4 minute read

Facing financial exclusion

FACING FINANCIAL EXCLUSION EVEN BEFORE THE PANDEMIC, CASH TRANSACTIONS IN AUSTRALIA WERE ON THE DECLINE. AS CHRISTOPHER KELLY REPORTS, POST-COVID, THERE ARE CONCERNS WE COULD BECOME A COMPLETELY CASHLESS SOCIETY.

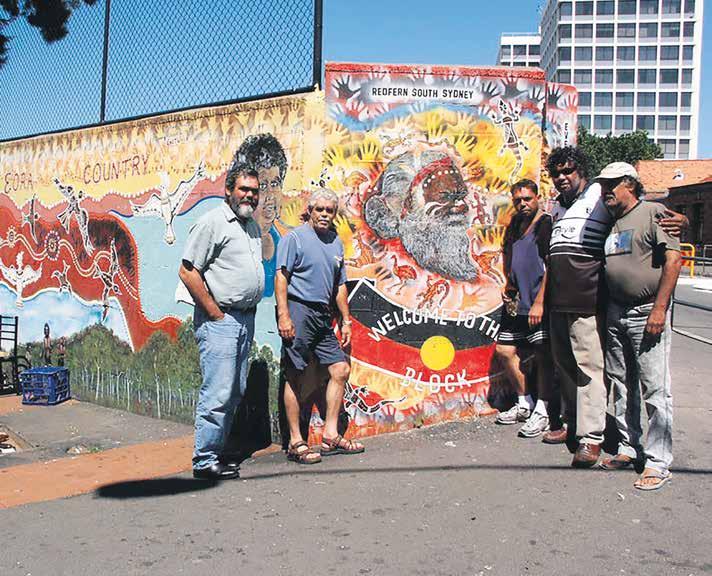

The thought hadn’t occurred to me before. It was only when the chap outside Woolies in Redfern asked for spare change that I realised that I rarely carried coins anymore. All I could offer the guy was a “Sorry, mate” as I passed him by. Ever since COVID hit, super markets and other businesses have encouraged us to forgo cash for tap ’n’ go. Even pre-pandemic, our use of physi cal currency was on the slide. A study commissioned by the Reserve Bank of Australia found that — since 2008 — ATM withdrawals have fallen almost 50 percent. And a Commonwealth Bank study showed a 35 percent drop in cash withdrawals over the past year.

Advertisement

Meanwhile, chief executive of the Royal Australian Mint, Ross MacDiar mid, has reported “virtually no sales for coins since the start of the year”. By now, 15 million coins would have been produced. But as stores were forced to shutter up and people shopped online, demand from banks dried up. Speaking to the Guardian Australia, MacDiar mid added: “During COVID, what has unquestionably occurred is that people have stopped using currency entirely or reduced it significantly.” If the trend continues, the Mint will consider stop ping producing coins altogether.

All this has fuelled speculation that COVID-19 will precipitate a shift towards a cash-free economy. One report — from Research and Markets — forecasts Australia could become cashless in as little as two years (the Commonwealth Bank gives it six). But a move toward a cash-free economy would prove devastating to the most vulnerable in society including the poor, the elderly, and the homeless.

According to the last Census in 2016, Australia’s homeless population stood at 116,000. The Census also recorded a 35 percent increase of people sleep ing rough in NSW, making the state the homeless capital of Australia. For these people, a cashless system would make a difficult life even harder. “This is a real issue,” said Justine Humphry, a lecturer in digital cultures at the University of Sydney, “and a potential point of financial and social exclusion for people who are homeless.”

It isn’t just Australia’s homeless affected by a lack of cash. It’s a world wide problem. And one that has led to some interesting solutions. In the UK, an Oxford University-backed initi ative supplies homeless people with barcodes to wear around their necks so that they’re able to accept mobile payments. Another UK project — called Greater Change — provides the home less with a QR code. Passers-by can then scan the code using their smart phone and make an online donation.

In New York City, council member Ritchie Torres successfully pushed a bill to ban cashless stores. “I started coming across coffee shops and cafes that were exclusively cashless and I thought, ‘But what if I was a New Yorker who has no access to a card?’” said Torres. “I thought about it more and realised that even if a policy seems neutral, in theory, it can be exclusion ary in practice.”

If Australia is to learn anything from how a cashless society would impact the vulnerable, it need only look at Sweden. Regarded as the most cashless society in the world, since the pandemic took hold, cash — at the behest of the banks — has all but disappeared in the Scandinavian nation. Indeed, 85 percent of transactions in Sweden are now electronic. And while there are many benefits of going digital — such as speed and convenience — Sweden has discovered that a cashless economy comes with societal costs.

Studies show Sweden’s hasty embrace of a cashless society has left marginal ised populations behind. Most notably, the homeless, immigrants, people with disabilities, and those living in rural regions. A UK report — called the Access to Cash Review — found that Sweden’s experience “outlines the dangers of sleepwalking into a cashless society” with millions of people poten tially ejected out of the economy.

If Australia were to adopt the Swed ish model, the poorest in society — due to their inability to afford devices capa ble of making electronic payments — would find themselves, not only locked

out of the economy, but excluded from accessing essential services. “I’ve found in my research,” said Humphry, “that essential services are increas ingly centred on and require access to smartphones — using mobile apps and text services for example.”

Should Australia go cashless, government needs to make sure that disadvantaged communities are protected and not precluded. Accord ing to the Access to Cash Review, “the consequences to society and individu als of not having a viable way of paying for goods and services are potentially severe”. But, “If we act now,” conclude the authors, “we can take steps to stop harm happening, and prepare for a world of lower cash, without societal and economic damage. If we take action now, we can shape a future which is both economically viable and in which no one gets left behind.”