XLVI | 46 MISCELLANY

Miscellany is the College of Charleston’s student-produced literary and arts journal, founded in 1980 by poet Paul Allen and his student, John Aiello. Miscellany is dedicated to showcasing the creative writing and visual art of the College of Charleston’s undergraduates as well as undergraduates across the nation. Miscellany’s staff of students invites all undergraduates to submit their work for consideration each year. Miscellany strives to be a publication of inclusion and integrity.

All submissions are read and reviewed anonymously. The ideas and opinions expressed therein do not necessarily reflect those of Miscellany or the College of Charleston.

Miscellany is published each semester and uses one time printing rights, after which all rights revert back to the author. Miscellany XLVI, printed by Sun Coast Press, is set in Times New Roman.

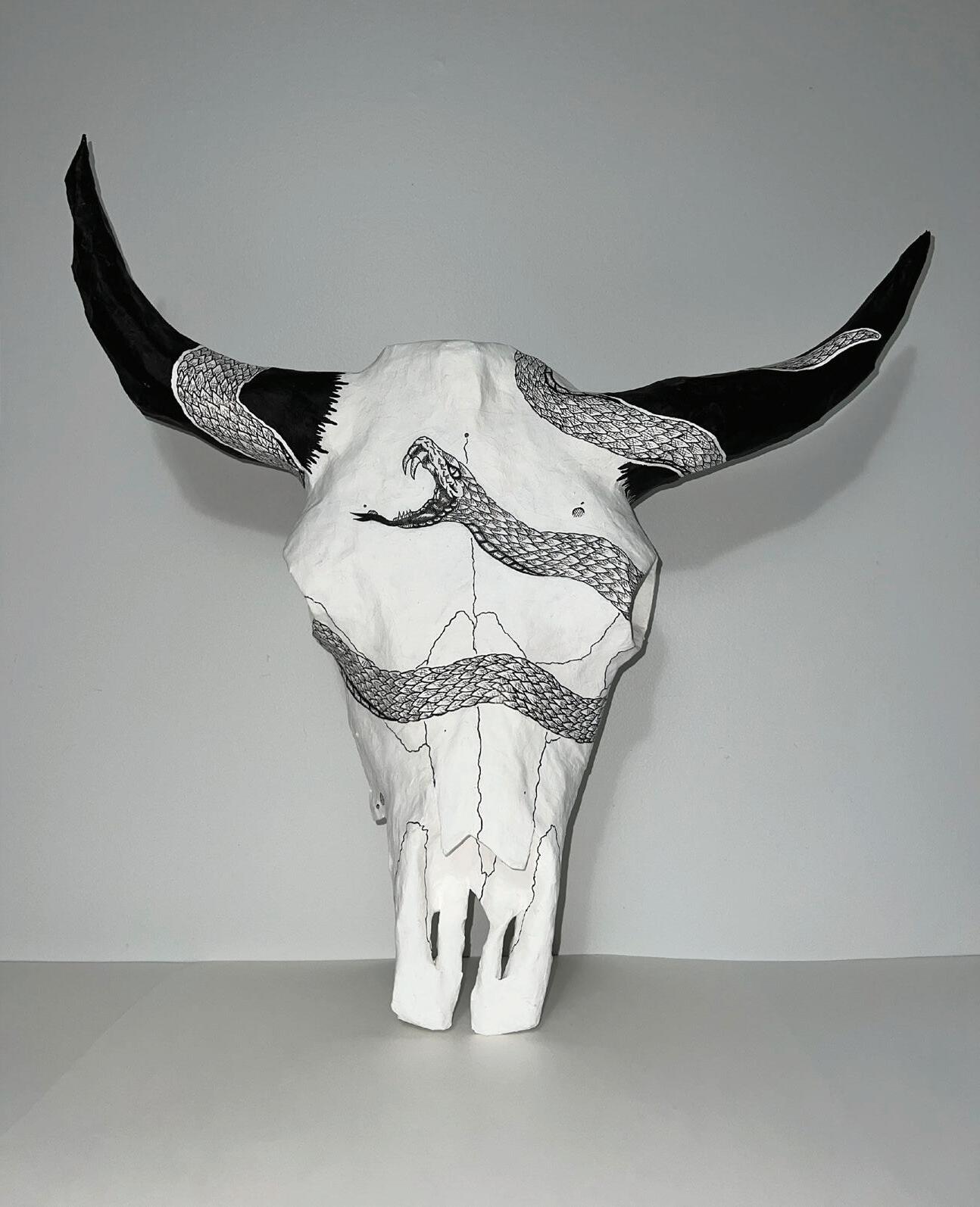

Cover Art:

Marquis

by Camila Carrillo-Maquina Digital Collage/Photography

COLLEGE OF CHARLESTON MISCELLANY ISSUE 46 | XLVI 2024 STAFF

Editor-In-Chief

Michael Stein

Managing Editor

Addison Ware

Staff Readers

Abbey Lute

Brynn Dybik

Eden Shames

Inés Carrillo-Marquina

JJ Murray

Katherine O’Shields

Kaitlyn Steffke

Madden Tolley

Marley Leventis

Mika Olufemi

Mila Lawson

Sam Barnhart

Table of Poetry q

Maggie Davis......................................

Madden Tolley.......................................

Half Past Five LAKAOIS

William Smith.........................................

Benny Cauthen.................................

Eden Shames..........

Homeland

American Guzzle A Half Dozen Shells to Share with My Ex Lovers Bottle your Body

Benny Cauthen..............................

American Disco Ball

Emilio Cabral..........................................

Blakesley Rhett....................................

Hanwen Zhang.....................................

Alix Averitt............................

El Cuco

The Election

Rocket Man

Where Have all the Children Gone? A Moment in Smoke

Camila Carrillo-Marquina..........................

Alberca

Cumple

Rebecca Maude........................................

PJ Gartin.............................................

Spring Tulips

Hothouse Mischief

Camila Carrillo-Marquina..........................

Alyssa Giorgino........................................

Chicos

Sunbleached

Alix Averitt.................................................

Rebecca Maude....................................

Alix Averitt................................................ Prose q

Leg Room

Figures of a Mess

Gozalandia

Contents Interview q

A$iah Mae (they/she) is a Black, non-binary Southern poet, humorist and cultural worker with roots in Georgia, South and North Carolina.They are currently serving as the Second Poet Laureate of Charleston, SC.

Be a part of history. Submit to Miscellany.

Letter from the Editor:

Dear Reader,

Thank you for being a part of our journal. Our goal, as always, is to showcase the best art available from undergraduate students across the U.S. We are proud to say that this year we had more than 600 student submissions representing more than 20 colleges and universities.

I am undeniably grateful for this journal, for Cistern Yard Media, and for the College of Charleston English Department. As I prepare to graduate and leave this poercelain city, I know that I am leaving the journal in good hands.

Addison Ware, thank you for being my Managing Editor and now my successor. I want each and every reader to know that this journal would cease to exist without Addison.

To our staff readers: you have read through endless submissions, so I thank you for both your patience and for your patience with me Y’all are the real brains in this operation.

To the artists out there, Miscellany XLVII is officially accepting submissions! For more information on submissions, visit: cofcmiscellany.substack.com

And to you, Reader:

I deeply appreciate you picking up our journal. It has been a labor of love. I hope you enjoy it.

Michael Stein Editor-in-Chief

Half Past Five Maggie Davis

I will set the table by myself. The corners will catch gingham linen, the chargers will sit slightly askew, and the candles will only be lit once. I’ll use twine to tie the napkins, fresh flowers will wilt in a dry vase, and I’ll forget which side the silver goes on.

But I’ll still serve salty-sweet corn pudding and a chicken trussed with the same twine. A side of greens glazed in garlic and honey, bread and butter from the Polish grocery, and I’ll have a cobbler in the oven, just in time.

I will serve my own plate, foregoing manners in solitude. The chicken is rested, ripe enough for blunt nails to rip baked skin. Leaving me with a leg large enough to gnash with gnarled teeth, taking bites too big for my body. Thyme slows, stuck to my cheek, and I let nothing get by me— molars cracking marrow open. Tongue wiping bone-made troughs clean, softened sponge sucked empty, and cartilage caught in my gums.

I will eat beyond full. And I’ll let the cobbler burn just past enjoyment.

Where Have All The Children Gone?

Alix Averitt Photography / Collage

Alix Averitt A Moment in Smoke Photography

LAKAOIS Madden Tolley

I cut my veins and gathered them into a bouquet. A grotesque display of my adoration. Arteries tied neatly in a ribbon. My body stands in front of yours, uninhabited.

Receive this offering, my love. It is all I have. Take it. Show no one. Accept this advertisement of my tender sameness. Unchanged sublimity.

My heart– rip it with your hands, don’t cut it, taste it with every sense. And while your soul, amorphous yet concrete, burns a hole through my pocket, I ask you to either love me or devour me entirely or is it all the same– to love and to butcher?

How many of you have been in love? I don’t need a show of hands. But what would you give if not skin and bones?

Blood and innards forming a love letter.

Signed, The Nauseating Dance of Affection.

El Cuco

Emilio Cabral

Doña Fita has lived in her son’s apartment for the last six months. Her room is closest to the bathroom and farthest from the door. It belonged to her daughterin-law. Doña Fita spends an hour daily burning sage to cleanse twenty years’ worth of memories from the room’s walls. The smoke doesn’t mix well with the humidity seeping through the cracks in the windowsill—a constant presence in League City, Texas.

The apartment is half the size of her house in Santo Domingo. It looks out over a strip mall parking lot and a broken-down taco truck that sells ninety-nine-cent taquitos on Fridays. On her worst days, she imagines it’s the cart her favorite chicharron vendor wheeled across her former neighborhood, catching teenagers running La Lope de Vega in the afternoons and the adults walking down Calle P on their way home from work in the evening. The smell of fried meat was a comfort in Santo Domingo. Here, it turns her stomach.

But her son came here, her grandson was born here, and so she’ll die here. There’s nothing she wouldn’t give up for her family. Her daughter-in-law never understood the gravity of that.

Doña Fita only leaves the apartment to shop at the Dominican market in Seabrook. The stress the twenty-minute drive puts on her back and eyes is too high a price for the market’s discolored plantains and expired yucca, but she’s grateful for anything in this landscape of fusion restaurants, tanning salons, gated communities, and highways that feels real. Sometimes, she lingers for hours, breathing in the produce as she watches the heat radiate off the concrete buildings outside.

She rolls her window down and rotates Spanish radio stations on the drive home. BNat Radio, KLOL Mega 101 FM, KHVU-FM 91.7, MAS Radio. They play a mix of the traditional merengue, salsa, and cumbia she loves, and reggaeton she recognizes from the muffled lyrics coming from her grandson’s bedroom at night.

It’s noon by the time Doña Fita returns to the apartment. The mailman is parked in her spot. There’s an open spot behind him, but she puts her car in park and waits. It’s the principle of the thing.

Five minutes pass. The mailman emerges from the apartment building, envelopes clutched in his hand. He sees her and waves with his entire body, like they are life-long friends.

“Sorry about that,” he drawls. “Give me a minute, and I’ll be out of your hair.”

Doña Fita doesn’t respond. She tries not to speak English if she can help

it. Her son is embarrassed by how her Caribbean accent elongates vowels and distorts consonants. As if it’s her fault her tongue is not deft enough to master the American rise-falling pattern and propensity for clipping the end of every word or sentence— there’s always a better place to be.

“Actually,” the mailman continues, holding the envelopes up to the window of Doña Fita’s car. “Do you live here? I was supposed to drop off some mail, but my key must be defective because the mailbox wouldn’t open. And it doesn’t look like anyone’s home.”

Her eyesight has faded in her old age, but Doña Fita recognizes the name— printed in a neat, serif font—immediately. How could she not? She picked it out herself.

“He is my son,” she says.

“When will he be back?”

“He is working. I will take it.”

“I’m afraid I can’t give it to you, ma’am,” the mailman says, slowing the words down. “It’s not your mail.”

He thinks Doña Fita doesn’t understand him. But it isn’t his English she can’t comprehend. It’s the assumption he can deny her ownership of part of her son. She birthed him, raised him, and forced herself to relinquish him only for her daughter-inlaw to return him in the end. There’s no stronger claim than motherhood.

“Mine,” she says.

The mailman threatens fines and investigations but hands the envelopes over anyway. He stalks to his car and reverses out of the parking lot. Doña Fita waits until the rattle of his car’s failing engine fades before pulling in.

She opens her son’s mail as she walks up the stairs. The usual offenders are present—water bill, property tax bill, Telemundo subscription—but there is also an envelope in a cool shade of cerulean blue. Its weight is alien in her hands.

Her son will be gone for hours—he’s replaced her daughter-in-law with double shifts and overtime pay—but as an extra precaution, she takes the envelope into her room and locks the door. Its delicate skin rips easily beneath her fingers. When all the scraps have fallen, she’s left holding a letter written on thick stationery.

The looping script is in English. So Doña Fita lifts her reading glasses from the chain around her neck and slides them up her nose. She fought her son at last month’s optometrist appointment, arguing the tortoiseshell frames accentuated her crow’s feet, but she’s grateful for them now.

Even so, her progress is minimal. For every word she understands there are two she recognizes but can’t place. It reminds her of the summer her son attempted to improve her English. Newly minted American passport in hand, the wrist of her then three-year-old grandson in the other, he said it was too expensive to fly from Houston to Santo Domingo annually. If she learned English, moved to the States, and petitioned for resident status, she’d save him hundreds of dollars.

EMILIO CABRAL

Other mothers would’ve slapped him. If she were two decades younger, Doña Fita would’ve considered it. But she’d lived long enough not to be surprised at the ease with which her son had learned American audacity. In the past five years alone, she’d watched various neighbors—men and women she had worked with, danced beside, attended the weddings of—pack their lives into cardboard boxes and ship them across the ocean. It was never their idea, of course. But their children thought it was best, and wasn’t it better to see the world than walk the streets they’d known all their lives?

Doña Fita humored her son and studied subject-verb agreements, but when it came time to book a plane ticket and fill out her VISA application, she refused. Instead, she asked him why her daughter-in-law hadn’t made the trip. If her distaste for Santo Domingo’s smog and heavy traffic, the stray dogs and cats roaming the streets, was strong enough to keep her away from her three-year-old son for months.

“Tenía que trabajar, mamá,” her son said. “La empresa no le da mucho tiempo libre, ya lo sabes.”

“Sé que no me ha visitado desde tu luna de miel. No me llama ni me manda fotos de mi nieto. Ella es la razón por la que ya no vas a visitar, ¿no?”

“She works so hard,” he said, wielding the English like a weapon. “I can’t ask her to drop everything because you want her to visit more. Besides, you’ve never liked her.”

The following morning, he called a cab to the airport and sequestered her grandson inside. She stood on the street in her threadbare robe and watched the car drive away until it was nothing more than a speck at the end of the road, swallowed by the rows of houses on either side.

She lay in bed for days afterward. Not only had she lost her son, but she’d been robbed of the opportunity to be a part of her grandson’s life. To teach him how to cook her favorite Dominican dishes: sopa de mondongo, mofongo, queso frito, moro de guandules. All because of an American woman who couldn’t be bothered to do it herself.

Doña Fita is a quarter of the way through the letter when her son’s name appears for the first time. Her grandson’s name sits in the middle of the following sentence of what, even with her limited English, she understands is an attempt at reconciliation. Her daughter-in-law’s name is signed at the bottom. But what the letter doesn’t include is a mention of the months and months of arguing. Nor is there a line dedicated to her abrupt exit and staunch refusal to sign the divorce papers she herself requested.

It was during the worst of the fighting that Doña Fita’s son called her for the first time in fifteen years. She wanted to be angry with him. But he wouldn’t stop crying long enough for her to get a word in edgewise. It was unnerving more than anything. He hadn’t cried in front of her since childhood, since she was responsible for magically healing any skinned knee and twisted ankle. His tears still elicited the same ache in her chest, but she couldn’t comfort him. He was no longer her responsibility.

He asked her to talk to her grandson while he returned to his crumbling mar-

riage. She told him that the boy most likely didn’t remember who she was, but he’d already been replaced with a hesitant voice, rough with the after-effects of puberty.

“¿Abuela?”

“¿Cómo estás, mi nieto?”

“Estoy bien, ¿y tú?”

His Spanish was accented, learned from a textbook, but it brought a smile to her face nonetheless. She would take any proof her son hadn’t deferred to her daughterin-law at every opportunity. And through her grandson’s fumbling, incorrect conjugations, there was genuine affection. One that reminded her of her son before he left for America and never truly came back.

So, while the urge to burn the letter is rooted in her desire to protect her son from the woman who broke him, it’s also rooted in the need to care for the grandson she accepted responsibility for that day.

Doña Fita kneels and digs her chipped nails beneath the loose floorboard at the foot of her bed. The wood creaks as she forces it upward. Her passport, wedding ring, and a photo of her late husband lay between dust bunnies, rat droppings, and dried puddles of arsenic. She slides the letter in beside them. Dust billows into her face. She coughs, wincing at the resounding thud of the floorboard falling into place. Somewhere in the apartment, her grandson cries her name.

Her hips groan in protest as she scrambles to her feet and shuffles to her bedroom door. In her preoccupation with the letter, she’d ignored the possibility of her grandson skipping his daily trip to the civic center a few blocks away.

“Abuela,” he says, voice muffled by the door. “¿Estás bien?”

“Estaba moviendo la cómoda. Las piernas hacían más ruido del que pensaba.”

“No debes mover los muebles solo. Podrías hacerte daño. Déjame entrar, y puedo ayudarte.”

It’s ironic, the role reversal. Most nights, Doña Fita sits outside his door, listening for the telltale sound of him opening the window and clambering down the fire escape. She would’ve punished her son back in Santo Domingo. But with her grandson, she merely stays up until she hears him come home. Her cherry blossom perfume lingers outside his room each morning, yet he’s never broached the subject. He doesn’t need to.

“Ya basta,” she says, glancing at her hiding place before opening the door. “Voy a hacer una tacita de café, ¿Quieres?”

Her grandson may be more American than Domincian—mas gringo que nada—but he can’t resist her coffee. While other women deploy aphrodisiacs purchased from department store catalogs, her weapons of choice have always been freshly ground coffee beans. She inherited the mindset from her mother. Her father’s drunken rages were always quieted by a cup of cafe con leche.

The Moka pot sits in the kitchen sink. As Doña Fita prepares it, her grandson jumps onto the countertop, bare legs swinging.

EMILIO CABRAL

Camila Carrillo-Marquina Alberca

Photography / Collage

His easy, unhurried movements—evidence of his naivete—grate. They’re holdovers from a childhood that never required anything from him. Her daughter-in-law coddled him from the moment he was born. When she first arrived, the stuffed animals, video games, and action figures bought for him over the years were strewn across the apartment. She spent a month packing them in garbage bags for her son to take to a donation center. Her grandson fought her on it, but he couldn’t justify keeping any of it without admitting to his attempt to hold on to his mother.

If Doña Fita had thought he was strong enough to handle it, she would’ve told him the gifts were nothing but a scared woman’s attempt to simulate a love she didn’t feel. But he and her son were not ready then, and they aren’t now. They’d welcome her daughter-in-law with open arms if they read the letter. The pain they’ve endured since she left would fade to the back of their minds because it has not diminished their love for her.

Doña Fita watched her mother go through it decades earlier. Each time her father came home from the bar, footsteps laden with the weight of the beers he’d drunk, her mother banished her to her room and went to greet him. What followed was always the same: a heated argument, crying, the sound of something being thrown across the room and shattering against the wall. Doña Fita could time the exact moment of impact, counting down the seconds from the safety of her bedsheets.

Afterward, her mother would knock until she untangled herself from the covers and opened the door. No matter how often she saw it, the sight of the mosaic of purple-green bruises along her mother’s neck and arms—the darkest of them in the shape of thick, meaty hands—always brought tears to her eyes

Her mother never told her the truth of where the bruises came from. Even when she was a teenager and her father’s drunken gaze began tracking her, too. Instead, she would tuck Doña Fita back into bed and tell her the story of El Cuco. A ghoul in the shape of a faceless man, he was said to take up residence beneath the beds of children, causing nightmares until he eventually stole them away to the underworld.

“A veces,” her mother said. “Ataca a las madres porque estamos protegiendo a un niño que él quiere. Así que prométeme que nunca saldrás de esta habitación cuando te diga que te escondas. Prométemelo.”

A thin cloud of steam races from the Moka pot’s lid. The metal screams as Doña Fita leans over to look inside. The coffee is a rich, maple-colored brown. Satisfied, she turns off the stove. Her grandson crosses the kitchen and slips on an oven mitt to help her lift the pot. She goes to brush him off but decides any obvious need to return to her room as quickly as possible would only prompt more questions.

“¿Que tal te fue hoy?” she says. “¿Te quedaste aquí?

“El centro de convenciones se está volviendo aburrido. Solo voy porque papá quiere que salgo más de la casa.”

He’s lying. Doña Fita has seen the pamphlet in his bag, and the searches on the derelict computer in the living room. Whatever he’s learning at the civic center seems

EMILIO CABRAL

to be integral to the person he’s becoming. But like the midnight stakeouts, reading the pamphlets, translating paragraphs on same-sex attraction and cities where men can be their authentic selves, is as far she’ll go. It’s a conversation he should have with his father. She’s a protector. She can’t protect him from himself.

She pulls two mugs from the sink and pours them each a cup of coffee. He thanks her and begins a story she only partially understands. A minute in, a hissing in her left ear punctuates the cadence of his sentences. She waits for him to give some sign he hears the noise too, but he continues his monologue uninterrupted. Eventually, he leaves, citing an important phone call with a friend. When he disappears into his room, she turns to check the stove. The dials are all turned off, and no orange-blue flames lick at the Moka pot’s underbelly.

But the hissing doesn’t stop. It’s no doubt a figment of her imagination. A result of the stress she is under combined with the old wounds the letter beneath her floorboards has opened. Yet her mind drifts to the stories of El Cuco her mother told her all the same.

She returns to her bedroom to escape the noise. The floorboards scald her bare feet. The windowsill glistens with condensation.

She turns on her ceiling fan. It hums to life. She settles herself on the edge of her bed and lifts the copy of Cien Años de Soledad from her bedside table.

It belonged to her mother. Notes and messages are tucked into the margins, as if the book was always intended to make its way into her hands. They detail the years her mother suffered her father’s abuse, and the small moments of joy interspersed throughout.

Doña Fita took years to come to terms with her mother’s silence; her self-imposed isolation. It seemed counter-productive to leave the battered parts of oneself within the pages of a secondhand book. It wasn’t until she married her husband, birthed her son, developed stretch marks on her stomach and hips, and delivered her mother’s eulogy, that she began to understand.

Her mother’s trauma will be lost to time as the book’s pages rip and decay. She transcribed her story of pain and suffering in between printed sentences, converting it into one footnote amongst dozens. Doña Fita can read them and be granted insight, not a burden, because the words are a confirmation of what she’s always known—a rare moment of vulnerability from a stubborn woman—and nothing more.

However, her mother’s slanted handwriting can’t block out the memory of her daughter-in-law’s letter. It sits in its tomb beneath her bed, mocking her. And try as she might, she can’t dispel the notion that perhaps it’s not where she left it at all.

Pulling at the ends of her hair, she kneels and uproots the floorboard. The letter hasn’t moved. This time, as she lets the floorboard fall into place, she lays back in relief.

With the anxious voices in the back of her mind satisfied, she reopens her book. But her eyelids droop with each page she turns. While she respects what Márquez

did for her mother and Spanish literature, she is a woman of action. He was a writer consumed by subtext and entangled stories. She hopes her grandson will have better role models to emulate one day.

Just as her eyes close, and her grip on the book slackens, the sound of fingernails scrapping against the divots in the room’s paneled walls jolts her awake. But looking around the room, she finds nothing except the portraits of Santo Domingo she brought from the Dominican Republic.

Like the hissing Moka pot, the fingernails could easily be related to stress. Or a large insect may have flown in through the gaps in the windowsill. Yet no matter how religiously she repeats these theories to herself, it does not keep her from imagining El Cuco clawing his way toward her inch by inch as the scrapping echoes around her on all sides.

Doña Fita throws her book to the ground and hobbles to the kitchen. Whatever strength propelled her earlier has deserted her now. Her arthritic joints crackle and pop, and the scar on her shoulder—the result of a teenage motorcycle accident—twinges in pain.

European Starlings screech at her through the kitchen window. A handful of colonies called Santo Domingo home, but they are everywhere here. An infestation she’s begged her son countless times to address. She starts another batch of coffee to drown them out, but her hands won’t stop shaking. She remembers how her mother’s hands shook when she made coffee for her father, desperately hoping she’d finish before he arrived stinking of alcohol and urine.

Doña Fita’s grandson shouts that he’s running to the corner store. He asks if she needs anything. She doesn’t answer. It doesn’t matter. He’s gone before his voice has stopped echoing off the walls.

But though he’s gone, his footsteps remain. Hard and insistent, as if he’s still in the apartment. Abandoning the Moka pot, Doña Fita opens his bedroom door. It’s empty save for the contents of his backpack, which are laid out neatly across his bed: sweets, pamphlets, a statuette of baby Jesus.

The statuette tugs at a memory on the edge of her consciousness, but she abandons it in favor of her bedroom. The footsteps have changed during her lap of the apartment. Now sharp and pointed like the high heels her daughter-in-law wore as she swept down the aisle to the tune of Etta James’ “At Last.” No one had known the perfect bride floating past them would realize she loved her husband but not the reality of marriage; the quiet moments after the guests departed and left the young couple to fend for themselves. She wanted a child. She did not want to be a mother.

Sweat drips down Doña Fita’s nose, staining the floorboard beneath her. She lifts it for the third time. As it clatters to the floor, she pulls the letter from its resting place.

Unlike the copy of Cien Años de Soledad, the letter is not something she can bury. Any memory of her daughter-in-law will whisper throughout the apartment, cor-

EMILIO CABRAL

rupting her attempt to protect her family. To exorcise her daughter-in-law from the building permanently, she must dispose of the letter entirely.

She brings the letter to where the Moka pot glows red-hot. She grabs the oven mitt and lifts the pot as the stove rattles and shakes from below. She sets the pot on the counter, eyes watering from the smoke billowing from the burning linoleum. Two seconds is all the time she gives herself to breathe before thrusting the letter into the fire with her opposite hand.

The letter curls in on itself as the fire consumes it. Doña Fita cracks open the window and leans her head outside, gasping for air. The Starlings have flown away, and the only footsteps in her ears are from the rubber soles of her son’s workboots as he walks toward the building from his car. She lifts her hand to wave to him and catches the scent of beef from the taco truck. For the first time since she arrived, the smell is comforting.

EL CUCO

Cumple Camila Carrillo-Marquina Photography / Collage

Spring Tulips

Rebecca Maude Oil on Gesso Board

Homeland William Smith

What do you know of five o’clock morning birds of driving through the dawn tuned into The Pogues singing of Irish sovereignty of breaking through the fog of a sleeping dirt road guiding you to conversations on cliff’s edge watching the chaotic pattern of a seasick shoreline

Blue collar jackets holding Dunkin’ cups and spitting on the ground smoking a too early cigarette

They are there with you showing off their new surf craft that will turn them from hard men to ballerinas dancing on the water

The Election Blakesley Rhett

It was one of the hottest days of the summer in the town of Liberty. The harsh July sun beat down on the fourth of the month, forcing all the residents to seek shelter from the blistering heat indoors. The schoolchildren retreated inside from their break. Those returning from the market took solace in neighbor’s homes and even the cattle had resorted to finding comfort laying in shady spots under trees.

It seemed that only Arthur Washington didn’t get the memo. Instead, he chose to stand outside on the edge of his porch, his hands resting against the railing as he stared off into the nearby fields. Even dressed in a sleek black suit, the sun beating down on his back and sweat pooling at his hairline, he didn’t seem to mind.

His mind was far away, focused on the upcoming town mayoral election. He had against all odds made his way to the final debate, winning votes over seasoned politicians and well-known faces in the town, and where, in a few hours he would be going up against the current mayor, Donnie Franklin.

“Artie?”

Arthur felt a comforting hand on his shoulder and on instinct raised his own palm to lay atop it. It stayed there for a moment, while Arthur took a final scan of the horizon before he finally turned to face his wife.

Marie Washington was always a sight for sore eyes in Arthur’s mind. She stood on the porch, her curly red hair pulled back with a blue bow that matched the fabric of her dress. The dress she was wearing she had recently made, specifically for the day’s events, hugged her growing stomach lightly as she subconsciously placed a hand over it.

“Are you okay?”

Arthur nodded absentmindedly at his wife’s words, his mind already jumping to the speech he would have to give before the start of the debate. It seemed that all that filled his mind these days was the upcoming election.

Marie waited a few moments for a response before Arthur spoke up, his eyes trailing over his wife who looked as beautiful as the day he had married her. Tthey had joined union last spring by the old cherry tree at the edge of town. Marie was the best of him, the best of any people he had met on his travels, the best of anyone in the town of Liberty by a long shot. She was far too good for him and that made him what some would call a lucky man, and for what he had put her through over the past election season, he would call a guilty one.

“Just thinking about this afternoon.” Arthur said, that faraway feeling in his voice that sounded as though he was sleepwalking. It was a sound that had become

familiar to Marie over the past few months, ever since Arthur had decided to put his name on the ballot box, an act that shook the town and Marie herself.

Marie, ever trying to be supportive of her husband’s endeavors, offered what she intended to be an understanding nod.

“You are going do great, Artie. I just know it.”

Harriet Dobbs, Marie’s mother, had always taught her not to lie, had filled her with the fear that God was watching and if Harriet caught her telling fibs she would take Marie to the kitchen and fill her mouth with soap to wash the sin away. But Harriet was long gone, and even though Marie tasted the all too familiar taste of bubbles in her cheeks, she pressed a smile onto her face.

Arthur returned her smile, though it didn’t quite reach his eyes. It was a smile that he typically reserved for political functions, all teeth and no joy.

“But Artie,” Marie found herself saying, Arthur halting from where he had been turning back to look towards the fields, “You know you don’t have to do this right? I don’t expect you, no one expects you too.”

She paused, collecting her thoughts and finally producing, “Miller wouldn’t expect you to do this. Any of this.”

Arthur paused, an unreadable look on his face. Marie longed for the days in which Arthur wore his heart on his sleeve, always laughed, and wasn’t afraid to speak whatever came to his mind. The days in which he wasn’t afraid to tell the truth, the days when he was young, free, and not hardened by his political goals.

“We best start heading out, Marie.”

Arthur stated, his eyes scanning over his wife, almost like he was looking through her as he moved past her and through the thin wire door that led into the kitchen, leaving Marie alone with nothing but the quiet fields for a false sense of comfort.

qWhen the sun was directly up in the middle of the sky, the whole town of Liberty was gathered in the small town square, sandwiched between the cracked fountain that only sprouted water two months out of twelve and the town general store which sampled a wide variety of taffy flavors. The children raced through the crowd, dodging legs and closed umbrellas, pleased to be excused halfway through the school day as their parents called after them, scolding them for dirtying their Sunday best. Only the nicest clothes were allowed on Election Day, one of the most important days akin to the First Day of Spring and Easter.

The town had been counting down until the big day, for it had been the talk of the town between sermons and over lunches for the past few months. Everyone knew the importance of the event and while the majority of people arrived early, the sheriff still continued to make his rounds to all the residences in the town. He started with the Kennedy house, the farthest field on the edge of town, and worked his way

inward towards the Square, checking to make sure that everyone was in attendance for the event. The only of the one hundred and fourteen residents of the town who was not required to attend was Old Johnson James who was laying with a collapsed lung in the infirmary. He had been placed with a small golden bell and was instructed to ring in an emergency since the doctor and the two nurses would be away from the building and in the Square. Even Miss Lancaster, who was bound to a wheelchair at the ripe age of ninety-six had made an appearance, and was currently sitting under the shade of the bank’s covered patio.

As Arthur and Marie strolled into the square, her arm tucked securely with his, they were stopped multiple times by citizens of the town who were showing support for Arthur.

“Miller would sure be proud, Artie.”

“Donnie sure wishes he was as charismatic as you.”

“When you win you stop by Ma’s you hear? We made a pie just to celebrate.”

Marie tried to make herself as small as possible as Arthur shook hands, a polite smile on her face as she held one hand carefully over her bump. As she watched Arthur beam his teeth so wide it almost looked painful, she wished for the old days in which Artie reserved his real smile, when his nose crinkled and his eyebrows pushed together, only for her.

A small wooden structure sat directly by the fountain. It used to only have been brought out twice a year, once during the Election and the other to hold the town’s Yule tree in the wintertime. After a while it became too much of a hassle to move and was now kept in the Square year round. An old box with a rusty lock sat on top of a small table placed upon the structure which held all the materials required for the event to begin.

Off to the side of the structure, standing around the perimeter stood the two mayoral candidates with their families by their side. Arthur, standing with Marie and their growing child, and Donnie, standing with his wife, Mrs. Franklin and their five year old twins, Samuel and Sarah. Ms. Grinner stood between the two as she shuffled some papers in her hand. As head of the school she stood in as the emcee of the Election when the current Mayor was running themselves.

“Alright,” Ms. Grinner called, her voice loud and scratchy from years of instructing children. She kept a careful eye on the sun’s position.

“It’s almost time. You two gentlemen both know the rules, correct?”

The two men nodded, they had read the rules that had been inscribed in the Town Hall wall and had been witness to many prior Elections themselves. Mrs. Franklin called at Samuel to stop opening and closing the umbrella he was holding and for Sarah to stop tugging at her pigtail braids.

“In four minutes you will go onstage and I will introduce you both. You will each get two minutes for your final statements. Then we will begin the vote. You have three minutes and twenty four seconds to prepare.”

Once Ms. Ginner finished her statement, Arthur carefully led Marie by her wrist a few feet away to the other side of the fountain, giving them the illusion of privacy.

Arthur gave his wife a smile, that faraway look in his eyes still there, “Marie, you know you’re my best girl, my other half, the mother of my child.” The hand that was not holding Marie’s fell to her stomach, pausing to feel if their child would make themself known.

“I love you.”

“Artie,”

Marie felt her eyes begin to water. She had been trying to shield her crying these past few months from Arthur, waiting until he was asleep or hiding it behind her dishtowel,

“I love you too, I really do. Ever since I saw you. And if you love me, if you love our baby, please please don’t do this.”

Arthur’s smile fell as he stayed quiet, letting Marie cry out, “Please! If you lose, God! I don’t know what I’ll do! I’ll be all alone.” Her hands quickly raised to either side of Arthur’s face to make him look her in the eyes,

“Miller wouldn’t want you to do this! I know that, you know that. I know he was your brother, that you were close-”

“Washington!” Ms. Grinner called and Arthur glanced back to see both the woman and Donnie standing on the steps to the platform.

“-but, he would want you to stay. Stay with me!”

Arthur looked down at his wife who was currently wailing in his arms, his pregnant love who was currently pulling at the fabric of his ironed button down insisting he stay and he knew that he would have to make a choice. But his mind was already made up.

“Marie,” Arthur spoke softly over her sobs, “I love you, you know I love you. I love you and our family. Which is why I have to do this.” As carefully as he could, which was quite difficult as Marie was flailing, Arthur removed Marie’s hands from his body and stepped towards the stage, moving behind Donnie as he crossed up the steps.

Marie fell to her knees, clutching her stomach for comfort, ignoring Mrs. Franklin coming to embrace and shush her as she watched her husband walk up the steps. Watched as he walked away from here, walked away from his life.

The buzzing from the crowd fell silent enough that a pin could be heard as Ms. Grinner and the two men took the small stage. Ms. Grinner situated herself behind the middle of the table, the rusting box directly in front of her with the two men on opposite sides of the table, facing out to the crowd.

“Citizens of Liberty,” Ms. Grinner began, not needing to look down at the papers in her hand as she had been giving this speech for the past seventeen years, “We are gathered here on the fourth of the month to perform the time-honored tradition of

BLAKESLEY RHETT

electing our new mayor. We will begin with a brief statement from each of our contenders.” Through her small eyeglasses she glanced over to Arthur, “Mr. Washington as the newcomer, per tradition, will go first.”

Arthur felt all eyes in the Square turn to him, he who was standing on the stage in a jacket that was a bit too big in his arms that had once belonged to his father, he who lived on the edge of town and had done the unthinkable of leaving the town at the age of seventeen, who had returned to scorned looks and hushed whispers. He who against all odds had won over the people and made his way to the Election.

He knew his speech by heart, had spent days bent over the pages writing and tweaking like a madman and repeating the words in his head as he walked to the grocer, tended the weeds in his garden, and while he brushed his teeth.

He knew the words back and front, the amount of commas and when to breathe penciled in his mind, and yet all he could think of was his brother. Miller.

“When I was seventeen, I left the town of Liberty.” He found himself speaking, trying not to focus on the people in the square who shifted uncomfortably at the mention of crossing the town lines. “I was a young man with a dream, a dream to find somewhere that was right for me. I had been seduced by stories of grandeur that told me the only place I would be able to find myself was out there, in the big wide world. I missed a lot of things in those years, many Summer Solstices and the burying of my dear mother, I missed the unveiling of the new silo in town and many Elections. One that included my own brother.”

He took a breath.

“Miller Washington was a complicated man. He was a bit too loud, could never sit still in Church, hated apples and loved oranges. But he loved this town, he loved it with his whole heart. He loved Liberty and was willing to risk it all for the town we all love and share. He was willing to die for Liberty and he did.”

Arthur thought of when he first arrived back in town, after he had received a call from Mr. Banks, who ran the funeral home told him that as Miller’s only remaining kin he had to be the one to decide what to do with the body. He packed up and drove thirteen hours back to town that same night.

“Some have suggested,” Arthur continued, trying not to think about the image of Miller with the hole in his head, “that the only reason I decided to run for Mayor was because of my brother, because he had run himself, and maybe that’s right. But I know, from being out there, from being out in the world, that what we have here, it’s special. Take it from a man who ran from it, but Liberty is the best place to be, maybe the closest thing on Earth to Paradise. It’s a town we need to preserve and care for, it’s a town I love, a town we all love. A town that is worth risking everything for.”

He found himself casting a glance towards Marie, who was still on the ground and looking at him with her weepy brown eyes, “A town I am more than willing to die for.”

As he stepped back, he didn’t hear the applauding and cheering, he didn’t hear the screams of praise that went on so long that Ms. Ginner had to silence them. He didn’t hear the announcement that it was now Donnie’s turn and the speech he gave and the polite clapping followed after.

He knew that if he was still out there, still in the cities filled with the heathens of those outside Liberty that he would have already won. It didn’t work like that though in Liberty. They followed tradition, they did what they had been doing since the early years of the town, they did it the right way.

Ms. Ginner nodded to signal the clapping to fall silent.

“Thank you gentlemen, now we will move onto the final voting of this Election.”

She produced a small, rusted key from the pocket of her dress, holding it up to the crowd who watched intently as she placed it into the lock of the old box, turning the key before opening the lid. She glanced down briefly to make sure all the materials were inside before stepping a few feet back, pocketing the key again.

“As per tradition, the current Mayor may pick first.”

Ms. Ginner nodded towards Donnie.

“Mayor Franklin.”

The crowd fell silent as Donnie approached the box, reaching his hand in. He paused for a moment, his hand still in the box before he pulled it out, a silver object clutched within.

A small handgun. The same one they had been using for as long as anyone within the town had been alive.

“Mr. Washington.” Ms. Ginner motioned towards Arthur as Donnie stepped back.

Arthur approached the box carefully, the wooden boards creaking under his feet. He tried to imagine what Miller had been feeling in this moment last year, when he had taken those same faithful steps.

Once he reached the end of the table, Arthur looked inside. There was only one object in there and he clasped his hand around it, pulling out the twin sister to the handgun Donnie was currently holding.

“As you all know,” Ms. Grinner addressed both the crowd and the two men on stage, “one of these guns is loaded with blanks. The other with real bullets.” She moved her eyes between Arthur and Donnie, “On my count, you will each fire one shot towards the other contestant. Whoever remains standing will be the Mayor of the town of Liberty.”

It felt at that moment, that all of the town was holding their breath, the only sounds for miles being the sound of the spectators opening their black umbrellas in an effort to protect their clothes. Even Marie’s sobs had stopped momentarily as everyone’s eyes glued to the stage.

Ms. Ginner took turns looking between the two men,

BLAKESLEY RHETT

“Are you ready?”

“Yes.”

“Yes.”

“On my count now. One.”

For Marie and their baby, Arthur thought, the cool metal feeling unusual in his hand.

“Two.”

For Miller. Arthur tried to imagine what his brother had been thinking at that moment. Was it fear? Regret? Relief?

“One.”

For Liberty.

A shot rang out.

Marie burst into another round of sobs.

Hothouse Mischief PJ Gartin Photography

Chicos Camila Carrillo-Marquina

Collage / Photography

AN INTERVIEW WITH A$IAH MAE, Charleston’s Poet Laureate -- Miscellany Interview #1 --

Photograph by Joshua Parks

A$iah Mae (they/she) is a Black, non-binary Southern poet, humorist and cultural worker with roots in Georgia, South and North Carolina.They are currently serving as the Second Poet Laureate of Charleston, SC.

Interviewer:

Of all your creative endeavors, which would you consider your first love?

A$iah:

I want to say writing, but it feels like TV was my first love. I always loved storytelling. I would always watch shows with my grandma (who I called Gma), who was always watching Walker Texas Ranger and In the Heat of the Night, or with my mom, who was into Law and Order and competition shows. I had lots of media variety–I collected DVDs and VHS tapes to watch and study. I found myself asking questions like “how do you go from start to end of your story”–and I think TV and movies really help you see that. I really love cartoons with storylines that evolve as the show goes on–I love Steven Universe, and Rugrats with the crossover ‘all grown up’ continuation. And of course, there were the Disney Channel movies.

Interviewer:

Would you say these were some of your major influences on your art?

A$iah:

Oh, of course, but there’s so much more. Hearing Jill Scott’s album, her being an R&B artist and poet, experiencing her live when I was 10–I was just like, oh, this is where poetry can lead you. I don’t have to stick to this Edgar Allen Poe-esque Sylvia Plath type of writing. She opened up a lot for me. Because of her, I learned that I can explore different mediums through poetry. And then Toni Morrison, she can write a book in a sentence. Morrison also writes very specifically for Black people and I aspire to her, I can’t even say I aspire to her because, how do you even aspire to show the love that she does with her words, how do you examine things with the care that she does? I come back to Sula every year around my birthday. It’s my reminder of the duality of very specific Southern Black women. As a nonbinary person who considers myself a Black woman, Morrison’s writing shows that experience that I was reared in–I am allowed to contain multitudes.

And then there’s J. California Cooper, who I would put myself in lineage with. She’s a fiction writer who has the same type of care and love very specifically for working class Black people. I fell in love with her as a kid, and I re-read her constantly – it’s just a comfort that I don’t often find in contemporary fiction.

Interviewer: Mhm.

A$iah:

I consider myself a Southern writer, not “Oh I live in the South”, but my core, my family, my roots all come from this area. I can’t trace my lineage all the way back, but I can trace my roots in Georgia and North Carolina. The connection that I have to this land and this soil is… special in that way, and certain writers get that. It’s something that needs to be examined more.

Interviewer:

When did you begin writing?

A$iah:

I wrote all through elementary school, but I remember my 6th grade language arts teacher, Ms. Herring, had a unit on poetry–she broke down “this is a sonnet, this is prose,” and things like that. For years, I didn’t remember any of that stuff, but I remember during one unit we would recap what we learned in class and write our own poems at home. Ms. Herring always gave me positive feedback and always pushed me into challenges that made me go “ooh, okay.” She sparked my creativity. I had never dealt with anyone giving me prompts like that. Even just exploration of ekphrastic poetry as a kid, like okay, write from the POV of this mouse from this story. Just learning the term, saying “oh my gosh, that’s what I do, that’s what I like, that’s crazy!”

Interviewer:

And how has your writing evolved over time?

A$iah:

I enjoy reflection. If anything, it’s gotten more honest. When I was younger, my writing was very honest and vulnerable, but I never shared it. When I did put things out, it would be get your feelings out then figure out how to mask it. I’ve gotten more comfortable with my work being close to me and being vulnerable. The biggest thing is that I create for myself. It’s a constant everyday practice, being that this is my contribution to the world, nobody else is gonna do it like I’m going to do, nobody is going to receive anything else but what I give. Constant, everyday.

Interviewer:

And your poems? Do they evolve differently?

A$iah:

I’m so bad about revision in poetry. That’s why I don’t like to hear “when are you gonna put out a poetry book?” That means I have to get out of revision–write the thing, come back and sit with it for a while. But a poem can sit in my phone for a year, and then one

day I want to write, and I think “oh, I can play around with this,” or “I can mess around with this concept.” But revising and editing are two very different processes. I want to say thank you to my editor friends. I’m very lucky to have them. But on average, I write about three or four finished poems a year.

Interviewer:

How do you know a poem is finished?

A$iah:

Okay, great, I have a real poet’s story for this one. A few years back, when I met with Nikki Giovanni, she said that a poem is finished when it’s done. So that’s how I’ve felt for the past couple years. Done doesn’t have to mean good, but it means done, you know?

Interviewer:

How do you balance originality and tradition in your writing process?

A$iah:

I think it’s because I’m not an academic poet. I didn’t go to school, but I consider the Watering Retreat my formal training. For example, one year, Julian Randall was the workshop instructor, and he broke down sonnets. So, for me, 2023 was my sonnet year. I also learned about writing poetry from sharing on twitter. It’s a really valuable resource. Because I don’t come from that academic world, sticking with tradition is something that doesn’t weigh on me so heavily. Looking at tradition is something I want to highlight or give reverence to, not so much as I have to do that. But yes, if we’re following someone, that’s okay too. “Can we try that?” I think, and “what bits feel good?” But there should always be a constant reminder not to change yourself.

Interviewer:

What’s your best piece of advice for new writers?

A$iah:

Let yourself be inspired by anything. You don’t have to take inspiration from other writers. It’s the same way poets are obsessed with birds–like, what poet do you know that’s not obsessed with birds? We understand it, there’s no such thing as bad inspiration, but you don’t have to take that same inspiration; you don’t have to write that same way.

Interviewer:

Okay, let’s move on to your organizing work. Can you tell us how you started For the Scribes and other organizations?

Photograph by Buxton Books

The launch day for This is The Honey: An Anthology of Contemporary Black Poets curated by Kwame Alexander. Titled A Great Day in Poetry and featuring local poets Joanna Crowell, Gary Jackson, Ronda Taylorn and Dr. Tonya Matthews of the IAAM.

A$iah:

Well, For the Scribes came first. I met one of my best friends, my literal partner in poetry, Willie Kennard III on Twitter. We were both part of what was supposed to be a writing group but turned into best friends. We used to meet in coffee shops, and we would talk about how we were so bored with poetry and writing, how we had both graduated college, and how the move back home left us feeling stuck. There was this Twitter account called “Black Creatives,” also, where we used to do monthly chats and conversations that were really inspiring. It was a group that said just give yourself time to do something. We said, “we can do a blog, let’s give ourselves a month”–and we did! We had nothing else to lose. It ended up being a jumpstart for everything. We didn’t expect it, but we had a lot of prominent writers who have gone on to do larger and crazier things, but our website was their first contribution. For example, we interviewed Alicia Harris, one of my favorite poets in our second year. For the Scribes is a site to give prominence to our community, to Black queer writers who had no home. We wanted to create that space.

And then, along with a few other friends, we created IllVibe the Tribe, because we saw another problem: the underground scene has no platform to perform on, it has no artist development, no way to get from one place to another. “Let’s throw an art market,” we thought, “why not?” We had the opportunity to, and I have been very lucky and blessed to have people who saw something enough in me to give me a shot.

The Alicia Harris interview was so crazy because of how it all happened. At the time, Willie had taken photos of her book online, and she reached out to us asking if we wanted payment. Willie was just like “actually, can we interview you for our blog?” We went to New York in 2016 to cover AfroPunk, and that was crazy because somehow we also got press tickets, again from our little blog, and with IllVibe we appreciate how we changed the way the music scene moves here. Businesses used to not let you throw pop-up shops. We worked our asses off cultivating a culture where that was okay, where people could get from an underground show to one of our markets, to a festival change. I like being in the background–all of this [referring to the interview] is weird for me, because I am used to having a community around me to defer to. That’s what brings me joy.

Interviewer:

How do you handle the business aspect of being a writer?

A$iah:

Again, I am very lucky to be surrounded by very smart people who give advice, and a lot of the creatives I know are also business people. Like, I have a friend who is a muralist now but used to be an A&R person, and her husband’s a lawyer. I’m very big on using my resources, and those resources often come from the community. It’s a very AN INTERVIEW WITH A$IAH MAE

family oriented reciprocal relationship I try to build.

Interviewer:

Can you tell me about Midlife Monologues and Pure Theatre?

A$iah:

Midlife Monologues is a showcase but kind of runs like a play. It’s put on by Hot in Charleston, which is a project by Kerri Devine. She reached out to me, and Marcus Amaker was like “she’d be the perfect person for this.” She approached me like, “this is a showcase about becoming, from different women in the area.” We just had a conversation, and she basically told me, “just write yourself a monologue.” I was the youngest reader, and it ended up being about being multigenerational. I wrote about becoming thirty-two. My mom had told me that thirty-two was the age my life would come together. It was definitely weird and challenging, but I wanted a challenge. I had been leaning more towards theater in the last couple years, and Midlife Monologues felt like a nice path to get my feet wet.

Interviewer:

How do you balance so many different methods of self-expression?

A$iah:

I’m very spirit led. I tend to lead a very intuitive life. I go toward what’s calling me at the moment, and luckily, they’re not all calling at the same time. Some seasons it’s more poetry and fiction, and some seasons it’s more performance and film work. But I’m grateful for that understanding of balance.

Interviewer:

Can we also hear about the poet laureate status, and about your history there?

A$iah:

Well, Marcus [Amaker] had done six years, two three year terms. He decided that he wanted to step down. When he did, the city opened up the position and formed a board. I applied, and it came down to three people. After 2020 – and I don’t like to play the representation politics game – I understood how it is to have someone like me representing those spaces, and I knew how much that mattered. It’s not about me having a voice, but to represent a voice, and to open up space for those voices. I never wanted to be anybody’s talking head, like I said, I’ve always been a rebel by nature, I’ve never been like “okay, use me for this,” but if I can see the merit in something and if I can see that it makes sense for my community at large, then it’s bigger than me.

In terms of plans, I really want to continue what the poets here want. I want to lean more into the College. Charleston is a very literary city and it can be explored

more, and I want to help make that happen. I love the Charleston Literary Festival, they’re amazing. Sarah Moriarty, the things she wants for the festival are so grand and we have similar goals. We also have the Freeverse festival, which has been around for eight years, and it is such a good fixture for the vibe. It can be expanded upon – there are so many pockets of Charleston literacy that can come together to make it a staple, and I want that.

Other than that, my biggest dream is to bring a slam poetry team to every high school in the Charleston tri-state area that wants one. It’s a sport that requires physical and mental endurance. You have to memorize the poems, know the rules, get up on stage, and make people believe in what you’re saying. For kids who aren’t into traditional sports, they should have that outlet. I didn’t have my own team in school, but there was local slam in my community growing up, there was slam on TV, and I knew that it existed -- that was what was importnat. I didn’t really get into it until college. Slam poetry disciplined me when it came to writing, when it came to respect for my fellow writers; getting up on stage and bearing that emotion. I feel like I’m an athlete coming from that, and I want to give other kids a chance to experience that.

Interviewer:

Do you see a time when you’ll be done creating?

A$iah:

Oh G-d no, I hope not. I really want to be creating something on my deathbed. I don’t know what it is, but I chose writing specifically as the head of my artistic life because writing is a long game. I can write forever, as long as my hands and mouth move, and maybe by then they’ll have a machine to MAKE WORDS. Always and forever.

Interview conducted March 14th, 2024 by Michael Stein.

AsiahMae attended the now-closed Art Institute of Charleston for college as a film student, where they began reading at open mics. They are originally from Columbus, Georgia.

Alyssa Giorgino Sun Bleached Mixed Media

American Guzzle Benny Cauthen

Do you have to be wholly southern, tall American

To become a golden classic all-American?

I remember jazz and teenage burger diners

Band shirt consuming mall-American

I heard of burning desert rodeo riders

The greatest western wall-American

I know Elvis fell from the Hollywood sign

A shooting up in the stall-American

They say the Devil plays electric guitar

He’s a rock ‘n’ roll flower gall-American

On the road longing for a horse and sun

Like a Damascus-bounding Saul-American

Blood red, bread white, and feeling kind of blue

I must be MADE IN THE U.S.A. all American

A Dozen Half Shells to Share With My Ex-Lovers

Eden Shames

I bring them here to dip a spoon in bitter lemon and bathe in dirty gin.

Do you want to share a dozen?

That sounds great, One nods in agreement. You’ve had oysters before, haven’t you?

Of course, One says.

They’re like clams, right? Well, they’re similar...

I tell One that I am unable to tell the difference between a July watermelon and an August peach because I chew amid the season of leaving and missing the full moon rising over the ocean.

One says that he’s never tried a peach before. So you’ve never had a peach or an oyster?

They all taste the same to him and it becomes clear he’s never thought to crack open a shell, toast to it, and pour sweet South Carolina juice down his throat.

I look out through the window to yellow grass and frozen fountains and confuse a sparrow

rolling in dirt with an owl’s echo through the walls, and I want to walk up the steps with a bottle for Two.

Leg Room

Alix Averitt Photography

Rebecca Maude Figures of Mess Pastel & Pen on Paper

Bottle Your Body Eden Shames

I picture you wet getting out of the shower wrapping a towel around your waist, running your fingers through your hair.

I want to dig my nails into your sides until you bleed and watch the cotton soak with your blood. To feel you squirm beneath my grip as you wriggle and writhe releases an orgasm I only experience when I dream of you

inside another woman. I want to squeeze your torso so tightly my fingers drill on through, and I can lace them between your ribs. The towel is bathed in deep burgundy like I could wring it into a glass

with a long stem, and critique its tannins of dark cherry and sun-drenched plum over a wooden table, set with knives before a dark window.

Rocket Man

Hanwen Zhang

Mr. Julius (that was his name, according to Mom and Dad) walked into his living room every day between 4:32 and 4:43, though once he had been late and entered at 4:52 (that had been on June 12th). He would come in carrying this big red toolbox, which he set down beside the sofa. Then he would pop open the lid and arrange all his screw drivers in a row across the coffee table, kneeled down on the floor. I always liked that, mostly because of how neat the entire process was. The way he arranged them, with their handlebars facing the same direction, made them look like tiny rungs on a colorful ladder.

Later, he would disappear into the dining room, and then come back holding this shiny metal board, big enough that he had to hold both sides of it, with small squares and circles and lots of wires that dangled off the sides like a tangle of silvery spaghetti. The board was my favorite part. It looked complicated and important, like one of those things only grown-ups knew how to operate, and it reminded me of the cockpit dials inside Dad’s plane.

I knew all of this because I watched Mr. Julius each afternoon for three-anda-half months (starting from February 15th, to be exact). For my birthday Dad had given me a pair of binoculars, the kind that could zoom into a street sign from almost a quarter of a mile away. Of course, Mom and Dad had told me that I shouldn’t use it to spy on other people—I should only look at “faraway things,” like birds and trees, with it—but I hadn’t really meant to do so. Not in the beginning, at least. I was just trying to get a closer look at the black bird circling our trash can one day when I noticed the flash of Mr. Julius’ metal board from the corner of my eyes.

I got to see the board grow bigger each day. It made me happy, watching Mr. Julius work on his board, kind of like watching a baby tree grow or seeing someone solve a puzzle. And like a puzzle, you didn’t know what the picture would be until it was completed. The board had started out almost the size of my iPad, and then it became as big as my dinner table mat, and then one of those cardboard tri-folds we had to use for Mr. Ross’ school science fair. Mr. Julius would start with a little square of metal and then drill holes into it. Afterwards, he glued tiny cylinders using this hot thing with a pipe that made a blue-ish flame, and then attach lots of wires to the back. Then he would join it to the bigger board. On afternoons when this happened, he walked in with a black motorcycle helmet and an even bigger pipe, one that sent flying sparks like 4th of July fireworks.

This afternoon, he fixed a red button in the bottom left corner of the board. It was square-shaped, with a smooth face, and he connected the back to a knot of other

HANWEN ZHANG

wires with the blue flame from his pipe. A small green light flashed when he pressed the button, which must have meant something good, because afterwards I saw him jump up and punch his fist in the air. He had never done that before.

Another thing I noticed during my 105 days of observing him was that Mr. Julius didn’t like to smile. Most of the time I would have thought he looked a little angry, even. Or sad. Which was strange, the fact that a man working on something so interesting could seem like he hated his own creation. His white eyebrows scrunched together like two big, bushy caterpillars, and his lips were always pressed as if he was secretly biting down on them. Once, I saw him punch a chair when a wire snapped. He didn’t have much hair left on his head either, most of it was wispy and white, but he tugged at them whenever he paced the floor.

He worked for about two hours daily, finishing anywhere between 6:35 and 6:50. At that point, he returned his screwdrivers back into the toolbox one by one, and when he was done, he disappeared with his board. On his way out he would flick off the living room lights, and then his house would go completely dark for the rest of the night.

Sometimes, after he turned off the light, I would put my binoculars back on the third shelf and lie on the floor, on my back. Feeling my own breaths pass through my mouth, in and out, in and out, like what Mrs. Clancy at school told me to do. Usually, such as today, I thought about the board, and all its wires and knobs. It was funny: the more Mr. Julius worked on it, the more I wanted to figure out what it was. Mom and Dad would probably know, but at the same time I wasn’t sure if they’d be happy finding out that I spied on other people from behind my curtains.

Instead, I could only make hypotheses, which were educated guesses about the nature of reality, as Mr. Ross liked to say. Last week I hypothesized he was building a radio, but now I decided instead that he was trying to make a stoplight. Tonight, I imagined myself pushing the red button and seeing the green light turn on.

qRule number five, which came after the rule of locking the front doors, was not to talk to strangers. It was okay, because I usually didn’t have trouble with it. The bus dropped me off at the corner of Heron and Canary, and from there I walked for ten minutes back to the house. I stayed on the sidewalk to the left of the street, which had 139 squares of pavement before reaching the driveway and was a good number (since each digit was an exponent of 3). When I walked, I always tried to fit one foot on each square, something that had been difficult for me last year but not anymore, since my legs probably grew over the summer.

I passed 21 houses on the way back from the bus stop, and all of the people along the way were very nice. Like the owners of the big blue house with the funny-looking dog, who waved every time they saw me. And then there was the old lady

with pointy glasses pruning her bushes. And also Mrs. Michaelson, who was Robbie’s mom, and who always smiled funny at me, looking like the way Mom had when we walked past a lost puppy once in the park. Whenever the weather was bad she would pick up Robbie and me in her minivan and drop me off at home. I remember in kindergarten Robbie used to look at me and whisper into her ear, but she would scold him for doing so.

No one was outside when I got off the bus this afternoon. It was so bright that all the tree leaves were curled on their branches. My armpits started gathering sweat after the 11th house, around pavement square 68. I read in a book that the sun was actually further from Earth during the summer, but the angle of our planet allowed its heat to penetrate the atmosphere more efficiently, which was why it felt hotter.

I always crossed the street at Mr. Julius’ house. This was when my breath would catch a little, and I would walk slightly slower, just slow enough to have a peek at what he was working on, without looking too suspicious.

Like today, his house was usually dark. Besides the living room, he kept all the other curtains closed. I liked how his yard was interesting, too, and different from all the others on the street. There was a crooked fence that circled his entire backyard, and tall grass grew in between the missing boards. He had pale green shutters with patches where you could see the bare wood. In the front yard, he kept an American flag hung across the central branch of a dying maple tree.

The real problem came when I reached the driveway. According to rule ten, I was supposed to take in the mail and any packages on our front step. And right at our door was this big cardboard box labelled for 2298 River Road, not 2295 River Road, which was our house. 2298 was Mr. Julius’ house number. And Mr. Julius was a stranger.

My watch said it was only 2:45, so I knew Mom was still at work. Cami’s car wasn’t in the driveway yet, either, and I remembered she had theater rehearsals all week after school. She had shut herself in her room all weekend to memorize the lines of this play, something about an old king who went crazy.

Tiny speckles of dust swirled under the sunlight, and it was hot. I could feel the sweat dripping down the sides of my arms like thin, tickly rivers. Then I closed my eyes and stuck my index fingers into my ears, something I tried whenever I had trouble making a decision. Do the right thing, pal, Dad would say. But then, don’t leave the house without our permission. At the same time, though, try to help others. Lend a helping hand. Which, in this case, would be to give Mr. Julius the package. Therefore, I decided Mom and Dad would make an exception to rule five.

I stumbled backwards as I tried lifting the package. Whatever was inside must have been heavy, since the cardboard sagged under its weight as I tilted it to one side. It made a hard, clanking sound when I lifted it, and I had to stop in the middle of the street for a few seconds to put the box down and rest.

Mr. Julius’ yard looked a little different once you stepped into it. Up close you

HANWEN ZHANG

noticed different things, like the weeds sprouting in between the cracks of his driveway. Or the rusty blue pick-up that was parked by the side of his house and partially concealed by crooked pine trees. A pair of daffodils in the flowerbed swayed a bit in the breeze, like they were nodding at me to go on.

I dropped the package far enough up his driveway, almost to the place where it met the little sidewalk that curved to his doorstep. Then I walked to his front door, just to make sure he knew about the package.

His doorbell glowed a faint orange, and it sunk neatly into its socket when I pressed. A faint ring buzzed on the other side of the door.

No one answered. I pressed it again.

Inside, a pair of shoes dropped onto the floor with a muffled clomp and someone yelled, “Jesus, I’m getting the door already!”

The door swung open. It made a sharp sucking sound against the screen door, almost as if the air was being squished and then squeezed.

“Whaddya want?”

I jumped.

Mr. Julius was standing in front me, on the other side of the gridded screen. His voice was louder than I imagined, and croaky too, and for some reason it reminded me of gravel rocks clattering against each other in a plastic bag. His forehead was crinkled, and the space between his eyebrows looked like the contour maps that Mr. Ross hung on his wall in science class.

“Can’t you read?” He pointed to the milk crate at the front of his driveway with the sign taped to it. In large, capital letters, it read “NO TRESPASSING: VIOLATORS WILL BE PROSECUTED.”

I knew what the sign meant. Not the words, exactly, but Mrs. Clancy had explained to me that people put it up when they didn’t want others to walk across their lawn. Some of the houses next to the playground had the sign on their fences, too. Which I thought it was all a little silly, because most people wouldn’t want to walk across the grass when there was a sidewalk.

“Well?”

“For you.” I pointed to the package on the driveway, which blurred and wavered a little through the thin wet layer over my eyes. My throat felt hot and sticky. I would not cry. I told myself that while I bit my bottom lip as hard as I could. But my voice still did this funny trembling thing, and it almost sounded like Cami’s piano being tuned.

Mr. Julius craned his neck to see. He pushed the screen door open. Then he just stood there, on the doorstep, making this soft grunting sound, his eyebrows slightly softening. A few of his wrinkles had melted back into his forehead.

“Thanks.”

I tried to make my feet move and leave the driveway like I was supposed to, but at that moment they couldn’t. I wanted to know more about the shiny metal board

and the tub that made blue flames, and the buttons, and what it felt like to press them. And if the thing inside the box was for the board or not. Then the words just spilled out of my mouth, like water overflowing in a bucket.

“What’s in the box?”

“That’s none of your business, kid.” Mr. Julius crossed his arms.

“I like your board,” I added. Just like that, I said it.

Mr. Julius stiffened. His mouth twitched and softened.

“Where do you live?” he asked.

I pointed to our house across the street. From his driveway I could see my window, the green-blue square of glass that was above the second garage door. Cami’s Jeep was pulling into the driveway.

Mr. Julius took a long look at our house and said something under his breath I couldn’t hear.

“What?”

“Not now. Some other time, okay?”

My breath shortened when he said that. It was a promise, like Mom telling me I could get another 15 minutes of TV time on Friday. Something that would happen, sooner or later, in the future.

I ran back across the street and through the grass. Cami was too busy showering off the paint on her arms to notice that I had slipped into my room through the backdoor. Later in the afternoon, Dad came home from Paris, and he slept on the couch while Mom cooked. I didn’t tell either of them about what happened, because I know they usually didn’t like mentioning Mr. Julius. Every time they looked across the street, Mom would put her hand on Dad’s shoulder and lean close to his ear and talk in a low, hushed voice, almost like she was whispering a secret.

qI waited every day for Mr. Julius to come. The key to wanting things was being patient, and Mrs. Clancy always liked to say that I was very good at that. Over the next two months, I sat at my desk with my pair of binoculars and watched the robins in the front yard, or lay on my back and felt my stomach rise and fall with my breath.

I counted 21 FedEx trucks that stopped in front of Mr. Julius’ house. Most of the deliveries were the same size as the one I had pushed onto his driveway. The deliveryman sometimes stumbled as he took the box down from the back of the truck, and his steps were wobbly when he carried it to the doorstep.

Mr. Julius only opened the front door after the truck left. He would come out and stoop a little from the effort of lifting the box, and then disappear, the metal screen door flashing as it closed behind him. He reminded me of the baby wooden deer on grandma’s old clock, which would peek out from its hole every hour. Once, I tried

pulling the deer with my fingers at 4:35 in the afternoon, to see how it worked, but I accidentally broke it.

After taking in the box, Mr. Julius would return to the living room with his board, helmet, and metal pipe. During these 48 days, he added a grid of buttons, as well as small black cylinders and these funny square green plates with metal stubbles all across them.

I was scared of Mr. Julius, but at the same time I couldn’t stop myself from watching him. I still hadn’t figured out what his board might be, even after I sketched it all out in my notebook. It flashed a green light when you pressed it, with knobs and buttons that sent signals to aliens, maybe, even if I didn’t think they existed. It was almost beautiful because of its mysteriousness, something that looked like it would actually work, whatever it was.

At the same time, I noticed that Mr. Julius had started a different routine. The living room stayed dark in the afternoon and the curtains were drawn. Sometimes, if I opened the window and put my ear close enough by the screen, I thought I could hear a sharp screeching noise from his backyard, almost like metal grinding against itself.

On August 13th, at 4:12 pm, Mr. Julius attached a wagon to his truck and left. He didn’t return until 7:33 pm, almost after we finished dinner, with piles of twisted metal and dirty orange plates. Mom pulled me away from the living room window when I tried to get a closer look, making a small sigh as she closed the curtains.

The thing was, Mr. Julius liked to sit on the sofa at night. He’d have a big blackboard pulled out in the living room, and it would be filled with squiggly lines and numbers that made my head hurt when I saw it. He would take out a calculator, scribble some other lines with a piece of chalk, and stare at it with his hands in his hair. Then he would wheel the board away and place his hands on the window ledge.