No. 83

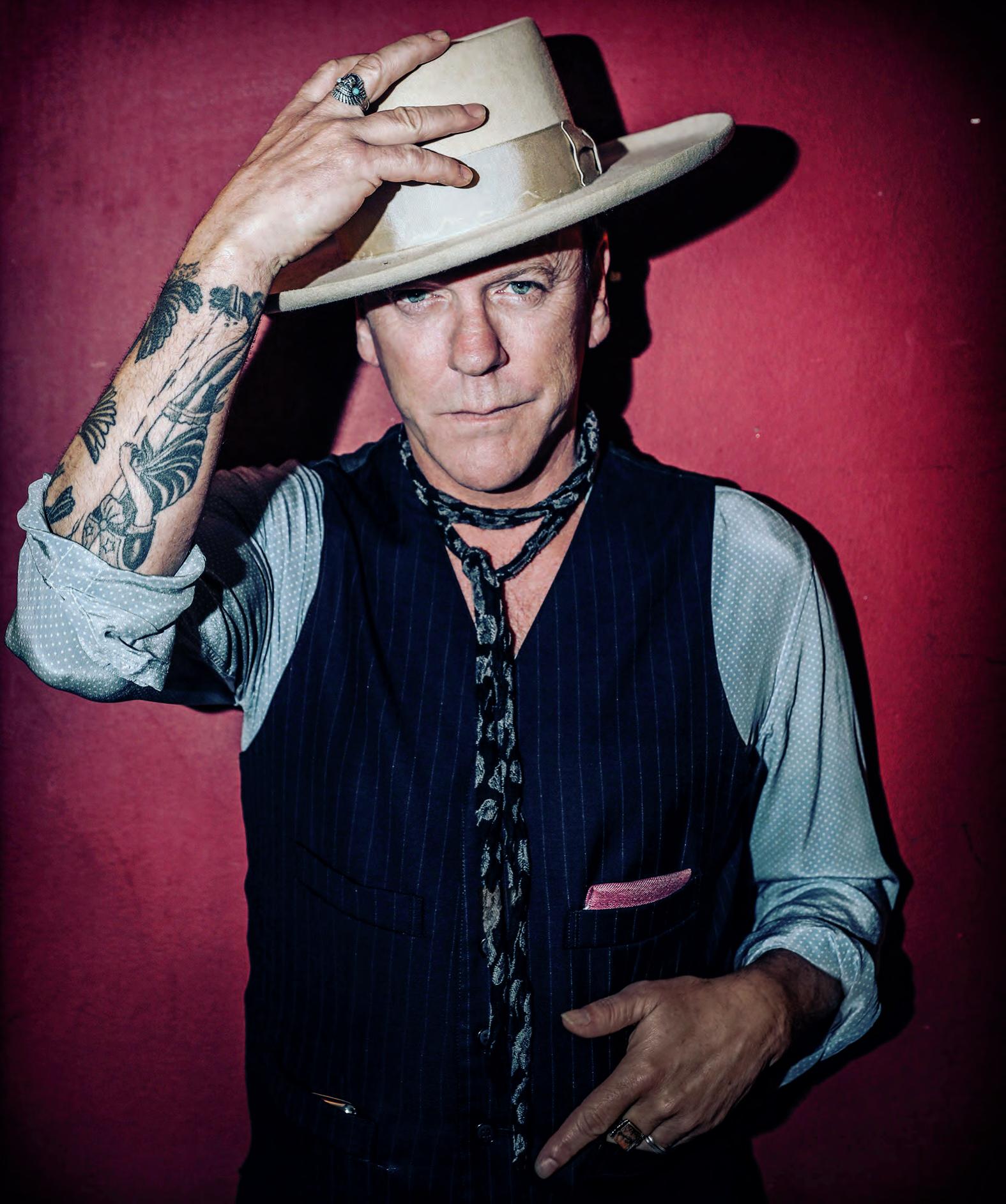

KIEFER IS BACK!

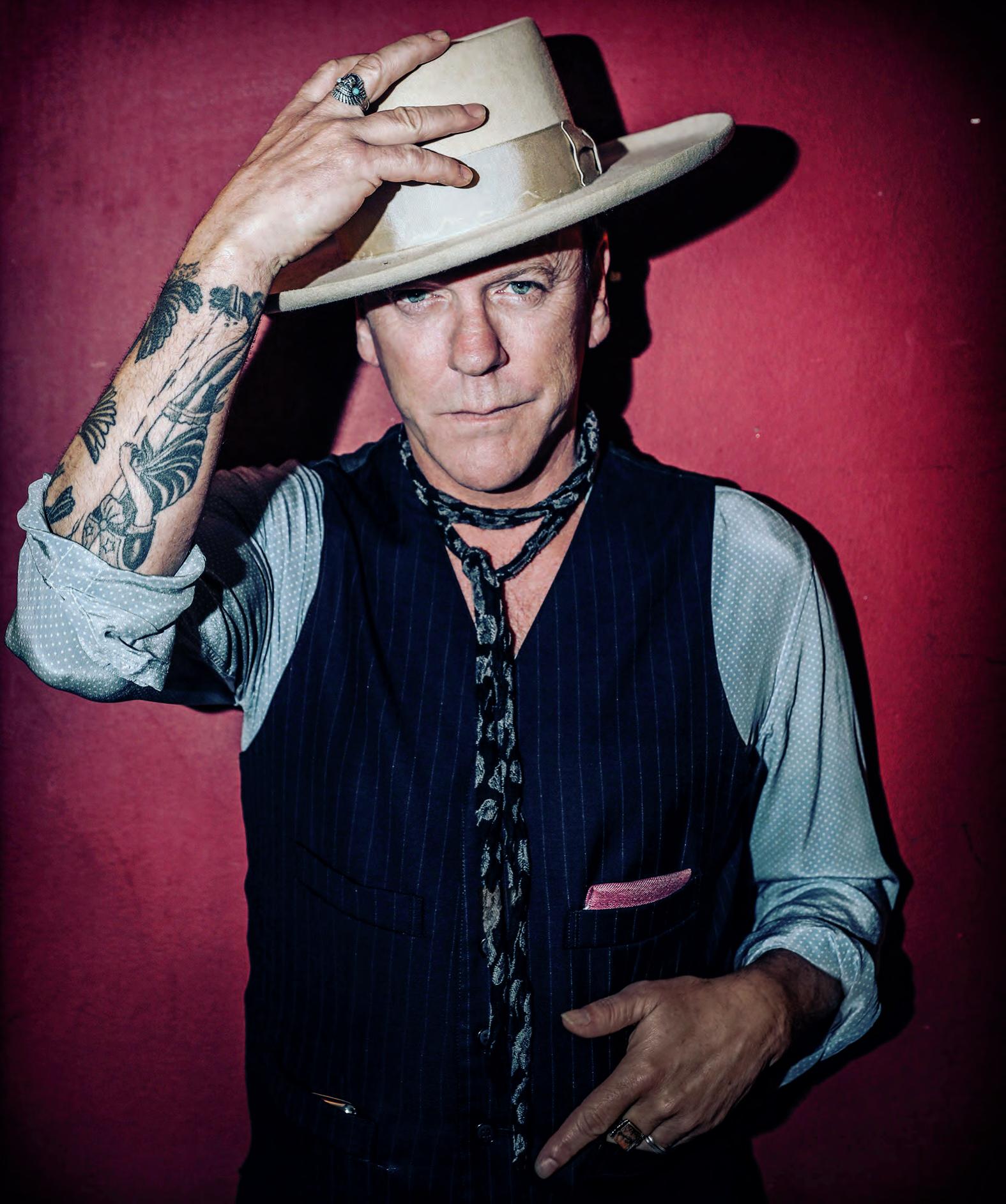

Kiefer Sutherland on getting older, launching a whisky brand and the state of America

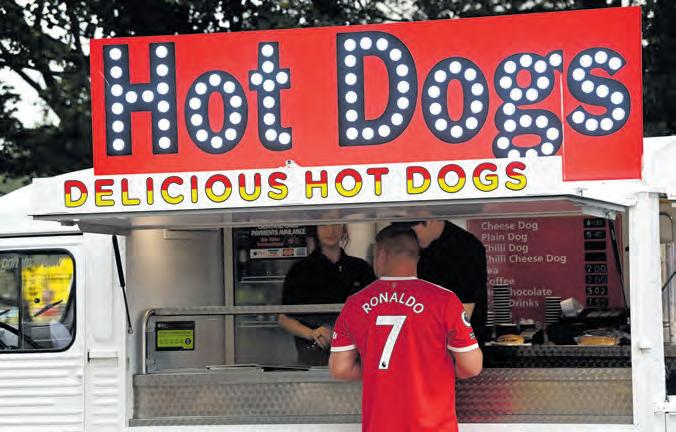

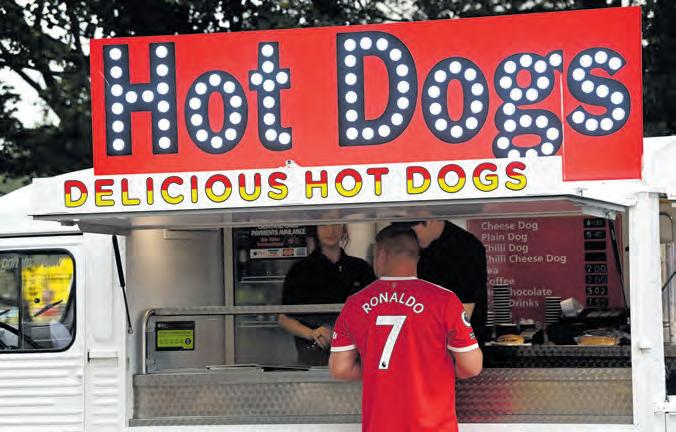

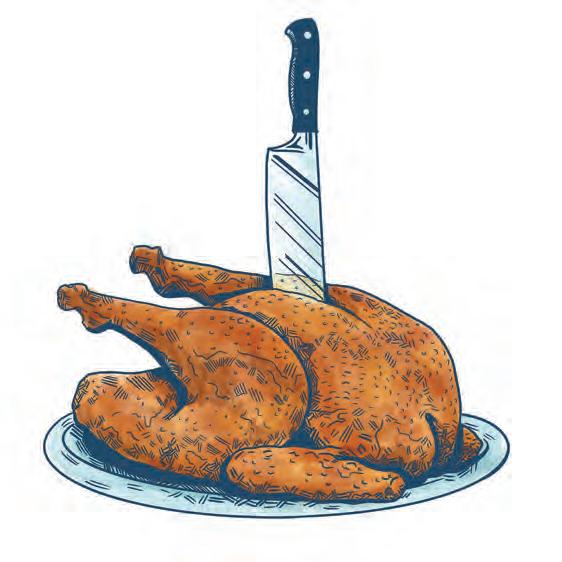

FOOTY SCRAN

How one man changed the face of match-day meals

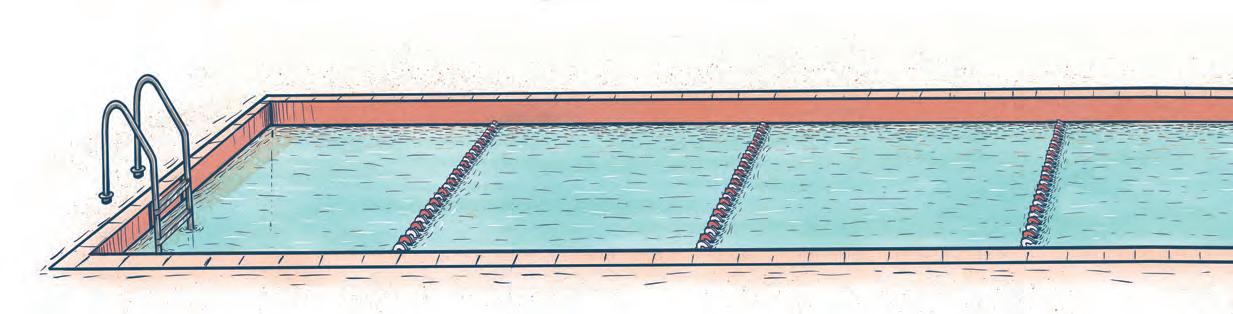

THE DEEP END

An appreciation of the humble public swimming pool

SUMMER 24

FOXES

They are the city’s ultimate survivors. We spend a day with London’s urban fox rescue crew

FEELING STRANGE

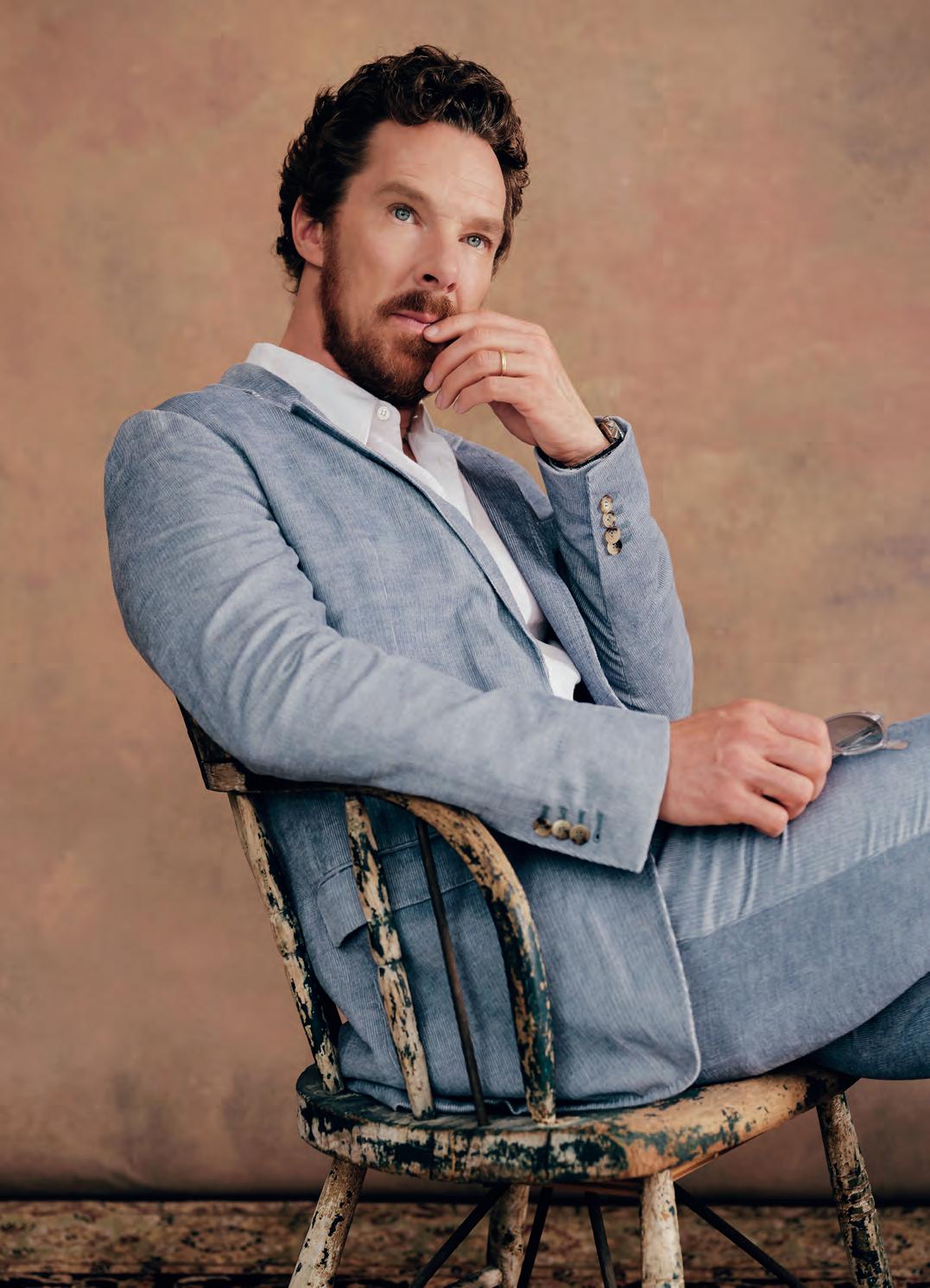

BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH ON ‘FACING THE DARKNESS’ IN HIS WEIRDEST ROLE YET

SECTION HERE 1

THE MAGAZINE

EDITOR’S LETTER INSIDE THIS ISSUE

How do you top an interview with the soon-to-be Prime Minister, as we had on our last cover?

Well, landing Benedict Cumberbatch, one of the finest actors of his generation, is a pretty good start. On P30 he talks about finding joy in misery, going grey and being his own worst critic.

Throw in Kiefer Sutherland (P46) and we’re on a roll. I met up with the actor-turned-musician to chat about everything from the student protests in America to what makes a good night out. For some insight into how we land these interviews – and what happens when they go wrong – check out my column on P8, in which recounts the time I stormed out of an interview with Henry Cavill and how I travelled half way around the world to be stood up by John Malkovich.

Elsewhere we have features from some of the hottest writers in the land, including a piece by Kyle MacNeill on his enduring love of Frankie & Benny’s – and why you should never go back. There’s plenty for city-dwellers, including hanging out with the urban fox rescue team (P34), a wistful defence of the municipal swimming pool (P38) and an introduction to the fine art of psychogeography (P42).

You can read all of these stories and more on cityam.com or our new app, which you can access by scanning this QR code. – STEVE DINNEEN

FEATURES REGULARS

20: SUNDAE SERVICE

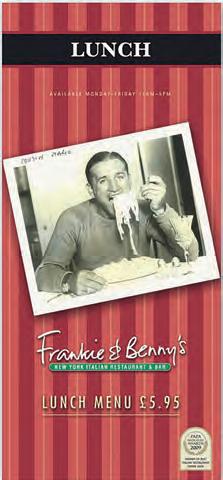

Frankie & Benny’s holds a special place in the heart of Kyle MacNeill. He returns to his beloved chain

42: PSYCHOGEOGRAPHY

A stroll through the city can change your whole way of thinking – if you know what to look for, at least

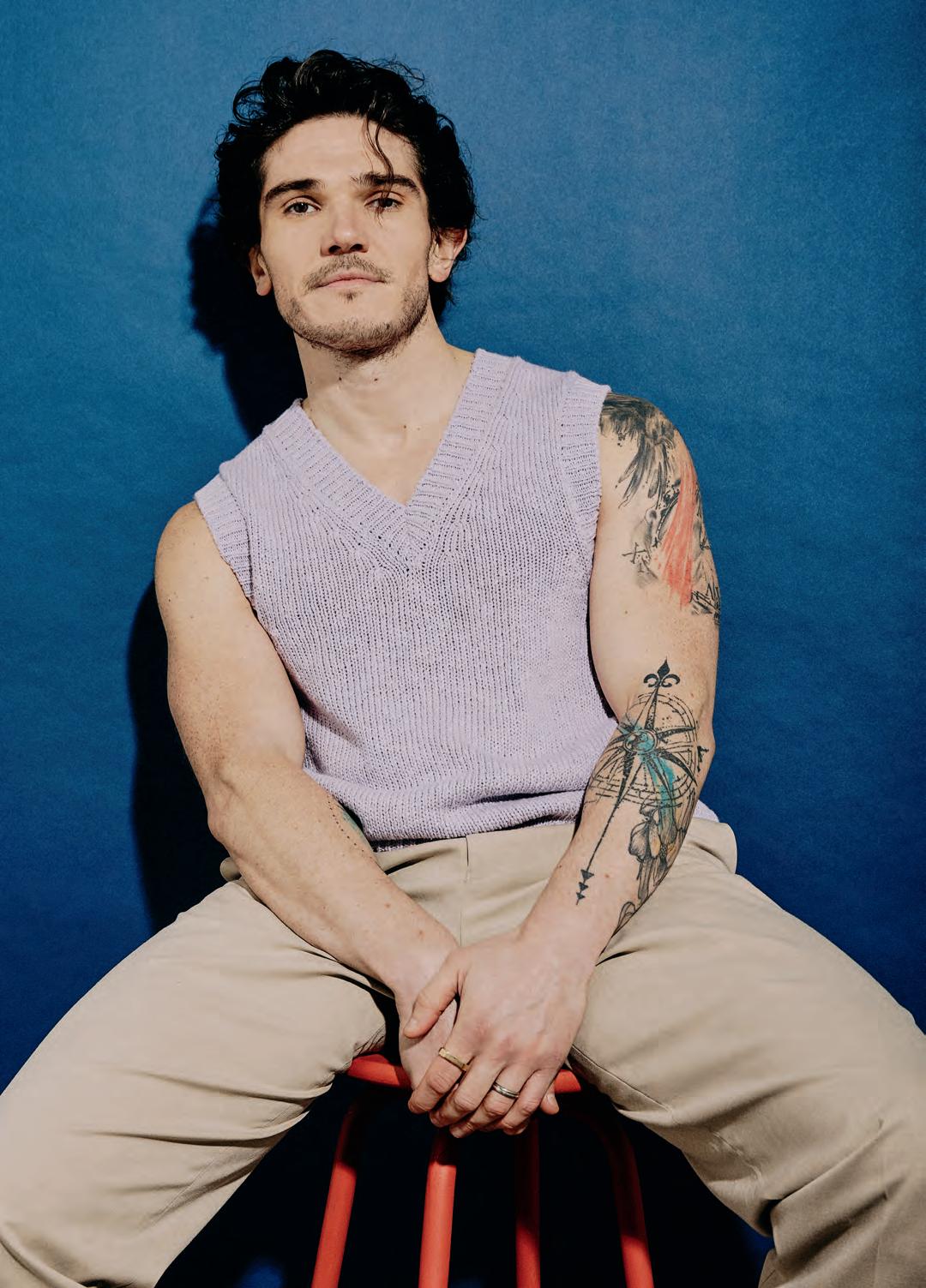

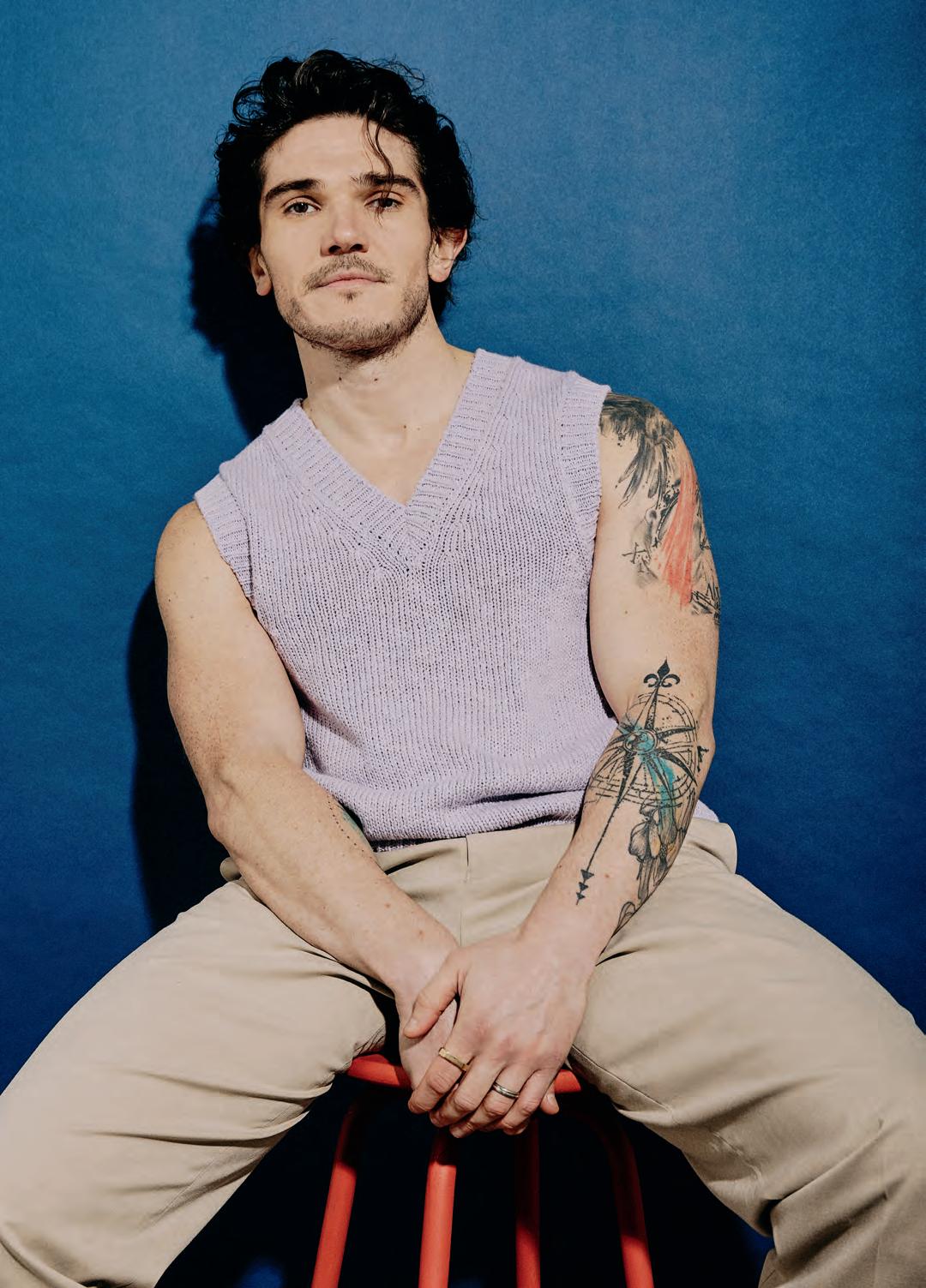

50: FRA FEE INTERVIEW

The star of new show Lost Boys and Fairies on the importance of queer representation on screen

72: YACHT CLUB

Setting sail off the coast of SaintTropez sounds like a dream come true – and it kind of is, to be honest

16: CHEF’S TABLE

Restaurateur Ravinder Bhogal interviews her friend, the renowned composer Nitin Sawhney

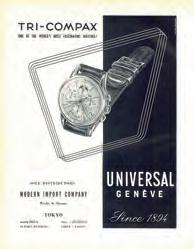

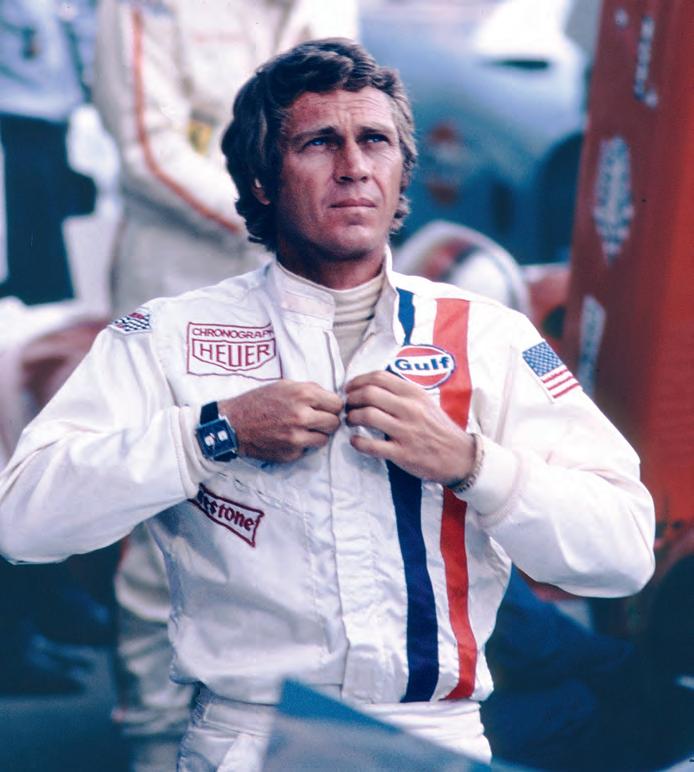

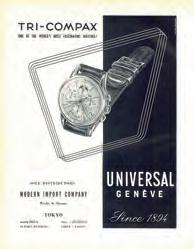

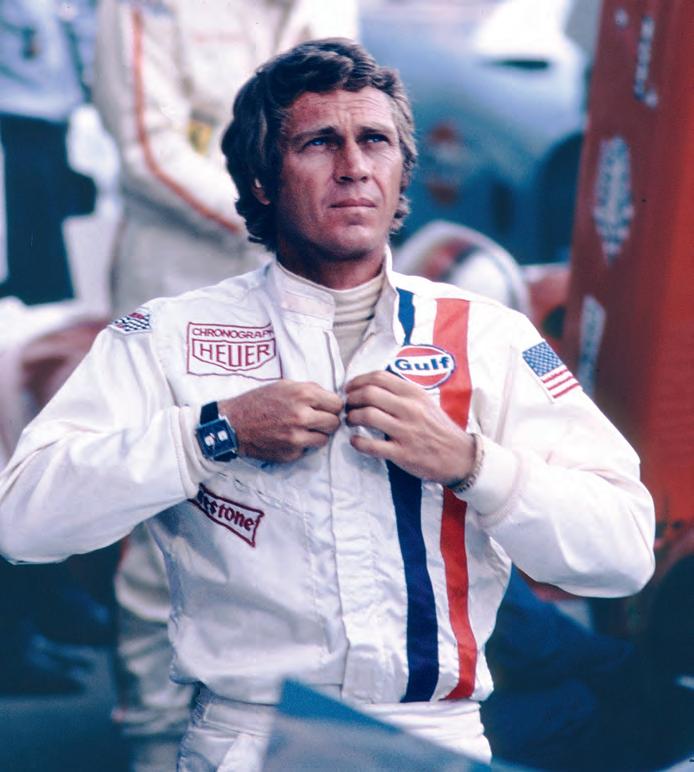

52: WATCHES

We round up the most iconic watches in movies, from Pulp Fiction to Trading Places and Interstellar

63: WELLNESS

We check in for a health retreat in an exclusive Thai resort that offers something incredibly special

90: THE LAST WORD

Nightlife in the UK isn’t dead – it just moved to new venues, and you got too old to know where it went

4

16 34

24 Scan for the City AM app

Above: We explore how the @FootyScran X account changed the way clubs serve food at football matches; Below from left: A spirited defence of the urban fox; Ravinder Bhogal and Nitin Sawhney chatting in Jikoni restaurant

We love quality watches – so much so that in 2004 we started making our own. Combining award-winning English design with the finest Swiss watchmaking skills, and concentrating on craftsmanship rather than salesmanship, we’ve created watches that are the equal (or better than) the world’s most celebrated brands in every respect. Apart from price. The C1 Bel Canto is one such watch. But don’t take our word for it: Do your research

CONTRIBUTORS

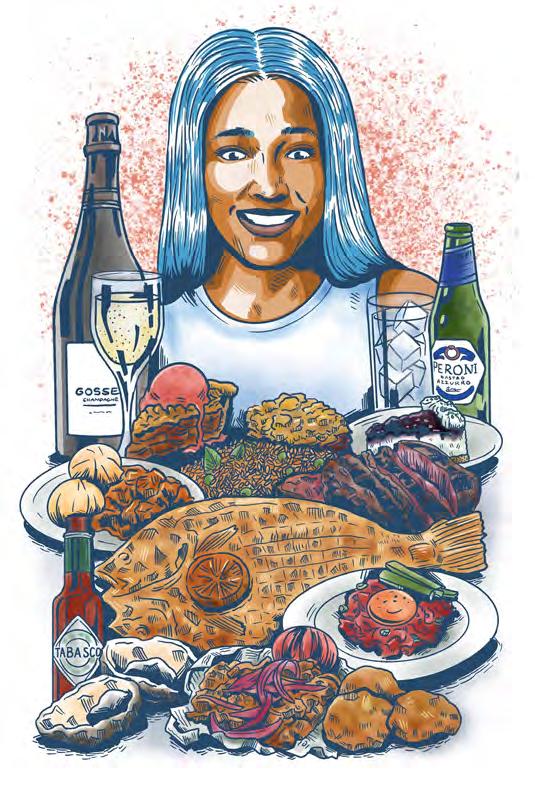

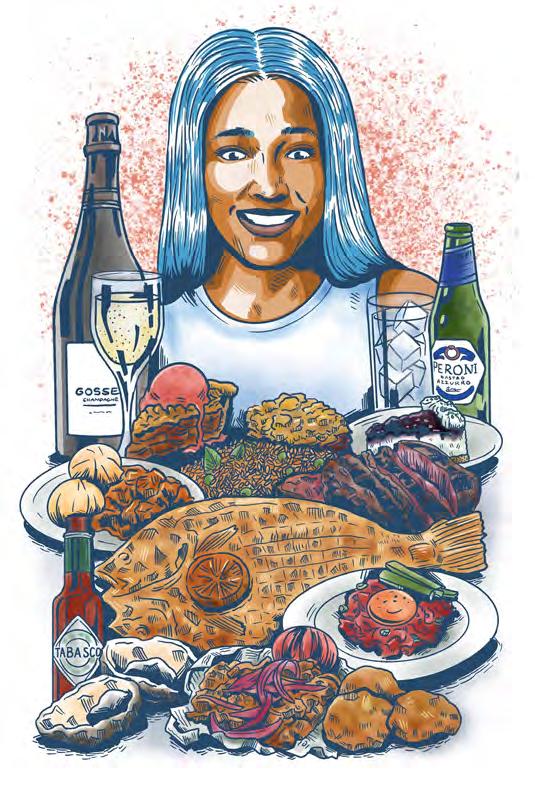

ADELAYO ADEDAYO is an actor who has starred in shows including Sket and Some Girls. On P28 she tells us what she’d eat for her last meal, from her mum’s jollof rice to a Hawksmoor steak

LUCY KENNINGHAM is a features writer with a passion for industrial architecture. On P38 she dives into the world of municipal swimming pools, defiantly untrendy place people go to lose themselves

KYLE MACNEILL is a pop culture writer with fond memories of Frankie & Benny’s. On P20 he returns to the scene of his childhood birthdays and discovers a different beast than he had left behind

ANDY SILVESTER is the editor of our sister title City A.M. On P34 he goes in search of London’s urban foxes and defends these wrongly maligned city dwellers

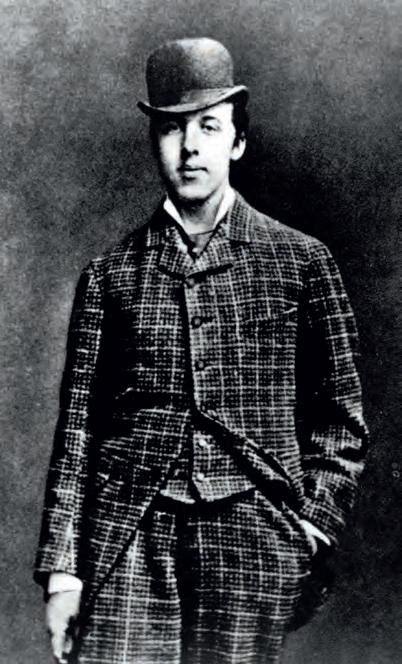

ANNA MOLONEY is the magazine’s resident bookworm, keeping us abreast of all the happenings in the world of literature. On P88 she sings the praises of Oscar Wilde

When he’s not playing with his band Totally Amorphous, CHRIS DORRELL enjoys a spot of psychogeography, a French situationist philosophy he engages in on P42

For more great articles go to cityam.com. For a digital version of The Magazine go to cityam.com/the-magazine

EDITORIAL TEAM:

Steve Dinneen Editor-in-chief Adam Bloodworth Deputy Editor Billy Breton Creative Director Chris Stopien Deputy Creative Director Andy Blackmore Picture Editor Alex Doak Watch Editor Adam Hay-Nicholls Motoring Editor Tom Matuszewski Illustrator Anna Moloney Books Editor

COMMERCIAL TEAM:

Harry Owen Chief Operating Officer Jeremy Slattery Commercial Director Nzima Ndangana Luxury & Direct Sales Manager

For sales enquiries contact commercial@cityam.com. City A.M. The Magazine is published by City A.M., St Magnus House, 3 Lower Thames St, EC3R 6HD. Some products and websites promoted in this magazine are owned and distributed by City A.M.’s parent company The Hut Group

6

THE FRAUGHT WORLD OF CELEBRITY INTERVIEWS

Setting up a celebrity interview is a long and complex dance. Each one you read – like those with Benedict Cumberbatch and Kiefer Sutherland in this issue – stands atop the corpses of 100 that didn’t work out. They involve fraught discussions between journalists, brands, celebrities and formidable publicists, each with wildly conflicting interests. It’s not unusual for email chains to spill into triple figures and include lists of extravagant stipulations (“Kelsey Grammar will walk out if you mention his ex wife!”). Usually, on the day, they go off without a hitch. Sometimes, however, they do not.

My interview with Henry Cavill, for instance, ended with me telling the event organiser to “f**k off” as I stormed out, Superman looking on with an expression somewhere between ‘shocked’ and ‘apologetic’.

That day, some time in 2016, had begun well enough. I arrived studiously early for my meeting with the Man of Steel, who had been pencilled in as the cover star for an issue of this magazine.

The interview was tied to the launch of a new handset by a Chinese mobile phone company, which Cavill was fronting. I was booked in for 30 minutes and had a long list of questions about his acting style and how his family’s ties to the armed forces might have influenced him. There was also an obligatory mention of the phone, which Cavill would inevitably answer with platitudes so predictable I could have written them in advance. That’s the game.

The venue was packed, with an influencer event unfolding in parallel to the junket, which saw journalists from around the world queuing for their slot. It was not well organised. People on Cavill’s team were stressed. At least one was in tears. My slot came and went. After an hour I was told I would not be getting 30 minutes; 20 would have to suffice. An hour later that 20 became 15, which became 10, which eventually became five. Three hours had gone by, over which time I had experienced all five stages of accepting one’s own death: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and, finally, acceptance.

Eventually I was called in. “You have four minutes,” said a Terrible Man from the phone company.

“You must be f*****g kidding,” I replied, reverting from ‘acceptance’ back to ‘anger’. “Interviews are not divisible into units of less than five minutes.”

“You’re on the clock,” said the Terrible Man. Cavill was sitting across from me, gigantic and beautiful, clad in a neat-fitting suit. “How do you prepare for your roles?” I

From interviewing Idris Elba on a dance floor to storming out on Henry Cavill, STEVE DINNEEN relives his biggest interview disasters

asked.“Well, I usually…” began Cavill. “No,” interrupted the man, “there’s only time for questions about the phone.”

“You must be f*****g kidding me,” I repeated, apoplectic that the universe would do this to me. The job of a journalist at this stage is, of course, to ignore the Terrible Man.

“What was your childhood like?” I continued. “Erm, well it was actually ver…” said a sheepish Cavill, unsure how to react.

The Terrible Man then jumped up and positioned himself between me and Cavill, splaying his arms in a star-shape in a futile attempt to block his massive bulk from my sight. I leaned around him: “Tell me about your father!”

The man positioned himself between me and Henry Cavill, splaying his arms in a star-shape

“Enough!” screamed the Terrible Man. I stormed out, a string of expletives trailing in my wake. And with that, my cover feature was dead. They later sent me a free phone to apologise, which I flogged on eBay for a few hundred quid, so it wasn’t a total disaster.

Another time I interviewed Idris Elba in a loud – very loud – Soho bar. I had scoped out an alcove where we could just about hear each other but Idris was having none of it. “Stand with me,” he instructed. Surrounded by people dancing, we had to huddle so close I could smell his aftershave. My dictaphone picked up about a third of the interview. I did write that one up but it wasn’t very good.

And don’t get me started on John Malkovich, who left a junket early after I had flown all the way to Los Angeles to speak to him. I ended up getting very drunk with a publicist who thumbed through her little black book and set me up for a chat the next morning with Billy Zane. I have never been so hungover conducting an interview but thankfully Zane was happy to get stuck into the bloody marys.

Why am I telling you all this? Mostly for the lolz, but also to pull back the curtain on the wild ride we go through to land a big interview. It’s a tough job but somebody’s godda do it.

8 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

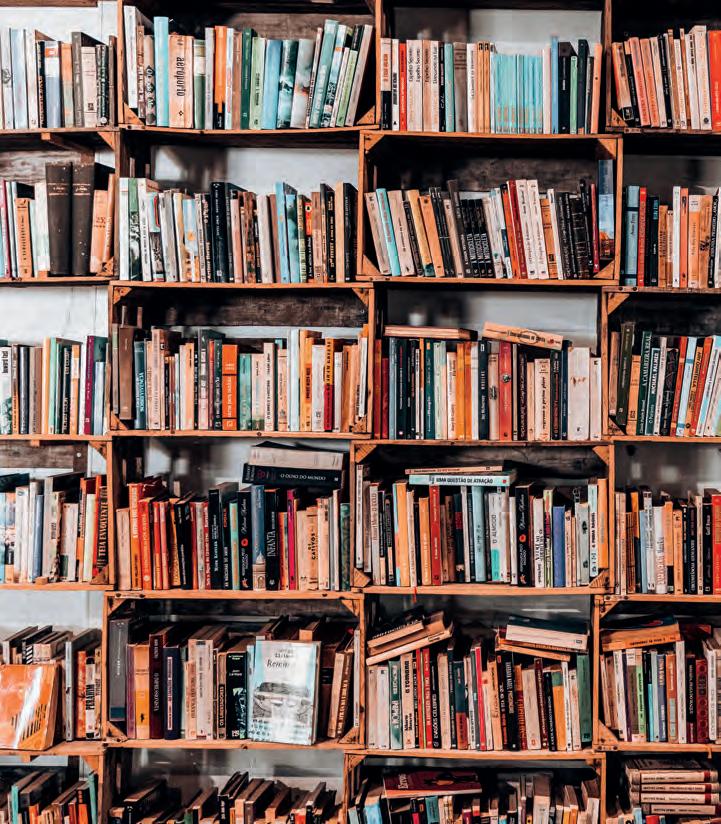

BOOK OFF!

Everyone has a book inside them,” Christopher Hitchens once quipped, “which is exactly where it should, I think, in most cases, remain”. He wasn’t wrong. There are too many books. They scatter the shelves of WH Smith, gathering dust. Top 10 celebrity bestsellers fill the walls of airports where tired eyes linger on tomes they will never read. Books are used as decoration: you can pay an interior designer to organise your collection by the colour of their spines or –even more heinously – with the spines facing inward. YouTubers shamelessly film themselves buying books with which they make bedside tables. The mighty book – a vessel of ideas – has been reduced to a

There are too many books, says LUCY KENNINGHAM Most are ill-conceived, unnecessary and harm the environment. It’s time to reassess what we print

decorative detail.

The world now contains over 145m different titles, with 1.4m more published each year. Up to 980,000 of these are self-published, largely egotistical ‘rich people’ projects, with at best a paltry three-figure readership. The deluge of titles dooms us to suffer from ever-worsening decision paralysis, which discourages the picking up of a book in the first place. Why does this matter? Isn’t the democratisation of publishing a good thing, sure to improve the quality of humanity’s overall literary output? Haven’t a share of books always been ‘bad’, their existence allowing good books to transcend the rest? Well, no. The proportion of bad books is completely out of whack. The bodies that are meant to curate them are failing us. It’s often

touted – by the kind of people who roll out JK Rowling’s several trips to publishers before her Harry Potter success – that publishing houses are too elitist. But most publishers consistently choose quantity over quality. They have lost sight of what makes a book valuable. Some, like the 2007 runaway success Wreck this Journal, are made explicitly to throw against a wall. That’s not a book, it’s a stress ball. And don’t get me started on What to do While you Poo.

Too often, publishers come across an article or a podcast or a meme or a tweet and, sensing an opportunity, think: zinger! Let’s turn it into a book! This is how Simples: The Life and Times of Aleksandr Orlov made its way to my door (my father brought it to me from Moscow… Airport). There is a relentless replication and extrapolation of one piece of content into as many forms as possible in a way that disrespects the art of literature. “Culture today is infecting everything with sameness,” wrote Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer in 1947. Publishing a book has become no more than a stud in a person’s CV, an adjunct to a Wikipedia page, an (unregulated) signal of expertise. Even in academia, publishing your PhD has become a mere accolade. One researcher admitted to me that she didn’t anticipate anyone would actually read her upcoming publication ‘Anatomy of an opposition: Anti-sectarian movements in Lebanon’ (in spite of its clear worthiness). It was simply to prove her credentials. Then there is the not negligible matter of the environment. In the UK alone more than 77m unsold books are destroyed each year. If they were on average 350 pages each, that would account for the destruction of 1.6m trees. In a study of 86,000 books published, around 60,000 sold no more than 20 copies, according to data collectors Nielsen Bookscan. That’s a pretty damning commentary on the surplus produced by the publishing industry. On top of all this, a 2011 survey found the average Brit owns 80 books they haven’t read and showed that 70 per cent of books in the average bookcase remain unopened. Four out of 10 of those questioned confessed that their works of literature were purely for display purposes. Where does that leave us? In lieu of a Soviet-style Goskomizdat – the State Committee on Publishing in the USSR –perhaps we could agree upon a moratorium on memoirs before said author hits the age of 80. It is time for reference books to cease physical publishing, too, given their short shelf life and the existence of a thing called the internet. We should reintroduce pamphlets as a matter of urgency. Books from Sadiq Khan’s take on air pollution, Breathe, to Greta Thunberg’s No One is Too Small to Make a Difference would benefit from a bite-sized format.

Then again, perhaps a new Goskomizdat wouldn’t be the worst thing. I bet, at peril of a gulag, no one would risk their freedom to publish What to do While you Poo.

10 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

Most of these books could be an article or a podcast or a tweet – please stop writing them

You may be haunted by memories of your grandmother’s liquor cabinet but vermouth is a forward-thinking drink that should feel like ‘an ice-pick in the neck’, says CARYS SHARKEY

Ifirst tried vermouth in Spain. There, the day, slowed by the sluggish intensity of heat, is jolted into cool night by aperitivo hour. Vermouth is served over ice with a simple garnish of orange or lemon. The red liquid borders on viscous, giving it a sticky intensity that refreshes like nothing else. The journalist Helen Rosner describes drinking vermouth in the throbbing summer as “a thrilling exercise in fighting fire with fire”.

Vermouth is a wine aromatised by an apothecary’s shop of herbs and fortified with additional alcohol. I like mine with an olive – a saline hit that leaves a perfect teardrop of fat skimming across the surface. But vermouth never really found its footing in London. With just three specialised bars – in Soho, Kings Cross and Nunhead – it’s unlikely you’ll stumble across it.

Much like our summer, the promise of a British vermouth craze has been marked by many false starts. The drink seems destined to fall between the cracks, partly because of its innately ‘inbetweenish’ nature: stronger than wine, weaker than spirits; better known as an ingredient in cocktails than in its own right. Vermouth has a disorientating placelessness: who is it for?

In Italy I’m told the only people who order it are over fifty or Spanish tourists, although if the German pavilion afterparty at the Venice Biennale is anything to go by, it’s still popular in Dusseldorf. Perhaps the issue is tradition. Where Italians are bound by selfflagellating observance of the ‘right way,’ UK producers are exploiting the creative opportunities presented by vermouth.

Still Wild is a Pembrokeshire vermouth company with an ethos rooted in foraging salt swept botanicals. It makes a sweet and dry vermouth from local ingredients including bog myrtle, rock samphire and sweet woodruff. Its founder, James Harrison-Allen, told me he tried 73 plants and herbs before settling on the perfect blend. “We can embrace it as an essentially new product in this country,” he says. “Whereas Italy is very stuck into tradition and heritage, here you can take the framework of the movement and be far more creative with it”. Guy Abrahams, founder of the award

WHO’S AFRAID OF DRINKING VERMOUTH?

winning London Vermouth Company, echoed these sentiments, saying the British vermouth market is “ripe for creativity”.

There are now dozens of UK producers making an often hyperlocal and varied spectrum of vermouths, some cloaked in the salty mists of the coast, others ripe with English gooseberries or replicating a hedgerow cosmos writ large.

Should you be ready to take the plunge, I would start by clearing out any accumulated dribs and drabs of syrupy vermouths that might be festering your liquor shelf. It’s time for a fresh start, a spring cleaning of prejudices.

Try bottles produced by Still Wild, Vault,

London Vermouth Company, The Aperitivo! Co, and Sussex based In the Loop (a maker spearheading the move to get ‘English Vermouth’ a designated and protected term). Drink your vermouth with olives and pork scratchings and pickled onion monster munch and Spanish pintxos (a selection of salty, oily snacks like iridescent anchovies and wafer thin crisps). As the summer wears on and concrete begins to radiate, embrace the British aperitivo hour. Most importantly, it must always be cold. As Michael Kaplan, the encyclopaedic founder of Edinburghbased Great British Vermouth, told me: it should be drunk like “an icepick in the back of the neck”.

12 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

Vermouth is a wine aromatised by an apothecary’s shop of herbs and fortified with additional alcohol

The race is on for green growth, net zero, and energy security.

At SSE, we’re investing right here, right now. We’re building the world’s largest offshore wind farm. We’re transforming the grid. And we’re delivering thousands of jobs.

Around 90% of our investments are in electricity networks and renewable energy. And, for those days when the wind isn’t blowing and the sun isn’t shining, we’re reducing emissions from the flexible back-up power we need today, to secure Britain’s energy future.

sse.com

WE

CHANGE WE’RE INVESTING IN HOMEGROWN ENERGY £20 BILLION ACTIONS, NOT AMBITIONS WILL SECURE OUR ENERGY FUTURE SSE’s £20.5bn five-year investment plan to 2027 expects to allocate ~54% into networks, ~34% into renewables, and ~12% into other businesses, including gas and low-carbon flexible generation technologies. In 22/23 SSE’s generation output was 60% non-renewable sources and 40% renewables. SSE is committed to being operationally net zero by 2050, measuring and reporting on its science-based carbon targets and aiming to cut the carbon intensity of the electricity it generates by 80% by 2030, from a 2017/18 baseline. Verify at sse.com/change

POWER

CHEF’S TABLE

Food writer and restaurateur RAVINDER BHOGAL interviews her friend NITIN SAWHNEY, the composer, producer, and multi-instrumentalist, at her restaurant Jikoni. Pictures by GRETEL ENSIGNIA

THE MEAL:

SOY KEEMA BUN, PINK PICKLED ONIONS CURED CHALK STREAM TROUT LA RATTE POTATOES, KIMCHI LABNEH, SAFFRON SHEERMAL

NITIN SAWHNEY: Hi Ravinder, how’s it going, are you in a good place?

RAVINDER BHOGAL: Yeah, I’m good! I’m having a year for me, after two pretty hectic years of book promotion. I’m taking a year to really find joy.

NS: Well that’s what your book, Comfort & Joy, is about! How’s that going?

RB: Comfort & Joy has done really well. I went to the States and did all the festivals in the UK so it was hectic but really joyful. The last book came out during the pandemic so there were no live events.

NS: You’ve had such a successful career as a writer as well as an amazing chef. That’s

Cooking is a very maternal thing. I didn’t go to cookery school, I was taught to cook by women who were taught to cook to nurture and nourish

what I’m full of admiration for, you’ve had these parallel careers and they compliment each other. Do you have a love for one over the other or do you feel they cross-fertilise?

RB: We’re quite similar in a way: you’re also multi hyphenate, you’re a polymath, you do so much, but I think the similarity in the writing and cooking is it’s about giving a service to someone. It’s about how you make someone feel when they read a piece you’ve written or eat a meal you’ve cooked. I think similarly you’re like that with music, ultimately you know it’s going to move someone in a certain way and I think there’s a joy in that, isn’t there?

NS: Yes, absolutely. I was talking to somebody about the neurology of music. The nucleus accumbens, the part of the brain which is the reward centre: it’s interesting in how that works with music and also the way it works with food. Your brain rewards you as well as your palette.

14 FOOD&DRINK

RB: It’s about the intention you put in when you’re creating a piece of music or cooking a dish. It’s a very maternal thing. I didn’t go to cookery school, I was taught to cook by women who were taught to cook to nurture and nourish their families. It’s an innate, deeply entrenched feeling. I always want to look after people, nurture people. With you recently when you were sick my instinct was to bring some food around.

NS: That was so kind of you!

RB: I run a restaurant and while it has to be commercial I really do it for the love. For the feeling it gives other people.

NS: That’s what I love about your food: it’s a synesthetic experience. It’s about memory, it’s about different senses being evoked. Were you ever conscious of that?

RB: I just think food is life and life is complicated. There are so many emotions when it comes to food. Recipes are like

When you bring cultures together, you create something that’s better than the sum of their parts. This is a form of soft-activism

stories with no endings – particularly the kind of food I cook, which is immigrant food. It’s constantly evolving. It’s an amazing way of telling stories about people and celebrating the similarities we have but also the differences.

The food that I cook is often a bit political. We have something like the prawn toast scotch egg, which I’ve always described as this bonny love child of a British scotch egg and a Chinese prawn toast. What we’re trying to say is that when you bring cultures together, you create something that’s better than the sum of their parts. This is also a form of soft-activism and it’s wonderful to see people use it, whether it’s through music or food or poetry, it’s a really powerful way of being active in the world.

NS: It’s interesting that you talk about stories. You studied literature and you’re a great writer but you have this awareness of narrative in the way the foods work together. You have to have that as a writer but also as a chef, which is fascinating.

15

Above left: A dish of Labneh with saffron sheermal at Jikoni; Above: Ravinder and Nitin at the restaurant

RB: It’s a gentle sort of storytelling. We are taking people on a journey when they come into the restaurant. I remember the first track we ever played on our first service was The Boatman from your album! I felt like I was about to go on this massive journey. It felt like crossing over, and that song is so beautiful. It feels like a lullaby. It was very calming to listen to as my first plate went out. I felt like I was crossing a river myself.

NS: I love that. The western concept of the ferryman represents somebody who takes you to a peaceful future, to destiny. I think there’s something poetic about that image, it’s something I find really inspiring, musically.

RB: I’ve grown up as a sikh and that representation of crossing over a river for us often means going from life to death. But I think in life you can have many little deaths and rebirths. You’re born a new person all the time, every time you go through something. For me that was disentangling myself from my past and having the courage to open a restaurant. You think about these themes of immigration and identity on your new album and that kind of diversity is what makes the world such an interesting place to be in.

NS: I’m a Booker Prize judge and it’s interesting for me how many books there are now focusing on the concept of cultural identity, looking at it from many perspectives. I keep thinking, is it because I’m especially aware of that subject? But it’s not: a lot of people are thinking about identity. It comes up in politics, it comes

up in culture, it comes up in schools. Identity is constantly a battleground, as well as a place for people to feel safe. That’s what I wanted to do with the album: create a safe space for people to express themselves. I always feel your restaurant Jikoni is a safe space.

RB: I always wanted it to be. People kept asking ‘Why did you do Jikoni? Why do you do the kind of food that you do?’

It was a subconscious thing for me because, as an East African Indian, British born, raised in London, I have so many identities. But I was being pigeon-holed. ‘You’re a brown girl, you must do Indian food.’ Throughout school and growing up there was this box you were supposed to fit into. I really struggled with that. I felt that I’d always lived in a sort of hinterland between who I was to my parents and who I was outside the home and who I really am. Jikoni is the place where I can express my multiple identities, my multiple tongues.

We have dishes on the menu that have Swahili names, Indian names, we don’t try to reduce them by saying, ‘It’s a chicken curry.’ We will call it by what it is, the kuku paka.

The thing I feel most proud of is that we have such an international crowd. Once on a table of 10, there was a Palestinian, an Egyptian, a Lebanese person, someone from Paris and all these people were saying, ‘Wow, this tastes like something my grandmother used to make.’ If they’re finding a sense of home at Jikoni, I feel like I’ve had a good day in the office.

l To book a table at Ravinder’s restaurant Jikoni go to jikonilondon.com; Comfort & Joy cookbook is available now; For more on Nitin Sawhney visit.nitinsawhney.com

16 FOOD&DRINK

Above: Nitin and Ravinder catching up; Below from top: Soy keema bun with pink pickled onions; cured chalk stream trout; la ratte potatoes with kimchi

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

THE RECIPES MY EX TAUGHT ME

Food plays an integral part in relationships – but what happens when they end? How I still find joy in the dishes my ex cooked

Ithink about my ex precisely twice a year: in the winter, when I make his annoyingly good sausage casserole, and in the summer, when I make his annoyingly good chicken salad. By all accounts, he turned out to be a bad apple, but I’ll give him one thing: he gifted me a love of cooking that far outlasted the relationship.

When he first referred to the “holy trinity” in our shared kitchen, I thought he was perhaps revealing his religious side. In fact, he was sweating celery, onion and carrot - the basis of many a good meal, he said - in a pan glazed with the fat from the sausages he’d just browned. For the extra flavour, you see? I did not see - because prior to meeting him, I could’ve burned boiling water. Our culinary experiences were worlds apart. Where he reached for fresh garlic, deftly dicing it with a knife, I would have tipped in dried granules. In his arsenal of spices he had the paprika, sage and cayenne needed for the dish, whereas I had contributed a single pot of Asda mixed herbs to our cupboard. He had the confidence to replace the cider in the sauce with apple juice because it was cheaper but arguably just as tasty, and the knowledge to simmer and reduce it by half for maximum punch. A can of tomatoes, the container swilled out with stock, and an hour later we’d

have a warm, comforting meal to counteract the freezing Manchester night.

That meal was the foundation on which I’ve since built a robust knowledge of one-pot cooking. It might sound simple to more sophisticated palates but lest we forget that a 20-something boy who can cook is a rare beast. I suspect he’d learned out of necessity, whereas I’d arrived at university having only graced the kitchen to eat the food presented to me by my mum. As a result, I’d had to ring home during freshers’ week to ask how to brown chicken.

Imagine, then, the revelation of learning to poach chicken in stock, garlic and thyme so that it was plump and juicy, and not a pile of charred nuggets in packet fajita mix. That instead of reaching for a shop-bought dressing, my ex whisked together mustard, oil and vinegar and drizzled it on warmed mixed beans and a side of rocket. If the way to a woman’s heart is through her stomach, it’s via a salad leaf better than iceberg lettuce.

That I still cook both dishes almost 15 years after we broke up, however, is not due to residual nostalgia. That has long since evaporated; it’s simply because they’re delicious. Do I think about him when I make them now? Only in the occasional abstract: oh, he taught me this one. In truth, I’ve now made these recipes more times solo than we ever did together. They’re mine now. If you’re asking me how it feels to eat my feelings, I’d say they were pretty tasty.

18 FOOD&DRINK

LAUREN POTTS

Breakfast or lunch for prospective members. Available throughout June, July, and August

ELEVATE YOUR DINING experience this

SUMMER

Indulge in a summer of gourmet delights at our exclusive club, where every meal is an event to remember. From June to August, enjoy a breakfast or lunch as our guest and discover why we are the city's premier dining destination.

Our club is a haven for those who cherish the finer things in life. Whether you seek a tranquil workspace, a refined se ing for business, or a serene retreat to unwind, our club offers the perfect ambiance. Don't miss this exclusive opportunity. Contact to secure your dining experience and the benefits of membership.

Reserve Your Spot Today

clubsales@tentrinitysquare.com

CONTACT

US

FRANKIE, BENNY AND ME

It was a childhood staple – now it’s a dying chain with a handful of sad restaurants. KYLE MACNEILL remenisces about the glory days of Frankie & Benny’s

My salad days did not involve much salad. They were instead filled with molten-hot dishes preceded by the disclaimer: “Please be careful, it’s really hot,” or ice-cold glasses piled vertiginously high with sugary things that towered above my gelled-up hair. And, almost always, I would devour these saucy and sweet extremities of temperature at Frankie & Benny’s, the Italian-American restaurant chain.

“Family: they’re the ones you can depend on,” Tony Soprano once said. But our family also depended on Frankie & Benny’s: for birthdays, celebration dinners and after-school surprises. My memories of it are tinted in a familiar shade of red: the crayons, the napkins, the sauces, the booths. And every visit ended with a cookie-and-ice-cream concoction so ludicrously sickly and diabolically fudgy that a dentist would rather pull their own teeth out with a sundae spoon than take on the challenge themselves.

Frankie’s wasn’t the only franchise in which I spent my childhood — Nando’s, TGI Fridays and Prezzo were all family favourites — but Frankie & Benny’s topped the lot. There’s something reassuring about the consistency of a chain restaurant, with an equally reassuring consistency to its gloopy sauces. We stuck to what we knew. But it turns out I knew a lot less about the duo behind Frankie & Benny’s than I imagined.

The story of Frankie & Benny’s, as it goes, begins exactly 100 years ago in 1924, when Frankie Giuliani left Sicily and moved to Little Italy in New York. After his parents built and opened their own restaurant, Frankie became friends with Benny at school. In 1953, the pair took over the family firm and the rest is history. Or fiction, actually. For years, I believed this tale, one that’s immortalised in every franchise of Frankie’s, through framed family photos and sepia-stained newspaper clippings.

But F&B’s didn’t begin in Little Italy; it was launched in Leicester. And it wasn’t opened by the slick,

suited-and-booted, rat-pack-styled duo of Frankie and Benny. Instead, it was founded in 1995 by The Restaurant Group (TRG), the earnestly-named conglomerate that has owned chains including Garfunkel’s, Chiquitos and Wagamama. I tried to speak to someone from TRG to find out how they happened upon this incredibly specific pair of fake Italians but nobody got back to me. Quickly expanding across the UK, the company opened its 100th restaurant in 2005 and became the kingpin of retail parks, dominating the spaces beside cinemas, bowling alleys and furniture stores.

But by the mid 2010s, the Italian-American dream of Frankie’s began to fade and profits began to spiral. After first blaming a rise in competition, TRG conceded that it was probably down to high prices and poor service. TRG threw spaghetti at the wall to see what stuck. Breakfast was positioned as the Big New Thing, rebranding efforts were attempted and the menu was changed again and again, featuring a revolving door of spin-off dishes. The chicken parmigiana, the new CEO noted with a sense of horror, had been replaced by chicken saltimbocca. An angry mob was forming. In a surreal twist of fate, a toddler was accidentally served alcohol not once but twice in the space of a few years. Perhaps they needed to block out the saltimbocca.

In 2016, 33 branches were shuttered. In 2019, 18 more flailing franchises were closed for good. Then, at the start of the pandemic, scores more were whacked. The conglomerate even opened a shortlived version of the chain called Frankie’s, stripped of the original’s charming decor and, most devastatingly, any mention of Benny.

Today the writing is very much on the wall. Late last year, following the closure of dozens more F&B’s, TRG announced it would sell the franchise to The Big Table, owners of Cafe Rouge and Bella Italia. TRG didn’t make a penny from the sale, instead paying The Big Table £7.5m to take the loss-making business off its hands. With just a few dozen restaurants left, it’s possible that

20 FOOD&DRINK

Frankie & Benny’s will soon disappear forever, melting away, like tears in ice cream.

To rub salt in the wounds, the fall from grace coincides with an Italian-American renaissance in the British food scene. Over the last few years, the likes of The Dover, Alley Cat and Grasso in London have created a new gang of grown-up meatball-andspaghetti restaurants with far slicker decor and fancier food than Frankie or Benny could ever whip up. In wider culture, too, the rise of the Mob Wife aesthetic and mass rewatching of The Sopranos would seem to be a golden opportunity. But Frankie & Benny’s – the commercial Godfather to these new Italian-American restaurants – is being left in the parmesan dust.

One of the remaining franchises is in Manchester’s Printworks centre. I head there on a weekday evening with my housemate, keen to try to relive the glory days of Italicised knickerbocker glories and Anglicised spaghetti bolognese. Taking a seat at one of its booths and slurping-up a syrupy, slightly-flat coke, I instantly feel at ease, nodding along to its playlist of crooners. Miles Davis and Sinatra are interspersed with Miley Cyrus, in an apparent effort to be a little more relevant. Regrettably, I don’t have the meatballs to ask for a crayon box. Just two other tables around us are populated, tucking into hefty

21

Above: Kyle out for a family dinner at Frankie & Benny’s some time in the early 2000s; Left: A now-vegan Kyle contemplating a forbidden sundae lll

burgers and a bottle of

The service is excellent and the decor is as fun as I remember, a kind of watered-down Scorsese film set. But when our food arrives, I realise my memories of eating here may be slightly warped. Either that, or it’s changed; because Frankie’s food, to be frank, is not great. This will, of course, come as absolutely no surprise to most people;

Frankie & Benny’s had never threatened to land itself a mention in the Michelin Guide. But, once upon a time, I did love the food. Did I have no taste?

Perhaps, it’s partly because I have changed. I’m now a bit vegan, so my housemate is entrusted with eating the dairy. Either way, my sugary and vinegary penne arrabbiata is less angry, more a

little irritated, mopped up with sad garlic bread. When the sundae comes, I do briefly consider giving up years of veganism to dive into its billowing, pillowy cloud of ice-cream and whippedcream, a godly combination. But the bronzed busts of Benny that decorate the restaurant stare me down. According to my housemate its sweetness is migraineinducing. When the bill arrives I realise that, while cheerful, it’s not even cheap: two pasta dishes, a side, two cokes and a sundae comes to well over £50.

Yet, for all its flaws, I leave with a full heart. For years, I have sneered at restaurant chains: tacky, bland outlets drained of any personality. There are, obviously, countless reasons to support independent restaurants and true Italian foodies would understandably see Frankie & Benny as the devil and the antichrist manifest. But there is a snobbiness at play, too. The last time I went to Frankie & Benny’s, on my first day at uni, I remember feeling embarrassed to be in one of its booths, like I had outgrown it.

TS Eliot’s Alfred Prufock said that he measured his life out in coffee spoons. I measured mine in sundae spoons

But what they can do is take you back to – as Frankie & Benny’s current slogan goes – The Home of Real Good Comfort Food. Sitting here in this ersatz gangster’s paradise, I realise I could be in the Frankie & Benny’s in Croydon where I celebrated my sister’s thirteenth birthday, or the one in Glasgow I went to for a package holiday kids club reunion decades ago. It’s true that, like the Frankie & Benny’s origin story, some of my own memories might be fiction. Was I really as happy as I remember? Did I really finish that sharing sundae by myself? Am I seeing this all through rosso-tinted glasses?

Either way, there is something irresistibly romantic about it. TS Eliot’s Alfred Prufock measured his life in coffee spoons. I measured mine in sundae spoons. Time doesn’t pass here, in this liminal space somewhere between Leicester and Little Italy; the sundaes are permanently frozen; Frankie and Benny are stuck in stasis on the walls; my childhood self remains sitting in one of those booths, smile stained red.

22 FOOD&DRINK

From top: A Frankie & Benny’s during its heyday in the early 2000s; The iconic menus, familiar to millions of diners; Kyle returning to the mythical restaurant of his childhood to be faced with a bowl of miserable pasta

wine.

Garden. Party. Racing.

30 JULY – 3 AUGUST

#GLORIOUS

THE MAN WITH THE SCRAN

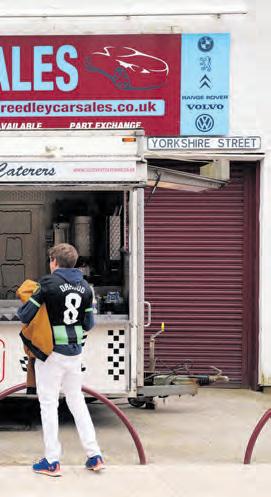

With almost 600,000 followers on X, FootyScran, which rates stadium food, has become an institution with influence over an entire industry. Words by CHRIS STOKEL-WALKER

24 FOOD&DRINK

Richie Howard, a palaeontologist from Merseyside who now works at the Natural History Museum as the curator of fossil arthropods and graptolites, had a great time watching Vissel Kobe defeat Cerezo Osaka 4-1 in a J-League football match last month. But it wasn’t the fast-flowing football or the injury time goal, slotted into the bottom left corner from just inside the 18-yard box by Taisei Miyashiro, that most grabbed Howard’s attention. It was the beef steak donburi and takoyaki (battered octopus balls) that stood out.

After slapping down 1,700 yen (£8.70) for the beef bowl, served over steamed rice with the batter balls on

Tom Sibley set up FootyScran after seeing a photograph of sausage and chips with curry sauce, served in half a hollowed-out bread roll

wooden sticks, Howard took photographs of the food and shared it on X (formerly Twitter). “Absolutely immaculate vibes in the away end of the Sakura Stadium,” he posted. “And the scran omg”. In the post, he tagged two accounts: the official J-League English language account, and @FootyScran. “I love FootyScran,” says Howard. “I really enjoy seeing the food around the world.”

He’s not the only one. Nearly 600,000 people follow FootyScran on X, with 40,000 more on Instagram. The profile is a documenter and enabler of a Damascene transformation in what people eat while watching football. This food revolution is a world away from the burnt sausage rolls, cremated pies, soggy chips, and questionable hot dogs that most football fans will remember from years gone by. Today, you’re as likely to get chicken katsu curry or bang bang noodles as you are a slightly grey burger. And it’s largely down to a single social media profile, run by an air conditioning installer living in the West Midlands.

Tom Sibley set up FootyScran in 2020 after seeing a photograph on social media of a portion of sausage and chips with curry sauce, served in half a hollowed-out bread roll, sold at Merthyr Town, a Welsh team playing in the seventh tier of the football league. FootyScran has gone on to capture the changing face of football stadium food – and along the way, make its own indelible impact on both on- and offline culture. Google search traffic for “scran” has increased significantly across the UK since 2020, a shift in part accounted for by the popularity of FootyScran. Sibley himself remained intriguingly elusive as I was writing this, acknowledging the messages I sent him trying to set up a chat before dropping off the face of the earth. But several football clubs were happy to talk about the impact of FootyScran.

One of the clubs that has upped its food offerings is Luton Town, who were relegated fromo the Premier League this year. The club contacted Raffaele Ruocco, a chicken shop entrepreneur, about bringing something new to the team’s stadium to match their standing in the top flight of football and their £10m refurbishment of the stadium. “They approached me last summer,” says Ruocco. “They had a concept of what they wanted. Being in the Premier League, they wanted to evolve the food.”

Ruocco now runs The Kenny Henny, whose BBQ honey glazed chicken burger with fries was featured on FootyScran in April. “We’re trying to offer something to the people that’s not your usual run of the mill boiled burger or nostalgic pie,” he says. A broader range of food is important, says Ruocco, because football stadia can’t be exempt from more general shifts and trends.

“Everywhere you go, people have upped their game. Even McDonald’s is fancier than it was.”

Howard says FootyScran fills a hole left by the closure of banterlicious TV show Soccer AM, which had been on a downward trend for a decade or more before its final

25

Clockwise from top left: Wolves fans await Slush Puppies at Molineux; Southampton fans eat hot dogs at St Mary’s; The Mystery Kitchen at Farnham FC; A food wagon at Burnley’s Turf Moor; An old-school shot of terraces at The Den, New Cross

SCRAN OR NO SCRAN? STADIUM FOOD ACROSS THE WORLD

£7

£4.20 – 82.4% SCRAN

episode last year. “I reckon plenty of football fans are hungry for lighthearted, daft and inoffensive football content,” he says, “especially given how grotesque the general discourse is with all the bedroom pundits.”

What makes FootyScran work is that it doesn’t name and shame or pillory bad food, instead letting the pictures do the talking. Users simply vote whether an item is “scran” or “no scran”. The account itself is studiously silent when sharing the photos submitted by its hundreds of thousands of followers.

But while FootyScran has incentivised some clubs to drastically improve their matchday food – Tottenham Hotspur is one club often singled out in ‘best of’ lists since its eponymous stadium opened in 2019 – others have not bought into the idea. “The food at Newcastle remains terrible,” says Charlotte Robson, a Newcastle United fan and host of the True Faith podcast. She says she looks on in envy at FootyScran’s feed: “It makes me

CHICKEN SATAY STICKS

MANDURAH CITY

£8.80 – 91% SCRAN

£2.10

SANDUÍCHE DE COSTELA

£4.20 – 82.4% SCRAN

£6.30 – 83.7% SCRAN

want to be a football tourist.”

One place many FootyScran followers have on their must-visit list is Farnham Town FC, a semi-professional club that won the Combined Counties Premier Division South last season. One of the club’s directors is Harry Hugo, who runs a London-based

Football fans are hungry for lighthearted, daft football content given how grotesque the general discourse is

social media marketing agency that works with Instagram, TikTok and YouTube creators; he knows the power of social media to drum up offline interest.

“At a non-league level the main drivers of revenue are food and drink,” he says. So when he became a director in mid-2022, Farnham Town introduced a mystery kitchen concept to matchdays: a food truck would serve a rotating range of Instagramready, exotic dishes developed by a professional chef, alongside the standard matchday fare. “We had this idea that if we created a different dish every week, we would have the ability to publicise ourselves on FootyScran every week. From a revenue perspective it’s a lot better for us to sell a meal of chicken and rice than it is to sell a burger for half the price.”

It’s strange to think that a miserable portion of sausage and chips served in a hollowed-out bread roll on a rainy afternoon in Merthyr Town changed the way we think about stadium food – but it’s a funny old game, innit?

26 FOOD&DRINK

VALENCIA FC

SERRANO HAM BAGUETTE

REDHILL FC

BATTERED SAUSAGE AND CHIPS

ATHLETICO PARANAENSE

NOTTINGHAM FOREST

PIZZA DOG

SCRAN

BANGKOK GLASS FC

– 68.9%

MIXED WORMS AND INSECTS

– 29.2% SCRAN

THE LAST SUPPER

Star of upcoming Netflix drama

Supacell ADELAYO ADEDAYO tells us what she would eat for her last meal on earth

My mum cooked in my household – she’s very, very good. I come from a Nigerian family and my cousins would go to my mum’s house just for jollof rice. Even when they see me today they’re like, “Do you have any of your mum’s jollof?” Even if I had some I’d say no: I have to ration it! It’s legendary in my family.

Our house was a place that people came together to eat. My mum’s friends and aunts and cousins and everyone would come round and we’d all eat these amazing Nigerian dishes.

We ate a lot of akara, a bean cake that you have for breakfast. And a lot of moin-moin, which is also made from beans but boiled in water – you can have it with garri, which is made from cassava flakes. And, of course, we had a lot of jollof rice, and my absolute favourite, pounded yam with stew and okra. I adore pounded yam: the consistency is just amazing. It’s

I’m going to have some apple crumble made by me because my apple crumble is the best there is

part of a group of foods called ‘swallow’ in Nigeria that you eat with your hands – you sort of roll it into a ball and dip it into the stew and okra.

I think some of my mum’s cooking prowess rubbed off on me. I’m not as amazing as she is but I do a good pounded yam, my jollof is pretty good and I make a really good ribeye or sirloin steak. To fit in with acting I’ve learned that I need to batch cook dinners for the week ahead, otherwise I’m just on the delivery apps, so on Saturday or Sunday I’ll make my food for the week ahead, portion it up and leave it in the fridge for when I get home. I’m quite disciplined in that way.

I also really, really love going out to eat. I ate at Ikoyi a while back and that was unbelievable but I’m actually pretty bad at trying new places – I love Hawksmoor: you just know it’s going to be great every time. And there’s this place called Seabird in Southwark that does this grilled sea bass that’s absolutely amazing.

So on to my dream meal, which is a bit all over the place if I’m honest. I’m kicking it off with a couple of Jersey oysters with tabasco because I wouldn’t want to go without having eaten them one last time. Then I’m getting some beef suya, which is a Nigerian small chop done on the grill. It’s served in old newspaper with onions and really hot chilli powder and tomatoes. And

I’m going to have some akara with it too.

Next I’m having steak tartare from a very specific place, this Japanese restaurant in Sao Paulo. Before I ate this for the first time I had a bit of a thing about uncooked meat but this was just incredible – I couldn’t believe how much flavour there was in it.

There was a raw egg yolk on top – stunning.

For my main I’m gonna have the grilled sea bass from Seabird and a steak from Hawksmoor and my mum’s jollof rice, all on the same plate. On the side there’s going to be pounded yam with okra and stew, and in the stew there’s going to be oxtail and goat. All my favourite things on the table together.

For dessert I’m having apple pie with strawberry ice cream on top. And I’m going to have some apple crumble made by me because my apple crumble is the best there is. And I’ll have a lime and blueberry cheesecake, also from Hawksmoor – I had this in Liverpool but they have taken it off the menu now so we’ll have to get them to make it for me especially.

I’ll wash it all down with a glass of Gosset champagne, a glass of ice, ice cold water – because nothing beats that when you’re eating – and a bottle of Peroni. After eating all that I just want to sit back with another beer. Lovely.

l Adelayo’s new show Supacell starts on Netflix this month

28 FOOD&DRINK

Adelayo Adedayo will star in superhero drama Supacell on Netflix this month

30 years

Serving the world’s best beef to your table

Our collection of restaurants in the UK has grown to twelve in London and eight regionally in Leeds, Manchester, Birmingham, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Liverpool, Newcastle and Cardiff.

gauchorestaurants.com | @gauchogroup Book Now

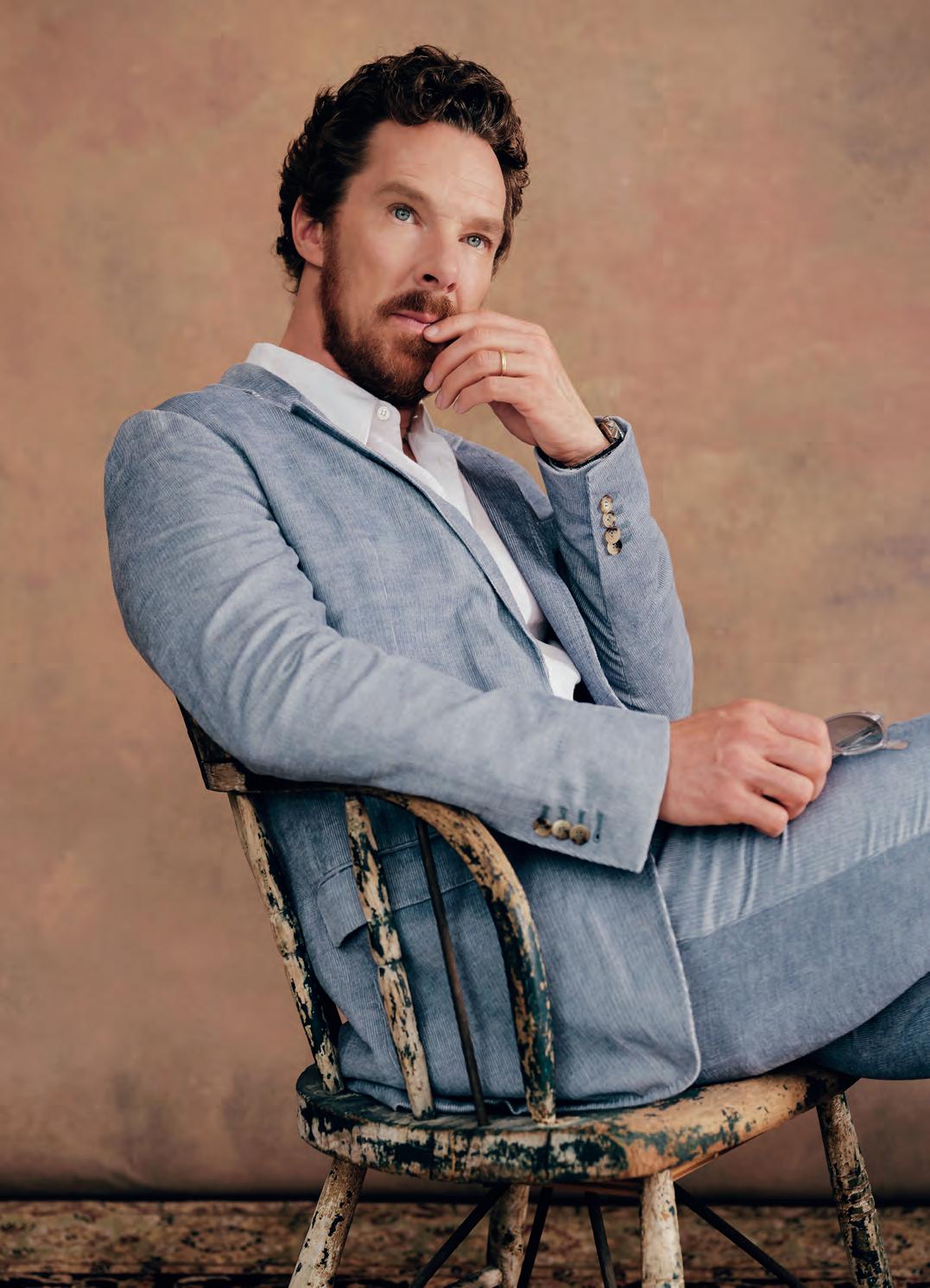

30 INTERVIEW

THE SERMON OF BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH

One of Britain’s finest actors tells ADAM BLOODWORTH about the ‘heaven’ of family life, going grey, and finding joy in the misery of his new role

I’m under strict instructions not to ask Benedict Cumberbatch anything personal. “He doesn’t do profiles,” I’m warned ahead of our interview. Arriving at the posh London hotel hosting the press interviews for his new six-part Netflix drama Eric, a publicist pulls me away from a pile of shiny pain au chocolats to whisper the rules once again, just to be sure.

It’s understandable. The 47-year-old had a stalker break into his garden last year, digging up plants and throwing them at his windows, while he was inside with his wife and three children.

Relaxing on a cream sofa in one of the suites, Cumberbatch is nothing like the highly-engineered publicity machine that precedes him. An empty wrapper in front of him suggests he has just demolished a Twix. He’s spoken about feeling old, but today he’s dressed more Gen Z: baggy cargo pants, white tee and a bracelet bearing multicoloured flowers. We’re settling into the first beats of conversation when he almost immediately breaks the rules. “As a parent, it’s a very hard watch,” he says of Eric, the new Netflix drama in which he plays an alcoholic father who mentally unravels when his son goes missing.

Cumberbatch seems to specialise in playing messed up men. Doctor Strange propelled him to the A-List and Sherlock first put him front-and-centre in the nation’s minds. He was also nominated for Academy Awards for his turns in The Power of the Dog and The Imitation Game, both of which feature complex, psychologically scarred men. But when I suggest this, he baulks. “I don’t think I’m drawn necessarily to darkness,” he says. “I’m drawn to a lot of light as well. I’ve played 115 characters over 20 plus years, so I’m going to be, every now and again, treading on something familiar. That’s just unavoidable.”

Having a conversation with Benedict Cumberbatch is a slightly dizzying experience. He speaks in a spiralling stream of consciousness, thoughts spilling out, sometimes fully formed, other times in fragments. He’ll start a sentence on one subject and by the time he’s finished it he’ll have launched into a whole new topic, having touched upon several others in the interim.

“But it’s important not to shy away from the darkness,” he continues. “Sometimes in culture we want to knock the edges off, or if there’s darkness it’s sort of cute and cool rather than speaking to the deeper well, the mass of grey, filling in the gaps between good and bad, likeable and unlikeable.”

In recent interviews Cumberbatch has deflected personal questions, but today he brings up home life multiple times, always unprompted. It’s late in the afternoon and he tells me he’s “sleep deprived,” so perhaps that’s it, but I suspect his openness is testament to him being a fine conversationalist, unwilling to swerve the necessary context if it can strengthen his answer. He feels he ought to set boundaries but when he gets into his flow, he struggles not to engage fully and earnestly. If anyone was born to deliver a sermon, it’s Benedict Cumberbatch.

He’s also a polymath, learning to play the banjo in The Power of the Dog and how to puppeteer in Eric. He executive produced Eric, as he did on The Power of the Dog, so when the acting stops, he doesn’t. If there’s a behind-the-camera issue he’ll try to “mull it over at the end of the day”.

In Eric he plays Vincent, an alcoholic father dealing with his own sense of parental abandonment when his nine-year-old son goes missing. What follows is a gripping drama about the unwinding of a man. It’s interspersed with fantasy when Vincent hallucinates a

31

Benedict made his acting debut in A Midsummer Night’s Dream as Titania, Queen of the Fairies, aged 12

32 INTERVIEW

From top: Benedict starring in new Netflix series Eric, opposite a giant, imagined monster; He has announced he will reprise the role of Doctor Strange in the Marvel Cinematic Universe

Sometimes in culture we want to knock the edges off darkness rather than speaking to the deeper well, the mass of grey, filling in the gaps between good and bad, likeable and unlikeable

giant monster from a fictional TV show, thinking it’s following him in real life. It’s a brilliantly strange, unwieldy set-up; reading lines to a seven-foot-tall puppet is surely his oddest gig yet.

“What a privilege for me to be able to have these deep dives into the very worst of it and hopefully come up with some kind of redemptive message,” he says. “In this case it’s about love. It’s about reconnecting and taking responsibility and moving away from the things that are damaging us, coming out of the darkness of that and into the light of a new beginning.” He circles back to the idea of never going back to a certain type of character, revising his answer: “That’s a story worth repeating a few times.”

Vincent, dreamed up by Abi Morgan –the writer behind The Iron Lady, Shame and Suffragette – is quite unlike anyone else. “It’s rare to bring something this complex into life,” Cumberbatch says. “He’s a functioning alcoholic who’s already had a mental collapse, from this unloved childhood where he was sectioned off as an embarrassment and pumped full of pills and no love. It would be hard to dredge that up every single day if it wasn’t already so brilliantly realised on the page.”

He says of his creative process: “It’s really about charting a lot of complex things, giving as wide a variety as possible for the edit with people you trust. And that means a lot of work, and creating enough to fail and fail better. You’re fuelled by so much that you can really, really feel free to let go.”

Did he let go, surrendering to the role? “Yeah, wonderful moments of freedom.” Then Cumberbatch goes into one of his knotty thought trails that tackles five or six different subjects as if it were one thought, his mind jumping from one thread to the next non-sequitur. “Fighting with yourself in some weird, clammy chalk pit, throwing yourself onto floors trampled on by 1,000 extras. Then being on a dance floor and dancing in sync with a giant seven foot tall puppet, jerking twistedly like a crazed person.”

If it takes time away from family the role has to be “worthwhile,” he says, especially as Eric involved filming in Budapest. “My family came there, but it was time away from home. There are other things to consider as well, but you know, that’s the primary concern when taking a job really.

Is this going to be interesting? He’s a hard character to lean into, but to play him was a source of joy.”

Cumberbatch lives in London with his wife, theatre director Sophie Hunter, and their three children, aged between four and eight. Born into a family of actors, his mother Wanda Ventham and father Timothy Charlton both had careers that began in the 1950s. He recalls growing up surrounded by the film and TV landscape and being backstage on sets.

Charlton saved for Cumberbatch’s “ludicrously expensive education” at Harrow school in north London, and today the actor says he works to make them proud. It was there he made his acting debut in A Midsummer Night’s Dream as Titania, Queen of the Fairies, aged 12. His professional debut came in 2000 on televised hospital drama Heartbeat; a year later he made his London stage debut. It was in 2004 that he first came to mass attention playing Stephen Hawking in the Stephen Moffat drama Hawking (Moffat went on to write Sherlock, the two remain close friends).

Cumberbatch has spoken about crippling self-doubt, and finds watching his work back “horrible”. The idea of the inner critic, something Cumberbatch has spoken about in the past, is explored through the show’s puppet, the titular Eric, who is “reflective of the monster in all of us,” he says.

“The damaging nature of an overbearing inner critic, slamming the blame and shame into someone to try and paralyse them. I think we have all experienced variants of that at some point in our lives. I’m 47 so I’ve lived a bit now, and it’s full on. Hopefully not as much as Vincent but it’s made real in this, it’s made external.”

More than once he circles back to the implication that, at 47, he is getting on. Does he feel old? “I think there are stages of your life when you really feel your age,” he says. “Having three young children is a reminder that time goes by very, very quickly. I haven’t been back to back [with work] – when you’re constantly doing stuff you don’t notice the gradual change. But when you’re sitting in the make-up mirror after a six month break you’re going ‘Wow, grey hair! There’s lines!’ It’s not, ‘Oh my god, I’m old,’ it’s ‘I’m old, that’s a fact’… I’m older, is what I should be saying. I’m not old, it’s fucking infuriating when people in their 30s say that. It’s just an acknowledgement that time is passing.”

The passing of time focuses the Londonborn actor on what’s truly important. “Leaving the work at work is so easy,” he says. “I’ve got three people at home who demand that immediate, present tense nowness and,” he pauses, slowing and softening his voice to a breathy whisper: “It’s heaven.” He goes into soft, quieter speech whenever he talks about his family: “It’s the greatest thing, and we have to give them a lot, we have to hold them and give them boundaries and all of the tenderness but let them be free to teach you. It’s an amazing, enthralling journey.”

“I only really pop out for these things,” he adds, referring to our interview, falling back into the sofa and hugging his left knee to his chest. “I’m not at every shoe store opening like I used to be as a young ‘un, when you have the energy and time and the curiosity.”

I think we have all experienced he damaging nature of an overbearing inner critic, slamming the blame to try and paralyse yourself

Before we go I get a glimpse of life behind the Benedict Cumberbatch curtain. He’s mid-sentence but rises up from the sofa and spins around to where his rep has already positioned his coat at the exact height of his outstretched hand. We say our thank yous, then he marches down the corridor. No one is prepared for him to leave but he’s got somewhere to go. Exec producer hat back on, he bowls over to a publicist for confirmation all the interviews have gone well, then he’s out of sight; it was too quick to tell whether it was the stairs or the lift. Benedict Cumberbatch was in control.

33

lll

A DAY WITH THE URBAN FOX RESCUE CREW

They have lived among us for millennia and form the basis of myths and legends. But despite humans co-habiting in cities with the urban fox, relations can be strained. ANDY SILVESTER joins former rocker and founder of The Fox Project for a day helping to rehabilitate injured vulpines. Pictures overleaf by ARIELLE DOMB

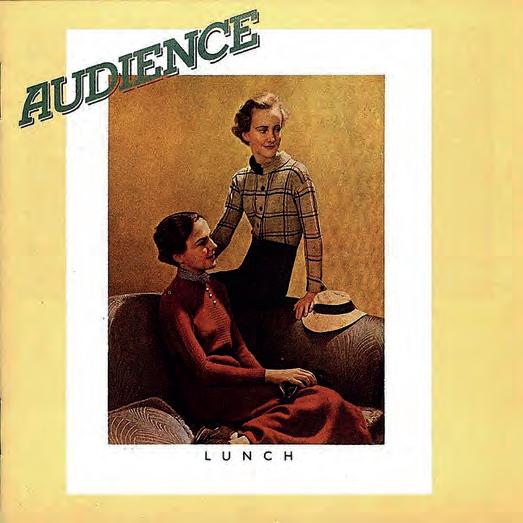

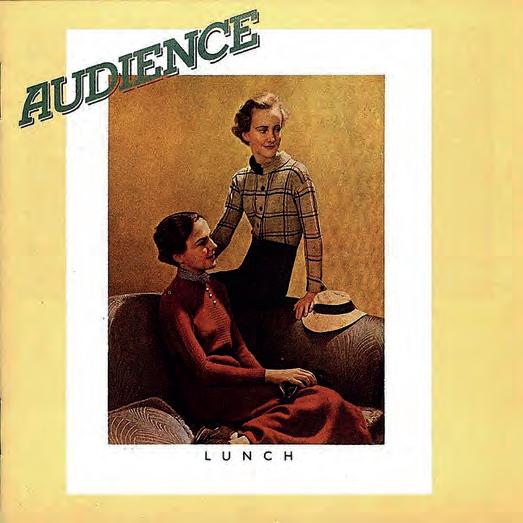

In October 1969, Trevor Williams, the lyricist and bassist for prog rock group Audience, took to the Lyceum stage to open for Led Zeppelin. A month later, at the same venue, he opened for Pink Floyd. After being snapped up by Genesis’ record label Charisma, Audience appeared to have a bright future ahead of them. But three years later, following a US tour with Rod Stewart that was considered by all involved to be very successful, the band split. Their last record, Lunch, was finished with the help of the Rolling Stones. They’re one of those groups that came tantalisingly close to megastardom, only to fade into relative obscurity. Today they maintain a cult following but average only around 6,000 monthly listeners on Spotify.

It is a glorious Friday morning in May when Trevor invites me into the cottage in Kent he shares with his wife Sue. I walk over a fox doormat, duck under a hanging fox ornament, and pass by lashings of foxadjacent material on my way to the kitchen, where Trevor is making a cup of tea. “The problem with being

34 FEATURE

so strongly associated with one thing,” he tells me, “is that everybody buys you stuff with it on.” You see, while Trevor may once have been on the same line-up as David Bowie and Black Sabbath (for the Atomic Sunrise festival of 1970), these days he is known for something quite different. These days he is the fox guy

At the bottom of his garden, about 20 yards from the kitchen, no fewer than 21 fox cubs, born just weeks ago, crawl over each other. Trevor swapped rock stardom for The Fox Project: a charity, of which he is the CEO, that rescues injured or young foxes, nurses them to health and independence, and releases them back to the wild. In 1992, The Fox Project took in three foxes. Last year, the hospital, ambulance and care home combined took in 1,400.

Scientists differ on whether the red fox – vulpes vulpes – is native to Britain. There is some evidence of foxes roaming through Warwickshire more than 135,000 years ago; the earliest specimen found anywhere was in

Hungary, dated sometime north of 1.8m years ago. The relationship between them and humans ranges from companionable – foxes have been found buried alongside humans in the middle east – to mythological, most notably in Japan, where the famed kitsune forms the basis of a thousand trickster stories.

They also serve as prey. Trevor met Sue, his wife of 36 years (“we didn’t get together for twelve years – he needed to grow up,” Sue chuckles), when they were hunt saboteurs. “It was the sense of injustice,” Trevor says. But disrupting hunts wasn’t enough: he wanted to set up an advice line, providing information on foxes that wasn’t from either the pro-hunt lobby nor the extreme anti-hunt campaigners. “There were myths and legends and misunderstandings and there really was nowhere else to go to.” That turned into something more substantial, located not on the green and blood-soaked lands of England’s historic counties but in south London.

There are around 300,000 foxes in the UK today, a good 10,000 of which live in London. That number has remained pretty stable. Urban environments, after all, suit these natural scavengers, providing them easy access to food. The fox population at large is resilient, and has shown an extraordinary ability to adapt.

Foxes began what we might call their ‘urban phase’ in the 1930s and 40s, exploding after the war into the burgeoning suburbs. Councils, faced with a problem they barely understood, didn’t have much power to deal with these new residents, and yet they were held responsible. Most decided to simply shoot them, especially when they edged into gardens or parks or hospitals. Bromley, on the border between London and Kent and now part of The Fox Project’s territory, once employed a fox control officer who blasted 300 in a year.

The problem, Trevor explains, is that culling foxes doesn’t even work. Clearly it’s not ideal for the fox but neither does it reduce their overall numbers, with a raft of scientific studies showing that culls only temporarily displace a population, sometimes for a matter of days.

35

lll

From left: There are 300,000 foxes in the UK, with around 10,000 of them living in London. Foxes began what we might call their ‘urban phase’ in the 1930s and 40s, exploding after the war into the burgeoning suburbs; The cover of Audience’s final album, Lunch, which was finished with a little help from the Rolling Stones

lll

A far more effective threat than guns or hounds is the car, which is responsible for as many as half of all fox deaths. Other dangers are less obvious. Netting is a particular problem, from goal nets in back gardens to protective netting around plants. Foxes get caught and panic, often tearing their flesh in an effort to get free. The well meaning but ill-informed might cut the netting to free the fox, but those wounds, when infected – which happens often – can turn very nasty indeed. The best thing to do is call the professionals.

lll

The Fox Project is pretty simple. The public see an ill fox or an abandoned cub and call the charity’s emergency line. From 9am to 9pm, every day, there are ‘fox ambulances’ doing the rounds. If there are too many calls, ‘fast responders’ are on hand to help. Unlike real ambulances, they invariably turn up quickly.

Sometimes, an ill fox will need to be trapped, in which case The Fox Project will work with a concerned homeowner to set up a regular food pattern, and then catch them in what amounts to a gigantic, humane, non-lethal mousetrap. Lost and ill cubs head to Trevor’s garden to bulk out, spending time with other cubs and forming familial bonds before heading to ‘foster’ gardens around the south east. Ill foxes – common ailments include mange, injury, and so on – head to the fox hospital in Paddock Wood, a ten minute drive away from Trevor’s place.

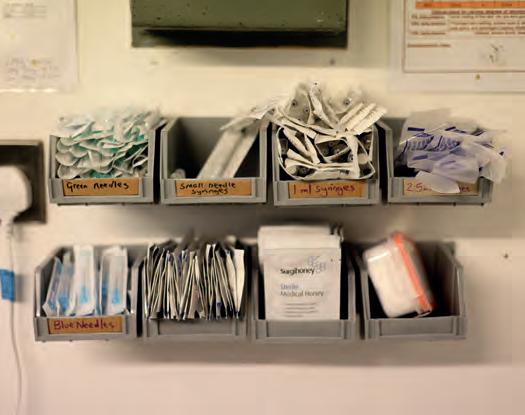

If the idea of a ‘fox hospital’ conjures images of a bucolic country farm, you’d be wrong. It’s in a nondescript industrial estate which, apart from the over-indexed amount of fox paraphernalia adorning the vehicles in the car park, does not scream ‘wildlife sanctuary’. Inside, however, is a command and control centre crossed with a field hospital: it is quite the operation. A volunteer who handles the phones and organises the logistics of the rescues waves as she takes

36 FEATURE

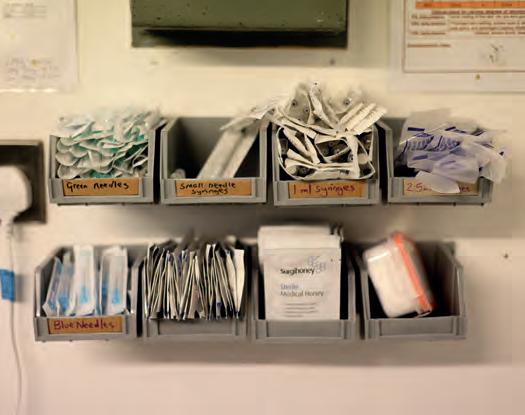

From top: A cub rescued by the Fox Project fattens up before being released back into the wild; Trevor Williams has found his Kent home filled with fox paraphanalia after founding the charity; Filing cabinets filled with syringes used to treat injured animals at the animal hospital

In a concrete world, there is something almost transgressive about our furry neighbours, wild dogs that live underground and come out at night to poke around our gardens

another call, looking every bit the emergency dispatcher.

In the main room, Nikki shows me the pens: I meet Geordie, who came in dazed and confused but is finally getting back to his full diet. The working theory is he was hit by a car but not hard enough to be injured, just a tad… concussed. Then there’s Dave, who was found with a massive abscess across his back; he’s recovering after having it lanced. JonJo is in a rougher state: he was bleeding badly when he was rescued, with staff thinking he’d crawled through barbed wire. He’s had stitches (and a shave) and today’s rather challenging task is to clean his wound, which involves covering his head with a towel and grabbing him by the scruff of his neck to administer the medicine. JonJo is less than thrilled by proceedings but just about gets the wash he needs. Elsewhere, Chelsea is getting back to health after being found hiding at the back of a shed, covered in often-fatal sarcoptic mange.

Others that come in are victims of what Trevor calls “misadventure.” Jaja, for instance, is not named after the controversial Star Wars character, but the jam jar he arrived in, having popped his head inside to see what remained. He was fine, and released back to the wild with a salutary lesson in the dangers of curiosity. Jaja’s moniker is unusual, says Trevor, with most rescued foxes being named after a nearby park or landmark.

“The one name we’ll never allow is Basil,” he says.

Today, at least, it seems those in the hospital’s care are on their way back to health. That is not always the case.

The ultimate aim is to be able to release the foxes back to the wild but the hospital’s success rate, Nikki tells me, is around 40 per cent. “When you’re putting them to sleep, you know you’re taking the pain away,” she says. Earlier in the day, Trevor, Sue and the various volunteers pottering about the cub sanctuary talked in hushed tones about “last Saturday.” More than a dozen foxes came in. Not all of them – some cubs, some adults – made it. How does Trevor deal with the loss? A sigh. “You have to be pragmatic,” he says. “And you have to move on, which you do, because more come in.”

Another sigh. “Now and again it gets you. You find yourself grieving a little bit. But… you’re just trying to give those that make it another go, a second chance.”

While few people appreciate their bins being torn up, there is an undeniable thrill to catching sight of a fox from the top floor of a night bus, or a bushy tail disappearing over the back fence late at night. One viral video, which did the rounds on Youtube last year, saw an urban fox wrangle not one, not two, but three chicken drumsticks into its mouth to take back to its den, before hopping over a four foot fence. Trevor tells a story of a lady in Greenhithe, near Dartford, a place not famed for its pastoral beauty. “She said seeing foxes

connected her to something, to the land. I’ve never forgotten that.” In a concrete world, there is something almost transgressive about our furry, mischievous neighbours, wild dogs that live underground and come out at night to poke around our gardens.

Sitting in his idyllic Kent garden, Trevor seems content. He may no longer be sharing a stage with some of the biggest bands ever to pick up a guitar, but he’s the picture of a man who has found something rewarding to do with his days. He dreams of opening a proper wildlife hospital, but says he has run into difficulties with land-banking developers, planning departments, and an ever-present shortage of cash. Still, he perseveres.

As I leave this secret haven for foxes, I remember something one of the volunteers told me. When cubs are deemed healthy enough to live on their own, and older foxes have recovered from their ailments, they’re released as close as possible to where they were found. Once free, the foxes instinctively bolt. But then, a few seconds later, they turn back to look at their human rescuers. The fox is probably checking it isn’t about to be caged again – but it’s tempting to think it’s a little thank you.

l The Fox Project is raising funds for new veterinary equipment. You can find out more at foxproject.org.uk

37

Trevor Williams once opened for Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin with his prog rock band Audience – he has since swapped the stage for his rescue charity. Here he enjoys a breather in his idyllic garden in Kent

lll lll

WASHED AWAY

Slipping on a swimming cap and goggles, LUCY KENNINGHAM dives into the strange, nostalgic and slightly grotty world of the municipal pool, a reassuring constant from New Cross to New Delhi

In the swimming pool we can both forget who we are and dream of becoming someone else,” writes former competitive swimmer and author Piotr Florczyk in his short study, Swimming Pool. And indeed, when I ask myself why I used to slouch down to the municipal pool, towel trailing behind me, practically every day one summer it was – I feel – a way of washing myself away.

It all starts with the aggressively utilitarian building you walk into. You push through a turnstile, venture down slippery, grotty steps into a dingy room. Shoes off, you abandon your clothes, jewellery and other detritus. In a murky puddle of water masquerading as a footbath, you cleanse your feet. With your face obscured by cap and goggles, you leave the tiled hallway for the cavern of the pool. You plunge in and the water hits you. Cold chlorine rushes up your nose and water seeps in through the gaps around your goggles as you find yourself submerged. You squint and shiver. You come up desperate for air. Then, like Jesus parting the Red Sea, you separate the water that enfolds you with scooped hands. Using strokes you first learnt as a child, you strike through the water. When you reach the end, you flip over and continue shuttling between two walls in a sunken pit filled with chemically-treated liquid, housed in a large, echoey building

full of gymmers and swimmers, showers, tiles and mops.

There is an intensity that’s integral to the act of lowering yourself into water and propelling yourself through it. If you don’t move, you’ll drown. Humans were not made to swim, so the very act is a rebellion against nature. We are not dolphins, nor sloths, who can apparently hold their breath for 40 minutes underwater.

The swimming pool is defiantly uncool. Nowhere is this more true than in sunny southern France, where I lived for one infernally hot and oppressive summer. Here anyone who wants to display their beach body, flirt, get a tan or bask with any other libidinous intention could simply cruise on the tram down to the beach. The pool, by contrast, is for swimming. In France, nearly everyone in the pool had some sort of flotation device or flippers. This gave fully grown adults the appearance of not being able to swim in a manner I found curiously un-French.

For a place where we undress and parade around with bare legs and arms, the public swimming pool is remarkably unsexy and unsexualised

For a place where we undress and parade around with bare legs and arms, the public swimming pool is remarkably unsexy and unsexualised. This is very much not the beach. Oldish, sometimes yellowing polyester (I’ll hold my hands up to this) prevails. It’s all Zoggs and Speedos (brands which, beguilingly, don’t even try to be cool). Perhaps this has something to do with what George Orwell described as the “naked

38 ESSAY

lll

democracy of the public swimming pool”.

In this regard, swimming is diametrically opposed to running, which has become an aspirational way to spend a weekend. This has been wholly unwelcome for veteran joggers like myself, who want no part in a fashion parade. But unless you’re charging down a hill in the middle of the Lake District, it’s hard to fully disconnect yourself from your surroundings.

Runners flaunt their gear: a branded cap, running belts, watches, socks, headphones, headbands, tights, laces, the newest neon carbon-plated shoes and heart-rate monitors. Brands are inextricably linked to running. Nike, Adidas, Saucony, New Balance, Hoka. Swimming is different. We wear our faded Zoggs costumes and ropey

old goggles. A few people track their swims on Strava but it’s mercifully rare even for fitness fanatics. The resulting map (a generous description) is simply too dull. There just ain’t much glamour in chlorine and the echoes of screaming kids. I think that’s why pools are so endearing. We are laid bare, equalised in a way that rarely happens anywhere else.

When I thought about going swimming for this article, I felt the same fear I used to feel each time I approached the French piscines. Perhaps you could call it the fear of exposure. Not only was I going to throw away the comforting consumerist individuality of my clothes, wipe my eyes of eyeliner and stuff my hair into a

There is something alluring about the municipal swimming pool, places steeped in childhood memory where we cast off all the physical markers we use to identify ourselves

nondescript swimming cap (in France, they are mandatory), worse still I would be without my headphones (at the time, I was very into Hot Chip due to the influence of my cousin’s boyfriend).

There would be no Huarache Lights or Over and Over to haze over my anxieties as they did for many of the other waking hours of my day. You have lost the soundtrack that distracts you from your life. In the pool, stripped of your identifying markers, you are forced to be alone with your thoughts.