NOTES ON THE PROGRAM

Rhapsody at 100: A Celebration of George Gershwin

When planning a celebration of the 100th anniversary of Rhapsody in Blue—an extremely popular, innovative, but also relatively short work of roughly 17 minutes—it is almost a necessity to explore Gershwin’s entire creative arc, from his origins in Tin Pan Alley through his grand achievements on stage and screen. As wonderful as his music is in all its forms, his life and career are equally inspiring.

Origins

George Gershwin, born Jacob Gershwine in 1898 in Brooklyn, New York, came from a Russian-Jewish immigrant family. His musical journey began somewhat unexpectedly when his parents bought a piano for his older brother Ira. To everyone’s surprise, it was George who showed a natural affinity for the instrument. He began taking piano lessons at age 12 and quickly progressed, studying with various teachers including Charles Hambitzer and Edward Kilenyi.

In his teenage years, Gershwin left school to work as a “song plugger” in New York City’s Tin Pan Alley. A song plugger was essentially a musical salesperson whose job was to promote and demonstrate new sheet music to potential buyers. They would play and sing songs in music stores, vaudeville theaters, and other venues to generate interest and boost sales. Gershwin played an incredible amount of music across song writers and styles. He was a sponge—not only developing his skills as a pianist and performer, but also laying the groundwork for his own songs.

His first published song, “When You Want ‘Em, You Can’t Get ‘Em, When You’ve Got ‘Em, You Don’t Want ‘Em,” was released in 1916 when he was just 17 years old. This marked the beginning of his career as a songwriter, and he soon gained recognition for his innovative melodies and rhythms that blended elements of jazz, popular music, and classical styles.

“Love Is Here to Stay”

George Gershwin composed “Love Is Here to Stay” in 1938 during what would tragically be the final months of his life. The song was written for the film The Goldwyn Follies, which was released in 1938 after Gershwin’s untimely death in July 1937. This poignant fact adds a layer of meaning to the song’s theme of enduring love.

The composition process for “Love Is Here to Stay” was a collaboration between George and his brother Ira Gershwin, who wrote the lyrics. It was one of the last songs they worked on together, marking the end of a prolific partnership that had produced numerous American classics. The melody showcases George’s talent for creating memorable,

emotionally resonant tunes, while Ira’s lyrics beautifully complement the music with their message of eternal love.

After George’s passing, Ira made some modifications to the lyrics, possibly as a tribute to his brother. The song quickly gained popularity and has since become one of the most beloved standards in the Great American Songbook. Its enduring appeal lies in its simple yet profound message and the perfect marriage of Gershwin’s evocative melody with Ira’s heartfelt lyrics. “Love Is Here to Stay” stands as a fitting final testament to George Gershwin’s extraordinary musical legacy.

“Someone to Watch Over Me”

In 1926, Gershwin wrote “Someone to Watch Over Me” for the Broadway musical Oh, Kay! The song was originally conceived as an up-tempo dance number, a fact that might surprise those familiar with its now-famous ballad rendition. Gershwin reportedly composed the melody very quickly, allegedly in just ten minutes while at a party. This speaks to his remarkable ability to create memorable tunes seemingly effortlessly.

The transformation of “Someone to Watch Over Me” from a fast-paced song to the tender ballad we know today occurred during the show’s out-of-town tryouts in Philadelphia. The show’s star, Gertrude Lawrence, suggested to Gershwin that the song might work better as a ballad. Gershwin agreed to experiment with the tempo, and the slower version proved to be far more effective. This change highlights the collaborative nature of musical theater and Gershwin’s willingness to adapt his work for the better.

The lyrics, written by George’s brother Ira Gershwin, tell the story of a young woman longing for love and protection. Ira’s words perfectly complement the wistful quality of the slowed-down melody. The song’s emotional depth and universal theme of seeking companionship and security have contributed to its enduring popularity. “Someone to Watch Over Me” quickly became a hit beyond the context of the musical, establishing itself as a standalone classic in the American songbook. Its journey from an uptempo dance tune to a beloved ballad is a testament to the Gershwin brothers’ musical instincts and their ability to create songs that resonate deeply with audiences.

Porgy and Bess: “Selection for Orchestra” (arr. Robert Russell Bennett)

Influenced by African American folk music and inspired by DuBose Heyward’s novel Porgy, Gershwin immersed himself in the Gullah culture of South Carolina to create what would become his magnum opus. The opera, which premiered in 1935, initially ran over four hours, but was later condensed to about three hours for commercial viability.

To make the music of Porgy and Bess more accessible to a wider audience, Gershwin himself arranged a concert suite titled Catfish Row in 1936. This suite included orchestral versions of several key musical numbers from the opera, allowing the music to be performed independently of the full stage production. Other arrangements followed,

including songbook versions of individual arias and duets, which helped popularize many of the opera’s most memorable tunes.

Robert Russell Bennett, a renowned orchestrator and composer, took a particular interest in Gershwin’s work for several reasons. Firstly, Bennett was deeply impressed by Gershwin’s unique ability to blend popular and classical styles, a quality that aligned with Bennett’s own versatile approach to music. Secondly, as a leading orchestrator of Broadway shows, Bennett recognized the immense potential in Gershwin’s compositions for symphonic adaptation. Lastly, Bennett had a personal connection to Gershwin, having worked with him on several Broadway productions. This professional relationship and mutual respect likely fueled Bennett’s desire to continue promoting and adapting Gershwin’s music after the composer’s untimely death in 1937.

Among Bennett’s notable works based on Porgy and Bess is the “Selection for Orchestra,” a work that contains iconic melodies such as the haunting lullaby “Summertime,” the upbeat “I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin’,” and the romantic “Bess, You Is My Woman Now.” These themes, carefully arranged by Bennett, showcase the orchestra while capturing the rich musical tapestry of Gershwin’s original work, making it suitable for concert performances where the full opera cannot be staged. Bennett’s skill in orchestration ensures that the distinctive character of Gershwin’s music, with its blend of classical, jazz, and folk elements, is fully preserved.

An American in Paris

George Gershwin conceived An American in Paris during a trip to the French capital in 1928. Inspired by the vibrant atmosphere and the sounds of the city, Gershwin aimed to create a tone poem that would capture the essence of an American tourist’s experiences in Paris. His influences ranged from the bustling streets and cafés to the more melancholic moments of homesickness. Gershwin’s process involved immersing himself in Parisian life, even going so far as to purchase Parisian taxi horns to incorporate authentic city sounds into his composition.

During this period, Gershwin was actively seeking to establish himself as a serious composer in the classical music world. He approached both Maurice Ravel and Nadia Boulanger for composition lessons, but both declined. Ravel famously quipped, “Why become a second-rate Ravel when you’re already a first-rate Gershwin?” Nadia Boulanger, a highly respected composition teacher who had instructed many notable composers (including Leonard Bernstein), told him, “I can’t teach you anything. You already have a wonderful style of your own.” Certainly Gershwin had come a long way from his years as a “song plugger.”

There are strong parallels between Gershwin’s An American in Paris and Debussy’s La Mer. Both works employ a tonal language that blends impressionistic elements with their respective national musical idioms. Gershwin incorporates jazz and blues influences alongside more traditional orchestral techniques, much as Debussy infused French musical traditions with his innovative harmonic language. Both composers saw these

works as significant achievements in their careers, continually refining them. Gershwin, like Debussy with La Mer, made revisions to An American in Paris up until his untimely death in 1937.

After Gershwin’s death, his music found new life in the 1951 MGM film An American in Paris. F. Campbell-Watson, a respected arranger, was brought in to adapt Gershwin’s score for the film. Interestingly, Campbell-Watson did not use the most recent version of the composition as his basis. Instead, he made significant revisions to an early version to achieve a more “Hollywood” sound, and it is this version that is most frequently listened to and performed today.

F. Campbell-Watson wasn’t the only person to impact how we hear An American in Paris. In the score, Gershwin referred to each of the four taxi horns with the letters A), B), C) and D), which were intended to identify distinct taxi horns that he had purchased while in Paris. Arturo Toscanini interpreted these letters as actual pitches, and had a set of taxi horns made tuned to these pitches. From that point forward, every recording of An American in Paris used taxi horns pitched as A, B, C and D. It wasn’t until researchers at the University of Michigan discovered an early recording of An American in Paris that was supervised by Gershwin, that we knew exactly how the taxi horns were intended to be pitched (A-flat, B-flat, high D and low A). Gershwin’s intention was to mimic the variety of sounds on the street, achieving a variety of pitches from very low to very high. A photo from that recording session confirms the alternate tunings.

This performance includes both Gershwin’s original orchestration and the correct taxi horn pitches.

An American in Paris itself is a vibrant, colorful work that musically narrates an American’s adventures in Paris. It begins with lively, walking-pace themes representing the tourist’s excited exploration of the city. The famous taxi horn motifs punctuate the bustling street scenes. As the piece progresses, it incorporates elements of French music, including quotes from popular songs of the time. A more introspective, blues-influenced section in the middle suggests moments of homesickness or reflection. The work concludes with a return to the exuberant mood of the opening, celebrating the joie de vivre of Paris. Throughout, Gershwin’s orchestration is rich and varied, showcasing his growth as a composer of orchestral music and his ability to blend jazz idioms with classical forms.

An American in Paris has left an indelible mark on popular culture, extending far beyond its origins as a symphonic tone poem. Its most famous use is undoubtedly in the 1951 MGM film of the same name, starring Gene Kelly, which won six Academy Awards including Best Picture. The music has since been featured in numerous films and television shows, often to evoke a sense of romance, adventure, or Parisian ambiance. For instance, it appears in episodes of “The Simpsons” and “Gossip Girl,” and in films like Mr. Holland’s Opus (1995) and Midnight in Paris (2011). In advertising, the piece has been used to sell products ranging from perfumes to luxury cars, capitalizing on its associations with sophistication and Parisian chic. The work’s enduring popularity has also led to its inclusion in various video games, particularly those set in historical or fantastical versions of Paris. Its use in

these diverse media has helped maintain Gershwin’s relevance to new generations and solidified An American in Paris as a cultural touchstone representing the excitement and romance of the City of Light.

Rhapsody in Blue

In 1924 Paul Whiteman, a popular bandleader, wanted to organize a concert titled An Experiment in Modern Music to demonstrate that jazz could be presented as a serious musical form. Whiteman asked Gershwin to compose a concerto-like piece for the event. Gershwin declined, thinking he didn’t have enough time to create such a work. A few days later Gershwin was playing billiards when his brother Ira burst through the door with a newspaper article proclaiming that Gershwin was working on a “jazz concerto” for Whiteman’s concert. It turns out Whiteman “leaked” this to the press to pressure Gershwin to write the concerto.

With only five weeks until the concert, Gershwin set to work. He composed the bulk of Rhapsody in Blue on a train journey to Boston, inspired by the rhythm of the train’s movements. The piece was orchestrated by Ferde Grofé, Whiteman’s arranger, as Gershwin was still learning orchestration. Interestingly, Gershwin left space in the score for piano cadenzas, which he intended to improvise during the performance. This decision reflected the jazz influence on the piece and Gershwin’s own background as a skilled improviser.

The premiere of Rhapsody in Blue took place on February 12, 1924, at New York’s Aeolian Hall. Gershwin himself played the piano part. The performance was a resounding success, with the audience including notable composers like Igor Stravinsky and Sergei Rachmaninoff. One famous anecdote from the premiere involves the opening clarinet glissando. The clarinetist, Ross Gorman, had playfully improvised this part during rehearsals, adding a wailing effect that wasn’t in the original score. Gershwin liked it so much that he asked Gorman to perform it that way in the concert and it has since become one of the most recognizable openings in music history.

In the decades since its premiere, Rhapsody in Blue has been performed countless times by renowned orchestras and pianists worldwide. Notable performances include Leonard Bernstein’s 1976 televised concert with the New York Philharmonic, where he conducted from the piano, and a 1988 performance by the Los Angeles Philharmonic conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas with pianist Marcus Roberts, which emphasized the work’s jazz roots.

Rhapsody in Blue has become deeply ingrained in popular culture. One of its most famous uses in film is in Woody Allen’s 1979 movie Manhattan. Allen had originally temp-tracked the film with music by Mozart but felt it didn’t capture the essence of New York. He then tried Gershwin’s music, including Rhapsody in Blue, and found it perfectly embodied the city’s energy and romance. The iconic opening shot of the New York skyline set to the swelling notes of Rhapsody in Blue has become one of cinema’s most memorable moments.

The piece also gained widespread recognition through its use by United Airlines. In 1987, United was looking for a new musical theme for their advertising. They approached the Gershwin estate and, after negotiations, acquired the rights to use Rhapsody in Blue. The airline’s advertising agency, Leo Burnett, chose the piece for its ability to convey a sense of sophistication, excitement, and the grandeur of air travel. United has used various arrangements of the piece in their marketing ever since, making the opening clarinet glissando almost synonymous with their brand. This long-standing association has helped keep Rhapsody in Blue in the public consciousness and has introduced the piece to new generations of listeners.

Program Notes by David Bernard

MEET THE ARTISTS

SARAH ELLIS

Vocalist

Sarah Ellis is an NYC-based actor, concert artist, and film producer. Her professional credits span across theatre, film, dance, commercial, and symphony work, locally in new works readings and labs in NYC, regionally as a leading lady in award-winning theaters across the country, including the First National Tour of the TonyAward Winning A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder, and as a frequent guest artist with symphonies around the country. Sarah is currently parrothead-ing (?) in Jimmy Buffet’s Escape to Margaritaville over in Bellport, Long Island at The Gateway Playhouse. She holds a BFA in Musical Theatre from Penn State University where she received the Margaret “Peg” French Undergraduate Award in Theatre. Sarah is the Co-Creator of the award-winning indie film company MT SHORTS @mt_shorts. She is the commercial spokesperson for OHLQ.COM. Sarah has an exciting summer of shows ahead! For updates: www.meetsarahellis.com. For adventures: IG/TIKTOK: @iamsarahellis

TED ROSENTHAL

Pianist

Ted Rosenthal is one of the leading jazz pianist/composers of his generation. He actively tours worldwide with his trio, as a soloist, and has performed with many jazz greats, including Gerry Mulligan, Art Farmer, Phil Woods, Bob Brookmeyer, and James Moody.

Winner of the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Piano Competition, Rosenthal has released fifteen CDs as a leader. Rhapsody in Gershwin, which features his arrangement of Rhapsody in Blue for jazz trio, reached #1 in jazz album sales on iTunes and Amazon. Wonderland was selected as a New York Times holiday pick, and received much critical praise: “Sleek, chic and elegant” – Howard Reich, Chicago Tribune. Impromptu showcases his reimaginings of classical themes for jazz trio. “A serious listen to Impromptu will be a mind-changing experience...sit back and enjoy these wonderfully creative takes on ten compositions from the classical canon that have never sounded so cool.” - Elliott Simon, AllAboutJazz.

Rosenthal’s solo album, The 3 B’s, received 4 stars from DownBeat magazine. It features music of Bud Powell, Bill Evans and his improvisations on Beethoven themes. “In

Rosenthal’s hands all this music sounds as though it sprang from the same muse, and that’s the sign of a skilled, imaginative artist.” - David R. Adler, All Music Guide.

A recipient of three grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, Rosenthal regularly performs and records his compositions, which include jazz tunes and large-scale works. Rosenthal’s jazz opera, Dear Erich, was commissioned and premiered by New York City Opera in 2019, and will make its Tilles Center debut in March 2025. Dear Erich attracted much press and critical acclaim: “Compelling...tells a true, wrenching story. Rosenthal’s score conveys regret and fragility, with scenes that invite real breakout jazz” – A. Tomassini, New York Times “Leaves the listener ready to explode with applause” - D. Salazar, Opera Wire.

Rosenthal has also been commissioned by Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, The Park Avenue Chamber Symphony, and Dallas Black Dance Theatre. The Survivor, his concerto for piano and orchestra, has been performed by the Manhattan Jazz Philharmonic and the Rockland Symphony Orchestra, with Rosenthal at the piano. Rosenthal premiered his second jazz piano concerto, Jazz Fantasy, with The Park Avenue Chamber Symphony.

Rosenthal was artistic director of Jazz at the Riverdale Y and Jazz at Dicapo Theatre, both in New York City. He has also performed with Wynton Marsalis and the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, The Vanguard Jazz Orchestra, and Jon Faddis and the Carnegie Hall Jazz Band. In addition, Rosenthal has been the pianist of choice for many top jazz vocalists including Helen Merrill, Ann Hampton Callaway, Kurt Elling and Barbara Cook. He appeared on Marian McPartland’s Piano Jazz on National Public Radio and performed with David Sanborn on NBC’s Night Music.

Rosenthal’s orchestral performances include solo and featured appearances with The Detroit Symphony, The Phoenix Symphony The Boston Pops, The Grand Rapids Symphony, The Rochester Philharmonic, The Pittsburgh Symphony and The Fort Worth Symphony. Rosenthal performed Gershwin’s Concerto in F and Rhapsody in Blue for the opening concert of the 92nd Street Y’s 2015-16 season. The New York Times called his playing “notable both for its flair and languid, sultry expressive gestures.” In 2014 Rosenthal performed Rhapsody in Blue at Town Hall in a concert celebrating the 90th anniversary of its premiere.

Rosenthal received his Bachelors and Masters degrees from the Manhattan School of Music.

Active in jazz education, he is on the faculties of The Juilliard School, and Manhattan School of Music, where he also served on their Board of Trustees and received the Presidential Medal for Distinguished Faculty Service. Rosenthal presents jazz clinics throughout the world, often in conjunction with his touring. He was a contributing editor for Piano and Keyboard magazine and has published piano arrangements and feature articles for Piano Today, The Piano Stylist and The Juilliard Journal. Ted Rosenthal is a Steinway Artist. His website is www.tedrosenthal.com.

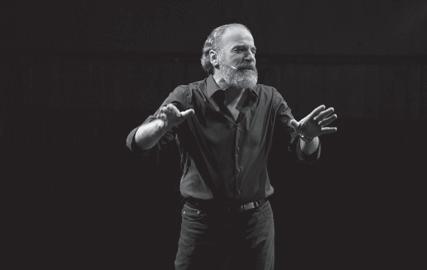

DAVID BERNARD

Music Director, Massapequa Philharmonic

David Bernard serves as Music Director of the Park Avenue Chamber Symphony, Massapequa Philharmonic and the Eglevsky Ballet. He is an active guest conductor, appearing with the Brooklyn Symphony, the Dubuque (IA) Symphony, the Greenwich (CT) Symphony, Greater Newburgh Symphony Orchestra, the Island Symphony, the Litha Symphony, the South Shore Symphony and ensembles from the Manhattan School of Music. Called “the Johnny Appleseed of Classical Music” by Long Island Weekly, Maestro Bernard has helped the arts thrive through his innovative approaches to audience and orchestra building as music director and guest conductor.

As a conductor of ballet, David Bernard has worked with dancers from the Eglevsky Ballet, New York City Ballet, Boston Ballet and the Miami City Ballet companies, including Jared Angle, Tyler Angle, Santiago Castañeda, Ji Young Chae, Jeffrey Cirio, Sarah Gavilla, Miriam Miller and Unity Phelan.

David Bernard is the Founder and Director of InsideOut Concerts, Inc., a pioneer and innovator in the design, development and production of immersive classical music events, and is inventor of US Patent No. 11,673,070 entitled “Methods and Systems for Arranging Seats for Audience Members and Musicians.” Bernard’s work using these methods in concerts and events resulted in not only increased tickets sales, but also increased organic new audience acquisition.

Bernard is the First Prize winner of The American Prize Orchestral Conducting Competition (professional division) 2019. In presenting this award, the panel of judges commented:

“Conducting from memory, David Bernard exhibits remarkable skill and considerable elan in a vibrant reading of Stravinsky Rite of Spring. Not content with a cool, furrowed-brow approach to this music, his interpretation is alive to the nuances of color and, indeed, the dramatic arc, of this legendary masterwork. His is a considerable achievement by any standard.” —The American Prize Competition Panel

David Bernard’s critically acclaimed performances and recordings include Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony at Carnegie Hall (“ taught and dramatic” - Superconductor), Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring at Lincoln Center (“transcendent...vivid...expertly choreographed” - LucidCulture), a complete cycle of Beethoven symphonies praised for its “intensity, spontaneity, propulsive rhythm, textural clarity, dynamic control, and well-judged phrasing” by Fanfare magazine, Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique Symphony (“parts emerge like newly scrubbed details in a restored painting. Bernard and his musicians frequently shed new and valuable light on a thrice-familiar standard” - Gramophone) and an album of Dvořák’s Late Symphonies (“David Bernard treats each of the symphonies with alert and respectful acuity. He trusts Dvořák’s metronome markings, often to surprising and exciting effect, and

makes sure the narratives unfold with seamless assurance. Bernard shapes the score with fine control, savouring its tender and invigorating material minus mannerism or bluster.”Gramophone).

Devoted to the music of our own time, he has presented world premières of scores by Bruce Adolphe, Chris Caswell, John Mackey, Ted Rosenthal and Jake Runestad, and distinguished concert collaborators have included Anna Lee, Jeffrey Biegel, Carter Brey, David Chan, Catherine Cho, Adrian Daurov, Pedro Díaz, Edith Dowd, Stanley Drucker, Bart Feller, Zlatomir Fung, Ryu Goto, Whoopi Goldberg, Sirena Huang, Judith Ingolfsson, Yevgeny Kutik, Anna Lee, Jessica Lee, Kristin Lee, Maxim Lando, Daniela Liebman, Jon Manasse, Christopher Martin, Anthony McGill, Spencer Myer, Todd Phillips and Inbal Segev.

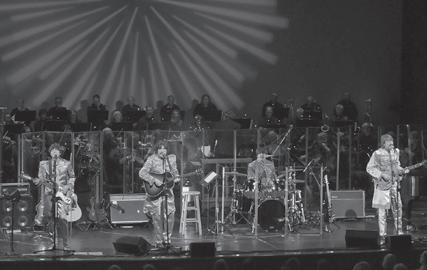

MASSAPEQUA PHILHARMONIC

The Massapequa Philharmonic Orchestra is Long Island’s premier orchestra, bringing cultural leadership and exciting concerts featuring world-class soloists to Long Island’s audiences for 40 years—an unprecedented achievement. Under the direction of renowned conductor, David Bernard, the Massapequa Philharmonic’ has built significant partnerships with the Eglevksy Ballet, Nassau County Museum of Art and the Massapequa Public Schools, as well as bringing immersive InsideOut events to audiences, fulfilling a vision of outreach and cultural leadership across Long Island. Under Maestro Bernard, the orchestra has performed sold out shows at the Madison Theatre at Molloy College and the Adelphi Performing Arts Center, and will begin its tenure as Resident Orchestra of the Tilles Center for the Performing Arts with Rhapsody in Blue at 100 in July 2024.

Massapequa Philharmonic performances are made possible by the generous support of the Decentralization Program, a regent program of the NY State Council administered by the Huntington Arts Council, the Town of Oyster Bay Arts Council, the Hilaria and Alec Baldwin Foundation and the generous support from the Long Island Community.

MASSAPEQUA PHILHARMONIC

David Bernard, Music Director

Violin

Aimee Lillienstein, Concertmaster

Eliza DellaMonica

Allison DuBois

Tay Kwak

Amy Noll

Jeffery King

Cindy Pacini

Rohun Rajpal

Tracy Souhrada, Principal

Diane Block

Monica Capiral

Anne Mandaro

Dawn Martin

Lesley Rosenthal

Michael Susinno

Kristine Winters

Jane Xia

Sabrina Zuniga

Viola

Emily Dana, Principal

Katherine Cahalan

Madeleine Carroll

Sandrs Herman

Rachel Krieger

Sofia Notar-Francesco

Carole Reinwald

Jennifer Trested

Cello

Gary Beck, Principal

Richard Gotlib

Lee Jonath

Christopher Jung

James Ryan

Helene Sherman

Aron Szanto

Bass

Kathleym Salinas

Philip Smith

James White

Michele Zwierski

Flute

Kennedy Burgess

Jenn Forese

Jennifer Haley

Oboe

Heather Donnelly

Markella Gross

Henry Mulligan

Clarinet

Valerie Jones, Principal

Ron Basirico

Bass Clarinet

Dennis McLoughlin

Saxophone

Alex Yu, Alto/Soprano

Timothy Hanley, Tenor/Soprano

Isabelle Mailman, Baritone/Soprano

Bassoon

Cindy Lauda

Gabriel Pomerantz

Horn

Megan Bastos

Andrew Brunson

Andrew Copper

Michele Grande

Trumpet

Christopher Brandine

Matthew Raskin

Ellen Ryan

Trombone

Edward Matin

Alec Vogel

Bass Trombone

Reid Rozen

Tuba

Jay Rozen

Timpani

Louis Winsberg

Percussion

Alene Abramson

Zachary Brewer

Steve Campanella

Matt Hanauer

Keyboard/Celesta

James Kendall