VOLUME 21 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2025

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

VOLUME 21 • NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2025

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Editorial

EDITOR

Daniel Mahoney

EXECUTIVE

EDITOR

Rob Levin

COPY EDITOR

Caitlin Meredith

EDITORIAL

CONSULTANT

Jodi Baker

DESIGN

Corey Blake

Z Studio Design

Administration

PRESIDENT Sylvia Torti

PROVOST Ken Hill

ASSOCIATE ACADEMIC DEAN

Kourtney Collum

DEAN OF ADMISSION

Heather Albert-Knopp ’99

DEAN OF INSTITUTIONAL ADVANCEMENT

Shawn Keeley ’00

DEAN OF ADMINISTRATION

Bear Paul

DEAN OF STUDENT LIFE

Joshua Luce

DEAN OF COMMUNICATIONS

Rob Levin

Board of Trustees

TRUSTEE OFFICERS

Beth Gardiner, Chair

Marthann Samek, Vice Chair

Hank Schmelzer, Vice Chair

Ronald E. Beard, Secretary Barclay Corbus, Treasurer

TRUSTEE MEMBERS

Cynthia Baker

Timothy Bass

Michael Boland ’94

Joyce Cacho

Alyne Cistone

Heather Richards Evans

Allison Fundis ’03

Marie Griffith

Cookie Horner

Nicholas Lapham

Howard Lapsley

Casey Mallinckrodt

Chandreyee Mitra ’01

Roland Reynolds

Laura McGiffert Slover

Laura Z. Stone

Steve Sullens

Claudia Turnbull

LIFE TRUSTEES

Samuel M. Hamill, Jr.

John N. Kelly

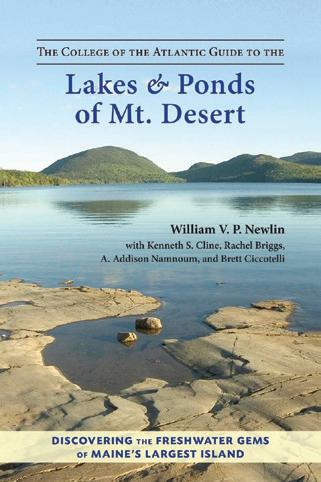

William V.P. Newlin (deceased, 2024)

TRUSTEES EMERITI

David Hackett Fischer

William G. Foulke, Jr.

Amy Yeager Geier

Elizabeth D. Hodder

Anthony Mazlish

Jay McNally ’84

Philip S.J. Moriarty

Cathy Ramsdell ’78

Hamilton Robinson, Jr.

Nadia Rosenthal

William N. Thorndike

EX OFFICIO

Sylvia Torti

At College of the Atlantic, we envision a world where creativity, presentness, compassion, respect, and diversity of nature and human cultures are highly valued. A world where all people have the opportunity to construct meaningful lives for themselves, gain appreciation of the relationships among all forms of life, and safeguard the heritage of future generations.

COA Magazine is published annually for the College of the Atlantic community.

OVERTHE PAST few months, I have been considering the profundity and complexity of the word reciprocity

A quick online search in the MerriamWebster Dictionary resulted in two definitions: “Mutual dependence, action, or influence,” and, “A mutual exchange of privileges.”

Those were both satisfying enough, even if I wondered at the deeper meaning of influence and privileges Instead of diving into the many possible iterations and historical contexts of Merriam’s definitions, I decided to explore reciprocity through other texts.

The next definition I found online was a proverb: “One gives freely, yet grows all the richer; another withholds what he should give, and only suffers want” (Proverbs 11:24). This notion of reciprocity spoke to me in its simplicity and depth and its fundamental recognition of relationship. It said nothing of influence or privilege

A few days later, I met with a COA faculty member and mentioned to her that I was thinking about this question. The next day I found a copy of Robin Wall Kimmerer’s The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World (Scribner, 2024) in my mailbox. That very evening, I read through that succinct and very fine book, and I found this line: “We are all bound by a covenant of reciprocity: plant breath for animal breath, winter and summer, predator and prey, grass and fire, night and day, living and dying.”

Here was reciprocity in action. A comment in passing, a book placed in a mailbox, a new world of ideas spread from one mind to another and then another.

The days got colder, well below freezing, and Kimmerer’s book sat on the table staring up at me morning and evening. On its cover is a picture

of a serviceberry tree and a waxwing bird. With temperatures in the teens, I was impelled to go to our local hardware store, filled with wonderfully helpful people, and buy a bird feeder for my new home. These past days, I’ve received deep pleasure as I sit with my morning coffee and enjoy the company of chickadees, juncos, and cardinals outside.

Having circled around these many meanings and takes on reciprocity, making my own circles as I trudged through snow and ice around nearby Witch Hole Pond in Acadia National Park, I realize that being asked to write something about reciprocity was a gift, one that led me to internal and external conversations with writers and thinkers from so many perspectives, from conversations with humans and nonhumans around me. In the end, I have come to believe that reciprocity is just that—ecological relationships repeated over and over, whether in giving a gift or receiving one back. It’s a call or a meditation, a prayer or a scientific study, that helps us give daily thanks for breath and food and seasons. Thanks for repeated circles around a pond, the building of new friendships, and gratitude for those that endure and grow.

Sylvia

IN DECEMBER 1956, at Sun Studios in Memphis, Tennessee, Carl Perkins, Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Johnny Cash were hanging out together playing music. They were young and at various stages of (super) stardom except for Jerry Lee Lewis, who was unknown but who had more than enough ego to match the other musicians. About an hour into this jam session, Sam Philips, head of Sun Studios, hit the record button on what came to be known as the Million Dollar Quartet session. Between one of the songs, Presley talks about seeing a young man performing Don't Be Cruel in Las Vegas—a young, unknown Jackie Wilson—and being blown away by the performance. One thing that struck Presley was the way Wilson intoned the word telephone in the line, If you can't come around, at least please telephone... Presley tells the other musicians that he liked Wilson's version of the song more than his own.

You can see the influence Wilson's performance had on Presley if you google "Elvis on Ed Sullivan 1957" and

watch Presley sing Don't Be Cruel one month later. Presley uses Wilson's stylized telephone and the smile that brightens his face afterward is unmissable. I love that. The smile of a young Elvis Presley directed to a young Jackie Wilson coming to us via YouTube in 2025 when the world feels as upside down as it may have felt in 1956 when the struggle for Civil Rights was ongoing, and war was raging in the Middle East, simmering in Vietnam. I'm not saying that a smile from Elvis Presley is enough to heal the world, but it is a reminder that—upside down or not—life moves on and we move on with it.

For me the act of teaching carries with it the utopian idea that someday, 15 or 20 years after being at COA, a student will remember the class when we discussed a poem by Jane Mead about travelling alongside a truck loaded with chickens in cages, and how that poem was horrifying and miraculous and meant something. Or maybe a student years after graduating will think of herring gulls or velvet worms or palm-wine music or schist... But the idea that people will still be thinking and remembering and building new connections to old knowledge is a boon to me because it's why each of us made the choice to come to COA. We wanted to weave webs of meaning. We wanted to build the reciprocal.

Neither Presley nor Wilson would make it out of their 40s, but we have the music and the performances. If you have not communed with the voice and music of Jackie Wilson in a while, I suggest you find some speakers and turn (Your Love Keeps Lifting Me) Higher and Higher up as loud as you can stand. Swim in that wall of sound. Wrap yourself in that voice. This is a gift!

Dan

AUGUST: COA students conduct an energy audit at a home on Great Cranberry Island. Led by energy director David Gibson and in collaboration with the Campus Climate Action Corps, the group audited 18 homes on the island and provided detailed reports and suggestions. The project was funded by a US Department of Energy Buildings Upgrade Prize.

Honoring COA’s unoffi cial mascot, the Black Fly Society was established to make donating easier and greener. You can join this swarm of sustaining donors by setting up a monthly online gift. It’s the paperless way to give to COA.

NOVEMBER: Protesters gather at the 29th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in Baku, Azerbaijan, where the annual COA delegation, led by professor Doreen Stabinsky, was in attendance. The US has since begun to formally withdraw from the framework.

JUNE: Opal Architecture Management Partner Tim Lock speaks at the dedication ceremony for Collins House, COA's new residence hall named for president emeritus Darron Collins ’92 and his family. The building is designed and built to stringent Passive House energy standards.

By Jeremy Powers ’24

CAMPUS IS ALWAYS abuzz with new faces. In the fall, there’s the incoming class, eager to craft new memories and discover what human ecology is really all about. This year we have some new staff and faculty, notably our president, who takes the helm as the college finds itself at the cusp of an exciting new chapter. But there’s at least one new face that’s not so new after all:

COA alum Brittany Slabach ’09, who is thrilled to rejoin College of the Atlantic as the new Kim M. Wentworth Chair in Environmental Studies.

A conservation ecologist by trade and a human ecologist by nature, Slabach leans toward an experiential approach to most things, especially her teaching practice—instead of bringing the population dynamics of mountain-top mammals to the classroom, Slabach prefers to bring the classroom to the mountaintop mammals themselves.

“My goal is really to teach students to not fear complexity and instead embrace it—I think one of the best ways to do that is to dive in head first,” she says. “It isn't a matter of just talking about theory and how it works in the real world—it's about actually getting out there and doing it, because nothing is ever as it seems in a textbook.”

This approach lends itself well to fostering a highly flexible and dynamic dialogue driven by student interests. “Say, for example, that we’ve talked about hagfish, and everybody's really curious about hagfish slime. So we’ll spend time talking about what makes hagfish slime special.”

Slabach’s courses include Wildlife Ecology and Biology: Form and Function. She also teaches Invertebrate Zoology, where she takes students on a deep dive into the physiology and ecology of invertebrate organisms, and Ecology: Natural History, where students learn about foundational ecological principles by doing hands-on field work in and around the diverse ecological communities on Mount Desert Island.

Photo by Will Draxler ’26.

Slabach has spent the last few years teaching and studying vertebrate ecology, culminating in a Schoodic Institute-funded study that investigated how recreational trail use affects mammal populations living on the mountain-tops of Acadia National Park. The project involved several current COA students and faculty, and Slabach plans to implement several aspects of that project into her teaching here.

She also emphasizes that although she’s the professor, she also holds a role as a learner. “My students are in the driver’s seat. They keep me on my toes, which I appreciate,” she laughs. “I really try to build in flexibility and leave room for, as I refer to them, tangents of learning.”

“College of the Atlantic is the place where, as a student, I fell in love with teaching and really decided that I wanted to pursue it as a career, professionally,” she says, remarking that stepping into the role of a faculty member at her alma mater still feels very strange and serendipitous.

“It wasn't something that I thought was in the cards or that I was really consciously shooting for,” she reflects. “It happened fairly naturally in a way that I don't think I've quite yet come to grips with. It's been truly wonderful to be back.”

Slabach holds a PhD in biology from the University of Kentucky and a Master of Science degree in biology from Tufts University. When she’s not leading class discussions on hagfish slime or guiding students through delicate intertidal ecosystems, she likes to hang out with her family, go for walks with her dogs, and bake pies and cakes. “I also like to make candy,” she says. “It’s nice to live in a colder place again—the caramel sets better.”

By Jeremy Powers ’24

MIGHT CONSIDER mud a bit of a nuisance— clinging to boots, dirtying cars, getting on clothing. Children might gleefully roll around in it, shape handcrafted pies for judgment on a baking competition, track it up and down stairs and over carpets. For marine ecologist Kara Gadeken, mud is so much more than its messy presence. For Gadeken, mud presents an ideal opportunity to learn about the past, understand the present, and plan for the future. She's looking forward to bringing students along for this exploration as she steps into the Emily and Mitchell Rales Chair in Ecology at College of the Atlantic.

“There's so much interesting science to be done in Maine. It's such a dynamic place and it's changing so quickly because of climate change. I’m after questions like, How much is there to know? and, How much do we need to know before things change? so we can adapt in time and help prevent some of the less desirable outcomes of that change from happening,” she said.

Her interest in all things marine ecology began as an accident, during the summer between her freshman and sophomore years of undergrad at William and Mary. “I started working in seagrass and I didn't even know what seagrass was. I was like, Sure, I'll do this thing for a summer, but going out into these shallow marine ecosystems and experiencing them and exploring them… it just blew my mind. I was hooked.”

should be the process of getting as far out of the way as possible of students learning what they need to learn. It should be about the facilitation of their development as scholars, as critical thinkers, as people, letting the roots of that process grow naturally.”

Disillusioned with the traditional, often clunky and bureaucratic structures of higher education, Gadeken was looking for something different. “There's a lot of inbuilt structures in academia that can really stifle creativity,” she said. On the cusp of leaving academia altogether, Gadeken said she found out about COA by chance. “I saw an ad come up for this small, interdisciplinary, community driven, and teaching focused college, and it was just hitting all the notes. I thought, They seem to be doing it the way that I think it should be done.”

After falling in love with seagrass, Gadeken fell in love with teaching. “During my postdoc work at Stony Brook University, I realized that full-time research was not really where my interests or desires lay. I discovered that I really enjoyed teaching, and that I really only liked doing research when it was with students,” she said.

As a teacher, Gadeken finds that students learn best when they’re set loose.“My job is to remove barriers to students becoming their full selves. Teaching, at its best,

Gadeken, who holds a PhD in marine science from the University of South Alabama at the Dauphin Island Sea Lab, said that she has really enjoyed the tight-knit community feel on campus, and that the community emails that keep students, staff, and faculty in touch with each other have been really grounding. “It’s interesting to hear these little bits and pieces from people's lives and experiences here, as diverse as they are.”

When she’s not teaching or studying seagrass or sediments, Gadeken likes to swim. She hopes to get involved with the YMCA in Bar Harbor to offer swimming lessons and maybe even start a synchronized swim team. “I swim a lot. I was a synchronized swimmer for a very long time.” Chuckling, she added, “Now it's called artistic swimming, but I have opinions about the name change that we don't have to get into.”

Whether it’s in the YMCA pool or in a tidepool, Gadeken is eager to do her part in a place seeing such rapid ecological change. “That's part of what drew me here—and also there's a lot of mud up here, and I really like mud.”

By Jeremy Powers ’24

DUC HIEN NGUYEN has just bought themself a car. Having lived in cities most of their life, it’s the first car they’ve ever bought. They need it to get around Mount Desert Island and to College of the Atlantic, where, as the new Cody van Heerden Chair in Economics and Quantitative Social Sciences, they’ll spend the coming years teaching young human ecologists that economics is about more than dollars and cents.

“We need radical socio-economic change, and education is one of the most effective paths towards peaceful change,” Nguyen said. “The changes that we need should be informed by a new way of thinking that emphasizes not so much the individual quest for maximizing profit, but deals more with what we actually value as people, as community, as society.”

Nguyen’s interest in exploiting alternative methods of visualizing and studying economics blossomed after they graduated from the University of Toronto and landed a job as an economic consultant. It was then that Nguyen experienced the lack of nuance surrounding questions of privilege, gender, and power dynamics in mainstream economic thinking.

“Conventional economics tends to take for granted the distribution of power, the distribution of resources. It doesn’t ask dynamic questions. It assumes, for example, that some people are rich and some people are poor, but it doesn’t consider how that division between rich and poor came about in the first place,” they explained. “To me, it’s not interesting.”

leading the student to think a lot more about how we can change this interplay. We’ll start with foundational economic theories and concepts, but then we go further and look behind the scenes to see what’s there and what we can do about it.”

So far, Nguyen said, they’ve really enjoyed the class discussions they’ve been having as students work through the process of dissecting economic models. “Folks have appreciated the insights that economics theories and models can provide, while remaining clear-eyed about the models' limitations and potential for misuse,” they said.

What does interest Nguyen is building a new generation of young economists who are conscious of these important ambiguities. “Political economy really focuses on the interplay between money and power. I focus on sort of

Nguyen’s next two classes are an introductory class on macroeconomics and a class titled Conversations with the Ghost of Marx, which will look at the global variants of the capitalistic economic system through a Marxian lens. For the spring, plans are still a bit loose, but they said that they’re interested in teaching a class on the economics of data and artificial intelligence.

“College of the Atlantic really embodies the kind of community that I value. We really truly care for each other; we do not value marketability and profitability so much that we are trampling upon the most magical people to make way for ourselves. That's not the ethos and the ethics of this community,” they said.

Nguyen holds a PhD in economics from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, a master’s degree in economics from the University of Toronto, and a bachelor’s degree in economics from Trent University. In their free time, this economist likes to play RPG video games and listen to Dungeons and Dragons podcasts. “The sci fi, fantasy, fiction world is my escape,” they said.

By Biya Gondal ’28

WHAT BEGAN as a College of the Atlantic class project exploring the history of apples in Maine has evolved into groundbreaking research uncovering rare, centuriesold apple varieties. Working in collaboration with several partners, COA history professor Todd Little-Siebold and his COA Maine Apple Lab have embarked on a journey towards rediscovering the forgotten ancestors of American apples.

The discovery of a rare French apple in the nearby Penobscot River Valley is one of their most exciting fi nds. The apple, which may have been continuously propagated since the 1600s, is possibly among the oldest continuously grown apples in America, Little-Siebold says, and possibly one of the most signifi cant French ancestors of modern American apples.

Through DNA testing, which involves collecting leaf samples and comparing them against a vast international apple

database, the team was able to determine that the apple is a very old French variety that may have been planted by early French settlers in the region in the 17th century.

The discovery highlights how modern scientific advancements can illuminate the past, bridging centuries-old agricultural history with cutting-edge research.

“Without DNA testing, we would have never identifi ed this apple,” says Little-Siebold. “Normally, we rely on matching fruit to historical descriptions, but this particular apple would have been impossible to identify without the science behind it.”

The apple's survival tells a remarkable story of resilience. Along with others found through similar genetic detective work, Little-Siebold says, it highlights the importance of preserving genetic diversity in apple varieties, particularly in

the face of climate change. In fact, this apple’s rare genetic lineage may hold crucial answers for adapting modern crops to future environmental challenges.

“Somebody’s kept it going. They passed it from generation to generation to generation over 400 years,” Little-Siebold says. “That tells you something about how they valued it.”

Further research will hopefully turn up other such apples in the area, which is one of the longest-settled regions of Downeast Maine, he says. Nearby Castine, historically called Pentagoet, was inhabited by French traders and farmers who lived alongside a Wabanaki community for well over 100 years before the English moved into the area around 1760.

In addition to uncovering these rare apples, Little-Siebold and his team work closely with the Maine Heritage Orchard at Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association,

which serves as a preservation orchard for over 400 historically significant Maine apple varieties. This partnership between education, preservation, and genetic research is integral to maintaining the rich history of Maine’s orchards and educating future generations about the importance of preserving heritage crops, he says.

“We're really focused on the research and historical documentation… and they’re really focused on the preservation,” he says. “It’s the perfect complementary work.”

The discovery of these rare apples isn’t just a victory for history enthusiasts or orchardists—it’s a testament to the deep connection between food, culture, and the land.

As research continues, the COA team is on a quest to uncover more lost apple varieties, contributing to a better understanding of our agricultural roots and inspiring future efforts in crop preservation.

The College of the Atlantic Maine Apple Lab engages in historical research, uses genomics to build profiles of heirloom apples, and networks with preservationists around the country and the world.

The lab’s purpose is to contribute to the conservation of heritage apples by tracking down, documenting, and solving the mysteries around their origins. They are helping to reconstruct the history of apples in Maine and America generally to inform conservation strategies.

The lab’s work combines molecular techniques with traditional historical research and fieldwork to rescue and document apples that are the rarest of the rare from around the COA region.

The lab collaborates with the Maine Heritage Orchard to propagate and preserve the rarest and most unique apples from around the state, the Cameron Peace Lab at Washington State University Pullman, and the Historic Fruit Working Group of North America.

Photos by Todd Little-Siebold.

By Eloise Schultz ’16

Written for the inauguration of COA President Sylvia Torti and read by the author at the ceremony on October 20, 2024

When the priests sold this property for a dollar to the college, do you think they knew what would come to be here?

One might think that they lived in unobtrusive ways, in days of solitude and silent prayer, but that’s the trick of the pastoral to soften the audacity of history. Come upstairs with me

to the library window, I’ll show you where their giant neon cross once stood, a beacon for boats crossing Frenchman Bay.

In its place, the first hopeful students built a windmill, which ignited years later from the friction of its own movement and left a flat ring of stones which now faces, across the bay, an array of modern turbines, turning steadily.

Ours is the story of beautiful failures and our faith in what follows. Every ruin beneath your feet stings of those who arrived and laments those who were forced to leave; those who cut the paths and laid the tracks, paved the roads and stacked the stones that lined the sidewalk on your first walk to school, as someone took your hand and held hope and grief in the other.

The earth now is as noisy as it’s ever been. Never has it been harder to hear the calls of birds or the commotion of insects, the ocean’s chatter drowned out by engines of trade, the flow of water long since turned to the flow of money and endless interest.

But these ways of living are not inevitable. Beneath those mountains are even older mountains. Behind this sentence is a door we haven’t seen before.

Three miles from here, there’s a path in the forest leading to the crumbled stones of an old estate atop granite scraped by glaciers and glazed by fire.

A porcupine lives there, and a fox, regarding each other from mossy dens on either side of the collapsed road. I’ll take you there, after it rains, to smell the sweet

firs and see the few chanterelles emerging steadily from the litter of oak leaves, to climb carefully down the steps

and find the moldy old boot perched atop a stump in an empty grove, a stage in the forest’s theatre.

There’s a common ground for us here beyond priests and robber barons, a place where actors and audience

change places: in the classroom, the field station, the auditorium. Here, generosity is our greatest

asset, and our inheritance not something owned but shared in how we tend and attend each other.

Where a child brings a box to the wildlife vet and removes the lid to show a monarch butterfly

whose fragile wings are torn. So small it is, beside the cages of bobcats and eagles; small like that child’s hands

in one moment in time, in one small place. Such a small thing couldn’t make a difference. Something so small is all that makes a difference.

By Rob Levin

AN ENERGETIC and heartful ceremony marked the inauguration of Sylvia Torti as the eighth president of College of the Atlantic. Hundreds gathered on the North Lawn October 20, 2024 to cheer Torti on as she laid out her vision of COA as the future of education. The day included keynote speeches from Deep Springs College President Emeritus and University of Utah Professor Emeritus L. Jackson Newell and University of Utah Inaugural Dean of the School for Cultural & Social Transformation Kathryn Bond Stockton, as well as an original poem written for the occasion and read by poet Eloise Schultz ’16.

“Sylvia Torti is an educator, a nurturer, instinctively advancing everyone around her,” Newell said. “Today, we celebrate the appointment of a new leader, someone who lives the narrative, breathes the spirit of art and science, and knows the competing demands of both discipline and freedom. A perfect match.”

Torti, an accomplished writer, ecologist, and innovative academic leader, was invested by COA Board of Trustees Co-Vice Chairs Marthann Samek and Hank Schmelzer, with Schmelzer placing a medallion with the COA seal around Torti’s neck. The seal includes three runes representing humans, earth, and water.

“COA—with our tradition of being a benchmark for change and addressing the challenges facing current and future generations—represents the future of education,” Torti said. “Here at COA, we fulfill our yearning to connect with one another and with the marvelously diverse more-than-human world. Ultimately, it is our sharp and adaptable, ecological minds, shaped by this connected education, that will allow us to discover new ways to flourish collectively.”

Also involved in the ceremony were COA Provost Ken Hill, Associate Dean of Faculty Kourtney Collum, trustee and member of the presidential search committee Cynthia Baker, and Board of Trustees Chair Beth Gardiner.

Torti previously served as dean of the Honors College at University of Utah, where she initiated and implemented a vision for globally oriented, integrated curricula in ecology, health, and human rights. Before that, she was the director of the university's remote, 400-acre Bonderman Field Station.

“Today marks a beginning, but in reality, it’s just a continuum of everything that COA stands for,” Gardiner said. “In a complicated and often confusing world, the values of COA are more important than ever, and we feel extremely fortunate that we found, in our new president, someone who feels our values as strongly and passionately as Sylvia does.”

Fall term All College Meeting moderator Keenan

Ovrebo-Welker ’27 provided opening remarks, followed by Schultz’s reading of One Small Place

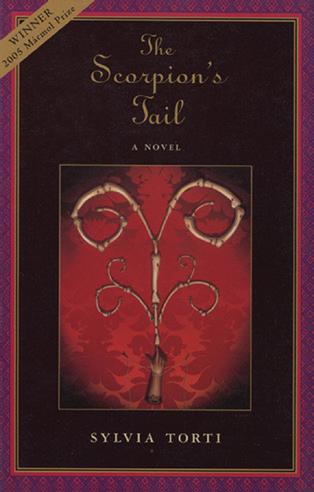

Torti has published multiple scientific research papers, research and opinion pieces on methods of pedagogy, multiple short stories and essays, and two novels: Cages (Schaffner Press, 2017), winner of the Nicholas Schaffner Award for Music in Literature for a novel, and The Scorpion’s Tail ( Curbstone Press, 2005), winner of the Miguel Mármol Award for a novel.

Past COA presidents in attendance included Steve Katona, Darron Collins ’92, and Andrew Griffiths. The audience included dozens of Torti’s friends and family members, along with trustees, alumni, students, staff, and faculty. Attendees enjoyed a reception in the Newlin Gardens following the ceremony.

Earlier in October, a southern Magnolia tree was planted on the seaside lawn of The Turrets, COA’s iconic, castlelike administrative building, in honor of Torti’s inauguration. COA Head Gardener Barbara Meyers ’89 said the species selection was a daring but well-reasoned experiment as the college anticipates climate change on campus.

Torti, who is from a bicultural Latinx background, has lived and worked globally. She holds a PhD from the University of Utah School of Biological Sciences and a BA from Earlham College. She began her tenure at COA on July 1, 2024.

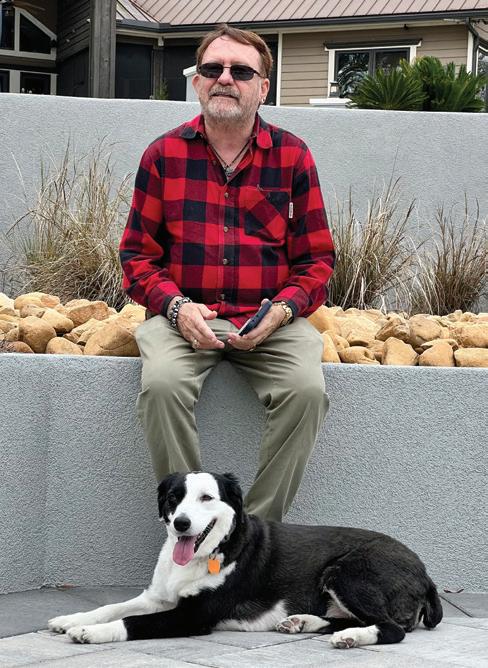

Torti is joined by her partner, Scott Woolsey, a blind triathlete who has achieved significant milestones in his athletic career. He secured the title of Ironman 70.3 World Champion in 2021 and went on to become the Ironman 140.6 World Champion in 2022. For the past several years, he has been teaching first-year colloquia and serving on the leadership team to design integrative first-year experiences at the University of Utah. He is a motivational speaker and a farm-to-table food expert.

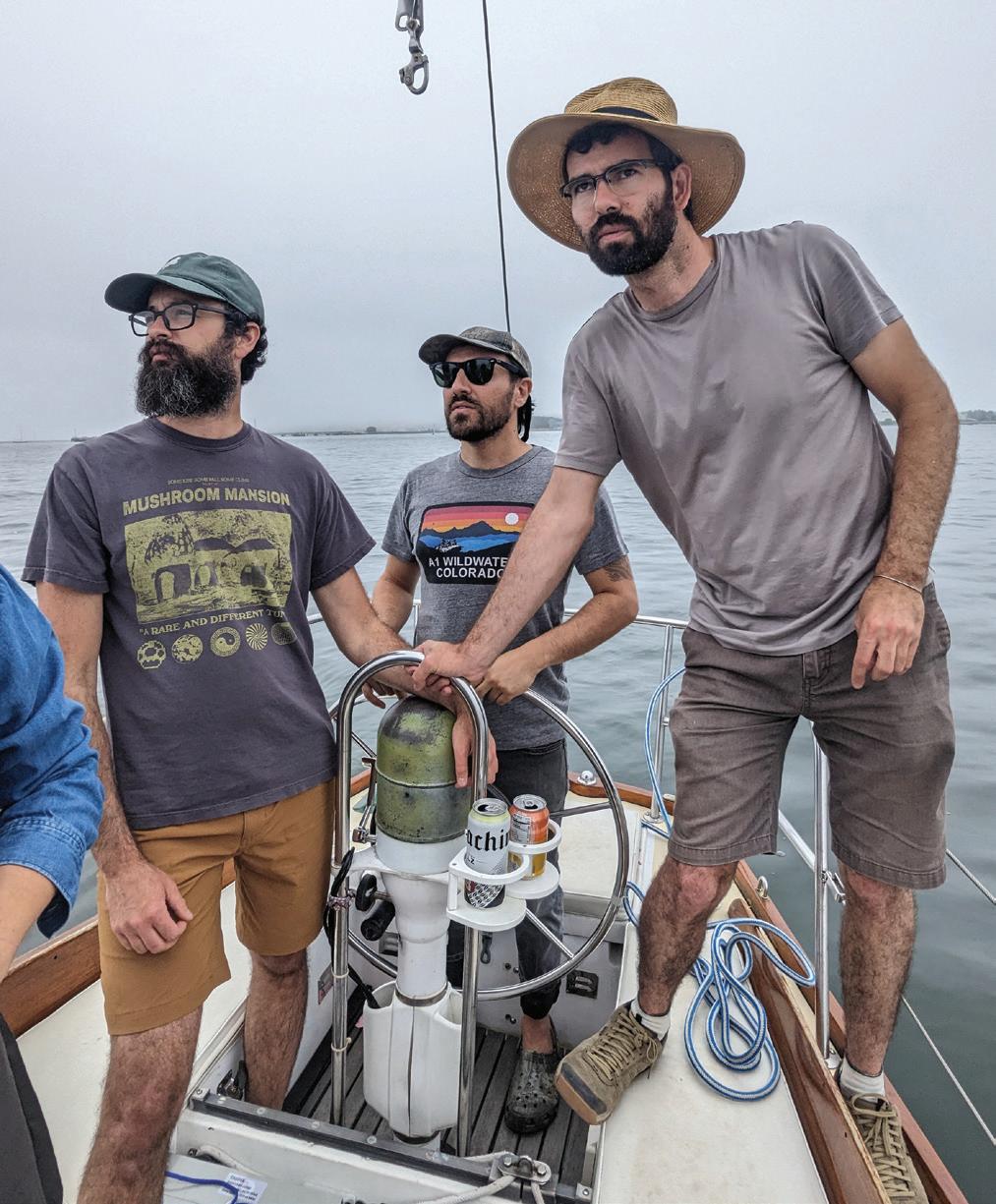

By Kiera O’Brien ’18

W HEN FRIENDS Matt McInnis, Jon Carver, and Eliah Thanhauser, all class of ’09, hatched a plan to start a mushroom farm in 2014, they weren’t sure where the idea would lead. “We had all taken different paths after COA,” says McInnis. “Eliah had been managing organic farms, I was freelancing as a photojournalist, and Jon completed a master's in mycology. But eventually we each found our way back to Maine.”

Putting their heads together over a few glasses of wine at a small Portland cafe, the friends considered their overlapping interests and divergent capabilities.

“We figured out which pieces of our very different skill sets could work synergistically together,” explains McInnis. They found common ground in fungi.

“We rented the cheapest commercial space we could find on Craigslist—it was basically a shack, it didn’t have a sink, hardly had electricity—and we turned it into a little mushroom growing operation where we grew edible oyster mushrooms in five-gallon buckets,” continues McInnis. “We sold the oyster mushrooms to local Portland restaurants, and that’s how we started.” They named their nascent operation North Spore.

For Carver, co-founding a business with McInnis and Thanhauser was driven by a collaborative impulse rather than entrepreneurial ambitions. “We stumbled into it. More than anything,

I think we wanted to stay connected and create something exciting in the world together,” he says. Thanhauser agrees: “We wanted to build a community like the one we had all found at COA, to continue learning with and from each other.”

“At the time, I figured North Spore was a cool summer project, or maybe a yearlong thing,” McInnis shares with a laugh. “I didn’t think it was a 10-year plan!” A decade later, North Spore has become one of the USA’s largest suppliers of mushroom-growing equipment and is an industry leader in the field of mushroom cultivation and research. With a team of more than 70 employees and a mission to “make the world of mushroom cultivation accessible to all,” North Spore operates on a vertically-integrated model, meaning that all of their mushroom spawn—the equivalent of seed for mushroom growers—is cultivated inhouse. While the vertically-integrated approach has been part of their model since day one, the five-gallon buckets are long gone. Thanhauser, who oversaw the construction efforts, is especially proud to share that the company now operates a state-of-theart mycology laboratory, housed within North Spore’s very own 25,000-squarefoot production and fulfillment facility in Portland.

The co-founders’ shared commitment to collaboration and education has

proven integral to the company’s success. “Since the beginning, education has been a hallmark of what we do at North Spore,” says Carver.

“After completing my master’s in mycology, I realized that I could spend many more years in school to become an expert within one very specific aspect of the field. But that felt too slow, too narrow. There’s so much to explore in the field of mycology—which is still very much in its infancy in many ways. I wanted to create something that facilitated a broader approach to research.”

This ethos, cultivated in all three co-founders during their time at COA, fuels North Spore’s innovative mission to meld business, education, and community-driven research.

“Everything we do at North Spore is about forging a path for people to engage with mushrooms,” elaborates McInnis, now the company’s creative director. Not only does North Spore create a broad swath of digital educational content aimed at empowering people to grow their own edible and medicinal mushrooms, but it also facilitates a research partnership program, led by Carver, who serves as the company’s lead mycologist. The program provides resources and “materials to aspiring researchers, gardeners, farmers, and individuals with mycological inquiries.” In exchange, says Carver, “North Spore shares our research partners' discoveries with our broader

community, all in the service of expanding the collective knowledge base around mushrooms.”

Reflecting on what makes their decade-long collaboration tick, Thanhauser, now company CEO, points to a deep willingness to “change

one another’s minds, to disagree with one another, and then to find a solution that we couldn’t have figured out alone.” Carver concurs: “I can't imagine ever getting to this point without it being the three of us.” McInnis picks up the thread. “We’ve learned how to come to consensus

through conversations that are never dogmatic but are all about valuing other perspectives.” After a pause he concludes: “It’s our interpretation of human ecology in practice. And that extends beyond the three of us. It’s reflected in everything North Spore has accomplished.”

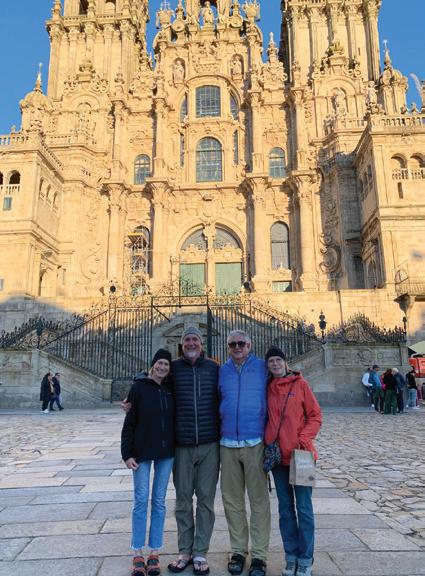

In fall 2024, COA offered a travel course to the Meseta in Spain. Students spent the entire term traveling the Camino Frances; a route traveled for centuries by pilgrims looking for answers, or, perhaps, pilgrims looking for different questions.

College education too often simply relies on secondary sources and the academic written word as the foundation for coursework. This course answered the question of what happens when students are immersed deeply in a new culture, a new place, a different language. The journey motif is often the structure of epic literature, but what if that epic journey is actual and what if the hero of that story is you?

Because the context of The Camino class was by its nature completely novel, our focus was on the internal change, the process, the raw physicality, the deep humanity of the journey.

At its core, the idea of this effort is human ecology in action. We stripped away many of the creature comforts we have always enjoyed and carried our possessions on our back. We were alone with our thoughts, in a small group sharing experiences and developing skills that brought the mental, the physical, and the academic to life.

In a world of endless distractions where we juggle work, school, friends, family, and a steady stream of digital distractions, it is not easy to get time to reflect. The Camino offered a chance for 12 students to be with themselves and others as they walked the roughly 500-miles from St. Jean Pied-du-Port, France to Santiago de Compostela, Spain along the medieval pilgrimage route of the Camino Frances.

For over 40 days students walked 30,000+ steps a day, ate, rested, and sat with their thoughts as they moved from town to town alongside people from around the world on a similar journey. Students participated in the Camino Frances’ international community where people are open and willing to share life stories with fellow travelers. With origins as a pilgrimage route, walkers are often amid personal or professional transitions or working through tough issues and easily speak from their hearts and dive deep. This combination of openness and introspection meant that when students met other pilgrims, be it for a moment, a few hours, or over days, exchanges provided new perspectives and insights. A quick interaction could, at times, be the fodder for days of reflection.

Every day brought new experiences, discomfort, and challenges that built character and resilience as the weeks passed. Students embraced these opportunities.

The route was roughly divided into three sections delineating the journey: Body, Mind, and Resolution. Leaving France and adjusting to the daily routine, students and faculty felt the impact on their knees, ankles, and immune systems as they crossed mountain ranges carrying packs, sharing meals, and listening to ample snoring in communal albergues (hostels). The wide-open plains of the Meseta following Roman trade routes were mentally challenging as students walked through record-setting downpours that made normally hot and sunny Spain feel more like damp and cold Scotland. Throughout the trip, assignments facilitated exploration of their environs and themselves.

Students dove into the history and culture of the Camino with videos and presentations capturing their initial impressions of the journey. They also completed research projects ranging from botanical representations in art and soundscapes to reflections on grief and food systems.

As they walked, they completed guided mindfulness reflections as part of three overarching questions about their Camino journey and life:

What burdens are you carrying that you should put down?

What are you carrying that you wish to keep?

What have you seen that you wish to pick up?

The course extends well beyond the time on the Camino. For many, arriving in Santiago and returning to their lives marked the real beginning of the journey.

Caminante, son tus huellas el camino y nada más; Caminante, no hay camino, se hace camino al andar.

Al andar se hace el camino, y al volver la vista atrás se ve la senda que nunca se ha de volver a pisar.

Caminante, no hay camino sino estelas en la mar.

—Antonio Machado

Left, top to bottom: A fellow traveler on the Camino; enjoying fresh tortilla and wine in an albergue—COA students and other travelers from Germany, Latvia, Spain, England, and Denmark; strange sculptures outside of Villafranca del Bierzo. Above: Detail of the huge mound of stones and other objects surrounding The Cruz de Ferro. It is a tradition to carry a stone from your place of origin and leave it at the cross. Photos by Lila Foster ’26.

Walker, your footstaeps are the road, and nothing more. Walker, there is no road, the road is made by walking. Walking you make the road, and turning to look behind you see the path you never again will step upon. Walker, there is no road, only foam trails on the sea. (translation Willis Barnstone)

THE SUN ROSE in shades of pink along the red, rocky outcrops. Quickly enough, all turned blue. Hundreds of shades and hues of blue along the distant mountains and cloud-streaked sky. Golden thistle and a plum thistle, devil’s snare, chard. Abundant vineyards and the rare, special fig tree. Quinces as we entered the town.

—Skylar Bodeo-Lomicky ’26 (from a journal entry 9/29/24)

I’M SUPPOSED TO BE thinking about gratitude. I think gratefulness has been the biggest theme on the Camino for me so far. When I got sick in Logroño, I was overwhelmed by the kindness of my new friends who took such loving care of me, even though we hardly knew each other.

When I started walking again, I was so grateful for the simple act of walking, for being able to take part in the Camino again. Those first few days passed easily, and I had such a full heart for all my new friends. As the walking got harder, my gratitude for my legs grew. I look down at them while walking and just feel so much amazement for how far they have carried me.

I am grateful for how much I have felt during this short time: so much love for people I hardly know, so much sadness in saying goodbye. Last night, we drank wine and played guitar into the night at the albergue. All of us singing joyously and drunkenly. It was so silly and loud and beautiful.

—Lila

Foster ’26 (from a journal entry 10/9/24)

Join us on campus this August for an internationally themed Alumni Weekend. We are celebrating the 30th anniversary of our Yucatán Program and the 25th anniversary of the Davis United World College Scholars! Reunite with your friends to celebrate these significant COA programs.

Bring your families, stay in the dorms, eat in TAB, and join fellow alums for activities including receptions, trips on M/V Osprey, visits to COA Beech Hill and Peggy Rockefeller

conversations with special guests that engage the audience in thought-provoking discussions. Past speakers include authors Christina Baker Kline, Kim Stanley Robinson, Margot Lee Shetterly, historian David Hacket Fischer, CEO of The Atlantic Nick Thompson, Chase Morrill ’00 of Maine Cabin Masters, and many others.

The Northern Lights Society was established to recognize and thank COA friends who have made planned gifts to the college. These gifts include bequests, charitable gift annuities, and gifts of life insurance. Members are invited to our annual summer gathering (see last summer's gathering at Beech Hill Farm on page 80). If you have made a planned gift to COA, please let us know so we can add you to the invitation list.

To learn more about making a planned gift to COA, please contact Dean of Institutional Advancement Shawn Keeley ’00 at 207-801-5620.

ASA KID from Houston, Texas, arriving at COA in the dead of winter was startling, to say the least. Now that I do winter dips in the ocean next to our school, I’d say it’s actually not too bad! However, I’d still recommend swimming with a buddy just in case. Another recommendation from experience is not to schedule your classes on the same days (especially with work-study and more jobs) like I did this term. And as I reflect, there might have been more than just a few small victories since I've gotten here. Coming to COA has pushed me beyond what I once considered my limits. Each time that happens, I feel like I've been reforged for the better. Without really realizing it, I have grown as a student, a friend, and a person.

Introduction to the Legal Process with Ken Cline. Phew. I don't know when I started to want to be a lawyer. I knew that on TV, the law is used for its dramatic potential and actual law can be more than soul-draining; still, I saw enough appeal to strap myself to the rails. Kidding. I had a more civic background in high school and made the pivot to science in college. I realized that my biology studies were interesting, but I still had a humanities itch from my previous work. Those topics aren't exclusive per se, but I wanted to more explicitly combine them. I thought, Maybe become a patent attorney! When Ken's class came around in the spring, I knew I had to sign up and see if I could really do this. And the final moot court really sold it to me; dry readings and writings aside, having to hash your points out to judges was really fun. As of now, I'm getting more into environmental law and it's kind of kicking my butt. Hopefully, everything will work out!

DURING A BUSY summer, I was balancing a 50-55 hour work week between the MDI Biological Laboratory, Take-A-Break, and The Burning Tree restaurant. My decision-making abilities were, understandably, stretched thin. I was moving into my summer housing and found a large grassy rug in the COA free box. I loved the rug, so I set down my uncovered plate of meatball subs on a bench outside, and carried the rug to my room. I returned to my plate to fi nd it absolutely demolished. It was the worst crime scene I’ve ever seen. The plate was face down and the buns and roasted veggies strewn erratically on the ground. I wanted to call 911. Upon further investigation, the trail of food innards led to a tree... Perhaps this sandwich thief made an arboreal getaway. But who? A squirrel, that's who! I discovered squirrels ate more than just acorns that day. Challenge your beliefs, hope for the best, and prepare for the worst.

Introduction to Songwriting was my first break from scienceheavy trimesters. Instead of three-hour labs for each class a week, I was writing original song lyrics and belting them out in a studio. I loved the euphoric feeling flooding my lungs after singing for hours in the high school choir. While I had covered pre-existing songs, I’d never composed an original piece and performed it. My favorite piece I wrote would have to be a song called Southern Spice. I created it from the perspective of a person from a politically tense southern state that has its own intrinsic beauty and culture. Even though my hands shook and dread pooled at the bottom of my stomach, I performed it. And I was ultimately relieved since it was well received. Some people even complimented me the next day (*squeal*). This class gave me a chance to revisit a passion that I left on the back burner for way too long. Caroline Cotter really pushed us to validate our inner creativity and destroy the doubtful critic in our minds; a lesson that reaches far into other parts of my life.

Jay

Kerri

I started Personal Finance and Impact Investing with Jay Friedlander because I thought that some financial literacy couldn't hurt. I'd say some of the biggest takeaways are compound interest and keeping records. I was surprised that this class wasn't just a numbers game. The number of readings that talked about the economy in relation to society, politics, and environment was impressive. Very human ecology. It was also interesting to see how money could be contextualized and used to support personal missions. I don't know if I'd ever join the FIRE ["Financial Independence, Retire Early"] movement but if I ever get rich enough to have an investment fund, it's reassuring to know that there are managers that make it a priority to invest in sustainable companies. Now to find an angel investor for my college tuition.

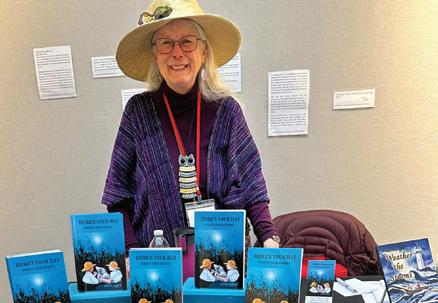

By Kiera O’Brien ’18

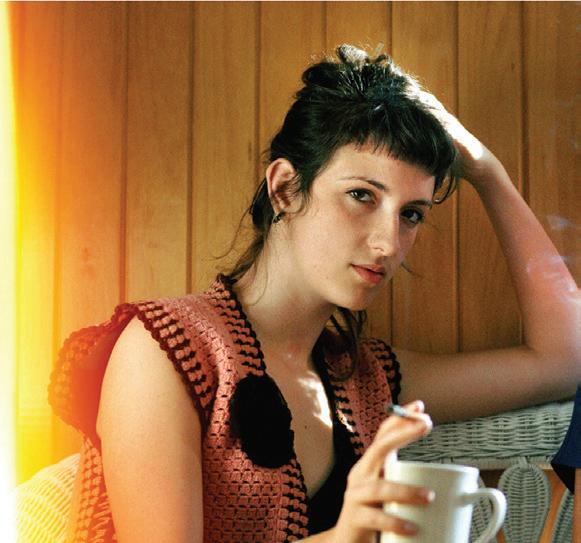

ASAN EMERGING WRITER still finding my creative footing in the world, I consider myself exceedingly lucky to share at least three uncommon affinities with writer Jenny George ’02. We are both poets who came to our craft by way of human ecology; we both now call the high desert foothills of Santa Fe, New Mexico home; and we both spent four years soaking up words and ideas—about literature, gardening, the world that is and could be— advisees of COA Lisa Stewart Chair in Literature and Women’s Studies Karen Waldron during our separate stints at COA, more than a decade apart.

George’s stunning debut collection, The Dream of Reason (Copper Canyon Press), was published in 2018, the same year that I received my degree from COA. I read it with a mingled sense of awe—at its artfulness, humor, and precision—and gratitude for its sheer existence. I didn’t yet know George personally, but reading her poems I felt less alone, bolstered by the evidence that someone else had so eloquently set out to be a working poet and a degree-holding human ecologist. It’s not as common an undertaking as perhaps it should be.

In the conversation that follows, George reflects on what it means to be a poet trained in human ecology, the ethical imperative of remaining “tender and permeable and aware” in the midst of a world that increasingly compels us to be otherwise, and her remarkable new book, After Image, published by Copper Canyon Press in 2024.

How did you find your way to COA, and to poetry?

I thought I wanted to be a marine biologist. But then it turned out I get sick on boats! Also, I thought I wanted to study biology because I was interested in how life works, in the deep nature of our world. At 18 years old, when I arrived at COA, I had only this one idea of how to take up that inquiry: I’ll be a scientist, and I’ll look really closely at the world, at animals, and plants, and ecosystems, and so on, and I will find answers. Then I did a summer internship where I spent many hours tucked up inside a tiny bird blind on stilts, a few feet from the ocean, and I was meant to be counting birds,

acquiring data for a research project. But I spent most of those hours daydreaming and writing poems in my field notebook. My actual allegiance to the hard data was tangential to say the least! In the end I was most interested in the questions themselves, and in the experience of asking. So I switched my academic focus to literature and poetry writing and philosophy.

How did your time at COA shape or inform your writing life? What does it mean to you to be a poet trained in human ecology?

Human ecology is the best training I can imagine for being a poet! Or maybe what I mean is… poetry is the best training for being a human ecologist? Because what poets and human ecologists both know is that there is a meaningful relationship between the individual and the context, between the subject and the environment and the moment. Both poetry and human ecology understand that everything is situated, that everything real must experience the constraints of place and time and the entanglements of relationship. I try to write poems that honor and evoke the realness of things, through language.

What do you still carry with you, from your time at COA?

Something like: Each little thing matters. An understanding—although it’s not purely intellectual, it’s more of a persistent hunch— that everything is stitched to everything else. Interpersonally, ecologically, spiritually, systemically… it’s all reciprocally connected. I carry that from my ecology and biology classes, but also from the principles that pervade life and learning at COA. How lucky are we to come out of an institution and a community like this—that has such an ethic of caring?

Writing, and perhaps poetry especially, are often framed as solitary art forms. Does this hold true for your practice? How does reciprocity feed and enliven your poetics, if at all?

Reciprocity is fundamental to my practice, absolutely. It’s true I am usually physically alone when I’m working, when I’m actually writing things down in the particular way we call poetry. But I write for real others. I write towards the people on the reading and listening end of the literary encounter. The practice would have no meaning without them.

You know how they say a good relationship is 50/50, like with a friend or partner, when it comes to sharing labor or space? For me, the ideal relationship of poet to reader is 100/100. Meaning I try to be fully there when I’m writing, 100% present on the page and in service to the endeavor. And I hope the reader can be fully there, too, in the encounter with the poem. That is to say, I hope my poem invites and earns that depth of engagement with others. If it’s a good poem, then I think it can.

Tell me about your new book, After Image. What central questions animate this collection of poems?

A few years ago a very significant thing happened in my world, which was that my partner of many years died. That experience was— whatever else it was— incredibly mysterious, upending, radical, and baffling. It left me with big questions: Who does death ask us to be? What could it look like to be totally uninsulated from knowing about mortality? What are the limits of transformation? These preoccupations led to the poems in the book.

As much as it is about the irrevocable absence of a loved one, this collection is crowded with nonhuman presences: from bees, to snow and wind, flowers, the seasons, an orchard, a garden. How did these particular presences come to populate this book?

The short answer is that those beings were actually there when I was working on this book… the bees visiting my garden, and the fruit trees coming into bloom, and so on. The morethan-human world is always present, no matter where we are or what we’re paying attention to. And also because it’s hard to show loss in a poem. I hoped that by describing the presences around the edge of it, the feeling of absence would be more palpable.

Nature abounds in your writing, but it is a proximate nature, not quite pastoral but not romantically wild either. There’s intense intimacy in the way you write about the natural world. I keep returning to the line in Mushroom Season: “Everything has a voice, / even if low, diffuse—or / outside human hearing.” Does poetry allow for a different kind of hearing, an orientation towards voices other than our own?

There seem to be many forces these days attempting to deaden our senses. It’s one of the projects of capitalism, of empire—to numb us and de-sensualize us, so we are better consumers and more obedient subjects. In contrast, the project of poetry is to wake up our senses. To make us tender and permeable and aware. We can use poetry—both the writing and reading of it—to keep our senses tuned. Which of course is also a political practice; a person with all her senses open to the world is less likely to stand for its ruin.

There is so much language these days surrounding us and numbing us with endless blah-blah-blah. On social media, in advertising, in mainstream politics, and so on. Mechanistic, transactional language. If the blah-blah-blah is like a veil that keeps us from aliveness, then poetry is a rip in the veil.

Tell me about the title of the collection: After Image. How did you arrive there?

Well, an afterimage is a phenomenon from optics or photography where an image lingers even after the stimulus is gone. It seemed like a good metaphor for the impact of certain kinds of extreme human circumstance, when particular images or events remain in present tense, with a kind of hyper-clarity. When it came to the experience I had of intimate loss, I tried to capture what was not just the retinal afterimage, but the imaginal one.

JENNY GEORGE ’02 is the author of The Dream of Reason and After Image, both from Copper Canyon Press, as well as the chapbook, * (Bull City Press). She has received support from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Lannan Foundation, MacDowell, and Yaddo. Her poems have appeared in Kenyon Review, The New York Times, Ploughshares, Poetry, and elsewhere. She lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where she works in social justice philanthropy.

KIERA O’BRIEN ’18 is a writer and artist based in Santa Fe, New Mexico. A graduate of both UWC Atlantic College and College of the Atlantic, she holds an MFA in poetry from the University of Pittsburgh. Her writing has appeared most recently in Denver Quarterly, Tupelo Quarterly, and New Delta Review. She is a proud alum of the COA Bateau Press editorial crew and now works as education director for Radius Books.

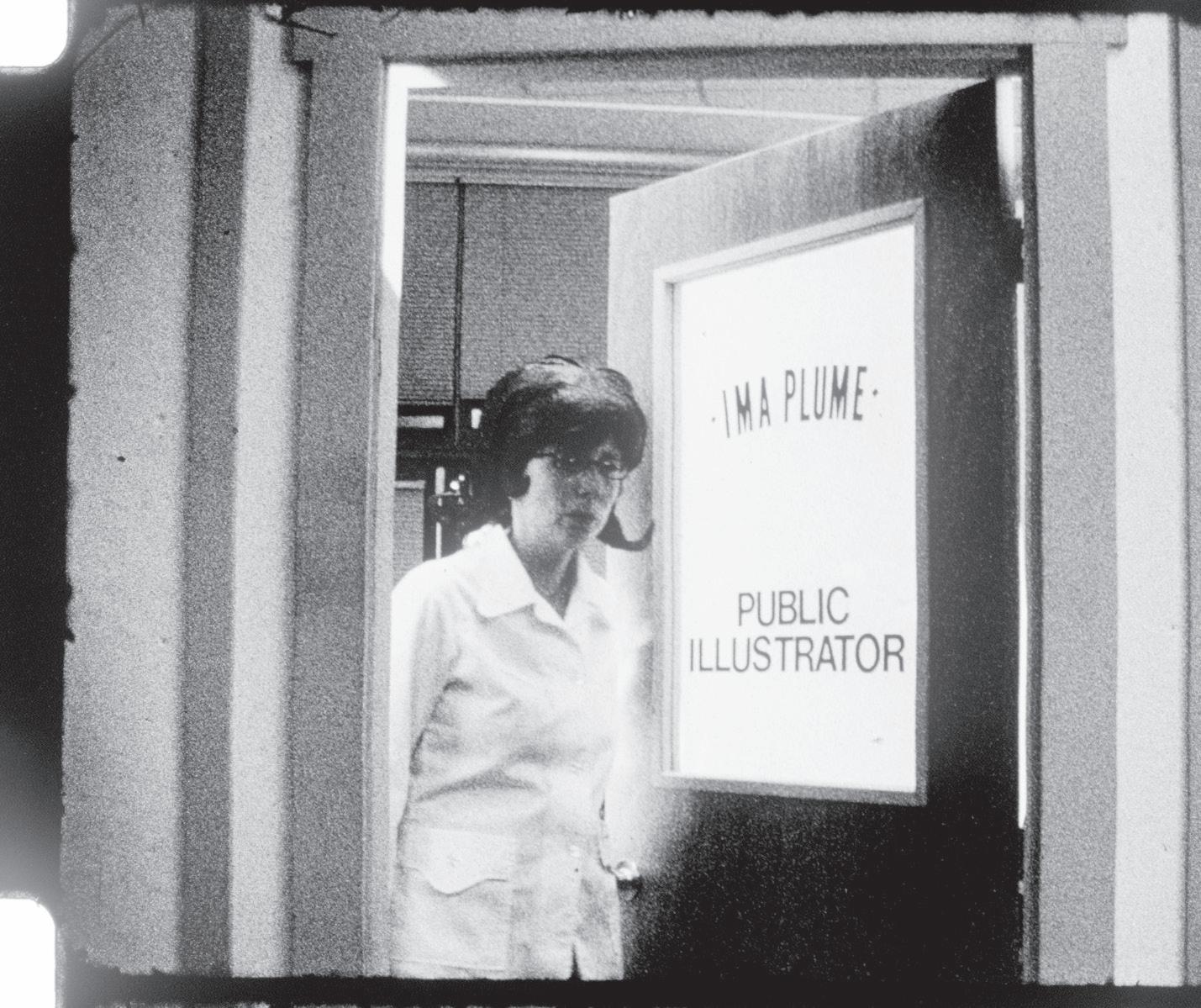

Ima Plume (voiceover): There were things I could draw pictures of, and there were things that couldn't be drawn. More and more I was attracted to the second category. There were things I wanted to describe, but I didn't know how. There were things that I wanted to show but there was no way to show them.

Radio interviewer: Welcome to the Shifting Science of Existence Program. This evening we are very pleased to present another in our series, “The Disheveled Mind.” I am very happy to speak today to Dr. Sheri Myes, our guest for this evening. She is a medical doctor with a degree in neuroscience from the University of Moravia and she is part of a private think tank on consciousness. What has your recent research led you to?

Dr. Sheri Myes: Our paradigm for consciousness is reductionistic. We believe what our five senses tell us, but there are very many other levels of perception that are beyond our innate sensory abilities. I have compelling evidence that we can go beyond the “now” we know. And, I am on the brink of developing a technique of expanding our perceptions and consciousness.

Radio interviewer: Can you talk about your studies and methodologies?

Dr. Sheri Myes: Well, I have not gotten much support for my work from the mainstream scientific community, so I have not been able to secure funding or permits for my work. I have been working at the margins, and using myself as a research subject.

Radio interviewer: What kind of experiments have you been performing on yourself?

Dr. Sheri Myes: They involve transferring to myself the neural pathways of insects, bats, and other creatures whose senses are more extended than our own. I am also working on grafting sense organs to activate the limbic system. My work is revolutionary.

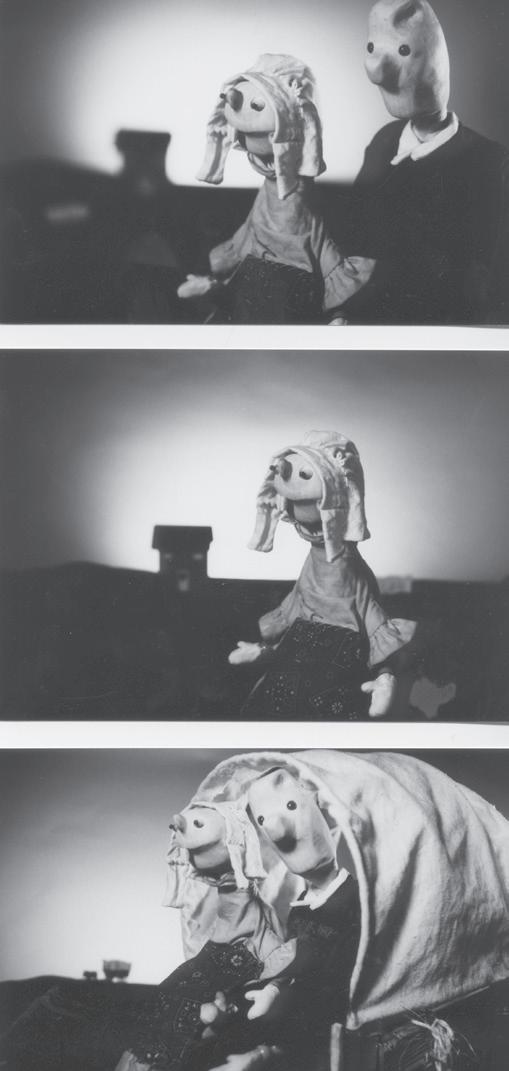

FOR ANDREWS, Mircea Eliade’s Shamanism was crucial in the film’s conception and in bringing us closer to a sense of emotional truth. Surveying shamanic initiation rituals the world over, Eliade identified several of its aspects common from one culture to the next: sickness and delirium; symbolic death of the neophyte; ritual dismemberment of the body; renewal of the organs; resurrection. Within these recurring threads, the filmmaker recognized uncanny parallels to her own encounter with death, as well as an imaginative framework for reconsidering that experience through the medium of film.

On a Phantom Limb hovers in an indeterminate zone, less a place than a state of consciousness. The avian imagery seen throughout is part of this—even more than in her previous films—where birds are quite prominent. In shamanic lore, birds often act as gobetweens moving from Earth to heavens to underworld; the film itself functions in much the same manner.

—Jim Supanick, from “Contemplating One’s Own Skeleton”

The Dreamless Sleep is a marvelous exploration of the possibilities of spiritual transformation. Sections of the film are interrupted by quotations of the five characteristics of St. John of the Cross’ “solitary bird,” the one that flies to the highest point, sings softly and has no color of its own. The flight of the bird represents the mystical ascent. This suggestion of possible heights is juxtaposed to the story of Elsa Bosselman, who drew pictures of deep sea creatures never before seen merely from phone descriptions given to her by William Bebee while in his Bathysphere 3,000 feet below the surface of the ocean. The theme is further played out by a paper puppet who enacts the imaginary life of Seint Cristyn the Mervelous (Saint Cristyn the Marvelous). The proper ambiguity is created about the meaning and possibility of this transformation.

—John Visvader (COA professor emeritus), from “Ima Plume Trilogy”

Though the protagonists in Andrews’ works form a continuing sequence of misfits, outcasts, mutants, and mavericks, they are always content to be as they are and manifest a sense of empowerment that seems to increase in each new film Andrews creates.

Although Myes is charged by the authorities with “inappropriate expression” and “interfering with the order of nature,” she has the confidence—paired with clarity of vision— to continue her experiments in hybridizing her own consciousness with the perceptive organs of a range of insects, spiders, and megafauna.

—Colin Capers ’95, MPhil ’09 from “Nancy Andrews’ Behind the Eyes are the Ears: An Appreciation”

When I watch Nancy Andrews’ work, I am calmly, curiously engaged, then something happens on screen, and I am suddenly deeply saddened, or deeply grateful for the beauty of the human condition. Nancy's work has a quality that is humble and beautiful, her awkward puppets and cardboard effects create a perfect gift that is somehow painfully telling about the receiver and the giver. Nancy Andrews’ films always leave me deeply amused, deeply moved, and deeply grateful for the little lives that make up the world.

Nancy Andrews’ films are small treasures, finely crafted, exquisite in subtle details and as rare as they come. Her cinema is artisanal—beautiful in its homespuness, expressive in its miscellany of hand-made images, whether drawn, animated, or acted, and sly in its humor. The art of performance is integral to Andrews’ short pieces, and disguise and masquerade are keen aspects of her Ima Plume trilogy, which is at once and the same time a meditation on the universe and a hoot.”

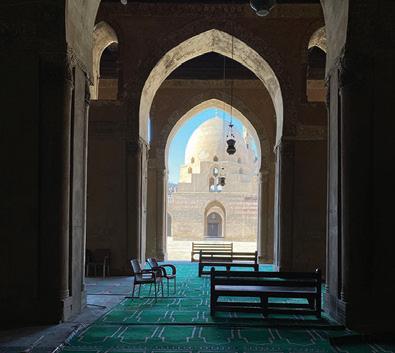

By COA Charles Eliot Chair in Ecological Planning, Policy, and Design Brook Muller

The setting: Late afternoon, early July, 2024. My friend and colleague May al-Ibrashy and I catch up while sitting under a trellis in a gathering area in the recently completed al-Khalifa Heritage and Environment Park. Kids chase each other on paths amidst birdsong, trees, and swings. The crippling heat of the city that surrounds us momentarily loses its hold, dissipating in the dusky smog.

IN2015, CAIRO UNIVERSITY architecture professor Nabil Elhady invited me to participate in a workshop focused on retrofits to low-cost, multi-family housing in 6th of October, a planned satellite city perched on the white desert plateau above the Nile Valley west of Cairo. We engaged CU students in systems-based design approaches for upgrading typical five-story, concrete and brick infill housing blocks to better suit the lifeways of those migrating from rural parts of Egypt (due to climate change impacts), with a focus on rooftop urban agriculture. One day during that first visit, Nabil introduced me to May, taking me to her studio in the al-Khalifa neighborhood of medieval Islamic Cairo, part of the Historic Cairo UNESCO World Heritage Site and readily locatable by the landmark ninth-century Mosque of Ibn Tulun (879 AD) marking the neighborhood’s northwest corner. A collaboration began shortly thereafter and continues to this day, including work on the park we now catch up in.

May’s practice supports an impressive breadth of community development projects through a potent alignment of heritage conservation, urban ecological design,

and the arts. Megawra Built Environment Collective and the associated Athar Lina (Heritage is Ours) initiative that she leads provide alternative models of practice for emerging Cairene designers. Khalifa Heritage and Environment Park intercepts groundwater from leaky pipes damaging two 13th century shrines across the street, buildings May and her team are working to restore. A novel approach intercepts the very medium causing harm to establish a much-needed open green space for women and children where nothing else like it exists. Given the enormous volumes of groundwater threatening heritage sites in alKhalifa, far more than needed for the park, the team now investigates more comprehensive, neighborhood scale water reuse focused on the formation of a chain of “green pockets,” and down al-Khalifa Street, the neighborhood’s main arterial, mini park spaces in alleyways and on rooftops focus on urban food production and evaporative cooling features. Taking advantage of underutilized assets such as plentiful water and acres of rooftops in a highly constrained context, and deploying an economy of “moves” to achieve richness of effect: this is the challenge at hand in transposing ecological design strategies to the city.

The opportunity to apply systems-based design principles in this magical yet precarious place (May describes Cairo as “the sublime mess”) informs the ecological design research studios I teach at the College of the Atlantic. More broadly, experiences in Cairo have engendered deep reflection on my role as an educator and what skills to nurture so students interested in design and community

development have future agency in collaborating effectively in complicated, multilayered urban settings. A key motivating question associated with this effort: How can a neighborhood of concrete and stone “regrow” as it confronts unprecedented change, climatic and otherwise? How can we vastly improve the environmental quality of urban settings while radically reducing energy and material consumption and extractive relationships with the nonurban settings—and peoples— that the city relies upon?

A related question energizes me: How can we use the privilege of time and space that a COA studio setting affords, not to mention the unique power of this institution’s humanecological approach, to engage in research—on passive (natural) cooling or urban agriculture as examples—that might be helpful to our colleagues on the ground? How can we contribute to transforming the city site-by-site (vs. massive scale developmentalist projects), taking motivation from architect Sim van der Ryn’s famous claim that the socioecological problems we confront reflect a failure of design. What roles can we play in advancing low-cost, low-carbon, low-energy measures in jerry-rigging existing

spaces and infrastructures to better support the lives of humans and nonhumans in times of great peril and change?

Experiences in Cairo have engendered deep reflection on my role as an educator and what skills to nurture so students interested in design and community development have future agency in collaborating effectively in complicated, multilayered urban settings.

These questions speak to a larger, critical one, so central to the mission of COA: What is the value of collaboration involving multiple disciplines, and how do we engage in it effectively? Here I share with students lessons learned in over 30 years of creative practice, and yet especially as a function of ongoing work in Egypt. The outlook operates as follows: We each bring ideas and skills to a given situation or problem, and yet we are not solutionist geniuses, arriving with answers (alas, such was a prevailing attitude in the architectural culture I grew up within). It is precisely this humble approach that enables us to do good work as a collective and, in the process, for each of us to hone our sensibilities and find our voices. I can think of no higher form of ambition and no better way to advance, as the anthropologist Artur Escobar describes it, a place-based globalism, a networked manner of working committed to replenishment on the ground.

Brook Muller was named a Fulbright Specialist in 2024 in honor of his human-ecological architectural work in Cairo.

By María Lis Baiocchi ’07,

Helena Shilomboleni ’09, Enrique Valencia Lopez ’11, Milena Renée Rodriguez ’14, Abigail Plummer MPhil ’16, Clément Moliner-Roy ’18, and Richard J. Borden Chair in Humanities Bonnie Tai

INANTICIPATION of my retirement from COA this June, I invited recently graduated advisees, former students who have kept in touch, and those whose senior projects or graduate theses I advised to discuss together a number of questions that I thought would interest all of us and readers of COA Magazine. What follows is a synthesis of this discussion; nearly all of us contributed to the continued conversation through the collaborative revision process. As a group, the alumni spanned the years 2005 to 2018, and attended COA from Argentina, Namibia, Mexico, Nicaragua, the US, and Canada. Not all of these alumni focused their studies on education, although all had taken at least one course with me. Other areas of interest and expertise include anthropology, entrepreneurship, food systems, Indigenous studies, gender studies, and quantitative research methods. All of us share interests in education and social, economic, and environmental justice. Each of us speak from our own experiences and do not presume to speak for others—former, current, or future students. Finally, authors are listed according to year of graduation in chronological order; beyond my coordination and facilitation, we share authorship equally. Bonnie Tai

In responding to how higher education has impacted them, some described how different their lives would be had they not pursued postsecondary education. María Lis shared, “It has shaped my life in profound ways. My life would be completely different if I hadn’t had the opportunity to go to university.” Helena, who is teaching in a Canadian university, observed from her recent professional experience, “The learning that you get at university… is not so much the knowledge you get from your professors… You learn to work with other people, meet timelines, [gain or hone] communication skills.”

For María Lis, Milena, and Enrique, COA opened up interests they hadn’t

considered pursuing through courses that influenced their path, including in Enrique’s case, the decision to pursue graduate studies:

The classes I took at COA were the fi rst systematic introduction to specifi c issues that have infl uenced the way I approached a specifi c aspect… questions related to race, related to climate change, questions related to food systems. Some have become personal interests and some have infl uenced to some extent the type of research that I wanted to do— for example, the idea of what motivates people to believe certain information or not.

COA didn’t just “shape [Enrique’s] aspirations; actually it changed them.” The role that peers played cannot be

underestimated. “Until I met several students, I didn’t think about going to graduate school. That made me wonder if that path was right for me and if I wanted to do the same,” he said.

María Lis’ preparation at COA also allowed for an easy transition to graduate school:

Given the training I got at COA, it was really seamless to go on to my master’s and doctoral degrees in terms of the demand of what was required of me as a scholar in training: taking ownership over my education, working independently. COA gave me so many tools.

Abby, Helena, María Lis, and Milena all spoke of the interdisciplinarity of a COA education as central to their learning. For Abby, it was difficult

to find a graduate program that combined her interests in education and food systems while also allowing her to complete requirements toward teaching licensure; ultimately her thesis allowed her to work across areas of expertise as she developed and launched a farm-based summer learning program in collaboration with the former manager of COA Peggy Rockefeller Farm, C.J. Walke, former professor Molly Anderson in food systems, Jay Friedlander in entrepreneurship, in addition to Linda Fuller and Bonnie in education studies. Helena talked about the value of the “hands-on, applied work” that she was able to do in various countries supported by the Davis Scholarship before completing a PhD at University of Waterloo. Speaking of how this applied learning has influenced her university teaching approach today:

“My assignments are very different, [for example] to write a grant proposal [to foster] deep learning… It’s not easy for university students to go to Tanzania so sometimes you have to bring that [place or perspective] to the classroom.” Referring to her time at COA, María Lis stated, “Interdisciplinarity was something that was ingrained in me at such a young age.” As a graduate student and now postdoc, she elaborated:

When I was completing my PhD in anthropology, I didn’t limit myself to working with faculty in my department. I also did a number of graduate certificates as part of my doctoral degree— in global studies, Latin American studies, gender, sexuality, and women’s studies, and cultural studies. My PhD studies, which focused on household work and household worker advocacy in the context of changes in labor law in Argentina, were superinterdisciplinary. The way I was taught to think at COA was a real asset; it made me a more flexible thinker.”

Abby valued specific skills honed from her COA education and how she has been able to teach these to her middleschool students:

Developing critical thinking skills and learning to look at things from multiple perspectives and respectfully debate them are skills that I’m trying to instill in my students as a teacher, and those are skills that COA develops in all of its students. That is a huge value of COA and higher education.

Her experience and study of democratic education at COA also influences what she tries to offer her students, including “the way that COA supports democratic education… to co-create their learning, to be able to give choice to what they learn, to feel valued and trusted.” As Helena also experienced and described above, courses outside of ed classes encouraged direct application in community contexts. Abby was able to develop a curriculum around sustainable energy and pilot it at a local elementary school while taking David Feldman’s Physics and Mathematics of Sustainable Energy “Those chances to step into action are really powerful and important.” Other hands-on activities also offered opportunities to apply learning, such as “co-coordinating the farm-to-school program.” Critical exploration is an educational approach that Abby valued the opportunity to learn while at COA. Abby observed, “I’ve had students say, I like how you don’t tell us the answers and let us figure it out. If I hadn’t gone to COA and gone through the ed studies program, I don’t know that I would have been able to do that for kids; even at fi fth grade, they are able to recognize that as unique to them, to their experience.”

A challenge most felt that COA faces today is ensuring that graduates don’t feel that they must pursue graduate studies in order to be prepared to enter the workforce. As María Lis noted, “It’s the perfect environment for students to become excellent ethnographers or social science researchers more generally without going on to further

studies, because it’s so small. Students in the natural sciences get training on how to write papers and how to publish to have a successful career without the need to go to graduate school, and the same could be done with students interested in social research.” However, not every student will have this kind of mentorship depending on their area of interest due to the small faculty and limited breadth.

Enrique noted a few related challenges and opportunities associated with preparation for academic work:

Keeping up to date with the new methods or the new fields in the social sciences and humanities might also be a little bit of a challenge because they move so fast and require strong connections with industry (e.g., machine learning, AI, the development of new materials). One of these challenges is to balance the goal of working with the community at the same time as creating these broader links with industries and organizations outside of Maine that can contribute and improve COA’s methodological [studies] in the curriculum. This is part of a challenge given the location of the school… I remember there was this strong emphasis on trying to work with farmers and fishermen and women. I think establishing and continuing these connections is crucial, but expanding them is also important.

As the only discussant who completed the teacher licensure program, Abby noted the education program as an exception: “Ed studies stands out in providing the certification program; if you follow that pathway, it can lead to direct employment” after graduation, should you decide to apply for school teaching jobs.

An alum who contributed written input noted the following:

Interconnected challenges like climate change, increasing polarization, pandemic

recovery, threats to democracy, and growing socioeconomic disparities continue to amplify and complicate each other. COA, as an interdisciplinary island school with a high international presence and strong commitment to social and environmental justice, has a unique opportunity to be a leader in fostering students’ capacity to lead resiliencebuilding efforts through these challenges across disciplines, arenas, and communities throughout their lives.

Part of a challenge I see is building leadership that can resist the forces of polarization and extremism. In a time where divisions are deepening, I think it’s really important to keep in mind the large-scale social cohesion and collaboration needed to address these crises.

I think building the community’s capacity to bring together diverse perspectives and foster collaboration across opposing viewpoints will be essential in leading the way through these complex, interconnected crises.

In reflecting on the unique paths students often take at COA, Bonnie interjected that not every student can afford a “trial and error” approach to course selection.