CARNEGIE MELLON ENGINEERING

Introducing the world’s smallest powerautonomous bipedal robot, at only 3.6 cm tall. It is also the fastest biped, in terms of leg lengths per second!

Small, centimeter-scale robots have the potential to excel at traversing tight spaces found in industrial facilities, natural cavities, and disaster debris, allowing for inspection and exploration tasks typically inaccessible to robots with larger footprints.

The robot has rounded feet, with a single motor at the hip. It can passively stand without any actuation and is capable of moving over rough terrain and turning, skipping, and ascending small-scale steps.

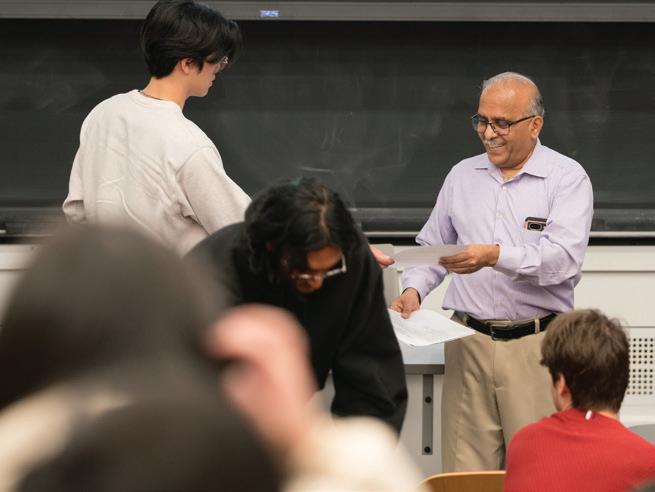

From the labs of Aaron Johnson and Sarah Bergbreiter, their research has inspired autonomous walking robots with noteworthy efficiency and simplicity.

The robot shown on the front cover is actual size.

Sherry Stokes (DC ’07)

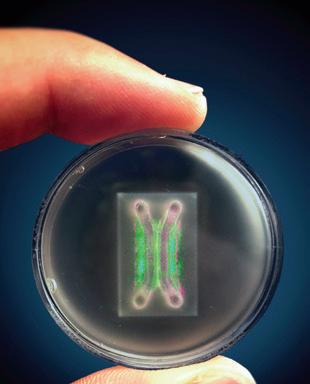

Collagen is well-known as an important component of our skin, but its impact is much greater, as it is the most abundant protein in the body, providing structure and support to nearly all tissues and organs. Using their novel Freeform Reversible Embedding of Suspended Hydrogels (FRESH) 3D bioprinting technique, which allows for the printing of soft living cells and tissues, the Feinberg lab has built a first-of-its-kind microphysiologic system, or tissue model, entirely out of collagen. This advancement expands the capabilities of how researchers can study disease and build tissues for therapy, such as Type 1 diabetes.

Traditionally, tiny models of human tissue that mimic human physiology, known as microfluidics, organ-on-chip, or microphysiologic systems, have been made using synthetic materials such as silicone rubber or plastics, because that was the only way researchers could build these devices. Because these materials aren’t native to the body, they cannot fully recreate the normal biology, limiting their use and application.

View our video: FRESH bioprinting

“By implementing a single-step bioprinting fabrication process, we manufactured collagen-based perfusable CHIPS in a wide range of designs that exceed the resolution and printed fidelity of any other known bioprinting approach to date. Further, when combined with multi-material 3D bioprinting of ECM proteins, growth factors, and cell-laden bioinks and integration into a custom bioreactor platform, we were able to create a centimeter-scale pancreatic-like tissue construct capable of producing glucose-stimulated insulin release exceeding current organoid based approaches.”

This technology is currently being commercialized by FluidForm Bio, a Carnegie Mellon University spinout company where co-author Dr. Andrew Hudson and his team have already demonstrated in an animal model that they can cure Type 1 diabetes in-vivo. FluidForm Bio plans to start clinical trials in human patients in the next few years.

“It is paramount for everyone to understand the importance of team-based science in developing these technologies and the value that varied expertise, ranging from biology to materials science,

“GOING FORWARD, THE QUESTION IS NOT, CAN WE BUILD IT? IT’S MORE OF, WHAT DO WE BUILD?”

- ADAM FEINBERG -

“Now, we can build microfluidic systems in the Petri dish entirely out of collagen, cells, and other proteins, with unprecedented structural resolution and fidelity,” explained Adam Feinberg, a professor of biomedical engineering and materials science and engineering. “Most importantly, these models are fully biologic, which means cells function better. This advance in FRESH bioprinting builds off of the research we published in Science in 2019, by improving the resolution and quality to create little fluidic channels that are like blood vessels down to about 100-micron diameter. Just as a frame of reference, the human hair is roughly 100 microns in diameter, so we’re able to engineer very tiny features that are almost capillary scale. By recreating this complex architecture, it allows us to build tissues that mimic different organ and disease types.”

In new research published in Science Advances, the group demonstrates the use of this FRESH bioprinting advancement, building more complex vascularized tissues out of fully biologic materials, to create a pancreatic-like tissue that could potentially be used in the future to treat Type 1 diabetes.

“There were several key technical developments to the FRESH printing technology that enabled this work,” explained Daniel Shiwarski, assistant professor of bioengineering at the University of Pittsburgh and prior postdoctoral fellow in the Feinberg lab.

brings both to the project, and our impact on society,” elaborated Feinberg.

“Going forward, the question is not, can we build it? It’s more of, what do we build? The work we’re doing today is taking this advanced fabrication capability and combining it with computational modeling and machine learning, so that we can hopefully better understand what we need to print. Ultimately, we want the tissue to better mimic the disease of interest or ultimately, have the right function, so when we implant it in the body as a therapy, it’ll do exactly what we want.”

Feinberg and his collaborators are committed to releasing open-source designs and other technologies that allow for broad adoption within the research community. “What we’re hoping is that very quickly, almost immediately, other labs in the world will be able to adopt and use this capability to expand it to other disease and tissue areas,” Feinberg said. “We see this as a base platform for building more complex and vascularized tissue systems, which has broad applications.”

Published in Science Advances, the paper was co-authored by Feinberg’s current and former Postdoctoral Fellows and Ph.D. students, Daniel Shiwarski, Andrew Hudson, Joshua Tashman, Ezgi Bakirci, Samuel Moss, and Brian D. Coffin. This ongoing research is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health.

The AI revolution has ushered in an era of exponential power and energy consumption. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, energy consumed by AI data centers could triple by 2028. Today, up to 40% of data center power use comes from cooling high-power chips—an astounding amount equivalent to the state of California’s entire electricity consumption.

To combat this, Sheng Shen, professor of mechanical engineering at Carnegie Mellon University, has developed an innovative thermal interface material that outperforms existing solutions. His design, published in Nature Communications, achieves ultra-low thermal resistance while increasing cooling efficiency via improved heat dissipation.

“The material is like a bridge between the nano- and macroscopic worlds,” explained Zexiao Wang, Ph.D. candidate in Shen’s lab. “Because the nanoscale material can be created using macroscale approaches, we can see with our own eyes the impact of the material on the world.”

Not only is Shen’s thermal interface material the best performing on the market, it is also highly reliable. The team tested the material at extreme temperature ranges from -55 to 125 degree Celsius for more than 1,000 cycles, and the material showed no performance degradation.

EXISTING STATEOF-THE-ART SOLUTIONS.

Novel thermal interface material designed by Sheng Shen. Sheng Shen and Rui Cheng are making this technology commercially available via their startup company, NovoLINC, Inc.

“This material solves a lot of existing challenges, and is ready to be used today,” said Shen. “While an immediate need is focused on cooling data centers, the application for this innovation is extensive. It can break through in industries that have been stuck using outdated thermal interface materials. It can be used for pre-packaging, reworked when using non-adhesives, and enables thermal bonding of two substrates at room temperature.”

“Oftentimes work at the nanoscale is foundational for a device that we might not see for decades,” said Qixian Wang, Ph.D. candidate. “It’s been exciting to see the real-world impact our material can have today because it is so easy to use.”

“Our material will have great benefits to the field of AI computing,” said Rui Cheng, postdoc and innovation commercialization fellow of CMU and the lead author of the paper published in Nature Communications. “Beyond reducing energy consumption, we can make AI development more affordable, more renewable, and more reliable.”

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation and Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy. Collaborators included Tianyi Chen and Ana V. Garcia-Caraveo from Oregon State University, and Navid Kazem and Loren Russell from Arieca, Inc.

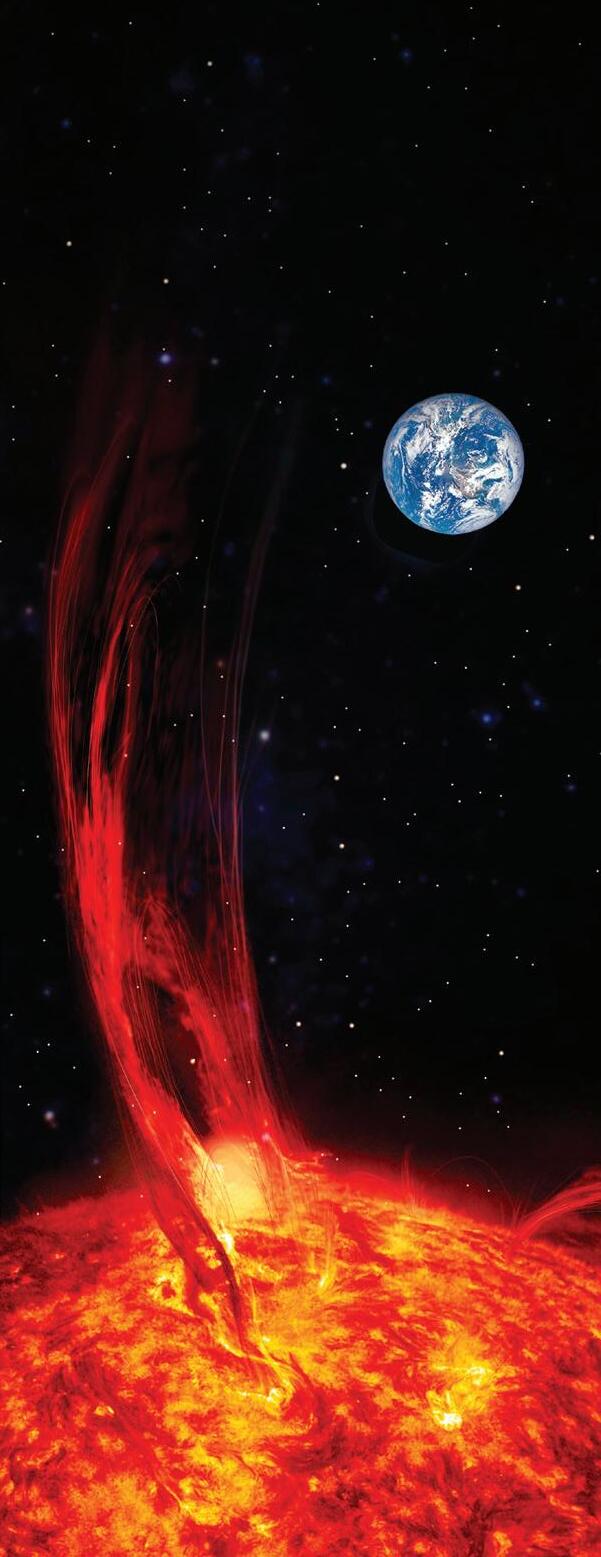

Space is a highly volatile environment. Factors like radiation, extreme temperatures, and debris make outer space a challenging environment to operate technology. In particular, radiation can have devastating effects on computer chips.

Space radiation, from solar flares or galactic cosmic rays, alter the electrical properties on an integrated circuit. The parts of a computer chip most vulnerable to radiation effects are the data storage elements, like flip-flops (FF) commonly used in digital logic. While radiation-hardened (rad-hard) electronics already exist to withstand harsh radiation environments, Carnegie Mellon researchers have fabricated more compact radhard chips that achieve equivalent or better radiation tolerance than conventional radiation-tolerant designs.

The team won a Best Paper Award for their paper, “A Soft Error Tolerant Flip Flop for eFPGA Configuration Hardening in 22nm FinFET Process,” at the Design, Automation and Test in Europe Conference held in Lyon France. The work is a collaboration with Sandia National Labs on radiation tolerant microelectronics for space and aerospace applications.

“As FFs are one of the most common elements on a chip, reducing the area of the FF has a significant reduction of the overall chip area,” explains Ken Mai, principal systems scientist in the electrical and computer engineering department and author on the paper. “Lower area leads to lower manufacturing costs, higher performance, and better energy efficiency, which is particularly important for space applications.”

Novel chip design has same or better tolerance of radiation than conventional designs, and it is more compact, which is important for space applications.

Most chips in space use FF designs that occupy more area on the chip than the one that the team designed. The crux of the invention is that the team achieved the same or better tolerance of radiation than the conventional FF designs, but in a smaller area.

“While the specific components, or transistors, used are not specific to Carnegie Mellon, but the way they are arranged is our own invention,” explains Mai.

Traditional robust FF designs use triple modular redundancy to ensure error free operation. This updated design re-uses some of the components of a single basic FF to achieve the same level of radiation tolerance without the high area overhead of using three copies of the FF.

Currently, the team is designing full system-on-a-chip prototypes and plan to test and deploy on a CubeSat (a miniature satellite) in 2026 in collaboration with Brandon Lucia and Zac Machester’s Spacecraft Design-Build-Fly Lab course.

Paper authors include Prashanth Mohan, Siddharth Das, Oguz Aatli, Josh Joffrion (Sandia) and Ken Mai.

Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe and sometimes hailed as “the fuel of the future” for its impressive efficiency as a green energy carrier. Over the last two decades, Shawn Litster, professor of mechanical engineering, has worked to advance the critical energy technologies required to electrify heavy-duty transportation using hydrogen fuel cells.

Q: A:

WHY IS HYDROGEN REFERRED TO AS “THE FUEL OF THE FUTURE?”

When hydrogen is referred to as a fuel, it’s most often in reference to hydrogen fuel cells. Hydrogen fuel cells are a promising power source because they are much more efficient than traditional combustion engines. Unlike combustion engines that burn fuel to generate energy, fuel cells turn hydrogen into electricity via an electrochemical reaction, so the fuel goes directly to electricity. The only emission from a fuel cell is pure, drinkable, water.

Q: A:

WHAT IS THE ADVANTAGE OF USING A HYDROGEN FUEL CELL INSTEAD OF A BATTERY?

A battery and a fuel cell have very similar structures — both have two electrodes with an electrolyte in the middle, but in a battery there are particles that are responsible for both energy storage and energy conversion. To make a battery power something longer we have to increase the weight of the whole battery system. This is problematic when it comes to electrifying vehicles, especially heavy-duty trucks, because increasing the weight of the battery takes away from the payload a truck can carry. In a fuel cell, we decouple energy storage and energy conversion. A fuel cell handles the energy conversion — the acceleration capabilities of the vehicle, and a separate, lightweight fuel tank stores the lightweight fuel. We can even adjust the size of the tank depending on the range requirements of the vehicle without the full weight penalty that batteries present.

HOW DO WE GET HYDROGEN?

We would like to decarbonize the hydrogen production process that currently relies on fossil fuels by using something called electrolysis. Electrolysis uses electricity to split water directly into hydrogen and oxygen, consequently reducing carbon emissions. Electrolysis further enables us to convert renewable electricity into a versatile fuel and industrial feedstock.

HYDROGEN TO TRULY FUEL THE FUTURE?

Heavy-duty trucking companies are looking at the total cost of ownership for a fuel cell vehicle, this includes the upfront and lifetime costs. For widespread hydrogen fuel cell adoption, we need to reduce what it costs to make fuel cells and make them more durable. Q: A:

Q: A:

HOW IS YOUR LAB ADDRESSING THESE CHALLENGES?

The materials used in fuel cells and electrolyzers are expensive and scarce. My lab is focused on translating developments in materials including catalysts and polymers for high-performance fuel cells and electrolyzers. Our goal is to develop materials that enable scalable and affordable hydrogen fuel cells.

The ability to replace organs on demand could potentially impact health care on par with curing cancer. Building on 30 years of research experience in the field of cryopreservation, Yoed Rabin aims to preserve the liver, one of the most complex and in-demand organs. He anticipates that his methods may make their way into clinical practice within the next five to ten years.

Seventeen people die each day waiting for an organ transplant in the United States. Only 10% of the worldwide need for organ transplantation is estimated to be met. It has been suggested that the ability to replace organs on demand could impact health care on par with curing cancer. Developing efficient ways to preserve organs is essential to help bridge the gap.

Yoed Rabin has been studying cryopreservation and developing enabling technologies for three decades. His latest project, funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (National Institutes of Health), will seek to preserve the liver, one of the most complex and in-demand organs, in cryogenic temperatures.

“If ice crystals form in an organ during preservation, cells are destroyed,” explained Rabin, a professor of mechanical engineering. “One way to create more favorable conditions for cryopreservation is to elevate the pressure surrounding the organ.”

A promising method to elevate the pressure relies on constraining the natural tendency of water to expand upon freezing when placed in an extremely rigid container, and the application is known as isochoric cryopreservation. Unfortunately, the hazardous effects of crystallization must take place somewhere in the container for isochoric cryopreservation to work. Rabin is aiming at advancing this approach to the next level by eliminating the need, and even the possibility, for ice to form in the cryopreservation container.

“I’ve devoted my research career to developing tools and enabling technologies that I believe will bear fruits in my lifetime,” said Rabin. “I sense that we are only five to 10 years away from seeing this method in clinical practice.”

The $1.3 million dollar grant builds on Rabin’s legacy in the field.

“My research continues to be an extension of itself,” he said. “Oftentimes projects don’t start and end in isolation from the broader effort, and I am thankful that my work sees a consistent line of progress over such an extended period of time.”

The project is conducted in collaboration with Charles Lee at the University of North Carolina Charlotte, a well-established leader in the field, with decades of experience in liver research. Lee will test the new cryopreservation technology on animal models. The advisory panel to this project includes transplant surgeons and experts in the field from Harvard Medical College, Mayo Clinic, and the University of Minnesota.

Extending liver preservation time beyond the current 16 to 24 hours will greatly solve many of the logistical issues of donor livers. This will allow greater usage of donor livers because a broader base of recipients located at greater distance away from the donor will become possible. The team’s isolated liver perfusion and transplant models should quickly assess proof of concept and feasibility of this new technology.

Rabin collaborates with advisors and colleagues scattered across the United States including transplant surgeons, physiology experts, cryobiologists, and his own former students who now work in industry. He is a senior member of the Engineering Research Center for Advanced Technologies for the Preservation of Biological Systems (ATP-Bio), an NSF center that aims to “stop biological time” and extend the ability to bank and transport cells, tissue, organs, and more.

“The idea behind working in such a supportive and diverse environment is that we can accelerate progress by working as closely as possible to the end user, which in this case is clinical use.”

Preeclampsia, intrauterine fetal growth restriction, and other “great obstetrical syndromes” have been linked to disordered placenta development, so understanding the structure and function of this vital organ is critical to detecting pregnancy disorders.

Hemodynamic digital twins are virtual representations of the way blood flows through the body. They have already been proposed to predict cardiovascular disease risk, but collecting measurements of pregnant uteri to inform digital twin models of pregnancy is limited due to safety concerns.

By computationally replicating realistic placenta blood flow, Noelia Grande Gutiérrez of Carnegie Mellon University’s Department of Mechanical Engineering is addressing this lack of data.

A breakthrough in the field, her lab has developed a computational model of the basic functional unit of the human placenta: the placentone.

The team’s research uncovered the anatomical parameters required to ensure a pragmatic, physiological simulation of a healthy pregnancy.

“The effect of a placenta’s anatomic structures on hemodynamics had not been systematically assessed until now,” said Grande Gutiérrez.

“Our computational model has

enabled us to define physiological parameters for vein location and diameter, cavity diameter and lengths, and spiral artery remodeling length. These guarantee that our models are physiological even though they are not patient-specific.”

This is the first step toward placenta digital twins.

Armita Najmi, Ph.D. candidate in Grande Gutiérrez’s lab and lead author of the paper said, “Our computational study provides practical insight into what a healthy and efficient placentone should look like, and this understanding is necessary for improving our ability to predict and identify pregnancy disorders.”

Moving forward, the team will

study the effects of blood flow on the microstructure of the placentone during the second trimester of pregnancy.

“Partial spiral artery remodeling observed in some complicated pregnancies directly affects the hemodynamics inside the placenta,” said Najmi. “We are trying to figure out how this partial spiral artery remodeling affects the development of the placental villi and its structure in complicated pregnancies.”

“There’s so much still to do in this space,” said Grande Gutiérrez, “But computational modeling allows us to advance research and design medicinal therapies with a very personalized approach.”

As viral vaccines are increasingly used to meet global health needs, the pharmaceutical industry is manufacturing larger amounts of virus to make them. A new method of virus detection from researchers at Carnegie Mellon University is poised to improve quality control in vaccine manufacturing by rapidly quantifying viral genomes in samples taken directly from bioreactors.

Research from Jim Schneider’s lab has uncovered a new mechanism of electrophoresis that attaches a very short piece of double-stranded DNA, which they call a nanosnag, to a viral genome. “The nanosnag slows down the genome as it moves through a gel-like matrix in the presence of electric fields. This abrupt slow-down concentrates the genomes in a sharp band that confirms that the

viral genome is intact and tells us how much of it is there,” explains Schneider, a professor of chemical engineering. Despite the slow-down provided by the nanosnag, the 10-minute runs are very fast compared to gel electrophoresis, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), or other methods used to assay DNA. This is because Schneider’s method uses surfactants rather than polymers as a gel-like matrix.

Polymers like those used in gel electrophoresis have long-lived crosslinks that the DNA has to move around. That creates a sieving process that separates DNA based on length. Schneider has spent many years developing electrophoresis methods for separating DNA. The crosslinks in the surfactant systems that Schneider uses don’t live as long, so while they are effective they allow long DNA or RNA to pass quickly.

In his earlier work with short DNA targets, Schneider developed micelle-tagging electrophoresis (MTE). Here, the surfactant assembles into a micelle and attaches to the DNA of interest, providing enough drag to separate the target DNA from others in the mixture.

For longer DNA, like a viral genome, more drag is required. Instead, the researchers found ways to marry the sieving method with MTE. “You still have the mechanism of drag-tagging, and you now also have a mechanism of sieving,” says Schneider. His lab has been working to understand how those mechanisms interact.

Their new nanosnag method does two things. It changes the mobility of the viral genome to put it in a place where it’s clearly separated from the other nontagged material. It also has a concentrating effect.

The rapid deceleration of the genome when it starts to interact with micelles causes a concentration like that seen anytime something moving very quickly is forced to slow down. Picture the traffic congestion caused by a lane closure on a highway.

“What’s surprising is that the addition of a tiny, 30-base fragment of double-stranded DNA has such a huge effect on the migration of a 5,000-base viral genome,” says Schneider. “We initially attached the fragment as a way to attach fluorophores to the genome and did not expect any impact on the electrophoretic mobility. But when you dig into the polymer physics, you see why it happens. The short, double-stranded fragment is much stiffer than the genome, and its attachment forces the genome to take a longer, more winding path through the matrix.”

Jim Schneider’s method of electrophoresis can be used to detect viral genomes manufactured in bioreactors. It is faster and more precise than current methods for measuring how much virus is produced.

The tagging technique also enables researchers to detect only the viral genome, because the nanosnag fragment binds specific sequences. “If those sequences don’t exist on a DNA or RNA fragment in a sample, the nanosnag will not attach, and none of this slow-down or sharpening occurs,” he says. “So, we can confidently discriminate the viral genome from other nucleic acids that might be in the sample.”

The new method could be used, for example, to count the number of viruses inside a bioreactor that makes them. Viral bioreactors don’t produce a steady amount of virus, due to the way viruses are produced throughout the cell cycle. Current methods for measuring how much virus is in a batch are slow and imprecise. Schneider’s nanosnag method, published in Biomacromolecules, provides the biomanufacturing industry with a direct way to quantitate virus, and it’s fast.

Schneider is engaged with pharmaceutical companies to bring the technology to manufacturing lines. One challenge is that bioreactor samples have a lot of cell debris, viral capsids, and other proteins that typically interfere with viral detection methods. The surfactants used as gel-like matrices can help sequester these compounds into micelles so that the electrophoresis is not affected. Determining just how much material the surfactants can handle is an active area of investigation in the Schneider’s lab. Schneider’s electrophoresis methods offer a unique advantage for translation to industry because pharmaceutical labs already have standard commercial platforms to do electrophoresis. “If they follow our methods, they don’t need to buy new equipment and can enjoy the speed and accuracy benefits right away,” he says.

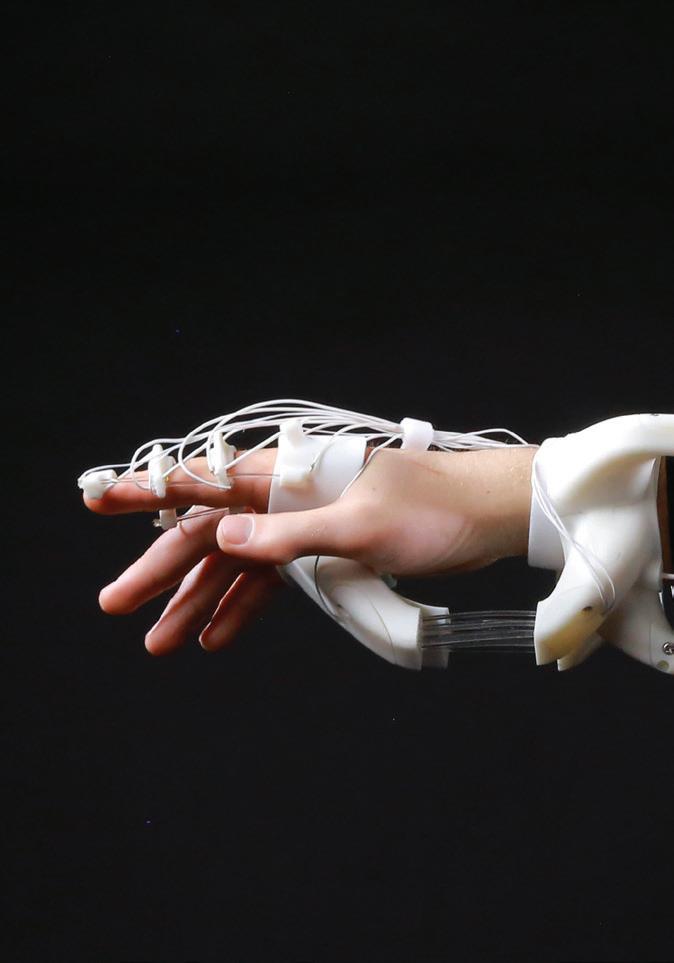

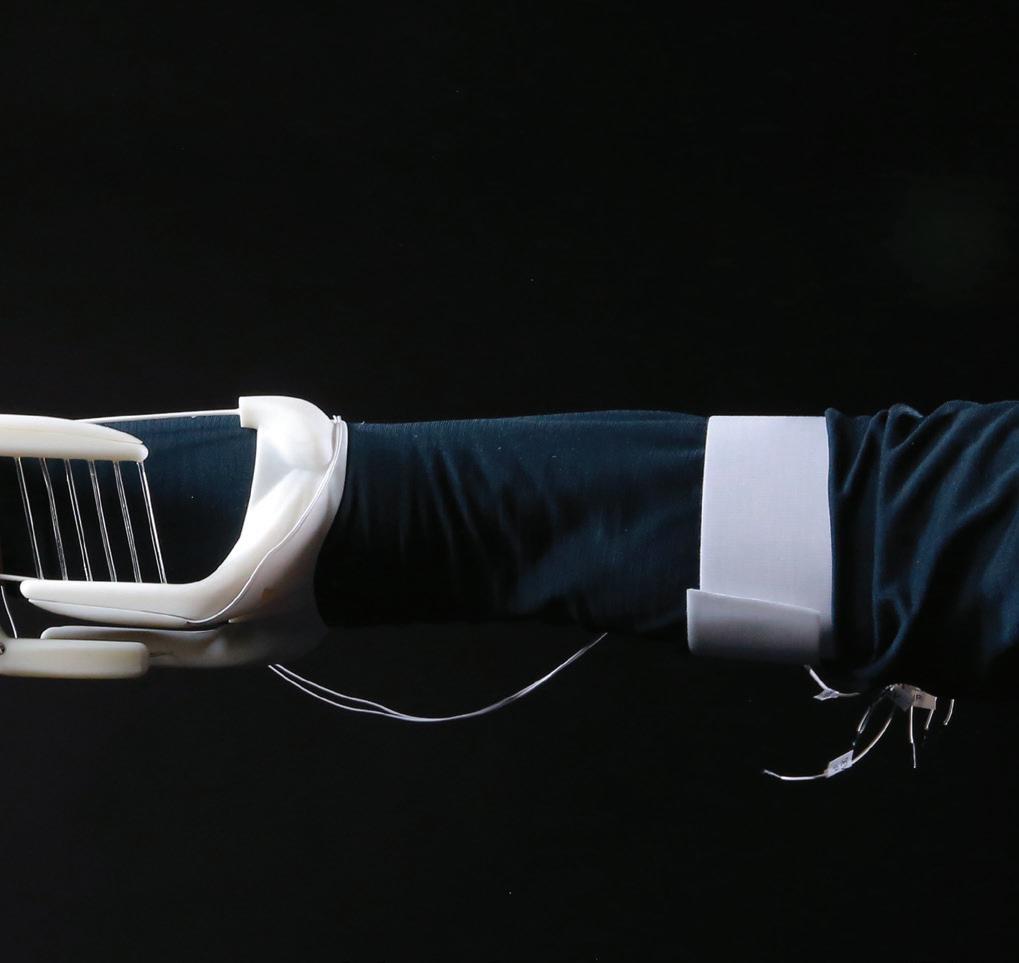

Researchers from Carnegie Mellon University have developed a cutting-edge method to identify muscle activity in densely packed regions like the forearm. Using high-density surface electromyography (HD-sEMG) sensors alongside other techniques such as peripheral nerve stimulation, spatial filtering, and ultrasound imaging, this approach offers more accurate identification of muscle activity. The findings could lead to better treatments for neurological injuries and advancements in prosthetic limb control.

By electrically stimulating specific nerves, researchers can selectively activate muscles, providing a controlled way to study muscle activity. The HD-sEMG system used in this study features a 64-channel grid that is adhesively applied to the skin to capture electrical signals, known as M-waves, produced by active muscle contractions. The sensors provide high-resolution measurements of muscle activity, allowing researchers to apply advanced spatial filters to minimize electrical interference from neighboring muscles, known as crosstalk, and to isolate M-waves from target muscles. Applying these filters to HD-sEMG nearly eliminated crosstalk at distances of 2.55 cm or more. Reducing crosstalk allows for clearer separation of hotspots on heat maps, making it easier for

MUSCLE BORDERS

The HD-sEMG system used in this study features a 64-channel grid that is adhesively applied to the skin to capture electrical signals, known as M-waves, produced by active muscle contractions.

researchers to distinguish muscle activity and use ultrasound imaging to verify the location and identity of the underlying muscles.

Accurately identifying the strength and location of muscle activity with minimal distortion is critical for studying motor function, especially for diagnosing problems caused by stroke, spinal cord injury, and other neurological disorders. The techniques developed in this research have the potential to improve neurological treatments, such as physical rehabilitation, as well as improve the control of prosthetic limbs.

“We are currently applying this method to clinical populations, including stroke patients with hemiplegia and amputees with phantom limb pain,” explained Ernesto Bedoy, a postdoctoral researcher at CMU who led this study. “We’re using this approach to better understand muscle activity patterns in these populations and develop personalized treatment strategies that maximize recovery.”

This research was published in the Journal of Neurophysiology. The researchers include Bedoy; Douglas Weber, a professor of mechanical engineering and member of the Neuroscience Institute; and Efrain Guirola Diaz, Ashley Dalrymple, Isaiah Levy, Thomas Hyatt, Darcy Griffin, and George Wittenberg.

“DeepFocus,”

a new method of minimally invasive brain stimulation could treat conditions like depression, PTSD, and addiction.

Researchers from Carnegie Mellon University and Allegheny Health Network have developed a new method for deep brain stimulation.

The technique, called “DeepFocus,” uses transcranial electrical stimulation (TES) on the scalp and transnasal electrical stimulation (TnES) to achieve accurate electrical stimulation in the brain.

DeepFocus uses close proximity and highly conductive pathways offered by thin bones between the nasal cavity and brain to create larger and more accurate electric fields in deep brain regions than traditional scalp electrode configurations.

“By going through the nose, we can place electrodes as close to the brain as possible without opening the skull,” explained Mats Forssell, a CMU electrical and computer engineering research scientist and a lead author on the study. “We gain access to structures on the bottom of the brain which are hard to reach in other ways. That’s what makes this technique so powerful.”

DeepFocus could enable more efficient and lower-risk targeting of deep brain structures to treat multiple neural conditions, including depression, PTSD, OCD, addiction, and substance abuse disorder. By targeting the brain’s “reward circuit” (the orbitofrontal cortex, Brodmann area 25, amygdala, etc.) and managing environmental and time of day factors, DeepFocus could disrupt the brain’s associations with cravings.

DeepFocus could provide both short- and longterm treatments. Chronic treatments that require persistent stimulation could be delivered through an implant, while acute applications could be delivered in short sessions with endoscopic insertion and removal of the device.

“The approach affords access to parts of the brain that have been traditionally surgically challenging,” said Boyle Cheng, a professor of neurosurgery at Allegheny Health Network’s (AHN) Neuroscience Institute. “The potential for better treatments with fewer complications in patients with

DeepFocus places electrodes in nasal cavities as well as under the scalp and jointly optimizes injected currents to cause deep stimulation with no shallow stimulation.

various neurological disorders is highly motivating.”

There is precedent for treating neurological conditions with implanted electrodes in the deep brain, but it requires a surgical procedure to implant the system that is highly invasive and carries risk of intracranial hemorrhage and infection. This method also isn’t steerable, which means the stimulation target cannot be changed once the electrodes are implanted inside the brain.

“Early results of invasive deep brain stimulation (DBS) in treating neuropsychiatric conditions have been very promising,” said Pulkit Grover, the senior author of this study and a professor of electrical and computer engineering, biomedical engineering, and CMU’s Neuroscience Institute. “But the sophisticated surgery required for invasive DBS technology makes it unlikely to be widely adopted. Also, the invasive approach offers limited flexibility to clinicians after electrodes have been placed.”

Noninvasive techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), transcranial focused ultrasound stimulation (tFUS), and TES have lower risk and are steerable, but they aren’t as effective as implanted electrodes. TMS and TES can also cause high scalp pain because of intense electric currents. DeepFocus offers a minimally invasive solution that is more accurate, less painful, and steerable.

Alexander Whiting, a neurosurgeon and the director of epilepsy surgery for AHN’s Neuroscience Institute, said, “This new tool could be a game changer, offering the ability to treat deep areas of

the brain in mental health disorders like depression, OCD, and addiction in a minimally invasive way that does not involve traditional incisions, or permanent placement of implanted hardware.”

Alongside DeepFocus, researchers developed DeepROAST, a simulation and optimization platform used to carefully calibrate the injected currents in this new technique. DeepROAST simulates the effect of complex skull-base bones’ geometries on the electric fields generated by DeepFocus using realistic head models. It optimizes the placement of electrodes on the scalp and in the nose and helps electrical current injection patterns to be more accurate and efficient.

“With the DeepROAST platform, we can simulate how the electric field travels inside the brain,” said Yuxin Guo, a CMU Ph.D. student. “DeepROAST automates and optimizes the placement of electrodes on the scalp and transnasally so that deep brain regions can be targeted with better efficiency and focality. This allows stimulation of targets that were previously difficult to access.”

Grover added, “The U.S. is facing a severe mental health crisis, with PTSD, depression, and substance use disorders. While surgically implanted deep-brain stimulation has shown promise, it lacks widespread acceptance and the necessary FDA approvals for these conditions. Our minimally invasive, lowrisk approach, which can be implemented in an outpatient setting, presents a scalable and widely applicable solution.”

It’s easy to take joint mobility for granted because, without thinking, we are able to turn the pages of a book or bend to stretch out a sore muscle. Designers don’t have the same luxury. When building a joint, be that for a robot or wrist brace, designers seek customizability across all degrees of freedom but are often restricted by their versatility to adapt to different use contexts.

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University have developed an algorithm to design metastructures that are reconfigurable across six degrees of freedom and allow for stiffness tunability. The algorithm can interpret the kinematic motions that are needed for multiple configurations of a device and assist designers in creating such reconfigurability. This advancement gives designers more control over the functionality of joints for various applications.

The team demonstrated the structure’s versatile capabilities via multiple wearable devices tailored for unique movement functions, body areas, and uses.

“In the case of carpal tunnel syndrome, a typical wrist brace prevents patients from exercising their joints at all times to avoid injury and promote healing. But oftentimes during rehab, patients still need to momentarily move their joints to carry out chores that were typically effortless to do. Because

our structures can reconfigure to selectively lock and unlock motions, it can restrict motions to fulfill the function of a brace for the majority of the time but selectively allow the patient to move their joint in intended ways for short periods of time. This allows patients to engage in daily activities without having to frequently take on or off the brace,” said Humphrey Yang, mechanical engineering postdoctoral researcher.

Resistive heating wires added to the 3D-printed metastructure enable the structures to reconfigure their motional degrees of freedom during use. In the future, the team believes they will have the necessary technology to additively manufacture the entire device as one piece. This would reduce production costs and allow for affordable devices with enhanced functionality.

“This is a gateway project for exciting applications,” said Dinesh K. Patel, research scientist. “Our algorithm is material agnostic, so in the future, we could look to create devices with soft, flexible materials for more comfortable wear.”

Roboticists could benefit from the structure’s ability to reconfigure joint mobility because a robot designed for multiple purposes could need varying mobilities. The ability to design joints with programmable and arbitrary reconfigurability could be a “holy grail” in creating versatile robots. For instance, as part of a home helper robot, a joint could enable a few rotational degrees of freedom to mimic a human limb. The robot could then interact with objects with human-hand capabilities. However, when interacting with soft objects or in water, the joint could reconfigure to provide more degrees of freedom as well as lower its stiffness, allowing the limb to functionally morph into a tentacle for better grasping and swimming.

Additionally, the device’s ability to reconfigure and provide various stiffnesses enables it to mimic the sensation of touching materials ranging from soft gel to metal surfaces. This could advance augmented reality for rehab and medical training.

“In this field, there hadn’t been a generalizable method to design reconfigurable, compliant kinematic structures. It was important to us to democratize them and expand their versatility for wider application,” said Yang.

“It shows how mechanisms can further augment material intelligence to achieve our ultimate vision of physically embodied intelligent matter and machines,” said Lining Yao, one of the principal investigators supervising the project.

New technology from Reeja Jayan in the Department of Mechanical Engineering extends battery life cycle by 10x, reduces charging time, and improves operating safety.

Microscopic yet mighty, the particles within lithium-ion batteries that contain critical minerals determine how much energy batteries can store, how fast they charge, and for how many years they can power your device. Over time chemical reactions crack the surface of these particles. Those cracks interfere with current flow, leaving us with a dead battery and critical minerals buried alive.

To build a domestic, circular supply chain for batteries, Reeja Jayan in Carnegie Mellon University’s Department of Mechanical Engineering has developed a low-cost, activated nano polymer layer that extends battery life cycle by 10x, reduces charging time, and improves operating safety.

“Instead of mining entire ecosystems out of existence to collect very limited minerals, we need to focus on innovations that lead to cost-effective, scalable solutions that prolong battery life and reduce waste,” said Jayan.

For the last 10 years, Jayan’s team has fine-tuned a method to maximize battery capacity without reducing the battery life. Using chemical vapor deposition, a materials processing technique widely used in semiconductor manufacturing, the team can encapsulate the battery’s critical mineral particles with a conducting polymer material that “seals” cracks and maintains current flow. The material must be applied while the battery is being manufactured.

“We’ve reimagined a decades-old process to precision engineer coatings that protect and extend the life of critical battery materials,” said Jayan. “We see this as a foundational step towards building a domestic and circular battery economy—where performance and sustainability go hand in hand.”

Beyond protecting the minerals inside, the activated polymer layer also acts as an alarm within the battery that can trigger a change in

chemical behavior to prevent fire. We can think of this response as similar to the way a phone shuts itself off to prevent overheating.

Jayan is working to make this technology commercially available through her company SeaLion Energy which received funding from the U.S. Department of Energy Advanced Research Projects-Energy (ARPA-E) as part of a national effort to extend battery life and facilitate repair and reuse to reduce waste for broad potential applications—from electric vehicles and grid storage to data centers and specialty electronics.

The team is also exploring ways to adapt the technology for use in other fields. So far, they have seen success in sensors and air quality monitors.

“Breakthroughs of this nature are made possible by the uniquely collaborative environment at Carnegie Mellon,” she said. “The success of this project reflects the integration of expertise across chemical, mechanical, and materials engineering.”

Microwave synthesis produces MXene 25x faster than traditional methods while using 75% less energy.

MXenes are a lightweight two-dimensional material capable of protecting everything from spacecrafts, mechanical components, and maybe even people, from harmful radiation. Because traditional synthesis requires multi-step processes that can take up to 40 hours, MXene is difficult to produce.

By introducing a rapid single-step microwave synthesis method, Reeja Jayan has reduced MXene production time to ninety minutes and cut energy consumption by 75%.

“Our work has implications for the global production of chemicals because almost a third of greenhouse gas emissions come from chemical manufacturing and production,” said Jayan, a professor of mechanical engineering at Carnegie Mellon University.

The research, published in Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing, also demonstrates a unique ability to customize MXene’s composition to change the type of radiation that the material can protect against. To date, the team has tested their material across the X-band—radio frequencies ranging from 8.0-12.0 GHZ—but to protect against electronic materials in outer space, more testing against cosmic radiation is needed.

“We assumed that because we sped up the process, we would lose some of the shielding performance in return,” said Jayan. “We were pleasantly surprised that, although there are subtle structural differences, we didn’t see any shielding efficiency tradeoff at the lab scale.”

Moving forward, Jayan will test her synthesis process at a larger scale. In partnership with an aerospace materials manufacturer, her team will integrate MXene into test panels for radiation testing.

“We’ve developed a low carbon process that significantly saves energy. If it can be scaled up now, more than ever before, we stand to create a critically needed and substantial environmental impact.”

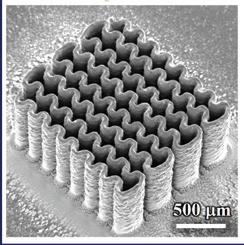

New 3D printing technique fabricates highly complex and controllable ceramic nanostructures that could be the key to emerging engineering systems.

The same material you drink your morning coffee from could transform the way scientists detect disease, purify water, and insulate space shuttles, thanks to an entirely new approach to ceramic manufacturing.

Published in Advanced Science, 3D-AJP is an aerosol jet 3D nanoprinting technique that allows for the fabrication of highly complex ceramic structures that at just 10 micrometers (a fraction of the width of human hair) are barely visible to the naked eye. These 3D structures are made up of microscale features including pillars, spirals, and lattices that allow for controlled porosity, ultimately enabling advances in ceramic applications.

“It would be impossible to machine ceramic structures as small and as precise as these using traditional manufacturing methods.

They would shatter,” explained Rahul Panat, professor of mechanical engineering at Carnegie Mellon University and the lead author of the study.

Ceramics are believed to be the key to emerging engineering systems because of their wear resistance, thermal stability, thermal insulation, high stiffness, and biocompatibility. While existing 3D printing techniques have opened doors for ceramics fabrication, oftentimes severe shrinkage and/or defects are observed during post-printing processing due to the removal of additives from the ink that were needed to support the material during printing. With shrinkage ranging from 15-43%, it is challenging for fabricators to set printing parameters that would output the ideal part.

3D-AJP does not rely on additives in the ink and therefore sees only a 2-6% shrinkage rate, so manufacturers can feel confident

BARELY VISIBLE TO THE NAKED EYE, THIS HIGHLY COMPLEX CERAMIC STRUCTURE WOULD BE IMPOSSIBLE TO FABRICATE USING TRADITIONAL MANUFACTURING TECHNIQUES, BUT IT COULD BE THE KEY TO TOMORROW’S HIGH PERFORMANCE ENGINEERING SYSTEMS.

that the structure they want is the structure they’ll print. To ensure this, the team performed a detailed manufacturability study to identify the CAD programs needed to produce the final shape.

Additionally, the team, including postdoc Chunshan Hu, demonstrated 3D-AJP’s unique ability to print two ceramic materials in one single structure which allows for advanced applications.

“Using these structures, we can detect breast cancer markers, sepsis, and other biomolecules from a blood sample in just 20 seconds,” said Panat.

This application, which is an extension of past research wherein he developed a metal biosensor to detect Covid-19 in just ten seconds, is advantageous because compared to metal, ceramic sensors can be manufactured nearly five times faster. Panat also cites the benefit of this technology in water purification and thermal insulation.

“In the presence of UV light and zinc oxide, chemicals can be degraded, so by creating a 3D structure with a higher surface area, we can increase the speed and the effectiveness of water purification by four times,” he said. “Additionally, our ability to control the porosity of these structures, allows us to control and tailor thermal conductivity of structures such as the insulators used in space shuttles.”

Full control over mid-infrared wavelengths enables advancements in applications ranging from chip security to personalized health monitoring.

Without the ability to control infrared light waves, autonomous vehicles wouldn’t be able to quickly map their environment and keep “eyes” on the cars and pedestrians around them; augmented reality couldn’t display realistic 3D displays; doctors would lose an important tool for early cancer detection. Dynamic light control allows for upgrades to many existing systems, but complexities associated with fabricating programmable thermal devices hinder availability.

A new active metasurface, the electrical-programmable graphene field effect transistor (Gr-FET), from the labs of Sheng Shen and Xu Zhang in Carnegie Mellon Univer-

A new active metasurface, the electrical-programmable graphene field effect transistor (Gr-FET) enables the control of mid-infrared wavelengths.

sity’s College of Engineering, enables the control of mid-infrared states across a wide range of wavelengths, directions, and polarizations. This enhanced control enables advancements in applications ranging from infrared camouflage to personalized health monitoring.

“For the first time, our active metasurface devices exhibited the monolithic integration of the rapidly modulated temperature, addressable pixelated imaging, and resonant infrared spectrum.” said Xiu Liu, postdoctoral associate in mechanical engineering and lead author of the paper published in Nature Communications. “This breakthrough will be of great interest to a wide range of infrared photonics, materials science, biophysics, and thermal engineering audiences.”

The two-dimensional device is made up of gold array pixels that either directly interface with a single graphene layer or are separated by an insulation layer.

“It has low crosstalk, meaning the signals transmitted from one channel do not interfere with another,” said Zexiao Wang, Ph.D. candidate in mechanical engineering. “This breakthrough allows for scalable 2D electrical writing for densely packed, independently addressable pixels.”

Tianyi Huang, also a Ph.D. candidate in mechanical engineering, led the development of a specially designed circuit that powers the device. This allows the device to operate on its own or integrate into existing products.

“This device is scalable. It could be used on a chip to prevent side channel attacks by camouflaging existing thermal emissions with misleading, programmed emissions. On the other side it could be worn in a garment to detect breast cancer cells,” explained mechanical engineering Ph.D. candidate Yibai Zhong.

Side channel attacks are a way to exploit sensitive information, like encryption keys, by analyzing subtle temperature variations caused by computing device operations. By monitoring temperature fluctuations with a thermal imaging camera, an attacker can potentially piece together information. Shen’s device could act as an added level of security by camouflaging thermal emissions.

“We aren’t too far off from seeing this technology integrated into our lives,” said Shen. “We could be using it in the next five to 10 years.”

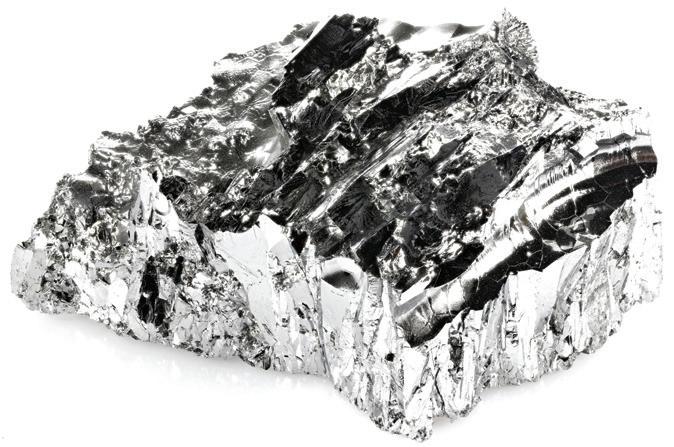

Tellurium is the 52nd element on the periodic table. It is a conductive metalloid, and it acts like a p-type material. 2D tellurium offers outstanding electrical performance.

Carnegie Mellon University researchers have devised a method to create large amounts of a material required to make two-dimensional (2D) semiconductors with record high performance. Their paper, published in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, could lead to more efficient and tunable photodetectors, paving the way for the next generation of light-sensing and multifunctional optoelectronic devices.

“Semiconductors are the key enabling technology for today’s electronics, from laptops to smartphones to AI applications,” said Xu Zhang, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering. “They control the flow of electricity, acting as a bridge between conductors [which allow electricity to flow freely] and insulators [which block it].”

Zhang’s research group wanted to develop a photodetector that is capable of detecting light and could be used in a variety of applications. To create the device, the group needed to use materials that were an atom’s-width thick, or as close to 2D as is possible.

Today’s semiconductor industry relies heavily on CMOS (complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor) technology, which uses two types of semiconductor materials to enable energy-efficient electronic circuits, called p-type (“positive-type”) and n-type (“negative type”) materials.

“Making a good p-type semiconductor is not only important for photodetector work, but also fundamentally important for almost all electronics,” Zhang said.

While there are many kinds of 2D n-type materials available, 2D p-type materials are rarer—until now. CMU researchers seek a powerful new p-type semiconductor material, which could solve a critical bottleneck in the field of ultra-thin electronics.

Luckily, they did know of a fitting material: tellurium. Tellurium is the 52nd element on the periodic table, located in group 16, a few periods (rows) below oxygen. It is a conductive metalloid, but most importantly, it acts like a p-type material. Even better, of the materials they tested, 2D tellurium had the highest mobility, or fastest conducting speed, at 1450 cm2/Vs, meaning that devices built with it can act extremely quick. It also is much more stable in the air than the leading alternative, black phosphorus, so it does not easily degrade and stays fast and efficient for longer.

“This physical vapor deposition growth tellurium greatly enriches the 2D semiconductor material family,” said Tianyi Huang, graduate student in mechanical engineering and first author of the paper. “Its p-type property and outstanding electrical performance make it a strong candidate in various potential applications such as high-speed CMOS circuits, high-frequency RF [radio frequency] circuits, photodetectors, energy harvesting, and so on.”

Besides the ultra-light weight of the device, the tellurium-enabled photodetector is highly tunable, allowing its parameters to be changed so it can be used in a variety of applications, a property that is not true of other photodetectors. The researchers intend to expand this work to find its limits and best applications.

This interdisciplinary work was done through close collaboration with Sheng Shen, professor of mechanical engineering, and his group.

“With its unique properties, 2D p-type tellurium holds great promise for applications in photodetection and electronics. We are excited to further explore its potential in the near future,” Shen said.

As researchers continue to push the boundaries of 2D materials, this discovery marks a significant step toward a future where atom-thick electronics redefine speed, efficiency, and versatility.

“IMPROVING FLOOD PREDICTION MODELS WILL HELP COMMUNITIES DEVELOP EFFECTIVE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS AND ADAPTATION STRATEGIES.”

- DAVID ROUNCEASSISTANT PROFESSOR, CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING

Outburst floods are nothing new to glaciologists. For years, researchers have known the potential hazard that forms when glacier movements create icedammed basins, trap meltwater, and pool into large reservoirs. Recently, however, glacier outbursts have become more devastating to their surrounding communities, releasing increasing water levels year after year. In 2024, a flood in Juneau, Alaska broke records for the second year in a row, displacing residents, eroding landscapes, and destroying homes.

To learn more about these phenomena, the National Science Foundation is funding a team of researchers to focus on better understanding and estimating an annual outburst flood that affects Juneau as well as develop large-scale flood hazard models to improve glacial flood forecasts and identify

future outburst hazards across northwest North America. Using field and remote sensing data, the study will produce physically based models of glacier evolution and outburst floods to identify and quantify how flood hazards will continue to change.

“Understanding glacier retreat and its effects on outburst floods is critical for mitigation and adaptation,” said David Rounce, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering and co-principal investigator on the project. “Improving our flood prediction models will help communities develop effective early warning systems and adaptation strategies.”

The study centers on the Juneau-based Áak’w T’áak Glacier (Mendenhall Glacier), which regularly produces outburst floods that have been monitored since 2011, including the 2024 disaster. While the team will conduct its fieldwork there, they will use models to investigate changes in hazards for all of Alaska

and western Canada. Alaska’s diverse landscapes and climates reward researchers with data that is widely applicable, including to regions like High Mountain Asia, where they experience similar glacier flood threats. Subsequently, researchers are optimistic that the knowledge gained could be useful for better understanding changes in hazards globally.

“As glaciers continue to change, understanding and predicting their impact on communities becomes more crucial,” explained Rounce. “Our goal is to enhance current flood forecasting models, helping communities better prepare for and respond to the growing threat of glacier outburst floods.”

This five-year project is led by the University of Alaska Southeast and conducted in collaboration with the State of Alaska Department of Geological & Geophysical Surveys.

Mendenhall Glacier retreat comparison from 1893 to 2018

Source: NOAA climate.gov

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University are improving weather forecasting models so that they better represent air pollution, aerosols, and their effects on fog. Fog reduces visibility, with implications for safety and the economy, especially associated with air and sea transportation.

Most weather forecasting models do not accurately represent the fog lifecycle: when it starts, how thick it is, and when it dissipates. Hamish Gordon is addressing these shortcomings in the existing models by improving the representation of droplet number concentration and size. These fog properties are strongly impacted by air pollution. In polluted environments, more and smaller droplets restrict visibility more than fewer and larger droplets.

Working with the UK Met Office Unified Model as the baseline, Gordon and CMU collaborators are adding new code to better represent air pollution particles, or aerosols, and fog.

Researchers at India’s National Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasting (NCMRWF) and the UK Met Office used that work as the basis for a new weather forecasting system published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. They show the integration of an aerosol air pollution forecasting system with other systems to provide real-time forecasts of visibility and PM 2.5 for Delhi and the neighboring regions.

A reliable air quality and visibility forecast can impact public health and minimize economic losses. The weather forecasting system in Delhi shows how Gordon’s model can be applied to provide operational products for industrial partners, like airports. In Delhi, air pollution is high and has a large effect on visibility. “The idea is to forecast low visibility events. This will allow airports to anticipate disruptions, flight delays, and potentially make preparations for such situations,” says Gordon, associate professor of chemical engineering.

“THE IDEA IS TO FORECAST LOW VISIBILITY EVENTS. THIS WILL ALLOW AIRPORTS TO ANTICIPATE DISRUPTIONS, FLIGHT DELAYS, AND POTENTIALLY MAKE PREPARATIONS.”

- HAMISH GORDONASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, CHEMICAL ENGINEERING

Since introducing the forecasting system in 2021 in the Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, Gordon and his collaborators have significantly improved it. In order to represent visibility, the model has to represent air quality, at least in a simple way. The baseline Unified Model represents atmospheric particles at 100-kilometer grid resolution. Gordon adapted this modeling system for use at higher resolution.

He and his collaborators were the first to use the modeling system to represent differences in air pollution across cities and across cloudy environments, at grid resolutions of 500 meters and 330 meters. The ability to represent gradients of air pollution at these fine scales enables the model to represent large cloud systems.

The researchers at NCMRWF also integrated the air pollution system with the latest and best land surface modeling environment. The land surface model is well-adapted for urban environments because it represents street canyons. Its integration means that the weather forecasting system can better forecast air quality in Delhi, and this development could be beneficial elsewhere, including the United States.

Delhi has unique conditions that make it particularly challenging to predict visibility. High levels of particulate matter air pollution are often accompanied by episodes of dense fog. Seasonal agricultural fires are one contributor. In the fall, farmers in the regions surrounding Delhi burn the stubble in their fields.

Earth System models don’t typically represent day-to-day variability in agricultural burning, and they also don’t represent it at high grid resolution.

The NCMRWF model represents fires on a daily timescale and uses them in visibility forecasts. Local irrigation activities also need to be treated in detail in the weather forecasting system because they affect relative humidity, which in turn affects fog.

The CMU researchers also use case studies from other parts of the world to realistically simulate fog droplet concentrations in a weather forecasting model. They test different processes for aerosol activation, the process by which air pollution particles become fog droplets.

Without accurate representation of aerosols, weather prediction models cannot accurately predict

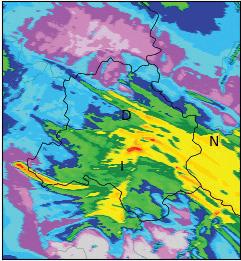

DM-Chem (330m)

24 Hr Fcst Valid on 2025-02-11 00:00:00Z

Visibility

D=New Delhi I=IGI Airport N=NCMRWF

Visibility in the region around Delhi, India on February 11, 2025, as predicted by the weather forecasting system developed by India’s National Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasting, Hamish Gordon, and the UK Met Office. Source: India’s National Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasting

clouds or fog. Aerosol particles can range in size from approximately 20 nanometers to a few microns. Most field campaigns do not measure the entire range; however, in another study, Gordon’s team uses observational data from the ParisFog field campaign, which measured the entire aerosol size range for two weeks, along with other aerosol properties. The research is a collaboration with the UK Met Office, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, and the National Centre for Meteorological Research in France.

Gordon and Pratapaditya Ghosh set up simulations over Paris and evaluated the Unified Model against the ParisFog dataset. By making physics-based changes in how droplets form in the model, they got much better agreement with the observations. Their methods for simulating fog droplet number concentration can improve fog forecasts without increasing computational costs.

“Our model is able to simulate fog at the correct location, with broad characteristics, in

good agreement with observations,” says Ghosh, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

Existing models are designed to calculate cloud droplet number concentrations. The mechanism by which fog forms, however, differs slightly from the mechanism by which clouds form. Most atmospheric models do not account for this difference.

When Gordon and Ghosh added the fog formation mechanism, radiative cooling, into the Unified Model, its performance improved. Their research suggests that both the fog formation mechanism and the cloud formation mechanism are important in atmospheric models. Gordon and Ghosh call for more evaluation in different locations and with different types of fog. More accurate models can help minimize health and economic losses while advancing the understanding of atmospheric processes underlying air pollutionweather interactions.

After measuring the gaps in EV charging coverage across the country, researchers find significant work lies ahead in deploying charging infrastructure, especially among rural areas.

Although electric vehicles (EVs) present a considerable opportunity to lower our greenhouse gas emissions, EVs currently only account for 1% of vehicles on the road in the U.S. One reason consumers have reported hesitation in purchasing EVs is “charging anxiety,” or concerns about losing power without access to a nearby, quick, and reliable charging station.

To instill confidence in buyers and encourage EV adoption, the federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) program is helping to deploy fast chargers along select main highway routes called alternative fuel corridors, or AFCs. Despite this investment, large gaps stretch between charging stations in many parts of the country, disproportionately affecting rural counties and inhibiting long distance travel.

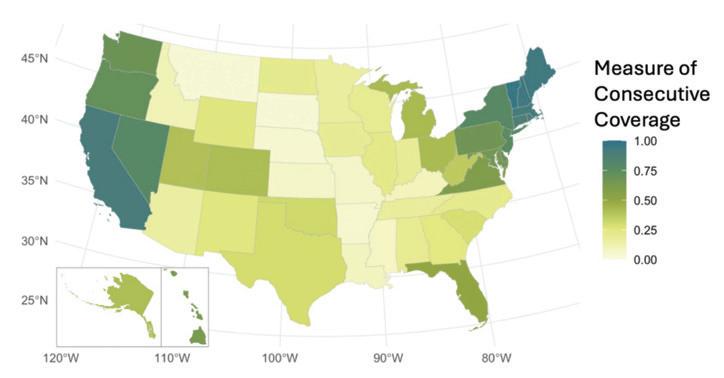

Seeking to better understand the current and future state of EV charging coverage in the U.S., researchers from Carnegie Mellon University’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering are assessing consecutive charging coverage on all National Highway System roads. In research published in Nature Communications, the team evaluates individual states and counties by the percentage of roads, weighted by traffic, that are without 50-mileor-more-long gaps between charging stations within 500 miles of any given county.

“There is a chicken and egg problem with EVs and charging infrastructure. Charging stations need EVs to be profitable, but consumers hesitate to purchase EVs due to a perceived lack of chargers,” said Corey Harper, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering. “Using our metric, we found that many states have a long way to go before we

achieve the consecutive coverage that would ease the minds of potential buyers.”

The team discovered that states such as California, Nevada, and those in New England generally have adequate charging coverage when looking at stations with slower charging speeds and fewer chargers per station. But, when implementing NEVI-compliance standards, which mandate at least four fast chargers per station, the effective coverage area shrinks. Consequently, while drivers in these states can find a charger every 50 miles, they may face wait times and queues due to lower power ratings and fewer chargers available at each station.

Even with NEVI’s plan to install fast charging stations along AFCs, while the northeast, California, Nevada, and Arizona would achieve continuous charging coverage, more rural states such as North and South Dakota, Arkansas, and Texas could not provide the same level of assurance for EV drivers. NEVI would need to deploy charging stations on 1,900 road segments to meet the plan’s goals, and this number rises to 4,500 segments to extend fast consecutive charging coverage to all highways, including those rural states.

To expedite this process, EV manufacturer Tesla has made arrangements to open some of their Supercharger network and share their connector design with select car manufacturers. However, the full potential of this collaboration remains untapped. Making the Tesla charging network universally accessible could have a huge impact on the cost and labor in realizing NEVI’s vision.

“By adding magic docks to Tesla Superchargers or open sourcing their connector design, we could achieve fast consecutive charging coverage with 500 fewer new stations,” said Harper. “We estimate that this could save between $166 and $332 million in NEVI programming costs.”

The team believes their findings can help policymakers and consumers navigate the realities of EV charging access. Looking forward, they hope to extend their research to medium and heavy-duty electric trucks, for which charging access lags significantly behind that of everyday cars.

“Ultimately, we hope to inform policy development at both the federal and state levels and show that while most of the country will have sufficient coverage once AFCs reach NEVI-compliant status, additional work needs to be done to ensure charging access in rural areas,” Harper explained.

“One of the largest values of this study is understanding the true range limitations for the national build out of EV infrastructure,” said Destenie Nock, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering. “Often we talk about the distance capabilities of gas compared to electric cars. Now, we have a forward-looking method for estimating the range limitations."

I’M WORKING ON METHODS THAT WILL NOT COMPROMISE THE SECURITY OR PRIVACY

- SARAH SCHEFFLER ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ENGINEERING AND PUBLIC POLICY AND SOFTWARE AND SOCIETAL SYSTEMS

You may not be aware that while completing routine tasks online such as text messaging with friends, sharing a link with a colleague in a Zoom meeting chat, or accessing a website with an “HTTPS” protocol, you may be taking advantage of a cryptographic security method called end-to-end encryption, or E2EE.

E2EE ensures data is encrypted on a sender's device and remains encrypted until it reaches the intended recipient. This means that no third party—including service providers, hackers, or even government agencies—can access the data while it is being transmitted.

“The privacy and security that are facilitated through cryptography are all about keys,” explains Sarah Scheffler, assistant professor of Engineering and Public Policy and Software and Societal Systems. “Only parties that have a key can complete a certain function or task.

“What makes end-to-end encryption special and separates it from other types of communication we do online, is that the ends of the communication, which means you and the person or people you're talking to, have the keys. But the server that is facilitating that communication does not have the keys. That makes it both more secure and more private.”

E2EE benefits privacy and security amongst users, but it also complicates platforms’ ability to moderate user content. Policymakers are concerned that encryption will make it impossible to detect, flag, and remove especially harmful content such as child sexual abuse material (CSAM), violent imagery, terrorist or extremist content, and misinformation.

To help navigate this trade-off, Scheffler is currently conducting research focused on understanding the landscape of child safety

reports, identifying oversight challenges in moderation of violent extremism, building technologically verifiable transparency reports and cryptographic methods to verify the accuracy of content scanning, and exploring alternative content moderation methods for E2EE that are still private and secure.

“Our current approach to scanning for CSAM on unencrypted platforms is match-list based. The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children has a big list of all the CSAM that's ever been reported to them, social media companies report new CSAM to them, and that list is used to detect other CSAM content on their platforms,” explains Scheffler. “A similar approach is taken for terrorist content, with a list maintained by the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism.

“AI definitely changes the picture both for the content sent and the ways to detect it. I’m working on methods that will not compromise the security or privacy of E2EE while being realistic about the scanning capabilities of modern technology.”

While Scheffler’s research focuses on technological solutions to improve content moderation both in E2EE and otherwise, she also emphasizes the need for clear public policy to prevent the slippery slope of content scanning. She suggests that not all scanning needs to cause a “report” to leave a device, and that policymakers should limit content scanning to specific purposes, such as child safety and counterterrorism.

“E2EE isn’t going away anytime soon, and content moderation isn’t going away anytime soon, either,” Scheffler said. “A lot of my work is trying to figure out, ‘given the technology we have now, and that we’ll have soon, how can we reconcile all the different goals we have?’”

The adoption of decarbonized production methods in heavy manufacturing industries is widely considered a key step toward global climate change mitigation. For communities where these industries have a strong presence, the workforce implications of decarbonization can feel just as significant, and more immediate.

Researchers in Carnegie Mellon University’s College of Engineering have developed a generalizable approach for analyzing the impact of such decarbonization scenarios on a region’s workforce.

“Our research approach aims to reduce uncertainty and help stakeholders plan for a technology transition rather

than being blindsided by impacts that they may not have anticipated or projected,” said Valerie Karplus, professor of engineering and public policy (EPP) and associate director of the Scott Institute for Energy Innovation.

In a study published in PNAS, the researchers used their multi-step methodology to simulate the impact of such a transition on the existing steel industry workforce in Southwestern Pennsylvania. They looked at the workforce impact of transitioning from integrated steelmaking, a greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions-intensive process, to electric arc furnace (EAF) production, with or without a direct-reduced iron plant to supplement steel scrap as an iron input on the same site.

Replacing integrated steel plants with EAFs is possible today for a growing range of steel products. EAF steelmaking in the United States is already more common than the integrated route, which is one reason why steel produced in the United States has a lower GHG footprint on average than its global counterparts. Iron and steelmaking account for 2% of GHG emissions in the United States, and around 7% of global GHG emissions.

Still, such transitions have historically led to major workforce disruptions in local economies. The approach the CMU team developed can help communities to navigate these transitions by providing a common fact base for stakeholders to work from and plan for coming change, potentially avoiding or addressing its most negative effects.

“Often there are frictions to advancing decarbonization efforts because of uncertainty in job outcomes,” said Jillian Miles, a Ph.D. student in EPP and lead author on the paper. “This research can help quantify and clarify those effects.”

The team’s analysis suggests that the current integrated steelmaking workforce has the skills, knowledge, and abilities to fill more than 95% of the jobs required by an EAF facility. However, the number of jobs at such a plant is only 25% of what an integrated plant requires. Further, while some types of workers would have high chances of success in the broader labor market, some groups—such as production workers—may be unlikely to find positions that match their skills, knowledge, and abilities while maintaining their approximate salaries and geographic location.

These findings may sound alarming on their own, but the methodology the engineers developed can empower lawmakers, workforce boards, and other relevant entities to create proactive plans based on realistic outcomes.

“The case is one of a specific steel plant in Southwestern Pennsylvania, but the big picture is, industrial decarbonization and other industry transformations will affect the composition of labor in U.S. manufacturing and work environments,” said Christophe Combemale, assistant research professor in EPP and co-lead of the Workforce Supply Chains Initiative at the Block Center for Technology and Society.

“This is a repeated problem that looks a little different each time, and what we have built is the capacity to attack these kinds of problems rapidly,” he added. “We can identify which occupations and groups will be the most vulnerable and get ahead of these impacts, ideally before they are felt.”

Additionally, the team has applied the methodology to examine readiness of regions in the United States to host battery manufacturing plants and has also started working with areas that historically relied heavily on coal mining to explore how the approach can inform future workforce strategy, Miles noted.

Chris Pistorius, associate department head and POSCO professor in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, also contributed to this research.

Researchers have developed an approach for analyzing the impact of decarbonization in heavy manufacturing industries on a region’s workforce.

Wei Li has developed graph and large language model based approaches for a novel computer chip design to support AI and other applications, making technology more efficient.

Computer chips are the foundation of technology. From smart phones to computers to GPUs, one of the driving forces behind our technical lives can be drilled down to the power of a computer chip. Engineers are constantly seeking ways to make computer chips faster, with more processing cores, and lower power consumption to keep up with consumer demands.

Wei Li, a Ph.D. candidate in the electrical and computer engineering department at Carnegie Mellon University, is developing a novel graph and large language model (LLM) based approach to optimize the chip design process to make artificial intelligence (AI) applications more efficient.

Every action on a digital device, from launching an app to playing a game, is translated into machine instructions for the graphics processing unit (GPU) or processor to execute. These instructions consist of sequences of binary digits (1s and 0s). A simple task might require thousands of instructions, while a complex operation, like gaming, can execute billions of them in seconds.

Fundamental hardware components that process these instructions include logic gates. A logic gate is a microscopic circuit that performs a basic logical function. For example, a common type known as an ‘AND’ gate will only output a '1' when all of its inputs are '1'; otherwise, its output is '0'.

“The millions of logic gates on a single chip are interconnected in a vast network that closely resembles a complex graph structure,” explains Li.

This representation is key to modern innovation.

“By viewing the chip's design as a graph, we can apply artificial intelligence and LLMs to analyze and improve it,” explains Li. “My career goal is to develop and revolutionize the next generation of design and test flow methods, ultimately driving better performing computer chips.”

Li’s novel graph-supported LLM for EDA tasks is just one of many innovative projects that he is working on. Due to his forward thinking and passion for inventing new processes for technology design, his co-advisors, Shawn Blanton, the Joseph F. and Nancy Keithley Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering, and José M. F. Moura, the Philip L. and Marsha Dowd University Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering, refer to him as “New Way.”

“I continue to be in awe of Wei Li’s research ideas and execution,” says Blanton. “He is constantly finding new ways to solve challenging problems. That mindset is crucial in today’s ever changing technology world. We are fortunate to have Wei in the Carnegie Mellon Engineering family.”

Li tributes his research ethos to his numerous internships at prestigious companies, as well as the opportunity to study under multiple distinguished professors at different universities.

“You can say my new ways are really coming from those experiences,” says Li.

The recipient of many prestigious fellowships and awards, Li was a highly sought-after Ph.D. candidate. He ultimately enrolled at Carnegie Mellon University because of the varied domains offered by the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

“My advisors grant me the opportunity to learn

To hear more from Li about his research, watch the video

from both ends of the computer chip spectrum,” says Li. “Professor Blanton focuses on the physical aspect of computer chips, while Professor Moura is an expert in signal graph processing. It’s a unique offering to be advised by skilled professors in both domains, which positively impacts my research findings.”

Drawing from both hardware and algorithmic perspectives, Li is developing chip designs that could help deliver more powerful and reliable electronics for everyone.