Adam Ha milton

Adam Ha milton

Why Did Jesus Have to Die? by Adam Hamilton

Journey through one of Christianity’s most profound questions with renowned author Adam Hamilton. This theologically rich study explores the meaning of Jesus’s crucifixion, examining salvation, atonement, and the transformative power of Christ’s sacrifice. Perfect for groups seeking deeper understanding of the heart of Christian faith.

In addition to the book, other study components include a Leader Guide, DVD, and Sermon and Worship Download.

Preview the first session on Amplify Media on HERE.

The Last Supper by Will Willimon

Join beloved preacher and scholar Will Willimon for an intimate examination of Jesus’s final meal with his disciples. This character-driven study brings the upper room to life, exploring themes of betrayal, forgiveness, servanthood, and holy communion that resonate throughout the Lenten season.

In addition to the book, other study components include a Leader Guide and DVD.

Preview the first session on Amplify Media on HERE.

An Unlikely Advent by Rachel Billups

Experience the biblical journey leading to Easter through fresh eyes. Rachel Billups guides readers through the unexpected paths and unlikely people God used to bring about redemption. A compelling study that reveals how God works through the ordinary to accomplish the extraordinary.

In addition to the book, other study components include a Leader Guide and DVD.

Preview the first session on Amplify Media on HERE.

Adam Hamilton

Category Why Did Jesus Have to Die? by

by William H. Willimon

Rachel Billups

Theological Focus

Structure & Approach

Atonement theory and crucifixion meaning; challenges transactional views; explores the cross as transformative rather than explainable

Thematic exploration of crucifixion metaphors (ransom, sacrifice, reconciliation, victory); theological analysis

Table fellowship and mealtime parables as windows into the Last Supper; hospitality and kingdom values

Key Themes Transformation vs. transaction, living Word, multiple metaphors, mystery

Six-week journey following Jesus to Jerusalem through meal-based parables; narrative exploration

Best For Theological depth and complexity; questioning traditional explanations; pastoral/worship integration

Witness-centered Easter story; resurrection as ongoing invitation; God's work in the margins

Character-driven journey through Easter story focusing on overlooked witnesses and moments

Mercy, invitation, radical hospitality, kingdom surprises, preparation for Holy Week

Devotion, opposition, freedom, courage, companionship, alliances, unexpected moments

Storytelling approach; connecting parables to Holy Week; traditional journey structure

Fresh perspectives; character identification; seeing the unexpected

Practical Application

How the cross transforms who we are and how we live

Study Components Book, Leader Guide, DVD, Sermon and Worship Download

Key Insight The cross may not be a transaction to explain but a word to transform

Connecting ancient table stories to contemporary Christian life through discussion questions

Book, Leader Guide, DVD

Table stories illuminate the deeper meaning of Jesus' final meal and sacrifice

Heightened awareness of God's unexpected work in everyday life and margins

Book, Leader Guide, DVD

Resurrection is not just a past event but an ongoing invitation

THE MEANING OF THE CRUCIFIXION

Hamilton breathes life and curiosity into a question that is both common and central to the faith of Christians. Through the heart language of hymns and voices of history and tradition, he unwraps the living truth of the cross that stands as our saving grace.

–Laura Merrill, Bishop, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Oklahoma Indian Missionary Conferences of The United Methodist Church

In the rich tradition of preacher-theologian, Hamilton does not shy away from the complexity of atonement theology. He brings the atonement back into the middle of human life so that the earthly Jesus connects with people in their present reality. He reminds us that the cross is not a symbol of condemnation, but of grace. In a time when many wrestle with images of a wrathful God or punitive justice, Hamilton re-centers the conversation on the self-giving love of Christ, “while we were yet sinners Christ died for us” (Romans 5:8). I commend Why Did Jesus Have to Die? to all who seek to understand the mystery of the cross and the hope it offers to a broken world.

–Robin Dease, Bishop, North and South Georgia Conferences of The United Methodist Church

If you have ever felt that the meaning and power of Jesus’ death on the cross was something you almost understood, Adam Hamilton is here to help. This is one of Adam’s best books. He offers a logical understanding of Jesus’ death on the cross that is clear, biblical, and insightful. This book helps us understand God’s love in a fresh way.

–Tom Berlin, Bishop, Florida Conference of The United Methodist Church

Who knew that atonement theory discussions could be both stimulating and personally challenging? Many today are asking, Why did Jesus have to die? Do typical understandings of Jesus’ death shortchange God into someone who demands recompense? In a rare feat Pastor Adam Hamilton jettisons corrupted approaches to the death of Jesus, explains the theories, shows the importance of a multiphasic approach to the death of Jesus, and then explains how each can help us to follow Jesus today. Even more, Hamilton avoids forcing readers to choose their favorite atonement theory. And even more, Hamilton accomplishes the redemption of the moral influence theory in a way that reshapes all atonement theories.

–Scot McKnight, author and theologian

At the heart of the Christian faith is Jesus. Born around 5 BC and crucified around AD 28,1 the New Testament Gospels tell his story. Matthew and Luke begin with stories surrounding his birth. Luke includes a story from when he was twelve. But the focus of the Gospels is on what he said and did during the three years of his public ministry, from his baptism to his crucifixion and resurrection.

Matthew’s Gospel summarized his ministry by saying that he “traveled among all the cities and villages, teaching in their synagogues, announcing the good news of the kingdom and healing every disease and every sickness” (Matthew 9:35). But while the Gospels tell us about Jesus’ words and deeds across the course of his life, they are each driving toward Christ’s arrest, trial, crucifixion, death, and resurrection.

Matthew devotes 30 percent of his Gospel to the final days of Jesus’ life. For Mark, it is 40 percent. In Luke 9:51 we read, “As the time approached for him to be taken up to heaven, Jesus resolutely set out for Jerusalem” (NIV). Sixty-two percent of Luke’s Gospel tells of Jesus’ journey to Jerusalem to be crucified and the events after that. And 47 percent of John’s Gospel is focused on the events of the final week of Jesus’ life.

The Gospel writers saw the Crucifixion (and the subsequent Resurrection) as the climax of God’s work in the life of Christ. You cannot understand Jesus without understanding his crucifixion.

The Crucifixion was at the center of the preaching of the apostles as well. Paul wrote to the church at Corinth, “I decided to know nothing among you except Jesus Christ, and him crucified” (1 Corinthians 2:2 NRSV). To the Galatians he wrote, “May I never boast of anything except the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ” (Galatians 6:14 NRSV). In 1 Peter we read, “He carried in his own body on the cross the sins we committed. . . . By his wounds you were healed” (1 Peter 2:24). The writer of Hebrews notes, “We have been made holy by God’s will through the offering of Jesus Christ’s body once for all” (Hebrews 10:10).

Yet despite the centrality of Christ’s crucifixion to Christian faith, the New Testament is surprisingly vague on precisely how Jesus’ death saves or why, exactly, Jesus had to die. Jesus regularly predicted his own death, and while at times he gave hints as to why he had to die, he never fully explains it. His disciples were consistently confused by Jesus’ words about his impending death. Before his conversion Saul/Paul found the idea of a crucified messiah absurd. The New Testament authors, writing after Christ’s death and resurrection, offer at least ten different metaphors to describe the meaning of his crucifixion, but these only offer glimpses as to how it accomplishes its saving work.

As a pastor, I’ve often heard people express their questions about the logic of the cross. They believe in it, but they don’t

fully understand it. This is why the atonement, the work of Jesus on the cross to reconcile and restore humanity to God, is often described as a mystery. We are moved by his death. We know it was for us. We accept, to the degree that we understand them, its benefits. But in some sense, its logic remains beyond our grasp.

Not only do Christians often fail to understand the logic of the cross, they also often fail to see the expansiveness of Christ’s saving work. Many focus on one dimension of this atoning work, usually forgiveness. Forgiveness is utterly important. But there is far more that Christ’s death is effecting than our forgiveness.

My hope in writing this book is to help readers make sense of the Crucifixion so that we might hear God speak to us through it, and that we might say, with the apostle Paul, “I have been crucified with Christ and I no longer live, but Christ lives in me. And the life that I now live in my body, I live by faith, indeed, by the faithfulness of God’s Son, who loved me and gave himself for me” (Galatians 2:20).

Adam Hamilton

Before we delve into the meaning of the Crucifixion, it seems important to consider what led up to it—the reasons, from a strictly historical standpoint, that Jesus was sentenced and put to death, as well as what actually happened in his crucifixion.

Beginning as early as Mark chapter 2, opposition to Jesus began to develop. When Jesus forgave a man’s sins, Mark records, “Some legal experts were sitting there, muttering among themselves, ‘Why does he speak this way? He’s insulting God. Only the one God can forgive sins’” (Mark 2:6-7). Shortly after this, Mark notes that the Pharisees questioned why Jesus ate with sinners and tax collectors (Mark 2:16). A few verses later, Mark records that the religious leaders were troubled that Jesus did not require his disciples to fast (Mark 2:18). Then Jesus plucked grain to eat on the Sabbath, and they accused him of violating the Sabbath laws (Mark 2:24). And just a few verses later, as Jesus healed a man on the Sabbath, Mark notes, “At

that, the Pharisees got together with the supporters of Herod to plan how to destroy Jesus” (Mark 3:6).

From the perspective of those religious leaders who called for his crucifixion, Jesus was put to death because he contradicted their interpretations of Scripture, he didn’t follow their rules, they were jealous of his popularity, and he challenged their authority. Some claimed he had demons, or was empowered by demons (John 10:20; Matthew 9:34). In addition, Jesus’ fate was sealed as he came to Jerusalem for Passover and drove out the merchants and moneychangers from the Temple courts, then called out the religious leaders for their hypocrisy. Ultimately, the religious leaders found him guilty of blasphemy for claiming to be the Messiah and took him to the Roman governor, demanding his crucifixion.

From the perspective of the Romans, who sentenced him to death, Jesus was guilty of leading an insurrection, though he was unlike any rebel they had seen before. He entered Jerusalem six days before his crucifixion to throngs waving branches in the air and shouting, “Deliver us now!” Judea was a powder keg with zealots and their supporters who hoped to overthrow Roman rule. Anyone claiming to be the long-awaited Messiah would be seen as a challenge to the emperor’s authority; the authority of his puppet king, Herod Antipas in the Galilee; and his governor in Judea, Pontius Pilate.

When persons were crucified, their crimes were listed on a sign above their heads. All four Gospels note that the sign above Jesus’ head read, “The king of the Jews,” though John expands the sign to read, “Jesus the Nazarene, the king of the Jews” (John 19:19). John also tells us that the Jewish leaders

objected to this sign. They wanted it to read, “This man said, ‘I am the king of the Jews’” (John 19:21) but Pilate refused to change the charge.

Neither the religious leaders nor the Roman governing apparatus believed they were putting Jesus to death for any saving purpose. Both were ridding themselves of a problem. But Jesus and all who followed him saw God using this miscarriage of justice for the purposes we will explore throughout the pages of this book. In God’s way of bringing good from the evil humans sometimes commit, I’m reminded of the words of the patriarch Joseph to his brothers after they had sold him into slavery, “You planned something bad for me, but God produced something good from it, in order to save the lives of many people” (Genesis 50:20).

Before leaving our introduction to Christ’s death, a brief summary of what happened at Christ’s crucifixion may also be helpful. I’ll draw upon the chronology found in Matthew, Mark, and Luke’s Gospels; John’s chronology differs in some details.

It was a Thursday evening, the start of the Jewish Passover, when Jesus sat with his disciples for the traditional meal celebrating the night when God rescued Israel from slavery in Egypt. The Passover is typically joyful, but on this occasion Jesus’ mood was somber. At the meal Jesus predicted that one of his disciples would betray him. He then took a piece of the unleavened bread and said, “This is my body.” He then took one of the four cups1 of wine used in the Passover and said, “This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many” (Mark 14:22-24).

During the meal, Judas Iscariot left to meet with the Temple guard, having already agreed to betray Jesus into their hands for thirty pieces of silver. Following the meal, Jesus led his disciples to a place on the Mount of Olives called Gethsemane (the word means “oil press”). There, “He began to feel despair and was anxious” (Mark 14:33). He asked his disciples to wait and pray while he went a bit farther ahead to pray. Then he “threw himself on the ground and prayed that, if it were possible, the hour might pass from him. He said, ‘Abba, Father, for you all things are possible; remove this cup from me; yet, not what I want, but what you want’” (Mark 14:35-36 NRSV).

A few moments later Judas Iscariot led a mob sent from the religious leaders to arrest him. In the darkness, Judas identified Jesus with a kiss, whereupon Jesus was seized. His disciples fled as Jesus was bound and led away to the home of the high priest, where members of the Jewish ruling council had gathered. Trying an accused by night was highly irregular, but this was done to avoid the crowds of Jesus’ followers.

Witnesses were brought to testify to anything Jesus might have said or done that was considered criminal. When none could agree, the high priest finally asked Jesus, “Are you the Christ?” to which Jesus replied, “I am.” And with that, the high priest and religious leaders agreed, “He deserves to die.”

At sunrise he was taken to the Roman governor, Pontius Pilate. Pilate heard the accusations against Jesus, and asked him, “Are you the king of the Jews?” Jesus gave a cryptic response, saying “That’s what you say” (Matthew 27:11). Ultimately, Pilate asked the crowd, “What should I do with the one you call king of the Jews?” They shouted back, “Crucify him!” I

suspect many of these were merchants who had been deprived of income when Jesus cast them out of the Temple. Others were lay supporters of the Jewish religious leadership. “Wishing to satisfy the crowd,” Pilate sent Jesus off to be beaten, then crucified.2

He was led to a place called Golgotha (Calvaria in Latin)— it means “the place of the skull.” There, about 9 a.m., they stripped him naked, stretched him out upon the cross and affixed him to it with spikes. The cross was hoisted in the air. Two violent outlaws3 were crucified with him, one on his right, the other on his left. For the next six hours, Jesus would hang, slowly dying.

Crucifixion is one of the most painful forms of death ever invented. It was intended to prolong the victim’s suffering, thus serving as a deterrent for others who might be tempted to commit crimes punished in this way, violent crimes and rebellion among others. Multiple theories have been suggested for the physiological cause of death by crucifixion, and these vary from dehydration and blood loss to asphyxiation, respiratory failure, and many more. We don’t know conclusively the precise cause of death by crucifixion, only that it was commonly used by the Romans of Jesus’ day as a means of torturing people to death.4

By 3 p.m., Jesus breathed his last. Shortly after, when Pilate found out that Jesus had died, he allowed two men, Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, to remove Jesus from the cross in order to bury him before the Sabbath began at sunset. They hastily prepared his body for burial, likely with women assisting, and they placed him into the tomb Joseph had constructed for

his own burial. They rolled a large stone in front of the tomb. And that, the Romans, Jewish leadership, and Jesus’ own followers believed, was the end of his story. But that was most definitely not the end of Jesus’ story.

Thirty-six hours after his burial,5 the stone in front of the tomb was forced aside, Jesus was resurrected, and he stepped out and soon appeared to Mary Magdalene and then to the other disciples. He would appear to them on multiple occasions over the next forty days. It was only in the aftermath of his resurrection that his followers began to understand that Jesus’ death had saving significance—that it was intended by God to speak, to heal, to offer forgiveness, to bring reconciliation, to initiate a new covenant, to be a sign of divine love, and so much more.

In the following pages, we’ll seek to understand what the disciples, and generations of Christians after them, came to understand about why Jesus died and the saving significance of his death. As we do, we’ll explore ideas that came to be known as “theories of the atonement.” I’ve used the metaphor of a puzzle to think about the meaning of the death of Jesus, with each atonement theory being like a piece of the puzzle. All of the puzzle pieces, together, help us see the meaning of the Crucifixion.

As I’ll argue throughout the book, I believe Jesus’ death on the cross should first be understood as God’s Word to humanity. Jesus incarnates God’s Word, revealing God’s heart and character, God’s action on our behalf to reconcile and heal us, God’s word about the human condition, and God’s word concerning God’s will for our lives. Our task is to hear this

word, to receive it, and to allow it to have its intended effect on our lives, and through us, on the world.

Some might suggest that this approach is a merely subjective approach to atonement and crucifixion. I disagree. That claim fails to understand the power of God’s word and how God works in our world. Throughout Scripture God acts by speaking. Creation occurs by God’s word: “God said, ‘Let there be light.’ And so light appeared. God saw how good the light was” (Genesis 1:3-4). God speaks and a stuttering sheepherder named Moses becomes the great deliverer. God speaks and the childless Abraham and Sarah conceive a child. God speaks through prophets and kingdoms rise and fall. Paul, as well as the writer of Hebrews, describes God’s word as a sword. But most importantly for our purposes, in his epic prologue, John describes Jesus himself as God’s Word.

In the light of this, we can see (or hear) that the various New Testament metaphors used to describe Christ’s death, and the resulting theories of the atonement, are not mechanisms for our salvation, but God’s Word speaking powerfully through the suffering, death, and resurrection of Jesus.

With this in mind, let’s begin.

In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God . . .

The Word became flesh and made his home among us.

(John 1:1, 14)

In the same way that everyone dies in Adam, so also everyone will be given life in Christ. . . .

The first human, Adam, became a living person, and the last Adam became a spirit that gives life.

(1 Corinthians 15:22, 45)

I have often been asked, not only by skeptics but also by devout Christians, “Why did Jesus have to die?” Sometimes these are people new to the faith. But more often, they are devout Christians who have spent a great deal of time thinking about this question. Some ask, “Did God need for Jesus to suffer and die in order to forgive our sins?” Or they may ask, “How exactly does the death of Jesus so long ago absolve me of my sins today?” Sometimes they simply say, “I’m embarrassed to admit it, but the atonement just makes no sense to me.” As one man told me, “I believe Jesus died for me. I feel bad that he did. I love him for it. I just don’t fully understand it.” Or as one woman told me, “The atonement is one of those ideas that you can’t think about too long or it just gets confusing!”

If you have ever felt that way, you are in good company. Lutheran theologian Robert Jenson once wrote, “The history of theology has been rich in theories of atonement, and explanations of this reconciliation [of God and humanity that Jesus made possible], none of which has been fully persuasive or has in fact persuaded the church as a whole.”1 Evangelical theologians James K. Beilby and Paul R. Eddy note, “Particularly among evangelical theologians today, the question of how best to conceive of the atonement remains an important and contested issue.”2

In his book Mere Christianity, C. S. Lewis said it this way, The central Christian belief is that Christ’s death has somehow put us right with God and given us a

fresh start. Theories as to how it did this are another matter. A good many different theories have been held as to how it works; what all Christians are agreed on is that it does work.3

The Gospels note that Jesus repeatedly told his disciples that he would be put to death. He described the significance of his impending death in several ways, but he never explained precisely how his death would bring forgiveness, ransom the world from sin, glorify his Father, or draw all people to him. In fact, when he told his disciples that he had to suffer and die at the hands of the religious leaders, they at first did not believe him, and when he persisted, they did not understand it.

In Mark 8, Jesus, just after he affirmed that he was, in fact, the king the Jewish people had been waiting for, said to his disciples, “’The Human One [Son of Man] must suffer many things and be rejected by the elders, chief priests, and the legal experts, and be killed, and then, after three days, rise from the dead.’ He said this plainly” (Mark 8:31-32). But consider Peter’s response to Jesus’ prediction: “Peter took hold of Jesus and, scolding him, began to correct him.” This did not go very well for Peter, as Jesus famously responded, “Get behind me, Satan. You are not thinking God’s thoughts but human thoughts” (Mark 8:32b-33).

In Mark 9:30-31, Jesus again predicted his death to his disciples. And Mark records, “They didn’t understand this kind of talk, and they were afraid to ask him” (Mark 9:32). Again and again, Jesus foretold his death. And again and again, the disciples failed to understand why Jesus had to die to accomplish God’s mission.

The night of his arrest, while he was praying in Gethsemane, Jesus pleaded with God, saying, “Abba, Father, for you all things are possible. Take this cup of suffering away from me. However— not what I want but what you want” (Mark 14:36). At least for a moment, Jesus, too, seemed to wonder if there wasn’t another way forward aside from his impending crucifixion.

On that first Easter, the resurrected Jesus appeared as a stranger to two downcast disciples on the road to Emmaus. They did not believe the report that Jesus had been raised from the dead. Walking in their grief, deeply saddened by Jesus’ death, the “stranger” asked Cleopas and his friend, “‘Wasn’t it necessary for the Christ to suffer these things and then enter into his glory?’ Then he interpreted for them the things written about himself in all the scriptures, starting with Moses and going through all the Prophets” (Luke 24:26-27). After this, as they broke bread together, their eyes were opened and they saw the stranger was Jesus. In reading this story, how I wish Luke had recorded what Jesus said to these disciples about why it was necessary for him to die.

By the way, the idea that the Messiah had to be crucified made no sense to an ambitious young Pharisee named Saul of Tarsus. When he heard Jesus’ followers teaching that their candidate for king had been crucified, he thought it was blasphemous. He responded by pursuing a mission to harass and arrest these followers of Jesus, even giving approval for the stoning death of one of them. Only after an encounter with the risen Christ did he come to believe. After his conversion, he appears to have spent years working out his theology of the Crucifixion4—we’ll explore his thoughts in subsequent chapters.

It has been noted that the creeds of the first five hundred years of the Christian faith, including the Apostles’ Creed, the Nicene Creed, the Athanasian Creed, and the Chalcedonian Creed, tell us that Jesus was “crucified, dead and buried,”5 that “for our sake he was crucified,”6 that “for us and for our salvation” [Jesus] was born,7 and that he “suffered for our salvation,”8 yet none of them tell us how the death of Christ saves us, only that it does. They do not endorse any one “theory of the atonement” while at the same time making it clear that Christ died for us.

As an aside, atonement is an English word with an interesting history. It seems to have been created by William Tyndale (1494–1536), though influenced by John Wycliffe (1324–1384) when he translated the New Testament into English from Greek, and the Old Testament into English from Hebrew and Aramaic—it signified what was necessary to be reconciled or made at one with God, hence at-one-ment.

Today there is a variety of theories of the atonement— theories as to how Christ’s death makes us at one with God. Various Christians tend to emphasize one or the other of ten theories, sometimes more. Most recognize that no one theory is adequate to completely convey the significance of Jesus’ death. Each theory is a puzzle piece that requires other pieces in order to offer a clear picture.

With this as a backdrop, we’re ready to consider the saving significance of Jesus’ crucifixion. In each chapter we’ll consider different answers to the question of how Jesus’ death atones or saves. But I’d like to begin with a foundational theory of the atonement—a way of looking at the Crucifixion that, I believe,

helps resolve the questions raised by the other theories of the atonement and allows each to speak to us today.

I’d like to propose that we start building our understanding of Christ’s atoning work with the majestic Prologue of the Gospel of John, John 1:1-18. John’s Gospel begins,

In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God.

The Word was with God in the beginning. Everything came into being through the Word, and without the Word nothing came into being. What came into being through the Word was life, and the life was the light for all people.

The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness doesn’t extinguish the light. . . .

The Word became flesh and made his home among us.

We have seen his glory, glory like that of a father’s only son, full of grace and truth.

(John 1:1-5, 14)

John speaks of Jesus as “the Word” that became flesh. The Greek word for “Word” here is Logos, which means not simply word, but message, speech, logic, reason, and more. I read John’s Prologue to say that God’s desire to speak to us, to reveal himself and his will for humanity, led to the Incarnation. God’s message, speech, word, logic, reason, and will took on flesh and “made his home among us” in and through Jesus.

Everything that Jesus says and does is God’s Word to humanity, and that Word reaches its climax in Jesus’ death on the cross, with the Resurrection serving as the dénouement— the final resolution or afterword. This Word on the cross is written in the suffering and death of God’s Son.

If we begin by seeing the Crucifixion and the atonement through the lens of John’s prologue, then we can recognize that Jesus’ death is not primarily a transaction, mechanism, or formula—it is not a divine quid pro quo where one thing automatically results in another (Jesus’ death procures our forgiveness, for instance). Instead, the Crucifixion is first and foremost a Word or message from God. This Word has the power to save, to deliver, to rescue, to redeem, to forgive, to heal, to inspire, and to love. It is intended to move us, to change us, to open our eyes and our hearts, to transform us, and to heal us and the world. We might call this the Logos theory of the atonement or simply refer to the Crucifixion as God’s Word.

When we understand this, our question changes from “How does the Crucifixion work?” to “What is God seeking to say to us through the Crucifixion?” Paul notes, “The message of the cross is foolishness to those who are being destroyed. But it is the power of God for those of us who are being saved” (1 Corinthians 1:18, emphasis added). It is the message of the cross—God’s Word to us through the cross—that has the power to save. Each of the various metaphors used in the New Testament, and each of the different popular atonement theories in the church, are ways the disciples, and believers ever since, have heard God speaking through the cross. Each captures a different dimension of this Word. The focus is not understanding a mechanism, but rather

hearing and accepting God’s Word of redemption, forgiveness, and love.

In Scripture the “word of God” was never merely a book, a written document, or a story. In Genesis 1, God spoke and the cosmos was created. In Exodus, God spoke and the Israelites were liberated from captivity. The word of God gave direction to God’s people, and it was the basis of God’s covenant with them. It gave them hope and offered them power. It convicted them and moved them to repentance. We read repeatedly how the “word of God,” or the “word of the Lord,” came to the prophets, seizing them with a message that was like a fire pent up in their bones (Jeremiah 20:9).

In the Gospels, Jesus both preaches the word of God, and as we’ve seen, is the Word of God. In Acts, the word of God is the good news of Jesus that transforms the lives of those who believe it. For Paul the word gives life, is meant to live in us, is the message of Christ he preaches, and is so powerful he likens it to a sword that comes from the Spirit (Ephesians 6:17). This idea is also picked up by the writer of Hebrews: “God’s word is living, active, and sharper than any two-edged sword. It penetrates to the point that it separates the soul from the spirit and the joints from the marrow” (Hebrews 4:12).

Jesus embodies God’s Word. His life is the visible Word of God. You’ve undoubtedly heard that “a picture is worth a thousand words” and that “actions speak louder than words.” I think of some of the most influential photographs in history and how a picture can change hearts and even the course of history.

I think of the well-known photo of Peter, a slave who escaped his master’s estate in March of 1863. He fled to a

Union camp in Baton Rouge. The record of his story is written on the back of the original photograph taken at the Union encampment:

“Ten days from to-day I left the plantation, run away from massa.” “What made you run away, Peter; was your master ugly—did he whip you?” With a

peculiar shrug of his shoulders, and raising his eyes toward the ceiling he shouted, “Lor God Almighty Massa! look here”—and suiting the action to the word, he pulled down the pile of dirty rags that half concealed his back, and which was once a shirt, and exhibited his mutilated sable form to the crowd of officers and others present in the office.9

The wounds on this man’s body spoke louder than any written account could capture. The camp doctor, seeing his back, asked for a photographer to capture Peter’s suffering. It became a portrait of the evils of slavery.

President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1 of 1863. But some in the North felt emancipating slaves was not their concern. Why not simply let the South keep their slaves? This photograph, published and widely disseminated by abolitionists that year, moved people. It led many in the North to a deep resolve that the war must continue until all 3.5 million slaves in the South were free. This image changed the course of a nation and played a key part in liberating millions of people.

That is a powerful example of the impact of a portrait of unjust suffering. In the case of Jesus, we see, or better hear, by Christ’s suffering, death, and resurrection, God’s redemptive, reconciling, healing, transforming Word; we hear God’s judgment on sin, God’s mercy for sinners, God’s love for humanity, and God’s will for our lives.

When we understand the Crucifixion through the lens of John’s Prologue, again, our first question isn’t “How does the Crucifixion work?” but “What is God trying to say to us through it?” Understood this way, we can appreciate why there are a

Lift High the Cross

ten or more different metaphors used in the New Testament to describe the meaning of the cross.

I recently spoke to a friend, Julián Zugazagoitia, the director of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, one of Kansas City’s treasures with more than forty thousand works in its collection. He spoke of how each work of art speaks differently to different people, and that he himself will return to his favorite pieces and see, or hear, something different each time. That’s precisely my experience of the cross.

The early church did not simply hear one word as they contemplated the meaning of the cross. It spoke to them in a multitude of ways. For some, its primary message was human sin and God’s forgiveness. For some, its primary message was evil and God’s defeat of it. For some, it was primarily a portrait of the love of God and our need for it. Some saw in it the sacrifices of the Old Testament. Others saw Christ identifying with our pain. Still others saw in the drama of the cross a reversal of the story of Adam and Eve, and a new defining story for humankind. Some saw the wonder and glory of a God who suffers in order to save his people. These are just a few of the suggestions we find in the New Testament for the Word of God in the crucifixion of Jesus.

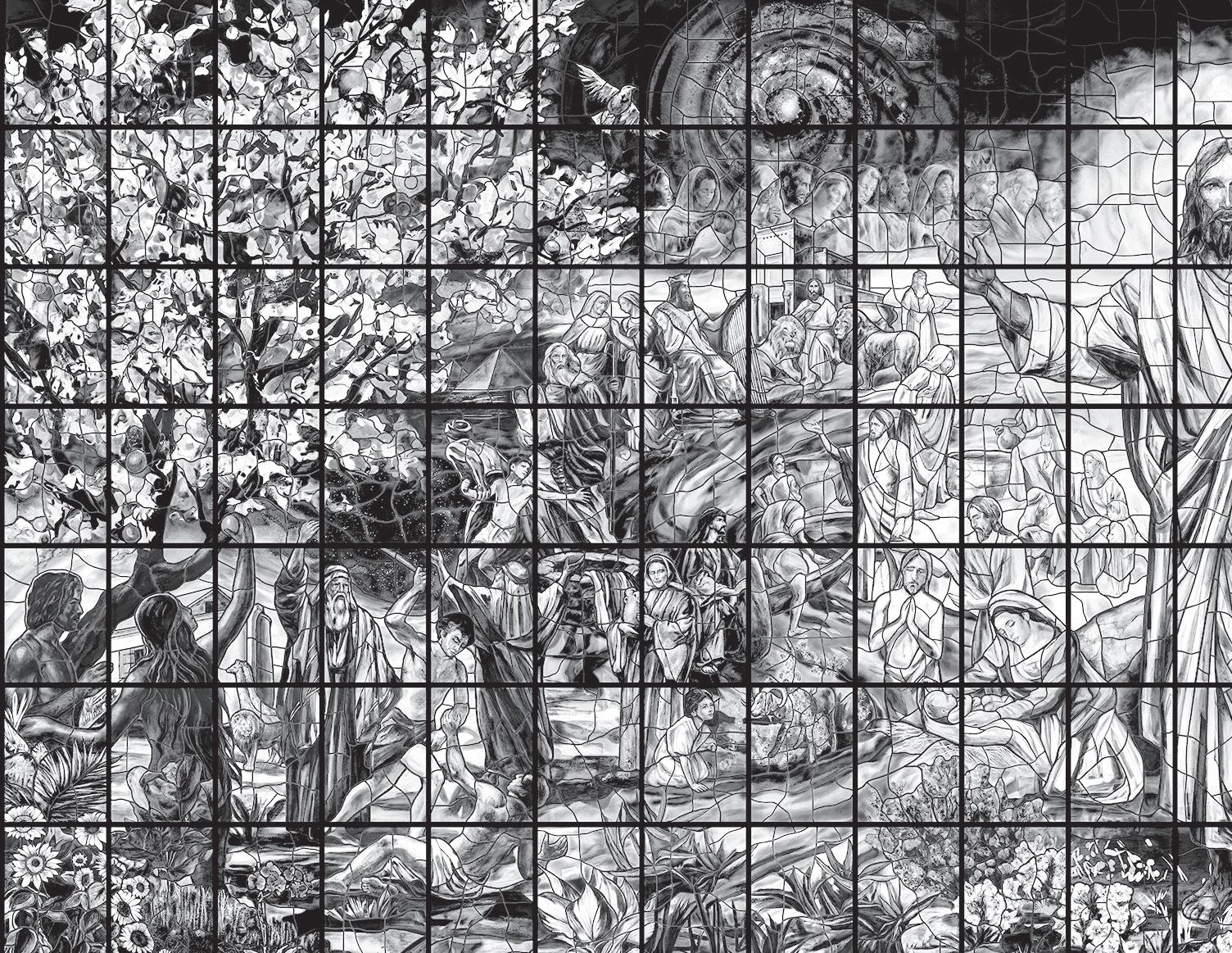

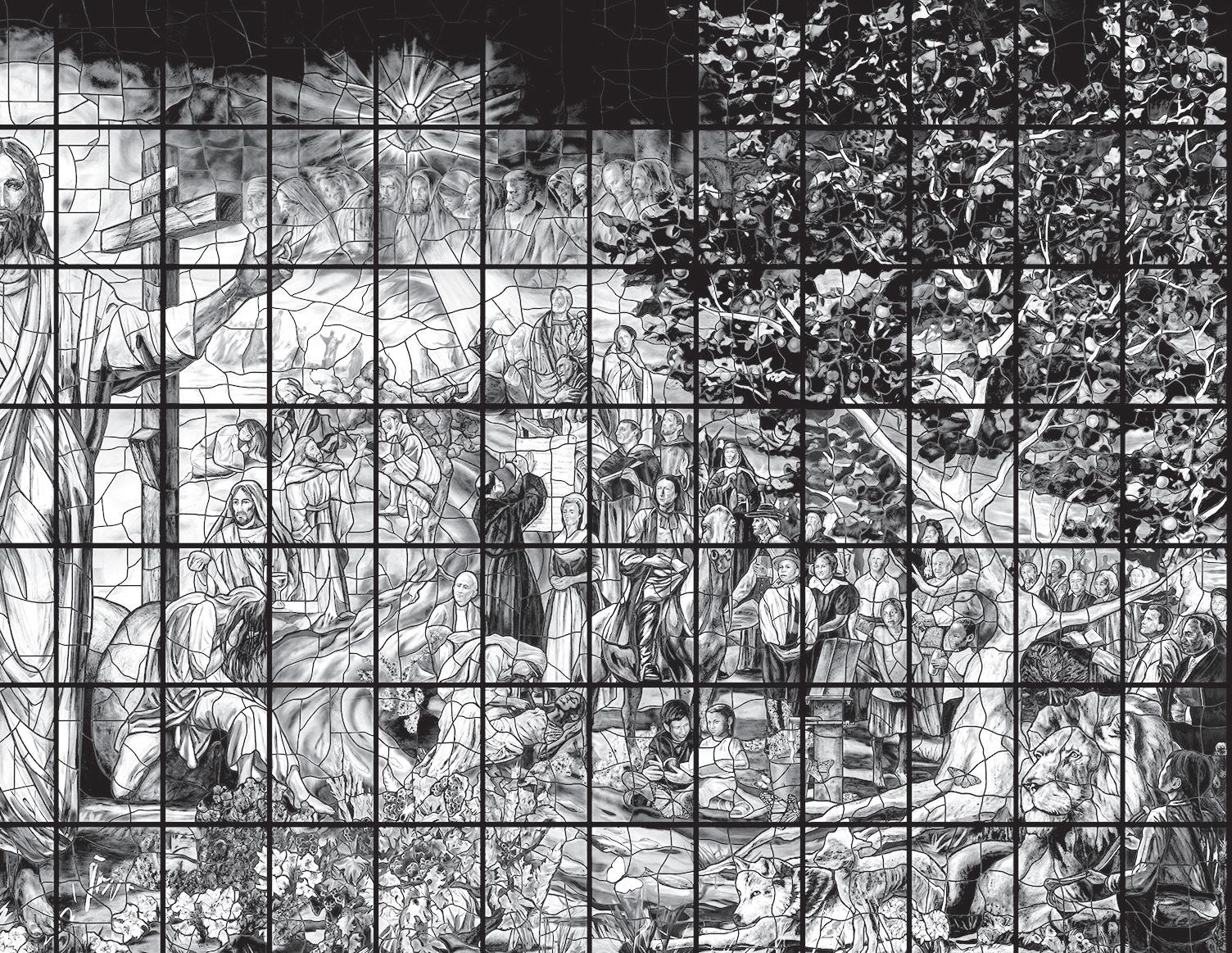

In order to fully understand the cross, you need to see all of these. Some describe this as taking a kaleidoscopic view of the Crucifixion—each turn of the kaleidoscope brings a different, beautiful picture. Others speak of the Crucifixion as a puzzle, as I have suggested, with different pieces, all of which make up the whole. Still others use the metaphor of a tile mosaic, or a stained glass window—each piece is only a part of the whole,

and only when taken together do we begin to fully comprehend the power of the cross of Christ.

This view of the Crucifixion as God’s Word is key to understanding all of the other theories of the atonement we’ll explore in subsequent chapters. In the final paragraphs of this chapter, I’d like to briefly mention one of those theories, what is sometimes called the recapitulation theory of the atonement.

Both the apostle Paul and the Gospel writer John saw in Christ’s crucifixion a return to the garden of Eden. They saw Jesus’ death as a reversal of humanity’s original story. In the Bible’s opening story, God created the first human and placed him in paradise. Here’s how Genesis describes the scene,

The Lord God planted a garden in Eden in the east and put there the human he had formed. In the fertile land, the Lord God grew every beautiful tree with edible fruit, and also he grew the tree of life in the middle of the garden and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. . . . The Lord God took the human and settled him in the garden of Eden to farm it and to take care of it. The Lord God commanded the human, “Eat your fill from all of the garden’s trees; but don’t eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, because on the day you eat from it, you will die!”

(Genesis 2:8-9, 15-17)

By verse 18 in Genesis 2, God sees that “It’s not good that the human is alone. I will make him a helper that is perfect for him.” God then creates the new (and improved!) model of

the man, the woman, to be his companion. Soon they discover a talking, walking snake who comes to tempt them to do the one thing God told them not to do: to eat the fruit that God forbade them to eat. And you know the rest of the story. They soon plucked the fruit and ate it. In their disobedience, their innocence was lost, they were filled with guilt and shame, and they hid from God.

God did not kill them for their disobedience. But he did expel them from paradise, or better, they expelled themselves by their actions. God, in his mercy, provided clothing for them to wear. And he told them that life would, henceforth, be harder for them. Sin and suffering, pain and death had entered the world.

Some read these stories as literal history. Some read them as archetypal stories. Either way, the point of the story was not to tell us about people who lived long, long ago in a place far, far away. The point of the story is to tell us about ourselves. We have all heard the whisper of temptation. We have all turned from God’s will and way. We have known shame and guilt and alienation from God. We have ruined paradise. Adam and Eve are archetypal humans. Their story is humanity’s story—our defining story.

But the apostle Paul recognized that in Jesus, there is a new defining story. He spoke of Jesus in connection to Adam. Listen to Paul’s words to the Romans,

Death ruled from Adam until Moses, even over those who didn’t sin in the same way Adam did—Adam was a type of the one who was coming. But the free gift of Christ isn’t like Adam’s failure. If many people died through what one person did wrong,

God’s grace is multiplied even more for many people with the gift—of the one person Jesus Christ—that comes through grace.

(Romans 5:14-15)

In Jesus, Adam’s story is reversed. Jesus becomes a second Adam, a second archetype or pattern that we may follow. This idea that Jesus came to reverse course for the human race, to give us a new defining story, a new Adam to follow, is called the recapitulation theory of the atonement. In Latin the word for “head” is caput. To decapitate is to remove the head. Recapitulation, and its short form, recap, is usually defined as summarizing or restating something, but it is literally to re-head something. Recapitulation, as an atonement theory, means to restate our story as humans, only now with a new head of the human race, no longer Adam, but Jesus. Again, he offers us a new defining story.

John’s Gospel picks up this theme. He intentionally started his Gospel with the same opening words that we find in Genesis, “In the beginning . . .” The Synoptic Gospels, Matthew, Mark and Luke, pick up this idea as they describe how, before he begins his ministry, Jesus is tempted, just as Adam and Eve were. He’s even tempted by food as they were. Jesus resisted the temptation. Adam and Eve succumbed to it. In Luke 22:42 (see also similar statements in Mark 14:36 and Matthew 26:39), Jesus prays in Gethsemane on the night he would be arrested, “Not my will, but thy will be done.” This is the opposite of how Adam and Eve lived in Eden. If their actions were a prayer, it would have been, “Not thy will, but my will be done.”

In Genesis, Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit in a garden. John intentionally records that “There was a garden in the place where Jesus was crucified” (John 19:41) Jesus is reversing the story of Adam and Eve. He suffers and dies and is buried in the garden. He is resurrected in the garden, and Mary Magdalene, when she first sees him, thinks he’s the gardener. Adam’s sin led to death. Jesus’ suffering ends with his resurrection, conquering death. Adam’s story is reversed by Jesus. Humanity has a new beginning, and we have a new archetype, a new defining story.

In 1 Corinthians 15 we hear Paul describe Jesus as a second Adam: “In the same way that everyone dies in Adam, so also everyone will be given life in Christ. . . . The first human, Adam, became a living person, and the last Adam became a spirit that gives life” (1 Corinthians 15:22, 45). Jesus has suffered death on behalf of Adam’s descendants, bearing the curse from their disobedience, and setting humanity on a new trajectory.

Each of the four Gospels, and the Acts of the Apostles, mention Jesus sending his disciples out to continue the work he began. We are, in the words of the prayer he taught his disciples, not only to pray, but to work to see God’s kingdom come and God’s will be done on earth as it is in heaven. The restoration of Eden began with Jesus, and as his followers, we continue that work.

This is but one of many theories of the atonement. And I’ve shared only my interpretation of this theory. As we’ve noted, the seeds of it are clearly found in the New Testament. It was this understanding of the significance of Jesus’ death that seized the heart of one of the second century’s greatest theologians, Irenaeus of Lyons, who is often credited with championing the

recapitulation theory. It does not represent a mechanism so much as a story, a divine drama in which Jesus is coming to set humanity on a new course, and his death is pivotal in that. Jesus suffers and dies to change our story, and to change the course of human history.

The Bible begins in a garden where Adam and Eve pluck the forbidden fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil and paradise is lost. The Bible ends in Revelation 22 in a garden representing paradise restored. In it is the tree of life, with its leaves for the “healing of the nations” (v. 2). In between these two is Jesus, who resisted temptation, who came as a second Adam, to suffer and die on behalf of humanity, and to call us to a new defining story. He commissions his disciples, and us, to

Stained-glass window from the Church of the Resurrection

Lift High the Cross

continue to live his gospel, and to not merely pray, but also to work to see God’s kingdom come and God’s will to be done, on earth as it is in heaven.

At the Church of the Resurrection, where I serve as senior pastor, we have a large stained glass window—one hundred feet wide by thirty-five feet tall. It captures this idea of recapitulation (and other theories of the atonement). The window is bordered by two trees. On the left is Eden and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil with Adam and Eve plucking the forbidden fruit, essentially living the prayer “Not thy will, but my will be done” On the right is the tree of life from Revelation 22, representing the restored paradise. Between the two is Jesus crucified and resurrected. It is a divine drama in which Christ

suffers and dies for us, then conquers death. He resets our story. And in the window the resurrected Christ stands with his hands pointing each direction, to the tree of the knowledge of good and evil and the tree of life, as if to say, “Which path will you choose?”

I’d ask you that question. In this powerful redeeming and atoning story, which path will you take? Will you follow the first Adam or the second? Will you pray with Adam, “Not thy will, but my will be done”? Or will you pray with Jesus, “Not my will, but thy will be done”?

That leads me to the title of this chapter. I’ve chosen Christian hymns about the Crucifixion as the titles for each chapter in this book. “Lift High the Cross” was written in 1887 and revised several times since. It draws upon the imagery of signs or standards carried into battle behind which the warriors from a nation or tribe marched into war.

But Christ has sought to transform and heal this world—to save us from our “warring madness” by offering us a different way. The sign Christians follow is not a national flag, but a cross. We serve a crucified king. And the weapon in our effort to heal the world is his love. Which is why the hymn’s refrain cries out, “Lift high the cross, the love of Christ proclaim, till all the world adore his sacred name.”

In the crucifixion of Jesus, God has spoken to us deep, profound truths about who he is and who he calls us to be. Through Christ and his crucifixion, the restoration of Eden has begun. We become a part of that restoration, that recapitulation, as we “lift high the cross.”

When the time came, Jesus took his place at the table, and the apostles joined him. He said to them, “I have earnestly desired to eat this Passover with you before I suffer. I tell you, I won’t eat it until it is fulfilled in God’s kingdom.” After taking a cup and giving thanks, he said, “Take this and share it among yourselves. I tell you that from now on I won’t drink from the fruit of the vine until God’s kingdom has come.” After taking the bread and giving thanks, he broke it and gave it to them, saying, “This is my body, which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” In the same way, he took the cup after the meal and said, “This cup is the new covenant by my blood, which is poured out for you.

“But look! My betrayer is with me; his hand is on this table.”

Luke 22:14-21

View a complimentary session of Will Willimon’s The Last Supper

Scan the QR code below or visit https://bit.ly/thelastsupper _session1.

Introduction: Palm Sunday, The Journey to the Table . . . . . . ix

Palm Sunday as enacted parable.

Matthew 21:1-11; Luke 19:28-44

Chapter 1 . Sowing, Seeking, Finding

The Forgiving Master. Luke 7:43

The Sower. Luke 8:5-15

The Grain of Wheat. John 13:14

The Good Samaritan. Luke 10:25-37

Chapter 2 . Open Invitation .

The Great Banquet. Luke 14:16-24

Chapter 3 . Feasting with the Found

The Searching Shepherd. Luke 15:3-7

The Seeking Woman. Luke 15:8-10

The Celebrating Father. Luke 15:11-32

Chapter 4 . Crumbs from the Table

Lazarus and the Rich Man. Luke 16:19-21

Lunch at the House of Zacchaeus. Luke 19:1-10

Chapter 5 . Refusing the Host

The Minas. Luke 19:11-27

The Wicked Tenants. Luke 20:9-19

Chapter 6 . The Host Who Becomes the Meal

The Last Supper. Luke 22:9-21

The Supper at Emmaus. Luke 24:3-25

Notes

1

19

Sure, Jesus’s teaching, healing, and preaching drew crowds in the Galilean outback. But how will Jesus fare in Jerusalem, the capital city?

On Palm Sunday he barges right into town uninvited, unwanted even, parading in public, up front in his intentions to claim the city as his own (Matthew 21:1-11; Luke 19:28-44). We shouldn’t be surprised by his politics. Never did Jesus begin a parable, “A personal relationship with me is like . . .” It was always, “The kingdom of heaven is similar to . . . ” “God’s kingdom,” politics Jesus-style, is the theme of most of his parables.

Conquering your precious heart or solving your personal problems are too small a goal for Jesus’s royal aspirations. As John puts it, “God so loved the world that he gave his only Son . . .” (John 3:16). The world, the whole world, more than your heart or even your zip code. On Palm Sunday Jesus mixes religion with

politics, takes it to the streets, in a public dispute with Caesar over who’s in charge.

At last. “Hosanna! Hail, king! ” (Luke 19:28-40).

But who thinks “king” when you see this itinerant country rabbi astride a borrowed donkey, his motley crew tagging along behind him on Palm Sunday?

Looking back on this scene, Matthew remembered an ironic promise by the prophet Zechariah:

Rejoice greatly, Daughter Zion.

Sing aloud, Daughter Jerusalem. Look, your king will come to you.

He is righteous and victorious.

He is humble and riding on an ass, on a colt, the offspring of a donkey.

(Zechariah 9:9; Matthew 21:4-5)

A king, “victorious” as well as “humble,” a triumphal royal entry on a wobbling, skinny donkey? Parabolic paradox, oxymoron, joke, and riddle, not spoken but enacted on Palm Sunday.

Along the road and at the table Jesus told so many riddles; he now dramatically becomes the greatest conundrum of all. Look! There’s your king, righteous, victorious . . . riding on an ass, a rented one at that.

We want Jesus to get off that ridiculously modest donkey and swagger right up to the palace, plop down on the imperial throne, seize a royal scepter, and begin to issue executive decrees for the liberation of Judea.

Instead, Jesus goes to the temple, heals some sick people, then turns over the tables, causing chaos, provoking indignant uproar among the temple-going righteous, accusing us of having made the holy place “a hideout for crooks.” Just about the meanest thing anybody has ever said about us clergy (Luke 19:46).

“My kingdom is not from here,” Jesus told Pilate at the trial. Here, where all monarchs prop up their power with an army, here, where political strong-arming is the only way to get any good done, where people are admired, not for their love and mercy, but for their ability to coerce, enforce, build walls, make threats, and anybody who sheds an empathetic tear is dismissed as a wimp. Here.

Then there, at week’s end, at the table, in his last meal before execution, all Jesus did was to host a modest meal during which he offered a cup of wine, “This cup is the new covenant by my blood, which is poured out for you” (Luke 22:20).

This, God’s promised salvation?

King on a donkey. An adoring crowd turns into a murderous mob, a preacher who lives and dies what he says, God nailed to a cross, a mighty Savior who shares his last meal with sinful betrayers who are also his best friends?

We wanted him to unfurl a battle flag, storm Jerusalem, and set up a new messianic King of David government. Instead, he gave us a simple supper of bread and wine with a bunch of disappointing, simpleton disciples.

But I get ahead of myself.

As we stumble after him on the road to that last fateful meal, Jesus tells stories, riddles. During the forty-day trek from Ash Wednesday to Maundy Thursday, story after story, Jesus reveals

where he is taking us, unveiling, preparing us for the table in the upper room when he will solve the riddles and show and tell all.

“Who are you?” we wondered. “Where are we headed?” Jesus answered, but indirectly, with pithy little stories that teased, cajoled, upset, made us smile, befuddled, disoriented, or sometimes smacked us up beside the head. “A farmer scattered seed . . . ” “Hear the one about the shepherd who lost a sheep?” “Two people went to the temple to pray . . .”

The gospel is truth we can’t tell ourselves. Nobody is born knowing the good news, nor has anybody ever drifted toward the conviction that a man—tortured to death by a consortium of religious and governmental leaders, hosting his disappointing disciples for a final Maundy Thursday meal, hanging from a cross in agony on Good Friday, forgiving those who nailed him there— is the whole truth about God.

Want to get close to Jesus? You’ll have to sit for story time with him.

Matthew and Mark say Jesus said nothing except in parables (Matthew 13:34; Mark 4:34). Over half of everything Luke quotes from Jesus is in parables or, as we’ll name some of them, riddles.

Humanity’s oldest riddle is from Sumer, six thousand years ago: “What building do you enter blind and exit sighted?”

Answer: “A school.”

These days we prefer truth handed to us on a platter, three obvious points, six knock-down principles for a stress-free life, four takeaways, three irrefutable reasons to get out of bed in the morning, five doctrines you must believe if you are to be a Christian. Biblical fundamentals.

Sorry, that’s not Jesus’s way. If his good news could be encapsulated in easy-to-remember general principles, he would have. Instead, he told stories as a sly stratagem to make his story yours.

“Jesus came into Galilee announcing God’s good news, saying, ‘Now is the time! Here comes God’s kingdom! Change your hearts and lives, and trust this good news!’ ” (Mark 1:14-15).

“Tell us, what’s it like when God’s kingdom comes, God’s will is done on earth as it is in heaven?”

Jesus responds, “Try this. Somebody lies wounded, dying in a ditch in need of saving . . . it can be compared to an invitation to a great feast . . . a woman lost a coin and . . .” Working from everyday experiences of a world we know, Jesus . . . reveals a world we can’t know (i.e., the kingdom of God or, as Matthew describes it, “kingdom of heaven”) without listening to his story.

A warning before you get too far down the road with these riddles: God’s realm is so different from our kingdoms that when Jesus is revealing, sometimes it feels like he’s concealing.

As Jesus told Pontius Pilate on that bleak Friday, “My kingdom isn’t from here” (John 18:36), so it’s bound to sound strange when you first hear of it. Still, you can trust Jesus: he’s telling you this story because he wants to open your eyes so that you can see the good news for yourself.

A parable is a GPS taking you to a new world that’s God’s rather than the fake world in which we bedded down.1

Want to join Jesus at his table? All you’ve got to do is “Listen!” (Matthew 15:10).

Sure, Jesus wants to connect with us, but he refuses to put his truth on the bottom shelf. Good news: Your misunderstanding

and incomprehension won’t stop him from talking. When you respond to some of his more opaque stories with, “I’m sorry, I don’t get it,” what does he say? “Try this: The realm of God could be compared to a father who had two sons, both pains in the neck, though in different ways . . .”

Better than understanding Jesus is to be at table with Jesus. Rather than boasting, “I got it!” it’s better to be able to say, at a parable’s end, “Jesus just got me.”

Maybe you come to church seeking confirmation for what you already know, and then Jesus throws a curveball of a parable and you find yourself dislocated, subverted, pushed on stage as a character in Jesus’s drama of salvation, made citizen of a kingdom not from here. On the basis of nothing but a story.

If you journey with Jesus as he heads toward his last meal you’ll have to put up with his riddles.

What kind of Son of God, Prince of Peace, Savior of the World would end up at supper, the night before his death, with a cluster of losers, promising them a place at the table in his coming kingdom?

This book is your answer.

Will Willimon

Heard the one about the dinner party messed up by Jesus? Simon the Pharisee—a pious, biblically knowledgeable religious leader—invited Jesus to dinner (Luke 7:36). In the Gospels, Pharisees like Simon are depicted as religious experts who can’t stand Jesus; yet they persist in inviting him into their homes for supper! Maybe they hope to trick this rural rabbi into saying something stupid that can be used against him with the Romans. Yet in every case, Jesus turns the tables on his pharisaical critics with parables.

Let’s make that evening at Simon’s a fancy dinner party, sophisticated, expensive, and snobby. A blessing is offered. (Our custom of saying grace before meals comes from the Jews for

whom, once the food is blessed, every meal is sacred.) Scarcely has the Mogen David been poured and the brisket unveiled than a “woman of the city” barges in mid-soiree. She falls all over Jesus, anointing and massaging his feet with sweet ointment, letting her hair down and causing an uproar by bathing Jesus’s “feet with her tears.” (Yes, “letting down her hair” meant the same thing then as now.) Assorted “well, I never” and “outrageous” among the horrified guests.

“When the Pharisee who had invited Jesus saw what was happening, he said to himself [smirking, loud enough for everybody at the table to hear], if this man were a prophet, he would know what kind of woman is touching him. He would know that she is a sinner” (Luke 7:39).

Some prophet, this Jesus, allowing this sinful woman to make such a scene, and at the table too. We aren’t told the “sin” of this woman who “is touching him” (Greek: haupto, “touch,” also “caress,” “fondle”). Luke just says that she’s a “woman of the city,” leaving the rest to your prurient imagination.

Showing not the slightest interest in the shamelessly intruding woman’s alleged sinfulness, Jesus smacks his religiously offended host with a riddle: “Someone owed a loan shark a hundred bucks [back in those days a dollar was worth something] and another guy owed fifty. The predatory lender forgave both debts! Now think hard Mr. Religious-know-it-all, which debtor would be the more grateful?” (Luke 7:42).

“I suppose, I guess you could say, probably, the one who was most forgiven?” (Luke 7:43) replies the embarrassed host, muttering, Whose bright idea was it to invite this pushy preacher to dinner?

Jesus turned to Simon, “Do do you see this woman?” Jesus asks. Of course not. Women were invisible at such occasions, particularly a “woman of the city.” Jesus contrasts her ardor, kissing, anointing, weeping, and affectionate haupto with the dispassionate, dignified, detached, virtue signaling, but now humiliated, Pharisee.

As Jesus puts the screws to Simon, all the guests show sympathy for the plight of their host: “Who is this person that even forgives sins?” (Luke 7:49). Another dinner party ruined by Jesus and his riddles.

Leaving the Pharisee’s stuffy table a shambles, Jesus and his merry band hit the road. Along the way, his stories continue. The word parable comes from the Greek, meaning “throw out,” “toss.” Why pitch these curve-ball riddles toward us? To reveal the “mysteries of God’s kingdom” (Luke 8:9-10).

But God’s realm isn’t that easy to see. Maybe it’s a mystery because the only kingdoms we know are the USA, UAR, UK, Tesla, Walmart, or Costco. Undeterred by our incomprehension, Jesus keeps pitching parables:

He spoke to them in a parable: “A farmer went out to scatter his seed. As he was scattering it, some fell on the path where it was crushed, and the birds in the sky came and ate it. Other seed fell on rock. As it grew, it dried up because it had no moisture. Other seed fell among thorny plants. The thorns choked the young plants. Still other seed landed on good soil. When it grew, it produced one hundred times more grain than was scattered.”

As he said this, he called out, “Everyone who has ears should pay attention.”

(Luke 8:4-8)

Though we’re all ears, we’re grateful when, “His disciples asked him what this parable meant” (Luke 8:9).

Let’s see if we’ve gotten your drift, Jesus: “The seed is God’s word” and the parable describes what becomes of God’s word once it’s broadcast. Couple of questions: Why would any sane sower cast seed on a road? For that matter, who sows seed “on the rock” or “among thorny plants”? Seed so sloppily sown is of course “choked by the concerns, riches, and pleasures of life” (Luke 8:14).

Concern for friends and family, the achievement of a comfortable, secure income, enjoyment of leisure and recreation. Are these not good things? What chokes the seed is not evil, bad, sinful things, but “concerns, riches, and pleasures of life.” Ironic, huh?

Even though I’m no great shakes as a gardener, seems to me that a great deal of good seed is being wasted here.

A farmer carefully removed all rocks and weeds from the soil, turned up the earth six inches deep, spaced neat furrows a foot apart, carefully covering each seed with a half inch of dirt? No! To hell with the asphalt, rocks, and weeds. Just sling that seed!

With such sloppy sowing, are you surprised there is farming failure? Most of this parable reports in detail the disappointing outcome.

Can you guess why the Sower is most preachers’ favorite parable?

In five decades of ministry, nobody has said, “I’m not listening to your sermon because I don’t believe there is a God.” No. The forces that defeated my listeners are not their intellectual reservations about God but rather choking on assorted “concerns, riches, and pleasures of life.”

“What’s your greatest challenge in youth ministry?” I asked a youth pastor. He leaned under his desk and pulled out a soccer ball. “It’s this. Our parents would rather their children learn soccer than Jesus.”

I averaged preaching fifty sermons a year. Yet when asked, my listeners could remember no more than two or three. If “God’s word” is “the seed” that’s broadcast, a lot of seed is being wasted. At least when I’m slinging the seed from my pulpit.

What’s the major reason given for leaving the pastoral ministry? A counselor of pastors replied, “It’s the drip, drip of a gradually draining church. The daily, weekly, relentless meager results. Unremitting failure wears ’em down.”

“She could’a been an attorney. Got a full scholarship to law school. Brilliant. Now she’s stuck at a little country church, attendance, grand total of thirty,” said her disappointed father. “Damn, what a waste.”

Or . . . is it an amazing harvest? The curious thing is that Jesus doesn’t characterize this as a farming disaster. The Sower has a surprise ending. “Still other seed landed on good soil. When it grew, it produced one hundred times more grain than was scattered.” Jesus focuses us on the seed that succeeded rather than the seed that failed to germinate. While most of the scattered seed was wasted, more grain was produced, a hundred times more, than was lost in the reckless sowing. It’s a miracle.

The Sower just loves to sow, slinging seed with abandon, casting good seed into seemingly hopeless contexts, undeterred by the prospect of farming failure, focusing upon the seed that bears fruit rather than the seed that fails.

Therein is our hope.

He had flunked out of college. Then the drugs and the DUI. Two weeks jail time. “So sad,” said everybody at church. “After all his parents did for him, look how low he has sunk.”

But nobody’s story is over until Jesus says it’s over. He will have the last word; loves to make surprise endings. I’ll never forget the Sunday when the young man showed up, looking a bit sheepish, yes, but also bright and hopeful about a new beginning. For the first time in a long time he looked great. New job. Life going well. Volunteered to help in the food pantry next week.

Back in the congregation every Sunday thereafter.

Thank the Lord his story didn’t end as we feared. What happened? He explained it to me one morning over coffee: “I was at this rock concert. Wasn’t thinking about God. Trying hard not to think about anything. And in one of the songs, I heard the word, ‘Why?’ That’s all. Kept ringing in my ears. ‘Why?’

“Well, on the way home that night my girlfriend asked, out of nowhere, ‘Why do you keep hurting yourself when God has given you so much?’ I began to weep. Couldn’t stop. Well, one thing led to another and, long story short, I’m back. Born again and all that.”

Sure, a lot of good seed goes to waste. But Jesus won’t let Almighty Death have the last word. Just one little seed, one word slung from the hand of the Sower, and there’s miraculous harvest.

In the Gospel of John, speaking of his impending death, Jesus told sorrowing disciples a riddle: “I assure you that unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it can only be a single seed. But if it dies, it bears much fruit” (John 12:24). Jesus, the “seed” cast down into death on a cross on Friday, a life wasted. Surprise! Unexpected, abundant harvest by Sunday.

I asked a teacher of elementary school teachers what’s the most important characteristic for educators. She replied, “A good teacher must be in love with sowing the seed but doesn’t need to be around for the harvest.”

I ran right back to my class at Duke Divinity School and told that to my seminarians. Sling that seed with abandon, confident that the harvest is God’s business. (Fun fact: seminary comes from the Latin, “seedbed,” a school where seeds are slung that might bear fruit in future ministry.)

“Sadly, my daughter, who grew up in this church, loved the youth group and all that. But when she went off to college, she left the faith. Says she doesn’t believe all this stuff and she’s not a Christian.”

“Not a Christian, yet,” I corrected. “You tell her to be careful. Take care what she reads, to whom she listens, where she walks. There’s a reckless Sower out there, eagerly slinging seed her way. None of us is safe from the seed taking root in the heart and . . .”

No corner of the earth is dismissed as unfertile ground, and nothing shall defeat so generously scattered secrets determined to go public. Though the word germinates in the hearts of only a few, from those in whom it takes root, it bears abundant harvest. Nine-out-of-ten average Americans may listen, shrug their shoulders and hear nothing. But the Sower, who with such delight wildly, recklessly, graciously slings the seed, marvels at the harvest, otherwise known as your church, your life.

Only a small portion of the whole town will be gathered at your church this coming Sunday. Jesus’s riddle suggests that it’s a wonder that anybody is there, considering all of Satan’s

distractions, the “concerns, riches, and pleasures of life” that make hearing the word so hard for so many.

Jesus’s truth is not to be safely tucked away in our hearts for safekeeping. It’s to be broadcast into all the world. We’re not to judge the potential receptivity of the soil unto which the seed is slung. Working with the Sower, our job is simply to join in Christ’s exuberant slinging of seed, not to be discouraged when his peculiar kingdom truth fails to take root or folks just don’t get Jesus’s jokes. Go ahead, assistant sower, sling that seed.

Only twelve sat at table with Jesus at the Last Supper. Yet look at the harvest.

“Turning to the disciples, he said privately, ‘Happy are the eyes that see what you see. I assure you that many prophets and kings wanted to see what you see and hear what you hear, but they didn’t” (Luke 10:23-24). We, his miraculous harvest, we happy few listening to Jesus’s riddles, and in hearing him, see him more clearly, love him more dearly, so that we can follow more nearly.

Then Luke plays one of Jesus’s greatest hits (Luke 10:25-37).

Mr. Me-Love-Bible-Better-Than-You swaggers up and asks a question meant to stump the Rabbi. (The Common English Bible version calls him a “legal expert” but, due to some negative experiences I’ve had with attorneys, I prefer the traditional “lawyer.” That offends the jurists among you? Sue me.)

“Teacher,” he said, “what must I do to gain eternal life?” (Luke 10:25).

Good one. Even though a recent Pew poll says that most Americans believe in some vague, heavenly future after death, a much smaller proportion believe that this “Teacher” who

taught through riddles is the whole truth about God. Keep the conversation ethereal, spiritual, and fuzzily focused on the distant future.

Jesus, no fan of “legal experts” brushes him off with, “All of us Jews already know the answer: You must love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your being, with all your strength, and with all your mind, and love your neighbor as yourself ” (Luke 10:27; Deuteronomy 6:5; Leviticus 19:18).

“Do this and you will live” (Luke 10:28).

Undeterred, the expert who “wanted to prove that he was right” asked, “Yeah, yeah, but who is this ‘neighbor’ that I’m to love as much as I love me?” Jesus is backed into a corner where he’ll be forced to distinguish between those who are worthy of neighborliness and those who are not. Where to draw the line? The deserving poor from the undeserving? Even Jews with whom we have doctrinal disagreements? Maybe. Roman occupation forces. Never! Those lousy, unfaithful, mixed-race Samaritans? Not a chance. Come on Jesus, show us your list of approved neighbors so we can have a debate over who’s worthy to be my neighbor.

And Jesus answers with (what else?) a story:

A man went down from Jerusalem to Jericho. He encountered thieves, who stripped him naked, beat him up, and left him near death. Now it just so happened that a priest was also going down the same road. When he saw the injured man, he crossed over to the other side of the road and went on his way. Likewise, a Levite came by that spot, saw the injured man, and crossed over to the other side of the road and went on his way.

A Samaritan, who was on a journey, came to where the man was. But when he saw him, he was moved with compassion. The Samaritan went to him and bandaged his wounds, tending them with oil and wine. Then he placed the wounded man on his own donkey, took him to an inn, and took care of him. The next day, he took two full days’ worth of wages and gave them to the innkeeper. He said, “Take care of him, and when I return, I will pay you back for any additional costs.” What do you think? Which one of these three was a neighbor to the man who encountered thieves?

(Luke 10:30-36)

Wait a minute! I asked, “To whom ought I be neighborly?”

Jesus turns the tables on the lawyer, flipping the question into, “Which of these three was a neighbor to the man dying in the ditch?”

“I suppose, I guess, perhaps it’s the . . . Samaritan,” mumbles the lawyer.

“Can’t heeear you,” joshes Jesus.

The neighbor is the lousy, despisedly rich, unfaithful, halfbreed . . . merciful . . . Samaritan. Not, to whom should I be a neighbor but who among the unlikely and despised has been a neighbor to me?

“But when he saw him, he was moved with compassion.” The despised Samaritan was neighbor to the one in need, even though he didn’t even know him and had nothing in common with him.

“Then don’t stand around idly shooting the theological breeze, go and do likewise,” says Jesus.2

(Would Jesus say to religious expert me, “All this writing and reading! Who needs another book on the Last Supper? Go! Do! ”)

This exchange began with the lawyer’s question, “What should I do to gain eternal life?” Jesus’s response suggests that “eternal life” isn’t something we win someday after we die; it is life available here, now, whenever we obey Jesus’s command to “go” and “do.”

In my part of the world, ask folks, “Who’s a Christian?” and they will likely respond, “A Christian is somebody who has accepted Jesus Christ as their personal Savior so that when they die they get to go to heaven.”

Hear any of that in Luke 10?

What impresses me this time through this beloved (shocking?) parable is not just that the Samaritan stopped and cared, heck, I would have done that. It was the way he cared: extravagance and recklessness akin to a careless Sower slinging seed. Most of the verses in the parable are consumed with the Samaritan’s effusive, costly, merciful actions.

The Samaritan took time for the man in the ditch. A risk, since the same brigands who beat the man within an inch of his life could also be waiting to mug the victim’s savior. Ripping up his expensive suit and bandaging the man’s “wounds, tending them with oil and wine,” then placing the wounded man on the leather seats of his Jag, carrying him to an inn for long-term care, then taking two full days’ worth of wages and giving it all to the innkeeper saying, “Take care of him, and when I return, I will pay you back for any additional costs.”

This isn’t a story about pausing to allow a victim to use your cell phone to call the highway patrol; it’s a story about otherwise good people passing by and a bad Samaritan being actively,

systemically, resourcefully, extravagantly merciful to a man in a ditch who was as good as dead.

Know anybody who extravagantly, wastefully, recklessly risked being a victim, mercifully giving away everything he had, even his own life, for a bunch of good-as-dead, down-in-the-ditch strangers?

Even from the cross on which we hung him, refusing his salvation, entrance into his kingdom, he looked down upon us, the dying, saying, “Father, forgive.” Extravagantly merciful, even to his last breath (Luke 23:34). Jesus, good neighbor of all good neighbors.

Don’t soften the shock, the outrage, that the unexpected (maybe even unwanted) hero of the story is a Samaritan. As John’s Gospel explains, “Jews don’t mess with Samaritans,” or words to that effect (see John 4:9). Once, when Jesus’s critics cursed him, they said, “You are a Samaritan and have a demon” (John 8:48).

The good neighbor to the man dying in the ditch is ______?

A religious terrorist? A neo-Nazi? The rich guy who lives next door who posted an offensive yard sign and voted differently from you in the last election? Feel free to fill in the blank with your despised Samaritan.

When Augustine preached this story, he said the Samaritan is Jesus, our unexpected, though true neighbor who reached out in mercy, bandaged our wounds, even made our wounds his own. It’s more than an example story that exhorts us to better human behavior; it’s a story about the saving work of the Christ.

Julian of Norwich interpreted the victim, dying in the ditch from his wounds, then resurrected out of the ditch by divine

mercy, as Christ, the only one who ever found a way out of the grave, the pioneer who goes ahead of us from death to life (Hebrews 12:1-3).

Many people my age say, “I don’t want to be a burden to my family” or “I don’t want to be dependent on the charity of others in my old age.” We thereby show that we have been baptized into the American myth of self-sufficiency and independence. We fear being so in need that we’ll need a neighbor.

Martin Luther King Jr. (who preached more sermons from Jesus’s parables than any other genre of scripture) stressed the ethical imperative in the story. In one sermon King said that the lawyer and the Levite reminded him of most white preachers who are “more cautious than courageous” in their reluctance “to speak up for those in need.” In a couple of sermons King asserted that the Black church had been sent down the dangerous Jericho road to rescue the sick-unto-death white church from its racist sins, to bind up its self-inflicted wounds and restore it to health.

King had the gall to tell an African American congregation that, in spite of all the wounds they had suffered from white supremacy sin, they were called by Jesus to be saviors of those who despised them.

“What must I do to earn my eternal life?” asks the lawyer. I’m a fairly well-fixed person of means. I want to be a good citizen. An afternoon a week tutoring disadvantaged youth? Ten percent off the top for charity? A pint of blood a month to the Red Cross? To whom must I be a neighbor in order to win myself a place in God’s eternal kingdom?

At the story’s ending, Jesus has turned the tables on his questioner. Not, to whom must I be a neighbor? But rather, “Who has recklessly, extravagantly been a neighbor to me?”

Maybe I’m more the good-as-dead, helpless, needy guy down in the ditch than I like to admit, in need of some Samaritan who doesn’t mind getting down and dirty with the likes of me.

“What was your biggest challenge in AA?” I asked a recovering alcoholic.

He replied, “Having to admit that I couldn’t save myself without help from somebody I can’t stand.”

Mother Mary had sung a song of mercy before Jesus’s birth:

He shows mercy to everyone, . . .

He has shown strength with his arm.

He has scattered those with arrogant thoughts and proud inclinations.

He has pulled the powerful down from their thrones and lifted up the lowly.

He has filled the hungry with good things and sent the rich away empty-handed.

He has come to the aid of his servant Israel, remembering his mercy, just as he promised to our ancestors, to Abraham and to Abraham’s descendants forever.

(Luke 1:50-55)

Not much mercifulness out there at the moment. Ours shall not be known as the Age of Mercy. I listen to the news every day, waiting for our current leaders to use the five-letter word Jesus loved; they don’t.

Just heard a podcaster rant that all of America’s problems are due to “the sin of empathy.” Empathetic thinking (which he said particularly afflicts women) leads government decision makers to make excuses for the irresponsibility of others, to rescue people from their own mistakes through empathetic social programs, and coddles people who ought to be punished rather than pitied.

Thank God the man never mentioned the one who, in his last meal, responded to our hunger with “This is my body, my blood, given [mercifully] for you.”

Amid the famine of mercy, what a grand opportunity for Christians to rediscover the oddness of the King on a donkey who preached, “Happy are people who show mercy, because they will receive mercy” (Matthew 5:7).

Scripture has little to say about humanity’s search for God; from start to finish the Bible is a long story of God’s unrelenting, resourceful, determined search for us. We are not able to initiate or to sustain conversation with God; everything about our relationship with God begins and continues with God in Christ slinging seed our way, stooping down to bind up our wounds, with God’s merciful resolve to be for us and for us to be with God.

The Samaritan not only stopped on his journey but also risked reaching out to the one in need in the ditch. That’s good news: your relationship with God is at God’s initiative. In Jesus Christ, God has mercifully taken responsibility for your connection with God.

It’s all well and good that you are reading a book on the Last Supper. I hope that in reading you’ll find yourself drawn closer to Christ.