C omplex Structures :

Indelible Stories of Coming Home

Home is a place that is familiar, loving, and full of vulnerability. There are traumas, and there are celebrations. Sometimes, home is a structure, providing shelter from the world and all it has to offer. Sometimes it is people, a chosen or given family, that makes one feel safe and comforted. Most of all, home is complex.

One can have a house without a home and a home without a house. Systemic economic inequities influence the ability to have a home, especially with the continuing destruction and intentional division that tears apart families, communities, and a collective sense of safety. For people living in Cleveland, communities and neighborhoods have shifted over the years, sometimes moving toward demoralizing conditions, where gun violence and drugs take away loved ones and change what peoples relationship to home. Yet, each person with a home base can feel the benefits of revolutionary rejuvenation and be guided with purpose.

Each person interviewed in this book– Gwendolyn Garth, Joseph Greene, Yvonne Pointer, Dennis Cash, Ronald Freeman, Loh, Robin Lamont, Nehemiah Spencer, Ramona Prescott, André Dailéy, and Chanda Ford – is inspired to continue waking up every day and attempting to make their community better. Whether that is through advocacy and organizing efforts for human rights, creating arts ecosystems and launching careers based on passion, or ensuring elderly people on their street are taken care of, neighbors prove that love and care is what makes a community strong.

These 11 stories represent a small cross-section of Cleveland. Each person is a neighbor of the Cleveland Foundation building. They live in the houses and apartments of adjacent neighborhoods and share the roads for their daily routes to those coming to the new Cleveland Foundation headquarters.

Together we reflect, “what does it mean to come home?”

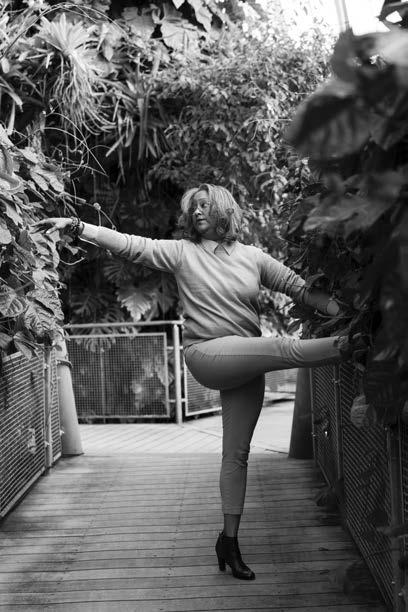

Gwendolyn Garth is a multimedia artist, creative arts therapy specialist, and community activist. She is the Founding Owner of Kings & Queens of Art, a grassroots collaborative of formerly and presently incarcerated artists.

Her current projects include Confronting Darkness and Defying Stereotypes, a mobile exhibition space and classroom utilized by Kings & Queens of Art and other marginalized artists in Cleveland.

Shelli:

Gwen:

Shelli:

Gwen:

What does it mean to come home?

Once we learn what home is, and we can identify or put a word to it, then we can get that feeling. I’m at home with you right now. Home is where you’re familiar, where you can be everything and nothing at the same time. Home isn’t necessarily a structure for me, it’s a state of being.

In my travels, whether I go east or west, every time I come back and I see the Terminal Tower and the skyline, I’m home. One writer said that when you go to describe something with words, you kind of lose the feeling. And I tend to agree, because I now know what unspeakable joy is. And I know why they call it unspeakable joy. Because you just gotta be there. And I think that the more I settle into myself, the more I find myself at home anywhere I go.

Have you always lived in Cleveland?

I was born and raised in Cleveland. I did live in Detroit for a year. I stayed in Columbus for a year, I was in AmeriCorps. And every summer we went to Chicago, so I consider Chicago my second home, because that’s a city where I learned how to move around. You can walk around the city to go from one cousin’s house to another and you can get to know a place. You can identify with the people there.

My mother passed when I was 35. And when I looked at her in her casket I had this feeling…like, you grown now, bitch. It can be lonely and stuff at times because I’m the only of my immediate family that’s alive and I have often wondered, why did God save me? My mother, father, and both of my sisters, their deaths were all alcohol-related. My father had hardening of the arteries, my mother died with a drink in her hand, my sister had the same thing that Muhammad Ali had, but it came from her drinking, and my baby sister, she was drinking and fighting and fell off a porch.

But I had made myself a promise that I wasn’t going to die like my mother did with a drink in her hand. So if I die today or tomorrow, I ain’t gonna be drunk. I’m 24 years sober now. That does leave an empty space when we’re talking about home. But God has put other people like yourself and my other spiritual children and friends in that place to give me a sense of family and to maintain Cleveland being my home, not making me feel all alone.

Even with its ups and downs, it’s my home. I really can’t tell you exactly why. Columbus to me was like a big suburb. It was pretty nice, but I kind of missed the hustle and bustle of the city. Cleveland has a quietness and it has a grittiness, but there is always room for change.

The monument piece I did for the Cleveland Museum of Art is called the Isms Eradicator. Two artists were selected for the Keithley Symposium to come up with a monument that we would like to see in Cleveland. So I think the thing we need in Cleveland is some healing. And from my own discovery and recovery process from substance abuse, I’ve learned that the healing comes from within.

Shelli:

Gwen:

The butterfly is my talisman. I often go inside the chrysalis and do some self examination. That space between here and there when you stop for a minute and reassess and really look, where am I at?

Then and only then can you emerge and become a different creature.

A lot of people don’t know that in the chrysalis, the larva is doing a whole lot of stuff--even eating itself from the inside out. He becomes liquid. And I think that’s what we have to do so God can reform us. We have to become liquid or pliable like clay. The butterfly is one of the few species that do a complete metamorphosis, where you go from one extreme figure to something else.

Maya Angelou said that we delight in the beauty of the butterfly, but we do not look at the changes it went through to get to that beauty.

I think Cleveland needs a metamorphosis. A total metamorphosis. If you look at any and every movement, like Apartheid, Harriet Tubman, the Civil Rights movement, there had to be a catalyst to move it. There had to be something monumental. And that’s what we need across the country.

There was a lecture at CMA, and the speaker was an artist named Dread Scott. And one of the questions he asked was, “What would the world look like without America?” If you think about a lot of our ideas and archaic thinking, it’s based on the thoughts of those who supposedly ‘built’ America. Then when we colonized other places, we brought them the same old ideas.

My granddaughter was in the hospital having a transfusion and I came to pick her up that next day. While we were waiting to get her release papers, I’m watching the History Channel and they were playing The Men Who Built America. And it was amazing to me how America can change so quickly. Like you take the assembly line–that one thing turned the whole country around. It’s almost like when autumn comes, you can’t tell what day or what time those leaves start changing. Next thing you know it’s there, it’s autumn. This country was one way for a minute. And every 5, 10, 15 years, it’s something else and going in an entirely different direction.

So when is the healing going to start? Edgar Villanueva, who wrote Decolonizing Wealth, has seven ways of decolonizing wealth. And the first one is healing. First we got to recognize and admit where we are. And then go from there. Everybody knows what the problem is, but nobody’s owning up.

I would love for you to talk more about your journey with healing.

I was incarcerated. And through my healing, I came to understand that I was incarcerated mentally and spiritually long before I got to the physical place of incarceration.

I often tell people that the only thing I liked about being incarcerated was that it afforded me the opportunity to get with me. I didn’t have to worry about food, clothing, or shelter, because that was all provided, so I could take

the time to get with me. So often, we have not been taught how to fully look at ourselves. Alcoholics Anonymous talks about finding the god of your understanding, and that’s exactly what I did.

My mother died when I was 35. So I started smoking the crack that week, when I was planning her funeral. The guy I thought I was in love with said, “Here, try this. It will help you ease the pain,” not knowing it would cause a hell of a lot of pain. I didn’t know who I was.

So while I’m incarcerated, an older lady had told me, “Do the time, don’t let the time do you.” Because prison is not for the faint of heart. It’s a small community and you can be consumed in that community, or you can find yourself. But this was my second time around and I chose not to come back. So I had to consider that if I don’t want to come back, what do I gotta do? I gotta change something.

I broke down the Serenity Prayer.

One: God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change. What things can’t I change? My past and other people.

Two: Give me the courage to change the things I can. What do I have the power to change? Me and my thinking.

Three: God grant me the wisdom to know the difference. So I have to remind myself that I can change nobody, only me.

It was a hell of a place. I did a lot of writing, and my art helped me find myself. I’m thankful that God made me an artist, because my art was healing.

In prison, you gotta be your own person or else you will get walked on and messed with. So I carried myself in such a way that I learned how to confront confrontation. I realized that I can’t get high and get to arguing and stuff like that, that’s not my level. And I can’t not say something, because that’ll make me sick. I learned a lot about Gwendolyn Garth. When we start to find ourselves it’s a slow and tedious journey–I’m almost 25 years sober and I’m still finding little bits and pieces, still throwing away the fears, still pulling off the mask.

I remember when I was getting high in active addiction, I wouldn’t even glance in the mirror. But now I look in the mirror and say, “Hey girlfriend, what’s happening?” I sleep good not having to worry about consequences. And I’ve learned how to shut that voice in my head saying, “You shouldn’t have did that.” So to keep her quiet, I don’t do it.

And then there’s that voice that goes, “You can’t do that.” And I’ve learned to shut her down too. How do I know I can’t do it if I never tried it? In my house I got all of these little affirmations that help feed my self-talk. They are my medicine. Because negativity will come from the middle of nowhere.

Shelli:

Gwen:

I would love for you to talk a little bit more about when you first came home.

I came home in May of 2000. In January, while I was incarcerated, I practiced being the person I wanted to be. And so I was given that space. I was in a business class and I was allowed to sell my work to inmates and employees. When the employees were having an activity, one of the ladies asked who was the best artist on the grounds and my name came up. So I was getting ushered to the front of the food line, and back in the office they were feeding me strawberries, fresh fruit and stuff that we weren’t privy to. I had sort of a special elite kind of thing going on.

Come that January of 2000, I was scared. I was afraid of my addiction. Because this has happened before. I did work on myself this time, but I was scared as hell. So I’m very spiritual, I have tapped into my spirituality. I have learned, for me, that alcoholism and some of the other -isms are spiritual diseases. I believe that once we start treating other people right, that would even straighten out our environment, because we’re all one.

The universe sent in a lady named Sue Anderson, who was the head of a program at Tri-C called Women in Transition. And she held my hand, literally from the inside to the outside. To me, it was paradoxical that the Northeast Pre-Release Center is catty-corner to Tri-C. You got School of Hard Knocks and you got community college. That’s why I made my transition over there, even though I was projecting how people are going to receive me.

I’m an ex-felon now. I’m a recovering alcoholic and addict. And these are things that society frowns on. Plus, women have it worse. So all of these things I had to overcome.

I think my determination gave me courage. My determination not to come back, except to help others. At Women in Transition, that’s where I met a group of people who didn’t give a damn about where I had been. Then I met Yvonne Pointer, she was a motivational speaker for Women in Transition, and me and her were real fast friends. In the rooms of recovery, they tell you that you must change people, places, and things. Going to the college was the greatest change of people, places and things for me. When people come home and they have to go back to the same environment, especially if they have not really changed or fortified themselves spiritually, it’s easy to fall back into the same rut.

In prison, I started to have a lot of aha moments. Having known the story of Harriet Tubman, it just came to me at that point. Harriet Tubman said, ‘fuck this slavery shit, I’m out.’ And she literally walked up out of her condition. Not off the farm, but her whole condition. I’m never gonna be no slave. That has been my attitude. I’m working on not being a victim of racism. Toni Morrison says something to the nature of, ‘racism ain’t my problem, I didn’t make it.’ As long as everybody on each side of the equation is hung up on it, we can’t see it. It’s like you can’t see the trees from the forest. We can’t grasp the entirety of it.

The universe surrounded me with people to help me be strong and support-

Shelli:

Gwen:

ive. I had them to go to and sit next to because they don’t care where I came from and all they want from me is to be a better Gwen. When I got hooked up with Neighborhood Connections, that was a miracle thing. And I see these small groups of people doing big things.

So I started my organization. And I wanted to keep it small, but I wanted to do big things. I started off with $1 a month, and now I’m paying $1,000 a month. This is a miraculous thing, and it has grown. By giving to my community, the universe gives back tenfold. I truly believe in the universal bank. That once you put it in there, you’re gonna get it back.

• •

What’s your definition of a good neighbor?

One that helps, not because they expected something. To be in a space and always try to make it better. I got this thing about littering and I was waiting on the bus that was on 55th in front of Rally’s. And this guy was eating and just left all his papers in the bus stop when the trash was right there. So I’m waiting and I’m having this debate with myself. Myself said to myself, “Well Gwen, if that litter is bothering you, pick it up.” So I picked it up. I think that’s what a good neighbor is. You won’t stand in a space and not help nobody. Even if you see somebody who needs to laugh. Because what does it cost to smile? It’s good for you too.

When COVID hit and they were telling us not to hug, girl, that worried me. Because hugging increases endorphins. Hugging is good, and the separation and isolation, that was bad. But that time period shows how creative we can get and how we can help people in the spur of the moment in a crisis. Why can’t we do it all the time? Every day should be treated like a crisis. If your house is burning, and I’m next door, and I don’t help you put it out, guess whose house is gonna be next when that strong wind comes along? That’s a good neighbor. We’re gonna do this together.

• •

Shelli:

Gwen:

Where did you grow up? You live in Central now?

I live in Central now. But I grew up in four neighborhoods in Cleveland. When I was born, my family lived in Hough. And then we moved to Central because the first elementary school I went to was on 55th–they changed the name of the school because it used to be George Washington Carver. But thanks to Kevin Conwell, they changed all the names of slave masters. So then we went to Fairfax, off of 105 near Quincy, where I went to Observation, which is now Cleveland School of the Arts. Then I graduated from Glenville. Now I’m back in Central. So I grew up in four neighborhoods. When people ask me about what neighborhood I’m from, I say Cleveland. The East side of Cleveland.

• •

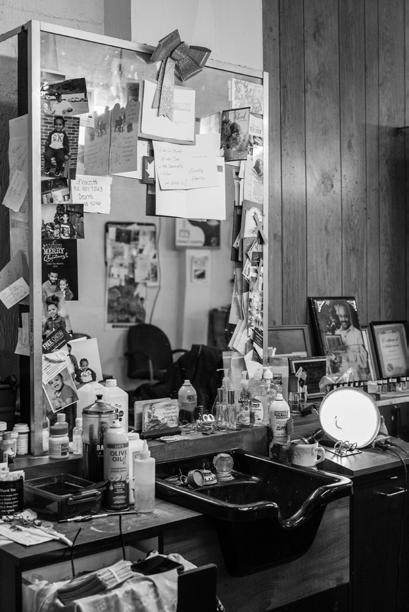

Joseph Greene is a community activist and owner of

All the King’s Men, a barbershop on St. Clair serving the Glenville community for 20+ years. Each year, Greene runs a collection drive to distribute school supplies, Christmas presents, and Thanksgiving turkeys to children and families in the area during the holidays.

Shelli:

Joseph:

Shelli:

Joseph:

Shelli:

Joseph:

Have you lived in Cleveland your entire life?

Yes.

Where did you grow up?

On Vashti, down on St. Clair in Glenville. My mother moved up here from Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

What was your experience growing up in Glenville?

At that time, it was very beautiful. We moved here in ‘63. The riots came, and that was the first time I’ve ever seen the National Guard, jeeps, all that stuff marching down St. Clair. The cable cars, all that was exciting to me back then. With all of the business that was open, things were robust. Hustle and bustle.

Shelli:

Joseph:

Shelli:

Joseph:

How would you describe what Glenville looked like?

Up and coming.

All the businesses were open from the record shops to the factories. White Motor was right here. My brother worked down at Fisher Body. My other brother worked at Alcoa (Aluminum Company of America). The car lots was right there. Freeman Beer was right there where the beauty supply is. It was just wide open. The neighborhood was beautiful. The neighbors were beautiful. It was just a beautiful place. Glenville was up and coming.

And how would you describe your childhood home? Are there any smells that make you think of it?

My mother’s cooking from Louisiana. Red beans and rice, pinto beans, etouffee, jambalaya, gumbo. To kill for was the turkey wings and dressing. Or her macaroni and cheese. And a lot of desserts. My mother made pralines and turtles for Christmas. In the backyard we had two apple trees, two pear trees, a peach tree, a cherry tree and a blackberry bush. Right there when you came down Vashti, that’s where I grew up.

Shelli:

Joseph:

Shelli:

What are some of the highlights and lowlights in your life growing up?

Being a child, going bowling, playing sports, school, barber school… and then the addiction kicked in. Moved into the projects. The whole 80’s were the darkest years for me. Moved into Morris Black. So the good was growing up, going to barber school, getting my barber license, getting my apartment, down into a drug addiction, going to prison, being homeless. All that stuff. I’ve actually been sober for 32 years. So this is 32 years of me, right here, turning my life around, making the mistakes, making corrections.

And I know you had mentioned that you helped with a reentry program at the City Mission and that you’re very involved in the community. What are some of the other things that you’re doing?

Joseph:

Shelli:

Joseph:

Shelli:

Joseph:

Right now I’m trying to collect some money for some bookbags and school supplies for the kids. Bicycles for kids that have straight A’s, turkeys and hams for Thanksgiving, and Christmas toys for kids that normally wouldn’t have a toy at all. I try to do that every year. I try to save all my tip money to do that. A lot of people around here tell me that I’m the only business they know that gives back every year, doing what I do.

How long have you been here (in Glenville)?

22 years.

Can you describe what it was like when you first came here and it became your home?

All the businesses were open. All the buildings were up. People were up and down the street. Now everything’s closed from 88th all the way down. There are only two Black-owned businesses on this side. From 88th all the way to 105th, it’s only me and the ladies at the beauty shop right there. There used to be a Black-owned construction company, but he retired and sold it to the church. So I’ve seen the neighborhood up and I’ve seen it at its lowest.

Shelli:

Joseph:

Shelli:

Joseph:

What do you think changed?

They took all the funding out of the housing, the grocery stores… I almost can’t describe it. It’s just what happens to the inner city. To the jobs. White Motor used to be right there, where the school buses are at. Just like Fisher Body, it used to be just like Chevy, just like Ford. The manufacturing company right there by Shaw used to do airplane parts right off 129th and St. Clair. All those big buildings used to make parts for airplanes.

When the jobs left, the neighborhood went down. And it’s all the way down now. Now, you see development on the West Side. As soon as you go over the bridge to West 25th and Detroit, soon as you go over the Carnegie Bridge, all of that is under development. But the East Side is not. I could take you on a ride from Lakeshore, to St. Clair, to Superior, to Wade Park, to Chester, to Euclid, to Carnegie, to Cedar, to Quincy, to Buckeye, to Kinsman, all the way across to Union, and you don’t see no development. The only development I’ve seen is that 490 project. When I drive through the East Side, no development until you get across Chagrin. I don’t see nothing. No development on the East Side.

• •

What are three words that you would use to describe your home?

Safe, comfortable, and…. I don’t know. It’s hard in here. In any part of the inner city. I know when I go upstairs, I’m safe. I’m at home. I try not to interact because I don’t smoke or drink. So I can’t mingle. Everybody is not doing what I’m doing, but like I said, I’m only 32 years old. So I don’t indulge in what they do. So it’s a blessing that I stay upstairs.

Shelli:

Joseph:

Shelli:

Joseph:

What are some of the things that you do to relax?

Go to Edgewater. Take a ride out on the 22, Pinecrest, Amish Country, Westlake. Take myself to dinner.

And I assume that there aren’t many places to really go because so many things have closed and changed.

Back in the day there were so many Black establishments that you could go to in the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s but all of them shut down. The only well known Black restaurant in Cleveland is Zanzibar in Shaker Square. They should be all over the city, but all the Black businesses are gone. From mom and pop stores to restaurants, cleaners, hardware stores, bicycle stores, record shops. All that’s gone. Right now you have right here a beauty shop, barber shop, barbecue places and car washes.

Shelli:

Joseph:

Shelli:

Joseph:

What would need to change so that there would be more businesses?

The way folks conduct themselves up in the White House or in government. They all for themselves and they’re not right here where I’m at. I’ve never received any assistance, no PPA money that I’ve applied for in 22 years. They give money to the rich folks. I did get a stipend from the council and I got barber chairs. I’d like to, if I had some money, get the floor done, the ceiling dropped, add a bathroom, and replace the cabinets. Put a new sign out there. This barbershop is 25 years old and grants, loans, all that stuff, they tell me you got to have this amount of employees or make this much.

• •

Can you tell me more about when you got out of the penitentiary and the women who helped you? What was your experience coming back to Glenville?

I went to prison three times, three drug abuses. I never got no drug treatment in the 80’s, back then they locked you up. White folks had the cocaine, it was powder. I had the rocks. They got probation, I went to jail. Three times, three drug abuses. Oliver North and the Contras and all that stuff let all that in here.

When I got out, I went through the programs at City Mission. And people are looking at this guy right here thinking, “He’s got something special. Let me put him up under my wing and let’s see how far he can go.” A bunch of women helped me coming out of the penitentiary. Six months after coming out of the penitentiary, Miss Tanya Almond and Laurie Murphy,* Janet Robinson, there was an organization called WECO–Working for Empowerment Through Community Organizing. A bunch of Black sisters helped me. Each one of them gave me $5,000, said we’re gonna find you a spot and get you some barber equipment if you change your life around and say what you’re gonna do.

* Tanya Almond, Co-founder + Laurie Murphy, ED of Black Professional Charitable Foundation.

Shelli:

Joseph:

I did every program in the city. Every program that was available in the city of Cleveland. And I completed them. I knew I just got in the wrong place in the projects at the wrong time. And that crack was so strong. I was a good dude, 22 years old, new to the projects, and it just devoured me. Went to the penitentiary three times. Then you take inventory the first two times. Third time I said damn, this is the third time? This has to change. So I took inventory and made a conscious decision. This is pure stupidity. This is insanity— doing the same thing expecting different results.

How long was it from the moment you got out until creating your barbershop?

In September it will be 25 years since leaving City Mission. From ‘95, to 2000, the women in those positions helped me change my life around, gave me a place to work.

Shelli:

Joseph:

• • What keeps you motivated?

Cutting hair. Making people look good. The kids. The people I talk to.

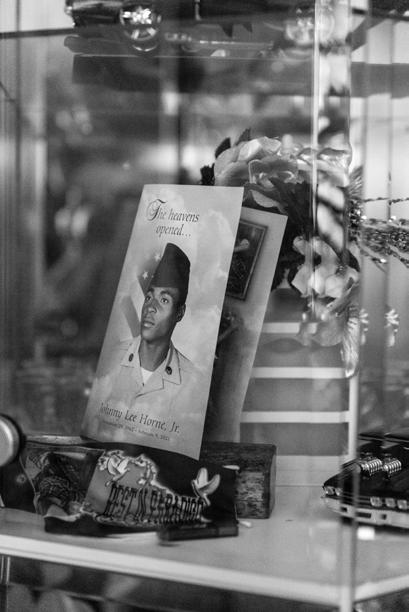

Yvonne Pointer is a nationally known Cleveland antiviolence activist, motivational speaker, author, philanthropist, and member of the Ohio Women’s Hall of Fame. She is the Founder of Positive Plus, a support group for women who have lost children through violence, and Co-Founder of Parents Against Child Killing. She has appeared on the Oprah Winfrey Show after the 1984 murder of her daughter Gloria and is now collecting donations and providing spiritual support for African children. The Gloria Pointer Teen Movement Initiative, founded in Ghana by Anthony Tay, supports West African youth in obtaining an education and a healthy lifestyle.

[Bio via yvonnepointer.com]

Shelli:

Yvonne: Shelli:

Yvonne:

Can you talk a bit about your childhood?

I was born in the Cedar area, grew up in Hough, and moved to Glenville. Our home was noisy because there was nine of us–five boys, four girls, and two parents. So it was a home. It was full of people all the time.

What made that a home?

I think what made it a home was the aromas and the noise. That’s what we knew. My mother used to make tea cakes and I would love the smell of them. We always had family over. So that to me is what made it a home–the fellowship and the participation.

My father would always have family picnics. We had a backyard where he put a swing set and he would always make sure we had somewhere to play. He didn’t want us playing in the street. So he made sure we stayed in the backyard to play. “You don’t want to get hit by a car.” That was his favorite line. I think that was one of my favorite childhood memories, the way that my father was protective of us to try to keep us safe.

Shelli:

Yvonne:

Shelli:

Yvonne: Shelli:

Yvonne:

What are the things that make a home a home?

I think what makes a home is love and peace and fellowship. It doesn’t have to have a lot of stuff. Because you have some people that have nothing, but they have love. Doesn’t mean because you have a beautiful house that you have a home. So I think what makes a home a home is the love and fellowship amongst the people who are there in it.

And why did you decide to make this your home?

This became my home because I was living down the street, and at that time this street was full of seniors. Every house had a senior in it. And if it didn’t have a senior, it had families with kids. Generational homes. There was an elderly gentleman and he said, “I want you to stay on the street and take care of us when we get old.” So he walked me to this house, which was empty, and he said, “I want you to buy this house.” So this is how I got here. And I’m still here. And just like he asked, I took care of every senior until they died on this street.

What were some characteristics of their homes?

Back then, they all had a picture of Martin Luther King and Jesus on the wall. That was the 60’s. They were welcoming. You could tell where a person lives, like, Miss Carnegie lived on the corner and she had a zillion flowers. So what made her home was those beautiful flowers, and you knew that was Miss Carnegie’s home. Miss Woods, again, flowers, just beautiful. And I think people that want to make a house a home need to find a way to beautify it. And that can be whatever you want it to be.

Shelli:

How would you describe your house?

Yvonne: Shelli:

Yvonne: Shelli:

Yvonne:

Welcoming. When people walk through the door, I want them to feel welcome. I want it to be not necessarily spotless, because that’s hard to do, but I want it to be at least presentable so that people will want to come back.

When my daughter was murdered, I was just having an excruciating time with life, and the quietness was disturbing. Because like I said, I came from a house with noise. And so I said a simple prayer: “If I am to be here, if I am to do this, then turn this house into a home. A place where people want to come and visit.” I wanted company, I didn’t want to be in this house alone.

I wanted people to want to come here. Like my favorite movie, Field of Dreams, where they won’t even know why, they’ll just want to stop by and sit on the porch. And I’m okay with that. Because I don’t have to be around you to know that you’re here. I might be in the kitchen cooking, but oh, I know she out there on the porch.

There was a little boy down the street named King. And he just wandered down one day and asked, “Do you have any work I can do?” because he wanted to jump on the trampoline. I noticed that he might be a little tattered. And my granddaughter would say, “Oh grandma, he’s dirty, I don’t want him on my trampoline.” But no. We worked with the Cleveland Police Foundation, we got him a nice bike. And when he comes down, I give him books and everything. Why? Because we’re trying to create communities. And I think that when he grows up, he will say, “There was this lady up my street, and when I was a little boy, and she showed me kindness.” And who knows, that might be crime prevention. I think it is. I think love is a powerful weapon.

What is your definition of community?

Neighbors caring for neighbors. When we were coming up, if you were in the kitchen cooking and you ran out of eggs, you could go up to your neighbor’s house and get an egg. I think neighborhoods and communities are about sharing and fellowship and concern. When I used to do the midnight basketball league, my neighbor, Miss Franklin wouldn’t go to bed until I came home and she would hear the car door slam. Neighbors care about one another.

• •

Could you talk about how the prison system, when you go in, is a home away from home?

I’ve been going into the prisons for over 35 years. The reason I call it a home away from home is because there are people who have been incarcerated, and in spite of the darkness, their light still shines. They’re highly creative human beings that can still create in spite of that. They’re criminals, don’t misunderstand, but when the two lights meet–when I go into this darkness with my light and I see a light, and then the two lights connect, we form these incredible bonds. I give them hope and they give me hope. The hope that in spite of this circumstance, you’re still in your right mind, you’re still creating, you’re still writing, you’re still singing.

• •

Shelli:

Yvonne:

Shelli:

Yvonne:

What do you want people to know about you?

I would want them to know that I still live in the community, I still believe in the community. I think the best way to describe me is that ‘she has hope for her community, and has never given up.’ One person can make a difference. And if you find a dark corner in your community, then you be the light.

You can do something as simple as plant some flowers or pick up trash. I think the responsibility for a better world lies with the individuals. Stop expecting it from the mayor, the president, the governor, and you be the change.

• •

What keeps you motivated?

What keeps me motivated is hope for a better world, and the contribution I can make towards that. On my weary days, I think about those who are less fortunate.

One day after my daughter had died… I was just…. not going to make it. It was something about the stillness and the quietness of the night, and all I could do was cry. I asked God a simple prayer, “Would you please come and get me?” I did not want to be here. Now, I didn’t necessarily want to commit suicide. I just wanted out. I just didn’t want to be alive. And so I went downstairs. And on the way back up the stairs, I realized I didn’t have strength to even go another step. And I just kind of leaned against the wall and cried even harder. I said, “Would you just please come and get me?” And God, who is real and a present help, was almost right there and giving me a plethora of reasons to live. What about your children? What about this or that? I would respond, “That’s not a good enough reason, come and get me.” And then finally, the last thought was, “Then, I will be your reason. I’ll be the reason you get up.”

So what keeps me motivated is service. Service saved my life. If it wasn’t for service, I wouldn’t need to be here. When I get up, even today, even with this interview, I’m thinking, what service is this going to render? This is my purpose. This is my reason. And when I’m done, I’m okay with leaving here, because I believe that there’s a better place.

Like the schools in Ghana, I had someone who gave me a nice donation to help feed the children and educate. So it’s the service to others, like, I get to make the world a better place. And somebody might say, “What’s in it for you?” Well, the fulfillment of knowing that you’ve done something. People complain about the problems. And I want to know, well, what have you done? So that’s what keeps me motivated. Service.

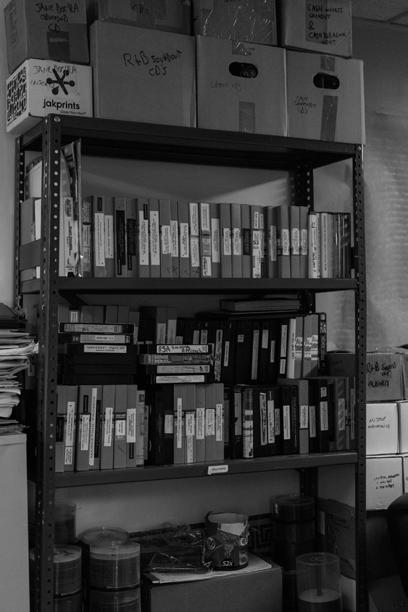

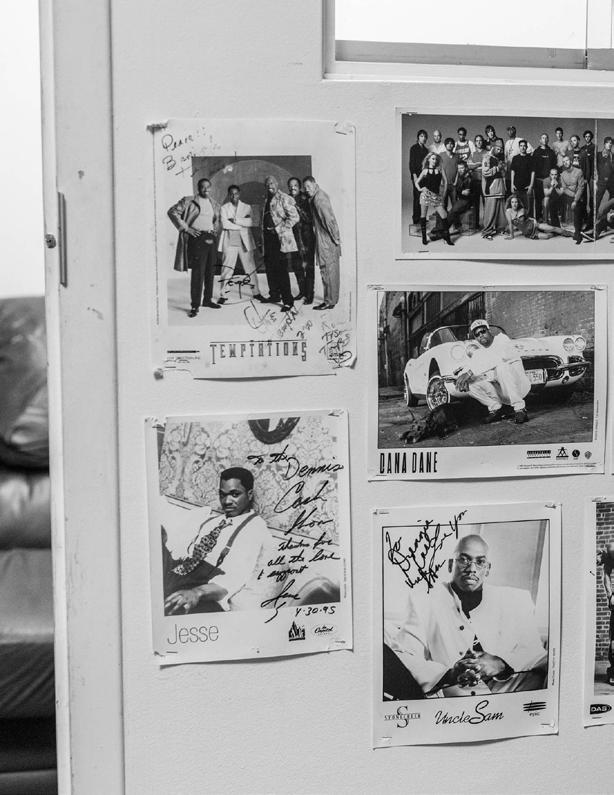

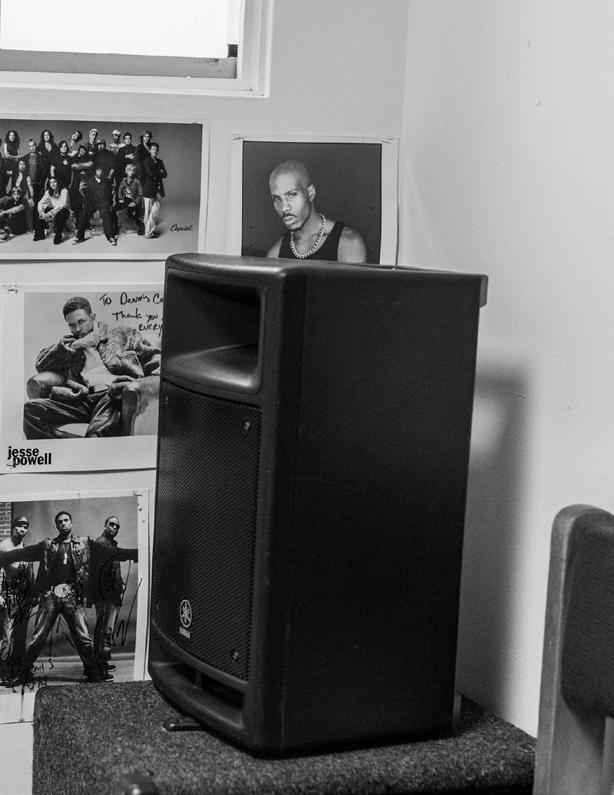

Dennis Cash is a recording artist, community activist, and resident of Mt. Pleasant. Cash’s scope of work within the entertainment industry includes television, music production and promotion, record label management, and more. Cash’s major musical projects include Erroll Gaye and the Imaginations (later called The Imaginations) and CA$H.

In 2016, Cash founded the Survivors of Violence Conference and Concert Series centering survivors, families, and communities impacted by gun violence in Cleveland.

Shelli:

Cash:

Shelli:

Cash:

Because you’ve had so many opportunities, traveling with your music group and doing video production, why did you choose to stay in Cleveland?

When relocating, you have to leave a lot of things behind. You know, family, opportunities. I thought the base here in Cleveland was strong enough to really create some things and bring something here.

Had I moved out of town, I wouldn’t be doing the things that I’m able to do today. I would have probably been successful in New York or Atlanta for what I was doing. We took kids off the streets, literally. When I look back, we provided a lot of opportunities for kids in the neighborhood and community. All kinds of people would come to the house and studio, trying to learn how to sing, dance, whatever. To this day there’s always somebody I run into saying, “I remember coming to your house,” or, “You don’t remember me? I recorded my first song there.” I can honestly say the good thing about what I did, it touched a lot of people. And people could have been doing other things with their lives. Getting in trouble. But they came to us.

We were fortunate because when the height of the crack epidemic hit Cleveland, we were probably about 23. So we had experienced things already. We weren’t young enough to where people can really influence us, so we missed that. The younger guys who didn’t know better were getting caught up. So that kind of did me some good to where I was able to get through a tough time in our community. I’ve seen a lot of guys on and off that stuff, people got messed up on it. A lot of people didn’t come through it. Some people did, but it messed them up 30 years later. So we were fortunate at the age we were when it hit Cleveland, because if we had been 17 or 18, ain’t no telling if we could have gotten swept up in what swept through our communities.

So if I had gone out of town, there’s no way I would be doing the things that I’m capable of doing the best, because I’d have been detached from the city.

I would love to learn more about your home.

When we were small, we had a lot of brothers who would have basement parties and all that stuff. We would hide and watch them slow dance with girls. Then my brother and them started rehearsing in the basement. And that was a big thing, to see a full band down there practicing. Back then everybody played, because there weren’t no samples and all that stuff. So when we got old enough, we started rehearsing in the basement. For years, the kids in the neighborhood used to come and look through our windows, like, “Cash and them are rehearsing!”

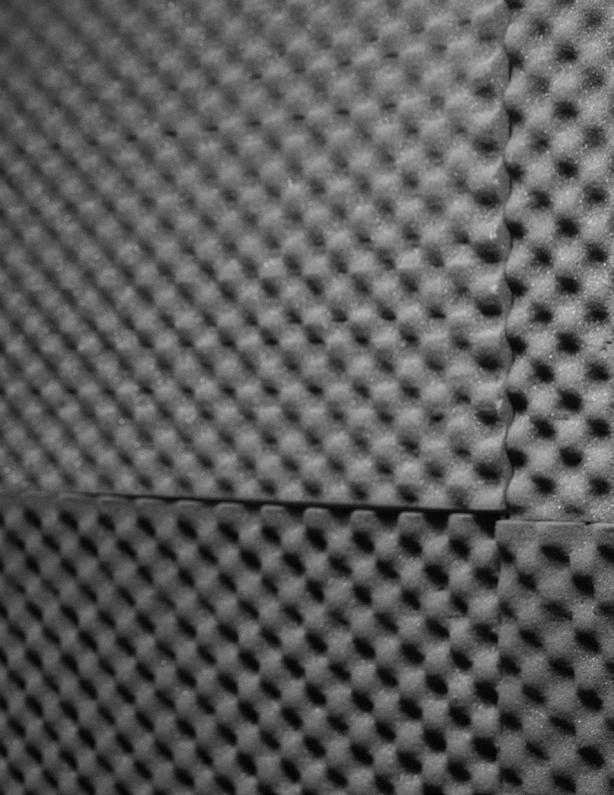

When I started doing production, we couldn’t afford a studio or nothing, so we made a makeshift studio down in the basement. We just learned how to record on a 2 track recorder. Like, “Gotta sing, try to get as close as you can!” And we started trying to make records like that. Then we graduated to a 4 track recorder and you couldn’t tell us nothing then.

Our preacher at the church, he came down. We would go find these artists and say, “We got a studio, come on over and we’ll produce you.” And that’s

Shelli:

Cash:

Shelli:

Cash:

what we started doing. They would come down, we’d make beats, they sang and wrote the songs. And from that point I got into television and learned how to get big sheets of paper up on the walls and dress it up, cover the ceilings and everything, make it look like we were in a studio.

Next thing you know we have people down there–we’re filming Rob Johnson, the line dancer who was very popular in Cleveland. I produced his first video in my basement. Found him on the basketball courts, produced a video on him and put it in the cell format. I was doing some unbelievable stuff with no money. We didn’t have money, we didn’t have no company behind us, we just had drive and believed. And I can say that I wouldn’t trade none of it for the world. I know a lot of people who have money that backed them, and I could outwork them any day of the week. And I understood why. I understood what I was doing from the ground up.

What has it been like living in the same neighborhood and house, and how has that journey been for you?

It’s really all the same, like I never left. Some people moved out, family members and people off the streets. The neighborhood is pretty much the same. Looks good. We got one of the decent streets in the Mount Pleasant area. It’s been a blessing for me to grow up in this house and it still looks good. Might even set up a movie for the neighborhood kids in the backyard, I might do that today or tomorrow.

Is there anything in the neighborhood that you want to see change?

I don’t think we understand our culture enough. If it hadn’t been for what I saw other people do, I wouldn’t be doing this. I might not have taken the same path. But I got advantages by seeing and learning how to grow from what I saw.

But that’s what’s missing. And it all came from how they separated our families. We can’t get around what has been done to our community, which is what white folks are going through now with the opioid crisis. It’s gonna take about 25 years before it hits them. Best time in our lives was in the 70’s till about 1983 before they destroyed our neighborhoods. Everybody had mothers and fathers. And then came the crack, and for 10 years, people made money off it, it ruined families. The whole picture of crack went from what it did to us then to what we’re still recovering from to this day. So we’re going on 30 to 40 years. You can’t replace a missing dad. And it breaks down further and further—all of a sudden you have women doing without men now, raising kids without a dad. Look at how we just screwed up. That’s the only thing that I would want to change, but as long as we’re apart, that ain’t gonna change. You can’t expect young people to raise themselves and know better in life.

• •

Shelli:

Could you tell us about Ms. Ross’s Talent shows?*

* An annual talent show at the Agora Theater showcasing young and emerging local talent. Hosted by Ernestine Ross between the 1960s-1997.

Cash:

Shelli:

Cash: :

Well, you couldn’t be on Ms. Ross’s Talent Show unless you were good and you followed her rules. You had to rehearse and you had to dress up. She was old school. And she was gonna polish you up.

When we got on her show, we were lucky. Because when we first joined, we were just a regular group and wanted to go try it out for ourselves. But when we joined Erroll Gaye and the Imaginations, we were professional. And she got her money’s worth out of us.

We came in dressed all up and put it down. But she set standards that helped a lot of people go out and compete. She was a true real deal warrior for her worth to entertainment. Ms. Ross was no joke; she was tough, she’d cuss you out in a minute, but she did it always in love.

Can you describe what it was like to perform?

It’s a blessing to be able to get up and do what you rehearse. To sit in the basement and practice and learn and get it together, then have people react to it. And shall I say, kind of give people something to hold on to, a piece of you, by them seeing you sing and dance. We understood it was always a blessing to be able to perform in front of people. That’s what kept us going. There was no big performance that outweighed another. To us, they all was important.

The only thing that was different for me was the very first time I performed. I can tell you I was scared to death. We did Alexander Hamilton’s** talent show in seventh grade. And it was the first show we did at the time. I had a guitar, my brother played the drums, and we had this dude about six feet tall in the seventh grade who played the bass. We practiced some record we heard, and we only knew a couple of parts on it, and we played that little part of death. And when we hit that stage, I could have swore that I was falling out of a plane, that’s how scared I was.

And them girls went crazy.

We don’t know why, we just kept playing. All they talked about was the twins (me and my brother were twins) but we don’t know what we’re doing, we just wanted to do it because we saw my older brother do it. So for the next week or two they was basically carrying us around the school on their shoulders, talking about the twins. So we decided that if being a band was really what we wanted to do, we needed to sing. We didn’t sing that day, we played instruments and didn’t say a word. We had these little hats, looked like Michael Jackson when he first came on Ed Sullivan. And we put a group together called Four of a Kind. And when we came back in the ninth grade, we started putting it down like that. And we never looked back.

And that’s when somebody discovered me and asked me if I would join Erroll Gaye and the Imaginations.

Former Junior High School in Mt. Pleasant.

Shelli: Cash:

Shelli:

Cash:

The landscape of the venues where people can perform now has changed a lot. Can you tell me about some of the venues that you played at that were on the east side of Cleveland that are no longer there?

Of the ones that are no longer there, Front Row Theater was the biggest one where all the stars would come at. Vel’s on the Circle. Reason Why was in Shaker. Native Sun on this side of town. There’s a lot of those type clubs that maybe had about 300 people max. Gerald Levert had a place called the 3030 Club on 131st and Miles, that’s gone. I’m sure there’s plenty more. But we played a lot of places like Music Hall and Public Hall and they’re still around.

• •

How would you describe home in a few phrases?

Home to me has always been safe. No matter what I was going through. It was a safe place. My mother’s still there. My mother is ninety now.

Home is fresh. I can always start fresh. If I have problems in the industry, I can always start over again and refresh myself, because I didn’t take this stuff home. I work hard on what I do, put in 100% when I come into work. When I go home I don’t even listen to music.

Initially I used to play a lot of sports, but I’m too old to play now. So I learned how to do it at home. It’s just like when I go to church. The reverend wanted me to join the choir, but I didn’t want to do that. Some places I want to go and I want to be the subject, the audience.

Cleveland is the same way. I’ve traveled all around the country, then get tired when I’m out on the road somewhere. You go through what you go through, then you get back and you have a sense of familiarity. That’s how I view it. I didn’t move from here for a length of time. You know, I didn’t go stay in the city for six months or something. So my strings attached here, it’s pretty much etched in stone, is what it is.

• •

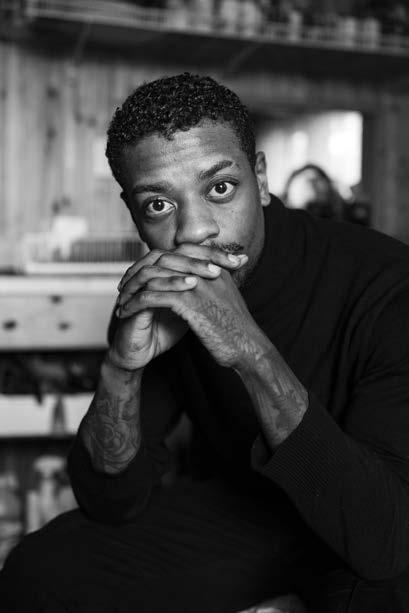

Ronald Freeman is community activist and Cleveland native.

In July 2021, Freeman helped stage a sit-in at the Independence Ramada Hotel when 100+ unhoused men seeking emergency COVID-19 shelter were forced out by the city. Ronald advocated for the unhoused men who, like himself, were immunocompromised and in most dire need of protection from overcrowding during the pandemic.

Shelli:

Ronald:

Shelli:

Ronald:

If you could describe your ideal home, what would it look like?

It would be spacious. It will have a nice basement in the building. Nice neighborhood. I would like to be around plants and things like that when you walk up and down the street. I don’t know, how can I think about the idea of home when I’ve been through the stuff I’ve been through with home?

I knew home when my mother was alive, when I stayed with her as a child. That was home even though it was the projects because she made it home.

Can you share more about your childhood, when you really felt like you had a home?

My father got killed when I was about seven. He won two Golden Glove tournaments here, he was a welterweight boxer and was getting ready to turn pro. And he got killed. I never experienced brutality at the hands of my father. When he died, my mom never remarried. She raised us the best that she could as a single woman. I don’t think her education was that good so she never had one of these high paying jobs. We went from projects to projects, to a house here, to a house there, projects, projects.

But with her, she was home. No matter where we were, I felt comfortable. A lot of times we didn’t have heat, we didn’t have electricity, we didn’t have food to eat. But my mom always made a way. She was like Superwoman.

My childhood was strange because I wasn’t like the rest of the children. On Saturday and Sunday, even in elementary school, my idea of fun was going to the library and getting a whole bunch of books on animals and dinosaurs and history. I used to sit around the kitchen table reading and I had a ball. My mom used to force me out of the house all the time. But she didn’t know, I don’t hold it against her, she just didn’t understand it. I even had a thesaurus and a dictionary, and I used to sit there and read it because I was always fascinated by all of these words. And it was painstaking but I went through the whole thesaurus, the whole dictionary, all the books

For me, home wasn’t the complexity of things, it was the simplicity of things. When you were home, you were safe. We could leave the front door and the back door open in the summertime and just lock the screen door and nobody was coming in there.

When we were young, we didn’t go through this… I mean, we were in the projects, but I was there with my family so it was home. The cooking, the smells, fighting with my sisters…. they used to devastate me because there’s six of them and they would gang up on me and bust me up. But I loved it because I used to laugh.

I started practicing Kung Fu at an early age. I rode bikes, I liked nature, we used to go to camp. I stayed in shape. That was something that I loved, was fighting. We used to fight in underground garages, driveways, lawns, the street. We didn’t care, we would fight on the rooftop if there was room up there. I loved martial arts and I was really brutal with the stuff.

Ronald:

And when the police and the dope boys did what they did, that was still a part of my childhood. My mom and others in the neighborhood didn’t want this stuff over there. But all of these older sisters ain’t gonna say nothing because they’re older and a lot of them are single and their sons ain’t worth the spit on the sidewalk or nothing. So it kind of interrupted my world and I went out there and did what I felt like I had to do.

My life has always been like that. Fighting, fighting bullies, fighting for other people. Fighting for myself.

My mom told me before she died, “There’s a lot of people out here that you’re gonna have to help when you get out of prison.” I’m trying to honor that because I said, “Yes ma’am,” and I said that in my heart. So I’m trying to do what she said and I’m trying to remember her in that light.

But as far as home… I’m a 65 year old man and they’ve been locking me up since 1973. I never had a chance to make a home for myself. This is all I know, this, since I’ve been out of the penitentiary.

After 30 years of incarceration, they gave me what they call kitchen whites–when you work in the kitchen you wear white pants, white shirt, like a kitchen uniform. After 30 years, they gave me that in the wintertime along with a disgustingly thin windbreaker when it was cold as hell outside. They gave me a few dollars in a check and put me on the bus and sent me back to Cleveland after 30 years. They didn’t have nowhere for me to go, they didn’t care. They just put me on the bus and said go. What kind of shit is that? No support, no nothing.

There was a sister on the bus, bless her, we talked and she was like, “Don’t worry about it, I’m gonna take you somewhere.” And when we got into Cleveland she took me to a Dollar General and bought me a sweatshirt, she bought me a hat, she bought me some gloves. I said, “Why are you buying all this stuff for me?” And she said, “Because I’ve been locked up before, I know how it is.” It was so beautiful.

But I don’t have a home, and I’ll die before I call this home. I keep it clean because I’m not filthy, but this ain’t my home. I’ve lived in three apartments since I’ve been out and got kicked out and two of them. I’m probably gonna get kicked out of this one too. I don’t care. I’ll leave all this stuff in here and take a knapsack and put a few clothes in, and I’ll leave. Because this ain’t my home anyway, I don’t have anything to lose.

Besides with my mom, I don’t know where home is. Sometimes home is not a geographical place or physical place outside of you. Sometimes home could be inside you too. So I think that’s the most I can understand about home. It’s what’s in my heart and in my spirit and in my mind. And I keep striving for it. I end up in the shelters or rooming houses, a hotel here or there. I’ve been out since 2008 so this is how long I’ve been struggling.

Shelli:

Ronald:

Ronald:

Can you share more about that bus ride coming back to Cleveland? And your journey has been since you’ve been back?

I was excited, and I was nervous. I did the same thing then that I do now. I’ll pace this apartment, from the bedroom back to this window until like five thirty, six o’clock in the morning. And I don’t have any idea how fast the time was going. When I was in the apartment of the PICO towers, that was the first time I’ve ever lived by myself besides being in a jail cell. And the crazy thing was, at eight o’clock every night, I made sure I was in that apartment because at that time, in the penitentiary, it’s almost lock up time. And in my mind, I actually thought that people weren’t out past eight o’clock.

A psychological thing happened to me one time. I woke up and I was in the refrigerator or something and it dawned on me that I was in the penitentiary and now I was living by myself, and it was too much. I tore the whole apartment up. I turned everything over. I threw things at the wall, and I clocked out. This is what these prisons do to us.

• •

I look at real estate places on the phone sometimes and they’re remarkable. And I see some of those houses. And I’ll be like, man that would be a great home. If I could afford a nice house, that would be a home for me. If I could afford to get me a house for 300, 400 thousand dollars, I could call that home.

And it ain’t just because of the size of the house, it’s what I’ll be able to do with the house. You get a house like that, you’ll have like 5, 6, 7 bedrooms. I can put somebody in this room, I can put somebody in that room. I can fix this up, I can bring these people in here, I can love these people. I can raise these people, I can educate these people, I can help these people financially. That’d be home to me. That’s home to me. Being able to serve my people in that capacity.

I go up and down the street sometimes and an older sister will ask for a dollar, and I don’t have one. And the shame and anger and guilt that I feel is deep, it’s a scar. Because here go my people asking me for a dollar and I don’t even have a dollar to give them.

If I had millions of dollars, I can guarantee you one thing, that money wouldn’t be in my house. I wouldn’t be sitting here with a lush plush nothing. I would be dressed in the same way that I dress, because it’s not important. What’s important is these people out here. I was born and I was destined to help my people. I love them, even the ones that are incorrect in what they do. You look at what we’ve been through historically, and you can understand psychic trauma. It’s a generational thing. It’s genetic.

I would like to take a handful of these sisters to Great Northern Mall and shop until we drop. Let them buy clothes and shoes and jewelry and take them to a beauty salon and let them do their hair and nails, take them to dinner, eat with them, bring them back, and give each one of them like a few hundred dollars a piece. That would be a wonderful day because I know that

Shelli:

Ronald:

would build them up so much from what they’re going through out here.

If I could do a podcast [in this apartment], I’d be comfortable enough to call it home, because I’d be doing something positive.

I don’t need to take any notes. I don’t need to read any books. All I got to do was put my equipment here and talk to people. I would like to have African garb on–my peoples’ clothes that I’m comfortable in–and sit here and talk to brothers and sisters about politics, spirituality, religion, history, about all that’s going on. I would like to have a man on the street thing on Friday where I can get myself a portable camera, put like $1,000 in my pocket and make the journey that I make every day, go all the way down and come all the way up. Every time I see sisters and brothers out there, no matter what’s going on with them, we laugh and we talk. And we sit there and we smoke cigarettes and we laugh and when it’s all over we embrace. This is my purpose, to serve my people.

• •

Who would you like to have as your podcast guests? It could be anyone, dead or alive.

I would like to put Bruce Lee on the Podcast. I would have Stephen Hawking. I would like to have Maya Angelou.

I would have a lot of sisters on there, because I’ve come to the conclusion and understanding that sisters are powerful as hell for real. You got sisters out here that prostitute for crack, to get drinks. You got brothers out here that sell crack, that smoke crack, they’re homeless, they sleep in bus stops. But when you put those people in the situation where they’re comfortable and you can talk to them in earnest, you would be surprised at some of the knowledge that comes out of those people.

But the world hides this. When you see a podcast, you don’t see people talking to these people. They’re trying to talk to people that are acceptable to society so they can get more listeners to make your podcast more popular. My aim with the podcast is to bring light and enlightenment and joy and love and purpose to people.

You’re not a piece of garbage because you’re a prostitute and you smoke crack. You come from royalty, you come from queens and kings. We had the only civilization on this earth. This ain’t no civilization, these people are in a technological state of barbarism. We had a simpler life. We didn’t have poor people. We didn’t have diseases. We didn’t have crime. We didn’t have a lot of that stuff.

• •

Ronald:

When you came to East Cleveland in the 70’s, it was beautiful. If a Black person said they lived in EC, you knew they were making money. All of this was habitable. All of a sudden, they flooded EC with dope and everything and it

Shelli:

Ronald:

ended up being what it is. This ain’t the first time that these people took our affluent neighborhoods and destroyed them because it was Black.

Black people ran Congress and the Senate, they ran all that shit. They took it from them after they saw the power that was inherent in it. Every time we try to build something ourselves, they tear it down. And they do it on purpose. I want to talk to people about this stuff.

• •

In the last 15 or so years, what has been a highlight and what has been a low light of your time?

This is a highlight for me, the love for my people. Even when I don’t have any money, I can still go out there and encourage and laugh and talk.

A low light is this… Eden housing. When you’re in a situation like this, ain’t no autonomy. You are on a leash. There’s certain things that you can do and certain things that you can’t do because it’s Eden housing.

I suffer from depression sometimes. A lot of times, actually. I really think that subconsciously stuff like this is why I’m depressed all the time. I want to be free. I want my own place. I want to know what it feels like to not have to worry about where your next meal comes from, or how your life is gonna go. I want to be able to know what it feels like to come and get some people that’s whipped and probably on the edge of suicide and take them somewhere, and when I’m through with them, they’re gonna be standing upright and they’re gonna have their heads up in the air and they gonna be like, “I really am somebody.” But I can’t do that here.

This is a low point. That these people keep putting me in situations like this. This is a contrived thing– how the fuck I’m gonna come off the penitentiary for 30 years and y’all gonna stick me right back in the same environment that’s in the penitentiary?

• •

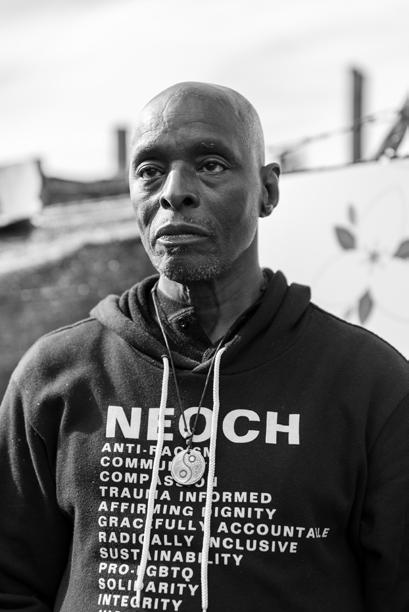

Loh is a community activist working with the Northeast Ohio Coalition for the Homeless, the Poor People’s Campaign, and the Homeless Congress. Loh is currently helping develop Cleveland’s Homeless Bill of Rights, which is modeled after similar bills passed by state legislatures in Illinois, Rhode Island, and, Connecticut, and those proposed in California, Colorado, and Washington.

Loh:

Shelli:

In any age, any level of education, society has collectively and successfully produced a population of people who can only go among jail and prison, homeless shelters, the street, psych wards, and treatment centers–especially inpatient programs. Society has successfully created this population and it’s getting bigger. Because for years and years, decades and decades, even centuries, we’ve had the strong ruse of discrimination, all different kinds, much less racial. The worst one actually is gender discrimination. Then you have people systematically putting out legislation and all the important components in our public education systems and public health systems that reinforce this.

When I say gender discrimination, let me give you an example. Look at the shelters in town using public dollars–we only have two now. One is at 2100 Lakeside Avenue, so the nickname is ‘“2100”’. It’s supposedly for single adult guys. The other one is for single adult females. I call it “The HELL”. The current name is a disgrace to the person they put as a namesake on the building. That old lady’s name is Herr. Somebody changed RR to LL. I found that to be a very good fit, so I followed suit.

“2100” has almost double the official beds to “The HELL”. Actually, if you look at the fire code, both of them can only have 300-some beds. But we know in reality, especially before COVID-19, “2100” could get people piled up to over 500. But at “the HELL”, in the first half of the last decade, there were 170 beds. Versus 365 official beds for “2100”. Why? Can you tell me, even just in the census, any decade, when has Cuyahoga County only had half of the female population than the male population?

All the famous institutions and nonprofits may do good. But do you know how these organizations started? Even 100 something years ago, they all started as rich white females helping the poor females on the street. That means our society never allocated any resources to help females.

Due to other factors, our shelter system is not only housing people from poor neighborhoods within Cuyahoga County. Our shelters have people from other areas of Ohio. And that doesn’t just include Akron, Summit County, Medina County, Lake County, or Lorain County. Even during COVID-19, we had people transported, I almost say shipped to here from a place just north of Columbus. We have people stranded from other places in the country, stranded here in Cleveland.

The problem here is that the poverty is growing bigger and bigger. If you look at the statistics shown by the Poor People’s Campaign, before COVID-19, they already found that number. If you call this the richest country in the world, why are 42% of people living on or below the federal poverty line? Now it’s even more. Some people will say Cleveland is having a Renaissance. Some people just want to look at the good part, that pretty part of it. And not look at the real part. The other part that exists at the same time, in the same space. Because out of sight, out of mind.

Do you feel like housing is almost like a tool of the larger system to keep people separated?

Loh:

Yes, of course. I support another project called People’s Street. The first project we did was on Payne Avenue where “The HELL” is, because we found out that the way they built the highway was to segregate people. At that time, “The HELL” was not there, that section of Payne Avenue was Chinatown. We found out that Payne and St. Clair were both put into segregation because of the way that particular section of highway was built. So in People’s Street, we are trying to restore the connections from different little neighborhoods to other little neighborhoods. To bring people together.

The people who were segregated between Payne and St. Clair did not have that much of a voice to resist. They did not understand that building the highway would be bad. But now, if we get a certain kind of education, we don’t need to see the result; we can actually predict that if you do this, that will happen.

• •

Shelli:

Loh:

Shelli:

Loh:

When did you come to Cleveland?

I have been in Cleveland for a while. I came to Cleveland because of CSU. But unfortunately, my eye got injured. There were strong winds one morning when I was on my way to the job that I worked on campus. The wind blew something into my eye. So, it changed certain things. But at that time, nobody would know that eventually the recession would change the whole country. Due to my condition, I could get away with certain things. I didn’t do fixed-hour jobs. I could do tutoring. To a certain degree I could control my time. But that kind of job unfortunately does not help you to create the track of the regular working history records. At that time, at least I could make my ends meet. Sure, not high income, but at least I could pay rent.

So why did you decide to stay in Cleveland?

I had a family member on the other side of the country telling me to leave. But I thought, because I wasn’t hit directly, I could still manage during the recession. Plus, there are certain things I like about being here. I don’t like the politics so I didn’t pay them any mind, but those same problems are in the whole country.

So throughout the time I was at CSU, I had to drop out of classes, trying to do different things. Coincidentally, I started helping people living in the Chinatown neighborhood, because I moved into a duplex there. The neighbors downstairs didn’t know much English, and they didn’t know much of the system. They’re here doing well, trying to raise their kids. When I was there, one actually graduated from Case and went to New York for advanced studies. The other was at St. Ignatius High School and graduated. The parents worked hard, but they didn’t know much about the legal system, welfare system, etc.

Living in the area, I got to know others and so I got a chance to help people out on a different scale, in different areas. In the past, I helped people with school, with jobs, and other things, but not based on having low income and

Shelli:

Loh:

living in poverty. Now, it’s more about poverty. From the time I started learning and helping them with programs, vouchers, foodstampcards, Medicaid, all those things, I knew that if I fell into poverty, these things may not work.

Disability is not a guarantee, because everything that this country offers is about qualification. That is a reason why lots of good ideas start here, but they do better in other countries. Here, people are still in the mentality of division. Qualification is the key to kill everything. Think about the difference in healthcare between this country and even Canada or other European countries. This is the only country in the first world, the so-called richest country in the world, that has no universal health care.

Housing is another issue. If you make money, you think you’ll earn your place to live in a good neighborhood. So homeless people, because they make mistakes, they can only live in a crappy place to continue their homelessness. Because don’t forget, they are homeless because they escaped from their bad neighborhood, trying to get into a different neighborhood so they can live. But now, you push them back. The current housing system actually pushes people back to where they escaped from. Maybe not exactly the same street, or same neighborhood. But it will be from one high-crime area, food desert with drug issues to another food desert area with high crime and drug issues.

Not even a couple months ago, Florida wanted to move homeless people to an island outside the whole peninsula. And that place was right next to a chemical waste facility. Right now, we have at least 66 big cities criminalizing homeless people by using law enforcement. Washington DC, New York City, all the big cities in California and Florida, all these places tried to match these states or cities to the state’s returning federal government’s rental assistance.

• •

How are home and housing different? And what is your definition of home?

Home actually has feelings attached to it. Homeless people, if they are in the shelter or on the street, and there are a few of them that stay together and watch over one another, they have a home. So they don’t have a structure as a house or apartment, but they have a home.

Home is where you feel comfortable to stay for a long time. Where you feel comfortable and you actually can live well and progress, that’s your home. So it’s not only a structure, it could be the people around you. That’s why living in the right neighborhood is important. Let’s say there’s a homeless family with maybe six children, different ages–you want them to move to a bad neighborhood with no good school in the district? How will they be able to thrive if they’re not close to the healthcare facility they need to go to, not close to the job they can go to?

Right now if you squeeze everybody into a place on the floor, that’s their home for the time being. Is that comfortable? Do they have a home? Not

really. However, if the people in charge of the space are nice to them and help them out, and other people staying in the same space are friendly and help one another, that’s their home for the time being.

If you live in the tents–but other people are in other tents and you guys are actually together, watch out for one another, getting things for one another–when you go back to that tent area, you actually will feel good. Like, “Oh, I will bring this to Mary. I found this in a dumpster today, and she needs this.” That’s the feeling of going home. But what kind of home that is is a different story. That’s why the tent, even if it’s not good, is a home because your neighbors, Mary and Bob are nice. Lakeisha and Duane are nice. They helped me to watch my pet so I could go out to get my medication, and I found this in a dumpster, Mary said she lost hers.

People living in a mansion may say, ‘What would I want from a dumpster? I’d rather order one customized with big money.’ But that’s your home, you do what you see fit. In my home, I can find this thing that Mary needs. That’s the feeling. For someone living alone–even if you don’t know your neighbors, at least they don’t bother you, they don’t come to shoot you or cuss you out, the landlord doesn’t try to solicit sex out of you to pay rent, you don’t have all this pressure–even then you have a home. You have a good feeling. Because when you’re tired, nobody’s bothering you.

• •

We have people coming back to shelters because they used their own money to rent an apartment and they still got sexually harassed. That’s because they didn’t have a voucher. With a voucher, they actually probably need to think, will you report me? Without a voucher, renters have no protection. And not just the extremely poor people, and not just in extremely low-income rental properties. Our renters overall do not have protection. That’s because a long time ago, in the Ohio State House in Columbus, the rich landlords could afford the time and the means to get lobbyists to convince the State Legislature to make a landlord-tenant law only favoring them. Ohio is one of the five states that actually has a law saying if you are even one day late to pay your rent, your landlord can file eviction.

Maybe your landlord won’t apply it. But this problem, theoretically, can happen to any landlord. But in reality, it happens mostly to the landlords who want to flip to get tenants to pay higher rent—the slumlords. If your building is decent, the landlord is probably happy to have the current tenants. All the tenants have a job, actually have something. But the slumlords are the ones who mostly will use that law. Poverty is a huge issue for that reason. Because there are so many tools out there. You pay one day late, your landlord can apply that tool. But if the landlord didn’t know about it, lucky you. If that landlord didn’t think about it, lucky you. But because this is already in the law, theoretically, everybody can be in danger.

This is something I’m doing in order to get things done right, to really fight against social injustice. If you are organizing, it’s not the homeless people you should organize. You should organize the people who have the time,

energy, and means to learn new things and to stand up and raise their voice. Because these people mostly vote and pay taxes, and that can be a threat to legislators.

Lots of legislators right now are in the pockets of the .0001%. They don’t care about homeless people. This is a reason why they want to push more people into poverty. Because the poorer you are, the less chance you will think about voting, and you definitely have no means to pay tax anymore. So they have a good excuse to say, ‘They are not even taxpayers, they are utilizing the public dollars. See, they are wasting your money.’ This is how they can divide people. This is how Trump and other people win elections like that. Politicians will go down to Southern Ohio and tell the white people there, ‘Why do you think you have no jobs? Because of all those Black people are taking your jobs away.’ So those people will think the same thing, they do not have the adequate education for them to know what to think.

Black people here are educated by their own neighborhood. They know they have been discriminated against. It’s not completely untrue, but they forgot to mention the other part, that right now you have the tools to do something different. They were blocked away from this message. Poor white people down in Southern Ohio, they also don’t know anything better.

Do you know that in Southern Ohio, sometimes you have three counties to share one public housing authority or even one hospital? That’s how poor Southern Ohio counties are, and they’re all white people. And if they’re sick, they have no place to go. There are probably three counties with no real hospitals. Food deserts, same thing.

If we can get Southern white Ohioans and Northern Black Ohioans to see how each other lives, they will both have a cultural shock. The whole country right now is run by lies to divide people. The political part of it. The education part of it would have given the truth, but all the social sciences have been taken out for decades.

Robin Lamont is a Cleveland native, US Military veteran, and professional event planner. She is the Founding Owner of Elegant Interpretations, a Cleveland-based hospitality and event design service.

Lamont has worked as a youth mentor at John Adams High School as well as Positive Plus, a support group founded by Yvonne Pointer for women whose families have been impacted by violence and assault.

Shelli:

Robin:

Shelli:

Robin:

How long have you been in Cleveland?

I was born in Cleveland and have always been here, except for the 8 years of my military career.

Did you go into the service right after high school? Where were you stationed?

Yes, I did. I was stationed in Washington during my basic training and specialized AIT training. I was in New Jersey, at Fort Dix and in South Carolina, at Fort Jackson. Then I went overseas to Camp Darby in Italy. And from there to Fort Lewis in Washington.

I didn’t plan to come back to Cleveland. I came back because my mom was in a bad car accident and they weren’t expecting her to recover.

• •

Shelli:

Robin:

Shelli:

Robin:

Can you tell me a little bit about your kids and being a mother?

All four of my kids are adults. The baby is 31 years old. My kids were born in Washington, except for my daughter. She was born overseas in Italy. And my kids were born while I was still in the military.

What is your definition of home?

I don’t consider a location, specifically, to define home. I have often heard the saying, “Home is where the heart is.” So I believe wherever me and my loved ones are, that’s home. My parents still live in the house that I grew up in. So when I go there, that feels like home. And now that my kids are adults and come over to my parents house, when we’re all together, that’s home for me.

Just last week, we had a family game night. Because my dad is sick and bed-ridden now, he can’t leave the house. That’s why we do major holidays and activities at my parents house, so that my dad can be included as well. So we all got together to keep my mom from having to cook all the food because she is the sole caregiver for my dad. We had a potluck and we all brought food and drinks, and we played games and laughed. And that’s home for me.

Shelli:

Robin:

What are some of the things that make your house a home?

I have a lot of pictures hanging on the wall and sitting on shelves and in my office. I have an office in my house that has a wall of relatives, family members, and friends. My basement is finished so it’s as they call it a “man cave,” but I call mine the “dames dungeon.” Me and my girlfriends are sports fans so we watch the football games down there. I have a big screen TV and a mini fridge for our drinks. It’s kind of like a den with everything in there.

I have some things that my mom passed down to me. I love curio cabinets.

Shelli: Robin:

Shelli:

Robin:

So I display some glassware and china and things like that. But mainly my pictures are the most important thing to me. I have some little figurines and some older photos, photos of my grandparents, and old photos of my parents when they were my age and younger. I also added to my cabinet a little remembrance section for my brothers.

Were your grandparents also from Cleveland?

No, my parents weren’t from Cleveland either. My mom is from Mississippi and my dad is from Alabama. They moved to Cleveland when they were younger and met here.

In the beginning of our conversation, we talked a little bit about perceptions of people who have been incarcerated. And I would love for you to share a little bit more about that part of coming home for you.