This page was intentionally left blank.

This page was intentionally left blank.

Caroline Wiggins, Accreditation Manager

Brian Austerman, Deputy Chief

Arby Todd, Deputy Chief

Mike Weissenbach, Assistant Chief

Kris Presnell, Assistant Chief

Mike Mohrman, Assistant Chief

Kevin McCaw, Assistant Chief

Jim Eden, Assistant Chief

Wes Blanscet, Assistant Chief

David Tucker, Communications Supervisor

Bryce Buchanan, Captain, IAFF Local 2195 President

Michael Liebig, Engineer

Tyler Hartman, Engineer

Jeremy Blunt, Engineer

Becky Carson, Lead Communications Specialist

Eric Thompson, Firefighter

Carla Krska, Lead Communications Specialist

Joshua Rife, Firefighter

Laura Kreglo, Firefighter

Laura DeCourcy, Administrative Assistant

Cynthia Stacks, Applications Administrator, ITS

Liz Wilkerson, Senior GIS Technician, ITS

Carson Stone, GIS Technician, ITS

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Figure

Figure

Figure

Figure

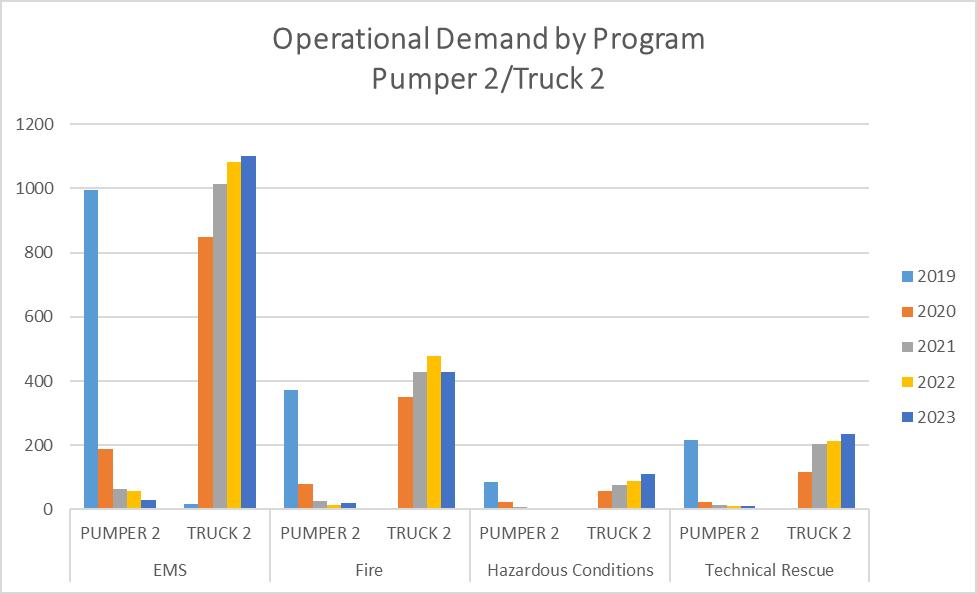

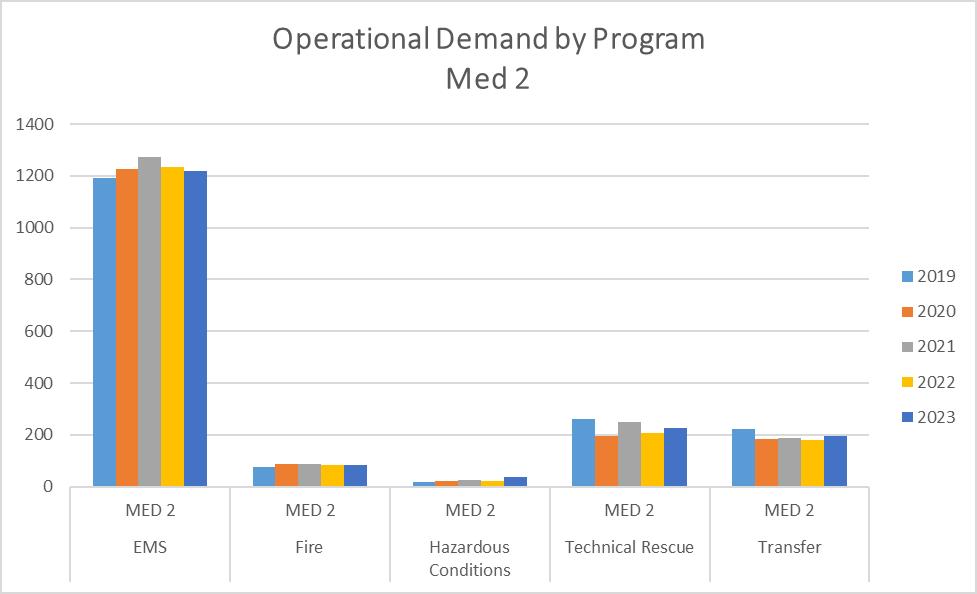

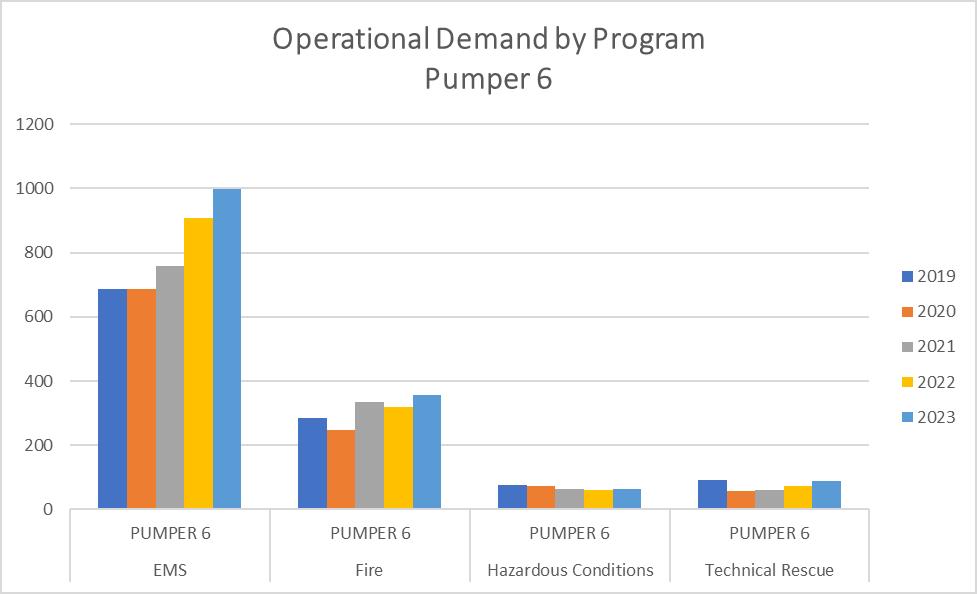

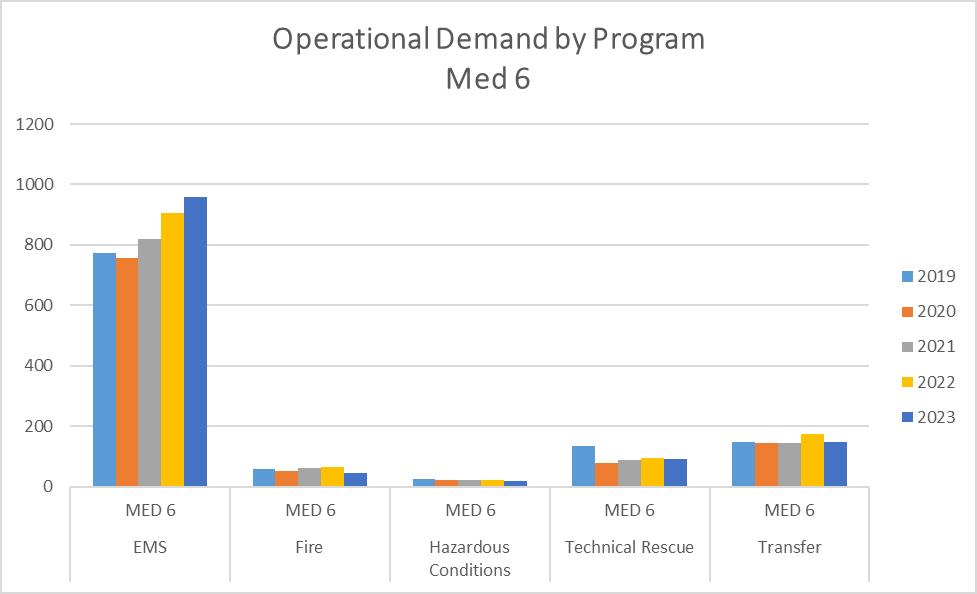

Figure 40: Operational Demand Frontline Apparatus (2019-2023) ......................................................................................

Every community is different, and each community has its unique hazards, risks, and vulnerabilities and its unique capabilities to respond to those risks. As part of a community-focused continuous improvement process, the Lee’s Summit Fire Department (LSFD) has completed a Community Risk Assessment (CRA) and Standards of Cover (SOC) for the City of Lee's Summit and contract service areas.

The information and data collected have identified the risks to the community and the resources available to mitigate them and describes the current response performance capabilities of the Lee’s Summit Fire Department. The accreditation model established by the Commission on Fire Accreditation International (CFAI) requires that these risk and deployment assessments be reviewed annually as part of an every five-year peer review to ensure that hazards and vulnerabilities are constantly assessed and analyzed to provide the highest level of protection for the community. This document provides an overview of Lee’s Summit and contract service areas, the fire department structure and services, risk assessment of the community, current deployment, and performance data. It also identifies critical tasking for effective response force determination and includes a plan to maintain and improve these response capabilities in the future.

Lee’s Summit governance model comprises a mayor and eight city council members, with two council members representing each of the four council districts. Lee's Summit is a charter form of government, setting the terms for council members to four years in length. Each of the four districts is represented by two council members whose terms are staggered and expire every four years. The mayor also serves a four-year term and is elected at-large. All elected offices are subject to a two-term consecutive limit. The city manager serves as the city’s executive officer, overseeing all city departments directly or indirectly. Lee’s Summit Fire Department falls under the organizational system of the city as a self-regulating department, creating internal policies and regulations while adhering to the overhead policies and direction of the governing body.

On October 12, 1971, the City of Lee’s Summit Board of Aldermen ordained Chapter 16 ½ within the amended Ordinance 1317, thereby “providing for a modern, efficient fire department.” Once approved by the mayor, the fire department became legally established within the code of ordinances for the City of Lee’s Summit. Contracted fire department response services are also provided for the City of Greenwood and Unity Village, Missouri. Currently, the Lee’s Summit Fire Department has several mutual aid agreements with other agencies, but no automatic aid agreements.

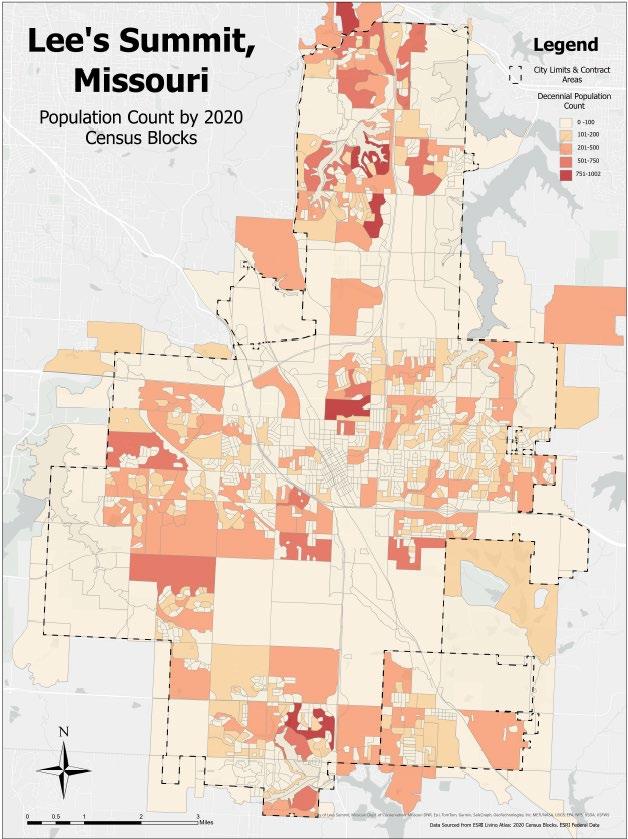

Lee’s Summit is in the southeast portion of the Kansas City metropolitan area. The city was incorporated in 1865 and originally included the 70 acres of land (0.109 square miles) that surrounded the railroad depot. The city has grown steadily for 158 years and has annexed land 28 different times. Several land annexations included neighborhoods extending out of the southern border of Jackson County into Cass County.

Today, Lee’s Summit has grown to be the sixth largest city in Missouri, with a current population of 106,031 within a 65.87 square mile jurisdictional boundary. In recent years, the city has experienced accelerated development and investment throughout the city in all sectors, including commercial, industrial, and residential. At the same time, the city government has maintained a strong commitment to quality services for the citizens of Lee’s Summit. The city has the unique distinction of being one of only a few cities in the nation to hold five national-level accreditations in its organization: Parks and Recreation, Public Works, Water Utilities, Police, and Fire. This commitment has not gone unnoticed; the city’s exceptional services and amenities have helped it receive regional and national recognition. In 2023, Lee’s Summit earned the #14 spot on Fortune’s “50 Best Places to Live for Families” and Livability’s “One of the Best Cities to Live in America”. Lee’s Summit has also been named a “Community for All Ages” and a “Walk and Bicycle Friendly Community.” The city has also received the “SolSmart Gold” designation for advancing solar energy growth.

Two regional hospitals call Lee’s Summit home: Saint Luke’s East and Lee’s Summit Medical Center. These healthcare facilities provide the needs of the community with state-of-the-art services, and they continue to expand to meet the growing demand for service in the community.

The Lee’s Summit R-7 school district provides education to the children of Lee’s Summit from elementary through high school. The approximate enrollment for pre-K through 12th grade in 2023-24 was 17,820 students and a support staff of 2,700 team members, with more than 1,300 being teachers. The district also added an additional middle school in the Fall of 2022 located on SE Bailey Road and SE Ranson Road. The school district is currently 117 square miles, including 18 elementary schools, four middle schools, three high schools, an alternative secondary school, a secondary technology academy, an early education center, and a special-education day-treatment center.

The northern portion of the city is home to three schools in the Blue Springs School District. Delta Woods Middle School has a staff of 90 teachers and administrators and educates over 850 seventh and eighth-grade students coming from Lee’s Summit, Independence, and Blue Springs. Voy Spears Elementary and Chapel Lakes Elementary schools each have a staff of 70 teachers and administrators, and each educates over 500 students from first grade through sixth grade. These schools, their staff, and students also fall under the protection of the Lee’s Summit Fire Department due to their location within the jurisdictional boundary of the city.

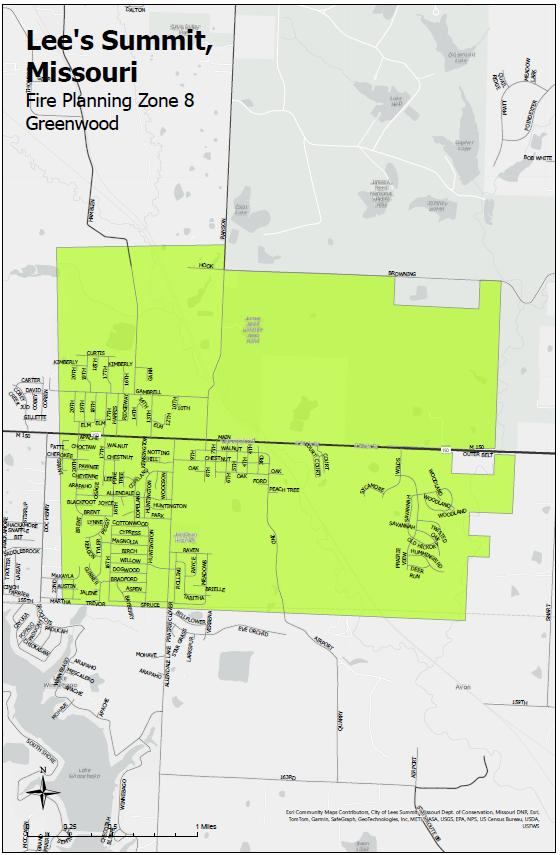

The Lee's Summit Fire Department also serves the communities of Unity Village, Missouri, and Greenwood, Missouri. Unity Village is a 1.52 square mile village located northwest of Colbern and Lee's Summit Roads. Unity Village has a population of 66 residents and is the headquarters for the Unity World Church. The centerpiece of Unity Village is a campus with historic buildings. The tower and an office building were used for the Silent Unity Prayer Ministry, which opened in 1929 and is currently on the National Register of Historic Places. Greenwood, Missouri, is a 5.23 square mile community with a population of 6,021 per the 2020 census. Greenwood is on the southeast corner of Lee's Summit.

The city’s primary operating fund is called the General Fund, which is shared by nine city departments. The majority of general fund revenues come from property, sales, and franchise taxes. All fire department revenue received from contract services or ambulance billing is remitted to the city’s general fund. The department is funded through the general fund and through a Use Tax passed in June 2020 and a Public Safety Sales Tax (PSST). The PSST was approved by the citizens in Spring of 2022, with collections and revenues beginning in January of 2023. The PSST also provides additional funding to support Lee’s Summit Police Department. Both agencies coordinate the use of those available funds as per a plan each defines to enhance staffing and equipment for each respective department. The PSST budget is adopted alongside the general fund budget as part of the overall budget approval process.

The fire department’s budget is developed by input from staff members who look at existing and possible new programs and services, staffing requirements, and past fiscal year trends. Once the department’s budget is developed, the fire chief, with the help of staff, presents it to the city manager. The city manager, in turn, presents the general fund budget to the Finance and Budget Committee of the City Council. Once the committee members evaluate and recommend passage of the total budget, it is then introduced to the full council for passage. A balanced annual budget is a requirement per the City’s Charter. The city’s annual budget is formulated by revenue predictions based on actuarial and predictive trends.

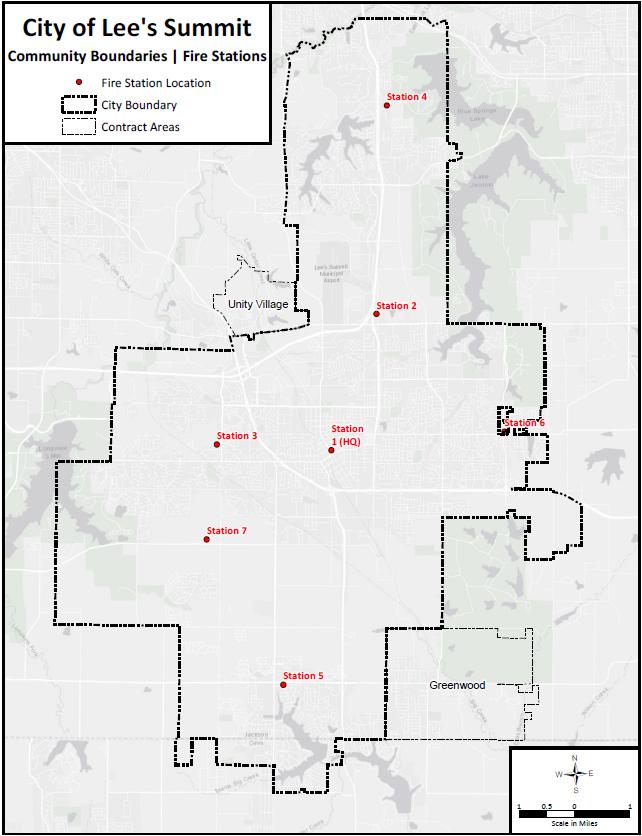

The fire department’s jurisdictional boundaries are created by the City of Lee’s Summit’s geographical boundaries and the boundaries of its contract agencies, Unity Village and Greenwood, Missouri. Unity Village comprises a total of 1.52 square miles, and Greenwood comprises 5.23 square miles of land, which increases the total response area for the LSFD to 72.62 square miles. There are five neighboring fire departments or fire protection services that border the coverage areas and have mutual aid agreements with the LSFD: Kansas City Fire Department to the west, South Metro Fire Protection District to the south, Southern Jackson County Fire Protection District to the east, Central Jackson County Fire Protection District to the northeast, and Independence Fire Department to the north.

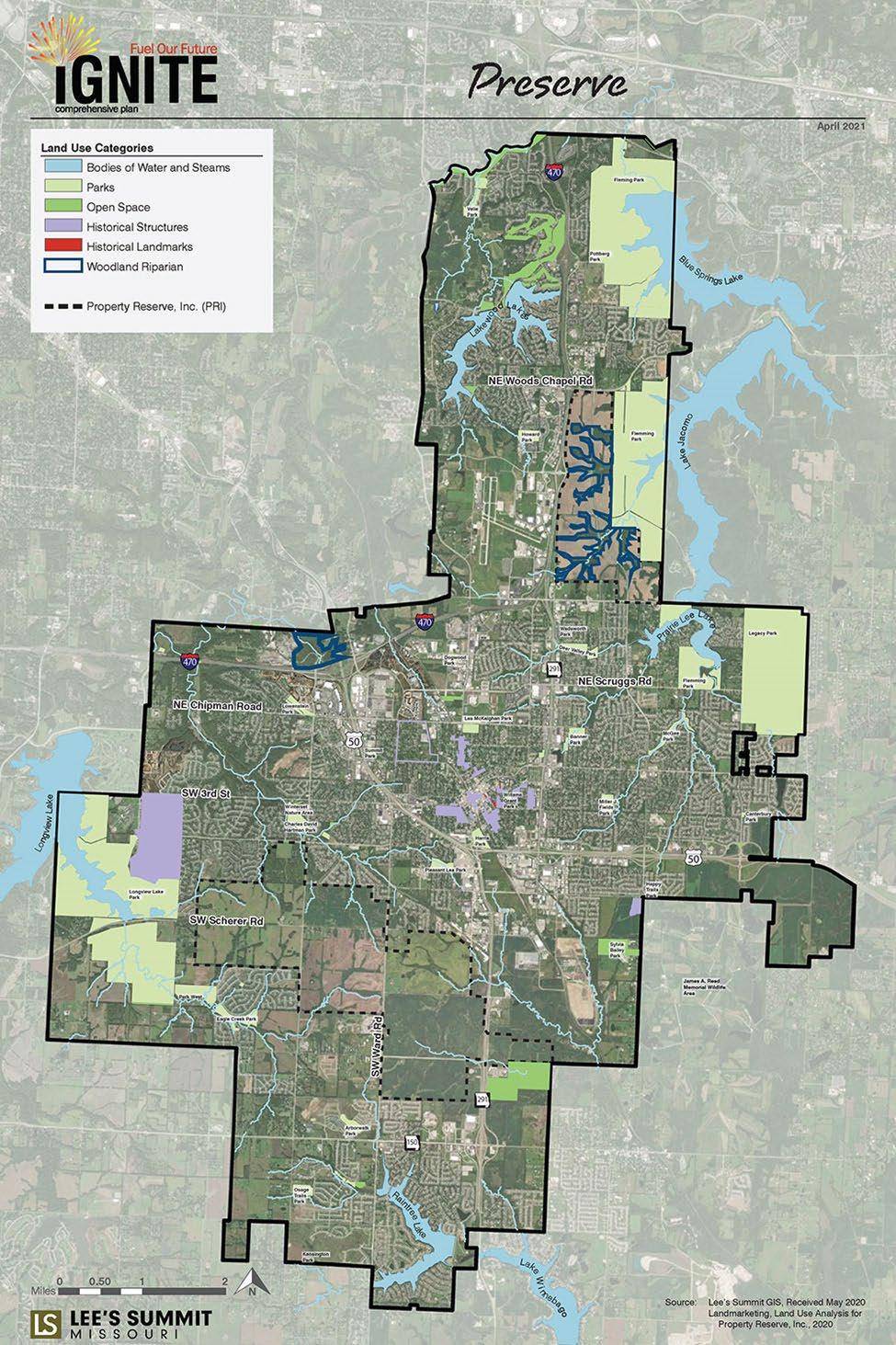

The Ignite Comprehensive Plan was recently completed and is the City’s master plan of all plans. It articulates a series of goals, policies, actions, and standards to guide the community’s physical development and programs over a 15 to 20-year timeframe. It is a dynamic document as it is reviewed annually and presented to City officials along with any recommended policy changes. A more complete update to the plan will be produced every five years. The document serves as the basis for economic development, quality residential growth and general improvements for the protection of the quality of life for Lee's Summit residents and businesses, including public safety.

The Ignite Comprehensive Plan, as well as the other plans developed by the city, should fully integrate and support the vision, goals, and objectives of the comprehensive plan. A few of those recommended include:

Capital Improvement Plan, Greenway Master Plan, Thoroughfare Master Plan, Community for All Ages, Water Master Plan, Wastewater Master Plan, Stormwater Management Plan, 2004 Downtown Master Plan, Regional Parking Structures in Downtown Study, Historic Preservation Plan, Cultural Resources Survey, and Bicycle Transportation Plan

The fire department is actively involved in the City’s development process to ensure the current and future public safety needs are being addressed.

Five Big Ideas were developed to help define the overall direction of the Ignite Comprehensive Plan. They are:

1. Preserve natural resources, open space, and recreational, cultural, and historic resources.

2. Maintain thriving, quality neighborhoods that connect the diversity of residents throughout the community.

3. Concentrate multi-family and commercial development in five special and unique Activity Centers.

4. Grow the tax base and good-paying jobs.

5. Sustain and enhance City services, public facilities, and infrastructure to protect a high quality of life.

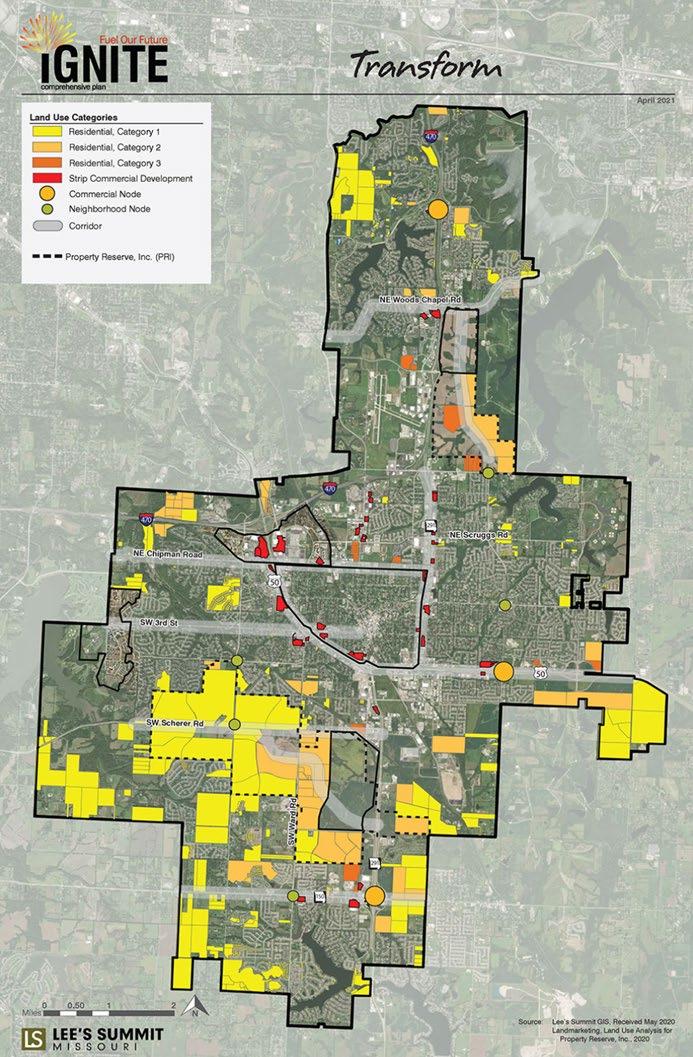

The Ignite Comprehensive Plan approach to land use falls within four categories: Preserve, Enhance, Strengthen, and Transform.

4: Ignite Comprehensive Plan - Preserve

PRESERVE Lee's Summit's high-value resources for enjoyment by future generations. The map includes parks and open spaces, natural wooded areas, streams, lakes and rivers, historic places, and cultural resources.

5: Ignite Comprehensive Plan - Enhance

ENHANCE existing single-family neighborhoods with public infrastructure investment, connectivity improvements, and flexibility to keep the character but meet changes in market demand over the next 20 years. The map includes existing residential neighborhoods.

6: Ignite Comprehensive Plan - Strengthen

STRENGTHEN access, appearance, activity, connectivity, and resiliency of community anchors and downtown. The map includes Downtown Lee’s Summit, existing commercial nodes, existing neighborhood centers, Lee’s Summit Municipal Airport, industrial, community anchors, civic facilities, emergency service facilities, and primary/secondary education facilities.

TRANSFORM and revitalize areas of the community using public improvements, incentives, and community partnerships to make them more resilient and adaptive to future change. The map includes activity centers, major corridors, new commercial nodes, Lee’s Summit Municipal Airport, existing strip commercial, community anchors, new neighborhood centers, and new residential.

The transportation network for the City of Lee’s Summit, City of Greenwood, and Unity Village are comprised of streets/highways, runways, and railways. Lee’s Summit is intersected by six highway corridors, including I-470, US 40, US 50, M-291, M-150, and M-350. These corridors are used daily by commuters to reach destinations throughout the Kansas City metropolitan region for work and travel. These same corridors are also utilized daily by semi-tractor trailers transporting various quantities of hazardous materials throughout the region and beyond.

The city of Lee’s Summit currently boasts 17 miles of park trails, 39 miles of shared/mixed-use paths, and 36 miles of bike lanes/share-the-road lanes. Unity Village and Greenwood also have trail systems.

and Future

On May 11, 2018, a ribbon-cutting ceremony was held for the completion of a new interchange at US 50 and Route 291 South. Changing the old 291 overpasses into a diverging diamond design has eased traffic congestion and allows for higher traffic volumes along the heavily traveled route. In addition, the interchange is expected to increase

economic growth and expansion south of US 50. It is estimated that by the end of 2025, a similar project will be started at the east junction of the interchange of US 50 and Route 291 North.

Ingress and egress from the department service area are primarily served by maintained federal, state, and city roadways. Traffic flow and accessibility are often affected by weather conditions and rush hour traffic volume.

Lee’s Summit Municipal Airport (LXT) is located in the north-central sector of the city. The regional airport is a nontowered facility with no on-site air traffic control and is primarily utilized by smaller aircraft. As a result, the airport is not currently required to have onsite fire and rescue support. This will soon change as the airport is in the midst of an expansion project that will allow for larger aircraft. Current runways are positioned in north-south/east-west directions. Runway 18-36 is 5,501 feet long and 100 feet wide, while runway 11-29 is 4,000 feet long and 75 feet wide. The FAA has rated the runway at a 60,000-pound capacity. However, with prior permission, they can take up to a 100,000-pound aircraft. There is a 40,000-square-foot heated and enclosed hanger available, and construction of a second hanger was approved in March 2024. According to airport administrative staff, Lee’s Summit Municipal Airport experiences approximately 50,000 takeoffs/landings annually. Residential homes, businesses, and highways are located directly in the landing patterns of both runways.

Pacific in 1905. Several downtown streets were built along the northwest to the southeast direction of the track. Part of the city’s current name (Summit) is derived from the fact that the train depot is located along the highest elevation of the railway between Kansas City and St. Louis.

The line is utilized for both freight and passenger service. Freight trains ordinarily carry agricultural, automotive, chemicals, coal, industrial products, and intermodal. Amtrak provides passenger service twice daily for northbound and twice daily for southbound departures. According to Amtrak, 145,000 passengers traveled the Missouri River Runner service corridor from Kansas City to St. Louis in 2023.

Lee’s Summit had not experienced a derailment until the Spring of 2024. The derailment took place in a remote area of Unity Village. There have been train versus auto collisions at the four at-grade railroad crossing intersections in the area of service; three are cross-armed controlled, with one uncontrolled. There are business and residential corridors along the railway. Two of the four railroad crossing intersections in Lee’s Summit city limits are centrally located in the Historic Downtown Main Street core, where festivals and concerts are conducted annually. LSFD apparatus have a response option of utilizing unimpeded Second Street to avoid delays during railway crossing use and festivals in the downtown core. The two other railroad crossings are on less-traveled response routes but could pose delays encountering railway use.

The City of Lee’s Summit is currently served by two primary water purveyors: Lee’s Summit Water Utilities (LSWU) and Public Water and Sewer District #13 (PWSD13). The LSWU and PWSD13 provide reliable water throughout the city, except for several areas along the city borders that are served by the neighboring jurisdictions, such as the City of Independence, City of Kansas City, and Cass County Public Water District #3. LSWU receives its water from two suppliers, Kansas City and the City of Independence. LSWU has a system capacity of approximately 32.5 million gallons per day and maintains over 5,300 fire hydrants in its system. They have four pumping stations, nine water towers, and storage tanks. PWSD13 covers areas of the northeast central portions of the city and receives its water from the Tri-County Water Authority. PWSD13 has a storage capacity of one million gallons. The department serves two additional areas by contract. Those areas are Unity Village and the City of Greenwood, Missouri. Unity Village is served by its own water system and has a storage capacity of 100,000 gallons. Fire hydrants within Unity Village are supplied by both Unity Village and LSWU. The City of Greenwood is served by Public Water and Sewer District #12 (PWSD12) and Cass County Water District #6 (CWD6). PWSD12 receives its water from Kansas City and the Tri-County Water Authority. PWSD12 has a storage capacity of one million gallons. LSWU has emergency interconnects to supplement all purveyors in all areas of service, including contract service areas.

The city’s MS4 Stormwater Management Plan has identified 14 sub-watersheds within the city limits. Stormwater management is overseen by the city’s public works department, and the plan is updated annually.

The City of Lee’s Summit has an extensive natural gas infrastructure serving the community that is owned and operated by Spire Energy.

Evergy owns and operates the electrical power grid for the City of Lee’s Summit. The city has three electrical substations within its jurisdictional boundaries, located on Longview Road, Tudor Road, and Blackwell Road. From those substations, the power is distributed throughout the city by overhead and underground transmission lines.

The city uses zoning areas guided by the Ignite Comprehensive Plan and adopted zoning ordinances to define land uses (such as commercial, residential, and industrial) and where they can be located to determine land use. Currently, Lee’s Summit has a ratio of approximately 74.2% developed land, with 25.8% of land remaining undeveloped. In January 2019, it was announced that two large tracks of land are coming open for development within city limits that have, up to now, been untouched open spaces. The 4,100 acres are owned by Property Reserve Inc. (PRI), and planning has begun between city leaders and PRI towards the development of these land holdings in the near future.

Lee’s Summit has historically been considered a bedroom community, with people choosing to live here but work elsewhere. Specific to land use by types: 32.3% is dedicated to some residential living, and 6.3% is used for commercial, office, mixed-use, or industrial. The remaining 61.4% is made up of parkland, government holdings, right of ways, and undeveloped land. In recent years, there has been an increase in commercial building construction, which indicates that the city is transitioning from a bedroom community to one where people choose to live, work, raise families, and seek entertainment opportunities.

The city has adopted an Economic Development Incentive Policy supporting the Economic Development Vision outlined by the city council. This policy provides information on the type and availability of incentive programs as well as targeted economic development outcomes and geographic areas. The city is prepared to strategically and responsibly consider the use of incentive programs to meet the economic development goals and outcomes in support of this vision.

At an elevation of 1,040 feet, the City of Lee’s Summit is one of the highest points between St. Louis and Kansas City in the state. With this elevation come slight rolling hills as well as flat and low-lying areas. During periods of heavy rain, some of these low areas are prone to swift water and flooding. The city is home to four county lakes and two private lake communities. There are several creeks and ponds scattered throughout the city as well. In total, 2.7% of the city is covered by water.

Lee’s Summit is located southeast of the Kansas City Metro in northwestern Missouri. After 28 land annexations, Lee’s Summit currently consists of 65.87 miles, including 1,157 acres of water. Lee’s Summit is bordered by the Missouri cities of Independence to the north, Unity Village to the northwest, Kansas City to the west, Raymore to the southwest, Greenwood to the southeast, and primarily unincorporated areas to the east.

Located in the rolling hills of northwestern Missouri, Lee’s Summit is situated in the stable crustal platform of the midcontinent region. The region is tectonically stable, so earthquakes are rare. Interbedded limestone and shale are typical of the bedrock formation in Lee’s Summit, which provides a strong foundation for the building construction in the region. The subsurface rocks of the region are consolidated limestone, sandstone, and shale. The thick limestone beds of the region provide valuable resources for building materials like cut stone, crushed aggregate, and cement, much of which is mined in several large quarries surrounding Lee’s Summit. A former underground mined cave, which is now utilized for 1.5 million square feet of subterranean warehouse rental space, is in the northern part of the city.

The Missouri Department of Natural Resources has divided the state into three physiographic regions: Interior Plains – Central Lowlands, Interior Highlands – Ozark Plateau, and Atlantic Plain – Coastal Plain Lee’s Summit is in the Osage Plains within the Interior Plains – Central Lowlands region. What used to be woody vegetation and prairies in Lee’s Summit have developed into residential and business lands. Residential developments consist mostly of transplanted trees and lawn grass conducive to the region. It is not uncommon for residential neighborhoods to be located adjacent to agricultural farms and livestock properties. The undeveloped sections consist of approximately 17 miles of park trails, pockets of native trees, native grasslands, and agriculture. Large portions of Lee’s Summit are still

dedicated to farming due to fertile soil, predictable growing cycles, and climate zones. Approximately 242 acres are zoned for agricultural use. Also, Lee’s Summit has approximately 6,500 acres of land owned by Property Reserve Inc. (PRI) that are still used for agricultural purposes and are slated to be developed in the coming years.

Lee’s Summit, Missouri, is in the Midwest, which is classified as a humid continental climate according to the Koppen climate classification. Lee's Summit has a temperate climate that experiences all four seasons: the summers are hot and muggy; the winters are cold and windy, and there is year-round precipitation.

Table 1: Climate Data

Similar to much of the Midwest, Lee’s Summit is subject to extreme weather. Drought conditions are common during the summer, as well as periods of excessive heat and humidity. The Emergency Management Plan includes a collaborative agreement with Lee’s Summit Parks and Recreation and the Mid-Continent Library system to operate as “cooling centers” during excessive heat warnings. Winter precipitation is common in the area, with sleet, freezing rain, and snow or a combination of the three during a single event. Mainly during the spring, powerful thunderstorms and flash floods affect the area. In the past ten years, the city has been impacted by three tornados ranging in strength from EF0 to EF1 on the Enhanced Fujita scale.

The length of daylight varies greatly throughout the year in this area. The most daylight occurs on June 22 at 14:43 hours, compared to the shortest being on December 21 at 09:16 hours.

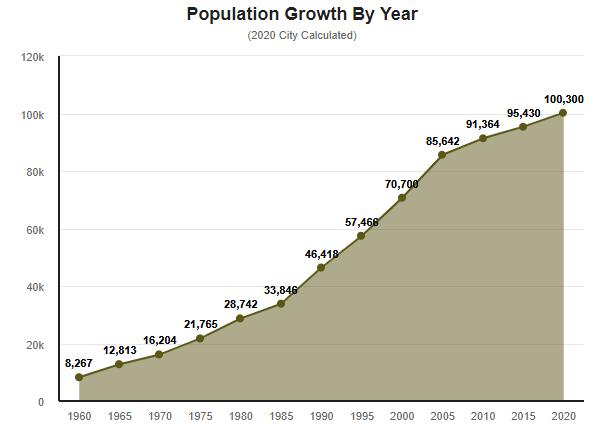

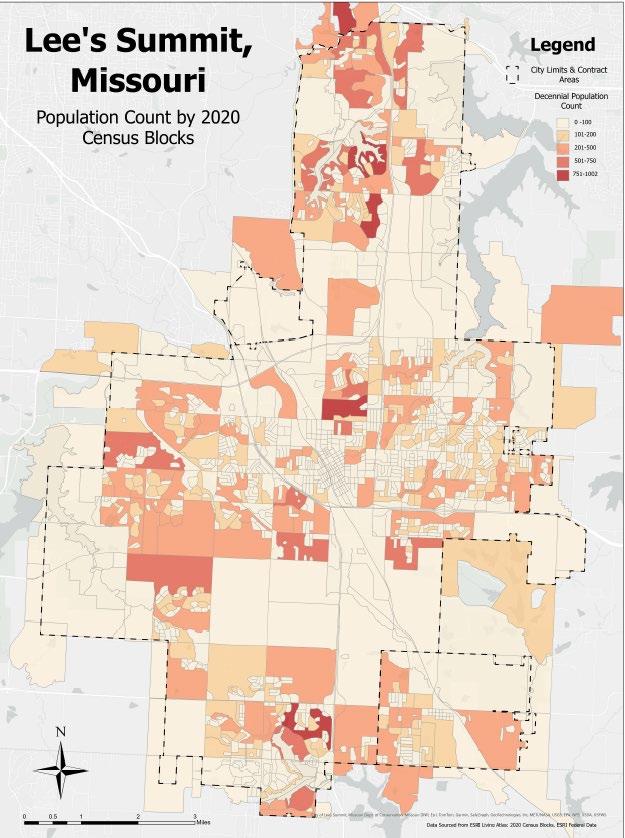

In 2023, the population of Lee’s Summit was 106,031; this is a population increase of 7.67% since 2019. This ranks Lee’s Summit as the sixth largest city in the state of Missouri. The City of Lee’s Summit stretches over 65.87 square miles, making its population density 1,609 people per square mile. The city, divided into four distinct Council districts, has different characteristics in population demographics and each is represented by two elected officials.

Like many urban communities across the United States, Lee’s Summit began to experience its transformation from a rural, mostly agrarian community to an urban community in the decades after the Second World War. As the city grew, its population nearly doubled every decade. In 1980, the population was approximately 28,000. By 1990, the population had reached 46,500. From 1990 to 2000, the city experienced a 53% increase in population and another 29% increase from 2000 to 2010. Today, the population is estimated at 106,031.

Taking a closer look at the data indicates the City of Lee’s Summit is 51.32% female and 48.68% male. The city has a largely diversified age population. The smallest age groups are those 80 years of age and older, with the largest population in the city being those aged 10 to 14. This demographic distribution provides valuable information related to risk assessments and emergency service trends for the department and the elected officials relative to planning.

Lee’s Summit continues to diversify its population. The city can be broken down as follows: 76.6% white, 8.73% black, 2.33% Asian, 2.33% Hispanic/Latino, 5.30% Native Hawaiian, 0.13% American Indian/Alaska Native, 0.22% some other race category, 0.37% and 5.59% were two or more races. Comparatively, this signifies a small change since 2010. Some of the noticeable differences are that the white population has decreased by 9.56%, and all other demographics have increased. If Lee’s Summit continues to follow the trends of the rest of the nation, in the next 20 years, the population of Lee’s Summit will be vastly different and continue to diversify.

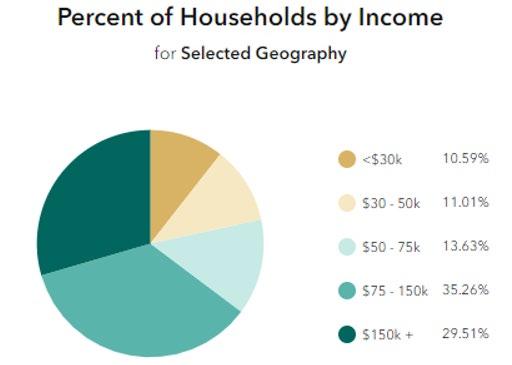

Lee’s Summit has one of the higher median household incomes in the Mid-America Regional Council (MARC) region. Lee’s Summit has an average median household income of $102,695 when compared to the MARC regional average of $70,097. Not only does the city have a higher median household income, but it also has a lower housing vacancy rate of 4.72% versus the MARC vacant housing rate of 7.21%. Lee’s Summit has a higher percentage of homeowners at 72.76% versus 22.52% who rent. All these factors are positive correlators when measured against community risk for Lee’s Summit.

The Lee’s Summit Fire Department (LSFD) was established by the city founders in 1875 as a volunteer fire department. The equipment, a four-person pump, was pulled by firefighters or horses and was housed in City Hall beside the jail. This initiated pumping operations and formed a “bucket brigade” to combat fires from strategically placed cisterns in the downtown district.

In 1885, a downtown fire devastated the largest part of the Lee’s Summit’s business district, which prompted the city to invest in a larger, six-man pump for superior firefighting capabilities. In 1909, another downtown fire erupted. Unfortunately, the city-owned pump failed, leaving firefighters unable to halt the fire’s spread. Kansas City Fire eventually extinguished it after three and a half hours.

The evolution of the LSFD milestones continued with acquiring its first gasoline internal combustion fire engine in 1924 and then purchasing a 1951 Howe Fire Truck. In marking significant growth, in 1960, the department transitioned from a volunteer force to a paid one.

Further expansions, station openings, and equipment upgrades followed. This included the integration of Emergency Medical Services (EMS) in 1971, pioneering a modern concept adopted by many departments.

The department has experienced a wide range of events, from a tragic loss in 1999 to achieving accreditation and reaccreditation. In recent years, LSFD has seen extensive growth and modernization with new facilities and equipment acquisitions to enhance capabilities.

Today, as the department plans new facilities and continues to grow, it stands as a testament to its dedication to serving and protecting the community. Amidst challenges and milestones, the department remains committed to its mission: The Lee’s Summit Fire Department is dedicated to serving its community through prevention, preparedness, and response with PRIDE. The values of the Lee’s Summit Fire Department are Professionalism, Respect, Integrity, Duty, and Excellence.

The legal boundary of the service area for the department is contained within the jurisdictional city limits of the city of Lee’s Summit as established by city ordinance, as well as the contractual legal obligation to provide all hazard response to the cities of Unity Village and Greenwood, Missouri. The department is under the Western Missouri Fire Chiefs Association Mutual Aid agreements.

Map 13: Community Boundaries and Fire Stations

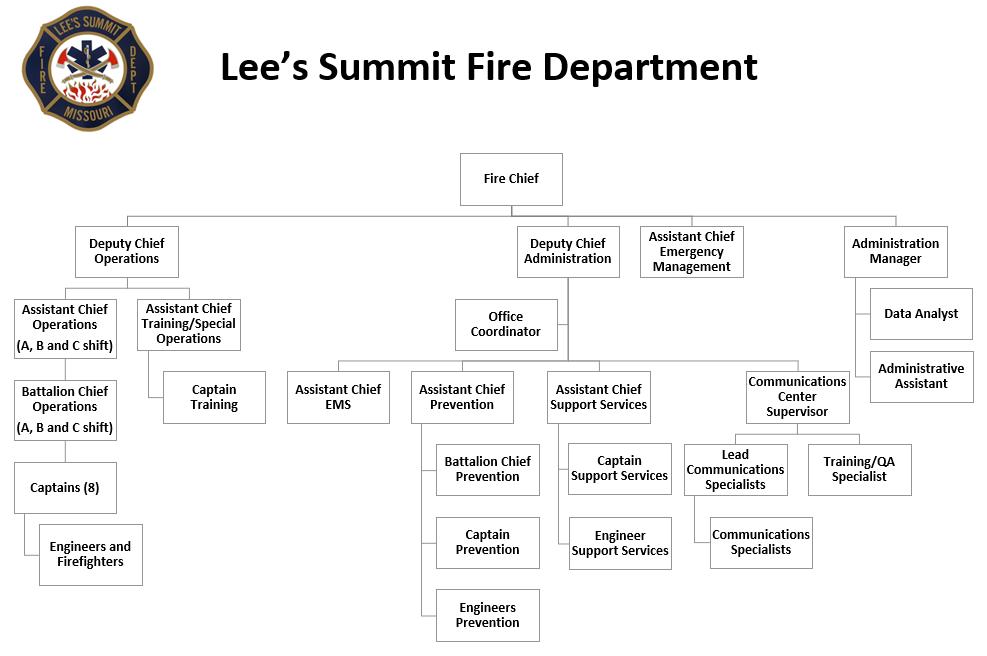

Figure 9: Organizational Chart

The department consists of eight divisions: Administration, Emergency Services (Operations), Training, EMS, Emergency Management, Communications Center, Support Services and Fire Prevention. The fire department is overseen by the fire chief.

The Administration Division, overseen by a deputy chief, is comprised of an administration manager, an administrative assistant, and an office coordinator to fulfill the administrative functions of the department. The approved department budget for FY25 includes an expansion position for a data analyst. Project management, budget formulation, record retention, data analysis, and accreditation are the responsibilities of this division.

The Emergency Services (Operations) Division is overseen by a deputy chief with an assistant chief and battalion chief for each shift. Fire station operations have been structured on a three-shift (A, B, and C) system, with a shift change at 0800. Each shift works 48 hours of continuous duty followed by 96 hours off.

The department staffs seven fire stations and 15 frontline emergency response apparatus, with all fire suppression apparatus overseen by a company officer at the fire captain or acting-captain rank. Department-wide operational staffing consists of 24 fire captains and 126 engineers and firefighters. The operations division is responsible for emergency medical services, fire suppression, rescue, and mitigation of both natural and human-caused disasters. Operations personnel also provide a wide range of services to the community through business inspections, public education, and station and apparatus tours. All members of operations have been trained to, at minimum, the awareness and operations level for hazardous materials and technical rescue.

The Training Division, overseen by an assistant chief and captain, provides initial and in-service training in all nonEMS-related areas of service provided by the department. The training division is supported by department members with Fire Instructor I certifications who act as recruit academy drill masters and apparatus certification instructors.

The EMS Division, overseen by an assistant chief, provides initial and in-service training in all EMS-related areas of service and coordinates all facets of EMS service within the department. This division is also supported by members of the department to deliver training to personnel and a contracted Medical Director. Additional annual training required for Advanced Life Support (ALS) and Basic Life Support (BLS) recertification is also performed by the division.

The Emergency Management Division, overseen by an assistant chief, coordinates the daily activities of emergency response for the department as well as the city as a whole. The fire chief serves as the City’s Emergency Management Director. This division is also involved with regional committees and coordination of Statewide Region A deployments.

The Communications Center is overseen by a communications supervisor, with 16 communications specialists working 12-hour shifts. The Communications Center has four lead communications specialists who have a different level of responsibility than a communications specialist. The approved department budget for FY25 includes an expansion position for a training/quality assurance specialist and two additional communications specialist positions. The center provides dispatching services to four contract agencies in addition to Lee’s Summit and is in fire headquarters.

The Support Services Division, overseen by an assistant chief, has a captain and fire engineer. Facility construction, facility repair, station supply delivery and apparatus procurement, and maintenance are the responsibility of the members of this division.

The Fire Prevention Division, overseen by an assistant chief, has a battalion chief, a captain, and three engineers (working 24-hour shifts) providing support. Community risk reduction coordination is the responsibility of the division, including plan review, business and sprinkler inspections, public education, and station tours.

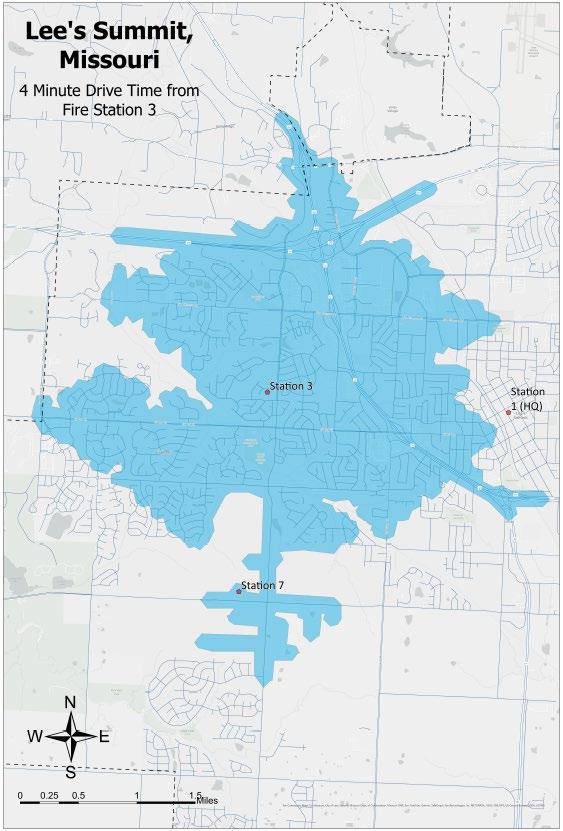

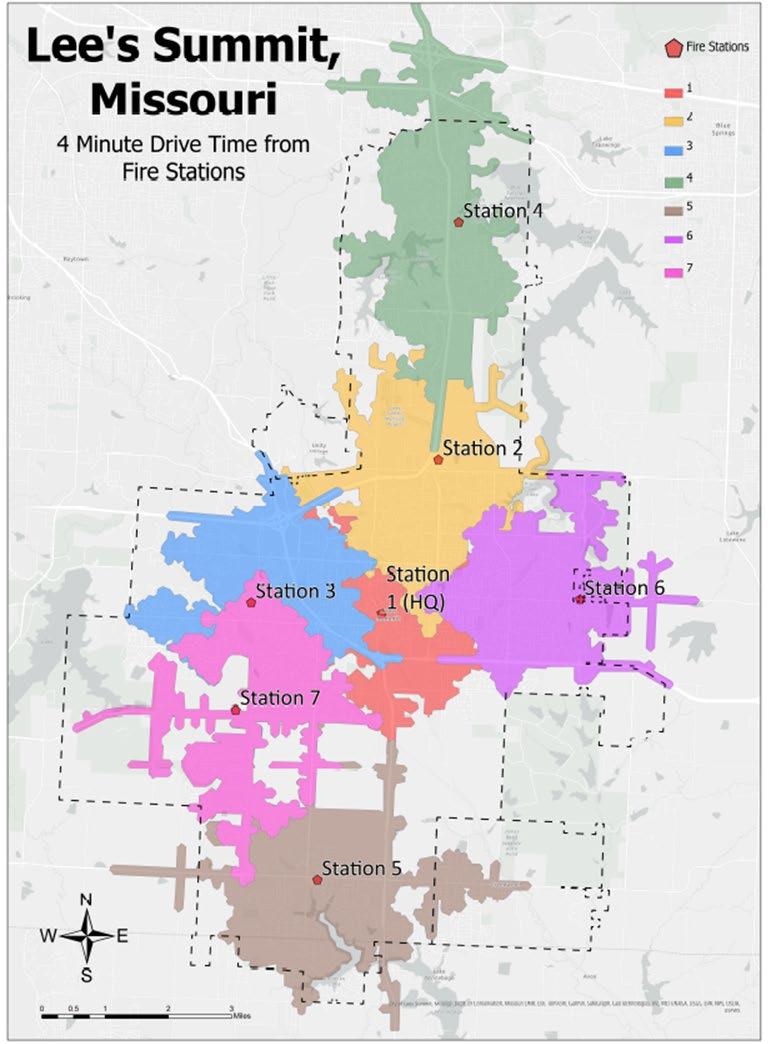

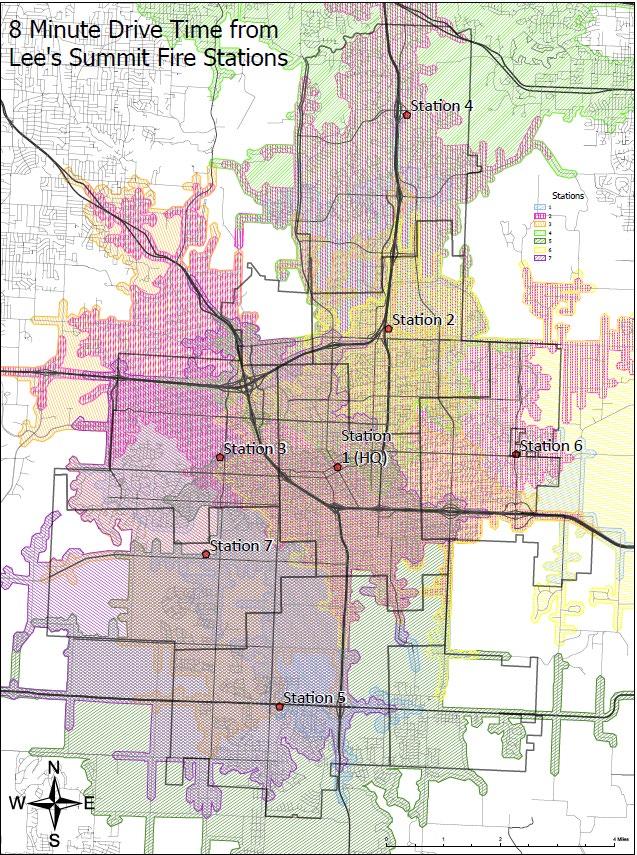

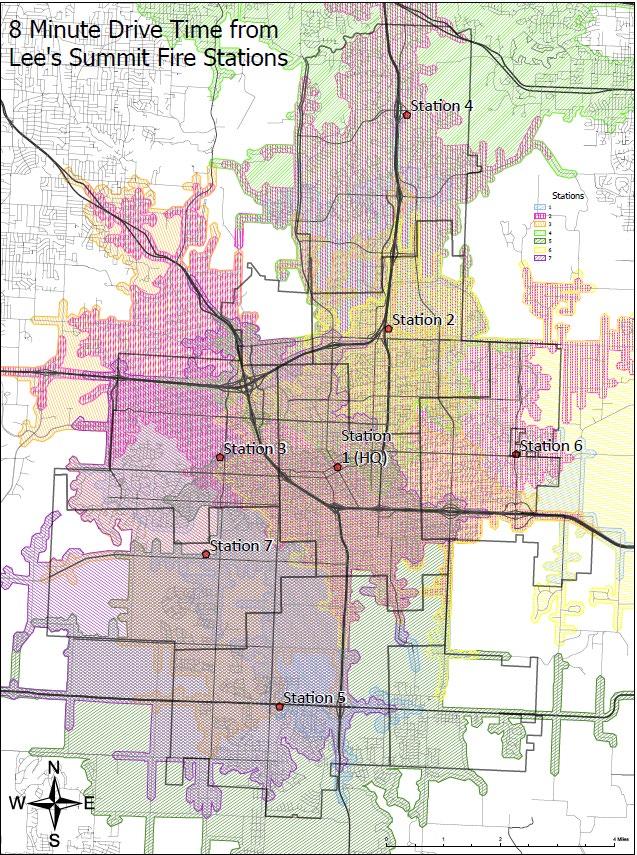

There are currently seven fire stations strategically located within the city which are also utilized for primary response to Greenwood and Unity Village through contractual agreements. Deployed from the seven stations are five pumpers, three ladder trucks, and seven med units, which are all staffed 24 hours a day. All frontline apparatus is ALS-equipped, and all med units are ALS-staffed each day. In 2019, automatic vehicle location (AVL) was implemented, and apparatus are assigned to incidents based upon closest unit response (CUR). Analyzing data, such as total response time and effective response force, based on CUR and typical response areas for each station will aid in future decisionmaking as it pertains to future station/apparatus additions, apparatus placement, and staffing.

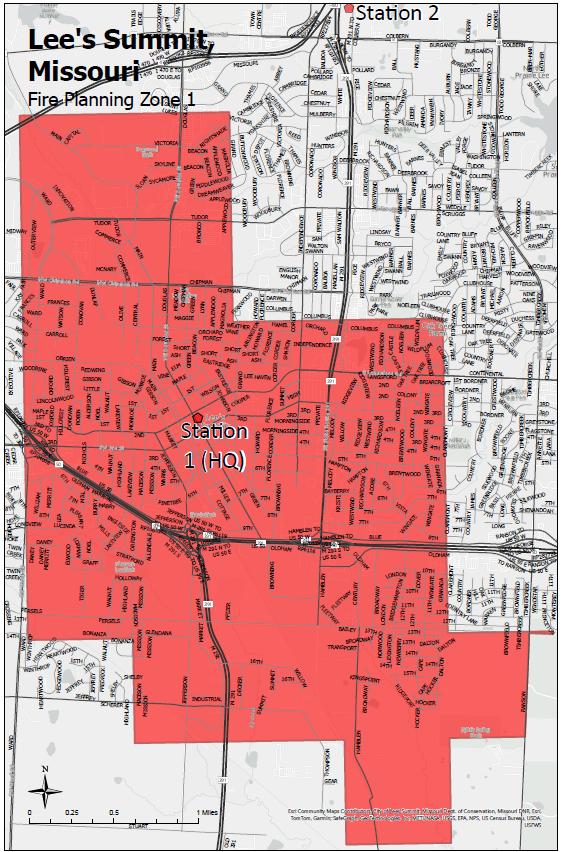

Fire Headquarters (Station 1) is located at 207 SE Douglas Street and was dedicated in October 1975. Pumper 1, Med 1, and the on-duty prevention engineer deploy from this station. Boat 1 is also located here and is cross-staffed as needed. The department’s administration, fire prevention, and communications center, and multiple reserve apparatus are also housed at this station. Fire Headquarters is staffed by a minimum of five personnel.

This district is in the heart of downtown Lee’s Summit. This diverse district consists of a historical downtown, elementary and high schools, historic residential housing, high-density apartments, a passenger, and freight railroad that bisects downtown, commercial shops, and industrial areas and is bordered by three highways.

During 2024, work began on the construction planning for building a new Station 1 and a new Joint Operations Center. The Joint Operations Center facility will house both the Fire and Police Communications Centers, Fire administration staff, and additional city staff.

Station 2 is located at 2000 NE Rice Road and was dedicated in July 2011. Truck 2 (a 100-foot platform ladder truck), Med 2, and an Operations Battalion Chief all deploy from this station. Station 2 is staffed by a minimum of six personnel.

This district is in the northern portion of the city with elementary and middle schools, lakes and woodland areas, residential and senior living housing, an airport, and two highways located near commercial and industrial areas. District 2 also protects a contract city with a large religious organization campus called Unity Village.

Station 3 is located at 2023 NW Shamrock Avenue and was dedicated in August of 2020. It houses Pumper 3, Med 3, Truck 3 (a 100-foot platform ladder truck), and an Operations Assistant Chief. Squad 1 is housed at this station and is cross-staffed as needed. Station 3 is staffed by a minimum of nine personnel.

This district is in the city’s core on the western boundary. It consists of a 300-acre senior living complex, elementary and middle school, singlefamily residential, high-density apartments, a large commercial district, and two highways.

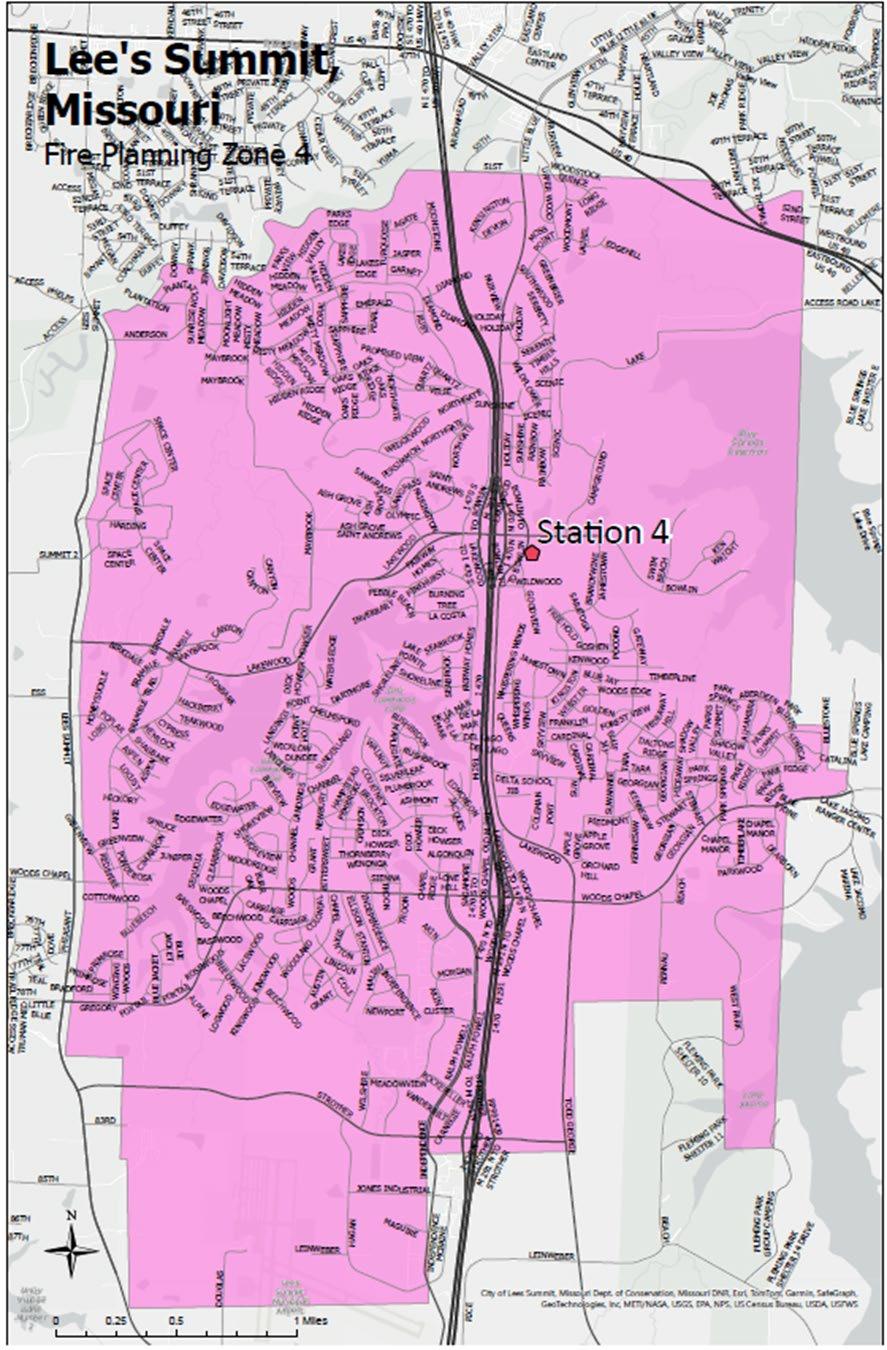

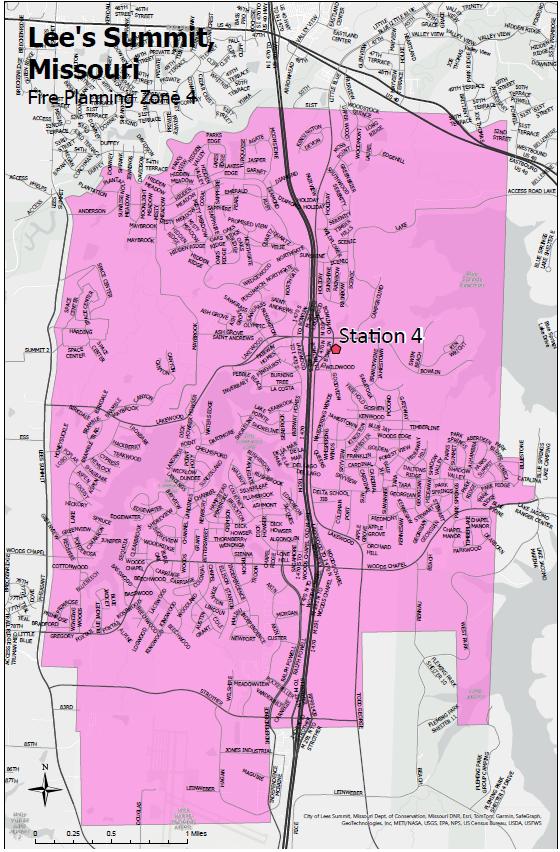

Station 4 is located at 5031 NE Lakewood Way and was dedicated in April of 2024. Pumper 4 and Med 4 deploy from this station. Grass 4, a cross-staffed vehicle, is also located here. Squad 4 is an unstaffed asset that is housed inside the subterranean warehouse space (Space Center) located in that district. Station 4 is staffed by a minimum of five personnel.

This district is on the northern boundary of Lee’s Summit. It protects a large senior living complex, single-family residential housing, several large lakes, elementary, middle, and high schools, the airport, a 1.5 million square foot subterranean complex, and a major highway.

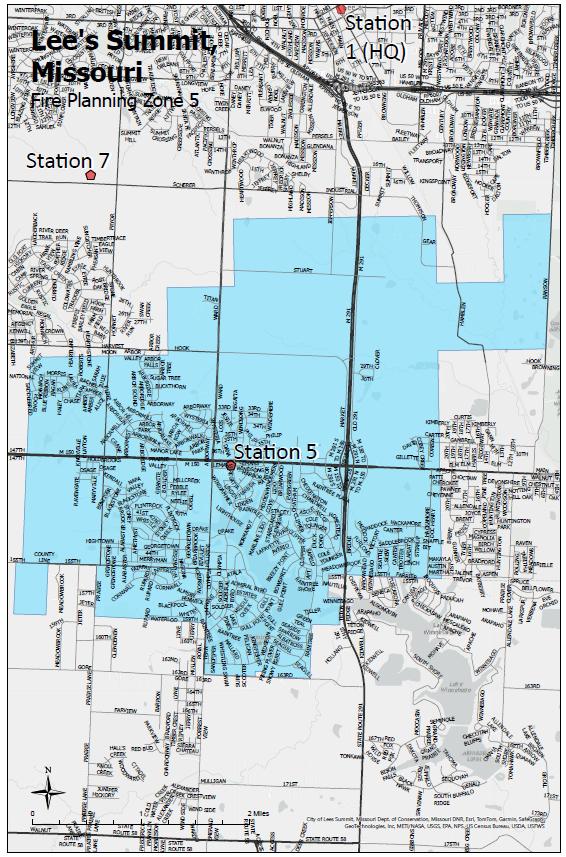

Station 5 is located at 801 SW M 150 Highway and was dedicated in March of 2024. Pumper 5 and Med 5 deploy out of this station. Grass 5, a cross-staffed vehicle, is also located here. A second cross-staffed boat is on order and will deploy from this station. Station 5 is staffed by a minimum of five personnel.

This district protects single-family residential and high-density apartments, commercial centers, lakes, elementary, middle, and high schools, as well as two highways and the contract area of Greenwood.

Station 6 is located at 101 NE Blackwell Road and was dedicated in April 1998. Pumper 6 and Med 6 deploy out of this station. Station 6 is staffed by a minimum of five personnel.

This district is located on the eastern boundary of Lee’s Summit. It protects single-family residential, an elementary school, a senior living complex, lakes, and a large city park system, as well as a highway.

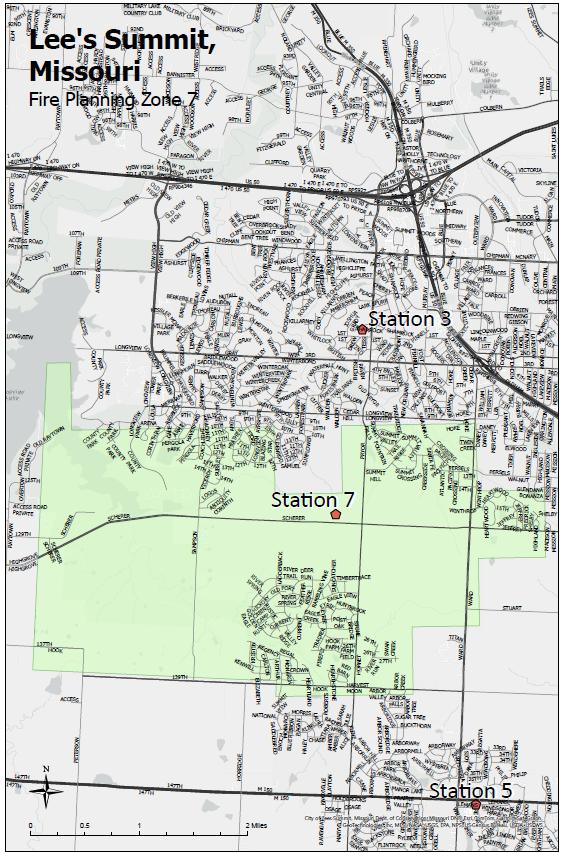

Station 7 is located at 2150 SW Scherer Road and was dedicated in March of 2007. Truck 7 (a 107-foot straight stick ladder truck) and Med 7 deploy from this station. Station 7 is staffed by a minimum of five personnel. The Department’s Training Division is located at Station 7. The station includes a three-story training facility for practical training sessions that encompass all service delivery areas of the department. In 2024 the addition of a Class A and Class B burn facility was built on the grounds of Station 7. This has many gas training props such as a vehicle, Cessna airplane, and propane tank. The tower includes a vertical ventilation prop, which allows the angle of the roof to be changed.

This district is located on the western boundary of Lee’s Summit and protects single-family residential, an elementary school, and a large amount of agricultural property.

The department has acquired land acquisition and design funding for Station 8 The city began the initial process of identifying land for the purchase and construction of this additional station during this SOC cycle. Property has been purchased at a location near the airport, which would also include the addition of an aircraft firefighting apparatus. A program has been developed and implemented in 2023 to rotate apparatus to different response areas to keep mileage and hours of use in check. This practice will become even more important once the department receives the nine lease-to-own pumpers, which are anticipated to be delivered in the summer of 2025, in which the mileage and hours will be more scrutinized.

The LSFD responds to fire incidents within the city and the contract areas of Greenwood and Unity Village, Missouri, and provides mutual aid when requested. LSFD has seven fire stations, staffed 24 hours daily with a minimum of 40 personnel and a maximum of 52 personnel. Fire operations are managed by an assistant chief and a battalion chief assigned to each shift and overseen by an administrative deputy chief.

There are five frontline and two reserve pumpers, which carry 500 gallons of water and have a pumping capacity of 1,500 gallons per minute. There are two mid-mount 100-foot platform ladder trucks and one rear-mount 107-foot straight ladder truck, which all carry 300 gallons of water and have a pumping capacity of 1,250 gallons per minute.

Each fire company is equipped to meet or exceed the recommendations of ISO and NFPA 1901, standards for fire department apparatus equipment assemblies. Each pumper carries a minimum of 1000 feet of 4-inch supply line, 500 feet of pre-connected 1.75-inch fire hose, and 400 feet of pre-connected 2.5-inch fire hose. Each ladder truck carries a minimum of 600 feet of 4-inch supply line and 500 feet of pre-connected 1.75-inch fire hose. Additional accessory fire hose is carried in various lengths; 1-inch forestry line, 1.75-inch fire hose, 2.5-inch fire hose, and 4-inch supply line.

Each pumper and ladder truck carries four self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA). Each med unit carries two SCBAs. Each person assigned to the operations division is assigned a personal SCBA mask. Two additional SCBA masks with thermal imaging capability are assigned to each pumper and ladder truck. Each minimum staffing position has a personal thermal imaging camera (TIC) assigned to the SCBA. Each pumper, ladder truck, and med unit have air monitoring equipment and various hand tools.

Each pumper and ladder truck has a minimum staffing of three personnel and an optimal staffing of four personnel. Each med unit has a minimum staffing of two personnel which are utilized in the fire suppression framework on fire incidents. All personnel are trained or certified, at a minimum, to the Missouri Division of Fire Safety (IFSAC) certification of Firefighter I and II.

Stations 1, 3, 4, 5, and 6 house frontline pumpers, and Stations 2, 3, and 7 house frontline ladder trucks. All stations have a med unit. The department has reserve and specialized apparatus that are utilized for maintenance purposes of frontline apparatus or cross-staffed for incident-specific resources. Station 1 houses two reserve pumpers, two reserve med units, and a reserve operations chief vehicle. Station 3 houses the Squad, which is used for specialty or large incidents.

Stations 4 and 5 each house a type 7 apparatus for wildland fires. Each grass rig has booster reels, 250-gallon water tanks, and fire pumps with pre-piping on the front bumper for remote pumping operations. The grass rigs are crossstaffed with two on-duty personnel as needed or with overtime personnel during high-fire hazard days.

To address the target hazard of the subterranean space the department houses a John Deere UTV equipped with 200 feet of 2.5-inch attack line and 400 feet of 1.75-inch attack line for connections to the standpipe system. In addition, the UTV is equipped with four SCBAs, a gas-powered fan, and various hand tools. The UTV is staffed by personnel arriving to alarms at this target hazard.

The department has ordered two boats scheduled to be delivered in 2025. Each boat will have fire pumping capability. The department has also been granted funding and is beginning the process for an additional fire station near the airport, which will accommodate a piece of apparatus capable of fighting aircraft fires.

The LSFD is staffed and equipped to respond to any medical incident within the city and its contract areas and is capable of providing mutual aid when requested. LSFD also provides both emergency and non-emergency transfer services for Lee’s Summit Medical Center as well as Saint Luke’s East Hospital.

The department has seven ground transport ambulances that are identified as med units. One med unit is based at each of the seven stations throughout the city. In addition to the frontline med units, LSFD has two reserve med units that are currently housed at Station 1. The reserve med units can be staffed on an as-needed basis as additional resources as well as supplement the frontline units when maintenance is needed allowing the department to always have seven units in service.

The state of Missouri licenses Emergency Medical Technicians at both the basic level (EMT-B) and the Paramedic level (EMT-P). Each med unit is staffed with an EMT-B and EMT-P as minimum staffing. LSFD provides the opportunity for EMT-Bs to attend Paramedic school. All members have and maintain licensing at the EMT-B level as a minimum, and the department staffs a minimum of 16 paramedics per shift.

While state licensure is the minimum standard for either level, a number of members maintain certification through The National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians (NREMT). This agency has strict requirements for certification, as well as a shorter certification cycle than the state.

Three paramedic members have also begun training as community paramedics, a certification that focuses on nonacute care to prevent patients with chronic medical issues from numerous hospital visits. The community paramedic program has not been implemented yet within the department, but training is needed to help prepare staff to begin the process of adding to service delivery.

Staffing levels at each station ensure paramedic-level care service delivery on department med units at minimum staffing points and all apparatus when stations are fully staffed.

All med units, pumpers, and ladder trucks carry an assortment of BLS/ALS medical equipment (LIFEPAK 15 cardiac monitor/defibrillators, cardiac and respiratory medications, basic and advanced airway adjuncts, oxygen, and various splints and bandages including tourniquets).

The LSFD is equipped and staffed to respond to technical rescue incidents within the city, contract areas, and mutual aid responses when requested. Each pumper and ladder truck carries equipment that can be utilized and deployed in the initial phase of a rescue. All firefighters are trained to the minimum of the awareness level. Depending on the complexity of the rescue, the department may be able to mitigate or stabilize the incident until Regional Technical Mutual aid units arrive to perform the rescue. Technical rescue mutual aid would be provided by the neighboring Central Jackson County Fire Protection District, Olathe Fire, or Kansas City Fire Department.

Equipment carried by pumper and ladder trucks consists of high-angle equipment, swift water rescue gear, ice rescue equipment, and auto extrication equipment.

Squad 1 and all pumpers carry a complement of specialty stabilization struts that are used for vehicle stabilization, and trench or structural collapse wall support. The three frontline ladder trucks and Pumper 1 also carry an assortment of high-pressure airbags used for vehicle stabilization during auto extrication. All frontline pumpers carry lumber for cribbing, and Holmatro electric extrication tools that are light enough to be carried by a single firefighter. This system improves the efficiency of deploying essential extrication equipment at the incident location.

Squad 1 is a triple-use apparatus with additional rescue equipment to support the incidents of high angle, swift water, ice, trench, and confined space rescue. This vehicle also contains equipment to help mitigate hazardous materials incidents and the technological capabilities to serve as a mobile command post.

23: Technical Rescue Incidents (2019-2023)

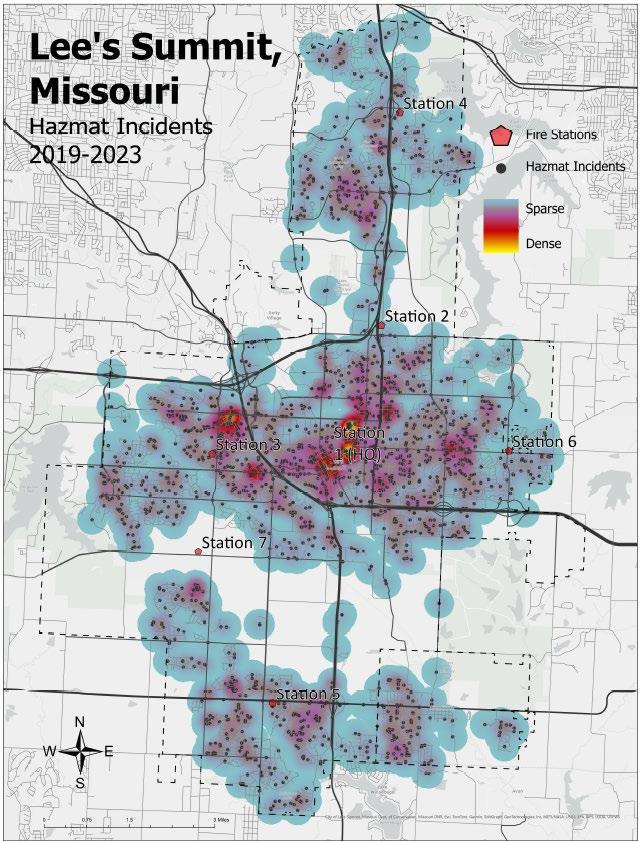

The LSFD is staffed and equipped to respond to hazardous conditions incidents within the city, its contracted response areas, and mutual aid when requested. All firefighters in the department are trained to the hazardous materials awareness and operations levels. All pumpers, ladder trucks, med units, and command vehicles carry air monitoring equipment, isolation, and decontamination equipment, and/or supplies to contain or isolate hazardous material spills.

Currently, the department has a hazardous materials team consisting of 14 members spread across the 3 shifts that are trained to the hazardous materials technician level. This team can respond to incidents within the city and is one of eight in the area (Olathe; Overland Park; Kansas City, Kansas; Leavenworth; Kansas City, Missouri; Independence; and Central Jackson County) available to respond for mutual aid to other departments. The Hazardous Materials team utilizes Squad 1, a cross-staffed command vehicle, which carries monitoring equipment capable of detecting and identifying hazardous materials, personal protective equipment, decontamination supplies, research computers, and additional equipment to contain/isolate hazardous material spills.

The LSFD is also one of three departments to house a Regional Weapons of Mass Destruction trailer supplied by the Mid-America Regional Council (MARC). The trailer is supplied with equipment to respond to biological, nuclear, incendiary, chemical, and explosive incidents in the region.

Map 24: Hazardous Conditions Incidents (2019-2023)

The department has an 18’ Triton Boat that has been retrofitted for fire department operations. This water response unit is trailered at Station 1 and cross-staffed by on-duty crews. Boat 1 can also be staffed with personnel from other responding apparatus, or by recalled personnel. The boat is designed to be utilized for surface water rescue and personnel transport for medical calls on the water, the boat is not equipped for firefighting operations. The boat is equipped with sonar equipment which is utilized for victim location and recovery. The department carries Rapid Deployment Crafts (RDC) on four front-line pumpers and both reserve pumpers, with large bodies of water in their response districts. These RDCs can be assembled and deployed for emergency response by the first arriving apparatus for emergent water and ice rescue events. All boat operational training is facilitated by the department. All operations personnel are required to take training to qualify for their Missouri Boater Education license.

The department also has a 1.5 million square foot subterranean space (cave system) that is occupied by multiple businesses. The department has an apparatus (Squad 4) stationed inside the subterranean space. This apparatus is a John Deere Gator with a trailer that carries SCBA, hose, ventilation fan, and extinguishers. This response vehicle is utilized on fire incidents inside the subterranean space by the first arriving units on scene. The department has developed standard operational guidelines for all operations within the subterranean space due to the specialized operations and the communication challenges the cave system presents. The department responds to all incidents in the subterranean space, covering all mission programs.

The department also has a Tactical Medic Team, which is used within Lee’s Summit Police Department’s Emergency Service Squad. The team is committed to providing ALS support at the request of law enforcement and acts as a liaison with LSFD personnel. The team is comprised of a minimum of seven personnel, with one of those being the Tactical Medic Team Coordinator and all others as Tactical Medic Operators, overseen by an assistant chief. All team members must be veteran paramedics and be able to

pass rigorous physical agility tests. The team is trained to assist in a variety of scenarios ranging from mass casualty incidents and K-9 operations to operations involving hostage situations.

The department currently has one drone and four drone pilots. The drone program is in its early stages, with very limited capabilities, but the plan is to expand the program to include reconnaissance capabilities.

The Fire Prevention Division of the LSFD is responsible for the Community Risk Reduction programs. This division is also responsible for the department’s loss prevention programs, Fire Investigation Unit, youth and adult fire education program, fireworks inspections, building plan reviews, and inspections of new construction, as well as tiered inspections of existing businesses. Six personnel are assigned to this division, led by the assistant chief of prevention, who is assisted by a battalion chief and a captain. Three engineers were added to the Prevention Division in 2023 and are assigned to a shift as inspectors/investigators. The additional inspectors are the first addition to the division since 1996.

Education programs created by the Fire Prevention Division are delivered to adult and youth classes by the Public Education Team and members of the division. The department is working to establish and revamp programs in the schools or find alternatives to in-class presentations. This team consists of various personnel from the department that have received training in this discipline with most being Fire Instructor 1 certified. Youth classes include, but are not limited to, elementary school fire safety classes, as well as station tours and fire safety for youth groups within the city. Adult education classes delivered jointly by the fire prevention and training divisions include CPR classes and home safety classes, as well as career days for high school age and up.

The Fire Prevention Division is responsible for doing all inspections on new construction. Existing building inspections are done by the Operations and Fire Prevention Divisions. Inspections are done on a tiered system based on risk to life, infrastructure, and economic impact. Existing building inspections are distributed between the three shifts and stations to allocate resources efficiently. The tiered inspection program, the addition of an electronic inspection program with the new records management system (RMS), and the use of a compliance engine have improved the overall effectiveness of existing building inspections. This has allowed for proactive enforcement of building systems as the occupants are notified before the department shows up for the inspection. This has resulted in more timely voluntary compliance by building owners/occupants on compliance issues.

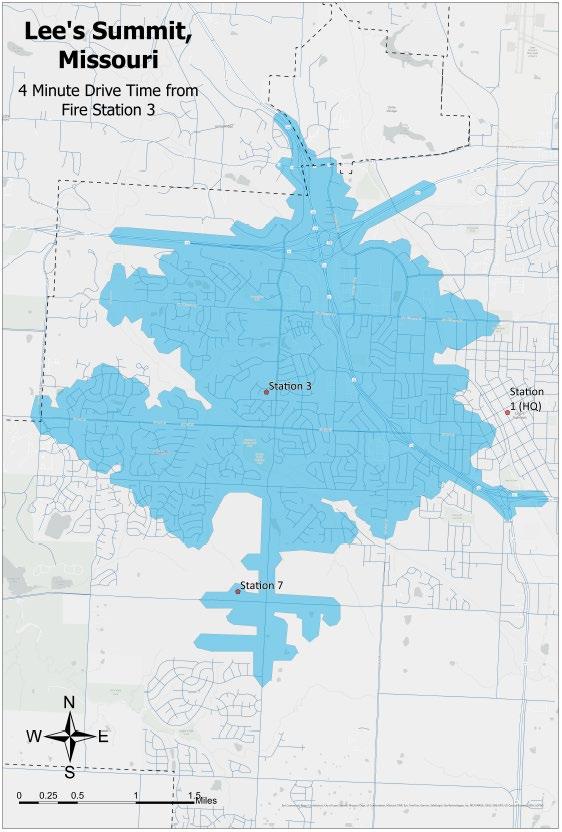

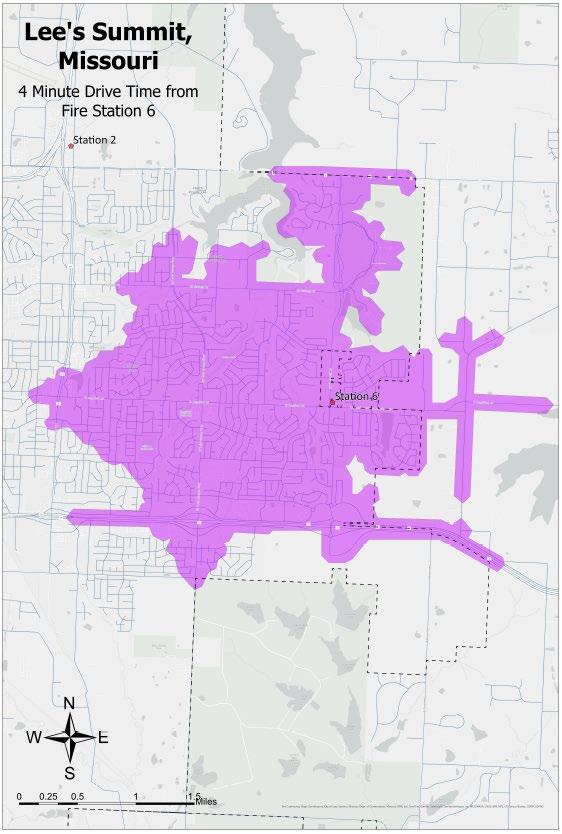

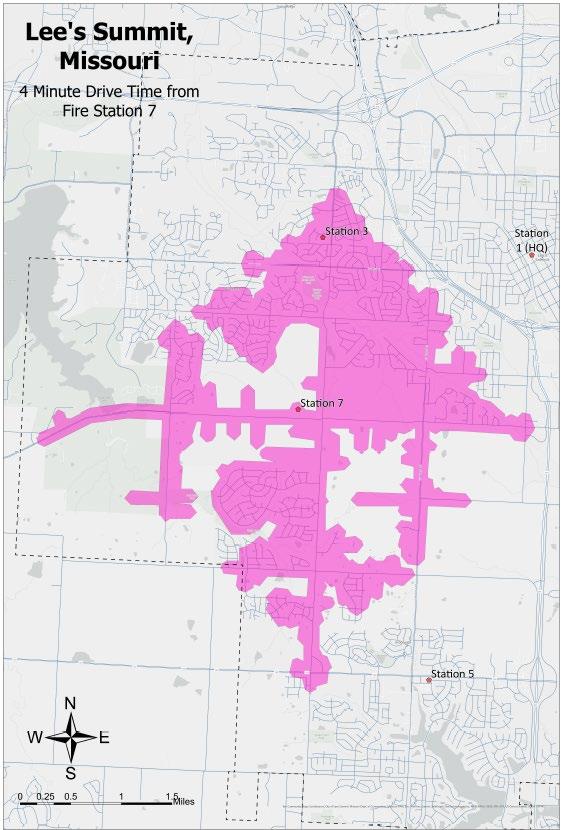

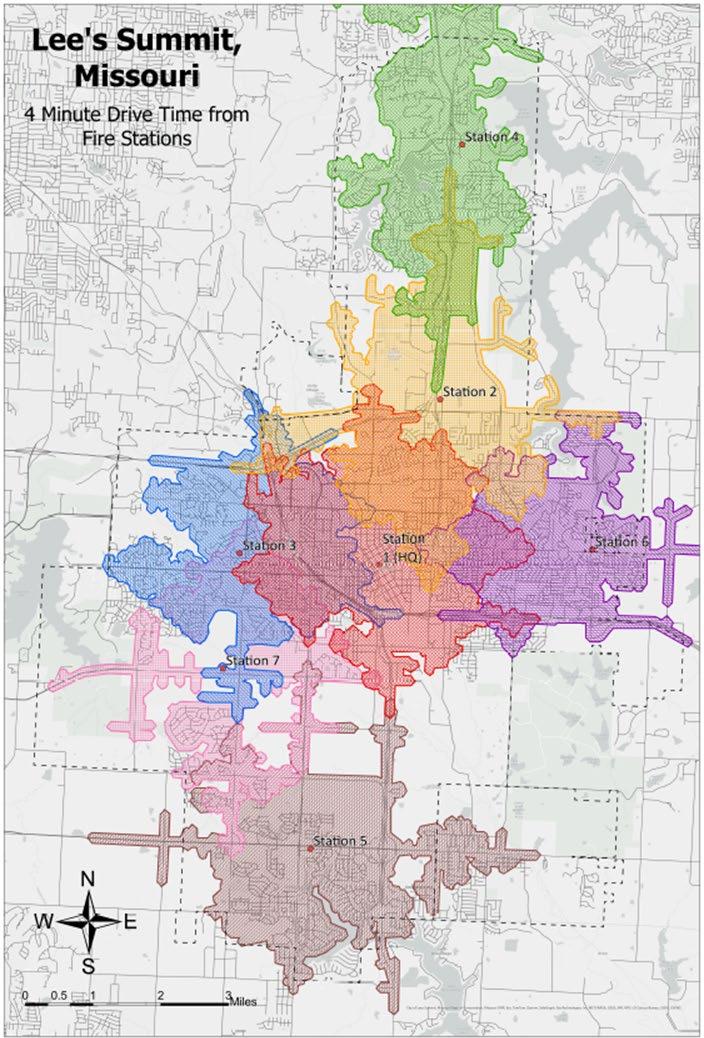

Map 25: Four-Minute Drive Time from all Fire Stations

There are currently seven fire stations strategically located within the city which are also utilized for primary response to Greenwood and Unity Village through contractual agreements. Deployed from the seven stations are five pumpers, three ladder trucks, and seven med units, which are all staffed 24 hours a day. The four-minute drive time map provides details about what areas of the service area are outside the benchmark and areas that are reached by more than one station within that timeframe. Analyzing drive time data based on CUR, current speed limits, and typical response areas for each station will aid in future decision-making as it pertains to future station and/or apparatus additions, apparatus placement, and staffing.

Table 3: Deployable Resources by Station

*Personnel at Station 1 includes an on-duty shift Prevention Engineer. Stations 2 and 3 include a shift commander.

*Gator at Station 4 is in the subterranean space in Station 4's district.

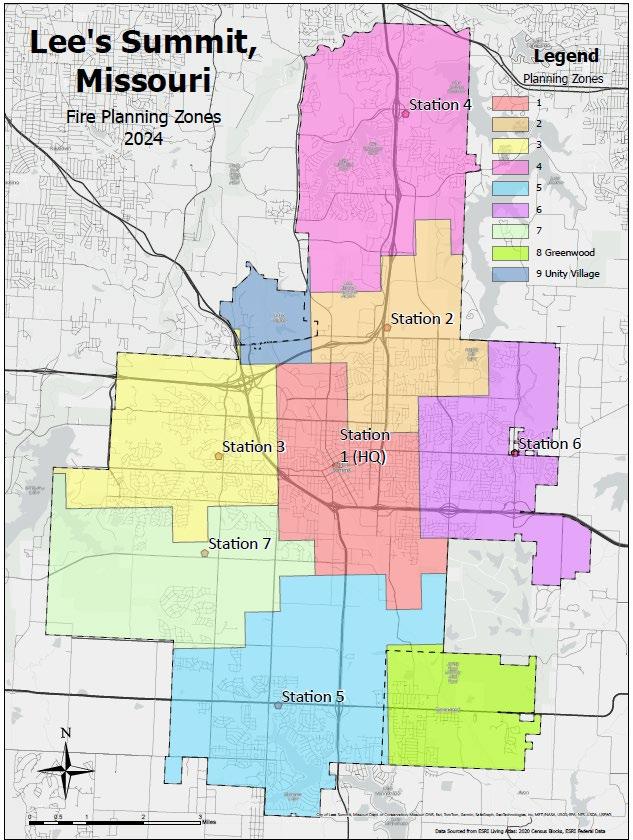

There are currently seven planning zones within the city and one for each contracted service area. Inside each planning zone within the city is a deployment location for emergency operations: a fire station. The department transitioned to automatic vehicle locating (AVL) on all frontline apparatus and most reserve apparatus in 2019. This allows for the fastest routable deployments for all incidents within the city, Greenwood, and Unity Village. Fastest routable dispatching considers the location of all apparatus, roadway speeds, and closed road segments and then assigns the available units. Frequently, units will respond from different areas throughout the community. This occurs while performing emergent and non-emergent functions, such as training, business fire inspections, public education events, refueling, or maintenance transitions.

Table 4: Area

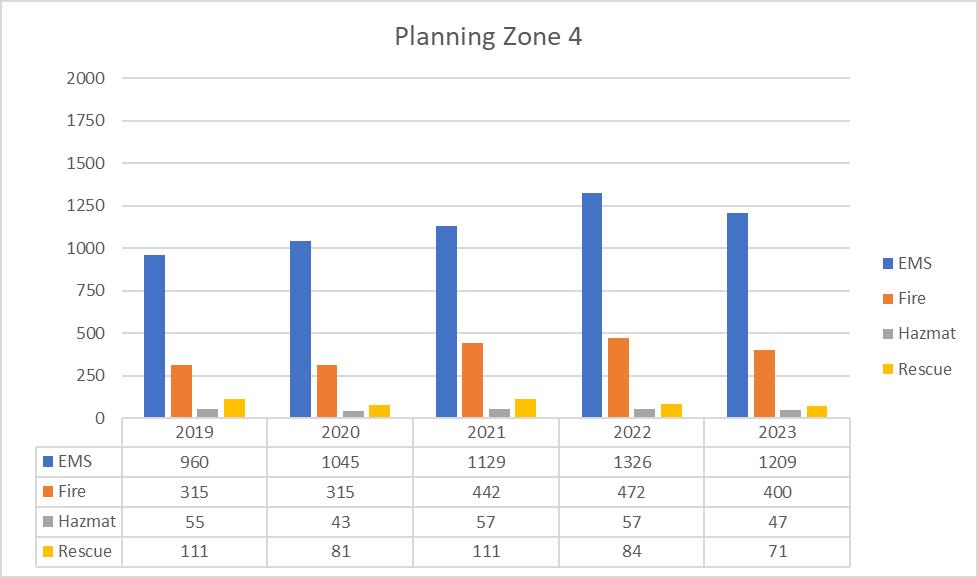

The following table depicts the service demand in the jurisdiction by incident type over the past five years. The risk classifications are established based on the dispatch information received rather than on the type of incident found at the scene. EMS incident examples include emergency medical calls and patient transfers. Fire incident examples include car and structure fires as well as smoke alarms. Hazardous Conditions (HazMat) examples would be fuel spills, carbon monoxide, gas line breaks, or other hazardous materials-related incidents. Technical rescue incidents include all motor vehicle collisions and other technical rescue events.

Table 7: Call Types by

Mission Statement

The Lee’s Summit Fire Department is dedicated to serving our community through prevention, preparedness, and response with PRIDE.

Values

Professionalism

A commitment to consistently achieve high standards through training and personnel development.

Respect Compassion and empathy for our community and each other.

Integrity

Duty

An uncompromised commitment to trust, honesty, and ethical services to our community and each other.

A commitment to carry out the mission of the department.

Excellence Continually striving to be the best.

In 2013, the department published a mission statement during the first strategic planning process, and in 2018, during another strategic planning process, the department revised the statement. During the 2023 strategic planning process, the mission statement was revisited and updated through internal stakeholder consensus. The department felt that this revised mission statement accurately reflected the commitment of the department to the community and was current, relevant, and accurately reflected the motivation of the sworn and non-sworn personnel in this department.

In 2023, the department conducted a strategic planning process with assistance from the Center for Public Safety Excellence (CPSE) Technical Advisor Program (TAP). This process engaged the community through an external stakeholder group that provided insight into their expectations of the services provided by the Lee’s Summit Fire Department. The external stakeholder group consisted of 26 members of the community from the areas of business, education, non-profit, faith-based, health care, city departments and governance, and area residents.

Participants were asked to prioritize the programs offered by the department, using a matrix to rank how important each service was to them via a direct comparison to the other services that are provided by the department. The individual responses were then totaled, and the results of the comparison were as follows:

1. Emergency Medical Services

2. Fire Suppression

3. Technical Rescue

4. Fire Prevention

5. Emergency Management

6. HazMat Mitigation

7. Fire Investigation

8. Public Education

Understanding what the community expects of its fire and emergency services organization is critically important to developing a long-range perspective. In 2023, the external stakeholders provided a total of 24 expectations of Lee’s Summit Fire Department and its personnel. The top four expectations received are listed verbatim and in priority order below.

1. Response Times. Quick response times. Low response times. Timely response. Reducing emergency response time as much as possible. Quick response time. Respond to emergencies in the shortest time possible. Timely arrival. Quick response times to an emergency. Fast, effective response.

2. Training. Well-trained and educated team members. Capable/knowledgeable/well trained. Continued education and support for all responders. Ongoing training. Trained and experienced staff. Proper training. To remain current with training. Well-trained employees. Consistency - ability to perform what is needed.

3. Public Safety. Public safety. Emergency response. Safety and security of residents and business/organizational stakeholders. Quality care of residents in need of assistance.

4. Community Involvement. Community education. Partnerships in the community. Partner with other stakeholders to better serve the community. Community outreach. Great communication with stakeholders. Community engagement.

Prior to becoming accredited, Lee’s Summit Fire Department utilized a goal of five-minute emergency response travel time for the first arriving unit at the scene of an emergency incident. This goal was unwritten but had been expressed during council meetings and discussions with the public as the department’s benchmark.

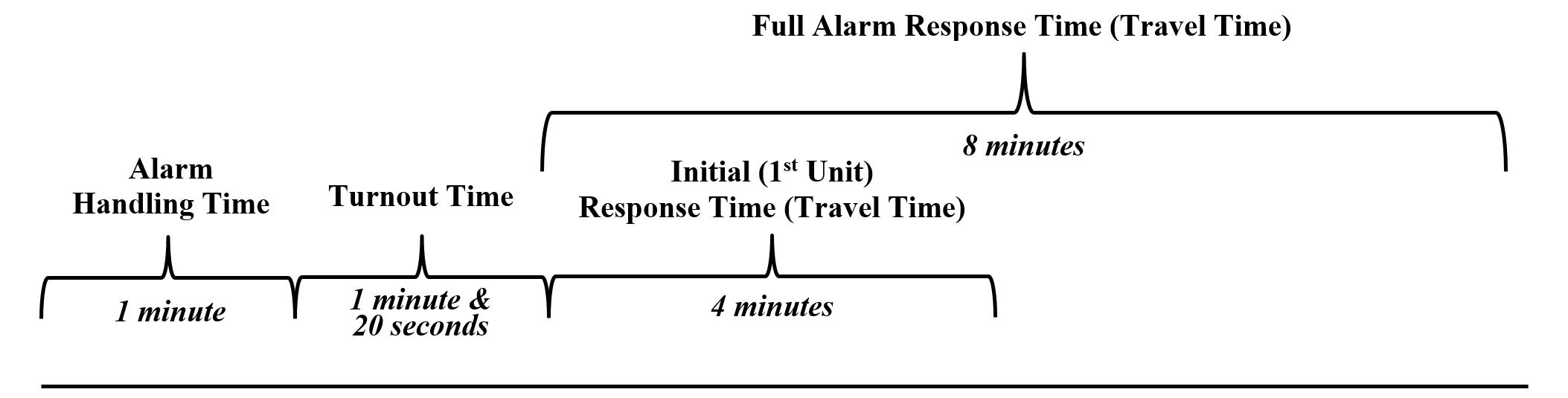

Through the department’s involvement with the CFAI model, it became apparent that basing performance goals on travel time alone did not include all the information necessary along the response time continuum to make informed decisions on areas in which improvement was indicated and achievable. Travel time alone was but one component of a more accurate and detailed process for measuring performance.

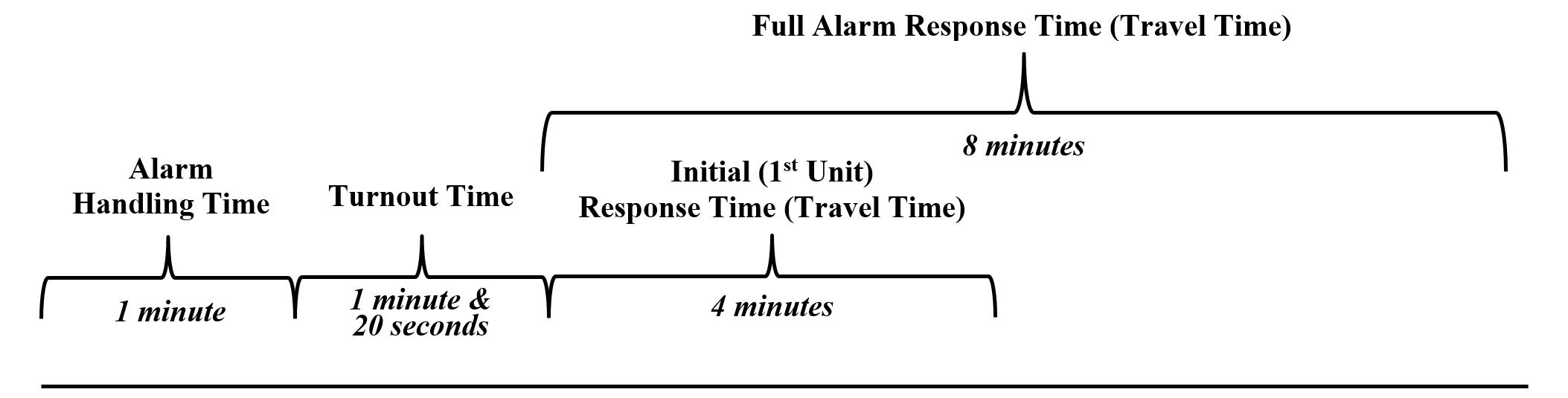

A fundamental element of the standards of cover is total response time reporting. This includes benchmarks for alarm handling, turnout time, travel time, and travel time for an effective response force, resulting in a benchmark for the total response time of the first arriving unit and total response time for an effective response force.

As a result, the department set and published performance goals as recommended by CPSE and in compliance with the 10th Edition Quality Improvement for the Fire and Emergency Services To provide the community with the best service possible, the department chose to adopt the performance goal standards established in the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1710. The adopted standards provide the department with the opportunity to continue to improve to meet the benchmarks and provide transparency to the dataset. The response time standards identified within NFPA 1710 set service delivery objectives (benchmarks), including specific time objectives for each applicable department risk class (Fire Suppression, EMS, Technical Rescue, and Hazardous Conditions).

There are four components of response time identified and benchmarked: alarm handling, turnout time, travel time for the first arriving unit, and total response time for an effective response force to mitigate the incident. Alarm handling refers to the time interval from receiving the alarm at the secondary public safety access point (PSAP) to dispatching the responding units. Turnout time refers to the time interval from the dispatch information to responding with the assigned apparatus. Travel time refers to the time interval from en route to the emergency incident and ends with the unit’s arrival on scene. Effective response force (ERF), also known as concentration, is the total time to get all assigned units on scene of the emergency. Total response time refers to the interval from receipt of the alarm at the PSAP to when the first emergency unit initiates an action or intervenes to control the incident. There is a primary PSAP time value that has not been included in this analysis due to the department’s inability to accurately capture that information from the Mid-America Regional Council (MARC) and the multiple primary PSAPs from which calls are received.

Table 8: Response Time Benchmarks

The Lee’s Summit Fire Department elected to continue to evaluate risk using a three-axis categorization measurement approach consisting of threat probability (Y-axis), consequences to the community (X-axis), and impact on the agency (Z-axis). This three-axis measurement utilizes Heron’s Formula, modified for tetrahedrons, to produce a quantifiable value for risk based on numerical values representing each axis in the formula.

Probability refers to the likelihood of an event occurring in the community. It is based on the incidents reported to the National Fire Incident Reporting System (NFIRS) for the past five years (2019-2023).

Consequence assesses how a specific type of incident would affect the community by assessing the number of patients, number of vehicles or structures involved, types of structures, and the impact on community infrastructure.

The impact is related to the number of personnel on fire department resources used to mitigate each specific incident and the reliability of the resources remaining to continue to deliver services to the community.

Probability, consequence, and impact were each quantified with an assigned value from 2 to 10, with the 2-value representing a lower element of risk and the 10-value representing a maximum element of risk. Each value was represented as a point on the axis, which, when combined, forms a tetrahedron that is measured to illustrate the overall risk score of the event.

All fire suppression, emergency medical, hazardous conditions, and technical rescue incidents underwent a critical task analysis to determine the quantifier used in the impact determination before completing an overall risk score. The incidents were evaluated, scored, and ranked, creating multiple distinct risk categories. Impact, probability, and consequence were scored, and that defined risk levels from low to maximum modified depending on the hazard against the incident type, facility, or location.

All emergency incident types were evaluated and scored for each program classification by members of the Standards of Cover (SOC) team. The SOC team consisted of one deputy chief, two assistant chiefs, two engineers from the Operations Division, the supervisor and one lead communications specialist from the Communications Center, and the accreditation manager.

Apparatus in the department are dispatched based on the type of incident that a caller describes, and each incident type has a set alarm assignment. Each incident type in the Computer Aided Dispatch (CAD) system is assigned an alarm assignment of either low, low modified, moderate, moderate modified, high, high modified, maximum, or maximum modified. If additional staffing is needed, these alarm assignments can be upgraded, or the incident commander or the first due unit can request additional apparatus. The list of incident types, incident descriptions, and the amount and type of units to be dispatched on the initial alarm are in the department’s guiding documents. All dispatched alarm levels are based on the information provided to the communications center by the caller through Emergency Medical Dispatch (EMD) or Emergency Fire Dispatch (EFD) questioning.

Critical tasks and associated staffing that are needed to mitigate a low-level fire risk incident are listed in the following table. Examples of these types of incidents are lift assists, passenger vehicle fires, unknown type fires, automatic commercial or residential alarms, and haze of smoke inside a residential structure. The critical task analysis determines the effective response force deployment necessary to mitigate the reported incident associated with the risk level assignment.

Table 9: Critical Tasks - Low Risk Fire

Critical tasks and associated staffing needed to mitigate a moderate-level fire risk incident are listed in the tables to follow. There are different tables due to the type of apparatus that are needed to mitigate different kinds of moderatelevel fire risk incidents. The critical task analysis determines the effective response force deployment necessary to mitigate the reported incident associated with the risk level assignment. Examples of these types of incidents are power lines down/transformer fire with a patient and a vehicle fire (car, pickup, van) with a patient.

Table 10: Critical Tasks - Moderate Risk Fire

Examples of these types of incidents are automatic commercial alarms with water flow, haze of smoke in a commercial structure, and shed/detached outbuilding fires.

Table 11: Critical Tasks - Moderate Risk Fire

Examples of these types of incidents are grass/brush fires with a patient and large grass/brush fires. Table

Examples of these types of incidents are boat fire on the water with or without a patient.

Table 13: Critical Tasks - Moderate Risk Fire

Critical tasks and associated staffing needed to mitigate a moderate modified-level fire risk incident are listed in the following table. Due to the type of apparatus that are needed to mitigate different kinds of moderate modified-level fire risk incidents, there are two different resource dispatches. The critical task analysis determines the effective response force deployment necessary to mitigate the reported incident associated with the risk level assignment. Examples of these types of incidents are commercial vehicle fire, aircraft fire, and unknown situation/investigation of a train.

An example of this type of incident is a flue/chimney fire.

15:

Critical tasks and associated staffing needed to mitigate a high-level fire risk incident are listed in the following table. Examples of these types of incidents are residential structure fires (single-family, duplex, or row townhome), a lightning strike of a structure, large outside fire, and a residential explosion. The critical task analysis determines the effective response force deployment necessary to mitigate the reported incident associated with the risk level assignment.

Critical tasks and associated staffing needed to mitigate a high modified-level fire risk incident are listed in the following tables. There are different tables due to the type of apparatus that are needed to mitigate different kinds of high modified-level fire risk incidents. The critical task analysis determines the effective response force deployment necessary to mitigate the reported incident associated with the risk level assignment. An example of this type of incident is a boat fire on the water with multiple patients.

Examples of these types of incidents are a grass/brush fire associated with a structure and a grass/brush fire with multiple patients.

An example of this type of incident is a commercial structure fire.

Table 19: Critical Tasks - High Modified Risk Fire

An example of this type of incident is a residential structure fire in a rural water area.

Table 20: Critical Tasks -

Critical tasks and associated staffing needed to mitigate a maximum-level fire risk incident are listed in the following

table. Examples of these types of incidents are commercial building explosion, high life hazard commercial structure fire (churches, hospitals, apartment complexes, hotels, nursing homes, and schools), and commercial aircraft fires/crashes. The critical task analysis determines the effective response force deployment necessary to mitigate the reported incident associated with the risk level assignment.

Table 21: Critical Tasks - Maximum Risk Fire

Critical tasks and associated staffing needed to mitigate a maximum modified-level fire risk incident are listed in the following table. Examples of these types of incidents are a train crash/fire and explosions with mass casualties. The critical task analysis determines the effective response force deployment necessary to mitigate the reported incident associated with the risk level assignment.

Table

Critical tasks and associated staffing needed to mitigate a low-level emergency medical services (EMS) risk incident are listed in the following table. Examples of these types of incidents are a medical alarm and an EMS response to a low-risk single patient. The critical task analysis determines the effective response force deployment necessary to mitigate the reported incident associated with the risk level assignment.

Table 23: Critical Tasks -

Critical tasks and associated staffing needed to mitigate a moderate-level EMS risk incident are listed in the following table. An example of this type of incident is an EMS response with one to two patients. The critical task analysis determines the effective response force deployment necessary to mitigate the reported incident associated with the risk level assignment.

Table 24: Critical Tasks - Moderate Risk EMS

Critical tasks and associated staffing needed to mitigate a moderate modified-level EMS risk incident are listed in the following table. An example of this type of incident is an EMS response with a non-breather or critical patient. The critical task analysis determines the effective response force deployment necessary to mitigate the reported incident associated with the risk level assignment.

Table 25:

Critical tasks and associated staffing needed to mitigate a high-level EMS risk incident are listed in the following table. An example of this type of incident is an EMS response with 3 to 4 patients. The critical task analysis determines the effective response force deployment necessary to mitigate the reported incident associated with the risk level assignment. Table

Critical tasks and associated staffing needed to mitigate a maximum-level EMS risk incident are listed in the following table. An example of this type of incident is an EMS incident with five or more patients. The critical task analysis determines the effective response force deployment necessary to mitigate the reported incident associated with the risk level assignment. Table 27: Critical Tasks -

Critical tasks and associated staffing needed to mitigate a low-level technical rescue risk incident are listed in the following table. Examples of this type of incident are an elevator alarm/malfunction, a minor rescue, and a subject locked out of a structure. The critical task analysis determines the effective response force deployment necessary to mitigate the reported incident associated with the risk level assignment.

Critical tasks and associated staffing needed to mitigate a low modified-level technical rescue risk incident are listed in the following table. Examples of these types of incidents are a subject locked in a vehicle in extreme temperatures, motor vehicle collision (MVC) with pedestrian/bicycle struck (1 patient), and an MVC with a minor or unknown injury. The critical task analysis determines the effective response force deployment necessary to mitigate the reported incident associated with the risk level assignment.

Critical tasks and associated staffing needed to mitigate a moderate-level technical rescue risk incident are listed in the following table. Examples of these types of incidents are an MVC with 1 to 2 patients, swimming pool water rescue, and an elevator alarm with medical. The critical task analysis determines the effective response force deployment necessary to mitigate the reported incident associated with the risk level assignment.

Critical tasks and associated staffing needed to mitigate a moderate modified-level technical rescue risk incident are listed in the following table. Examples of these types of incidents are an MVC with 3 to 4 patients and an MVC with pedestrian/bicycle struck (2 to 4 patients). The critical task analysis determines the effective response force deployment necessary to mitigate the reported incident associated with the risk level assignment.

Table 31: Critical Tasks - Moderate Modified Risk Technical

Critical tasks and associated staffing needed to mitigate a high-level technical rescue risk incident are listed in the following table. Due to the type of apparatus that are needed to mitigate different kinds of high-level technical rescue risk incidents, there are two different resource dispatches. The critical task analysis determines the effective response force deployment, necessary to mitigate the reported incident associated with the risk level assignment.

Examples of these types of incidents are a vehicle in the water, machinery/industrial rescue, and high-angle rescue.

Examples of these types of incidents are an MVC with extrication, an MVC with five or more patients, and trench rescue.

Table 33: Critical Tasks - High Risk Technical Rescue

Critical tasks and associated staffing needed to mitigate a high modified-level technical rescue risk incident are listed in the following table. Due to the type of apparatus that are needed to mitigate different kinds of high modified-level technical rescue risk incidents, there are two different resource dispatches. The critical task analysis determines the effective response force deployment necessary to mitigate the reported incident associated with the risk level assignment.

Examples of these types of incidents are floodwater rescues and floodwater rescues with multiple patients. Table

Examples of these types of incidents are boat accidents on the water and water rescue. Table

Critical tasks and associated staffing needed to mitigate a maximum-level technical rescue risk incident are listed in the following table. An example of this type of incident is a large building/structure collapse. The critical task analysis determines the effective response force deployment necessary to mitigate the reported incident associated with the risk level assignment.