14 minute read

Carlos Ulloa

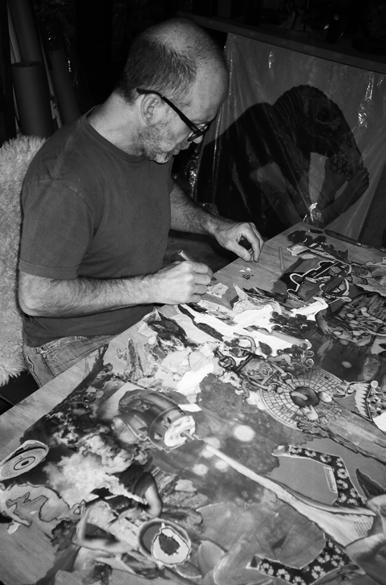

Carlos used to run Yamashiro Restaurant—the Olympus of Hollywood. He was always working on something, lugging Japanese lanterns or found doll heads back and forth from the restaurant to his house. Sitting in his studio, through the smell of glue and sawdust, we realized where this madness comes from, it’s that intense passion one has in trying to figure out the meaning of life. Some drive through it, others saunter, but Carlos chooses to collage himself across it. Talking to Carlos we were reminded that creating has always and will always come from within—it never comes fast enough and oftentimes is over too soon. It was never meant to be forever.

Your work expands so many mediums and concepts. How do you define what you create? What do I do? You know, the intention? Because that’s a loaded word. The intention is obviously connection, right? I want to connect. But it’s a lonesome process too. It’s sort of ironic that my intention is to connect but I don’t have any connection in doing it. So then my connection is when I’m out, the lone wolf process of going to collect my stuff. It’s really an act of collecting and then assembling and collaging my intentions and who I am. When I was younger, a lot of my work was about the message I wanted to give. And a lot of it’s about questions I prefer to ask. The older you get, the more questions you have. Strange. You know, you guys are pretty grounded, but when I was your age, I knew I was the shit. I knew everything. Now I don’t know shit. I know that I found meaning in collecting other people’s waste or nature’s waste and trying to make a powerful query out of it. A statement, I guess you could say. But I’m never quite sure what it is I’m doing because if I really look into it, there are so many what-ifs? Or whys? It’s a broad question, but I would say the intention is always to be able to work wherever I am, whenever I can, and the easiest way I’ve found in this scale is to work with things I find because it’s a never-ending sort of “Wow. That’s a cool shape. That’s something that I can manipulate— that’s something that can manipulate me.” I love the idea that finding and assembling things leads to greater understanding—has this way of thinking grown over time or is it one that you’ve always had? It was just a learned way of dealing with life because we moved a lot when I was young. It was unbalancing, man. I think about Henrietta [Carlos’ daughter] moving at seven; I’d already moved six times or something like that. I always think I was just collaging myself into situations. Every situation was new. It makes sense that I do collage, especially the scale; the scale of things is all stuff that I could fucking get in a trunk. Things I knew were going to end up on the other side wherever we moved. I was very nomadic for a long time—everything was mobile. I remember getting to Madrid and I didn’t

Advertisement

have any of my tools. And I thought, “Well, geez, I guess I won’t be making art. I’ll do some writing.” And the writing lasted for about a week. Then I went out and there was a flea market, I got a hot glue gun, I found these images of religious icons, and then it was off to the races again. I think it was just, “Oh, shit, what am I going to do?” And then before I knew it, I was doing it. How often have you had to re-learn that in your life? Telling yourself you won’t make art and then you’re back in?

All the time, I’ll think, “Dude, I’m not gonna do collages anymore—you know what, fuck this shit. I’m just gonna take a break. I’m gonna read!” But then I’m up at Griffith Park, walking around finding a piece on the ground I don’t know what I’m gonna do with it, and then the next thing I know, I go, “Okay, I’ll just do a little bit of work in the studio.” It’s really embedded in me now. It’s where I go for comfort. It’s my comfort food. Where did the name “CRU art” come from? It’s all perspective. Looking back to last March, feeling like our whole world was shutting down and how truly strange and empty that time felt—and now, through all the terrible things, time feels like the biggest gift anybody’s ever given me. It was also nice. I never had this time hanging out with my dad—I just never got the time. I was mostly hanging out with my mom. To have both parents home, to see how enmeshed you can become is an interesting time for defining too—even developmentally. Is it a hindrance for kids? I think it’s absolutely a hindrance for adults. I think it’s like, “Errr,” it’s an e-brake. We’ve also gotten really into going to see our folks. There’s a lot of family time, which is what America needs more of. In my Latin roots, we always went to see my grandparents every Sunday. I had both sets of my grandparents within 45 minutes of each other from ages 12 to 23. That was pretty intense; you could do whatever you want, but on Sundays, you’re home. Do you miss that pace of the world ever?

Carlos Ricardo Ulloa—so I’ve got the name of two kings. [laughs] What do you think about teaching? I think about that a lot. I like hanging out with young people. It’s fun. Just getting Henrietta out here in the studio and seeing where her brain goes with collage, it’s just like, “Wow! What! You’re going at it. Those colors don’t match. No way!” I think that’s a desire just to be sort of walloped with something that’s totally different.

Well, now it’s all about me, me, me. Me. Me. It’s interesting, you look at NFTs, and then here I am, Venus of Willendorf. I’m looking at pre-Columbian mythology, trying to go back. It sort of feels weird to see this world jetting forward. It’s like when I’m in my 1973 Mercedes going 45 on the freeway watching Priuses and shit fly by me. Henrietta says, “Let’s race! Let’s race!” She wants to go fast. I say, “No, we can’t race we get to watch everybody go by.”

How do you define success? Have you ever wanted that blue-chip artist’s level of recognition? It oscillates, there’s a part of everyone—it’s not so much the fame, it’s not so much the money—it’s more just synchronicity with your fellow man, having a connection, having this connection with you guys. Or when I go into someone’s house and see one of my pieces there. It’s living among them, seeming a little ideological. But at this moment, the pleasure comes from going into someone’s house and being like, “Oh, I forgot you bought that piece.” It’s really the human connection to it.

It’s the polar opposite of an NFT. Yeah! [laughing] In your project, “UnGun Us” [above], you reveal the hiddenness of gun violence in and around Hollywood by installing brass plaques at the locations of murders. Where did the initial idea for this project come from? Were you close to gun violence or did you witness a murder at some point? Stolperstein, stumbling stones. When I lived in Germany, I would see them everywhere. When we lived in Panama, I went downstairs one day and somebody had gotten shot in our apartment building. They cleaned him up by the

time I came down but there was still blood everywhere. I was 11. I thought the dog was licking at red paint. That always stuck in my mind. Before “UnGun Us,” I was already doing these pieces that were sort of gun-related. It just shifted after Columbine, I think now it’s just gotten out of control. You have three avenues of art: street art, fine art, and then activism. Which do you find is the most fulfilling and allows for the most connection? Curious, because when you’re psychoanalyzing, you don’t want to say, “I’m compartmentalizing.” But it’s interesting; this fine art-making lives in the space where usually I can jump in and jump out. It’s just become part of life. I’ve got a couple hours here or there to work in the studio. Then the street art is Saturday and Sunday morning. I go to 7/11, get the coffee, ride around until I find the right spot. It’s beautiful. I have a little route, I see the guy that’s always there, I drink a shot of ginger, and stop for a little bit. It’s such a relaxing, tranquil time to see the city awaking. I just cruise around and that fills a place of a morning ritual—just being and seeing and experiencing. The city we live in has so much to reveal to us. It’s different being in a car or a pedestrian. I’m up and I know that I’m gonna find a spot out there. The girls are asleep and I’m just out on my bike, usually back by 9:30. The activism [UnGun Us] is more planning and there is a bit more adrenaline with that. Where am I going to go? It has movement, I get my tools and it’s, “Alright, let’s go.” They all sort of fill different spaces, fill different com-

partments. And yet they’re very connected, collaging myself into the fabric of the city. Do you guys know that word “flâneur”? It’s a French word for somebody who goes through the city and observes. I’m always enamored with that word. Anyway, there are two things I learned when I was doing my masters: one was hailing like you’re waving, and then the other one was flâneur. I always thought, “Wow, I do a little bit of all that stuff.” My sculptures are sort of waving trying to grab you. Unlike the “UnGun Us” plaques which recall the Stolperstein.

No one’s looking down. What does LA do for you as an artist? Here it’s 100 miles an hour but you’re in a Prius and it’s air conditioned.

Here your brain is going because you’re thinking. But in New York, your brain is like, “Okay I got to go here, watch the traffic, watch the street, I’m cold, I’m hot.” But in LA, your brain is going and it never stops. What happens in LA is that your possibilities are so big again. It’s flat—everything is so expensive. In New York it’s like Frogger.

Well, for one, the colors. It brought colors into my work, especially the street art. Then there’s the sun. There’s nothing like a Los Angeles sun; it’s like no other and hard to explain. It’s different in New York, it’s different in Germany, but there’s something about that LA sun that just sort of flattens everything out. There is no depth even though there should be. Something about this city, with all of its colors, it should be so deep—and yet, it’s so flat.

How do you feel living in New York and LA have made different impressions on your work? You know what it is? I think in LA, we’re in our pods—you miss so much. Then in New York, it’s so condensed that you can just walk right by something a million times and you’d never know it was there. When you’re in New York it’s great because you can just say “Fuck you” to someone and right back they’ll go “No, fuck you!” “Alright man, have a good one.” You don’t get that here. There it’s 100 miles an hour.

Have you always been collecting? I lived in Panama as a kid and I would jump on a train and go across the isthmus and go to Port Cologne. You’d have the west side and the east side and we’d go to the west side port—and that’s where all the ships would land. There were beer cans always floating in the corners. I would take a stick and pull them out. I started a beer can collection and for some reason, that took precedence when we were moving. My mom would say, “Okay, we got to pack up the beer collection.” So eight boxes of beer cans showed up on the other side. Even when I moved from Germany to LA, I asked my brother Andy for help moving. I had a couple of boxes that had all my tools in the garage. I need my tools. I had a ton of wood sticks and materials and shit. And then he comes over to help me unload. And he’s like, “What the fuck is all this?” It looks like trash to him. I’m like, “Dude, I can’t. This is

it.” You know unfinished sculptures, finished sculptures—there was a lot of shit. Crazyville. I mean it’s in all of us right. Some people collect Ferraris, some people collect garbage. I like that idea, that it’s within you. Doesn’t matter if you’re in Panama or Hancock Park—you can do it anywhere. You know what I dream about is having a big fucking barn. And then I wonder what that’s gonna bring? Wait, a bar or barn?

A barn, I’ve already had a big fucking bar dude. [laughing] What was that experience from beginning to end with Yamashiro? I came in to fix The Magic Castle. After a while I couldn’t do the Castle anymore, so I got a bit of a leg up because my stepfather owns the thing. My brother was running Yamishiro and he brought me in. It’s hilarious—my office started at the lowest point on the hill and by the end I’m at the top trying to sell the thing. I was like, “This is amazing; this is crazy.” I remember my last day being up there, I showed up with a Miller Highlife, a big caguama, and a bag of Cheetos. I went up there at three o’clock in the morning. It’s the same way I did it when I started. I was drinking my beer, sitting on a bench that looks over the big Buddha.

And then Omar, you remember Omar? The security guard, he goes: “Boss? What are you doing here?” “I’m saying goodbye, man.” He’s like, “Really? I’ll leave you alone. Can I come back in like, 20 minutes?” “Sure.”

I drank my Cheetos, drank my beer. And that was it. That was it and I was happy with it.

You don’t miss it at all?

No, it was crazy. You’re at the pinnacle, looking down on Hollywood, you’re thinking this is amazing, and—I mean frankly I think about dodging a bullet right now during this pandemic—it would be fucking nuts to still own it.

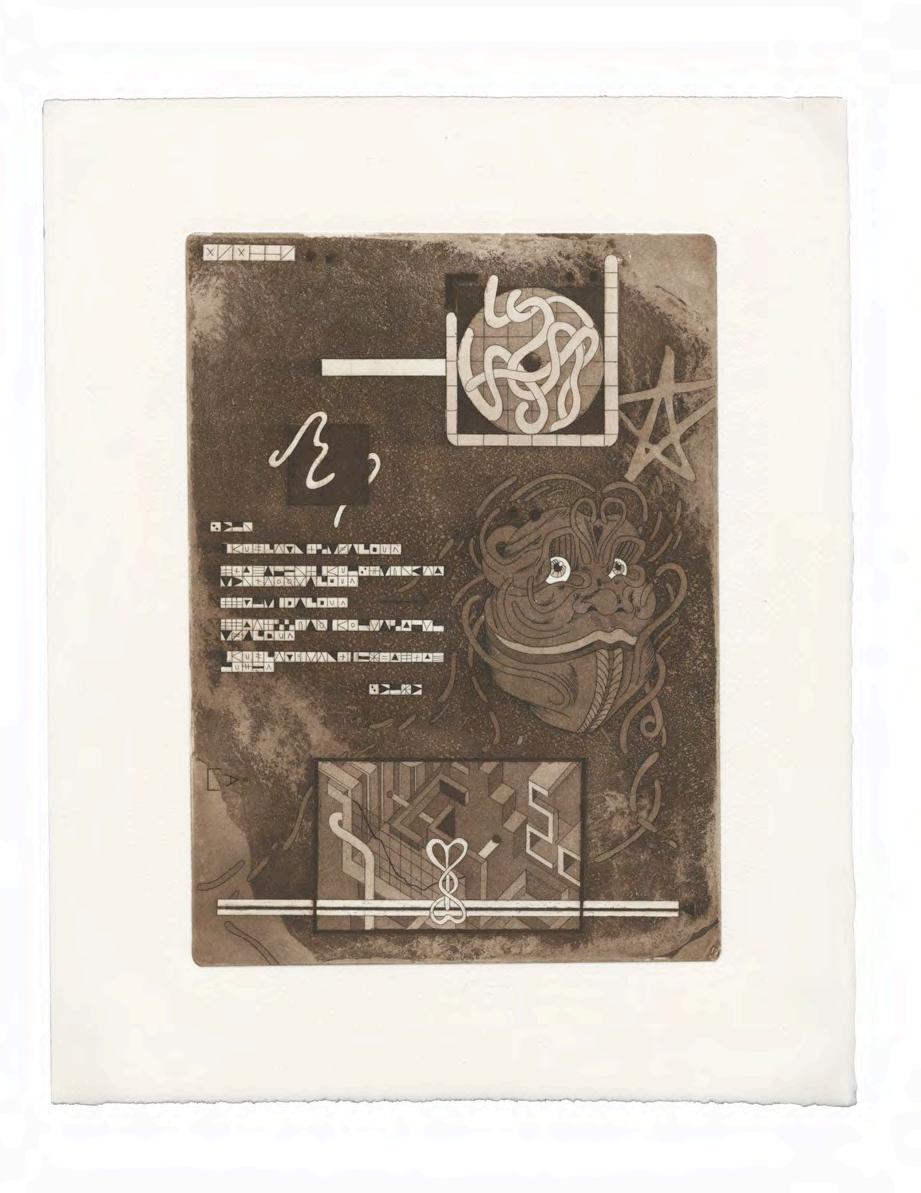

How do you think you’ve changed as an artist and person? I get to see how my work has gone from having a very academic approach to it—casting bronze, carving, using mythology of the artists that came before me—that sort of loaded iconography. Now it’s coming to simpler and simpler expressions of what’s available to me. I would love to be casting bronze—that would be fun. I just, I don’t think I’d know what to do with it anymore. There was a time when I’d love to sculpt, getting in there with chisels. Now it’s so much more interesting for me to just find and assemble things. The less I have to manipulate them, the more exciting it is to me.

THANK YOU

JULIETTE AMBATZIDIS ARISTOTELIS AMBATZIDIS JOJI BARATELLI CRAIG BARRON CONRAD BLACK SCOTTISH CHARLIE HOLDEN FULLER ADDIE GRUSZYNSKI PETEY GRUSZYNSKI ANNIE JACOBSEN KEVIN JACOBSEN JETT JACOBSEN LEXA KREBS CHRISTOPHE LOIRON FLO NGALA CHARLIE SANDS LUNA SANTAOLALLA DON JUAN SANTAOLALLA LUCAS ZALDUONDO KELLY & BOB DYLAN

WWW.CHUCK.LAND

THANK YOU FOR READING