Carolingian Coinage and History Beginning as “mayors of the palace” under the preceding Merovingian kings, the Carolingians became kings of the Franks in their own right, and, under Charlemagne (AD 768-814), reestablished an emperor in the West. Although the dynasty’s name is derived from Charles Martel, who defeated the Moors at the Battle of Tours in AD 732, its founder was Saint Arnulf, bishop of Metz and the first of the “mayors of the palace” at the Merovingian court. In AD 751, Pépin le Bref (the Short) removed the last Merovingian king, Childeric III, and was declared king in his own right. But it was Pépin’s son, Charlemagne, who expanded Carolingian power to its greatest extent. In Frankish tradition, Pépin’s kingdom was divided upon his death between his two sons, Charlemagne and Carloman; at Carloman’s death three years later, Charlemagne became sole King of the Franks, and over the next three decades expanded Frankish power. Attempting to create an emperor in the west as a counterbalance to the Byzantine Empire, the Pope crowned Charlemagne as Emperor of the Romans on Christmas Day, AD 800. From this beginning, the Holy Roman Empire would be formed and the title which would continue to be held by its rulers until 1806. In AD 814 Charlemagne’s son, Louis, became sole ruler of the kingdom, but his reign was beset by numerous rebellions. Upon his death in AD 840, the division of the kingdom among his three sons, Lothar, Louis the German, and Charles the Bald, signaled the end of Carolingian unity. Civil war broke out among the three heirs, and at the resolution achieved with the Treaty of Verdun in AD 843, the empire was split into three regions: West Francia, Middle Francia, and East Francia. The western portion became the nucleus of later France, which eventually the Capetian kings would rule. East Francia became Germany and the Holy Roman Empire; the Carolingians who ruled there until AD 911 were succeeded by a Saxon dynasty, commonly referred to as the Ottonians, who consciously modeled themselves as Carolingian successors. Middle Francia, the weakest of the three, was soon divided and absorbed by both West and East Francia. The Carolingian currency system was establish in 755 under Pepin I. In addition to reducing the number of mints that had existed previously under the Merovingians, this reform strengthened royal authority over the minting of coins and, most especially, set forth uniformities of weight, fineness, and design. It also established a set relationship between the Carolingian silver denier, which had become the main denomination, and the fictional denominations of account – the shilling and the gold solidus – that were employed to handle larger sums. Under Charlemagne, this reform was implemented fully and expanded to meet the needs of his ever-increasing empire. Initially, Charlemagne’s deniers followed the weight and general type of Pepin I. As new sources of silver were discovered, and as Charlemagne acquired more power and territory, he issued new, heavier deniers of differing types, some of which types continued under his successors. One of these was the cross pattee / monogram type. Under each successive ruler, the type would be continued with only the monogram being changed to fit the name of the new ruler. Under Charlemagne’s successor, Louis I ‘le Pieux’, a new type, the XPISTIANA RELIGIO, was introduced and featured a temple facade on the reverse A third type was that with the obverse legend, which originally had the name of the emperor, now replaced with the phrase GRATIA D-I REX, along with the monogram on the obverse, and a cross pattee with the mint name on the reverse. These last two types became so popular that early feudal issuers copied them for their own coinage, long after the Carolingian rulers themselves were gone. Known as immobilized types, the Carolingian denier (and its fraction, the obole) continued as a denominational type throughout western Europe in the form of the denar, denaro, and even the English penny (notated as d. in accounting) for most of the Middle Ages until the introduction of the larger gros in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

From the Garrett Collection

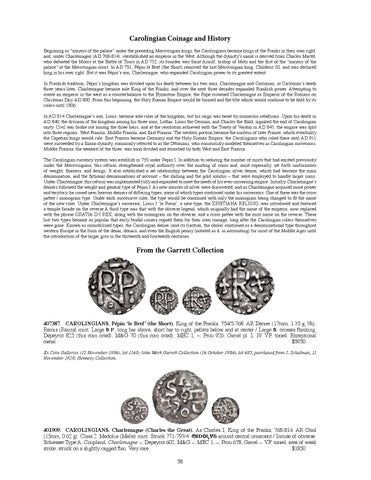

407387. CAROLINGIANS. Pépin ‘le Bref’ (the Short). King of the Franks, 754/5-768. AR Denier (17mm, 1.35 g, 9h). Remis (Reims) mint. Large ⎁ ʖ; long bar above, short bar to right, pellets below and at center / Large ⎁; crosses flanking. Depeyrot 825 (this coin cited); M&G 70 (this coin cited); MEC 1, –; Prou 926; Gariel pl. I, 19. VF, toned. Exceptional metal. $5950 Ex Coin Galleries (12 November 1986), lot 1160; John Work Garrett Collection (16 October 1984), lot 685, purchased from J. Schulman, 11 November 1928; Hennesy Collection.

401909. CAROLINGIANS. Charlemagne (Charles the Great). As Charles I, King of the Franks, 768-814. AR Obol (15mm, 0.62 g). Class 2. Medolus (Melle) mint. Struck 771-793/4. ȓĩዝ⌴8VS around central ornament / Incuse of obverse. Schiesser Type A; Coupland, Charlemagne –; Depeyrot 602; M&G –; MEC 1, –; Prou 678; Gariel –. VF, toned, area of weak strike, struck on a slightly ragged flan. Very rare. $1850 58