ABORIGINAL RIGHTS

A FORCE TO BE RECKONED WITH

LYALL MUNRO SNR WAS CONSIDERED A LEGEND OF THE LAND RIGHTS MOVEMENT. BUT, AS JAKE KENDALL REPORTS, HE SAW HIMSELF AS FUNDAMENTALLY A BLACK FELLA FIGHTING FOR HIS MOB.

A

19-year-old Lyall Munro was in a Moree pub sipping on an orange juice when an Aboriginal elder suddenly appeared at his side. He was told the old folks wanted a word. Munro — looking dapper in his station master’s uniform — followed the man down to the riverbank where he was confronted by a barrage of questions. “How come you have a job on the railway?” “How come you’ve got citizens’ rights?” “How come you can play football and get served in pubs with the white fellas? That an Indigenous Australian was afforded such civil liberties was extremely rare at the time. Munro was then given a list of instructions on what to do to help his mob attain the same freedoms that he enjoyed. “Uncle” Lyall Munro Snr — who passed away in May — lived by those instructions all his life. “I never read out of books or went to university,” Munro said in a 2014 interview with the NSW Aboriginal Land Council

30

(NSWALC), “I based all my involvement [in Aboriginal rights] around Australia and internationally on the advice of them old people.” Munro later recalled: “I left that riverbank a lot wiser.” It was the 1950s and, back then, the white lawmakers of the NSW northern town of Moree implemented a strict policy of segregation. “You couldn’t swim in the pool if you were unhygienic people — and that was aimed at the Aboriginals,” explained Munro. “You couldn’t walk on the footpath, get served in pubs and clubs or cafés. Or sit at the back in picture shows — you could sit down the front, but not up the back.” The pool Munro was referring to formed part of the Moree Baths. Which, in 1965, became the focal point for a landmark Indigenous civil rights protest. Led by Aboriginal activist Charles Perkins, a group of University of Sydney students had organised a bus

Inner Sydney Voice • Spring 2020 • www.innersydneyvoice.org.au

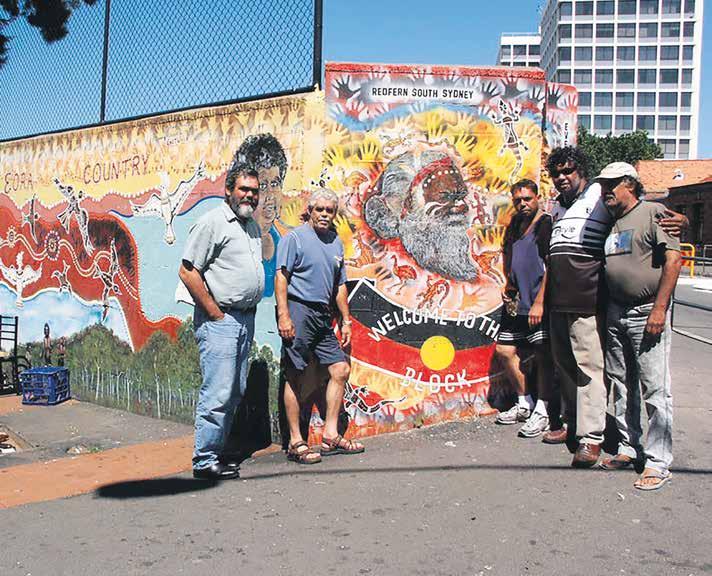

Lyall Munro (second from left), Les, Chock and a couple of other men at the Welcome to the Block and Eora Country murals. Photographer Patricia Baillie, courtesy City of Sydney Archives

tour of NSW towns to draw attention to Indigenous inequality. The Freedom Riders, as they called themselves, arrived in Moree on 19 February. Later that day, having collected a number of Aboriginal children from the local mission, Perkins attempted to gain entry into the Moree Baths. Munro and the Moree Aboriginal Advancement Committee had been fighting against the town’s racist by-laws long before the students arrived in town. “We were fighting for the cause but not in the manner in which the Freedom Riders done,” Munro told NITV in 2017, “so we stood and watched in the crowd. It was their day and it was an ugly scene, pretty rowdy, pretty wild — a lot of violence.” The protest captured the attention of the media and the racial injustice