BULLETIN FOR PROFESSIONAL ADVISERS

2023

Christie’s Heritage and Taxation Advisory Service

lromanelli@christies.com

+44 (0) 20 7389 2725

1 Editorial Luisa Romanelli

2 The Portrait of Mai

Ruth Cornett

4 Reflecting on Twenty-Five Years of the Washington Principles on NaziConfiscated Art

Richard Aronowitz

6 Tax No Longer so Taxing for Divorcing Couples

Lara Barton and Polly Atkins

8 Collecting Women Surrealists at the National Galleries of Scotland

Patrick Elliott

14 The Situs of Cryptocurrency

Bruce Fleming

17 No. 8 King Street: Christie’s Home for 200 Years

Lynda McLeod

Since the last issue of the Bulletin, there have been numerous financial statements, chancellors, budgets and tax changes that have already been widely reported in the press. With the exception of our tax focused articles, we will not be looking at the wider effect of those amendments on the tax and heritage world here as there would be far too much to cover for one issue!

It has been, however, a pleasure to look back and feature Christie’s recent successes throughout the pages of this edition. In particular, it is wonderful to be able to report that the monumental jardinière (or fishbowl), the loan of which was written about in the previous issue, has since permanently joined the collection at Strawberry Hill through the acceptance in lieu scheme and negotiated by Christie’s. Our front cover also features Sir Joshua Reynolds’ exceptional Portrait of Mai (Omai), and Ruth Cornett reflects on Christie’s role in assisting with this groundbreaking international joint acquisition.

It is always satisfying to see works join museum collections throughout the UK, and also in this issue we hear from Patrick Elliott at the National Galleries of Scotland who has written about the recent additions by women artists to their world-class Surrealist collection. It is inspiring to hear in detail how their holdings have increased in recent years outside the acceptance in lieu scheme.

Elsewhere, two articles from Christie’s colleagues celebrate important anniversaries.

Richard Aronowitz, Christie’s Global Head of Restitution, looks back to the Washington Conference on Holocaust-Era Assets which was held in 1998, and reflects on the principles agreed at that landmark event 25 years on. I would encourage all readers interested in this subject to explore the series of events and talks that are being held throughout this year by Christie’s to discuss this important topic further.

Much closer to home, Christie’s is celebrating 200 years at No. 8 King Street and Lynda McLeod, archivist, looks back at the rich history that we have with this site. As she comments, we continue to welcome interested visitors to the presale viewings that have been held here since 1823 and the 2023 summer season is no exception, when London will again become the focus of the global art world.

We have also picked up another theme discussed in the previous edition, and Bruce Fleming of Buzzacott LLP explores the issues that arise when establishing the situs of cryptocurrency for tax purposes, an interesting topic that will no doubt become more pertinent in the coming years.

Finally, we feature an overview of the welcome tax change in the Capital Gains Tax treatment of assets passing between separating spouses by Lara Barton and Polly Atkins of Hunters LLP. An important change among the many tax updates over the past months that is certainly worth reviewing in more detail.

Cover SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS (1723–1792)

oil on canvas

Note

Copyright © Christie, Manson and Woods Ltd., and contributors 2023. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of Christie’s.

Comments and Suggestions

If you would prefer to receive future Bulletins by email or in PDF format, or if you have any comments or suggestions regarding the publication, please email lromanelli@christies.com

Christie’s

8 King Street, London SW1Y 6QT

Tel: +44 (0) 20 7839 9060

Ruth Cornett Senior Director, Christie’s Heritage and Taxation Advisory Service rcornett@christies.com

Ruth Cornett Senior Director, Christie’s Heritage and Taxation Advisory Service rcornett@christies.com

+44 (0) 20 7389 2102

Prior to joining Christie’s, Ruth Cornett worked as a tax adviser in a number of professional firms in the City and the West End of London. After training as an art historian and working as a curator in the V&A, Ruth changed careers in 1992, studying law and qualifying as a Chartered Tax Adviser (CTA) in 1998. Ruth has advised a broad spectrum of clients on a range of tax matters with a particular emphasis on capital gains tax, inheritance tax and income tax. To consolidate her expertise in these areas, Ruth qualified as a Trust and Estate Practitioner (TEP) in 2008. Ruth lectures frequently for Christie’s Education and STEP on tax and heritage matters, has contributed to leading publications in this field and sits as an observer on the Tax and Political Committee of Historic Houses (HH).

The recent acquisition by the National Portrait Gallery, London and the Getty, Los Angeles, of the Portrait of Mai (Omai) by Sir Joshua Reynolds marks a ground-breaking collaboration between these two institutions and, for the UK, the first such international arrangement. For Christie’s it has been a long journey in helping to support the transaction through advice and expertise to the former owner combining an intimate knowledge of the workings of the export licensing system and the art market. We can now share that this involvement spanned many years of conversations and careful consideration, involving specialists at Christie’s in British Pictures and Heritage and Taxation, together making an outstanding team and helping to deliver a result of historic proportions for all. For everyone at Christie’s the pleasure of seeing the Portrait of Mai on display to the public when the National Portrait Gallery reopens in June will be enormous.

There can be no doubt that the achievement of the National Portrait Gallery and the Getty together is both far-sighted and fitting to the life of Mai. As is well-documented, Mai left Polynesia to come to London in September 1773, aged about 20. On the voyage he was taught English and arrived in July 1774 able to converse in society. After spending around two years in England, charming and impressing everyone he met, Mai returned to Polynesia where it is thought he died a few years later. With the monumental portrait by Reynolds, Mai in his white robes is captured as a

technical a tour-de-force of light and an almost sculptural figure against an idealised background. Through this masterpiece, Mai lives and speaks to us today, perhaps more pertinently than ever before.

Much has been and will be written about how we relate to Mai today and the acquisition could not be more timely for the National Portrait Gallery in particular, with its long-awaited refurbishment coming to a conclusion.

Making this portrait available to so many people across the globe is an enormous achievement and anyone involved in the art world will be aware that the National Portrait Gallery has had a campaign for fund-raising for its share of the cost. It is well-known that the campaign has been supported by many generous donations, notably by the Art Fund and the National Heritage Memorial Fund, but private donors too were instrumental in securing the fund and their donations speak of generous philanthropy. Aside from the re-evaluation of the portrait, perhaps, too, it should give us all reason to consider how this joint acquisition demonstrates how museums and galleries have changed with the times. Might the acquisition of Mai demonstrate that the need for business acumen and good relations with all sectors of the art market is even more essential to the continuing life of these institutions than we ever thought—in the end might Mai’s gift to us be stronger hands of friendship across the global public and commercial art world?

Richard Aronowitz

Global Head of Restitution, Christie’s

Richard Aronowitz is Global Head of Restitution at Christie’s. He began his career in the art world as a furniture porter at Bonhams in 1993, then joined Sotheby’s as an Impressionist and Modern Art specialist in 1997 before leaving to become Director of the Ben Uri Gallery in 2003. He re-joined Sotheby’s as European Head of Restitution in 2006, then moved to Christie’s in March 2022 as Global Head of Restitution. Richard is the author of the novels Five Amber Beads, It’s Just the Beating of my Heart, and An American Decade, as well as a book of poetry, Life Lessons

The year 2023 marks a significant milestone in the restitution of art and cultural property that was lost, looted, confiscated, or sold under duress in Nazi Europe between 1933 and 1945. It is now 25 years since the Washington Conference on Holocaust-Era Assets, a multi-day gathering at the U.S. Department of State and at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., to which 44 countries (some, including Hungary, Poland, and Russia, having only recently emerged from behind the Iron Curtain) sent representatives, cultural ambassadors, and thought leaders to deliver statements on their countries’ thencurrent position on unrecovered Nazi loot.

In a major initiative led by Ambassador Stuart Eizenstat, at the time the United States Under Secretary for Economic, Business and Agricultural Affairs, who had convened the conference, one of the key achievements and lasting legacies of the event was the drafting and publication of the

Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art (‘the Principles’). The Principles are a set of eleven non-binding, moral-ethical codes—it must be emphasised that they are not laws nor do they have legal force— that still serve today as the bedrock of the work that provenance researchers and restitution specialists do around the world in the arena of unrecovered 1933–45 losses, whether that work be carried out in museums or on the international art market.

Principle no. 1 states that ‘Art that had been confiscated by the Nazis and not subsequently restituted should be identified’; Principle no. 3 says that ‘Resources and personnel should be made available to facilitate the identification of all art that had been confiscated by the Nazis and not subsequently restituted’; and Principle no. 5 proposes that ‘Every effort should be made to publicise art that is found to have been confiscated by the Nazis and not subsequently restituted in order to locate its pre-War owners or their

heirs.’ There is, then, nothing ambiguous about this language, and already 25 years ago the Principles made explicit the new standards of research to which the international art trade should be aspiring.

One of the key phrases that is embedded in the Principles is that of ‘just and fair solutions’ when discussing possible remedies that can be applied once a work that was lost, looted, or sold under duress during the Third Reich is discovered on the wall of a museum or emerges on the art market. Of course, ‘just and fair’ is a phrase that is open to a myriad of interpretations, none of which can be easily calibrated or defined in law. Fair to whom—to the current owner as well as to the claimants? How exactly do we measure what is just?

In practice, however, when through the careful research conducted by the dedicated team of provenance researchers within the Restitution Department at Christie’s, it is discovered that a work that has been consigned for sale has an unresolved Nazi-era ownership taint attached to it, acting as neutral intermediaries and using the Principles as a template, we try to initiate a dialogue between our consignor—almost always a good-faith owner to whom the news often comes as a tremendous shock—and the descendants of the family that lost possession of the work during the Third Reich. The moralethical force of the Principles provides the framework for us to initiate such a dialogue, and the aim of this mediation is a settlement between the parties that often results in the sale of the work pursuant to a joint written settlement agreement allowing for the sharing of the sale proceeds and, through this, the lifting of the ownership taint.

The approach taken to righting the historical wrongs of the looting and forced sale of art and cultural valuables that took place between 90 and 78 years ago now is, then, necessarily a pragmatic one

on the international art market. Yet the pragmatic, usually financial resolution of long-enduring taints attached to works that emerge on the market is underpinned by a deeply-felt need to do the right thing.

The Principles and their recommendation for seeking ‘just and fair’ solutions enable the Restitution team, working closely with our expert departments, to do so by first conducting research into the ownership history of the works that Christie’s intends to sell, and then by trying to initiate dialogues that lead to such settlements where an unresolved taint is discovered. Without the Principles, and without the Washington Conference that led to them under the inspired stewardship of Ambassador Eizenstat, none of this would be possible and the historical wrongs in this arena would continue to be perpetuated, often entirely undetected and unrecognised, down the generations.

Throughout 2023, Christie’s has shaped a programme of events in locations around the world, including Paris, Palm Beach, Amsterdam, San Francisco, Vienna, London, Berlin, Hamburg, New York, and Tel Aviv, that both reflect on restitution, looking back on what has been achieved over the last 25 years and forward to the work that still remains to be done, and celebrate the impact that the Principles have had.

And that impact has been seismic. Before 1998, any auction house or art dealer could sell with near-complete impunity and any museum could hold undisturbed in its collections a work that was lost during the Third Reich and that remained unrecovered after 1945, as there was no mechanism—beyond costly, complex, time-consuming litigation in the very few jurisdictions where that was even possible— for families to make a claim to a work that had been lost or sold under duress.

Following the conclusion of the Washington Conference on 3 December 1998, things gradually began to change. While there was perhaps no overnight epiphany despite the Principles being published at the very beginning of 1999, awareness of the looting of art and cultural property from Jews in Nazi Europe slowly began to grow, having been largely undiscussed between the winding down of the activities of the Allied Monuments Men and Women in the early 1950s and the 1990s, when major monographs on the vast subject area of Nazi loot and wartime losses began to be published by historians such as Lynn Nicholas (The Rape of Europa) and Hector Feliciano (The Lost Museum). No longer was it plausible simply to plead ignorance on the subject.

I spent the latter half of the 1990s working as a specialist in the art world, chiefly in Impressionist and modern art. Having looked with curiosity at the Jewish names printed in the pre-World War II provenances of so many works in the hundreds of auction catalogues from the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s from the international and regional auction houses, and having wondered exactly what had happened to those people and those works between 1933 and 1945, I took a particular interest in what had taken place in Washington at the end of 1998 and the highly important work that Ambassador Eizenstat had done in convening the conference and in leading the drafting of the Principles.

Little did I know that only half a decade later, in 2006, the narrative arc of my career would take me from being a fine art specialist looking at the fronts of works to becoming a provenance researcher who looked at their backs for any evidence of stamps, labels, inventory numbers, or inscriptions that might reveal something about their Nazi-era ownership history and their fate, and that of their owners, during the Third Reich.

Lara Barton

Hunters Law LLP

Lara is a partner in Hunters’ Private Client team. She has substantial experience of advising in relation to wills, trusts, powers of attorney, Court of Protection matters, probate and estate administration, including complex areas of expertise and cross-border matters. She also has an interest in art and cultural heritage law.

Long-awaited reforms easing the Capital Gains Tax (CGT) burden on asset transfers between separating spouses and civil partners were confirmed in the 2023 Spring Budget. The changes follow years of work by practitioners to highlight the difficulties created by the application of the CGT rules to divorcing couples.

The reforms involve the widening of two key tax reliefs: the ability of spouses to make transfers between themselves without attracting CGT, and the exemption of primary residences from CGT. We consider each in turn.

were ‘separated in such circumstances that the separation is likely to be permanent’; a vague concept open to interpretation.

Following the tax year of separation, the spouse making the transfer would be assessed as doing so at market value, and subject to CGT in the usual way. This would apply, for example, when a holiday home or investment property, shareholding or piece of art was transferred from joint names into one spouse’s sole name.

Polly Atkins

Hunters Law LLP

Polly is an associate in Hunters’ Family and Dispute Resolution team. Her work primarily focuses on relationship generated trust and inheritance act disputes. She has been recognised in the Legal 500 2023 as ‘fast establishing a reputation as sure-footed and cool under fire.’

Financial settlements on divorce often involve spouses transferring jointly owned assets into the sole name of one party, or transferring assets from one to the other. As many readers will know, spouses can transfer chargeable assets between them without a CGT charge arising. The person receiving the asset is treated as acquiring it at the value at which their spouse acquired it such that no gain, and therefore no tax, arises at that time. Transfers between spouses are therefore described as taking place on a ‘no gain no loss’ basis.

But, as the saying goes, all good things must come to an end, and tax reliefs are no exception to that rule—or at least they did not use to be: ‘no gain no loss’ transfers between spouses ceased to be available after the end of the tax year in which they separated. This rendered the relief unavailable to many divorcing couples, creating significant tax bills at what, for many, was already a time of financial pressure.

The rules resulted in the peculiarity that a couple separating on 4 April would have one day to transfer their assets without triggering a tax charge, whilst a couple separating two days later would have a full year to do so. A couple would be treated as separated if they

Unsurprisingly, most separating couples did not anticipate that dividing up their assets on divorce would generate a tax liability if not carried out within the tax year of separation. Even for those taking early legal advice, it was often not practicable to agree and implement a settlement within the tax year of separation, not least due to the lengthy delays in the family court.

This often resulted in cashflow difficulties: the transfer of assets between spouses created a tax liability but no assets had been realised to fund the tax. In particular, since April 2020, CGT has had to be paid on transfers of residential property within 30 days of the transfer. In some cases, the tax position meant parties had to sell assets they would otherwise have retained.

The new legislation goes a long way towards alleviating this problem. Under the new rules, any transfers between separating spouses will be at 'no gain no loss', with no immediate CGT payable, if they take place in accordance with an agreement between the parties in connection with their divorce or separation, or under a court order determining the financial arrangements to be made on divorce. There is no time limit on this, so even spouses who do not determine and implement their financial settlement for many years after their separation will be able to benefit.

Those who transfer assets between them other than as part of an agreement will need to be more careful. In such circumstances the ‘no gain no loss’ rule will apply for three years from the end of the tax year of separation. Say, for example, five years after Gina and Ali separate, they have not reached an overall financial agreement, but Gina gives a jointly-owned sculpture that she never liked to Ali. The transfer may attract CGT if it does not take place within the context of an agreement or court order.

The new rules will apply to disposals occurring on or after 6 April 2023 (although note that determining the date when an asset is ‘disposed of’ for CGT purposes can be complex in the context of divorce). This will undoubtedly ease the burden on separating couples from a cashflow perspective, and remove pressure to rush into decisions about how to share assets before the end of the tax year of separation.

Of course, the CGT charge does not disappear, rather the gain is held over until a subsequent disposal of the asset. At that point, the spouse who then owns the asset will be responsible for paying any CGT on the gain arising over the entire period of both spouses’ ownership. The latent gain at the time of the transfer between the spouses therefore cannot be ignored; it must be factored into the value attributed to the asset when the parties are negotiating a financial settlement. There is also a practical aspect: the party receiving the asset should ensure they have all the necessary documentation to enable them to calculate the gain and complete the return at some future point. This may include evidence of the price paid, acquisition costs and improvement works.

As many readers will know, an individual is not subject to CGT on their only or main residence, provided certain conditions

are met. However, under the old rules, separating spouses could lose part of their entitlement to this relief. This generally happened in one of two ways.

The first was where one spouse moved out of the family home on separation and the property was sold more than nine months later. This timeline is not unusual, as the process of deciding whether the home should be sold, and then completing a sale, can take some time. Under the old rules, the spouse who moved out would be subject to CGT in respect of the period from nine months after they moved out until the property was sold.

Under the new rules, the spouse who moves out can claim PPR for the entire period after they vacated the property, so long as the sale takes place within the context of an agreement or order made on divorce, their spouse has remained living in the property as their main home, and they are not claiming the relief in respect of any other property. This change is a fair reflection of the reality facing divorcing couples.

The second scenario in which entitlement to the relief could be lost is more complex. Say Samiya and Marc agree that the family home will be transferred to Samiya for her and the children to live in until the children finish school, following which it will be sold and Samiya will pay Marc a share of the sale proceeds. Such arrangements (known as ‘mesher orders’ or ‘deferred sales’) have the advantage of enabling the children to remain living in their home, but until now have had adverse tax consequences—Marc would not be able to claim PPR relief in respect of the deferral period, meaning he could face a significant tax bill when the property was sold, even though it had been Samiya and the children’s main home.

Under the new rules, when the home is eventually sold, the funds received by

Marc would be treated as if they arose on the transfer of his interest to Samiya some years earlier, meaning that he would likely be entitled to claim PPR relief on the transfer. This change is particularly welcome, as a deferred sale is often agreed for the benefit of the children. Such arrangements may now come back into favour for wealthy families who have assets available to meet the needs of the spouse who moves out of the family home.

The changes in CGT rules will assist divorcing couples in minimising and managing the CGT implications of separating their financial affairs, significantly reducing the time pressures and liquidity issues arising from CGT on divorce. Couples will be able take their time to make decisions that are right for them and their family, rather than being rushed into arrangements selected for their tax efficiency.

Professional advice will remain important to ensure that separating spouses understand the tax consequences of proposed settlements, that settlements are structured to take advantage of the new rules, and that all necessary documentation is shared and returns filed. Whilst CGT has historically been the most significant tax to consider when advising on divorce settlements, often posing a hidden trap for the unwary, the new rules should alleviate this extra challenge at what is already a difficult time.

Patrick Elliott has been a curator at the National Galleries of Scotland for over 30 years. He has been responsible for major exhibitions including Alberto Giacometti (1996), René Magritte (2000), Tracey Emin (2009) and Cut and Paste: 400 Years of Collage (2019) and is the curator of the forthcoming retrospective Grayson Perry: Smash Hits, opening in Edinburgh in July. He takes an active role in the acquisitions programme and is a trustee of the Henry and Sula Walton Fund.

People are often surprised to find that the Surrealist collection at the National Galleries of Scotland (NGS) in Edinburgh is one of the best in the world. Why has Edinburgh got such a great collection? It comes down to hard work and foresight combined with serendipity.

We were on excellent terms with two of the most important British collectors of Surrealism, Roland Penrose (1900–1984) and Gabrielle Keiller (1908–1995). Penrose had been part of the Surrealist movement and acquired most of his collection in the 1930s; Keiller had collected mainly in the 1970s and early 1980s, when major works were abundant and not too expensive. When part of the Penrose collection was offered to us for sale in 1995, the timing was perfect: the UK National Lottery Fund had only just started up and we were among the earliest recipients of a major grant. Gabrielle Keiller, a Scottish-born collector who married into the Keiller’s marmalade family, died that same year and bequeathed us her magnificent collection of over 200 works.

Instantly we had a world-class holding of Surrealism. We had two paintings by Salvador Dalí, five by René Magritte, three by Joan Miró, three by Yves Tanguy, two by Paul Delvaux, two early sculptures by Giacometti, more than a dozen paintings and collages by Max Ernst, and so on. In short, we had a fabulous collection dominated by men.

Launched in Paris in 1924, Surrealist art began achieving major prices at auction in the late 1980s. Miró, Dalí and Magritte had all broken through the £1 million barrier at auction by 1989. An auction database will tell you that 146 paintings by Magritte, 136 by Miró and 45 by Dalí have overshot that mark since then. All three have since gone on to break the £10 million barrier at auction, when the premium is factored in. It is a collecting area that has held up well in times

of economic uncertainty and, critically, has global appeal. It is popular and has brand recognition across different price points; and there are enough Surrealist works still out there to sustain a thriving market. A Magritte is as likely to sell to a Hong Kong collector as to someone in New York.

Museum acquisition budgets are very tight, and there are plenty of other areas we needed to focus on, so for 20 years we did nothing particular about redressing the balance. But with a bit of imagination, you can work wonders. Marion Adnams (1898–1995) is hardly a household name— she worked as a school-teacher in Derby but was a brilliant artist. In 2006 we bought her painting Aftermath, 1946, at auction at Christie’s South Kensington for under £3,000. It now hangs very comfortably next to a Dalí painting worth millions.

Other acquisition routes we make use of are Acceptance in Lieu, the Cultural Gifts Scheme (both administered by Arts Council England) and Private Treaty Sales. These are tax-effective systems for leaving, gifting or selling works to a museum. Works by Marc Chagall, Gwen John and Barbara Hepworth have come via these routes in recent years. But these systems depend on private UK owners having ‘pre-eminent’ artworks in their collections and being willing to part with them in lieu of tax. If you are a UK tax payer and own a major Leonor Fini, Frida Kahlo or Kay Sage painting, please do contact us!

Buying on the open market at the top end was beyond our means. That changed thanks to Henry and Sula Walton, world-renowned academics in the field of psychiatry, who had lived and taught in Edinburgh since the early 1960s. They had a passion for art and on their

deaths (Sula died in 2009, Henry in 2012) left us their collection and put a substantial sum of money into an independent charity with the sole aim of helping us acquire works of modern art. The Walton Fund has been well invested and operating for 10 years. We have gradually bitten into the capital but still have some funds left.

Our first acquisition attempt came in 2014, when an early painting by Dorothea Tanning (1910–2012) appeared at Christie’s in London. Buying at auction is never easy for museums. The funding is only part of the issue. Within the space of three or four weeks you have to reach agreement within your organisation, a conservator has to see the work and file a report, you need approval from the directors and trustees, you have to do your due diligence, and much more. And then you can be outbid in seconds. Estimated at £50,000–80,000, we were a couple of bids short: it went for over £300,000 with the fees.

One could sense, then, the rising interest in the work of women Surrealists—artists such as Tanning, Leonora Carrington, Leonor Fini, Kay Sage, Toyen, Valentine Hugo, Alice Rahon, Frida Kahlo and Remedios Varo. There were also some major British artists, including Ithell Colquhoun, Edith Rimmington, Eileen Agar and Grace Pailthorpe. Prices were modest, compared with their male counterparts, but the work was great and there were still a lot of major pieces in private hands. The interest can be traced back to Whitney Chadwick’s landmark book Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement, published in 1985. Back then, before auction search engines existed, works by Tanning, Carrington and Fini could be had cheaply. Kahlo’s work began to get seriously expensive in the 1990s, fueled in part by the singer Madonna, who collected her work. In 2021 a self-portrait by Kahlo went for over £25 million. But the other female Surrealists were still marginalised.

For most museums, it is easier to purchase privately rather than at auction since there is no direct competition and there is more flexibility on the timing and fundraising. In 2016, Olivier Camu, who masterminds the specialist Surrealism sales at Christie’s in London, let us know of a major painting by the Czech artist Toyen (1902–1980) which was available privately: The Message of the Forest, 1936. Measuring 160 cm. tall, it is perhaps Toyen’s most famous work. The private American owners were keen to sell to a museum and they allowed us time to get the funding together. We combined gallery funds with support from the Walton Fund and Art Fund. These acquisitions can be nerve-racking. Getting a big picture over from America and presenting it to funding bodies is never straightforward. There are complicated transport, insurance and tax issues. The sale went through just after Brexit, when sterling fell against the US dollar, but we still managed it. It’s the only painting by Toyen in a UK museum. Toyen’s stock has risen dramatically since 2016. This painting has been requested for more major museum shows than any other work in our modern collection—shows in Germany, Denmark, France and Italy. I’m not sure we could afford it now, seven years on.

Just as we were negotiating the purchase of the Toyen, a fabulous and famous picture by Leonora Carrington (1917–2011) came up for sale at an auction in New York—a portrait of her partner Max Ernst, painted in about 1939. Born in England, Carrington had lived in Paris in the late 1930s and become embedded in the Surrealist group before moving to Mexico. It would make the perfect fit for our collection, which is rich in work by Ernst, but we couldn’t go for the Toyen and the Carrington at the same time. About a year later, a chance conversation revealed that it might be for sale through Timothy Baum, the great New York art dealer. He had met many of the Surrealists, had recently

seen our collection and offered it directly to us. Importantly, he gave us time to do the fund raising and bring it over to Britain. We bought it in 2018, once more with a mix of the Walton Fund, our own NGS funding and the inestimable Art Fund. Like the Toyen, it is constantly requested for loan—to shows in London, Germany, Italy, Spain and America.

In 2019 we finally managed to get a painting by Dorothea Tanning. As so often, it was partly a matter of chance—a conversation with the gallerist Alison Jacques who let us know that Dorothea Tanning’s Foundation in New York had recently decided to release the last few major works it owned, but only to museum collections. A year later we were the proud owners of Tableau vivant, 1954, an unforgettable painting of a massive dog embracing a nude woman. Tanning had hung it above her desk for years. Once more, it was bought with a combination of funds from NGS, the Walton Fund and Art Fund. Alison Jacques generously gave us a ‘soft sculpture’ by Tanning the following year.

Shows of women Surrealists have multiplied in recent years. Manchester Art Gallery’s Angels of Anarchy, held in 2009, selected by Patricia Allmer, was a trailblazer. Since, there have been Fantastic Women at the Frankfurt Kunsthalle (2020) and Milk of Dreams at the Venice Biennale (2022). Solo museum shows of Toyen, Carrington, Eileen Agar, Remedios Varo, Meret Oppenheim and Tanning have all taken place in the last few years. The sea change has been sudden and dramatic. I know one collector who laments that curators are only interested in borrowing his works by women Surrealists. Books, academic articles and PhD dissertations have multiplied. Auctions are devoted to women artists. This is all part of a ‘rebalancing’ of museum collections, which

Far left

TOYEN (1902–1980)

The Message of the Forest, 1936

© Toyen, DACS 2023.

even in terms of 20thcentury art commonly have under 20% female representation. Museums all over the world are putting more effort and more funding into work by women. So are private collectors. Prices have risen accordingly.

The Walton Fund has not been used exclusively for work by women Surrealists—we have also acquired a version of Dalí’s Lobster Telephone, an exceptionally rare 1912 collage by Picasso and works by Yayoi Kusama, Jenny Saville and Jann Haworth. But women Surrealists have been a key part of our collecting strategy. It makes good sense: the Surrealist collection is always on show, so these acquisitions will not end up in store. Collectors and galleries are keen to sell to us because the works will hang in such stellar company. The Walton Fund became available just in time. Such has been the sea change in collecting policies across museums worldwide in the past five or six years, that it is doubtful we could acquire all these works today.

Although I am not a heritage specialist myself, my interest in digital assets was first whetted by an article in the Summer 2022 edition of this Bulletin by Racheal Muldoon, concerning the legal attributes of non-fungible tokens (NFTs or digital art). One attribute of digital assets is their legal location (situs), which can determine whether a court in England and Wales is the most appropriate forum for a claim.

and, elliptically, by HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC). However, the question has yet to be decided for tax purposes.

Bruce Fleming is a chartered tax adviser and a senior manager in the Private Client department of Buzzacott LLP, Chartered Accountants. He provides compliance and advisory services across all the taxes affecting individuals, with a particular interest in capital taxes and cases with a foreign element. His clients range across cryptoinvestors, business angels, farmers and internationally mobile trust beneficiaries. He also once doggedly helped to negotiate a valuation of a pair of Moroccan palace doors.

The situs of an asset is also a criterion for the capital taxation of UK resident but non-UK domiciled individuals. Capital gains on the disposal of non-UK situs assets are charged to UK Capital Gains Tax (CGT) only when they are remitted to the UK. Also, the non-UK situs assets of non-UK domiciled individuals are excluded property for the purpose of Inheritance Tax (IHT).

The definitions of situs for the two taxes are, however, differently aligned. For IHT purposes, the situs of a given asset category largely follows case law. By contrast, section 275 of the Taxation of Chargeable Gains Act (TCGA) 1992 consists of a closed list of asset categories each with a prescribed statutory situs, which sometimes displaces the case law rule. Digital assets, unsurprisingly, do not yet appear in this list.

The list is supplemented by a sweeper provision in section 275A (‘Location of certain intangible assets’), although the consensus is that the sweeper is probably not exhaustive (see Andy Wood, Cryptocurrency and Other Digital Assets: Tax Law and Practice, Claritax, 2022). If it is not exhaustive then the case law comes back into play to determine the CGT situs of crypto.

The situs of cryptocurrency has been addressed in a report by the UK Jurisdiction Taskforce (UKJT), in a subsequent string of recent cases involving asset recovery

The common law of situs is based on a threefold division of property under private international law: immovables (land), tangible property (chattels alias choses in possession) and intangible property (choses in action). The situs of the first two is simply where they are located. The situs of intangibles is more slippery but the starting point is Rule 129 of Dicey, Morris and Collins on the Conflict of Laws (Dicey):

Choses in action generally are situated in the country where they are properly recoverable or can be enforced.

From the outset, it has been commonly understood that the application of Rule 129 is artificial. The intangible nature of crypto-assets therefore does not in itself justify a departure from Rule 129, despite some doubts as to whether they are choses in action as traditionally conceived. The commentary in Dicey continues:

Something with no physical existence can hardly have a location in space; nevertheless the courts have evolved rules which a situs is ascribed to choses in action.

Pending a decision in the tax tribunals, or beyond, the situs of cryptocurrency has been the subject of a four-cornered discussion. The first view, what might be called the traditional view, holds that Rule 129 can still be applied successfully, even to highly decentralised digital assets. On this view, the situs is the place of enforceability, recoverability or control.

The second view, which finds (equivocal) support in recent asset recovery decisions, is that the situs is identifiable with the

domicile of the owner, the common law category of permanent home.

Thirdly, the published view of HMRC in its Cryptocurrency Manual is that that the location of the crypto-asset is identifiable with the residency of the beneficial owner (CRYPTO22600). The terse justification for residence is that it ‘gives a clear, logical, predictable and objective rule which can be easily applied’.

Fourthly and last, there is a view buried in the literature that the closed list in section 275 TCGA 1992 could, despite the novelty of crypto, still play a part but I will save the details for later.

Control: the traditional approach

Wood (section 5.5.1) flags a crucial but easily overlooked point that there is no distinction, in the absence of contrary legislation, between the situs of an asset for tax purposes and situs for the purposes of private international law (see also Wood’s article in Taxation, 3 November 2022, 18).

The authority for what we might call this principle of non-divergence is CIR v Muller & Co’s Margarine [1901] AC 217, where the House of Lords decided that unnecessary confusion would be introduced by treating the same intangible property as situated in one place for probate purposes and in another place for stamp duty purposes.

The UKJT in its Legal Statement on Cryptoassets and Smart Contracts (November 2019, paragraph 99) tentatively suggest that four factors could be particularly relevant to the law governing proprietary aspects of dealings in crypto. Three of these may not apply in every case but the factor that will generally do so is:

Whether a particular crypto-asset is controlled by particular participant

in England and Wales (because, for example, a private key is stored here).

The private key is a useful starting point but, as discussed below, there are cases where locating it may not be straightforward, or even possible.

In the recent line of asset recovery (hacking) cases, situs has been a relevant consideration to whether the court is the proper forum and, in turn, whether process can be served out of the jurisdiction.

In Osbourne v Persons Unknown and Ozone Networks [2022] EWHC 1021, the NFT case in which Racheal Muldoon was Counsel for the claimant, Judge Pelling QC relied on an earlier, unreported case in the Commercial Court, Ion Science v Persons Unknown [2020], in which it was decided that the situs of crypto is the place where the person or company who owns it is domiciled. In the absence of precedents, Ion Science drew on an analysis by Professor Andrew Dickinson in Cryptocurrencies in Public and Private Law (ed. Fox and Green, OUP, 2019).

The domicile criterion was dissected by Mrs Justice Falk in Tulip Trading Limited v Others and Bitcoin Association for BSV [2022] EWHC 667, although her remarks were obiter dicta. The claimant, TTL, had argued that situs should follow (corporate tax) residence, which was the UK. The defendants countered that it should follow domicile, i.e. the place of incorporation, which was the Seychelles.

Mrs Justice Falk stated her preference for residence over domicile, and also over the UKJT’s control criterion including storage of the private key. Intriguingly, she also found that Professor Dickinson in his commentary had not referred to domicile at all! Rather, the thrust of his argument had been an analogy between the benefits of participating

in a crypto-asset system and goodwill, an established category of intangible property.

Residence: HMRC’s approach Beyond an appeal to clarity, predictability and objectivity, HMRC has yet to publish a detailed defence of the residence of the beneficial owner as the criterion of situs. For its guidance to prevail, however, residence would, at the very least, need to be more determinate in its application than the location of the private key.

Without doubt, the location of the private key can be ambiguous. If the cryptoinvestor uses an exchange, the location of the exchange (incidentally, another of the UKJT’s four suggested factors) might not coincide with that of the key. More than one private key might be necessary to complete a transaction or the single key might be fragmented across different locations.

But it is equally possible to conceive of fragmentation scenarios where the residence of the beneficial owner may fail to yield a clear result. Joint owners could have different residence status, as could legal and beneficial owners in a trust structure. Against this background, HMRC’s appeal to clarity and predictability begins to look like special pleading.

One might add that residence is not a recognised connecting factor elsewhere in private international law and HMRC’s choice of it would (conveniently?) rescind the remittance basis for the digital asset class. It also offends the non-divergence principle in Muller’s Margarine given the unlikelihood of the High Court obediently falling into line with HMRC’s guidance.

Back to the statute?

An interesting ‘fourth way’ is Professor Dickinson’s analogy with goodwill, which would point towards the law of the place

where the participant resides or carries on business at the relevant time or, in a case of plurality, of the place with which the participant’s transaction is most closely connected (Fox and Green 5.109). Note that residence—and of the ‘participant’ rather than the beneficial owner—is just one component of this test.

This brings us back almost full circle to section 275 TCGA 1992, which provides that the situs of goodwill is ‘the place where the trade, business or profession is carried on’. In this instance, section 275 merely codifies the case law—none other than our old friend, Muller’s Margarine, where it was held that goodwill is situated where the business to which it was ‘annexed’ is situated.

So maybe crypto will find its place in the closed list of section 275 after all? Professor Dickinson concludes his article thus:

There is no need to panic and throw the existing toolbox away. The existing set of rules for regulating matters of jurisdiction and applicable law in disputes involving cryptocurrency will work perfectly well in the large majority of cases.

The existing toolbox or the Procrustean bed of residence (beneficial owner)? Place your bets.

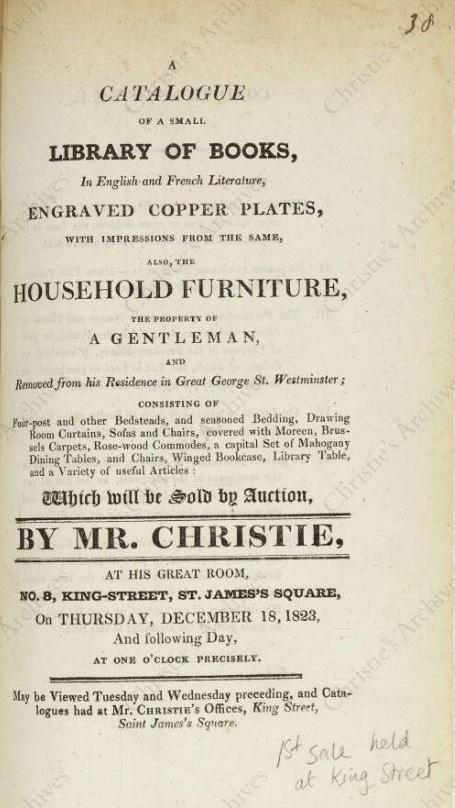

In the summer of 1823, at the age of 50, James Christie Junior (1773–1831) or ‘Jimmy Junior’ as I affectionately refer to him, moved his father’s auction rooms from 83–84 Pall Mall1 a short stepping distance to No. 8 King Street.2 The auction rooms in Pall Mall had been the founder of the firm’s home for over 30 years. James Christie (1730–1803) had lived ‘above the shop’ and took his sales in the ground and first-floor

viewing rooms. Christie’s sales were well attended and hugely popular, a venue to view lovely works of art and also a place to be seen among peers in the late 18th century. By 1823, the rooms in Pall Mall had become too small to accommodate the

grand plans that the son had for his father’s auction house. During that summer, all the paraphernalia of the firm was packaged up, including the famous mahogany rostrum designed and made by the British cabinet-maker Thomas Chippendale (1718–1779), and transported the few hundred metres from one street to another in the St James’s area of west London.

Christie Junior was familiar with the space at King Street as it had, until very recently, been known as the ‘European Museum’ run by the American auctioneer John Wilson (1789–1823), who was well-known to both Christies. The rooms were spacious, light and airy, a perfect venue for Christie Junior to hold his sales. His father had successfully held auctions of pictures and drawings, alongside ‘Household Goods’ sales and

important collection sales such as that of the property of Augusta, Princess of Wales in 1773, held a year after her death. The Etoneducated son, who was an academic and published author in the world of antiquities and classic art, wanted to move away from ‘Household’ content sales towards a world of sculpture and antiques. Alongside the pictures and drawings sales and important ‘single-owner’ auctions, the new rooms in King Street would be the perfect place for this to be achieved. After many journeys by horse-drawn ‘pantechnicon’ vans from Pall Mall to King Street, the contents of the former rooms were ready in the new location.

The inaugural sale held at Christie’s new ‘Great Rooms’ took place on Thursday, 18 December 1823 (fig. 2), a sale of ‘Library Books, copper engravings and furniture the ‘Property of a Gentleman’ totalling 244 lots, the majority of which were owned by a gentleman by the name of ‘Echalaz’. The sale realised £585-6s-6d (equivalent today to circa £34,000) and the most expensive lot, lot 96, was described as ‘… a library bookcase, wardrobe and secretaire’ which fetched £29-8s and sold to ‘Adams’.

Two hundred years later, the firm continues to hold sales, late-night viewings, exhibitions, conferences, seminars, parties and events at the firm’s London headquarters. Sales continue to be held in Christie’s Great Rooms and auctioneers still climb the steps onto the rostrum,3 clutching paperwork that contains notes for the smooth running of a sale including the reserves, commission bids and ‘Sale Room Notices’. Auctioneers hold writing implements in hand, lifting aloft a gavel (most wooden and some made of ivory) to ‘bring down the gavel’ on the successful sale of another work of art. A sales clerk, whose role is to support the auctioneer, continues to stand shoulder to shoulder, to keep an eye out for bids and make a second recording of the outcome

of the sale. Both Christie Senior and Junior could enter the saleroom in the 21st century and still recognise the theatre, energy and process of sales taken in the 18th century.

James Christie, the founder, rose to prominence in the world of 18th-century auctioneering and his son built on that success during the 19th century. The evidence of that success can be found in the Archives department, housed in the centre of the auction house at No. 8 King Street. Snuggled in the lower sub-basement, there are over 200 linear-metres of shelving in over six rooms, where evidence of the lots that have passed through our doors physically manifests itself in the form of paper-based sale catalogues, auctioneers’ books and other written, published or online sources. A centre of excellence in the ‘History of Collecting’ world, the department is the premier source of historical sale catalogues and ‘Provenance’ research in the auction house world, where one can pick up an annotated 18th-century sale catalogue and see the founder’s handwriting and notes4

2023 sees the company celebrate the 200th anniversary at King Street in a number of ways: parties and dinners for clients; staff functions later in the year and each week, within the company, a new story is released that captures an event or a colleague's story (both long gone or still here) that has taken place since 1823. Special sales will take place and the year will end in a crescendo of activity, much of which is still to be confirmed.

Yet, even though this year sees the auction house celebrate the bi-centennial anniversary of Christie’s operating out of King Street, there was a sojourn away from

4.

ArchivesLondon@christies.com

5. https://www.christies.com/auctions/christies-live-on-mobile

the headquarters for 16 years. This state of affairs took place due to the devasting events during the night of 16 April 1941 during the battering that London suffered in the Blitz of World War II. The whole of King Street was hit more than once during the war and on the morning of 17 April, Sir Alec Martin (1884–1971), Managing Director at the time, turned up to work to find a terrifying scenario in front of him, when he discovered that nearly the whole of King Street had been badly damaged after an evening of extensive bombing. All that was left of No. 8 King Street was the Portlandstone façade (fig. 3). The rest of the building had literally been razed to the ground and it was not until 25 April (some nine days later) that it was it possible for Sir Alec and his staff to begin to explore the vaults under the smashed and twisted remains of the ruined building, and examine the strong-rooms and safes. Digging machinery was needed to help shift layers of bricks and mortar and several hefty men in mufflers and caps with acetylene burners forced open the damaged strong-room doors deep underground where the warehouses were located.

Eventually, the safe doors yielded and the splendid jewels that were being stored there for a Red Cross sale were found completely unharmed. As well as the jewels, the unique collection of sales catalogues dating from 1766 were rescued in fundamentally sound condition, albeit a little stained by water. The silver warehouse fared less well, and all the pieces being held there for a silver sale scheduled on 17 April were destroyed. Every single piece had melted to a silvery coating on the shelves and floor. Thankfully, no staff lost their lives, many of whom were away at war, and no one was working late on the evening of the 16th.

Sir Alec immediately began to look for alternative rooms to hold his sales. For the next 16 years, Christie’s was afforded the

luxury of firstly, being offered Derby House by Lord Derby, then Earl Spencer kindly offered rooms at Spencer House. The firm did not get back to King Street until 1957.

Since then, the auction house has gone through numerous changes in the 21st

century. Christie's LIVE™ came on-stream in 2015, where clients could bid online for lots, and this is now also available on smartphones5 2017 saw a new CEO in Guillaume Cerutti, who remains in post in 2023. March 2020 saw the world experience a global pandemic that was a major disruptor for billions of people,

and for a good deal of time King Street saw no footfall or sales, and staff were on furlough for months on end. The auction world was turned upside down, and traditional ‘live’ sales with rooms full of activity, works of art on show, clients keen to bid and attend popular late-night viewings all went quiet. A new way of selling works of art rose from the Covid-19 ashes with online-only auctions appearing thick and fast. It was a huge learning curve for specialists to transfer their expertise online from the previous

productions of physical catalogues with print deadlines that would be sent to clients through the post. A different approach was required to prepare for online-only sales, which are available to read and pour over electronically via the Christie’s website and app. All of this was in addition to a new way of working from home for staff at all levels. Being absent from King Street highlighted how wonderful it is to return and walk up the steps under the classical Portland-stone entrance (fig. 4), designed

by the Scottish architect, John Macvicar Anderson (1835–1915), complete with urn standing proud (that thankfully remained intact after the events of April 1941) and fluttering Christie’s flag on top. For 200 years staff, clients and the ‘curiously interested’ have crossed and continue to cross that threshold to take part in the busy world of buying and selling works of art at auction. I hope to enjoy that experience for a few more years and remember—everyone is welcome.

Christie’s Heritage and Taxation Advisory Service has over 50 years of experience in undertaking offers in lieu of inheritance tax and is extremely experienced in this highly specialised field.

RUTH CORNETT, CTA TEP

Senior Director, Heritage & Taxation Advisory Service

rcornett@christies.com

+44 (0) 20 7389 2102

LUISA ROMANELLI, CTA

Associate Director, Heritage & Taxation Advisory Service

lromanelli@christies.com

+44 (0) 20 7389 2725

ZITA GIBSON

Senior Director, Head of Business Development, EMEA

zgibson@christies.com

+44 (0) 20 7389 2488

TOM LEGH, TEP

Senior Director, Estates, Appraisals & Valuations

tlegh@christies.com

+44 (0) 20 7389 2164

GEORGIE MAWBY, TEP Director, Estates, Appraisals & Valuations

gmawby@christies.com

+44 (0) 20 7389 2804

A LARGE AND IMPORTANT CHINESE BLUE AND WHITE ‘THREE FRIENDS OF WINTER’ JARDINIÈRE

Previously owned by Horace Walpole

18 ⅛ in. (46 cm.) high

21 ⅝ in. (55 cm.) diameter

Negotiated by Christie’s and accepted in lieu tax; allocated to Strawberry Hill

London auction, 6 July 2023

REMBRANDT HARMENSZ. VAN RIJN (1606–1669)

Portrait of Jan Willemsz. van der Pluym (1565-1644) and Portrait of Jaapgen Carels (1565-1640)

7 ⅞ x 6 ½ in. (19.9 x 16.5 cm.)

Estimate: £5,000,000–8,000,000

Auction | Private Sales | christies.com

CONTACT

Maya Markovic

mmarkovic@christies.com

+44 (0) 20 7389 2090