Continuing Education program

- June Modules

Jan

2023

Continuing Education Program 2023 STUDY GUIDE

The Continuing Education Program 2023 Study Guide relates to the following National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards:

Every effort has been made to trace and acknowledge copyright material. Should any infringement have occurred accidentally the authors and publishers tender their apologies.

Copying

Except as permitted under the Act (for example a fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review) no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All enquiries should be made to the publisher at the address below.

Chief Executive Officer

SA Ambulance Service

GPO Box 3

Adelaide SA 5001

Published by: Clinical Education, SA Ambulance Service

OFFICIAL OFFICIAL 2

Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023

Version 1.0 221031

Contents

Introduction 6

What Modules Must be Completed From January-June 2023 6

Reaccreditation 6

CEP Record Keeping 6

Scope of Clinical Practice 7

Providing Clinical Care When Off Duty 7

Delirium 8 Learning Outcomes 8

Introduction 8 Delirium 9 Causes of Delirium 10

Delirium Risk Factors 10 Recognising Delirium 11 Management of Delirium 12

Summary 12

Infection Prevention and Control 13

Introduction 13 Learning Outcomes 13

Infectious Disease 13

Infection Prevention and Control 19

Standard Precautions 19

Routine and Scheduled Cleaning 27

Safe Handling and Disposal of Waste 33

Transmission-Based Precautions 34

Immunisation 36

Managing Occupational Risk and Exposure 36

Out of Hospital Cardiac Arrest (OHCA) Reaccreditation 39

Learning objectives 39 Introduction 39 Covid-19 39

Does Training Influence Patient Outcomes? 40

Cardiac Arrest: The Theory 41 Why Have They Arrested? 41

What About Cardiac Rhythms During Cardiac Arrest? 45

High-Performance CPR 48

Physiology Of CPR 48

Defibrillation 52

Special Circumstances 54

Approach To Airway And Ventilation Management 55

Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023

Continuing Education Program 2023 STUDY GUIDE OFFICIAL OFFICIAL 3

Cardiac Arrest Choreography - Pit Crew CPR 57

Mobile CPR 61

Post-Rosc Care 63

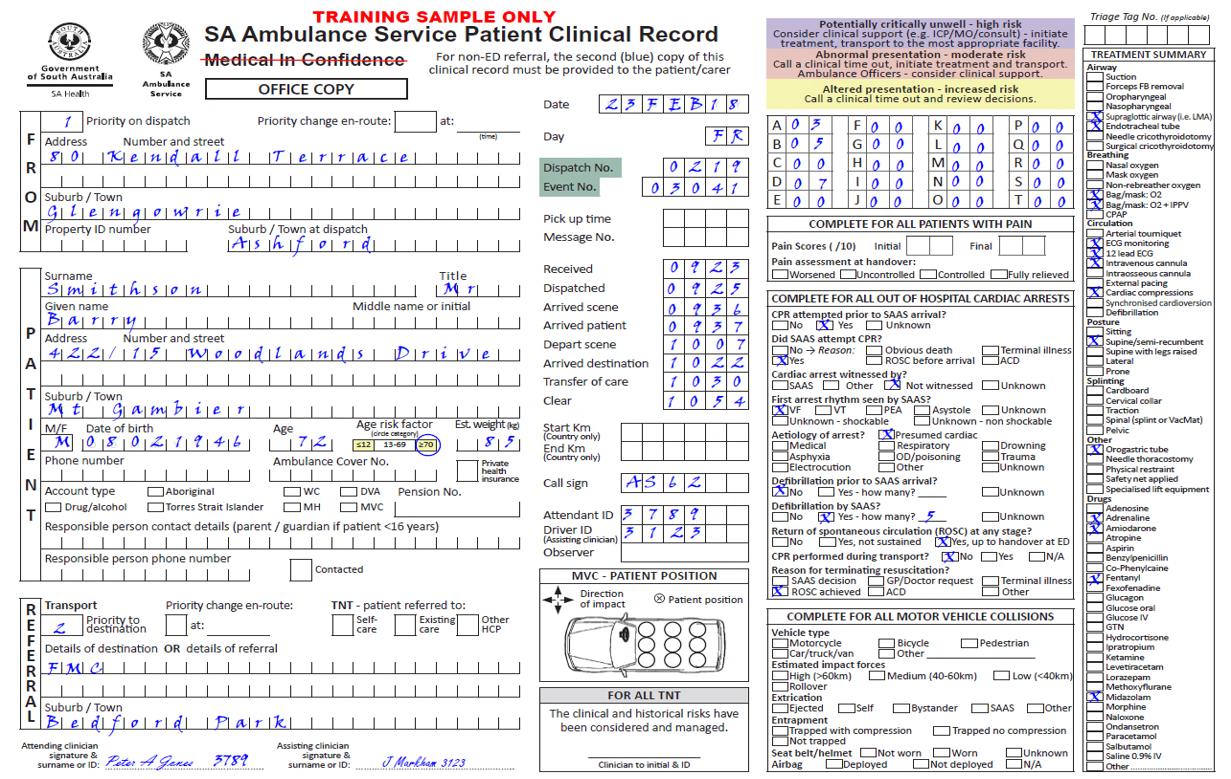

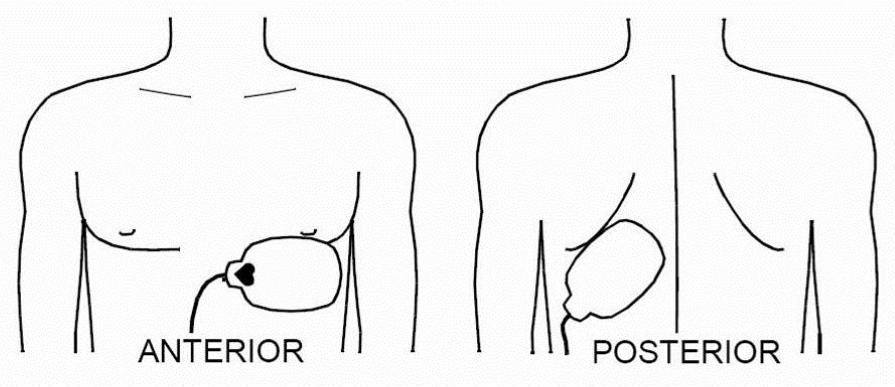

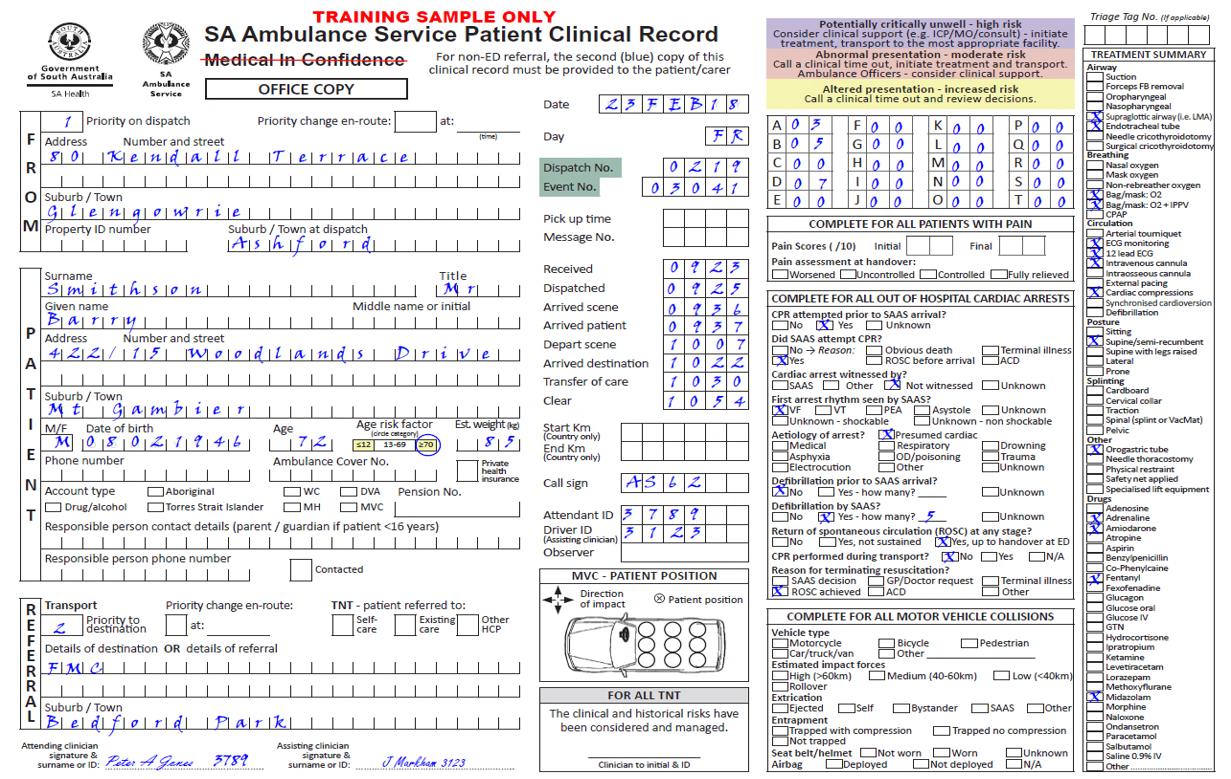

What’s Documentation Got To Do With Cardiac Arrest Management? 65

Reconciliation Action Plan: Asking the Question 70

Learning Outcomes 70

The Question 70

How to Ask the Question: 71

Tips for Asking the Question: 72

Exceptions on When to Ask the Patient 72

Strategies If Not Well Received: 72

Prepared Answers 72

Research on Why Patients Should Be Asked 73

Cultural Reason Why Patient’s Should Be Asked 76

Asking the Question, and Recording the Answer 76

Summary On Why It’s Important to Ask Every Patient 77

Glossary 78

Continuing Education Program 2023 STUDY GUIDE OFFICIAL OFFICIAL 4 Continuing Education

Program 2023 - Jan 2023

eBook Symbol Key

Click on this icon to play a Video

Click on the orange text to be taken to the Glossary definition for that word. Click on the word in the glossary to return to its reference.

Click on this icon to be taken to a page in a related eBook/learning materials

Click on this icon to view a Clinical Practice Protocol on the web version of the SAAS Clinical App.

SAASNET Links

Click on the following icon to open resource found on SAASnet.

Click on this icon to play Audio

Click to return to the Contents page

Click to open a link to an external website

Click on this icon to be taken to related SAAS eLearning courses. You will need to login to view the course

Please ensure you are logged into the intranet prior to clicking on the icon.

Relevant Clinical Practice Procedure documents

Opens relevant Information Notices

Opens relevant Procedures

Opens relevant intranet pages and resources.

Opens relevant Policies

Opens relevant Safety Alerts

Opens relevant SA Health Guidelines and Directives

Continuing

Continuing Education Program 2023 STUDY GUIDE OFFICIAL OFFICIAL 5

Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023

Introduction

What Modules Must be Completed From January-June 2023

All modules must be completed as outlined in the table below. Other SAAS or SA Health modules may be deemed necessary based on work location/role. For any additional information please discuss this with your Regional Team Leader (RTL).

Semester 1 Modules

BLS

Ambulance Assist Ambulance Responder Ambulance Officer

Each module below has been designed as an educational resource for operational volunteers at an Ambulance Assist (AA), Ambulance Responder (AR) or Ambulance Officer (AO) level.

When completing each module operational volunteers should remember to safely perform any set task or skill demonstration to the level within their scope of practice, to follow their specific Clinical Practice Protocols (CPPs) and comply with SAAS procedures.

This hard copy study guide is provided to assist volunteers with poor internet access or who desire a hard copy of information in addition to the eLearning modules. The online material is more comprehensive with the added advantage of embedded skills and real-life case videos, files and web links. Certain modules have short quizzes that must be completed online. Discuss with your RTL if this poses an issue for you. RTLs will be able to guide you on how to complete these on your own personal computer, SAAS station computer or SAAS issued iPad.

Reaccreditation

This is an annual process of completing skill and competency assessments, skills demonstrations, and declara- tions; to ensure all members retain full awareness and competency in the tasks and requirements of their assigned level of accreditation, and to prove their ability to perform work safely to the level of their accreditation. An opera- tional volunteer can only re-accredit at a level in which they have gained an initial accreditation. Re-accreditation contributes to the member’s efficiency status. If an operational volunteer is unable to complete the requirements of this Continuing Education Program (CEP), discuss your options with your RTL as this may result in restriction or removal of your Scope of Clinical Practice.

CEP Record Keeping

All volunteers should keep a copy of each individual modules certificate of completion, ideally, the Regional Team Leader (RTL) should keep a portfolio for each volunteer.

Note: Module completion certificates and any skill demonstrations/consolidations completed as part of face-to-face sessions do not need to be sent in, volunteers should keep them as a record of the training. Your RTL will complete a ‘Declaration of Evidence’ checklist on SAAS eLearning as each 2022 CEP topic has been completed.

Note: Volunteers and Regional Team Leaders should ensure that copies of the module completion certificates are kept.

6 Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL Continuing Education Program 2023 STUDY GUIDE

Reaccreditation YES YES YES Delirium OPTIONAL OPTIONAL YES

Infection Prevention and Control YES YES YES Mask Fit Check YES YES YES

OHCA Reaccreditation YES YES YES

Reconciliation Action Plan: Asking the Question YES YES YES

Scope of Clinical Practice

On completion of your relevant training program (qualification), SAAS will issue you with a Scope of Clinical Practice. There are multiple levels of credentialing within SAAS volunteer operations, these include:

• Ambulance Assist (AA)

• Ambulance Responder (AR)

• Ambulance Officer (AO)

• Ambulance Officer (Advanced Skills – Pain Management)

• Ambulance Officer (Extended Practice for Registered Health Professionals)

Each level within SAAS has a defined scope of practice. This scope of practice is defined through clinical documents such as policies, clinical practice protocols, clinical practice procedures and clinical communications. These documents are available on the SAAS Policy and Information Centre (SAASnet). A description of key relevant documents is provided below.

• SA Health Clinical Directives and Guidelines: Clinical policy directives and guidelines establish best practices across SA Health and assist practitioners and patients to determine appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances. Clinical policy directives are mandatory requirements that are implemented across SA Health as ongoing operational practice, whether it is a short-term or permanent direction, and must be complied with. There is no scope to deviate from the specifications within clinical policy directives.

• SAAS Clinical Practice Protocols: These are documents that dictate the course of action that will be followed in a clinical situation. They set out a minimum level of treatment which ensures that th e majority of cases are handled in a standard manner.

• SAAS Clinical Practice Procedures: These documents provide guidance in the implementation of clinical skills including the application of clinical devices, use of equipment and approaches to clinical care. They are intended to demonstrate and promote best practices.

• SAAS Clinical Communications: Clinical Communications are issued when there is information or clarification that needs to be brought to the attention of the country and me tropolitan operations staff regarding a clinical practice issue.

Your clinical practice must be conducted within your scope of practice in accordance with established SAAS policies, procedures, pathways and protocols, using approved equipment and medications. SAAS staff are not permitted to conduct clinical practice outside their defined scope of practice unless specifically authorised to do so, this must only be done in consultation with a SA Ambulance Service Medical Officer. Where any variation to clinical practice has occurred, the case must be highlighted to your clinical supervisor, usually your Regional Team Leader (RTL), for review.

Providing Clinical Care When Off Duty

Off duty, SAAS staff are authorised to provide clinical care to their approved scope of clinical practice providing that they make their presence known to the ambulance service at the time (usually during the 000 calls). This must occur if intending to apply clinical judgement which may consist of advice and/or treatment. SAAS provides indemnity once notification occurs, staff are then covered as if they were on shift or duty within the jurisdictions of the service.

Examples of this situation include:

• Chancing across a vehicle crash while driving to work

• Assisting an injured player while watching your children’s sports team play

If notification is delayed it should be made as soon as possible to the State Duty Manager. Do not delay emergency treatment to initiate notification. Notification can be made by informing the EOC of your presence during the 000 calls or contacting the State Duty Manager directly.

This coverage and authorisation do not apply when the SAAS volunteer is acting in an official capacity for instance working or volunteering for another ambulance or medical provider (e.g. PTS, event or industrial company). In these circumstances, your practice and insurance are determined by the provider you are working for.these circumstances, your practice and insurance are determined by the provider you are working for.

Policy - Credentialling and Defining the Scope of Clinical Practice

7

OFFICIAL OFFICIAL Continuing Education Program 2023 STUDY GUIDE

Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023

Delirium

Learning Outcomes

• Recognising delirium

• Understanding the causes of delirium and risk factors

• Having an awareness of the paramedic/ICP 4AT Tool

Introduction

Delirium is a common and serious problem among acutely unwell persons. Delirium is linked to higher rates of mortality, institutionalisation and dementia and is generally underdiagnosed. While detection and management of delirium is traditionally a hospital-based entity, there may be a benefit in recognising delirium in an out-of-hospital environment and communicating this risk during the transfer of care.

Most delirium lasts a few days, but in some cases (around 20%) it lasts longer and can take weeks or even months to resolve. In some patients, there is only partial recovery and they do not return to their pre-delirium state.

People with delirium can present in different ways. The primary abnormality is inattention, ranging from being barely responsive to voice (severely reduced level of arousal), to being unable to engage in simple conversation and follow simple commands, to more subtle difficulties in maintaining focus over periods of 10-15 seconds.

8 Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL <Section/Chapter Heading>

DELIRIUMCEP 2023

Delirium

People who can communicate when affected by delirium are usually confused and often show an impaired understanding of what is happening to them. They are often distressed and anxious. They may also believe that they are at personal risk, for example feeling that they have been imprisoned or that people who are offering assistance are trying to harm them. Visual hallucinations are also common and can be very frightening.

Some people with delirium can appear very restless and hyperactive. This is often a consequence of fear in that they feel unsafe and want to leave to reach a place of safety or to be with family.

During a period of delirium, the features can come and go (fluctuate). For example, a patient may be confused, disorientated and fearful at one point overnight but appear calmer and less confused hours later.

People with dementia have a higher risk of developing delirium. Dementia is different to delirium as it is typically caused by anatomical changes in the brain.

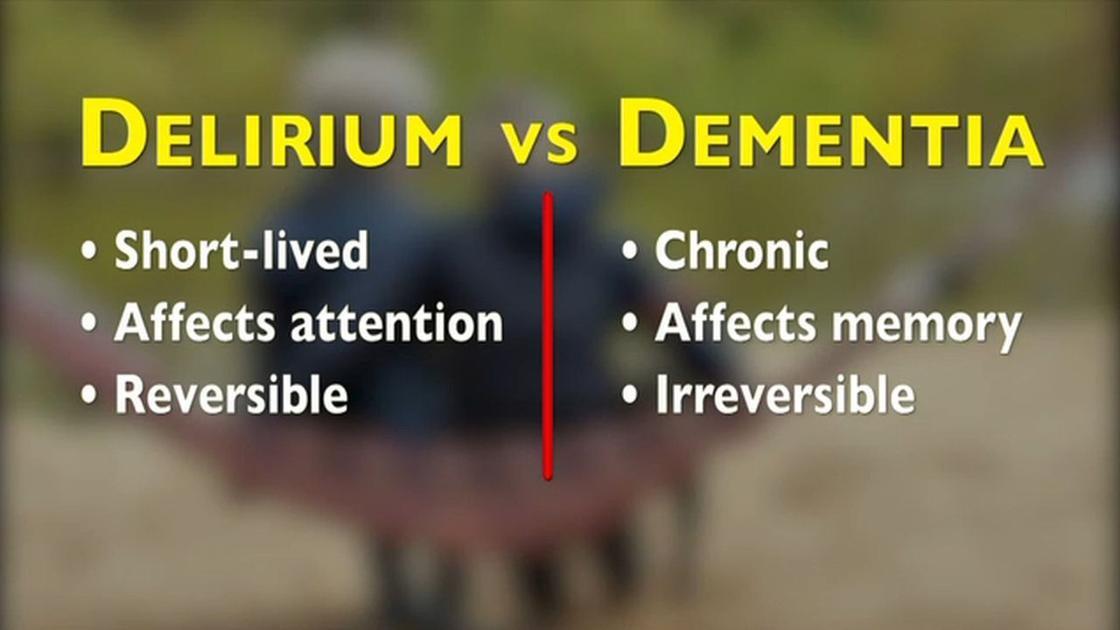

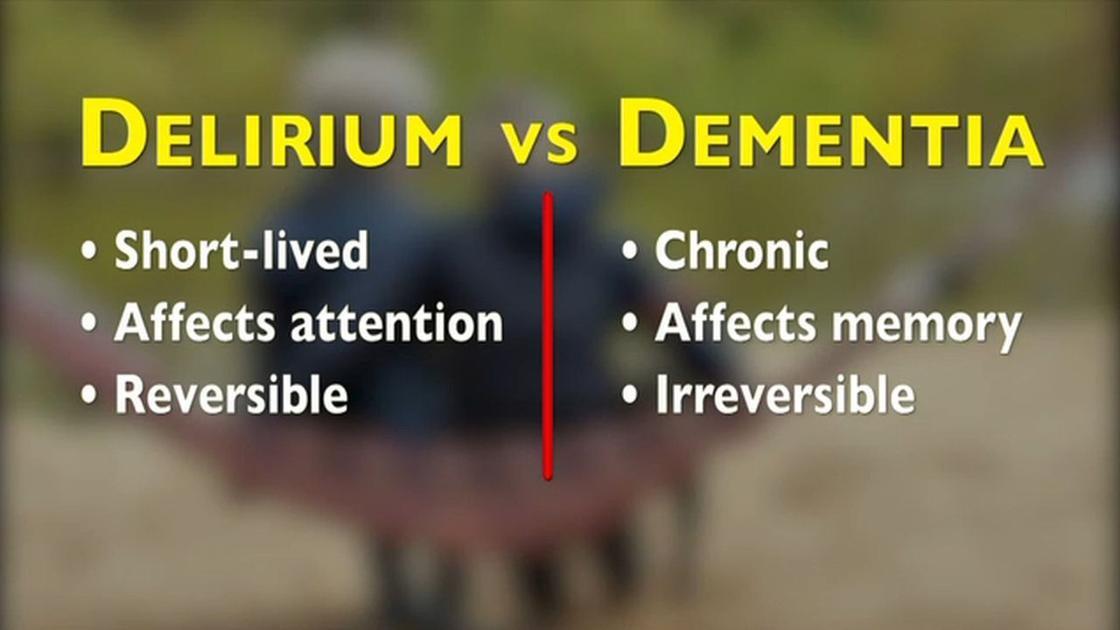

The differences between delirium and dementia are that dementia is a gradual onset, affects memory and is not reversible and usually progresses over time. In contrast, delirium develops rapidly, profoundly affects attention and is potentially reversible.

9 Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL DELIRIUM - CEP 2023

Causes of Delirium

Delirium is caused by anything that can rapidly disrupt brain functioning. There is a long list of potential acute medical causes, including infections, trauma, surgery, constipation, drug side effects (e.g. opioids or benzodiazepines), and sudden drug withdrawal (e.g. antidepressants).

Physiological and metabolic changes happening simultaneously as acute illnesses such as hypoxia, hypercapnia, hypoglycaemia, high or low sodium, or high calcium can also directly cause delirium. Acute psychological stress caused by changes in environment, pain, discomfort, disorientation, fear, isolation, and sleep disruption, can also trigger delirium, particularly in patients with dementia.

Delirium - causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment & pathology [7:38 mins] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qmMYsVaZ0zo

Delirium Risk Factors

Although delirium can occur in any person, increasing age, dementia, frailty, multiple co-morbidities, and sensory impairments all increase the risk of delirium.

Delirium can occur as a result of predisposing risk factors such as severe medical illness or precipitating factors such as changes in the environment that can trigger the onset.

Predisposing Risk Factors:

• Age >65 (>45 for Aboriginal and or Torres Strait Islander people)

• Pre-existing dementia

• Severe medical Illness

• History of previous delirium

• Visual and hearing impairment

• Depression

• Abnormal sodium, potassium and glucose

• Polypharmacy

• Alcohol/ Benzodiazepine use

Precipitating Risk Factors

• Use of physical restraint

• Use of an indwelling catheter

• Altered or multiple medications

• Change in environment

• Pain

• Surgery

• Anaesthesia and hypoxia

• Malnutrition and dehydration

10 Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL DELIRIUM - CEP 2023

Recognising Delirium

Signs and symptoms of delirium usually begin over a few hours or a few days. They often fluctuate throughout the day, and there may be periods of no symptoms. Symptoms can worsen during the night when it’s dark and things look less familiar.

Gathering a history from the patient’s family or carers who know the person is essential and should confirm that there is an acute change from the person’s usual mental state and behaviour.

Early identification and notification at the handover of patients at risk are important so that effective interventions can be put in place. Prompt diagnosis and timely treatment of underlying causes are important for reducing the severity and duration of delirium, and the risk of complications that arise from it(2).

A variety of screening tools are used in Emergency Departments and out-of-hospital settings to assist in the early detection and recognition of delirium

SAAS paramedics and ICPs will be implementing the use of the 4AT Rapid Clinical Test for Delirium in patients who are presenting with or at risk of developing delirium.

Ambulance Officers are not required to use this tool however it is good to have an overview of the assessment process that is undertaken. Below are the 4AT charts paramedics and ICPs use to assess the patient. The chart is available for use by paramedics and ICPs in the SAAS clinical app.

11 Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL DELIRIUM - CEP 2023

Management of Delirium

If you suspect delirium during an episode of care several management options should be considered:

• Correct any underlying contributors or causes of delirium such as pain or hypoglycaemia.

• Ensure communication with the patient is suitable to their circumstance. Simple and direct questioning, explanation and instructions may be required.

• Ensure you have introduced yourself, talk slowly and calmly and ensure respectful non-threatening behaviours.

• People with delirium are often distressed. Look for signs of distress, ask if the patient has specific concerns and take opportunities to reduce distress.

• Reduce noise and environmental stimuli where possible.

• Ensure they have their glasses and hearing aids.

• Keep the patient informed, offer reassurance and involve family and carers in decisions and care where possible.

Summary

Delirium is often associated with poor patient outcomes and it is likely that the more severe and longer the episode of delirium, the poorer the outcome. It can have drastic short and long-term consequences for the person such as falls, a decline in their physical strength and function, early admission into residential care, increased healthcare utilisation and costs, and increased risk of death. Some people who have had delirium may never return to their former cognitive or functional capacity.

Traditionally delirium detection and management exist in a hospital-based environment. Recognising symptoms of delirium in a pre-hospital environment and communicating the information to the receiving hospital during the transfer of care may improve patient outcomes.

12 Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL DELIRIUM - CEP 2023

Infection Prevention and Control

Introduction

Infection prevention and control (IPC) is a practical, evidence-based approach to preventing patients and health workers from being harmed by avoidable infections.

Effective IPC requires constant action at all levels of the health system, including policymakers, facility managers, health workers and those who access health services.

IPC is unique in the field of patient safety and quality of care, as it is universally relevant to every health worker and patient, at every health care interaction. Inadequate IPC practices can lead to serious adverse events for patients and sometimes death. Without effective IPC it is impossible to achieve quality health care delivery.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this topic you will be able to:

• Follow standard and additional precautions for infection prevention and control

• Identify infection hazards and assess risks

• Follow procedures for managing risks associated with specific hazards

• Demonstrate an understanding of infection prevention and control policies and procedures

• Demonstrate correct hand hygiene processes

• Demonstrate the correct use of PPE supplied by SAAS for infection prevention and control

Infectious Disease

Infectious diseases are illnesses caused by an infectious agent. Infectious agents are microorganisms that cause communicable diseases. Most commonly these are bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites, and prions.

Not all microorganisms cause disease or illness, many of them are beneficial (e.g. the bacteria found in the digestive system). A microorganism that causes disease is called a pathogen.

Some infectious diseases can be passed from person to person, some are transmitted by an insect to other animals, and you may get others by consuming contaminated food or water or being exposed to organisms in the environment.

Signs and symptoms vary depending on the organism causing the disease but often include fever and fatigue. Mild infections may respond to rest and over the counter medications from the pharmacy, while some life-threatening infections may need hospitalisation.

Chain of Infection

What will I learn about the Chain of Infection?

• Identify the process for the transmission of disease

• Have an understanding of the significance of microbes and the role they play in causing infection

• Describe the means by which the transmission of disease can be prevented

• Identify potential sources of infection and the appropriate measures to prevent the spread of infection

Certain conditions must be met in order for an infectious agent to be spread from person to person. This process, called the Chain of Infection, can only occur when all six links in the chain remain intact.

The Chain of Infection describes the process of infection which begins when an infectious agent leaves its reservoir through a portal of exit and is transmitted by a mode of transmission, entering through a portal of entry, to infect a susceptible host.

13

OFFICIAL OFFICIAL <Section/Chapter Heading> Infection Prevention and ControlCEP 2023

Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023

Your role is to know when to use the precautions described in this course to interrupt the chain and limit the spread of infection.

Infectious agent

There are different types of microorganisms. These microorganisms may be harmless, harmful or beneficial to their hosts. Harmful ones are also called pathogenic microorganisms. These microorganisms may cause kinds of communicable diseases by competing for metabolic resources, destroying cells or tissues, or secreting toxins.

Bacteria

Bacteria are single-celled microorganisms that can exist either as independent (free-living) organisms or as parasites (dependent on another organism for life). Bacteria reproduce rapidly by dividing themselves into two cells. Bacteria are found in every habitat including soil, rock and oceans. However, very few bacteria are pathogenic and cause disease, some contribute to normal body function like bacteria found within the digestive system.

The following are some examples of bacterial infections:

• Whooping cough

• Salmonella

• Tuberculosis

• Meningococcal disease

• Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

• Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci (VRE).

Fungi

Fungi are a wide variety of microorganisms that include mushrooms, moulds, yeasts and mildews. Fungi reproduce by releasing tiny spores into the air. Fungi can be found in soil, water, plants and in the human body.

Some common fungal infections include:

• Tinea (athletes foot)

• Ringworm

• Candidiasis (thrush).

Viruses

A virus is a microorganism that can only reproduce inside the cells of a host organism. Viruses cause disease by taking over and altering normal cell functions in the host. The type of cell the virus infects will determine the symptoms and the severity of the disease.

14 Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL

Prevention and Control - CEP 2023

Infection

Some common viral diseases are:

• Measles

• Chickenpox

• Human Immunodeficiency Virus

• Influenza

• Common cold

• Novel Respiratory Pathogens e.g. SARS, MERS

Parasites

Parasites are microorganisms that live (grow, feed, shelter) on another species known as the host. Parasites usually enter the body through the mouth by way of contaminated food or water and some live on the skin and hair.

Some common parasitic infections include:

• Threadworm

• Scabies

• Head lice

• Giardia lamblia Reservoir

The reservoir (source) is a host which allows the pathogen to live and multiply. Humans, animals and the environment can all be reservoirs for microorganisms.

Humans

There are two types of human reservoirs:

• Cases (persons with a symptomatic illness)

• Carriers

Carriers can be further defined as:

• Asymptomatic: An infected individual that shows no symptoms. Although unaffected they can transmit the disease to others.

• Symptomatic: This state may occur during the incubation period, convalescence and post-convalescence of an individual with a clinically recognised disease (e.g. influenza). An example of a human reservoir is a person with a common cold.

Animals

Animals can also be reservoirs; they can be carriers of diseases that can be passed on to humans. An example of an animal reservoir is a dog or monkey with rabies.

Environment

Reservoirs in the natural environment are contaminated water, soil or plants. This also includes food that has been contaminated.

Man-made reservoirs include objects and surfaces which have been contaminated.

Examples of an environmental reservoir are standing water infected with Legionnaire’s disease or soil contaminated with tetanus spores.

15 Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL

Prevention and Control - CEP 2023

Infection

Portal of exit

Portal of exit is the path by which a pathogen leaves its host. The portal of exit usually corresponds to the site where the pathogen is localized. For an organism to be transmitted from one person to another it must exit the reservoir (this applies only to human or animal reservoirs). The key portals of exit include:

• Respiratory tract (infected phlegm expelled through coughing)

• Gastro-intestinal tract (infected vomit or faeces)

• Skin lesions (infected blood or pus)

• Mucous membrane (nasal discharge)

Modes of transmission

The mode of transmission is the mechanism of transfer of an infectious agent from a reservoir to a susceptible host. The major modes of transmission include:

• Contact Direct Indirect

• Droplet and airborne

• Common vehicle

• Vector Contact transmission

Contact is the most common mode of transmission and usually involves transmission by touch or via contact with blood or body substances. Contact may be direct or indirect.

Direct contact transmission

Direct transmission occurs when infectious agents are transferred from one person to another, for example:

• Contact with infected body fluids (e.g. saliva, urine, faeces or blood), via cuts/abrasions or through mucous membranes of the mouth or eyes.

• Penetrating injuries, such as needle stick injuries.

• Contact with soil, vegetation or water that has been contaminated with an infectious agent.

Indirect contact

Indirect transmission involves the transfer of an infectious agent through a contaminated intermediate object or person, for example:

• A healthcare worker’s hands transmitting infectious agents after touching an infected body site on one patient and not performing proper hand hygiene before touching another patient, or

• A healthcare worker using fomites/equipment (e.g. BP cuff, stretchers, monitoring equipment) that has not been adequately cleaned and then used on another patient.

Droplet transmission

Droplet transmission can occur when an infected person coughs, sneezes or talks, and during certain procedures. Droplets are infectious particles larger than 5 microns in size

Respiratory droplets transmit infection when they travel directly from the respiratory tract of the infected person to susceptible mucosal surfaces (nasal, conjunctival or oral) of another person, generally over short distances. The droplet distribution is limited by the force of expulsion and gravity, it is usually no more than 1 metre.

Examples of infectious agents that are transmitted via droplets include influenza virus and Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcal infection), Pertussis (whooping cough).

16 Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL

2023

Infection Prevention and Control - CEP

Airborne transmission

Airborne transmission may occur via particles containing infectious agents that remain infective over time and distance. Small-particle aerosols (often smaller than 5 microns) are created during breathing, talking, coughing or sneezing and secondarily by evaporation of larger droplets in conditions of low humidity. Aerosols containing infectious agents can be dispersed over long distances by air currents (e.g. ventilation or air-conditioning systems) and inhaled by susceptible individuals who have not had any contact with the infectious person.

These small particles can transmit infection into the small airways of the respiratory tract. An example of infectious agents, primarily transmitted via the airborne route, are M. tuberculosis, chickenpox, and measles.

Common vehicles

Vehicles that may indirectly transmit an infectious agent include food, water, biological products (blood), and fomites (inanimate objects such as handkerchiefs, bedding, or surgical scalpels).

A vehicle may passively carry a pathogen:

• Food or water may carry the hepatitis A virus. Alternatively, the vehicle may provide an environment in which the agent grows, multiplies, or produces toxins.

• Improperly canned foods provide an environment that supports the production of botulinum toxin by Clostridium botulinum.

Vector transmission

Vector transmission occurs when an infectious agent is carried from a reservoir to a susceptible host by a living intermediary for example insects such as:

• Mosquitoes – malaria, Ross River, Dengue Fever, chikungunya fever, Zika virus fever, yellow fever, West Nile fever, Japanese encephalitis

• Tick – tick-borne encephalitis

Diseases transmitted by vectors are usually not directly transmitted between humans

Portal of entry

An agent enters a susceptible host through a portal of entry. The portal of entry provides a site for the agent to multiply or for a toxin to act.

Infectious agents can enter the body through:

• Inhalation (e.g. breathing in contaminated particles)

• Ingestion (e.g. eating contaminated food)

• Absorption (e.g. contaminated particles coming into contact with conjunctiva or eyes)

• Break in the skin (e.g. needle stick injury)

• Introduction by medical procedures (e.g. catheters, surgery)

Incubation

The incubation period is the time between the exposure to the pathogen, to the onset of signs or symptoms of the infectious disease. The length of the incubation period depends on:

• The portal of entry

• The rate of growth of the organism in the host

• The dosage of the infectious agent

• The host’s resistance

Some examples of incubation periods:

• Chickenpox: 10-21 days

• COVID-19: 1-14 days

• Tuberculosis: 4-12 weeks

• Salmonella: 6-72 hours

Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023

17

OFFICIAL OFFICIAL

Control - CEP 2023

Infection Prevention and

Colonisation, infection, and disease

Not all infectious agents cause infection or disease, they exist naturally everywhere in the environment.

For example, there is ‘good’ bacteria present in the body’s normal flora

Parasites, prions and several classes of microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, fungi and protozoa, can be involved in either colonisation or infection, depending on the susceptibility of the host.

• With colonisation, there is a sustained presence of replicating infectious agents on or in the body, without caus ing infection or disease.

• With infection, invasion of infectious agents into the body results in an immune response, with or without the symptomatic disease.

Susceptible host

A susceptible host is required for a pathogen to cause an infection. A person lacking effective resistance to a particular pathogen is susceptible to those organisms. This ineffective immune system leaves people vulnerable to infectious agents. Characteristics that influence susceptibility and the severity of the infection include:

• Gender

• Ethnicity

• Socioeconomic status

• Marital status

• Medications (e.g. immunosuppressants taken after an organ transplant)

• Trauma

• Antibodies (active and passive immunity)

• Medical conditions (e.g. comorbid conditions)

• Heredity

• Occupation

• Balance of the body’s normal flora

• Natural barriers (e.g. people with open wounds)

Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs)

Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) are those infections that are acquired as a direct or indirect result of healthcare. Healthcare-associated infections are one of the most common complications affecting patients in the hospital. As well as causing unnecessary pain and suffering for patients and their families, an HAI can prolong a patient’s hospital stay and add considerably to the cost of delivering health care.

An HAI can occur in any healthcare setting: hospitals, office-based practices (e.g. general practice clinics, dental clinics, community health facilities), the setting in which paramedics work and long-term care facilities. This means that any person working in or entering a healthcare facility is at risk of an HAI.

The good news is that HAIs ARE potentially preventable.

It is possible to significantly reduce the number of HAIs by:

• Putting in place appropriate infection prevention and control measures to prevent people from getting an HAI, and

• Undertaking HAI surveillance to identify what can be done to improve clinical practice to reduce the risk of HAI acquisition.

Breaking the chain of infection

Breaking just one link in the chain of infection means that communicable diseases cannot be passed on to another individual. Transmission may be interrupted when:

• The infectious agent is eliminated, inactivated or cannot exit the reservoir.

18 Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL

Infection Prevention and Control - CEP 2023

• The portals of exit are contained through safe infection control practices.

• The transmission between objects or people does not occur due to barriers and safe infection control practices.

• The portals or entry are protected.

Infection Prevention and Control

Infection prevention and control is achieved by following the principles and processes of the SAAS infection control program, which covers the following:

• Standard precautions

• Transmission-based precautions

• Immunisations

• Management of occupational risk and exposure

Standard Precautions

All people potentially harbour infectious agents. Standard precautions refer to those work practices that are applied to everyone, regardless of their perceived or confirmed infectious status and ensures a basic level of infection prevention and control.

Implementing standard precautions as a first-line approach to infection prevention and control in the healthcare environment minimises the risk of transmission of infectious agents from person to person, even in high-risk situations.

If these precautions are not followed, patients are at an increased risk of acquiring an infection.

Standard Precautions include:

• Hand hygiene and care

• Respiratory hygiene and cough etiquette

• Using personal protective equipment (PPE)

• Environmental controls e.g. routine and scheduled cleaning, spills management

• Aseptic technique

• Reprocessing of reusable equipment and instruments

• Safe handling and disposal of sharps

• Appropriate handling of waste and linen

If these precautions are not followed, patients are at an increased risk of acquiring an infection.

Hand Hygiene

Effective hand hygiene is the single most important strategy in preventing healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). Ease of access to hand washing facilities (soap and water) and alcohol-based hand rubs can influence the transmission of HAIs. Washing hands with soap and water is required if hands are visibly soiled while either product can be used if hands are visibly clean.

Microorganisms present on the hands most of the time are known as resident flora. Microorganisms that are picked up on hands during activities involved in providing healthcare are known as transient flora. Transient flora are usually associated with HAIs, they are easily picked up and easily transferred to others. They are often involved in outbreaks of multi-resistant organisms e.g. MRSA, VRE. They are easily removed with hand hygiene.

19 Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL

- CEP 2023

Infection Prevention and Control

As it is possible that you may be washing your hands multiple times in a day it is possible that this can cause dry and chapped skin. An appropriate lotion should be used to replace natural oils.

It is important to also inspect your hands regularly for signs of cuts, infections or dermatitis. Persistent skin problems and suspected latex allergies should be reported to a medical practitioner.

5 Moments Hand Hygiene

The ‘5 moments for hand hygiene’ was developed by the World Health Organization and has been adopted by Hand Hygiene Australia and then taken on by National Hand Hygiene Imitative, it:

• Protects patients against acquiring infectious agents from the hands of the healthcare worker

• Helps to protect patients from infectious agents (including their own) entering their bodies during procedures

• Protects healthcare workers and the healthcare surroundings from acquiring patients’ infectious agents.

Moment 1: BEFORE touching the patient in any way.

On entering the patient zone/house/environment, immediately before touching the patient e.g. before the non invasive examination, assisting to move, applying monitoring equipment.

Moment 2: Immediately BEFORE an invasive high-risk procedure.

Once hand hygiene (HH) has been performed, nothing else in the patient zone should be touched e.g. insertion of a needle into a patient’s skin, preparing and administering medications via invasive devices, any assessment, treatment and patient care where contact is made with non-intact skin.

Moment 3: AFTER a procedure or Body Fluid Exposure.

Even if you have gloves on, you should remove gloves and perform HH after invasive procedures (see Moment 2) e.g. contact with urine bottle, sputum via tissues, contact with blood, saliva, mucous, urine, faeces etc.

Moment 4: AFTER touching the patient.

Perform hand hygiene before moving from patient zone to work from a clean HCW zone e.g. after touching a patient in an ambulance you need to perform hand hygiene to access equipment drawers and cupboards, or to drive the vehicle. When pushing a stretcher into a hospital, as soon as you leave the patient you need to perform hand hygiene before touching anything else.

Moment 5: AFTER touching the patient’s surroundings (home, office, hospital).

Immediately after touching the patient surroundings even if you didn’t touch the patient, e.g. after entering the patient’s house and touching anything in the house.

Hand Washing

Hand washing refers to the appropriate use of non-antimicrobial soap and water on the surface of the hands. Plain soaps act by the mechanical removal of microorganisms and have no antimicrobial activity. They are sufficient for general social contact and for cleansing of visibly soiled hands. They are also used for the mechanical removal of certain organisms such as C. difficile and norovirus. Hands need to be dried thoroughly. This should be accomplished using a good quality paper towel or air hand driers. The use of cloth or fabric towels can also be a source for cross-contamination.

20 Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL

Prevention and Control - CEP 2023

Infection

Other times to perform hand hygiene starting and leaving work, before eating or handling food, after going to the toilet.

How to wash your hands

The following hand washing steps for both soap/water and alcohol hand gels will ensure that your hands are as clean as possible.

Alcohol-based Hand Rub (ABHR)

Research has demonstrated that alcohol-based ABHR is better than traditional soap and water because they:

• Result in a significantly greater reduction in bacterial numbers than soap and water in many clinical situations, (see Figure 3.2 below).

• Require less time than hand washing.

• Are gentler on the skin and cause less skin irritation and dryness than frequent soap and water washes, since all hand rubs contain skin emollients (moisturisers).

• Can be made readily accessible to healthcare workers e.g. emergency vehicles with no access to soap and water.

• Are more cost-effective.

Soap and water wash is required if hands are visibly soiled, and either product can be used if hands are visibly clean. Neutral hand-wipe products may be considered in instances where hygienic access to soap and water is not readily available, such as in community care settings, patient homes.

There is no maximum number of times that ABHR can be used before hands need to be washed with soap and water.

How to apply Alcohol-Based Hand Rub

Apply enough ABHR to your hands to cover all surfaces, 1-2 pumps of a dispenser similar to a 10 - 20 cent piece. Rub hands together covering all surfaces for 20 seconds or until the ABHR has evaporated.

21 Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL

Prevention and Control - CEP 2023

Infection

Surgical hand wash

The process of eliminating transient and reducing resident flora prior to surgery. This comprises removal of hand jewellery, performing hand hygiene with liquid soap if hands are visibly soiled, removing debris from underneath fingernails and scrubbing hands and forearms using a suitable antimicrobial formulation.

At SAAS surgical hand scrubs are performed by Extended Care Paramedics (ECPs) and Retrieval, Rescue and Aviation Services (RRAS), prior to insertion of invasive devices.

Principles of effective hand hygiene

Hand hygiene consists of more than just hand washing, it also includes the following:

• Removing all hand and arm jewellery as they can harbour organisms and spread disease, scratch the client or pierce the gloves.

• Cover all cuts, abrasions and lesions with waterproof tape or spray on dressings which act as a barrier to spreading organisms from the health care worker to the client and vice versa.

• When washing hands, avoid splashing water on your clothing. Keep your hands and uniform away from the surface of the sink and do not lean against the sink.

Procedures – Hand Hygiene [PRO-045]

Respiratory hygiene and cough etiquette

Respiratory hygiene and cough etiquette must be applied as a standard infection control precaution at all times.

Covering sneezes and coughs prevents infected persons from dispersing respiratory secretions into the air. Good respiratory hygiene can help prevent the spread of infections such as colds and influenza.

Covering your sneezes and coughs prevents infectious people from dispersing respiratory droplets into the air.

Key things staff should do:

1. Put a surgical mask on the patient (if tolerated).

2. Cover your mouth and nose with disposable tissues when coughing sneezing, wiping and blowing noses.

3. If no tissues are available cough into your elbow.

4. Dispose of used tissue in the nearest bin.

Healthcare workers with viral respiratory tract infections should remain at home until their symptoms have resolved.

Procedure – Respiratory Hygiene and Cough Etiquette [PRO-250]

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

Personal protective equipment (PPE) refers to a variety of barriers, used alone or in combination, to protect mucous membranes, airways, skin and clothing from contact with infectious agents. PPE may include aprons, gowns, gloves, surgical masks, protective eyewear and face shields or a combination of several of these items.

22 Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL

Prevention and Control - CEP 2023

Infection

The selection of PPE must be based on an assessment of the risk of transmission of infectious agents to the patient or HCW and the risk of contamination of the clothing or skin of healthcare workers or other staff by patients’ blood, body substances, secretions or excretions.

SA Health Policy Guideline - Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Selection

The following roles and responsibilities are specific to PPE, all SAAS workers will take reasonable care to:

• Ensure their own health, safety and well-being in the workplace

• Wear and maintain PPE provided when undertaking exposure-prone procedures

• Attend PPE training including donning and doffing

• Comply with any reasonable instruction, training and safe work procedure when required to use PPE within the workplace

• Use PPE in accordance with policies, procedures and guidelines

• Do not intentionally misuse or damage PPE

• Maintain and clean (where required) PPE in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions and local procedures

• Report all incidents of PPE failure and breaches on the Safety Learning System (SLS)

• Notify line managers if PPE is found to be unsuitable for use e.g. does not fit correctly or you have an adverse reaction using it

• Report any faults, difficulties, damage, defect or need to clean or decontaminate associated with the PPE

Gloves

When used appropriately, gloves can protect both patients and healthcare workers from exposure to potentially infectious microorganisms. They do not need to be worn for most routine patient care of non-infectious patients, and they never replace the need for hand hygiene.

It is recommended that:

• Gloves must be worn as a single-use item for each invasive procedure, contact with non-intact skin, mucous membranes or sterile sites and if the activity has been assessed as being an exposure risk to blood and bodily fluids.

• Gloves must be removed, and hand hygiene performed before leaving a patient’s room or area.

• Single-use disposable gloves must not be reused i.e. washed or alcohol-based hand rub applied for subsequent reuse.

• Single-use disposable gloves must be changed: Between episodes of care for different patients.

Between each episode of clinical care on the same patient to prevent cross-contamination of body sites (e.g. mouth care followed by wound care).

When the integrity of the glove has been compromised e.g. ripped or torn.

• Single-use disposable sterile gloves must be worn during contact with sterile sites:

Procedures requiring aseptic technique where key parts and/or sites are touched directly (e.g. when a non-touch technique cannot be achieved).

• Care should be taken when removing and disposing of gloves to not contaminate the hands after gloves are removed and hand hygiene is performed in accordance with SA Health Hand Hygiene Policy Directive.

• Gloves should be discarded into a designated container for waste to contain the contamination.

Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023

23

OFFICIAL OFFICIAL

- CEP 2023

Infection Prevention and Control

Safe glove removal

Gloves should be removed, and hand hygiene performed:

• Prior to use of any electronic equipment (i.e. computer keyboard) or non-disposable items (e.g. pens, paperwork, folders).

• Prior to entering a hospital or facility. This is to reduce the spread of organisms between the patient’s environment, the ambulance and the receiving hospital. If required, a new set of gloves can be put on once inside the hospital.

Sterile gloves

Sterile gloves should be worn when there is contact with normally sterile sites or clinical devices where sterile or aseptic conditions must be maintained e.g. urinary catheterisation, complex dressings, central venous catheter insertion.

Single-use disposable sterile gloves must be worn during contact with sterile sites:

• Procedures requiring aseptic technique where key parts and/or sites are touched directly (e.g. when a non-touch technique cannot be achieved).

Refer to the Personal Protective Equipment procedure for donning and doffing gloves technique.

Procedure – Personal Protective Equipment [PRO-249]

Aprons and gowns for infection prevention

Protective clothing (aprons or gowns) are recommended to be worn by all workers when:

• There is a risk of exposure to blood, body substances, secretions or excretions (excluding sweat).

• There is anticipated close contact with the patient, materials or equipment which may lead to contamination of the skin, uniforms or clothing with infectious microorganisms.

• To protect the patient from contact with potentially contaminated uniforms or clothing (e.g. immunosuppressed patients).

SAAS provides a variety of Level 3 isolation gowns that provide protection against moderate fluid exposures e.g. arterial blood splatter, trauma and aerosol generating procedures. Long sleeve isolation gowns should:

• Fully cover the torso and neck to knees,

• Fully cover the arms to the end of the wrist and

• Wrap around the back

24 Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL

Control - CEP 2023

Infection Prevention and

Masks

Surgical masks

Single use face masks are not classified as respiratory protective equipment, but do provide a barrier to splashes and droplets impacting the wearer’s nose, mouth and respiratory tract. Wearing a correctly fitted surgical mask for cough etiquette (source control) reduces the number of droplets and aerosolised particles dispersed into the air.

A surgical mask and protective eyewear or face shield must be worn if:

• There is the potential for the generation of splashes or sprays of blood and body substances into the face and eyes.

• The patient is known or suspected to be infected with microorganisms transmitted by respiratory droplets e.g. influenza, meningococcal.

Particulate Filtration Respirator (PFR)

Particulate Filtration Respirator (PFR) e.g. N95, D95 or P2 are used as respiratory protection to prevent inhalation and contact with:

• Infectious pathogens transmissible by the airborne route

• When performing aerosol-generating procedures, or

• For pathogens where the transmission route is uncertain e.g. novel respirator pathogens

Particulate filter respirators (PFR) are designed to be tight-fitting. Staff must be fit tested to a PFR mask before they can start wearing them. If air leaks around the PFR edges the wearer will not achieve the level of protection needed to protect their health.

Facial hair and facial piercings must not interfere with the safe use of a PFR. Workers who have facial hair (including a 1–2 day beard growth/stubble) must be aware that an adequate seal cannot be guaranteed between the respirator and the wearer’s face.

A correctly fitted P2/N95 respirator must be used when:

• Attending to patients with confirmed or suspected serious diseases transmitted by the airborne route (e.g. measles, chickenpox or active pulmonary tuberculosis).

• When performing high-risk aerosol-generating procedures such as CPR, intubation on patients with a confirmed airborne disease or whose infectious status is unknown or unconfirmed.

• Novel respiratory pathogens where the route of transmission is unknown.

Guidelines for mask wearing

When wearing a mask the following should be considered:

• For a surgical masks ensure, the ties are secured and the mask fits comfortably.

• Ensure they are secured over the mouth, nose and chin.

• Perform a fit check if using a PFR.

• Do not touch the outer surface of the mask when removing it, use the straps.

• Once the mask has been removed and disposed of, wash hands thoroughly.

Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023

25

OFFICIAL OFFICIAL

Prevention and Control - CEP 2023

Infection

Eye and face protection (safety glasses and face shields)

Goggles and safety glasses prevent injury to the eyes. Face shields and visors prevent injury to eyes, nose and mouth from hazards including dust, flying particles, chemicals, and potentially infectious blood or body fluids.

Normal prescription glasses DO NOT provide adequate protection. Workers requiring reading glasses should seek additional eye protection which does not interfere with the worker’s vision yet provides an appropriate barrier to hazards.

Workers must wear protective eyewear for any procedure when they may be exposed to hazards or hazardous situations, or where stated in the safe work procedure.

Protective eyewear should be worn when there is the potential for splashing, splattering or spraying of blood and other body fluids. Protective safety glasses should also be worn during cleaning procedures.

Glasses should provide clear vision and be distortion and fog-free. They should be close fitting and shielded at the sides. Safety glasses should be removed by the arms.

Sequence for putting on and removing PPE

To reduce the risk of transmission of infectious agents, PPE must be used appropriately. The following poster outlines sequences and procedures for putting on and removing PPE.

26 Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL Infection Prevention and Control - CEP 2023

Routine and Scheduled Cleaning

Infectious agents can be widely found in pre-hospital setting. Transmission of infectious agents from the environment to patients may occur through direct contact with contaminated equipment, or indirectly, for example, via hands that are in contact with contaminated equipment or the environment and then touch a patient.

Cleaning is a process which intends to remove foreign material (e.g. dust, soil, blood, secretions, excretions and micro-organisms) from a surface or an object using water, detergent and mechanical action/ friction. Although cleaning is known to successfully reduce the microbial load on surfaces there are some circumstances where disinfection is also required to be performed.

Disinfection is a process that eliminates many or all micro-organisms except bacterial spores. Disinfection is necessary when body fluids are spilled, when a multi-resistant organisms (MRO) is present or there is an outbreak of an infection. Cleaning of ambulance interiors, ambulance equipment, office environments or stations should be done routinely and anytime they become soiled with dirt or debris. It is an essential part of the standard precautions in infection control.

Therefore keeping the ambulance clean is an important part of infection prevention and should be done in accordance with the Routine Cleaning and the Scheduled Cleaning procedures.

Procedure – Scheduled Cleaning [PRO-252]

Procedure – Routine cleaning [PRO-118]

Ambulance interior and equipment

High-touch areas in ambulances and shared patient equipment are considered high risk and should have a high frequency of clean. This is the responsibility of operational staff after each patient, refer to the Routine Cleaning Procedure.

Low-touch surfaces such as floor, walls, steering wheel, locker doors, etc., in ambulances and light fleet, are considered a moderate risk and should have a frequent scheduled clean. This is the responsibility of operational staff using the vehicles and should occur once per shift whenever operationally possible.

Spot cleaning of surfaces that are visibly soiled should be completed as required by staff using the vehicles.

Fleet Cleaning and Stock Expiry Register

27 Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL

Prevention

Control - CEP 2023

Infection

and

Level 1 clean – standard precaution (after every patient)

Cleaning of all high touch surfaces, all equipment which has had a direct or indirect patient or clinician contact or any surface/item that is visibly soiled must occur after each patient attended.

High touch surfaces and equipment includes ambulance grab rails, handles, drawers, stretcher mattress, belts, handles and rails, response kits, ECG monitor, ECG leads, pulse oximetry probe, BP cuff.

Use appropriate standard precaution PPE as required:

• Detergent and water are adequate for a level 1 routine clean:

Use buckets and mops designated for ambulance cleaning.

With clean disposable cloths, mop and the detergent solution (diluted to the manufacturer’s instructions, wipe/ mop over surfaces and equipment:

○ Empty buckets after use, rinse with a fresh detergent solution and store upside down to allow for draining and drying.

○ Dispose of cloths after use.

○

Rinse mop after use and store upside down to allow for draining and drying. Mop heads should be replaced regularly and when visibly soiled.

• Where this is not practical, all-in-one detergent/disinfectant wipes (e.g. Clinell® wipes) are a suitable alternative:

Use more than one wipe for larger surface areas; sufficient to ensure the whole surface is wet (e.g. 4 to 6 wipes may be required to clean a stretcher).

Allow the surfaces to air dry.

• Alcohol based wipes (e.g. Isowipes®) can be used for cleaning electronic equipment and screens.

Disinfectant wipes (e.g. Clinell®) and alcohol wipes (e.g. Isowipes®) should be available at all ambulance stations and in all ambulances.

Use detergent and water with disposable cloths and bucket and/or mop and bucket (as described in section 3.1 of the Routine Cleaning Procedure) for grossly soiled surfaces that are too large to be managed with detergent/disinfectant wipes, such as the ambulance floor.

For re-usable ambulance items that are grossly soiled or require specialised cleaning, refer to the following procedure.

Procedure – Reprocessing of Used or Soiled Ambulance Equipment [PRO-112]

28 Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL Infection Prevention and Control - CEP 2023

Level 2 decontamination – after a patient with transmission-based precautions (contact or droplet)

In addition to a level 1 clean, all surfaces and equipment that have been in contact with a patient requiring transmission-based precautions or indirectly via the clinician must be cleaned with a disinfectant.

A disinfectant is a chemical agent that rapidly kills or inactivates most infectious agents. Disinfectants are not to be used as general cleaning agents, unless combined with a detergent, as a combination cleaning agent (detergent disinfectant).

Where a 2 in 1 detergent and disinfectant has been used, (e.g. Actichlor Plus or Clinell wipes in the level 1 clean), there is no need to repeat, as the decontamination step has already been completed. Use appropriate transmission based precaution PPE as required.

Procedure - COVID-19 Clean using Actichlor Plus Actichlor Plus solution must be prepared with a ratio of 1 tablet to 1 litre of cool water to ensure 1000ppm concentration.

Product Type of Product Dilution Concentration

Actichlor Plus Neutral Detergent AND TGA approved disinfectant

1 tablet (1.7g) dissolved 1 litre water cool/cold water 1000 ppm

Ensure any exposed linen not stored in the overhead locker is disposed of in a linen skip.

Remove any rubbish and empty rubbish bins.

Clean all vehicle surfaces and equipment with the following:

• USE Clinell wipes for equipment (ECG cable, BP cuffs, stethoscopes, etc.)

• USE Actichlor Plus on all other surfaces and larger equipment (stretcher, walls, floor, ceiling and driver/ passenger foot well etc.)

• USE 70% Isopropyl Alcohol wipes for sensitive medical equipment (ECG electrode, MDT/Monitor screens).

Allow all surfaces to dry or, dry electronic equipment with a clean dry cloth, if required.

Empty bucket(s) after use, rinse with clean water or solution and store upside down to allow draining and drying. Dispose of cloth(s) and/or mop head after use.

Spills of Actichlor Plus or bleach

Contain any bleach solution spills with disposable cloths. If unprotected skin or eyes become contaminated, wash with copious amounts of water and seek assistance.

For reusable ambulance items that are grossly soiled or require specialised cleaning, refer to the following procedure.

Procedure – Reprocessing of Used or Soiled Ambulance Equipment [PRO-112]

Level 3 air – after a patient with transmission-based precautions (airborne)

In addition to a level 1 and level 2 clean, air the ambulance and equipment by leaving all doors open and equipment exposed to air for 10 minutes.

Scheduled cleaning of ambulance vehicles

Scheduled three monthly cleaning of metropolitan ambulances (stretcher carrying vehicles) and stretchers is managed by SAAS Fleet Services. Scheduled cleaning of country ambulances will occur as per local arrangements.

Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023

29

OFFICIAL OFFICIAL

CEP 2023

Infection Prevention and Control -

Ambulance Stations

Ambulance station sluice rooms or equipment reprocessing areas are considered moderate risk and should have a frequent clean. All other areas of ambulance stations are considered low risk and should have a regular scheduled clean.

Routine cleaning

Staff on shift/on station are responsible for:

• Maintaining all station areas free from clutter to not inhibit any external providers from performing contracted cleaning.

• Ensure refrigerators, freezers, kitchens, storage rooms, and personal areas such as lockers, drawers, and cupboards are maintained in a manner that does not put the health and safety of others at risk.

• Wiping benches, storage containers and spaces in clinical areas (clinical storerooms and sluice rooms) and mop floors with detergent and water.

Scheduled cleaning

Scheduled cleaning of ambulance stations is managed by SAAS Building Services, who will inform the relevant workgroup or worksite regional Operations Manager when and what type of cleaning is scheduled.

• Managers should ensure any staff who have known allergies or reactions to scheduled cleaning are accommodated at an alternative worksite for an appropriate pre-determined exclusion period.

Spot cleaning of surfaces that are visibly soiled should be completed as required by staff using the area.

All staff will be required to ensure the station area is tidy and free from obstruction in time to allow access for any scheduled cleaning to occur.

It is the responsibility of staff to ensure any outside facilities e.g. sheds or alfresco common areas are maintained in a manner that does not present a risk of health or safety to others.

Office Environments

SAAS office/administration areas are considered low risk as there is minimal patient contact or indirect patient contact. There is still a risk that infectious agents causing common illnesses can spread easily in a workplace if routine cleaning is not done.

Routine cleaning

Staff are responsible for:

• Regular hand hygiene, particularly after a break away from their workstation.

• Cleaning their workstations, particular attention needs to be paid to ‘hot desks’, which should be cleaned prior to and after each use using all-in-one detergent/disinfectant wipes.

• Cleaning of electronic equipment, with particular attention to telephones and computer keyboards and mice using alcohol wipes at the start of every day/shift.

• Maintaining the office area free from clutter so as to not inhibit any external providers from performing contractual cleaning.

• Ensuring refrigerators, freezers, kitchen, storage rooms, and personal areas such as lockers, drawers and cupboards are maintained in a manner that does not put the health and safety of others at risk.

Scheduled cleaning

Scheduled cleaning of office environments is managed by SAAS Building Services, who will inform the relevant workgroup when and what type of cleaning is scheduled.

Managing a blood or body fluid spill

For all body fluid spills the following process must be followed:

• Don appropriate PPE including eye protection and gowns.

• Contain the fluid using hand towels or blankets.

30 Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL Infection Prevention and Control - CEP 2023

• As soon as practicable soak up as much of the fluid as possible using absorbent disposable material and dispose of in a medical waste bin.

• Clean the area with detergent and warm water.

• Remove all visible signs of the spill. This may require more than one attempt, changing the water and cleaning material often.

• Wipe a large spill with bleach after cleaning and drying using 25ml of bleach per 1 Litre of water or Actichlor Plus.

Cleaning equipment

Most cleaning procedures require the use of some equipment including spray bottles, cloths, sponges, mops and buckets.

The following guidelines should be followed when using cleaning equipment:

• Cleaning cloths should be disposable.

• Mops and buckets must be cleaned with detergent and warm water after use and then stored upside down to dry.

• Refillable spray bottles must be cleaned and dried thoroughly before re-use. Bleach solutions should NOT be put in spray bottles.

Cleaning equipment should always be stored in a manner that ensures a safe work environment and should be put away in a way that minimises the risk of injury.

Re-processing of equipment

All ambulance equipment can be sorted into three categories relating to the level of risk it poses. The categories are:

• Critical items which enter or penetrate into tissue, a body cavity or the bloodstream.

• Semi-critical items which have contact with intact mucous membranes or non-intact skin.

• Non-critical items are those which have contact with intact skin only.

In SAAS, all critical and semi-critical items, are single patient use only. They are marked with the following symbol or the words ‘single-use only’ printed on them. These must be disposed of in an appropriate receptacle after single use or single patient use. The reuse of single-use items is not approved by SAAS and is regulated by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA).

The level of reprocessing required for non-critical items depends on the item, its intended use, manufacturer’s instructions and SAAS procedures. After use on a patient, any reusable medical equipment must not be used for the care of another patient until it has been cleaned and reprocessed appropriately.

Cleaning reusable items is the first step and should occur as soon as practicable. This should be done in accordance with the ‘Level 1 Clean’ as detailed in the Routine Cleaning Procedure.

If the equipment has been exposed to a known or suspected multi-resistant organism (MRO) or other infectious agents requiring contact, droplet or airborne transmission based precautions, the cleaning step should be followed by a disinfection step. This should be completed in accordance with the ‘Level 2 Decontamination’ steps in the Routine Cleaning Procedure.

Items that have been heavily soiled may require specialised cleaning (e.g. Posey Restraint Net). This should be done in accordance with the Reprocessing of Used or Soiled Ambulance Equipment Procedure.Uniforms, stretchers and ambulance interiors which are grossly soiled should be managed according to the Reprocessing of Used Soiled Ambulance Equipment Procedure.

Procedure – Reprocessing of Used or Soiled Ambulance Equipment [PRO-112]

Procedure – Soiled and/or Broken Ambulance Stretchers [PRO-258]

Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023

31

OFFICIAL OFFICIAL

Control - CEP 2023

Infection Prevention and

Safe handling and disposal of sharps waste and linen

The safe handling of sharps, waste and linen is essential to protect you, your work colleagues and patients. This procedure outlines safe work practices for the handling and disposal of sharps, waste and linen.

Safe handling and disposal of sharps

It is important that all staff are aware of the inherent risk of injury associated with the use of sharps such as needles, scalpels and lancets. When handling sharps the following principles apply:

• The person using the sharp is responsible for its safe disposal

• Dispose of the sharp immediately following its use and at the point of care

• Dispose of all sharps in designated puncture resistant containers that conform to relevant Australian Standards (AS/NZS 4261:1994 reusable; AS 4031:1992 non-reusable)

• Dispose of sharps disposal containers when they are ¾ full or reach the specified fill line, seal appropriately and place in the clinical waste stream

• Never pass sharps by hand between health care workers

• Never recap used needles unless an approved recapping device is used

• Never bend, break or otherwise manipulate by hand a needle from a syringe

Linen management

The correct handling of linen is vital, it can be contaminated with blood and any other body fluids as well as through improper handling and storage.

Clean linen does not need to be sterile (free from all microbes), but correct handling will prevent the growth of micro organisms that can develop under poor conditions.

Clean linen

Clean linen must be stored in a clean dry place that prevents contamination by aerosols, dust, moisture and vermin. It should be transported and stored separately from soiled lined. Clean linen should only be handled by staff who have used proper hand hygiene procedures.

Clean linen in Ambulances should be re-stocked with supplies at metropolitan public emergency departments and most ambulance stations, or as per local arrangements.

Soiled linen

All used linen should be handled with care to avoid dispersal of microorganisms into the environment and to avoid contact with staff clothing. The following principles apply for linen used by all patients regardless of their infectious status:

• All used linen is considered contaminated therefore minimal handling is recommended

• Appropriate PPE must be worn during the handling of soiled linen to prevent skin and mucous membrane exposure to blood and body fluids

• Dispose of all linen into an appropriate linen container at the point of care

• Linen which is heavily contaminated with blood and/or other body fluids which could leak must be contained by a leak-proof bag and secured prior to transport

• Hand hygiene must be performed following the handling of all used linen.

• Placed in linen bags which are no more then three-quarters full. Once a linen bag is three-quarters full the top should be tied.

• Collected by a contractor or taken to a contractor and laundered as per SA Health standards.

Hand hygiene must be performed following the handling of any used linen.

Linen is not to be rinsed or sorted by SAAS staff once used and must NOT to be washed in a domestic washing machine.

32 Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL

Prevention and Control - CEP 2023

Infection

Safe Handling and Disposal of Waste

General Waste

• General waste is waste which is not recycled or reused and does not pose a threat or risk to public health or safety and meets landfill acceptance criteria. This may include PPE or other items that have been risk assessed as not visibly contaminated by gross amounts of blood and/or body fluids. Materials that are only stained can be disposed of in general waste.

• When the bin is three quarters full, it should be “tied-off” to prevent spillage of the contents for collection and disposal. This waste should NOT go into the recycling bin.

• Hand hygiene must be performed after handling or transporting waste bags or bins (regardless of glove use).

• If in doubt when assessing the level of contamination and/or the required waste stream, default to the medical (clinical) waste streams.

Medical (Clinical) Waste

• Medical waste is defined as waste consisting of all sharps, human tissue including bone, any liquid body fluid, and laboratory specimens. This may include personal protective equipment (PPE) that is grossly visibly contaminated with blood and/or body fluids.

• Medical (clinical) waste is categorised by the colour yellow in South Australia and is incinerated and cannot be disposed of into the general waste or recycling waste streams.

• Yellow biohazard bags should be tied off at the point of use and disposed of into an approved clinical waste bin e.g. yellow 2-wheeled mobile garbage bin (MGB) with a lockable lid.

• Sharps must be disposed of into a sharps container, preferably at the point of care or point of use. Sharps containers must not be overfilled and must be sealed when three quarters full (or at designated fill line). Sharps containers are then to be placed into an approved medical (clinical) waste bin.

• Any waste receptacle, bin or MGB must not be overfilled. When sharps containers and/or medical (clinical) waste bins are ¾ full, the lid should be secured/locked while awaiting collection from the secure location. Waste bags within medical (clinical) bins should not be pushed down or moved to create more room in the receptacle as this may increase risk of aerosol contamination exposure to blood and/or body fluids.

Sharps must be disposed of into a sharps container, preferably at the point of care or point of use. Sharps containers must not be overfilled and must be sealed when three quarters full (or at designated fill line). Sharps containers are then to be placed into an approved medical (clinical) waste bin.

The following materials are not usually regarded as medical waste unless they fall into the medical waste definition:

• Dressings and bandages.

• Materials stained with or having had contact with body substances.

• Containers no longer containing body substances.

• Disposable nappies and incontinence pads.

• Sanitary napkins.

Clinical waste bins are collected by operators licensed by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to transport clinical waste and are then incinerated.

There are other types of waste not regularly used with in SAAS. Clients may receive treatment at home and the appropriate waste receptacles organized or provided by the health provider.

33

OFFICIAL OFFICIAL Infection Prevention and Control - CEP 2023

Continuing Education Program 2023 - Jan 2023

Cytotoxic waste

This waste includes any residual cytotoxic drug following a patient’s treatment and the materials or equipment associated with the preparation, transport or administration of the drugs. Cytotoxic waste is hazardous to human health and the environment and is subject to the requirements of the South Australian Environmental Protection Act 1993.

All cytotoxic waste should be placed into compliant bags or containers that are appropriately labelled and identified including:

• Containers and bags must be purple/lilac.

• The container must be marked with the ‘cell in late telophase’ symbol in white

• The words CYTOTOXIC WASTE’ must be clearly displayed.

Transmission-Based Precautions

Standard precautions must be applied when caring for any patient regardless of their infectious disease status.

Transmission-based precautions are applied to patients suspected or confirmed to be infected with agents transmitted by the contact, droplet or airborne routes.

Transmission-based precautions are applied in addition to standard precautions and include the following.

Contact precautions

• Transmission occurs by either direct or indirect contact

• Direct: involves close contact with a colonised/infected patient with transfer of the organism to the susceptible host, usually during patient care activities e.g. turning a patient.

• Indirect: occurs if an infectious agent is transferred via a contaminated intermediate object (fomite) or person e.g. when contaminated patient-care devices are shared between patients without cleaning and/or disinfection between patients.

Droplet precautions