C ONT O

A Letter from the Editors

Creating The Colton Review each year is a process that never ceases to inspire us. The art and literature that the Meredith community shares with us always bring new perspectives, and no volume is like any other.

In a change from previous years, this year we find ourselves publishing a volume with more prose than poetry. We are excited to share genre pieces from science fiction, horror, and fantasy, along with contemporary realistic fiction, creative nonfiction, and poetry that we hope you enjoy reading as much as we have.

When working through submissions, it is always fascinating to see various themes and ideas unfold before us, as it seems that each year brings its own motifs to the table. This year has been no different. Many works in this year’s publication deal with reflections on childhood friendships, familial relationships, and the complications that come with them. Maybe as we find ourselves yet another year removed from the beginning of the pandemic, we have found ourselves thinking back to who we used to be, who held us, and who we wish was still here. Perhaps now we have the space to look back and find some catharsis in the past.

“Friendship, I have said, is born at the moment when one [person] says to another, “What! You too? I thought that no one but myself . . .”

C.S. Lewis

Additionally, many of our poems include reflections on the little things in life, whether that is a moment of camaraderie at a stop light or enjoying a walk in the rain. Appreciating what may seem mundane in the moment becomes all the more poignant when the little things we take for granted are ripped away by change, like a pandemic, or beginning a new chapter, like college.

Through the literature we received, we find ourselves exploring themes of friendship and family—and how familiar those relationships can seem even when seen through the lens of fiction. This collection offers a glimpse into the connections that shape our human experience, and cultivates a feeling of togetherness, both between the characters in these stories and within readers who see pieces of themselves reflected on the page.

Lastly, we would like to thank our art team, our judges, and our readers. You all give life to our creative process, and without you, the publication would not be possible. We invite you to grab a warm beverage, curl up, and enjoy The Colton Review: Volume 19 like chatting to a friend.

Sincerely,

The Colton Review Staff

the camaraderie of people turning

By Layla Davenportone yellow arrow and one red light one turning left and the other turning right the vision of the latter is limited, but the former is the guide. consider it an act of kindness, when everything else is like a crashing tide.

we never notice the camaraderie of people turning but, in that moment, when i am of the turners, either left or right i feel this torch of hope burning one yellow arrow and one red light all of sudden, we’re so alike and we’ve noticed the camaraderie of people turning.

Empty Shapes and Uncolored Lines

By Sarah PageAnna and I walk together through the crunching carpet of the woods behind my house. Her long red hair somehow doesn’t catch on the branches as we push ourselves deeper into the forest. We are questing, in search of the magnificent. I want to meet a cunning water-dwelling serpent or perhaps an enigmatic enchantress. I want to take her to my favorite place. The woods are a timeless old forest, filled with aged softwood trees, cedars and pines. They spin out time in an almost infinite stall against the destiny of being choked to death by young hardwoods seeking priority. The standoff is unending. If I could stall indefinitely I would. But I am not a tree, and Anna, my best friend, will be leaving soon.

We come to the edge of the little creek, an expansive gulley to my eyes. I wonder if it looks so vast to Anna, three years older than me and wiser in most situations. Everytime she speaks it’s with soft certainty, in contrast to my loud seven-year-old chatter. Anna is moving to Florida soon. We haven’t talked about it, and I don’t know why we are silent right now. That morning, she brought me a present, a handmade coloring book held together with scotch tape. Anna had hand drawn every image, all characters from our favorite book series about a pig that solves mysteries with the help of his fellow barnyard creatures.

Here, by the creek, the forest smells like pine needles and leaf decay. It’s an earthy scent that almost crumbles away before each breath is complete. No matter how deeply I inhale, it doesn’t stay with me. I don’t mind though. I’m not here for smells. We behold the object of our journey, a tree. The most unique one in the forest.

The tree’s trunk is so wide, I used to wonder if I could live inside it; even now my arms are too short to encompass it. It must have become too heavy to

grow on the creek bank decades ago, and now it has toppled over the side and into the creek. But instead of dying, the tree’s roots have clung to life inside the earth. It kept its grasp on the bank’s soil, and now the bough of the trunk has molded itself to the bottom of the creek. From there it continued to grow up into the sky as if nothing was wrong.

It is important for Anna to see the tree before she leaves. Who knows if Florida even has trees? Large portions of its roots, still living but no longer in the ground, have spread out and up one side of the creek bank, latticing together to make a kid-sized crawl space. We clamber inside, Anna first, and lie against the soft cool dirt to stare up at our roof of roots.

“It’s like a secret cave,” Anna whispers.

“Yeah,” I reply softly.

That morning, with the coloring book, she had included hand-drawn paper dolls. We’d sat on the floor of my bedroom playing for hours. Together we were like the maidens of Mögþrasir, the Norns, deciding destinies in our own little world. We colored life, tragedy, and comedy into the outlines of a story. Out here in the woods is a real life adventure to share. Maybe she will want to stay here in the tree cave forever.

“Look,” Anna says and points at one of the roots. Not visible from the outside but from within, there is a little hollowed-out hole.

“We could put buried treasure in,” I say, and immediately we both crawl out to find some. We cast about searching for treasure, as if the creek will hold gold coins and silver bars.

“We can use rocks!” I exclaim.

“I like that. Then we won’t leave anything here that shouldn’t be,” Anna says. Rocks are not hard to find. We scale up the side of the creek, taking care not to slip on the leaves.

“I fell down that bank once. Right there, see? A deer decomposed there too.” I point out important features as we walk. Anna listens intently. She always listens to my chatter, even the needless kind.

“Look at that tree.” Anna taps my shoulder and points. We gather at the base of a fallen pine near the creek that is less fortunate than our cave tree. This tree is long dead but no less huge. Its roots are yanked from the ground and filled with clumps of clay and soil that have also been sundered from the earth. There’s so much soil that it is a mound at the base of this tree. Within the mound we find our buried treasure. We pluck several handfuls of rocks from the earthbound tendrils. Some roots protrude from the soil, pointing toward the sky, almost in imitation of a trunk.

Most of our spoils are quartz, maybe some mica. To us they are beautiful. The sunlight that trickles down through the canopy catches the purple quartz perfectly, making it stand out from our filthy palms. Within the quartz are both clear and solid patches. The mica gleams, the silver-like chunks flaking away in my hand if I rub them. We carry our dragon’s hoard back to our secret cave and bury it inside the hole. We tuck leaves over it, and then walk away together.

Anna leaves for Florida the next day.

That night, I color one image in the coloring book, but I leave the rest blank, afraid to ruin something already so perfectly drawn with my childish, uneven scrawls. I don’t play with the dolls that evening either; I don’t feel like coloring by myself.

Anna sends me letters, but I seldom write back, my writing as unintelligible as hers is beautiful. She can use words to cross the gap between us. But I never know what to say to her. There is both too much and too little to tell her.

But our tree guards our treasure by the creek, undisturbed for years, forestalling the inevitable.

Honeysuckle Summers

By Tamara Bomparte Honorable Mention ProseYou and I were a bit like chaos, running around with no direction and without a care until broken people and broken promises taught us otherwise. In those days, those carefree summer days in the before, we would spin in cartwheels next to the pond, catch tadpoles in our bare hands, squealing when they wriggled, and chase butterflies as far as our arms could reach. We whispered secrets back and forth, feeling so grown up, and I knew that we were safe together. You would catch my eye, and the corners of our mouths would raise until, suddenly, we were laughing with abandon while our bellies ached and your mom gave us that piercing look. The warmth of a perfect afternoon in your company was perfect bliss, and I wondered if it was from the sun or from you. We felt weightless jumping on the trampoline, and I came up with bad ideas while you came up with worse.

Like that time you were searching for unknown sea creatures in the pond and your new bracelet slipped off and down, down, down, into its depths, or when we shaved off a layer of skin taking a corner way too fast on your scooter. I always told you not to, but you never listened and in the end, I really didn’t mind. We ate the nectar from honeysuckle blossoms, from that random patch of yellow, white, and green that grew there just for us. And we didn’t have a single care in the world. Chaotic in our belief that everything could stay the same.

After divorce papers are signed and a moving truck carries you away, the pond is peaceful without four reckless feet disrupting the sand around it. The tadpoles grow into frogs and the butterflies are never disturbed by the grubby hands of children again. They wouldn’t recognize us now. I can’t blame them; I don’t either. The trampoline blew away in a storm that you weren’t here to witness, and I can usually talk myself

out of bad ideas without your influence guiding me. Though it probably caused me more trouble than it was worth, I miss that voice, urging me to be carefree and reckless. When I catch the faint whiff of honeysuckles, though they no longer grow in that patch by the road, I think of chaos and sunshine and you.

It was a beautiful autumn day. Parker was grateful for the thirty minutes of alone time he got every day during lunch. He liked hanging out with his friends, but he wasn’t eager to take part in their games of throwing food at each other. He made his way to his beloved bench, his bag bouncing against his leg with every step. His spot was far removed from the normal lunchtime antics, but it was close enough that they could find him if they really needed him.

Parker pulled a plastic bag out of his plain brown paper bag. Peanut butter and jelly wasn’t his favorite, but he didn’t have much of a say when his lunch was made. He peeked inside the bag to see what else was thrown in during the morning rush. At 11 years old, he wasn’t sure what the appropriate amount of food was for him. But a sandwich and a juice box didn’t seem like enough.

As Parker rummaged through the paper bag, a distinct sound of jangling zippers rose above the distant chatter. The jingling zippers were getting louder, the pattern matching the beat of footsteps getting closer and closer to Parker’s sacred spot.

“Do you mind if I sit here?” a high-pitched voice inquired.

Parker tried not to look up in hopes of the girl going away. He glanced down at the shoes of the girl asking to take the place of his book bag. She rocked back and forth on her lilac sandals, her toes wiggling as if they were waving to him. He waited a few more seconds before giving in and moving his blue bag, nodding his head. She gladly took the seat.

“My name’s Jacee,” the girl said. The introverted boy nodded his head, choosing to focus on discovering the unknown contents of his lunch bag.

“Well, are you gonna tell me your name?” she asked. It was a valid question, but Parker wasn’t interested in giving a valid answer.

“Parker-Basil, but I go by Parker,” he dryly replied. Jacee giggled, and he shot her a scathing glare.

It depends. Sometimes I feel girly, but other times I feel boyish. Like today, I’m feeling girly,” Jay gestured to their shoes so I’m okay with wearing my sparkly sandals. “But I don’t know what I’ll feel like tomorrow.”

The giggling subsided.

“Sorry, it just sounds weird,” she said. “Almost like a park name or something.” An awkward moment of silence fell between them.

“I like it, though. It’s pretty unique.” Another beat of silence.

“Can I call you PB?” Parker-Basil rolled his eyes.

“Honestly, I don’t care what you call me as long as you stop talking to me.” That was enough to shut Jacee up and refocus her.

Part of Parker-Basil felt bad for not engaging Jacee in conversation. The nickname wasn’t the worst thing he’d been called (in 3rd grade, his friends started calling him a “p-word b-word,” which caused him to drop the Basil. Being called a “p-word” wasn’t really any better, but it was better than having two insults tied to your name). Determined to be nicer, he tried to look closer at the nuisance beside him.

On the bench sat a girl who appeared to be younger than he was (no more than four years, he assumed) but dressed a little older than he did. Her sandals barely brushed the concrete sidewalk. Her skin was just a shade browner than his, with short black hair and plain brown eyes to accompany it. Despite his fear of being too harsh, Jacee seemed unbothered as she rummaged through the contents of her purple and pink polkadot bag.

In Parker’s eyes, there was nothing unique about her. But he still felt like he should try to talk to her. He pushed his glasses up on his face, took a deep breath and said,

“If you call me PB, can I call you Jay?” Jay looked up in

excitement, revealing a grin with two missing front teeth.

“You can call me whatever you want if you stop calling to me,” she said enthusiastically. Not quite what PB said, but he took it.

“I’ve never seen you before. Are you new?”

“Yeah, I just started here last week,” she said. PB continued to stare as Jay rummaged through her purple and pink polkadot bag, finally pulling a similar-patterned lunch box out. Her indecisive mannerisms continued as she searched for something to eat. At one point, Jay’s gaze wandered to something on the ground.

“Hey, we have the same shoes on,” Jay said.

PB’s gaze followed her pointed finger down to his feet, where he realized his dirty red shoes matched the design of Jay’s pristine purple ones. Jay returned to her lunch box in search of something to eat. But PB’s interest remained with the shoes. His dad bought the shoes for him during one of their rare occasions spending time together almost six months ago. He claimed they were special shoes that no one else would have, since no one else was a big boy like he was. PB felt like a fool for believing a man who could never remember what day it was.

Six months ago, Parker-Basil had seen the lilac sandals before. The sparkly straps and multi-colored flowers caught his eye instantly. They were unlike any other shoe he’d had before. He walked over to his father—who was looking at Nike sneakers on the other side of the store—to tell him about his decision. Parker-Basil grabbed his father’s hand and pulled him with more urgency than he ever had before. As they got closer to the lilac sandals, his father’s chuckles grew louder. He erupted into a roaring laugh when they came to a stop.

“You can’t be serious!” he yelled. The frightened young boy looked around the store. Every parent, child, and associate’s eyes were on his father at the moment.

“They’re fucking girl shoes,” his father said. The look of fury wasn’t new to Parker-Basil (or being told off in public, for that matter). But it was the first time he’d wanted to fight back. He could feel his cheeks heat up with every second that went by—and his voice rose with it.

“No they’re not!” he exclaimed. He regretted it as soon

as the words fell out of his mouth. Between the blur of his dad thrashing him around and the surrounding people yelling in horror, Parker-Basil lost sight of the lilac sandals. His new shoes were special to no one but him.

When he looked up, Jay finally settled on a pack of Disney Princess gummies, provoking a chuckle from PB. She glanced over at him with a raised eyebrow, showing her curiosity in the origin of his response. Realizing Jay had heard him, he tried to explain himself.

“I used to like those too before I realized they were for girls,” he told Jay.

“Well,” said Jay, “I’m not a girl.” PB furrowed his eyebrows. He wasn’t exactly sure what to say, but Jay found the words for him.

“It’s okay. My mom said a lot of people don’t understand.”

PB, still confused by Jay’s confession, said, “well, what are you then?”

Jay shrugged their shoulders.

“It depends. Sometimes I feel girly, but other times I feel boyish. Like today, I’m feeling girly,” Jay gestured to their shoes. “So I’m okay with wearing my sparkly sandals. But I don’t know what I’ll feel like tomorrow.”

PB still didn’t understand, but he didn’t know what other questions to ask. Jay attempted to open the Disney Princess gummies. After watching them struggle for a couple of minutes, PB reached over to help. He returned the package to Jay open and missing a gummy (a repayment for his endeavors).

“Thanks,” they said. “My dad packed my lunch today and forgot to open it for me. I usually have trouble opening it.”

“That’s cool. I packed mine on my own.” PB bit into his PB&J. Unsurprisingly, all he could taste was the peanut butter. The Food Lion brand grape jelly was too high in the refrigerator for him to reach that morning, and he was too afraid to wake his dad from the drinking-induced coma he’d been in since the night before. PB knew it was wrong to lie to Jay, but it wasn’t

continued on page 15

Kickback Charcoal by Hayli Ira

Kickback Charcoal by Hayli Ira

lying if they were half truths. He always felt the need to overcompensate for things he had no control over.

Before he could stop himself, PB opened his mouth and asked, “Why did you sit over here?”

Jay looked over at PB as innocent as one could look. Their smile revealed a huge gap between their two front teeth. PB tried to overlook the only unique feature that separated the two of them.

“Well, I needed a friend. And from the looks of it, you needed one too.” Jay swung their stubby legs back and forth, knocking against the base of the bench. Before he got the chance to tell Jay he didn’t need any friends and was fine on his own, the bell rang, signaling the end of the lunch period. Jay hopped off of the bench and put their lunch box in their bag, zipping it up and slinging it over their shoulder.

“Wait,” PB called to them. “You barely ate anything.” Jay shrugged their shoulders, unbothered by the possibility of malnutrition that was haunting PB.

“You didn’t either.”

By the time PB thought of an equally snarky response, Jay already made their way back to the school building. They were lined up outside of the 400 building, the kindergarten building. He wasn’t entirely thrilled that his new friend was more of a toddler than a kid his age, he wasn’t too upset that he met them.

Powdered Sugar Faces–Senior Animals Photography by McKenzie Bowling

Powdered Sugar Faces–Senior Animals Photography by McKenzie Bowling

On growing up

By Morgan Maddocks 2nd Place PoetryAdulthood is scary enough, especially when you do not feel like an adult and don’t want to Be brave and call the doctor’s office yourself. Or when you have to drop off your Car at the mechanic and you are afraid that because you are a woman, they’ll try and Dupe you into thinking your car needs a new axle, or your transmission is shot, or your Emergency break needs replacing. Adulthood is scary because no one tells you that Fair weather friends are hard to point out until it is storming, you are suddenly alone, and God dammit, you wish you had someone to shield you from the rain. How come my mom didn’t warn me how expensive fruit is and how difficult

It is to get out of bed and go to class on the days it’s cold and rainy?

Just the other day I was looking at myself in the mirror and I was suddenly sixteen again—a Kid really, who thought she knew everything there was to know about everything. Just a Loudmouthed, sixteen-year-old girl who used her outspokenness and wit to hide the fact she was Maybe a little less confident than she let on. I wish I could tell that girl she has No idea what her life is going to look like in five years and how terrifyingly beautiful that is. Or, maybe I would tell her that there are more important things than boys with charming smiles. Please don’t go for the boy with the charming smile. I miss that she wants to grow up so Quickly because now, I’m realizing that getting old is no fun. I want to tell her that the Responsibilities that come along with adulthood aren’t all they’re cracked up to be. Some days I miss not having to worry about overdrawing my checking account or Taking the GRE because I’ve decided grad school is the best way to put off being a “real adult.” Under stress coal becomes a diamond, but not me. I don’t know if I can have the same Voracity for life I had when I was little. I know I’ll look back at myself in ten years and Wonder about my priorities and laugh at what I found important. I know I’ll grow through Xeric conditions because life cannot always be green and lush. That’s what adulthood is, right? You navigate life pretending to have it all together, feigning confidence and dodging every Zig and zag life sends your way. Because all adults feel this way, right?

This First Saturday

By Sarah PageThe soft fabric of the bed tickled the back of my neck, and a beam of sunlight from the window flashed across my glasses. I’d been here for at least thirty minutes, just staring out the window. Long enough that the light was starting to change. It was Saturday, and it wasn’t like I had anywhere else to be. Everyone else was out. Mom had offered to take me to the movies when they got back from dropping Melanie off and Dad asked me if I wanted to go out and see the game with him next week, but I’d said no. I’d rather sit here and look out the window. My phone buzzed, and I picked it up, bored. But then I swiped my finger and set the phone down, turned on my side, and faced the other side of the room.

Her bed was empty, and the wall, which last week had been plastered with photos, posters, and Command strips, was now bare and pockmarked with old pieces of tape, ripped plaster, and the one or two photos that she’d left behind when she packed up her life and left for college. I rolled away and turned my back on the scene behind me. It was fine. I’d made my choice and she’d made hers. She’d decided not only to go to college, but to move halfway across the country and miles away from us. Her last day had been filled with her and Mom chaotically running around the house collecting stuff at the last minute. Our dad packed and repacked the car to make sure everything could fit. As soon as he got it just right, my sister would emerge with another box or backpack that needed to be fitted in, and my father would have to reshuffle everything. When it was all said and done, there wasn’t space for me to ride along with them. I hadn’t wanted to go anyway. So instead, I sat at the window to watch them drive away before burying myself into my pillow.

I wasn’t trying to behave grumpily, it was just natural. The room was so still and silent. Usually, Melanie would be blaring music on a Saturday afternoon, and I’d be shouting at her to turn it down. But her speakers were packed and being whisked away to their new

home. I hoped Melanie’s roommate liked eclectic twentieth-century composers. Only last week, I’d been awoken by a horn and trombone loudly and tremulously climbing up and down the chromatic scale. Melanie hadn’t been in the room, so, wordlessly, I’d rolled out of bed and slunk over to her side of the room. I pressed the power button, and the blessed, heavy pressure of silence descended upon the room. I walked back over to my bed, crawled back under the covers, and closed my eyes. Mom and I had done all the sheets the day before, and my pillow still had a sweet fresh floral smell to it. In a few minutes, I faintly heard the speakers’ power button come back on and then the room was flooded once again with too much sound. This time I rocketed out of bed.

“Shut that stupid thing off!” I’d shouted.

“It’s twelve in the afternoon!” she’d shot back.

Now, alone in what was once our room, I slowly rolled off the bed and wandered down the hallway to our shared bathroom. My bathroom now. I stuck my head around the door. Melanie’s side was covered with leftovers that she hadn’t deemed worthy of taking to college. Half-finished bottles of face cream and old nail clippers lay forlornly on the counters with a mostly empty bottle of red hair dye from a night of bad decisions. Shiny new counterparts were loaded into the car and on their way with my sister. My side was a jumble of stuff. Too much stuff. I poked around the drawer on my side. Hang on. My curler was missing. Damn, she must have taken it. I opened my phone to ask why the hell had she taken it, only to see that she’d already texted me.

I took your curler, hope you don’t mind. I huffed. I barely used it, so that wasn’t a big deal. I saw that she’d sent some other messages as well.

I took those brown boots you never wear too, I promise I’ll bring them back.

“Of course you did,” I muttered out loud, stalking

out of the bathroom. I passed the pictures of us in the hallway. One was from Halloween eight years ago, and another was of seven-year-old Melanie leaning out of a canoe, while I gripped her shirt from behind looking absolutely terrified. The boat had been in shallow water.

I continued down the hall and descended the stairs slowly. I felt crumbs in the carpet tickle my bare feet as I went. The feeling sent a shudder down my spine. I hated having crumbs between my toes. She was supposed to vacuum the stairs too, but must’ve forgotten with all of the preparations. I wandered into the kitchen lazily. A half dried out snake plant languished on the windowsill above the sink. A few months ago it had been fresh and healthy. I’d been pulling it out of its old pot to put into a new one when Melanie came downstairs chewing on her lip. I’d barely spared her a glance as she took a seat at our old dining room table.

“Elle, I think I’ve changed my mind about where I’m going,” she said. I grasped the root bound soil of the snake plant and lifted it to the new jar.

“What’s wrong with Hentley University?” I was a fan of her current school choice. The university was only an hour away from here, and I’d got to tour it with her and dad when she first visited. It had everything that she could possibly want.

Melanie ran a hand through her long straight hair, and shook her head. “Nothing is wrong with it, it’s just after thinking about Edelwood College, I think it might be the better choice.” I scowled. The Edelwood acceptance had arrived yesterday, and I’d passed it off to Melanie without a second thought.

“Why?” I started shoving new dirt into the pot to fill up any remaining empty space.

“It’s just, I really want to try somewhere that’s going to be out there and new for me. And Hentley won’t give me that. Plus, the chemistry program at Edelwood is really good. And they gave me a lot of scholarship money, so the cost difference is nonexistent.”

I carefully packed down the soil, stood up, and walked over the sink to put the freshy potted plant down. Melanie kept talking. “The thing is, I know we’ll be apart for a long time if I go to Edelwood, so I’m not sure I should go through with it. What do you think?”

I started washing my hands in the sink to keep my

back turned. I wanted to immediately tell her to stay close, that she would miss me too much, and that we’d need to see each other every week. That I thought it was ridiculous that she wanted to live on campus and thought she should commute instead, so I’d still have to listen to her dumb music all the time.

Instead, I said, “You should make the choice that’s best for you. I think that if you miss us you’ll get used to it, and we can always talk on the phone.” My mouth felt dry and leathery.

“Are you sure?” She didn’t sound convinced. I turned around and grinned.

“Yeah, besides, you’re going to be too busy to spend time here anyway.” I think that’s what she wanted to hear, because she didn’t press further, or notice my hesitance.

“Thanks, Elle! And don’t worry, we’ll hang out a bunch during break.” She’d committed the next day. And hadn’t stopped talking about it since.

Now, the counters, which only 40 minutes ago had been stacked with boxes of stuff to go with the car, were bare except for a half-eaten loaf of bread and a sticky jam jar lid. There were two boxes by the back of the door, both discarded at the last moment. I crouched down and unfolded one of the cardboard lids to inspect its contents. Charles, the stuffed boa constrictor, stared out at me gloomily, and I chuckled. Poor Charles, he, too, had been a passenger thrown out at the last minute. I lifted the soft creature from the box and wound him around my neck. There was a little hole in his neck, where the stuffing threatened to start spilling out. I hooked my fingers in the tear and mindlessly tugged as I straightened my legs.

I remembered when Charles was a brand new boa constrictor that my parents had given Melanie at her 12th birthday party. That had been a long birthday. And a dreadful party. Melanie had invited four of her friends over and no one had come. I’d wandered into the kitchen ready to feast on the overabundance of chips only to find Melanie crying under the table.

The Unknown Cut Paper Collage by Abi Turner

The Unknown Cut Paper Collage by Abi Turner

I grabbed a few packs of Cheetos before crawling under the table to join her.

“It’s gonna be okay.” I patted her head and offered her the chips. Tearfully, Melanie took them and set them down on her other side. On her knees there was a crayon scribbled note. “Is that a letter?” I asked.

Melanie nodded. “Amanda wrote it. She, uh, she doesn’t want to be friends with me anymore,” she whispered and buried her face in her arms.

I reached out and patted her arm. “Why?” I couldn’t understand why anyone wouldn’t want to be friends with Melanie.

“I’m not cool enough for her new friend Jessica, I’m too dorky.” Melanie wailed. I took the note from her and read it, scowling.

“That’s Amanda’s fault for getting a dumb new friend, because you’re great,” I said fiercely. I opened my bag of Cheetos and held one out. Melanie took it and munched slowly. It seemed to help.

“I’ll always be your friend.” I told her.

She scrubbed her eyes. “Thanks Elle.”

“I mean, you’re still a dork, but not too much.” I said playfully.

“Hey!” She reached for me and wiggled away. We both tried to jump up, forgetting we were under a table.

“OW!”

Years later, I wandered around the table and over to the other box. I opened it and frowned. It was full of snacks, and I wondered briefly if Melanie had left it behind on purpose. I poked around the box and withdrew a bag of Cheez-Its to munch on. I opened a kitchen cupboard. It looked strange now, with her mugs gone, like a gapped tooth grin, no longer a full mouth. I grimaced and walked from the kitchen into the garage. In the corner there used to be two bicycles that we rode to school together. Now there was just my green one; my sister insisted that her bike had to come to school with her. Our high school was close enough and our town small enough that we could ride our bikes to get there. I remembered cycling to high school for the first time with my sister two years ago. She was already a junior and had been full of good advice on how things were done in high school. This year would be my first time cycling there alone. I

was more than capable of doing that, but it tugged at my chest in a strange way. Melanie had always been there to help me with my math classes. Back in fourth grade, years ago, Melanie had had to teach me most of my math lessons because I hated my teacher and wouldn’t ask for help.

“You can’t just add the bottoms together like that, they need to match.” It was a chunk of the way into the school year, and I was already suffering. Fourth grade math was even worse than third grade. It was Saturday, we’d been working on homework for an hour, and she was getting close to losing it.

“Why not?” I snapped. Fractions were useless and dumb anyway.

“Because 5 over 6 and 8 over 4 are completely different sized pieces of pie.” She pointed at the circle she’d drawn once again, trying to get her point across.

“So what? A large piece and a small piece will both fit in that pie dish.” My 11-year-old sister had put a hand to her forehead, doing a stellar impression of our mother.

“Just remember the bottom needs to match, okay?”

I had remembered, but I still struggled in math for another two years.

Charles the boa constrictor and I made our way out of the garage and out onto the lawn. I stared at the sidewalk and scowled. It was covered in chalk drawings, some very childish, and several quite intricate. They’d been drawn by Olive, our eight-year-old neighbor who Melanie babysat often. Yesterday afternoon Olive had been over to say goodbye, and they’d drawn together on the pavement. I briefly wondered if Olive’s mom would ask me to babysit for her instead. I sure hoped not; every time Olive and I interacted, we would get into an argument. I lacked Melanie’s easygoing

continued on page 22

It’s just you and me I guess,” I said to Charles. The snake didn’t respond. “I should have told her to stay,” I muttered.

nature; she was a person who could smooth over any obstinate little kid. I would just awkwardly wish for whoever I was talking to to understand me. I walked around to the back of the house where we used to build forts when we were little. The back porch was still scarred from the time I’d knocked over a candle and set fire to the dry wood late in August of last year.

At the back of our lawn the tree line started, but there was one tree that was slightly closer to the house. Beneath that tree there was a large rock, laid over fresh dirt, where we’d buried our cat Screech only two weeks ago. Screech was the sweetest cat ever. He’d technically been Melanie’s cat, but he liked me better. He’d had the softest fur, and every night without fail he’d climb into bed with me, and I’d card my hands through his coat. I’d counted on him to be a companion in my new world of being an only child.

“It’s just you and me I guess,” I said to Charles. The snake didn’t respond. “I should have told her to stay,” I muttered. But I could never have asked her to stay. I was sixteen, and too old to kick up that kind of fuss. Over the last few weeks, Melanie had continued again and again to reassure herself that I wasn’t going to expire without her. And each time I got more and more annoyed with her. Last night as she’d been folding up clothes for her suitcase, she’d asked, “You’re okay with this, right?” I pushed back from my tiny desk and turned to face her.

“Yes, it’s fine, not to mention a bit late to ask,” I said.

“It’s just that I’m not sure you mean it,” she whispered. I started picking at my nails.

“Yeah, it’s great, just think of all the stuff I’ll be able to do when you’re gone. I can sneak back into the house through our bedroom window without worrying you’ll catch me and turn me in.”

“Yeah, like you do a lot of that.” She had a point, I was about as rebellious as a weak breeze.

“People change,” I offered. Melanie hmmed, and pulled out an armful of t-shirts from our closet.

“Well if you’re sure…” she started. I stood up. It was a little offensive that she kept questioning me like this.

“I’ll be fine without you, okay? I don’t need you breathing down my neck forever, you know.” It came out more snappish than I’d meant for it to. She huffed.

“Alright, there’s no need to be mean about it.”

“Then stop assuming that I need you for every little thing.”

“I don’t think that.”

“Sure you do.” I was being antagonistic now. “You want me to miss you and need you.” Melanie opened her mouth to respond, but the door swung open and my father barged in, oblivious to the fact that he was interrupting.

“I need you to look at these tire pumps.” He said it like it was the most important thing in the world. Dad had been going out of his way the past few weeks to spend time with Melanie. Melanie glanced over at me and I shrugged. She stood up and followed my dad out, and I went back to what I was doing.

Now, sitting in the yard with Charles, I felt a little guilty. I’d shunned Melanie all morning, and only said a curt goodbye as they drove away. I should have told her not to go to Edelwood. Hentley was a perfectly good university with an acceptable science program. But it was too late now. The grass was pricking my legs and a ladybug had started crawling up my arm. I could hear Olive’s father mowing his lawn again. I wondered what it was like being other people having a normal Saturday. My phone buzzed again.

I’ll miss you, even if you won’t miss me.

I guess I would want to be missed if I was going somewhere.

Hey you left Charles, he’s mine now. See you at break.

“Of course I’ll miss you, dum dum,” I said out loud and hugged Charles again.

This First Saturday by Sarah Page

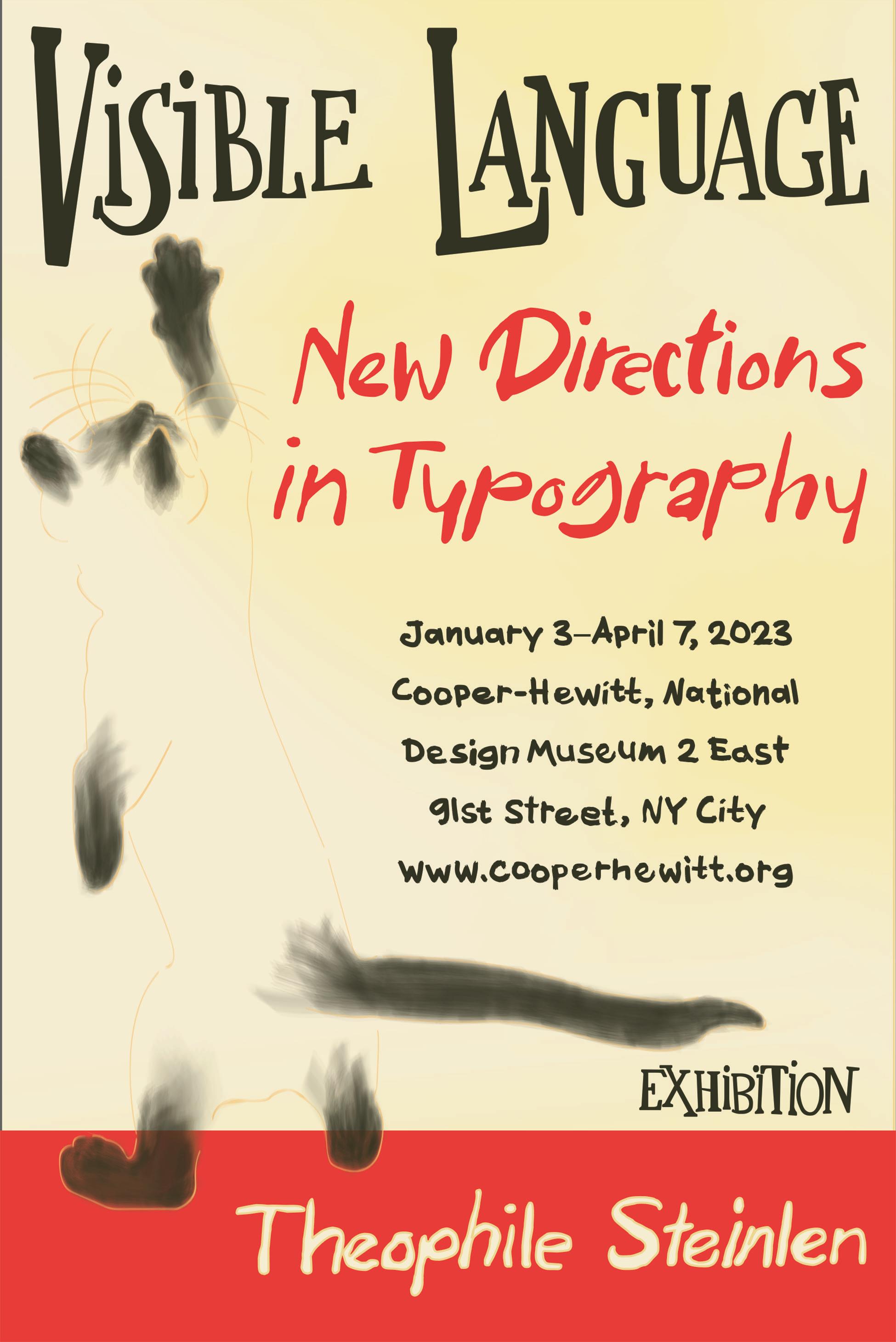

Exhibition Poster Graphic Design by Kimberly Jarvis

Exhibition Poster Graphic Design by Kimberly Jarvis

My World is Pink

By Cady StanleyMy world is pink: flowers, quartz, boldness, feathers, and roses. By my back door, these roses tower above me on a wicker trellis, winding high.

The blooms, striking against the green vines and leaves

And greedy thorns and rust-red brick wall, Stretch toward the pale, faded blue

Of the heavens above us, like pink stars

That have fallen from their place.

I pause on my way out, Standing between my door and my wall of flowers.

I stare absentmindedly and admire

Even the spots of brown and wrinkled petals.

They’re aging. Yet two buds are still closed up tight. Their bold pink lingers inside.

I turn and see the world beyond:

The walls and reds and greens and grays. The rolling fields of rock.

Brick. Money. Red faces

Of men who don’t have enough green. There are no pops of pink

But there are plenty of thorns. My pink is not welcome.

It certainly does not fit. But I love it all the same.

The sky shrinks and darkens, Varying shades of gray loom over The city of boxes: windows, buildings, sidewalks. All gray. Rain falls, but it’s not the blue of lakes. As I begin to walk towards the subway, Wetness saturates my shirt And the fabric rubs harshly against me. A drop of water rolls down my nose. Head bowed, I see my flowers. I hope the rain is feeding them as they feed me. I hope the rain has steeped their soil so they bloom. I hope they’ll grow so bright, Glistening against this world, this gloom.

My World is Pink by Cady Stanley

A man follows us down the crosswalk between the shopping center and campus. I am acutely aware of the feeling of him behind us, like a pricking at the back of my skull, and my surreptitious glance at Taylor lets me know she feels it too.

They’ve stopped putting handles on grocery bags, supposedly to save trees, so the rough brown paper protecting a week’s worth of milk, bread, and lunch meat is balanced precariously between Taylor’s arm and chest. I hear it crinkling as she fiddles in her pocket, looking for something. I try desperately to remember whether she has pepper spray on her lanyard, or maybe one of those cat-ear-shaped keychains. God, why didn’t I buy one of those when I had the chance?

We slip down the convenience path between the sidewalk and the tall metal fence, our rust-coated salvation, standing closer together than we would normally. Her grocery bag scratches against my arm, the tall grass tickles my legs, and I say nothing.

We had been talking about something earlier, before we noticed the man. For the life of me I cannot remember what it was. Probably Batman comics, or something else that seems ridiculously unimportant now, only a few seconds later. I wonder how loud we were being, how obvious and present.

I allow my eyes to dart quickly behind us and see the man standing, determinedly casual, on the sidewalk a few feet from the bus station. He’s smoking a cigarette, but the gusts of wind pushed past by speeding cars carry the scent away before it can enter my nostrils. I’m thankful for this small blessing. The smell of cigarette smoke reminds me too much of burying my face in my grandfather’s chest to allow me to keep myself on edge.

We reach the gate. Taylor’s voice stops me before I go to push it open.

“Can you unlock the gate?” she asks, loudly and clearly, like an actor delivering the opening lines of a play.

“Yeah, of course,” I respond, endeavoring to keep my voice casual. I pull my keys from my tote bag, making a great deal of jingling noise as they hit both each other and then the metal of the gate. My own voice rushes through my head, reminding me that it’s broad daylight right next to a busy street, but also reminding me to slip one of my keys between my fingers in equal measure. After a moment of frantic movement, I step back and push the gate open, just wide enough for the two of us to slip through.

On the other side, there is no sigh of relief. I take a few steps through packed-down dirt before realizing Taylor isn’t beside me. I turn. She’s still at the gate, readjusting the bag under her arm as she pushes the creaking metal back in place. I watch, biting my lip, trying not to let my eyes skim over the man, still a few feet away, and failing.

I realize, sharply and suddenly, that Taylor is braver than me. It is a slightly irritating though insignificant realization, like a thorn poking through the bottom of my shoe while I am already in a forest full of wolves. I want to reach for her hand, but it’s still holding onto the grocery bag, gripping hard enough to send wrinkles through the thick paper. I grab my own hand instead, twirling my fingers through each other in a way that mimics but fails at comfort.

We both know that the gate has no lock.

The monster in the lake

By Sadie RoundsI sat shivering in the back of an open ambulance, voices coming from every side of me, but the words weren’t making sense.

“What day did you go out to the lake?” an officer asked, and as I opened my mouth to respond, my thoughts raced too quickly for me to comprehend and no sound came out, even as I tried desperately to form a coherent thought.

The crinkly, foil emergency blanket wrapped around my shoulders did nothing to warm me. Freezing blood raced through my veins as dread sank deep to the pit of my stomach, my heart broken in a way that felt too far beyond repair.

The water had looked so clear, so inviting. The trees surrounding the lake were deep green and so full, they formed a barrier of sorts around the water. They loomed over the lake, and I could understand how people saw them as menacing, in a way. They were beautiful, though, and I could see them reflected off the surface of the bright water.

How could a place so beautiful have something dangerous lurking beneath the surface? I could see my hand clearly when I reached my arm out of the canoe and dipped it in the water. It was warm and silky against my skin. I pulled my hand back and instead prepared myself to jump in, drawn in by the smooth, glistening ripples in the water.

I heard the warnings in the back of my mind as I put my feet in and pushed myself out of the canoe. The water was just so crystal clear. Surely, I thought, I would be able to see it if it were true.

I felt something brush up against my leg, and I startled so suddenly I hit my head against the side of the canoe. “Ow,” I whined, rubbing the back of my head as I looked down into the lake. I couldn’t see anything in the

water from where I was, only my body and the floor of the lake that was further down. The longer I looked into the water, the more drawn I felt to it. I ducked my head under without willing myself to and felt the pressure of the water in my ears, engulfing my head. I kept my eyes squeezed shut but tried to feel around for whatever touched me when something wrapped around my wrist and yanked me further down.

“No, absolutely not. You are not going to that lake. Girls have been going missing down there for the past few months. I am not going to let you be one of them,” my best friend Natasha had told me just a couple days prior as we sat at our favorite park, playing double solitaire.

“Aren’t you curious why, though? Nothing else ever happens in this town. It would be fun to explore, don’t you think?” I had said back, but she just shook her head and moved one of her cards over.

“No, I don’t, and I don’t understand why you do. Please, just promise me you won’t do anything stupid,” she had responded, and I agreed sullenly. It was the only promise I had ever broken.

I didn’t expect the monster to be so pretty. Everyone talked about the myth as if the beast was supposed to be scary, with its sharp teeth and claws and horrifying eyes. But he had gorgeous skin and hair and piercing blue eyes and looked more like a mermaid than a monster.

I was only scared for a moment when he first pulled me down. But I was transfixed, staring into his eyes as he slowed down swimming, and I think I immediately fell in love with his shiny scales and his bright smile as he looked at me with a wonder and admiration that I had never seen before.

It could have been minutes or it could have been hours before we got to his cave. There were other girls

there. They looked like me, each around my age with similar hopeful eyes and an obvious desire to please him. I didn’t know how long they’d been holding their breath, but they didn’t look like they were struggling, and I didn’t feel a burning in my lungs, no need to fill them with oxygen. It must have been one of the many spells he put on me.

We only stayed for a little while. He watched me as I looked at each of the girls sitting around. There were three of them, and two of them were looking at me with narrowed eyes, seemingly sizing me up. The other had her eyes downcast, melancholic, and almost… absent.

He suddenly grabbed my hand, and I forgot all about the other girls, all about my life outside of that moment. He pulled me along the outside of the cave to a large pile of rocks. He began pushing them aside, and I watched as they slowly sank to the bottom, clouds of sand erupting around them as they hit the ground.

He pulled me closer to the rocks, and I noticed a collection of beautiful shells and stones that he had accumulated. I recognized some of them as shells I had seen on different snails up by the lake shore. He pulled up something from the top of the pile, and I realized that it was a necklace made of the shells and grass. He pulled it over my head and watched as it dangled from my neck. I smiled as the weight of his attention sunk into me.

We returned to the cave, and the girls looked at me again. They had to notice the necklace. I wore it as a symbol of pride; I was his favorite in the cave. I was the most valuable.

We went deeper into the cave, and I turned to him and jumped slightly. He was looking at me intently, and while it was slightly unsettling for a moment, the longer I stared, I realized it was love that made him look at me like that.

“Beautiful,” he said, and it was the first time I had heard his voice.

I felt emboldened by his love for me, confident in our relationship. I wasn’t sure if I even could use my voice, but in a moment of excitement, I tried anyway. I said, “What if you came to see my world with me? I would love to show you around.”

He recoiled immediately as if my hands had burned him, and his eyes darkened like they were filling with

ink. I looked around and saw the faces of the other girls in the cave looking at me with horror and pity, eyes wide and brows raised. I jumped back and screamed bubbles into the water as I turned to see his teeth turn razor-sharp and his smooth skin turn green and bumpy. I watched in terror as he grew in size and claws popped out of his fingertips.

My voice disappeared into the waves, and I felt the sudden urgency to take a deep breath of air, but when I opened my mouth, I could only breathe in water. The monster grabbed me by the neck, his sharp talons piercing my skin, and dragged me out of the cave. He pressed the shell necklace into my skin. I had to close my eyes as the passing water stung them.

We reached the surface and the monster threw me to the shore. The sand and grass broke my fall only a little, and I felt fire race through my body as pain and soreness burned everywhere. I looked out to the water just in time to see the monster’s tail disappear under the surface.

What hurt more than the aches and pains all over my body was the weight of the rejection overtaking my body. I wasn’t good enough for him. I tried to share my life with him the way he had with me, and he rewarded me with broken ribs and a broken heart.

The longer I sat staring into the asphalt, blue and red lights flashing around me, the more awareness I gained of my surroundings.

“I can’t believe there was another one,” I heard someone say, and I looked over to see two bystanders talking far enough away they must have thought I couldn’t hear.

“I know. When will they learn? Just because something looks pretty doesn’t mean you have to jump in head-first,” the other responded. I looked down at the broken shell necklace in my hands. You couldn’t keep to yourself, huh? You couldn’t keep him happy. I felt my heart sink and eyes fill with tears as the realization fully kicked in.

He didn’t choose me, and it was all my fault.

Faded

By Sumeyya MiralogluHow often

Have people used you

Making messes on you

Not caring

Because they knew

You were costly

But nonetheless Replaceable?

My dear, How often

Have you felt

People walk all over you

Tracking mud in with their boots

Piercing your heart with their heels

Without a care

As to how you might feel?

My dear, How often

Have you supported

Their weight

Yet still

They never saw you

Or appreciated you?

My dear, How often

Have people spilled bitter coffee over you

Burning you.

Even when they tried to scrub their mistakes off of you

They only spread it all over

Marking you permanently.

My dear, How often

Have they tried to cover the stains on you

With other pieces of their collection

Couches and lamps, Tables and ottomans, But the stains will always be there

Embedded into your very being. You are engraved with the mistakes of others

A permanent reminder

Of your plummeting value.

My dear, How often

You’ve witnessed

People grow

Heard them laugh

And cry

Heard them confide their pains

At night

Their aspirations

In the day

And in the end

Still They left

Not even once

Acknowledging your existence.

continued on page

My dear,

How many days

Have you absorbed the sun’s rays

And how many a night

Have you basked in the moonlight

Catching shadows and pretending they were your friends

Because they held no weight on you

Yet they inevitably left you

As well.

My dear,

You and I

We are cut from the same cloth

Slowly unraveling

We are tattered

Ragged

Threadbare.

Once we are frayed

We are forgotten.

We are formed with borders

But have no boundaries.

Made to please people

Yet be displeased in the fiber of our very being

My dear,

You and I

We are carpets.

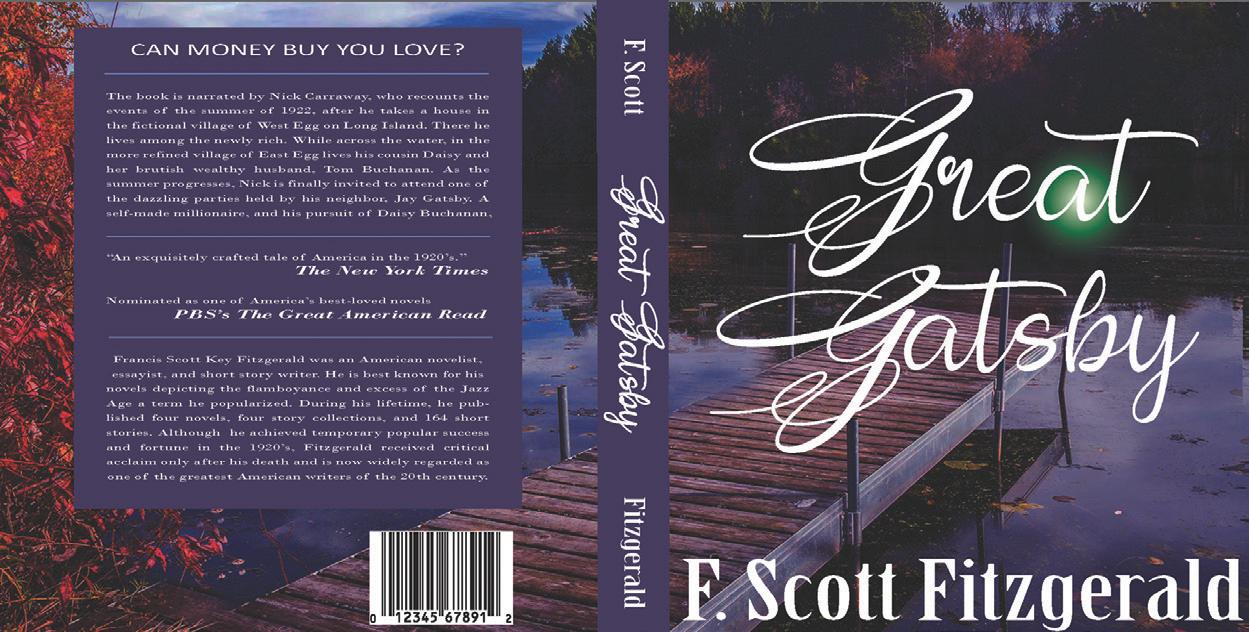

Lemony Snicket Book Covers

Lemony Snicket Book Covers

i’ve always been a commodity— a good placed on the market though i’ve never consented to being sold and consumed he wants my rack on a shelf, my hips on a line, my thighs on a scale how much would my belly cost per pound at whole foods? behind the glass and freshly processed into quarter-inch slices, or would he sell me whole? like a turkey twice a year? would i have a badge for being pretty? like the cows that are pasture raised? ask the man behind the counter for his favorite cut and recipe, and i’ll hope that he just sold a bit of me— wrapped in brown paper and wheeled to check out perhaps he’ll get 10 cents off for being a premium member i’m now left with all of the undesirable portions, so i’ll put myself on clearance and i’ll be my own butcher, and is it really any better now that i am the seller? i’m still a good placed on the market

Tending the Flame

By Kate Polaski 2nd Place ProseHestia is the eldest of the gods and the youngest of her siblings. She is the firstborn of their mother Rhea but last regurgitated of their father Kronos, which seems to be enough for her three brothers and two sisters to grant themselves seniority over her.

It’s not as though she ever lets them know it bothers her. Hestia never lets anything bother her, at least not out loud. She may bite into the side of her mouth until it swells up, clench her fingers into her fists so hard the skin breaks open, but she never utters a sound. This is perhaps why her “eldest” brother Zeus is not expecting any resistance from her when he visits her in the kitchen one day and suddenly decides to try and upend her entire life.

“I have something I must speak to you about, sister,” he begins slightly awkwardly. He has to bend down to fit through the door, and when Hestia turns her head to look at him, his large muscular form seems comedically out of place in her little kitchen.

“What is it?” she asks, continuing to stoke the flames as Zeus attempts to wedge himself between shelves behind her. Once he’s somewhere close to comfortable, he clears his throat, which she takes as a request to turn around and give him her undivided attention. She obeys quickly.

He waits to speak until she meets his eyes. “I have had two requests for your hand in marriage,” he tells her proudly. “One from our brother Posideon, and one from my son Apollo.”

Hestia freezes where she’s standing and accidentally lets her poker fall into the fire.

“And as a kind and just older brother…” Hestia grimaces at the language but Zeus doesn’t notice at all, “I have decided to allow you to choose which you will accept.”

The normally comforting scent of bread in the fire has somehow been pushed away, and Hestia misses it

dearly. Instead, Zeus has filled the room entirely, down to the very air, which now carries the energy and smell of an upcoming thunderstorm.

“They will both be visiting Olympus tomorrow to hear your decision. I suggest that you think it over this evening.” He says “suggest” in a tone that implies that his statement is anything but. Then he ducks back out of the room without a goodbye, and, as always, without waiting for a response.

Once the heavy falls of his footsteps fade away, Hestia allows herself to move again. She does not collapse to the floor and bury her head in her hands, although she would very much like to. She does not scream in frustration or beat her fists against the wall, although she wants to do that perhaps even more. Instead, she simply bends down to pick up her fire poker and resumes her bread baking, allowing herself to melt into the background, a skill so well-practiced at this point that she can melt out of even her own consciousness. She focuses all of her energy and thought on the fire, until it is all she sees. All she hears. All she feels. It burns in front of her and is reflected in her eyes as well as in her heart. At that moment she feels so connected to it that she cannot help but reach out to touch.

The fire does not burn her skin as it creeps its way up her arm and around her shoulder, but it does tickle, like thousands of tiny harmless explosions. A snake of fire circles several times around her head before sitting on the crest of her ear like a decorative cuff. It feels almost like a companion, or a pet, and Hestia, again, cannot help herself. She closes her eyes and thinks very hard, asking the fire what there is to be done about Zeus’s decision.

You are a goddess, the flame whispers in her ear, the eldest of all the goddesses. You cannot be compelled to take any action against your will.

Hestia shakes her head, trying to throw the rebellious thoughts from her mind, but the fire burrows deeper

into her, through her ear and down her throat, before settling in the pit of her chest and beginning to burn.

You must remind them who you are, it says. Hestia nearly scoffs at that. She doesn’t know what that could mean. She has no idea who she is.

You are the goddess of the hearth, the flame tells her, you wielded me before any other. Before it was even an idea in Prometheus’s mind to send me to mankind, you were already my master. You are equal parts scorching and nourishing, just as I am. But you must embrace the wild blaze as well as the gentle cookfire. You are a fire, Hestia. And you must let them see you burn.

The voice fades away, but the heat stays, dancing painfully around her insides. This time, Hestia really does collapse to the floor, and she stays there for what feels like hours before she can move again.

That night, her sisters barge into her chambers without knocking. Hestia, ever the gracious hostess, sets down her weaving, tamps down the raging inferno inside her, and offers them both ambrosia and nectar.

“We heard the news,” says Hera, throwing herself down onto a cushion enthusiastically. “Do you know whose proposal you want to accept?”

Hestia shakes her head slowly, unsure of what answer her sisters will want to hear.

“We assumed you wouldn’t have,” Demeter says, sipping from her goblet with more grace than either Hestia or Hera ever seem to manage. “You’ve always been so afraid to make choices that might offend someone. So we came to offer our advice.”

Hestia ignores the condescending tone and hopes she might actually get something useful out of this encounter.

“We are, of course, more experienced and worldly than you,” says Hera, preening so thoroughly that Hestia is reminded why peacocks have always been her favored creature.

“Yes, yes, of course,” Demeter agrees, and Hestia decides that flowers are no less self-aggrandizing than peacocks. “It would be shameful of us not to bestow some of our well-earned wisdom on our youngest sister.”

The nectar sours on Hestia’s tongue and the flame in her chest billows, begging to rise up through her

throat and come out, blazing and furious. She resists it, forcing her fingernails into the familiar half-moon indents in her palms as she seethes internally. As usual, neither of her sisters notice anything wrong, and Hestia can hardly blame them. It’s not as though they’re aware of how she speaks when things are normal. She hardly ever speaks unless it is to keep the fragile peace between her siblings, or to ask what dish they would like her to prepare for the next feast, or to whisper small, meaningless encouragement whenever they come to visit her and complain about their newest least favorite mortal of the week.

“In my opinion,” Demeter continues, “a good marriage is like a garden. It has to be tended—weeded and watered and all those things—but no matter how much effort you put in, it won’t matter if you started on poor soil.”

Hestia and Hera both blink at her, confused.

“The husband is like the soil,” she explains, “so you must choose the right one, or else your marriage will suffer. Like the garden on rocky soil.”

“I was going to say it’s like buying a bull at the market,” adds Hera, unhelpfully. “You should go for the prettiest and strongest-looking one, because you want the calves to have the characteristics of their father. If you pick a weak and ugly bull, you’ll have weak and ugly calves.”

Hestia is remembering very quickly why neither of her sisters is married yet and also why she never asks their advice on anything. She also tries her hardest to ignore her disgust at the idea of being bred like a cow or tended like a garden, but her stomach churns hard enough that she sets her nectar down with finality. The flames aren’t helping either, licking painfully at her sides from the inside, trying to spur her into action.

“I’m putting my support behind Apollo. I doubt you’d be very happy living underneath the sea,” says Demeter reasonably. “You enjoy cooking and watching the fire too much. And Apollo is much more handsome,” she adds.

“But Posideon is more trustworthy,” argues Hera. “He wouldn’t be entirely faithful, of course, he’s still a man,

continued on page 42

but I’d believe in his loyalty over Apollo’s.”

“Which do you prefer, Hestia?” Demeter pressures her. “You’ve hardly said a word this whole time.”

“I don’t like either of them all that much,” Hestia mutters. “Not for a husband, at least.”

“You’ll just have to decide which is less objectionable to you, then,” Demeter shrugs.

“What if I don’t marry either of them?” Hestia asks.

“Oh, darling Hestia,” laughs Hera, “you are simply too naive.”

Hestia forces herself to smile self-indulgently and then sinks back into her body, staying silent as her sisters continue to debate the merits of one fundamentally undesirable man over another. She sits, turning a choice over and over again in her mind like a well-roasted pig on a spit, but she does not share it or ask for any further advice on the matter. Inside her chest, the fire roars.

She returns to Olympus the next day when she is summoned.

“Sister Hestia…” Zeus spreads his arms in a playacting moment of welcome, smiling at her in the way he only does when other people are watching. “Thank you for joining us.”

Hestia says nothing, because the only words coming to mind all revolve around having no choice in the matter.

“Who will it be, then?” he asks jovially, smiling to himself, no doubt at the idea of the tribute he will receive from whichever man Hestia chooses. The two men in question are standing on either side of Zeus’s throne, each trying to catch her eye and get a hint at her decision. She has no doubt that neither of them has even considered the decision she’s actually going to make.

She takes a deep breath. She gives both of the men one final glance, wondering if she could ever truly be happy with either of them. Apollo flips his hair and gives her what he clearly thinks is a charming grin. Poseidon’s smile is more gentle, but the look in his eyes still tells Hestia that he already thinks he’s won. And that she is the prize. For a moment, in his eyes, she sees her potential future play out. Whoever she marries will expect her to become a gentle, acquiescing wife, just as she has always been a gentle, acquiescing sister. The kind of wife that takes the last seat at every table and

sits quietly by the hearth on those all-too-frequent occasions when the host has forgotten she would be coming and not laid out enough chairs. The kind that stands in the background of every party, calmly nibbling at ambrosia with whichever minor goddess or nymph has had the fortune to be invited this time but lacks the courage to actually speak to anyone. The kind that lets her husband galavant all over the earth and heavens, taking up with any mortal he deems fit, but never saying a word about it even as all the other Goddesses whisper behind their hands with false pity. She can hear it now:

“Poor, dear, Hestia. But really, what did she expect? Gods will be Gods, you know. And it wasn’t likely that she’d be the kind to keep a husband loyal, what with the way she practically disappears into the background of every room she’s in. Still, one does pity her.”

The flame in Hestia’s chest snarls like an untamed dog at the idea, ready to leap out and bite. She attempts to speak, but at first, no words come out of her mouth. All the men smile at each other, shaking their heads fondly, like she is a young child who’s come before them to share a song she’s written but forgotten the words to. She coughs a few times and forces her voice to work, for once, in the moment that she needs it the most. “I do not wish to marry either of them.”

Confusion and anger ripple across Zeus’s face. He does not ever expect defiance, much less from Hestia, who he thinks of as a submissive baby sister. “What?” he growls, clearly expecting swift repentance.

Hestia forces her eyes up off the ground where they’ve been fixed and meets Zeus’s gaze. She hopes they are glowing with the same fiery rage she feels but cannot express. “I said that I do not wish to marry either man.” Her voice shakes a bit but she carries on

Oh, darling Hestia,” laughs Hera, “you are simply too naive.” Hestia forces herself to smile self-indulgently and then sinks back into her body, staying silent as her sisters continue to debate the merits of one fundamentally undesirable man over another.

anyway. “I want to remain unwed. Permanently.”

“That is not one of the options I gave you,” Zeus warns, fists clenched on the sides of his throne. Apollo and Poseidon shoot raised eyebrows at each other, more bewildered than angry.

“I am aware of that. However, if you allow me to do this,” she begins, bristling internally at the idea that she requires her younger brother’s permission to retain her so-called freedom, “I will stay a maiden forever. I will tend the hearth here in Olympus every day,” she continues, gesturing to the fire which has sunk down to the embers, clearly having been left unwatched. A ripple of empathy for a kindred spirit rushes through her, encouraging her to go to it, brush away the ashes and shake the kindling until it reignites, but she resists, knowing that will weaken her in Zeus’s eyes. “I will collect offerings and cook meals, and perform any other duty required of me. All that I ask in return is that my maidenhood be respected.”

Zeus’s mouth pinches dangerously, but Hestia can tell he’s considering her words. As he frowns in thought, Hestia allows herself to smile, just a bit, and the flame in her chest purrs. She does not need to stay here and wait for Zeus’s decision because she already knows what it will be. One of the advantages of staying quiet and unobtrusive at the back of every room you’re in is the ability to observe others in their natural state, and Hestia has been watching Zeus rule Olympus for what feels like (and probably has been) eons. She has seen his mind in action countless times and knows that it is a simple and selfish little thing, like that of a toddler dictating the rules of a make-believe game. When given the choice between giving something away to be used by someone else and keeping it for himself, Zeus will always choose the latter. And in this case, it just so happens that Hestia is that thing he wants to keep. He has never realized this before, because he has never considered a world in which Hestia is not there by the hearth at all hours of the day to cook him something whenever the whim takes him. He has never thought about how much colder his life would be if he forced Hestia out to tend the hearth of another man’s household. It has never even occurred to him what it would be like to have to cook his own meals, fetch nectar for guests himself, or return dutifully to the flames every half hour

to ensure that they are well cared for. Zeus is just now seeing these things in his mind’s eye for the first time, and he hates them. He hates them all with a childish and egotistical passion, but hates them all the same, just as Hestia hates them, which means that she can use that feeling to coax him over to her side. She can kindle the fires and send them crawling up just the right spot in Zeus’s cavernous chest to make him bend to her will without even realizing he’s acting for anyone’s benefit but his own.

Just one last push, she knows, one adjustment of a log here and a small puff of air there, will do it, taking the small flame to a roaring inferno, and Zeus will send the suitors away in a self-righteous fury, berating them for ever trying to deprive him of the service and presence that is his to own by birth. This is an idea that Hestia will need to disprove at a later date, but she is nothing if not patient.

“And besides, it would be a grievous error of etiquette to be married before either of my elder sisters,” she adds, before turning and walking out of the room, head held high, the fire finally satisfied and licking happily across her ribs as though they are dry wooden planks. They want her to be young? Very well. She will be young forever, then. She will run through meadows, skimming the dewy grass with her bare feet. She will bathe in rivers with nymphs and climb trees without worrying about dirtying her dress. She will sit by the hearth and listen, wide-eyed, to stories from traveling poets. And most of all, she will never ever marry. She refuses to be a bargaining chip for her brother. Women may be bargaining chips, but it has been made very clear to Hestia that she is just a girl.

Clicker Acrylic Painting by Gracey Gurwitch

Clicker Acrylic Painting by Gracey Gurwitch

A Recipe for Housekeeping

By Chanelle Allesandre 1st Place PoetryAnyhow, it was superstitious the way the broom fell behind me from its corner as I closed the door behind me as I shut the door easily, as I do every night, and nothing has fallen on the floor before, certainly not a grey broomstick a sure omen a harbinger of guests of visitors an imminence especially under Aquarius joint, juxtaposed with the other planets knocking against Saturn’s goaty knees up in a lightless sky and I remember in my book I read that a broom falling at night meant visitors you couldn’t magic off or away, unless you had a string of potent words and herbs like gentian, quince, to sweeten the gentiopicrin, and rivina with red berries of protection to stave off uninvited spirits to tighten the boundaries around the home, uva ursi mixed with the roots of wild valeriana and stirred with the beak of a wren, preferably, with a pinch of xanthan gum to thicken it all yellow and paste-like to be buried with orange zest and left undisturbed.

The Heart of Nature

By Lauren ShawNature is beautiful. The tall, green trees surrounding me stretched upward to form a fluttering ceiling. Light shone down in shafts, a stream laughed and tumbled over rocks. I wandered across the woodland scene, breathed in the fresh air, and finally felt at peace.

I’d been so tired—consumed by work, family, purpose. Finally the haze of gray depression became too suffocating, and I had to escape. To walk in nature, to see life from a new perspective. And it seemed to be working. I escaped the clutches of darkness just in time.

Choosing a walk in the woods to relax was a no-brainer. My childhood was filled with nature; I’ve been making connections with the earth since I can remember. Countless camping trips, hikes with my family, visiting the lake in the summer and exploring the woods surrounding my house. But when I reflected on those times they seemed so far away, lost in a forgotten time of innocence. A time when I still had wonder. I wanted to reclaim it, open myself back up to the energy of nature. So I set off and watched the trees stretch up, up, and around my small shadow.

As I passed by rocks and wild formations of brush, shallow indentations appeared in the soil around me. Small, slight, like the footprints of a child. I imagined ghost children, invisible save for the soft earthen markings of their feet, running through the forest and settling in the treetops under a pale silver moon. See, you are already becoming more creative and fluid with the world around you. There is nothing to escape anymore. Only the here and now.

In my path ahead stood a large oak tree. I had encountered many trees so far, but this one drew me in with magnetic appeal. It towered against the sky with branches reaching into the clouds. Emerald leaves crowded its limbs, occasionally drifting to the ground

A single phrase filled my mind. Go on and you will see. I was startled. Not because of the thought’s content but because it was not my own.

below when a breeze tempted them down. It looked wise, powerful, and omniscient, an ancient god of growth transplanted and reborn as an oak. I laughed at myself, catching the ridiculous nature of my thoughts. As a young boy my mother told me that some trees had power, that they were supernatural forces reincarnated and trapped behind massive bark trunks. Looking at this tree, I felt compelled to believe her. Obviously the forest was making me back into the superstitious little boy I longed to reconnect with. Tell me, magnificent tree, I thought flippantly, what insight should I carry back to my life outside your forest? What should I tell the world of your power?

A single phrase filled my mind. Go on and you will see. I was startled. Not because of the thought’s content but because it was not my own. It was as if someone had planted the seed of an idea in my mind and in a split second the thought had grown and tried to disguise itself as my own. Go on and you will see. The idea wasn’t that unpleasant. It was not a command, but a suggestion. Filled with a willingness to venture further away from my mundane life, I followed. I am truly one with nature now.

Guided by a strangely compulsive force, I started to trace a path deeper into the forest. I enjoyed the breeze on my face, even though it seemed to have adopted a cunning chill I hadn’t noticed before. Was I really making the right decision to go off into the woods alone? Relax, I told myself, what are you so scared of? You know this world; it has been a part of you since childhood. You are safe in nature; it cannot hurt you.

A sudden drop in the path startled me, and I tumbled to the ground, catching myself with my hands on a patch of grass. Instead of a soft landing, I felt a stinging pain as soon as my hands made contact with the ground. Turning them over, I discovered to my horror that they had been sliced in long, jagged stripes. The tiny green blades had torn lines of blood into my soft flesh, stinging, angry, and red. I had never known simple grass to be so destructive, so cruel.

You need to clean them, the voice in my head claimed, and I moved in anguish, trudging along until I reached a small pool of stagnant water. I stepped into the soil around the pool, dropping my hands into its cool shallows. Crouching down, I stared up at the clouds above and watched them race across the sky as if they were desperately fleeing from some larger force.

Satisfied as the stinging in my hands subsided, I pulled them out of the water and tried to step backwards— but stopped halfway. I couldn’t move. The ground and dark silt of the pool were holding me down, holding me around the ankles in its depths. The more I struggled to step out, the more I sank. Quicksand. Sand quickly grabbing, pulling, drawing me down into dark depths. Asleep underground. Breathing in dirt, lungs filled with grainy mud. Lost. How can I go on and find out the message of the tree? You must go on, said the tree. Go on and see; you must you must you must.

Release. The sand seemed to let go, surrendering its grip suddenly and completely. I took the chance nature had given me and hurriedly stepped out of the grip of the pool.

You are not ready yet. One more path to take, one more face to meet. Go on and you will see.

Feet covered in black sludge. No memory of why I’d taken on this trek. Reclaiming…someone? Lost in time, my younger self? He did not matter anymore, all that mattered was finding the tree.

Sun sinking below the hills, drowning in darkness, last breaths of red light bathing treetops. Even the sun cannot survive here. The tree the tree the tree. The tree. The tree. The tre—

The tree. There it was, the same but different. A mass of twisted, confusing branches. A near twin to the ancient oak, but this tree was dark and gnarled,

not green and full of life.

I had arrived. What should I do? I knew this was my final destination, but I didn’t know why.

Come inside, it whispered, scratchy and low. Come and join with nature. Step by step, I moved closer. There was a thin crack in the dark wood of the trunk, tracing its way to the limbs above. What’s inside? What’s inside? I reached out curious hands and pried back the bark, splitting the crack in the tree and revealing its insides.

Deep horror coursed through my veins, freezing my blood and muscles. A scream died in my throat. It was a body. Not a skeleton of some forgotten soul—no, far worse—the tree itself was a body, and I had exposed its internal organs. Gnarled wooden bones of a rib cage, twisted roots that formed intestines, grotesque fungus grew into a spine. Vines tangled into ligaments, seedpods inhaled as lungs, and moss breathed as pores on the tree’s outer bark-like skin. It was alive, in the most chilling way a human mind could imagine. Looking to the left-center of the tree, I noticed a large hollow space. Where is it, I pondered through a haze of terror. Where is the heart?

A thought began to creep its way into my head. It’s the only way. I have to. How else could I become the true heart of nature? Slowly, I stepped into the opening, into the crevice, and pulled the bark-skin back into place.