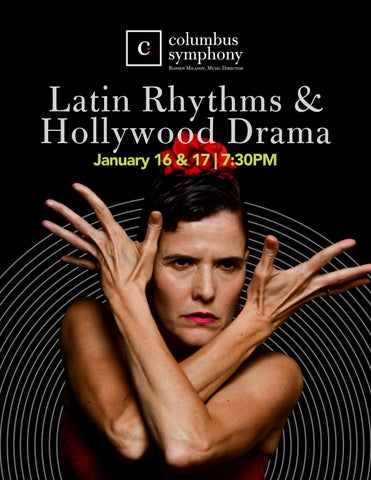

Latin Rhythms & Hollywood Drama

January 16 & 17 | 7:30PM

Masterworks 4

Symphony No. 1 (“Classical”) in D major, Op. 25 (1917)

by Sergei Prokofiev (Sontsovka, Ukraine, 1891 - Nikolina Gora, nr. Moscow, 1953)

With his first two piano concertos and the Scythian Suite, the young Prokofiev established a reputation, in the 1910s, as the enfant terrible of Russian music, shocking critics and audiences with his highly unconventional harmonies and rhythms His early works seemed to be all about defying authority He rebelled against his teachers (Glazunov and Liadov) at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, but his music also reflected the general intellectual unrest of the war years that led to the 1917 revolutions (the overthrow of the Czar in February and the Bolshevik coup in October). Yet in one of his first works written during the year of the revolutions, Prokofiev went out of his way to appear non-revolutionary. He conceived his first symphony within the harmonic and structural world of Haydn’s symphonies–or so it may seem at first sight. This return to Classicism, as we may realize with hindsight, was just another contrary move on the part of a young man always intent on doing the unexpected. Nor is that return complete: we are frequently jolted out of our classical dreams by some abrupt change of keys Haydn never would have dreamt of, or some metric irregularity that would have astounded 18th-century musicians.

In his autobiography, Prokofiev wrote:

It seemed to me that had Haydn lived to our day he would have retained his own style while accepting something of the new at the same time. That was the kind of symphony I wanted to write: a symphony in the classical style And when I saw that my idea was beginning to work, I called it the Classical Symphony: in the first place because that was simpler, and secondly, for the fun of it, to “tease the geese, ” and in the secret hope that I would prove to be right if the symphony did turn out to be a piece of classical music.

The first ideas for the symphony date from 1916, when the third-movement “Gavotte” was written. Prokofiev thus replaced the minuet, a constant part of a classical symphony, with a different dance movement that was clearly his favorite. He wrote a Gavotte as early as 1908, later included in his Ten Pieces for Piano, Op. 12. And he included the Gavotte of the Classical Symphony, in somewhat expanded form, in the ballet Romeo and Juliet (1935) The first and second movements were also sketched in 1916, but the bulk of the work was completed during the summer of 1917, in a country house where Prokofiev was sheltered from the turmoil of the political events. The composer had left his piano in the city, having decided for the first time to compose without one. “I believed that the orchestra would sound more natural,” he wrote later, and in fact, he achieved a bright and delicate sonority that his earlier works didn’t have.

Masterworks 4

At 15 minutes’ duration, the “Classical” is the shortest of Prokofiev’s seven symphonies, and even shorter than many by Haydn. The themes are all kept brief and developments are sparse, with the emphasis on shorter, well-rounded, and separate units. The very simplicity of the writing sometimes becomes the source of musical humor. For instance, the first movement’s second theme consists of only two different notes, each of which is repeated two octaves lower–an unusually large leap that saves the melody from becoming banal. The orchestration also adds more than a few comic touches, as in the third movement where, after the middle section, the Gavotte theme returns in sharply reduced scoring, and the theme finally vanishes into thin air, as it were. A more serious tone is introduced in the second-movement “Larghetto,” which anticipates the lyricism of Prokofiev’s Soviet-era works from the 1930s. But the work ends on a cheerful note, with a sparkling finale that is hard to listen to without at least a smile.

Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35 (1937-39, rev. 1945)

by Erich

Wolfgang Korngold (Brünn, Moravia, Austro-Hungarian Monarchy [now Brno, Czech Republic], 1897 - Hollywood, California, 1957)

When Erich Wolfgang Korngold was nine years old, his father who happened to be Julius Korngold, the most influential music critic in Vienna showed the boy’s first compositions to Gustav Mahler, the latter exclaimed: ‟A genius!” Mahler’s reaction was understandable. The young Korngold was a unique composing prodigy who had an instinctive grasp of the most modern musical styles of the day He grew up to be an extremely successful opera composer his most talked-about work, Die tote Stadt (‟The Dead City”), was written when he was twenty. He was equally attracted to operetta, and was considered an expert on Johann Strauss, Jr. His involvement with new productions of Die Fledermaus and other Strauss operettas (as arranger and conductor) became legendary, and brought him into contact with Max Reinhardt (18731943), the foremost German stage director of the time. This turned out to be a life-saver, as it was with Reinhardt that Korngold first went to Hollywood, where he soon became the star among film composers After the Nazi occupation of Austria in 1938, Korngold lost his original home base and settled permanently in Los Angeles.

His father, who in his seventies was forced to flee Austria and joined his son in Southern California, was deeply disappointed that Erich had given up ‟serious” composition in favor of the movies. To his last day, the old man kept exhorting his son to return to concert music His advice went unheeded for years, yet towards the end of Julius’s life, Erich wrote a string quartet (his third) and, after his father’s death, he returned to a project started years earlier but never completed: a concerto for violin and orchestra.

Masterworks 4

The great violinist Bronislaw Huberman an old family friend since Vienna days had long been asking Korngold for a violin concerto. When the work was finally completed, however, Huberman found himself unable to commit to a performance date. (The Polish violinist was in poor health and died in June 1947 at the age of 64). Korngold showed the concerto to Jascha Heifetz, who learned it within a few weeks and, with Huberman’s blessing, gave the world premiere in St. Louis on February 15, 1947.

At this point in Korngold’s career, the two aspects of his creative world concert and film music had become completely intertwined. His movie scores (Captain Blood, The Adventures of Robin Hood) were symphonic, even operatic, in their scope. The Violin Concerto, conversely, owes much to Korngold’s work in the film industry. Many of the major themes were taken over from movie scores, and there are moments where the instrumentation and the thematic development also bring back Hollywood memories.

The opening theme of the concerto comes from a score written for a film that failed and was quickly forgotten (Another Dawn, 1937), the second from the historical movie Juarez (1939). The folk-dance theme of the last movement originated in the film adaptation of Mark Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper (1937), and became the starting point for a set of brilliant variations. These different sources form a completely new entity in the Violin Concerto, quite independent from the screen originals. (The beautiful melody of the second-movement ‟Romance” seems to have been written especially for this concerto.)

In Korngold’s personal style, elements inherited from Mahler and Richard Strauss are treated with the light touch perfected at the Warner Brothers studios. This approach brought Romantic concerto-writing to new life at a time when most modern composers and critics were ready to bury it. Korngold himself never had any doubts about the vitality of this tradition. His rich melodic invention, his ‟spicy” harmonies that nevertheless remain firmly anchored in tonality, and his perfect understanding of the virtuoso violin idiom enabled him to make an important contribution to the repertoire. Yet at first, the concerto found little favor with violinists, despite Heifetz’s strong advocacy. (Heifetz recorded the work twice: once with the New York and once with the Los Angeles Philharmonic.) Since the 1970s, Korngold’s Violin Concerto has become part of the standard repertoire, with numerous recordings and frequent concert performances all over the world.

which the composer himself has pointed out, lends an added emotional charge to the work as it progresses from a haunting clarinet solo at the beginning to a passionate conclusion.

Masterworks 4

El amor brujo (“Love, the Sorcerer,” 1914-24)

by Manuel de Falla (Cádiz, Spain, 1876 - Alta Gracia, Argentina, 1946)

Manuel de Falla was already well established as the foremost Spanish composer of his generation when he was approached by the famous flamenco dancer, Pastora Imperio, with a request to write a piece for her troupe. Since Imperio was an accomplished vocalist as well as a dancer, the protagonist had to sing as well as dance in the new work. Falla and Imperio worked with a libretto that was credited to Gregorio Martínez Sierra a highly regarded playwright and poet–although it was actually written, at least in part, by Martínez Sierra’s wife, María Lejárraga, a prominent author in her own right. Their work made use of some old fables told by Imperio’s mother, Rosario la Mejorana, herself a celebrated flamenco dancer.

In the story, a Gypsy woman named Candelas is haunted by the ghost of her murdered husband José (who had cheated on her while he was alive). The ghost forces Candelas to dance with him every night, getting in the way of her romance with Carmelo (with whom she had been in love before her family married her off to José). Even the magic fire ritual does not succeed in exorcising the ghost. It is only when José’s old lover appears and distracts the ghost that the love between the two protagonists can finally flourish.

El amor brujo went through a number of versions over the years. The original 1915 production was a gitanería or Gypsy entertainment, with spoken dialog, flamenco singing and dancing. Unsuccessful as a play, the music was revised for classical singer and orchestra in 1916 and again in 1924, as a ballet pantomímico using a larger orchestra. This last version has become the standard form of the work in which is most frequently performed.

This final version, which will also be heard at this weekend’s concerts, consists of thirteen sections, some of which are extremely brief. It includes the “Dance of Terror,” the ever-popular “Ritual Fire Dance,” the “Dance of the Game of Love,” as well as three vocal numbers, sung in Andalusian Spanish. In Falla’s music, the sounds of flamenco are combined with French impressionist influences; the resulting fusion of styles is a perfect vehicle for the mixture of passion, folklore and the occult that gives this ballet pantomímico its unique flavor

Masterworks 4

Danzón No. 2 (1994)

by Arturo Márquez (b. Álamos, Sonora, Mexico, 1950)

In the 31 years since its premiere, Arturo Márquez’s Danzón No. 2 has enjoyed immense success, not only in Mexico, where some have even called it a ‟second national anthem,” but internationally as well That is hardly surprising, since the piece takes a string of irresistible Mexican dances, of the kind one would normally hear at a dance hall, played by an orquesta típica or a mariachi band, and presents them in the full colors of a large symphony orchestra. The effect is quite spectacular!

The danzón, of Cuban origin, is in the Latin world what the waltz is in Europe. A stately couple dance that is considered the main event at any ball, it starts slowly and allows for some close contact between the dancers, but eventually speeds up and can get quite fiery towards the end. Aaron Copland had earlier been inspired by the danzón in his Danzón Cubano (1942). Márquez has now made it into one of his signature genres; to date, he has completed no fewer than nine danzones.

Danzón No. 2 was written in early 1994 during the Zapatista uprising, which fought for the rights of the impoverished indigenous populations in Mexico This circumstance, which the composer himself has pointed out, lends an added emotional charge to the work as it progresses from a haunting clarinet solo at the beginning to a passionate conclusion.

Notes by Peter Laki

Masterworks 4

Canción del amor dolido Song of Sorrowful Love

¡Ay! Yo no sé qué siento, ni sé qué me pasa, cuando éste mardito gitano me farta

Candela que ardes

Más arde el infierno

Que toita mi sangre abrasa de celos!

¡Ay! Cuando el rio suena, ¿Qué querrá decir?

¡Ay! ¡Por querer a otra

Se orvía de mi! ¡Ay!

Cuando el fuego abrasa

Cuando el rio suena

Si el agua no mata el fuego

A mi el pensar me condena,

A mi el querer me envenena, A mi me matan las penas. ¡Ay!

Ah! I don’t know what I feel, nor what is happening to me when this cursed Gypsy deserts me. How the candle burns, Candela! My blood, enflamed by jealousy, Burns more than hell!

Ah! When the river sings, What does it wish to say?

Ah! For the love of another woman He forgets me! Ah!

When the fire burns,

When the river sings, If the water doesn’t extinguish the fire, I am condemned to suffering, I am poisoned by love!

My sorrows kill me Ah!

Masterworks 4

Canción del fuego

fatuo

Song of the Will-o’-the-Wisp

Lo mismo que er fuego fatuo, Lo mismito es er queré, Le juyes y te persigue, Le yamas y echa a corré.

¡Malhaya los ojos negros Que alcanzaron a ver!

¡Malhaya er corazón triste Que en su llama quiso ardé!

Lo mismo que er fuego fátuo Se desvanece er queré.

Just like the will-o’-the-wisp, So is love.

You flee from it and it runs after you, You call it and it runs away.

Cursed are the dark eyes that get to see it!

Cursed is the sad heart that is set on fire by its flame!

Just like the will-o’-the wisp, Love vanishes.

Masterworks 4

Tú eres aquel mal gitano

Que una gitana quería, El queré que ella te daba, ¡tú no te lo merecías!

¡Quién lo había de decí Qué con otra la vendías!

¡Soy la voz de tu destino!

¡Soy er fuego en que te abrasas!

¡Soy er viento en que suspiras!

¡Soy la mar en que naufragas!

You were that evil Gypsy Whom a Gypsy girl loved

The love she gave you

You did not deserve!

Who would have thought

That you would trade her for another?

I am the voice of your destiny!

I am the fire in which you burn!

I am the wind in which you sigh!

I am the sea in which you founder!

Danza del Juego de Amor

Masterworks 4

Las Campanas del Amanecer

The Bells of Dawn

¡Ya está despuntado el día!

¡Cantad, campanas, cantad!

¡Que vuelve la gloria mia!

Day is awakening!

Sing, bells, sing!

My joy is back!

Translation from Decca CD 410 008-2 (1983)

Credited to Chester [the publishing house J. & W. Chester, Ltd., London]