Reimagining McMinnville’s Library in

LA489/589: The Oregon Sequence (Fall 2024, Site Analysis)

A Site, a Studio, an Opportunity...

What follows in these pages is the result of a 10-week research intensive site inventory and analysis of McMinnville City Park by Landscape Architecture students at the University of Oregon’s School of Architecture and Environment (SAE).

The overarching goal of these efforts is to engage in the initial “need-finding” and envisioning process for a 15.4-acre study area comprising a historic library and large public park in the heart of McMinnville Oregon. In addition to proposing fundamental upgrades to its programming and facilities, students are encouraged to re-imagine the library’s relationship to the park, the park’s relationship to the library, and the site’s relationship to its wider urban context, attending to questions of public amenity, public safety, spatial justice, and ecological design.

Public libraries and public parks share the distinction of being among the last “free spaces” in in our increasingly privatized and consumption-dominated urban landscape— places where one can loiter, lounge and linger without opening one’s wallet. Adding to the weight of this dual distinction is the sense that both can (and must) serve as important incubators of democracy inviting casual social interaction across socioeconomic lines, knowledge sharing across boundaries of language, time and medium, and critical space for civic action and assembly. As observed by Mary McNear:

“Public

libraries are the heart and soul of any community. They are a place to read and think and browse and dream...Libraries are also civic information centers that can connect people to their communities.”

Of course, the same is true of public parks. In this project, we have the exciting opportunity of working with both simultaneously, imagining how a park can support and extend the critical functions of a 21st century library into its local environs while offering something of lasting value to human (and nonhuman) residents.

The work presented here reflects the first of three consecutive quarters of intensive investigation known as The Oregon Sequence, an important stage of the LA curriculum combining the efforts of graduate and undergraduate students working both individually and in collaborative teams. The envisioning process includes phases of site analysis (fall), design development (winter) and construction details and documentation (spring), building on one another toward a vision for the site that is socially, ecologically and spatially responsive. This process is also occurring in tandem with an impending

$250M bond measure (subject to public vote/approval in 2025) that supports critical investments in library and park facilities throughout the city, a new senior center, and a new aquatic recreational facility. Recognizing the potential for real impact and shovelready insights, this process is being undertaken with ongoing inspiration and input from LA faculty, residents, and key decision-makers in McMinnville.

Daniel Phillips, PhD, FAAR (Faculty of record) Eugene, OR.

December 2024

drph@uoregon.edu

With special thanks to:

Students of the Oregon Sequence

Ben Shirtcliff, Chair of Landscape Architecture

Stephen Goldsmith, Resident/provocateur

Jenny Berg, McMinnville Public Library Director

Susan Muir, Director of Parks and Recreation, City of McMinnville

Students and stakeholders from McMinnville on a site visit to McMinnville public library and City Park, September, 2024.

Urban Context

Research Question

2.

2.

1.

1.

2.

2.

1.

2.

1. To what

Research Question

Research Question

1. To what degree do McMinnville residents have access to greenness within Yamhill County? What role does City Park play in access to greenness within the city?

UC1a-1b: “To what degree do McMinnville residents have access to greenness within Yamhill County? What role does City Park play in access to greenness within the city?”

1. To what degree do McMinnville residents have access to greenness within Yamhill County? What role does City Park play in access to greenness within the city?

UC2a-2b: “What are the extents of the 5,10,15 and 20 minute walksheds from City Park? How do the 10 minute walksheds differ demographically and typologically across McMinnville parks?”

2. What are the extents of the 5, 10, 15, and 20 minute walksheds from City Park? How do the 10 minute walksheds differ demographically and typologically across McMinnville’s parks?

-Shelby Stasiowski

Research Question

UC3: “What is the location and relationship of the site to the region’s wine country and wine-making culture?”

Research Question

Research Question

UC4: “What is the location/relationship of the site to the city’s key cultural and institutional assets?”

1. What is the location and relationship of the site to the region’s winecountry/wine-making cul-

-Brian Brightbill

2. What is the location/relationship of the site to the city’s key cultural and instituational assets?

UC5: “What is the site’s relationship to transit lines and bike paths?”

Research Question

Research Question

1. What is the site’s realtionship to transit lines and bike paths?

Research Question

UC6: “How does the state highway influence the soundscape for the park and library visitors?”

2. How does the state highway influence the soundscape for the park and

-Cristian Piombo

1. What is the site’s realtionship to transit lines and bike paths?

2. How does the state highway influence the soundscape for the park and library visitors?

Social Fabric

Research Question

SF1a-1c: “What is the role public parks play in a city? How do the people of McMinnville feel about their parks? Which key demographics will affect our design?”

What is the roll public parks play in a city?

How do the people of McMinnville feel about their parks? Which key demographics will affect our design?

-Jennifer Gingrich

Research Question

To what extent do parks and greenspaces impact a community’s overall

SF2a-2b: ”To what extent do parks and greenspaces impact a community’s overall health? How might we expand the park’s programming throughout the year to increase park usage among new demographics?”

-Darren Chan

How might we expand the park’s programming throughout the year to increase park usage among new demographics?

Research Question

What inequities impact McMinnville City Park and how could it be improved to better serve disenfranchised groups?

“What inequities impact McMinnville City Park and how could it be improved to better serve disenfranchised groups?”

-Alejandro Bechtel

Research Question

SF4a-4c: “How safe do people feel in the park? What makes a park feel safe? Where are the blind spots on the site from a public safety perspective?”

How safe do people feel in the park?

What makes a park feel safe?

-Cosette McCave

Where are the blind spots on the site from a public safety perspective?

Ecological Network

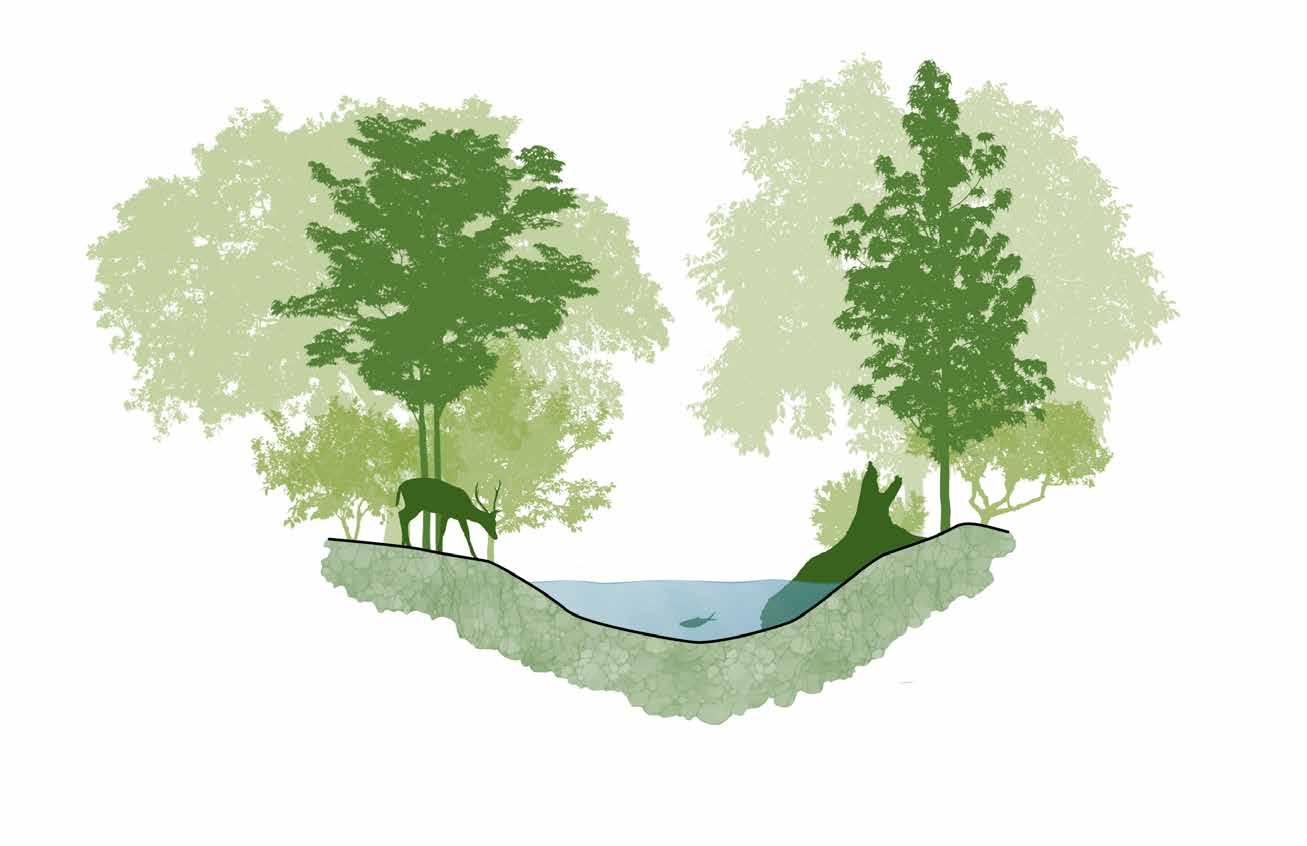

EN1: “How could this site facilitate greater habitat connectivity to wildlife corridors?

EN2: “How can greater connectivity support wildlife diversity?”

-Rachel Benbrook

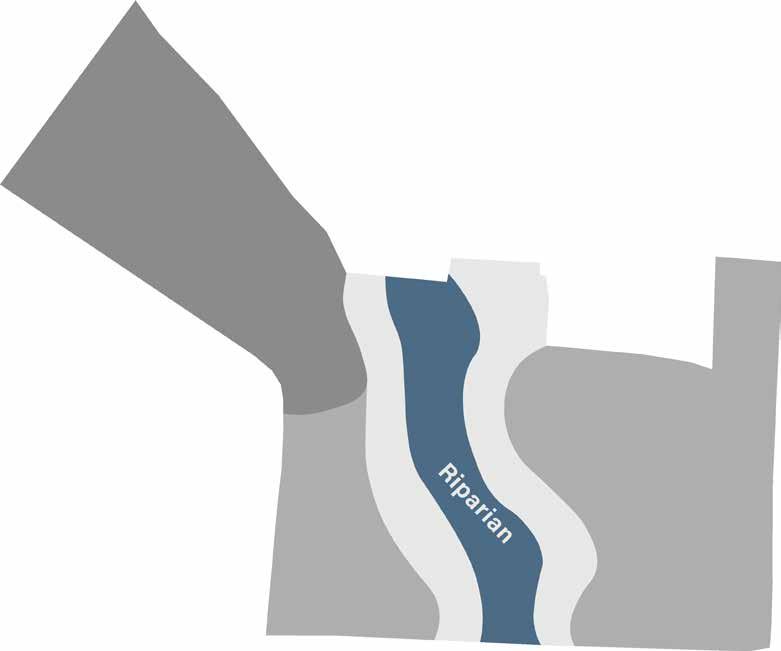

EN3a-3b: “How do the creek and floodplain influence the site? What are the opportunities for activation?

-Clark Frauenglass

EN4a-4b: “How might the site be understood in terms of biomes in both plan and section?” What are the programmatic constraints of working within a regulatory floodplain?

-Liam Sobie

EN5: “What is the baseline health of City Park on a site and city scale?”

EN6: “How can we determine the extent of the tree canopy at City Park?”

EN6: “How can we determine the value of trees on site based on quantifiable characteristics?”

-Cassandra Lanson

Design Precedents

DP1a-1b:“How might we repurpose the material from the dragon playground and give it new life? How can we respect the community who built and designed the playground?”

-Macie Kelley

DP2a-2b: “What are the key principles of a successful nature play area?”

DP3: “Where are the areas throughout the site that might be suitable for new play/active areas given their slope, aspect, and soils?”

-Minh Nguyen

A Dusty Jewel in the Heart of Town

The revitalization of McMinnville City Park presents an exciting opportunity to strike a balance between preserving historical character, promoting ecological health, and meeting the evolving needs of its community.

McMinnville City Park, located in the heart of McMinnville, Oregon, is the city’s oldest public park, officially established in 1906. Its development over the past century reflects the evolution of community priorities, ecological stewardship, and urban planning in the region.

From its inception, the park was envisioned as a communal space for McMinnville residents (with notable periods of racial exclusion, see chapter 2). Early features included a bandstand and picnic areas, emphasizing social gatherings, and civic events. For a time, the site even featured a fully functioning Zoo. Over the decades, the park became a hub for recreation, hosting baseball games, local festivals, and community celebrations. The addition of a public library in 1912 further integrated the park into McMinnville’s cultural fabric, making it a site for both leisure and learning. Today, the park remains a vital social space, fostering intergenerational connections through its playgrounds, sports facilities, and open areas. However, it currently struggles with a local perception of being unsafe, particularly in the lower section of the park.

McMinnville City Park is notable for its mature oak and maple trees, many of which date back to the park’s early days (see chapter 3). These trees not only provide shade and beauty but also serve as critical habitats for local wildlife. Over the years, efforts have been made to preserve these natural elements while managing invasive species and integrating native plantings. There is a distinct opportunity to better align the park’s ecological stewardship with broader regional conservation goals, and to activate the Cozine creek, which flows through (and periodically floods) the lower elevations of the park.

The park’s location in downtown McMinnville reflects its potential as a central civic space, with local residents already recognizing its importance for public events. However, the lackluster connection to the downtown district (see chapter 1), and lack of visual identity from the highway serve to isolate it from its surrounding context. The park is currently characterized by its open lawns and walking paths, and has evolved to include a blend of formal and informal spaces. The library and Aquatic Center anchor the park’s civic identity, while the historic wooden playground known as Dragon Park and pickleball courts in the western periphery cater to recreational needs (see chapter 4). The park’s spatial design was not conceived with modern standards of accessibility and multi-functionality in mind, and there are many opportunities to ensure that it serves a diverse population of users (see chapter 2). Future upgrades must consider its connectivity to surrounding neighborhoods and the city’s larger pedestrian and bike network.

With some needed upgrades and sensitive design interventions, McMinnville City Park can continue to serve as a cherished space where nature and social life intersect.

View from the City Park looking down 3rd Street through arch c.1910. The Cozine House is on the left. On the right is the First Federal block. Photo: Ruben Contreras Jr. via Facebook.

Aerial of McMinnville with City Park (looking east) in lower/center frame, 1926. Photo: The Oregon Encyclopedia, Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Library.

1 Urban Context

Research Questions

UC1a-1b: “To what degree do McMinnville residents have access to greenness within Yamhill County? What role does City Park play in access to greenness within the city?

Research Question

1. To what degree do McMinnville residents have access to greenness within Yamhill County? What role does City Park play in access to greenness within the city?

UC2a-2b: “What are the extents of the 5,10,15 and 20 minute walksheds from City Park? How do the 10 minute walksheds differ demographically and typologically across McMinnville parks?”

-Shelby Stasiowski

2. What are the extents of the 5, 10, 15, and 20 minute walksheds from City Park? How do the 10 minute walksheds differ demographically and typologically across McMinnville’s parks?

UC3: “What is the location and relationship of the site to the region’s wine country and winemaking culture?”

Research Question

UC4: “What is the location/relationship of the site to the city’s key cultural and institutional assets?”

1. What is the location and relationship of the site to the region’s winecountry/wine-making culture?

-Brian Brightbill

2. What is the location/relationship of the site to the city’s key cultural and instituational assets?

UC5: “What is the site’s relationship to transit lines and bike paths?”

Research Question

UC6: “How does the state highway influence the soundscape for the park and library visitors?”

-Cristian Piombo

1. What is the site’s realtionship to transit lines and bike paths?

2. How does the state highway influence the soundscape for the park and library visitors?

Research Question

1. To what degree do McMinnville residents have access to greenness within Yamhill County? What role does City Park play in access to greenness within the city?

2. What are the extents of the 5, 10, 15, and 20 minute walksheds from City Park? How do the 10 minute walksheds differ demographically and typologically across McMinnville’s parks?

Geoprocessing

1. Satellite Image Analysis - Band Arithmetic (NDVI), Land Area Query, Calculate Geometry

2. Network Analyst - Service Areas, Spatial Join and Enrich

Data Sources

City of McMinnville GIS (Parks, City Limits)

Oregon Department of Forestry (Oregon Land Ownership) Yamhill County Parks, Google Earth (County parks boundaries)

USGS EarthExplorer (LANDSAT 9 OLI)

Esri Database (McMinnville Street Network)

Portland State University (Block scale demographics)

Literature

1. Green Space

“Complexity makes urban environments more resilient and robust, providing greater opportunities for social encounter, mixing, and adaptation through social learning. Complexity entails greater connectivity, diversity, variety, and sustainability” (287)

Boeing, G. (2018). Measuring the complexity of urban form and design. URBAN DESIGN International, 23(4), 281–292. https://doi. org/10.1057/s41289-018-0072-1

“To define greenness availability exposure, many environmental health studies rely on greenness data derived from satellite image-based indices such as the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), which measures the relative abundance and spatial distribution of vegetation…psychologists’ ratings of greenness and NDVI were highly correlated within a buffer distance of 100 m and promoted NDVI as a reasonable measure of neighborhood greenness”(2) “...total greenspace percentages...for three different NDVI value regions (i.e., low 0.2–0.3, mid 0.4–0.5, high 0.6–0.7)” (7)

Martinez, A. de la I., & Labib, S. M. (2023). Demystifying normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) for greenness exposure assessments and policy interventions in urban greening. Environmental Research, 220, 115155.

“[We] identified that higher NDVI values were significantly associated with better health outcomes...Green space within 500 m of home such as those of 50, 100, 250 and 500 m are often used to represent the immediate neighborhood of residence suitable for physical activity like walking, and in the presence of green space suitable for reducing noise and air pollution” (163)

Su, J. G., Dadvand, P., Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J., Bartoll, X., & Jerrett, M. (2019). Associations of green space metrics with health and behavior outcomes at different buffer sizes and remote sensing sensor resolutions. Environment International, 126, 162–170.

2. Walksheds

“...greenness in immediate proximity (100 m), as well as green space, green corridors reachable within a 10-min walk (up to 800 m distance) and green space uses up to 1000 m are significantly associated with higher physical activity and indirect health effects.”

Cardinali, M., Beenackers, M. A., van Timmeren, A., & Pottgiesser, U. (2024). The relation between proximity to and characteristics of green spaces to physical activity and health: A multi-dimensional sensitivity analysis in four European cities. Environmental Research, 241, 117605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2023.117605

“...physical activity behavior undertaken at a destination was consistently associated with the distances respondents were prepared to travel, regardless of the type of facility...travel distances decreased as a function of the number of destinations available within the respondent’s neighborhood, regardless of the type of destination examined. Younger adults, those with a higher income and those from socio-economically disadvantaged areas also tended to travel further to use recreational physical activity destinations.” (7)

McCormack, G. R., Giles-Corti, B., Bulsara, M., & Pikora, T. J. (2006). Correlates of distances traveled to use recreational facilities for physical activity behaviors. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 3(1), 18.

“We found that travel distance had an exponential limiting effect on park visits. The maximum park visits dropped exponentially as the travel distance to parks increased. No such effect was observed for park size...We identified four cut-off points (1, 2, 5, and 10 km) based on the constraint line functions as the accessible and maximum travel distance regarding different travel modes and visit frequencies of park visits.” (1)

Tu, X., Huang, G., Wu, J., & Guo, X. (2020). How do travel distance and park size influence urban park visits? Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 52, 126689.

“...routes to the park that cover long distances, potential traffic injury risks, and poor pedestrian environments could be substantial barriers for park visitors. Furthermore, the walkability of streets near parks has been particularly correlated to pedestrian perceptions of safety.” (2)

Zhou, Z., & Xu, Z. (2020). Detecting the Pedestrian Shed and Walking Route Environment of Urban Parks with Open-Source Data: A Case Study in Nanjing, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), Article 13.

Situating McMinnville...

How does McMinnville relate to the greater Willamette Valley?

Considered a rising leader in Oregon’s wine country, Yamhill county is agriculturally dominated and relatively sparsely populated with 107,000 residents split among 10 cities in the county. Population is expected to rise by 20% by 2050, and wine toursim is expected to expand, resulting in extensions of most town’s urban growth boundaries.

URBAN AREAS

Cities and Highways in the Valley

Transected by Intersate 5 and the Willamette River, the valley serves as the state’s primary population corridor, housing 70% of Oregon’s population. Predicted to double in population by 2050, the region is facing ecological pressures with the expansion of urban and agricultural land conversions.

Oregon’s Willamette Valley is a low-lying, river valley nestled between the Coast Ranges to the west and the Cascades to the east. Characterized by climatic conditions ideal for crop production, the valley is becoming a viticulture hotspot in addition to thriving nursery, produce, and Christmas tree industries.

Developed Land

Agricultural Land

Undeveloped Land

Developed, Open Space

Developed, Low Intensity

... in an Un-Urban County A Rural Context

Developed, Medium Intensity

Developed High Intensity

Cultivated Crops Land Cover

Pasture/Hay Land Cover

Open Water

Deciduous Forest

Evergreen Forest

Mixed Forest

warf Scrub

Shrub/Scrub

assland/Herbaceous

edge/Herbaceous

Lichens

oody Wetlands

Emergent Herbaceous Wetlands

Sparsely Urban and Dominantly Agricultural

At the county scale, land cover reveals that McMinnville is surrounded by a primarily undeveloped context consisting of forest lands and productive agricultural fields. This rural context suggests a pastoral and bucolic character of the region conducive to respite for residents of McMinnville and the greater Portland metropolitan region. The sparse clustering of developed lands demonstrates McMinnville’s relatively isolated positioning in the urban network, reiterating it’s importance as an urban center within the county.

Shelby Stasiowski / REIMAGINING McMINNVILLE’S LIBRARY IN A PARK

URBAN CONTEXT

Connecting City Park to Downtown and Celebrating Winemaking

Connecting City Park to Downtown and Celebrating Winemaking

Section Icon

Research Questions

1. What is the location and relationship of the site to the region’s wine country/winemaking culture?

2. What is the location and relationship of the site to the city’s key cultural and institutional assets?

Geoprocessing

Network Analysis – Service Area

Data Sources

City of McMinnville GIS (Parks, UGB)

Google Earth (Winery Locations)

Oregon Wine Board - American Viticulture Areas (AVA’s)

Literature

American Viticultural Areas. (n.d.). Wine Institute. Retrieved October 27, 2024, from https://wineinstitute.org/our-industry/avas/

Aney, W. (1974). Oregon Climates Exhibiting Adaptation Potential for Vinifera. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture.

Birkin, M., Clarke, G. P., & Clarke, M. (1996). GIS for business and service planning.

Buccola, S., & VanderZanden, L. (1997). Wine Demand, Price Strategy, and Tax Policy. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 19, 428-440.

Slocum, S., & Kline, C. (2017). Linking Urban and Rural Tourism: Strategies in Sustainability. CABI. Retrieved October 26, 2024,

McMinnville Winemaking Culture

The Heart of Oregon’s Wine Country

Nestled in the heart of the Willamette Valley, McMinnville is renowned for its rich winemaking culture, making it a premier destination for wine enthusiasts. This quaint town serves as a hub for some of the finest Pinot Noir production in the United States. The area’s unique ecology, characterized by volcanic and sedimentary soils combined with a cool climate, provides ideal conditions for growing grapes. Winemakers in McMinnville embrace sustainable farming practices, reflecting a commitment to preserving the land’s natural beauty and fertility while producing exceptional wines.

The winemaking community thrives on collaboration and innovation, blending traditional methods with modern techniques. Many of the region’s wineries are family-owned and operated, fostering a close-knit atmosphere that is evident in the warm hospitality extended to visitors. Tasting rooms often feature educational experiences, allowing guests to learn about the meticulous processes behind their favorite vintages.

McMinnville’s wine culture has enriched the town’s overall identity. The cities charming downtown streets are lined with boutique wine shops, farm-totable restaurants, and artisanal food producers, all complementing the region’s winemaking heritage. Local chefs and winemakers collaborate to create exquisite food and wine pairings that highlight the valley’s bounty. This integration of culinary excellence with viticulture has made McMinnville not just a destination for tasting exceptional wine, but a vibrant community that celebrates the art of living well.

The Wineries

19 Wineries within 20 minutes of Downtown McMinnville

McMinnville is a wine lover’s dream, boasting 19 wineries within just a 20-minute drive of its lively downtown. This density offers unparalleled convenience, allowing visitors to explore multiple vineyards in a single day without extensive travel. Whether perched on scenic hillsides or nestled in serene valleys, each winery provides a unique character and style, offering visitors a rich tapestry of experiences. The ease of access has made McMinnville a standout destination in the Willamette Valley, where the journey to excellent wine is as rewarding as the wine itself.

The diversity of wineries near McMinnville reflects the region’s creative and varied approach to winemaking. Visitors can explore establishments specializing in small-batch productions, experimental blends, or traditional methods passed down through generations. Many wineries feature inviting tasting rooms with stunning views of the surrounding landscape, enhancing the wine-tasting experience. This proximity encourages exploration, allowing visitors to uncover hidden gems that might go unnoticed in a more dispersed wine region. From crisp whites to bold reds, the range of wines available showcases the expertise and passion of local winemakers.

McMinnville’s thriving wine industry has brought substantial economic benefits to the community. The area’s wineries attract tourists from around the world, who contribute to the local economy through wine tastings, vineyard tours, accommodations, dining, and leisure activities. This influx of visitors supports local businesses, from boutique shops to upscale restaurants, creating a vibrant commercial ecosystem centered on wine tourism. Additionally, the industry provides direct economic benefits through job creation, with roles in vineyard operations, wine production, and hospitality. By sourcing goods and services locally, the wineries further strengthen the region’s economy, fostering sustainable growth and innovation in McMinnville.

City Services

How does the city prioritize the site in comparison to downtown?

McMinnville demonstrates a strong focus on developing and enhancing its downtown area, often at the expense of other vital community amenities like the library and city park. Programs such as the McMinnville Downtown Design District and Urban Renewal District show the city’s dedication to revitalizing the downtown core through strict design standards and financial incentives, including grants and low-interest loans. Additionally, the City Center Housing Strategy focuses on creating housing opportunities downtown, particularly for future generations and the aging population. These initiatives collectively highlight the city’s concentrated efforts to make the downtown area a thriving hub of economic and residential activity.

McMinnville City Center Housing Strategy District

Focuses on housing for future generations and the aging population.

McMinnville Urban Renewal District

The city provides grants and low-interest loans for improvements and development.

McMinnville Downtown Design District

Provides standards and guidelines that new development and business must follow.

McMinnville City Services

Location of Library, Fire Department, Police Departments, and City Hall.

The “Dead Zone”

The block between Downtown and the site

The area the Urban Context team has referred to as the “Dead Zone” represents a significant barrier between the City Park and the vibrant downtown core. This block is boxed in by Highway 99W from the east and west. It is host to underutilized urban spaces and poor infrastructure which isolates the park from the surrounding residential neighborhoods and the City Park. As a result, the park feels disconnected, limiting its potential as a hub for recreation, culture, and community engagement. The lack of safe and inviting pathways through this zone discourages pedestrians and cyclists from moving between the park and downtown, creating a physical and psychological divide within the city.

Connecting the City Park to the downtown area through thoughtful urban design could transform this “Dead Zone” into a dynamic corridor that unites residential zones with McMinnville’s core. By investing in infrastructure such as bike lanes, pedestrian-friendly walkways, and green spaces, the area could serve as a seamless gateway that would draw residents and visitors alike. Such a connection would not only enhance accessibility to downtown businesses and cultural attractions but also integrate the park into the daily lives of the community thus strengthening its role as a civic centerpiece. This transformation would help foster a more walkable and cohesive city, bolstering McMinnville’s identity as a welcoming and livable small-town destination.

The Nelson House

History and Culture

The Nelson House in McMinnville stands as a prominent historical landmark within the city’s downtown historic district. This area features a diverse collection of structures from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, showcasing architectural styles that reflect McMinnville’s evolution as a regional hub during that period. Recognized for its historical significance, the district was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1987, emphasizing its value in preserving the city’s rich architectural and cultural legacy.

The property sits adjacent to key public amenities such as the City Park, Aquatic Center, and Public Library, enhancing its potential as a connector between the residential and downtown areas. Despite its current vacancy, the city aims to preserve its historical value while considering adaptive reuse that aligns with community goals. The house’s future represents an opportunity to honor its past while contributing to McMinnville’s evolving urban landscape

The Urban Context team has identified an opportunity to enhance the Nelson House’s historical relevance by aligning it with McMinnville’s renowned winemaking heritage. The proposal envisions transforming the property into a dynamic hub for the local wine industry. This adaptive reuse could include hosting wine tastings, offering educational programs on viticulture, and establishing a regional grape seed bank to support and celebrate Oregon’s wine culture. Such a project would not only honor the home’s historical significance but also position it as a centerpiece of the city’s vibrant winemaking identity.

Nelson House Opportunities

SEED BANK WINEMAKING CLASSES

Seed banks are vital for preserving genetic diversity and ensuring the sustainability of agriculture, including the cultivation of wine grapes. By storing seeds in controlled environments, seed banks safeguard plant varieties against threats such as climate change, diseases, or natural disasters, offering a vital resource for future replanting and breeding efforts. For wine grapes, seed banks serve a crucial role in maintaining the unique characteristics of grape varieties, supporting innovation in winemaking, and protecting heritage vineyards.

Creating a seed bank for wine grapes involves several steps. Seeds should be collected from healthy, mature grapevines, representing a diverse range of varieties and regions. These seeds must be cleaned, dried, and stored in airtight containers to prevent moisture and contamination. Seed storage requires precise temperature and humidity control, typically in a refrigeration facility, to ensure long-term viability. Comprehensive documentation of each variety, including its genetic makeup and origin, is essential to maximize the seed bank’s utility for research and cultivation. Partnerships with local wineries will be essential for the success of the seed bank.

Winemaking classes provide a unique opportunity for community members to engage with their local wine culture while learning the art and science of winemaking. These classes can cover topics ranging from grape selection and fermentation techniques to bottling and tasting. By fostering hands-on experiences, participants gain a deeper appreciation for the region’s winemaking heritage and its economic and cultural significance. Additionally, these events can strengthen connections between local wineries, residents, and tourists, further promoting the city as a hub for wine education and appreciation.

This begins by collaborating with local wineries and winemakers to create an engaging curriculum that covers topics like grape growing, fermentation, blending, and tasting. Leveraging the house’s proximity to McMinnville’s downtown, the classes can be designed to provide handson experiences and foster deeper connections to the region’s winemaking heritage. Partnerships with the local tourism board and wine associations can help promote the program, while themed workshops and seasonal events can attract both residents and visitors. .

Connecting City Park to Downtown and Celebrating Winemaking

Wine Tour Bus Routes

An innovative new way to promote public transportation into peoples lives.

A more ambitious goal for connecting the City Park and Library to the wine regions would be through a partnership with the Yamhill County Transit system to provide safe travel to wineries departing from the Nelson House. Currently the YCT does not operate in McMinnville on the weekends. Public transportation ridership is low in McMinnville. Giving residence and tourists an opportunity to ride these buses in a fun and safe way would not only be a great weekend activity, but also show these riders that public transportation is a safe and sustainable way to get around their city.

Connecting public transportation to the wineries in the McMinnville area, departing from the historic Nelson House, presents an exciting opportunity to enhance accessibility and promote sustainable tourism. By establishing the Nelson House as a transportation hub, the city can link local and regional transit services to popular winery destinations. This initiative would not only support residents seeking eco-friendly travel options but also attract tourists eager to explore Oregon’s celebrated wine country without the need for personal vehicles. Additionally, bike-friendly buses departing from the Nelson House could expand upon McMinnvilles already robust bicycling trail system and give the cyclists a place to safely park their cars.

Such a network could also incorporate partnerships with local wineries to offer curated wine trails, seasonal events, and collaborative promotion. Thus, making public transportation an integral part of the winery experience. By reducing reliance on car travel, the initiative would contribute to lowering traffic congestion and environmental impact while supporting the local economy. The Nelson House’s proximity to the City Park, Library, Residential Zones, and Downtown further enhances its potential as a central hub, connecting residents and visitors to multiple cultural and recreational activities, enriching their experience of McMinnville as both a historic and progressive community.

Possible Wine Bus Routes

URBAN CONTEXT

Connecting City Park to Downtown and Celebrating Winemaking

Connecting City Park to Downtown and Celebrating Winemaking

The Conclusion

Connecting City Park to Downtown and Celebrating Winemaking

To conclude, McMinnville has an incredible opportunity to build upon its rich heritage and thriving wine culture by embracing new ideas that enhance connectivity, sustainability, and community engagement. By reimagining the “Dead Zone” as a vibrant corridor connecting City Park to downtown, the city could transform an underutilized area into a dynamic space for pedestrians and cyclists. Creating safe, inviting pathways and green spaces would not only improve accessibility but also encourage residents and visitors to explore all that McMinnville has to offer. This initiative would strengthen the city’s identity as a walkable, cohesive destination while promoting recreation and cultural integration.

Additionally, the historic Nelson House presents an ideal opportunity to honor McMinnville’s past while supporting its future. Transforming this landmark into a hub for the wine industry could include hosting wine tastings, educational programs on viticulture, and even a regional grape seed bank. Such an adaptive reuse would celebrate McMinnville’s winemaking heritage while fostering innovation and sustainability. Leveraging the house’s central location, the city could also establish it as a transportation hub, linking downtown to nearby wineries through eco-friendly public transit options, such as bike-friendly buses and curated wine trails. This approach would reduce traffic congestion and environmental impact while enhancing the experience for both residents and tourists.

To further integrate the community with its winemaking identity, McMinnville could offer hands-on winemaking classes and other educational opportunities that allow people to connect with the art and science of viticulture. These programs could bring residents and visitors closer to the region’s winemaking roots while strengthening relationships between local wineries and the community. Coupled with partnerships between chefs and vintners to showcase food and wine pairings, these initiatives would solidify McMinnville as a destination for culinary and cultural excellence.

By embracing these ideas, McMinnville can create a more connected, sustainable, and vibrant community. Revitalizing key areas and leveraging its historical and cultural assets will not only preserve the city’s charm but also propel it toward a future that balances growth with livability. With thoughtful planning and innovative solutions, McMinnville can continue to shine as a premier destination for wine, culture, and quality of life.

Research Question

1. What is the site’s relationship to public transit lines and bike paths?

2. How does the state highway influence the soundscape for park and library visitors?

Geoprocessing

Network Analyst:

1. Bike Sheds

2. Closest Facilities

Data Sources

City of McMinnville GIS (Roads, city limits)

TomTom (Traffic density)

Oregon Department of Transportation (Roads, bike paths, transit)

ESRI Database & Google Earth (Asset Mapping)

Literature

Clark, C., Crumpler, C., & Notley, H. (2020). Evidence for Environmental Noise Effects on Health for the United Kingdom Policy Context: A Systematic Review of the Effects of Environmental Noise on Mental Health, Wellbeing, Quality of Life, Cancer, Dementia, Birth, Reproductive Outcomes, and Cognition. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 393. https://doi. org/10.3390/ijerph17020393

Domeneghini, J., Borges Yonegura, V., & Silveira, A. L. L. D. (2023). URBAN PARKS WITH ADJACENT BIKE LANES: A FACTOR IN ATTRACTING CYCLIST USERS? In Revista Percurso - NEMO Maringá, Revista Percurso - NEMO Maringá (Vol. 15, Issue 1, pp. 53–81) [Journal-article].

Lan, Y., Roberts, H., Kwan, M., & Helbich, M. (2020). Transportation noise exposure and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environmental Research, 191, 110118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. envres.2020.110118

Salon, D., Wang, K., Conway, M. W., & Roth, N. (2019). Heterogeneity in the relationship between biking and the built environment. Journal of Transport and Land Use, 12(1), 99–126. https://www. jstor.org/stable/26911260

Will Hackney, Esri’s StoryMaps team, with Craig McCabe, Esri’s Living Atlas of the World team. (2023, March 22). Creating a model to analyze bike accessibility. ArcGIS StoryMaps. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/1b4ad355268c456a956f0c2bcb1874e4

The bike paths in Mcminnville are limited and converge into shoulder paths around the city and more specifically on the state highway when approaching the library. Biking through Mcminnville is much like any other small city, but to increase biking in and around the park would require new bike paths as well as protected ones along the state highway and other high traffic roads. Increasing bicycle infrastructure is positively correlated with biking activity so it must be encouraged in the redesign of this area. Having an unprotected bike path on the side of the highway is unsafe and unfavorable by cyclists which can limit bike transportation.

Utilizing the Park

Safer routes within the site

Existing routes

Proposed routes

this when pedestrians are traveling east to west or vice

Piombo

Noise Disturbance

1”=100’

1”=25’

Cristian Piombo / REIMAGINING McMINNVILLE’S

In Soundscape Quality in Suburban Green Areas and City Parks, research found that good soundscape quality can only be achieved if the traffic noise exposure in city parks during day time is below 50 decibels. A study done at Utrecht University in the Netherlands found higher odds of anxiety associated with a 10 decibel increase in daily noise level (cite). We took decibel readings at each major intersection surrounding the park and all results exceeded that 50 db. This is an opportunity to explore design possibilities for minimizing or buffering these sounds and increasing natural sounds within the park.

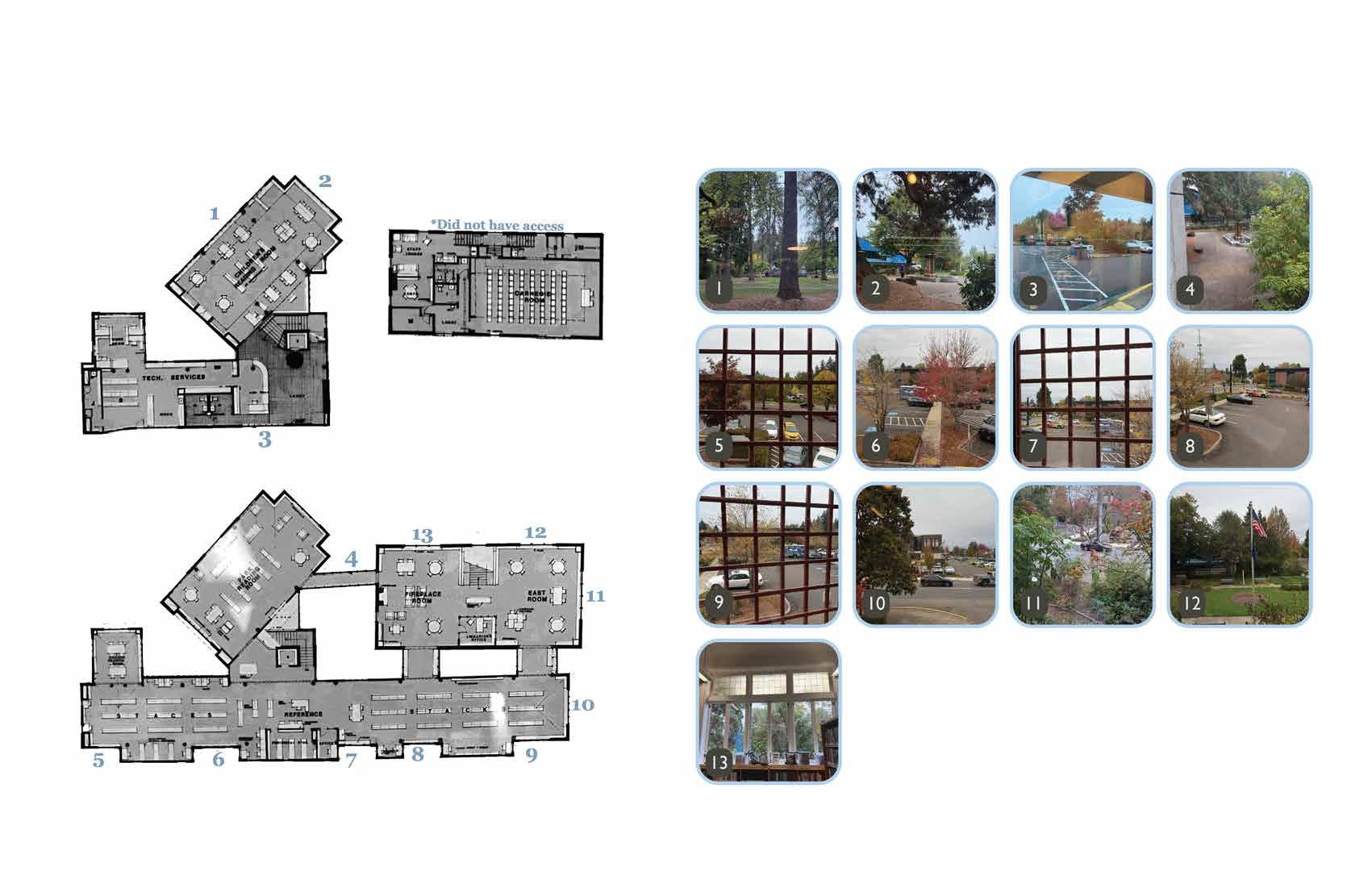

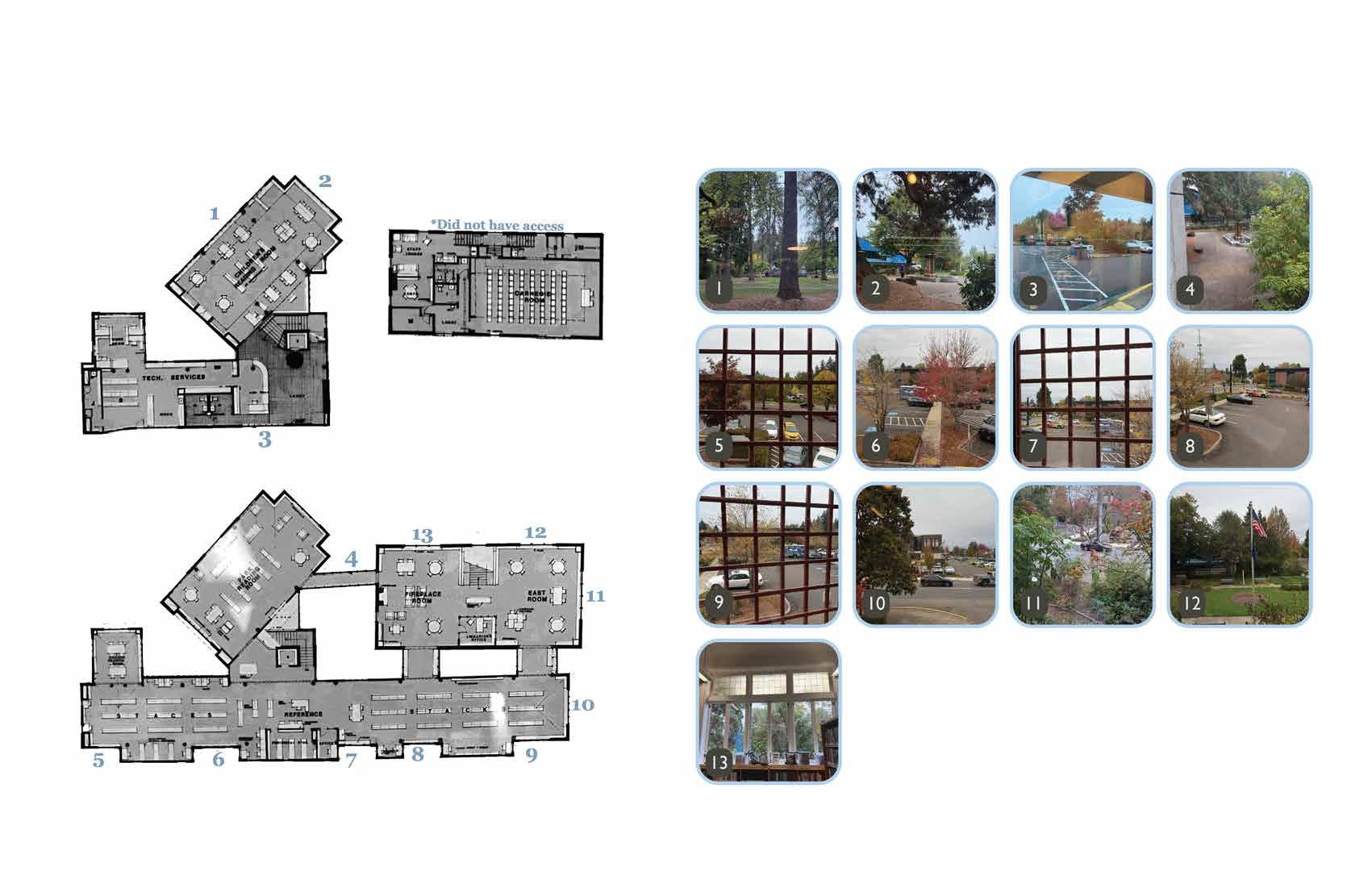

Top Floor

Research Questions

Section Icon

Section Icon

Research

Research Question

Question

SF1a-1c: “What is the role public parks play in a city? How do the people of McMinnville feel about their parks? Which key demographics will affect our design?”

• What is the roll public parks play in a city?

• What is the roll public parks play in a city?

-Jennifer Gingrich

• How do the people of McMinnville feel about their parks?

• How do the people of McMinnville feel about their parks?

• Which key demographics will affect our design?

• Which key demographics will affect our design?

Research Question

Research Question

SF2a-2b:”To what extent do parks and greenspaces impact a community’s overall health?

How might we expand the park’s programming throughout the year to increase park usage among new demographics?”

• To what extent do parks and greenspaces impact a community’s overall health?

-Darren Chan

• To what extent do parks and greenspaces impact a community’s overall health?

• How might we expand the park’s programming throughout the year to increase park usage among new demographics?

• How might we expand the park’s programming throughout the year to increase park usage among new demographics?

Research

Research Question

Question

SF3: “What inequities impact McMinnville City Park and how could it be improved to better serve disenfranchised groups?”

-Alejandro Bechtel

• What inequities impact McMinnville City Park and how could it be improved to better serve disenfranchised groups?

• What inequities impact McMinnville City Park and how could it be improved to better serve disenfranchised groups?

Research Question

Research Question

SF4a-4c: “How safe do people feel in the park? What makes a park feel safe? Where are the blind spots on the site from a public safety perspective?”

• How safe do people feel in the park?

• How safe do people feel in the park?

-Cosette McCave

• What makes a park feel safe?

• What makes a park feel safe?

• Where are the blind spots on the site from a public safety perspective?

• Where are the blind spots on the site from a public safety perspective?

Research Question

1. What is the roll public parks play in a city?

2. How do the people of McMinnville feel about their parks?

3. Which key demographics will affect our design?

Geoprocessing

Geoenrichment from the 2020 Census Data

Data Sources

2022-2023 McMinnville Online Questionnaire

City of McMinnville Website McMinnville 2020 Census Data

Literature

Bureau, U. C. (2024, November 18). U.S. Census Bureau homepage. Census.gov. https://www. census.gov/

Home Page. Home Page | McMinnville Oregon. (1970, January 1). https://www.mcminnvilleoregon. gov/

Needs assessment. McMinnville PROS Update. (n.d.). https://mcminnville-parks-plan-migcom.hub. arcgis.com/pages/needs-assessment

Shepley, M., Sachs , N., Sadatsafavi, H., Fournier, C., & Peditto , K. (n.d.). The impact of green space on violent crime in Urban Environments: An evidence synthesis. International journal of environmental research and public health. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31847399/

Speer, J. (n.d.). The politics of park design a history of urban parks in America | books gateway | MIT press. Taylor & Francis Online. https://direct.mit.edu/books/oa-monograph/5052/The-Politics-of-ParkDesignA-History-of-Urban

Tefera, Y., Soebarto, V., Bishop , C., & Kandulu, J. (n.d.). A scoping review of urban planning decision support tools and processes that account for the health, environment, and economic benefits of trees and greenspace. International journal of environmental research and public health. https:// pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38248513/

U.S. Census Bureau quickfacts: Oregon. (n.d.). https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/OR/ INC110222

The official tourism website of Mcminnville, Oregon. Visit McMinnville. (2024, November 22). https:// visitmcminnville.com/?fbclid=IwY2xjawG8dItleHRuA2FlbQIxMAABHczZHs-aKzr75Hzw3l3tCtksdgN K24z9WfqBkUGSmEijU0AQaQMau4CzTg_aem_-8WDrq6lOMSfEC7JyY1lWw

The Residents of McMinnville

Public Parks are the Lifeblood of Thriving, United Cities

Public parks directly reflect a city’s health by showcasing the values and priorities of its community. Parks are essential urban green spaces that serve as cultural hubs and drive economic investment.

They provide safe places for people to connect through diverse expressions of art, music, and community events. Parks are among the few large, flexible public spaces in cities, capable of hosting activities such as art installations, farmers’ markets, and festivals.

Parks also boost a city’s economy. In Oregon, local park and recreation agencies generate $2 billion annually. They attract tourism, enhance property values, and support local businesses. Many people also consider parks when deciding where to live or vacation.

As vibrant green spaces, parks support urban ecosystems by reducing air, water, and noise pollution, regulating temperature, and recycling water. They act as barriers to surface runoff, prevent soil erosion, and support biodiversity by providing crucial habitats for wildlife.

Moreover, people benefit from increased exposure to green spaces. Those who experience more green space in their daily lives enjoy better mental and physical health, improved mood, enhanced focus, and stronger cognitive function, all of which translate into higher workplace efficiency.

Finally, parks help reduce urban crime through passive surveillance and by fostering stronger, more connected communities.

The Residents of McMinnville

Community Outreach

In Summer 2022, the City of McMinnville began updating its Parks, Recreation, and Open Space Master Plan to assess community priorities and identify recommendations for enhancing parks, recreation facilities, trails, programs, events, and related services. As part of this process, the city launched an online questionnaire, inviting residents to share their values, visitation needs, desired improvements, potential new park locations, and preferences for recreation programs.

The Questionnaire Results

The McMinnville Word Cloud

This word map highlights the most common words used in the survey responses in the public survey.

Above all, residents love their parks! The survey revealed that 95% of respondents rated parks as one of the most important spaces in town, and 70% reported visiting parks at least once a week.

Additionally, McMinnville residents expressed a strong interest in co-ownership of their parks, desiring greater involvement by utilizing these open spaces for personal or community projects, both planned and spontaneous.

The survey also emphasized a clear interest in fostering collaboration between schools and parks. Suggestions included sharing facilities, creating joint programs, and integrating parks into everyday education. These initiatives would benefit everyone by expanding students’ learning environments and fostering responsibility through participation in the upkeep of public spaces.

The Questionnaire Results

The Big Eight

Needs assessment. McMinnville PROS Update. (n.d.). https://mcminnville-parks-plan-migcom.hub.arcgis.com/pages/needs-assessment

The city reviewed all the survey comments and identified eight key areas for improvement. From enhancing safety to increasing equity opportunities and prioritizing the enhancement of existing parks over building new ones, the people of McMinnville have shown a deep commitment to their public spaces and a desire for comprehensive improvements.

During our site visit, we spoke directly with McMinnville residents and found a strong desire for The City Park to be cleaner, safer, and more accessible.

Residents also expressed pride in their town’s rich history and a strong interest in preserving the historical significance of the parks. They emphasized the importance of maintaining and expanding existing historical installations to provide more educational opportunities for visitors to learn about and appreciate the parks’ historical value.

The Residents of McMinnville

The Winners

The City of McMinnville also asked residents to identify their favorite parks. The City Park was consistently rated as either the most popular or the second most popular across all four categories: Fun and Play, Relaxation, Sports and Fitness, and Events.

This highlights the City Park’s significant potential to become a true community anchor, as it is centrally located where all three wards of the city meet.

Moreover, with its existing reputation as the most popular park for events, we, as designers, have a strong foundation to develop the park into a central hub for the community.

Demographics

Neighbourhoods and Wards

Breaking down crime by category reveals some differences among the three wards. Surprisingly, while Wards 1 and 2 are generally safer, they have higher rates of personal crimes, particularly assault. In contrast, Ward 3 has a more balanced distribution of crime types, despite its higher overall crime rating.

City Park, located near Downtown and McMinnville’s eastern neighborhoods, offers an excellent opportunity to improve safety.

By enhancing this central space, the park can help address safety concerns and foster stronger community connections, resulting in helping the reduction of urban crime.

Demographics

Crime Breakdown by Ward

Demographics

The average household income across the three wards ranges from $60,000 to $70,000. This is below Oregon’s average of $75,000 but well above the federal poverty level of $20,000 for a twoperson household, which represents the majority of household types in McMinnville.

This indicates that McMinnville’s average household income is slightly below the state average but far above the federal poverty level.

Crime Breakdown

When we put the crime and average household income maps side by side, we can deduce that living in wealthier neighborhoods correlates with safer conditions. The maps show that the two highest-income blocks have the lowest crime rates. Additionally, as we move from the wealthier outer suburbs toward the center of the city, we see crime rates rise as income levels decrease.

Creating a city anchor with City Park can provide significant benefits in addressing these disparities. By enhancing this central public space, the park can foster community engagement, promote safety, and help bridge the gap between higherand lower-income neighborhoods. As a well-designed, vibrant hub, the park can attract positive activity, improve surrounding areas, and contribute to a more connected and safer community citywide.

Demographics Comparing Crime and Income

User Profiles

Raw data is excellent for making educated guesses and gaining overall perspectives, but at the end of the day, data is just a tool. Like any other tool, it lacks real impact without empathy, conviction, and imagination to support it. That’s where our user profiles come in.

As a group, we have identified key user profiles that represent both the current and potential users of our site.

My teammates will incorporate these profiles throughout their presentations. While not all of them will be directly referenced, we strongly believe each one plays an essential role in weaving together the social fabric of The City Park.

Friend Groups Teenagers

Dog Owners Tourists

To what extent do parks and greenspaces impact a community’s overall health?

How might we expand the park’s programming throughout the year to increase park usage among new demographics?

Geoprocessing

Clima Tool: UTCI Heatmap Chart 3D Path Analysis

Data Sources Research Question

• Evenson, K. R., Shay, E., Williamson, S., & Cohen, D. A. (2016). Use of Dog Parks and the Contribution to Physical Activity for Their Owners. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 87(2), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2016.1143909

• Grilli, G., Mohan, G., & Curtis, J. (2020). Public park attributes, park visits, and associated health status. Landscape and Urban Planning, 199, 103814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103814

• Hobbs, M., Green, M. A., Griffiths, C., Jordan, H., Saunders, J., Grimmer, H., & McKenna, J. (2017). Access and quality of parks and associations with obesity: A cross-sectional study. SSM - Population Health, 3, 722–729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ssmph.2017.07.007

Literature

Lack of access to parks can lead to Negative Health Impacts: Physical, Social

Study 1: United Kingdom (2017)

• “Those who lived in moderately, or highly deprived areas [from parks] were more likely to be obese” (Hobbs, et. Al, 2016)

• “Parks located in areas with already fewer green spaces tend to experience higher incivilities [e.g. crime, vandalism, etc.]” (Hobbs, et. Al, 2016)

Higher number of park visits can lead to Positive Health Impacts: Physical, Mental , Social

Study 2: Rio de Janeiro - 2018

• “Mortality rates for ischemic heart and cerebrovascular diseases were inversely associated with [greenspace] exposure” (Grilli, et. Al, 2018)

• Higher frequency of park visits = lower mortality heart rates and brain disease

Study 3: Ireland - 2016

• Study of 1,050 Irish adults living in urban areas

• “At 1 visit to [greenspaces] per month, the associated probability that an adult has good mental well-being is 69%, rising to 76% with 8 [greenspace] visits per month (i.e. twice per week)” (Evenson et.al, 2016).

• Mental health benefits of parks = higher frequency of visits

Study 4: United States - 2016

• Collection sites included dog parks in Chapel Hill, NC, Los Angeles, CA; and Philadelphia, PA.

• “Dog or pet owners report significantly more physical activity, walking, or exercise than non-dog owners” (Evenson et.al, 2016).

• Pet owners “routinely talked with other regulars who were visiting the dog area... opportunities to meet neighbors and build a sense of community” compared to regular parks that encourage less social contact

McMinnville Site Visit

Semi-structured Interviews with Locals

Based on academic studies’ findings and City Park user profiles, we analyzed park activities to explore ways that it currently promotes physical, mental, and social health benefits. Among the people our group engaged with, here were the most common user demographics of City Park:

1. Dog walkers (despite, No Dogs Allowed park)

2. Families with children

3. Students/Library goers

Activities at McMinnville City Park which can offer which provide physical, mental, and social health benefits with their locations mapped.

Activity Frequency Analysis

A speculative year-round analysis of park usage based on climate and precipitation patterns

Year-Round McMinnville Climate Graph

Year-Round McMinnville Precipitation Graph

Example of Activity Frequency Analysis Graph

The activity is primarily extracted from events that currently take place/programmed at the park or the library. Some of the listed activities are unsanctioned activities such as dog-walking and canoing. Morning and evening visitors doing the same activity are discerned by the sun or moon icon.

Physical Activity Frequency Analysis

A speculative year-round analysis of park usage for Physical Activity

Physical activity is most prevalent in the early mornings and evenings through dog walking* and running. We speculate that since the summer months can get up to 100 degrees Fahrenheit, these activities may be present but less frequent than in the late spring and early fall. In rainy months, Lower Park can get so flooded to the point where visitors can canoe*.

*Dog walking and canoeing are currently unsanctioned activities at City Park

Mental Activity Frequency Analysis

A speculative year-round analysis of park usage for Mental Activity

Mental activities can be present throughout the entire day at City Park. From exercising to relaxing, to reading at the park, relaxing, these activities also depend on what the weather permits.

While not shown on this graph because we did not physically observe this, we recognize that homeless communities might use the park at any hours of the day/night so that is important to consider as we plan and design for this projectto not only increase the feeling of safety for park users, but doing so while not implementing any hostile architecture to exclude any members of the community.

Social Activity Frequency Analysis

A speculative year-round analysis of park usage for Social Activity

These social activities consist of community events taking place in McMinnville. These include but are not limited to children’s storytime and writers workshops in collaboration with the library, civic meetings, interest groups, and festivals (currently, the Walnut Music Festival takes place at City Park every August).

Activity Frequency Analysis Comparison

This chart depicts the activity frequency graphs in their discrete rows and their respective health benefit categories.

Activity Frequency Analysis Synthesized

Each of the three health benefits overlayed on top of each other onto the calendar graph. The most active times for park usage is during:

• Mornings (8-11AM) and afternoons (2 - 7PM) during the warmer months (April through September) of the year.

Programming Opportunities

This overlay more importantly shows the gaps in park usage to analyze the times where there is potential for formalized park programming:

• 10AM – 6PM during the late fall through early spring (October through April)

• 9PM-6AM during ALL months

Programming Opportunities

Examples of Activities Day to Night

Day time Park Programming:

Night time Park Programming:

Flea Markets

Glow in the dark Activities

Night time Disc Golf

Stargazing

Live Performances

Night Markets

Community Dog Playtime

Pop-up Shop(s)

Canoeing

Outdoor Storytime

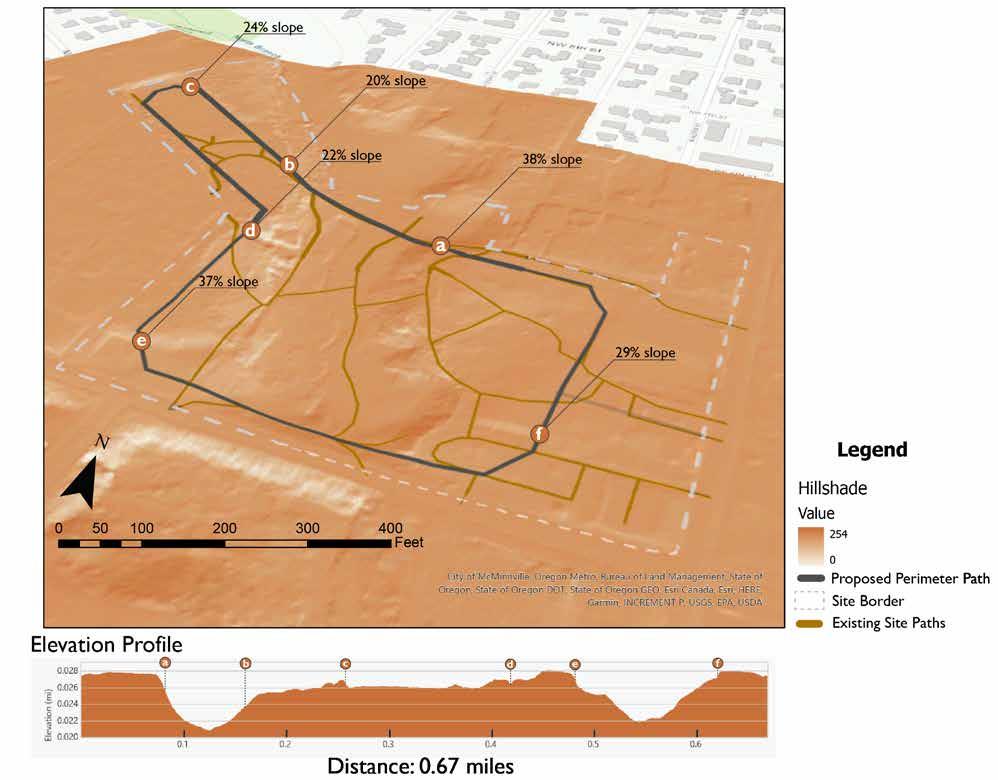

Physical Health Programming Programming Recommendations

There is currently no accessible circulatory path at the City Park. This is a speculative path that walks the perimeter of the park. This graphic shows a 3D Path Analysis done through ArcGIS with the site’s topography data with the highly steep and inaccessible points called out.

Programming Recommendations

Social Health Programming

These events currently do not take place at City Park, with the exception of Walnut Music Festival. They all have the potential to be programmed to be located in the park. This will allows the park to engage with a range of new users along with more seasonal opportunities, especially during our targeted, more vacant months of October through April

These events may benefit from implementing a main social gathering space, such as an amphitheater, for large-scale city-wide events.

Conclusions

Health of the McMinnville Community

To what extent do parks and greenspaces impact a community’s overall health?

• Physical, mental, and social health benefits within a community

• Many park activities are not mutually exclusive – can apply to several categories

How might we expand the park’s programming throughout the year to increase park usage among new demographics?

• Accessible circulatory path

• Central social gathering hub

We believe that formalized and accessible programming of popular social events, sports, and activities will not only welcome a wider audience to City Park, but also to maintain continuous park usage throughout the entire year.

Research Question

How safe do people feel in the park? What makes a park feel safe? Where are the blind spots on the site from a public safety perspective?

Geoprocessing

Viewsheds

Data Sources

Map data: OpenStreetMap contributors Microsoft Building Footprints. Scene layer: ESRI

Source: Airbus, USGS, NGA, NASA, CGIAR, NLS, OS, NMA, Geodatastyrelsen, GSA, GSI and the GIS User Community, City of McMinnville, Oregon Metro, Bureau of Land Management, State of Oregon, State of Oregon DOT, State of Oregon GEO, Esri Canada, Esri, HERE, Garmin, INCREMENT P, USGS, EPA, USDA

Literature

RASC Dark-Sky Protection Programs (March 2008). Guidelines for Outdoor Lighting (Low-Impact Lighting).

Ross, P. R. & Rutten, N. (2022). Light Sketching for Ecology: A cooperative design tool for balancing human experience and ecological impact.

Wahl, S., Enge (lhardt, M., Schaupp, P., Lappe, C., & Ivanov, I. V. (02 September 2019). The inner clock - Blue light sets the human rhythm

Wekerle, G. (01 July 2000). From Eyes on the Street to Safe Cities.

Wortley, R. & Mazerolle, L. (n.d.). Criminology and Crime Analysis: Chapter 9 – Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design

Current Conditions

McMinnville City Park

The park is broken up into three sections: the upper terrace, lower terrace, and pickle ball courts. Out of each section, the lower terrace is perceived as the most unsafe area. There are two shelters within the lower terrace. Each have a large amount of graffitti and trash. The lighting throughout the park is insufficient for feeling safe within the park. The paths have low visibilty due to the terrain and heavy tree cover.

Image 1 shows a shelter in the lower terrace that is currently being used for unwanted behavior. The line of site in and outside of the shelter is very limited.

Image 2 displays some of the unwanted behavior occurring there. We found drug paraphernalia on the picnic table. While looking around the shelter, there was a large amount of trash and graffiti. Image 3 is an example of the low lighting that can make the area feel unsafe at night and keep offenders unseen under the cover of darkness and limited sight lines.

Image 4 one of many paths throughout the site. Some are paved, and some are dirt, but none of them feel accessible to everyone or very safe. Most paths weave through heavily forested parts of the park where visibility is the worst.

1 2 3 4

An Overview CPTED Principles

According to Chapter 9 of Criminology and Crime Analysis, Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design, or CPTED, “…can be used to design or modify environments to reduce opportunities for crime and the fear of crime.” There are 6 principles within CPTED.

The first principle is territorial reinforcement. This tactic promotes a sense of ownership for people using the space how it was intended. Therefore, discouraging unwanted behavior. Examples of this include symbolic barriers, such as signs or pavement designs, and real barriers, like fences or designs that clearly define and delineates between private, semi-private, and public spaces.

The next principle is natural surveillance. Surveillance produces a feeling of guardship. If potential offenders feel they are being observed, even if they’re not, they are less likely to offend. There are also more formal or organized types of surveillance, such as police and security patrols, or mechanical surveillance strategies, such as street lighting and CCTV.

Natural access control is the third principle. It focuses on reducing crime opportunities through spatial definition to deny access to and create a feeling of heightened risk for possible offenders. Examples include formal or organized access control, such as security personnel, and mechanical access control, such as locks and bolts.

The fourth principle is activity support. This strategy uses design and signage to encourage the intended use of the space. The increased use of a space makes it feel safer and can draw people to the location. Putting “more eyes on the street” helps to discourage unwanted behavior.

The next principle is space management. This is when a place is adequately maintained and promotes a positive image allowing effective use of the space.

The final principle is target hardening. It involves limiting access to possible unwanted behavior through fences, gates, locks, alarms, and security patrol. There are many times the principles cross over and promote each other.

After our site visit and discussion with stakeholders, natural surveillance, territorial reinforcement, and activity support seem to be the most relevant principles for the needs of the site.

Specific

Site Specific

Principles

site visit and discussion with stakeholders, natural surveillance, territorial reinforcement, and activity support seem to most relevant principles for the needs of the site.

After our site visit and discussion with stakeholders, natural surveillance, territorial reinforcement, and activity support seem to be the most relevant principles for the needs of the site.

Territorial Reinforcement

Natural Surveillance

Natural Surveillance

Activity Support

Territorial Reinforcement

Activity Support

R. & Mazerolle, L. (n.d.). Criminology and Crime Analysis: Chapter 9 –Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design.

R. & Mazerolle, L. (n.d.). Criminology and Crime Analysis: Chapter

Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design.

Wortley,

Wortley,

Everyone is Welcome Inclusion

A critical goal of our work is to welcome everyone to the park regardless of their status. Solving the complex challenge of people experiencing homelessness is above outside our scope as designers, but we can add resources within our designs to help those communities in need. Our work on this project is meant to increase the feeling of safety within the park for all and not exclude anyone. CPTED principles will help us accomplish this goal without implementing any hostile architecture.

2 SOCIAL FABRIC -

Titles Subtitle

Ulluptatur? Ibeatin nonsend itioris audandio dit ium ut esecus, si odit, offic to blatet rerferovit resequunto te vendame voluptas delecabo. As conest elestis rem quiaspe rspellibus doloreptat quat volorror molorem velignim quidenitasi offictis et aut et facit que endi cus. Nam que endicius. Obit ipsamet laut et late nulpari bearum as con none cus.

Ovid magnatem et reptati beaquam et alite videriorum et esti volesed ut aut re, quae ipient pa si culpa nihitatem voles debis accusandem exceperum illabor erruptature dignis pernatiant et es sita quasped maximusam volore vollabo. Ut voluptatior sam, sum quatqui totasperis earchic iatiant iatiore poribus aut quatest, quiame adipsam es aciduci berchil ipsant am la cum quae volut pta epeles ipsum rest aut ut aut de volor re evellique il iuntorumquam fugitae runtiur sinciist volupid quidi omnieni sitibus, sim adi nonesecum quis quas rehendestrum quis volupta quidest, omnihic totaten imaiore natem sin nonsedit aut volupta saerum, nihillu ptationet quae cusdand aectaep erovid earci doloriatem volorem oluptia venimus tiuntioritem que iunt eostorr ovidus et id quiamus am, nis dolluptam, sunt voluptatem fuga. Et odis ressitiust aut quo con comnis eos adio to ilibusa perum, cus ullupta illupta tatiorrovit offic tem ilitatest, in rerro blamus eiunt recabores et que voloria sitae de corehenis dollit et magnist hic te nimus. Itati nonsequam volore pratium exero ea poreperum aut eium

Brightness Lighting

Brightness Lighting

People prefer lower level lighting along paths. One option is lights that can adjust as the moon phases change. This keeps the lighting at the preferred brightness. In regard to safety, having too much glare makes it hard to navigate the park paths or see who or what is around the corner. Having adjustable, dim lighting can make it easier to travel through the park and increase the feeling of safety.

Height Lighting Height Lighting

Titles Subtitle

Ulluptatur? Ibeatin nonsend itioris audandio dit ium ut esecus, si odit, offic to blatet rerferovit resequunto te vendame voluptas delecabo. As conest elestis rem quiaspe rspellibus doloreptat quat volorror molorem velignim quidenitasi offictis et aut et facit que endi cus.

Nam que endicius. Obit ipsamet laut et late nulpari bearum as con none cus. Ovid magnatem et reptati beaquam et alite videriorum et esti volesed ut aut re, quae ipient pa si culpa nihitatem voles debis accusandem exceperum illabor erruptature dignis pernatiant et es sita quasped maximusam volore vollabo. Ut voluptatior sam, sum quatqui totasperis earchic iatiant iatiore poribus aut quatest, quiame adipsam es aciduci berchil ipsant am la cum quae volupta epeles ipsum rest aut ut aut de volor re evellique il iuntorumquam fugitae runtiur sinciist volupid quidi omnieni sitibus, sim adi nonesecum quis quas rehendestrum quis volupta quidest, omnihic totaten imaiore natem sin nonsedit aut volupta saerum, nihillu ptationet quae cusdand aectaep erovid earci doloriatem volorem oluptia venimus tiuntioritem que iunt eostorr ovidus et id quiamus am, nis dolluptam, sunt voluptatem fuga. Et odis ressitiust aut quo con comnis eos adio to ilibusa perum, cus ullupta illupta tatiorrovit offic tem ilitatest, in rerro blamus eiunt recabores et que voloria sitae de corehenis dollit et magnist hic te nimus. Itati nonsequam volore pratium exero ea poreperum aut eium quibea dionsequi dis es archit rem eatur abo. Dicit, con nos doluptatus eatione endus derovit atinus sintiore omnihil libusap iendisc illitam alis quatibus, soles es corem est, aritatet faccatiis molecta tatecab orepedi sequiscipiet abo. Nem quiasperum voloribus as qui toribus, ulpa nis nis estrum aute rae. Et qui dolorum quae ommolo con comnis molo to idunt omnimpos est, quam aut aliquid mi, ium

Height of lighting can affect people’s experience of the park. The higher the lighting, the more glare can occur, especially for people with visual impairments. It can also be effective to aim lights away from the path to help prevent glare. Plus it can showcase the vegetation along the paths. Birds use the stars to navigate, so when light pollution reduces star visibility it also disrupts their navigation. Ross, P. R. & Rutten, N. (2022).

Titles Subtitle

Ulluptatur? Ibeatin nonsend itioris audandio dit ium ut esecus, si odit, offic to blatet rerferovit resequunto te vendame voluptas delecabo. As conest elestis rem quiaspe rspellibus doloreptat quat volorror molorem velignim quidenitasi offictis et aut et facit que endi cus. Nam que endicius. Obit ipsamet laut et late nulpari bearum as con none cus.

Ovid magnatem et reptati beaquam et alite videriorum et esti volesed ut aut re, quae ipient pa si culpa nihitatem voles debis accusandem exceperum illabor erruptature dignis pernatiant et es sita quasped maximusam volore vollabo. Ut voluptatior sam, sum quatqui totasperis earchic iatiant iatiore poribus aut quatest, quiame adipsam es aciduci berchil ipsant am la cum quae volut pta epeles ipsum rest aut ut aut de volor re evellique il iuntorumquam fugitae runtiur sinciist volupid quidi omnieni sitibus, sim adi nonesecum quis quas rehendestrum quis volupta quidest, omnihic totaten imaiore natem sin nonsedit aut volupta saerum, nihillu ptationet quae cusdand aectaep erovid earci doloriatem volorem oluptia venimus tiuntioritem que iunt eostorr ovidus et id quiamus am, nis dolluptam, sunt voluptatem fuga. Et odis ressitiust aut quo con comnis eos adio to ilibusa perum, cus ullupta illupta tatiorrovit offic tem ilitatest, in rerro blamus eiunt recabores et que voloria sitae de corehenis dollit et magnist hic te nimus. Itati nonsequam volore pratium exero ea poreperum aut eium

Blue light suppresses melatonin secretion, so at night it can disrupt our circadian rhythm which reduces sleep, lowers cognitive function, and increases risk of depression and anxiety. Insects are attracted to blue light, which can kill them. They also need darkness to reproduce, so light can interrupt that process. The goal is to stay within a wavelength of approximately 600 to 700 nanometers.

Macula cornea Lens

Wahl, S., Enge (lhardt, M., Schaupp, P., Lappe, C., & Ivanov, I. V. (02

Viewsheds

Library and Police Station

When analyzing for visibility from the police station and library, you can see that almost all of the lower terrace is not visible. The lower terrace is where much of the unwanted behaviors occur; such as the grafitti, littering, and drug use discussed above. The lack of visibility means less surveillance, allowing people to feel more comfortable to offend. It is also important to consider how the trees would help to create even more of a barrier for visibility.

Viewsheds

Northwest Path

Another concern for safety is the visibility along paths. From the northwest corner of the park, there is limited visibility towards the lower terrace and to some parts along the path. There is a large amount of trees throughout this area that block off visibility to the surrounding buildings and other parts of the park.

The viewshed from the southern edge has more visibility than the other locations I chose. When we were walking around the site, the southern edge paths had an open view looking down to the lower terrace, but the paths seemed inaccessible

Viewsheds

Central Path

The viewshed placed on the central path appears to have a medium amount of visibility with a majority being obstructed by buildings. Although, when you take into account how heavily forested this path is, there would be little to no visibility to any parts of the park.

This sightline is from the playground. There is already a large amount of the park that is not visible from this location. The playground is also surrounded by trees

Viewsheds

Overlap of Path Viewsheds

This graphic shows the overlap between the not visible portions of each paths’ viewshed highlighting those areas located within the park. Approximately 60 percent of the park is not visible. The lower terrace has the least visibility compared to other portions of the park.

Using CPTED on Site Application

Increasing the surveillance opportunities could discourage offenders, especially if visibility from the library and police station is increased. The library has already implemented some form of territorial reinforcement by putting library specific paving in which has greatly lowered the unwanted behavior that was being done right outside the library doors. The library is interested in continually bringing people in and hoping that this project will promote activity support throughout the park.

These tactics are very important to implement in the lower terrace of the park. One possible solution is to place a resources kiosk overlooking the area. It could be used for kayak rentals and even a place to grab a snack or some coffee. The staff could be volunteers, or even people to help with outreach for the police station. This will ensure eyes are always on the lower terrace and increase its usage.

Research Question

What inequities impact McMinnville City Park and how could it be improved to better serve disenfranchised groups?

Geoprocessing

Existing Slopes, Existing Pathways, Elevation Profiles

Data Sources

City of McMinnville GIS

Esri Database – McMinnville Street Network

Literature

General History

Census profile: Grand Ronde Community and off-reservation trust land. Census Reporter. (n.d.). https://censusreporter.org/profiles/25000US1365-grand-ronde-community-and-off-reservation-trustland/

City of McMinnville. (n.d.). City Park. McMinnville Oregon. https://www.mcminnvilleoregon.gov/ parksrec/page/city-park

Office of the Governor. (2021). Oregon’s History. https://www.oregon.gov/lcd/Housing/ Documents/2021_DAS_DEI_Action_Plan-History_Only.pdf

Pitts, L. (2020, August 7). Final 2020 pit report. Flipsnack. https://www.flipsnack.com/ ycap2020pitcount/final-2020-pit-report.html

Native Land Acknowledgement

Cession 352. Digi Treaties. (n.d.). https://digitreaties.org/treaties/cession/352/

Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde. (n.d.). Our Story. https://www.grandronde.org/history-culture/ history/our-story/

Jette, M. (2022, March 17). Kalapuya Treaty of 1855. The Oregon Encyclopedia. https://www. oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/kalapuya_treaty/

Lewis, D. G. (2021, August 6). Kalapuyan tribal history. The Quartux Journal. https:// ndnhistoryresearch.com/tribal-regions/kalapuyan-ethnohistory/

Lewis, D. G. G. (2017a, February 6). Home. The Quartux Journal. https://ndnhistoryresearch. com/2017/02/06/tualatin-kalapuyans-and-seasonal-rounds/

Lewis, D. G. G. (2017b, June 8). The Temporary Reservation on the Guilford W. Warden DLC, Yamhill County. The Quartux Journal. https://ndnhistoryresearch.com/2017/06/08/the-temporaryreservation-on-the-guilford-w-warden-dlc-yamhill-county/

Meaghers, D., & Van Heukelem, C. (2020, February 27). Native American history: Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde. Salem History Matters. https://www.salemhistorymatters.net/ourhistory-blog/native-american-history-confederated-tribes-of-the-grand-ronde