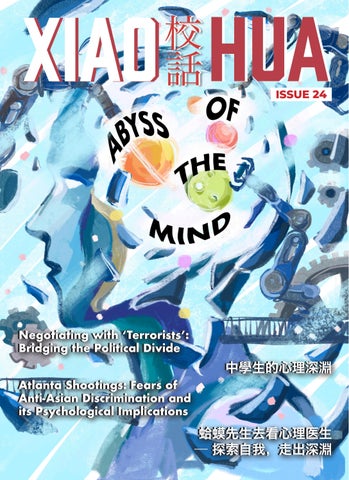

校 話

ISSUE 24

Negotiating Negotiating with with ‘Terrorists’: ‘Terrorists’: Bridging Bridging the the Political Political Divide Divide

中學生的心理深淵 中學生的心理深淵 Atlanta Atlanta Shootings: Shootings: Fears Fears of of Anti-Asian Anti-Asian Discrimination Discrimination and and its its Psychological Psychological Implications Implications

蛤蟆先生去看心理医生 蛤蟆先生去看心理医生 — — 探索自我,走出深淵 探索自我,走出深淵 校話

期刊 24

1