The handbook of Greek CoinaGe SerieS, Volume 8

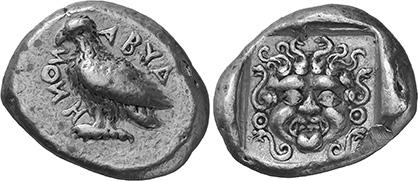

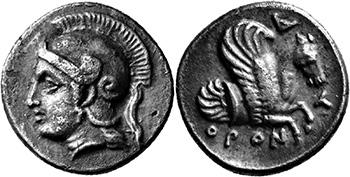

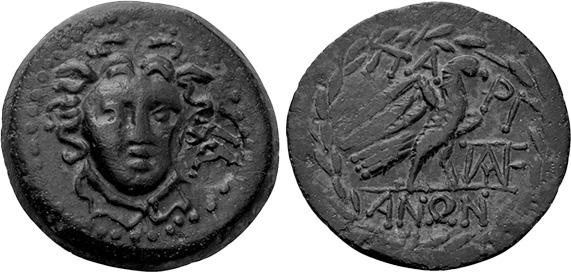

Coins of Western and southern anatolia

Part 1: Mysia and troas

sixth to first Centuries BC

By Oliver D. Hoover

With a Series Preface by D.Scott VanHorn and Bradley R. Nelson

The handbook of Greek CoinaGe SerieS, Volume 8

Handbook of Coins of Western and soutHern anatolia

ParT 1: mySia and TroaS

Sixth to First Centuries BC

By Oliver D. Hoover

With a Series Preface by D. Scott VanHorn and Bradley R. Nelson

Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. Lancaster/London/The Hague

Copyright © 2025 Oliver D. Hoover

All rights reserved. Written permission must be secured from the publisher to use or reproduce any part of this book, except for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles.

Published by Classical Numismatic Group, Inc., Lancaster, Pennsylvania, London, England, and The Hague, Netherlands.

Library of Congress Control Number 2023922098

ISBN 978-1-7355697-7-2

Printed in the United States of America

PREFACE TO The Handbook of Greek Coinage Series

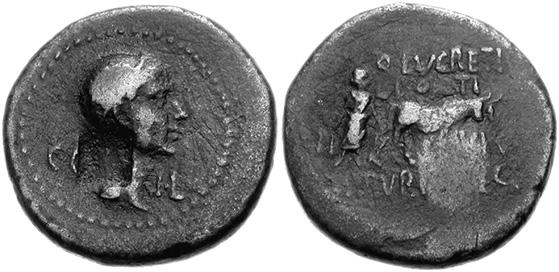

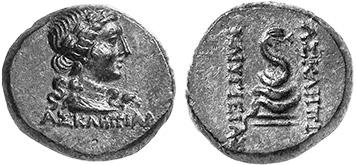

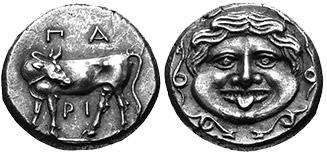

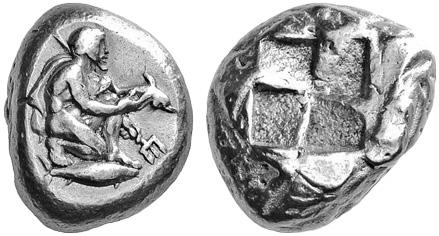

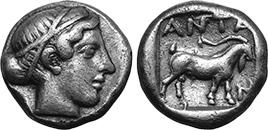

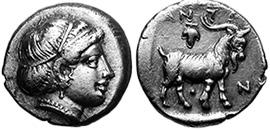

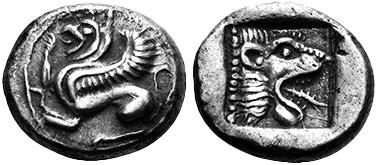

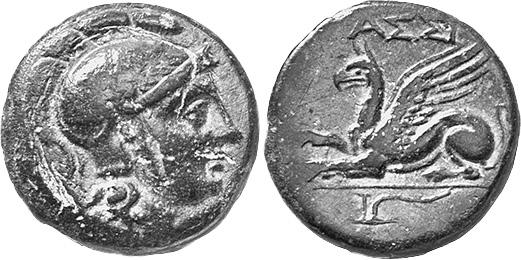

D. Scott VanHorn and Bradley R. Nelson (all coins illustrated in this section are courtesy of Classical Numismatic Group, Inc.)

More than three decades have passed since David Sear published Greek Coins & Their Values, his revision of Gilbert Askew’s A Catalogue of Greek Coins published by B. A. Seaby in 1951. Since then, the field of ancient numismatics and the hobby of collecting ancient coins have changed so much that now Greek Coins & Their Values would require a complete revision to include all of the most current numismatic information available, list the many new types and varieties unknown to Sear, and determine an approximate sense of rarity for all of these issues. In order to encompass this new material and create a viable reference for the beginning and specialized collector, such a handbook would have to be more than the two volumes which Sear found necessary. As a result, Classical Numismatic Group is publishing The Handbook of Greek Coinage Series, written by Oliver D. Hoover, in a series of 13 volumes, each covering a specified area of Greek coinage, with the first being The Handbook of Syrian Coins: Royal and Civic Issues, Fourth to First Centuries BC (Volume 9 in the series). This series is designed to aid the user in the quick, accurate, and relatively painless identification of Greek coins, while providing a cross-reference for each entry to a major work, which will allow the inquirer to pursue more in-depth research on the subject. The subject-matter of each volume is arranged chronologically for royal issues, and regionally for the civic issues; within each region, cities are listed directionally, depending on the region. For those rulers or cities that issued coins concurrently in all three metals, these issues will be arranged in the catalog with gold first, followed by silver, and then bronze; each metal is arranged by denomination, largest to smallest. Known mints for the royal coinage are listed below the appropriate type, making an easy search for a specific mint. Each entry will include a rarity rating based on the frequency with which they appear in publications, public and private collections, the market, and/or are estimated to exist in public or private hands. No valuations are listed, since such values are generally out of date by the time of publication. An online valuation guide at www.greekcoinvalues.com will allow interested individuals the opportunity to gauge the market and reduce the need for repeated updates of this series. Whether one purchases the entire set for their reference library, or the individual volume pertaining to one’s area of specialization, The Handbook of Greek Coinage Series should provide a useful staging-point from which collectors and interested scholars can pursue their research and interests.

COLLECTING GREEK COINS

There is a distinction to be drawn between true collectors and accumulators. Collectors are discriminating; accumulators act at random.

Russell Lynes, Life in the Slow Lane

Traditionally, the collecting of ancient coins and, in particular, ancient Greek coins, has been viewed by some as a pursuit only of the nobility, or the very wealthy, because all ancient coins must be very rare and expensive to acquire. While this is somewhat true – with specimens of great rarity or superb quality of preservation commanding record prices – it is still possible for the dedicated and

knowledgeable (that is the key!) collector of more modest means to assemble a collection that will not only provide the collector with enjoyment, but also help to expand the field of numismatic knowledge. Some collectors of Greek coins do so primarily for the aesthetic value and rarity these coins offer – works of ancient art in miniature, such as the signed dekadrachms of Syracuse, or the gold oktadrachms of Arsinoë II, the wife of Ptolemy II. Others collect for the historical and social associations these coins might provide – such as the coinage of the Archaic period, a stater of the famed Boiotian commander, Epaminondas, or the smaller silver denominations and bronze coins used by the man and woman on the street. Many collectors, however, are attracted by both aspects, and fall somewhere in-between.

The discovery of many hoards of ancient coins over the past thirty years has contributed a great deal to collecting by making many more coins accessible to collectors of all interests and financial means. The reason for these hoards is clear: prior to the development of savings banks, individuals buried their savings in secret, very often in the surrounding countryside, as a precaution against theft by robbers or invading armies, hoping to return to them once things had quieted down. This was especially true of the armies themselves as they fought with one another back and forth across the Greco-Roman world. These hoards have brought to light a number of heretofore unknown types and varieties, which have greatly expanded the field of numismatic knowledge. At the same time, the discovery of these hoards has created a number of difficulties for collecting ancient coins. In some instances, these hoards have been dispersed before their contents could be recorded. The laws in some “source” countries, which often claim ownership of all archaeological objects and penalize finders and collectors, have discouraged the reporting of finds and have stifled the traditional cooperation among academics, dealers, and collectors. Sometimes the search for these hoards has resulted in the damage of archaeological sites, and today some members of the archaeological community actively try to impose severe restrictions on the trade of ancient coins, with their ultimate goal being the total elimination of private ownership of ancient coins. Perhaps more troubling, the desire for ancient coins has fueled a thriving market for the production and distribution of forgeries. While many of these forgeries are simple casts or complete fabrications that are easily detectable, modern techniques, such as high pressure casting or the use of transfer dies on ancient flans, have proven more deceptive, even deceiving numismatic experts.

With the presence of forgeries in the market, the phrase caveat emptor has become more important than ever. Collectors can protect themselves by seeking out knowledgeable and reliable dealers, who will insure the authenticity of the coins they sell, and accept the return of purchases expertly determined to be forgeries. Collectors should also add to their own knowledge by building up a personal numismatic reference library, or joining one of the international numismatic societies connected with their area of interest. Not only will doing so add to one’s enjoyment of collecting, but it will also help protect one’s investment by assisting in the detection of forgeries and the determination of the coin’s provenance. Coins that heve been offered in past auctions, or are from important public or private collections, typically possess a secure pedigree, establishing a long-lived existence for the coin in the marketplace. A pedigree also helps in determining authenticity, especially of coins formerly in public collections, like the British Museum or the Hermitage, that have been offered in the past for sale. At the same time, verifying such a pedigree can reveal whether a coin may actually be a forgery of one still

in the collection, or stolen from it. Finally, a pedigree connects the current owner to his predecessor, or predecessors, thereby linking them in the great chain of caretakers helping to preserve our cultural heritage for future generations of numismatists and collectors.

Inevitably, the collector of ancient coins must deal with the subject of grading. Unlike US numismatics, where consistency has allowed for a standardized 70 point system, the grading of ancient coins is somewhat more complicated, owing to the methods of ancient coin production. The basic grades commonly used for ancient coins are, in order from best to worst:

Table 1. Table of Recognized Standard Coin Grades (non-US coins)

Grade English German French Italian

FDC Mint State

EF Extremely Fine

VF Very Fine

Stempelglanz Fleur de Coin Fior di Conio

Vorzüglich

Sehr Schön

Superbe Splendido

Très Beau Bellissimo

F Fine Schön Beau Molto Bello

G Good Sehr Gut Erhalten Très Bien Conservé Bello

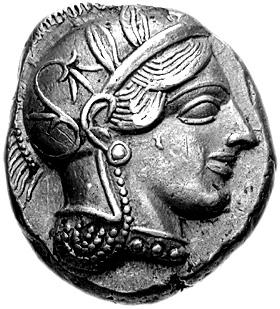

The grades listed in this table represent the ideal for that grade. Dealers, however, will include qualifiers to describe a coin that lies outside that ideal. The two most common qualifiers are “near,” as in “Near EF,” and “good”, as in “Good VF.” Two others that appear are “choice” and “superb,” both of which are subjective terms, expressing the exemplary state of a coin compared to others like it in similar grade. Thus, a coin graded Choice EF or Superb EF indicates its quality is better than other similar coins graded EF. Below are examples of a common Athenian Tetradrachm at each of the basic grade levels:

Two factors influence the grading of ancient coins: the general effects of wear, and the effects of manufacture. The effects of wear are due to circulation, find conditions, and conservation. These effects include a loss of sharpness, corrosion, areas of accretion, and scratches. The degree to which a coin is affected by wear is the primary factor in determining a coin’s grade. The effects of manufacture – issues of centering, quality of strike, as well as multiple strikings – do affect a

coin’s overall aesthetics, and thereby its value, but typically do not affect the grade. Consequently, a coin’s grade is typically supplemented with information noting such detrimental factors resulting from the coin’s manufacture. For example, a coin that is in exceptional condition, but has been struck a bit off-center may be graded as “EF, slightly off-center strike.” Another factor to be considered is the state of the dies used in the production of the coin. The dies of some series of ancient and medieval coins exhibit a refined execution, exemplified by highly artistic specimens. The dies of other series may appear somewhat less refined, in which case, such a coin may appear to be in a lower grade than it actually is. When this occurs, the grade is accompanied by the phrase “for issue.” Finally, the flan itself is another factor that must be considered. As with the dies, flans are prepared by hand and are susceptible to flaws during manufacture. Common flaws are irregularities in the shape of the flan, impurities in the surface, and preparatory marks (such as file marks).

Toning on gold or silver coins, or patina on bronze coins, result from a chemical reaction between the coin’s surface and the surrounding air or soil in which it was deposited. They do not effect a coin’s grade, but may influence the aesthetic value of the coin to a particular collector. For example, an attractively toned silver coin in VF condition may be more appealing to an individual over untoned examples in EF. Similarly, a bronze coin in VF condition with an attractive even apple green patina may be more appealing than an EF example with a mottled patina of various colors.

While the collector can readily distinguish a dealer’s criteria for determining a coin’s grade, it ultimately falls to individual collectors themselves to develop their own sense of aesthetics – of what is most pleasing to them – when determining what coins to add to their collection.

Specialized References

For specialized books and articles, the collector is encouraged to explore both the online bibliography and book list of Classical Numismatic Group, at www. cngcoins.com, or the library and collections databases of the American Numismatic Society, at www.numismatics.org.

Below are some useful general links for the collector:

The American Numismatic Association (www.money.org)

The American Numismatic Society (www.numismatics.org)

Ancient Greek Coins of Miletus (rjohara.net/coins/)

Asia Minor Coins (www.asiaminorcoins.com)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Collections Search (www.mfa.org/collections/ search_art.asp)

CoinArchives (www.coinarchives.com)

Digital Library Numis (members.ziggo.nl/tverspag/NUMIS/)

Fitzwilliam Museum Coins and Medals Homepage (www-cm.fitzmuseum.cam. ac.uk/coins/)

IAPN-AINP (www.iapn-coins.org)

Magna Graecia Coins (www.magnagraecia.nl/coins/index.html)

The Silver Facing Head Coins of Larissa (www.lightfigures.com/numismat/ larissa/index.php)

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin Münzkabinett (www.smb.museum/ikmk/)

Sylloge Nummorum Graecorum (www.sylloge-nummorum-graecorum.org) WildWinds (www.wildwinds.com)

THE TECHNOLOGY OF ANCIENT COIN PRODUCTION

Unlike modern coins, every ancient coin is an individual product, by virtue of its manufacture. Every part of the process was done by hand and could be affected by a number of variables, from the execution of the dies, to the metal quality of the flan, and the actual striking of the coin. As a result, examples of the same issue, or even the same die pair, can exhibit a number of differences. The striking process comprised placing a flan of a specific weight and metal between two dies, usually set within an anvil and punch, and applying sufficient pressure to fill the voids of the die with the metal and thus stamping the flan with the intended design. The anvil die typically formed the obverse (front) of the coin, and the punch die the reverse (back); these are more conventionally refered to as the obverse die and reverse die, respectively. From this process, a coin of a specific value was produced to facilitate a number of economic transactions.

The Flan

The flan is the metal blank upon which the design of the die is imprinted to produce a coin. Precious metal coins (electrum, gold, and silver) are said to be struck al pezzo (It. “to the weight”). Other coins, such as some later bronze issues, fall within a range of acceptable weights. These coins are struck al marco (It. “to the mark”), and function as fiat currency. While the actual production of flans varied, they were made generally by pouring molten metal into a mold; many ancient coins

extant today still show traces of this casting process. Sometimes flans were cast in strips of round blanks connected by a narrow bridge, or sprue. These strips would be heated, each blank on the strip would be struck, and then the coins would be separated by removing the sprues. This production technique is particularly visible on certain issues of Magna Graecia, Sicily, Judaea, and Egypt under the Romans. Flans were also cast in particular shapes. Some bronze coins have beveled or serrated edges, and various hammering, grinding, and polishing techniques were also used to prepare the flan. The grinding and polishing marks, visible on these finished coins, are known as adjustment marks. Previously circulating coins could be reused as ready made flans for a subsequent issue, which is called an overstrike; the previous issue is called an undertype. Often, as in the case of the silver zuzim of Bar Kochba, which were overstruck on circulating Roman denarii and drachs, traces of the undertype remain, providing valuable evidence for patterns of coin circulation as well as for establishing relative chronology, especially for undated issues.

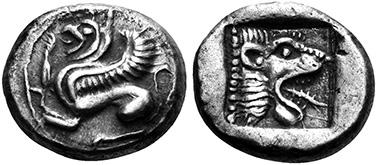

The Die and the Aesthetics of Coin Design

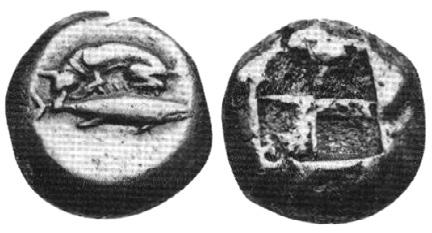

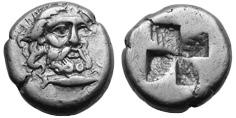

The earliest coins of Asia Minor may have consisted of a flan marked with a single square incuse on the reverse. Formed by a reverse die of rough and irregular pattern, this incuse was possibly meant to confirm that the flan was composed of solid precious metal, rather than a fourrée, a flan comprising a precious metal veneer alloyed to a base metal core. While some of these coins are simply blank on the obverse, many have regular or irregular patterns of lines, which may have been scratched into the obverse die in order to keep the flan from moving during striking. Soon, complex designs and images, carved in intaglio, or in reverse to the way the image was supposed to appear, were incorporated into the obverse die, which, upon striking, would produce a raised design on the surface of the flan. Such designs are known as types, and were possibly the first means of identifying the issuing authority. While some states, like Persia, continued to employ traditional rough, irregular quadrate punches for some time, others incorporated designs to the reverse die to produce images on the reverse of their coins. These reverse designs were usually also engraved in intaglio, as on the obverse die, but some cities, such as those in Magna Graecia, engraved them in relief, in order to produce a design that would be in incuse on the reverse of the flan. Dies were sometimes made of iron, but bronze, which is much softer and easier to engrave, became the material regularly used in the production of dies.

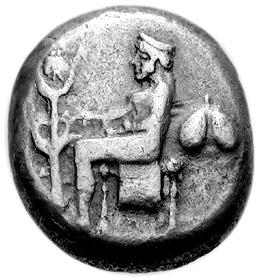

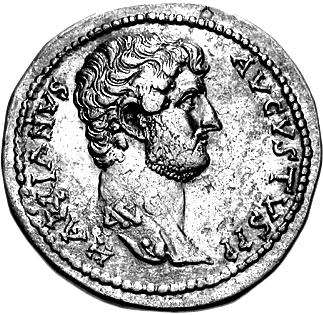

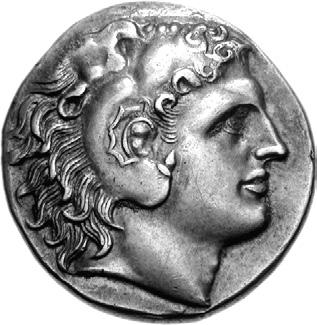

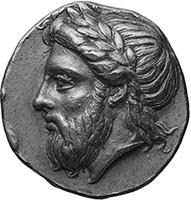

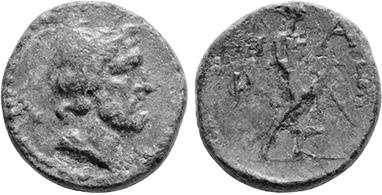

Late classical tetradrachm of Pixodaros, satrap of Karia

A die’s design has much to do with its success in producing a beautiful coin, but one must also take into consideration the technical aspects of coin production to appreciate a coin’s aesthetic value. The transfer of an image from the die to a flan not only requires a great deal of force, but the proper and even distribution of

that force is also important to the image as well as the life of the die. If the force is uneven, metal will not flow properly into the detail areas of the die, and the resulting stress will hasten the die’s fragmentation and eventual disintegration. This process can be seen sometimes on a coin’s surface where lines or deposits of extraneous metal fill voids in a disintegrating die.

As the obverse die of a Greek coin was often in very high relief, a large amount of metal was required to fill its center. This was particularly so on the larger denominations which allowed master engravers free range to express classical aesthetic ideals. It is for this reason that the obverse die was placed on the anvil. By design, the highest point of relief was at the center of the obverse, where the maximum amount of metal would flow when the flan was struck by the punch, while the lowest relief was at the center of the reverse. To enhance the flow of the metal during striking, dies eventually evolved from having simple flat surfaces to slightly curved surfaces, with the obverse die becoming concave and the reverse die convex.

Die Axis

For some mints, the alignment of obverse and reverse dies seemed to be of minimal importance. In the ancient world, however, maintaining a regular die axis, or the axial relationship between the obverse and reverse dies, seemed to be one way of maintaining a level of mint control; modern numismatists use the study of die axes to aid in determining the attribution and authenticity of a coin. Dies were initially aligned by hand, a difficult procedure when thousands of coins had to be struck at a time. Eventually, hinged dies were created, which kept the obverse and reverse dies in perfect alignment for every strike.

Die Wear, Rusty Dies, Recut Dies, and Die-Links

Obviously, the process of striking coins put an enormous amount of stress on the dies, which would deteriorate throughout the process. Over time, a die could develop flaws, such as die breaks, that would be visible on the coins that were subsequently struck. The rate at which such flaws developed was completely random, with some dies failing at almost the first strike, while others lasted intact for a long time. Other than die breaks, the most common flaw from regular use was a loss of detail, or sharpness, of the die. Although some of these flaws required a replacement of the damaged die, some mints would contine to employ a die until it broke, or the design was completely indistinguishable. Another common flaw seen in ancient coinage is die rust. As coinage in the ancient world was generally struck

on an ad hoc basis, dies would be put aside in storage once the required amount of coins had been struck. As storage conditions were not climate controlled, the dies would often develop rust. Consequently, coins struck with these dies display areas of crystalline roughness, usually in the fine details. A common method a mint would use to lengthen the life of a die with flaws was to re-cut part or all of the die, either to hide a die break, or clarify details that had become overly worn.

The positive result of die flaws is that it makes it very easy to identify the same die used on different coins. The identification of dies is a very important aspect of numismatic research. Throughout the period of striking a particular issue, a mint would often produce new dies to replace old ones, or increase productivity. New dies would be used with older dies, creating an identifiable sequence of dies used in the production of an issue, known as die-links. By studying these dielinks, numismatists can determine much about a mint, its coin production, and the chronology of various issues. Die links are also important in establishing the authenticity of coins.

Striking the Coin: Clashed Dies, Die Shifts, Double Strikes, and Brockages

As in coin production today, sometimes errors occur during the striking process. The most common error involved incorrect centering, and many ancient coins show this fault. Another error occured when the dies were struck together without a flan present, which would cause one of the dies to imprint part, or all, of its image in the other die. Subsequent coin strikings would produce a shallow incuse of the die’s image on the opposite side of the coin. Dies affected in this way are known as clashed dies.

Occasionally, a die would move slightly during striking, or the mint worker’s strike would apply slightly lateral, as well as downward, pressure, causing a slight smearing of the image on the flan, known as a die shift. A similar error occurs when a mint worker strikes a flan twice. In such cases, the flan may move between the strikes, causing the image to be imprinted multiple times on one or both sides of the coin. This is known as a double strike. Depending on the movement of the flan, a double striking may be slightly noticeable, or quite apparent, and can be confused with a die shift (or vice-versa). Although less common, some coins are struck more than two times, and are called by the appropriate name, triple-, quadruple-, etc., strike. A rare variety of these errors is the flip-over double (or more) strike, where the flan flips over before it is struck again. In such a case, each side of the coin will have both obverse and reverse images present.

Sometimes a struck flan remained lodged in either the obverse or reverse die, and was not removed before another flan was placed for striking. When this happened, the lodged flan acted as a surrogate die, and when the hammer fell again, the new flan would have the image of the unobstructed die on one side, and the incuse of the same image (caused by the stuck flan) on the opposite side. This effect is known as a brockage.

Life after Striking: Countermarks, Banker’s Marks, Graffiti, and Cut Coins

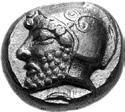

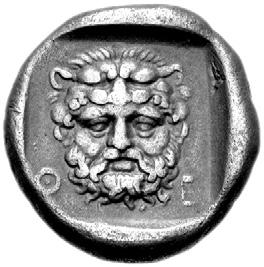

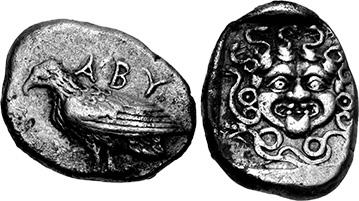

Countermarked Elis stater

Periodically, mints would need to re-tariff existing coins, or accept foreign currency as official or emergency issues. This was accomplished through the application of countermarks. Countermarks could be either letters, combinations of letters, monograms, or images of various sorts, punched into the obverse or reverse. Other marks found on coins are banker’s marks. Banker’s marks first appear on some of the earliest electrum coins. They are usually tiny incuse punch marks of varying type, usually a simple symbol such as a crescent, serving as assayer’s marks. It is sometimes difficult, or impossible, to discern whether a particular mark is a countermark or banker’s mark.

Probably the most rudimentary type of marking found on coins is the graffito. Graffito is the scratching of letters on a coin for some religious or secular purpose. Most often a graffito takes the form of a single letter, but can also be found as a partial or whole word. If there is only one occurrence of this on a particular coin, it is known as a graffito. Multiple occurrences of graffito on a single coin are known as graffiti.

During the shortage of specific fractional denominations, large denomination coins would be cut into smaller segments (usually a half or quarter) in order to make small change. One notable example of such a cut coin is a half of an extremely rare Athenian dekadrachm, most likely done in commerce as a matter of necessity.

THE ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF GREEK COINAGE

Before the introduction of a regular system of coinage, early societies relied on a system of barter for material goods and a system of mutual obligation for military service. While such an arrangement may have sufficed for smaller societies, it soon became evident that such a system was inefficient for more complex transactions between states, and it became necessary to employ some other medium of exchange. Where supplies of naturally-occurring and easily-obtainable sources of precious metals, such as copper, silver, gold, and electrum, were readily available,

these soon became the recognized medium of exchange, and, over time, replaced the barter-system for large-scale, international transactions. The advantages of using precious metals were multi-fold: they possessed a broadly accepted intrinsic value, they could be stored for long periods with no detrimental physical effect (unlike bartered vegetable matter), they were generally easier to transport over long distances and at short notice, and they were simpler to use in transactions. Initially, this currency was in the form of bullion – jewelry, plate, or ingots and wire –which was transacted by weight. When necessary, these items could be transferred whole or, more often, broken up into smaller pieces as the need required. Modern scholars collectively call this broken-up bullion-currency hacksilber and consider it as perhaps the earliest form of coinage. Such currency transacted by weight was used in the Levant and Egypt until well after the introduction of coinage; Egypt, in particular, did not strike any coinage at least until the reign of the pharaoh Nektanebo II (360–343 BC).

Since transactions (including those of the pre-monetary arrangement) were valued according to a fixed ratio based on standardized units of weight, it was natural consequence that once bullion-currency became the accepted method of payment, that these valuations adopt the then-current weight system. An example of this is the shekel, one of the oldest known weight/currency units. Originally representing a measurement of grain, calculated at 180 grains of barley (approximately 11.34 g), the shekel became a standard unit of weight, and later, stood for a value of currency, since shekel payments were transacted by weight. Over time, however, as the intrinsic value of the metal fluctuated, the weight of the shekel as a unit of currency increased or decreased until eventually an accepable standard weight was reached. Likewise, the mina and the talent, which were standard units of weight and calculated as multiples of the shekel, also became values of currency. In western Asia Minor, the situation of was complicated further, because the gold/ silver ratio in electrum used for transactions there varied from place to place. The innovation of a bimetallic system, however, which replaced electrum coinage with a gold and silver stater (Gk. ἡ στατήρ = lit. “weight”), each of a specific weight and ratio between the two metals, solved the problem, creating a more stable currency system with multiple fractions, and one which other Greek poleis adopted, with local modifications.

Where and when coinage was first introduced will remain an object of scholarly debate, but all the evidence points to western Anatolia in the seventh century BC. During the preceding four-and-a-half centuries following the collapse of Mycenaean civilization, a period which scholars have called the “Greek Dark Ages,” the eastern Mediterranean underwent a broad economic, political, and social upheaval. During this period, both the Phoenicians and the Greeks expanded their influence throughout the Mediterranean and Black Sea: the Phoenicians by establishing trading outposts, particularly in Spain, Sicily, and at their newly-founded city of Kart Hadasht (Carthage); the Greeks by establishing

colonies wherever they could. At the same time, a number of smaller states, taking advantage of the power vacuum created by the diminished power of the Hittite and Egyptian Empires, and finding an ever-increasing supply of mercenaries at their disposal, used the opportunity to establish their own empires. Increasing international trade and the expansionist polices of the Anatolian successor states, particularly the kingdom of Lydia, would demand a more suitable and efficient form of coinage.

Although current research demonstrates that the blank/striated electrum coinage of Ionia may have been struck concurrently, the origin of coinage has traditionally been ascribed by later classical authors to Lydia, a kingdom which, to the Greeks, became a synonym for great wealth. If true, the reasons for the introduction of coinage in Lydia would have been two-fold. Beginning in the early seventh century BC, Lydia embarked on a program of territorial expansion in western and central Anatolia making it the nearest major power to the Greeks. Secondly, Lydia’s expansion was funded by sources of electrum, an alloy of gold and silver, located around the capital at Sardis. Initially, this naturally-occuring electrum may have been transacted in raw form, but since the the gold to silver ratio in naturallyoccurring electrum is variable, the Lydian kings purposely controlled its metal content to guarantee it would have a consistent intrinsic value (A. Ramage and P. Craddock, King Croesus’ Gold: Excavations at Sardis and the History of Gold Refining [London, 2000]). In addition, the first actual coins began to be produced by applying designs to the metal. Like the Ionian electrum pieces, the Lydian coins had a plain incuse punch on the reverse. Surprisingly, however, the Lydian coins had a raised type on the obverse, the head of a roaring lion. According to Aristotle (Politics 1.9.1275a), the purpose of a type was as a sign that the piece was of full value and reduced the need for weighing each piece, thus facilitating the transaction and acceptance of the coins. Furthermore, the issuing authority would accept such coins tendered in future payments. This addition of markings (type) was the next major step in the creation of coinage. These early electrum issues were based on a stater weight of a little over 14 g. The high intrinsic value of the metal precluded the use of these coins in daily transactions and probably represented sizeable pay for a soldier.

The second major step came with the introduction in the sixth century BC of a bimetallic system of coinage. Although the Lydians controlled the metal content of their electrum issues, some of the Ionian Greek cities issued early electrum coins of a highly variable gold content. While this was not readily detectable because copper was routinely added to maintain consistency of color, it nevertheless did affect the value of such coinage in economic transactions (K. Konuk, “The electrum coinage of Samos in the light of a recent hoard,” in Neue Forschungen zu Ionien [Bonn 2005]). To solve the problem, a system composed of issues in both gold and silver of a consistent purity and weight, and based on denominations of a specific ratio between the two metals, was created. Initially, based on a gold stater of over

10 g (the so-called “heavy” series), this standard was soon reduced to a gold stater of a little over 8 g (the so-called “light” series). Gold fractions of the stater were also issued, from the half stater (or hemistater) denomination, down to the onetwenty-fourth stater. Similarly-sized silver denominations were also introduced: a stater of over 10 g, a half stater (or siglos) of over 5 g, and smaller fractions, also down to the one-twenty-fourth stater. This new bimetallic, multidenominational system demonstrates the broad range of values now available and reveals a system created to accommodate a more monetized economy. The main disadvantage of this system was the inconvenient size of the smaller fractions, some of which seemed little larger than a grain of coarse sand; the handling of them in everyday transactions proved difficult as these smaller denominations could be lost quite easily (cf. Luke 15:8-9). The problem of smaller denominations was not solved conclusively until the fourth century BC introduction of token bronze coinage to replace the smallest silver coins. Who instituted this new system has been the subject of much research and scholarly debate. The Greek historian Herodotos (I.94.1) assigned this innovation to the Lydians, saying that “[they]…were the first men of whom we know to make use of the gold and silver currency they minted (my translation dsv)”, and by implication that it was Kroisos, the last of the Lydian kings, who did so. Others, however, have argued that it was the Persians who were more likely the ones who instituted this system, using those issues depicting a confronted lion and bull, until the time of Dareios I, when a new type, featuring the Great King, was introduced (Georges LeRider, La naissance de la monnaie. Pratiques monétaires de l’Orient ancien [Paris, 2001]). In 2005, however, the publication of two gold and one silver fractional staters, found in 2002 in the ruins of the Lydian fortifications at Sardis within a context that predates the destruction of the city by the Persians in the 540s, has reopened the debate (N. Cahill and J.H. Kroll, “New Archaic Coin Finds at Sardis,” AJA 109 [2005]).

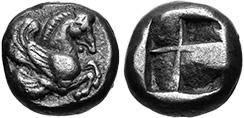

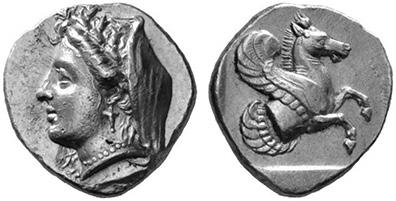

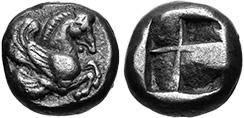

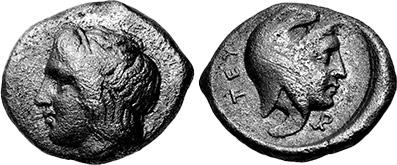

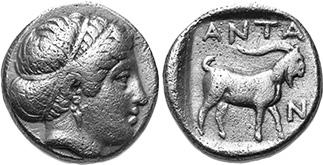

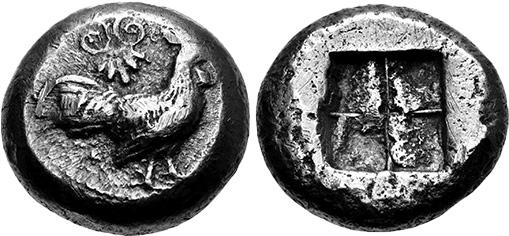

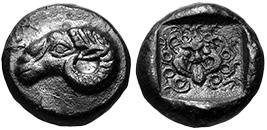

Archaic Aegina stater; Archaic Phaselis stater

Elsewhere in the Mediterranean between the seventh and the middle of the sixth centuries BC, a number of important Greek cities began to strike coinage. Some areas, like Mysia, Ionia, and the island of Lesbos, continued to rely on electrum or gold. Others, such as Phaselis in Lycia, which did not have access to ready supplies of these metals, used silver for their early coinage. One of the first western Greek poleis to strike silver coins was Aigina, strategically located on an island between Attica and the eastern Peloponnese and an important commercial center. Soon after, other regional cities began striking their own coinages. Most prominent among these were the large cities of Athens and Corinth, but also smaller centers, such as Chalkis in Eretria and Karystos in Euboia, began striking at this early time. By the end of the sixth century BC, some cities in Magna Graecia and Sicily, as well as the Thraco-Macedonian tribes, were also striking coins on their own weight standards. As a result, a number of different weight standards existed simultaneously throughout the Greek world.

The earliest of the prevailing weight standards in mainland Greece at the time was the Aiginetic standard, based on a silver stater of 12.1 g. The standard received its name from Aigina, the most prolific issuer of coins at this weight. The Aiginetic stater was widely adopted in the Peloponnese, Central Greece, and the southern Aegean region (the Cyclades, Crete, and southwest Asia Minor). Although Athens eclipsed Aigina politically and economically in the mid-5th century BC, the Aiginetic weight standard remained in use in many places. The second was the Corinthian standard, based on a stater of 8.6 g. Although this standard was closely linked to the Attic, since the Corinthian stater was the same weight as the Attic didrachm, the Corinthian stater was divided into three drachms of 2.9 g. Coins on this standard were produced over a long period at Corinth, with smaller and mostly late issues coming from her numerous colonies in northwest Greece, Italy and Sicily. The third, and the one that eventually superseded the other two, was the Attic standard, first based on a didrachm of about 8.6 grams, but later a tetradrachm of 17.2 grams. This standard was to become the principal standard following Athens’ domination of the Aegean world in the latter part of the fifth century BC. Other important early mainland weight standards were the Achaian, with a nomos of 8 g, used by the Greek colonies in southern Italy, and the Euboic, with a stater of 17.2 g, used by Euboia and its colonies in the northern Aegean and Sicily.

In the East, many of the mints of Asia Minor under Achaemenid domination, including those of Cyprus, continued to strike coins on the Persian standard, derived from the bimetallic coinage of Kroisos. Unlike the Lydians, the Greek poleis continued to use electrum for the majority of their coins, issuing staters and fractions down to ninety-sixth-staters. Silver was introduced in the closing decades of the 6th century, though it seems to have played only a subsidiary role to the more important electrum issues. Quite a large number of mints seem to have been at work – Ephesos, Phokaia, Miletos, and others – though it is difficult for us now to attribute many types to their cities of origin. The picture is further complicated by the existence of several different weight-standards for the electrum coinage, and we find staters weighing 17.2 g (‘Euboic’ standard), 16.1 g (Phokaic), and 14.1 g (Milesian). Of these, the Phocaic standard was ultimately adopted for the extensive electrum coinages which the Asiatic Greeks produced in the fifth and fourth centuries BC, down to the time of Alexander. Three mints were-principally involved in the production of this fascinating and beautiful coinage. Kyzikos, a Milesian colony on the sea of Marmara, issued a series of electrum staters (weight 16.1 g) of which more than two hundred different types are known. The Ionian mint of Phokaia, and Mytilene, the chief city of Lesbos, produced long series of electrum hektai (sixth-staters, 2.6 g), possibly striking in alternate years. The products of the two mints are easily distinguished by their reverse type – those of Phokaia have a simple incuse square, while those of Mytilene have a reverse design, sometimes in incuse. After circa 400 BC, the Chian, or Rhodian weight standard, based on a tetradrachm of 15.6 g, achieved considerable popularity in Asia Minor, and was also adopted at Ainos in Thrace. It was based on a tetradrachm of 15.6 g.

In the Levant, the Phoenician weight standard, based on a silver shekel of about 14 g, was used by Sidon, Tyre, and Byblos. A similar standard existed in parts of northern Greece, though there can hardly have been any connection between the two. In fact, the whole question of weight standards in northern Greece is fraught with difficulties. Different standards appear to have been in use contemporaneously, sometimes at the same mint, and there were certainly three series of weights with no simple interrelationship. The whole group is termed the “Thraco-Macedonian” standard.

In the West, the closing decades of the sixth century also saw much activity in coin production at the colonies in Magna Graecia and Sicily. A unique type of coin production was used at some of the Italian mints, in which the obverse type was ‘mirrored’ on-the reverse, though incuse instead of relief. This peculiar technique was abandoned in the early part of the fifth century.

Archaic Sybaris nomos

Within each weight standard there was normally a wide range of denominations, serving the requirements of any variety of transaction, major to minor. Some denominations, such as the tetradrachm at Athens, the stater at Corinth, and the stater at Aigina, were struck more regularly than others. Some areas used only small denominations: most Peloponnesian mints, for example, seldom issued anything larger than a triobol (hemidrachm) during the fifth century BC. Other areas knew only larger coins: the Thraco-Macedonian tribes of the north regularly produced silver oktadrachms (29.5 g) and dodekadrachms (44.25 g).

In Sicily, the weight standard was based on the local bronze litra. The litra was at first represented by a small silver coin weighing 0.86 g. This silver denomination, however, proved troublesome, since it was often confused with an obol, and was replaced with a bronze version, possibly as early as the mid-fifth century BC. The convenience of this bronze coin was immediately apparent and became widely used in the area. One of the earliest cities to strike the bronze litra was Himera, a city on Sicily’s north. Although the original bronze litrai were cumbersome to use, their weight was soon reduced to a more acceptable level for everyday

circulation. These coins were accepted as a token currency, since their intrinsic value was considerably below their authorized circulating value. By the end of the fifth century BC, many of the Greek cities in Sicily had adopted this basemetal currency for small daily transactions. This was an important step in the development of a monetized economy and the use of fiat currency. The bronze litra was divided into twelve onkiai, from which the Roman uncia would derive its name. Unlike the cities to the east, those of Magna Graecia, and especially Sicily, often engraved a denominational mark on their bronze fractions, composed of pellets relative to the size of the fraction. The hemilitron, or 6 onkiai, with a mark of value composed of six pellets, was also struck, as well as the pentonkion (5 onkiai; five pellets), the tetras (4 onkiai; four pellets), the trias (3 onkiai; three pellets), the hexas (2 onkiai; two pellets), and the onkia itself (one pellet). This system of denominational marking by pellets is also found on some of the cities’ silver fractions. Over time, the concept of base-metal token coinage spread throughout the rest of the Greek world. Between approximately 400 and 350 BC, most Greek mints struck their first bronze issues, although some city-states continued to hesitate. A notable example was Athens, which continued to strike large quantities of small silver fractions well into the later fourth century BC when it, too, began striking bronze coins.

The main problem of Greek bronze coins is recognizing the denominational value in relation to the silver issues. Unlike the Sicilian mints, which clearly indicated the denominations of their bronze coins with marks of value, or Metapontion, which struck a remarkable late fourth century BC bronze inscribed “obol,” most Greek bronzes are without any mark to indicate their denominations. It is known that at Athens the obol was divided into eight chalkoi; the smallest Athenian bronze coin must then be the chalkous, a generic term meaning “bronze coin.” Larger denominations then would be multiples, such as the dichalkon (two chalkoi), tetrachalkon (four chalkoi = one hemiobol). Later, in the imperial period, the assarion replaced the chalkous. In Ptolemaic Egypt, bronze coins supplied the fractional denominations of the silver tetradrachm. The largest of these bronze issues, weighing over 40 g was the drachm; smaller denominations included the hemidrachm and obol. Otherwise, most Greek bronze coins are noted according their diameter in millimeters, a convenient, although most unsatisfactory, method of description. In this handbook series, the bronze coins are described by denominational size/weight modules following the system used in Seleucid Coins. Weight and diameter are given in parentheses.

Table 2. Table of Denominations Based on the Tetradrachm

AR

Metal

Pentakaidekadrachm 4 1/6

Double Oktodrachm 4

Dodekadrachm 3

Dekadrachm 2 1/2

Oktodrachm 2

Tetradrachm (base weight)

Didrachm 1/2

Tridrachm 1/3

Drachm 1/4

Tetrobol 1/6

Hemidrachm (Triobol) 1/8

Diobol 1/12

Trihemiobol 1/16

Obol (Tetratartemorion) 1/24

Tritartemorion 1/32

Hemiobol 1/48

Trihemitartemorion 1/64

Tartemorion 1/96

Hemitartemorion 1/192

Tetrachalkon 4

Dichalkon 2

Chalkous (base weight)

Hemichalkon 1/2

Table 3. Table of Denominations Based on the Stater

Denomination

EL/AV Stater (base weight)

Hemistater 1/2

Third Stater (Trite) 1/3 Quarter Stater 1/4

Sixth Stater (Hekte) 1/6

Twelfth Stater (Hemihekte) 1/12

Twenty-fourth Stater 1/24

Forty-eighth Stater 1/48

Ninety-sixth Stater 1/96

Hemistater 1/2

AR Stater (base weight)

Third Stater (Trite) 1/3 Quarter Stater 1/4

Sixth Stater (Hekte) 1/6

Eighth Stater 1/8

Twelfth Stater (Hemihekte) 1/12

Twenty-fourth Stater 1/24

Forty-eighth Stater 1/48

Ninety-sixth Stater 1/96

Table 4. Table of Denominations Based on the Shekel

Table 5. Table of Denominations Based on the Litra

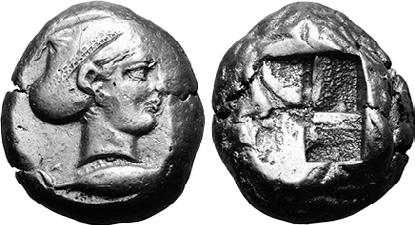

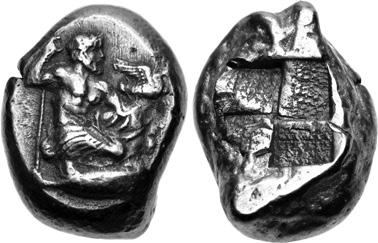

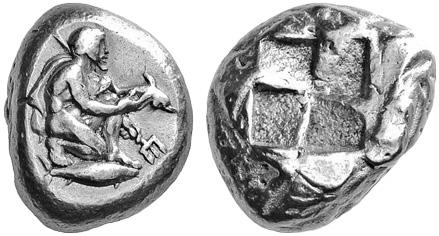

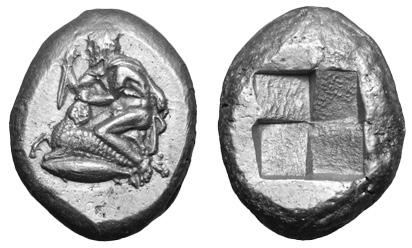

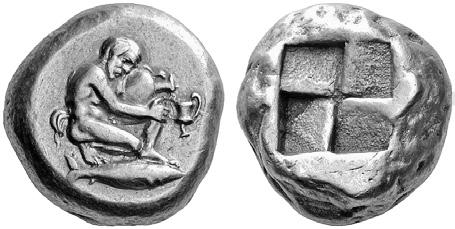

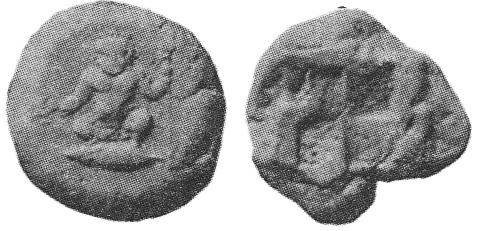

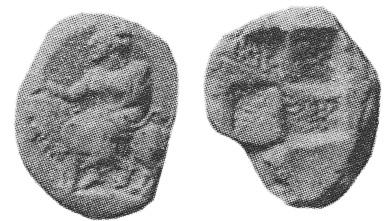

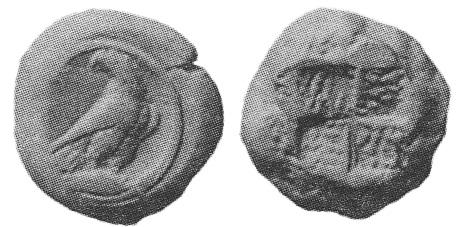

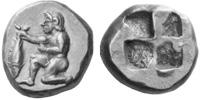

During the Archaic period, human representations follow a style similar to that in contemporary sculpture: the eye is often represented full face, even when in profile, and the mouth is always formed into what is called the “Archaic smile.” Full-length figures are represented in a manner similar to that of ancient Egyptian wall illustration, with the head and legs correctly in profile, but the torso viewed from the front. Movement follows a similar archaic convention: a running figure is depicted as if it were in a kneeling stance. For birds in flight, the body is rendered in profile while the wings are seen as if viewed from below.

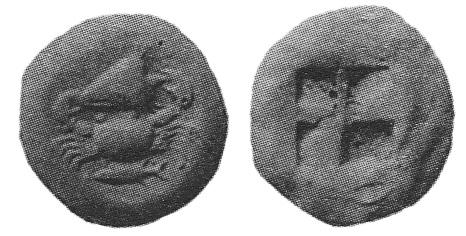

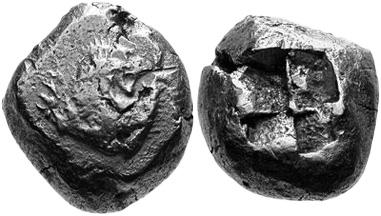

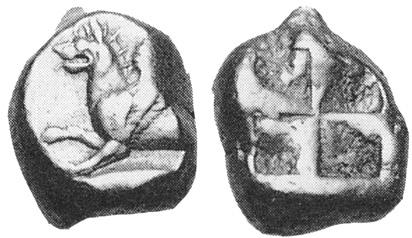

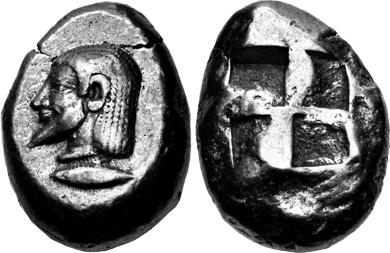

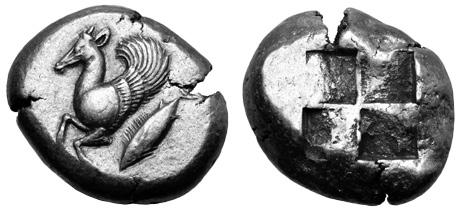

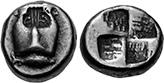

In Greece and the East, coins of this period had rather thick, almost globular, flans, and no reverse types; instead, they had an incuse of some form. These could be composed of single rough punches, various patterned punches, or, more often, punches divided into segments. In some cases, we know that the form or quantity of the punches present denoted the denomination. For instance, at Lydia, staters had two incuse squares divided by an incuse line, third-staters (trites), had two incuse squares, and sixth-staters (hektes) had a single incuse square. Over time, the incuses became more formalized, and sometimes had rudimentary designs. Also, their flans became more thin and broad. In the West, the coinage of Magna Graecia also began with incuse reverses, but these were struck from dies that had types similar to the obverse. The effect was that their coins had an obverse with a type in relief and a reverse with the same type in incuse. Sometimes subsidiary markings or the city ethnic would appear on these reverses in relief. The flans of these coins also differed from mints to the east in that they are first very thin and broad, and over time become more thick and compact. Finally, in the closing years of the sixth century BC, reverse types began to appear thoughout the Mediterranean. Some mints, such as Aigina, however, never abandoned the use of the incuse square reverse.

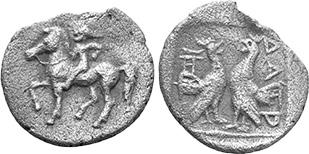

Persian gold daric

In 499 BC, the Ionian cities of Asia Minor revolted against Persian domination. Despite the assistance of Athens, the rebellion collapsed five years later. In revenge, Dareios I sent a naval expedition against Athens. After some initial success, the Persians were decisively beaten at Marathon (490 BC), celebrated afterwards as a pivotal battle of Greek independence against Persian domination. Xerxes, Dareios’s son and successor, planned a full-scale invasion of Greece to avenge the humiliation. In 480 BC, an immense Persian army crossed the Hellespont. It advanced through Thrace and Macedon into Greece with the support of a large fleet. At Thermopylai, a smaller Greek force, led by the Spartans under their king Leonidas, checked Xerxes, while the Athenian general, Themistokles, oversaw the construction of an Athenian fleet that then destroyed the Persian fleet at Salamis. Athens, however, was besieged, and its Akroplois, fortified with blocks of marble from its public buildings and fill composed of Archaic statuary, was sacked and burned. Soon thereafter, Greek forces under Sparta defeated the invading Persian army at Plataiai in 479 BC, bringing the war to an end. Henceforth, Persia never again intervened directly in the affairs of mainland Greece.

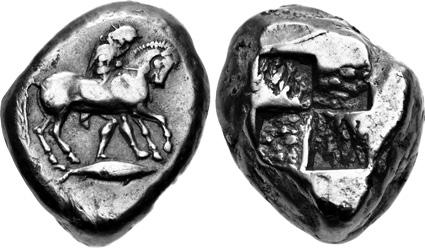

The Classical Period (479 – 336 BC)

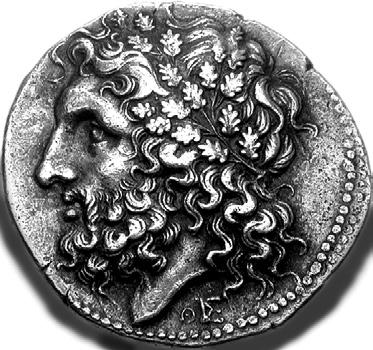

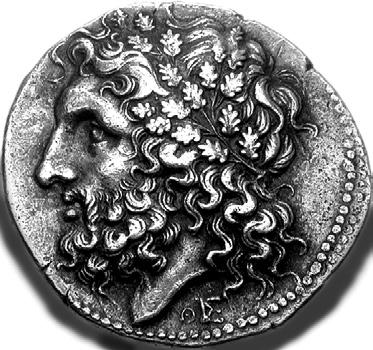

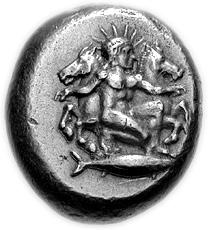

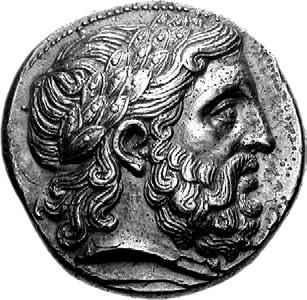

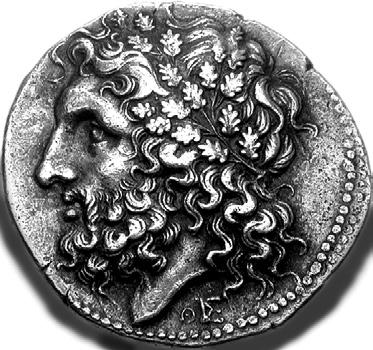

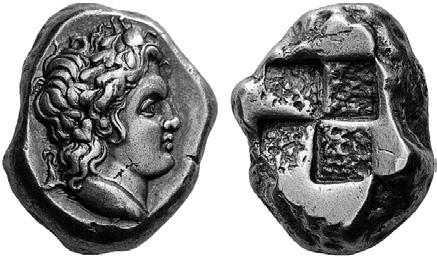

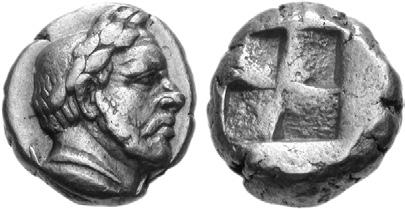

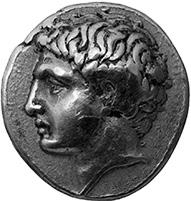

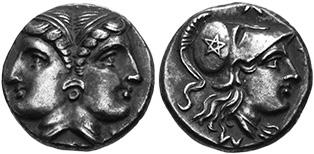

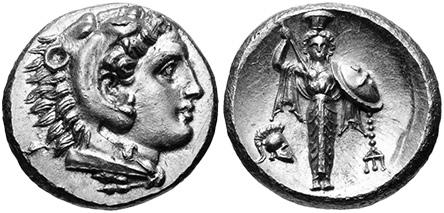

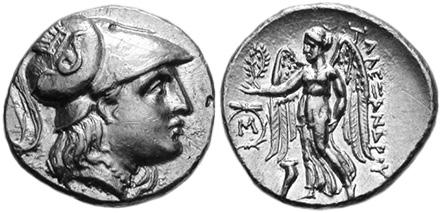

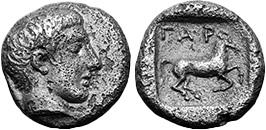

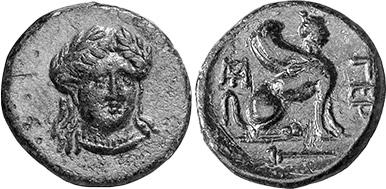

A classical masterpiece - Akragas tetradrachm; Classical Athenian tetradrachm; Classical Kyzikos tetradrachm

The Classical period of Greek coinage stretched from the conclusion of the Persian Wars in 479 BC to the death of Philip II of Macedon in 336 BC. This period oversaw a transition from the style prevalent in Archaic coinage to a more natural style, also occurring in Greek sculpture and gem cutting, as well as the application of a type to the reverse as well. The most notable exception was Athens, which retained an archaic style Athena and owl on its coinage until the early fourth century BC. Athens’ leadership among the Greeks following the Persians Wars became a source of contention, especially its role in the establishment of the Delian League, a confederation of Greek city-states whose purpose was to free the Ionian cities of Asia Minor from Persian control. Initially, each member made annual contributions, either in ships, or in cash payments deposited to the treasury on the island of Delos. Athens soon turned the League into its own maritime empire by transporting the League’s treasury from Delos to Athens, and requiring that subsequent member-state annual contributions be paid to Athens. In 449 BC, the Coinage Decree expanded Athenian imperialism by curtailing the production of many of the member-states’ coinages; instead, bullion was transported to Athens where is was minted into Athenian “owls.” City-states that were late in making their contribution were fined; those that tried to rebel against Athens, like Naxos, were enslaved. Athens also enjoyed plentiful supplies of silver in its own right, as the mines in Laurion produced large quantities of silver from which prodigious quantities of tetradrachms were struck. At the same time, the Athenian mint struck special issues of dekadrachms and didrachms. As a result, Athens became the richest and most powerful city-state in mainland Greece, and its coinage became the standard international currency. Consequently, a number of city-states outside of Greece adopted the Attic weight standard, or began striking imitative Athenian types as their own currencies. Nevertheless, unilateral Athenian actions precipitated the animosity of her fellow city-states. Sparta, which was equally involved in turning back Persia as Athens, and which had formed a similar antiPersian league, the Peloponnesian League, was particularly incensed at Athenian high-handedness. War eventually broke out between Athens and Sparta and their allies. Known as the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), it ruined Athens politically and financially, made Sparta (with Persian assistance) a dabbler in the internal affairs of Greece, and paved the way for the subsequent supremacy of Macedon.

Although the Greek poleis of Magna Graecia and Sicily remained relatively unaffected by events in mainland Greece, including the disastrous Athenian Sicilian Expedition (415–413 BC), they were frequently at war with Carthage. Descended from Phoenician traders who had established the north African trading outpost called Kart Hadasht (New Town), the Carthaginians had developed a strong economic presence in the western Mediterranean and frequently came into conflict with the Greek city-states there. During the fifth century BC, Sicily became an area of conflict between Carthage and the city of Syracuse. In 480 BC, the Syracusan tyrant Gelon decisively defeated the Carthaginians at Himera. Now the pre-eminent Greek city-state, Syracuse remained a tyranny under the members of Gelon’s family until 465 BC when the last member was overthrown and a democracy established. It lasted until 405 BC when Dionysios, a successful Syracusan commander, set up his own tyranny. After encircling Syracuse with a protective defensive wall, he pursued an aggressive, though inconclusive campaign against Carthage (397–392 BC); the result was a division of the island between the two powers. At the same time, Dionysios also pursued an aggressive policy against Rhegion and its allies in Magna Graecia, eventually conquering the city and selling its inhabitants into slavery. Dionysios also attacked the Etrucsan port of Pyrgi and sacked of the Temple of Leukothea at Caere, bringing him briefly into contact with Rome, an ally of that Etruscan city.

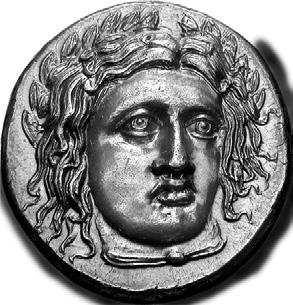

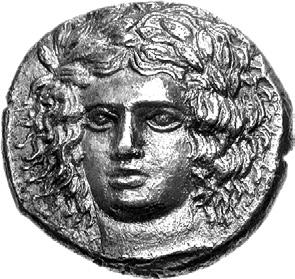

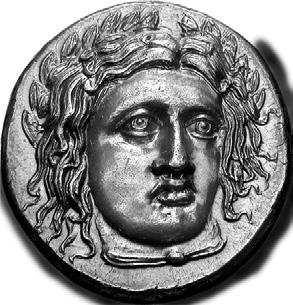

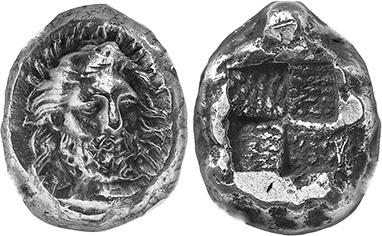

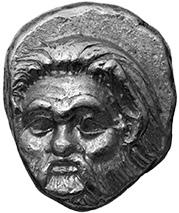

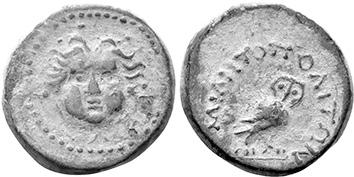

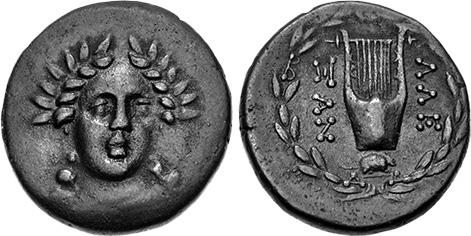

Dekadrachm of Syracuse

Greek coinage of Sicily reached heights of artistic brilliance during this period, particularly in the late fifth century BC, through the exceptionally skilled die engravers who signed their masterful dies, which served as an inspiration to dieengravers elsewhere and set a new standard for numismatic art. Notable among the beautiful issues of this period were the Syracusan dekadrachms with dies designed by Euainetos and Kimon, each of whom signed their masterpieces. Kimon is also regarded for his superb rendering of the facing head of Arethusa on a contemporary Syracusan tetradrachm, which became the model for similar facing-head types around the Mediterranean, at Larissa, Elis, and Lycia. The first half of the fourth century BC was perhaps one of the most prolific of the Classical period in terms of artistic ability. Of particular note are the Apollo facing head tetradrachms of Amphipolis, the lyre reverse tetradrachms of the Chalkidian League, the Zeus and Hera staters of Olympia, and the wide-ranging satrapal issues of Asia Minor, many of which feature the earliest human portraits on coinage.

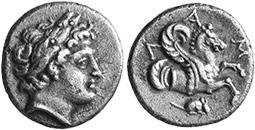

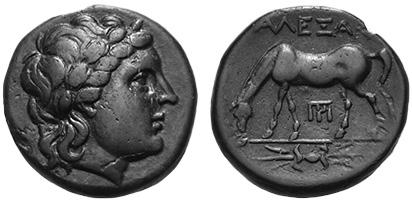

Tetradrachm of Philip II of Macedon

By the early fourth century BC, the kingdom of Macedon was emerging as a major power in northern Greece. Under Philip II (359–336 BC), Macedonian power saw a great expansion, not only into her neighbors Illyria, Paeonia, and Thrace, but also southward into Greece. In 357 BC, Philip captured Amphipolis, an Athenian colony near the rich silver-mining area of Mt. Pangaion in eastern Macedon. During the Third Sacred War (356–346 BC), Philip extended Macedonian control over Thessaly and was appointed tagos (leader) of the Thessalian League. In 348 BC, he razed Olynthos, the capital city of the Greek colonies that formed the Chalkidian League. Over the next several years, Philip was involved in consolidating his territories and fighting intermittently with Athens. At Chaironea in 338 BC, he and his son, Alexander, defeated the combined forces of Athens and Thebes, led by the Sacred Band. With this defeat, Athens sued for peace and the supremacy of Philip was acknowledged. A new league, the Corinthian League was formed as part of Philip’s larger strategy to invade Persia and liberate the Greek cities of Asia Minor. Unfortunately in the midst of this preparation, a member of Philip’s bodyguard, Pausanias of Orestis, assassinated the king.

Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Period (336 – 31 BC)

When Philip II was assassinated in 336 BC, preparations were already made for an invasion of Persia. That endeavor now fell to his son and successor, Alexander III (336–323 BC). A young man of remarkable abilities and the pupil of the philosopher Aristotle, Alexander defeated the Persian king Dareios III in three major battles: Granicus, Issus, and Gaugamela. Between 331 and 324 BC, he marched his Macedonian army to the Indus River, absorbing former Persian territories into his growing empire and building cities along the way. When he returned to Susa in 324 BC, he oversaw a mass wedding of his senior officers to Persian and other noblewomen. These actions were designed to unite Greek and non-Greek elements in a synthesis which later scholars have called Hellenism. Although Alexander’s plans for this unification began to disintegrate politically upon his death at Babylon on 11 June 323 BC, culturally, the ideals of Hellenism remained intact, particularly in the eastern kingdoms, long after Greek control over those areas was ceded to local authorities.

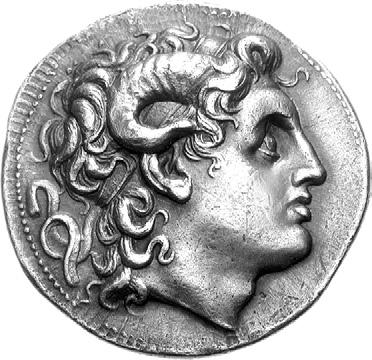

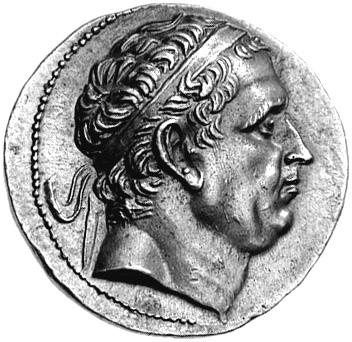

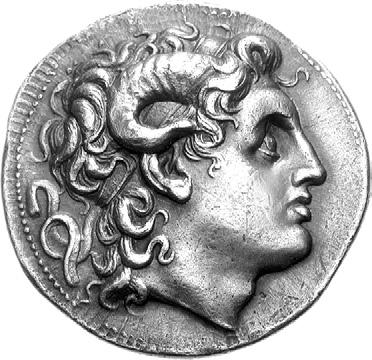

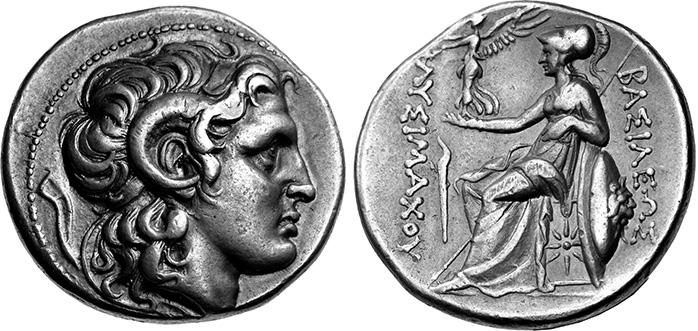

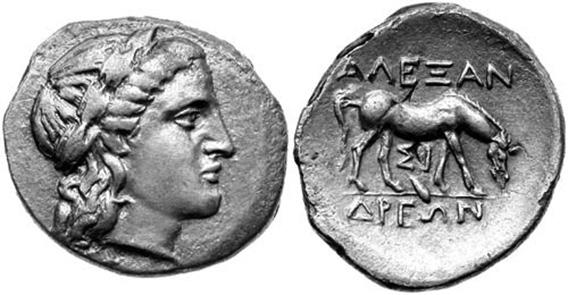

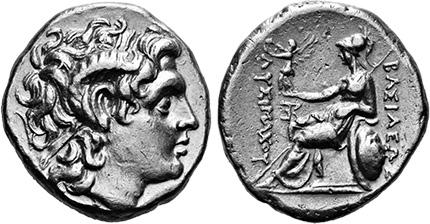

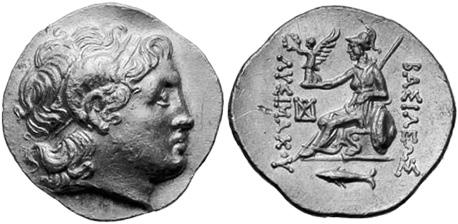

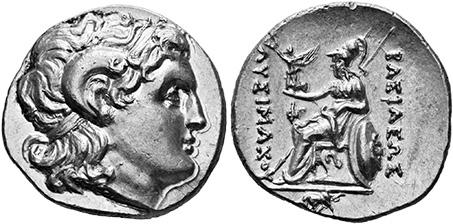

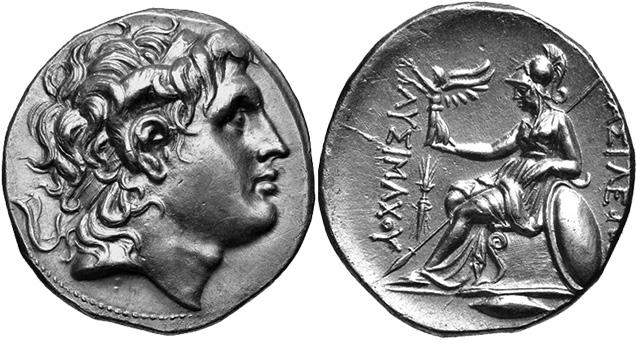

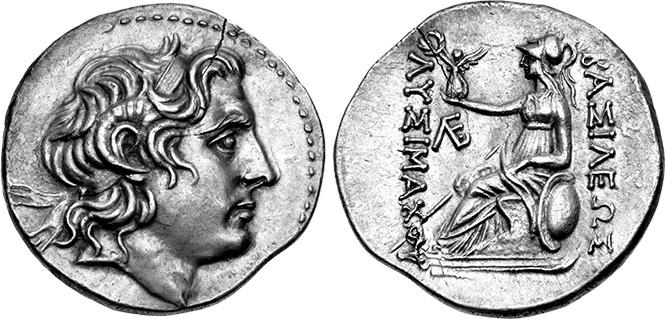

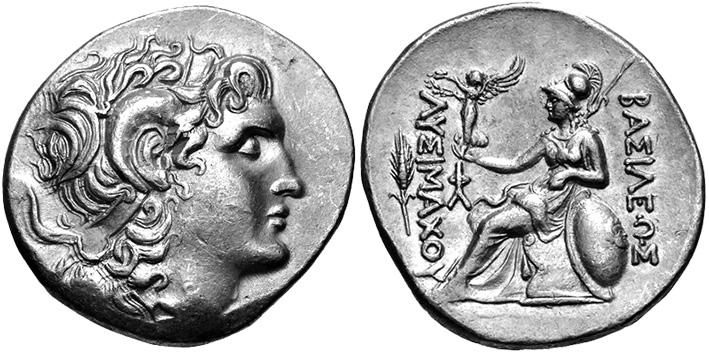

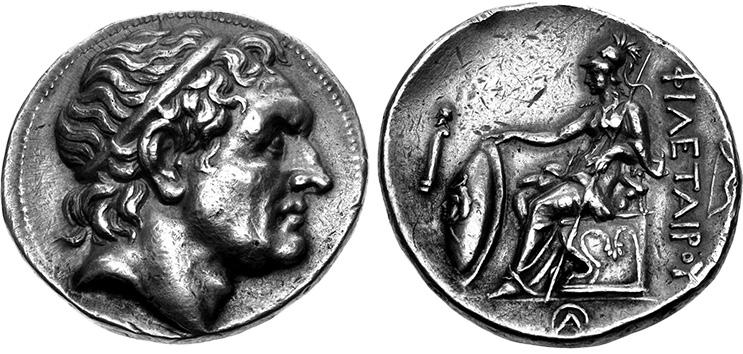

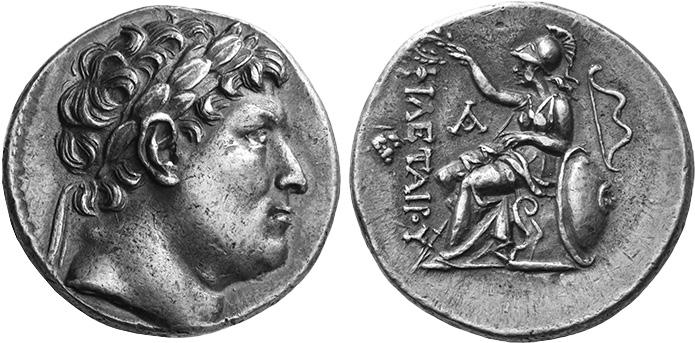

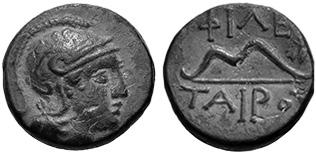

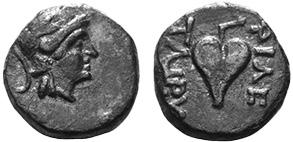

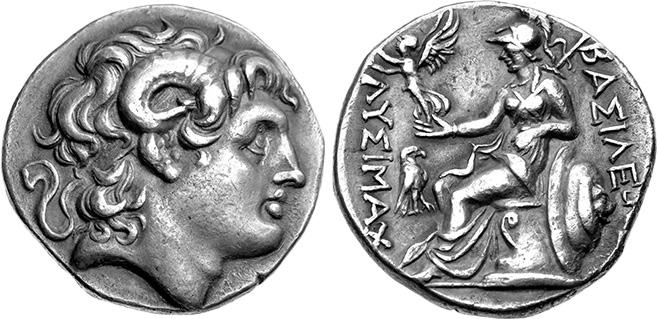

Lampsakos mint tetradrachm of Lysimachos from Thrace; Alexandria mint tetradrachm of Ptolemy I from Egypt

On Alexander’s death, his empire quickly broke apart. Although his halfbrother, Philip III Arrhidaios, and infant son, Alexander IV, were recognized by the Macedonian troops as joint kings, neither was in a position to assert their rule (Philip, though an adult, was mentally deficient). As a result, Alexander III’s associates, Perdikkas, Antigonos Monophthalmos and his son, Demetrios Poliorketes, Ptolemy, Seleukos, Kassander, and Lysimachos, seized the opportunity to carve out their own kingdoms. Known as the Diadochoi (Sucessors), their wars against each other lasted over the next forty years, each attempting to assert their supremacy over Alexander’s dominion. The legitimate kings, Alexander IV and Philip III, died by violent means early in this period of upheaval that encompassed the whole of Greece, Asia Minor, and the East. By 281 BC, all pretensions to a unified Macedonian Empire were largely abandoned, and Alexander’s vast territories were divided into separate kingdoms, most of which endured until they were conquered by the Romans in the second and first centuries BC. In addition to the kingdom of Macedon, the two major kingdoms to emerge were Egypt, ruled by Ptolemy I Soter and his descendants, and the empire of Seleukos I Nikator, comprising Asia Minor, Syria, and the territories stretching east to the Indus River. By the middle of the third century, however, parts of the large Seleukid empire broke away into other new Hellenistic kingdoms, the largest of which were western Asia Minor under the Attalid kings of Pergamon, Parthia under the Arsakids, and Baktria under the Diodotids and their successors (see below).

During the time of Alexander the Great and the Diodoch Wars, a new power was awakened in the West that would eventually bring an end to the Hellenistic Period. Rome began to expand her influence in Italy following the successful conclusion of the Latin War (340–338 BC), which quickly brought her into conflict with many of the older Greek poleis that had previously held power in Magna Graecia. The defining conflict was the Pyrrhic War (280–275 BC). Pyrrhos was the king of Epeiros, husband of Ptolemy I’s stepdaughter, Antigone, and a veteran of the Diodoch wars in the east, where he served under his brother-in-law Demetrios Poliorketes. Since he was unable to expand his power in the east, Pyrrhos looked west, and eagerly came to the aid of Taras (Tarentum), which was facing Roman conquest. With the arrival of Pyrrhos’s massive army, many of the Greek cities rallied to him against Rome, but the Romans and their allies were ultimately victorious. Pyrrhos was forced to return to Greece, where he briefly conquered Macedon before being killed at Argos in 272 BC. In the aftermath of the Pyrrhic War, most of Magna Graecia fell under Roman control, and much of the local civic coinage was reduced to small issues of bronze. Roman influence in Sicily grew as well, eventually leading Rome into a series of wars against the only other great

power left in the west, Carthage. The three Punic Wars, lasting from 264–146 BC, were the defining event for the Greek cities in the west, as they were invariably forced to submit to Roman or Carthaginian control. With the Roman destruction of the city of Carthage in 146 BC, the domination of Rome over all the western Greeks was complete. As in Magna Graecia following the Pyrrhic War, with the exception of limited issues of bronze, civic coinage ceased, and was replaced with coins of the Roman Republic.

From the time of the Second Punic War, Rome was also becoming entangled in the politics of the Hellenistic kingdoms to the east. During the First Macedonian War (215–205 BC), Rome fought against the energetic king of Macedon, Philip V (221–179 BC), and his Greek allies; while this war was in effect a draw, it nevertheless provided Rome a foothold in Greece. For the next five years, Philip tried to recover his losses and expand his regional power. Hostilities with Rome soon flared up again, sparking the Second Macedonian War (200–197 BC). In 197 BC at the battle of Kynoskephalai, Philip was defeated. Until his death in 179 BC, he ruled a much-reduced kingdom and was engaged in a series of border skirmishes. Philip’s son, Perseus, made one final attempt to reignite Macedonian power in Greece during the Third Macedonian War (172–168/7 BC). At Pydna in 168 BC, however, Macedonian royal power was finally extirpated, and the country became a Roman protectorate. Nonetheless, in 148 BC the pretender Andriskos sparked the Fourth Macedonian War (149–148 BC). This brief, and futile, attempt to reassert Macedonian independence sparked a conflict between the Achaian League and Rome that brought about the end of Greek independence on the mainland.

Shortly after the Macedonian defeat at Kynoskephalai, Antiochos III, “the Great” (222–187 BC), invaded Greece at the invitation of the Aitolian League in 192 BC. Defeated by the Romans at Thermopylai, Antiochos fled back to Asia Minor. In relentless pursuit, the Romans attacked him in 190 BC at Magnesia in Lydia. Antiochos was defeated and Seleukid power began its final decline. Much of Seleukid territory in Asia Minor passed now to Eumenes of Pergamon, who had been Rome’s ally during the campaign. Seleukid authority, now restricted to Syria and its environs, maintained a precarious existence for more than a century until Pompey the Great deposed its last king, Antiochos XIII Asiatikos, in 64 BC, and made Syria a Roman province.

In the years following Rome’s defeat of Antiochos III at Magnesia, most of southwestern Asia Minor was under the control of the Attalids of Pergamon, while another ally of the Romans, the kingdom of Bithynia, held the northwest. To the east lie the vestiges of Seleukid authority around Cilicia, while the rugged lands in the central region fell under the kings of Cappadocia. To the northwest was the kingdom of Pontos, whose expansionist policies under its king Mithridates VI (c. 119–63 BC) caused a series of three wars that culminated in the Roman annexation of Asia Minor in 63 BC.

While Egypt remained a sovereign state, the Roman presence in the east required its kings to maintain friendly relations with the Senate. Rome did not intervene directly in Egyptian affairs until 48 BC when Julius Caesar, pursuing Pompey after Pharsalus, arrived in Alexandria and became embroiled in a dynastic struggle between Cleopatra VII and her brother, Ptolemy XIII. Within the next seventeen

years, Ptolemaic Egypt became the last power to succumb to Roman domination, and with its end, the Roman Republic became a one-man state under the rule Caesar’s nephew, Octavian.

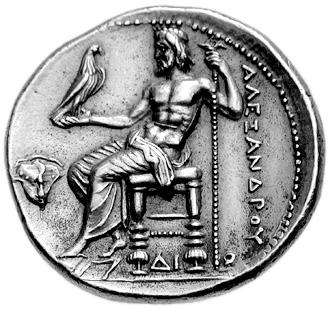

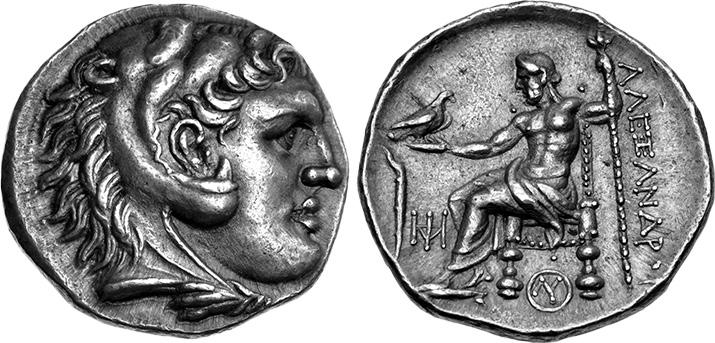

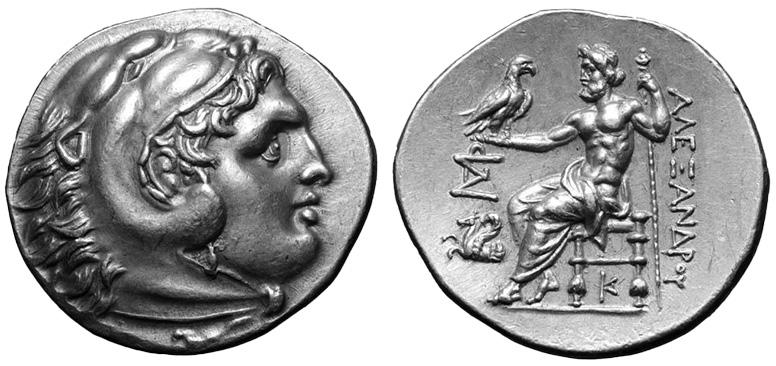

The political changes resulting from the rise of the Hellenistic kingdoms directly impacted the coinage of the Hellenistic period. As noted above, during the first half of the fourth century BC, many Greek city-states, experiencing their final period of autonomy, produced some of the artistic masterpieces of Greek coinage. The early issues of Philip II of Macedon, too, display a high quality of classical artistry. Possibly to counteract Greek claims of Macedonian “barbarism,” the dies of Philip’s coinage were engraved by imported Greek engravers. As the Macedonian Empire expanded under Alexander, other mints outside of Macedon were incorporated to meet the ever-increasing need for coinage, most likely for military purposes. By the time Alexander had reached the Indus in 324 BC, his coinage was being produced not only at Macedon, but also at mints throughout the eastern Mediterranean: western and southern Asia Minor, the Levant, Egypt, and the East. His coinage supplanted the civic issues of many of these mint cities for some time, and the Alexander-type tetradrachm became the new international coin for the next century, replacing the Athenian tetradrachm that had held that position in the Classical period.

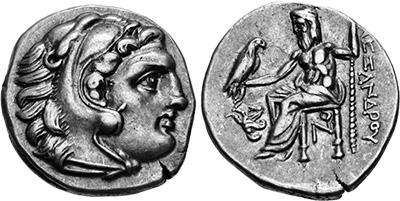

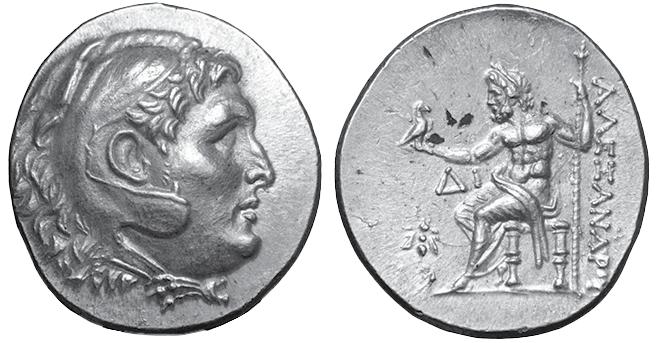

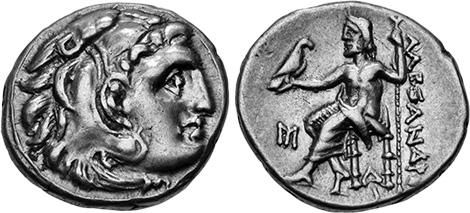

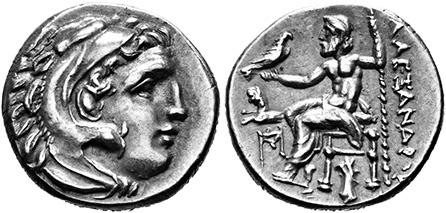

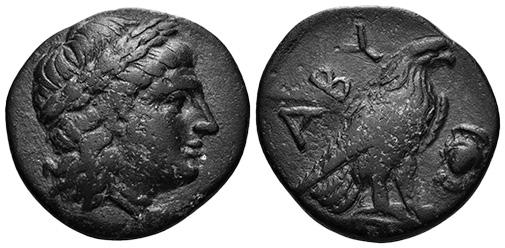

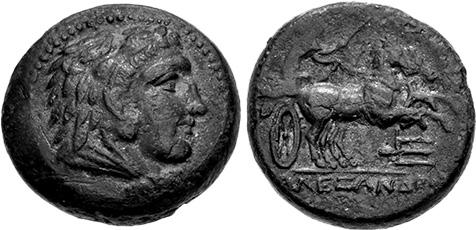

Alexander and his successors struck an immense amount of coinage to pay their large armies and support their imperial objectives. Early on, these coins continued to follow the types of Alexander with the head of Herakles on the obverse and Zeus enthroned on the reverse. Eventually, as these successor kingdoms began to assert their independence from the Macedonian empire, their rulers began to strike coins that were intrinsically their own. First, most replaced the name of Alexander with their own while retaining the types of the Alexandrine coinage. Soon thereafter, each replaced Alexander’s types with deities and symbols that were directly relevant to their own ruling house. Ultimately, mostly in the second generation of these kingdoms, the portrait of the ruling king replaced the deity on the obverse. These moves transformed the coins from a propaganda tool promoting Alexander’s Macedonian empire to one promoting the new kingdoms as separate, independent entities.

During the time of the Hellenistic kingdoms, many cities still struck their own civic coins, such as Athens; even some, such as Miletos, which were under the direct authority of the kingdoms, did so in limited quantities. In the West, however, where the kingdoms had relatively little influence, the coinage of Magna Graecia and Sicily continued much as it had before in the Classical period. Nevertheless, new coinage conventions to the East made an impression among some of the greater powers in the West. For example, in recognition of the popularity of the Alexander-type tetradrachms, the Carthaginian began to use the head of Herakles as the obverse type on their coins. At the same time, some local kings, such as Agathokles of Syracuse, began to issue coins that mimicked the types struck under the Diodochs, in an attempt to assert their equality to these great powers. In any event, changes in the west were not so much influenced by events in the east, but by the rise of Roman influence in their own sphere (see below).

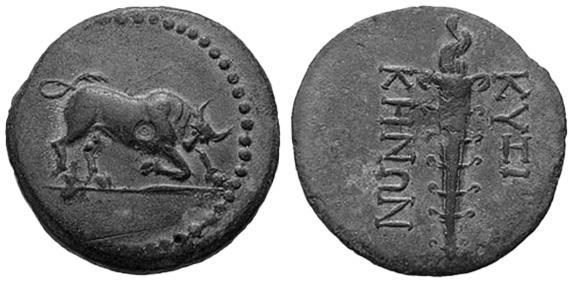

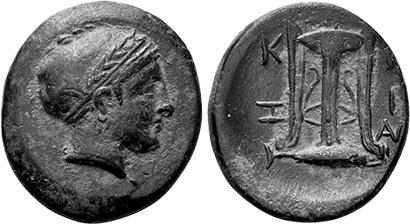

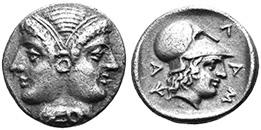

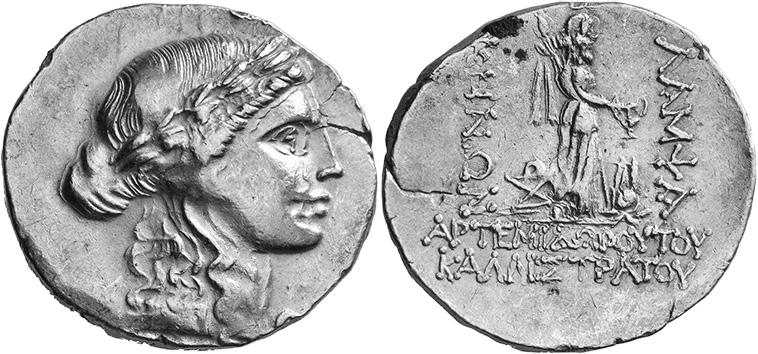

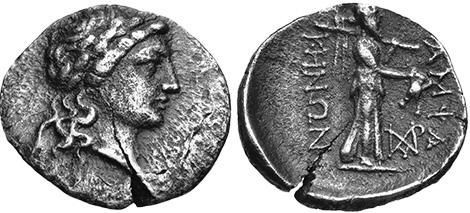

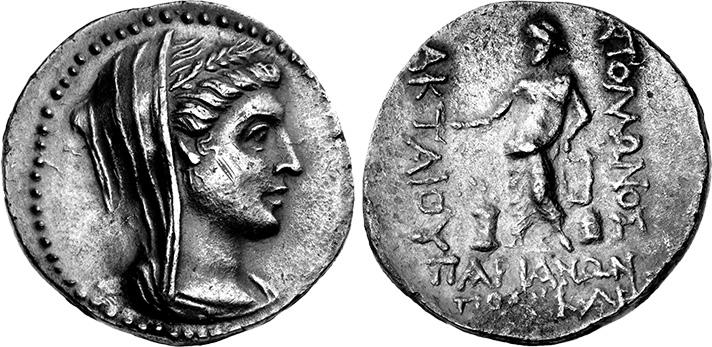

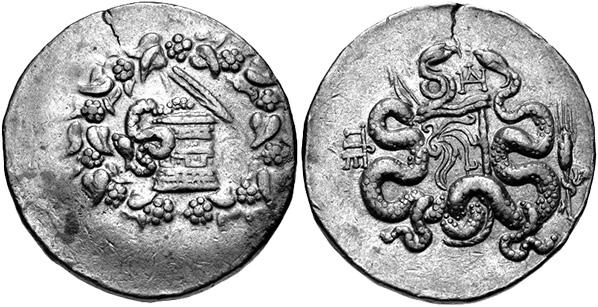

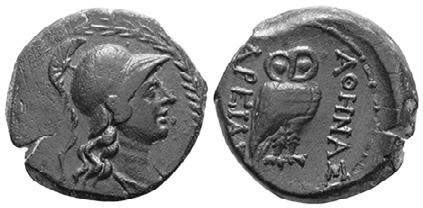

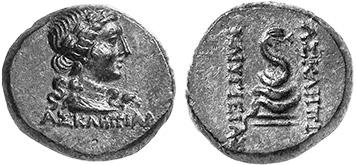

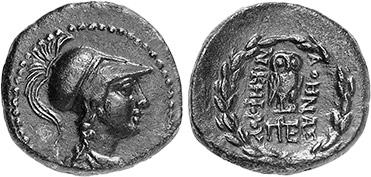

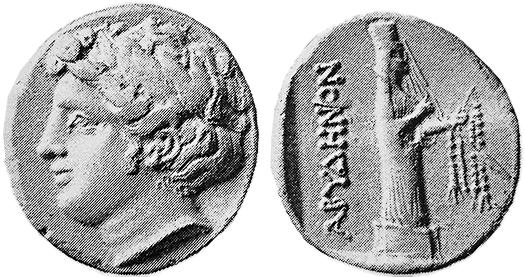

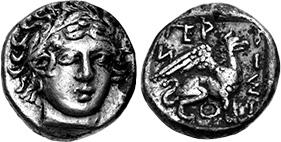

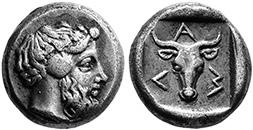

Athenian “New Style” tetradrachm; Stephanophoric tetradrachm of Kyme; Stephanophoric tetradrachm of Smyrna

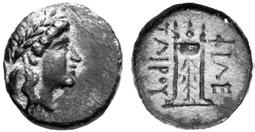

While the trends in coinage were shaped by the new kingdoms in the early part of the Hellenistic era, the change in the mid to late parts were influenced by reinvigorated civic coin production and the emergence of new leagues that brought together many poleis for a common cause. Circa 165 BC, the still-important city of Athens began to issue a new coinage that would influence the production of coinage throughout Greece and Asia Minor. This ‘New Style’ coinage was characterized by broad, thin flans that expanded the canvas upon which die engravers could create their images. At the same time, a trend developed in the typology of the reverse, in which the entire reverse type was enclosed within a wreath border. These wreath types were called stephanophoroi. Soon after Athens introduced its new coinage, these kinds of coins gained popularity around the Aegean, and was soon being struck in the kingdoms of Macedon, Bithynia, Pergamon, and Pontos, as well as by a wide range of cities, such as Athens in Greece; Apollonia, Odessos, and the isle of Thasos in Thrace; Kyme and Myrina in Aeolis; Ilion in Troas; and Herakleia, Magnesia, and Smyrna in Ionia.

In mainland Greece, a number of cities banded together to form leagues similar to those that had existed before the advent of Macedonian overlordship. Thessaly, Aitolia, and Arkadia each had their own league; each city within these leagues would take turns striking its issues. Arguably, the most important of these leagues was the Achaian League. Refounded in the early third century BC, it eventually became the major league in Greece and even the once-great Sparta was compelled to become a member. The Achaian League struck an immense coinage; consisting of silver hemidrachms and bronze tetrachalkoi and dichalkoi, more than twenty mints were involved in the production of these coins. In 148 BC, Sparta attempted to throw off its ties to the league, which responded by attacking the Lakedaimonians. Sparta, however, had called on Rome for help, and the resulting war between the Achaian League and Rome was quick and final. After making a last stand against the Romans at Corinth in 146 BC, the Achaian League’s army was scattered and

Corinth was sacked. In the aftermath, the league was abolished by Rome. With the consolidation of Roman power in mainland Greece, most cities either ceased producing coinage, or struck limited issues of token bronze.

Shekel of Tyre

In the Levant, the constant warfare between the Seleukid and Ptolemaic kingdoms prevented many civic issues from being struck –save for limited token bronze–since most of the mints were employed for striking royal issues. These royal issues continued to be struck on traditionally short, thick flans down to the very end of the empire.The lone exception is the Seleukid domains in western Asia Minor which did strike the new broad-flan coinage, but the loss of that territory by the mid-second century prevented any impact of this style of coinage on the eastern Seleukid mints. Nevertheless, the mints of Arados and Tyre in Phoenicia did produce significant precious metal coinages in the later Hellenistic period, as they were important international trading centers, which naturally would be impacted by major trends in coinage in the Aegean area. As a conduit between the East and the Aegean, their civic issues appear to be a hybrid between the new thin, broad flan coins and the old thick, short flan coins that were still popular with the Seleukids and Ptolemies.

By the mid-first century BC, the expansion of Roman power over the formerly independent Greek kingdoms and city-states was nearly complete. Most of Magna Graecia, Sicily, North Africa, Greece, Asia Minor, and Syria were now provinces of the Roman Republic, or tributary kingdoms. This paradigm shift in politics was inevitably paralleled by a shift in coinage. Some civic issues, mostly bronze, were sporadically struck, but these were only allowed at the behest of Rome, and, as such, are generally considered pseudo-autonomous issues. Such coinage is also considered to be among the earliest Roman Provincial Coinage, and is largely beyond the scope of this work.

Dated Greek Coins

Some of the earliest dated Greek coins were Phoenician issues which began carrying regnal years dates beginning in the early fourth century BC; this process

continued on their Alexander-type issues. By the third century BC, Ptolemaic silver coins were also carrying regnal year dates and, after the Seleukids had conquered Koile Syria and Phoenicia, they too adopted the practice. The Seleukid era began in 312 BC, when Seleukos I regained possession of Babylon, and all subsequent dates on Seleukid issues are relative to this era. The Ptolemies, however, indicated only the regnal year of the current monarch, which is problematic for numismatic research. The types used on most Ptolemaic coins stayed constant from one ruler to another, and very few used their epithets, so the dates, being regnal, are only marginally helpful in establishing a chronology for the rulers. Similarly, the dating used on civic issues is also problematic, as it is not always clear what era is being used as a basis, and some cities had more than one era that could be used. As a result, even if dates are present, numismatists may still need to resort to more subjective criteria, such as style and fabric, as well as hoard evidence, to establish the approximate period of issue for coins of this period.

The table below shows the alpha-numeric system used by the Greeks in dating their late Hellenistic and imperial issues:

Table 6. Greek Alpha-Numeric Table

The Eastern Kingdoms (mid-third century BC – mid-third century AD)

In the aftermath of the Diodoch Wars, the Macedonian empire forged by Alexander the Great was divided into a number of kingdoms. The largest of these was the Seleukid kingdom, which, by the beginning of the third century BC, controlled nearly all of Asia Minor, the Levant, and the eastern lands, stretching to the Indus River. Such a large territory was little more cohesive than the huge Macedonian empire it was carved from, with a wide variety of cultures that were as alien to each other as they were to their Macedonian overlords. Initially, the Seleukid system of governance was a continuation of that set up under Alexander, where much of the local institutions and leaders were retained from the Persian Empire. This was a relatively successful method of control, but as the Diodoch Wars continued the institutions and resources became strained. The wars moved the focus of the kingdom to its western territories, which allowed local leaders to exercise greater authority and independence. As a result, by the middle and late third century, a variety of revolts occurred in the East, some of which were successful in establishing new kingdoms that were largely based on ethnic identity.

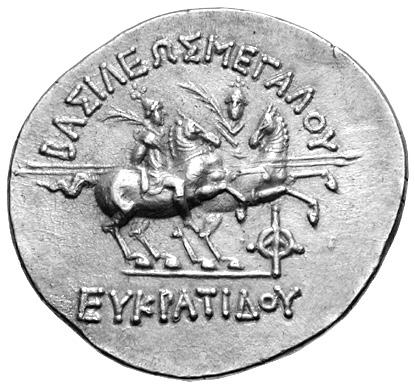

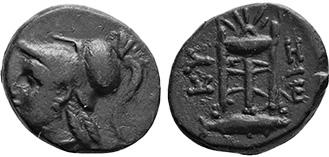

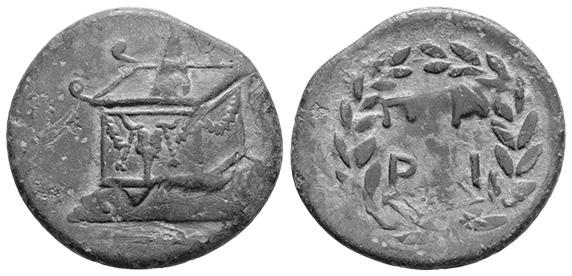

Persis tetradrachm of Bagadat; Parthian tetradrachm of Orodes I; Baktrian tetradrachm of Euthydemos I

The earliest of these kingdoms was Persis, in southwest Iran, and was probably already independent in the reign of Antiochos I as indicated by Persid overstrikes on Seleucid host coins; Parthia, in northern Iran, around the southeast corner of the Caspian Sea; and Baktria, in Afghanistan. The revolts that led to their creation were precipitated by the Second Syrian War, in which the Seleukid king Antiochos II Theos, led a large army to the western coast of Asia Minor. This was but the latest conflict in the long wars that had been ongoing for nearly fifty years, which left the East open to revolt. Both revolts in Persis and Parthia were ethnically based, instigated by their indigenous leaders. The secession of Baktria is complicated by contradictory evidence, as well as a conflicting chronology. In effect, sometime in the mid-third century BC (250 BC or 246 BC), the Baktrian satrap Diodotos I revolted, claiming independence and taking the title of king. The Seleukids, who were in no position to militarily challenge the revolts at the time, attempted to find ways to settle the situation, but finally were forced to come to terms with these kingdoms.

Seleukid authority continued to decline over the following century, both through continued wars in the west, and by the expansion of the Parthian kingdom in the east. Around which saw its territory expand greatly under Mithradates I. By the mid-second century, Mithradates had begun a vigorous expansion to the west, eventually capturing Mesopotamia and Babylonia from the Seleukids. This weakening of Seleukid control in the region led to the creation of two more kingdoms, Charakene, around the northern end of the Persian Gulf, and Elymaïs, centered on Susiana and Zagros mountains. Neither of these two kingdoms, nor Persis, however, retained their independence for long, as all three soon became tributaries of the Parthians, whose own kingdom remained ascendant well into the first century BC. By the mid to late first century, Parthia had grown to control nearly all of the lands east of the Tigris that were once held by the Seleukids, and even

threatened Syria on occasion. Unfortunately, as with the Seleukid kingdom, such a large territory also proved unwieldy for the Parthians, and internal dissention coupled with internecine disputes served to weaken their governmental control over the various ethnic groups they ruled. During this period, several independent kingdoms arose, including Commagene, Sophene, and Armenia Minor in the north, and Hatra and Nabataea in the south. Internally, these states often had two factions among their respective elite who would, for a time and depending upon which power was most influential there, vied with one another for local political control. Externally, these kingdoms became buffers between the various competing powers at the time and served as important staging areas for imperial expansion.

Baktria, too, became caught for a time in Parthia’s expansion. Fearing the potential isolation caused by a rising Parthian state, Diodotos I appears to have allied himself with Seleukos II when the latter sought to regain Parthia, going so far as to drive the Parthians from Baktrian territory, for which he adopted the epithet Soter. Diodotos’ son and successor, Diodotos II, however, allied himself with Arsakes I when Seleukos II tried to recover all of the lost eastern satrapies. This alliance was short-lived, for Diodotos II was overthrown by Euthydemos I. Around 208 BC, shortly after the Parthian kingdom had been recaptured and made a Seleukid vassal, Euthydemos was attacked by Antiochos III. After three years of war, a peace was negotiated, recognizing Euthydemos I as legitimate ruler. Under his immediate successor, Demetrios I, Baktria expanded its control across the Hindu Kush Mountains into northwest India, establishing a foothold in the northern parts of modern day Pakistan. Soon, however, the Hindu Kush proved more than a geographic boundary; the ethnic divisions on either side coupled with growing internecine dynastic struggles, resulted in the Baktrian kingdom splitting into two portions along the mountains, with the northern part traditionally called the GrecoBaktrian Kingdom, and the southern, the Indo-Greek Kingdom.