WATERLOO REDEVELOPMENT

A LOSS OF PLACE

THE SOCIAL HOUSING RESIDENTS OF THE WATERLOO ESTATE HAVE BEEN PROMISED THAT THEY WILL BE REHOUSED ONCE IT IS REDEVELOPED. BUT, AS LAURA WYNNE AND DALLAS ROGERS DISCUSS, AN ABSENCE OF PHYSICAL RELOCATION DOES NOT EQUATE TO AN ABSENCE OF DISPLACEMENT.

W

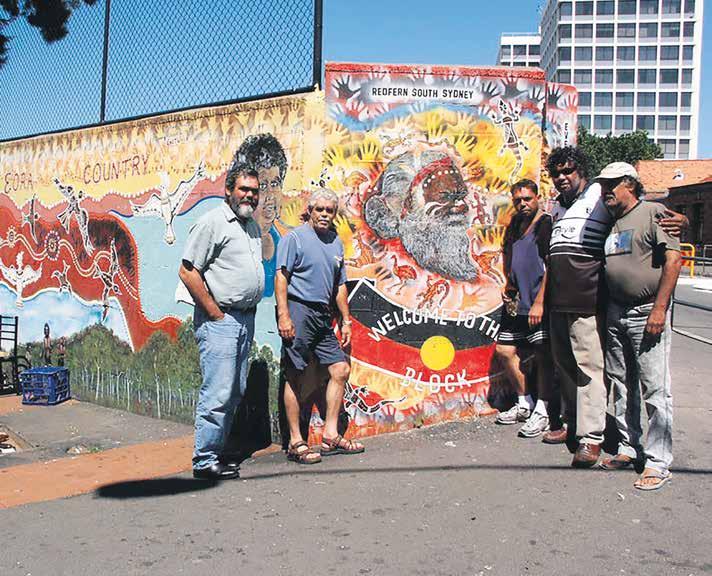

aterloo has a long history of displacement and upheaval. The area is home to the Aboriginal people of the Gadigal clan of the Eora Nation. The Gadi clan — whose land stretched from Burrawurra (Sydney Harbour’s South Head) west to Blackwattle Creek — maintained the land through burnings and the maintenance of paths throughout their country. After the European invasion and the displacement of the Gadigal people from their land, Boxley’s Clear — as Redfern was known in the early 1800s — continued to have importance as a meeting point for dispersed members of the Gadigal people and of their neighbouring clans. Eventually, however, European settlers became intolerant of their presence and the Gadigal were moved on to Waterloo, Alexandria, and beyond. Aboriginal connection with Waterloo did not cease with European settlement, and an Aboriginal community continues to live and work in the area. Waterloo and Redfern remain a centre of major cultural and political significance to the Aboriginal community. In the 1930s, governments were lobbied by town planning activists and social reformers to implement slum clearance measures. The overcrowded, poorly maintained, and inadequate housing of the inner city was thought to be a threat to both moral and sanitary hygiene, and thus was determined to require demolition and rebuilding. Many residents were displaced farther west to suburban Sydney, and many

22

were never given the opportunity to return to their former neighbourhood. The NSW government continued redeveloping land around Redfern-Waterloo until the 1970s, by which time a large public housing estate comprising both low- and high-rise apartment buildings had been constructed. It is these homes — 2,200 public housing dwellings — that are now subject to a redevelopment project. The project is framed by the government as an “exciting” opportunity to build a “dynamic new community”. The government labels the project a “revitalisation project”, and invokes an idea of the public interest to justify the redevelopment, arguing that value capture from the new private developments on site will allow a boost in affordable housing supply. Residents have been promised that they will not be forced to leave the estate in the long term and that all who wish to be will eventually be rehoused on site, although some may need to be temporarily relocated throughout the development process. Some residents of Waterloo reported that the prospect of moving within their neighbourhood — from their existing apartment or building to a new or different one — was felt by them to be a form of displacement. When told that tenants “will not be made homeless” by the redevelopment, Catriona, a long-term resident, responded: “Yes, but we don’t know where [home] is going to be.” For Catriona, a move within her neighbourhood

Inner Sydney Voice • Spring 2020 • www.innersydneyvoice.org.au