MIRAGE

Literary and Arts Magazine 2025

Cochise College

Cochise County, Arizona

Faculty Advisors

Shelby Litwicki

Ella Melito

Alex O’Meara

Virginia Thompson

Jay Treiber

JenMarie Zeleznak

Front Cover Art

Designed by Monique Vargaz

Submission Guidelines

We accept submissions on an ongoing basis. For information on the new submission guidelines for your original writing or artwork, please visit

www.cochise.edu/mirage

We accept original poetry and prose (fiction and memoir), as well as photos of original art. Everyone in Cochise and Santa Cruz counties can submit their work for consideration.

Acknowledgements

The Mirage committee would like to thank everyone who submitted their work, faculty who encouraged students to participate, and community members who helped spread awareness.

We also thank our proofreaders, reviewers, and the design contributions from the DMA 210 and ENG 257 classes.

Finally, we thank the Dean of Liberal Arts, Dr. Angela Garcia, for all of her support.

Mirage Mission Statement

The Mirage Literary & Arts Magazine has a three-part mission:

1. Mirage serves Cochise County by showcasing high-quality art and literature produced by community members and students.

2. Mirage serves Cochise College by establishing the College as the locus for a creative learning commuinity.

3. Mirage serves Cochise College students by providing them an opportunity to earn college credit and to gain academic and professional experience through their participation in ENG 257, Literary Magazine Production and Design. This course is offered each spring.

Disclaimer

Mirage and its staff are not responsible for the veracity, authenticity, or integrity of any work of literature or art, or for any claim made by a contributor appearing in the publication.

Copyright

All rights herein are retained by the individual author or artist. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form of by any means without written permission of the author or artist. Copyright law dictates that if a portion of a work is used, it must include the full acknowledgement of the title, author, and magazine. Printed in the United States of America.

© Cochise College 2025

2024 Student Poetry, Prose & Art Contest Winners

The Mirage holds an annual contest in the categories of poetry, prose, and art. All submissions from students are automatically entered into the contest.

Art:

First Place: J Vega, “Child of Spring”

Second Place: Mark Logan, “experiment #5”

Third Place: Vernice Garcia, “Goddess of Time”

Poetry:

First Place: Emmaline Fisher, “Ebb and Flow”

Second Place: Emmaline Fisher, “Bigger Heart”

Prose:

First Place: Emmaline Fisher, “The Captain Goes”

2024 Creative Writing Celebration Winners

The Mirage also publishes first-place winners from the previous year’s Cochise Creative Writing Celebration contests in poetry, fiction, and memoir.

Are you a student who wants to participate in producing this magazine?

This course offers students the opportunity to participate in the design of the Mirage magazine and website.

Students will participate in learning activities that focus on visual and literary analysis and magazine design in both digital and print mediums. The production process, from concept to publication, will be discussed in detail and practiced using InDesign and Photoshop. Students do not need to have any knowledge of these programs, but they do need to be comfortable using Microsoft Office programs in order to take the class.

Contact Us

Questions should be sent to mirage@cochise.edu

When hard copies of the Mirage become available, announcements are posted on the website and on our Facebook page. Copies are available in a digital version on our website.

View our website at cochise.edu/mirage

Follow us on Facebook at facebook.com/CochiseMirage

Ebb and Flow

Emmaline Fisher

Poetry Student Contest Winner: 1st Place

Love came to me the other day, on a street corner moving swiftly past, in the rain, in the lightning, in the monstrous city. Love surfaced below a vast, consuming network of clouds and color-changing sky, on those stupid rental scooters.

Love caught up to love at a red light and kissed gently, and swiftly, and sweetly, before the rain and the changing light washed them away. The other day, the world was a dream, dressed in red, and yellow, and green.

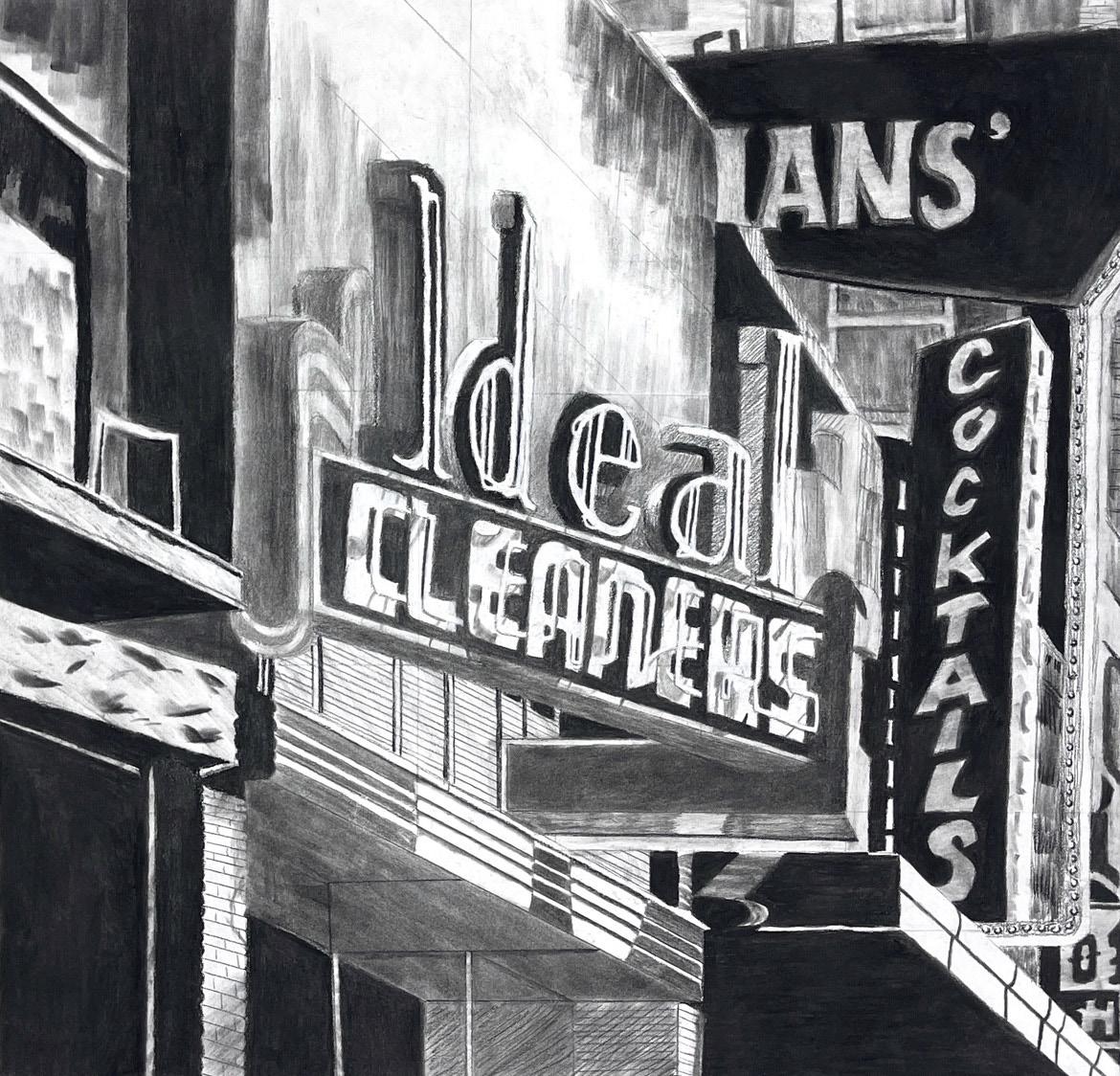

Downtown

Luis Cornejo

Woodfired Mug

Dale Miller

Carnival of Sorts

Dani Foti

Flying Fish

Stephen F. Bonnet

The Captain Goes Emmaline

Fisher

Prose Student Contest Winner: 1st Place

The arroyos had dried up months ago. Old man Gideon had fallen on hard times, and the congregation likened him to Job upon hearing news of any goings on. He wasn’t one to talk of misfortunes, but his appearance spoke for itself. When he rode into town for a service, he looked like he’d seen the devil, not that any of the other well-established individuals from the rush looked much better than him—he’d already turned his children free when he settled on the edge of the range—but time seemed to be catching up to him.

He lived on the arroyos as though he were a sailor that saw the ocean in them. He handled his pan as though it were a ship, and when he had a bit of luck, it wasn’t uncommon to see old man Gideon swaying on his good old horse as if he were seasick. He certainly wasn’t the type to be in low spirits. His eyes were just slivers, visible only from the wrinkles pouring out of them, as evidence of his time in the sun and his good nature. He had a permanent ruddy complexion but would only ever complain of the cold. He laughed heartily, never

afraid to flash his golden tooth, and wore the dirt under his nails with pride. His beard grew long and stringy and looked nearly pure white.

Come the drought though, that beard was more often the color of ever-present dust and stubborn tobacco residue. Sure enough, he liked to smoke, and he was usually just reasonable enough to know when to hold his pocketbook a little tighter. It just so happened that when his streams dried up, so too did his wallet. He’d burned his last leaves and sucked on the last of his store of chewing tobacco, but a man with no water can’t bathe, so there he was. Sure enough, these days he looked as though he could have been wandering in the desert for forty days and forty nights.

Father Matthew knew he was called to serve his church. He was wet behind the ears when he’d met old man Gideon, and they would make conversation as Father Matthew swept away the dust from the pews with unspotted hands, but now both were older and less lively. Somehow

throughout the years, the two spoke less but understood more. The dust that had seemed hardly worth a thought in those earlier days started to pile up and get in the way.

Week after week, he’d chastise the proud and uplift the hopeless. Over the terrible course of the long summer, his congregation shifted towards the latter. After his sermon, he’d listen to his people, recording in his heart news of the next birth, the next convert, the next death. Father Matthew saw the tanned faces grow gaunt as they passed through the heavy wooden doors, heading out of the burning white sun and into the cool darkness of the nave. Like most places leveled by drought, the church grew emptier. Slowly, the number of faces grew smaller.

Old man Gideon, though, seemed to have a different face. His grew thinner, sure, but it just made the skin between his eyebrows furrow more. His eyes started to sink deeper into his face. If one could hear his prayers when he knelt down on the shady church floor and held his prim white ten gallon with an iron grip, they’d get the odd feeling he’d rather find a way to drown in that grim desert than dry out.

Father Matthew never bothered Gideon for his vices and the two were friendlier than most. Rather, he pestered Gideon about his attendance. For a while it seemed that old man Gideon only humored him—starting to show up most Sundays, then making appearances every Sunday—but by the time Gideon appeared on that Tuesday night as the sun began to set in the barren sky, most could tell that Gideon was coming to rely more on an uncertain faith than his leather-like hands.

Some said his skin looked paler. Some said he’d stopped smiling. Some said they saw the whites of his eyes for the first time. In the beginning, Father Matthew said it was just hard times.

That Tuesday, they began to exchange pleasantries like normal.

“I’m glad you came in tonight, Gideon,” Father Matthew said with a pleasant smile. He had graduated from his broom and now walked the pews cradling a bible.

“Hey there, Father,” Gideon replied from his seat. He held his hat over his heart and had been staring at the side of the wall that the confessional was on. There was a short candle lit,

flickering in and out below a small window showing an empty, fading sky. He looked lost in thought. Father Matthew thought that for the first time, he also saw the whites of old man Gideon’s eyes.

“To what do I owe your visit? What can I do for you?”

Gideon left his hat on the seat and stood up as Father Matthew approached. He brushed the stray hair out of his ruddy face and smiled back. “Just needed to think over a few things, Father.”

“If you’d allow me, I’d like to know what’s worrying you. You can cast your worries unto the Lord.”

“Well… I suppose I’ve just… I’ve got all the tuck took out of me these days. These knees of mine ain’t what they used to be. Nothing your Lord doesn’t already know,” he offered, crossing himself.

Father Matthew put the bible in his black coat slowly as Gideon shuffled to the end of the pew, eyes already on the door. Stepping closer, he put a steadfast hand on Gideon’s shoulder and softly spoke, “You can tell me anything, Gideon. He cares for you.”

Gideon hardly looked away from the door, reaching up a hand to meet the Father’s. “I think I’ve been a—a greedy man, Matthew. You know. I’ve wanted so much in my years, but I think I’m… alright.” He held the Father’s hand for just a moment before brushing it away and heading toward the exit. “I’m… grateful for you, Father,” he ended quietly, stepping into the night with a courteous grin almost entirely obscured by whiskers.

Father Matthew made the sign of the cross as Gideon closed the door and turned silently to the weary face of Christ, who hung ever so gracefully just above the altar. Slowly, Father Matthew again began to pace the pews. The ivory hat that Gideon had left behind lay perfectly beneath the gaze of the Son of God, and Father Matthew collected it quickly, following Gideon into the dark.

The full moon lit up the valley, and heat could still be seen rising from the baked earth. The Father’s robes swayed around him as he traced Gideon’s tracks to the post around the side of the mission, and there he saw old man Gideon, stroking his horse. Father Matthew stopped silently, taking in the same view

Gideon watched of the brush and the dirt and the drying cactus set against the moonlit sky.

As Gideon began to untie his mount, he doubled over suddenly. His chest heaved from the convulsions of a coughing fit, and he stumbled against the post as though he forgot he stood right in front of it. Dust gets to most people, but hardly ever as badly as it had gotten to Gideon.

Father Matthew saw red stains on Gideon’s handkerchief and made a few steps toward Gideon before the old man turned around. The Father stood still as stone, and Gideon knew that he had seen. Gideon made a look with his deeply sunken eyes that somehow seemed so bright in the moonlight—a look that almost passed right through Father Matthew.

They hardly moved for a good long while, and nothing else did either. There wasn’t a breeze, and there wasn’t the sound of a coyote or the sound of a cricket. There was only the smell of dust. The world seemed as though it had already stopped, and in those moments of nothingness, Father Matthew knew he was looking at a dead man.

Gideon almost chuckled in that quiet,

pleasant way of his, but all that came out was stale air. He teetered over to the Father, looking at his feet, and took back his hat with a slight tremor. Gideon turned his face away, covering his eyes with the brim, then sighed, sucked his teeth, and picked at his golden tooth with his soiled finger.

“You know, I oughta get back, Father.”

“Gideon-”

“You don’t gotta bother me about coming on Sunday. I’m thinking I’ll be busy.”

“I think I’d better get a doctor for you-”

“Aw, shit, Matthew! Just forgive me. Forgive me, please.” Gideon wrung his handkerchief between his shaking hands. “Don’t bother with finding my kids. I haven’t got anything for ‘em. And don’t put me next to my wife. I’m sure she’s had enough of me.”

Father Matthew had his own hands wrapped around the crucifix of his rosary. He looked at Gideon’s ten gallon, still somehow perfectly white, and back across the horizon as Gideon pulled himself, slowly, up into the saddle.

“Gideon… I think there are clouds picking up in the West.”

“I know it, Father.”

“Be sure you’ve found high ground when the time comes.”

Gideon stared at the cross on the top of the mission, then looked back down at Father Matthew. He said nothing but made the sign of the cross, wiped his red fingers on the handkerchief once more, and tipped his snowy hat at the priest.

Voices Makayla Rios

The Little Werewolf Monique Vargas

Bigger Heart

Emmaline Fisher

Poetry Student Contest Winner: 2nd Place

The Artist’s Pyre

Victor Marrujo

The boy has wings that cannot be seen in the sun but cast shadows on the ground This, he thinks, this is the evidence of my sin. Somehow, when there is blood in those wings, all they become is heavier. We kill God in our minds, because he is a lamb. No good deed, we say, pointing.

Crisp Autumn Leaves

Joyce Genske

Rock My World

Alice Duffy-LaBonte

Memories of Childhood

Karl Sullivan

Child of Spring J Vega

Art Student Contest Winner 1st Place

Pot Grace Megnet Flotsam

A.E. Williams

After the storm the interior of the house was a sea of debris, the kitchen a lake of ceramic shards and pot lids, tiny pools of shattered glass. The living room filled with shoals of tossed couch cushions stuck worn and bedraggled to the walls.

The bedroom held colorful islands of velvets and denims, fake fur holding a forest of bent hangers lifting forlorn branches.

After the storm of him leaving for the last time the yard became a sculpture garden of jettisoned boots and razors, ugly things that had not been welcomed when they first moved in. finally thrown overboard to lighten the weight that had almost sunk the ship.

When the tide next comes in the wave will sift through the flotsam revealing the shimmer of a jewelry box long vanished, smooth the glass shards into soft pebbled edges. And when the tide recedes the bed will float back down rearranged in a new geography preventing old memories from washing ashore. Sheets washed in torrents of salt water will change color and once dried in the sunlight of months that pass each other as ships suddenly appear on the horizon, will have lost the stench of the stormbringer.

The bed will face a different direction. Almost nothing lost will be missed. The rest will prove to be as imaginary as hot mirages on the far horizon.

Branch in the Vines

Ho Milosevic

Clyde Monique Vargas

Padre Kino

Gerry Gabel

The

Rocker

Bruno Talerico

the rocking chair, the old one on the south porch, rocks. moving rhythmically back and forth empowered by an unseen being. ghost?

an Apache warrior who died in battle, a Spanish explorer claiming new territory, Portuguese priest saving souls, Scottish settler taming the land, Italian farmer planting seed, or is it just the wind?

SUPERNOVA

Autumn Focus

Kevin O’Brien

Vernice Garcia

Seen Behind Bars

Juan Noriega

Drapery of Gold

Melina Christopher

Dream Monsters

Name of Artist

Calling Berlin

Kevin O’Brien

I was living then in a fourth-floor walkup in Kreuzberg, a rundown and shabby district of West Berlin. Conditions were not ideal. The apartment overlooked a gritty rear courtyard that abutted the cheerless neighboring courtyard. There was a view of grey walls, tiled roofs, and brick chimneys. For heat there were two coal stoves.

All the apartments in that wing faced north. I called my place Stonehenge because for two or three days in mid-June a shaft of sunlight pierced the kitchen window and divided the table in half. Those were the only days of the year that sunlight reached my apartment.

Sarah and Ari were the other bright spots. Sarah lived across the fourthfloor landing; Ari was my roommate for a time. Sarah’s mother was a professor of French literature at the Sorbonne, her father was a BBC correspondent who was sometimes in London, and her husband Aleksi lived in Moscow. She had married him partly out of love and partly to get him out of the Soviet Union.

Sarah had three passports and spoke

four languages. I asked her once what her native language was.

“French. No, German. Or English, maybe. I’m really not sure.”

I could use Sarah’s washing machine, saving me half a day of hauling my laundry to the subway for the trip to the laundromat, waiting for the washer and dryer, and then carrying it all down to the subway and back home again. As well, I could enjoy tea, conversation, and Santana while Sarah’s washing machine cycled.

Ari was fluent in German and Brooklynese. He spoke German with a New York accent. I learned from him to put a little New York into it as well, to say deh Fingah instead of derr Fingerr, and not sound so much like a gringo. Ari had a long, black frizzy ZZ Top beard and closely cropped black hair. He could pass for either an imam or a rabbi, depending on which part of town he was in.

One night Ari and I were at Habakuks, a dark and smoky joint on the corner. After a few beers I asked him, “Is it strange being Jewish in Berlin?”

Ari shook his head, lit another cigarette, and sipped his beer.

“Beyond words.”

“Then why here?”

“I was waiting tables in New York when a German woman asked me if I wanted to go to a party with her. ‘Sure!’ I said, and asked her where the party was. ‘In Berlin.’ Ari shrugged. “That was a couple of years ago. How about you, Kev?”

“I wanted to study East German literature.”

Ari gave me a look that said, “Come on, man.”

“I am signed up for a class.”

“No, I mean really.”

“Well, a friend told me you could drink beer in the movie theaters here.”

“I think you’re on the lam.”

“On the lam? From what?”

“I don’t know. That’s something you’ll need figure out for yourself.”

Berlin and its people bore not yet healed wounds of war. Bullet scars and shrapnel gouges pockmarked

the façade of our apartment building. Vacant, overgrown lots made gaps in the rows of apartment blocks. Rusted water towers and smokestacks like broken teeth poked up through trees that thrived in the rubble. On the other side of the Wall stood the shell of a synagogue, one of the largest in Europe. Its floor was littered with broken glass; saplings sprouted through cracks in the concrete.

There were few old men, but grimfaced old women seemed to be everywhere, wearing bulbous felt hats with narrow brims. Some carried miniature poodles in their shopping bags. There was a bar called Die Ruine, The Ruin, on the bottom floor of a bombed-out building. I struck up a conversation with an older man there once, a veteran of the war. When it came out that I was American, he asked if my father had fought in the war. I told him he had.

“I’m very sorry,” he said.

Ghosts of the past were everywhere. A forty year old phonebook. The coal cellar, its Gestapo concrete walls and naked bulb hanging from the low ceiling filling me with sadness and dread.

East German border guards in the Friedrichstrasse train station wearing jackboots, riding breeches and field grey tunics, black leather gloves and peaked caps turned up high in front.

Troops of goosestepping soldiers on parade in East Berlin, rifles held across their chests, drums pounding out the marching rhythm: Wham! Wham! WhamWhamWham!

A steam locomotive huffing past the platform, the fireman opening the furnace door and roaring flames swirling out of the firebox. The locomotive passing slowly, pulling a line of hoppers loaded with brown coal bricks, chemical tank cars, and boxcars, hinting at desperate cargoes in times past.

I told Sarah about finding the old phone book in a junk store, how it had opened to the government section, with the Reichs Chancellery address and phone number at the top of the page.

“Eeeech!” She shuddered. “You didn’t buy it, I hope. All that horribleness compressed between the covers.

“No,” I said, “but I wrote the phone number down.”

“Why?”

“Just curious. What happens if someone dials Hitler’s office?”

“Nothing, probably.”

“But what if? What if the line is busy? Or somebody answers?”

“You might be invoking the darkness.”

“Think of the story it could be.”

“You are the one to write it.”

But I never did write that story. I’d nearly forgotten about the whole thing until I came across a box of Berlin souvenirs not too long ago. It was high on a back shelf in the garage, hidden by all manner of chaos around it. In the box were a few books, postcards, a toy double decker bus, a model steam locomotive, a brick of brown coal, and the Reichs Chancellery phone number written in smeared pencil on a scrap of paper.

How the story might go is no clearer to me today than it was back then, but I know how it would end:

A telephone rings in a dank, dripping bunker. A dead hand picks up the receiver.

“ Ja ?” A pause, listening to what is being said on the other end.

“ Ja .” Understood.

Then “Ja !”, a promise.

Another pause, and just before hanging up,

“ Bis gleich .”

See you soon.

A Salad in the Making Diana Turner

Let’s Open This Door!

Sean Kelly

Dahlia Terrie Cervantes

Touch of Color on a Cold Day

Mainstreet in Fall Dale Miller

LaDona Hoornstra

The Long Run

Edward “Jay” Matchett

2024 Creative Writing Celebration Winner: Memoir

A reflection on the side-rail of my hospital bed greeted me like a hung over morning sun.

Above the trick of the light, I saw my mother, red in the face, earnestly wiping tears away. She never cried, not really. Detached and disoriented from anesthesia, I wasn’t sure it was real.

Dreamlike, the scene, hung outside of myself like a strange dispassionate painting.

A nurse entered the room. My eyes opened wider. Then another nurse came in— and another after her. Standing around the bed in a semicircle, the monochromatic audience appeared to be bearing witness. Seeing this, I sat up in bed. My mom set down the purse clutched tightly against her. She put her hands together as if in prayer, leaned forward to speak, but no words came. Her head went down. Elbows on her knees, she looked up – her eyes met mine.

“They found something,” she said. Her cryptic words pierced through the cacophony of hospital sound like a firm prick of the skin.

“Found something?” I replied in confusion.

“Yes, we’re waiting for the doctor to come back with results. We’ll know more soon. Del – the minister, is on his way.”

“Del? Del is coming here…to the hospital?” I asked.

“Yes, I think it’ll be good to have him –he wanted to come, for support,” she responded.

“Is everything okay? What about dad?” I asked more pointedly, tightness growing in my chest.

“Your dad didn’t answer. I called three times —- we will know more when the doctor comes,” she said. I slumped down. Lacking conventional maternal instincts, my mother’s detached manner contrasted sharply with the moment, akin to a dental x-ray revealing a cavity with resolute clarity.

Del arrived as we moved rooms. The minister, in full robe, sat down next to us. Amidst the beeping monitors and antiseptic scent, an aura of assurance filled the space. Pleasantries and greetings brightened the room marginally, but consternation still consumed me. A ticking clock stretched time to its limits as we sat there in concerned silence.

“He’s coming,” someone said. A moment later, the doctor entered the room, and the throng of uniform professionals parted to allow him to the front. He sat down on a stool and opened a file as he rolled closer. Words like ‘pathology,’ ‘pathologist,’ ‘oncology,’ ‘preliminary results’ peppered his preface. Finally, the surgeon said, “...which looks to us like lymphoma. We took out what we could, but we were unable to get it all...”

To a wide-eyed fifteen-year-old, these words meant almost nothing, except to signify a horrific diagnosis. I didn’t know what ‘lymphoma’ meant – or any of those words for that matter.

Adrift, I stared blankly at him. He sat for a moment in silence as he

waited for a reply. I said nothing. In confusion, I turned to my mother. Her eyes filled with tears to say, “Cancer, Jay.” She drew a deep breath, and in a teacher’s tone of reassurance, she said, “He’s saying you have cancer.”

Bewildered, my thoughts stuck to the interior of my skull like molasses. Words failed to form. Unable to process, unable to summon language, unable to even feel, I felt nightmarishly between awake and asleep. “Cancer?” I spoke to the floor. This wasn’t real – no one mentioned this as a possibility “Cancer?” I asked again. I burst into tears, “Am I going to die?” I asked. He scooted right up to my chair and said, “Probably not.” With a pat of assurance on my knee, he nodded.

“Probably!?” I burst out incredulously – I never considered my life in terms of probability before. The doctor lowered his head again. “Lymphomas have a high survival rate,” he offered. “So, you will most likely survive just fine,” he concluded, trying to reassure, albeit a little too honestly for me. The doctor paused; his eyes moved down as if he was trying to find words on the floor. He looked up again, “It’s going to be a

long race though, and this is just the starting gun. But I believe you will be fine in the end.”

Tears slid down my cheeks, falling like silent rain on my hospital gown. I closed my eyes and leaned over in sobs. No one touched me, though the minister reached for my hand.

***

On the second day back at school, my French teacher took me aside. She wanted to introduce me to a girl in her next class, saying “She’s had a unique experience I think you can relate to.”

Ms. Farrier’s introduction was simple, yet pregnant with meaning. “Abby, meet Jay. Jay, meet Abby. I think there’s much you two could share.” She slipped away, leaving us to talk. And as we did, it was clear we shared the same road to Damascus. Childhood cancer left her tethered to crutches and hand controls in the car, leaving no doubt of its legacy. Shared trauma gave us an immediate and wholly unique connection, creating the basis for a level of intimacy I had never known.

Abby taught me while a regular boy needs to keep their bedroom door open, a cancer boy could spend all

the time in the world with a cancer girl and have his door straight-up locked. We wondered if someone would ever knock, but they never did.

***

People talk of endless summer as a dream thing, but the summer of 2001 was endless in a purgatorial kind of way. For four months, I drank my fill of chemotherapy – round after round — a real bender. With little energy and London-level fog on the brain for so long, I learned time unfurls most slowly amidst suffering with no creative or physical outlet.

***

The screams were so bad my mom had to leave the room. The tears in my eyelashes made a dewy rainbow filter across my vision, going black every time I winced. A nurse gave me something to bite down on. Screams turned to moans. Chemotherapy withered my veins, making it impossible to find one able to carry the life-saving poison one last time.

A nurse on each side of the bed, they took turns driving needles into my hands. After one failed, the next would attempt again on the other side. Moving from hands to wrists, the process repeated itself. Recognizing they met their match, they stopped,

took out the needle, and said they were going to get a “real expert.”

A senior nurse with peroxide blond hair entered the room. She cursorily inspected my hands, wrists, and arms. She focused her attention on an area on my forearm.

“Here,” she said.

Piercing the skin, she threaded the needle underneath like a tailor, hooking the wayward vein just right. She tried the line; blood flowed back into the syringe with ease, mixing with saline like rosé wine.

“There,” she said.

***

I sat dissociating at the kitchen table. Though depression had descended like the rainy season in Seattle, a moving ray of light contemplated my fate with the opening of our sliding door. In the reflective glaze of a coffee mug, I saw my mom come in behind me from outside.

“Sweetie,” her voice came nauseatingly to pull me back to reality.

“What’s up?” I asked.

“Remember I said I was going to ask Mr. Cleary at school about how

you could get back in shape after chemo?” she replied.

“Uh huh,” I shrugged in indifference.

“Well,” she continued. “He’s head cross country coach this year. Did you know that? I didn’t. Anyway – he invited you to join the team. Practice starts in two weeks. He said it is a surefire way to get back in shape quickly.”

“Run cross country?” I asked. “Like that bastard Rudy across the street?”

“Watch the language – but yes – I think it would be good for you,” she said.

I knew what she was saying – she was saying I needed to lose weight. Steroids from chemotherapy turned my face into a pasty moon and gave me the stretch marks of a pregnant woman. Tapping into my insecurities and struggle with body image, which became particularly acute after chemo, she imparted a sense I needed to do whatever it took to get into shape as quickly as I could. Fat was an unwavering kind of unacceptable for her.

“For your health,” she said. “You wouldn’t want to get cancer again because you didn’t make healthy

choices,” she would say. Stressing the superficiality of teen peers, particularly how no girls would be interested in someone who “looked so sickly,” she made sure I understood I didn’t want to spend high school looking like that.

last. Standing in the front, looking down the middle aisle at the team looking back, I was struck by the glow of summer skin and how everyone seemed to fit. I mean, I looked nothing like these kids. They were beautiful; I was an ogre – in my mind anyway. I felt like a student about to take a test they are certain to fail.

On an overcast morning in August of 2001, still nearly bald from treatment, my mom dropped me off for my first cross country practice in Hoffman Park, a sprawling complex with fields and trails on the edge of town. I wore my faded Ohio State baseball cap to cover my scalp’s bare fairway. A heavy cotton shirt mated with oversized basketball shorts draped over my pudgy frame.

Standing on a big rock near the edge of the field, the coach said the plan was to take a bus six miles out of town and run back to the practice field where we stood. As his words landed, I thought to myself, “I could actually die.” Thoughts of a chemo-weakened heart muscle or a stroke swirled in my brain.

Clad in their well-fitting activewear and new shoes, one by one, athletic peer after athletic peer climbed aboard the bus. Ahead of only the assistant coach, I remember being

I sat down next to the assistant coach. Wheels turned, and the sun poked out from behind a cloud, revealing glistening morning grass along the road. Out amongst the cornfields and wild pastures, the varsity girls in the back sang along to the Dixie Chicks “Ready to Run.” Very much not ready to run, I was already sweating, and we weren’t even off the bus.

We came over a rise and slowed to stop at the base of a hill by a small farm. My heart pounded as the bus creeped onto the shoulder. “This is it,” the coach announced as he stood up to walk to the front. “Crap,” I thought.

We disembarked to stand along the side of the bus on the shoulder. The coach, who paced in front like a colonel inspecting a formation, instructed us to run back to the park and wait for the rest of the

team before leaving. Obviously, the instructions to wait weren’t for me – I would be an uncoupled caboose rolling into the station long after the train arrived.

The group took off running and it was immediately clear there was no one who ran at my glacial pace. Moving in more of a shuffle than a run, it wasn’t long before I had fallen so far behind I couldn’t even see the team. After a mile and a half or so, I thought about walking.

Ms. Hoffman, the assistant coach, ran up beside me, saying “You’re awesome! Keep going!”

“How many miles are left?” I huffed inquisitively.

“About five!” she shouted out like a spin instructor.

“Five miles?!” I shouted back between labored breaths. “Seriously?” I saw my reflection in her Oakleys.

“You’re rocking this,” she said in a breathy voice.

I wasn’t, but it was nice of her to lie. I heard enough; it was futile. I dropped to a walk. A cramping pain in my side, I watched the tall grass along the road sway in waves in the humid

wind. Still so far out, I couldn’t see the town. Corn stretched out to the wooded horizons. Ms. Hoffman took her leave once more, leaving only the birds on the wire as witness.

***

I passed the city limits sign. In the distance, I saw a figure running toward me. Mr. Cleary circled back to jog in place with me as I walked. To impress the coach, I started to “run” again as we neared the park. “Finish strong,” someone shouted from somewhere.

Running through the tree-lined boulevard into the park, the team sat at the edge of the soccer field. Seeing us, the team got up and started to clap as though I was about to finish something of actual significance – like a marathon.

I remember the crunch of gravel as we ran across the dirt lot. Ms. Hoffman ran up next to me. Both coaches clapped and cheered as we ran together toward the team. When we were just about to the team standing in the grass, we dropped to a walk. En masse, the group moved toward us, closing around us in a horseshoe. Then came the high fives, pats on the back, and a shower of praise from my teammates.

Completely soaked in sweat, like I had taken a shower in my clothes, I felt like a freak compared to the rest of the them, none of whom looked as though they had broken a sweat. Embarrassed by the attention and humiliated by the fact that merely finishing a practice was something to celebrate, I was still genuinely touched by the spectacle.

Tearing up as they clapped, I pretended to wipe sweat from around my eyes, simultaneously feeling part of something for the first time and more separate than I had ever been. I wanted nothing more than to just be another regular kid on the team that day. But alas, I was the cancer kid – a tragedy, inspiration, and awkward topic all in one. Celebrity through cruel distinction, sure, but distinctly part of a team now.

Then, in an awkwardly constructed sentence, he asked how it felt.

“It felt amazing!” I said with a coughing smile.

Beaming, he said, “I’m so proud of you! And you’ve never run a race before, have you?”

“Yeah, I have – a lot of them,” I said.

He cocked his head to the side.

“I ran cross country after cancer in high school, remember?”

Puzzled, he squinted his eyes — “You had cancer?”

After running the Bisbee 1000 — my first race since high school — I walked to my dad.

Arms outstretched, he put his arm around my shoulder to pull me close. Searching for words, his dementia shown through like a bad stain.

Identity & Devotion

Elric Mahoney

El Boliche de Agua Prieta

Sweet Expressions

J Vega

Anita Johnstun

Rainy Childhood

Estefania Ramirez Toscano

Copy Artist Drawing Kat Coppes

INSTEAD OF THE BORDER PATROL HELICOPTER

Tina Durham

2024 Creative Writing Celebration Winner: Poetry

An orange and yellow hot balloon drifted over my house today hissing its dragon-song, flame-blown silk billowing up and bravely clearing that last stand of trees before sinking into earth’s embrace on the far side of the creek. It settled meekly on the grass.

It moaned and sighed, exhausted as it toppled in slow-mo grandeur, bright airy defiance vanquished by the laws of math and damp earth.

Such songs stay with you forever, carrying you along like fire filling the heart’s hollow chamber with clear, volatile desire to trade this dirt and water for fire, air and aether.

Ocean in the Sky Andrew Belcher

Flow in Chaos

Luke Serna Lights

Vanessa Inzunza

Expression Adapts

Alejandra J. Gutierrez-Tapia

The Company of Men Gretchen Hill

2024 Creative Writing Celebration Winner: Fiction

The night smelled different from the day, which smelled mostly of dust and diesel fumes and trains. The day shook with the tectonic rumble of the approach, dishes clattering on the shelves and drainboard of Mr. Foster’s room in back, the heavy vacuum of wind as it passed, sucking at the farmers gathered on the porch, trying to pull them into its wake.

Nights were different. Only two or three trains came through. All around, a silence as thick as tree frogs hung in the air. The farmers were gone, and if you sat on the porch, you would first smell the bite of the sheet metal siding and roof, a bloody tang of rust. Under that was the dust on the concrete porch, then the sweetness of dried grasses and dry earth. Gradually, if you were to sit undisturbed for long enough, you would notice a smell coming from the bags of feed inside the store: grassy, grainy, like a horse’s neck. You might smell the stack of wooden pallets piled at the edge of the porch, the steel of the train tracks. Honeysuckle and skunk

cabbage in equal measure, the smell of heat in the summer, the smell of decay and fires in the fall.

Open the door and it’s a battle of aromas, the Feed versus the Must, a claustrophobic tangle of closed windows and Mr. Foster’s burnt coffee. In its heyday, when Mr. Foster’s father ran it, Nutrena Feeds was neatly and fully stocked, floor to ceiling, with bags of animal food, bales of hay, salt licks, vitamin supplements, animal treats. Then it smelled like a clean barn. But the younger Mr. Foster is more reclusive than his father, with an aversion to sunlight, and when the old man died, he boarded up the store windows, moved into the back office, and watched the business decline.

Still, old habits die hard, and even after the elder Mr. Foster is gone, his buddies come to his store and settle in on the porch. Remember the time that Lanky Skinner got his Ford Crestliner stuck in his father’s potato field during the rainy season? Or when Charlie Shandley lost his pinky making a cradle for the baby while

Mazie was pregnant? They listen to ballgames on Hank Fulton’s transistor radio, each recalling a youth when they thought theirs might one day be a name on Graham McNamee’s lips. Here they come, trotting up to bat, making a sacrifice fly, sliding into home, catching an over-theshoulder popup.

In the store, the young Mr. Foster huddles on his father’s old army cot. The old man kept it in back for nights when he and his buddies drank too much, but now his son sleeps on it every night. The young Mr. Foster reads back issues of Life magazine and Popular Mechanics, he cooks hot dogs and cans of chili on the little camping stove, he still sleeps with Mr. Bear beside his head on the pillow. He can hear the voices on the porch, the bursts of laughter, the laconic silences. His heart aches. His father’s friends make him nervous. They always have. They remind him of boys from his youth, boys in search of social capital to spend. Athletes and stoners, boys who would knock his books out of his arms, boys who hit him in the face with basketballs. Not that he has seen any of these men act that way. They have always been friendly with him. Mr. Stevens used to ruffle his

hair and call him ‘sport,’ back when he was ten and Mr. Stevens was thirty-five or so. Still, Mr. Foster knows that a man is one thing; a group of men is another thing altogether. You can’t know what will happen.

Loneliness is terrible company, however. Some days, the young Mr. Foster – who is now in his fifties – will gather his courage and venture out to the porch, lean in the doorway, listen to the old men bullshit each other. They tell unbelievable tales about the men no longer here, the ones who have died or moved away. Once in a while, the stories are about the old Mr. Foster, and these are his son’s favorites, for the glimpses they give of the man he never understood, who never understood him.

“Seth!” Hank Fulton greets him as he approaches the doorframe and leans. “You’ll appreciate this story.”

Mr. Fulton is sitting on an overturned bucket, rolling a cigarette between thick, calloused fingers. Mr. Hughes is sitting on a plastic cooler, shaving bark off a stick with his pocketknife. Mr. Stevens is standing with his foot up on a stack of feedbags. There are some other men, too, but the sun is in Seth’s eyes and he can’t see them.

Hank licks the paper on his cigarette and begins his tale. “One night, me and Horatio – you all remember Horatio, right? Horatio Jackson? Well, one night, me and Horatio are out drinking at The Wheel, and Glen – your dad, Seth – Glen comes in all riled up. Oh, was he mad. He comes right up to Horatio and says, ‘What the hell did you do?’

“Horatio says, ‘Why, Glen, whatever do you mean?’

“Glen grabs him by the collar and says, ‘Listen here, you little punkass, what the hell is in my store?’

Mr. Fulton licks the cigarette paper and plucks stray pieces of tobacco off his tongue before continuing. “You all remember how Horatio and Glen used to harass each other? Seth, they were a pair, do you remember that? Horatio was the master of the practical joke and Glen just had to give as good as he got. So Glen says to Horatio, ‘You’re coming with me, and you’re getting whatever-the-hell-it-is OUT of my store.’”

Mr. Fulton lights his cigarette. Mr. Hughes stands and opens the cooler, passing out beers. Someone hands a beer to Seth, who hasn’t had a drink

in company for years. He opens the can, takes a swallow. He vaguely recalls Horatio Jackson, remembers his dad referring to him more than once as “Horatio Jackass.” Mr. Fulton opens his own beer, sips, sets the can on the porch between his feet. Taking another drag from the cigarette, he sits up straight, stretches his back and continues.

“Horatio still pretends he doesn’t know what’s up. ‘Fine, Glen,’ he says, ‘let’s go see what wandered into your store.’

“‘Don’t bullshit a bullshitter,’ Glen says, and we all climb into his truck for the ride out here. Glen has a flask of whiskey on the front seat, so we pass the flask on the way. We just shoot the shit, how’s Louisa, how’s the kids, guess who I saw at the post office, like that. Like Glen isn’t furious, like Horatio isn’t laughing inside.

“And when we get out here and we’re standing on the porch, we hear something squealing inside and scrabbling on the floor, like it’s got talons or claws or something.

“Glen is so pissed, he gives Horatio a little push toward the door, saying, ‘You get in there and get that thing out of there.’” Mr. Fulton takes a

drag on his cigarette, adding, “You remember that voice.”

This is familiar to Seth, this story of his father’s anger, the physical power, the sternness even with his friends. Seth spent his childhood following his father wherever he could, but cowering when his father noticed he was there.

“‘Glen, you’ve got this all wrong,’ Horatio starts to say, but Glen just points at him.” Mr. Fulton thrusts his own thick finger toward the cluster of men. “Glen just points at him, and Horatio knows that there is no use arguing, so he takes a breath and walks up and opens that door. And Glen shoves him into the store just a little, so he can’t turn and run. And as he steps inside, a bucket full of water falls off the top of the doorframe and pours square on his head. And Glen starts laughing and staggering around on the porch. And I’m laughing. And Horatio is laughing hardest of all of us. And Glen says, ‘Now that was fun.’”

Startled, Seth stares at Mr. Fulton. He tries to see it, his father setting a bucket full of water above the door, his father faking outrage, his father staggering on the porch laughing, his father having fun. Trace memories

from when he was very little rise in his mind, his mother and father laughing together in the car, in the kitchen.

“Turns out, Horatio set a greased piglet loose in the store, but Glen heard it running around before coming inside. Somehow Glen caught it and leashed it near the front door, where it would be noisiest. Then he set up the water over the door and came and got us at The Wheel.”

Mr. Fulton stubs out his cigarette on his shoe, pulls an Altoids tin from his pocket and tucks the butt in it. He holds the tin up. “My granddaughter is a real environmentalist,” he says. “She told me, ‘If you won’t quit smoking, Papa, at least quit littering.’ Gave me this for Christmas.” Tucking the tin back in his pocket, he looks at Seth and says, “Your old man was one of a kind.”

There is a shuddering in the ground. As it swells, the men brace themselves. Seth pushes his feet down a little harder, gripping the doorframe. Mr. Stevens puts his right foot on the porch beside his left and all the men hunch their bodies against the force of the wind as the train thunders past. Mr. Fulton checks his watch. “Last one of the day!” he hollers over the din.

Seth is thinking about his parents. When his mother died, it was near Christmas and Seth was in second grade. It was dark, and the streets were full of twinkling lights, and it was so pretty and everyone was so happy, and Seth and his father were in a waiting room at the hospital. Someone came and spoke to his father very quietly, and someone else brought Seth cookies and juice and a blanket. His father left the room for a long time, and when he came back, he looked wrong. He looked broken and wrinkled and wet. He held Seth’s hand and they went home, and his father put him to bed. In the morning, Seth came into the kitchen and found his father asleep at the table. “Where’s mom?” he said.

His father awoke with a bleary, frightened look on his face, reached across the table, took Seth’s hand. “Where’s mom?” Seth asked him again. “How come she didn’t come home?”

His dad sat up straighter at the table, rubbed his face, then pulled Seth around the table to him. In the living room, the Christmas tree waited for its big day just around the corner. “Your mom can’t come home,” Seth’s dad told him. “I’m sorry.”

“Why not? When can she come?”

“She can’t ever come home. She…” Seth’s dad blinked, rubbed his face. They were not a religious family, and Seth now realizes that his father had no way to explain death to him. Which illuminates what he said next. “She had to go be with Santa. He needed her help.”

“Santa took her?” Seth didn’t even know Santa had that kind of power, to take people. “Why did he take her? She’s not even an elf!”

“Mrs. Claus doesn’t know how to cook. The elves were starving. She went to help in the kitchen. But she loves you so much, Sethie. She told me to tell you. When Santa is watching to see if you’re naughty or nice, your mom will be watching with him.” He wiped his eyes. “Let’s make some breakfast,” he said. “What do you think Mom is making the elves?”

But Seth wasn’t hungry. He went to school angry and in class, when they made construction paper Santas, he tore his up. “I hate Santa,” he told the other kids. “He stole my mom.”

“Santa’s not real,” one kid told him.

“Yes, he is too real!” Seth shouted.

“He stole my mom!” He crumpled the other boy’s Santa, threw a pair of scissors, and ended up crying in the teacher’s arms.

The train has finished its torrential pass; the evening sighs its relief. Leaning in the doorway of Nutrena Feeds, Seth feels truly orphaned. How he aches to see his mother, her long hair and denim shorts, picking cherry tomatoes off her plant on the porch and popping them happily into her mouth. He even misses his father, longs to sit with him at the table and talk about that Christmastime, about Santa and his father’s obvious floundering pain. He wants to know the man who traded practical jokes with his buddy, wants to understand the strictness and anguish and twinkling eye. But it is too late. These men on the porch are the closest thing he has now to a family. He feels the urge to step out there with them and find a place to sit, but he can’t bring himself to do it. Still, when Mr. Hughes stands up to pass out more beers, Seth accepts one.

Ready the Kitchen

Diana Turner

experiment #5

Mark Logan

Art Student Contest Winner: 2nd Place

The Wait A.E. Williams

the wind carries the stormtorn air on its feathered back it smells like wild rain

there is a black bowl above the plate of the valley to the west a burning river of blood and oranges to the south the flagrant shards of violent electricity

the ocotillos spread the fuscia gloved fingers of their hands black arms of branches

waving the evening storm forward

Spatial Pink J Vega

of Time

Vernice Garcia

Art Student Contest Winner: 3rd Place

Biographies

Andrew Belcher is a DMA major who is attempting to enter the film industry afte r graduation. He hopes to pursue Cinematography or C.G.I.

Stephen F. Bonnet studies ceramics at Cochise Community College in Sierra Vista. He takes his inspiration from the natural world.

Terrie Cervantes has done clay sculpture since 1998 and is known for their pudgy fun horses. This last year Terrie wanted a challenge by creating animals other than horses and started with African animals, in this case the giraffe. The markings are hand drawn on piece and painted with three coats of glaze. Terrie use the contrast of glossy glaze and leaving raw naked clay.

Melina Christopher has always loved everything to do with art and expression and is currently finishing up a degree at Cochise College in Digital Me dia Arts. Melina also has a job in the graphic design field. Melina writes poetry, draws, an d takes photos, and hopes to use these forms of expression in their career in some way. She wants to share the beauty she finds in the world, whether that be through words, images, or li nes etched into a page.

Kat Coppes is a mixed-media artist based in Douglas, Arizona. They are currently pursuing a Fine Arts Associates with plans to pursue a Bachelor’s at the University of Arizona. Their works explore numerous themes but focus on representation in gender and sexuality, and the experiences of poverty and living next to the border. Some of their most recent art works were featured in the 2024 Student Art Exhibition, and their collaborations with the 2024 Pit Fire 3D Sculptures and Ceramics department.

Luis Cornejo hates third person perspectives when describing himself. He is a Digital Media Arts major, and works in many mediums. He is finishing this desc ription with this sentence.

Alice Duffy-LaBonte reignited her passion for drawing by enrolling in drawing classes at Cochise College. Her art has won first place at the 2024 Tombsto ne Art Show. She is also an avid quilter and enjoys living in Hereford, Arizona with her husband, Tom.

Emmaline Fisher spent her most formative years growing up in Utah but has recently become a student at Cochise College where she is pursuing a degree in English. She has

practiced creative writing for many years, during which time she has developed a strong voice and writing style. She hopes to one day publish a collection of her work and is honored to have the opportunity to share her work with a wider audience.

Dani Foti has lived in Bisbee for just a few years after moving from New York. She is inspired by vintage science fiction art and collage, and gives this style her own surreal, digital twist.

Vernice Garcia is an artist based in Douglas, Arizona and is currently pursuing an Associate of Fine Arts degree at Cochise College. Her work delves into themes of surrealism, body autonomy, gender, multiple mediums, portraiture, and astronomy. She has recently exhibited her work at the Cochise College Pit Fire Festival (20 24), the Cochise College Annual Student Exhibition (2024), and the University of Arizona Art of Planetary Science (2023).

Gerry Gabel has been some places, done some things.

Joyce Genske fell in love with photography at a very young age and has been taking pictures since, finding new ways to depict things, learning new technology, and accepting new challenges. She enjoys capturing things other people miss and showing them the world through her eyes.

Alejandra J. Gutierrez-Tapia is an artist living in Douglas, Arizona but has roots in Agua Prieta, Sonora. Currently she is working on earning her Digital Media Arts Associate’s degree at Cochise College. She is hoping to pursue a career as a tattoo artist when she graduates! The artworks she creates center on themes of alternative styles, horror, social anxiety, melancholy, spirituality, hispanic culture, human connection to nature, and comfort. She specializes in mixed media projects which include watercolor, nk, digital art, film, and photography. She has won awards at the Cochise County Fair art competition twice in a row and was part of an exhibition at the Douglas Campus, Union Gallery called; Community and Identity 2024.

LaDona Hoornstra is new to photography, a way to cope with extreme changes in life.

Vanessa Inzunza went to the Benson Lantern show to capture her photo.

Anita Johnstun is retired from Cochise College and a novice artist. Her interest in art came late in life. A wife, mother of two, and grandmother of two keeps her busy and drawing is a way to express a new found creativity.

Sean Kelly is a member of the Cochise community who lives and works on Douglas campus. They are working on their General Studies degree and will be transferring to ASU in the fall to pursue a Bachelors of Animation. They like to explore the concept of color and contrast in their work as well as taking a whimsical view of the world. They have been working as a Resident Assistant for the last year and a half and have partcipated in the Student Exhibition in the Spring of 2024. In addition, they have participated in the Bisbee Plein Air Festival 2023.

Mark Logan is a Cochise College student on the Douglas campus.

Elric Mahoney created a charcoal piece that is a reflection of who he is as a person, presenting items embodying his past, present, and future aspirations. In addition, he represents what drives his success with a military rank patch provided by his wife and a corrective helmet that was once used to treat a medical condition for his son. Due to his experience with using charcoal for the first time, he has fallen in love with the medium.

Victor Marrujo is a 25-year-old international student attending Cochise College. This past year was the first time in a long time that Victor seriously tac kled art. He had previously taken it only as a hobby, but after being immersed in the environment alongside his peers, it reawakened a passion inside of him that he had long forgotten about.

Grace Megnet is currently studying ceramics at Cochise College in Sierra Vista. She holds an MFA in painting. She is a textile artist and a member of the Subway Gallery in Bisbee.

Dale Miller creates art in multiple mediums. They enjoy exploring play, spontaneity, mark making, and highlighting the natural properties of the medium being used. Art is what you make of it.

Ho Milosevic has attended Cochise College for over 20 years.

Juan Noriega used an image from an assignment from one of his photography classes. It

shows his subject in a darker theme, as if she were behind bars. To achieve this look, he found a broken chair in his garage and asked his subject to hold the chair in the most stable and comfortable way possible to them.

Kevin O’Brien is retired from Cochise College. He taught writing, introduction to literature, American literature and co-taught the Honors seminar Quest for Utopia while mentoring many students in a variety of Honors projects. As well as writing, he is studying blues harmonica and exploring photography. Now as a full time cat daddy he is enjoying retirement with his wife.

Estefania Ramirez-Toscano is an artist living in Agua Prieta, Sonora. She is working on her Associate of Arts at Cochise College with an emphasis in 2-Dimensional Art and will transfer to ASU in Spring 2026 to pursue their Bachelor of Arts with a concentration in Animation. Their work explores themes such as life in the borderlands and landscapes in the 2D world, represented in mediums such as graphite, charcoal and ink. A few recent exhibitions they have been in include: the 2024 Cochise College Student Exhibition, Songs from the Borderlands Contest Cochise College and Central School Project in Bisbee, and the Community & Identity Exhibition at Cochise College.

Makayla Rios’ photography is a portrayal of inner voices taking over the mind and body.

Maebeleine Salminen brought life into something she felt her soul could touch with each stroke of a pencil. She often daydreams about the moon and stars, so to have inserted something she loves into an art piece brings her joy.

Luke Serna ’s piece demonstrates hwo flow and chaos represent the balance b etween harmony and unpredictablity, driving creativity and transformation in both nature and human experience. Together, they form a dynamic interplay, illustrating how order and disorder coexist to shape the complexity of existence.

Karl Sullivan is inspired by his experience as a child in Florida, where he became interested in art by watching cartoons such as S pongebob Squarepants . Over time, he began to dabble in art and realized this was his true passion as a career. He hopes to be a talented artist working at studios or independently.

Bruno Talerico uses poetry to express feelings and ‘think out loud.’ He started writing poetry in 2009 as therapy for PTSD, and over time, therapy evolved into an addiction to wordplay. Inspiration comes from paying attention to nature and the little voice inside. He writes haiku/senryu every morning. Most of his work is free verse although occasionally he likes to explore other forms. Bruno lives with Matisse The Cat on four acres in the grasslands of southern Arizona.

Diana Turner was born in Phoenix, Arizona more than 60 years ago. She retired and began taking classes for self-fulfillment. She stumbled into art.

Monique Vargas decided to pursue her passion for photography after dog training for 15 years and is currently attending Cochise College for Digital Media. Being a dog trainer has naturally led to the world of pet photography. “Clyde” is a photo that was taken of a Wired Hair Pointing Griffon mid run and he looks as happy as can be. “The Little Werewolf” was captured while out walking with a friend and her dog. The lighting, light breeze, and the dogs’ willingness to stand still on a 6ft railroad tie allowed for the perfect photo moment.

J Vega is a mixed media artist currently studying at the Cochise College Douglas campus, hoping to become a professional filmmaker in the animation indus try. In 2024, J was chosen as a BAC fellow, as well as having their work displayed at multiple venues like the Cochise College Annual Student Show and the Binational Art Walk in Douglas. J’s work focuses on the beauty, talent, and pride of being from a border community like Douglas and Agua Prieta.

A.E. Williams is the recipient of The Academy of American Poets Award, The Audre Lorde Award, and The Mary M. Fay Award. She won her first Slam at the Nuyorican Poets Café, and continued Slamming throughout the 90’s. She was the first pe rson allowed to publish Amiri Baraka’s “Somebody Blew Up America,” who once told her that her grandfather is the reason he became a poet. She studied with Meena Alexander and William Pitt Root, among others.