knowing that land and animals and people wither away under her feet. And she slept with a collection of trinkets to not forget. The father and the mother sat alone in their room surrounded by rare, clay baby heads that they had strung along the walls and wondered if having children was always like this.

And instead of playing dress-up with her three daughters, the mother mentioned the small university in Pennsylvania where she spent her twenties worshiping rocks. And she thought she could maybe be famous if she held out just a little bit longer and ignored those small blows to her body. And the father took Lincoln in his arms, falling into a deep sleep, trying to preserve some sense of self. And he had nightmares about sitting on the battlefield with his daughter, fighting about history and what men are really like. And the doll looked into the mother’s eyes, high heels and all, telling her to look for something other than the truth. Time passes. And the memory of her children, four of them, melting like clocks, remains.

18x24inches

There are times I don’t worry if I’m man or woman, for what I am is held, my hand in your hand.

But if you broke apart my ribs a little bird would flutter and twitch, and keep itself entombed.

SACHI BARNABY

7.66x11.45in,digitalphotography

7.66x11.45in,digitalphotography

SACHI BARNABY

7.66x11.45in,digitalphotography

The emerald cockroach wasp, jewel wasp, or Ampulex compressa, are solitary insects. Endoparasitoids, entomophagous parasites, cannibals. The wasps sting cockroaches, turning them into zombies to be hollowed out by the wasp’s larvae. The first sting is aimed at the cockroach’s thoracic ganglion to induce a biochemically transient paralysis. The second sting is aimed at the head ganglia of the cockroach, disabling their escape reflex. Most pests are attacked by at least one type of specialized parasitoid. Parasitoids perform an important ecosystem service: In the process of generating their offspring, they suppress pest populations.1

COLTON CAMPBELL

In May 1940, the Experiment Station of the Hawaiian Sugar Planters’ Association sent Dr. R.E. Turner to the French Pacific colonial archipelago, New Caledonia, to retrieve A. compressa. Cockroaches threatened colonial economic interests in the Hawaiian Islands, and so, the invasive jewel wasp was introduced as a form of biocontrol from the far west of the Americas, and east of Europe.2

My brother called me again.

1 Christie Wilcox explains, “The quick jab takes only a few seconds, and venom compounds work fast, paralyzing the cockroach temporarily so the wasp can aim her next sting with more accuracy. With her long stinger, she targets her mind-altering venom into two areas of the ganglia, the insect equivalent of a brain.” Wilcox, Christie. “ZOMBIE NEUROSCIENCE.” Scientific American 315, no. 2 (2016): 70–73. https://www. jstor.org/stable/26047070.

For further reading, see Gal, R., Rosenberg, L.A. and Libersat, F. (2005), Parasitoid wasp uses a venom cocktail injected into the brain to manipulate the behavior and metabolism of its cockroach prey. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol., 60: 198-208. https://doi.org/10.1002/arch.20092

2 F.X. Williams, “Ampulex Compressa (Fabr.), A Cockroach-Hunting Wasp Introduced from New Caledonia Into Hawaii,” *Proceedings of the

I was on campus picking up a research poster I had presented earlier that day on the history of the Mexican folk song “La Cucaracha.” His voice shook, and he asked if I could give him a ride. I immediately agreed to pick him up. He had been undergoing electroconvulsive therapy treatments for bipolar disorder recently. On top of the electricity, over the past Hawaiian Entomological Society* 11 (1942). p. 221–233.

decade, his brain had been cooked well by antipsychotics that made him rigid in the body and slow in his head.3 He did not have his car because his license had been revoked. Earlier that week, he had been walking up and down the street with his shirt off, unable to explain his state. My parents had called the police.4

I wanted to be the one to pick him up. I did not want him to go back to the psych ward. I have done my time cocooned in those white walls. After I was released, I applied to grad

3 A similar method is used in pest control and is considered to be more humane than traditional extermination methods. “The winner of Australia’s 1991 Inventor of the Year award came up with an electrified version of the roach motel. After the cockroaches are lured in to stuff themselves with the bait, they ‘end up fried’.” Copeland, Marion. Cockroach. London: Reaktion Books, 2003. p. 57-58.

4 Medical actions like diagnosis and medication pathologize a mental state that is actually rational. This illness is a reaction to a “world without bonds.” “For its part, the primary function of the medical gesture was not the absolute eradication of illness or the suppression of death and the advent of immortality. The ill human was the human with no family, no love, no human relations, and no communion with a community. It was the person deprived of the possibility of an authentic encounter with other humans, others with whom there were a priori no shared bonds of descent or of origin. This world of people without bonds (or of people who aspire only to take their leave of others) is still with us, albeit in ever shifting configurations.” Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019. p. 6.

school. I had to prove that I was not insane, or that the word was arbitrary.5

That morning, I sang to conference goers as they passed, “La cucaracha, la cucaracha…”

I would let them finish the lyrics if they knew them.6 Most people sang the rest of the lyrics that they knew, the white lyrics.

called it a paradise, and talked about “Kaddie,” a mixture of k etamine and

Apparently, Maui Wowie was not strong enough for him.

Apparently, Maui Wowie was not strong enough for him.

“Nah, nah, nah, nah, nah, nah, nah…”

We would laugh when I sang the rest, the Villist version popularized during the Mexican Revolution.

“Ya no puede caminar Porque no tiene, porque le falta Marijuana que fumar.”

Around that time, Maverick took a one-way ticket to Hawaii. He

Some say that marijuana and other pre-Hispanic medicinal traditions elicit psychosis. Maybe they bring our attention to how little things make sense.7 Several Spanish speakers ruined my hook and sang the lyrics verbatim. I had the most

5 This venture proves itself with its own logic, “Language is the sovereign who, in a permanent state of exception, declares that there is nothing outside language and that language is always beyond itself. The particular structure of law has its foundation in this presuppositional structure of human language.” Agamben, Giorgio. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. United States: Stanford University Press, 1998. p.21.

6 I had hoped this interaction was not commodifiable.

7 Isaac Campos analyzed a study conducted by the Addiction Research Clinic in Calcutta between the years 1963 to 1968, finding the use of marijuana in psychotic individuals was falsely pathologized as cannabinoid psychosis. “Symptoms of irrational behavior, involubility, indifference to family and self, withdrawal, incessant craving to smoke marihuana,

At least nobody asked me directly if I was a white AngloSaxon protestant, a WASP.

descent. My research topic and how I look are thrown off by my last name Campbell. At least nobody asked me directly if I was a white Anglo-Saxon protestant, a WASP. But it was obvious that they did not care about this; they each scooped generous helpings of my flesh and spread it across their attention spans until I was hollowed and bleached stark white under the bright lights of the conference room.10

“La cucaracha, la cucaracha

rewarding conversations with them. By the end of the conference, the lyrics whistled through my calavera.8 My antennae were visible; maybe that was why people were drawn to my poster.9 One asked nervously if I was of Indigenous or Spanish coupled occasionally with violent responses to minimal or supposed provocations, were superimposed upon their previous psychotic symptomatology.” Campos, Isaac. Home Grown: Marijuana and the Origins of Mexico’s War on Drugs. United States: University of North Carolina Press, 2012. p. 33.

8 “Calavera” is the Spanish word for skull. Mexican representations of calaveras are decorative and often edible.

9 The New Jersey Pest Control Association holds a Cockroach Derby every four years, which is used as a predictor for which Democratic presidential candidate will receive the nomination. It is easy to see what candidates stand head and antennae over the rest, “In 1999 Al Gore outran Bill Bradley and in 1992 Bill Clinton ‘won by an antenna’.” Copeland, Cockroach, p. 64 from Amy Reiter, ‘Run, Roaches, Run,’ www.salon. com/people/col/reit/1999/08/19/reitthar.html.

10 The person of color is lactified phenotypically in research halls and in

Ya no puede caminar

Porque no tiene

Porque le falta

Flesh on their bones” 11

I told the conference goers, “Cockroaches are a part of the Blattidae family; Linnaeus chose this name because of the Latin prefix “blatta,” which can be translated to “he who shuns the light.” 12 I just wanted to go back to my darkened apartment and remember that I had flesh on my bones, but I thought of my brother running through the streets looking for a dark space to hide, and I knew that I needed to

find him, wherever he was, and lead him to the safety of the shadows.

After the conference, a Chicana playwright with a Wikipedia page visited our graduate class and asked us what we wanted to talk about.13 Everyone wanted to know more about her work. Still, I asked her how to survive without having

classrooms. Frantz Fanon elucidates this point using Rene Maran’s Jean Veneuse, a studious Antillean black man that has become a Frenchmen of Bordeaux. Due to his distance from his island origins, to the white Frenchmen Veneuse is ‘not black; you are [he is] very, very dark.’” and because he is a student, he is not primitive, “The ‘Negro’ is savage whereas the student is civilized.” In my case, I may be becoming another creature entirely—not human, not cockroach. Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. United Kingdom: Grove Press, 2007. p.51.

11 Lyrics added by the author.

12 “In 1758 a chap named Carolus Linnaeus decided to tidy the living world.” Weiss, Daniel Evan. The Roaches Have No King. United Kingdom: Serpent’s Tail, 2001. p. 6.

13 The award winning playwright Virginia Grise inspired me to write this story after I read her manifesto, Your Healing is Killing Me. Grise, Virginia. Your Healing is Killing Me. United States: Plays Inverse Press,

our identities flattened by academia.14 She gave a brittle laugh, and I guessed that the question came off as naive. She said she was

Still, I asked her how to survive without having our identities flattened by academia.

an artist and did not know how to help me. But she said that theater and research could be worldbuilding; her work in schools, prisons, and writers’ workshops 2017.

created something that could not be commodified, moving us “Towards A Politic of Collective Self-Defense Instead of Individualized SelfCare.”15 She told me that funding for ethnic studies was rising, to tell other cockroaches where the money was, and to give away my excess stipends when I could. I thought grimly about how pest control companies like Orkin primarily fund the study of cockroaches.16 How could I save my spirit for my family? In a protean scramble, am I to be impervious to the passage of time? Am I to feed

14 Essentially, how they were viewed depended on whether animals were edible or inedible, wild or tame, useful or useless… Modern anthropologists suggest that the explanation lies in their anomalous [not like us] status.” Keith Thomas, Man and the Natural World: A History of Modern Sensibility (New York, 1983). p. 57–8.

15 Grise, Your Healing is Killing Me, p.19

16 Ironically, the pest control company Orkin sponsors the O.Orkin Insect Zoo at the Smithsonian. It is the oldest operating insect zoo in the United States, open since 1976. Smithsonian Institution. “Insect Zoo, O. Orkin.” Smithsonian Institution. Accessed October 14, 2023. https:// www.si.edu/exhibitions/insect-zoo-o-orkin%3Aevent- exhib-132. This idea is far less ironic when we consider the western epistemological proximity of ethnic studies and entomology, “Whereas knowledge of

on the decay that comes with it? Universities extract more than can be repaid in currency and career. I wanted to tell her that it felt odd that a bug was under such bright lights and intellectual scrutiny. It was about the hours I spent being dissected and dried for preservation and further examination while my family and friends aged into creatures living in places that I found hard to recognize. I did not know how to say that, and I don’t think she knew how to either. I thought about Audre Lorde, “For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.”17

Could someone with six hands and

antennae find a way? Robin Wall Kimmerer writes, “If time is a turning circle, there is a place where history and prophecy converge— the footprints of First Man lie on the path behind us and on the path ahead.” 18