ISBN Prefix: 978-9966-092-40-3

ISBN Prefix: 978-9966-092-40-3

Half a century ago, a group of architects armed only with a vision intentionally got together in Malta to conceive the idea of an association of architects in the Commonwealth. Resolutions were made in that inaugural conference in 1965, the Commonwealth Association of Architects (CAA) was born and with that, the proverbial journey of a thousand miles for this profession in the Commonwealth began.

The CAA Golden Jubilee Commemorative Book traces this journey right from inception to create a fact-file about the Association, detailing its structure, profiles of the member organisations, schools of architecture and activities in the Commonwealth. Its forte is the priceless memoirs of past office-bearers reminiscing on the highs and challenges of their tenure.

In the characteristic fashion of publications meant for architects, the editorial team aspired to make this piece of work easy on the eye when telling each story by interspersing every captivating account with timeless photographs and images, a marked difference in style from its predecessor, the CAA Handbook. Although devoted exclusively to activities of this day

of architects in Commonwealth countries, it is hoped that this book will be a useful source, providing information to member organisations, schools of architecture, individuals, governments and official bodies both within and outside the Commonwealth.

For this reason, we carry information about the Commonwealth generally to remind the reader about the whole Commonwealth family including those countries we hope will soon join the fraternity but where at present there are no institutes, associations or societies of architects. Messages from the Queen, key individuals, professional organisations and other well-wishers with whom the CAA has over the years had a very close and productive engagement, go on to underscore the fact that, in bringing professionals of the world together, the CAA is a first among equals.

There are people who live in a dream world, and there are people who face reality; and then there are those who turn one into the other. If, by dint of their calling, turning dreams into reality is what architects do for a living, then a gathering of architects to celebrate can be no less than an ethereal event. The launch of this publication has found its perfect timing.

At fifty years since its inception the Commonwealth Association of Architects is sixteen years younger than its parent association, the Commonwealth, and twenty years younger than the United Nations at its seventieth anniversary this year. This lineage is central to understanding the CAA as an idea and an institution and what distinguishes it from any number of other national and international bodies. As an idea it shares the founding vision of the UN and the Commonwealth Association to articulate human survival, to uphold human unity, and to advance human dignity. As an institution it is the oldest international institution that is specifically concerned with human habitation towards survival, unity, and dignity: Architecture. Its accomplishments are nested within the broad history of architecture, its values within social and scientific advances in history, and its composition within the process of increasing social and political unification that has motivated the Commonwealth and culminates in the UN.

The history of this Association endows it with a legacy and a mission to provide a proactive platform of action for the three aims of Survival, Unity, and Dignity for humankind as it pursues its collective work, and its members continue their individual creative achievements. The Association is not alone in this mission. The three aspects of this mission are indeed those that are articulated in the UN’s fundamental agenda:

“Dignity, People, Planet, Prosperity, Partnerships, and Justice: these are six essential elements of an agenda for human and sustainable development which would enable nations to grow and develop in inclusive ways within the boundaries set by nature. This is a transformative agenda, and it is badly needed.”*

As this book on the 50th Anniversary shows, this association has come a long way since its inception. It has met many challenges in the course of its evolution and growth as would be expected. It has done much to advance architecture through the sharing of experience in individual practice, and in the importance of collective action. Institutions are the necessary means as well as the measure of collective achievements towards providing for the future of a profession. the CAA has done much to help in such institutionalization. An important part of this effort has been the CAA’s contribution and interest in architectural education. It has actively advanced this interest by establishing the first internationally formal system of validation for architectural programmesone that endures to the present. At 50 CAA is still in its formative years. That is cause for celebration. What we celebrate is not just the history of its past. We regard the past as aprologue for a future in which the vision of this association is even more relevant, and its collective energies more urgently needed to fulfill the fundamental agenda of the future.

The 50th Anniversary of the Commonwealth Association of Architects is a time to reaffirm the central place of architecture in the history of human civilization, and the growing need to organize individual and collective efforts and ideas.

The Commonwealth embodies the vision of a world united in recognition of the essential contribution of each culture to the vitality of the human legacy, without dominance of one culture over another. This is a balance that is as precious as it is precarious, and which challenges those bodies such as the Commonwealth Association of Architects to whom this legacy is entrusted to uphold and advance it. The history of how it has met this challenge successfully is indeed cause for

celebration at its 50th anniversary. Human advances in our means and values and ideals have enriched our culture and extended our reach and horizons beyond our own confines. So should our aspirations, and our efforts to apply those advances to meeting the practical needs of societies world-wide.

This is not an individual task. It requires cooperation and organization in the form of institutions that can bring together resources and maintain them in effective working constructs. This is the vision implicit in the formation of both the Commonwealth and the Commonwealth of Architects. The recognition and affirmation of this vision is indeed cause for celebration and best wishes for its continued effort in the future.

Building resilience is a Commonwealth priority, and is vital to realising our Commonwealth vision of nations and communities that are better able to withstand shocks – whether these are generated by external crises, natural disasters or the impact of climate change.

Architects contribute to building resilience both literally and figuratively. It is therefore fitting that in marking its Golden Jubilee and fifty years of service to our member states collectively, the Commonwealth Architects Association should take the theme of ‘Designing City Resilience’. The built environment has undergone enormous transformations over the past five decades, and the majority of our citizens now inhabit cityscapes and depend on infrastructures that in many respects would barely be recognisable to those who founded the CAA in 1965.

The social and economic impact of such change in the lives of our citizens is immense, and the degrees of global, regional, and local connection and interdependence have greatly increased in our rapidly compacting world. Commonwealth links do much to facilitate international collaboration, and to advance education and understanding between professionals working in a rich diversity of physical environments and cultural contexts. As a ‘network of networks’ the Commonwealth derives much of it strength from connections and partnership, whether formal or informal, that thrive independently of

official links. The depth and vitality of these ties makes the Commonwealth distinctive among international groupings of nations for the sense of kinship and affinity that exists between the people of its member states, and the ease with which they are able to work together.

The CAA is a fine example of how formal collaboration and networking between professionals in the Commonwealth can provide an extremely valuable platform for mutual support and for the validation of qualifications. This maintains confidence in the quality of architectural education provided by schools, and results overall in the progressive raising of professional standards in our member states. It can also contribute to a significant broadening of experience for individual practitioners.

In commending the CAA for its contribution to Commonwealth cohesion and international understanding over fifty years, we are able to draw fresh encouragement as we recall the dedication and energy of many eminent architects who have contributed to development and progress in countries throughout the Commonwealth. Carrying forward their work, and building on the strong foundations laid by earlier generations, gives cause to celebrate our rich inheritance. This leads us to reach out with confidence in a spirit of mutual respect and understanding to the promise of future Commonwealth cooperation, professional fellowship, and global connection.

Iam pleased to send this message of felicitation and warmest good wishes to the Commonwealth Association of Architects on the occasion of its Golden Jubilee celebrations. The Commonwealth Association of Architects (CAA), with its dedication to the advancement of architecture, performs a most valuable service in promoting cooperation among member associations of architects in the Commonwealth. It has a commendable focus on the path to social progress through the advances of architecture in the world today.

In the past 50 years the CAA has contributed much towards the development of professional standards, and the use of innovative approaches to widen the scope and knowledge of architecture, to improve the built environment; and thus work towards social and economic development, in many countries of the Commonwealth. These

celebrations mark recognition of five decades of service to the Profession of Architecture, with a fresh commitment to further progress in the field and facing up to the challenges ahead.

I wish the Commonwealth Association of Architects the best in the celebrations of this Golden Jubilee, and in achieving new heights of success in the future.

This year, CAA celebrates its 50th anniversary. As the President, it is my privilege to mark this milestone, which is indeed an extraordinary accomplishment and epitomizes the will, determination and lasting success of an organization that has worked tirelessly towards advancing the mission of architecture and protecting the interests of its members.

CAA’s 50th anniversary is intended to be more than just a celebration; it is an opportunity to lay the foundations for CAA’s next 50 years - and beyond. This Golden Jubilee, will guide our direction into the future where our voice will be heard, our ideas will be received, and the impact of our contributions to society will be fully realized. I believe the energy of this event will firmly establish CAA among the pantheon of regional organizations.

CAA has grown and flourished due to the commitment of our members to its founding vision, the pioneering leadership of distinguished past presidents, their Councils and member organizations. During the past year in particular, the Council has taken several initiatives bringing in much needed innovations in re-branding CAA. I sincerely appreciate all their efforts and the teamwork. I am humbled by what we have so far accomplished, thrilled by what we are going to accomplish in the coming years, and convinced that the true message of this association is that together we can continue to uphold and to extend the reach of our field, Architecture, as

the primal expression of human survival and humanism as its value system.

CAA, through its activities, is working toward a Commonwealth in tune with the future as an organization that draws on its history, plays to its strengths, vigorously pursues its member’s common interests and seizes the opportunities open to it to shape a better world. Thus in response to the changing times, that CAA embarked on a process of restructuring and repositioning with a Strategic Plan ‘Vision 2025’ renewing our enduring commitment to the values and principles of the Commonwealth.

This Vision endorsed the principles of the Commonwealth’s Accord for Enhancing Development Effectiveness and its commitment to the rule of law, good governance, respect for diversity and human dignity, opposition to discrimination, and the promotion of peoplecentred and sustainable development. The focus was on delivering within a results-based framework and with priorities that reflected CAA’s comparative advantage.

With a broad-based consultative process, Vision 2025 has prioritized working on all necessary steps through our professional services to support the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) and objectives of Agenda 21. The 2013–2016 period has been one of assessment of this Vision and deliberations on the new targets that would succeed them after 2016.

CAA’s Resolution in 2013 urging governments of Caribbean countries to implement legislation to regularize the profession of architecture and to register only professionally qualified architects in their respective countries will go a long way securing a strong future.

This is our role in Advocacy. The opportunity of reaching over 1.5 million people at ‘Transcending Horizons’ the first international exhibition organized by CAA on the eve of CHOGM 2013, in Colombo Sri Lanka marked a time of transformation for the organization. CAA was visible in advocating with the Heads of Governments with a Resolution insisting on the need to build Urban Resilience on matters relating to the Built Environment. We made it clear that the commonwealth must address climate change and its impacts with extreme weather already causing billions of dollars in damage and flooding washing away coastal infrastructure, and the world is already at a tipping point. The International Summit by RIBA during our Golden Jubilee, on the theme ’Designing City Resilience’ is taking this important message beyond its frontiers.

Practicing our professional Advocacy as agreed in the CAA Strategy for Advocacy; also in areas of Governance, Fighting poverty, Human rights, cross-connecting civil society, education, and sustainable development, we shall look beyond our shores to engagement with the world in ways that are both exciting and challenging.

CAA recognizes and values it place in the global development community and the strategic importance of the Commonwealth community of architects in taking up new and emerging critical issues of the future. It is incumbent on the CAA to promote many projects such as the ‘Listing of Specialist Architects’ Architects’ and P4P (Projects for Partnerships). While I am indeed happy that CAA is launching these projects on the eve of our Golden Jubilee, projects of this nature will make CAA not only relevant but also useful for practices, with commercial benefits to all stake holders.

The New Vision for the Commonwealth, in times of ongoing social and technological change places on the CAA a responsibility to achieve and maintain a position at the forefront of innovation in educational and validation of architectural schools, which has been one of the flag-ship activities of the association. CAA intends to pursue this activity with renewed vigor.

Today, CAA stands at a historically critical moment, a time of great challenges and opportunities. While we have achieved a great deal, there is much more to do as we move toward our lofty goal. I believe the best days of CAA are yet to come. I invite all architects in the commonwealth to join us on this epic journey; let us move forward with purpose and passion. The future is ours to create- let us write the most glorious chapter ever for the Commonwealth Association of Architects.

Stephen R.Hodder, MBE

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) is delighted to be hosting the Commonwealth Association of Architects (CAA) 50th Anniversary from 15th-19th June 2015 in London.

The week-long programme celebrates the CAA’s first 50 years while also looking to the future. It incorporates the CAA’s general business such as meetings of its Council and General Assembly together with a significant International Summit on 16th17th June focusing on the theme “Designing City Resilience”. The event also forms part of the London Festival of Architecture which comprises a programme of activities, including exhibitions and talks, during the month of June. The list of speakers at the Summit include the Commonwealth Secretary General and the government’s Chief Scientific Officer.

The General Assembly and the Summit will be accompanied by the announcement of the results of the CAA Student’s Competition followed by the RIBA President’s reception with a formal banquet organised by the Worshipful Company of Chartered Architects, to be held within the spectacular surroundings of London’s famous Drapers Hall.

The RIBA is a vibrant organisation that reflects not only its long heritage but also the world of today. British architecture in the 21st Century has an almost unrivalled reputation around the world for daring, innovation, creativity and flair. From Beijing to New York and Doha to Mumbai, the expertise of our members is playing a major role in redefining the world’s cities and creating extraordinary buildings.

The UK has become an important global hub for architecture with many thousands heading here to study and set up practice. Of all the world’s cities, London has a greater concentration of architects’ practices,

engineering and built-environment consultancies than anywhere else. This preeminence means that British architecture today is a global venture. Working across all sector types – from airports to art galleries, stadia to skyscrapers - practices based in the UK are responsible for bringing to life some of the most outstanding and celebrated structures in the world. For both large and small architectural firms, working internationally is an essential part of what they do and architecture has emerged as one of our most significant and visible creative exports.

The continuing pressure on our cities coupled with the effects of climate change continue to challenge the profession everywhere. The success of RIBA members in international markets has been largely due to their ability to adapt to changing circumstances, coupled with their worldleading approaches to sustainability and their willingness to respond to different cultures and contexts, embrace new technology and pioneer best practice.

RIBA has been actively supporting its members in meeting these demands, and is actively engaged in the development of new technologies such as Building Information Modelling (BIM), which is an integrated digital platform billed to revolutionise the way buildings are delivered in the future, creating better outcomes and efficiencies for clients.

As part of its support for the CAA’s 50th anniversary celebrations, the RIBA will be hosting an international Summit focused firmly on the future and on the topic ‘Designing City Resilience’.

Recognising how the interdependency of systems, professions, vision, leadership, technology and design creativity can create cities that are resilient to the physical, social and economic challenges they face in a fast-

changing world, Designing City Resilience has been created to foster and support an international exchange of ideas between organisations, professions, sectors and city leaders to bring world-class thinking to the current and future challenges faced by cities across the globe.

Designing City Resilience 2015 will provide a platform for organisations to forge international relationships, prototype ideas, share knowledge and experiences and work together to deliver suitable solutions to local and global challenges caused by urbanisation, climate change and trauma. The two-day Summit offers a mix of presentations and practical working groups to:

• Promote transition to the theme of resilience from the humanitarian sector into the consciousness of public/private sector stakeholders

• Better define the theme of resilience in so far as it relates to cities

• Highlight the need for a new paradigm addressing the complexities and interdependencies associated with resilient cities

• Provide a forum for sharing experiences and exploring new ideas for achieving city resilience

The aim of the Summit will be to develop a set of key principles; a roadmap for change that will enable governments and the private sector to work together to strengthen economic, political and physical infrastructure and make cities adaptable, vibrant and robust. These solutions will be based on cross-fertilisation of ideas, interconnectedness, interdependency and inter-operability. Outputs from the event will form the basis both for a publication and a roadmap for change.

The Summit will also create a unique forum for policymakers, practitioners and business leaders to come together around the important theme of city resilience.

RIBA and the CAA look forward to engaging their members with globally important issues such as these in the years ahead.

As we look to the future, it is clear that unparalleled challenges and opportunities exist in creating sustainable, resilient cities in an increasingly interconnected and complex world which will require new approaches and partnerships, the breaking down of barriers and a process of constant innovation.

Designing City Resilience will bring together key groups involved in: design and construction; development and infrastructure; city leadership and governance; insurance and finance; technology and communicationsto share ideas, create strategies and to recommend and implement meaningful principles to make better cities capable of coping with the stresses of mass urbanization, climate change and unexpected shocks to the system.

to unite the architects of the world without any form of discrimination.

The Commonwealth Association of Architects, aneminent organization of practising architects in Commonwealth countries, shares the International Union of Architects’ commitment to architectural education, research, and professional development. The CAA and the UIA demonstrated their common values by signing a Memorandum of Understanding in 2010.

International organisations are crucial in influencing ethical and socially responsible development throughout the world. During the UIA World Congress in Durban in 2014, CAA endorsed the UIA Declaration for 2050 Imperatives, thus enlisting Commonwealth architects and their professional associations

in the global struggle for a sustainable built environment, and a better world. Throughout its 50 years of existence, CAA’s network of member institutes has been instrumental in leading the development of the architectural profession.

It is my pleasure to acknowledge that most CAA member institutes are also members of the International Union of Architects. That means that our activities which impact the profession are complementary. The diversity of our members symbolises the diversity of today’s architectural world. Together, the UIA and CAA enrich the development and meaning of architecture globally.

In this time of celebration for the Commonwealth Association of Architects, I wish you a happy 50th anniversary and look forward to meeting representatives from all CAA member institutes in London in June 2015. The mutual cooperation and coordination between UIA and CAA should be reaffirmed for the next 50 years.

On the occasion of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Commonwealth Association of Architects (CAA), it is both a pleasure and an honour for me to express congratulations and good wishes on behalf of ARCASIA. Our two associations have always had a close affiliation throughout our history since six of ARCASIA founding institutions were also members of the CAA. Since 1965, the CAA has been faithfully committed to advancing

the practice of architecture, architecture education, promoting awareness of global issues, as well as forging close cooperation within its member institutes. These endeavors have uplifted the architecture profession through all regions of the world. I wish to commend the Commonwealth Association of Architects for its contribution to the architecture profession worldwide. ARCASIA pledges our full support to the CAA objectives and initiatives to further improve our wonderful profession. We also wish to strengthen a close working relationship between our two associations even further.

Once again, on behalf of ARCASIA, I wish to congratulate the CAA and offer my best wishes for a memorable anniversary celebration and continued success.

Times may change, but some things are only transformed. The links set up by the Commonwealth Association came from a world interconnected by trade of goods and political influence. ACE‘s collaboration with the CAA has been based on knowledge exchange, principally on matters relating to architectural education and practice.

Together we promote high quality professional standards and ethics and affirm the basic principles of professionalism internationally. We are bound by the fact that some of our Member Organisations are also part of the CAA – Cyprus, Malta, the UK. More importantly, we are all part of the network of architects committed to advancing architectural quality, supporting sustainable development, ensuring high standards of qualification, advocating quality in architectural practice and fostering cross-

border collaboration. We now face a new reality – more than just an economic crisis which suggests a temporary state – that will not go away. It is a situation to which we must adjust and for which we must prepare. Together we face the challenges of climate change, regeneration of our cities, fuel scarcity, standards of education, access to markets and the unemployment of our young professionals.

We must respond by settings our own standards which must be high and aspirational. By practising responsibly, we should regain the confidence that brings with it the recognition and credibility that may have been eroded over the years. In a shrinking world, where opportunities are globalised, barriers are being dismantled and collaboration is more important that ever.

We congratulate the CAA on its 50th anniversary and commend it for the excellent work it has done for its members and for society over the years. We look forward to a reinforced and ever closer relationship in the future.

CAA - How it all began

The CAA had its origin in a meeting of representatives of Commonwealth architectural institutes and societies when it became apparent that the time had come for a closer, structured and more explicit form of association amongst professional practitioners of architecture within the Commonwealth than periodic conferences on an informal basis.

The following two articles were originally published in the 25th anniversary publication of the CAA and have been extracted from the ‘Commonwealth Association of Architects 25 Years of Achievement 1965 - 1990’.

By Geoffrey Rowe

The beginning of the CAA I suppose, in some ways could be attributed indirectly to Bill Holford (Sir William Holford, eventually Lord Holford) when President of the RIBA around 1960 -1961. I say “indirectly” because during his Presidency Bill Holford felt strongly that the Royal Charter was out-of-date and inappropriate to the profession in the sixties. He discussed his ideas with senior RIBA council members and Presidents of Allied Societies like myself (I represented the West Yorkshire Society of Architects at that time on the RIBA Council).

He received a large measure of agreement that major changes were needed and accordingly held discussions on an informal basis with representatives of the Privy Council, Gordon Ricketts then Secretary of the RIBA being in attendance. By the time Robert Matthew became President (Later Sir Robert Matthew) the Privy Council had indicated that in principle they would agree to a new Royal Charter although they pointed out -and rightly -that it was likely to be a time-consuming procedure. I was asked to join the Charter Committee in 1962, and was elected Chairman of the Allied Societies and Vice President of the RIBA, remaining in these positions throughout the 1962/3 and 1963/4 sessions.

All the U.K Societies and Associations (and even some Chapters) were represented. Incidentally Ireland was represented both by the Ulster and Eire Presidents! Sir Robert Matthew realised that though small in numbers in the RIBA Council, the Overseas Societies who were in alliance with the RIBA represented a substantial part of the RIBA’s membership both numerically and in their importance. He also knew that the new Charter was likely to end the Alliance of U.K Societies with the RIBA on a formal basis, and to establish a system of Regionalisation. With a new system of voting for the RIBA Council, with nationally and regionally elected members in the proportion of approximately one National councillor to two Regional councillors, this was inevitable.

The old Societies, Branches and Chapters would no longer exist in “Alliance” with the

RIBA, their place being taken by a Regional and Branch structure to which funds would be voted annually by RIBA Council. There would be neither formal nor informal representation on RIBA Council by Overseas Allied Societies, so some formula had to be devised to assist RIBA members overseas in a practical way, without assuming responsibility in a patronising sense, once alliance had ceased.

Sir Robert suggested that he would take over the overseas problems and that would assume responsibility for the U.K through my Chairmanship of the Allied Societies Conference. Whilst I was consulting my colleagues in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales Sir Robert consulted with colleagues from Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, South Africa and other parts of Africa. We had countless meetings with the Commonwealth Institute (whose headquarters building in London Sir Robert’s firm designed); the Commonwealth Foundation; the Board of Trade, and the Foreign Office as well as the Privy Council. Eventually we all reached agreement on the provisions for the new Charter and the setting up of a Commonwealth Association of Architects which was to be supported initially by a grant annually from the Commonwealth Foundation.

It was clearly understood that the grant was not to be of a permanent nature and should only pertain until the CAA became self-supporting. This might be achieved through a per capita membership levy on membership subscriptions paid by all CAA member Institutes or Associations. A meeting was held in Malta which I could not attend as was in the U.S.A. But I will not enlarge further except to say that I know Robert always had firmly in his mind that the CAA should become truly regional in its working, and that it should be strong enough through its constituent members to influence the way that the UIA should go. He certainly showed the way himself when he became President of the UIA and it was a sad loss to Architecture all over the world when he died in 1976.

This first exploratory conference was an outstanding success and… no one walked out. We decided to recommend the establishment of a Commonwealth Association of Architects serving five geographical regions “without distinction of politics, race or religion”. We set up a steering committee under the chairmanship of Robert Matthew to define objectives and to work out the details, and we accepted an invitation from our chairman to hold the Inaugural Conference in 1965 in Malta!

And so the CAA was launched. In those euphoric days, some envisaged an idealised professional world with freedom for architects to practise anywhere in the Commonwealth - universal registration! In this regard, astonishment was expressed when we had to point out that in Canada each of the ten provinces was autonomous, with its own conditions of professional registration; a Canadian, therefore, did not have, and still does not have, complete freedom to practise anywhere in Canada.

The RIBA’s universal influence, through its policy of the recognition of schools of architecture, and its examination system which established high standards and provided a means of entry to the profession in most Commonwealth countries, was envied, especially by emerging regional groups with powerful national aspirations. The slow pace of change as the old Empire merged into the Commonwealth, was irksome to those who wished to throw off the cloak of colonialism, and the century-old traditions and paternal character of the RIBA seemed anachronistic in a world where new nations were born overnight (Between 1945 when it was founded, and 1986 membership in the United Nations increased from 50 to 159, and of these 6 and 27 respectively were Commonwealth countries). The recognition of such undercurrents is essential if we are to understand something of the stresses and strains that inevitably accompany imaginative international proposals which sometimes cut across traditional, cultural and professional boundaries.

Administration -The Secretariat Seen from the viewpoint of Africa, Asia and even the Americas and Oceania, the RIBA seemed to exercise a disproportionate

influence over CAA affairs. For example, the exacting position of Secretary (in a Secretariat starved of funds almost to the point of extinction) has been filled by dedicated men educated in Britain, but with some considerable experience overseas. All, however, have been recognisably part of the establishment; all were, to use a convenient overseas expression, ‘Anglos’ (i.e. white, usually with war-service experience). This, it can be argued, was not unreasonable at the beginning because continuity, a knowledge of professional problems at home and abroad, good personal contacts, access to sources of information and infinite patience, are essential to the successful running of the operation.

The Secretariat was set up originally at the RIBA and, after several moves over the years to other premises, in an attempt to allay criticism of dependence on the Royal Institute, but to reduce costs, it returned to 66 Portland Place in 1988 -a sensible decision, if only on the grounds of accessibility to overseas visitors of which there are many. However, we have discussed from time to time the practicality of relocating the Secretariat in one of our other regions. The effects of such a radical move are impossible to determine, and no one yet has had the courage to take action. Situations change, of course, but at the present time the U.K. is still a desirable location; the country is politically stable and is the gateway to Europe: London has immense cultural and economic resources, it is an important communications centre and has available the unparalleled professional expertise of the RIBA. But the development of electronic media, and the ambitions of the next generation of architects, may make a move feasible and desirable in the not-too-distant future.

The Presidency

We have a gentleman’s agreement that the Presidency of the CAA will circulate among the five regions of the Commonwealth -Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe, and Oceania. Incidentally, “’The Americas” is really a misnomer: it includes Canada and the Caribbean, Guyana, and Bermuda, but not the U.SA -although some overtures have been made to encourage participation by the American Institute of Architects, probably through a new kind of Associate

Membership. By giving each region, in turn, an opportunity to elect the President, one could be accused of discrimination, yet sometimes problems arise over nomination. It is the responsibility of the region involved to present to the triennial CAA Assembly the name of its nominee, who is then normally voted into office.

The position of President is also exacting: among other things he is expected to be an architect of high standing, experienced in international affairs; a diplomatist; and a strong administrator - perhaps most important of all, he should have a good sense of humour. The world is indeed his parish, and it is hoped that our Presidents will visit each of our regions, but the cost, in time and money, is high. Many of the President’s expenses must be underwritten personally, or by his firm, usually with the support of long-suffering partners, the faceless ones to whom the CAA owes a considerable debt of gratitude. In fact, a President’s expenses preclude all but the successful professional from holding office. In the educational field

our professional institutes, universities, technical colleges, and national granting agencies (CIDA in Canada. for example) have sometimes come to the aid of our council and board members, but their contribution fluctuates and is relatively small.

do not believe it is generally known that since its inception the CAA has paid, only on request, minimal transportation expenses to the President, Secretary, Board and Council member, plus GBP5 (about US $10) per day for all other expenses, such as hotel, food and taxis! Those of us who have worked for the CAA therefore, have contributed far more than time and energy to the cause. We really are a charitable organisation. And then, of course, there are the interminable and inescapable head¬quarters’ costs -rent, salaries, telephones, stationery, etc. Whether we like it or not, more generous funding is essential to the proper functioning of the CAA whose income is so uncertain. Perhaps this little book could be used to attract grants, major donations, and bequests.

The following quotation from the designer helps to explain how such a unique and meaningful symbol was achieved:

“Medals are my favourite form of expression. They are like short poems. When I make a medal, I first hold the clay in my palm, where it nestles comfortably. always hope that one day the medal will rest in another palm and give it the same joy that it gave me to create it.”

de PederyHunt

In the 1950s the RIBA gave a very handsome gold presidential medal to the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada. In the late 1970s the RAIC College of Fellows agreed, as a gesture of goodwill, to provide a similar Presidential medal to the CAA and there was to be a competition for the design open to students from all the Canadian Schools of Architecture. Only three designs were submitted; none was considered suitable by the jury, and the students were paid off!

Subsequently, the commission was given to a well-known designer, Dora de PederyHunt of Toronto. She was asked to produce something suitable for all countries with no specific symbols which would relate to any particular country- i.e. no African elephants, Indian tigers, Canadian beavers, Australian kangaroos, etc. The final medallion, gold on a red and white ribbon, depicted a mature

tree of life whose roots represent the five member regions of the CAA; the strong trunk speaks of the members’ institutes gathered together to advance the cause of architecture; and the branches represent continuing growth of the membership, striving for continual improvement in their chosen profession.

The first medal was presented to President Ronald Gilling at a ceremony in the RIBA headquarters building in London. Identical medals in silver on a blue silk ribbon are presented to past Presidents for them to keep, while the original gold medal is passed on to each President in turn, to be worn while in office. The Council decided to present a silver medal to Lady Matthew in recognition of the late Sir Robert’s outstanding contribution to the CAA, and to Jai Bhalla as a former CAA President.

The Commonwealth Association of Architects had its origin in a meeting of representatives of Commonwealth architectural institutes and societies in London in 1963 when it appeared that the time had come for a closer and more explicit form of association than periodic conferences on an informal basis. By early 1964 nearly all societies represented at the conference had ratified its recommendations and the Commonwealth Association of Architects came into being. It is therefore just over one year old. Twenty-three societies constitute its membership and it virtually covers all Commonwealth countries where an established and recognised Society of Architects exists. Its objectives are to be found more precisely expressed in its constitution but the scope of its interests will be apparent in the various articles and notes below.

the International Union of Architects and the Commonwealth Association of Architects. The International Union of Architects has national sections and its Congress is primarily a meeting of individual architects. We are an association of institutes all very similar in outlook and habits and on this existing commonality of outlook, practical collaboration and joint action can be built in a way which is not readily achieved on a worldwide basis. Above all I think we can help in education. On another plane the richer parts of the world acknowledge an obligation to the poorer and if only to this end the Commonwealth Association of Architects can be an effective agency for already associated Governments and nations to give and receive aid.

The idea of publishing this handbook came from the Steering Committee when they met in Singapore in September 1964. We thought a handbook of this kind, being ready for the full Conference to be held in Malta in 1965, would first of all be a service to members as a straight reference book of information which has not so far been brought together in one document. The handbook could also be a mark of our sense of identity and purpose.

As President of the International Union of Architects I am perhaps prone to fall into pontifications on architecture’s international quality and mission. But it bears repeating that we are pre-eminently an international profession which, from the earliest days, has pursued and gained knowledge outside the borders of our own countries. For nearly a century there has been a free and vigorous movement of architects within the Commonwealth.

The basic organisation of the profession in our countries and our educational systems show a similarity having its origin in common cultural, educational and professional values. The Commonwealth Association of Architects is therefore able to give expression to the impulse to act internationally in communities which share the same values and are familiar. For this reason I think there is ample room for both

should like to stress the importance of mutual support in professional matters and the sustaining of professional codes which is one of our objectives. It is not easy in new countries to build up a healthy and accepted professional status. The authorities may not understand it; the background of economic and material factors in the building industry, the client’s attitude, and a very thin spread of architects on the ground may make it very difficult. But we should, I am convinced, not let expediency or material difficulties stand in the way of the architect taking up his classical status in relation to the client, the contractor, his colleagues, and societies at large.

Changes in the kind of client we get, new ideas on contract relationships, the demands of highly sophisticated preplanning techniques and other technical developments may be blurring the precise nature of the professional function. I am not myself sure where orthodoxy lies, but I have always been struck by the uniformity in the essentials of professional codes in many parts of the world and among Commonwealth institutes. Collaboration in asserting our beliefs and mutual support in securing their acceptance can be a very important part of the Association’s work. Finally, this is a place to acknowledge the generosity of the publishers of The Builder who have backed and organised this handbook and made possible its distribution to some 12,000 architects in distant parts of the world.

This article originally appeared as a foreword in the Handbook for the Commonwealth in 1965 published by The Builder for ‘Commonwealth Association of Architects

There have been several CAA publications. Snapshots of what their covers looked like are portrayed on 3 pages, showing what literary efforts have been put into documenting thoughts and ideas that the association has deemed important to its membership over this journey in time. However, the very first of these works is the CAA handbook.

But it was not until about twenty-five years ago that the idea of publishing a formal history of the CAA was firmly mooted by the Executive in September1988 when a Jubilee publication was needed for the Assembly in Kuala Lumpur, in September, 1989. It was agreed, therefore, that Past Presidents, Secretaries and others should be invited to submit

papers of their impressions, experiences and achievements during their term of office. It was thought that such individual contributions would be of special interest to readers both now and in the future.

The CAA once again commenced publishing an E-Journal from 2015 which is electronically transmitted across the globe to reach over 40,000 architects.

This Golden Jubilee book being the most recent publication of CAA, portrays the 50 years of the CAA and its influence on architecture of the Commonwealth. The book was an idea by the Council of CAA in 2013 and its actual production supported by Architectural Association of Kenya.

www.comarchitect.org/view-e-journal-of-caa/

The first Conference of the Commonwealth Association of Architects was held in Malta in 1965. It is instructive to note that some of the resolutions arising from the report on the purposes and achievements of the conference, are as relevant now as they were then. In this section, we sample some of them in the hope that in reading them members of the CAA will be stirred by the vision of the founding fathers and will stoke the dying embers of those noble goals and invent new strategies to address what remains unattained to

The architect, by his training, should be knowledgeable in the arts, humanities and social sciences as they affect structures and environment; and have the technical skills to direct the creation of buildings and groups of buildings. He should have sufficient knowledge of the specialist techniques related to architecture and planning to enable him to integrate these into designs that satisfy the requirements of his client and of society, functionally, economically and aesthetically.

The Conference set itself the aim of making substantial progress in the next few years towards achieving inter-recognition of architectural qualifications. The aim of the Association in promoting inter-recognition is to raise standards where necessary, to give the member societies in those countries a target to aim at, and to foster freer movement of architects from one country to another, and even within the same country.

A major step in the realisation of these aims would be the establishment of academic standards which could be recognised by all member societies and, in turn, by their registration authorities.

The Conference believed that twinning arrangements between schools in developed and developing countries should be encouraged to the fullest possible extent. It emphasised that twinning is a contractual agreement between schools on the basis of friendly collaboration and cultural exchange, which may include the provision and exchange of teachers and students.

The benefits do not necessarily accrue to one partner only. These agreements, made directly between schools, would not generally be the direct concern of member societies or of the Commonwealth Architects’Association, but the Association should be kept informed of links that are being formed and act as a channel of approach to assist schools which wish to enter into twinning arrangements. The

Association should circulate member societies with information about links that are formed.

Member Societies were advised that they should also try to recruit the best type of entrant to the profession by meeting parents, career advisers and pupils in secondary schools so as to explain the value and nature of the architectural career. Ignorance about it was widespread and action on these lines had paid handsomely in certain countries.

The Conference laid stress on the importance of all architects having a basic education in urban design and landscape architecture. These should be an integral part of the course to enable them to design buildings in their context, and to contribute as architects to the work of design teams in urban and rural areas. They should also have the opportunity for subsequent specialised study in postgraduate courses in urban design and landscape architecture.

Many countries were beginning to develop courses which provided for some joint training with other members of the building team. The examples of Ghana, Hong Kong, East Africa and Malta were cited. The pattern of the courses varied, but they often provided a common first year for architects, builders, building technologists and quantity surveyors.

Integration of education with engineers had not advanced so far, because it was more difficult to establish common ground. The common first year should be distinguished from the preliminary first year required to bring students up to matriculation standard. It was agreed that these developments were highly desirable and should be encouraged.

The Association should be asked to obtain and circulate information about these developments to member societies.

Indigenous traditions and methods should be respected in courses of architectural education.

Professor Sir Robert Matthew, CBE, ARSA, PPRIBA, Chairman of Steering Committee, President.

T. C. Colchester, CMG, Secretary.

Australia

Mr Gavin Walkley, FRAIA, FRIBA, MTPI, President, Royal Australian Institute of Architects, Delegate.

Mr Max Collard, PRAIA, FRIBA, Past President, Member of Steering Committee.

Canada

Professor T. Howarth, FRIBA, FRAIC, Delegate, Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, University of Toronto.

Mr J. Lovatt Davies, PRAIC, ARIBA, Member, Steering Committee.

Ceylon

Mr J. C. Nilgiria, FRIBA, Member of Executive Council, Ceylon Institute of Architects, Delegate.

East Africa

Mr S. C. Lock, ARIBA, AMTPI, Chairman, Education Committee, East African Institute of Architects, Delegate.

Ghana

Mr P. Turkson, ARIBA, AMPTI, Ghana Society and Institute of Architects, Delegate.

Hong Kong

Professor W. G. Gregory, ARIBA, Hong Kong Society of Architects, University of Hong Kong, Delegate.

India

Mr J. R. Bhalla, FRIIA, FRIBA, Vice~President, Indian Institute of Architects, Delegate.

Jamaica

Mr Donald Brown, ARIBA, Secretary, Jamaica Society of Architects, Delegate.

Ireland

Mr Pearse Mackenna, PRIAI, FRIBA, President, Royal Institute of Architects of Ireland, Delegate.

Mr W. A. Cantwell, FRIAI, FRIBA, VicePresident, Observer.

Malaya

Mr Hisham Albakri, ARIBA, Vice-President, Federation of Malaya Society of Architects, Delegate.

Malta

Mr R. Degiorgio, FRIBA, BE & A, President, Malta Chamber of Architects and Civil Engineers, Delegate.

Mr J. Cachia Fearne, B.SC, BE & A, Observer.

New Zealand

Graham Dawson President, New Zealand Institute of Architects

Nigeria

Mr M. O. Onafwokan, ARIBA, MTPI, President, Nigerian Institute of Architects.

Mr Oluwole Olumiyiwa, ARIBA, Hon. General Secretary. Mr Augustine Egbor, ARIBA, Public Relations Officer.

Mr Adedokun Adeyemi, ARIBA, Council Member.

Mr E. O. Adeolu, ARIBA, Ahmedu Bello University, Observer.

Mr F. N. Mbanefo, ARIBA, Member, Steering Committee.

Pakistan

Mr Zahirud Deen, ARIBA, Vice-President, Institute of Architects, Pakistan, Delegate.

Rhodesia

Mr R. C. Brown, ARIBA, President, Rhodesian Institute of Architects, Delegate.

Singapore

Mr Lim Chong Keat, ARIBA, Vice-President, Singapore Institute of Architects, Member of Steering Committee.

South Africa

Dr D. M. Calderwood, MIA, ARIBA, AMTPI, President, South African Institute of Architects, Delegate.

Mr M. D. Ringrose, MIA, Observer.

United Kingdom

Sir Donald Gibson, CBE, PRIBA, President, Royal Institute of British Architects, Delegate. Prof. Arthur Ling, FRIBA, MTPI, Steering Committee Member.

Mr L. Hugh Wilson, OBE, FRIBA, MTPI, Chairman, Board of Architectural Education, Observer.

Mr Alister MacDonald, FRIBA, Observer.

Mr Wilfrid Woodhouse, FRIBA, Observer.

Mr G. R. Ricketts, Secretary, RIBA.

Mrs Elizabeth Layton, Under-Secretary, RIB A.

Mr Malcolm MacEwen, Under-Secretary, RIBA.

Miss K. E. Hall, Administrative Assistant, RIBA.

Trinidad and Tobago

Mr Alfie Franco, ARIBA, Trinidad and Tobago Society of Architects, Delegate.

1st GA and Conference Valletta - Malta

4th GA and Conference Canberra - Australia

and Conference Lagos - Nigeria

and Conference Nairobi - Kenya

GA and Conference Sydney - Australia

GA and Conference Ocho Rios - Jamaica

GA and Conference Nicosia - Cyprus

GA and Conference Wellington - New Zealand

19th GA and Conference Colombo - Sri Lanka

and Conference Brighton - UK

GA and Conference Kuala Lampur - Malasia

and Conference Mauritius - Grande Baie

GA and Conference Bloemfontein - South Africa

GA and Conference Melbourn, Australia

and Conference Dhaka - Bangladesh

1965 - 1967

Sir Robert Matthew CBE

United Kingdom

1971 - 1973

Jai Rattan Bhalla

India

1979 - 1982

Frederic Rounthwaite

Canada

1987 - 1989

Dato I. Hisham Albakri

Malaysia

1994 - 1997

Rusi Khambatta

India

2003 - 2007

Llewellyn van Wyk

South Africa

2013 - 2016

Rukshan Widyalankara

Sri Lanka

1967 - 1969

Sir Robert Matthew CBE

United Kingdom

1973 - 1976

Ronald Andrew Gilling OBE

Australia

1982 - 1985

Peter Johnson

Australia

1989 - 1991

Wale Odeleye

Nigeria

1997 - 2000

George Henderson

United Kingdom

2007 - 2010

Gordon Holden

New Zealand

1969 - 1971

Jai Rattan Bhalla

India

1976 - 1979

Oluwole Olusegun Olumuyiwa

Nigeria

1985 - 1987

John Wells-Thorpe

United Kingdom

1991 - 1994

David Jackson AO

Australia

2000 - 2003

Phillip Kungu

Kenya

2010 - 2013

Mubasshar Hussain

Bangladesh

President 1991 - 1994

My presidency began when Chief Dr. Wale Odeleye of Nigeria gave me the reins in Cyprus and ended with my handover to Rusi Khambatta of India in Mauritius.Some significant events that I remember marking my presidency: Hong Kong was returned to China with the potential of CAA losing a highly valued member. CAA resolved that countries that ceased to be Commonwealth members could if they wished continue with their CAA membership. This, the Hong Kong Institute of Architects did and has remained an active member ever since. This happened at a time when the Chinese profession was increasing its reach for exchange and contact with the rest of the world. Over the years, CAA has been represented in China on accreditation visits to its top schools. The phrase “Ecologically Sustainable Design’ entered the CAA lexicon for the first time when speakers covering building and landscape provided by CAA addressed ESD at a conference in Colombo. The phrase has morphed many times since then and probably is now simplified to Low Energy Design.

Institutes around the Commonwealth had very few people and Councils in their management who understood the value and benefits of the CAA. This was so, especially in the larger institutes of developed countries where membership of CAA was actually the most beneficial. It tended to be thought of as “old hat” like the Empire and contributions were low priority and the first to be cut on budget day.

Occasionally, CAA’s financial struggle, and generally in the countries where the profession was not able to get itself together to pay its dues, could be depressing, but the joy of meeting excited architects from every corner of the world because they had made it to their own international conference was deep. With this hindsight, it would be nice to do the job again but better.

President 1994 - 1997

When I was first confronted with the diverse nations of the Commonwealth, the uppermost thought was to bring forth a unity of ideas. The wide differences amongst the nations of the Commonwealth were a fact to be reckoned - with countries spanning from Australia in the East, to South Africa in the South, to Jamaica in the West. My experience with ARCASIA was similar; the only difference being that it was a group with Asian homogeneity. All the same, a common goal to enhance architecture was translated through exchange of education, practice and information, an interaction bearing in mind prevalent tradition, culture and technology rooted within the country. These basic principles being understood, it established a cordial relationship in spite of diverse conditions. The fact that we were all architects made it easier.

A constant worry in CAA is finance and this becomes a challenge for a number of countriesto afford affiliation. There is no doubt, that Institutes have realised the worth of relationship with CAA. It may be necessary to review the scale of subscriptions making it possible for a wider participation of Member Organizations in the Commonwealth.

Practice standards of developed countries are unacceptable in developing countries and vice-versa. Conferences have helped to sort out these differences, resulting in wider acceptability. CAA is in a better position as a viable vehicle to bring diverse parties across the globe to one podium in addressing some of the burning issues faced by mankind.

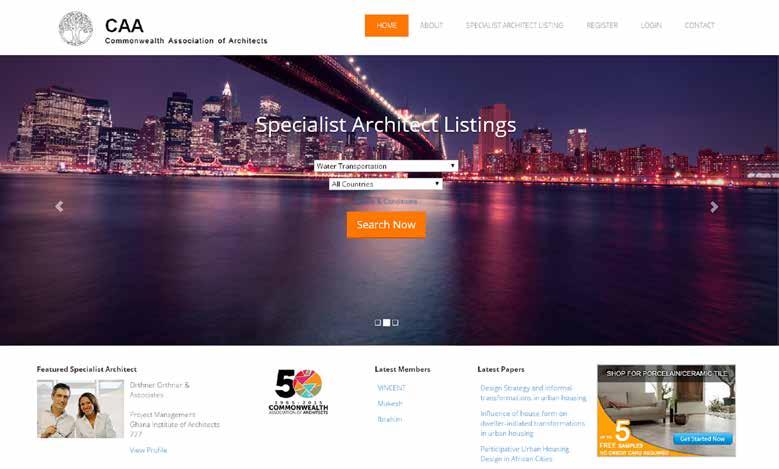

Web Portal listing Architects & Firms of CAA countries to facilitate networking and Joint Venture

The Commonwealth of Nations is poised for greater development activities in the decades to come. Global attention is focused towards its member countries, which will make them most sought after in terms of development and investments.

The Commonwealth over the years has been producing works of architecture and many of these have received worldwide acclaim. There is enormous potential, and the expertise of individual architects and firms belonging to CAA countries can be matched with what obtains in the developed world. These specialists have produced landmark buildings and projects of significant magnitude in their respective countries, through which their economies have benefited tremendously. However, the expertise gained through these projects has been limited only to the country in which it has been tested and applied, and the knowledge base has not been available to other counterpart architects to use. Technology transfer has not taken place and appreciation of these projects is only partly possible through the single media of written content in magazines and journals, although in a few instances there have been joint ventures, mostly through ad-hoc arrangements.

This issue has been addressed by the CAA Council, and with the assistance of professional bodies of member countries,the CAA has established a web portal listing of architects and firms as ‘trusted and inspiring specialists’. The listed specialists will have the capability, knowledge, experience and resources in terms of projects enabling other architects from member countries to select suitable firms/ practices depending on the project requirements for joint ventures. The list is named ‘CAA List of Specialist Architects’.

The listing of specialists will be limited to members of CAA countries while project categories will include, but not be limited to, Land Transportation & Traffic, Airports, Water Transportation, Healthcare, Electricity Generation, Leisure & Hotels, Mass Housing Technology, Specialized Commercial Establishments, Inclusive Environments, Landscape Architecture, Interiors and Architectural Education. The listing is a valuable repository of projects information in the Commonwealth for architects and prospective clients to refer to. The Web Portal was launched at the General Assembly of CAA on 18th June 2015 at 66, Portland Place, London RIBA marking the Golden Jubilee of the Association.

The Commonwealth is an association of sovereign nations which support each other and work together towards international goals. It is also a ‘family’ of peoples. With their common heritage in language, culture, law, education and democratic traditions, among other things, Commonwealth countries are able to work together in an atmosphere of greater trust and understanding than generally prevails among nations. The Commonwealth has no formal constitutional structure; it works from understood procedures, traditions and periodic statements of belief or commitment to action. Intergovernmental consultation is its main source of direction, enabling member governments to collaborate to influence world events, and setting up programmes carried out bilaterally or by the Commonwealth Secretariat, the association’s main executive agency.

The Commonwealth has established a framework for two broad pillars — Democracy and Development — upon which eight programmes are structured. These are Good Offices for Peace, Democracy and Consensus-Building, Rule of Law, Human Rights, Public Sector Development, Economic Development, Environmentally Sustainable Development and Human Development.

Environmentally sustainable development has been a prime concern of the Commonwealth Secretariat for more than 20 years. In 1989 Commonwealth Heads of Government agreed on the Langkawi Declaration on the Environment. The leaders recognised that development which destroyed the natural resource base and jeopardised future development was not really development at all. Importantly, they recognised that the environment is a global resource which required global responses ‘… our shared environment binds all countries to a common future’. In recent years this observation has

been brought into sharp focus by the growing consensus on the global threats posed by climate change. Drawing on Commonwealth principles, it also advocates the reform of international institutions to support more holistic and sustainable approaches to development.

The modern Commonwealth was established in 1949 as an association of free and equal sovereign states which had been part of the British Empire but were now independent and, in the case of India and Pakistan, on the verge of then becoming Republics. There are now 53 member states, with a combined population of 2.2 billion (approximately 30% of world population). Rwanda, the newest member joined in 2009, despite having no direct link to Britain.

The modern Commonwealth is a network of networks. Its members constitute more than 25 per cent of the membership of the United Nations, nearly 40 per cent of the World Trade Organisation, just under 40 per cent of the African Union, 90 percent of the Pacific Islands Forum, and 20 per cent of the Organisation of Islamic countries. In addition, five Commonwealth states are members of the G20, while Commonwealth countries are influential members of the European Union and the North American Free Trade Association. A few in the Commonwealth are some of the world’s fastest developing economies, and the relationship has allowed the technologically advanced markets to spread throughout the globe to new countries. More than $3 billion dollars of global trade takes place every year within the Commonwealth, and its combined GDP doubled from 1990 to 2000, and is forecast to grow by 15 per cent again by 2015. Affiliated to the Commonwealth as an officially recognized Pan Commonwealth professional Association, the CAA was formed in 1965 and is based in the UK as a Registered Charity.

The CAA is a membership organisation for institutes representing architects in Commonwealth countries.

Established to promote cooperation for ‘the advancement of architecture in the Commonwealth’ and particularly to share and increase architectural knowledge, it currently has 39 members spread over 5 regions namely Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe, and Oceania. As a UK-registered charity, the CAA is governed by a General Assembly of Member Organizations which meets at least once every three years.

A Council comprising The President, Immediate Past President, Honorary

Secretary/Treasurer, 5 regional Vice Presidents, Chairs of Communication, Education and Practice Committees manages the Association. The Trustees are responsible for ensuring that the Charity complies with the requirements of the UK Charity Commission in particular and that activities remain within constitutional mandate.

The Trustees also make an annual report including independently examined accounts to the Charity Commission. The Association is known for its procedures for the validation of courses in architecture which convene multilateral visiting boards to visit schools to assess courses against set criteria.

Widyalankara (Sri Lanka) - President CAA BSc (B.E.), MSc (Arch.), FIA (S.L)

Hussain (Bangladesh) - Immediate Past President

Mansur Kurfi Ahmadu (Nigeria) - Chair of Education B.Sc (Arch),M.Sc.(Arch) .,Dip. (Plan),M.Sc. (PM).FNIA

Sithabile Mathe (Botswana) - Vice President Africa B.Arch (Hons) GU; Dip. Arch (PG) GSA, MNAL, MAAB, MBIDP

Jayantha Perera (Sri Lanka) - Chair of Communication BSc (BE), MSc (Arch), FIA (SL)

Kalim A. Siddiqui (Pakistan) - Vice President Asia, B.Arch., M.Sc. Planning, PCATP, FIAP, FIPP

John Sinclair (New Zealand) Vice President Oceania Alternate. Dip.Arch (Auckland), pp NZIA

Vincent Cassar (Malta) - Senior Vice President B.Arch., FIHEEM, FICE, C. Eng., A&CE

Steven Oundo (Kenya) - Chair of Practice B. Arch (Hons) UoN, MBA (Stra Mgmt) UoN, MAAK (A), MAAK (CPM), ACIArb.

Wycliffe Morton (St. Kitts & Navis) - Vice President, Americas, B.Sc (Arch), B.S.L.A., B.Arch, MLA, SKNIA, FCAA

Jalal Ahmed (Bangladesh) Vice President Asia Alternate, B.Arch, FIAB

John Geeson (UK) Secretary/Honorary Treasurer, Trustee, BA Hons, Dip Arch (Leics) RIBA AoU

Christos Panayiotides (Cyprus)- Vice President, Europe MSc. (Arch), MSc. B.Sc (Hons) Arch, Dipl Arch (Hons)

David Parken (Australia) Vice PresidentOceania, B.Arch (Adel), LFRAIA, Hon AIA, Hon FNZIA, Hon RAIC

Annette Fisher (United Kingdom) Vice-President Europe Alternate, Trustee, BSc BArch, RIBA, MNIA

Rukshan Widyalankara is the Principal Director and Chairman of RWPL, a practice involved in many buildings of note, and has received numerous awards of excellence for both academic and professional work. A distinguished alumni of the University of Moratuwa, from which he holds a bachelors and a masters degree in architecture, Rukshan has been an active member of the Sri Lanka Institute of Architects (SLIA) and later went on to become its youngest President in 2005. He was the Chairman of the Architects Registration Board in 2007 and has also represented Sri Lanka at many international forums such as UIA, ARCASIA, and SAARCH.

Rukshan is a recipient of numerous academic awards of excellence including The Young Architect of the Year Award by SLIA in 2003. Complementary to the practice of his discipline of architecture, he has devoted his professional life to the advocacy, debate and canvassing of a wide range of relevant issues. His dedication to work for the common good and willingness to undertake responsibility equip him uniquely for the leadership positions he has continually attained.

Mubasshar Hussain, served as the Vice President for Asia region in the CAA and was elected as Senior Vice President of CAA in Melbourne in 2007 and President in 2010 in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Hussain is also a Past Chairman of ARCASIA. Prior to this, he served in various capacities in the Executive Committee of Institute of Architects Bangladesh (IAB) and was elected as its President in 2003-04, 2007-08 and again in 2009-2010.

He is the founder Managing Director of Assoconsult Ltd, a large and a respected practice in Bangladesh. He is a visiting faculty member of the Ahsanullah University of Science & Technology, Dhaka. In recognition to his service and contribution to the architectural profession, American Institute of Architects (AIA) conferred on him the AIA President Medal and Honorary Membership in 2009.

Mansur worked briefly with the then Kaduna State Ministry of Works and Housing before proceeding for his M.Sc. (Arch.) at Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. Mansur joined the Central Area Urban Design Team for Nigeria’s new Capital City, Abuja under Kenzo Tange and Urtec of Japan who were the team leaders. This afforded him the opportunity of working for six months in Tange’s office in Tokyo, Japan. During 1981 and 1982, he took leave of absence to study for a Graduate Diploma in Urban Planning at Architectural Association School in London. Mansur undertook a course at Reading University, U.K. gaining an M.Sc. in Project Management.

Mansur was made a Fellow of the Nigerian Institute of Architects (FNIA) in 1993, where he has served at various times as Chair of International Affairs, Chair of Education (Responsible for Validation, Professional Examinations and Seminars) and Director of African Union of Architects Congress that was held in Nigeria. He has been a Council Member of the Architects Registration Council of Nigeria since 1990. He has been a Council Member and Chair of Education at the CAA since 2007.

Jayantha first attended the CAA General Assembly in Melbourne, Australia in 2007 as President of the Sri Lanka Institute of Architects (SLIA). Jayantha has served as Dep uty Chairman ARCASIA Zone A for the period 2009-2010 and is a Past Chairman of SAARCH (South Asian Association for Regional Corporation of Architects). He was also the Chairman of the Architects Registration Board Sri Lanka. In 2007 as President of SLIA, he was instrumental in hosting ARCASIA in Sri Lanka to coincide with the Golden Jubilee Celebration of the Sri Lanka Institute of Architects. Jayantha currently serves as the Director for the UIA (Union of International Architects) work programme – Responsible Architecture. During the post Tsunami period in Sri Lanka Jayantha served as the chairman of the AFSTV (Architects fund to Shelter Tsunami Victims) a fund raising initiative to build houses for the Tsunami victims in Sri Lanka. Two projects were successfully completed in the south and east of Sri Lanka.

Currently Jayantha is a Faculty Board member of the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Moratuwa Sri Lanka and a Member of the Board of Directors of the City School of Architecture (Colombo) Ltd.

B.Arch., FIHEEM, FICE, C. Eng., A&CE

Vincent Cassar, a graduate in Architecture and Civil Engineering from the University of Malta, joined the Public Service in 1973.

Since then he has worked within the Public Works organization and was responsible for various projects including those for housing, healthcare and hospitals, and other major projects of a civil engineering nature such as roads, marine works, sewerage and waste management.

In April 2003 he was appointed as the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry for Youth and the Arts. With the establishment of the Ministry for Urban Development and Roads, responsible for urban development and land transport issues in February 2004 he assumed the responsibility for that Ministry as its Permanent Secretary. Vincent was appointed as Chairman of the Malta Environment and Planning Authority, a post he still occupies. He is a Fellow of the Institute of Civil Engineers (FICE) and a Fellow of the Institute of Health Estate Engineering Management (FIHEEM). He also served as the President of the Kamra tal-Periti and is its National Delegate to the Architects’ Council of Europe (ACE) and the European Council of Civil Engineers (ECCE).

Steven Oundo graduated from the University of Nairobi with a Bachelor of Architecture (Hons) Degree in 1997 and a Master in Business Administration (Strategic Management) Degree from the same University in 2014. He is the immediate past Chairman of the Architectural Association of Kenya (AAK) and has also been the chairman of the newly constituted National Construction Authority since 2012. He also served as Treasurer and 2nd Vice President of the East Africa Institute of Architects (EAIA) from 2006 to 2011. He has also served in a number of international professional organizations including the Africa Union of Architects (AUA) where he currently serves as Treasurer as from 2011 and has been the Chairman of the Association of Professional Societies in East Africa (APSEA) since 2013. He is also a partner and architect for Trioscape Planning Services Ltd.

He is an Associate Member of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators (Kenya Branch). Steven was awarded the Order of the Grand Warrior (OGW) by the President of the Republic of Kenya for distinguished service to the nation.

CAA Structure: Council Members

Sithabile received her architectural education from the Mackintosh School of Architecture, Glasgow, Scotland. She completed her Post Graduate Diploma in Architecture at Glasgow School of Art and in 1999 and received the Glasgow School of Art Representative to Scottish Woman of the Year Award. On graduating, she moved to Norway to work for HRTB Architects. In 2006, she returned to Botswana and established her own practice Moralo Designs (Pty) Ltd in Gaborone. She has also been involved in a feasibility study for the John Garang Memorial University Hospital in Juba, Sudan and has designed a diamond polishing factory located in the new Diamond Hub of Botswana.

Sithabile has served on the Architects Association of Botswana Executive Committee for several terms and now sits as a Council Member of the Architect’s Registration Council of Botswana. She has lectured at the University of Botswana Architecture Program and since leaving the University to date, she has been vice-Chair of the Accreditation Advisory Committee for the Architecture Program. She is a member of the Architects Association of Botswana, Botswana Institute of Development Professionals, and the Norwegian Association of Architects.

Wycliffe Morton (St. Kitts &

Wycliffe is a built environment architect as well as a landscape architect in his own private practice since 1997.

He received his initial training in a design/build architectural firm in St. Kitts and completed the study of both architecture and landscape architecture to professional degree level at City College of New York, CUNY. He then proceeded on scholarship to complete his Master in Landscape Architecture at Pennsylvania State University specializing in Caribbean Terrestrial Ecotourism facility development. He has been an external examiner for City and Guilds, and later a part-time instructor in the Associates Certificate program in Architectural Technology at the national Clarence Fitzroy Bryant College where he was retained as a full-time lecturer. He participated in local hurricane emergency response efforts regularly, which further reinforces the connection to the environment and the need for responsible design, construction and consumption methods. The furtherance of the profession and its leading role in the built environment and response to climatic and societal needs is paramount in both practice and instruction.

Kalim A. Siddiqui (Pakistan)

Vice President - Asia

B.Arch., M.Sc. Planning, PCATP, FIAP, FIPP

Christos Panayiotides (Cyprus)

Vice President - Europe

MSc. (Arch), MSc. B.Sc (Hons) Arch, Dipl Arch (Hons)

alim A. Siddiqui holds a Masters degree from Asian Institute of Technology (A.I.T.) Bangkok in Human Settlements Planning and Development along with a Bachelor of Architecture degree. Kalim carries with him a wealth of experience in project design & preparation, planning, monitoring and control acquired over the past more than thirty years in professional practice.

He was involved in the affairs of the Institute of Architects Pakistan and has held various positions as Office Bearer of the Institute over a period of more than 25 years.

At the National level he was twice elected Vice Chairman, Pakistan Council of Architects and Town Planners (PCATP).

At the International level, he has been involved with the activities and various programs of the Architects Regional Council Asia (ARCASIA) and served as its Vice President (20102012) representing Zone “A” countries comprising Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Nepal. He is a Fellow of the Institute of Architects, Pakistan (FIAP) and Fellow of the Institute of Town Planners, Pakistan, (FITP) and is registered with Pakistan Council of Architects and Town Planners (PCATP).

Christos P. Panayiotides completed his Degree studies (BSc (Hons) Arch) and Diploma course in Architecture (Dipl Arch (Hons)) at the North London Polytechnic, now the London Metropolitan University, in 1981. He worked for the London Borough of Enfield and The Ronald Fielding Partnership in London and was elected a corporate member of the RIBA and registered as an architect in U.K. in 1983. He was the principal architect and project liaison officer in the extension of the Dhekelia Primary School, designed and constructed in 13 weeks, to facilitate the arrival of a new regiment in 1992. For his services, Christos was awarded a Certificate for High Achievement in Design, by PSA International. In 1993 he established his own architectural practice “Christos Panayiotides Associates” in Nicosia, Cyprus.