FOR THE GLOBALLY CONSCIOUS MAN

Olympian Herb Douglas: Still Kicking at 96

Manhood: How do you know when you’ve arrived?

Men share journeys of self-discovery

David

FOR THE GLOBALLY CONSCIOUS MAN

Olympian Herb Douglas: Still Kicking at 96

Manhood: How do you know when you’ve arrived?

Men share journeys of self-discovery

David

A long climb to overnight success

No Upfront Costs To You! Custom built to your specific needs while we service and monitor them 24/7/365. You only pay the monthly service costs. 36 month terms available. Packages start at $39/month.

Efficiently manage your backup and DR storage costs by keeping the most recent or important backups on the local appliance, with the remainder archived to the DigitalJetstream cloud. Local and replication retention policies are managed separately allowing more effective use of your local and offsite appliance storage allocation.

The DR cloud supports an agentless approach to backing up and recovering VMware and Hyper-V environments. Backup physical machines and recover them to existing hypervisors, or recover VMs as physical machines (P2V and V2P recovery support). Set policies to automatically protect newly created VMs to save additional time, money, and reduce risk of downtime due to human error.

15 Minute Failover Guarantee

Our cloud failover service guarantees that you can bring any system back online in our cloud in 15 minutes or less from time of the disaster.

For Windows and Linux machines, Administrators can right-click backups and choose any version of a machine’s backup to be booted and run directly in the DigitalJetstream cloud, with RDP access to help businesses minimize downtime.

Windows and Linux systems that have been backed up onto an on-premise DigitalJetstream appliance (Cloud Failover series) can be run directly on the appliance by simply right-clicking a backup and selecting “boot.” In a matter of minutes, administrators will have VNC access to a live running machine. Once ready, the machine(s) can be powered off, backed up and recovered to production environments, including recovery to an existing vSphere environment.

Appliance backup settings and schedules as well as recoveries can be accessed over the WAN from a central management console or limited to LAN/VPN access for environments requiring greater security.

Welcome to the Winter 2019 Issue of CODE M magazine! We are ecstatic to bring you more of the interesting, substantive, and quality articles that have helped us develop an enthusiastic following in just a short time.

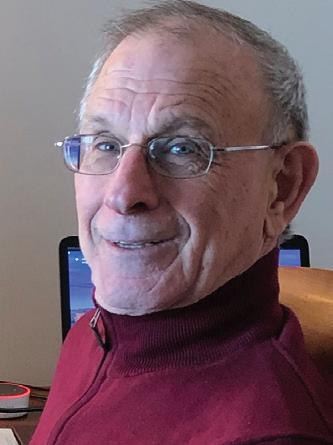

I’m excited to introduce CODE M’s new Editor-in-Chief, Richard T. Andrews. Richard is an experienced writer and editor. His vision and creativity are responsible for this issue’s theme, “Boys to Men.” We think you will be fascinated and enriched to read about the several journeys to the elusive land called Manhood.

Men, as you read these articles, I challenge you to think back to your own journeys, and try to identify the situations, events or time when you realized you crossed the threshold of manhood. What have you shared with your sons, nephews, and mentees that might help them more successfully navigate their path?

To all the heads of single parent households, and I’m specifically speaking to mothers and the surrogates who stand in for them, how are you approaching this subject with the young males whose lives you are helping to shape?

This issue can be a great starting point to get the conversation rolling, as well as a vehicle to reaching out to positive male figures to speak to your sons about their journeys.

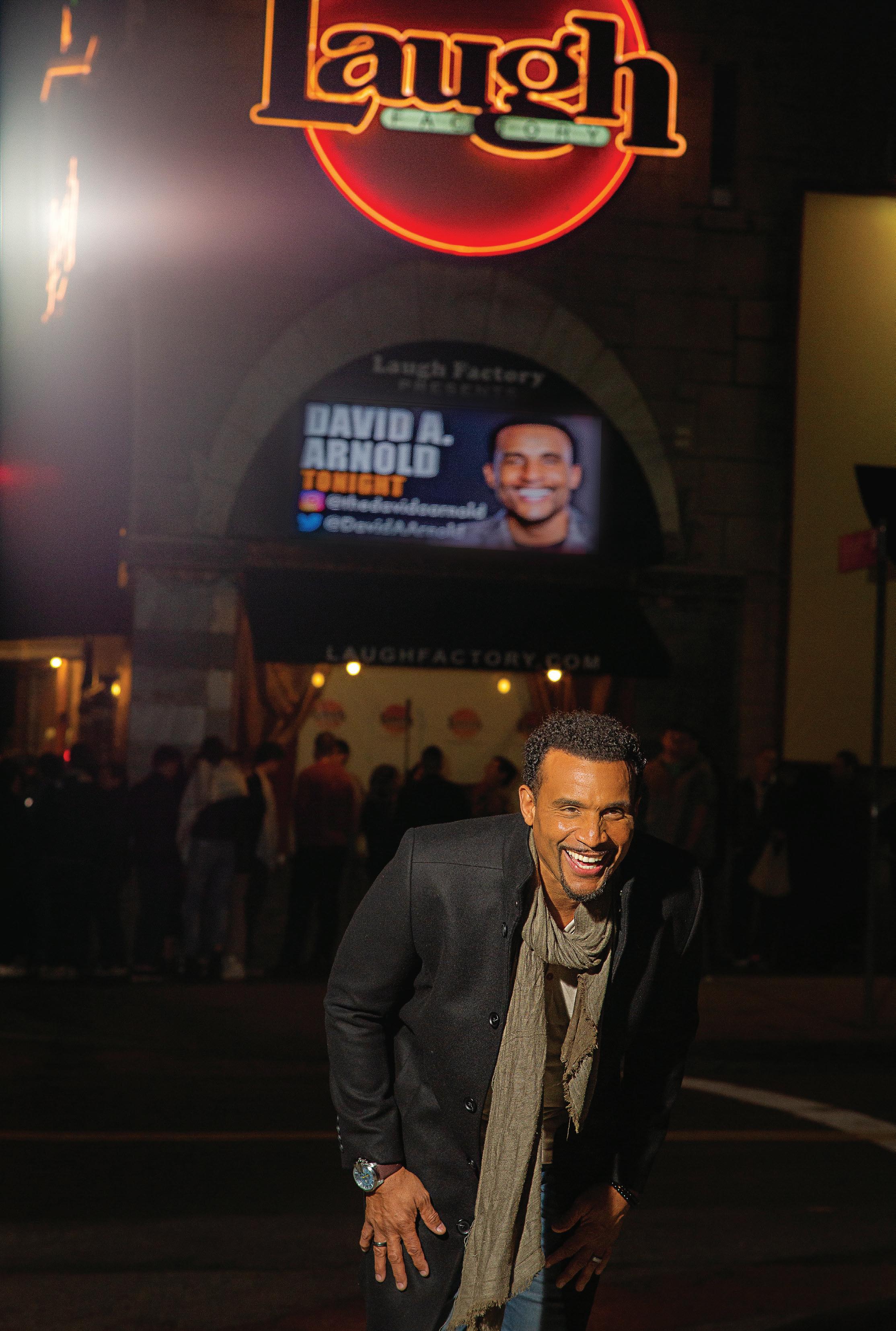

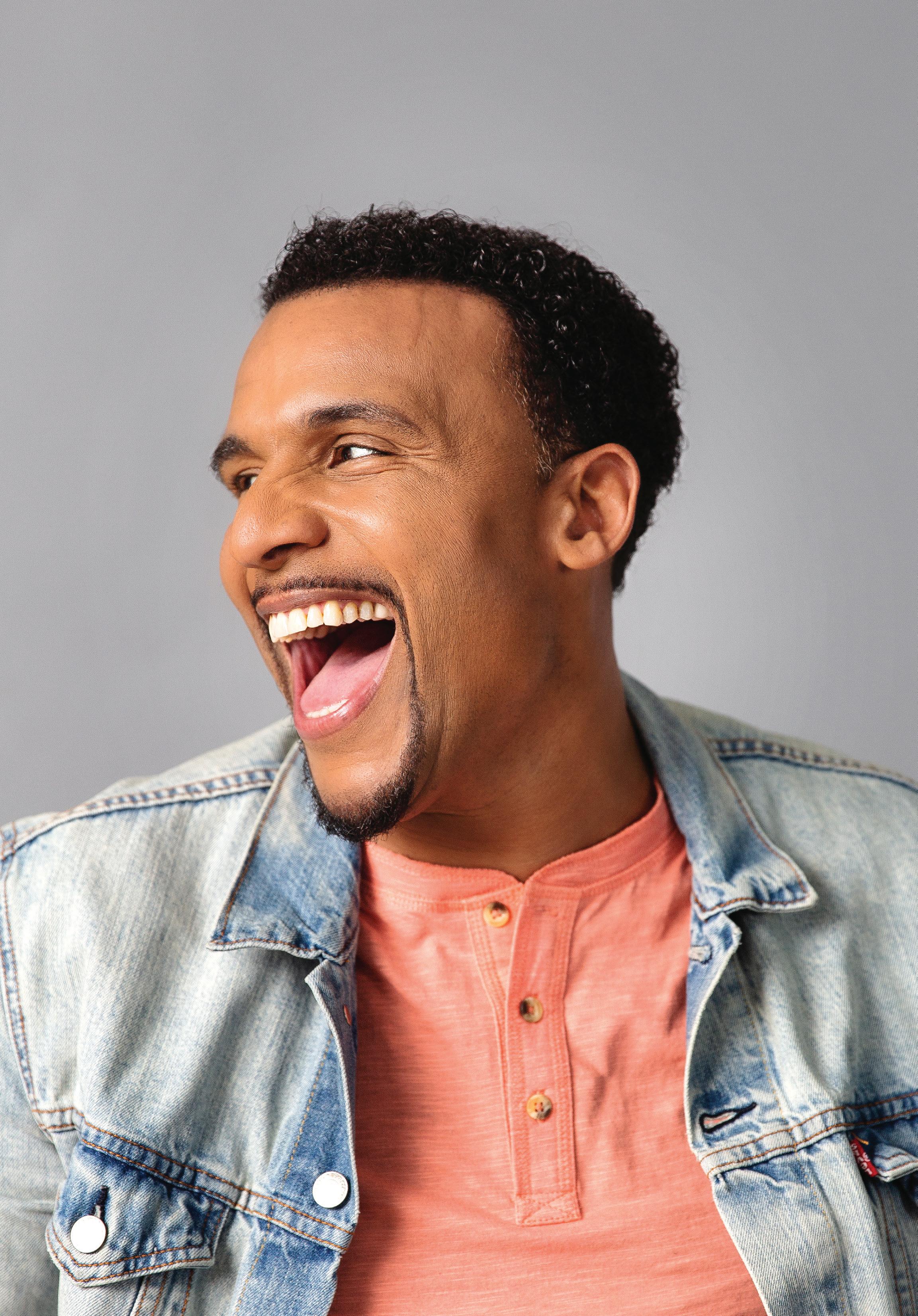

On the cover is a funny, innovative and talented brother, David Arnold, who stayed true to the vision and dreams he scripted for his life. Montrie Rucker Adams interviewed David and did a fantastic job penning his story. Thank you David, for allowing your hometown publisher to tell your story. Our readers will be hearing your name over and over, for you are just beginning to hit your stride.

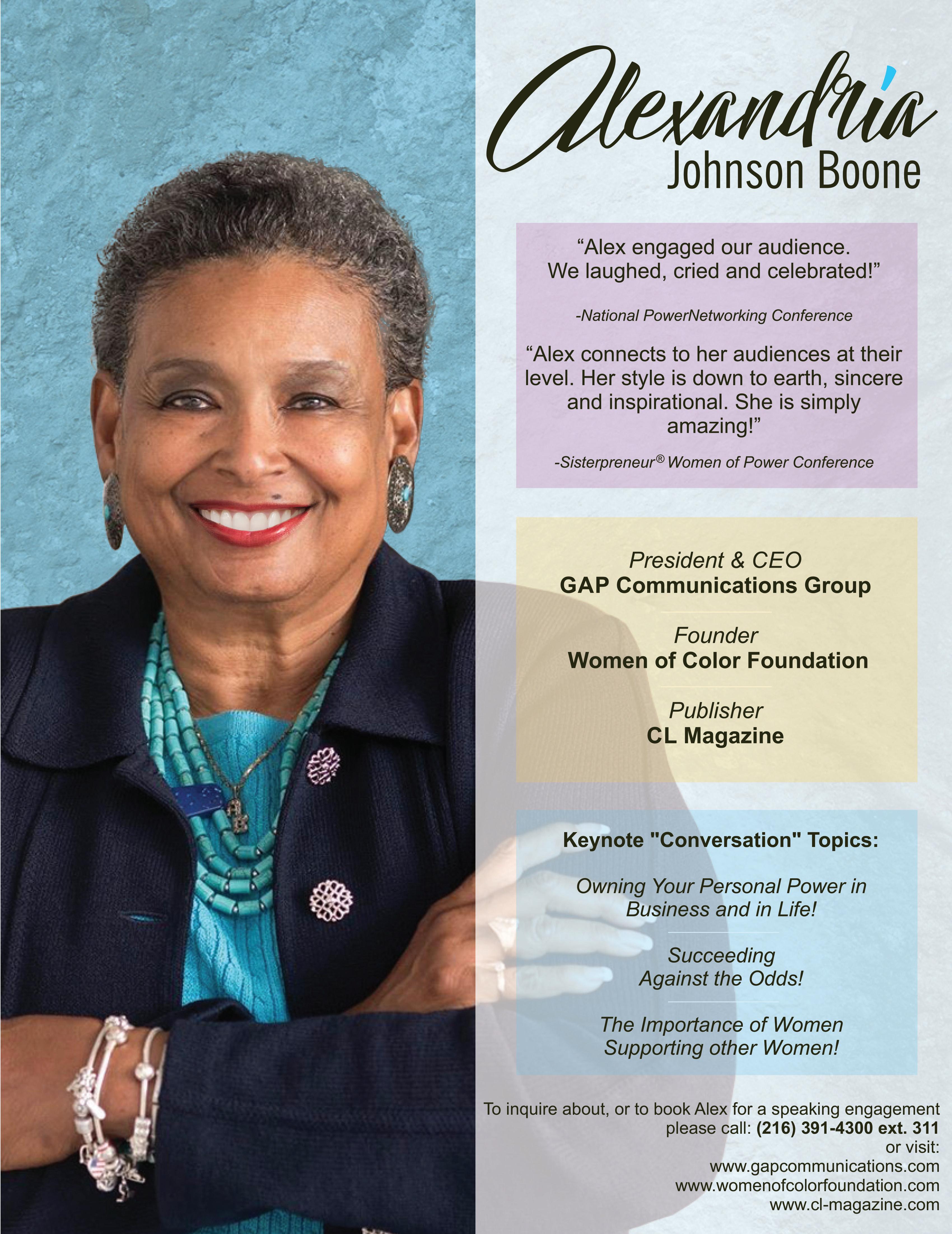

In conclusion, I can’t thank the CODE M family enough: Paula, Lala, Portia, Skip, Jay, Omar, Rae and Jennifer, our graphic designer. As I humbly stand out front, it is only because you have sacrificed your time and energy to have my back, for which you have my enduring thanks. Alex and David, this is your personal shout out. Thanks for your support and encouragement! I know many things are competing for your time, so thank you for choosing to spend some with us. It’s about time and it’s about CODE M magazine.

#LIVEBYTHECODE

CEO / President CODE Media Group, LLC

Publisher

Bilal S. Akram

Contributing Editor

Richard T. Andrews

Senior Adviser

Alexandria Johnson Boone

Special Adviser

David Christel

Media Coordinator

Paula D. Morrison

Asia Affiliate

Cyril White

Europe Affiliate

Sharif Akram

North America Affiliate

David Williams

Account Executives

Bilal S. Akram

Christopher Torrey

David Williams

Graphic Design & Creative

Jennifer Coiley Dial Coy Lee Media LLC

Director of Photography

Sonya Holland

Staff Photographer

Franklin Solomon

Social Media

Amira Akram

Eric Floyd

Jay Floyd

Portia Lopez

Eugene Miller

Advertising ladonna.dicks@codemmagazine.com

Subscribe

How do you know when you’ve become a man?

It is an honor and privilege to have been selected to edit CODE M.

That I’m here seems confirmation of a life lesson encapsulated in a poem by T. S. Eliot, a line from which provided title to a favorite book of mine, The Past Has Another Pattern, a memoir by George W. Ball. The son of an Iowa farmer, Ball eventually became US Undersecretary of State in the Lyndon B. Johnson administration, before he fell out of favor as an early opponent of the Vietnam War.

Ball’s memoir takes its title from these lines from Eliot’s work, The Dry Salvages:

It seems, as one becomes older, That the past has another pattern, and ceases to be a mere sequence —

Or even development; the latter a partial fallacy, Encouraged by superficial notions of evolution,

…

We had the experience but missed the meaning. …

The burning questions of my youth — who was I? Where was my place in this world? What was I to do with the talents I had been given? — all seems wrapped up in a question I posed to my father one day. “Dad,” I asked, in earnest adolescent angst, “how will I know when I’ve become a man?”

The question seemed to take him aback. He was a gregarious introvert of a pastor, a man who likely had formed his notion of manhood in part as a reaction to his preacher father. He called his father “Rev,” a measure, I think, of the emotional and psychological distance between them. “Rev” was married six or seven times, including twice to my grandmother who bore him six children, beginning with his namesake, my father, Richard T. Jr.

Most Mid-Twentieth Century Men, especially those who were fathers, were prisoners of a culture in which they were expected to know all the answers to life’s questions. But my father — who never liked me to refer

to him that way — had no deft response that I could use. He simply said, “When you’ve become a man, no one will have to tell you.”

I’ve never forgotten that exchange, and the question seems a good one to pose in a magazine that speaks to men around the globe. As the world shrinks and civilizations collide, many traditional rituals no longer survive. So we reached out to a number of men of differing faiths, cultures, occupations, and circumstances to ask a variation on our original question: when and how did you know or feel that you had crossed the threshold from boy to man?

The answers provide a fascinating tableau. Some go to faith journeys, while others ruminate around careers and philosophies. Of course, there are references to war, sports, sex, fathers, and children.

We shan’t try to characterize any patterns or themes. Rather, we are excited to have you experience each response for yourself. Most of all, we hope these pieces trigger your own thoughts and recollections about your particular journey, and that you might share those insights as well as of those found in these pages, with the young men you encounter who are on their own treks from boys to men.

There is of course other fine work in this issue. Writer Montrie Rucker Adams goes deep with our cover subject, David Arnold, about his life and work as a professional comedian. And Leah Lewis pens a letter to men that seems to speak for a universe of women.

Savor the contents of this issue. We’ll be especially delighted to hear from those of you wanting to share your own rite of passage journey.

Warmest regards,

Richard T. Andrews

Morgan

Air Conditioning Unit Frederick M. Jones 7/12/1949

Almanac Benjamin Banneker Approx 1791

Automatic Cut-Off Switch Granille T. Woods 1/1/1889

Automatic Fishing Device G. Cook 5/30/1899

Automatic Gear Shift Richard B. Spikes 2/6/1932

Blood Plasma Bag Charles Drew Approx 1945

Biscuit Cutter A.P. Ashbourne 11/30/1875

Bicycle Frame I. R. Johnson 10/10/1899

Baby Buggy W. H. Richardson 6/18/1899

Cellular Car Phone Henry T. Sampson 7/6/1971

Chamber Commode T. Elkin 1/8/1897

Clothes Dryer G. T. Sampson 6/6/1892

Curtain Rod S. C. Scratton 11/30/1889

Curtain Rod Supporter William S. Grant 8/4/1896

Door Knob O. Dorsey 10/10/1878

Door Stop O. Dorsey 10/10/1878

Dust Pan Lawrence P. Ray 8/3/1897

Egg Beater Willie Johnson 2/5/1884

Elevator Alexander Miles 10/11/1867

Electric Lamp/Bulb Lewis Latimer 3/21/1882

Eye Protector P. Johnson 11/2/1880

Fire Escape Ladder J. W. Winters 5/7/1878

Fire Extinguisher T. J. Marshall 10/26/1872

Folding Bed L. C. Bailey 7/18/1889

Folding Chair Brody & Sugar 6/11/1889

Fountain Pen W. B. Purvis 1/7/1890

Furniture Caster D. A. Fisher 3/14/1876

Gas Mask Garrett Morgan 10/13/1914

Golf Tee T. Grant 12/12/1899

Guitar Robert F. Fleming, Jr. 3/3/1886

Hair Brush Lydia D. Newman 11/15/1898

Typewriter Burridge & Marshman 4/7/1885

Corn Harvester Henry Blair

Railway Signal A. B. Blackburn

Paper Bag Making Machine William B. Purvis

Ice Cream Scoop A. L. Cralle 2/2/1897

Insect-Destroyer Gun A. C. Richard 2/28/1899

Ironing Board Sarah Boone 12/30/1887

Key Chain F. J. Loudin 1/9/1894

Lawn Mower J. A. Burr 5/19/1889

Lawn Sprinkler J. W. Smith 5/4/1897

Lemon Squeezer J. Thomas White 12/8/1896

Lock W. A. Martin 7/23/1889

Lantern Michael C. Harvey 8/19/1884

Lubricating Cup Elijah McCoy 11/15/1898

Lunch Pail James Robinson 1887

Mail Box Paul B. Downing 10/27/1939

Mop Thomas B. Stewart 6/11/1883

Motor Frederick M. Jones 6/27/1939

Peanut Butter

George Washington

Carver 1896

Source: New York Public Library African American Desk Reference. New York: John Wiley & Sons. 1999

Pencil Sharpener J. L. Love

Record Player Arm Joseph Hunger

11/23/1897

Dickinson 1/8/1918

Refrigerator J. Standard 7/14/1891

Riding Saddles W. D. Davis 10/6/1896

Rolling Pen John W. Reed 1884

Shampoo Headrest C. O. Bailiff 10/11/1898

Spark Plug Edmond Berger 2/2/1830

Straightening Comb Madam C. J. Walker Approx 1905

Stethoscope Emote Ancient Egypt

Street Sweeper Charles B. Brooks 3/17/1890

Stove T. A. Carrington 7/25/1876

Sugar Making Impr. Norbert Milieu 12/10/1846

Telephone Transmitter Granville T. Woods 12/2/1884

Thermostat Control Frederick M. Jones 2/23/1960

Traffic Light Garrett Morgan 11/20/1923

Tricycle M. A. Cherry 5/8/1888

Ice Cream Augustus Jackson

Striking Clock Benjamin Banneker 1761

Gas Heater &

Clothes Dryer B. F. Jackson

Potato Chip Huram S. Thomas

“A man’s got to have a code, a creed to live by, no matter his job.” –John Wayne “Strength, Courage, Mastery, and Honor are the alpha virtues of men all over the world. They are the fundamental virtues of men because without them, no ‘higher’ virtues can be entertained. You need to be alive to philosophize. You can add to these virtues and you can create rules and moral codes to govern them, but if you remove them from the equation altogether you aren’t just leaving behind the virtues that are specific to men, you are abandoning the virtues that make civilization possible.”

–Jack Donovan

“Nobody can give you freedom. Nobody can give you equality or justice or anything. If you’re a man, you take it.” –Malcolm X

“The way of a superior man is three-fold: virtuous, he is free from anxieties; wise, he is free from perplexities; bold, he is free from fear.” –Confucius

“The True Gentleman is the man whose conduct proceeds from good will and an acute sense of propriety, and whose self-control is equal to all emergencies; who does not make the poor man conscious of his poverty, the obscure man of his obscurity, or any man of his inferiority or deformity; who is himself humbled if necessity compels him to humble another; who does not flatter wealth, cringe before power, or boast of his own possessions or achievements; who speaks with frankness but always with sincerity and sympathy; whose deed follows his word; who thinks of the rights and feelings of others, rather than his own; and who appears well in any company, a man with whom honor is sacred and virtue safe.”

–John Walter Wayland

“Waste no more time arguing what a good man should be. Be one.”

–Marcus Aurelius

“Life is a storm, my young friend. You will bask in the sunlight one moment, be shattered on the rocks the next. What makes you a man is what you do when that storm comes. You must look into that storm and shout as you did in Rome. Do your worst, for I will do mine!” –The Count of Monte Cristo

“If boys don’t learn, men won’t know.” –Douglas Wilson

“Men are like steel. When they lose their temper, they lose their worth.”

–Chuck Norris

“A man may conquer a million men in battle but one who conquers himself is, indeed, the greatest of conquerors.” –Buddha

“When I was a child, I talked like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child. When I became a man, I put the ways of childhood behind me.”

1 Corinthians 13:11 NIV

by BRANSON WRIGHT

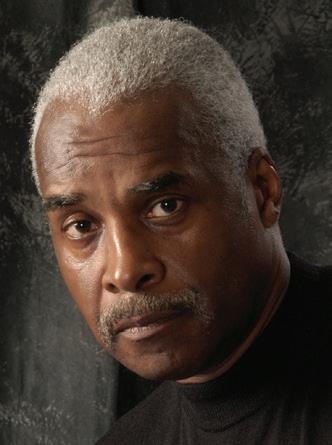

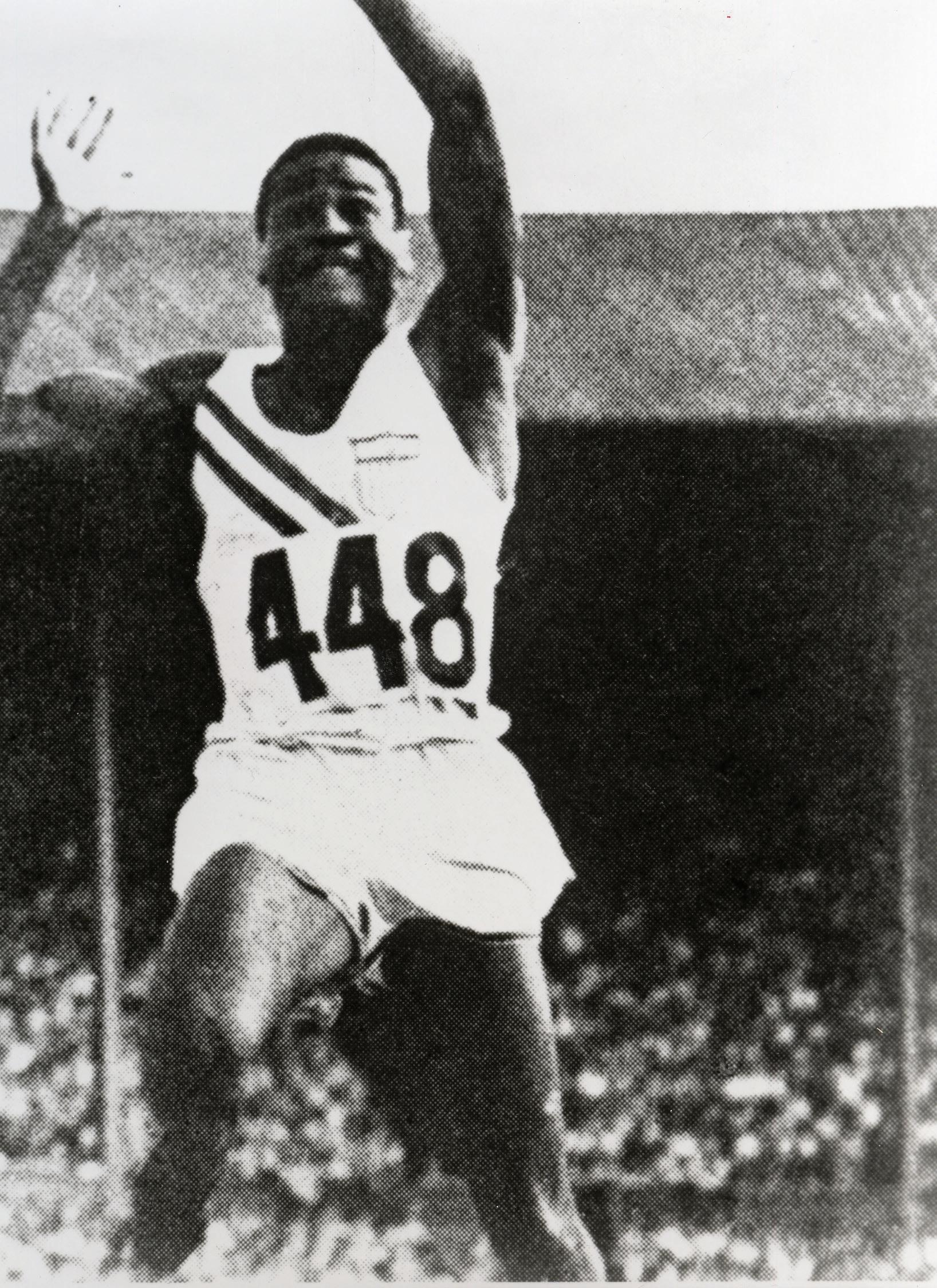

Herbert Douglas, Jr. could hardly contain the rush of emotion as he stood in honor of his latest praise as an inaugural member of the University of Pittsburgh’s Sports Hall of Fame last fall.

Douglas, the oldest living African-American Olympic medalist at 96, was among 17 inductees that included Pro Football Hall of Famers Tony Dorsett, Dan Marino and Olympian Roger Kingdom.

All of Douglas’ international sports accomplish ments and even his trailblazing efforts in sports and business could not outweigh the pleasant memo ries of his hero: Herbert Douglas, Sr.

“Becoming a member of the Pitt Sports Hall of Fame was maybe a notch below the Olympics, but it meant a lot to me from the heart,” Douglas says. “For years as a kid on a street car, I’d roll past my father’s business and roll past Pitt and could never imagine I’d go to school there.”

Douglas not only earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Pitt; he also became a member of the board of trustees. Douglas won a bronze medal in the long jump in the 1948 Olympics, became one of the first African American men to reach the level of vice president of a national company and created a yearly award to honor fellow Olympic great Jesse Owens.

But the foundation of Douglas’ being began in Pittsburgh under the grace of his father, who owned an automobile repair shop. At 41, Douglas Sr. suffered a heart attack and went blind. Despite blindness, he opened and ran three parking garages. He also became the first African American to obtain a seeing-eye dog from Seeing Eye Inc., according to an article in Ebony magazine.

“My dad was able to do a remarkable job despite being sightless,” Douglas says. “My dad taught me how to be positive in everything, and that’s how I was able to succeed in corporate America. He taught me the four principles of life — to analyze, organize, initiate, and follow through.”

Douglas began his sports ascension when he enrolled in Xavier University in Louisiana. In 1942, he helped Xavier become the first historically black college to win at the Penn Relays in Philadelphia.

Douglas eventually withdrew from school and returned to Pittsburgh to assist his father’s business. Douglas enrolled at Pitt in 1945. He won four intercollegiate championships in the long jump and one in the 100yard dash. He also captured three National Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) championships in the long jump.

Douglas also became one of the first African Americans to play football for Pitt, and just the second African American to score a touchdown against Notre Dame.

Douglas’s father taught him the four principles of life: analyze, organize, initiate, and follow through.

When Jesse Owens confided his disappointment over never having won the AAU’s James E. Sullivan Award – given to the nation’s best amateur athlete – Douglas knew he had to correct that.

In 1948, Douglas made the Olympic team and competed in the London Olympic Games, where he clinched a bronze in the long jump at 24 feet, nine inches.

Even with the medal pressed firmly around his neck, Douglas couldn’t cash in on his Olympic success. So he stopped competing and returned to school, earning a master’s degree in education in 1950. Shortly after graduation, Douglas became a sales representative and eventually a special markets manager for Pabst Brewing.

There were few black salespeople during the 1950s and ’60s, but Douglas thrived. Success at Pabst Brewing landed Douglas at Schieffelin and Somerset, a liquor company that would eventually become Moet Hennessy. From 1977 to 1980, he worked as vice president of urban market development, one of the first at that position in the country.

Douglas followed Jackie Robinson, who was the first black vice president of a national company (Chock Full O’Nuts coffee in 1957). Others prior to Douglas include Harvey C. Russell at Pepsi Cola in 1963 and Joe Black in special markets for Greyhound in 1967.

In his role, Douglas helped popularize Hennessy Cognac.

“Many African Americans who were overseas liked how they were treated in Europe, and many were introduced to cognac there and expected to drink it here,” says Douglas, who has worked as an urban marketing consultant since 1987. “I picked up on that and pushed it here in the states.”

Douglas started another push in the early 1970s to honor his hero when the idea of the Jesse Owens International Award and Jesse Owens Global Peace Award was born.

Owens achieved world fame by winning four gold medals (100 meters, 200 meters, long jump and 4×100) at the 1936 Berlin Games. Owens’ achievements defied Germany’s Adolf Hitler, who had hoped to use the games to promote the Nazi Party’s belief in Aryan supremacy.

In 1971, while touring with a promotional documentary, Douglas and Owens were in Indianapolis at the headquarters of the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU). Douglas had a conversation with Owens about the AAU’s James E. Sullivan Award — given to the nation’s best amateur athlete.

Owens commented on how he remained disappointed that he never won the award. “When he told me that, I knew I had to rectify that,” Douglas says.

Since 1981, the Jesse Owens Award is USA Track and Field’s highest accolade, presented annually to the outstanding U.S. male and female track and field performers. The Jesse Owens Global Peace Award has been given to dignitaries such as Nelson Mandela, media mogul Ted Turner and former President George H.W. Bush at last year’s event.

“They all had significant backgrounds in sports and did something indelible for peace significantly,” says Douglas, now the honorary chairman of the organization.

Despite his age, Douglas remains in perpetual motion. He continues to prepare for the 2019 Jesse Owens awards ceremony, mentor current and former athletes and consult those in the business world.

And despite a heart valve “not working as it should,” Douglas keeps moving.

“I’m surprised on how he keeps going,” says close friend and fellow Olympian Harrison Dillard, the oldest living gold medalist at 95. “I often say that’s what keeps him going. He does plenty of stuff to help so many other people and he just keeps going and going. But that’s Herb.”

Cincinnati native Branson Wright is the owner of Be Right Ventures, a multimedia company specializing in documentary filmmaking. He has produced and directed three films including co-producing ESPN’s 30-for-30 project Believeland. Branson is the author of the book Rookie Season and he has been a sports writer for more than 20 years.

IF by Rudyard Kipling

If you can dream—and not make dreams your master; If you can think—and not make thoughts your aim; If you can meet with triumph and disaster And treat those two impostors just the same; If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken Twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools, Or watch the things you gave your life to broken, And stoop and build ‘em up with wornout tools; If you can make one heap of all your winnings And risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss, And lose, and start again at your beginnings And never breathe a word about your loss; If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew To serve your turn long after they are gone, And so hold on when there is nothing in you Except the Will which says to them: “Hold on”; If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue, Or walk with kings—nor lose the common touch; If neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you; If all men count with you, but none too much; If you can fill the unforgiving minute With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run— Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it, And—which is more—you’ll be a Man, my son!

Love, Respect & Sex

Gentlemen:

Thank you. Thank you for being the type of man that women desire and men admire. From your character to your chivalry, from your poise to your confidence, you are the type of man our world and our community need and rely upon. Your contributions do not go unnoticed. We see you.

You have overcome every challenge laid before you to the best of your ability. Perfection is not your standard, but excellence is. What a joy it is to be in your presence and to glean from your wisdom. It is as if you are the embodiment of Rodin’s The Thinker: quiet, contemplative, preparing and fit for the journey.

Know that you are not alone. Our Creator is always present. Consequently, so is the eternal flame of love. A love that is perfect and unconditional. A love that sees you in your essence as perfect and perpetual too.

No innocent “error” is insurmountable. To err is indeed human. We all take what we perceive as missteps. The truth is that as humans we are vulnerable. Additionally, we sometimes offend and hurt people even when that is not our intent. May grace and forgiven shine as guiding lights in our challenging moments when reconciliation may be our motivation.

The depths of your drive and commitment require honor and celebration. I know there are things you still dream of, that you still desire to achieve. Do not give up. Fight the good fight. As long as you have breath, please strive for all that you envision. Whether or not you are victorious ultimately does not matter. Surely you will have some victories. Where you do not, perhaps you can adopt the view of the late and former President of South Africa, Nelson Mandela. One of his philosophies was this: “I never lose. I either win or learn.” Learn. Adapt. Move forward. Onward and upward always. Be encouraged.

As you learn and grow, may your awareness of your spiritual compass be magnified. Let it guide you into all peace and happiness.

Godspeed, Leah

The Reverend Leah C. K. Lewis, J.D., D.Min. (ABD) is a 2005 graduate of Yale Divinity School and holds degrees from Howard University School of Law [1985] and Bowling Green State University. She is the author of Little Lumpy’s Book of Blessings. Learn about her animation project here and here.

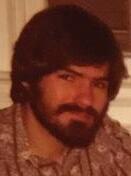

by Montrie Rucker Adams

Laughter. Belly-aching-tears-flowing-bending-over laughter. It’s what most people experience when they encounter David A. Arnold on television, in comedy clubs, and on social media, where his followers — closing in on 500,000 — circulate his videos with such gusto that some of them collect millions of views.

The award-winning director, writer, actor, producer and comedian has performed at the Montreal Just For Laughs Comedy Festival, on Comedy Central’s Laffapalooza, The Tom Joyner Show, Baisden After Dark, Comics Unleashed with Byron Allen, BET’s Comicview, The Monique Late Night Talk Show, HBO’s Entourage and Def Comedy Jam.

Life with Dave, Arnold’s early comedic Internet vlogs (video logs or video blogs), about all things “life” helped propel him into the spotlight to create and produce ten episodes of the same named show, based on his vlogs and comedy routines.

Arnold was on the writing staff of Tyler Perry’s, House of Payne and Meet the Browns where he played a recurring role as “Darnell,” the irresponsible teacher. His stand-up comedy class is the most popular and successful class in the country for aspiring comedians, with more than 300 people on the waiting list.

While Arnold is now deriving great success and popularity from his comedic talents, his entertainment industry rise has had its share of challenges, disappointments, and deep-in-the-valley moments.

Born and raised in Cleveland, Ohio, Arnold’s parents divorced when he was six. His father, Eddie Ar-

nold, is a retired engineer and a professional racecar driver. His stepfather, Bobby Massey, was a founding member of the R&B singing group The O’Jays. His mother, Barbara Arnold-Massey, was the road manager for The O’Jays and Teddy Pendergrass.

“I was always around the entertainment business,” Arnold says. “It was very common to have people like The Whispers and Gladys Knight at our house on a regular basis whenever they were in Cleveland. I grew up around all that. I couldn’t sing, couldn’t play a musical instrument, but had that desire to perform and entertain.”

At 12 he entered the modeling industry, becoming the Midwest’s highest paid child model in his age group. Performing at church, school, and at Cleveland’s Karamu House (the country’s oldest African-American theater), provided him the venues he needed to nurture his creative juices.

“I was always writing,” says Arnold. “I wanted to write for Blue Mountain Arts, the greeting card company. I always had these things in me.” Arnold explains that even though his parents were in the entertainment industry, they didn’t know how to guide his career. He had to find out on his own.

The night Arnold graduated from high school, he went to Los Angeles to scratch his acting itch. With no direction, his stint in LA was short lived. “By this time, the drinker and partier in me was brewing. I didn’t realize then that later on it would become a thing in my life,” he recalls.

Arnold would stay on a job for about six months

before it would completely fall apart. He had skipped college to pursue an acting career, but it wasn’t working. So he decided to enlist in the Navy, serving as a medic and earning a nursing degree during his fouryear term.

Six months before he left the military, Arnold’s friends convinced him to enter a stand-up comedy competition at a local pizza shop. He remembered years before seeing his mother and aunt were reduced to convulsions of laughter he hadn’t thought possible as they watched Eddie Murphy’s Delirious comedy special.

“You see, they were always the disciplinarians. I was more impressed by [Murphy’s] impact on them than what he did on the screen.” Arnold recalls.

So, he tried it. He was 18 when he attempted his first open mic. Nobody laughed. The results were the opposite of his Delirious experience.

Despite that initial disaster, performing stand-up stayed with him. Arnold began watching half-hour comedy specials with comedians like Carlos Mencia, DL Hughley and Eddie Griffin. “As soon as the pizza shop in the neighborhood started doing comedy competitions, all my friends convinced me to enter. I won and kept winning,” said Arnold.

The owner of the shop eventually offered him his own night of comedy since no one else would compete against him. “I started typing out 30 minutes of stand-up. I invited everyone from the military base and all my friends. Everyone came. I thought, ‘I think I can do this.’ That was the beginning.”

What followed was opening for a professional USO Military comedy tour (that his mother just so happened to use her entertainment promotional skills to convince the promoter to let him do), self-promoting videos, and a manager who booked two years’ work opening for comedians like Steve Harvey, Jamie Foxx, and others.

“The work don’t start until it starts getting painful.”

By now, Arnold’s drinking and partying had become a serious issue. “I realized I had to get sober,” he says. On May 5, 1998 after his third attempt and 90 days in rehab, Arnold became sober and today celebrates 20 years of sobriety.

“I now saw what it [sobriety] looked like through clear eyes. I knew who I could be when I was in control of myself. When I was sober, I got things done. I got sober for me. I now had three addresses: The Comedy Store, The Improv and Laugh Factory. I did it. I stayed sober,” he said.

Arnold continued to use his nursing skills during the day since work was not always forthcoming. He stayed a regular at most of the comedy clubs in town. “My name is permanently on the wall at The Comedy Store Hall of Fame,” he notes.

In 2001, Arnold met Julie L. Harkness, only the third African American woman to dance with the New York Radio City Rockettes. “We clicked immediately,” he recalls. “When I met her, she was good for me. She had all the Midwest values that I found important. I’m a Midwest guy in a Hollywood town.” Harkness was from Indiana. They married two years later and not long after, their family grew to include daughters Anna-Grace and Ashlyn.

The entertainment industry is not for the weak. Rejection is a constant as you move up the ladder, and resilience and toughness are essential. You must be able to get back up, even when you are knocked down to your lowest point. Arnold recalls those moments for him.

“We had just bought a house when I got fired from my first television show on TV One, Black Men Revealed. My wife was a full-time mom taking care of the house and the girls. I opened our online banking account. The balance was zero. I had no job. No money. I will never forget the chill that went through my body that day. I had a wife in the kitchen cooking, daughters ages 1 and 3 in the playroom. If there was a time to quit and go back to nursing, it was that day,” he recalls.

Needing some income, Arnold decided to start teaching stand-up classes, which have gone on to become the biggest in the country. Six months later he landed his first professional writing gig for Tyler Perry’s House of Payne and Meet the Browns. This led to other writing jobs, including Real Husbands of Hollywood, starring Kevin Hart, Partners, for Kelsey Grammer and Martin Lawrence for FX, and many more. Arnold now serves as a producer for the Netflix hit show, Fuller House.

Soon after Arnold began to pitch a show he’d written, Divorce Saved My Marriage, with Kevin Hart as executive producer. FX and Hulu bought the show, but eventually dropped it.

Later, Stephen Hill, then BET’s head of programming for BET, spotted Arnold performing on a Tom Joyner cruise. Impressed, Hill asked to see the Divorce Saved My Marriage script.

“Stephen Hill gave me a full season, 10 episodes. After 18 years in the business I am finally about to get my show,” he exclaims. However, one week before production starts, Hill gets fired and is replaced by Connie Orlando. “She completely wipes out everything that was on the slate. She was going to keep our show because it was produced by Hart but it was cut because she felt I was too old, not a household name and therefore not easily marketable to the BET audience.”

Arnold tried to pitch to other networks, but nobody bought it. ABC had Splitting Up Together, which Arnold says is the white version of his show. “It crushed me. I was very much depressed. I was right there, and they took it from me,” he says. “I never thought about quitting, but it was first time I bent over and put my hands on my knees and said, ‘I’m tired.’”

“I’m Cleveland strong. I come from a place where we got grit, we don’t quit,” he says. “I’ve taken that and brought it over here into this business and into this world. That’s why I don’t quit.”

Recalling his reluctance to teach stand-up, Arnold recalls: “Comedians love talking about stand-up. We sit

“When people say, ‘If you pay me, I’ll do it. I’ll be more productive.’ That ain’t how it works at all.”

around and talk about it,” offers Arnold. “I remember being on social media seeing a lot of posts saying, ‘We had a great time talking about comedy with you last night. If you ever decide to teach a stand-up class, I would take it.’ I never wanted to teach a standup class. Because they say, ‘Those who teach, teach because they cannot do.’ My ego would not allow me to do it. I thought, ‘If I teach it, it would look like I gave up and now I’m trying to teach people to do something I couldn’t do. So, I stayed away from it,” he says.

After necessity pushed him to get his ego in check, Arnold has become a sought-after stand-up comedy teacher. “We needed money so I started teaching … but you cannot teach anyone to be funny,” he adds.

Success at Last

Arnold’s decision to take control of his career has paid off. He has written, directed and produced three independent short films. He wanted to show the industry he was more than a comedian and to highlight his acting skills. The films — Because My Stand-Up Is Not Enough, Till Death Do Us Part and The Garage Sale — did very well in film festivals across the country. Arnold initially didn’t know how to write a script. “I got a book, read how to write one and did it,” he adds.

During the time that Arnold finished writing for House of Payne and Meet the Browns, he discovered social media. “I was unemployed again and performing stand-up when I could get them,” he said. “People were vlogging, not really talking about anything. I decided to turn on the camera and do one. The first one was called, Bad Vlogs. I saw the response and started to do more. It explodes and became popular quickly,” he said.

To stand out from the other vloggers, at the end of each Life with Dave vlog, Arnold exclaims, “Credits, bitches!” and “rolls the credits” on toilet paper, listing himself in every “role.” Arnold acknowledges that comedians love the immediate response received during stand-up. He gets the same from his vlog comments. It’s what keeps him going.

It was his Life with Dave vlogs that garnered more work and opportunities. “I started doing them everywhere. One executive producer expected to watch a two-minute video and was still watching and laughing with her family three hours later. Social media was his calling card. It got him his first professional writing job at Tyler Perry Studios.

Arnold turned 50 last year, a good time to look back. “You gotta understand that the work don’t start until it starts getting painful,” answered Arnold when asked what he would tell anyone considering stand-up. “When you realize that what you want to do ain’t easy. Let me tell you when you know that you’re a comedian. When you go onstage and you bomb, which you will…and you have the desire to get back on the stage and do it again.”

“You’ve got to love it that much. I worked many years with no money before I started making money in this business. You gotta want to do it for free. That’s how I know that I am doing something I love doing. You don’t have to give me money for this. I will do this for free. That’s when the money comes to you. When people say, ‘If you pay me, I’ll do it. I’ll be more productive.’ That ain’t how it works at all,” he said.

“You have to find that thing that drives you…that’s more important to you than whatever it is that you’re doing now. It’s that thing that all your friends and boys ain’t gonna be a part of and support you. It ain’t gonna be easy. You gotta know that everybody can’t do it, and you ain’t gonna be able to take all your friends with you on your journey. Everybody can’t come. Some roads are meant to be walked alone. You have to figure that out.”

Montrie Rucker Adams is president and Chief Visibility Officer of Visibility Marketing Inc. in Cleveland, Ohio. She is a Results Coach helping people realize their lifelong dreams and author of Just Do Your Dream! A 7-Step Guide to Help You Do What You Always Wanted.

You have to find that thing that drives you… that’s more important to you than whatever it is that you’re doing now.”

ALL ART reflects its time of creation. One hundred years ago, when the following poem by the JamaicanAmerican writer Claude McKay was first published, manhood likely had a more rigid definition. But its attainment was still a struggle, especially for a black immigrant who aspired to be an artist.

And struggle and resistance are perhaps the defining elements of McKay’s fiercest, most defiant, and best-known poem, “If We Must Die.” Whether the foe be external or internal, struggle in some way has always seemed to be an inevitable part of the journey from boy to man. Of course, as the poem makes clear, achieving manhood status is not the end of struggle, perhaps only a less forgiving stage for dealing with it.

We hope you appreciate this special section. Let us know what you think.

If we must die, let it not be like hogs Hunted and penned in an inglorious spot, While round us bark the mad and hungry dogs, Making their mark at our accursed lot. If we must die, O let us nobly die, So that our precious blood may be not shed In vain; then even the monsters we defy Shall be constrained to honor us though dead! O kinsmen! we must meet the common foe! Though far outnumbered let us show us brave, And for their thousand blows deal one deathblow! What though before us lies the open grave? Like men, we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack, Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

Many men have been commanded at some point in their lives to “Be a man!” “Take it like a man!” and “Man up!” What that meant to me as a boy was to be tough, strong, unflinching when facing danger or pain, never be soft and vulnerable like a girl — don’t be a sissy.

I thought I was supposed to act like the strong and silent types — you know: taciturn cowboys and hardened men of war. Men were supposed to be crude, loud, brash, in charge, brave, ready to defend, and to cavalierly ignore the rules. They made their own way in a demanding and unforgiving world fighting tooth and nail, swearing a blue streak, and charming the ladies. Hmmm, guess I didn’t cut it.

This really begs the question: What exactly is the definition of a “man”?

Some men believe you’re a man only if you’re heterosexual. Others believe you’re a man only if you live a rough and tumble life in the wilderness. For others, only if you’re the top dog running the show. Then there are those who believe it’s only if you’re the last man standing — “winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing.” For some, it’s simply a matter of a formalized ritual.

by David Christel

security number, getting his driver’s license, graduating from college, joining a gang, moving away from home, enlisting in the military. But having done those things, is one really considered a “man”?

I’ve checked off almost all of those rites of passage, yet I have never felt like I passed through some magical portal into manhood — a boy one minute and suddenly a man the next. No one told me I was now a man, no one gave me a “Welcome to Manhood” handbook. The fact is, I’ve never thought about or even called myself a man. I’m just a male of the species homo erectus.

I tried to fit into what is termed a “man’s world.” I played sports, I dated girls, was a Boy Scout, worked on farms and assisted in all manner of livestock births and veterinary emergencies, lived in big cities, traveled, taught, was the best man at a wedding, saved two people’s lives, and delivered two human babies. Still, I don’t feel like I’m a “man.” I just am who I am.

The rite of passage into manhood is celebrated by many cultures and religions. It signals advancement into the world of adulthood. It’s often associated with the onset of puberty and requires of a boy that he leave behind all things childish and now face the responsibilities of being a “man.” For many, that means looking to a future of breadwinning, supporting a family, and involvement with one’s community and nation.

There are also unspoken rites of passage into manhood: the first time a boy has sex, his first job and first paycheck, surviving his first fist fight, hitting a home run, winning a game, killing his first animal for food, the first time he shaves, his first swig of alcohol and/or first smoke, opening his first bank account, attaining a social

It’s a confusing journey for many men, not just for me. Society is constantly pointing out to us what a man is through advertising, books, television, video games, and movies. We have a plethora of models. We’re told men are to be guardians, heroes, leaders, fathers — masters of the universe. Role models include the likes of Washington and Lincoln, Jackie Robinson, Lindbergh, war heroes, athletes, and astronauts.

Others we emulate as “men” include mob bosses, pop icons, corporate saviors, reality TV stars, MMA wrestlers, porn stars, comic book heroes, CEOs, hot shot Wall Streeters, Silicone Valley entrepreneurs, and celebrities in all arenas.

But what about Martin Luther King, Jr., Gandhi, Nelson Mandela, HH The Dalai Lama, Einstein, policemen, firemen, EMT crewmen, doctors, spiritual leaders, art-

ists of all genres, educators, scientists, engineers, statesmen, and men in every other field of endeavor? The range of expression by which a man can be described as a “man” is HUGE!

To muddle the entire topic even more, we’re told “real” men don’t eat quiche, play with dolls, cry, or do female-relegated things. Instead, real men smoke, drink, are daredevils and risktakers, play life hard, are into sports, love fast cars, exude machismo, love a good bar fight, are predatory, and are unmitigated lotharios. Seriously?!

Let’s face it: The definition of a “man” is mishmash. The core of what defines a man has been layered over with fear, insecurity, lust, greed, anger, and a major dollop of ego and vanity — not to mention fantasy characters found in romance novels and epic he-man movies.

I think what really defines a man is maturity. There are plenty of men lacking maturity who are in positions of power and control, who have fame and wealth, who have hundreds of thousands of followers on social media, who party hardy to the tune of sex, drugs, and rock-n-roll. I don’t believe any of that has a thing to do with being a man.

To me, being a “man” is a mindset, one that requires stepping up to the plate of principled living: integrity, honesty, respect, neutrality, compassion, consideration, authenticity, inclusiveness, sincerity, heart, fairness, generosity, grace, nurturance and supportiveness, being of service, and expressing unconditional positive regard for all of humanity and all forms of life.

According to that definition, being a man requires the thoughtful capacity to see and hear another person without fear of being dismissed or diminished in any way. This kind of man isn’t

arrogant and doesn’t feel the need for constant attention and gratification. He doesn’t wear his resume on his sleeve or build himself up in front of others. He has no need to assert power or assume a position of superiority and authority over anyone.

A real man is comfortable in his own skin, confident in his maleness. He isn’t threatened by those who are different, doesn’t need to prove himself, doesn’t rely on others’ opinions of him, and is grounded in his own being. His definition of success is about how he considers himself within the framework of living a principled life.

Let’s look at this from another angle, that of renowned painter Georgia O’Keeffe, who said, “Whether you succeed or not is irrelevant, there is no such thing. Making your unknown known is the important thing.” That’s the journey for a man: making the unknown known.

What the “unknown” is presents a challenge for men because we’re taught to keep our inner emotional being suppressed, to mask our authentic selves in order to impress the external world with our power and prowess. The expectation is that we’ll willingly march to an institutionalized drumbeat. Yet, deep within, men feel a full range of emotions that run counter to socio-cultural stereotypes.

The approach for many men then is to remain guarded and cloaked, a protectionist strategy employed to keep the “unknown” secreted away from the rest of the world, even one’s family. We become, in a sense, ghosts in a shell, simulacrums.

Because of this learned policy, we’re left wondering what the heck is going on in a man’s head.

One wonders what a man truly aspires to become given the petri dish full of humanity’s artificial conventions, aberrant intentions, and delusional constructs in which he is supposed to flourish. This is causing many men to experience tremendous stress and fear.

Thomas G. Fiffer, in his 2018 article published for The Good Men Project, listed rejection, irrelevance, and disappointment as “The 3 Things a Man Fears Most.” He says that the three coalesce into one primary fear that can overshadow everything in a man’s life: fear of failure.

Society, cultures and systems put a lot of pressure on men to succeed, a pressure that begins at a very young age. Boys are channeled toward “boy” things that have an underlying theme: winning = success. As boys move into adulthood, success reaps rewards: The better you do, the more you get and the more significant the prize. If a man fails, it can be like a deathblow leading to depression, hopelessness, loneliness, and a feeling of being obsolete/unwanted.

• Men die by suicide 3.53x more often than women

• White males accounted for 7 of 10 suicides in 2016

• The rate of suicide is highest in middle age — for white men in particular

Our society has created an intense culture of accomplishment dependent on external values geared not toward being a human being, but on achievement and the garnering of power, control, authority, wealth, and renown. But as soon as those things are taken away, though, we’re left with just ourselves. What kind of person we’ve become in the process is the crux of our journeys.

It always comes back to each man asking himself “Who am I?” The answer is found in where we focus ourselves. As soon as we step outside conventional descriptions of what a man is, we have freed ourselves. We are no

longer seeking to “fit in” according to someone else’s parameters of manhood, no longer trying to sat isfy another’s need for normative maleness.

Becoming a man is a journey, one that requires self-assess ment in alignment with one’s individual path. There is no “ideal” man, no perfection to be sought, no rubric to which men must ad here — but there is a continual letting go of preconceived rules and standards about what comprises a man.

One of the most important life tasks a man has is to shed the world’s one-dimensional un derstanding of manhood, to avoid compartmentalization and labeling. His path is one of discovery, of removing the veils of illu sion. Searching within himself, a man will find his true self, and along with that, his true purpose in life.

A man unfettered by the socio-religio-cultural norms of what defines a man is like the unfettered light of a lamp glowing with innate inner power. That light reveals truth, it nurtures, enlightens, and lights the way for others. In this evolutionary process, a man gives the greatest gift he has to offer to himself and the world: the truest essence of himself.

As Buddha proffered, “Be your own lamp.”

David Christel is a writing coach, editor, ghostwriter and author. He serves as a Special Adviser to CODE M.

Manhood by Doug Huron

Looking back, I associate maturity — what it means to be a man — with courage and decency, and also with family, the importance of a reliable father. My dad taught me what it is to be a man. He’s been dead nearly 40 years, and I still miss him and dream about him.

Dad taught me about courage. As a kid I didn’t have physical courage. I was afraid to fight other boys, and never got into hitting in football, even though I played boys’ club football and won the outstanding lineman in the 115-lb. division in 1959. I thought about physical courage and wondered how I’d fare if ever faced with combat. But I always prided myself as having moral courage — the guts to do the right thing, regardless of other people’s opinions or difficult circumstances.

Dad had both physical and moral courage. Like most men in his generation, he served in the armed forces during the Second World War. Dad joined the National Guard early, perhaps before Pearl Harbor, and was in the army in Louisiana for most of the war. But his younger brother Don was the tail gunner on a B-17 and was shot down over Austria in May 1944; he and was a POW for a year. When Don was shot down, Dad wanted to do something, so he took a bust in rank and went to Fort Meyers, Florida to train as a tail gunner on a B-29. He was scheduled to go to the Pacific when the war ended. After the war, Dad boxed at a gym on his base and took jujitsu, which he wanted me to study when he learned I was scared of fighting.

Dad also had moral courage. He stood up for simple decency. I learned early on that “nigger” was a forbidden word in our house, and that I should not use it. And I didn’t, even as I experimented with profanity. I never asked my folks why they were so resolute about not saying “nigger.” I suspect Mom would have said it isn’t polite. Maybe Dad would have explained the sordid history of the term. But my parents weren’t politically conscious and did not think of themselves as liberal. They were just decent.

When I was quite young, we kids would ask on another, “What are you, Protestant or Catholic?” I don’t know why, because the answer didn’t seem to matter. One day I asked a kid, and he said neither. I was puzzled and asked my dad. He told me the kid must be Jewish. What does that mean? “Well, Jews don’t believe in Jesus.” I must have looked shocked, and whatever he said, it was clear I should not hold that against them. It turned out that Dad, a Unitarian, had a long-running correspondence with a rabbi on philosophical and theological issues.

Dad’s great uncle Frank, the brother of his grandfather, was a Civil War hero. Frank was the standard bearer for the 70th Indiana. When Dad was a little boy, he would listen as Frank talked about the Battle of Peachtree Creek, the first fight in the Battle of Atlanta. The gunfire was so fierce it snapped the flagpole that Frank was carrying. He bent over, picked up the flag, held it over his head and rallied the Union troops to victory. After Peachtree Creek, he declined a battlefield commission, commanding black troops. When Dad learned of this, he was upset and offered excuses; maybe Frank just didn’t want the responsibilities of command. He didn’t want to believe that racism infected his family.

When I was in high school, a mixed race couple moved into the apartment project where we were living. The wife was white, so initially their application was accepted. But management soon learned the husband’s race, and they were evicted. I remember Dad going over to say something he hoped would be consoling.

Dad told me that a real man never strikes a woman. The only other time I remember his explicitly telling me what he expected me to do as a man was when he told me (at age 15): “If you ever make love to a girl, then get mad at her, or look down at her, because she was nice to you, I want you to go to a doctor, get yourself castrated and send the bill to me.” I sometimes neglected that lesson but never forgot its importance. I repeated it, verbatim, to both my sons. Apart from these two comments (about not hitting women and making love graciously), everything I learned about manhood was by observing my parents and their values.

My emergence into my own sense of how to be courageous and decent was not tied to traditional milestones, such as religious events like a bar mitzvah or first communion. Graduating from college was certainly memorable, but didn’t affect my manhood. Same with getting out of law school, or getting married in ’69.

When

I was 15, Dad told me, ‘If you ever make love to a girl, then get mad at her, or look down at her, because she was nice to you,

I want

you

to go

to

a

doctor,

get

yourself castrated and send the bill to me.’ … I repeated it, verbatim, to both my sons.

I think I began to be a man in early 1972. In January 1972, the Alabama NAACP sued the Alabama state troopers in Montgomery, which had only one Federal judge, the legendary Frank Johnson. The troopers had never had a black officer and were the instrument used by governors like George Wallace to enforce segregation. Judge Johnson, in contrast, had been desegregating Alabama institutions ever since President Eisenhower first appointed him. In 1956, he was on the court that struck down the Montgomery ordinance requiring segregation on buses, against which Rosa Parks and a young pastor, Martin Luther King, Jr., led a boycott.

At that time, there were no job bias laws allowing the Justice Department, where I worked, to sue state agencies like the Alabama state troopers. No problem: Judge Johnson ordered the United States to participate as amicus curiae with the right to examine witnesses at trial. After the order, my boss in the Civil Rights Division said I should go down to represent the United States. I was 26.

The troopers were about to hire a class, and Judge Johnson conducted a hearing in early February. At the end of the hearing, the head of the trooper force spoke up, saying that the state desperately needed to hire more troopers, so he pleaded with the judge to rule quickly. “Well, I can tell you what I’m going to do,” replied Judge Johnson. He said Alabama had unconstitutionally excluded blacks from the position of state trooper. And from now on, the state would be required to hire one black trooper for every white, until the trooper force was 25 percent black.

That was an extraordinary remedy, and it worked. Today Alabama has more African Americans serving in the state police than any state in the country.

The night of the trooper hearing, I talked to my wife in DC. She told me she was pregnant with our first child, a daughter.

I’m now 73. For many years, until around 50, I wondered if I’d ever grow up. Thinking about manhood, I again appreciate my debt to Dad. Maybe I became a man in ’72, where I helped courageous people to right a wrong, and learned at the same time I was going to be a dad.

Doug Huron served as Senior Associate White House Counsel in the Carter Administration and later represented Ann Hopkins in Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, the landmark 1989 Supreme Court case that established that sexual stereotyping can be unlawful and that resulted in the first – and still the only – court-ordered admission to partnership. He lives in Washington, DC.

Fewer cultures or people in this day and age go through traditional rites of passage or ceremonies, as we have understood them to be. But something considered “coming of age” was very much part of the culture I grew up in, and was still common when I was a youngster, amongst the Konde {Ngonde) people of Northern Malawi, also closely related to the Nyakyusa people of Southern Tanzania.

This relatively informal process centered on boys/young men, usually in their mid to late teen years. “Coming of age” for them was an expectation that their cohort — male peers born within 4 or 5 years of one another — would leave home and start their own generational age village, with some flexibility in these boundaries. The administrative or ruling system had a theocratic king (paramount chief after the colonists came in), who was elected by nobles and members of several royal families from among their ranks, sometimes in rotation. These kings then ruled through a series of levels of different chiefs, down to sub-chiefs, all of them from royal families.

It was the responsibility of the sub-chief in each jurisdiction to assign space or land where these ‘age villages’ would be located for any particular generational group. When this was still the norm, land availability was not a problem for the population. Land would be given first to the oldest one of the particular generational group; he would be expected to build his house on the parcel given to him and move out of his parents’ home because he was now considered a man. This process would continue until this cohort of boys/young men had all moved out of their parents’ homes and built their houses next to each other with space for growing their respective bases.

The homes were built in a line (lukindi), all facing the same direction, with space between the houses and the public right of way that connected them to the larger community. This ‘age village’ is where these boys / young men would get married when they were ready. Each generational group was understood to get older

Geoffrey S. Mwaungulu, M.D., MSA, FACP

together, have children closely together, and build their families in a coherent communal community. Helping each other was the expected norm in the group that ‘came of age’ together.

While there was no universal requirement to participate in this ritualized procedure, peer pressure meant that anyone not participating would be looked at askance. It went on until the 1950s, when things started changing. It was harder to start new villages, as population growth made land scarcer. Chiefs were losing their power to be able to assign new areas for ‘age villages’, and generational cohorts were scattering away from the communities, going away for schooling or work, things that were becoming more important for modern times.

A continuing influx of people who were not from this type of culture also mitigated against the contin uation of these ‘age villages’. The Konde theocratic king lost a lot of his power when the country became a colony of the United Kingdom, as he now had to answer to some English Ad ministrator with little under standing of Konde cultural imperatives.

For the Konde people, the coming of age of these boys/young men served additional im peratives important to their traditional cul ture. The society was polygamous, and the regulated flow of young men out of their fathers’ homes meant the latter were free to bring in new young wives. There was always the potential of a son mistaking a father’s new young wife as someone he could start courting himself, but this possibility was

very much reduced when the young man moved out.

As for the sons who were now looked upon as having entered a man’s age, they acquired a new independence, greater control over their futures, and could begin to look for brides of their own, and to establish themselves among their peer groups.

Without judging the traditional Konde practices described here, we can acknowledge that the environment and culture that once made them possible and essential, continue to recede into the past. It remains to be seen what consequences will evolve as age villages are steadily displaced by the new global village.

Geoffrey S. Mwaungulu, M.D., MSA, FACP, is a retired Internal Medicine physician, a Fellow of The American College of Physicians. He moved to Florida after a career practicing medicine spent largely in metro Detroit, Michigan. While still spending some hours in clinical practice, his 14 years or so before retiring were spent at health insurance plans as a Medical Director.

by Alan Osi

The groundbreaking anthropologist Dr. Joseph Campbell once argued that our society suffered from lack of an initiation ritual wherein manhood is defined for boys transitioning into men and a trial is passed, one that shows them how to embody the principles of manhood as defined by society.

Our society has failed to adequately define manhood for me. More accurately, the definitions of manhood, womanhood, and adulthood have been grounded in material concerns, in ways that are suspiciously good for the economy and captains of industry. But those definitions are generally bad for family, for wholeness, and for a properly functioning society.

This is my belief. It was my belief even as a preteen, and so, rejecting the definitions of manhood available to me, I had a longer, winding path.

Without an initiation ritual, the attainment of manhood can only be seen in the rearview mirror. Looking back you observe a series of decisions, trials and life lessons that define who you have hardened into being.

For me, this journey was in large part about self-definition. We live in a society of toxic hierarchy where people seek power and status. Power and status, as a whole, are currently conceptually inseparable from the many ways in which power is abused.

A clear example of this can be seen in the “Me Too” movement: the majority of men in Hollywood who’ve spoken about it without being directly implicated tended to say they knew nothing of various allegations. I find this convenient, as it implies they existed in a toxically misogynistic culture and somehow didn’t notice the toxicity, were never confronted by it, and therefore never had a choice whether or not to be complicit.

At best, these men are splicing the truth: meaning, at best, “no one ever specifically stated to me that “so and so” [insert name of sexually abusive, hierarchically powerful male] had sexually abused anyone.”

That it would be a surprise, however, that such behavior is going on is frankly ridiculous; ignorance in this case is, surely, willful.

This circles back to self-definition when one considers the reason for complicity: if one accepts the current defini tion of manhood, in which self-worth is based primar ily on one’s station in the hierarchy of society, one can, and sadly must, be complicit, in some form or another, with the inherent inequality of the hierarchical soci ety in which we live.

In order to choose another life, it was first incum bent on me to find another belief system, another way of looking at the world.

And so, my thoughts on this matter led me to radically self define, an activity which is in separable from also defining the world for oneself. I questioned every belief system, including premises so far underneath the surface, I rarely hear people discussing them. Eventually, slowly, my own world view came into picture.

From my rearview mirror, I knew I was a man was the moment I realized I was like a computer attempting to run two different programs. I was trying to live from two worldviews — the one I’d inherited from society and family, and the one I’d built for myself.

The one I’d received from society is chaotic, full of inconsistencies and contradictions; such as, “Believe in a messiah that who says ‘give away all you own, and follow me,’” but dedicate yourself to taking actions designed to increase the greater good for all and leave the world a better place than you found it, but actually strive to attain as much wealth and status as possible, and look out for number one.”

While a self-defined worldview is malleable, and therefore not subject to the same inconsistencies as the one received from society, there are dangers in living from self-definition. Marginalization is assured, and if you accept beliefs that are inconsistent with reality into your worldview, the results can be catastrophic.

Knowing this, there are few choices more terrifying, and requiring more bravery, than to radically self define. For me, who’s always seen serious flaws in the worldview I was given, there really was no other choice, but to live half a life.

And so for me, I truly became a man was the moment I accepted this fact of my life as a fact, independent of the beliefs and feelings of those around me. In other words, I became a man when I decided to be my own.

Alan Osi is the pen name of a novelist who works in the B2B economy in the Pacific Northwest. The son of civil rights activists, he developed an eye for spotting social tension from an early age. The youngest of four siblings, he has always danced to his own beat.

by Neal Howard

The first time I felt I had started the transition to adulthood was when I got my first career job. I had done two years of internships in my field but having my first actual career job felt more real. Seeing myself function in this job, I began to feel the transition into my career had occurred. Earning a salary in my career field – different from jobs I did during college – was a concrete and symbolic progression into what felt like sustained adult functioning.

It was at this point I discovered who I fully was.

Another central component to my development into the adult I have become was the discovery of my spiritual personhood. As an adolescent I struggled to comprehend how the vast diversity in faith and belief systems throughout the world and human history could exist within the monotheistic framework to which I firmly subscribed. Claims to sole possession of the divinely taught knowledge of precisely what and how to worship on the part of respective faith systems to which I was exposed drove my struggle to find spiritual understanding and identity.

How could one truly know which theology was correct?

Even more perplexing, if an individual, community, or society sincerely followed what it was they came to believe, how could they be barred from the mercy of God? The fundamentalist strains within multiple faith systems further challenged my search for answers.

I had been exposed to ecumenical theologies, particularly within the Christian faith that was my family’s primary spiritual heritage, but they were not enough to satisfy my primary questions and doubts. I explored Christianity in my late adolescence and early adulthood but had personal conceptual struggles with the concept of Trinity. There was fundamental confusion and cognitive dissonance both in thinking and worshiping: who was being worshiped, God or Jesus? I could not reconcile how they could be one in the same and/ or separate entities all at once. Who took priority? I could find no discernible or adequate answer. I wanted to be able to accept Jesus wholeheartedly as lord and savior at the end of worship services; doing so would mean I had found my spiritual home. I however was never able to get there.

As an adolescent and young adult I also had exposure to Islam and Islamic inspired concepts. My maternal uncle and cousins were practicing Muslims. Islamic language was a component of cultural identity and expression, especially within the realm of hip-hop music and culture, for me as a young black man approaching maturity.

Many Muslims were premier artists in hip-hop during my ado lescence/young adulthood (my generation affectionately refers to this time in the 1990s as the “Golden Era”). Such artists in cluded Rakim, Gang Starr, Poor Righteous Teachers, Brand Nubian, etc. The 5% Nation was a derivative of the Nation of Islam, which itself was inspired from Islamic theology altered and taught by Farrad Muhammad who sought to introduce Islam to Detroit’s African American communi ty during the 1920s.

Thus, the idea or concept of Islam as conveyed through hip-hop and icons like Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali became appealing to me. But I never saw Islam itself as a viable spiritual option for me. Despite knowing my uncles and cousins, I had faulty as sumptions about Islam, particularly that women were not considered equal, thanks to inaccu racies perpetrated by non-Muslims and, even some Muslims themselves.

In my mid-twenties I finally realized Chris tianity was not a theology I could come to believe in or practice wholeheartedly. For this and other reasons I decided to explore Islam and sought the help of my uncle and cousins (I will forever be thankful to them for their help and support in this regard).

The first time I attended the Muslim prayer service and performed the “salat,” the Muslim prayer, I felt something inexplicable and profoundly resonant when I completed the prostration component of salat (kneeling and touching one’s forehead to the ground). When I subse quently read the Qur’an I was nothing short of shocked, in the most sublime fashion possible, with how much sense it made to me. Here was scripture that spoke to and matched everything that I fundamentally believed.

Divine inspiration and teaching exist within many different faiths in humanity. Diversity in race, culture – even religion – is a sign of God’s existence and majesty. There is mercy and blessing for any individual, regardless of faith, who seeks to obey God and do good in the world. Equality between men and women is in fact affirmed and ratified in the Qur’an. It was at this point I discovered who I fully was.

I do not say or believe that I converted to Islam. Rather I have been a Muslim my entire life and made this essential and existential discovery when I was 26 years old.

Neal Howard is a clinical social worker practicing in Boston, Massachusetts.

by Daniel Nussbaum

“How does one grow into becoming a man?” is not a question I have thought about frequently. Simply stated, being a “man” is not at the core of my identity. I do often reflect on if who I am reflects the values of the kind of person I want to be, or even the kind of Jewish person I want to be. I sometimes wonder if I have become the partner, father, grandfather, or friend that I have striven to be. But I can’t recall the last time I asked myself if something is the “manly” thing to do.

As much as my father aspired to the dominant culture’s model, the model he provided us diverged from the dominant cultural model in a significant way. His intermittent employment meant he could no longer play the breadwinner role expected of him as presumed head of the household.

One might expect me as Jewish man to begin my reflection on the process of becoming a man with my bar mitzvah. The bar mitzvah (literally, “son of the commandments”) is a ceremony for a thirteen old Jewish boy (and in recent decades a bat mitzvah for a thirteen-year old girl) that allegedly inducts him into manhood. Thousands of Jewish boys over the centuries have been told on their bar mitzvah day “today you are a man.” This pronouncement was truer in the past than it is today.

According to our family history/mythology, my paternal grandfather left central Russia at the age of 14 not soon after his bar mitzvah with only his younger brother seeking work in the United States. Today, the age of 13 is more of a transition from tween to teenager than to adulthood, and the bar/bat mitzvah more a ceremony of community, continuity, and survival than transition.

But while the bar mitzvah no longer serves as a Jewish guidepost for the transition to manhood, there is a Jewish concept that has been very relevant to my own transition to adulthood and manhood. This is the concept reflected in the Yiddish word “mentsch.” The simple translation of mentsch is “man” or “human being,” but its connotation is much more profound.

In my own journey to manhood I have come to value mentsch as the model for me to emulate as a man. For me, calling someone a “mentsch” is the highest compliment one can pay him or her. To call someone a mentsch is to say that he or she is a decent human being in the most profound and meaningful way possible. A mentsch is an ethical and caring person, exhibiting the best qualities to which a human being can aspire.

Of course, being a mentsch is only one model of being a man among many I could have chosen from, but I am clear that the point at which I consciously chose this model is when I became a man.

So, what then is the process by which a young man chooses the model for the man he aspires to become, by which I chose my model of manhood?

The first of two entry points has to be one's most immediate role model, which for me, like many but by no means all males, was my father. The

second consists of the messages that the culture, particularly the dominant culture, sends us about what a “man” should be, keeping in mind that for Jewish men the dominant culture’s messages sometimes diverge from those of Jewish culture. Over time, for example, I have come to understand how the dominant culture’s traditional stereotype of Jewish men as urban, intellectual, physically weak and unathletic influenced my father who, wittingly or not, fought to escape these stereotypes by choosing the life of farmer and developing his athletic prowess. He attended an agricultural school which was established intentionally to keep Jewish men away from the cities and bring them back to the land (ownership of land was forbidden to Jews in many European countries from which they fled). After graduation, he started the small poultry farm where I was born and raised until almost 8 years old. Like many small family farms, ours didn't last through the 1950s, but my father’s combat with stereotyping persisted in his insistence on our participation in athletics. “Don’t think you are just going to come home every afternoon and just do homework,” I was told.

As much as my father aspired to the dominant culture’s model, the model he provided us di verged from the dominant cultural model in a significant way. The loss of the farm led to a life of intermittent employment, and thus he could not play the breadwinner role that the broader culture expected of him as presumed head of the household.

It took me a long time to understand what this must have meant for his own self-esteem and sense of manhood as he understood it.

Beyond the economic impact on our family was the psychological impact, the embar rassment I felt as I avoided answering the question, “what does your father do?” This is, however, simply insight and not a tale of woe. The fact that I received conflict ing messages about the appropriate model for manhood from Jewish and American culture, and that I did not grow up in what was considered at the time a typical male-dominated household, liberated me from a very limited sense of my options for what I could choose to do to become a man. It perhaps helped me to navigate more effectively the vast changes in images and expectations of males that have influenced our culture in the decades that followed as my own journey to man hood unfolded.

There is no Jewish religious ceremony like the bar mitzvah to celebrate the moment at which a Jewish boy really becomes a man. But if there were, I would have wanted my ceremony when I was fully confident that I had truly become my “own man,” and not necessarily the man my father was, or the man society expected of me. It would have been at a point in my life which evolved through a series of choices, some of them more instinctual and less intentional, and then continually with greater consciousness and intention. These choices included, but were not limited to a more shared partnership with my spouse than was traditional, a conscious decision to be more available to and more affectionate with my children, seeking greater balance between my family and career, and focusing my energy more on who I want to be than what I want to be. Can I truly say now that “today I am a man?” Most of the time.

Daniel Nussbaum is a rabbi and professor of education at University of Saint Joseph in West Hartford, Connecticut. He and his wife are parents of a son and a daughter.

J. Everett Prewitt

It was typical as a teenager to look forward to reaching the age of twenty-one and becoming a “man.” A definition established by age but not deed. After having achieved that goal, it never occurred to me that I hadn’t yet arrived. What I learned in retrospect was that there was no defining moment, no specific situation, and certainly no age attainment that established my manhood. Rather, it was an accumulation of events that contributed to the transition.

Some would say I became a man at the age of seventeen when, while working as activity director at an elementary school, I stopped an adult from dragging a woman by her hair across my playground. Or the time I stopped a football player at Ohio University from taking advantage of a drunken co-ed. Or it might have been the time at the age of twenty-three when I brushed fear aside and helped set up an ambush for the Klan when they decided to invade our campus at Lincoln University.

Certainly, I felt of age after college when I got my first apartment confident I could handle my business.

But then I got drafted.

The Army advertises making men out of boys. In basic training, I scored 500 out of 500 on the physical training tests. In Advanced Infantry Training I won the pugil stick and the 45-pistol championship. In infantry Officer Candidate School I graduated near the top of my class but through it all, I can’t pinpoint whether or if any of my Sergeants ever gave my manliness a thumbs up even though physically, I was up to any task they requested.

Maybe it was when I disembarked from a Huey helicopter and watched black body bags being stacked like cordwood my first day in Vietnam and became aware that life was not a given. Or when the realization hit me that I was not only responsible for my wellbeing but for every soldier in my platoon. It certainly could have been when we were taken by complete surprise at Dau Tieng where I and five men stopped the enemy from breaching our perimeter while some of our comrades fell.