Weathering a Storm

Chabad Shluchim care for their communities in the wake of

ISSUE 25

CHESHVAN 5785 NOVEMBER 2024

6 7 8 10 15 22 28

From the Publisher

Editorial I Mica Soffer

Going in Yaakov's Way

A letter from the Rebbe

Beyond the Ballot

Rabbi Yehuda Ceitlin

Weathering a Storm

Tzemach Feller

5 of the Rebbe's Battles

Chava Butler

Israel's Spy in Lebanon

Mendy Kortas

25-Year Shlichus and Beyond

Dovid Zaklikowski

Ain't Gonna Box on Saturday

Chaya Chazan

After Tishrei

JEM gallery

The Spark of the Soul

Health I Rabbi Daniel Schonbuch

Chinuch Matters

Mushka Cohen I MEF

Candlesticks for a Dollar

Story I Rabbi Shlomo Schwartz OBM

The Inside Track

Music I Sruly Meyer

Kids Korner

Fun I Sari Kopitnikoff

Mabul Suncatcher

Activity I Parsha Studio

Fabulous Fall Flavors

Food I Sruly Meyer

You're Not Invited

Humor I Mordechai Schmutter

862 Eastern Parkway

Then & Now I Shmuel Blesofsky

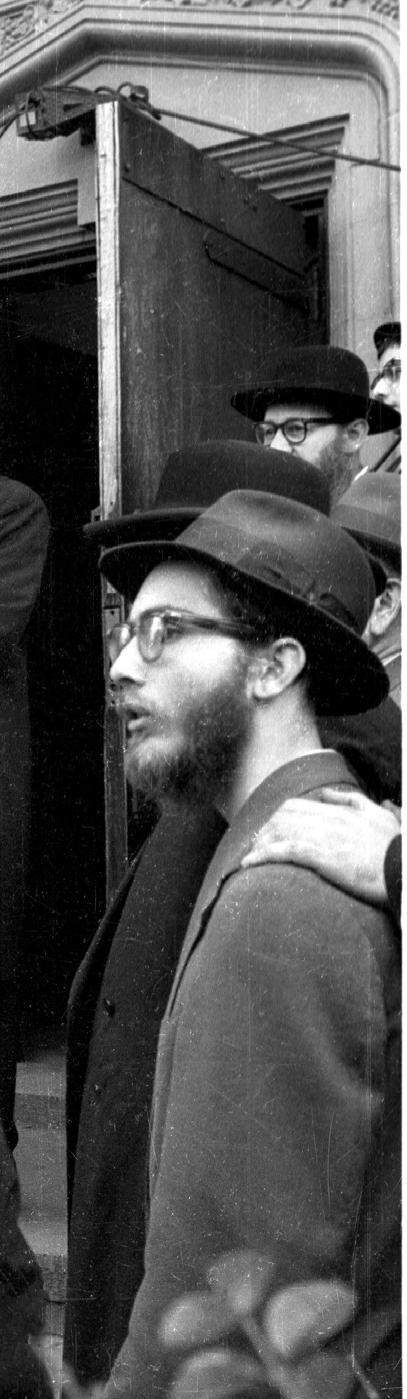

Rabbi Zalman Fischer, Director of Chabad of Augusta, Georgia puts on tefillin with a National Guard official who is Jewish in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene that struck in late September.

Publisher

Mica Soffer

Editor

Rabbi Yehuda Ceitlin

AssociateEditor

Mendy Wineberg

ContributingWriters

Shmuel Blesofsky

Chava Butler

Chaya Chazan

Mushka Cohen

Tzemach Feller

Sari Kopitnikoff

Mendy Kortas

Sruly Meyer

Daniel Schonbuch

Mordechai Schmutter

Dovid Zaklikowski

Design Sheva Berlin

PhotoCredits:

JEM/Living Archive

Shalom Burkis

Aharon Gellis

Dovber Hechtman

SpecialThanks

Kfar Chabad Magazine

ADVERTISING ads@COLlive.com

718-427-2174 ext. 2

EDITORIALINQUIRIES ORSUBMISSIONS

Editor@COLlive.com

718-427-2174 ext. 1

SUBSCRIPTION

To receive a printed copy of the magazine (U.S. addresses only): COLlive.com/magazine

COLlive Magazine is published in print and online periodically by the COLlive Media Group Inc. and is distributed across the United States. COLlive does not endorse any products or services reported about or advertised in COLlive Magazine unless specifically noted. The acceptance of advertising in COLlive Magazine does not constitute a recommendation, approval, or other representation of the quality of products or services or the credibility of any claims made by advertisers, including, but not limited to, the kashrus or advertised food products. The use of any products or services advertised in COLlive Magazine is solely at the user’s risk and COLlive accepts no responsibility or liability in connection therewith.

FROM THE PUBLISHER

In what felt like the blink of an eye, another beautiful Tishrei in Crown Heights has come to an end. As the once-crowded streets begin to empty and we return to daily life, I feel a bit of sadness that the joyous season—hectic and sleepless as it may be—is over.

One of the most beautiful events we enjoy each year is the Simchas Beis Hashoeva on Kingston Avenue. I attended it as a child, and now I love bringing my family to experience it.

But this year, as I stood watching, I had a sudden realization that astounded me—how had it taken me so long to notice?

I saw a group of young Chassidishe bochurim ("Poilishers") who had come from Williamsburg or another neighborhood, dancing together with their long payos and shiny coats swinging.

Nearby, in another circle, danced a group of Jewish boys of the same age yet from a different background. They wore yarmulkas clipped onto long hair, baggy clothes, and sneakers. The two circles danced side by side, seemingly worlds apart.

Suddenly, one of the Chassidishe bochurim broke away from his circle and grabbed the hand of one of the teenagers, dancing to the sound of the pulsating, joyous, Chabad niggun. Soon, a Lubavitcher bochur joined them, forming a circle of Jewish unity.

After a few minutes, as they were about to go their separate ways, the Chassidishe bochur embraced one of the teens in a huge hug, both of them smiling with the genuine, simple love of two fellow Jews.

At that moment, I felt as though my eyes had been opened. After all these years, I learned yet another reason the Rebbe instituted and encouraged this annual event, organized with great devotion and self-sacrifice by R' Yisroel Shemtov for decades.

Without this event, these two souls might never have met, much less connected in such a unifying way. I could only imagine the joy it brings Hashem to see His people united like this—thousands of individuals of every background joining together every night of Chol Hamoed, year after year.

Standing there on Kingston Avenue, I said to myself, thank you, Rebbe.

May this Achdus continue throughout the year.

MICA SOFFER

Dvar Malchus

Going in Yaakov’s Way

Carrying the Inspiration from Tishrei into the Year

Rosh Chodesh Marcheshvan 5743. Brooklyn, N.Y.

To the Sons and Daughters of Our People Israel, Everywhere, G-d bless you all!

Greeting and Blessing:

Coming from the month of Tishrei — the seventh month in the order in which the months are counted, beginning with Nissan, but the first month and “head” of the new year, as indicated also in its name

— ירשת (Tishrei), the same letters as תישאר (Reishit), “beginning” or “heading” (תישאר — without the aleph as it appears in the Torah),

The seventh month — שדח יעיבשה — is a month “which is satiated with, and satiates an abundance of good to all the people Israel throughout the year” (עבש — from the word עבש — “plenty”); plentiful with festivals and special days, and satiated with awe of G-d and love of G-d, joy of Mitzvos, and topping it with Simchas Torah, and replete with all blessings in general. It is the month that animates and inspires in the fullest measure all the coming months and days of the year, down to the areas of actual doing, namely, learning Torah and doing Mitzvos, since “action is the essential thing.”

Therefore, coming from this auspicious month, and taking into consideration the familiar saying to the effect that “as one prepares himself for the journey, so one proceeds,” which is associated

with the well-known custom of proclaiming on Motzei Simchas Torah, “and Yaakov went on his way.”

Meaning that inasmuch as a Jew, every Jew, is, of course, a member of Kehilas Yaakov (the Community of Yaakov), is now about to set out on “his way,” going into the “ordinary” months of the year that are not “abundant with festivals,” but are largely taken up with matters of Parnossa and mundane affairs, this is the time to remind him that “his way” is the way of Yaakov as it has been designated by Hashem, namely, the way of G-d, the way of “All your actions should be for the sake of Heaven,” as behooves a descendant of Yaakov Sava, “Zeida Yaakov.”

Considering further that although all Jews have the same task and purpose in life — complete dedication to the service of G-d, as our Sages expressed it: “I was created to serve my Creator,” yet, coming down to actual conduct they are divided into three categories: men, women, and children (of pre-Bar-Mitzvah and pre-Bas Mitzvah age). Hence, this is reflected in the resolutions which have been adopted by them respectively, during Tishrei for the entire new year.

In light of all above, and also in view of the fact that a resolution made jointly by several persons, and more so by many people, in congregation, is more certain to be carried out with greater hatzlocho and in the fullest measure by each one, man and woman, I take the liberty of making the following suggestion and request,

hoping that it will be acted upon: It would surely be “right and proper and good and fitting” that “the heads of the people together with the tribes of Israel” everywhere gather together as soon as possible — men separately, as well as women and children separately (the children under their respective Madrichim and Madrichos, of course) in order to reaffirm and, especially, to decide upon the proper ways and means of carrying out in actual reality and in the fullest measure, the good resolutions which each had made during the auspicious month of Tishrei, beginning with Rosh Hashono and in the propitious subsequent days, as well as to supplement those resolutions, if necessary.

To conclude with blessings: May Hashem grant Hatzlocho that the Kesivo v’chasimo Tovo and Gmar Chasimo Tovo which everyone, in the midst of all our Jewish people, received in the month of Tishrei, should materialize in the fullest measure, in the kind of good that is revealed and obvious, throughout the coming months and days, bringing good and blessing to us and all our people, to the extent of “open wide your mouth (state all your desires), and I shall fulfill them,”

And soon indeed bring the realization of the main and essential blessing — the true and complete Geulo through Moshiach Tzidkeinu.

With esteem and blessing for Hatzlocho and for good tidings.

Menachem Schneerson

By Rabbi Yehuda Ceitlin

BEYOND THE BALLOT

Two presidential candidates presented starkly different outlooks on the delicate U.S.-Israel relationship. One candidate held a pragmatic yet ultimately firm stance in support of Israel. The other candidate also supported Israel’s right to exist but took a more critical approach.

In Israel, failed leadership had led to an early October surprise assault on its borders, resulting in high Jewish casualties. After the attack, Israel regrouped and embarked on a protective and defensive battle against its Arab enemies on multiple fronts.

Does that sound familiar?

If it does, it might be because you were alive in 1972 and remember that incumbent Republican President Richard Nixon faced Democratic Senator George McGovern in that year’s General Election. Not long after Americans re-elected Nixon, Israel was attacked by its enemies during the Yom

Kippur War, on October 6, 1973. (We all know today that what is happening in Israel is not our first rodeo!)

As troops amassed and rhetoric escalated in the run-up to that war in 1973, the Rebbe called on Jewish children worldwide to gather and pray, invoking Tehillim 8:3, “lehashbis oyev - to neutralize the enemy.” The Rebbe wrote to Jewish people worldwide that spiritual strength is gained by following Hashem’s commandments.

Behind the scenes, the Rebbe urged Israel’s leaders to take preemptive military action. Despite their not heeding his call, when the war broke out, the Rebbe didn’t say, “I told you so.” Instead, he instilled hope, encouraged the IDF, and comforted the families of fallen soldiers.

One more obvious step—as the rumblings of war increased in the summer and fall of 1972 before the war—would presumably have been for the Rebbe to endorse the

presidential candidate who would be most supportive of Israel. But the Rebbe didn’t do that. He did not endorse a candidate in that election, or in any election before or after, even when crucial issues were at stake.

Why?

In the Rebbe’s own words, “It is well known that neither I personally, nor the Lubavitch movement, take a public stance in any election to any office, which is a policy of long standing.”

That comment was written a few years later, on the 19th of Tamuz, 5740 (July 3, 1980), to Susan Devora Alter, a New York City Councilwoman representing Borough Park. “It, therefore, surprises me how you could have received any impression contrary to this established policy,” the Rebbe added to her.

Councilwoman Alter—a frum, sheitel-wearing woman who was

married to a Five Towns rabbi— was in a Democratic primary against a young politician named Chuck Schumer for the vacated Congressional seat of Elizabeth Holtzman.

In that race, Schumer enjoyed the support of the Jewish community of Crown Heights. My wife’s late grandfather, R’ Mendel Shemtov, a founding member of the Crown Heights Jewish Community Council, was in regular contact with him throughout.

Schumer’s supporters had stopped the “reapportionment” to divide Crown Heights into neighboring voting districts—a plan the Rebbe strongly opposed, as it would diminish the community’s local voting power. Crown Heights was now returning the favor.

The day after winning the race, Schumer called the Shemtov residence. R’ Mendel’s wife, the outspoken Sara Shemtov, answered the call. She congratulated him

on his win and then cynically commented, “Now that you’ve won, you’ll forget us.”

Schumer, who today serves as the U.S. Senate Majority Leader, promised her that that wouldn’t happen—spoken as a real politician. We’ll let history judge whether that was true.

But the greater lesson here is that the Rebbe drew a clear distinction. The Rebbe went to vote and encouraged Chassidim to do the same as part of our civic duty.

Crown Heights—as a neighborhood—supported a candidate.

Chabad-Lubavitch—as a movement, representing the Rebbe—did not.

As a movement, we have never shied away from engaging with public officials—from presidents on down—of all parties. We have never shied away from advocating for policies we feel strongly about; things like a Moment of Silence

in schools or criminal justice reform. We have never shied away from engaging in our civic duty— indeed, we take pride in voting and encouraging others to do so.

But we never, ever endorse a candidate because that isn’t Chabad’s task.

It feels like these long-impenetrable lines have been blurred, if not crossed, in the 2024 election cycle. I am thankful it is (finally) behind us, regardless of whom you were rooting for. Let’s continue participating in politics, but let’s maintain the “policy of long-standing” that, as a movement, Chabad does not take sides.

Rabbi Yehuda Ceitlin, Editor of COLlive. com and COLlive Magazine, is the outreach director of Chabad Tucson, and Associate Rabbi of Cong. Young Israel of Tucson, Arizona. He coordinates the annual Yarchei Kallah gathering of Chabad Rabbonim and Roshei Yeshiva

By Tzemach Feller

When the Rivers Rose

How Chabad Shluchim cared for their communities in the wake of hurricane devastation

Twice Tested Punta Gorda, Florida

Hurricane Helene wasn’t supposed to hit Punta Gorda, Florida at all.

At least not as a hurricane. It was supposed to pass by as a tropical storm; maybe whipping around some outdoor furniture and giving local lawns a good soaking. But Helene brought with it a tremendous storm surge. On September 26, for the first time in nearly a century, a 6-7 foot surge inundated the low-lying coastal community off Gasparilla Sound in southwest Florida.

“The entire downtown Punta Gorda flooded, homes flooded, businesses flooded,” Shlucha Shaina Jacobson described. “And we had a foot of water in our garage and four or five feet of water in the front of the house.”

By the following morning, the Jacobsons were unable to leave their home because of the flooding. “Then we found out that our Chabad House was completely flooded as well.”

The Jacobsons had bought the 9,000-square-foot old Punta Gorda Library in 2022 to serve as the new home for Chabad of Charlotte County, which they direct. As their community grew, so did the programs the Jacobsons offered. This fall, they launched Tamim Academy of Punta Gorda—a brand-new branch of the burgeoning Chabad-led Tamim Academy network of schools.

Now it was underwater.

And just when things couldn’t get worse, early Shabbos morning, they did. The Jacobsons’ electric lawn mower was stored in the garage, and as floodwaters seeped into its lithium battery, the destabilized device exploded, and the garage caught fire.

“Baruch Hashem, we all got out in time, and firefighters extinguished the blaze,” Jacobson said. But the damage was monumental.

But rather than bemoaning their ruined home and flooded Chabad House, the Jacobsons swung into action. “We have been reaching out to see what help people need; reaching out to elderly people to see if they’re ok.”

The Jacobsons mobilized community members to help those in need, and helped distribute aid to others whose homes had been ruined by the storm. And they were determined to host High Holiday services at Chabad, come what may. Crews tore out the flood-damaged flooring, trying to repair as much damage as possible ahead of Rosh Hashanah, which was days away.

It wasn’t perfect—the bottom foot or two of drywall on walls throughout the building had to be removed to ensure there wasn’t mold, and signs

of renovation were everywhere—but Chabad hosted a beautiful Rosh Hashana dinner in the Chabad House, despite everything.

Repairs continued as Yom Kippur approached, with the hope of making the shul more presentable in advance of the holiest day of the year,

Then Hurricane Milton hit.

Once again, floodwaters surged into the city. The Chabad House, which they had just begun restoring, suffered tremendous damage. School furniture was smashed, ruined, or simply floated away. The community was devastated for a second time in three weeks.

And still, the Jacobsons vow to rebuild.

As they do so, their Jewish brothers and sisters are coming to their aid. “They had thousands and thousands of dollars of new school furniture, and a lot of it was ruined,” said Rabbi Shloime Denburg, the Director of Development at Lubavitch Hebrew Academy (LHA) in South Florida. “We’re going to send them extra school furniture to help them replace what they had.”

It’s a story that has echoed up and down the Eastern Seaboard in the wake of two devastating hurricanes this autumn.

That same Chabad House in Punta Gorda, Florida, days later, as the community prepared for Rosh Hashanah. A week later, it would be flooded again.

The flooded-out Chabad House in Punta Gorda, Florida

Unity Amidst the Rubble Augusta,

Georgia

In the early hours of Friday morning, September 27, Hurricane Helene took an unexpected turn. Its destructive eyewall smashed through Augusta, Georgia, and within an hour, power and cell phone service had been knocked out in many areas. “The place looked like a war zone,” Rabbi Zalman Fischer of Chabad of Augusta described. “You couldn’t get out of most neighborhoods because trees were all over the roads.”

Many were trapped in their homes by fallen trees and debris. Half the city lost access to fresh water. The Fischers’ own home was relatively unscathed. But the Chabad House was hit hard. Four trees fell on the shul building, rendering it unusable.

That Shabbos, services went on at Chabad’s other building—without power, in the sweltering heat. “We got together, we davened, and we got strength from each other,” Rabbi Fischer described. The shluchim began visiting people to ensure they were safe. After the city announced that power and other services would likely not be restored for more than a

Smiling through the pain. Rabbi Zalman Fisher of Chabad in Augusta, Georgia puts on tefillin with a fellow Jew as the long task of rebuilding begins.

Stranded but Supported Asheville, North Carolina

Asheville, North Carolina is more than 2,000 feet above sea level and hundreds of miles from the nearest coastline. But when Helene blew through, the city saw a twoday record of nearly ten inches of rain, and the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers rose more than 20 feet—higher than they had ever risen in recorded history.

Landslides and flooding cut off the city by road for two days, and power, drinking water and cell phone service were lost almost everywhere.

On Motzei Shabbos Slichos, as most Lubavitchers were looking for a farbrengen, Rabbi Bentzion Groner of Chabad of Charlotte was looking for a helicopter. Unable to call or WhatsApp the Asheville shluchim— Rabbi Shaya and Chana Susskind— he finally got through via iMessage. Chabad of Charlotte had collected tons of supplies for their beleaguered sister community some 125 miles to the west, but the roads were all but impassable. Then another problem emerged: even if Rabbi Groner were to locate a helicopter not already in use for search and rescue or other critical needs, its payload would be far too restricted to bring enough of what Asheville needed: fresh drinking water.

So Rabbi Groner got into a Sprinter van loaded with supplies—and as much drinking water as they could carry—and set out on the hazardous trek to Asheville, on roads he wasn’t sure would be open. Many hours later, he made it to Asheville on justreopened roads. Dodging broken tree limbs and flooded-out roads, he made it to Chabad of Asheville, where the Susskinds began distributing the much-needed aid to locals in need. Groner drove back

home, loaded the van again, and turned back around for another trip to Asheville.

At Chabad of Asheville—which was largely spared from the devastation that had swept through much of the city—a massive rescue and aid operation got underway. Frum paramedic and search-and-rescue groups streamed into the city, creating a tremendous Kiddush Hashem.

The crisis management organization Achiezer sent a volunteer team to Asheville. They staged at Chabad, and Rabbi Susskind gave them a tour of the hardest-hit areas of town. The next day, Matzil—a Jewish search-and-rescue team—arrived and set up their command center. Chaveirim volunteers drove in from New Jersey, as did members of Community Search and Rescue from Rockland County, NY, and volunteers from Williamsburg, Brooklyn, NY.

They were far from home this Rosh Hashanah, busy rescuing trapped seniors and bringing meals and water to families in need. The Susskinds made sure they had a taste of home over Yom Tov, preparing “Hungarian Yom Tov food like their bubbies make, to give them the familiar taste they’re so used to.”

Hundreds of miles from home, they enjoyed kasha varnishkes, stuffed cabbage and honey cookies.

Meanwhile, the Susskinds had their

commercial kitchen busy around the clock, preparing hundreds of hot meals to distribute to locals, many of whom had been subsisting on canned and packaged food for many days.

“My kids loved the warm food and the friendship,” Shifra Ahlers wrote on Facebook. “Thank you, friends. We love you!”

On October 10, two weeks after Helene smashed into Asheville, Chabad “marked themselves as safe.”

“We proudly share that every single person on our mailing list, and every intake form asking for help searching for a loved one, has been responded to,” they wrote in a Facebook post. And when Sukkos arrived, it was joyously celebrated in a community that was down—but not out. A community that had seen firsthand that kol Yisroel areivim—all Jews are guarantors for one another.

The Groners of Charlotte, North Carolina, fill a van with supplies for Chabad of Asheville, North Carolina

By Chava Butler

5 OF THE REBBE’S UPHILL BATTLES

The efforts to change behaviors and wrong perceptions in Judaism

In a world of uncertainty and confusion, it can feel easy to give in to societal norms and just follow the crowd. As chassidim of the Rebbe, we have been shown time and time again that such is not our way. Throughout the Rebbe’s leadership, there were many revolutionary ideas that the Rebbe unwaveringly stood for, even if they were controversial and uncomfortable to some.

From fighting for the safety and security of Eretz Yisroel to proper chinuch for our children, the Rebbe spoke strongly and passionately, urging people to stand for what is right. Many things that are today regarded as mainstream were introduced, publicized, and cemented through the Rebbe’s encouragement and leadership. Here are 5 of them.

SHEITELS: MAKING WIGS THE STANDARD

THE ISSUE:

When the Rebbe took on the leadership of Chabad, there were not a lot of married Jewish women who covered their hair properly. Many chassidim married women who grew up in homes that were not so careful about certain aspects of Yiddishkeit, and many of the women who’d grown up in Communist Russia were lax in their hair covering.

THE REBBE’S TAKE:

The Rebbe made it very clear that halacha mandates that married women must cover their hair fully and a partial covering is not sufficient. During the years when the Rebbe would officiate at weddings in Crown Heights, one of the conditions was that

the bride would take it upon herself to cover her hair with a sheitel. The Rebbe enumerated the tremendous blessings that come along with covering the hair, not just for the woman personally, but for their entire family and her surroundings.

The Rebbe explained the difference between a sheitel and a kerchief (tichel). “It is easy to take off a kerchief, which is not the case with a sheitel,” the Rebbe wrote in a letter. “When one is at a gathering and wears a sheitel, then even if President Eisenhower were to enter the room she would not take off the sheitel. This is not so with a kerchief which can easily be taken off.”

To a woman who purchased a wig during a trip to New York, the Rebbe wrote it would “bring hatzlocho [success] to you, your husband

and children in good health and prosperity.” The Rebbe added, “Not only does the sheitel show the true Jewish spirit of adherence to our laws and customs, but it also shows strength of character and will and the power of conviction, not being swayed by external influences and the opinions of people who are rather devoid of content inwardly and even outwardly are of no consequence.”

THE OUTCOME:

With much encouragement, brachos, and effort from the Rebbe, sheitels became the standard way for women to cover their hair after marriage. Today, sheitels have become commonplace both in the Chabad community and in the greater frum community, with more and more sheitel machers enabling the observance of this halacha

The Needle and Lace Wig Salon in Crown Heights

THE LUCHOS: TWO SQUARE TABLETS, NOT ROUND

THE ISSUE:

On many Shuls, parocheses and Torah covers, the Luchos are depicted with rounded tops. But where did this depiction come from? There is no authentic Jewish source for this. A number of Christian artists depicted Moshe Rabbeinu holding rounded Luchos—including Rembrandt in Moses Breaking the Tablets of the Law; Guido Reni in Moses with the Tablets of the Law; and Raphael in Moses Presenting the Ten Commandments.

Most of these paintings date from the Renaissance era, and some are from earlier. (Interestingly, Michelangelo’s sculpture Moses depicts the Luchos as rectangular.)

THE REBBE’S TAKE:

When artist Michel Schwartz submitted a sketch in 1944 for an emblem for Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch, the Rebbe told him that the Luchos should not be drawn with rounded tops. Schwartz later said, “The familiar rounded top was introduced by Roman order, derived from their architectural style, prevalent at the time of the destruction of Jerusalem and the Holy Temple. The Roman desire to eradicate everything Jewish included even the shapes of our most holy symbols.”

On Shabbos Parshas Ki Tisa, 5741 (1981) and on Simchas Torah 5742 (1981), the Rebbe clarified that the roundtopped Luchos are not the

authentic shape—and that the earliest source for this depiction is a non-Jew in Rome.

The Rebbe referenced the Gemara in Masechta Bava Basra (14a) as clear proof that the Luchos were completely straight and square. The Luchos perfectly fit in the Aron, the Gemara describes, and so would have to be square. All the Beis Hamikdash’s vessels are made kodesh only when they are completely full—so the square-shaped Aron would have to be completely filled when the Luchos were in it, without the space that would have resulted if the tops were rounded.

THE OUTCOME:

Square Luchos have become more and more mainstream. The Jerusalem Great Synagogue, which was inaugurated in the summer of 5742, features rectangular Luchos on its facade. In 2015, Israel’s Chief Rabbinate revised its official logo—which once had round Luchos— to depict square-shaped Luchos instead.

“This is the true way it should be according to the Torah,” said Israeli Chief Rabbi Dovid Lau at the time. “This was not only incumbent upon me in my position; it is a merit for me to be the one to make this change.”

Photo Suicasmo

The Great Synagogue on King George Street in Jerusalem

ZIM LINES: CRUISING THE OCEAN ON SHABBOS

THE ISSUE:

In 1953, the Israeli shipping company ZIM launched a transatlantic passenger line, transporting people from the United States to Israel and back—a departure from their previous shorter Mediterranean routes. While shipboard travel from Europe to Israel took less than a week, the voyage from America to Israel took longer—typically two weeks—and the ship traveled on Shabbos.

THE REBBE’S TAKE:

The Rebbe, who worked on U.S. vessels in the Brooklyn Navy Yard during World War II, said that ZIM’s Jewish-owned and operated vessels were operating on Shabbos in violation of halacha.

Citing scientific and engineering principles, the Rebbe wrote to leading poskim. One of them was Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, widely regarded as the posek hador, who allowed travel on Shabbos on ZIM’s ships. ZIM claimed that systems on their ships were automated on

Shabbos, and no melacha was done.

In response, the Rebbe went into great detail explaining how even the automated systems require human input every so often (especially those days), and don’t operate a day without the need for a person to make adjustments.

The Rebbe quoted ZIM’s statement that “these ships are modern turbine-driven ships with fully automatic operational features. Actually, the duties of the engine room crew are supervisory rather than functional,” and stating that at the ships’ 18-knot speed, they wouldn’t be able to reach a European port within a week of leaving the U.S.

The Rebbe went on to say that this very statement proves the fallacy of ZIM’s claims, as “after all the pressure, they’re only writing about the propulsion systems, not the power generation systems, not about the radio communications

systems, not about the gauges, engine telegraphs, machines to serve the travelers, etc—and most of the Torah-prohibited melachos take place in these machines.”

The Rebbe also refuted ZIM’s claim that they couldn’t make port before Shabbos. “There are many islands and ports between the United States and Europe,” such as in Bermuda and the Azores.

THE OUTCOME:

The majority of the poskim with whom the Rebbe corresponded came to agree with the Rebbe’s opinion, and forbade travel on ZIM lines on Shabbos. On the margin of the Rebbe’s handwritten letter, R’ Moshe Feinstein wrote an apology for listening to people who were passengers rather than inquiring about this to the staff of the vessels. ZIM refused to alter their ships’ schedules but as air travel became more affordable, the cruise lines became less popular. ZIM phased out its passenger services in the late 1960s.

Negbah 2, on her maiden voyage on the Elbe river in Central Europe

Photo

ZIM

MIHU YEHUDI: WHO IS REALLY A JEW

THE ISSUE:

Shortly after the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, an Israeli law was passed affirming the inalienable right of Jewish people to live and settle in the Holy Land. Titled the “Law of Return,” it states that “every Jew has the right to come to this country as an oleh.”

But the law did not define who is a Jew.

In 1970, the Law of Return was amended to apply to “a child and a grandchild of a Jew, the spouse of a Jew, the spouse of a child of a Jew and the spouse of a grandchild of a Jew.” It defined as Jewish “someone who is born to a Jewish mother, or has gone through a conversion”—omitting one crucial word: K’halacha. The law recognized halachic and non-halachic conversions as valid (the latter if they took place outside of Israel) and allowed them to settle in the land as Jews.

THE REBBE’S TAKE:

The Rebbe spoke about the issue of Mihu Yehudi (literally, who is a Jew) for the first time publicly on Purim 5730 (1970). He said that this new law was a terrible decree, “the likes of which have

not been seen before.” The Rebbe continuously fought this law, explaining that it was completely against Torah, comparing it to the level of avodah zarah that the Yidden worshiped at the sin of the Golden Calf.

At the time that the law was passed, Israel endured a number of tragedies, including a terrorist attack in Ma’alot during which 28 people were murdered. The Rebbe linked the two occurrences (something the Rebbe rarely did), and called upon the Israeli government to take a strong stance and correct this error.

THE OUTCOME:

Unfortunately, the law has still not changed, and the damage done is irreparable. Assimilation, intermarriage, and confusion about one’s Jewish identity are just some of the problems that were exacerbated by it.

Many frum individuals and organizations who once dismissed or even ridiculed the Rebbe’s stance have recognized— all too late—the importance of the Mihu Yehudi issue. Unfortunately, with Israel’s continued reliance on American organizations and movements that have a strong stance against defining Judaism in accordance with halacha, the law is not presently likely to change.

A sign about a rally against the law

Chabad activists delivering a petition signed by 1 million people against the law to Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir

RAMBAM MENORAH: SHINING A LIGHT ON ACCURACY

THE ISSUE:

The Menorah in the Beis Hamikdash has often been depicted with round branches. One of the most well-known of these images is engraved into the Arch of Titus in Rome. Jewish sources, however, state that the Menorah’s branches were straight and diagonal. Unfortunately, the “round Menorah” is pervasive, from the emblem of the State of Israel to illustrations in children’s books.

THE REBBE’S TAKE:

At a farbrengen in 5742, the Rebbe spoke at length about the shape of the branches of the menorah in the Beis HaMikdash and proved that they had to have been diagonal. He based his conclusion on the commentary of Rashi and upon a diagram drawn by the Rambam, as well as the writings of the Rambam’s son Rabbi

Avraham, which were unearthed in the Cairo Geniza in Egypt.

The fact that the round-branched Menorah was inspired by the Arch of Titus greatly disturbed the Rebbe. As he explained: “Instead of drawing the menorah and inspiring a Jew to fulfill his mission to be a ‘light unto the nations,’ they make the menorah in such a way that it reminds him of the opposite, that Rome vanquished the Jews, G-d forbid!”

The Rebbe clearly explained how the round branches are not halachically or historically accurate.

THE OUTCOME:

The Menorah debate is far from resolved in the greater frum community. A giant golden replica of the Menorah with round branches stands in the Old City of Jerusalem. It was built by the Temple Institute (Machon

Hamikdash), which doesn’t even cite the Rambam’s opinion in its dictionary entry about the Menorah. New books such as The Book of Torah Timelines, Charts and Maps (Artscroll) do the same.

But recent scholarship has discovered that the Menorah was depicted with straight branches in communities around the world. Dr. David Sclar references a Yemenite manuscript from hundreds of years after Rambam’s passing, which depicts a straight-branched Menorah. “There are at least a dozen instances of straight-branched menorahs in historical Yemenite manuscripts,” he said.

While the Chanukah Menorah isn’t meant to be a replica of the original one, Chabad Shluchim have been putting up public menorahs with straight, diagonal branches. They bring both the light of the holiday and the light of truth to more than 100 countries.

A depiction of the Rambam in the Rambam Square in Ramat Gan, Israe

Photo Dr. Avishai Teicher

PAYMENT PROCESSING ISSUES?

We specialize in:

Merchants with poor credit

Fighting chargebacks

Assisting with creating marketing material for the application

Large ticket transactions

Creating company policies

PCI compliance

Assist merchant with money on hold

By Mendy Kortas - Kfar Chabad Magazine

Abu Daoud & Reb Zalman

The longtime covert Israeli agent in Lebanon and his Lubavitcher friend

Israel Lebanon Border

At 6:22 AM on Sunday, October 23, 1983, a yellow Mercedes-Benz flatbed truck filled with explosives crashed into the Marine barracks at Beirut International Airport.

The American troops had been stationed there as part of a military peacekeeping operation during the Lebanese Civil War and following the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) withdrawal in the aftermath of Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon.

Expecting a water truck, the soldiers had limited rules of engagement, making it difficult to respond. Only one guard managed to chamber a round, but by then, the truck, driven by an Iranian national, Ismail Ascari, had already reached the building.

The explosion, equivalent to 12,000 pounds of TNT, collapsed the four-story barracks, killing 241 American servicemen. It was the deadliest single-day death toll for the Marine Corps since the Battle of Iwo Jima in World War II.

Then-U.S. Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger said there was no knowledge of who did the bombing. This past month, on the 40th anniversary of the bombing, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken was clearer about who was responsible: The Iran-backed Shiite terror group, Hezbollah.

“I remember that explosion like it was today,” recalls Yair Raviv, who at the time served as the commander of the Mossad’s operational station in Beirut. When asked to elaborate on what had transpired there after that, Raviv remains tight-lipped. He is only allowed to confirm his presence in the country at the time, but not say anything about his activities.

Ravid, a legend in intelligence circles, has a long and accomplished career of serving in numerous positions in the field of recruitment and operation of agents for Israel in Arab countries. His codename was “Abu Daoud.”

“Beirut is a beautiful city,” he said, “But Lebanon, in general, is a country divided into sects and different religions, many of which will never come together. There is no understanding between the religions, and their relationships are built on interests — ‘you scratch my back, and I’ll scratch yours.’

Generally speaking, each sect lives in a different area.

“The Shiite Muslims live in Dahieh in Beirut. There are also Shiites in the Beqaa Valley and the country’s south, though they are a minority. In the south, there are many Christians. Beirut itself is also divided into regions. In the eastern part of the city, there are mostly Christians. The Shiites live in the western part of the city and the south, including Dahieh. In the West, there are also Sunnis and Palestinians. The Druze mainly live in the mountains.”

Ravid shared his extensive knowledge about Lebanon in his 2016 book, “Window to the Backyard: The History of IsraelLebanon Relations.” “Not all Shiites in Lebanon support Hezbollah or Iran,” he explained. “In the past, relations between

Yair Ravid speaking on Israeli TV

the Shiites in Lebanon and Israel were very good. Many people from southern Lebanon worked in Jewish settlements and earned a decent living; some even spoke Hebrew. There are Shiites in Lebanon who could form an opposition to Hezbollah, but they are powerless.”

Asked if they have a chance now that Israel eliminated the top brass of the Hezbollah leadership and launched major attacks on its military capabilities, Ravid said it wasn’t enough. “Only if Lebanon returns to the Stone Age – without infrastructure, power stations, refineries, and bridges – can a local opposition emerge,” he stated.

Professor to the Rescue

Ravid was born in 1945 as the firstborn to Tova and Yehuda Ravitch. His mother came to Israel in 1935 from Otwock, Poland. “She immigrated alone, leaving behind family members who would later be lost in the Holocaust,” Ravid recounted. His father, Yehuda, served in the British Army’s Jewish Brigade during World War II and arrived in Israel in 1936 from Lutsk, Ukraine, with only his sister Doba surviving.

Growing up near Haifa, Yair Ravid attended a local elementary school where he and his classmates, many from immigrant families,

were united in their values. “Our class was a true melting pot,” he wrote in his book. “We welcomed students from Iraqi, Polish, and Turkish backgrounds with open arms. One friend, who came from Turkey, once told me he never felt like an immigrant because of how warmly we embraced him.”

One particularly memorable moment during his school years came after a class trip to Jerusalem before the Six-Day War. Jerusalem was then a divided city, with only the western part under Israeli control. In a school essay, he wrote: “We didn’t visit Jerusalem, only its suburbs. The real Jerusalem, with the Temple Mount and Western Wall, was under Jordanian rule. I wished for the day it would be returned to its Jewish owners.” Despite the school principal expressing disapproval. Ravid’s mother supported him, asserting, “What the boy wrote is correct.”

Ravid enlisted in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) in 1963 and joined Egoz. In this Special Forces reconnaissance unit, he engaged in border incidents and clashes with Syrian army posts, crucial to safeguarding Israeli settlements in the Hula Valley. “We pursued squads launched by Syrian Intelligence to sabotage our efforts and gather military information,”

he said, but wanted more. “When I enlisted, it felt right to aim for a combat role.”

With aspirations of becoming a combat officer, he signed up for an officer’s course. However, weeks before the course began, tragedy struck. Ravid was wounded during an operational activity along the northern border when a bullet struck his right arm, severing the main artery. “I lost a lot of blood,” he said.

A field medic applied a tourniquet to stop the bleeding, and Ravid was rushed to Poriya Hospital near Tiberias for emergency care. “After several hours, they managed to save my arm from amputation.” Operating on him was Professor Alfred Schramek, who interrupted his own birthday party to save a life.

A decade later, Ravid faced another medical crisis when his wife, Rivka, eight months pregnant with their second child, experienced severe abdominal pain. He rushed her to Rambam Hospital, where they discovered a tumor that needed urgent surgery.

Due to Rivka’s advanced pregnancy, the doctor called for the head of the surgical department to operate. To Ravid’s surprise, it was none other than Professor Schramek. After a handshake, Schramek asked Ravid, “Do you remember what today is?” Ravid responded, “Of course! It’s June 4, your

R’ Zalman Stambler (right) with fellow Lubavitchers during his IDF service

Yair Ravid with R' Zalman Stambler and his son Rabbi Sholom Ber Stambler, Director of Chabad of Poland.

birthday—exactly ten years since I disrupted your celebration.”

The Chossid of Unit 504

Despite the efforts of his medical team, Ravid’s right arm remained paralyzed. Although the injury forced him to abandon the combat track, he resolved to continue his service in Military Intelligence. “Even after everything, my determination to serve my country remained,” he insisted.

“I submitted a request to join the officer’s course, but I was soon informed my medical profile had dropped to a level that mandated my release from service,” he recalled. Refusing to accept this outcome, Ravid sought an interview with MajorGeneral Ariel Sharon, then the head of the IDF’s training department, to advocate for his desire to serve.

Approval was given, and Ravid began his next phase in the service of Israel’s security. He served in the IDF Intelligence Division and was eventually promoted to commander of the Northern Region of Unit 504, a military intelligence unit responsible for covert operations and counterintelligence.

The unit’s headquarters is based in the holy city of Tzfas, and Ravid saw a Chassidic man appearing at the door on a Friday in 1974. “He entered the

room, shared words of Torah, and poured ‘l’chaim’ for the soldiers,” he recalled. “It seemed like the soldiers were already friends with him. Later, he blessed all of us and went on his way.”

Ravid did not join the gathering. “I felt I had to investigate him thoroughly,” he said. “We are a unit involved in espionage. In my unit, no one with a Russian accent roams around without me knowing more about them.” At that time, the Soviet Union was a major weapons supplier to Israel’s enemies, Egypt and Syria, including during the Yom Kippur War, which occurred during that time.

Ravid got the name of the Lubavitcher Chosid: R’ Zalman Stambler.

Reb Zalman was born in Sivan 5710 (1950) in Tashkent, Samarkand, where a large community of Chabad Chassidim existed. His parents were R’ Meir Tzvi and Devorah Stambler, daughter of R’ Yaakov Panteliev, one of the first students in the Tomchei Tmimim Yeshiva in the town of Lubavitch, and later a shochet and bodek.

After managing to leave Russia, Reb Zalman moved to Tzfas in northern Israel, following the Rebbe’s calls at that time to live in the region.

In the IDF, Reb Zalman served as a reservist fighter and would visit army bases as part of his Mivtzoim.

During the war, Unit 504 needed a Russian speaker to interrogate two suspected Russian pilots. The unit’s deputy commander, Momo, drove to Tzfas and found Reb Zalman,

LOOKING FOR SHORT TERM OR A PLACE TO SETTLE

WE’RE HERE TO HELP NO MATTER HOW YOU CLASSIFY + Post classified

Whether you’re searching for tenants or on the hunt for the perfect apartment, COLlive Classifieds has you covered!

a Russian-speaking reservist, who volunteered to help. However, the pilots turned out to be Syrian, so Reb Zalman wasn’t needed—though this parting would only be temporary.

Reb Zalman began visiting Unit 504 on Fridays and holidays. Ravid, unfamiliar with the habit, conducted a background check. “I passed his details to the Shin Bet, and they cleared him, telling me, ‘He’s perfectly kosher,’ and everything was fine. I was relieved. From then on, we became friends.”

Raviv recalled, “One day, Reb Zalman discovered that one of our officers, in his early 30s, had never celebrated a bar mitzvah or put on tefillin. Naturally, he arranged it for him. A year later, that officer was handling two Syrian agents, whom I suspected were double agents. We took precautions before their next meeting, and it confirmed my suspicions—they were working with Syrian intelligence and had orders to assassinate him. This officer was miraculously saved, and we all credited it to his having had a bar mitzvah.”

Lesson in Middle Eastern Tactics

The roots of Israel’s current battle can be traced to June 1982, during the First Lebanon War between Israel and the PLO. The IDF advanced into Lebanon but halted outside Beirut under a temporary ceasefire, leaving terrorists inside the city.

The Rebbe publicly warned against delaying the conquest, predicting more casualties. After weeks of siege, Beirut fell, but over 350 Israeli soldiers had died. Israel eventually withdrew from Beirut, maintaining only a southern security zone, which it left entirely in 2000.

Hezbollah, now a major regional threat, emerged in the war’s aftermath. “We allowed Hezbollah to grow unchecked,” Raviv reflected, citing missteps, such as a failed peace agreement, Prime Minister Ehud Barak’s ineffective withdrawal policy, and the poorly executed Second Lebanon War under Prime Minister Ehud Olmert. “The recent gas deal by Yair Lapid with a Lebanese entity is similarly misguided.”

Asked about recent efforts to forge a ceasefire in Lebanon, Ravid said a diplomatic agreement is worth nothing. “Anyone who thinks there is a body in Lebanon with which an agreement can be reached is either foolish or, at best, a liar,” he declares.

As an illustration of the type of conduct required in the Middle East, he told the following story.

“In March 1984, CIA station chief in Beirut William Buckley was kidnapped by Hezbollah (then, still the Islamic Jihad Organization).

Hezbollah told the Americans that they wanted to negotiate with them and release various terrorists around the world. The Americans agreed, but Hezbollah had no patience, and they murdered him.

“Around the same time, Hezbollah kidnapped a junior Russian embassy employee in Beirut and proposed negotiations. Instead, a Russian team arrived that night, conducted reconnaissance, and by the following evening had kidnapped and tortured the son of a Hezbollah leader, leaving the body in Dahieh. The next day, the Russian employee was released without negotiations. That’s how it works in the Middle East.”

Ravid said the current war with Hezbollah in Lebanon “is being conducted wonderfully, exceptionally. The events we are seeing in Lebanon and what has happened there recently have a significant impact not only on Lebanon itself but also on Israel’s image throughout the Middle East. With Hashem’s help, we will succeed in overcoming our enemies.”

Israeli troops in south Lebanon (1982)

Yair Ravid’s book Window To The Backyard - History of Israel's relations with Lebanon - facts and illusions.

Cold Calling With a Warm Heart

By Dovid Zaklikowski

IIn December 1987, a Crown Heights couple moved from their Kingston Avenue apartment and settled in Lawrenceville, a small town in New Jersey known primarily as the home of Lawrenceville School, one of the most prestigious prep schools in America.

Rabbi Laizer and Malky Mangel were sent there as Shluchim to establish a Chabad House and bring Jewish observance to Mercer County. The town, halfway between Princeton and Trenton, was an ideal place for the task.

“We want to show people what authentic Judaism has to offer,” Rabbi Mangel, then twenty-five, told The Lawrence Ledger upon their move to the community.

“The only thing we ask is [that they] give Judaism a fair chance.”

He emphasized that Jewish life involved more than the twice yearly visits to synagogue and Sunday bagels and lox. “We want to try to stir the Jewish conscience,” he earnestly said.

Speaking to the Ledger, Rabbi Mangel said: “We reach out and

During his brief 25 years, Rabbi Laizer Mangel profoundly touched the lives of many he encountered

Rabbi Mangel at his wedding.

Photos: Lubavitch Archives, RebbeSchneerson.com, Mangel Family and Malky Dubov

work with Jews of all backgrounds and affiliations. We don’t like labels such as Orthodox, Conservative, or Reform. We all stood at Mount Sinai and received the Torah. We weren’t wearing labels or banners that signified Orthodox, Conservative, or Reform.”

Initially, Rabbi and Mrs. Mangel opened the local phone book and, scouring it for Jewish names, made countless cold calls. He also began to engage with the director of the Mercer Bucks JCC in the hope of developing a rapport. At the time, many rural Jewish communities were not familiar with Chabad, and Lawrenceville was no exception.

At first, the work seemed unfulfilling, his wife recalled, as it was not the intellectually oriented shlichus that Rabbi Mangel had sought. “But he accepted it with love,” she said, and he made every effort to be successful. “It was his gentleness that brought in people, who were won over by his sincerity.”

“I’m Here For You”

During his first few months in Lawrenceville, Rabbi Mangel rose early to drive to the Anshei Emeth synagogue in Trenton, where they began to daven at 6:45 AM. Rabbi Isaac Leizerowski, who met him there and lives today in Philadelphia, remembered that it was as if Rabbi

Mangel’s mission were just as remote as any of the shluchim stationed far away. “New Jersey may have been closer to New York and 770 in miles, but nonetheless it was far,” he said.

Mercer County is not a small area, Rabbi Leizerowski explained, and being a shliach in such a place entailed driving long distances to meet people in their homes. He recalled Rabbi Mangel telling him about his travels at night on dark, rural streets he had never seen before, yet he did not complain. “I was impressed by his sense of dedication and devotion. He showed the mesiras nefesh of a Chabad shliach.”

Family lawyer Jahn Chesnov recalled Rabbi Mangel’s attempt to assist during their very first encounter. “He was a very mitzvah-oriented person,” Chesnov said. “His attitude was 'mitzvah first.' He came in, saying, ‘Hello, how are you? Let’s get busy.’”

Indeed, the Chesnovs had just moved to a new home and needed mezuzahs. Rabbi Mangel was glad to help. They mapped out the doorways, and soon the home was fitted with the best mezuzahs Rabbi Mangel could find. After affixing them, the lawyer told Rabbi Mangel, half in jest, “I’ve

known you for five minutes, and you've already cost me five hundred dollars…”

But he was impressed with Rabbi Mangel’s zeal.

Richie Altman, a computer programmer, met Rabbi Mangel at Anshei Emeth, and they became close. He would visit Lawrenceville for Chabad events, and at times stay with the Mangels for Shabbos. “When you were in his house,” he said, “you felt like a member of the family.”

He recalled how Rabbi Mangel would carefully choose his words. In offering his point of view to others, “he tried to steer them in a quiet and small way, not in a hit-them-over-the-head way.”

Altman recalled an episode that left a lasting impression on him. When Rabbi Mangel once returned home from a shopping trip, he realized that the cashier had given him too much change. Without hesitation, he immediately drove back to the shop to return the money. Then, concerned that the cashier might lose her job over the error, Rabbi Mangel sought out the manager to explain that it had been a hectic time and the cashier had made an innocent mistake.

Making Inroads

By April 1987, the Lawrence Ledger reported that the Mangels were making inroads into the “college communities at Princeton University, Rider College,

and Trenton State College.”

“Judaism is losing young and old members to assimilation, intermarriage, indifference, apathy, and cults,” Rabbi Mangel told the paper in an interview. In the three months since Chabad opened its doors in Mercer County, the response has been “very warm and favorable,” he said.

There were two Orthodox shuls in the area, which allowed the Mangels to work in conjunction with them and focus on programming for the populations they hoped to reach without undertaking the additional task of opening a synagogue. “It was a good combination for a young rabbi,” Dr. Markus Barth, a local optometrist, said.

Sadly, community strife caused a rift between shuls. When the two shuls had a difficult time procuring a minyan, Rabbi Mangel tried to reunite them. During that period, Dr. Barth asked Rabbi Mangel: Would he rather leave the issue alone or continue to pursue what was right? Rabbi Mangel responded that he was unequivocally committed to pursuing what was right.

When the Lawrenceville Young Israel lost its home at a senior apartment complex, Dr. Barth offered his waiting room. Rabbi Mangel would daven with them, and having to put on two pairs of tefillin daily made him the last to leave. This provided Rabbi Mangel and Dr. Barth the opportunity to speak after minyan. “It was apparent that he was extremely well-educated,” recalled Dr. Barth, “and not only in Torah.”

Rabbi Mangel, Dr. Barth recalled, was able to hear diverse viewpoints while elucidating the Torah’s perspective. Previously, the explanations he had received had felt hollow, but with Rabbi Mangel, “I really enjoyed discussing deeper commentary,” he said.

During their discussions, Rabbi

Mangel never urged him to accept something superficially and move on; rather, he delved into the context of the story, explaining that the Torah’s words always had purpose.

During their time together, Dr. Barth recalled being a difficult student of religion, frequently taking on the role of ‘devil’s advocate.’ Rabbi Mangel, in response, was always ready to discuss his points. “This added another layer to our relationship and our friendship,” he said. He quickly realized that there was no way he would shake Rabbi Mangel’s belief but found that “he was making me think about mine.”

Not Easily Distracted

Over many months, Rabbi Mangel focused on expanding teaching opportunities, spending much time preparing for classes and teaching students, as his wife later recalled. One person affected by Rabbi Mangel’s efforts was Shimon Salama. Even decades after moving away from Lawrenceville, he remembered his first exposure to Judaism at the Mangel home as having been an experience that had changed the trajectory of his life. He recalled that while Rabbi Mangel was teaching, “he was very intense, and when he concentrated, he wouldn’t get distracted easily.”

While his classes were focused, the social mingling was always lighthearted. Rabbi Mangel would put tefillin on attendees and make small talk, ensuring that he interacted with each person in attendance.

Salama, today a vice president of research and technology at Appleton Papers in Wisconsin, was also surprised to see the variety of people Rabbi Mangel attracted. “These were not easy people to convince; there were a lot of intellectuals,” he said, but it was Rabbi Mangel’s quiet charisma that won them over.

Art Finkle, professor of political science at Kean University, said that Rabbi Mangel opened up the world of Chassidus to him. He had read books on the movement and philosophy, but meeting a chossid altered his views. Rabbi Mangel, he said, was inspirational, intelligent, and could relate to people. “He had the wisdom of the sages. He was the real deal.”

Shmuel Silberman was a teacher at a local Conservative Hebrew school and invited Rabbi Mangel to speak with his class. Rabbi Mangel, he said, stressed that every Jew was important and that they must recognize the role they had in the overarching Jewish story.

Silberman, today a teacher in Brookline, Massachusetts, recalled discussing fear of divine punishment with Rabbi Mangel. Rabbi Mangel, who took a different philosophical approach, encouraged Silberman to focus more on the positive outcome of a person’s efforts. He explained that while the concept of punishment was genuine, it should not be emphasized. His advice was to “Focus on all the good you can do to make the world a better place and help bring Moshiach.”

The Last Melave Malka

On a summer Friday, Rabbi Boruch and Tova Chazanow, Shluchim in Manalapan, in neighboring Monmouth County, NJ, invited Rabbi Mangel to a melave malka that Motzoei Shabbos. Rabbi Mangel said he intended to come, but he’d be late because he was leading a Havdalah ceremony that night in honor of a local boy’s bar mitzvah.

After the Havdalah ceremony, Rabbi Mangel made the fortyminute drive to Manalapan. He found Rabbi Michel and Chani Gurkov, Shluchim from Virginia,

already there. They spoke at length about their activities and plans, and Rabbi Mangel was as eager to hear new ideas from fellow shluchim. Then conversation turned to the newest technological innovation—the fax machine—and how it could be used to send educational material directly to people’s offices and homes. To the others in attendance, Rabbi Mangel’s enthusiasm was evident. One thing was clear, said Mrs. Gurkov, “He was over the moon to be a new shliach. He was excited about their future in Mercer County.”

It was 3:00 AM when the guests finally rose and prepared to leave. The Chazanows offered Rabbi Mangel a bed for the night, but he declined, saying that he had to be at Young Israel early in the morning. “I am a soldier on duty,” he said. “I need to be in the place of my shlichus.”

Rabbi Mangel never made it home. As he was driving back, a drunk truck driver fell asleep at the wheel and hit Rabbi Mangel’s car. He was instantly killed.

Just before 11 on Sunday morning, the 4th of Tammuz 5748 (June 19, 1988), the police arrived in Crown Heights to inform Rabbi Mangel’s family of a tragic car accident involving Rabbi Mangel. The Jewish community of Lawrenceville was stunned, with many struggling to process the magnitude of their loss.

That Sunday, Dr. Barth had just returned from a trip to Richmond, Virginia, where he had gone to visit his father’s grave on his yahrtzeit. At a museum in Richmond, he purchased a souvenir sword for Rabbi Mangel, with whom he had always joked that he looked like a Southern general—only lacking a sword. Rabbi Mangel, in turn, would kid that all Barth was missing was a gartel

On Monday morning, Dr. Barth had brought the gift sword for Rabbi Mangel to services, where he was told the devastating news. “I didn’t even know how to express the grief,” he said. “It was so earthshattering.”

Later that day, he received a call from Rabbi Mangel’s wife. She told Dr. Barth that her late husband had left something for him. She said, “When he was in New York, he bought you a gartel.”

An excerpt from On Duty: The Life of Laizer Mangel by Dovid Zaklikowski, a journalist, archivist and biographer. He can be reached at DovidZak@ HasidicArchives.com. On Duty is available at chabadba.com/onduty

Rabbi Mangel doing mivtzoim at a New Jersey senior center.

Rabbi Mangel (center right) doing mivtzoim in Manhattan.

Rabbi Mangel helps a student put on tefillin on Merkos Shlichus in South America.

Rabbi Mangel leading a model matzah bakery in New Jersey.

Ain’t Gonna Box on Saturday

Dmitriy Salita punched his way through to keep his faith in the ring

By Chaya Chazan

Born in Odessa under Soviet rule, Dmitriy Salita quickly learned to be resilient and make do with little. The Salita home was very typical of a Soviet household. The names his parents chose for their sons, Dima and Misha, could hardly be more traditional—with one significant difference: the Salitas are Jewish. In the 1980s, that was more than enough to set them apart.

Many living under Soviet rule caved to the pressure, changing their last names to one less conspicuously Jewish so their employment or university applications wouldn’t be automatically denied with one swift glance. Despite being largely ignorant of Jewish tradition, the Salitas kept their last name, making them a target of ridicule by classmates, teachers, and university administrators.

The family immigrated to the United States in 1991, expecting

a better future. However, the seedy streets of the Starrett City housing development in Brooklyn weren’t the utopia they’d imagined. Plunged into a new culture with an unfamiliar language, they struggled to make ends meet. There was one major advantage—they could now be openly and proudly Jewish.

From a young age, Dmitriy had an affinity for religion and a spiritual yearning he barely understood. He begged his parents to take him to a synagogue until they finally relented. One fair Shabbos morning, they drove to a nearby temple and sat on the upholstered wooden benches as the rabbi approached the pulpit. He was a consummate professional; his words were polished, and his address was urbane. Dmitriy left, feeling something was missing, although he couldn’t put a finger on it.

Around this time, Dmitriy started developing his inborn talent for

boxing. His first gloves were a musty pair, half moth-eaten, in the corner of the stuffy boxing gym a few blocks away from his home. In the winter, the harsh winds blew through the cracks in the windows and doors. In the summer, the air hovered listlessly in the room, untouched by the hum of even a simple fan. Salita was determined - and ambitious. He knew this was his ticket out of forever remaining “the immigrant kid.”

He trained day after day, putting up with extreme discomfort and hardship. No lack of air conditioning, black eyes, or heavy weights could deter him from his goal. He kept his eye on the prize, and for now, that was enough.

Meeting Lubavitchers

In 1995, Salita’s mother was hospitalized while undergoing treatment for breast cancer. Every time Salita visited, he eyed his

mother’s roommate with silent curiosity. She was an Orthodox Jew, and Dmitriy’s heart was bursting with questions he could only contain with difficulty.

One day, when he came to visit, his mother’s roommate was also receiving a visit from her husband. Despite the intimidating black hat and long beard, the man looked kind, and Salita gathered the courage to finally ask the questions he’d been harboring for a long time.

The exchange led to a visit by Mrs. Henya Schusterman of Crown Heights, who was actively involved in helping Russian Jewish immigrants. She introduced the Salitas to Rabbi Zalman Liberow, Director of Chabad of Flatbush.

When Salita walked into Chabad of Flatbush for the first time, he immediately felt at home. Jews from every walk of life greeted each other as friends and were each treated as guests of honor by Rabbi Liberow.

Rabbi Liberow’s speech was liberally peppered with Hebrew and Yiddish

terms wholly unintelligible to Salita. Still, despite not being able to follow it fully, he instinctively knew this was “the real deal.”

Rabbi Liberow’s genuine care, total devotion to the Rebbe, and passionate sincerity made a deep impression on Salita. He started attending services at Chabad more regularly.

The haunting niggunim spoke to Salita’s soul, helping him connect to the words of davening, even though he didn’t understand them. But it was the stories that touched him most deeply. Rabbi Liberow loved telling tales of simple Jews whose service of Hashem was unparalleled. They couldn’t boast of great Torah knowledge or of hours spent davening with utmost kavanah. Instead, they used their G-d-given talents to serve their Creator.

This point was emphasized when others in shul looked skeptically at the “kid who was into boxing” and tried to convince Rabbi Liberow to turn Salita’s hobbies in a more conventionally Jewish direction.

“Every talent is a gift from Hashem and can be used to serve Him,”

Rabbi Liberow insisted. “I know Dmitriy will do great things!”

Salita’s two-fold, oxymoronic journey, both to the boxing ring and the synagogue, continued to grow concurrently. In one area, he aced one amateur championship after another, while in the other, he learned to read Hebrew and started committing to keeping certain mitzvos.

The incongruity in Salita’s life was soon blended when Rabbi Liberow’s brother Yisrael, a boxing fan, became Salita’s manager. As they traveled the country to attend matches, Liberow introduced him

to the local shluchim. Salita soon formed close connections with many more rabbis and knew that wherever he went, he could always be sure of a warm welcome at Chabad.

Professional and observant

In 2000, at eighteen, Salita faced the biggest challenge in his life, professionally and in faith. He was slated to appear in the Under-19 US Nationals, his largest competition to that date. The stakes were high. Salita was understandably nervous. He called Rabbi Liberow and asked for a blessing for success. “I’ll help you write a letter to the Rebbe,” Rabbi Liberow told him.

Salita placed his letter in a volume of Igros Kodesh and opened it to a letter in which the Rebbe gave a bracha for success and advised the person

that since they’d be in a position to influence a large crowd, they should behave appropriately.

“The letter is telling you not to box on Shabbos,” Rabbi Liberow said.

Salita’s jaw dropped. As a Jew and an immigrant, there was already enough riding against him. Not boxing on Shabbos would be tantamount to career suicide. So many matches took place on Shabbos, including the final of the US Nationals!

Salita grappled with the challenges for a while until, with Rabbi Liberow’s encouragement, he decided to fully commit to keeping Shabbos. After all, his family had moved to another country because they weren’t allowed to practice their religion. It would be almost hypocritical to misuse this opportunity.

The competition was a tournament

championship. Losing a match meant packing your bags and heading home. As Salita signed the initial paperwork, he informed the officials that he wouldn’t participate in any matches held Friday night or Saturday. They stared at him blankly.

“The final is on Saturday. If you don’t box, you’ll be disqualified,” they told him.

Regardless, Salita wrapped up his hands and put on his gloves, determined to give it his all and see how far he could get. Day after day, bout after bout, he emerged victorious. The unknown kid from Ukraine was now the favorite to win the tournament.

“We don’t know anything about you,” Dillon Hernandez, a sports journalist, said in an interview. “What can we expect from you in the upcoming finals?”

Dmitriy Salita and Alona Aharonov at their wedding outside 770 Eastern Parkway in 2009.

Dmitriy Salita being inducted into the New York State Boxing Hall of Fame in 2023

Photo

Alex Gorokhoy

“Nothing,” Salita shrugged. “I won’t be competing. I’m a Jew, and I won’t box on Saturday. They told me I’d be disqualified.”

Hernandez saw potential in Dimitry’s small but statuesque form and was impressed with his integrity. He spoke to the board on Salita’s behalf and convinced them to change the time of the match so Salita could attend.

Salita emerged as the victor of the US Nationals, proving to all, not least of all himself, that being an observant Jew was not a contradiction to being a boxer. A year later, when Salita became a professional boxer, he included a Shabbos clause in his contract.

Salita went on to win many awards, including the Golden Gloves championship, the North American Boxing Association

light welterweight championship, the International Boxing Federation International, World Boxing Association International, and the WBF Junior Welterweight world title. The “kid from Odessa” was invited to the White House, met US President George W. Bush in 2007, and was inducted into the New York State Boxing Hall of Fame in 2023.

Salita has since moved to the business side of boxing, founding a boxing promotion company, Salita Promotions, in New York, where he lives with his wife Alona and his two children. He maintains the same fierce dedication to keeping Shabbos, even though much of his job is centered around events and payments that must take place on the holy day. Ambitious as ever at 42 years old, he’s currently taking classes at Pritzker Northwestern Law School to amp up the services he can provide to his boxers.

Dmitriy also knows that in Judaism we always strive higher, setting new goals the moment the last battle has been won. He’s found a constant source of inspiration in the Tanya. “I listen to Rabbi Yehoshua Gordon’s Tanya shiurim online,” Salita shared. “His sincerity and down-to-earth explanations bring the amazing sefer to life. Tanya is the perfect guidebook for life. It teaches you about who you are in your essence and what you need to grow.”

A recent winner of the USBA Promotor of the Year Award, Salita has used his G-d-given talents to make a kiddush Hashem on a major scale. As a promoter, he encourages his fighters to make the most of their special gifts and use them to make the world a better place.

Dmitriy Salita promoting professional boxer Marlon Harrington (left) on the Fox 2 station in Detroit.

“AND YAAKOV WENT ON HIS WAY” g

On Motzei Simchas Torah, after the uplifting and joyful month of Tishrei, it is customary amongst Chasidim to announce "V’Yaakov holach l’darko" — "And Yaakov went on his way," reminding

us that we must take inspiration from these special moments as we transition back to our everyday lives. This month's issue highlights the final moments of Tishrei in 770.

The tradition of “Selling the Mitzvos,” giving people the chance to give tzedakah to the shul in exchange for opening the Aron Kodesh, receiving an Aliyah, and the like, was usually held in the presence of the Rebbe on Shabbos and Yom Tov. These photos show one of the two unique occasions when this auction was held on a Motzei Shabbos, at the Rebbe’s Farbrengen in the year 1980 (5740).

Rabbi Yehoshua Pinson, the head Gabbai of 770 led the auction, wearing the customary shtreimel, while the Rebbe learned from a sefer.

At the end of Tishrei, the Rebbe holds a General Yechidus for various groups, including Tishrei guests, Bar and Bas Mitzvah, Chasanim and Kallos, and Yeshiva bochurim. The Rebbe delivers a special Sicha, blessing each person, and encouraging them to “unpack the bags” of inspiration they received over the special month, as they enter the new year.

In the days between Isru Chag and 7 Cheshvan, visiting guests would stand in the back of 770 after tefilos and ask the Rebbe for a bracha for a safe return home.

After the Sicha, each participant is given the opportunity to hand the Rebbe a pan and receive a dollar for Tzedakah.

After everyone passes by, and the shul empties, the Rebbe insists on carrying the large bags of panim on his own.

In earlier years, the Rebbe would stand at the entrance of 770 to bid farewell to the guests, moments before they departed for the airport.

The Rebbe watches the departing buses until they are completely out of sight.

By Rabbi Daniel Schonbuch, MA, LMFT

The Spark of the Soul in Therapy

The importance of increased spirituality in healing past traumas

Where does the drive for meaning exist in human consciousness? Viktor Frankl, the famous holocaust survivor and psychologist, identified the source in a book called, The Unconscious God, where he describes the psychological unconscious goodness and “will” for spirituality and God.

According to Frankl, this part of our unconscious mind is called the religio, which guides us in discovering our spiritual nature and connecting with God. Frankl used this term to imply that God remains hidden in the unconscious, meaning that one’s relationship with Him is unknown to oneself. However, when this will is brought into a person’s consciousness, it can guide the person to overcome any emotional challenges they are facing. Frankl spoke extensively about these hidden spiritual and religious desires in a period that was dominated by the teachings of Sigmund Freud. It was Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, who

dominated psycho- therapy for over half a century. He maintained a decidedly negative attitude towards spirituality and God. He believed that God was a human invention created to reduce fears of helplessness. Freud therefore dissuaded his clients from seeking spiritual endeavors, insisting that they were merely a crutch people leaned on to manage their fears.

Frankl took a decidedly different approach. He believed that following the unconscious drive for meaning and for God (the religio), was the cure for man’s psychological dilemmas. Logotherapy therefore provides a framework to find the internal “spark” needed for change. In a session, this takes on many different avenues including helping the client discover their creativity, fulfilling their values, finding someone to love, or fulfilling some lifelong dream or task. We operate under the premise that everyone has a deep reservoir of hidden spiritual strengths and emotional resources waiting to be brought into consciousness.

Focusing on discovering meaning and uncovering the inner will for spirituality kindles a remarkable type of emotional transformation. When my clients identify this “spark” they often report feeling a new type of “wholeness” accompanied by feelings of euphoria or joy. And, it is these kinds of positive emotions that are necessary to battle depression, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress disorder.

Instead of dredging up and focusing on negative emotions, Logotherapy arouses powerful emotional resources that literally shift the individual into a positive and forward-thinking mindset. This new mindset becomes the catalyst towards emotional change and personal resilience.

The Mitteler Rebbe and Therapy

As a rabbi and therapist, I also expand the key spiritual concepts outlined in The Unconscious God with the ideas of Rabbi Dovber Shneuri, also known as the Mitteler Rebbe (1773–1827). Rabbi Dovber articulated a system of contemplative meditation that forms the basis of spiritually-based psychology.

Two of his seminal treatises, the “Tract on Contemplation” and the “Tract on Ecstasy,” offer a detailed and comprehensive method of analysis and observation. Similar to what Frankl is alluding to, Rabbi Dovber describes the psychospiritual power of the Godly soul and what happens to a person when they think about God. I utilize this approach in helping my clients grow from a psychological perspective.

The ideas of both Rabbi Dovber and Viktor Frankl exist in great contradistinction to classical schools of psychology, where the goals are to help patients resolve inner conflicts, deal with childhood traumas, or change their negative self-beliefs. If we look at the real needs of most of our clients, it is apparent that psychotherapy that only explores people’s pasts only offers one dimension to resolving their emotional problems. Additionally, the cost of extensive psychotherapy creates certain limitations. How can meeting with a therapist once a week for forty-five minutes provide enough support for our clients to grow?

The therapeutic methods of Dr. Margaret Wehrenberg, a nationally recognized psychologist who specializes in treating depression, concurs with the approach offered by Frankl. She explains how therapy needs to be augmented with daily spirit habits:

“Evidence continues to accumulate that many people who have anxiety and depression suffer bouts of it all their lives, even after a good response to therapy. Therapists need to provide individualized care and tools (including social support) to cope with unexpected changes, along with a daily program of meditation and spiritual connection, and daily optimistic reminders of the chronicity of their condition and how they’re managing it.”