one

COVER STORY

14 22 6 26 8

Marking a Century of Healing and Hope CNEWA launches its centennial year by Michael J. La Civita

FEATURES

A Tentative Peace

Lebanese assess their future as strikes continue text by Laure Delacloche with photographs by Raghida Skaff

No Alternative to Dialogue

Bosnia and Herzegovina still healing after genocide text and photographs by Anna Klochko

A Letter From Armenia

Caritas Armenia marks 30 years of charity and hope text by Anahit Gevorgyan with photographs by Nazik Armenakyan

A Light in the Desert

New life springs forth at an ancient Syrian monastery by Claire Porter Robbins

Piece by Piece

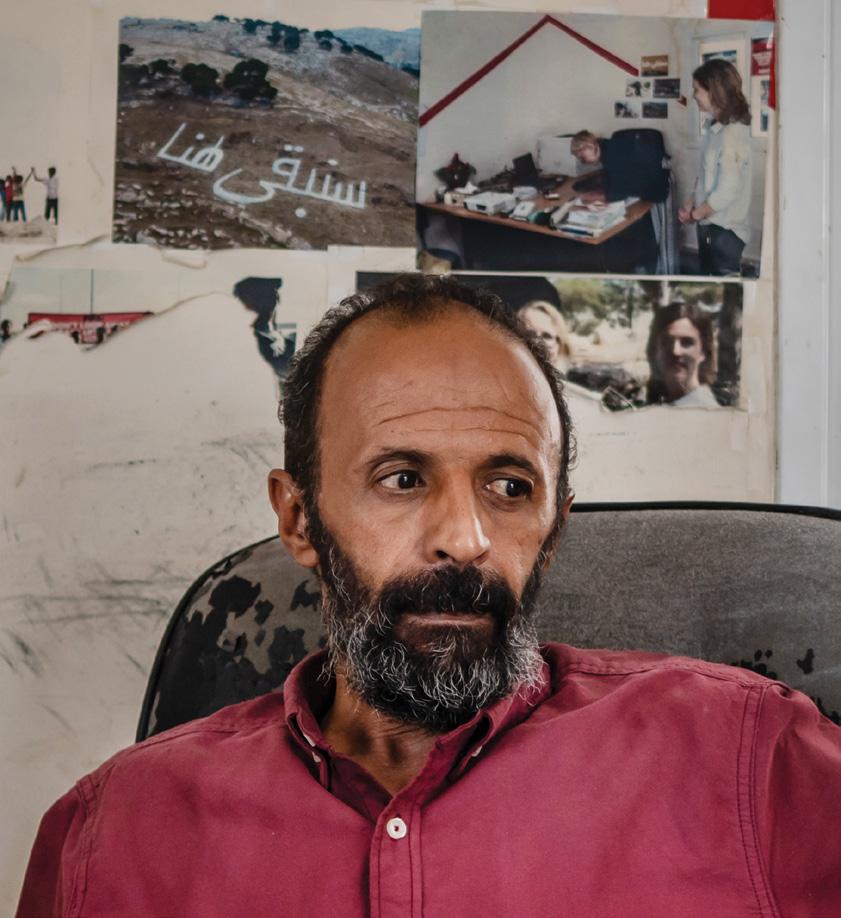

West Bank Palestinians brace for what looms next text by Leila Warah with photographs by Samar Hazboun

DEPARTMENTS

4

Connections to CNEWA’s world

The Last Word

Perspectives from the president by Msgr. Peter I. Vaccari

t The ancient monastery of Deir Mar Musa rises above the Syrian desert.

Front: Stonemasons lay marble inside the Orthodox Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Mostar,

Back: Artyom Hovhannisyan, in a black sweater, is with his brothers at their home in Gyumri. He attends a Caritas Armenia program that provides resources for children with disabilities.

Photo Credits

Front cover, pages 14-15, 17-20, Anna Klochko; pages 2, 28, Ahmad Fallaha; page 3 (top), Maria Grazia Picciarella/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images; pages 3 (upper left), 8-13, Raghida Skaff; pages 3 (upper right), 7, Sister Christian Molidor, R.S.M.; pages 3 (lower left), 23-25, back cover, Nazik Armenakyan; pages 3 (lower right and far right), 32-37, Samar Hazboun; page 4, Joseph Saadeh; pages 26-27, 29, Louai Beshara/AFP via Getty Images; pages 30-31, Ghaith Abdul-Ahad/Getty Images; page 38, Matteo Della Torre/NurPhoto via Getty Images.

ONE is published quarterly. ISSN: 1552-2016

CNEWA

Founded by the Holy Father, CNEWA shares the love of Christ with the churches and peoples of the East, working for, through and with the Eastern churches.

Volume 51 Number 4

CNEWA connects you to your brothers and sisters in need. Together, we build up the church, affirm human dignity, alleviate poverty, encourage dialogue — and inspire hope.

Publisher

Msgr. Peter I. Vaccari

Executive Editor

Michael J. La Civita

Editorial

Laura Ieraci, Editor

David Aquije, Contributing Editor

Barb Fraze, Contributing Editor

Elias D. Mallon, Contributing Editor

Creative

Timothy McCarthy, Digital Assets Manager Paul Grillo, Senior Graphic Designer

Samantha Staddon, Graphic Designer

Elizabeth Belsky, Copy Writer

Officers

Cardinal Timothy M. Dolan, Chair and Treasurer

Msgr. Peter I. Vaccari, Secretary Tresool Singh-Conway, Chief Financial Officer

Editorial Office 220 East 42nd St, New York, NY 10017 1-212-826-1480; www.cnewa.org

©2025 Catholic Near East Welfare Association.

Msgr. Peter I. Vaccari, CNEWA president, led a delegation on a pastoral visit to the Holy Land, 2-6 September, as a gesture of solidarity with its beleaguered Christian community. The delegation included Baltimore Archbishop William E. Lori, vice president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, Patrick E. Kelly and John Marella, supreme knight and supreme secretary, respectively, of the Knights of Columbus, and CNEWA’s director of communications and marketing, Michael J. La Civita.

The visit to Jerusalem, the Palestinian West Bank and Israel included liturgies in the churches of the Holy Sepulchre, Nativity and Annunciation, and meetings with leaders of the region’s small Christian community, which has been a leading provider of

emergency aid and social services for all communities in the strifestricken region.

“What you see is that even in a time of great darkness and suffering, the light and the goodness and the glory of Christ shine through in these ministries,” Archbishop Lori said upon his return to Baltimore.

“We found pastors, compelled by the Gospel, to counter hate with love,” Mr. La Civita told America magazine. “We met women and men of faith determined, not despondent, to carry on the work of the church as it witnesses the poor and marginalized.”

The pastoral visit also deepened CNEWA’s partnerships with mission-aligned organizations, including the Sovereign Order of Malta, the Equestrian Order of the

Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem, the Knights of Columbus and the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. On the ground CNEWA works solely with the local churches, supporting their initiatives and efforts to provide medicine, food, education and psychosocial support.

The U.S. Catholic bishops reissued a call to support church-based humanitarian efforts in Gaza after the ceasefire agreement that came into effect on 10 October, directing donors to CNEWA and Catholic Relief Services. The peace agreement was followed by the release of the remaining surviving Israeli hostages by Hamas and 250 Palestinian prisoners. Hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, displaced by orders of the Israeli military, returned to

the north, most finding their homes reduced to rubble, said Joseph Hazboun, CNEWA’s regional director for Palestine and Israel. CNEWA and its partners were working to help provide shelter, water and medical aid, noting that clearing the rubble to rebuild could take up to three years. To support CNEWA’s work in Gaza, go to www.cnewa.org/donate.

Pope Leo XIV issued his first apostolic exhortation, “Dilexi Te” (“I Have Loved You”), on 9 October. “Love for the poor — whatever the form their poverty may take — is the evangelical hallmark of a church faithful to the heart of God,” he wrote. He said many Christians “need to go back and re-read the Gospel” because they have forgotten that faith and love for the poor go hand in hand.

At the time of publication, Pope Leo was scheduled for his first trip outside Italy with plans to visit Turkey, 27-30 November, and from there to Lebanon until 2 December. The trip was built around the promise of Pope Francis to join Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople in marking the 1,700th anniversary of the First Ecumenical Council of Nicaea, at which the foundational tenets of Christianity were formulated into what is now the first half of the Nicene Creed, recited by all mainline Christians. In Lebanon, Pope Leo was expected to commemorate the 2020 port explosions in Beirut.

Catholic Near East Welfare Association kicked off its centennial with two gala events — the first in Ottawa, 7 November, and the second in New York, 1 December. Born as empires

crumbled in Europe and the Middle East, CNEWA became an instrument of the Holy See to serve and bolster the Eastern churches in their service to those most in need, especially survivors of war and genocide, revolution and civil war, social chaos and poverty.

A century later, CNEWA continues its service as an agency of healing and hope, working for, through and with the Eastern churches in the Middle East, Northeast Africa, India and Eastern Europe.

Initiatives to mark the centennial will be announced in the new year.

This autumn, the universal church recognized two martyrs of the Eastern Catholic churches.

On 19 October, Pope Leo XIV canonized Armenian Catholic Archbishop Ignatius Choukrallah Maloyan in St. Peter’s Square. He served as archbishop of Mardin in Ottoman Turkey from 1911 until his death in June 1915. Arrested by Ottoman authorities during the mass roundup of Armenian and Assyro-Chaldean Christians, recognized today as the Armenian genocide, he refused to renounce his Christian faith and was subsequently tortured and killed.

On 27 September, the Rev. Petro Oros, a priest of the Ruthenian Greek Catholic Eparchy of Mukachevo, was beatified during an outdoor Divine Liturgy in Bilky, Ukraine. Henchmen of the Soviet regime murdered the 36-year-old priest in 1953 as he brought the Eucharist to a sick person.

The generosity of people of good will, with their prayers and financial gifts, brings to life the mission of CNEWA as it witnesses the Gospel in service to the Eastern churches. Thanks to Catholics across the United States, CNEWA has received more than $1.5 million from U.S. parishes and dioceses for its life-saving work in Gaza and the wider Middle East. In addition to regular sustaining contributions from donors and friends worldwide, CNEWA received several significant grants, including $250,000 from the Knights of Columbus for its efforts in Gaza and the Middle East; $100,000 from the Diocese of Venice in Florida for its work in Ukraine; and $20,000 from the Pulte Family Charitable Foundation for emergency relief in the Holy Land. To learn more about CNEWA’s grant program, contact Bradley Kerr at bkerr@ cnewa.org.

by Michael J. La Civita

As we close the first quarter of the 21st century, we find a world in conflict and sociocultural, economic and political chaos. The optimism and hopes of the end of the previous century have evaporated, replaced instead with pessimism, fear, anger and resentment.

“In this time,” Pope Leo XIV said in his homily inaugurating his pontificate on 18 May 2025, “we still see too much discord, too many wounds caused by hatred, violence, prejudice, the fear of difference, and an economic paradigm that exploits the earth’s resources and marginalizes the poorest.”

For the church’s part, he continued, “we want to be a small leaven of unity, communion and fraternity within the world. We want to say to the world, with humility and joy: Look to Christ! Come closer to him! Welcome his word that enlightens and consoles! Listen to his offer of love and become his one family: In the one Christ, we are one.”

As an agency of the Holy See, Catholic Near East Welfare Association has, since its founding by Pope Pius XI on 11 March 1926, worked as that “small leaven of unity, communion and fraternity,” specifically among the peoples of the Eastern churches, and the marginalized and vulnerable served through the many pastoral and humanitarian works of these communities of faith.

CNEWA began as a ray of light, a glimmer of hope during a particularly dark period in the history of humanity. The “War to End All Wars” — World War I — foreshadowed greater devastation long after the armistice ended the war in 1918, unleashing crises on a massive scale as the Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman and Russian empires collapsed.

Moved by the plight of millions of survivors of war, genocide and revolution, and a firm advocate of church unity, particularly among Catholics and

Orthodox, Pope Benedict XV initiated church-led humanitarian responses in Asia Minor and Europe. His successor, Pius XI, continued these efforts after Benedict’s premature death in January 1922, reaching out to Catholics in the United States, including the founder of the Franciscan Friars of the Atonement, the Rev. Paul Wattson, a zealous advocate of church unity who in 1908 founded the Octave of Church Unity when still an Episcopalian.

Moved by the pope’s appeals for help, Father Paul encouraged his supporters, mainly in the pages of his monthly magazine, The Lamp, to fund the tireless Greek Catholic Bishop George Calavassy and the English military chaplain, Msgr. Richard Barry-Doyle, who together worked among the tens of thousands of Armenians, Assyro-Chaldeans, Greeks and anti-Bolshevik Russian refugees inundating Constantinople — the capital of the dissipating Ottoman world.

In December 1924, Father Paul, Msgr. Barry-Doyle and a group of prominent Catholic laymen established in Philadelphia “the Catholic Near East Welfare Association” as a vehicle to assist Bishop Calavassy’s work with the displaced Christians of the “Near East.” Msgr. Barry-Doyle’s theatrical speaking circuit, entitled “The Call of the East,” packed concert halls across the United States — including Manhattan’s Carnegie Hall — and raised awareness and funds to help this CNEWA prototype address the needs of the displaced in Constantinople.

The activities of the “Children’s Crusader,” as Msgr. Barry-Doyle was called, complemented the more cerebral efforts of a German Benedictine priest, Augustine von Galen. The elder brother of Bishop Clemens von Galen — the famed anti-Nazi cardinal known as the “Lion of Munster” — Father von Galen traveled to North America in 1924 at the behest of the Sacred Congregation for the Eastern Churches to raise

awareness and funds for the Catholic Union, which advocated for the reunion of the Catholic and Orthodox churches, which popes Benedict XV and Pius XI enthusiastically promoted. Relief and reunion were not mutually exclusive and, in March 1926, with the urging of members of the U.S. Catholic hierarchy, the pope combined these two organizations into a single papal agency with its board of directors chaired ex officio by the archbishop of New York. The pope retained the name Catholic Near East Welfare Association, thereby centralizing and strengthening the various efforts of the Eastern churches throughout what was then called the Near East.

Nearly a quarter of a century after Pope Pius XI founded CNEWA, his successor appointed CNEWA’s Msgr. Thomas J. McMahon as president of an ad hoc task force of the Holy See to coordinate worldwide Catholic aid for Palestinian refugees, hundreds of thousands of whom had fled their homes after the hasty departure of British troops from Mandatory Palestine in 1948. Pius XII placed the leadership and administration of Pontifical Mission under CNEWA, and his successors have extended and made permanent its mandate for the needs of all vulnerable people throughout the Middle East.

Relief and reunion, in a nutshell, describes the narrative of this agency of healing and hope these past 100 years. And in times where nothing is certain but continued division, chaos and conflict, CNEWA remains a beacon of hope, a leaven for unity, communion and fraternity.

An integral component of the bishop of Rome as the successor of Peter as pontifex maximus — the ultimate bridge builder — CNEWA continues to counter modern society and its exploitation of

humanity’s inherent differences, whether by nationality, ethnicity, religion, politics or culture. Instead, CNEWA takes another path, one urged by our present pontiff, “with our sister Christian churches, with those who follow other religious paths, with those who are searching for God, with all women and men of good will, in order to build a new world where peace reigns! …

“Together, as one people, as brothers and sisters, let us walk toward God and love one another.” n

Executive editor Michael J. La Civita is director of communications and marketing.

Breaches in the ceasefire between Israel and Hezbollah keep Lebanese on high alert text by Laure Delacloche with photographs by Raghida Skaff

Aroom with a double bed, a television, a refrigerator and a few chairs are all that serve as shelter for a southern Lebanese family living on the outskirts of Beirut.

Elie Jamal, 34, his pregnant wife and his mother have adapted to their living situation in Nabaa, where rents are more affordable than in Beirut, and Hezbollah banners hang above the streets.

“We come from a calm village,” says Mr. Jamal, an Orthodox Christian. “Here, at night, we cannot sleep because there is so much noise. Residents frequently shoot in the air whenever someone dies or gets married.”

On a mid-October morning, his mother takes coffee to Manal Chahine, their neighbor, who — with her husband, three children and six relatives — also found refuge from the Israel-Hezbollah war.

The Jamals and Chahines were living in their Lebanese villages of Qlayaa and Ebel el-Saqi respectively. On 8 October 2023, Hezbollah, a Lebanese political party and Shiite militia, launched air attacks on Israel in support of Hamas, after Israel began bombing Gaza in retaliation for Hamas attacks on Israel on 7 October.

When Israeli military first responded with a bombardment campaign and drone attacks limited to the south of Lebanon and the Bekaa region, the two families were able to remain in their villages. However, the drastic escalation of the war in September 2024 led the Jamals, the Chahines and hundreds of thousands of other families to flee.

This June 2025 photo shows some of the destruction in Beirut’s southern suburb caused by the Israel-Hezbollah war.

“The children were panicking, I was scared for my family and my relatives,” says Ms. Chahine.

The Lebanese Ministry of Public Health says up to one million people were internally displaced and more than 4,000 people were killed in Lebanon between 8 October 2023 and 22 July 2025. Israel and Hezbollah agreed to a ceasefire 27 November 2024.

However, in mid-October, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights reported the Israeli military remained in five positions along

the border and violated the ceasefire daily, killing 108 civilians since the ceasefire.

The Jamals and the Chahines were among more than 82,000 people in mid-October who were still displaced within Lebanon since the ceasefire.

“The war is not over,” says Mr. Jamal about his decision to stay in Nabaa. The bombardments blew out the windows and doors of his house in Qlayaa. “No one lives in our village: There is no electricity, no water, and the roads are frequently closed.”

However, living in the relative safety of Nabaa has cost these two families their financial stability. Mr. Jamal has been unable to find work, and Ms. Chahine’s husband is a day laborer. He earns between $200-$250 per month, but rent is $550, and the generator costs $125 monthly.

The Lebanese government cannot offer any support for internally displaced people, and those in need rely on local and international nongovernmental organizations, political parties, faith-based organizations and

“The church helped us to furnish the flat … They also provide us with food relief, school supplies and clothes.”

personal connections to help cover their shortfall.

The Jamals and Chahines are among 40 Christian families to receive support from the Sisters of Charity of St. Jeanne-Antide Thouret.

“The church helped us to furnish the flat,” Ms. Chahine says. “They also provide us with food relief, school supplies and clothes.”

Maronite Archbishop Charbel Abdallah of Tyre in southern Lebanon says almost twothirds of the 14,000 families attending the 18 parishes in his eparchy were displaced in autumn 2024.

“Those who are still displaced represent a minority who have often lost their houses,” he says. “In the border villages, the situation is critical, with many houses being completely destroyed. Other parishes farther away from the demarcation line are also badly affected.”

Melkite Greek Catholic Archbishop Georges Iskandar, B.S., of Tyre, whose eparchy includes 1,700 families across 12 parishes, says the homes of 28 percent of his parishioners were completely or partially destroyed by the war.

“Unemployment and poverty are reaching record-high levels, and many families are dependent on foreign aid,” he says.

In this context, with little to no support from the state and inaction from Hezbollah’s publicized compensation system, reconstruction efforts are based on personal means or private

Manal Chahine has been separated from her niece since she and her family fled the Israel-Hezbollah war in southern Lebanon for the outskirts of Beirut, where Sister Marie Azzi, top right, visits an elderly woman who also fled the south.

Since the Israel-Hezbollah war began in 2023, CNEWA-Pontifical Mission has worked with the Maronite and Melkite Greek archeparchies of Tyre, some 50 miles south of Beirut. As of October 2025, the agency has allocated about $1 million in food and essential packages, cash assistance and other necessities for families impacted by the war, including mattresses and infant formula, as well as fuel stipends across six villages, amounting to $74,000. CNEWA-Pontifical Mission has secured an additional $500,000 for the rehabilitation of churches and church buildings destroyed by the war.

To support CNEWA’s work in stabilizing Lebanon, call 1-866-322-4441 (Canada) or 1-800-442-6392 (United States) or visit cnewa.org/donate.

initiatives and stalled by daily Israeli attacks.

In Derdghaya, an Israeli airstrike destroyed the Melkite Greek Catholic church and parish hall that sheltered displaced people. However, Doha Chalhoub’s house still stands. Ms. Chalhoub shared her security and economic concerns with ONE in March 2024. Six months later, when the war escalated, she and her family fled.

The Israeli army “targeted the village right next to ours, we could hear the sound of the missiles,” she says. The family “left with nothing, except for our two birds that our daughters refused to leave behind.”

Ms. Chalhoub’s family returned to Derdghaya after the ceasefire

and found cracks in the walls of their home and other damage.

“We have water infiltration, we repaired one broken window, but four others allow for water to get in,” she says. “We had to replace our hot water solar heating system, as rocks fell on it during one bombardment.”

Derdghaya is located at an altitude of 1,350 feet and, at the time of publication, residents were preparing for winter with the meager resources on hand.

“Pontifical Mission helped us to buy some mazut to heat our home,” Ms. Chalhoub says. However, security remains her main concern.

“The drones are constantly above our heads,” she says. “Every

“ We hope for peace, we are exhausted.”

time we see one, we wonder if Israel will hit. We often hear the missiles and the bombing. We drive our daughters to school in the morning, hoping that nothing will happen that day.”

Tarek Mazraani, an architect from the border town of Houla, coordinates the Gathering of Residents of Southern Border Villages, an informal organization that reaches out to government ministries and relevant stakeholders to voice the concerns and needs of residents.

“The question of reconstruction is crucial but, immediately, people must be able to resume their lives,” he says. “Our first request is to receive compensation for the rent we need to pay, but also for health care expenses and tuition fees. It is urgent.”

The war worsened Lebanon’s already fragile economy. According to the World Bank, the economic cost of the war for the country reached “$14 billion, with damage to physical structures amounting to $6.8 billion and economic losses from reduced productivity, foregone revenues and operating costs reaching $7.2 billion.”

The economy in southern Lebanon, which relies on agriculture, especially on its olive and citrus groves and tobacco farms, has been unable to recover.

“Many olive trees have been uprooted by the Israeli army, and, for the third consecutive year, we have not been able to harvest the rest, due to bombardment and drought,” Mr. Mazraani says.

The Food and Agriculture Organization reports more than 2,000 acres of olive groves and nearly 1,600 acres of citrus groves were destroyed by the Israeli army.

According to local media reports, 39 Israeli attacks also targeted

“engineering and construction vehicles operating in south Lebanon” since the start of 2025. Twenty-two prefabricated municipal and residential buildings also were bombed, in what has been coined “the war on reconstruction.” On 11 October, an Israeli military strike destroyed 300 bulldozers and other reconstruction vehicles in Msayleh.

“They aim at bulldozers clearing the debris. They have destroyed schools, municipality buildings, pharmacies, gas stations, and have damaged the roads,” Mr. Mazraani says.

In October, the father of three, who is a Shiite Muslim, was also the target of an Israeli incitement campaign for demanding the right to return to the border villages. An Israeli military quadcopter flew above the village where he was taking shelter and broadcast a message over a loudspeaker to discredit him, calling him “a land

dealer” and urging residents to “drive him out.”

“Before this war, we used to live in our beautiful region, with our agriculture, our good schools, and all of this has now disappeared,”

Mr. Mazraani says, calling for domestic and foreign government support to “rebuild our livelihood and our heritage.”

One aspect of this heritage, he says, is religious coexistence: “We all live together — the Christians, the Sunni, the Shiite. We share the same history and the land is ours.”

The Christian community in southern Lebanon suffered significant losses. Fifteen churches across 10 villages were damaged by the war, along with rectories and church halls.

Israeli military airstrikes in Yaroun, a border village deeply impacted by the war, destroyed St. George Melkite Greek Catholic Church. A solar system was installed to generate electricity for the parish hall, where liturgies will be held until the church roof and walls can be rebuilt.

“The south is part of a holy land where Christ himself preached,”

Archbishop Abdallah says. “Staying in the south is a testament to our friendship with our Muslim brothers.”

While securing funding for reconstruction will be challenging “as long as the situation is not calm enough, as long as there is no peace,” he says, “we need to rebuild as soon as we receive funding.”

“It signals to the Christians and also to other communities that we will continue living in this village and on this holy land.”

The rebuilding and renovation concerns are not limited to southern Lebanon. According to the World Bank, approximately 10 percent of housing units across Lebanon were impacted by the war to some degree.

In Hadath, a town located in the southern suburbs of Beirut, André and Andy Eid’s apartment had suffered only minor damage throughout the 2024 escalation, when the Israeli army pounded the area. But in June 2025, a bombardment targeted the building opposite theirs, destroying their doors, cabinets and windows.

Their home is part of a Maronite social housing program in an area where the presence of the Shiite community has gradually expanded since the end of the Civil War in 1990 and where the presence of Hezbollah is strong. Their balcony overlooks at least four different buildings that were reduced to rubble by the Israeli army.

Two workers have come to take the measurements of their balcony and windows. “We are starting to be cold in the mornings, as autumn has begun now,” Ms. Eid says.

The minimal repairs are financed by the church; both husband and wife lost their jobs during the COVID-19 pandemic and rely on the church and on relatives to cover their needs, including those of their autistic son.

“We assisted the families that reached out to us with medicines and food, but our parish does not have the financial means to help rebuild all the houses,” says Cosette Nakhle, head of the social needs committee at Our Lady of Hadat Maronite Church in Hadath. To her knowledge, 10-15 households are still affected by the damage in the area.

“We are doing these renovations but are we going to be able to stay at home, or is a new war going to start?” Mr. Eid says. “We hope for peace. We are exhausted.”

Laure Delacloche is a journalist in Lebanon. The BBC and Al Jazeera have published her work.

One year after ceasefire, families in Lebanon are rebuilding their lives. Your gift shows them the church’s compassion and love can echo louder than any bomb. cnewa.org/donate

The Old Bridge in Mostar stood for centuries as the signature landmark of the largest city in the HerzegovinaNeretva Canton. It spanned the Neretva River, connecting the Catholic and Muslim neighborhoods on either bank — a symbol of friendship between peoples.

However, the fighting that erupted in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992 destroyed the iconic 16th-century bridge, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

For almost four years, the country’s three principal communities — the mostly Muslim Bosniaks, Catholic Bosnian Croats and Orthodox Bosnian Serbs — engaged in a civil war, triggered by Yugoslavia’s dissolution after the fall of the Soviet Union.

As different states of the former Yugoslavia declared their independence, the longstanding ideology of “Greater Serbia” — a vision to gather “all Serbs” into one state by absorbing territories beyond Serbia’s current borders — reemerged strongly. The Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence on 5 April 1992, and war ensued.

The human cost was shattering. Up to 101,000 people were killed or disappeared, more than two million were displaced — only one million eventually returned — and war-related sexual violence was widespread, estimated at up to 50,000 victims. The conflict left about 452,000 residential buildings — about 37 percent of housing at the time — partially or completely in ruins.

Mostar’s Old Bridge, which connects Catholic and Muslim neighborhoods on opposite sides of the Neretva River, was destroyed in the Bosnian war in 1992 and rebuilt in 2004.

Reconciliation is a work in progress in Bosnia and Herzegovina 30 years after genocide

text and photographs by Anna Klochko

The war, fueled by the collapse of the federal system, rising nationalism and competing territorial claims, brought sieges — including the yearslong siege of the Bosnian capital, Sarajevo — ethnic cleansing and mass atrocities, culminating in the genocide at Srebrenica.

In July 1995, the Srebrenica enclave — designated by the United Nations as a “safe area” — sheltered around 25,000 Bosniaks under the protection of the Dutch U.N. peacekeepers stationed there. When Serb forces advanced, the U.N. peacekeepers requested NATO airstrikes, but help never came and the Serb units entered the city.

From 11 to 15 July, they separated more than 8,000 Muslim

dipping with the land — a topography of loss turned to prayer. Each July, newly identified victims are laid to rest. This year, on the 30th anniversary, seven more were buried, bringing the total to 6,772.

Thirty years since the genocide, the wounds and trauma of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina remain. And not all Bosnians are united in their memory of the war, even as they work toward reconciliation and a lasting peace.

In Mostar, members of the Catholic, Orthodox and Muslim communities have been collaborating to rebuild their city. Bright murals now grace restored buildings, and the Old Bridge,

himself as Radmilo, was installing a marble mosaic on the cathedral floor. He and his Catholic Croat crew were racing to complete the installation by Christmas.

“When we take on a project, it doesn’t matter whether it’s Catholic or Orthodox,” he says. “We simply work together.”

It is daybreak when Mersudin Hasanovi rolls in from his night shift at one of the four border crossings with Serbia. He and his wife, Ismeta, rent several rooms on the upper floor of their home in Srebrenica. He exchanges pleasantries with his guests while Ismeta makes breakfast in the kitchen. The air hangs with the smell of eggs and strong coffee; on the table are fresh vegetables,

“Dialogue is the instrument of civilized people in their search for solutions.”

men and boys from the women and other children, then executed the men and boys and buried them in mass graves. The others were evacuated, although some women and girls were raped and killed as well. This mass killing stands as the only recognized genocide in Europe since World War II.

Four months later, on 21 November 1995, the Dayton Peace Accords were signed in Dayton, Ohio — later signed ceremoniously in Paris on 14 December — ending the Bosnian War and establishing a fragile peace.

Today, in Poto ari, a mere four miles from Srebrenica, the Srebrenica Genocide Memorial unfurls across soft, rolling hills, rows of white markers rising and

rebuilt in 2004, links the two banks of the city once more — a symbol of reconciliation.

The war damaged or destroyed Mostar’s places of worship, including Holy Trinity Serbian Orthodox Cathedral. The building remains standing, but resembles a shell, as the interior is largely unfinished. Regular liturgies have yet to resume. The progress since the restoration, started in 2011, remains uneven, hampered by intermittent funding and strict heritage regulations. Theft, vandalism and bureaucratic and political hurdles have stretched the timeline.

In September, the steady tap of hammers filled the nave. The supervisor on the job site, a Bosnian Croat who identified

homemade cheese, a crisp baguette and a spicy vegetable relish.

Mr. Hasanovi was 14 and living in Ra enovi i, a Bosniak village about 25 miles southeast of Srebrenica, when the war began. After feeding their livestock each morning, he and his family would “head into the forest to hide and survive the shelling.”

“We were heavily shelled from the Serbian side,” he says. “The Yugoslav People’s Army was effectively fighting the Bosnian Serbs.”

He clearly remembers 7 July 1992, the day he survived by a hair’s breadth. Soldiers across the Drina River — in what was then Serbia — opened fire at him and other Bosniak boys with a heavy anti-aircraft machine gun.

“It’s a strange feeling, hearing bullets whistle past and explode in the ground right beside you while you run as hard as you can,” he recalls. The following March, he fled Ra enovi i.

Before the war, he says, no one fixed on religious identity. “On our street, most were Muslims, but many men married Serb women. We were friends,” he says. But then, things changed.

“At first, they played on Serb fear and vulnerability, and that fed the surge of nationalism. Institutions split. Propaganda flipped reality,” he says. “In the end, there were no

real winners in the war, only a few profiteers.”

Mr. Hasanovi and his wife have not turned on the news in about 15 years. They and their two children watch only films and streaming platforms.

He describes Srebrenica’s cultural life today as vibrant. With international support, time and the community’s own work on trauma, the town is steadily moving away from its reputation as a place of unending grief and horror.

“When I came back in 2004, I still hated Serbs,” he says. “My uncle was killed in that war.

There was too much to carry. Then I realized it was destroying my health. I’m a believer. I believe everyone will receive what’s due, if not now, then later.

“You can’t build your happiness on someone else’s grief.”

In many towns, the families of victims live next to those believed to have perpetrated war crimes. While the war ended, the question of justice remains open.

Among those committed to peacemaking in the country is the minority Catholic community that

“I was there. I know how it was. The media and politicians keep playing with the facts.”

Journalist Ivan Kljajić talks with Amir and Sabina Zekić at their home in Sarajevo. At right, Orthodox Christian Željko Maksimović examines books in the library of the John Paul II Youth Center in Sarajevo.

makes up about 15 percent of the population.

“As Catholics, we believe that in Bosnia and Herzegovina — and everywhere people live in conflict or post-conflict realities — it is essential to preach forgiveness and reconciliation,” says Archbishop Tomo Vukši of Sarajevo.

“But beyond words, what matters even more is to bear witness in practice: to show, through concrete examples, that we have forgiven those who caused harm and that we want to build reconciliation among people.”

The archbishop serves on the national interreligious council with Muslim, Orthodox, Catholic and Jewish leaders. The council was founded in 1997 to promote dialogue, reconciliation and social cohesion.

“Overall, the trends in Bosnia and Herzegovina are positive,” he says. “There is growing rapprochement and cooperation, although misunderstandings do occur.

“I have often said: There is no morally acceptable alternative to dialogue. Dialogue is the instrument of civilized people in their search for solutions.

“This never excludes the application of just laws — that is the task of the state and those responsible for it. Yet on a personal, human, psychological and spiritual level, people need inner freedom,” he adds. “Some call it the liberation of memory, letting go of heavy remembrances.”

Reconciliation at a national scale is a complex process that extends beyond roundtables and chanceries.

Thirty years after the Bosnian War, the work of peace and reconciliation continues. Neighbors work together to rebuild trust. Religious leaders work on local councils. Each 11 July, the United Nations commemorates the International Day of Reflection and Commemoration of the 1995 Genocide in Srebrenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The work of seeking justice, peace and reconciliation through dialogue with “the other,” whether in Eastern Europe, Northeast Africa or the Middle East, remains a key component of CNEWA’s mission.

To support CNEWA’s work in advocating for peace and dialogue, call 1-866-322-4441 (Canada) or 1-800-442-6392 (United States) or visit cnewa.org/donate.

Sabina and Amir Zeki live in a neighborhood of detached homes in Sarajevo, the country’s capital, on the southern slope of Mount Žu , about eight miles north of the city center.

The hill overlooking the city was a strategic point during the war and the site of a battle, where the army of the newly formed Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina successfully repelled Bosnian Serb forces on 8 June 1992.

The Zeki family lived in Sarajevo throughout the war and the city’s nearly four-year siege. Today, the Bosniak couple rents out rooms in their home to travelers; inevitably, the two have become conversation partners on

the war. Many visitors pause in front of the building next door, pocked with shrapnel.

“A shell hit here,” Mrs. Zeki explains. “My father-in-law was killed. My husband’s sister was wounded. Everything was shattered and burned, but we rebuilt.”

As a hospital nurse during the war, she saw death, fear and despair she still finds difficult to discuss. A report by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia reports more than 9,500 casualties of the siege, while other sources list more, among them more than 1,000 children.

“During the shelling, we hid with our Serb neighbors,” Mrs. Zeki

“On a personal, human, psychological and spiritual level, people need inner freedom … Some call it the liberation of memory, letting go of heavy remembrances.”

recalls. “Then their son suddenly left ‘for the other side.’ Later the whole family emigrated to the United States and never came back. He was declared a war criminal. People said he had taken part in killings.”

Mrs. Zeki has worked with people of other faiths throughout her life — even during the siege.

“Where politics didn’t interfere, relationships stayed normal,” she says. “We didn’t understand why this war was needed. Ordinary people didn’t start it. It was politics. And when politicians decided to stop, the war ended.

“We still live peacefully now, but turn on the TV, and the split begins. Different channels tell opposite versions of events,” she continues. “I was there. I know how it was. The media and politicians keep playing with the facts.”

Mr. Zeki nods in agreement.

“I lost my father and three sisters,” he says. “Our family scattered. We stayed. Now I have my wife, my sons and a fragile peace. That’s what matters.”

In a country where religious affiliation was closely identified with violent conflict and atrocities, the separation of religion and state as foundational for peaceful coexistence enjoys broad support. According to a survey by the International Republican Institute in 2017, 79 percent of Bosniaks, 78 percent of Bosnian Croats and 79 percent Bosnian Serbs prefer a secular state.

However, a USAID youth survey conducted five years later found the greatest percentage of Bosnian youth, 42 percent, express the greatest trust in religious

The Srebrenica Genocide Memorial in Potočari commemorates the 8,000 Muslim men and boys killed and then buried in mass graves by Serb forces in 1995.

institutions over other public institutions, even though they remain critical of institutions overall.

Religious communities remain vital in Bosnian society, and it is precisely at the intersection of the secular and the religious that trust takes root.

The Archdiocese of Sarajevo’s John Paul II Youth Center has been forming young adults in interreligious dialogue and reconciliation since its founding in 2007. Father Šimo Marši says he conceived of the center as “a place where young people could meet, learn and build a future together regardless of confession.”

It draws young people of all faiths, hosting ecumenical and interreligious initiatives, from volunteer projects and training sessions to sporting events and field trips. Pope Francis visited the eight-story building in 2015, blessing it as a space of dialogue and hope.

Its flagship program, “Let’s Take a Step Forward Together,” is one of the region’s most successful interreligious initiatives. The center is developing youth outreach on social media and other digital platforms.

“We hold peace conferences, organize a Run for Peace, and support local projects where youth from different religions play on the same team. That builds trust,” says Father Marši , who also teaches in the Catholic faculty of theology at the University of Sarajevo.

This year’s run drew about 200 teens. Father Marši reviewed the results of the run with Željko Maksimovi , the project coordinator and a member of the Orthodox community.

“Our Orthodox youth center collaborates with the John Paul II Youth Center,” Mr. Maksimovi says. “Everything that creates a platform for meeting and dialogue

is in demand: joint sports, educational sessions, exchanges — what matters is doing something together.”

The activities are organized through schools and have strong parental support. Each year, the center publishes “Little Steps,” a collection of successfully completed initiatives.

“The most important thing is the encounter,” Mr. Maksimovi says. “At events like this, kids meet, talk and step over invisible boundaries. Dialogue is the key. Big steps start small.”

Despite public optimism, in private conversations — around kitchen tables, at markets, among friends — the same anxiety surfaces again and again: fear of a revenge cycle by one side or another. Propaganda feeds the desire for and the fear of retribution.

“It is hard to gauge how much the desire for revenge resides in particular people,” Archbishop Vukši says. “That, like forgiveness, is bound up with personal stories.”

“When we speak of forgiveness, we are not calling for the suspension of just laws or for leaving evil unpunished. Forgiveness and reconciliation free the conscience and the soul; they are striving for the good,” he says, underlining distinctions vital in the lengthy process of reconciliation.

“Justice belongs to the courts, the police, the law. Reconciliation is always the liberation of the heart.”

Anna Klochko is a multimedia journalist based in Kyiv.

Take a closer look at this story through

This year marks the 30th anniversary of Caritas Armenia. So much has changed since our early days.

When I look back at my 28 years with Caritas, I recall our first attempts to assist those who had lost all that was dear to them. A magnitude 6.8 earthquake hit in northern Armenia on 7 December 1988, killing up to 60,000 people, injuring about 130,000 more, and taking down homes, workplaces and places of worship.

People had lost trust and hope for the future, but they still preserved a sense of pride and dignity that prevented them from asking for help, despite the long list of debts they incurred trying to provide basic necessities for their families.

It took enormous effort for Caritas Armenia staff to explain that charitable organizations, such as ours, were founded specifically to help them out of a hopeless situation. Armenia declared independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, and two years later Azerbaijan imposed a blockade, causing additional hardships.

At that time, Caritas Armenia was still learning how to respond to sudden poverty and social exclusion, and how to help people cope with their struggles and care for their everyday needs for food, medicine and warm clothing. More importantly, we were still learning how just to be with those in need and to listen.

Over time, we understood our efforts would not be sustainable by offering emergency relief alone. With the support of our partners, we worked toward organizational development, introducing guidelines and regulations for project management and accountability. We developed long-term strategies and secured budgets for project

implementation. We created durable programs: day centers and home care for the elderly; after-school activities and psychosocial support for children; tuition support for students whose parents fell ill or were unemployed.

The needs have shifted over the decades. However, the call for the charitable arm of the Catholic Church in Armenia has remained the same: to promote the dignity and development of people and communities, especially the most vulnerable, with love and compassion.

We coordinate our activities with the local church, so that a family in a border village is not invisible and a grandmother living alone in a city is not forgotten. Our parishes are small gateways of mercy; the priest knows the names and needs of every villager, and devoted young adult volunteers check on neighbors who live alone.

We collaborate with the wider Christian family [most Armenians belong to the Armenian Apostolic Church] and with local authorities and civic groups, because love does not ask for exclusivity; it asks for effectiveness. The first knock on a struggling family’s door is often from a Caritas staff member or volunteer of the local parish, carrying not only assistance but also the assurance, “You are not alone.”

Our day centers and home care services for seniors have taught me that “care” often means restoring the ordinary. We help with medications and meals, but we also rebuild daily rhythms that illness and isolation erode: a hot lunch at the same table, light exercise and a craft class, a blessing from the pastor on religious feast days and warm conversations on Christian and human values.

In home care, our nurses and caregivers carry not only bandages and glucometers; they offer a listening ear and empathy to a lonely senior. An elderly man once told me: “You bring the clinic to my living room — and you bring the light, too.”

It is humbling to witness how a reliable visit, a safe space heater or an evening phone call can turn anxiety into peace. The elders we serve built this country through hardship. They should not have to choose among medicine, heat or food. Much of our work is simply making that choice unnecessary.

Another Caritas project — The Little Prince Center — is where my hope is renewed again and again. When children first come to the after-school center, they are often quiet, sometimes withdrawn. Over months they find their voice, their equilibrium, their way of learning. Our team blends therapies with play, invites parents to learn alongside their children, and works with schools, so that inclusion is not a theory but is made concrete, with a timetable and a seat at a school desk. I think of a boy who would not enter the classroom without holding his mother’s hand. After several months of coordinated work by the multidisciplinary team, he now enters by himself, saves the chair next to him for a new friend, and shows interest in the program and trust in his teachers.

Education weaves through much of our work. The tuition program rarely covers large amounts, but it can have a decisive impact. I often

An Armenian woman holds bread from Aregak Bakery, a project of Caritas Armenia’s Emili Aregak Center in Gyumri, which provides resources and support for youth with disabilities and their families.

Caritas Armenia, bringing light to homes for 30 years

In Armenia, we say to those who stand with us during hardships, “You brought light to my house.”

In Gyumri, Caritas Armenia offers children meals, after-school activities and psychosocial support at the Little Prince Center, top photos, and operates a senior day center, where the elderly can socialize, rest and find support.

think of these grants as gifts of time: We buy the student’s family a little time to regain its balance, so a child’s future is not sold to pay today’s bills.

Winters in Armenia are severe and demanding, and our “warm winter” program undoubtedly has saved lives — what began as emergency deliveries of coal and firewood have become a broader effort to reduce energy poverty. In some homes, we help install insulation and fund simple energy-related repairs; in others, we pair assistance with paying the utility bills.

Our improved case management in recent years has ensured that when someone comes to Caritas with a problem, we take a comprehensive approach to assessing the wider picture, and we walk with them across programs, instead of handing them a phone number and wishing them luck. We have expanded psychosocial support, because trauma and loneliness rarely show up on an intake form.

Thirty years on, our three most urgent needs include protecting the dignity of our elders, a growing number of whom live alone on fixed incomes, while prices rise and their children emigrate for work abroad. We must ensure their homes are warm, their medicine is taken as prescribed, and their days include companionship.

Second is the inclusion of children and youth who risk being left behind, especially those with disabilities, from vulnerable families or in rural areas where services are limited or absent. Inclusion requires therapists, trained teachers, adaptive materials and a patient community.

Third is the quiet crisis of mental health. Anxiety, grief and isolation are widespread. The church has a unique capacity to respond here, joining professional care with spiritual companionship.

Alongside these, we face organizational challenges familiar to many church-run social service charities, namely keeping trained staff when salaries elsewhere are higher, serving hard-to-reach communities with consistency, and balancing urgent aid with the long work of prevention.

Through it all, the church’s answer through Caritas remains the same: presence, prayer and practical love, shaped now by three decades of learning. We design programs by listening to families and communities; we measure results, because accountability honors our donors and our people, and we invite those we serve to be part of the solution.

In addition to describing our work, I also write this letter to thank the CNEWA community, which has stood with us for many winters and many new beginnings. Because of you, a widow in a border village will receive a nurse’s knock at her door tomorrow morning; a young girl will sit at her desk in a classroom and find her voice; a university student will register for another semester; a family will greet the cold with confidence instead of dread.

The needs are real, but so is the grace that meets them. In Armenia, we say to those who stand with us during hardships, “You brought light to my house.”

Your light has multiplied hope in countless homes. For that — and for your prayers — we are deeply grateful.

Anahit Gevorgyan is the programs and institutional development manager for Caritas Armenia.

In the desert mountains of Syria, new life springs forth at an ancient monastery

by Claire Porter Robbins

The ancient monastery of Deir Mar Musa clings to the pale red face of a rock formation in Syria’s Qalamoun Mountains, exuding a quiet peace.

Isolated in the desert heights an hour north of Damascus, the last approach to the monastery can be done only on foot, climbing a grueling set of stairs carved into the rock.

Tourists and pilgrims have started returning to experience the monastery’s tranquility, now that the country’s 14-year civil war — marked by strife that killed more than 600,000 people and injured millions more — has ended. The monastic community

also suffered during the war — losses that have sharpened, rather than diminished, its unique mission.

The contemporary history of the monastery began in 1982 with Italian Jesuit Father Paolo Dall’Oglio. While studying Islam and Arabic in Damascus, Father Dall’Oglio explored the ruins of the long-abandoned sixth-century Syriac monastery. Deir Mar Musa al-Habashi was dedicated to St. Moses the Ethiopian, who had converted to Christianity in Egypt after being dismissed as a slave of an official for choosing a life of crime and debauchery.

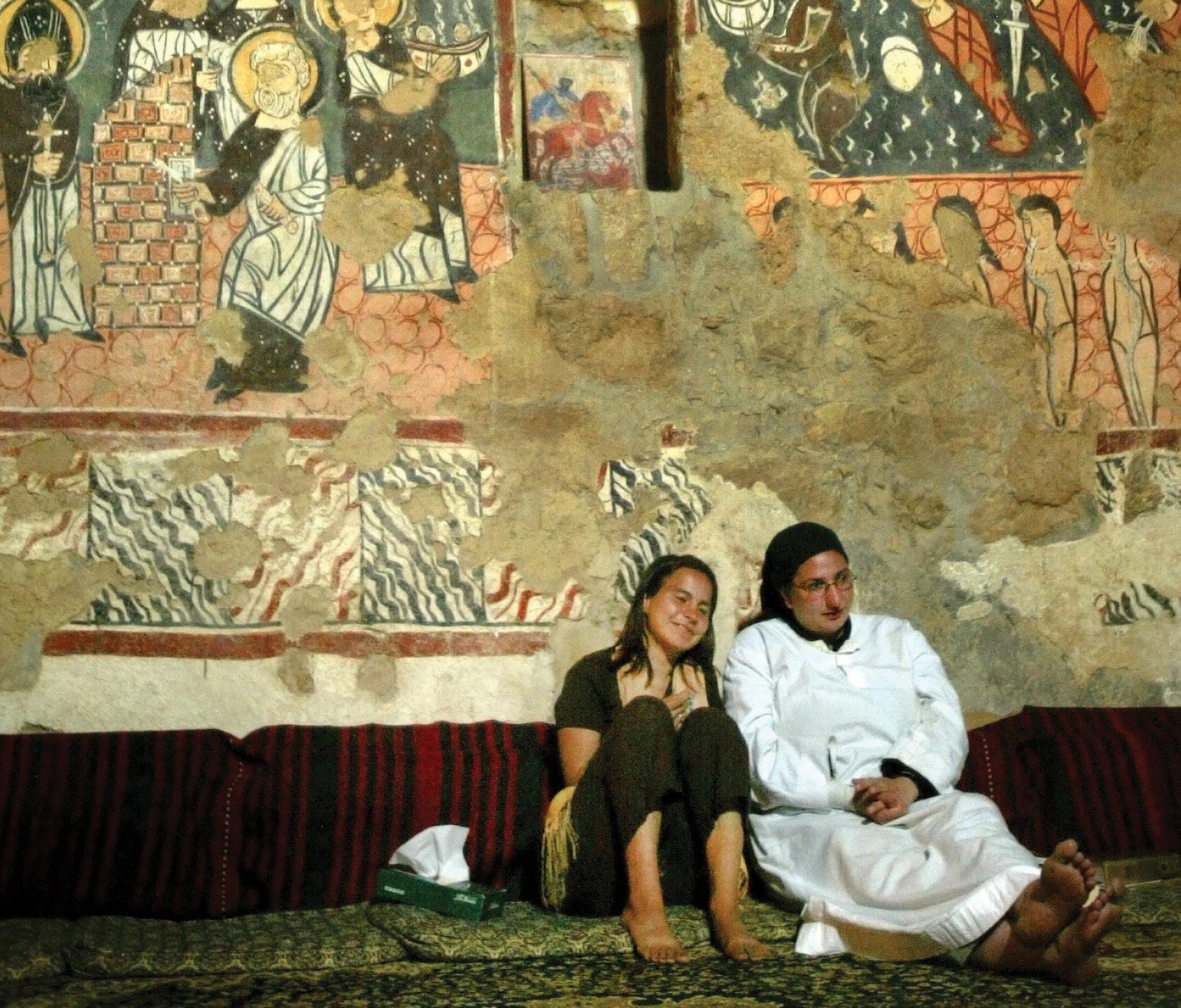

Father Dall’Oglio was captivated by the solid 11th-century structure, with its prominent 12th-century tower, simple dormitories that overlook the Syrian plains, and small chapel with 11th- and 12th-century frescoes depicting Christ’s baptism, the martyrs Sts. Barbara and Juliana of Nicomedia, and the apostles.

For centuries, the frescoes had been exposed to desert winds and

Father Jihad Youssef prays in the chapel of Deir Mar Musa, a historic Syriac Catholic monastery dedicated to promoting peace and interreligious dialogue.

neglect. With the help of archaeologists, art historians and volunteers over several years, Father Dall’Oglio secured roofs, repaired walls and restored the fragile images, ensuring they could speak again to a new generation of pilgrims.

Father Dall’Oglio’s vision for Deir Mar Musa extended beyond the restoration of an ancient church to the founding of a new monastic community dedicated to peacebuilding and dialogue with Muslims in the heart of the Levant.

Father Jacques Mourad, now the Syriac Catholic archbishop of Homs, joined Father Dall’Oglio in this mission of prayer, work, hospitality and interreligious dialogue; they formed a stable monastic community in 1991. The community was named al-Khalil, the Arabic honorific for the Hebrew patriarch Abraham, the father of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, known for his hospitality. Soon, visitors of all faiths from around the world began to arrive.

The allure of Deir Mar Musa is the feeling of “freedom in the desert … open like the heart of God,” said Archbishop Mourad.

For years, the monastery thrived as part of the local community, making inroads in Christian-Muslim relations and poverty-alleviation efforts, especially in neighboring al-Nabk.

To some, the community’s relationship with Islam was unorthodox. Archbishop Mourad said even he at first struggled occasionally with Father

The allure of Deir Mar Musa is the feeling of “freedom in the desert … open like the heart of God.”

Dall’Oglio’s vision to love Islam and its adherents as part of their monastic call to follow Jesus and live out the Gospel. The monastery’s mission “is not easy to understand,” the archbishop said, but it is to be “a testimony of the love of Jesus for the Muslim community.”

“If you love those who refuse to love you back, this is the testimony of Christ,” he said. The charism later expanded, with new monastic foundations in Sulaymaniyah, Iraq, in 2012, and Cori, Italy, in 2013. Currently, within the al-Khalil community, there are two monks, two nuns and two novices; in Iraq, there is one monk and one nun; and in Italy there is one nun.

Al-Kahlil’s mission of hospitality unfolded in a country where political subjugation under the regime of Bashar al-Assad ran deep. However, the repression came to a head in 2011, when the Arab Spring arrived in Syria, prompting a swift and cruel crackdown by the government.

Fighting between rebels and government forces plunged the country further into violence.

Father Jihad Youssef, the current abbot, said fighting was close to the monastery during the Battle of al-Nabk in January 2013. Army helicopters circled overhead, monitoring the monastery and bombing nearby.

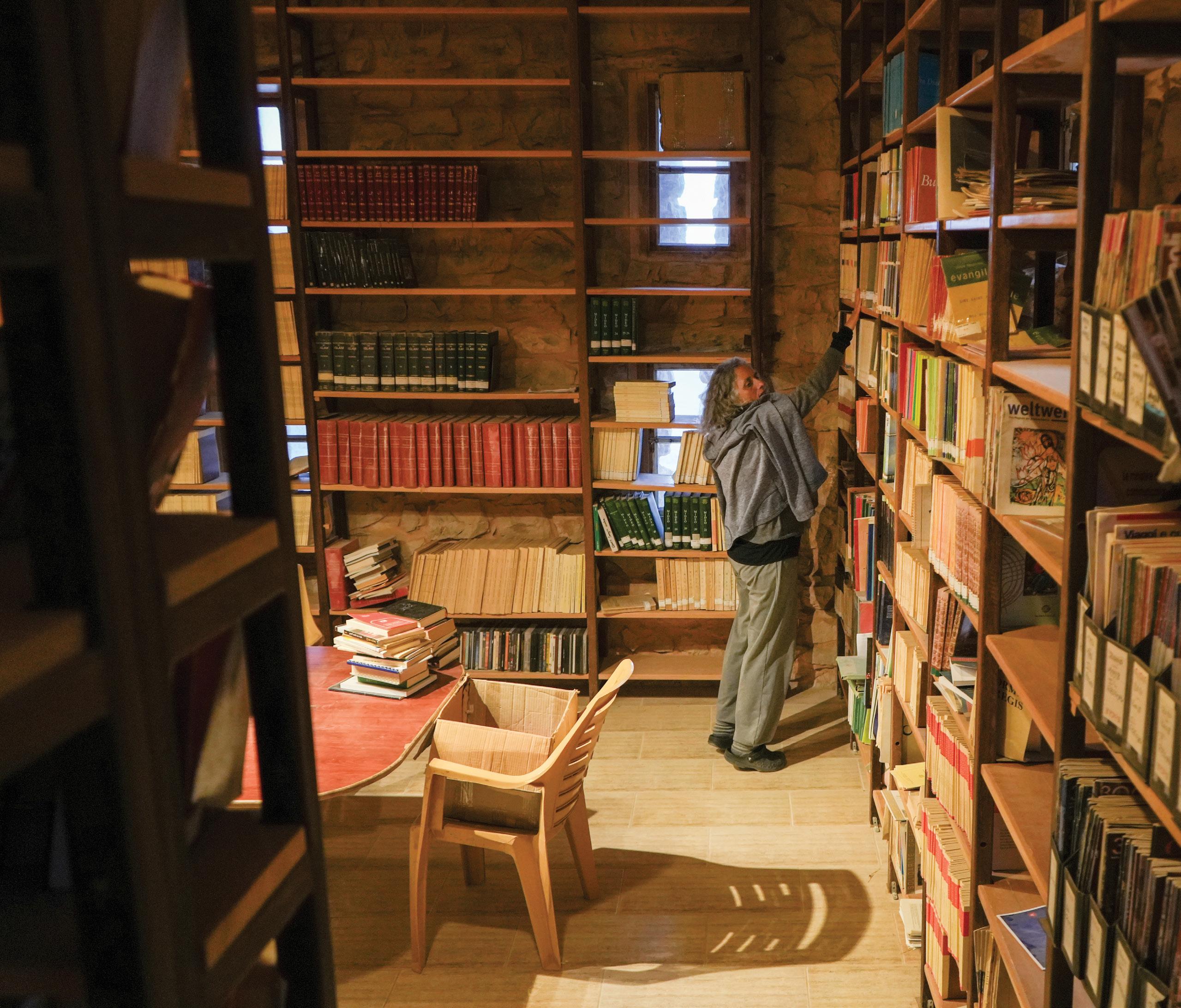

Sister Carol Cooke-Eid, a German-born member of the

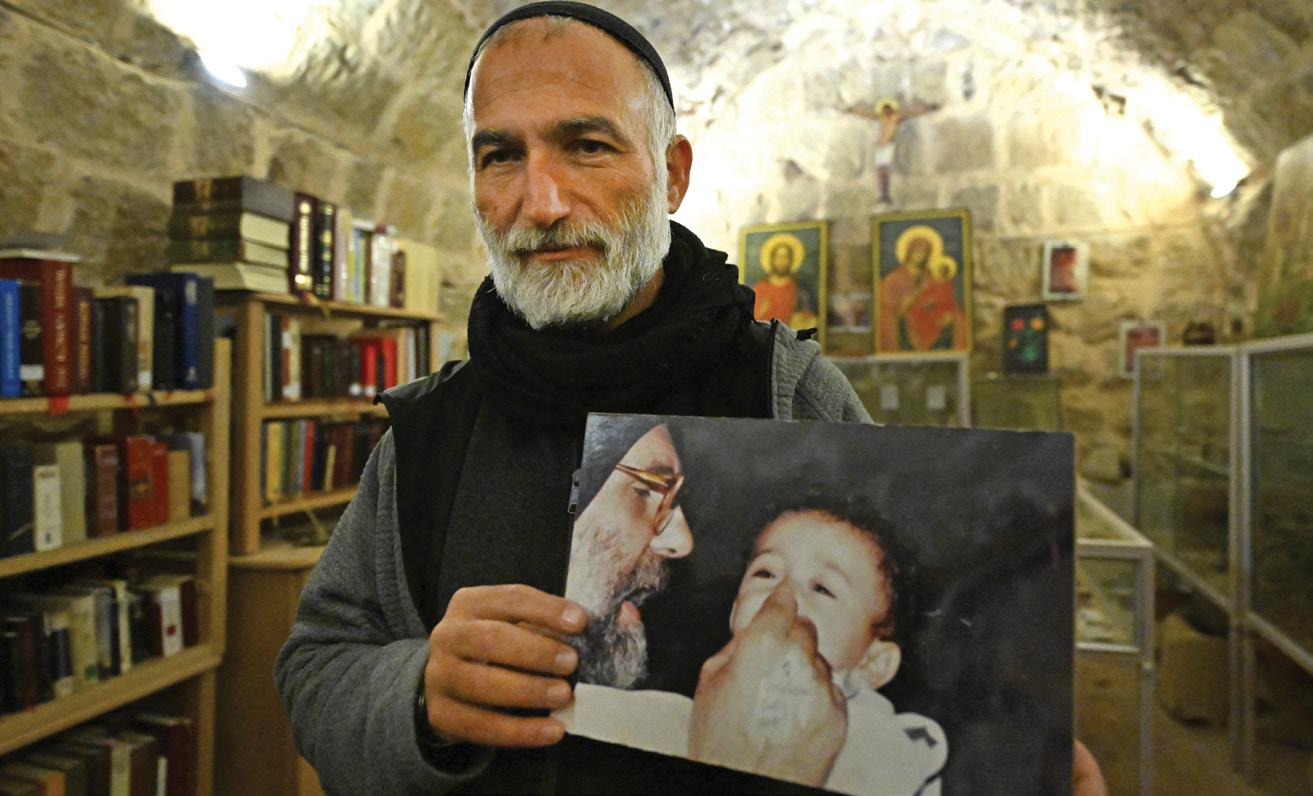

Sister Carol Cooke-Eid reaches for a book in the monastery library. Opposite, Father Jihad Youssef, the current abbot, holds an image of Father Paolo Dall’Oglio, S.J., who re-founded the ancient monastery in 1982. Father Dall’Oglio was abducted by ISIS in 2012 and never seen again.

After a brutal 14-year civil war and the emergence of a new government, Syrians are seeking ways to rebuild and return to normalcy. An important step is recreating a sense of social cohesion and healing through efforts that promote peace, interreligious dialogue and reconciliation. CNEWA remains committed to supporting the church’s many initiatives in restoring and rebuilding Syria. These initiatives, like the programs offered by the monastic community at Deir Mar Musa, are open to Syrians of all faiths and creeds.

To support CNEWA’s mission in Syria, call 1-866-322-4441 (Canada) or 1-800-442-6392 (United States) or visit cnewa.org/donate

monastic community, said the monastery went from about 50,000 visitors in 2009 to just a handful by 2013. As a result of the al-Nabk battle, residents went months without electricity or access to cell phone service, and no one was able to travel safely. The emergence of Islamic State (ISIS) presented a clear threat of violence to the community as well. ISIS took advantage of growing instability in Syria to carry out attacks in pursuit of a caliphate. It targeted religious communities and showed violent contempt for Christians. Despite the challenges, al-Kahlil continued during the civil war, although on a smaller scale, to offer respite, hospitality and opportunities for dialogue.

Father Dall’Oglio felt the need to speak up amid the violence and repression, and he published an article in support of government protesters. The government in turn ordered his expulsion in 2012. He left and found refuge in Italy and in Lebanon.

However, Father Dall’Oglio returned in July 2013 through Raqqa, northern Syria, to negotiate the release of friends from a group identified as Islamic State. He was never seen again and is presumed dead, although his remains have yet to be found.

Father Mourad, then pastor in the Syrian town of Qaryatayn, where he was working to restore the Mar Elian Monastery, mourned the loss of Father Dall’Oglio, whom he had

Christians should be

“the cement of the mosaic of Syria.”

described as his “closest friend until the end.”

Soon after, the historic Christian community of Qaryatayn was targeted and, in May 2015, ISIS kidnapped Father Mourad and a deacon. They were held in Raqqa for almost five months, experiencing physical and psychological torture, before being transported to Palmyra, where 250 of Father Mourad’s parishioners also were held prisoner. Eventually, they were released back to Qaryatayn under

the surveillance and rules of Islamic State, which had destroyed the Mar Elian Monastery that had been carefully restored.

He said the brutality he experienced deepened his faith as well as his love for his Muslim neighbors, who were the first to bring meals to him and his parishioners upon their return to Qaryatayn. Neighbors also later risked their lives to smuggle Christian girls and, eventually, Father Mourad, out of the community.

With the equilibrium restored with the retreat of Islamic State, Syrians started visiting Deir Mar Musa again. Nouhad Dergham first traveled to the monastery in 2009 with her parents and met Father Dall’Oglio. However, it was only as an adult, when she became interested in meditation and in the priest’s writings, that she visited again.

Ms. Dergham, now a young mother living on the outskirts of Aleppo, works with the monastery

to compile and translate Father Dall’Oglio’s works. She also participates in the monastery’s efforts to “widen the space of our tent” by involving laypeople.

She said what she treasures most about al-Khalil is it “never presented itself as perfect, or as a ‘chosen community.’ They have always been vulnerable and accepted themselves as being at the will of God.”

Having emerged from years of darkness, the al-Khalil community has recommitted to its vision of hope and dialogue. It has restarted hosting events, from Ramadan retreats to visits by international groups, including foreign journalists, now returning to Syria since the civil war ended.

Visitors are greeted with warm bowls of “mulukhiyah,” a traditional jute stew on rice, topped with lemon. A day at Deir Mar Musa is bookended by worship in the chapel at sunrise and sunset. The time between prayer is filled with work — tending to the animals, cleaning the facilities, growing vegetables or studying in the cavernous two-story library with numerous titles on Islam and Christianity.

dialogue to his archeparchy. Last year, he approved the entirety of the monastic constitution written by Father Dall’Oglio; it had obtained the nihil obstat from the Holy See in 2006.

In late July, he celebrated a memorial outdoor liturgy for Father Dall’Oglio at the end of a four-day interreligious event at the monastery on ways to heal after Syria’s civil war. The liturgy was the first public opportunity in Syria to honor the priest’s life.

In speaking with ONE, Father Youssef acknowledged the immense loss the country experienced during the country’s civil war. In 2012, Syria had about 1.5 million Christians, representing about 10 percent of the population; by 2022, that number had fallen to about 300,000.

He also described last year’s coup of the Assad regime and subsequent change in the Syrian government as “a golden opportunity” for the country to rebuild a peaceful and equitable state. Without the Assad government’s repression, and with the transitional government pledging to support democracy, interfaith dialogue might finally take place on a broader scale, he said.

cnewa.org/donate In this 2005 file photo, a Catholic laywoman sits beside a Syrian Orthodox nun during prayers in the chapel of Mar Musa monastery.

Over the years, only a handful of visitors have embraced a monastic vocation at Deir Mar Musa. Others have discovered “that their vocation was elsewhere — in marriage, with another religious community, in the diocesan priesthood, and so on, and these have left here happy and consoled, praising God,” says the community’s 2023 Christmas letter.

Despite his episcopal charge, Archbishop Mourad remains involved with the monastery and brings its vision of interreligious

Father Youssef was also hopeful those who were displaced will return to participate in this rebuilding, despite the concerns of violence against minority groups, such as the June suicide bombing at a Greek Orthodox church in Damascus during Divine Liturgy.

“We need social cohesion,” he said, and Christians should be “the cement of the mosaic of Syria.”

Claire Porter Robbins is a freelance journalist and former aid worker who has worked in the Middle East and the Balkans.

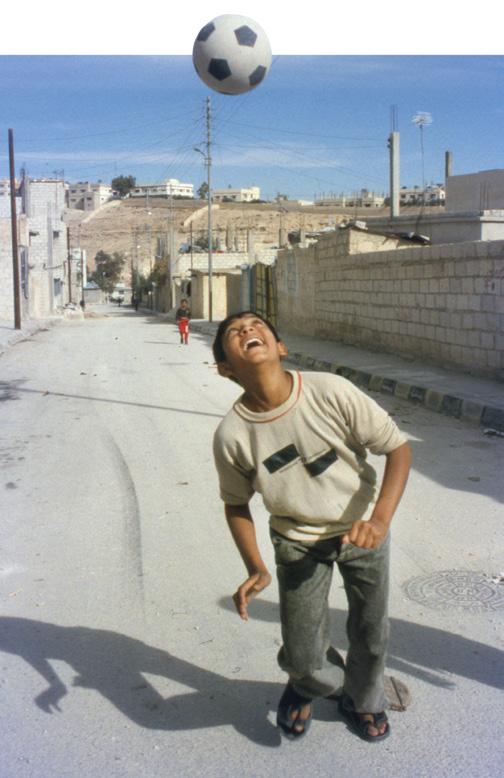

Palestinians brace for more restrictions, land confiscations under Israel’s new settlement expansion plan

In Abu Nuwar, five miles east of Jerusalem, the voices of children playing outside spill into the small kindergarten classroom of 40-year-old teacher Jihan Frehat. Just beyond the schoolyard, the red roofs of Ma’ale Adumim extend farther across the hilltop each year.

Ma’ale Adumim, with a population of 38,000, is an Israeli settlement built on expropriated Palestinian land. It is one of four settlements, including a nearby military base deemed illegal under international law, that encircle the Palestinian hamlet in the West Bank.

Born and raised in the 900-member Bedouin community of Abu Nuwar, Ms. Frehat runs through the daily pressures: Israeli military raids, home demolitions, settler incursions, blocked farmland and road closures that touch every aspect of life.

Ms. Frehat, who taught previously in private West Bank schools and with the Norwegian Refugee Council, co-founded the kindergarten, which currently serves 23 children, in 2011. It is under an Israeli demolition order, as is the middle school next door, which serves about 75 students. The latter was already demolished by Israeli forces five times. Each time, residents have rebuilt with help from local and international organizations.

“The ones who suffer most are our kids,” says Ms. Frehat. “When we were their age, we didn’t think about displacement or annexation. Today, they do.”

Clockwise, from top left: Photos of a Palestinian child in a kindergarten class in Abu Nuwar, West Bank, Atallah Mazaar’a, spokesman for the Bedouin community of Jabal al-Baba, and a Palestinian child riding a bike in Abu Nuwar surround a drawing of a family in a house, topped with the Palestinian flag.

In contrast, Ma’ale Adumim looms over Abu Nuwar with “all the advantages of a city,” including a diverse education system, transit, health care, cultural and sports centers, parks and a lake, according to the website of Nefesh B’Nefesh, which partners with the Israeli government to recruit new residents for the settlement.

“Look at how much the settlements have grown, look at their schools and universities,” says Ms. Frehat, gesturing toward the expansive gated community.

“Now, look at us. Maybe they will close our schools, this is the policy of making us illiterate,” she says. “All I want is a safe, secure, peaceful future for my children. I still have hope.”

The skyline heralds Israel’s E1 settlement expansion plan to connect Ma’ale Adumim to Jerusalem with a continuous settlement bloc in what Israel calls the E1 corridor, short for East 1. The plan had advanced and stalled under international pressure since 2005, but it was approved for rollout by the Israeli government in August 2025.

A month later, Israel’s government approved a $900-million plan to build 7,600 new housing units in Ma’ale Adumim; settlement monitors estimate roughly 3,400 of those units will be built inside the settlement corridor.

Situated in the Israeli-occupied West Bank — representing 60 percent of the territory, also known as Area C, under the terms of the 1995 Oslo II Accord — the 4.6-square-mile corridor includes about 7,000 Palestinian residents across 22 Bedouin communities, including Abu Nuwar. These communities are at risk of forcible transfer to clear space for settlement expansion.

Ms. Frehat recalls the 1990s, when settlements were in an early

Since 2002, the Israeli separation wall has isolated Palestinian West Bank communities and key religious sites, separated religious congregations from the communities they serve, and restricted freedom of movement for locals and pilgrims. The Israeli government’s plans for the E1 corridor, approved in August, would worsen these conditions, says Joseph Hazboun, CNEWA’s regional director for Palestine and Israel.

“The E1 project threatens to close the only remaining road connecting Eizariya to Jerusalem, leaving these religious communities and local residents uncertain about their future,” he said. “Without this vital link, how will the Comboni Sisters, for instance, continue their mission of providing education and medical aid to Bedouin communities?”

He said this development also “raises serious concerns about the preservation of these sacred sites and the communities that sustain them.”

To support CNEWA’s work in the Holy Land, call 1-866-322-4441 (Canada) or 1-800-442-6392 (United States) or visit cnewa.org/donate

stage, far from the chokehold she describes now.

“We’re living on the edge now,” she says. “At any moment I could receive a demolition order and be forced from my home. Honestly, we know nothing but fear. We fear annexation and our unknown future.”

“The questions that we ask are: What will happen to us? Where do we go?”

Advancing the settlement plan would have broad implications across Palestinian territory and further “Israel’s unlawful policy of annexing, de facto, the Palestinian territory and prevent the viability and contiguity of a Palestinian state, violating the Palestinian people’s right to selfdetermination,” says the International Commission of Jurists.

A Palestinian kindergarten teacher carries a child in Abu Nuwar. At right, a Palestinian looks toward the Israeli settlement of Ma’ale Adumim.

In Bethlehem, the Rev. Mitri Raheb, Lutheran pastor, theologian and founder of Dar al-Kalima University, says the E1 expansion plan would “fully” sever the West Bank’s north from its south, “erasing the territorial continuity.”

The Israeli government’s plans intend to “make sure that no Palestinian state will ever be created,” he says.

Israeli Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich indicated as much in a statement in mid-August, saying the plan was “a significant step that practically erases the two-state delusion and consolidates the Jewish people’s hold on the heart of the land of Israel.”

Palestinian communities inside the E1 corridor face the risk of forced displacement, driven by state-backed settler violence, military action and planning policies. Settler violence has increased since the start of Israel’s war on Gaza in October 2023, along with military raids, checkpoints and job losses in Palestinian cities and towns across the West Bank.

On the borders of Jabal al-Baba, or Pope’s Hill, a few miles from Abu Nuwar, Palestinians are familiar with Israel’s policy of forced displacement.

“Every time we rebuild, they come with new decisions,” says Atallah Mazaar’a, the spokesman for the hilltop community.

Mr. Mazaar’a is located within the Bedouin community residing on the borders of the Vatican’s Jabal Al-Baba Hill, a gift from the late King Hussein of Jordan to Pope Paul VI during his historic visit to Jordan and the Holy Land.

The pressure has been measurable: The U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reports that, in August, Israeli authorities issued demolition orders for 20 structures in the community, housing 450 people.

Cumulatively since 2009, more than 500 Palestinian-owned structures in E1 communities have been demolished, displacing more than 900 people. The average monthly demolitions this year, from January to mid-October, was eight.

Meanwhile, settlement expansion has accelerated. As of August, more than 23,000 Israeli housing units had advanced, putting Israel on pace to approve over 50,000 by the end of the year, more than the previous five years combined, according to the Israel Policy Forum.

Within the broader settlement network, there are some 370 settlements and outposts across the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, housing more than 737,000 settlers. Many function as

cities and are integrated into Israel’s road network, allowing settlers to travel freely between Israel and the West Bank.

According to the Israeli human rights group B’Tselem, Israeli building policies are “aimed at preventing Palestinian development and dispossessing Palestinians of their land,” as part of a broader political agenda to “maximize the use of West Bank resources for Israeli needs, while minimizing the land reserves available to Palestinians.”

“ I think only about today. Everything else is in God’s hands. ”

“It is our duty to stay steadfast on our land and to hold onto it until our last breath.”

Mr. Mazaar’a frames the pressure as demographic engineering: “to change the demographics according to their aspirations … making settlers outnumber Palestinians in Jerusalem, extending all the way to the Dead Sea.”

“We want to develop and build,” Mr. Mazaar’a says. “Our existence as Bedouins is for nature, and complementary to it, through our livestock and the land we preserve. We are part of the Palestinian national fabric.”

“For us, this land is our oxygen.”

Mr. Mazaar’a says pushing back against the Israeli occupation used to be easier, but the Israeli military has grown significantly more brutal in the West Bank since Israel’s war on Gaza began and peaceful protest has become increasingly dangerous.

“They used to break up protests with tear gas or sound bombs,”

Mr. Mazaar’a says. “Nowadays, they are willing to destroy and even kill.”

Since October 2023, Israeli forces have killed 1,001 Palestinians in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem — about one in five of them children — accounting for 43 percent of all Palestinians killed in the West Bank over the past two decades. As well, 7,500 military raids were recorded across the West Bank from January to October 2025, a 37 percent increase over the same period in 2024, according to OCHA.

Fearful for their lives, activists have stopped their activities, and many Palestinians believe their only remaining defense is to stay put and refuse removal, in some cases even declining the incentives of “huge amounts of money, pieces of land” elsewhere, Mr. Mazaar’a says.

Palestinians refuse to accept this “new Nakba,” he adds, referring to

Palestinian children attend a kindergarten class in Abu Nuwar, West Bank.

the Israeli expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from the Negev in 1948.

“The occupation displaced me and my family in 1948. We still have our keys and the deeds to our land,” he said. “I would never accept leaving unless it is to return to my land in Bir es-Seba,” since renamed Beersheba.

Mr. Mazaar’a’s position is grounded in his Muslim faith as much as in political principles.

“We are on holy land,” he says. “It is our duty to stay steadfast on our land and to hold onto it until our last breath.”

The E1 expansion intends to reorganize the West Bank through a split road system that would reserve the main

“At any moment I could receive a demolition order and be forced from my home.”

corridor for Israeli-plated vehicles, and shift Palestinian traffic to a peripheral bypass, increasing Israeli connectivity while further isolating Palestinian communities.

While The Times of Israel has reported that the Israeli prime minister has called the planned road a “strategic transportation corridor,” connecting Jerusalem to Israeli settlements, human rights groups have dubbed it “the apartheid road.” Palestinians are routed through underpasses and tunnels “like rats,” Rev. Raheb says, as settler-only bypass roads link Israeli hilltop communities overhead. He says a gate would be installed on the new road “so that Israel can close it at any time,” as with other separation roads in the area built on the same model.

He says the goal is to confine Palestinians to reservations — akin to those created for Indigenous communities in North America — while exclusive Israeli settlements expand around them, turning freedom of movement from a right into a privilege.

Rev. Raheb says the Israeli government is moving to annex more than 80 percent of the West Bank, confining Palestinians to about 18 percent of the territory, fragmented into densely populated, noncontiguous enclaves, such as Ramallah, Bethlehem, Hebron and Nablus, each ringed by dozens of Israeli automated gates.

Over time, severed Palestinian regions will develop different needs, even identities, similar to “what happened when Gaza was cut off,” he says. Without territorial continuity, authorities can manage isolated pockets through local “chiefs,” restrict access to resources, and let those areas slowly dry out, further entrenching the separation and isolation underway.

Ancient Christian pilgrimage routes linking Jericho, Jerusalem and Bethlehem have been threaded between Israeli military checkpoints and the separation wall for decades. Palestinian passage often hinges on Israeli permits and arbitrary checkpoint openings and closures.

Life under Israeli occupation has caused many Palestinians to flee, including from the already dwindling Christian population. Since the start of Israel’s war on Gaza, around 147 Christian families have left Bethlehem, says Rev. Raheb, who added that if current conditions persist, he expects more families will leave, and the churches risk emptying of their local congregations.

“Palestine is the cradle of Christianity,” he says, “not a theme park.”

Leila Warah is an independent multimedia journalist in Palestine.

Perspectives from the president by Msgr. Peter I. Vaccari

“If I, therefore, the master and teacher, have washed your feet, you ought to wash one another’s feet. I have given you a model to follow, so that as I have done for you, you should also do.” (Jn 13:14-15)

On Monday, 20 October, His Beatitude Patriarch Raphaël Bedros XXI Minassian, along with several other Eastern Catholic patriarchs, eparchs and priests, offered an evening liturgy of thanksgiving at the Altar of the Chair of St. Peter in the apse of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

A large gathering of consecrated women and men, deacons, seminarians and lay faithful were present. They had traveled to Rome during the jubilee year to witness Pope Leo XIV canonize seven saints the day prior. Thousands of people had gathered in St. Peter’s Square and down the Via della Conciliazione for the canonizations. Included among the new saints was a martyred Armenian archbishop, Ignatius Maloyan, a victim of the Armenian genocide in 1915.

I reference these powerful events I was privileged to attend because on one side of the historic wooden chair — encased within Bernini’s bronze monument, completed in 1666 and recently restored with funding from the Knights of Columbus — is a bas-relief depicting Jesus washing the feet of his apostles (cf. Jn 13:1-17).

Permit me to suggest that as CNEWA prepares to enter its second century of service in 2026 — and St. Peter’s Basilica prepares to celebrate the 400th anniversary of its consecration — the great challenge is not a matter of magnificent structures, but rather of a renewed awareness of the fundamental call to holiness through servanthood and the daily washing of the feet of others.

Are we not called to learn from our past, to recognize our limitations and failures, to build on the extraordinary goodness and accomplishments due to our cooperation with God’s grace alone, and to keep our eyes fixed on the future?

Are we not called, as a papal organization, to expand the embrace of our mission, expressed metaphorically by the architectural “embrace” of the colonnade in St. Peter’s Square?