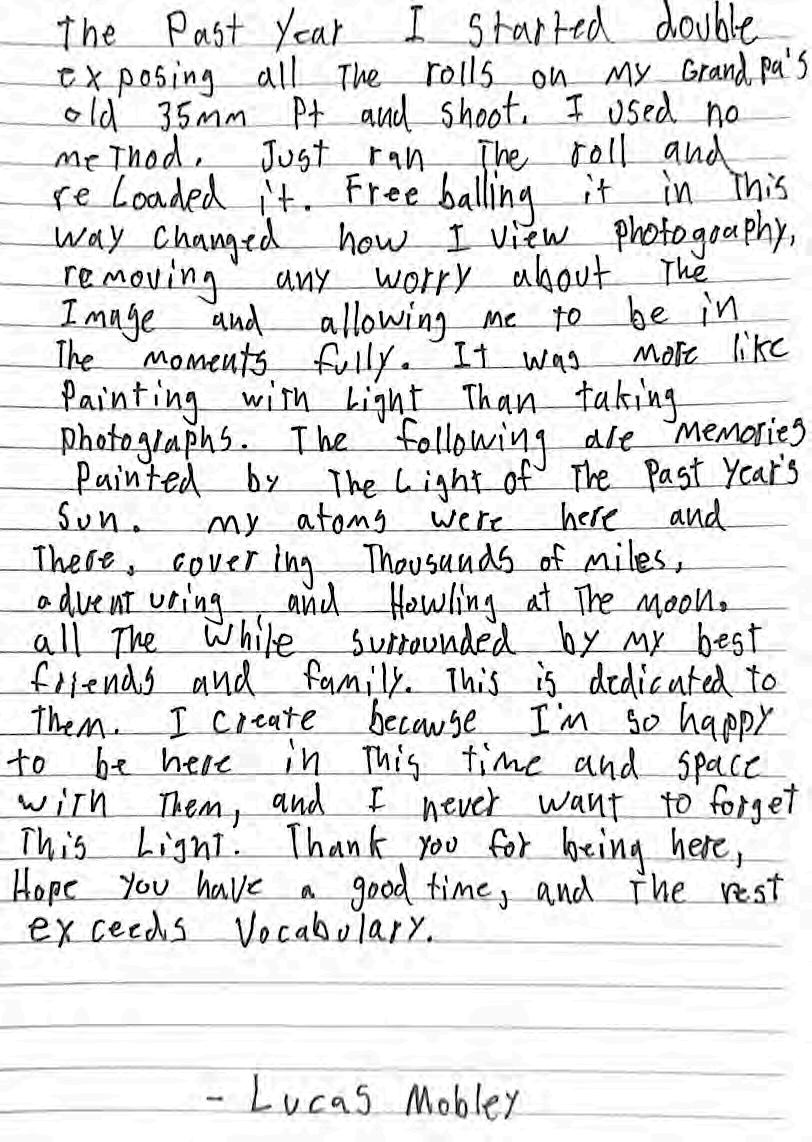

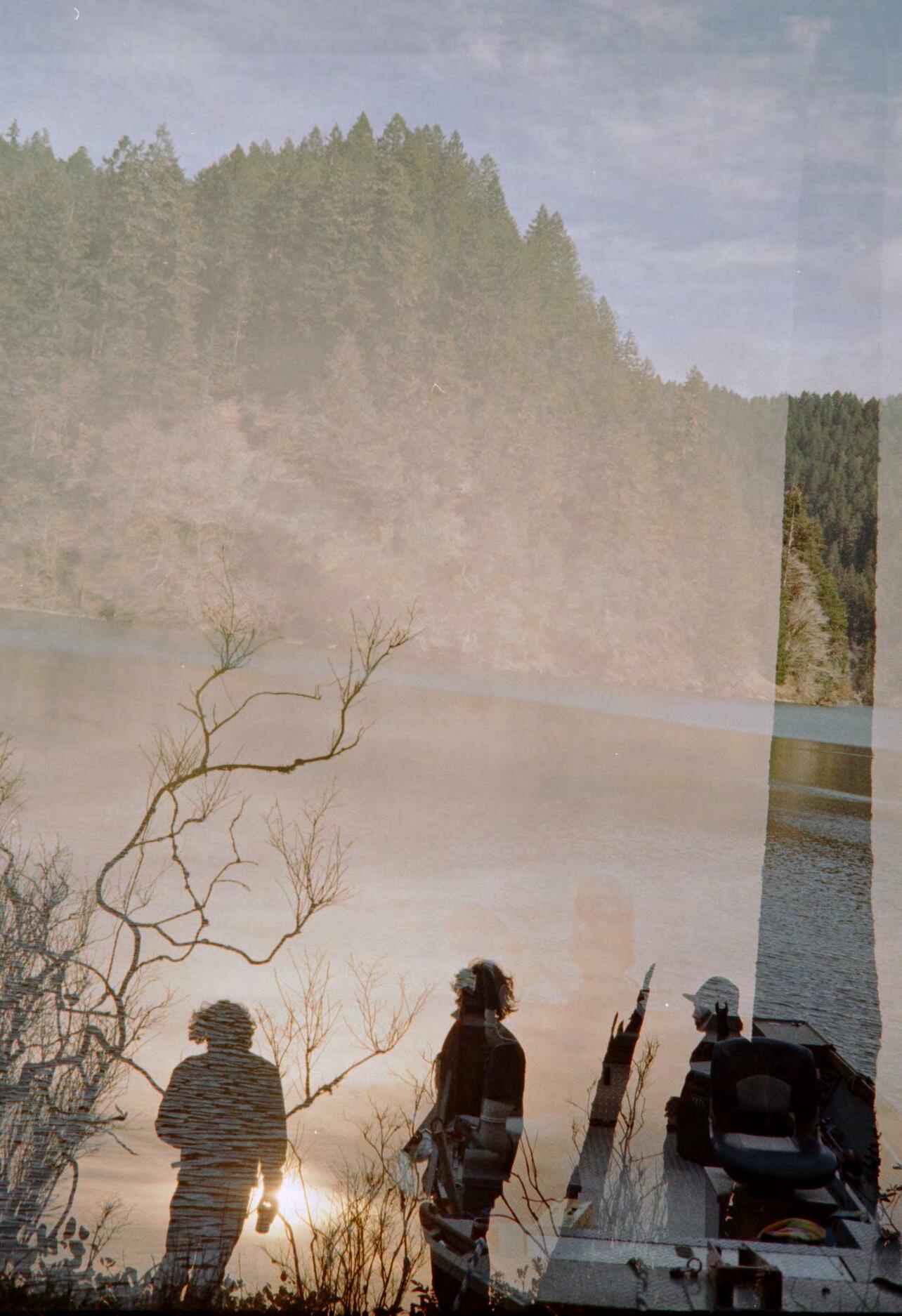

ON WHY WE CREATE

CHUCK MAGAZINE IS PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES. ALL IMAGES CON TAINED WITHIN THIS PUBLICATION ARE THE SOLE COPYRIGHT OF THE PHO TOGRAPHERS AND ARE PROTECTED UNDER INTERNATIONAL COPYRIGHT LAW. NOTHING MAY BE PRINTED, COPIED OR REPRODUCED WHOLLY OR IN PART WITHOUT PRIOR PERMISSION FROM THE EDITORS

2021 CHUCK MAGAZINE. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The journey is part of the experience — an expression of the seriousness of one’s intent. One doesn’t take the A train to Mecca.

Dear Finley,

What makes something made of? Whether it’s a garden, a day at the beach, or a delicious greek meal with lemon chicken and enough tzatzi ki to sedate us both. All these things are made up of little parts coming together to create something uniquely whole and beautiful. I think about those little parts often, the right wood that hasn’t been rained on, the biggest beach towel so everyone has a seat, and the freshest dill, to make sure nothing is less than perfect.

The little moments in making this magazine have always been the reason to create this. To sit with all of these artists and have open and honest conversations with not only them but with each other. That to me feels like the greatest possible gift. The excitement after leaving an interview, with our film all rolled, both smiling ear to ear with the hopes of what will be. The tedious act of transcribing each interview, but the beauty and joy of hearing our conversations once more. It will always be the laughing for me, the joy of sitting together and compiling this magazine that keeps me coming back. Finding together what each page will become, piecing the stories and images of what we will eventually hold in our hands.

You can’t put your arms around a memory, but we can try to capture the beauty of light on celluloid, and we can try our very best to create some thing with the vulnerability and the trust the artists within these pages showed us. None of this was easy, by no means did we do it alone, there were missteps, as there should be. But ultimately a mistake is worth the lesson, so long as you learn it. All I hope we do with this issue, with every issue to come, is continue that learning, to question it all, and to never assume we know what is to come. Because when each copy of Chuck is lost to the sands of time, when they lay in our children’s children’s attics, as some relic of the past, I know that the moments of creating this, with you and all our friends, will be far beyond the spine of any one magazine.

It always ends too soon. See you around the next one.

Dear Achilleas,

I’m sitting and writing this letter on the patio of your brother’s apart ment in Brooklyn, New York. As Chuck 3 is finally coming to a wrap, I can’t help but think about what the closest thing is to that beautiful feeling of making a magazine. I initially thought it was something similar to biking over the Williamsburg bridge full speed, road tripping up to Oregon, or even a forever night with Tommy. I think I’ve come to the realization that it’s not any single act but rather the way we story the past. It’s all of us sitting around the fire and talking about the 7+ years of the craziest shit in the world happing and laughing so hard all along the way. It’s looking back at all those beautiful ephemeral moments that are just always over too soon. You really can’t see the moment you’re in until it’s just about over, which is a shame isn’t it. I’d like to think Chuck was born out of a similar mentality, storying the past. But its multiplying fecundity would suggest it is not just a magazine documenting the past, but rather one foretelling the future. Future Chuck. I’d like to think of it as the Benjamin Button of printed magazines. Fast and loose, wise and handsome. Sounds like you and Aristo. I couldn’t choose which letter I wanted to use so here’s a poem I wrote with Willie Nelson and Bobby D.

Dear Achilleas,

May god bless you and Chuck Magazine.

May all your wishes come true. May you build a ladder to the stars and climb on every rung. May you stay forever young.

May you grow up to be righteous and to be strong. May you always know the truth and the light surrounding you. Cheers to my best friend and a magazine that keeps on making itself. Cheers to the dads. Cheers to the future.

Long live Chuck.

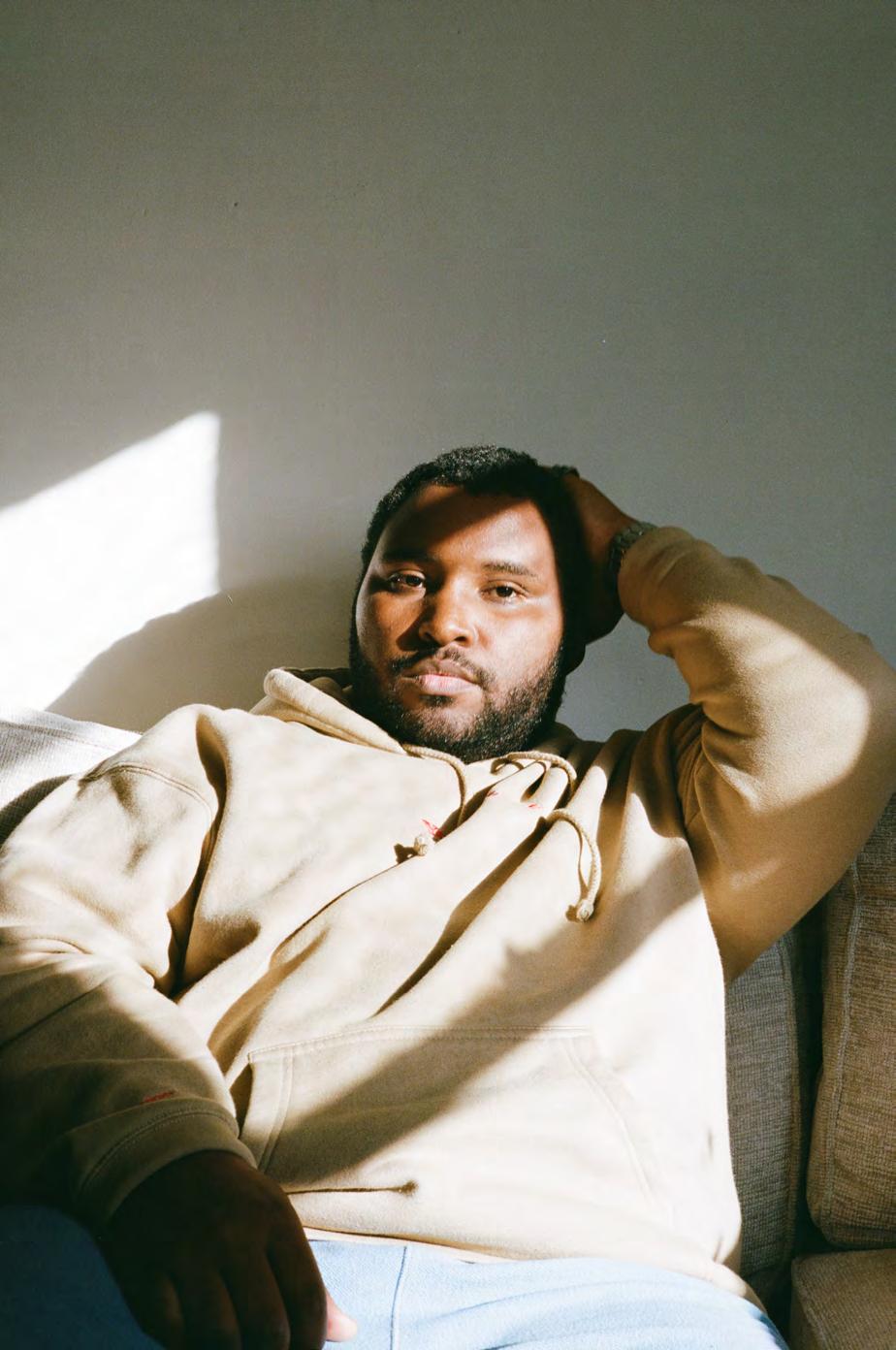

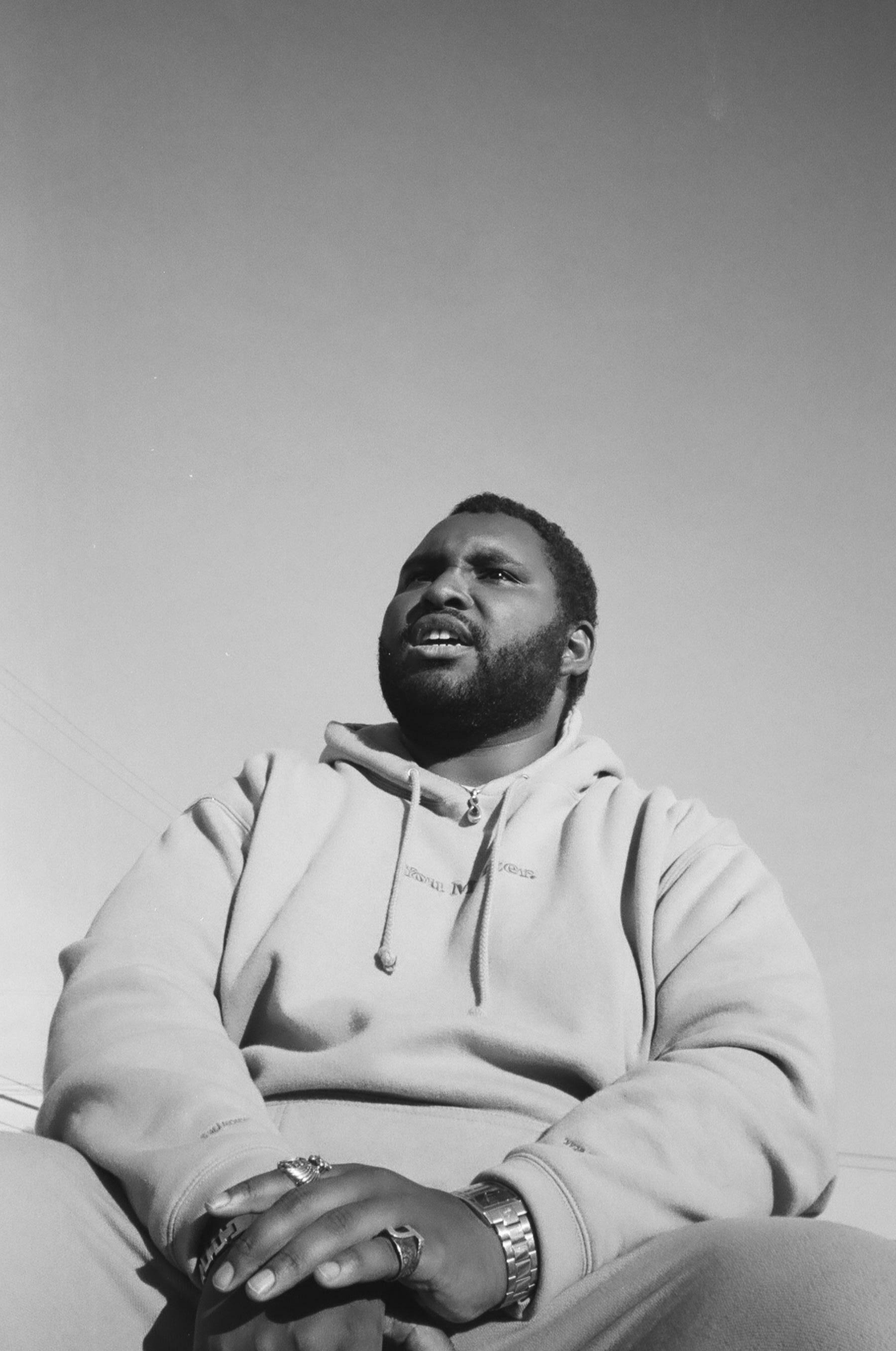

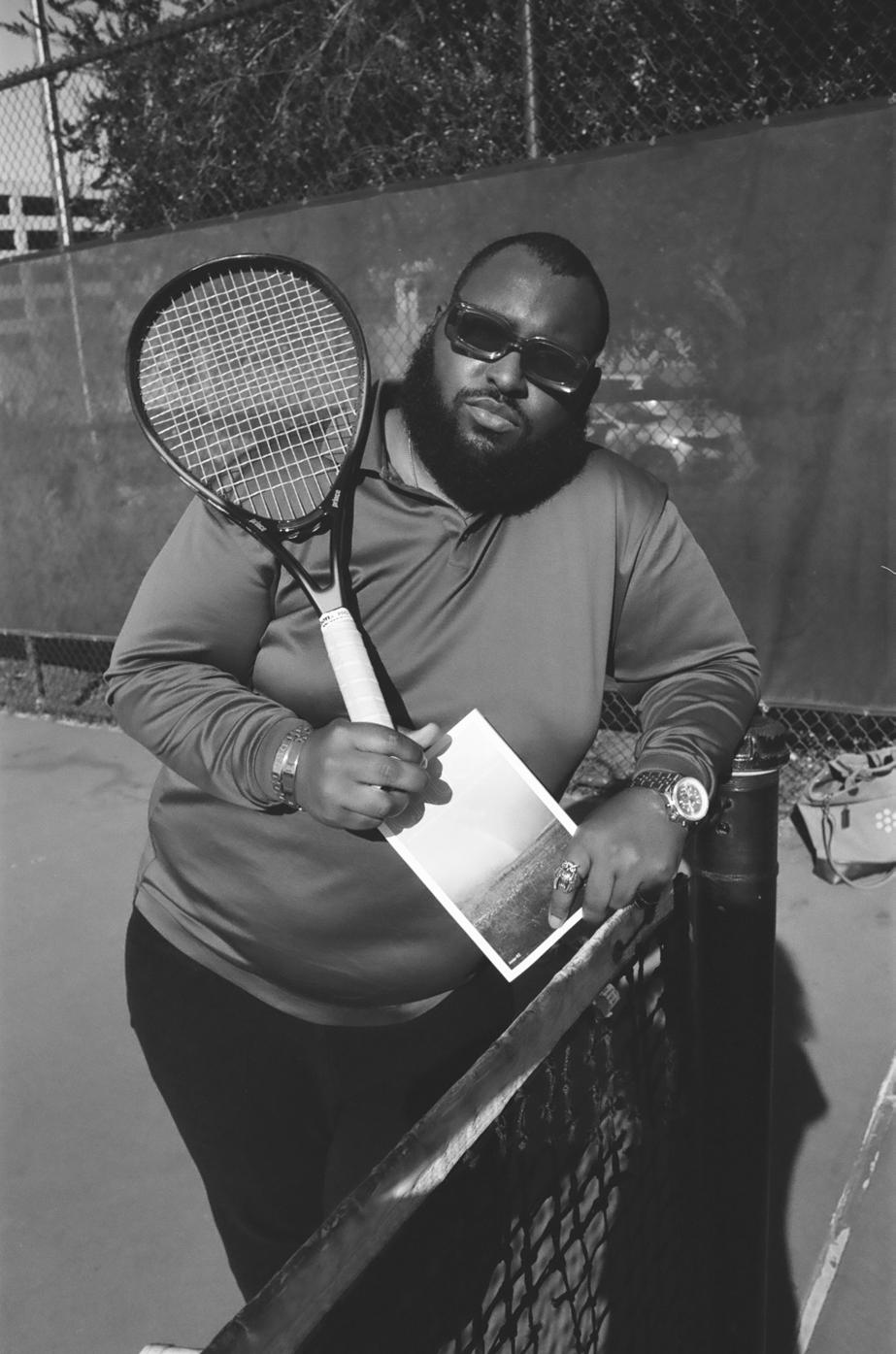

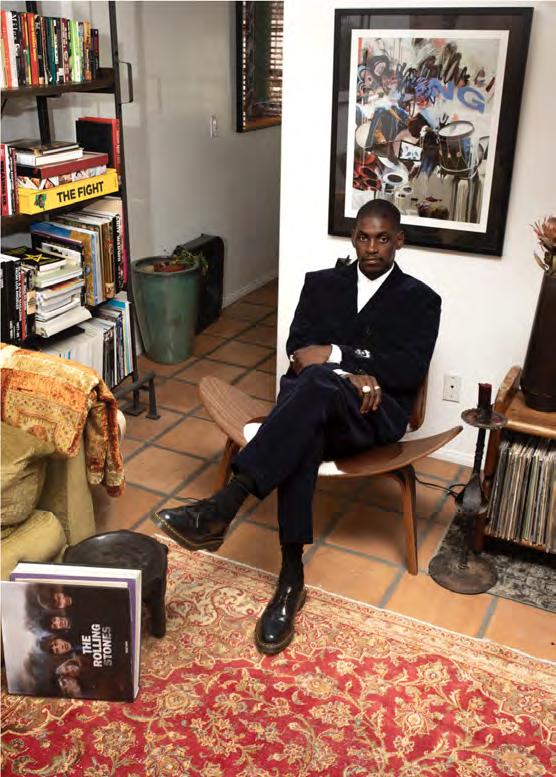

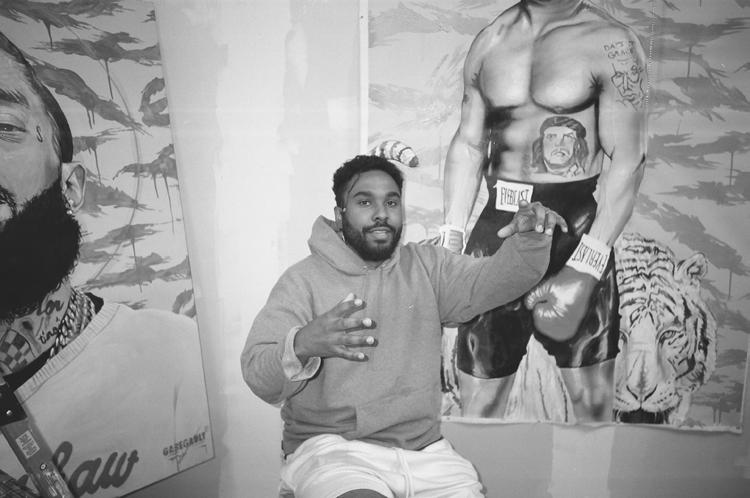

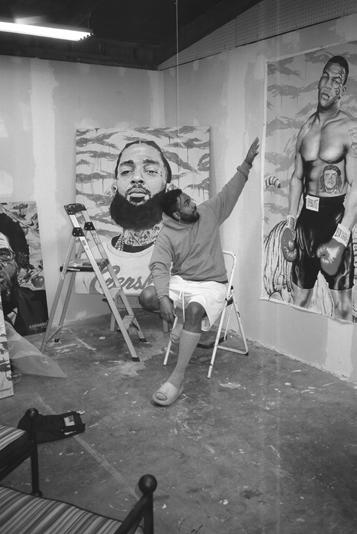

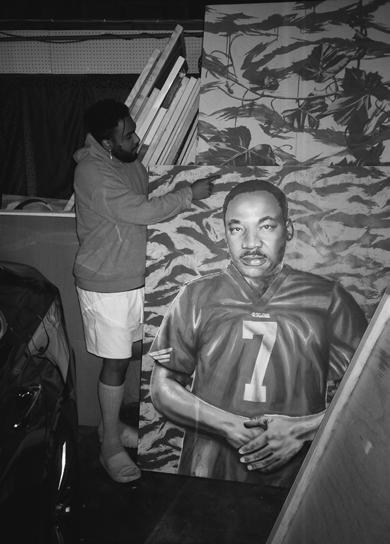

Jordan I Garrett, or J.I.G. LeFrost, was our first interview for this issue. There is always that feeling before knocking on the door or calling to let someone know we’ve arrived, where you get bursts of doubt, the feeling that you haven’t prepared enough, or thought of the most accurate questions. With Jordan, as soon as he opened the door, that all melted away. He opened his home and his soul to us in a way that still to this day moves us when we read this interview. Some people were born to tell stories, and we believe Jordan is one of those people. We sat in his living room watching the sun pass through his stained glass windows as Jordan told us all about his life with laughter, immense loss, and most stunningly, his complete and absolute openness in seeing the world for the beautiful mess it is.

How did you find music?

I was on the poetry stuff early on, I started drumming when I was in the sixth grade. Rapping started because when I started high school at Branson, I always really wanted to do JTS (Junior Talent Show) be cause in my eyes, every year the headline performers always looked like they... can I curse a little bit?

Say anything you fucking want.

It looked like the guys who closed always got all the bitches. So sophomore year I was like, I gotta get a good routine, I start ed talking to all my friends, saying “What are we gonna do?” We’re sophomores, they’re telling me to chill, the year goes by, I’m still pressing about it. And then over summer, I go “alright, guys, what are we gonna do?” And they said, “We are going to be glow in the dark stickman. We got costumes, we’re doing these crazy fuck ing dances.” They’re sending me videos of them, I go, “Oh shit, that’s gonna be crazy. When do I get my costume? You know, I’m a little wider than you guys. I’m gonna need a special fit.” And they go, “We already got our routine and everything... What are you gonna do for JTS Jordan?”

Damn...

I thought that those guys were gonna hold me down.

Yeah. What the fuck am I gonna do, the option was being a techie or coming up with a performance. And I’m an egotistical piece of shit. So I’m performing. I think, Oh, they’re gonna swipe me? I’ll blow you out of the fucking water. So I went on YouTube and took a beat and started writing to it. And I wrote and wrote, and a week before the talent show I showed my Dad, and he

just said, “Son, this is the worst shit I’ve ever heard in my life.”

No way! [Laughing]

[Laughing] He was like, “Yo, you suck.” My Dad was very fucking honest. Especially because it was a very white school.

Yeah, probably 90% white right?

Exactly, I was the biggest black kid at the school. So he was like, “If my son gets up on stage and raps like this? I can’t go back.”

Oh my god, yeah.

And I was like, “Ahh Dad fuck off this is al right.” I did the audition, and it was terrible, I didn’t remember any of the words, I was reading off the phone. I was super scared, it was my first time performing in front of people. Afterward, the teachers, they’re looking at me saying, “Alright, very good job.” And I thought I did pretty terrible. So later they announced the line-up, and they put my ass last.

You’re the closer! So, you thought this was your moment?

No... I was like, What the fuck did I do? I gotta do this in front of the whole school? I went home, I told my dad that I was going to be closing the show. My Dad was like, “With that, oh, God...” So he sat me down and he went bar by bar with me and showed me how to structure a song. My Dad does not make music, he didn’t rap or anything. But he showed me, “Alright, this is structure, you have to have this repeating refrain here, you need to do this here...” I rewrote it a bunch of times and then got something kind of decent out of it. Then the day of the show was when I actually memorized it...

I still remember it dude. It was notorious, I was a freshman, it was probably a month into school, and you closed it out with every one surrounding the stage. Was it from that day on, a star was born? “I’m a rapper?”

I had friends who had recording studios in their homes. After that performance, they would say come over and record. I would try to coordinate with them, I would show up at the house and be waiting for two hours, and they would be just drunk or high. I’d wonder why they weren’t perform ing the way I wanted them to. They’d be so out of it, and at that point, I was like “This is bullshit.” And I would tell my dad, “I want to focus on music, I want to do this.” He always said, “Why don’t you work with the people who are taking you seriously?” I didn’t understand they were high, so I just thought they wouldn’t work with me... and you gotta know, I was an innocent child, I didn’t grow up drinking, I didn’t grow up doing drugs. All that stuff was surrounding, but I didn’t participate in any of it. I was in an education program called “Making Waves.” The program was every day after

school from fifth grade to the end of high school, I came in to study, do homework, and learn SAT words. From three to six during the week and on Saturday, from ten to two, I would just be in school or the program always, so I didn’t get the oppor tunity...

To get high after school, or to mess around, there was so much structure.

Exactly, so I didn’t have time to meet friends or collaborators or anything. For me, everyday was waking up and working, and then coming home and sleeping. So I barely saw my Dad.

What was your Dad doing when you were growing up?

My Dad is an entrepreneur. I got to grow up watching him my whole life, he was a software genius. Self-taught. This was when computer’s first dropped — I’m watching him read software books every night. He started a company called Vianovus which was a project management system. They

managed multi-billion dollar budgets for construction projects. My whole childhood was just watching him code and watch ing real business. Then he had to sell his business in 2008 because I broke my leg. He was about to sign the insurance papers when I broke my leg, but he never did so he had to sell his company.

What happened?

I can be hyperbolic in my expression, but I like to think that it’s fun. But, that led to the staff not believing me as a child when I broke my leg. I was playing basketball, absolutely just uber-confident, the whole gym looking at me, I’m talking shit. I planted my foot to go to a reverse layup, and my knee muscle ripped off a piece of my bone. Instead of going up, I just col lapsed. Everyone is laughing, “Ah, Jordan fell, that’s hilarious.” And I was sitting there just thinking, Oh shit, this doesn’t feel right. I was trying to get up and I couldn’t put weight on it, I couldn’t walk. So they call my Dad and they tell him I’m being dramatic, so my Dad didn’t sign the insurance papers because he’s thinking it’s nothing. When he came to get me, he saw I was just dragging my foot. He was like, “Are you okay?” And I was like, “I broke my fucking leg, nobody here believes me.” So he took me straight to the hospital, and they do scans but still don’t believe that I broke it.

You’re kidding me, the hospital didn’t believe you?

Finally, they call a specialist who comes the next day. I had to stay in the hospital overnight. The specialist came in just like “Wow, that’s so broken.” We didn’t have insurance to cover it and they did surgery on my leg. I was in there for I think a week and the bill came out to something crazy, like $600,000.

Holy shit. Yeah. So my Dad had to sell his company to this bigger company. After he sold it he started working for UC Berkley, paying for my school, paying for fucking living somewhere, you know, food, and I think it just came out to nothing. Even though we’re supposed to be middle class, it was a signifi cant change from how I grew up.

Yeah, how do you think that changed you, or the way you saw yourself?

I always grew up idolizing entrepreneur ship and business, and I grew up watching him run business meetings, writing himself checks. He never brought girlfriends around or anything, so for him, it was all work. That was how my brain was conditioned, I knew I wanted to be an entrepreneur, and the University of Oregon had the best fucking entrepreneurship program in the country, like, top five or some shit. I applied early. I knew that’s where I wanted to go and when I got in they gave me the out of state tuition cost. It was $60,000. I tried scholar ships and everything but eventually, I was talking to my Dad just saying, “I don’t know how I feel about spending a down payment on a house to learn how to buy a house.” Once it became clear I couldn’t do it, I start ed applying to a bunch of different schools, I just kind of went to University of Santa Cruz. While I was in Santa Cruz I started doing more music and music just amount ed to a lot more than anything I was doing academically. And my Dad always would just tell me, “Whatever you do, don’t go into fucking debt.” And then the first quarter of the sophomore year it was just getting tough financially. I wouldn’t even have money after my scholarship. So I just said “fuck it, this isn’t the place, I’m done.”

Was it at that point that music took on a more significant role in your life?

In Santa Cruz there is only one venue, it’s called the Catalyst, they have a main room that fits 1000 people and a small room that fits around 350. I opened for Blackalicious in the main room. A few months later a different promoter hit me up to perform at Rage Cage. I performed in front of a shit ton of people, it just kind of started to snowball from there. Then I did my own shows, decided I wanted to plan a tour because I had experience in front of 350 people and I knew I could move a crowd. I started booking venues and shit for myself and just kind of kicked everything into overdrive. I just wanted to perform whatever and wherever I could, so I got to open for other big acts, and I started to go to the Bay Area a lot more and start ed making a community for myself. Just through performances.

It’s crazy to hear about this super intense growing up, a very regimented schedule, watching your Dad be very hard working. Having that intense educational base, wanting to go to school for Business Man agement. It’s a beautiful way of finding the music because it wasn’t you saying, I’ll just try it and see how it goes. It was a very serious decision to do the music, there was no fucking around.

Exactly, I couldn’t fuck around like that, there was none of that. Everything for me was ultra discipline, I know it doesn’t look quote-unquote right because I don’t do it the conventional way. I’m looking at everything from a business-oriented perspective, so early on, when I was 18 or 19, that shit turned off a lot of people. I had a management deal, and my big gest thing was, I wasn’t a great rapper yet, I was a great performer. It made my manager really, really unhappy, I definitely know I pissed him off a lot because I don’t just listen and take. I inquire. “Why are we doing this? What is this gonna do? I don’t like the way this is going...” They wanted to

do a Twitter strategy with me and I didn’t like it, so, at one point in the middle of our contract, they just stopped talking to me. I’m a people person. I’m not an inter net person. Spotify has a playlist called “Internet People,” which is cool. I’m happy for them. I’m never gonna be the coolest guy on the Internet. People are gonna like what I have to offer because it’s a different energy. It’s a human energy.

Absolutely, it comes out in talking with you, so once you were out of Santa Cruz what did you do?

In early 2017 my best friend and collab orator, Neel passed away randomly. And after Neel passed, I did this tour I had planned, I went up and down the coast — San Francisco, Oakland, Los Angeles, San Diego — when I came out of it I spent the rest of my time just with his mother, his family, and his girlfriend, just mourning my friend. And that took a lot out of me and my creativity.

It’s a collaborator, you lose that connection and you lose that artistic voice.

I didn’t know what to do, he was the most amazing guitar player, he could hear some thing and just play it immediately. Then after he passed, I just felt lost. So in 2017 I started doing creative direction, basically teaching other people how to rap and how to move in the industry. I would help out a lot of young rappers and producers. I put my own creativity behind me, and I started to get really bad writer’s block. For the first time, I felt a wavering in that drive and the belief that I was made for music, you know, I had lost that. I wanted to make beautiful music, and that’s what Neel and I were doing. I was being really honest, and this is a big trigger for me, but nobody cared... And I’m really in tune with that if I see nobody cares. I’m out.

If nobody cares, you can feel like you’re just yelling in the void.

Then, my Dad went on a trip, he came back, and he just died. The night I ended up taking him to the hospital, I was trying to write music, I was writing and I heard a thud. I came into the room and saw my Dad on the floor, and he couldn’t breathe. So I called the fire department, they came and took him to the hospital. They sent me to the wrong hospital. So then I’m calling every fucking hospital in the Bay Area. Eventually, I found out where they took him, so I went and he was doing alright, he was lucid a little bit. And this is just a very common thing with black people, but doctors will find everything other than the issue that’s wrong with you. So they’ll go, “Oh, he’s an alcoholic? Does he drink a lot? His liver is not working?” And I’d say, “No, my dad would have a glass every three months.” Or “Oh, is he diabetic?” “No, he’s not diabetic...” They kept trying to figure out all these things that were his fault that could be wrong with him.

Can’t you just figure out why he’s sick?

Exactly, I kept trying to talk to the doctor in person, the doctor wouldn’t meet with me. He died two days later. I woke up to the hospital calling me saying, “Your father passed away 10 minutes ago.” And I was like, “Why didn’t they call me? I’ve been trying to talk to a doctor...” I could go on for a while about how much I fucking hate... not the people who practice medi cine, but the system.

I’m so sorry.

I appreciate it. Thank you. That was August 2018, and I just lost Neel in 2017, so I just stopped. I moved in with my godparents. I was working on other people’s albums, they are doing great, while my shit is terrible. I’ll never forget my girlfriend was

sitting in the room with me while I tried to make a beat and I was just like, “Wow, I hate this. I suck at this. This is terrible.” So I just felt, Alright, well, I guess I’m gonna move to Los Angeles. So I did. One of the first engineering sessions I had was with Warhol. I was struggling to engineer for him because he was so fast, and I hadn’t dealt with that kind of speed. I wasn’t prepared for Los Angeles at all, but I did it, it went well, and I got paid. I kind of turned in overdrive, I started freelancing for a bunch of different studios, all my gear’s mobile. I’d just take my shit around all Los Angeles. I started moving up and up and up and up. I was assisting Soulja Boy’s engineer and I got to watch how fast he recorded.

Just speed. All of this is going into how I ended up reclaiming myself as an artist, I learned that speed is your most precious resource. That’s all you have, because that’s your friction against the clock. We’re all gonna die. You’re gonna get rich, but how fast are you gonna get rich? Cash today is worth more than cash tomorrow. Because tomorrow, they’re going to take my one dollar per song and turn it into five cents a song, and it’s only going to get lower, depending on the new platform. Look at this country, a million dollars today is not a million dollars in 2000. A million-dollar house today is kind of ass, you know, I like to look at Zillow.

Yeah, to peruse around.

I’m gonna need a bit more than a million for a nice house [laughing]. But Soulja Boy didn’t say anything, he didn’t remember me a single time I walked in this house. But watching him exist and move was a catalyst for me internally. Soulja Boy is one of the pioneers in rap music for finding these Atlanta guys. He was one of the first people

to work with Migos and Famous Dex. The way that he records is very much in line with what people in Atlanta are doing, like Young Thug and a lot of others we all hoist up as some of the most creative people. I saw that he was just doing every song off the top of his head, in 20 minutes, and it sounds pretty fucking good. So what the fuck was I doing?

Right, why am I sitting here waiting and thinking, and not making?

Exactly, I felt like a fucking idiot. How am I gonna make a better song if I’m not mak ing more songs? So I started freestyling, I remember once in high school I freestyled with Lucas Mobley [see page 102], and there were some baddies around. I free styled, it was just awful. They were like, “Oh, he’s terrible.” Since then I never had done it seriously. But after seeing Soulja Boy work I have been freestyling every thing I release. I’ll just freestyle and then go back and edit and freestyle. That’s my writing process now.

Your drive is really admirable because there are a lot of rappers who just fall into the ego or drugs or whatever it is, seems like people can get so far away from the work, but you’re so focused on the process itself.

This is where the system of being able to filter out people in terms of sharing songs comes in. Because meaningless feedback doesn’t help you realize how to make the song better, right? It comes down to the people who are around you. When I was in high school people were telling me, “Yeah, this is good.” But nobody’s telling me what’s wrong or how it can be better. That’s the biggest thing.

So you would say it’s about the speed but also the quality of the content?

When it comes to rap the baseline is speed in my head. All of the things that I do are just about being as fast as possible. I know I’m probably one of the best rap recording engineers. Just number one, I have the vibe. That’s like 85% of it, but the X-Factor, 15% how fast are you? And because I’m a super nerd, I learned how to produce, how to en gineer from the internet, nobody taught me. I’m releasing songs so frequently because I want to build a catalog. What is my family going to eat off or what am I going to eat off of? I own all of my songs because I’m not signed to anyone right now. So, if something crazy happens tomorrow and I get huge and sign a record deal...I don’t have to give up my catalog, I own it. So, they blow me up and I still own all of my music.

It seems you’re consciously building some thing. You know where you are in the big picture of your career.

I think of myself as a creator, I think of stuff and I make it. A lot of people are creative. So many people are creative. Oh, great idea. Can I see it? Can I touch it? Can I hold it? I try my best to sit down and just make things happen. You know, this rap shit, nobody sat me down and was like here’s a pen and paper, here is your textbook. I’ve been cre ating everything on my own, from the tour when I was 19 or pretending to be someone else when emailing venues, and negotiating better door deals for myself than established artists.

Maybe it took your best friend and your fa ther passing away, for everything to be taken away, for you to say, “Alright, fuck doing this for everyone else. Fuck waiting at the kid’s house for two hours while they’re getting high. How am I going to do this for me? How am I going to put myself on because I know nobody else will...” And nothing against them, but I got to do this for me, because I’m look ing around and I don’t think anyone else will.

Exactly, and that’s really what it came down to is I couldn’t see for myself. There’s a song I grew up listening to with my Dad on the WWE soundtrack, there is a line that goes, “You can’t see the forest for the trees. You can’t smell your own shit on your knees...” I couldn’t smell the shit on my knees. Everything I thought was a strength was a weakness and ev erything I thought was a weakness was a strength. Once I started putting it in perspective everything changed.

How did your friends react to this change of yours? It takes courage to do that.

I know people don’t listen to me. I know that actively the people around me don’t want to accept that I have done some thing that’s really scary. Because when I showed people this new shit, they were looking at me so fucking different. The best way to explain it is I couldn’t tie my shoes as a little kid. I tried so fucking hard. I would fucking bawl and cry and my Dad would be like, “I’m not teaching you, tie your fucking shoes.” It’s some thing that should just come naturally, and then one day I went down there. I just tied them, it was like “look at you go.” That’s how most things in my life have been like, you know, I try and try and try, then I wake up one morning, clear headed, and boom. I can do it. I’m confident in a way that isn’t normal. I feel like there are two kinds of confidence. There’s attractive confidence, and then there’s whatever the fuck I have. I’ll call it, unattractive confidence. Attractive con fidence is when you walk in a room, you look good, you’re smooth, you’re suave, you got the mystique and the magic. You walk in and people go, “Oh, damn, that nigga nice.” Nobody has ever thought that when they see me, and I’m okay with that for now. Right now what they see is my unattractive confidence, which is, I’m working and you see it. There’s a big glass fucking door in front of me and I am chiseling away at every fucking piece of whatever it is that I want to create.

People look and think, “Why are you doing it that way?”

Cool confidence never came naturally to me. All I’m doing is learning every day. I think it just makes a lot of people uncom fortable. I’m comfortable being uncom fortable. If you were sitting here...

And it was a terrible fucking interview with stupid questions.

Yeah, I’d be fine. Picking your nose the whole time? I’d be fine. I grew up ex periencing the lowest of the lows, even before music and everything my Mom was in and out of jail growing up. She sold drugs, she wasn’t around. I lived with her for three years and it was terrible. Niggas was hungry. I was watching drug deals. I’ve lived the experience people talk about in trap music, right? So I can walk into session tomorrow, and niggas could have guns, everything, which I’ve been in before, and it doesn’t faze me. I’m comfortable being uncomfortable, I know I’m good because I know nobody is gonna have a problem with me. My learning is so public, I will throw some shit on the wall because that’s how you’re supposed to learn. What, you’re gonna look cool learn ing? You’re a fucking idiot if you don’t get in the mud so you can wash yourself off and look great after. That’s what life is about. So many people I know want to act cool and they haven’t learned, where’s the progress? It’s fear of failure. Fuck that shit, I’d rather fail in front of a shit ton of people than try nothing.

I think there’s something about creative people who have experienced loss. You sort of look around at the world and you see the people who try to hide the trial and error but are never really honest because of that fear of failure. That’s okay, but when you have an intense loss, you have to face that right in front of you. You look around and think, We all could be gone tomorrow. All this talking and acting cool is just for show. There’s that feeling of, I don’t give a shit if I look like an idiot, I don’t give a shit if you don’t like me, or don’t think I’m cool. Because I know that you can lose every thing. And when it goes it goes.

Yeah, you know, me and Neel weren’t prepared. He had a whole project we were working on. And where is it right now? We weren’t prepared for him to die. My Dad, you know, I wasn’t prepared to lose so much.

You have a song called “Self Care” that we love so much, that tackles a lot of that loss in the music video. Can you speak a little on this?

I was going through a really tough time that year. I was doing therapy and every body was telling me to do self-care and that Mac Miller song “Self Care” was out. And I just felt, I don’t know what that means for me. The song was me trying to take care of myself in the middle of a breakdown. I had met the director Drake super randomly, a friend had introduced us, and I came to him and we talked about the video. I said, “I’m gonna shave my head.” You know, because that’s what people do when they’re going through tough times. They shave their fuckin heads.

Britney did it.

Exactly, I was like “I’m Britney, bitch.” And you know, I wanted this visual of a black man taking care of himself. Because usually, it’s, “oh, my abs, look and me lift weights.” Never, “let me take care of myself mentally.” He had the idea of me peeling off a face mask, he wanted it to feel like American Psycho. The intimacy of watching someone take care of them selves but capture the twisted element of removing your own skin. And that’s what this whole process has been for me. That’s what it feels like when I tie my shoes for the first time. It’s like I just shed a whole person. I like to think that my music is all about catharsis, it should feel like a release. Some people make songs that make you feel great, some people make

songs that make you feel sad, some people make songs that make you feel like you’re high as fuck. My songs are just supposed to feel like that moment when the rug is pulled under you, right before you hit the floor, that floating. The energy and the momen tum shift. I don’t want people to get the idea that there’s no emotion in that momentum shift, but there’s a lot that can be going through your head when you’re fucking falling. All the adrenaline rushes and you’re angry and you’re sad and you wonder why this happened? All those feelings of won der, questions, and inquisitions. What I’m working on is trying to channel that feeling into a song, and as soon as I figure out how to capture it in the purest form, then every thing clicks. So I’m just working songs until I hit that point, you know?

Then you’re home. Yeah, and then I’ll never leave it. Probably be dead by then. [Laughing]

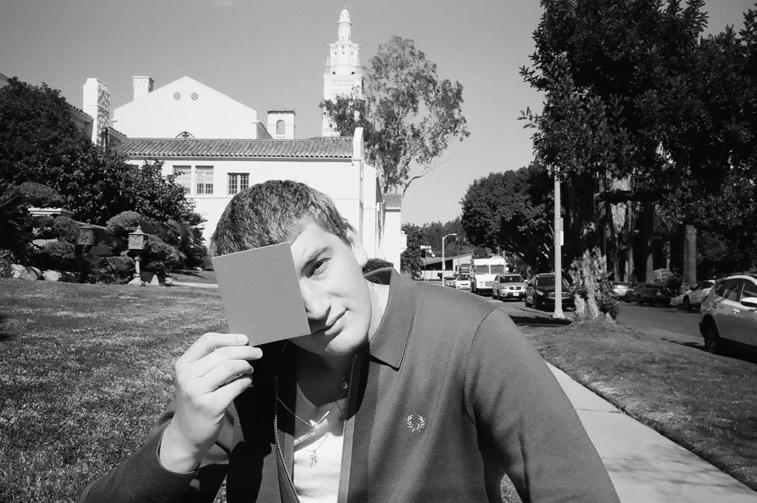

Aidan Cullen is a Los Angeles and New York-based creative. When doing an interview with someone who has such a stacking résumé, one would naturally expect a level of pretension or self-righteousness, like putting two apostrophes over resume. Talking to Aidan, you quickly realize that the kid who is doing the coolest things in the world is actually the sweetest. We sat in his finely curated mid-century modern apartment surrounded by his art and furniture, talking about film, skating in Los Angeles, and how there’s no point in doing anything if you don’t give it just about everything. Aidan described his upbringing and future aspirations, but what we found most telling is at the end of the day, Aidan is a kid who just wants to play ball.

Where are you originally from?

I’m from here—Santa Monica and Venice.

Have you been working through the pandemic?

Yeah, it’s been hard. Obviously, the first four months were nothing because you couldn’t go outside. That sucked. And then, kind of right after that, there was a crazy busy six months. I guess July to November, and then it’s been a little slow since then. Just ups and downs.

Have you always been taking photos?

I didn’t always. I used to be a pretty serious athlete.

What did you play?

A lot: baseball, basketball, soccer, and football. At the time, sports were definitely my whole life. And then I got this shitty neurologi cal disease and a few other pretty serious health things. Sports just became not an option.

In what grade did that happen?

Ninth grade. Then I had the whole “Oh my god—what am I gonna do with my life?” year. Or more like a few months?

Were you hospitalized?

Yeah, I was seeing doctors proba bly five days a week. It was crazy. And I broke my back, which was pretty serious.

Oh my god, you got caught with the house of cards just caving in.

Yeah, also had this weird cancer scare and for a few months, going through that, just a lot of bad stuff happening all at once. And then I really hurt my back, and my neurological disease makes it harder for things to heal. I tried to play sports in high school, but I was always so hurt and got a lot slower. Then, early in ninth grade, I start ed getting super into skateboard ing. I started skating and working at the shoe store, “Undefeated.”

I was working there, getting into clothes and skating, started skating heavily, and then for Christmas my dad got me a camera. And I just started shooting from then on.

What kind of camera?

First it was a GoPro, which was fun.

Truly the GoPro, that was the first? That’s awesome. Where were you skating?

All around LA honestly.

Did you ever skate at Babylon in Hollywood?

Yeah, I had a lot of friends that would go there. I wasn’t really that good at skating because I was still hurt, so I was like, “Okay, how do I add value to the crew?” So I had to be the filmer, which I was always into growing up. I always thought filmmaking was cool. Skating really made me follow it. Our crew was making a bunch of skate videos and we started a clothing company.

All this still in the 9th grade? Were you big on the skate culture, smoking and stealing beers?

I actually have never smoked weed before....

Like ever, ever?

Ever. I’m the only person from Ven ice who doesn’t smoke.

Why do you think that was, especial ly when you were constantly sur rounded by it?

It was a mixture of shit. Growing up, a lot of my friends were just massive stoners, who could not eat or sleep without smoking. They were spending all their money on weed and I was spending my mon ey on making t-shirts, [laughs] and buying cameras. My parents were super not down with it. It was never enticing and it’s still not interesting to me. Different for everybody.

I love that you had that mentality of, if I can’t keep skating I just have to find something else. I too was never able to throw myself off 12 stairs on a board.

Yeah, it’s also gnarly. We would go out for a whole weekend just for one three second clip. Then run from the cops for hours. It was su per fun for years and then when I was a senior in high school, I knew there wasn’t really a great future for me in skating.

When did you start taking photog raphy more seriously?

I took my first photo class and started taking photography a lot more seriously. By junior year I started meeting a lot of musicians, started taking portraits of them, and by the end of junior year, I was working and making some money. I was doing lookbook shoots or photo shoots or mini commercials. I was just down for whatever, as long as we could shoot.

What was your college experience like?

I went to NYU and then dropped out after three semesters because I was working. How much were you working?

By my third semester, I start-

ed missing a lot of class. All my teachers were sorta saying I had to decide: do school or do the work. And I just decided I was gonna do the work. I was supporting myself and I got a dope apartment in the city. I called my parents and basi cally just said, “Yo, all my teachers are saying I have to choose.” I had missed the maximum number of classes and they understood me choosing work. They just said, “Don’t ask us for money.” We didn’t have a ton of bread. I knew always if I wanted to buy camera gear and live in New York, I had to work hard and get myself a career. They are the most supportive parents and they saw that I wanted to be self-sufficient.

Such a crazy place to be in as a young person. Do you ever think to yourself: how is all this happening?

It was overwhelming. Also New York is pretty intense. When I moved there, I was figuring a lot of shit out and working and going to school. I feel that a lot of people underestimate how much work school is. I had that work and had to support myself. It was a lot. I was never really sleeping. But it was the most fun time ever.

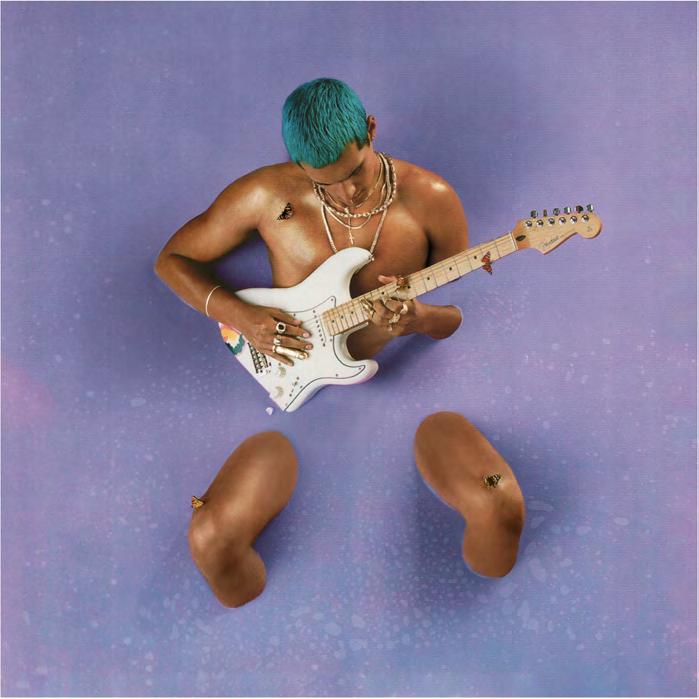

Aidan Cullen, A$AP Nast for Stussy x No Vacancy Inn

Aidan Cullen, A$AP Nast for Stussy x No Vacancy Inn

Do you feel that you’ve evolved as a photographer and director over these few years? Working with A$AP Nast and Omar Apollo, have you come to a point where you choose them or they choose you?

Definitely for the first few years there was a lot of me reaching out and going to a ton of events and meeting people. I was being persistent in a semi-annoying way, but not too annoying. But I’ve been shooting pretty seriously now for four or five years. Now it’s definitely getting to the point where I have more choice. This past year I was trying to learn how to say no more.

Really—because you have to figure out how you use your time?

Yeah, just trying to balance what the right projects are. What do I actu ally want to be doing? Obviously sometimes you do things for mon ey, sometimes you do things just because there’s no money, but you love it. The in-betweeners, I feel lately, it’s been more of me being able to choose what comes in. Just seeing what hits the email.

Is there a project that you’re most proud of?

I don’t think so, which might sound weird. It’s hard for me to say, to pinpoint. There were a lot of little things: my first commercial cam paign was when I was a senior in high school. It was this Converse campaign and there were billboards in Times Square for this collabora

tion with A$AP Nast, who I still work with and worked with fre quently when I was starting out.

Was that your Mid Century video? You shot that on film, right?

That was the first time I ever used a Super 8. We even went to the Converse headquarters and had a lot of discussions on shoe design. It was really cool being a part of that process. Looking back on it is so funny. We didn’t even color the film; I didn’t even know what that was yet. It’s been so many things. There have been hundreds of proj ects that have helped a little, some more than others. But I don’t have the one that’s like, “Oh, my God, this changed me so much.” I also have trouble celebrating—I can see that something is good or cool but I always know I can do better. Totally. Which may be semi-unhealthy, but I feel that in some ways it’s good.

Plenty of people get kind of lost in the sauce with short-term success.

I would say I’m hard on myself when it comes to making, but I’m a young artist. I’m always study ing the things I look up to saying, “This was cool, let’s learn from it.”

Do you want to start making things that aren’t necessarily reliant on other artists or commercials? Something narrative or your own?

That’s the goal: doing narrative filmmaking or TV and movies. I’m writing a TV show right now that could be really cool if it works out. I want to make some narrative shorts this year. And I’m working on a photo book; it’s been on and off for years and hoping to release that at the end of this year. It all just depends on when I’m done.

Have you done a photo show before?

Yeah, the first one I did was when I was 17. I put a group show together. I ended up selling a bunch of prints, nothing crazy but it was super fun. Then I did another little show in New York in 2017 with Fool’s Gold, this record label that I was working with a lot. I made this book called “In Between Moments of Music.” It was about photographing musicians, not onstage or in the studio, just in their lives.

Do you ever think about the fact that there is a world where you kept playing sports? You never got sick and this photo thing never happened. You could have been some lax bro at university thinking about winning the NESCAC and not how to design Converse.

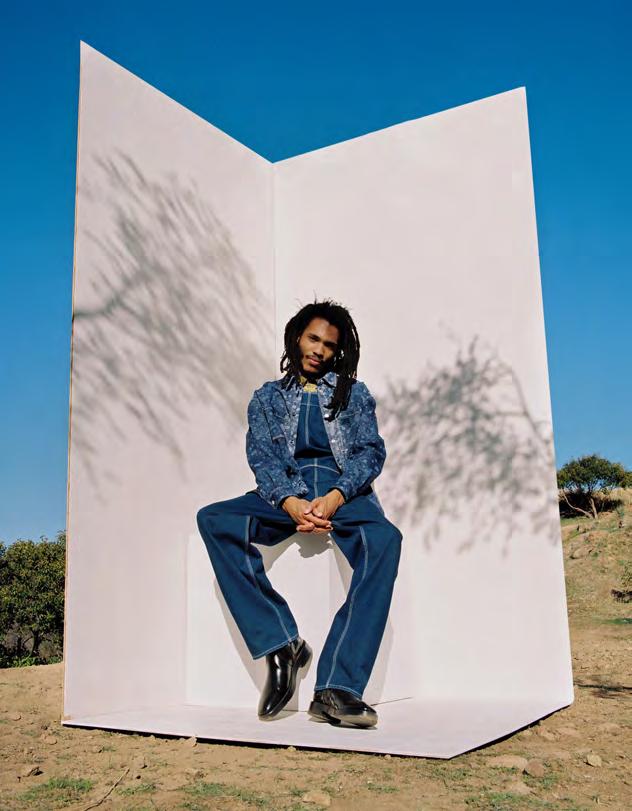

Aidan Cullen, Bryant Giles for Burberry x Nordstrom

Aidan Cullen, Bryant Giles for Burberry x Nordstrom

Aidan Cullen, Amalie for Burberry x Nordstrom

Aidan Cullen, Amalie for Burberry x Nordstrom

Could have happened, man. I was very serious about it, but then it all got blurred with me being injured, and trying to play for years. In middle school, sports were my life—that’s all I cared about honestly. I’m glad... I’m not glad I got sick, but I’m glad I changed lifestyles. Sports don’t last forever and even if I got a scholarship in college, it’s so hard to go pro.

But I always think having sports kind of gives you that discipline. I feel like there’s something inside someone, a drive, this competitive desire to throw that ball 90 miles an hour, or hit a home run and now being in the creative field it’s a rare quality that services you.

I think sports taught me a lot. It taught me about hard work, collab oration, and perseverance. It shows you that you can push your limits and still be okay. It’s funny to feel that. I notice a lot of times when people in my world haven’t played sports. I’m hyper competitive which has helped me but I also think I’ve gotten better at dealing with it in the last few years.

[laughing] You’ve gotten better about it?

I think artists are competitive. It might not make a ton of sense, but it’s competitive. There’s technically room for everyone to make art and

get jobs there’s so much going on. I’m always trying to stop comparing myself to people which is super hard.

That’s human.

Trying to be happy with my own pace, but it’s definitely hard.

Where do you think that comes through the most?

It’s hard to define it. Some of the people I look up to the most put out one or two things a year, and they are dope, and some people do a ton of shit every month. It’s so different for every person. Lately, I’ve just been wanting to have a steady amount of projects and be happy with the outcome of all them as a collective. I try not to get too wrapped up in the competitiveness of it, but everyone has Instagram and Twitter. How many likes are you getting? How many followers are you getting? Which is super weird, because it’s almost impossible to put out great art every week but it makes people think that that’s a norm. It’s definitely weighed on me and for a lot of artists that can get depressing.

Do you have any mentors who shaped you?

I would say one of my high school teachers, more so than any college professor I was able to connect with. She definitely changed my life.

She was like, “You should pur sue this, don’t go to college. Just do photography.” Because I just was shooting every day with my friends. I didn’t know what was gonna happen. Shout out Hannah Northerner.

All the photos in our magazine are shot on film. Throughout your life and career what has been your feeling or relationship with the medium of film?

I love it. Personally, it’s a big part of my style, the colors and the texture. I hate coming home from a shoot where you shoot digitally and you have 4000 photos. With film you might have a few 100 shots or less. You think more, it requires more intention. The process too: getting it developed, it’s super exciting when you get it back. With video, I don’t feel as strongly but if I have the option to shoot it on film, I will choose film everytime. I’ve only shot three videos on 16mm and 35mm, but it’s a different world entirely—it’s way cooler. The color, the tex ture, just the feeling is a different world.

We went to high school with Wallice. It had been over four years since graduation and to our delight, she was just as friendly and kind as ever. Wallice is less than 8 months into releasing her first song and is well on her way to finding her sound. We could feel the energy of her talents mounting as we paddled around Echo Park Reservoir. Through it all Wallice was humble and happy that she can spend her days making music with her friends—the moments of laughing on the reservoir will be ours to keep, but inside these pages are the light that shines through.

“23” we both wrote. I wrote them with David in two days total and most of it was on the first day. I think that for some reason when songs are written quickly, but not in a rushed way, it feels very genuine and people can relate to them a lot. When it’s not overworked. When we overthink it, it’s not as genuine. I feel that you’re not rushing anything. It seems you’re being really poignant about releasing things that mean something to you. That’s another thing that people have really kind of liked because each song is so carefully thought out. If you’re signed from a young age it’s less intentional. I made music before these last two songs, but it wasn’t really representative of what I wanted. This new direction is more indie rock, which I’ve always liked to listen to more. Growing up what were some of the bands that you really liked? My first favorite bands were Weezer and Radio head.

What do you create?

I would say music and ceramics. When did the music start?

I put some really bad quality GarageBand recordings on SoundCloud when I was 15, they’re still out there. My friend from middle school, David, messaged me after hearing one of my terrible demos saying “I want to try producing, would you want to work together?” I was like, “Okay?” He helped me make a song, it was my first professional sounding song, even though he didn’t really know what he was doing either. That was when I was 17, and I’ve worked with David since. The two songs I have out now I made with him. How do you usually work on songs?

I get really attached to what I originally write for a song. It’s hard for me to change things up or move lyrics. I’ve tried to move certain things — from other songs that I didn’t like — to make new songs. But it just doesn’t work, there’s something about when it comes out organically. “Punching Bag” and

“Then

David

and

I were working on something and both agreed that it didn’t seem right. We decided to just go play catch at the Mormon church and revisit it later.”

mean girls there that never left high school. Is there an album on the way? I went to Utah at the beginning of the month, and we finished an EP, that’ll come out in May, which will have three new songs. What was that experience like? The first two days David and I were trying to write things but I was pressuring myself too much. Really pushing that we needed to get the good stuff out. Then David and I were working on something and both agreed that it didn’t seem right. We decided to just go play catch at the Mormon church and revisit it later. We came back and ended up writing the two other songs in the following three or four days. I’m really happy with those. How do you compare the themes for “Punching Bag,” “23,” and “Hey Michael?” Do you feel there’s a thread through them all? Or do you feel that they’re each touching on dif ferent aspects of yourself? They’re all different aspects of me. It’s funny, because “Hey Michael” is about really bad guys and boyfriends, even though I’ve had one really amazing boyfriend for 6 years. I guess it’s almost like an alter ego sometimes — if I haven’t directly experienced that — or something comparable. What I really liked for “Punching Bag” and “23” is that people describe them as really witty or sarcastic, which is fun. When I sent “Hey Michael” off to get mastered, the guy who masters my stuff said the first time he

listened to it he was just laughing at the lyrics. It’s funny because usually, you don’t want people to laugh at your lyrics, but something about it makes people smile. How do you feel about other people’s successes, and do you com pare yourself with others?

Definitely in this last year Marinelli — who I work with — has had such amazing success. It’s really easy to be jealous of somebody. But that’s not gonna help anyone, I’m genuinely really happy for them obviously. I mean, that’s kind of where “23” stemmed from, scared that I’ll still be a loser. There’s a lot of new music that is coming out by 23 to 25-year-olds, especially after this last year, which was really bad for people. But I think a lot of musicians were able to find their audiences being at home. Maybe it’s because there’s not so much competition, all these well-known artists aren’t having any real shows. So the playing field is more level.

Absolutely, during lockdown everyone had to slow down, so they were able to discover new music.

They have more time now, or they did, which I think is why I got a lot of plays and finds. I’m not sure if that would have happened otherwise, and I can’t say I would have created what I’ve created if it wasn’t for that time. How has the reaction been over the past year?

Every time I have a new release part of me fears the reaction. “Punching Bag” had such a crazy response. So for “23” I was like, What if no one wants to listen to this. What if “Punching Bag” was just the only good song. But “23” got a lot of smaller and bigger blog press like, Pigeons & Planes and NPR, which is crazy. It was also on The Fader, which has always been a goal of mine. Any physical copies going into the world?

I want to do a tiny run of vinyls, it wouldn’t be for-profit, just something to exist in the world. I really want to design some merch for the future as well. I’ve always thought band merch is important and I’m very judgemental of other people’s merch. I think I can do better than cheesy fonts and peoples faces. What is next for you, music-wise, what do you hope for, any live shows lined up? Hopefully, live shows are coming back in October when things are safer. I like the idea of opening for a cool band. That’d be the first step anyway, maybe play a festival? [Laughing]

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in Topanga, which I think is a really cool part of my upbringing. I just did a photoshoot up there and the photographer asked where I was from, and I got to say, “Right here.” Some day I’d like to buy a house there, it’s so much more expensive now than when I was growing up. I remember it being really hippie. I used to go to Topanga Days, which is a beautiful memory. I would go and

What is the dream team if you were to perform a show tomorrow?

I want to sing and play guitar, my boyfriend Cal would also play guitar. Caleb would play bass, I’ve known him since I was 14. David on the drums, but he’s gonna be way too busy for little ol’ me. So I’m still probably going to have to find a drummer. I saw a playlist on Spotify called “Lorem” that you were part of, what is that? Lorem is interesting, it’s a Spotify playlist, rather than just a complication of new indie or bedroom pop, it has more of a community aspect to it. It’s a lot of my friends that are part of it and we all work together. Marinelli was the cover this month, since he produces for me, I got on it. It gets a lot of listens every day because it’s very curated. When it comes to my song I immediately skip through, I don’t want people to see that I’m listening to my own song! One time my old roommate took a screenshot and said, “Why do you listen to your music?” I was literally showing my grandma. [laughing]

it would be this big celebration, I remember getting my face painted and playing in the creek. Not on my phone, kids these days with their iPads. [laughing] Do you have any genres you want to explore next?

I really love indie-folk. I made some songs a long time ago that were in that style. I always love listening to indie-folk, like Faye Webster and Julia Jacklin. They’re so good. Are there musicians that create the type of music you’d want to make or explore someday?

In the most ideal world, how would you want people to find your music? I think a festival is the best way to discover music. Playing a festival, where I’m at the bottom of the poster, would be really cool. Playing in front of strangers who’ve never heard my music, hearing it for the first time in the most genuine way. That’s the purest way to find music.

I mean, Phoebe Bridgers is so cliché to say now, but she is a really cool rock musician, same with Adrianne Lenker. I like to play guitar when I perform, not that there have been many performances. Because I’m a musician, playing an instrument, rather than just a singer, is really important to me. That’s why I studied jazz in college, even if it was for just a year. I want to be respected by other musicians. It’s hard, being a girl in music, there are not that many female pro ducers, mostly singers. Even within that, it’s still hard to get noticed but this doesn’t hinder me much. It’s wild to see this disparity exists on all levels, Phoebe Bridgers playing SNL and smashing her guitar was met with, “I don’t know, I just don’t see why she had to do that?” Even though every other rock star did that in the 70s. Regardless it is still exciting to see where it’s going.

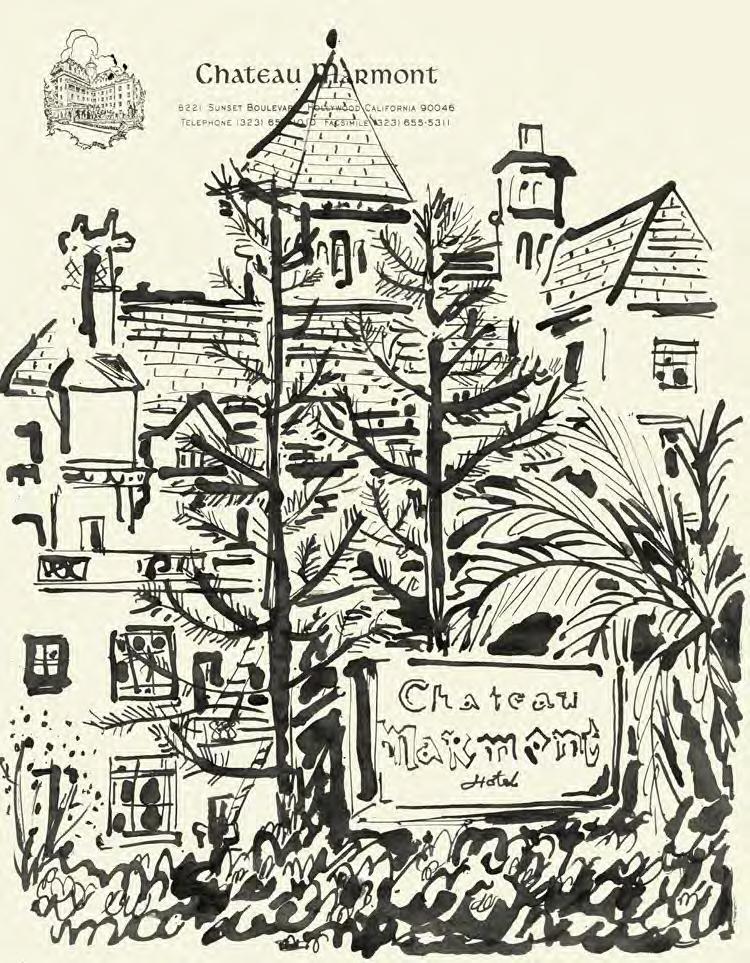

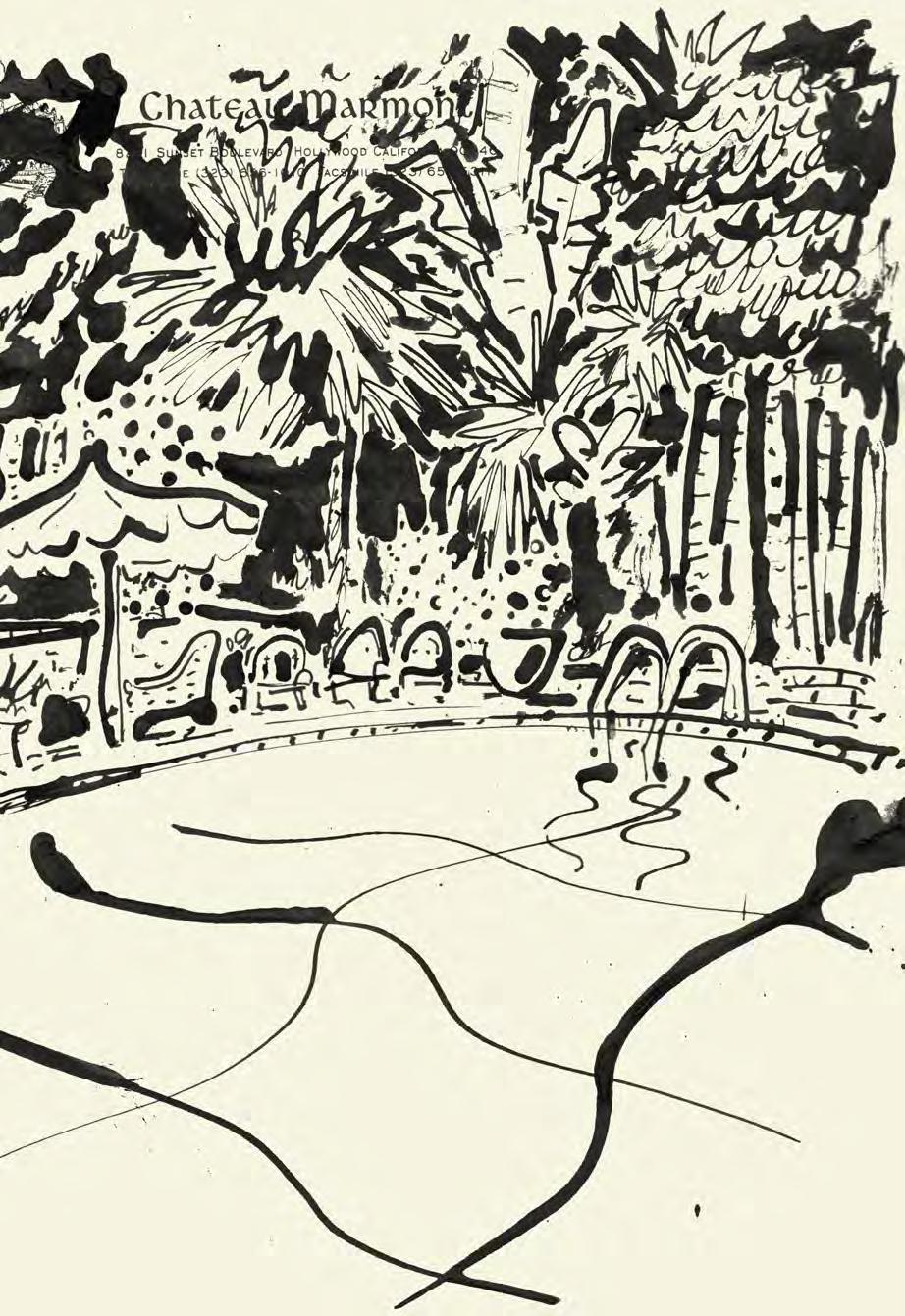

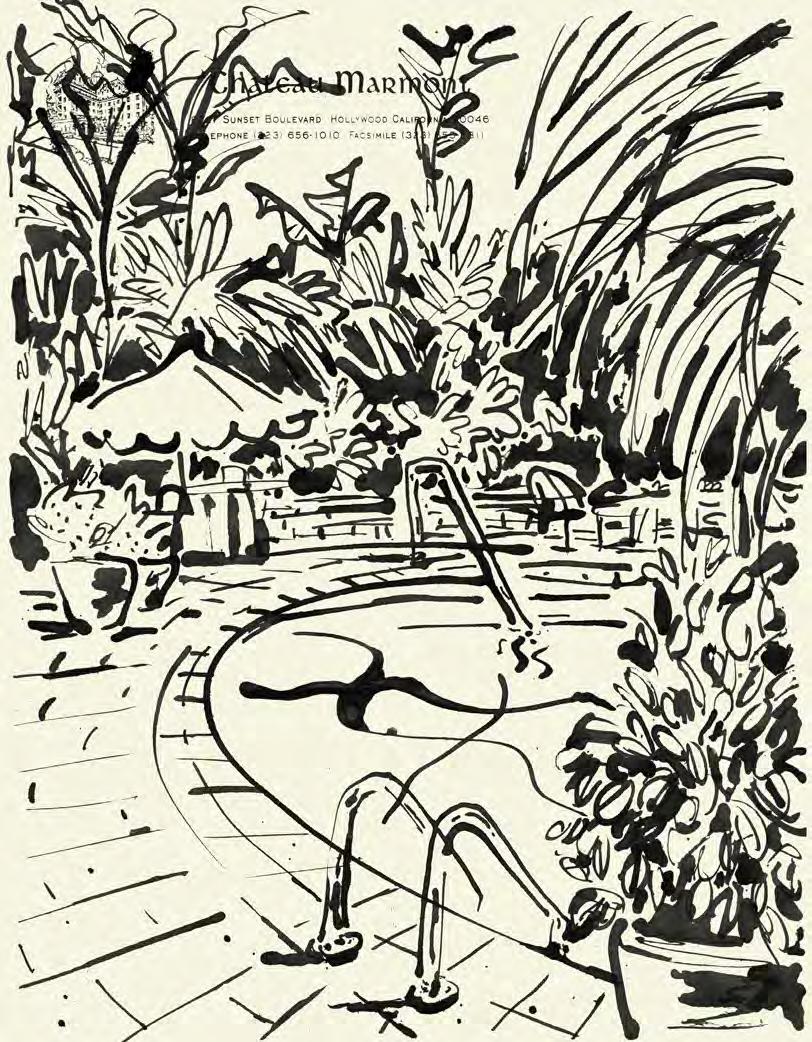

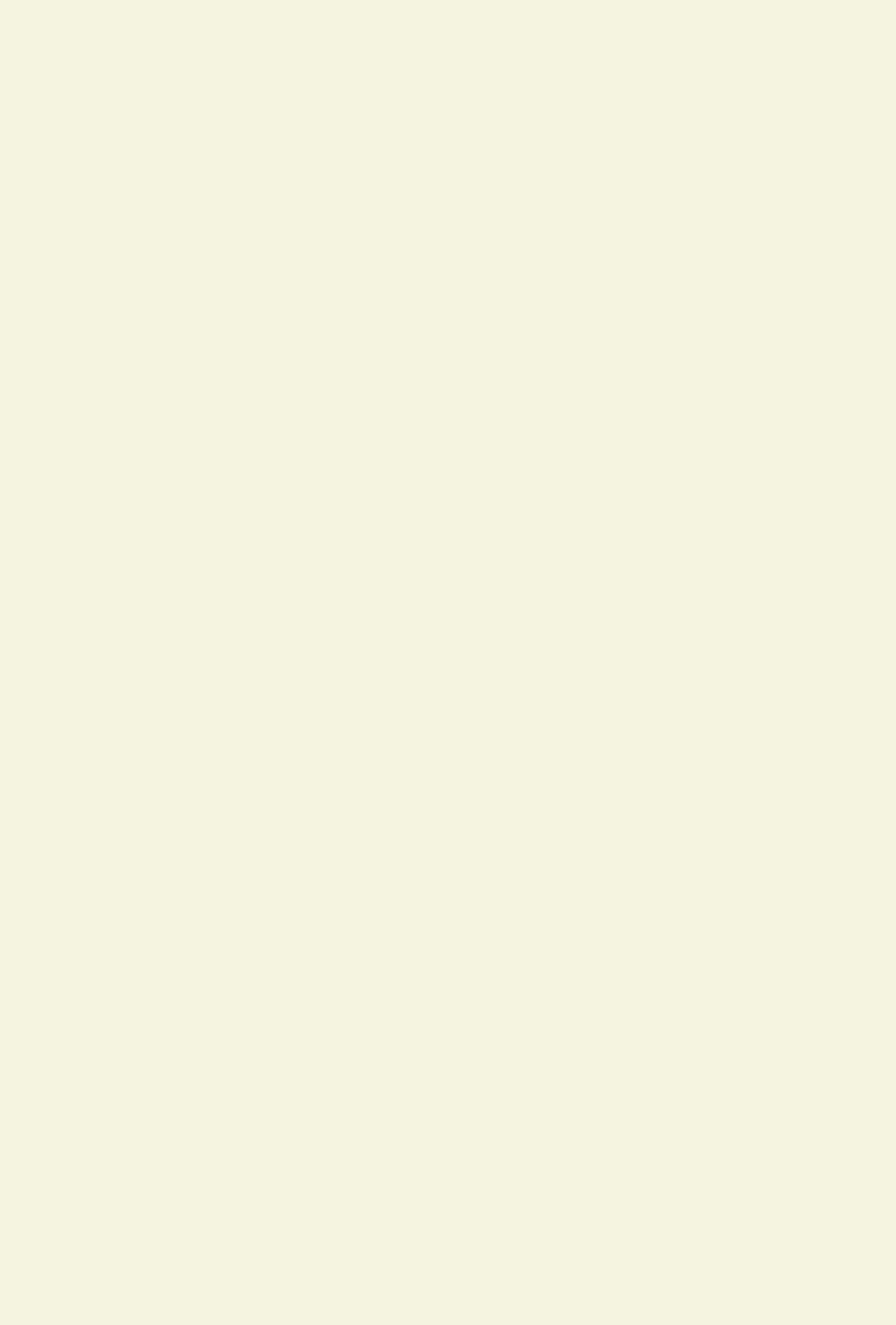

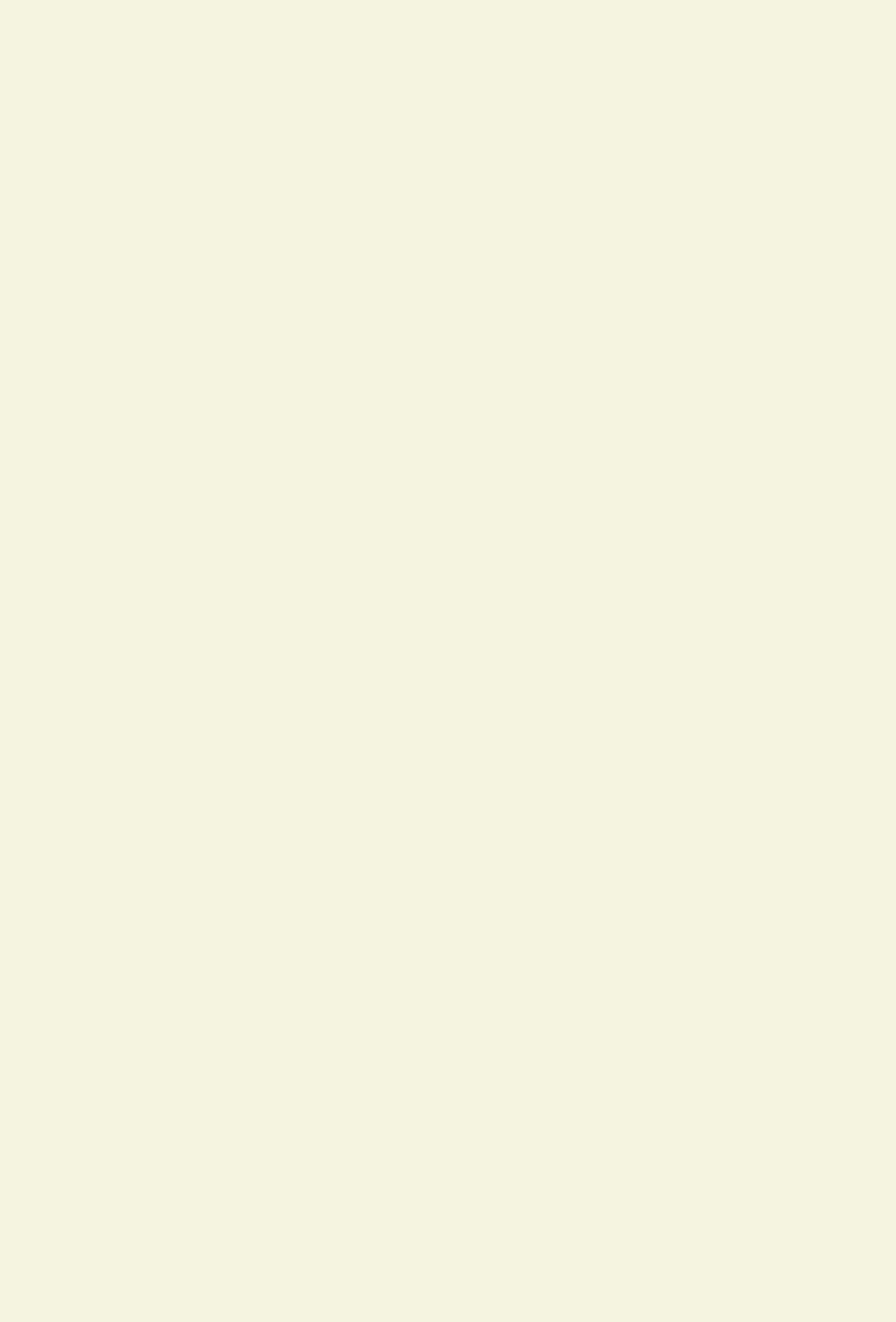

Jimmy Thompson is as Californian as they come. He came in to do the interview with dark glasses and a casual smile. He often finds himself sitting poolside at Chateau Marmont, drawing a timeless world, a Los Angeles before they cut the hedges and the mystery disappeared. Jimmy’s work pays homage to the great nineteenth-century im pressionists. His drawings of cafés and roof tops remind us of a young Derain or Ma tisse. He has the ability to capture someone’s essence in a few quick strokes, some may say this style reeks of confidence, but we think it is instead a tenant of Jimmy’s authenticity.

How did you initially find drawing?

I always got encouragement from a really young age. I was good at drawing, but I guess after high school I felt more strongly about it. I wasn’t good at math or any of those other things, and so I thought, This is the hand I have to play with.

Looking at your drawings of people, it’s almost like you don’t fuss with it, you just lay ink down and depict somebody’s face in a way that’s not overdone.

I’m glad you said that, because I’ve been accused of sometimes being too simple. But I think that’s my goal, if you can distill something to its essence, then you move on. I did all that rendering stuff when I was in high school AP courses. If you can capture a simple gesture, the way your arm just hit, or similar little key moments, then you have it. You don’t have to draw every button.

I love the drawings that you do while out in the world, as casually as while eating lunch somewhere, drawing on the side of a paper menu. There’s a feeling that you may lose it, it may get crumpled up and tossed, but it exists in the moment.

It shows mastery. If you look at what Matisse was drawing towards the end of his life, he could get the arch of a woman’s back in just one line.

It reeks of confidence, he got to a place where he didn’t have to explain why he did that. The viewer looks at the drawing and goes, “Oh, she was standing like this?” It makes you think more.

I was having lunch in New York at a place called Balthazar, and I was drawing the staff and the people around me. I could tell that a couple of people who worked there were kind of intrigued, I decided I’m just gonna leave it. Then I get a message on Instagram a week later saying, “Hey, you don’t know me but my dad works at Balthazar and he took that drawing you did and he is just so proud and tickled that you depict ed him in his workplace.” That just made me feel so good because now it has a life of its own. That being said, other times a waiter will just toss it. Other times I’ll pull over while driv ing, even if I had something to do or someone to see, I’ll just get obsessed about capturing a moment I see. I pick up little things on the street, whether it be a note, someone’s grocery list, or just anything. I love cap turing and making art of little things that maybe I’m not meant to see, or that most people may step over.

It refutes art being this upper echelon thing that only wealthy people can reach. Instead, it’s the inverse. This man was so touched by you drawing him on a napkin. I think it also shows that it’s within you, “you can take away my paper and pens and I can still make what I want to make. I could do it again.” I think that’s a beautiful quali ty, who taught you that?

My mentor was pretty incredible. He illustrated The Catcher in the Rye cover, his best friend was J.D. Salinger. He was one of the only people that J.D. talked to for the rest of his life. He was in his 80’s still teaching, that was inspiring to me, peo ple who are still doing it, sharing information. He talked about making things feel cinematic. Letting the viewer’s eye create motion within a still image where you can look around. Purpose ful, thoughtful, spontaneous decisions.

There is something amazing about teachers who bring so much to the table, sharing what they know in unconventional ways. Some students really have a hard time with not having a straightforward assignment where you check things off.

Yeah, not to get too pretentious, but another analogy would be with mu sic, there are some students that can read the music and play everything perfectly. That’s incredible, but then you get other types of musicians, I guess jazz is the best example, where musicians just let go and it’s the human quality that comes out. The music lives in the imperfections. I like drawings where you can feel and see someone thinking. There are certain artists whose thought processes bleed into their work, where some lines went thick to thin.

I did a bunch of drawings in Morocco. I did some pastel ones I was getting into, really simple colors, red, blue, yellow. I’ve gone back and started to revisit some Morrocan themes in my newer pieces. The pottery and the rug patterns are especially vibrant. Looking at everyday things from the outside, you would never notice how saturated things can be until you start drawing them. It’s so crazy because you go to beautiful places and then want to go back, but there are so many new places to go.

I love the lore of old Hollywood, so the Chateau Marmont is this one-stop shop of rich Los Angeles history. It has so many old stories attached to it, and the building itself is really cool. I know it has the party factor but it’s this little oasis off Sunset. There was this place called “The Garden of Allah,” it closed I think in the 60s, but it was across the street from the Chateau. It was a complex of villas that F. Scott Fitzgerald lived in. These ideas of people trying to make little secluded private, beautiful spots in an otherwise bustling city is interesting to me.

I went to the Chateau once with a friend who was staying there and he gave me some letterhead, going back to using what you have, so I just started drawing on it. I like that it’s on the letterhead, the quietness, the privateness of the Chateau.

The drawings really feel timeless, like they could be from any period.

I always look for things that have that classical appeal. You feel like you could be a part of that generation, things that aren’t so today but it’s still a little murky. The Paris ones for example, Notre Dame, is something that anyone could have drawn in the 18th century.

How about other mediums? Have you ever thought about painting?

Yeah, I had another mentor who said something that always stuck with me: “Draw like you paint and paint like you draw.” I used to be intimidated by painting. All the mixing, the materials, and ev erything. But when he started talking about it that way, it’s really just a drawing with paints. Pushing paint around creates those movements. Like Van Gough, I mean I got to go to the facility where he was living in the south of France. You know that famous piece, the bedroom one, it’s this ubiquitous painting you see in the art world. To actually go into that place and see it in person, you can really imagine his state of mind. Just like living that quiet life, sinking yourself into your craft.

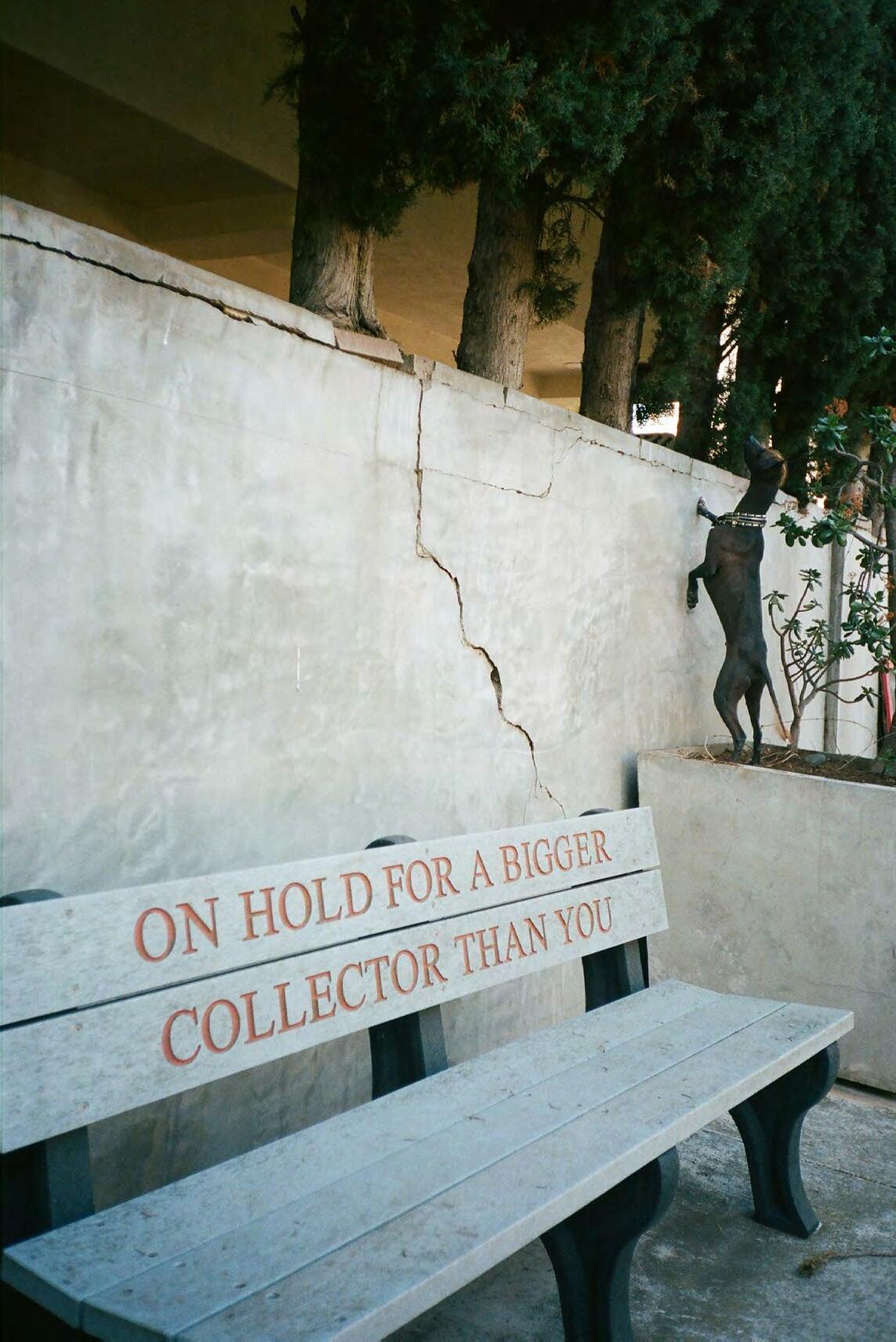

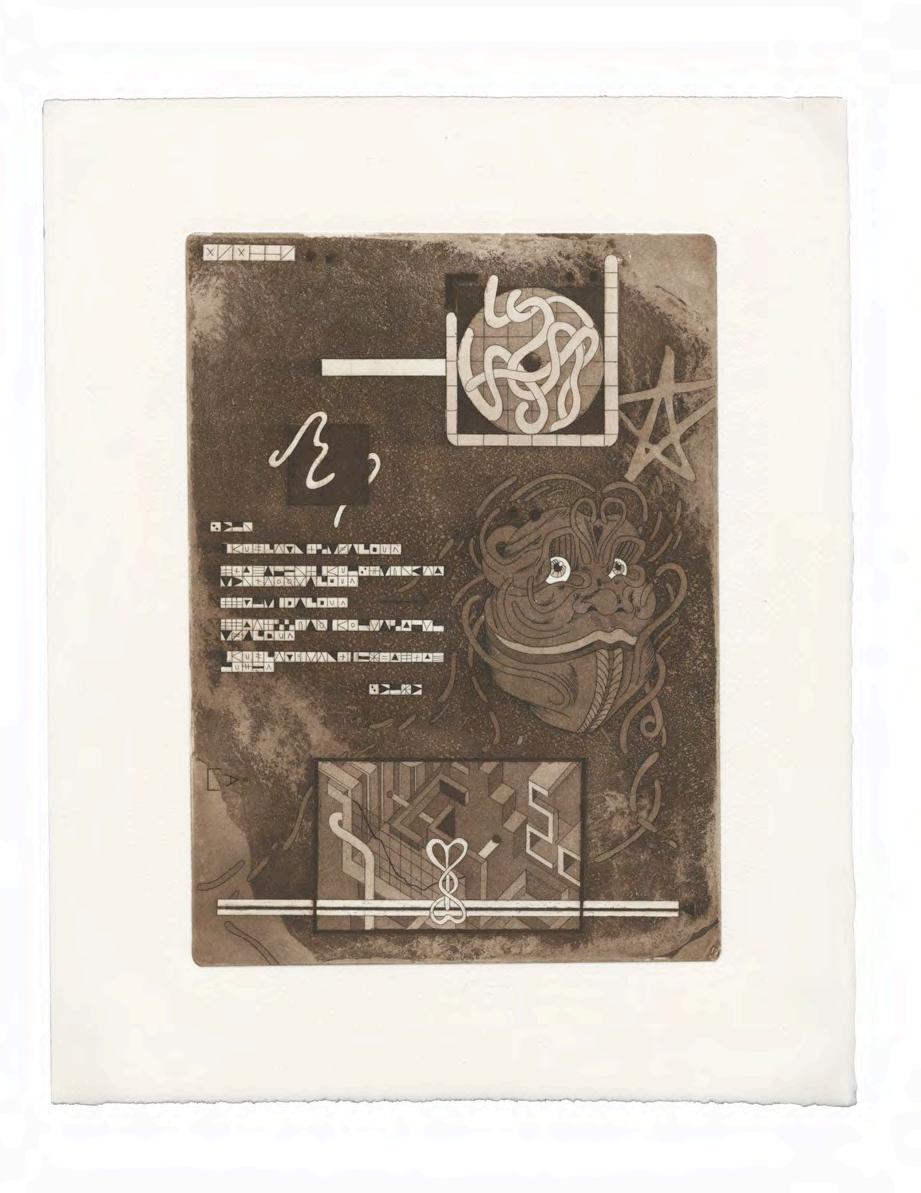

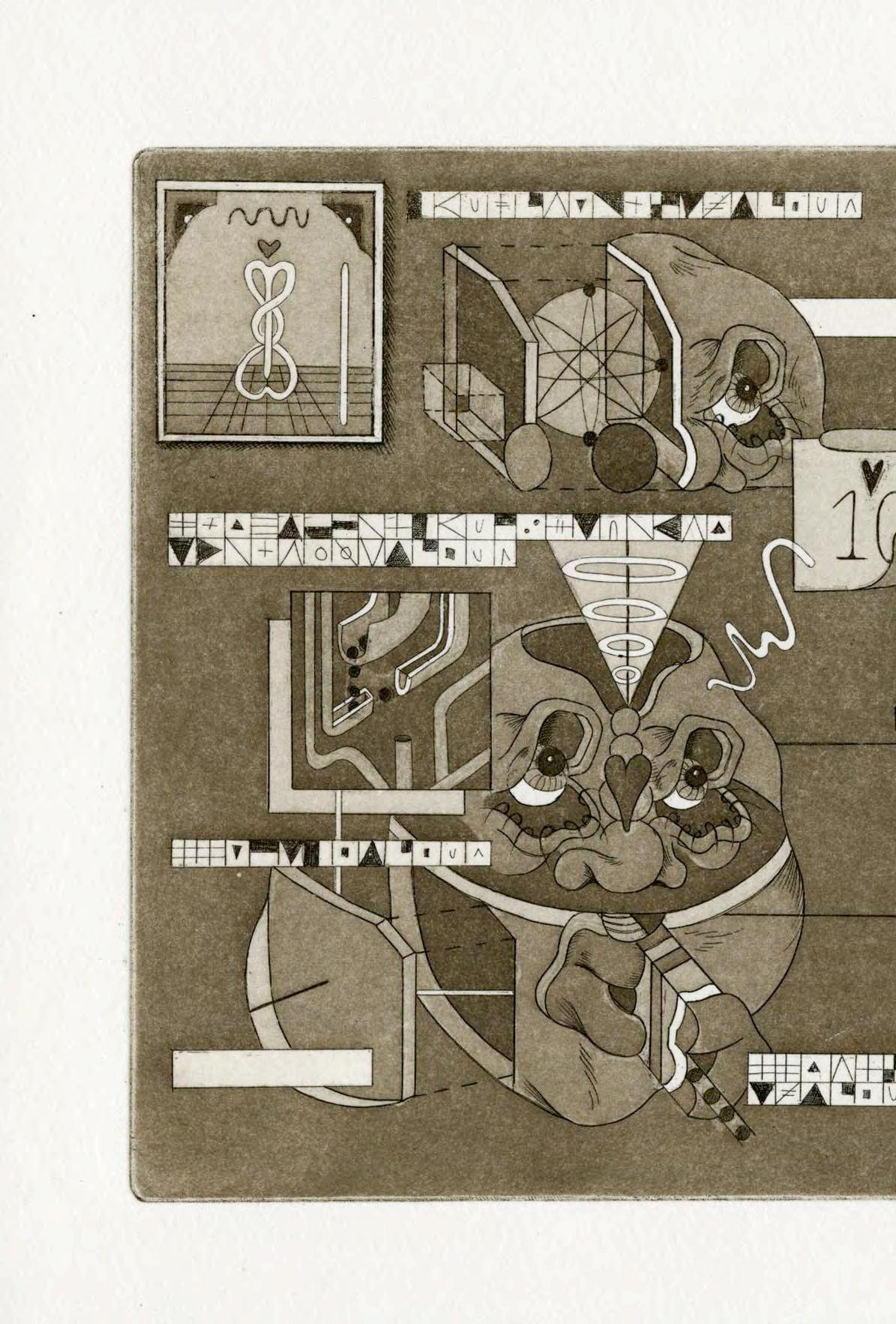

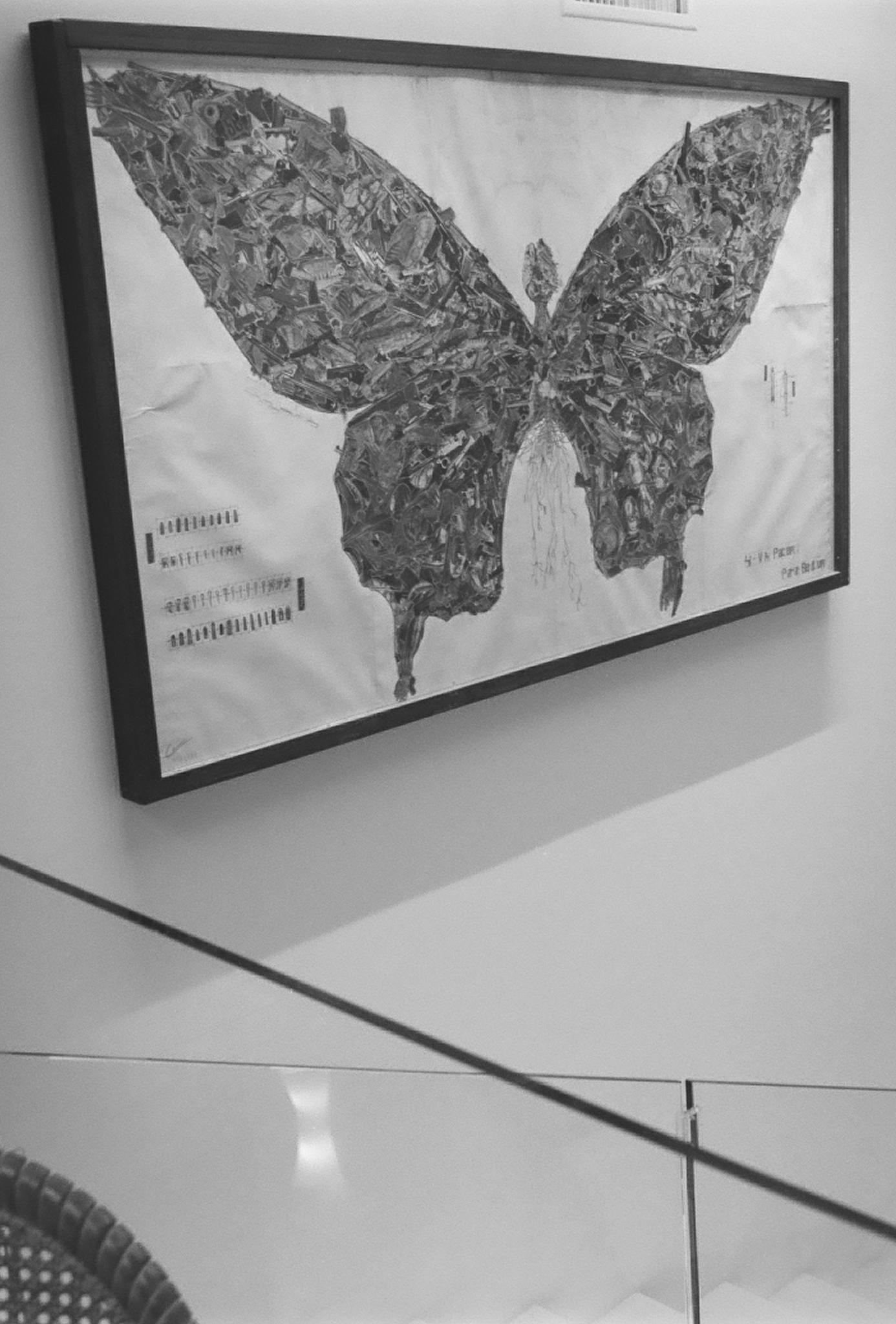

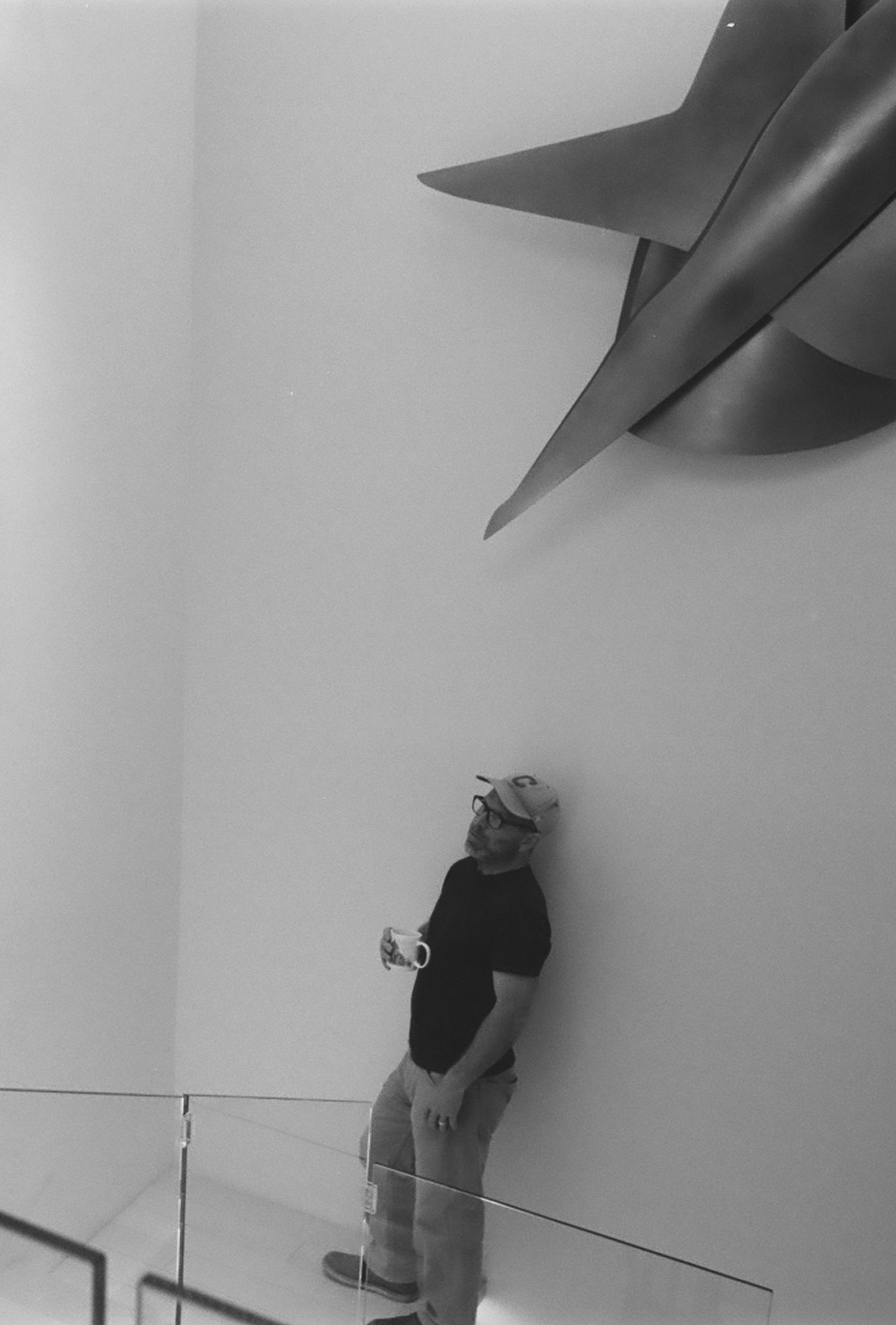

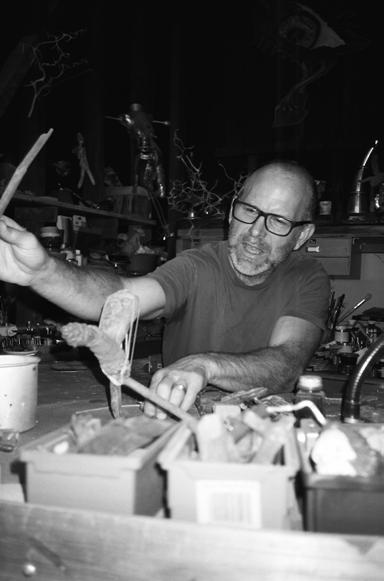

We met Danny First through a long line of random coincidences. We have never fully understood the origins of Danny but always knew he had an incredible sense of taste and light. Maybe you’ve seen his benches scattered around Los Angeles or his STUDIO ARTIST RESIDENCY tucked away behind stores on La Brea. Danny incubates all artists. From the classically trained master to the barista who draws. He has the incredible gift of seeing something for what it is even if it’s a few seeds taking root, or a bartender mixing paint. He sat with us in his garden holding his hairless dog Diego. Together they told us that life was never, and will never be, about prestige but instead recognizing beauty when it cross es your path. You’ll never know when or why it does, but all you can hope to do is be open enough to see it.

We initially ask artists what it is that they create, but thinking about this interview, we’re more curious about how you came to art? Growing up and into adulthood, what made you realize you wanted to be part of it and create yourself?

I grew up with a lot of art in the house. My father was a hoarder of antiquities, not my style of art, but I didn’t know anything better. It was nice to live with all that stuff. I re member going to museums from very early on, we used to go to Europe, those days, you could actually go to a museum and get in without waiting in line for five hours. So it was much easier. I was always into it, but when

I came to Los Angeles — I came from Israel — I had no clue what I wanted to do. I knew that I was pretty okay at drawings. So, I came up with this drawing, and I thought it might be cool for a T-shirt. But I didn’t know anything about any thing. Those days, I probably wore some T-shirts, but I just didn’t think anything of them. I happened to meet someone who told me that he was a screen-printer. I told him about my idea. He said, “If you give me 300 bucks, I’ll print 100 shirts with your design.” So all I had was his phone number, he could have just disappeared with my money, but he showed up one day with

a box of T-shirts. I thought, I’m gonna make it big, which was ridiculous, you know, but I did, I just put a few in my backpack and started walking around town, showing it to stores and leaving them in different stores on consign ment, they wouldn’t even pay me right away for them. But from there I made more designs, always these stick figures that I used to make. I was always into art collection, but I never had the money to buy anything so I would go to art fairs; Chicago Art Fair, New York, Europe all this before Miami Art Fair, but just to look. The thought of getting anything didn’t even cross my mind because there’s no way I could afford it. Anyway, the busi

ness started to get better and I started making some more money, so then I started buying art. Today I cringe when I think about the shit that I bought, but that’s the way it goes. It’s like the clothes that you wore early on, there are certain styles that you look back and think, How could I wear this shirt?

What was that transition from you walking around with a backpack full of T-shirts to the beginning of your art collection and curation?

My first break was when a friend of mine told me about this song, “Don’t worry, be happy.” I used to go to this store in Westwood by UCLA, they had all these T-shirt stores all

around. Every time I would go there to bring them some shirts. I would ask the manager, “Rick, what is the best-selling shirt?” And he told me “Don’t worry, be hap py” I thought, Oh, my friend told me about this. So I’m thinking, What can I do with “Don’t worry, be happy.” And then I realized I have this smiley face on my desk, I didn’t know what to do with it. So I put, “Don’t worry, be happy” with the smiley face in the middle. I went to my printer, printed about 200 of them or something, and gave them to a bunch of stores and I went to Europe on a trip. I then came home to calls like crazy. All these stores were asking how they could get more of my shirts... so I sold a shitload of them.

Was that around the same time you started making more of your own work?

I always had a dream to start mak ing my own pieces. I had a period where I painted... At least when I have a delusional moment, I can kick myself and just get out of it. Lucky for me painting was one of those moments, it didn’t last long. For a while, I had this dream of making sculptures. So I started with making ceramic vessels. And then one day I started making heads, the heads I’m pretty happy

with...I got fed up with the t-shirts, and I had a massive inventory of T-shirts. I got rid of 99% of it. I gave so much of it to charities.

Just gave it all away?

Yeah, I mean, one time I gave to this orphanage, the last time I brought them the shirts, they yelled at me, “Why do you bring us so much stuff!” So I decided to clear up the warehouse in the valley, and I re duced it to the one on La Brea, then I decided I’m going to turn it into my studio. So I cleared it up, and then I looked at the space. And I thought, This is nuts, what do I need this space for? So I had this idea to invite artists to live and work there.

When did you first consider showcas ing art?

Well, for the longest time, before the residency or The Cabin, I would always have people from everywhere come over to my house. Many times I would ask my friends who make art, “Why don’t you bring a piece? So I can hang it in the house.” People seeing art is something that I always love. At the same time, I built The Cabin. I just loved the simplicity of The Cabin. And I thought that it would showcase art really well.

Was there a reason specifically that you chose to build it as the dimensions of Ted Kaczynski, “The Unabomber’s” cabin?

No, when I saw it the first time I thought, Oh, this is such a cool struc ture. So simple. It’s almost like what a kid’s drawing of a house would look like. But I didn’t expect it to look so good inside. It photographs so well, and the lighting is perfect. It’s un pretentious, it can hold really large pieces, the connection between The Cabin and the residency didn’t start right away. Now the artists who come to the studio show at the Cabin.

When did the first artist residency start?

2014 or 2015? The first time, it didn’t go well. The guy would wake up at two or three in the afternoon, but you have to start somewhere. He ended up being very successful. He did very, very well for a short time, he had his 15 minutes. But then I realized I’m really good at mentoring artists because I’m very practical. I’ve been around and looking at art for so long.

How do you explain those 15 minutes of fame, the inflation of art, prices skyrocketing, and its effect on young artists?

With your expertise in mentoring artists, what qualities make a good artist?

The first thing that comes to mind is originality. You don’t have to be a great painter to see a painting has great energy, which I really love. But I’m always surprising myself with the things that I like, for instance, I was never into airbrush work. Now the current works in The Cabin are a combination of airbrush and painting. So I just never know what will speak to me.

How do you choose which artists to have in the residency?

Well, I always like to mix it up, the next artist in the studio does total abstract work, geometric style. So not my thing, but I love them. I like to mix the style of art that I’ve nev er had before. When you come to the residency you have one month to produce a few works. So if I see artists who do very detailed work that will take you a month to finish a little painting. That’s not gonna work.

You hear all these numbers, every thing is going so crazy. For me, it’s not as exciting anymore, at such prices it becomes a problem... not necessarily a big problem, but no body knows how long it’s gonna last. So everybody tries to milk it as long as they can.

Thinking about style 20 years ago, the art you bought then and hate now, or currently the talk about NFTs, how do you discern what will truly have a lasting impression or be out of style in nine months, what guides you?

I always look and ask, “Would I want this art on my walls?” That’s it. If the answer is “Yes, I want this art on my wall,” then I go for it. Usually, galleries, they always want to see a nice resume, MFA, blah, blah, all this... The less you have the more I’m interested. If some collectors ask me, “Can you send me his resume?” I respond, “What resume? I’ll give you his name. Never had a show, selftaught, never showed anywhere, and never sold anything. That’s it? You want it? Then get it. You don’t want it. That’s perfectly fine.” I had an artist here last year that had nothing on his resume. He worked at a bar in the Lower East Side, super sweet guy, and talented. Another artist last year, I looked at his works and saw some thing in it, there was so much stuff in it, I took a screenshot of the painting, I zoomed in, and I cropped little pieces from the painting. I told him, “You come here and you blow this up. You paint this part on large can vases and not go too crazy,” now he’s back in New York, he’s gonna have a solo show in a gallery. I mean we sold every piece that he made here. It was incredible. He came here on March 1st last year, because of the pandem ic, he couldn’t go anywhere, so he stayed for four months. He made tons of work. Everything sold, he is going to be doing very well. And he really appreciates it, you know some don’t.

How has it been watching artists that you have had in the residency grow? How are your relationships with each artist?

Quite a few of them I keep in touch with, you know, it’s really nice to see how well they are doing. But some... you don’t hear back and that’s it. Their career just takes off, goes nuts, and then that was it, which is fine. But I keep in touch with quite a few.

Do you always save a piece from each one?

Yeah, I buy some also, I learned my lesson. For a while, I used to chase galleries to come to the studio to see the works, and then they would pick up the artist and then they would forget about me. I would try to get some works from that artist but then... “Sorry. Nothing is available.” Some of the artists listen, some of them don’t. Some of them call me every time they get approached by a gallery. They like to hear what I have to say because I know a lot of these galleries and some of them don’t.

Part of Chuck is that curatori al aspect. Finding artists we are interested in and speaking to them about why they create, it’s great to find these human connections. Have there been stand-out relationships with artists?

Yes, it’s really nice to have those, I had another artist last year, Caleb Hahne, he did these hands holding a glass of water. I’d never met him before, he lives in Denver. I had this whole idea for a show. He did a few paintings with this yellow, orange color that looked like a Los Angeles sunset during the fires this past fall. I said to him, “Listen we’re having these fires, the sky is all red and orange. The timing is perfect. You come from Colorado. We get our water from Colorado.” He had made this little painting of a hand holding water, and I told him to make it huge. It’s not that everything bigger is better. It’s just because it gives a whole different meaning to the painting. It was a struggle, but then he did it. And it looked

pretty great, he still had a job when he came here to LA. When he got back, he quit. Now he’s just working like crazy.

What do you think the future is for your residency and the Cabin?

Future... I just want to keep going as it is, I get so excited when I discover someone new, and especially love the idea of finding someone that nobody wanted to show before. I mean, it’s just like an artist told me once when he came here. He was in such a strange time when I called him. Nothing was really selling and he wasn’t sure if he wanted to keep going. Not that many people can keep painting like Van Gogh did when nothing is selling. You need validation, by people actu ally spending money and buying your work, or people enjoying your work. He didn’t get it from anyone really, so when he came here it was a new life. I have this one artist from Belgium that was here. And when he went back to Belgium he got a tattoo of the Cabin on his leg. No way that’s awesome.

There’s Vojtech Kovarik, he’s a Czech Republic artist. When he came here, it was almost like Borat in LA [laughing].

The guy lives in a little town, 400 kilometers from Prague. I paid for his airfare, and when he came here, he was supposed to come at around noon. And at six I was sitting in a restaurant and waiting for him across the street from the studio. I didn’t have his telephone number. Then I look on Instagram Live and I see him walking on The Hollywood Walk of Fame. Because he just couldn’t wait to go, he took the bus, which prob ably took him three hours to get to Hollywood from the airport. This guy is one of the hottest European artists right now. I told him “You’re gonna be the richest person in your little village.” He probably is...

We’ve known Arrow since high school. Seeing her again for this interview reminded us that she’s always been incredibly beautiful and immensely talented. From the moment we sat outside on her patio, it felt as if we could be sitting on the benches of our high school laughing before the first bell. The way she told us about her music and the evolution of her performance was similar to an old friend talking about their new band. While Arrow’s perfor mances in Starcrawler look like a fair depiction of insanity, she has always been one of the sweetest and most down-to-earth people we know. I guess the world has always been filled with mystery and—of course—rock n’ roll.

The first question we usually pose is: what do you create?

The thing I create in my mind, with Starcrawler, is something I’ve always wanted to create: our own world.

Music, yes, but I really want to have a Starcrawler world. The Grateful Dead have deadheads and Jimmy Buffett... Parrot heads.

I don’t want it to just be some band that was cool for a minute. I want it to be our own scene.

How did it start?

It started because I really wanted to start a band, and at first just to do it for fun. You know, I didn’t really think it was gonna be my career. I was in a band before with people from high school and it just wasn’t moving; nothing was happening and of course, drama... It made me realize how much

I really did want to do it though I hadn’t realized it until that point and I was like, “Fuck, I don’t even care that this isn’t working out with these peo ple because I just want it to happen.”

Absolutely, what was that shift into making Starcrawler?

I found people that seemed all down and all serious. And we weren’t all best friends so we had some sort of reliabil ity on each other. It was almost like starting a business. When I met Henry, I figured he played guitar because he

was in the music academy and he looked cool enough. I gave him my number and we jammed. Austin I had already found—who is no lon ger in the band anymore—but once Henry came into the equation, the three of us really became solid, we could actually now write songs. It all kind of fell into place in a weird way.

So you and Henry are kind of the core of the band?

Yeah, pretty much. When I met Austin, we were still just kind of getting to know each other and figuring out what our sound was because we had different music tastes. So, it was like two different teams jamming. It wasn’t a band yet. Once Henry joined we were able to find the sound and start playing like a band.

Did that first jam with Henry click in a way?

Yeah definitely. He is super straightforward. When we’d play, if he heard something he didn’t like, he’d be like, “Don’t play that.” You know what I mean? My dad taught me drums when I was a kid and he was like that too. I didn’t take it personally. Henry’s a music kid. That’s just how it is. It’s like, if you’re wrong, you’re wrong. It’s not a personal thing. That was the issue in the band before, if you said, “Oh that’s out of tune or that’s wrong,” it became personal.

Thinking about building a world that’s bigger than a high school bed room band, was that something that the band built? Or were you more of the architect?

I definitely sought everyone out and made it happen, but once we start ed practicing, it really made things move. We didn’t want to be a high school band. Sometimes I regret that only because we started out just play ing bars and we never played house parties or The Smell like other bands in our high school. Looking back, bars and bar venues were weirdly easier.

Photo Courtesy of: Cameron McCool

Photo Courtesy of: Cameron McCool

What was your first show like?

The first show was actually not at a venue at all: it was at this space being renovated, a storage room. It was real ly fucking small. Probably the size of my living room. My friends came but since it was so small, it was packed. It was fun, but then after that, we played these weird bars. We slowly realized we couldn’t accept every single offer, it makes it harder, you dig yourself into a hole. There was this one bar called Der Wolf Scar, this German themed bar in Pasadena. They served beer and German sausages. It was so bad, such bad vibes, and no one was there to watch us, just people eating sausages.

That’s hilarious. Yeah, it was really gnarly. I mean crazy bad. I feel bad saying that but bad metal bands that were called Deep Fried Dynamite or George of the Jungle played there. It was tweakers with their shirts off, really ugly. Ugly guitars, I don’t even know how to de scribe it, it was such a gnarly vibe. You’re definitely a performer—the show is a huge part of it and it’s not something you do quietly. How did you cultivate your onstage presence?

There was a while before we were actually playing shows where I kind of had time to think about what I want ed the whole vibe to be, but I didn’t really know until I had already gotten