COLUMNS FEATURES

EDITORS’ LETTER

by the Editors

Cultural Currency

RIGHTLY ORDERED: THE DECLINE AND FALL OF LIST-MAKING

by Joshua Gibbs

Book Reviews

BECOME A DEFIANT HOLY FOOL

by Gracy Olmstead

FLANNERY O ’CONNOR: PROPHET IN HER OWN LAND

by Sean Johnson

A COMPLICATED DIALOGUE WITH A LITERARY GIANT

by Heidi White

AN INVITATION TO REMEMBER THE CLASSICS

by Greg Wilbur

From the Classroom THE TEACHER AS NEUTRAL REFEREE

by Joshua Pauling

This magazine is published by the CiRCE Institute. Copyright CiRCE Institute 2020. For a digital version, and for additional content, please go to formajournal.com.

For information regarding reproduction, submission, or advertising, please email formamag@circeinstitute.org.

Contact

FORMA Journal

81 McCachern Blvd SE - Concord, NC 28025 704.794.2227 - formamag@circeinstitute.org

Facebook: @circeinstitute

Twitter: @formajournal / @circeins

Instagram: @circeinstitute

Issue 13 Winter 2020

26 I AM FLAMBEAU: CHESTERTON ’S ARTISTIC CONFESSION

by Brett Chancery

HOME IS WHERE THE ART IS: A LOOK AT FLANNERY O ’CONNOR ’S HOME PLACE

by Graeme Pitman and David Kern

BOOKS THAT SURPRISED IN 2019 by

Various Contributors

A CLASSICAL AND COSMPOLITAN EDUCATION

by David Withun

by David Withun

THE SOUND BEHIND THE SOUND: A REALIST VIEW OF METAPHOR

by Michial Farmer

The CiRCE Institute is a non-profit 501(c)3 organization that exists to promote and support classical education in the school and in the home. We seek to identify the ancient principles of learning, to communicate them enthusiastically, and to apply them vigorously in today’s educational settings through curricula development, teacher training, events, an online academy, and a content-laden website. Learn more at circeinstitute.com

6

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER 30 52 9 13 17 40 POETRY 20 46 64 42 44 GRACE EOIN MEAGHER 23 60 S.P. COOPER 62 MARLY YOUMANS

Editors' Letter

Winter is a contradictory season. On the one hand, darkness and cold reign, driving us to the warmth and safety of hearth and home. Despite its stark beauty, winter is frequently inhospitable, a season lived mostly indoors unless we’re prepared to encounter its frigid welcome. During winter, when the world seems dead, we long to snuggle under soft blankets and read by a crackling fire.

However, winter is not merely the cold fade of an old year, but the burgeoning entrance of a new one; it is a season of possibility. The turning of one year to the next offers opportunities for growth. And FORMA has grown quite a bit this winter, adding scores of new subscribers (and counting!), launching the FORMA Review, and featuring many new and established voices at the intersection of classical thought and contemporary culture. We are proud of what we’re building: a gathering place for lively conversation about the creative and intellectual output of authors, educators, and innovators doing important work in this cultural moment.

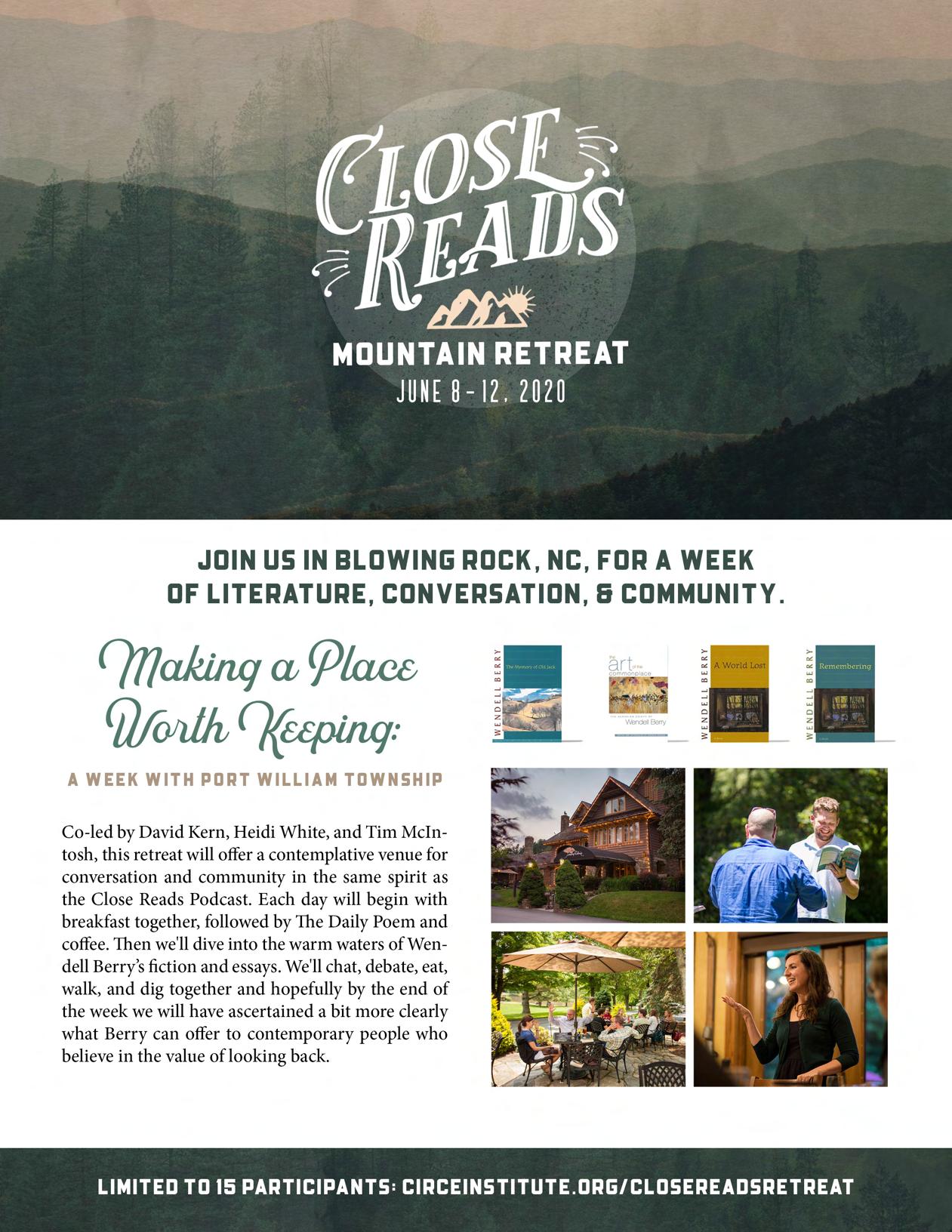

Our growth is exciting, but we exist to serve you in 2020. In this Winter Issue, you will find (among other offerings) Gracy Olmstead on Andrew Peterson’s long-anticipated book, Adorning the Dark; a photographic look at Flannery O’Connor’s homeplace, Andalusia; an essay about the American obsession with list-making; a contemplation about the cosmopolitan responsibilities of classical educators; and a reflection on G.K. Chesterton’s neglected but important villain, Hercule Flambeau. And of course, as always, we are pleased to offer original poetry by contemporary poets.

As we enter 2020, FORMA continues on an upward trajectory of growth while maintaining our steadfast commitment to classical standards. Whether you spend your winter curled up by the fire, practicing productivity, or a little bit of both, we are honored that you are with us.

Sincerely,

The Editors

The Editorial Team

Publisher: Andrew Kern, President of The CiRCE Institute

Editor-in-Chief: David Kern

Managing Editor: Heidi White

Art Director: Graeme Pitman

Poetry Editor: Christine Perrin

Associate Editors: Emily Andrews, Sean Johnson

Senior Editors: Jamie Cain, Matt Bianco

Contributing Editors: Ian Andrews, Noah Perrin

Copy Editor: Emily Callihan

Cultural Currency

In October of 2019, with very little fanfare, the music critics at Pitchfork released their list of the two hundred best songs of the last decade. While perusing the titles, I recalled the last time such a list was published. Ten years ago, year-end Best-Of lists were a much bigger deal, not just for Pitchfork, but for every media outlet that reviews books, films, and music. December was the month every self-respecting critic ordered all the releases of the year into a numerical hierarchy, proclaimed one film or book or record “the best,” published links to the list on social media, and waited for the comments section to fill up with nitpickers and naysayers. A decade back, BestOf lists were a sufficiently big deal that some websites acquired corporate sponsors just for their lists. Many websites announced when their lists would be posted weeks in advance, then slowly rolled out their lists day by day in the final weeks of the year. With the end of the 2010s upon us, though, the hype which was typical of Best-Of lists ten years ago is waning.

In the early ’80s, magazines like Rolling Stone would note the ten best records of the year in an off-cover article published in December. By the 2010s, Rolling Stone was annually compiling a list of the fifty best records and one hundred best singles, not to mention separately compiled lists of the same categories as chosen by readers (as opposed to staff writers). The popularity of lists peaked about five years ago, around the same time hashtag activism really took off. But since 2014, the hype which surrounds the publication of year-end lists has gradually declined. The graphic design for the lists is less flashy and less expensive, and the lists rarely occupy a place of prom-

inence on the websites which publish them for more than a few days. As opposed to a retrospective on the year and a celebration of artistic accomplishment, year-end lists now seem embarrassingly obligatory, like a formal apology from a celebrity for saying something unfashionable about race on Twitter. Lists are simply more trouble than they are worth.

The reason for declining interest in lists, of course, is that hierarchies of any kind are an increasingly touchy subject, and any list of the best albums or films of the year is necessarily going to place the artistic accomplishments of one race over another, one gender over another, one sexual orientation over another, and so forth. Every Best-Of list is now occasion for accusations of bigotry or pandering, and while such accusations have become as common as daisies, one gets the sense that few magazines and media outlets want to end the year with controversy and a deluge of online acrimony. I suspect that within ten years or so, no websites will numerically order their year-end lists and ten years after that, the lists will be gone altogether. One also gets the sense that the Academy Awards are just one bad fall away from being euthanized, and when the Oscars are gone, the rest of the accolades industry is sure to follow.

Looking back now, it is strange the popularity of lists came so late in Western history, for the list seems more a medieval art form. Perhaps the modern fascination with lists was a lingering effect of neoclassical tastes, less hierarchical than rational and scientific. The medievals gazed up into a well-ordered night sky, a hierarchy of spheres and angels, and they liked their lives on earth to mirror

FORMA / WINTER 2020 | 9

After Sei Shōnagon

what they saw when they looked toward God. Regardless, the idea of arranging works of art into a hierarchical order now strikes many people as patriarchal, and a few media outlets have already given up attaching numerical assessments to their reviews of books or records. The one hundred best albums of the year are arranged according to their release date or just alphabetically by the artist’s last name.

When I was young, I loved making lists. In my bachelor days, my friends and I often passed the time by making lists of favorite movies, songs, and meals. Seven or eight of us might stay up until three in the morning, composing lists of singers or bands, then reading the lists out loud in rounds from the bottom to the top. Every man in the ancient world knew Helen was the fairest, but only because he had made a list and compared it with others. Boys still make such lists today, I am sure. I can even recall a dinner party wherein my wife and I and another couple sat around late into the evening making lists of the five most handsome men in the world and the five most beautiful women in the world, then reading our lists out loud to the table. You don’t really know someone until you’ve heard them say Paul Newman was the best-looking man of the twentieth century.

Year-end lists are not just the stuff of dinner parties and Rolling Stone, though, for social media has made every man the editor-in-chief of his own Review of the world. Before I deleted my Facebook account in late November, I made three Best of the Decade lists: Best Songs, Best Records, and Best Films. Six of my friends also published Best of the Decade lists and a few will likely publish separate (but agonized over) lists of the best songs and films of the year, as well.

Among music geeks and film nerds, such lists are something of a competitive sport, for the key to putting together a great list is including a few things that no one has heard of and a few things which everyone else passed on, but also a few mainstream items everyone will recognize. Unspoken rules abound. Placing a song with mass appeal (something by Harry Styles, say) close to the top of your list is a little like paying $200 million dollars for a Jackson Pollock painting—it is an argument that there’s

something more to the music which the snobs haven’t yet noticed. Hidden in plain sight, as it were. However, I think the wealthy musicians in the world are a far more talented lot than the wealthy artists of the world. Anyone who is privately, authentically impressed with Jackson Pollock should not be trusted behind the wheel of a car, but the fellow who gets dumped and cries on the drive home while listening to Three Dog Night’s “One” is perfectly sane, perfectly human. As Noël Coward once said, it is “extraordinary how potent cheap music is.”

The Best-Of list is and is not what it purports to be. Any fellow whose year-end Best-Of list is comprised entirely of stuff that hit the top ten spots on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart isn’t worthy of compiling a list. Of course, any list which is entirely comprised of under-the-radar songs that only eight people heard doesn’t really need to exist either. The best Best-Of lists are two-parts aristocracy, onepart democracy. Performative, but self-forgetful. Snobby, but catholic. A good Best-Of list is a bit of a race, as well, for a fellow has less than a year to find the good stuff with which to pack his list. A well-crafted Best-Of list is thus not only a sign of good judgment but represents an ability to dive into the dark corners of popular culture and turn up the hidden pearls which the mainstream could not be troubled to locate. A good Best-Of list says, “Not only can I find the good stuff, I can find it before the middle of December in the year it was released.” The Best-Of list is thus something of a game, but also a manifesto of taste, a time capsule, and a lot of posturing.

On the other hand, the Best-Of list which encompasses an entire decade is a different animal, for the songs which seem remarkable at the end of a calendar year are often stale by the end of the decade. Nothing which shows up on a year-end Best-Of list has more than twelve months of staying power, at least not necessarily. While working on my Best of the Decade (2010–2019) lists, I revisited all the year-end Best-Of lists I had made and found the lion’s share of what had seemed impressive in the short term had ultimately proven forgettable. In December of 2009, I chose “Heartbeats” by The Knife as the greatest song of the decade. However, the song I now think not only the best of 2000–2009, but the greatest pop song of

10 | WINTER 2020 / FORMA Cultural Currency

Inasmuch as a classical education concerns rightly ordered loves, classical education is concerned with the creation of lists. Know thyself.

the last twenty-five years, only ranked fifty-third on the list I made a decade ago.

Not everyone finds it easy to choose a favorite, though I think it an intellectual duty to know favorite songs, favorite books, favorite stories, and all the rest. The establishment of favorites is simply part of the ordering of the soul, the proper arrangement of spiritual furniture. The favorite is a merger of taste and hope, for a man’s favorite song is not simply the song he listens to most often, nor the song from which he gets the most pleasure. Granted, the favorite brings pleasure, but it may also feed and charge the soul, recall bitter things, bittersweet things, and gnaw away at him. A man may understand his favorite book better than any other book he has read, but there is also something elusive and vexing about a favorite which evades a man’s firm grasp. As with the knowledge of God, the more deeply a man knows his favorites, the better he appreciates the fact his favorites cannot be fully known. I have never thought of my wife as my best friend, though she is my favorite person. I understand her far, far less than my best friend, Jon Paul, whom I understand (and who understands me) with telepathic clarity and scientific exactness. My conversations with Jon Paul bear a striking similarity to the conversations I have with my own soul before confessing my sins. While my wife is a stable, predictable human being on the one hand, she also sometimes seems to me like Borges’ book of sand: once the reader has turned a page, he will never return to that same page again.

Inasmuch as a classical education concerns rightly ordered loves, classical education is concerned with the creation of lists. Know thyself. The man who has followed the dictum knows what he loves, the degree to which he loves what he loves, but he also knows how his list of loves ought to look. The pleasure of making lists of anything—songs, books, painters—is judging minute differences in our own affections. A good list is not just a technical assessment of the relative pleasure offered by a number of things, but

a catalog of devotions, prejudices, goals, ambitions, and loyalties, all arranged and proportioned and harmonized in such a way that a single personal credo emerges. Much like common sense, lists are brazenly non-egalitarian. Lists are judgmental, technical, subjective, and offensive to everyone ranked second or lower. Lists of greatness are arguable but unprovable. The creation of a hierarchical list burdens, stresses, and strengthens the imagination, for the task involves seeing disparate things in the light of one another and in the light of the transcendent. All this to say, the creation of lists has become a vestigial pastime inherited from an older world, born of beliefs entirely different from our own. Perhaps the short-lived popularity of lists late in the twenteith century was nothing more than the final stand of a now obsolete view of reality.

No one taught me to make lists when I was young; it came naturally, and so I doubt the inevitable demise of the Oscars and the slow fade of Best-Of lists will keep the reasonable people of the world from measuring and weighing the glory of things. Medieval men not only believed in an ordered and hierarchical cosmos, they also believed that man himself was a little cosmos, a small universe, a fitting and complete icon of creation itself. Every sphere (Air, Fire, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, and so forth) which separates man from God is also mystically present within the soul of the virtuous man—or, as David Bentley Hart once suggested, God is both at an infinite distance from man and yet He also fills that distance with Himself. It is not surprising, then, that men would arrange and represent their loves in the shape of the cosmos, higher and higher toward perfection. To know our loves is to know the path we must take to return to God.

Joshua Gibbs teaches Great Books at Veritas School in Richmond, Virginia. He is a columnist at the CiRCE Institute and the author of How to Be Unlucky and Something They Will Not Forget. His podcast is called Proverbial.

Cultural Currency

—Dr. John Frame, Professor of Systematic Theology & Philosophy, Reformed Theological Seminary

Read an excerpt at www.LiberalArtsTradition.com

iscover what Great Education once was and Can Be Again An indispensable guide to Christian liberal arts education.

D

“ ”

Become a Defiant Holy Fool

By Gracy Olmstead

What does it mean to be a “creator”? Frederic Nietzsche once suggested that the “noble man,” or übermensch, is one who regards “himself as determining values . . . he creates values.” And many authors speak of their writing as coming from their subconscious, or from some inner “muse.”

But J.R.R. Tolkien offered a radically different version of creativity, one based not within the self, but outside of it. The creative life, he suggested, is predicated upon our ability to receive the fact that we ourselves are created and thus are sub-creators. Our work will only be beautiful or artistic insofar as it reflects the beauty of God, the ultimate Creator. As Tolkien writes in his poem “Mythopoeia,”

Man, sub-creator, the refracted light through whom is splintered from a single White to many hues, and endlessly combined in living shapes that move from mind to mind.

Though all the crannies of the world we filled

with Elves and Goblins, though we dared to build Gods and their houses out of dark and light, and sowed the seed of dragons, ’twas our right (used or misused). The right has not decayed. We make still by the law in which we're made.

God is the “single White,” the source of all color and beauty. All our efforts at beauty, novelty, or glory are small refractions of that greater light, greater beauty, which stems from God Himself.

Andrew Peterson’s new book Adorning the Dark: Thoughts on Community, Calling, and the Mystery of Making is about this sort of creative life: about the desire to reflect God’s glory and to share it with a dark and hurting world. Peterson is a singer-songwriter, author of the Wingfeather Saga, and creator of a ministry called The Rabbit Room, which focuses on cultivating a “strong Christian arts community.” He has spent more than a quarter of a century seeking to create, to share God’s light in songs and other written works—and as his book makes clear, this has been no easy task.

Adorning the Dark is part memoir, part how-to manual for aspiring musicians and writers. But it is also, in a larger sense, about what it means to be a “sub-creator”—to see the teleological end of your creative work as lying beyond yourself. Adorning the Dark defines the creator not as an übermensch, ca-

FORMA / WINTER 2020 | 13

Book Review

pable of self-creation, but rather as a receptor: eager to broadcast the meaning, beauty, and glory you are given (but do not make yourself). For this reason, as Peterson’s subtitle implies, a great mystery rests within our efforts at “making.” We move forward with toil and struggle, but also, Peterson suggests, with grace. He shares stories about loss, hardship, stress, exhaustion, and brokenness. From the story behind his Behold the Lamb of God album, to the early struggles of his musical career, each glimpse of Peterson’s life confirms the fact that creation is a difficult discipline. But each is also inspiring, heartening, encouraging—because through them all, Peterson seems to whisper, “Don’t give up.”

Perhaps artists will feel less pressure if they embrace this identity of “sub-creator” and stop looking for some creative muse within themselves. Perhaps those who see themselves as divine copycats, rather than as their own source of innovation and values (as Nietzsche did), will feel less anxiety as they pursue the creative life. But Peterson suggests that it is not this simple. If we believe that God is “profoundly complex, unfathomable, deep as the sea,” and that we are needy, sinful, and small creatures, then the very act of trying to reflect His light, His beauty, can feel impossible and hubristic. Who do we think we are, anyway?

Many artists struggle with imposter’s syndrome—regardless of religious faith or artistic genre. Throughout several chapters, Peterson describes battles that many readers will recognize. He describes that needling, incessant voice that says we are “not intelligent enough, or academic enough, or witty enough” to accomplish whatever it is we want to achieve. I am not an artist, but I recognize that voice, too. For a long time, it prompted me to turn down speaking engagements, to say no to the (rare) invitations I received to speak on panels or come on radio shows. For a lot of people in the secular world, it seems that bolstering one’s self-respect or pride would be the answer to this sort of crippling doubt. One of my favorite tricks for a while, one that enabled me get up on stage when I wanted to cower in a corner, was to pretend to be someone else. I would mentally assume the identity of a friend of mine—a woman who was far more gregarious, eloquent, and funny than I was—and by imaginatively pretending to be her, I could overcome the mental barriers that prevented me from speaking in public.

But eventually, I learned what Peterson writes so perfectly: “Living as we do in dying bodies in a dying world, our best work always falls short of the initiating vision. Toil and trouble, thistle and thorn, we push through the brush and come out bloody on the other side, only to

realize that we’ve ascended a false peak. It’s difficult, yes. But it doesn’t change a thing about who we are.”

The “answer” to imposter’s syndrome is not to assume an importance or rightness we do not have. Our identity and confidence must lie not in what we create, but in our createdness: in the fact that we are beloved, precious, redeemed. Because of this identity, we don’t have to strive for perfection. We don’t have to win Pulitzers or Emmys. We just have to be faithful.

Peterson’s book is about this work of faithfulness: about the dogged persistence required to write poems, paint pictures, sing songs, or pen novels. It is about the humility required for growth and for proper self-expression. And it is about all the other things—homes, families, churches, and communities—that are also, by their nature, creative and nurturing spaces which can glorify God. Two of my favorite chapters in Peterson’s book—“Longing to Belong” and “Community Nourishes Art”—consider the importance of place, of embeddedness, in living a creative life. This book does not suggest, as some secular authors have, that creation is a solitary endeavor—but rather, that it should always happen within a context, a community. It is through community that we receive accountability and support. It is through the creation and cultivation of a home that we embody the disciplines of creation and stewardship.

Although Adorning the Dark focuses on songwriting throughout, many of its principles and stories apply to other creative efforts. As Peterson rightly points out, you don’t have to write songs or paint pictures to be creative: each of us, regardless of whether we are artists, is a creative being. The gardener, the baker, the woodworker, the teacher: each are creators. And each can, as Peterson puts it, “look for the glimmer of the gospel in all corners of life.”

But our efforts at God-glorification can easily, even subconsciously, turn back toward self-glorification. As Peterson writes early on in his book, “I confess, a mighty fear of irrelevance drove me to this vocation, a pressing anxiety that unless you looked back at me with a smile and a nod and said, ‘Oh, I see you. You exist. You are real to me’ . . . I might just wither away and die.”

With time, Peterson’s artistic efforts shifted away from this desperate desire for self-assurance. He assures readers, “The Lord can redeem your impulse for self-preservation by easing you toward love, which is never about self.” Surrender and humility—both necessary to the life of the Christian artist—also help turn our vision outward again. But, he notes, “You have to believe that you’re precious to the King of Creation, and not a waste of space. You and I are anything but irrelevant.

14 | WINTER 2020 / FORMA

Book Review

Don’t let the Enemy tell you any different. We holy fools all bear God’s image.”

Only a “holy fool” can defy Nietzsche’s “noble man.” Only a holy fool is willing to, as Peterson puts it, “fumble about in a dark room, feeling for the shape of [a new song],” aware of both the brokenness and the beauty in what they create. Only a holy fool can surrender to the “feeling of diminishment” that comes with realizing nothing you create will ever be as perfect as you hoped. Only a holy fool can sit down to write a book, certain of his or her unworthiness—but certain, too, that God can use even this feeble creation for His glory.

Perhaps my favorite part of Peterson’s book is this quote, an excellent description of what it means to see yourself as a sub-creator:

I am convinced that poets are toddlers in a cathedral, slobbering on wooden blocks and piling them up in the light of the stained glass. We can hardly make anything beautiful that wasn’t beautiful in the first place. We aren’t writers so much as gleeful rearrangers of words whose meanings we can’t begin to know. When we manage to make something pretty, it’s only so because we are ourselves a flourish on a greater canvas. That means there’s no end to the discovery. We may crawl around the cathedral floor for ages before we grow up enough to reach the doorknob and walk outside into a garden of delights. Beyond that, the city, then the rolling hills, then the sea. And when the world of every cell has been limned and painted and sung, we lie back on the grass, satisfied that our work

is done. Then, of course, the sun sets and we see above us the dark dome of glittering stars.

Many of us who write or sing or paint have felt a flame within us—a burning desire to create something beautiful, and to offer it up in praise and thanks. But the work is demanding, exhausting. It is easy, when we see the imperfections in our efforts, to feel like giving up.

Despite that feeling, Peterson urges, plant your seed in the ground—and trust that God can grow something from it. Your imperfections, your smallness, might even help you refract the beauty of the single White.

“Write about your smallness,” Peterson suggests. “Write about your sin, your heart, your inability to say anything worth saying. Watch what happens.”

To the hopeful artist, musician, or writer, Adorning the Dark is a letter from a friend on a fellow journey—a journey that can often be shadowed, cold, and lonely. Each of us deals with the doubt and fear that accompany the discipline of creation. And so each of us needs to be reminded of the vision behind the work: the hope that we might reflect a little splinter of glorious light and make this dark world a little brighter by our efforts.

Adorning the Dark: Thoughts on Community, Calling, and the Mystery of Making | B&H Books | $16.99

Gracy Olmstead (@gracyolmstead) is a writer who contributes to The New York Times, The American Conservative, The Week, The Washington Post, and other publications.

EXPLORE the CLASSICS

with other books from this series

ADDITIONAL TITLES FORTHCOMING:

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte

Book Review

16 | WINTER 2020 / FORMA

Flannery O'Connor: Prophet in Her Own Land

By Sean Johnson

By Sean Johnson

Iwonder if any age is more likely than the twentieth century to impress a sense of lonesome isolation upon the homebound soul. Shut-ins, the bedridden, et al. have always been with us, but no earlier age provided such abundant means of knowing just how much was going on outside the limiting circle of “home.” Newspaper, radio, and eventually television brought an awareness of the wider world directly into the life of seclusion. The letter, though, was still a medium that could reach in both directions. For Flannery O’Connor, letters were an enduring link to the world her poor health often barred her from.

O’Connor attended the University of Iowa and lived briefly in New York and Connecticut before a lupus diagnosis forced her back to her family home, Andalusia Farm in Milledgeville, Georgia. The prospect of this new retirement so early in her crescent literary career seems to have struck her as bitter and healthful in turns. Two new collections of her letters—Good Things Out of Nazareth: The Uncollected Letters of Flannery O’Connor and Friends and The Letters of Flannery O’Connor and Caroline Gordon—throw into fresh relief the tension of

O’Connor’s being confined, geographically, to the rim of the literary world just as, professionally, she established her place in its hub.

Of these two collections, The Letters of Flannery O’Connor and Caroline Gordon is easier to speak about— as this review will probably betray—because its contents are a simple dialogue, arranged chronologically. Good Things Out of Nazareth, though, boasts the more ingenious arrangement. In fact, Editor Benjamin B. Alexander used portions of the O’Connor-Gordon letters as a pillar of the collection. Spiraling out from those are a valuable assortment of uncollected or unpublished epistles from O’Connor’s broader literary circles—Walker Percy and Robert Lowell among them. The twist is that Alexander oscillates between a chronological arrangement and a thematic one. The scheme makes it harder to feel the development of relationships in Good Things than in Letters, but it effectively draws together disparate threads in the thought of these writers and critics so that they can be better understood together. To smooth the less intuitive flow, Alexander also provides far more editorial comment upon the letters and their context. Whether through the specific focus of the one or the novel organization of the other, these collections both strike the reader differently than the well-known edition of O’Connor letters that proceeds them.

Myriad readers love Flannery O’Connor’s jarring fiction, but those who come to an abiding love of Flannery herself repeatedly do so through her letters collected in

FORMA / WINTER 2020 | 17

Book Review

The Habit of Being. This earlier collection includes letters to the author, but O’Connor’s own letters dominate and provide a broad personal encounter with the witty, pious, and cheerful young woman suffering in Georgia. The two recently published collections put The Habit of Being in new perspective, though, by revealing facets of O’Connor’s correspondence that it touched on less frequently. Both Letters and Good Things are best described as literary correspondences, largely written about the craft and theory of writing. That first and, for decades, definitive collection included personal exchanges with close friends and family, but was also full of what can only be described as fan mail—appreciations from housewives, questions from children, comically bizarre interpretations from kooky professors—all snapshots of O’Connor reaching out and being touched by an appreciative reading world. By focusing so singularly on communication with her peers, these new volumes punctuate her isolation as a writer so far removed from like-minded artists. Not long after dear friends Sally and Robert Fitzgerald introduced her (by mail) to the novelist and critic Caroline Gordon, O’Connor wrote that

There is no one around here who knows anything at all about fiction (every story is “your article,” or “your cute piece”) or much about any kind of writing for that matter. Sidney Lanier and Daniel Whitehead Hickey are the Poets and Margaret Mitchell is the Writer. Amen. So it means a great deal to me to get these comments.

The Fitzgeralds had sent Gordon an unfinished draft of Wise Blood in the hopes of soliciting for their friend the critical input of an established author. “This girl is a real novelist,” she wrote back enthusiastically, her lifelong interest in O’Connor sparked. No writer was ever helped by unalloyed praise, though, and in one of her first letters to O’Connor Gordon obliges with thousands of words of frank technical criticism. “I would like,” she says in summary, “to see you make some preparation for the title, ‘Wise Blood,’ and I’d like to see a little landscape, a little enlarging of the scene . . . and I’d also like to see a little slowing up at certain crucial places I’ve indicated.” In the same letter Gordon—her senior by thirty years—apologizes if her tone is “overly pedantic,” insisting it is “doubtless the result of teaching,” but a teacher is precisely what the budding writer still needed.

O’Connor also found in Gordon, who entered the Catholic church shortly before their acquaintance began, a sympathetic Catholic intellectual. In various letters, she complains to Gordon of her mother’s reticence to discuss her writings, and of an “83 yr. old cousin” who will only

read sentimental religious “trash.” In another place she recalls a pamphlet by a Jesuit who “seemed to think that A Tree Grows in Brooklyn was about as good as you could get. Somebody ought to blow the lid off.” Good Things also contains exchanges between O’Connor and several priests with a literary bent. The collections together are an obliging corrective to the common and erroneous notion that at Andalusia O’Connor was a lone Catholic in a “Christ-haunted South.” It was not Catholics she was geographically cut off from, but thinkers.

Gordon was not alone in making up this deficiency, as Good Things thoroughly reveals, but her role as literary mentor was unique. In a letter to Walker Percy, Gordon recommends Wise Blood because she believes he and O’Connor suffer from opposite maladies in their fiction—her stories are all plot and vivid action but no scenery, his are all scenery and reflection but no action. “Her focus seems to me like the spotlight a burglar plays on the safe he is cracking. You don’t see anything else in the room. But she sure is good.” Pages upon pages of their correspondence show Gordon bluntly critiquing manifestations of this weakness in her stories, but the final drafts suggest O’Connor dutifully incorporated the feedback in her revisions.

The exchanges in Letters amount to a master class in technique as Gordon not only critiques O’Connor’s own fiction (sometimes line by line), but also breaks down the method and style of master writers. She unfolds the intricacies of narrative voice in Flaubert, perspective in Henry James, the setting of scenes in Joyce, dialogue in Faulkner, and so on. The most important breakthrough, though, is O’Connor’s growing sense of her vocation— and not mere talent—as a writer. In 1951 she writes, “I don’t really like to write, but I don’t like to do anything else better.” After two years of corresponding with Gordon she says, in a strikingly different tone, “It scares me to death when I think how good the Lord is to give you a talent and let you be able to use it. I re-resolve to become responsible, and to Madame Bovary I go.”

The two would exchange critical evaluations of great writers, living and dead—shared appreciation for James, ambivalence toward Waugh, and concern over the religion of Joyce and Faulkner—but only Gordon could speak at length of spending her time with them. While writing from Rome to O’Connor, who was hobbling on crutches in Milledgeville, the contrast of their situations must have struck her and she writes, “But damn it, it is maddening to see the Eternal City withheld from you and wasted on [others less appreciative] . . . If it’s any comfort, may I say that I think that as a writer you have what the medievals called ‘infused theology’—and I guess one doesn’t get a gift like that without paying for it.”

18 | WINTER 2020 / FORMA

Book Review

O’Connor, who could be frank about her illness but never complained of her suffering, seems to have taken Gordon’s proposed economy to heart. At any rate, by 1961 she writes to another friend that “I think anywhere that more than three writers are gathered together the atmosphere is liable to be unhealthy.” If the remark doesn’t convey a true conviction, it at least signals her discovery of a silver lining to isolation.

During periods of good health O’Connor could travel to speaking engagements or to visit friends, though the effort greatly taxed her. Between these brief trips and regular reception of guests at Andalusia, she managed to meet many of her correspondents, including Gordon. And though their relationship would continue to ripen chiefly on paper, at a distance, ripen it did. Early in their acquaintance Gordon can speak impersonally about O’Connor as a young artist who “has some dire illness and may die.” Over more than a decade of interaction, though, Gordon comes to know the gory details of her friend’s worsening illness and a sympathetic O’Connor reads between the lines as Gordon endures the end of her marriage to poet Allen Tate and her daughter’s tempestuous mental health.

Gordon remains O’Connor’s essential editor and literary counselor (“Whenever I finish a story I send it to Caroline before I consider myself really through with it”), but by the time they exchange their final letters in July of 1964 Gordon has playfully detached her “pedantic” critical persona (“Old Dr. Gordon”) in an apparent effort to underscore the personal affection that now characterizes much of her attention to the woman dying of lupus. True to form, however, Gordon’s letter includes thousands of words of feedback on “Parker’s Back.” And yet, she sees a possible end approaching. “I—or rather that old Dr. G—have been writing to you as if you were in the pink of health. But your doctor may have discovered, by this time, that there is a bit of work involved in the writing of fiction and may have forbidden you such effort.” O’Connor, lacking the strength for revision, remarks “I did well to write it at all.” She would die early the following month.

Though lightning doesn’t always strike as close together as it did with Good Things Out of Nazareth and The Letters of Flannery O’Connor and Caroline Gordon, epistolary collections like these are appearing on at least a yearly basis. The well still seems deep and undrunk, too. Faber & Faber’s attempt at a complete edition of T.S. Eliot’s letters has already run to eight volumes with three decades of his life still to cover. The poet Donald Hall, who died only last year, spoke of still spending hours each week writing or dictating letters. Fat years inexorably give way to lean years, though, and no corner of the West portends to be producing the next generation of letter writers.

For all of our advancements in communication, we also have yet to produce a fitting successor to the letter. The personal diary can be an adequate human record, but is limited in its mono-logic, its self-focus. Email is no better, if my own “Sent” folder is representative. Newer forms of communication have made the very idea of communication so ubiquitous that no single exchange is worth much to posterity. Because we can say whatever we need to say whenever we need to say it, we never say much.

Apparently, my fear was already shared by some in O’Connor’s lifetime, but she balked at it:

I have just finished reading a piece in the Commonweal by a man named Lukacs who says there’s no more literary correspondence and that good writers don’t pay any attention to the young ones because there’s no more charity among them. This has not been my experience. I think of your detailed letters to me about my book and wonder what makes him so sure of what he says.

If she’s right, and the requisite charity and willingness still exist, then perhaps unlooked-for “good things” are still forthcoming from other Nazareths like Milledgeville. If they are, their value cannot be overestimated. Two decades after O’Connor’s death, her literary acquaintance Father Robert McCown wrote to Sally Fitzgerald (who had edited her friend’s letters),

I just finished The Habit of Being and am now taking stock of the marvelous gifts it has bestowed upon my heart and mind. I am still in a kind of amazement as I try to assess the incredible depth and variety of graces that have been bestowed upon this young woman of such limited environment and experiences, of such short and restricted life.

That two more volumes have come into the world proclaiming the same good news deserves a prayer of thanks.

Letters of Flannery O’Connor and Caroline Gordon | UGA Press | $32.95

Good Things Out of Nazareth: The Uncollected Letters of Flannery O’Connor and Friends | Penguin Random House | $16.99

Sean Johnson teaches humanities at Trinitas Christian School in Pensacola, Florida. He is an Associate Editor for FORMA.

FORMA / WINTER 2020 | 19

Book Review

A Complicated Dialogue with a Literary Giant

By Heidi White

Balm in Gilead: A Theological Dialogue with Marilynne Robinson is a book that holds hidden turbulence. Published in April 2019, it is composed of transcripts from Wheaton College’s 2018 theology conference, which examined the work of respected contemporary author Marilynne Robinson (author of, among other books, Gilead, for which she won the Pulitzer Prize in 2005). On the one hand, the book is a straightforward collection of essays by (mostly) Evangelical intellectuals about Robinson’s portrayal of Protestant America. If you are a reader who prefers to tread lightly on the surface of things, that is perhaps all there is to see. Simply allow the essays to curate your judgments of Robinson’s work and move along.

But for those willing to go beyond unquestioned responses, the book gets a lot more interesting. There is a lot to love here, but unless you accept the underlying cultural and theological assumptions of American Evangelicalism, much of the book is as likely to feel like a dialogue as Uncle Barney setting you straight about Trump at an awkward family dinner. Not that the contributors are disrespectful of Robinson; in fact, they clearly hold

her in high esteem and, more often than not, articulate her spiritual questions and theological positions with accuracy and honor. But, almost without exception, each contributor toes the Evangelical party line, often dismissing Robinson’s nuanced spiritual contemplations using the very theological gauntlets that she attempts to challenge in her work. Along the way, however, many contributors forge paths into the beating heart of Robinson’s incarnational world, identifying threads of embedded mercy and mystery that entwine Robinson’s work. Featuring contributions by leading intellectuals in Protestant America as well as a few guests from other traditions, the essays address such diverse topics as theology, civil rights, nature, painting, racial divides, metaphysics, psychology, and preaching. Some contributors make almost frantic attempts to explain and correct theological matters, while others accept Robinson’s world on its own terms, offering insights into understanding her larger theology and philosophy. Perhaps unwittingly, then, Balm in Gilead scrutinizes more than Robinson’s canon; it sheds light on the paradoxes embedded within Evangelical Protestantism itself. The book is a fascinating study in the fractures and bonds of theological subcultures within Christendom. However, Marilynne Robinson seems fully in tune with that dynamic, while the Evangelical presenters seem less aware that they represent a subculture, often choosing instead to use their theological framework to make final judgments on Robinson’s orthodoxy rather than engage the

20 | WINTER 2020 / FORMA Book Review

subtleties Robinson uncovers in her work. Thus, Balm in Gilead becomes not only a commentary by leading Evangelical intellectuals on Marilynne Robinson, but also on themselves.

Robinson is, of course, a literary giant, a contemporary intellectual of the first water. A premier novelist and essayist, Robinson is well-known for her fictional contemplations of American religious life. Her trilogy of novels, Gilead, Home, and Lila, trace the complex lives and relationships of mainline Protestant clergy in small town America. In her essays, Robinson addresses issues of religion, social justice, theology, and philosophy with both precision and nuance. She is a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and was, until recently, an English professor at the prestigious Iowa Writer’s Workshop. In 2015, she was interviewed by then-President Barack Obama about her life and work. The following year she was included in Time Magazine’s “100 Most Influential People.” But in spite of her success Marilynne Robinson is no cultural conformist in either the secular or the religious realms. A curious blend of committed-Calvinist and progressive social-justice-advocate, Robinson defies stereotypes. She both represents and challenges Protestant America, speaking for the very underlying institutions that she often incisively confronts throughout her work.

On the other hand, Wheaton College is a premier bastion of Evangelical conservatism in higher education. A deeply respected liberal arts university, Wheaton boasts such graduates as Billy Graham, Jim and Elisabeth Elliot, John Piper, and Josh McDowell. Founded by Christian abolitionists in 1860, Wheaton continues to staunchly uphold historic Evangelical orthodoxy, principled public service, and academic excellence in the midst of a fragmenting culture. Dozens of other Christian universities have abandoned orthodoxy in favor of progressive theology, but Wheaton maintains its conservative identity. One of the ways it does so is by actively resisting encroaching liberal ideas; thus, Marilynne Robinson’s musings on the intersections of faith and mystery potentially verge on taboo positions at Wheaton, a dynamic which in many ways presents a microcosm of the wider Evangelical culture.

The result is curious: a response from Wheaton Evangelicals that attempts to honor an author they clearly revere while at the same time ensuring that they defend their theological positions. An example of this dynamic is found in Dr. Keith Johnson’s essay “The Metaphysics of Marilynne Robinson,” in which Johnson explains Robinson’s rejection of the sacrificial atonement of Christ. Robinson takes a position closer to Eastern Christianity, which understands Jesus’ death and resurrection to

be one unified act of extravagant love aimed at defeating death rather than an act of atoning sacrifice that pays for sin. Johnson presents Robinson’s argument based on her wider metaphysics, but immediately argues against it on his own terms, which are theological, not philosophical. In other words, he counters a metaphysical position with a theological one. Moreover, he ignores the underlying metaphysical quandary that Robinson presents: namely, since God sets the terms for human existence, why require a blood sacrifice at all? Dr. Johnson never addresses this thorny question; he simply presents his own position as the correct one. He also makes an extraordinary claim: “For most of Christian history, the crucifixion has been understood in sacrificial terms as an atonement for human sin,” a statement that discounts Eastern Christianity entirely and Western history partially. To his credit, this is a fracture in Christian theology that goes back to St. Anselm of Canterbury, circa AD 1100 (before which the Eastern position was dominant), so it is a divisive issue in Christian thought worthy of frank contemplation.

Examples like this abound. However, the laudatory tone of each essay indicates that in spite of some overstated dogmatic pronouncements and sometimes questionable scholarship, every essay is presented in good faith from professors and theorists who discover something in Robinson’s work that moves them within their particular academic framework, creating many delightful snapshots of illuminating grace throughout the book. One contributor suggests that readers utilize the trilogy of Gilead novels as a thought experiment—like Schrödinger’s cat—on the doctrine of predestination. Blinking a bit, I wondered what novel Robinson, who is indeed a Calvinist, might write next if she went through the trouble of writing a novel of such magisterial subtlety as Gilead in order to be an exploration of the U in TULIP. I suppose it actually works, if you think about it. Dr. Patricia Andujo from Azusa Pacific University presented an incisive paper on “Marilynne Robinson and the African American Experience,” in which she invites the American church to become “co-sufferers” with Christ on behalf of marginalized peoples. My favorite essay, “Heaven and Earth: Reading Gilead through the Landscape of the Fox River,” by painter Joel Sheesely, describes the slow grace of physical geography on souls, describing how “the witness of nature presses on John Ames and slowly forces on him the ‘sour sap’ of his moral judgment on Jack Boughton.”

Moments like these make Balm in Gilead shine. The book wavers between pedantic theological territorialism and flashes of interpretive brilliance. The pendulum indicates that beleaguered American Evangelicals just don’t know what to do with Marilynne Robinson. Her novels are so compelling, her statements of faith so clear, her

FORMA / WINTER 2020 21

Book Review

essays so insightful, and her kindness so palpable that American Protestants want to embrace (or perhaps to be embraced by) her, but are not sure what to make of her expansive Christian humanism, inclusive social ethics, frank acknowledgement of the mysteries of faith, and sacramental vision of the created world.

The rising pressures within Evangelical culture shed light on the respectful but ambivalent responses of the contributors to Robinson’s work. Evangelicals are mired in a tough spot in this cultural moment. Once honored in American life, today they are under ideological attack by the larger secular culture, while at the same time enjoying mostly secure social and economic standing. It is a strange and mutable, though dominant, American religious subculture.

Although Robinson’s novels feature characters from mainline Protestant traditions rather than Evangelical ones, Evangelicals also find their own entangled faith experiences, longings, anxieties, questions, and wounds reflected by Robinson in her stories and musings. But Robinson, like all great novelists and essayists, does not

Next Issue Coming in March

Local Culture: A Journal of the Front Porch Republic is published semi-annually. It is dedicated to the conditions that best conduce to human flourishing: the virtues, political and economic decentralization, localism, liberty, respect for natural limits, tradition—especially the humane tradition in arts and letters—and living arrangements built to human scale. We welcome you to subscribe and read along! https://www.frontporchrepublic.com/localculture/

idealize the experiences she portrays, but probes the ruptures within souls and societies. For an Evangelical culture in flux, it is hard, but necessary, to engage in the contemplation of ruptures. The essays I enjoyed most were the ones in which the contributors joined with Robinson in acknowledging the mysteries of faith rather than attempting to wrestle her nuanced meditations into submission to their accepted doctrines. After all, as Robinson expresses so beautifully, “we have to hope that God is a great deal kinder than we are.”

Balm in Gilead: A Theological Dialogue with Marilynne Robinson | IVP Academic | $28.00

Heidi White teaches at Collegium Study Center in Colorado Springs. She is a regular contributor at The Close Reads Podcast Network, the host of the FORMA Podcast, and the Managing Editor of FORMA Journal

22 | WINTER 2020 / FORMA Book Review

An Invitation to Remember the Classics

By Greg Wilbur

In 2011, Anthony Tommasini, the chief classical music critic for The New York Times, wrote a series of articles that attempted to determine the top ten composers of all time. He invited readers to be part of the process and received quite a number of replies and comments in what was a stimulating and engaging conversation. By the time Tommasini was done with the project, he knew that he had a lot more to say about the composers and works that he loved, and The Indispensable Composers, a full-length book of personal reflections, was the fruit of that exercise.

Much like a conversation between friends about your Mount Rushmore of films or favorite desert-island books, the process of making a list helps clarify what you value and prioritize. When making such a list, do you choose composers (or authors or films) that you enjoy or that you know to be objectively good or that have an element of nostalgia for a particular time or state of mind? By what criteria should composers be ranked? Should they be ranked according to the degree that they are well known? Should the revolutionaries who changed the musical landscape be ranked higher? Tommasini is quick to note in the subtitle of the book (A Person-

al Guide) that he is adding his subjective voice to the conversation—at which point the text not only acts as a guide to a substantial list of composers and their works but also as insight into what Tommasini personally values. He settles on Monteverdi, J.S. Bach, G.F. Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Chopin, Robert Schumann, Verdi, Wagner, Brahms, Debussy, Puccini, Schoenberg, Stravinsky, and Bartok.

Tommasini asks, “But what is greatness in music? Does it matter? Does there need to be a greatest composer in history? Does the canon expand? And who gets to say what is canonical now?” He writes:

Often a composer seems not at all to be striving for greatness in a work, as with those lovely Grieg piano pieces. A composer might simply think: I’m just practicing my craft, working out something that’s been kicking around within me. Now, if it’s considered great, well, wonderful. Actually, it’s hard to know if the giants in the arts consciously aimed for greatness. Did Shakespeare? From what we understand, he thought of himself as a professional, a man of the theater. Did he write those plays hoping they would endure? I doubt it, which may be why so many of the scripts were left in jumbled states, with missing pages and confusing rewrites. In a way, even Beethoven, who really did strive for greatness, conducted his day-to-day life as a professional musician.

FORMA / WINTER 2020 | 23

Book Review

So with these things in mind, Tommasini sets out as a guide to the composers and works that he believes are most significant. Along the way, he introduces readers to the life and context of each artist, their most substantial compositions, what to listen for in their work, and personal reflections about interacting with the works of the composer. Since Tommasini is self-consciously inserting himself as a guide, his credentials in that role merit attention; he is well suited for that task as a musician, performer, and critic. He studied music at Yale and later earned a Doctorate of Musical Arts from Boston University, wrote several books on music, and made multiple recordings of piano music. His assessment is astute and his descriptions of what is happening in a piece of music are precise and inviting.

Claudio Monteverdi is the subject of the first chapter, which is entitled “Creator of Modern Music.” This starting point reveals a couple of Tommasini’s inclinations that are confirmed throughout the book: his love of opera and his affinity for the common practice period (essentially music from the Baroque onward). He defends his starting point by saying, “In truth, starting this survey with Monteverdi may be somewhat arbitrary. Still, he strikes me as the first towering figure with whom we, composers and audiences alike, can identify today.” Monteverdi is also credited with composing the first real opera. Tommasini does take time to introduce the reader to musical terms and developments such as describing counterpoint as a term that

refers to music written in two or more independent lines, or voices. The lines have to go together harmonically, of course. But linearly and rhythmically they must have independent natures for a passage to be considered contrapuntal . . . The challenge for audiences today, when we hear, say, a Renaissance motet or sacred work, is to orient our ears to try to hear complex contrapuntal music the way it was perceived at the time. Renaissance listeners found pleasure in trying to discern multiple lines unfolding simultaneously.

These descriptions are helpful along the way, especially if someone is hoping to fill in some gaps in their musical knowledge.

Tommasini moves on to J.S. Bach in the second chapter, which he calls “Music for Use, Devotion, and Personal Profit” and in which he praises the accomplishments of Bach: “He showed us all, not just the musicians of his time, but of all time, that we had not fully realized the ramifications of what we already knew. In all fields, true profundity comes from immersive examination. No com-

poser has ever looked at music more deeply than Bach.”

In addition to talking about Bach the composer, Tommasini covers the reception of Bach’s music and performance issues on into the twentieth century. He recognizes that particular performers and recordings shape our understanding of a composer’s music such that it is natural for Tommasini to bring up specific performers (“If you want to know Bach the questing giant, Bach the composer who probes deep in the essence of music, listen to Anderszewski play the Partita No. 6 in E Minor”) and recordings (“Gould’s 1955 recording of the Goldberg Variations took listeners on a nonstop adventure”).

In chapter 4, Tommasini turns his attention to the “Vienna Four” (Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert) and returns to the theme of advancement in the development of music. He writes astutely that he has “never quite bought into the concept of music as an art form that advanced over time to increasingly higher levels of modernity and sophistication. Of course, bold, radical innovations kept coming, but these shifts did not necessarily make music any greater, just different.” He makes helpful connections to intellectual movements that influenced changes in music from the Baroque period to the Classical period:

Another crucial characteristic of Viennese Classicism concerned what can be called the grammar of music, which came to resemble the grammar of language. The more complex forms of music in the Baroque period utilized almost continuously flowing contrapuntal writing, with lines spinning out and chugging along. By the mid-eighteenth century, the periodic phrase, as it was called, became a favored way to speak in music: long phrases were structured out of shorter ones, much the way sentences are structured out of clauses. As many historians have argued, this emerging musical characteristic reflected the Age of Enlightenment, or at least the idealized notion of the Enlightenment that was touted at the time: a movement that championed reason, logic, and discourse.

These types of passages assist the reader in making larger connections between what was happening in music history as well as in general history and philosophical thought. Tommasini also does a very good job of giving context for who these composers were and how their personal life affected their art—heresies, illnesses, mistresses, political intrigue, sexual orientation, and family issues. While these details humanize the composers and their struggles, they also raise some interesting questions for those who have only encountered the composers in

24 | WINTER 2020 / FORMA

Book Review

children’s biographies or sanitized curriculums. Thus, we have passages like this:

Over the years I’ve come to feel that Schubert’s experience with his sexuality—his strong drives and chronic torment, his coping mechanisms—profoundly impacted his music. That he might have been homosexual may in fact open up some mysteries about his music. In many Schubert works … you often have the feeling that what you are hearing on the surface is not what it seems; or, to put it another way, that Schubert composed in a kind of covert language, like someone speaking in code.

Or this:

Even during an era when anti-Semitism permeated European cultural and political circles, especially in Germany, Wagner’s strident prejudices stood out. For him, all of what he viewed as superficial, ostentatious elements in contemporary music were attributable to the influence of Jewish musicians … Wagner argued, in the words of the scholar and critic Barry Millington, that “the rootlessness of Jews in Germany and their historical roles as usurers and entrepreneurs” have “condemned them, in Wagner’s view, to cultural sterility.” Wagner believed that German art had to be protected from this corrupting Jewish influence.

We discover along the way that music history and the lives of composers are far more messy, nuanced, and complicated than we perhaps normally allow. This fact deserves thoughtful consideration. While Tommasini writes thoroughly and helpfully in discussing some of these lesser known details about composers’ lives, he does not provide any value judgments or extensive commentary. In my opinion, the details Tommasini provides are some of the most helpful elements of the book in sparking discussion about the perspective from which composers sought to

push the boundaries and norms of music and morality.

Yet, because the personal nature of the selections and the interaction with the composers and their works unapologetically represent the preferences of the author, the book favors too narrow a period. Tommasini’s reason for starting with Monteverdi and the Baroque is that the modern listener can identify with this music—thus leaving out medieval and Renaissance music and some of the greatest composers who ever lived. No work can be exhaustive and portable, but there does seem to be an unusual weight towards opera—and your mileage may vary. At times the personal anecdotes provide context and other times they are distracting and a little self-serving.

The invitation that Tommasini makes to consider the great composers and their works causes me to think through who might be on my own list. If I limited myself to just ten, they would include: Josquin des Prez, Palestrina, Thomas Tallis, Heinrich Schutz, J.S. Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Stravinsky, and Richard Strauss. Tommasini’s charisma gives a spark to this tour through his list, but it is an uneven list all the same. I might attribute his preference for Chopin, Schumann, Verdi, Puccini, and Schoenberg to his favoritism toward opera and piano music, and so question their inclusion—although I personally appreciate several of them, especially Puccini. My own list also reaches back to pivotal composers in periods ignored by his. The debt that later music owes to figures like Tallis and Palestrina leaves me to conclude that, while Tommasini has mounted a learned and engaging meditation on what makes a composer “great,” he has ultimately thought too little about what makes them indispensable.

The Indispensable Composers: A Personal Guide | Penguin Random House | $20.00

Greg Wilbur is Chief Musician at Cornerstone Presbyterian Church in Franklin, TN, as well as Dean, Co-Founder, and Senior Fellow of New College Franklin. He is the author of Glory and Honor: The Music and Artistic Legacy of Johann Sebastian Bach

If your bliss intersects with contemporary culture and classical thought, then follow it. We'll do the rest.

FORMA / WINTER 2020 25 Book Review

WANT TO WRITE FOR FORMA?

formajournal.com/contribute to submit original essays, reviews, and poetry.

poetry, the arts,

more.

Visit

We're always looking for thoughtful writing about books, teaching,

history, and

Aprolific writer, G.K. Chesterton’s works range extensively from economics to theology to fiction. Among his most widely popular works are a series of short stories about a Roman Catholic priest with a keen interest in mystery and an overwhelming desire to save souls. Originally published in a variety of magazines, the Father Brown stories first appeared with the classic “The Blue Cross” in September 1910. Since then, Father Brown has become one of the most recognizable figures in detective fiction, arguably surpassed only by Sherlock Holmes. Much has been written about Father Brown himself, yet an incredible story also appears as readers examine the evolution of Father Brown’s first antagonist, Hercule Flambeau. The notorious criminal Flambeau embodies the evolution of Chesterton’s own religious beliefs as demonstrated by Flambeau’s depravity, conversion, and sanctification.

In his Autobiography, Chesterton describes the inspiration for the Father Brown series. After meeting a congenial priest named Father O’Connor, Chesterton was struck by the priest’s sophisticated knowledge on a variety of topics. Once as they were walking, Chesterton revealed to Father O’Connor a theory about which Chesterton was contemplating writing. The priest, however, politely explained the fallacies associated with Chesterton’s theory. The priest hesitantly cited the depths of human depravity as evidence. Chesterton recalls that “it was a curious experience to find that this quiet and pleasant celibate had plumbed those abysses far deeper than I. I had not imagined that the world could hold such horrors.”

Following this enlightening conversation, Chesterton and the priest once again found conversation among a group of college students. The priest and the students discussed a number of topics ranging from sports to music. The students were impressed, as Chesterton himself had been, with O’Connor’s depth of knowledge. But after the priest left the room,

Chesterton was stunned by the students’ ongoing conversation: “All the same,” one of the students remarked, “I don’t believe his sort of life is the right one. It’s all very well to like religious music and so on, when you’re all shut up in a sort of cloister and don’t know anything about the real evil in the world.” In this singular moment, the concept of the Father Brown detective stories was born.

While Father Brown’s character is based loosely on O’Connor, Flambeau’s antagonistic character demonstrates the evolution of Chesterton’s own spiritual journey. Introduced as a notorious jewel thief, Flambeau provides a surprising means for Chesterton’s confessions. In his essay “How to Write a Detective Story,” Chesterton explains that “the detective story is only a game; and in that game the reader is not really wrestling with the criminal but with the author . . . ” and that “the first and fundamental principle is that the aim of a mystery story, as of every story and every other mystery, is not darkness but light.” This light shines as Chesterton develops Flambeau’s character throughout the series.

In fact, the name “Flambeau” itself may signal Chesterton’s intention. Flambeau is derived from Middle French and means “a flaming torch.” The torch is not the light itself, but the bearer of the light. Thus, Chesterton’s character serves metaphorically as a torch that shines the Light into the darkness of human depravity.

In his biography of Chesterton, Lawrence J. Clipper suggests that Father Brown himself was “perhaps Chesterton’s only fully developed fictional creation” and the only one of “lasting interest.” On the contrary, Flambeau’s character is much more fully developed than some readers initially realize and certainly provides the necessary framework for “lasting interest.”

In his Autobiography, Chesterton acknowledges the depth of his own youthful imagination and the extremes of his moral understanding: “There is something truly menacing in the thought of how quickly I could imagine the maddest, when I had never committed the mildest crime.” His imagination certainly inspired many of the exploits on which Flambeau

FORMA / WINTER 2020 | 27

embarked. Chesterton confesses that “it is true that there was a time when I had reached that condition of moral anarchy within.” He describes his youth characterized “with the morbid imagery of evil, with the burden of my own mysterious brain and body.” Flambeau’s crimes are mostly non-violent thefts, but Chesterton’s dark imagination is clearly at work. Each of Flambeau’s crimes “was almost a new sin, and would make a story by itself.”

In “How to Write a Detective Story,” Chesterton provides an important clue regarding his own confession of sinfulness represented by Flambeau: “The ideal mystery story is one in which he is such a character as the author would have created for his own sake, or for the sake of making the story move in other necessary matters, and then be found to be present there, not for the obvious and sufficient reason, but for a second and a secret one.” Flambeau provides Chesterton an outlet for his inner depravity to be unconstrained by real consequences. As “the colossus of crime” and “the outlaw,” Flambeau’s reputation as the “archangel of impudence” certainly precedes him. Flambeau reveals his true identity in “The Blue Cross,” and the sin of pride clearly surfaces. Railing against his outwitted opponent, Flambeau insults the “little celibate simpleton” as laughable as “a three-act farce.” Father Brown, however, reveals the first clue to Flambeau’s true identity: the spiked bracelet, an insignia declaring his membership in a criminal community. The exchange mirrors the episode Chesterton described earlier with Father O’Connor. The inspiration is plainly reflected in “The Blue Cross” as Brown and Flambeau debate.

While explaining his discovery in “The Blue Cross,” Father Brown suggests a devious method Flambeau could have used to attain his purposes. We learn that Flambeau’s depravity had not reached such depths of sin to learn about “the Donkey’s Whistle.” Chesterton does not explain what the Donkey’s Whistle is nor how it is implemented, but context clearly indicates its association with an extreme depth of evil not yet encountered by the notorious Flambeau. Father Brown exclaims: “Oh, you can’t have gone so very wrong yet!” As Father Brown discovers, Flambeau, though burdened with sin, is not beyond the reach of God’s grace. Flambeau is redeemable.

Yet at the end of their first encounter in “The Blue Cross,” Flambeau does not repent of his sinful ways. He reemerges in “The Queer Feet,” and Father Brown subsequently confronts him: “I am ready to hear your confession.” The priest stresses the need for confession and repentance, hallmarks of the Christian faith. Though Flambeau still does not repent, he returns the stolen goods before fleeing the scene. When later asked if he had caught the suspect, Father Brown responds with wisdom that echoes Father O’Connor: “‘Yes,’ he said, ‘I caught him, with an unseen hook and an invisible line

which is long enough to let him wander to the ends of the world, and still to bring him back with a twitch upon the thread.”

In “The Flying Stars,” Father Brown calls out into the darkness: “‘Well, Flambeau’ says the voice, ‘you really look like a Flying Star; but that always means a Falling Star at last.’” The priest begins his third attempt to convert the infamous criminal: “I want you to give up this life. There is still youth and honour and humour in you.” Recognizing the redeemability of the wayward Flambeau, Father Brown continues his appeal. “Your downward steps,” warns Father Brown, “have begun. You used to boast of doing nothing mean, but you are doing something mean to-night . . . But you will do meaner things than that before you die.” The words pierce Flambeau, and suddenly three stolen diamonds fall to the feet of the priest. This third encounter proves transformative. The next reference to Flambeau is in “The Invisible Man” where Flambeau is no longer the culprit. He is described as “an extremely clever fellow, who has set up in business” and “though his youth was a bit stormy, he’s a strictly honest man now, and his brains are now worth money.” Redeemed!

After his experience with Father O’Connor, Chesterton reflected: “It brought me in a manner face to face once more with those morbid but vivid problems of the soul, to which I have earlier alluded, and gave me a great and growing sense that I had not found any real spiritual solution to them. . . . They still troubled me a good deal.” Chesterton’s own conversion evidenced years of internal struggle between good and evil as reflected in the fictional Flambeau. For Chesterton, that final step came in 1922 when he was received into the Catholic Church. For Flambeau, that step came between “The Flying Stars” and “The Invisible Man.”

Incredibly, Flambeau’s conversion receives little attention from Chesterton. In an article called “The Mystical Vision of Father Brown” for FORMA’s online side, Sean Johnson explains how evil becomes commonplace, but good creates an even greater mystery. “In Chesterton’s economy of mystery,” Johnson writes, “human evil is typically boring and usual, while it is human goodness that can surprise and astonish.” Thus Flambeau’s conversion signifies a plot twist in the series.

Though given a new direction, the repentant Flambeau finds it difficult to outlive his criminal past. He puts himself under the tutelage of his new mentor, Father Brown. While Flambeau’s experiences give him a unique perspective for solving mysteries, he yields to Father Brown in the areas of faith. His newfound humility is clearly evident: “‘You must tell us all about it,’ said Flambeau, with a strange heavy simplicity, like a child.” This humility is a far cry from the notorious jewel thief who

28 | WINTER 2020 / FORMA

Years ago, an acquaintance said that the stories of Father Brown were "too Catholic." I took that opinion as an indicator that the stories were deformed by doctrine. Given how many mystery stories there are in the world, why would I choose to read stories that served goals external to the story? Fortunately, a lovely new Penguin Classics edition caught my eye. The surprise was that the stories are simply stories. They are clearly written by a religious man, and their star's own religious beliefs ground their every move, but the religion here is additive to the art, not destructive of it. These are delicate little puzzle mysteries that are lifted above the game of their plots by Father Brown's awareness that sin is everywhere, men are fallen, the world is imperfect, and that our actions matter not solely because, but additionally because, they have eternal consequences. His sympathies are those of someone who cares deeply about this world while keeping an eye on the next. That Chesterton conveys this with a combination of world-weariness and wonder, that the stories are above all clever and fun, is a marvel. —Levi

Stahl

Stahl

ridiculed Father Brown as a celibate simpleton during their first meeting; it’s a mark of genuine transformation. The teaching of humility is clearly a defining characteristic of Father Brown and his influence. In his Autobiography, Chesterton routinely expresses this growing sense of humility in his own life: “The only way to enjoy even a weed is to feel unworthy even of a weed.” Flambeau’s humble, childlike trust of Father Brown is key to his ongoing sanctification.

Over time, Father Brown’s influence becomes even more apparent. Flambeau’s notorious crimes and conversion both occur within the first five of fifty short stories, yet the vast majority of references to him describe his spiritual growth. Chesterton gives Flambeau a nod of progress in “The God of the Gongs,” describing Flambeau as Father Brown’s “old friend” who was an “ex-criminal and ex-detective.” This, of course, does not mean Flambeau has obtained a degree of sinless perfection. Indeed within the same story, Flambeau wrestles with racial prejudices and he even sympathizes with a murderer. Overall, however, Flambeau’s character is portrayed in an increasingly positive manner throughout the Father Brown series. He settles down by marrying a Spanish woman, having children, and retiring. Chesterton also reveals that Flambeau and the priest “had corresponded constantly, but they had not met for years.” Their friendship endures the test of time and distance, not unlike Chesterton and O’Connor’s.

Chesterton later notes that Flambeau had given up his assumed name “Flambeau” for his birth name “Duroc.” He writes that the name Flambeau, meaning “the torch,” is “like that under which such a man will often wage war on society.” Though intending to wage war against society, Flambeau ultimately becomes a bearer of the Light that brings peace, demonstrating Chesterton’s use of paradox. Flambeau’s character, though, is now too humble to keep the paradoxical name. This change is not without meaning: “Duroc” signifies “any of a breed of large vigorous red American hogs.” Identifying himself with a breed of swine, Flambeau’s humility continues to grow.

In “The Secret of Flambeau,” Flambeau confesses: “‘There is a criminal in this room,’ he said. ‘I am one. I am Flambeau, and the police of two hemispheres are still hunting for me.’” When Flambeau refers to himself as a criminal, he uses the present tense. But as Chesterton refers to Flambeau’s criminal activity, the author uses the past tense. Flambeau internalizes his past sins, but Chesterton (as Flambeau’s creator) has forgiven Flambeau’s sins, as demonstrated by use of the the past tense. So Chesterton confesses his sin, but also experiences forgiveness from the “God with the Golden Key.” Flambeau’s confession continues highlighting the role of Father Brown in his life: “I stole for twenty years with these two hands . . . Only my friend told me that he knew exactly why I stole; and I have never stolen since.” Having been essential to his conversion, Father Brown also continued mentoring the convert, critical for Flambeau’s sanctification.