metanoia

CONTRIBUTORS

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Helen Davis

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Anna Clark

DESIGNERS

Juliette Halisky

Teagan Byrne

Margaret Zuberbueler

EDITORS

Emily Meli

John Dillon

Teagan Byrne

Kathryn Haluschak

Perpetua Phelps

Bridget Palm

ADVISORY BOARD

Lianna Youngman

Niall O’Donnell

Kathleen Sullivan, Ph.D.

Daniel McInerny, Ph.D.

Eric Jenislawski, Ph.D.

Daniel Spiotta

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

Dear Reader,

“I am the vine, you are the branches. Those who abide in me and I in them bear much fruit” (Jn 15:5).

MISSION STATEMENT:

Metanoia is a student magazine that showcases the height of Christendom College excellence in the areas of journalism, art, and design. It is meant to inspire thoughtful conversation among the student body and the broader Christendom community. Metanoia articles address issues concerning society, our immediate surroundings, and ourselves. Metanoia allows promising students the opportunity to develop their talents so that they can use contemporary media to “Restore All Things in Christ.”

Growth is necessary and yet can often be a difficult process. The full flourishing of the human person includes growth of body, mind, and soul, and these various facets of humanity intertwine in human maturation. Social interactions, whether through dancing with friends or meeting complete strangers, draw us out of ourselves while interior prayer and habits as simple as sleep invite us to consider life more deeply.

I hope that this issue of Metanoia inspires you to ponder the many opportunities for growth in even the most simple and unlooked for areas. May this issue move you to embrace growth wherever God has planted you. I pray that we all may one day reach the fullness of growth in Christ who is the true vine.

In Christ, Editor-in-Chief

Helen Davis

Anna Clark, Creative Director, and Helen Davis, Editor-in-Chief.

The Intimacy of Imaginative Prayer

by DAVID ECHANIZ '25

As Christians, we must be radically open to receiving the love of Jesus Christ. Our readiness to embrace Jesus is determined by our willingness to be vulnerable with Him. But how do we practice this radical openness? I offer a question as the starting point: How am I hiding from Jesus today?

Imagine a time in your life when you were restless, anxious, ashamed, or afraid of failure. In other words, imagine a time when you were hiding from Jesus. In these moments, we hurl questions and doubts at ourselves: “Am I good enough?” “Why can’t I do this?” “I’m such a failure.” I experienced these feelings of hopelessness during Christmas break as I found myself stuck in a cycle of sin and anxiety, and I did not know how to overcome it. The devil traps us in a corner and tries to keep us there, making us think we are unable to find a way out. I needed an escape route, and as so often happens, it came at the right time as a mission trip to Mexico.

On the first day of the trip, my group traveled to a mountain property owned by a Catholic who ran a construction business. He had built a beautiful stone chapel on his property with a magnificent high altar, where we had our first Mass. To my surprise, our chaplain’s first homily contained stories of very blunt, personal struggles and how we ought to approach Jesus with

those struggles. Never in my life had I witnessed a priest who shared his personal, traumatic experiences so openly with a congregation of strangers during a homily. But the way in which he overcame those issues resonated with me and the rest of my group. He spoke of the fundamental importance of having the courage to step out of our hiding place and reveal ourselves to Jesus. The third chapter of the Book of Genesis reveals human nature’s tendency to hide from God:

"But the Lord God called to the man, and said to him, 'Where are you?' And he said, 'I heard the sound of thee in the garden, and I was afraid, because I was naked; and I hid myself.' He said, 'Who told you that you were naked? Have you eaten of the tree of which I commanded you not to eat?' The man said, 'The woman whom thou gavest to be with me, she gave me fruit of the tree, and I ate.' Then the Lord God said to the woman, 'What is this that you have done?' The woman said, “The serpent beguiled me, and I ate.'"1

Our chaplain offered questions to reflect on in this passage: Why does God ask Adam where he is? Why does God ask Adam why he ate from the forbidden tree?

God already knew where Adam was in the garden, and He knew why he ate from the tree before asking. God asks these questions to

allow Adam the choice to be open with the Lord or to hide from Him. The response of our first parents was to deny responsibility: Adam blames Eve; Eve blames the serpent. Due to the effects of Original Sin, we hide from God in our nakedness. We hide from God out of shame for the wrongs we know we have committed. We blame others for our faults. After our

“ How often are we found in our nakedness, told that everything will be forgiven without paying any debt, and all we must do is accept it? "

chaplain reflected on this passage, he left us with an introspective question: "How often are we found in our nakedness, told that everything will be forgiven without paying any debt, and all we must do is accept it?"

This question reveals the truth of Christ’s role as our Redeemer. Jesus sacrifices Himself to pay everyone’s debt. Why, then, would I not have complete and utter confidence in God’s love for me? The trouble is the acceptance. Caving to anxiety, fear, and shame are ways that we hide from or even refuse to accept the love of our Redeemer. So, how do we go about practicing this acceptance in our daily lives?

On the third day of the trip, I asked our chaplain for spiritual direction. He guided me through an imaginative method of prayer. He asked me to close my eyes and imagine where I usually pray. My customary spot is the third row on the left side of Christendom’s Marian Chapel. I placed myself there, and he told me to imagine Jesus walking in. What does He look like? What is He wearing? The details are

essential. I pictured a very traditional image of Jesus. He was wearing a white garment down to the floor and had long hair with a beard. As I imagined Jesus walking into the chapel, Father posed the following questions: What do I say to Jesus? What does He say to me? I saw Jesus standing in the middle of the chapel, stretching His hand toward me. He said to me calmly: “I am with you.” But I did not reach out to Him right away. I stayed seated for a while, and then I eventually rose and approached Him. I had a burning anger and practically shouted: “What do I do!?” Jesus continued to look at me and did not respond. It ended there. At first, my prayer did not seem to have any resolution, but I kept reflecting and arrived at these realizations: Failing to bring our frustrations to the Lord is a form of hiding.

Jesus earnestly desires to listen to and help us carry the burdens we bring to Him.

With our chaplain’s guidance, I took a step towards

the man who freely paid the debt for all my sins creates a level of intimacy I was utterly unaware of, which leads me to accepting His love, even as I stand with the shame of my sins before Him. Imagining the humanity of Jesus dispels my fear of wanting to hide from Him. All too often, I have gone to the chapel, recited my prayers, and never actually spoken to Jesus about a single one of my problems or desires. Doing this is a primary example of hiding from Jesus when we pray. To practice confidence in God means bringing all our deepest sins, anxieties, fears, and shame to Him, along with our gratitude, joys, and blessings. Striving for the confidence to be vulnerable with God is the antithesis of hiding.

So, ask yourself today: “What am I hiding from Jesus?” Go to your favorite place to pray, close your eyes, take a few deep breaths, and imagine Jesus walking into the room. What do you want to share with Him? What does He say to you? Be attentive to

“

To practice confidence in God means bringing all our deepest sins, anxieties, fears, and shame to Him, along with our gratitude, joys, and blessings. "

THE ACTOR’S CRAFT mask vs. man

by MICHAEL MORENO '25

The art of acting can be thought of as a relationship, a relationship between the actor and the character. Like any relationship, acting requires a healthy balance between the two. The first type of actor puts on a shallow facade and in truth is only playing an exaggerated version of himself. There is little or no attempt to harmonize the craft of the actor with the character. The second type also fails to harmonize the character and actor, but for a very different reason. This second type of actor confuses his own identity with the identity of the character. The third type of actor presents a subtle understanding of the character in a way that harmonizes the identity of the actor and character without conflating the two identities.

The first type is the charismatic actor who exaggerates his own performative gifts. The actor relies upon his own charm, stoicism, or other natural

affability. He lacks depth and range, relying upon his personal charisma. Think of an actor like Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson: he is the same in every movie, but audiences don’t mind, because the Rock is funny, entertaining, and enjoyable. What he lacks in depth and range he makes up for in stage presence, elocution with dramatic delivery, gesticulation, charisma, and spectacle. This is perfectly fine for a simpler character, but it forces the character to fit and conform to the actor himself. This actor actually has great potential because of his natural gifts, but one drawback is that a charismatic man in a minor role tends to draw disproportionate attention to himself; he often overplays his part and draws attention away from the real drama. Moments that require emotional delicacy are almost impossible for an actor whose main repertoire is stoicism, scowls, or charismatic and unbothered charm. The actor pursues spectacle for his

own satisfaction, at the expense of authenticity. An actor does need stage presence, gravitas and spectacle, but these skills are insufficient for portraying the full depth of human emotion.

The second type does not maintain the proper separation between his own identity as actor and the identity of the character. The actor attempts to become the character on the level of identity. Their identities become confused with one another. This might sound like good acting, but there is an important distinction. If the actor does not maintain a grounded, disciplined view that maintains the boundary between actor and character, he inevitably attempts to merge his own identity with the character, and his own views and thoughts are confused with the mind of the character. The actor becomes blind to the larger vision offered by the drama; he becomes enraptured by his part instead of the greater whole, like a singer too obsessed with his own part and disregarding the rest of a choir singing polyphony. It would be wrong to say that this

actor’s portrayal is too deep; rather, it is too narrow and limited by a single perspective. Every role should be a learning experience as the actor explores the person of the character, and this experience informs the actor. But since the actor’s identity has been disregarded there is no real opportunity to learn from the relationship between actor and character. Instead, the actor surrenders to the identity of the character to indulge in excessive performative passion (e.g., the actor gets drunk to play a drunkard). It denies the art of the craft; it is an abandonment of self into the character that offers neither the actor nor the character real catharsis and may inhibit the catharsis of the audience. How can the actor convey the character’s true revelation, when he himself (the actor) does not have the emotional maturity or discipline to process such emotional upheaval? The emotional volatility of the actor limits the believability of his performance. The lack of maturity stunts the performance because the actor cannot articulate what he does not possess. He

cannot summon up emotions of mature and profound joy when there is only restlessness and confusion within his soul. Perhaps he can give a performance of suffering and the brokenness of human nature, but that portrayal lacks the potential for anagnorisis. While the first type does violence to the character, the second does violence to the actor.

Finally, the third type of actor maintains a relationship between character and actor that requires humility to enter into the viewpoint of someone entirely other. By necessity this is an uncomfortable process, because to step into someone else’s skin is to face the threat to one’s own preconceived notions and especially our own flaws which the character may draw out. This donning of another’s persona requires that the actor maintain a sense of self through which to view the persona or else there is no dynamic relationship. The actor ought to anchor the grand vision of the drama in reality, while also humbly contemplating and receiving the persona. The actor must have his own emotions intact and controlled in order to take on the mask of the character. enabling him to empathize and imitate the character. The actor maintains a healthy distance from which he can rationally view the actions of the character. The actor gains a greater view and understanding of the paradoxes of fate and free will, of providence, and of how a man can choose evil even when he knows it is wrong. This knowledge necessarily assists the actor’s performance because it grants him a comprehension of the character within the context of the drama. Furthermore, if he approaches this understanding with humility, the actor personally benefits from the awareness that without the grace of God he too would fail as this character.

This middle way of acting fosters emotional maturity by teaching an actor to healthily express complex and deep emotions. It fosters the ability to step back from the enslavement of one’s emotions and consider them in the light of rationality without sacrificing their validity. Acting requires that we contemplate the emotions of another. It allows us to provoke, restrain, and integrate our passions, and to grow in maturity and understanding of ourselves and others.

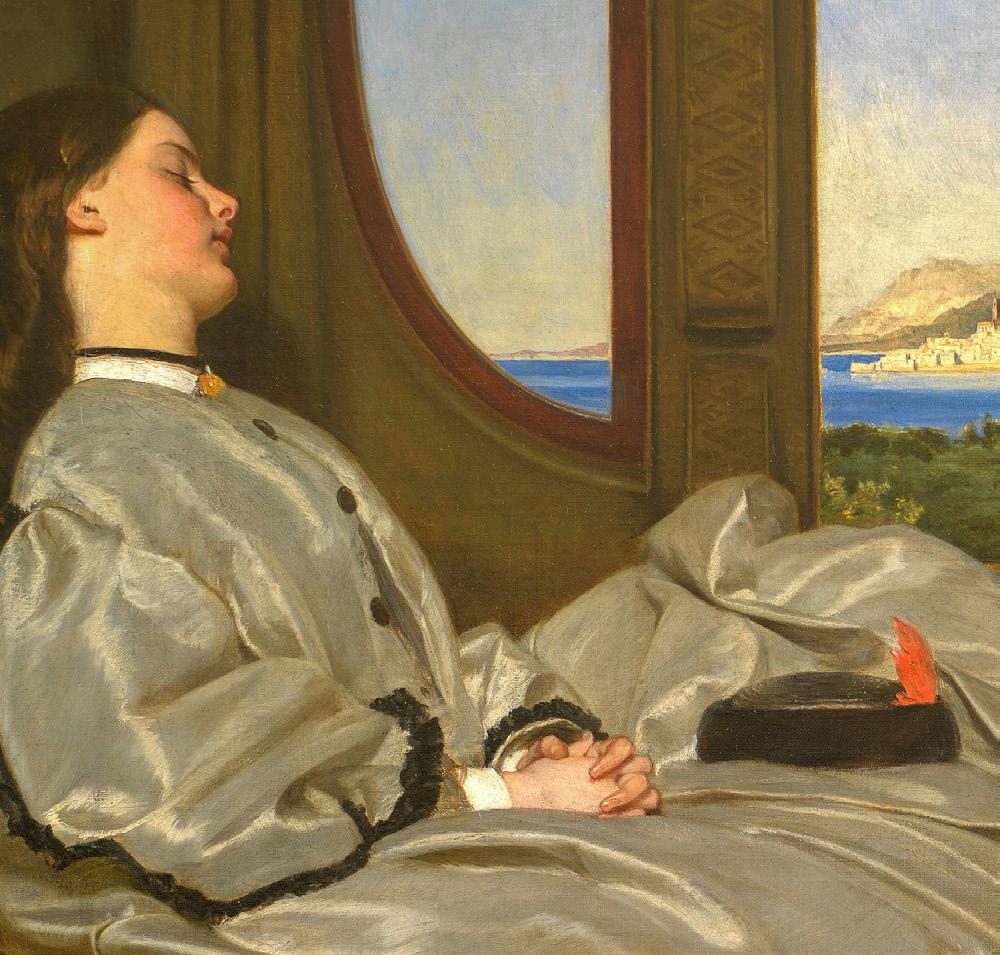

Till We Sleep The Sleep of Death

by BRENDAN SUMMERS '25

There once was a schoolgirl who was asked the question: “What is growth?” Considering the question for a second, she answered, “Growth is what happens while you sleep.” This is a good, down-to-earth answer from a bodily perspective, but I think there is a lot more to ponder here than even the girl herself realized. I believe she laid her finger on a profound answer to the much broader question: “What is growth as a full human being?” I do not mean to say that perfection of the human person occurs by taking power naps, although they certainly can be rejuvenating to man’s bodily life. Instead, I want to use man’s undisputed need for sleep as an analogy for his process of growth in other aspects of his life. Sleep is necessary for man’s mental, physical, and spiritual well-being, hence we spend around a third of our lives sleeping (although the college years tend to skew the average). According to the Sleep Foundation, sleep “serves a variety of physical and psychological functions,” including restoration, maintenance, and augmentation of a person’s ability to learn, judge, and problem-solve; regulation of emotions; physical healing; maintenance of immune system function; and, of course, growth.1 These are all essential and healthy aspects of human life without which a person would be crippled in some way.

Consider, however, that although sleep is necessary to man’s full flourishing, proper sleep must be learned as a baby. The human being has the unique ability to choose to be something other than what he is naturally ordered to be. Isn’t it odd that man must be taught to be himself? That he, even if habituated to a healthy lifestyle, must choose to be himself? Babies at a certain age will often fight the sleep they need, even though they are objectively exhausted. The baby must learn to master his own life and existence by learning to sleep. In adults, however, this learned control may be used in unhealthy ways as well. To pursue our discussion of sleep, let us consider that when a person becomes self-conscious and capable of making

informed choices, he may fight sleep when he fears for his safety in an unknown place. Alternatively, he may stay up late because he did not engage in the activities he wanted to enjoy during the day. These reactions stem from fear, in the first case, and self-fulfillment, in the second. Neither are necessarily bad in themselves, depending on the context. Yet, objectively, in each specific case, both impede the growth and healing of the person which sleep enables. These examples are not meant to condemn babies or night owls. The point is that man finds in his everyday life a strange phenomenon: a process of growth and healing which is strictly indispensable to his flourishing, yet which he has some power to control.

This discussion of man’s active control over his life and man’s dependence on passive sleep introduces a paradox. Man has the ability and need to choose his way of life, and yet his nature demands that he give up conscious control of it in sleep—for what is precisely given up in sleep is man’s choice, his control over his actions. This necessary action requires two intertwined qualities on man’s part: trust and vulnerability. A person must trust that he is safe to fall asleep in a particular place. He must risk the possibility of bodily injury during his sleep, in order that he may reap the benefits of sleep. This core paradox of human life, seen in sleep, applies to the rest of his life: that to become perfect, man must give up his control, be it of his consciousness, or of his attention, or of his very self.

Particularly relevant to this day and age, the paradox of sleep and control applies to man’s interaction with

This claim may seem strange. To apply the image, a further step must be made from the surrender of consciousness in sleep (which is biologically inevitable) to the analogous surrender of attention in our conscious life. In sleeping, we inevitably acquiesce to our biological makeup and give up consciousness, allowing growth and healing. In attending to reality as something outside of us, however, we acquiesce to reality and consequently give up a comfortable but illusory notion of self-as-in-control, allowing real growth and formation in the real world by becoming vulnerable. This sacrifice of control allows the real world to act on the person and perfect him according to its kind, which it would not be able to do if the person ignored or attempted to control it via technology. In this way, the sacrifice of attention to reality is illustrated by sleep. Like sleep, it is an “all-in” investment, which reaps a rich harvest. On the other hand, in doomscrolling or any excessive technology use, the true self becomes “sleep-deprived,” denied the restful abandonment it needs for flourishing by locking itself in an attention echo-chamber, totally in control of its little screen-and-button world.

This kind of attending to the other that is necessary for true self-growth applies peculiarly to the appreciation of mimetic art, which is itself a manmade reality. In attending to a work of art, especially a story, a person becomes immersed in the artistic reality — he must stand outside himself — in the Greek, ekstasis, ecstasy. Upon the full completion of a person’s artistic experience, be it the image of some object or the portrayal of some character, the person often experiences a kind of “waking up,” (most noticeable, in my experience, at the end of an engrossing film). I would argue that this “waking up” is inseparable from the impact which a good work of art

has in an individual’s soul. Why? To experience catharsis is to experience a purgation and rejuvenation of soul (or perhaps it is like having your mental lawn mowed); to be purged is to be passive to the action of some other; and this passive state of reception and rejuvenation recalls the notion of sleep. True catharsis is only possible when the subject’s self “falls asleep” in the work of art, awakening at the end to a cleansed appreciation for the life he is living in the present moment.

The notion of losing oneself in sleep to find oneself runs so deeply in the human condition that at the most basic spiritual level, man must not merely sleep but die to self. It’s fundamental Catholic spirituality. In dying to himself for love of another, man is enriched and, in fact, only unlocks the riches of the beloved insofar as he opens himself up to the other. It is this mystery that man experiences in communion with Christ: “for whoever would save his life will lose it; and whoever loses his life for my sake, he will save it.”2 One’s life, given up totally but intentionally, will be saved in the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. Here, the natural image of growth through sleep gives way to the mysterious supernatural image of resurrection through death. This mind-bending concept poses a dilemma; after all, while all animals die, man’s soul is indestructible, on account of his rationality. Yet he does die, and nothing resurrects by nature. This paradox is impossible to fully reconcile in the human mind—but we can come to understand it better if we can compare it to a parallel phenomenon on our natural level. And so I will leave you with this image: waking up, some peaceful morning, from a sound sleep to see the golden sunrise bathing your bedroom wall. You drink in the moment, refreshed but not ready to get up yet. And you remember it’s Sunday.

“Consider and hear me, O LORD my God: Lighten mine eyes, lest I sleep the sleep of death."

Psalm 13:3-6

Stepping into Eternity

by MONICA WINGARD '25

Imagine for a moment you are wandering down a quiet street in a city you have never been to. Above you clouds gather slowly, and before long you feel raindrops falling on your face. You duck under an arbor covered with wisteria at an entrance to a gated garden. You remain under the shelter for a moment and listen to the rain falling, watching the flowers quiver, and tasting the dampness of the air. For a moment, you are neither going to somewhere nor coming from anywhere. You do not remain in the past, nor do you advance into the future. You are simply present.

Rare and precious moments like these are spent in time yet seem to stretch beyond it. As creatures subject to the ticking clock, we desperately seek ways to escape our inevitable movement into the future. Although we long for something beyond it, man’s nature, which is composed of both a body and a soul, necessitates a life lived in time. Most of our lives we spend lamenting the loss of hours, begging for a few more seconds in that place, with that person, in that moment. However, we ought to be appreciative that time continues to pass steadily. As days stretch between you and some grand looked-forward-to event, time can’t fly fast enough. But, as hours multiply after some regretted or painful moment, we are grateful for the distance that time places between us and the experience. Man’s perspective towards time changes with every passing moment, indicating how his temporal experience alone does not fulfill the whole of his nature. In order to achieve his end, man must seek an awareness of how the eternal can be brought to mingle with the present and strive to love others with the eternal charity of God. Time, ultimately, is the opportunity given to us by God to demonstrate our desire to be united with Him in eternity.

"By nature, man has a desire for immortality. "

he is a physical creature. Subject to time and space, man is bound to three dimensions and chained between past and future. As man moves through time, faces of friends and family grow up and become old, men build and tear down, neighbors are here and then are gone. While change is intrinsic to a life in time, it is natural to only one aspect of man’s identity. Man experiences and longs for both periods of change and periods of rest because he is both bodily and spiritual. The eternity within his soul rages against the fluctuations of time and desires to be still amidst the turning world. To be in time is man’s fate, but it is not his end. For man to realize his nature both on earth and in Heaven, he requires a consciousness of eternity and an understanding of the union between time and timelessness. By nature, man has a desire for immortality. He was never made to exist purely in the confines of this temporal world. As man seeks unity with God as his end, he must somehow escape time, for God is outside of time. As Christians, we have received the fullness of revelation and understand man’s end to be eternal union with God. Even before the advent of Christ, however, man desired timelessness, for Ecclesiastes 3:11 states, “He has put eternity into man’s mind.”1 This is evident in man’s tendency to struggle against the passage of time, showing that his ultimate telos lies outside of it. To truly be alive, to discover how God intended man’s nature to be realized, means to live in a way that is oriented towards eternity. Man ought to rightly order himself to his eternal end and to attend every moment in time with this understanding. Only then can he impart the meaning achieved in his pursuit of eternity onto every action and movement and become a noticeable progression which finds both its origin and its destination in God.

Time is the measurement of change. Although having an immortal soul, man must live in time because

In a changing world, a moment of perceived timelessness is a brief anomaly. At the still point,

under the arbor hovering in timelessness, we experience the present being touched by eternity. Encountering a glimpse of our eternal destiny bestows new significance onto our lives. We are given opportunities in time to choose union with God as our end, forever. Our task is to make every moment eternal by giving it eternal value. We accomplish this by seeking to imitate the everlasting charity of God in every action in our lives. When time finally returns to its origin and collapses into eternity, our souls will bear the mark of the charity we shared with others in the time we were given. Our love contributes to our greater participation in the union we strive for with God. The time will pass anyway; it is our duty to use it well. This is the way to grow closer to the perfection of our nature: to understand the timelessness that lies beyond our grasp, discovered in brief earthly moments, and to live in time, always seeking to act with greater charity towards our others and God as our eternal end. Think back to the moment under the arbor, listening to the rainfall. Even at that point of

perceived timelessness, the clock ticks. The rain still beats, and the arbor still creaks in the breeze, but we find a serenity in the stillness of our being. In this respite, we wonder at the possibility of what life would be like if this moment never changed into some other place or became some other feeling. We wish that we could remain free from the past and the future forever. Here is the recognition of the nature of our union with God: an eternity of this same peace and stillness. Man’s end is an everlasting unity with God, and his purpose is to demonstrate through his mortal life his desire and his choice to return to his Creator. We must remain grateful for time and be conscious that it is a gift and a blessing. For we are not taunted by time’s finitude. Rather, time gives us the opportunity to participate in God’s plan for our salvation by demonstrating our wish to be united to Him. “Only through time,” as T.S. Eliot writes in his Four Quartets, “Time is conquered.”2 It is only in time that we have the freedom to choose God, and in doing so exchange a brief life of turmoil for an eternity of peace.

“It is only in time that we have the freedom to choose God."

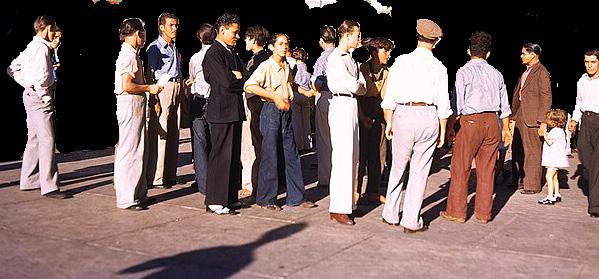

salt to the strangers

by SAM SPROULE '25

On Santa Monica Pier in Los Angeles, I met the somewhat-eccentric world traveler and vlogger Antony D’Oliveira, who was preparing to head down to Mexico. Antony was from France and had been constantly traveling since 2013, visiting 100 different countries over the past 12 years. He had seen more of humanity with its diverse cultures and walks of life than most, so I asked him what his takeaway was from his experiences. Antony encouraged me to go out of my comfort zone by interacting with people unlike myself. Here is the essence of what I remember him saying:

“People have been brainwashed with this idea of the world as a dark and unfriendly place, but as I have traveled, I have become more optimistic. After meeting people from all across the earth, many of whom were very different from me, I have come out with the conviction that the world is a friendly place and that no matter where you are, people in general have good hearts, despite all that is wrong in our world.”

Some might find it hard to believe Antony’s words, but I was not surprised by what Antony told me, as I had also had a similar experience in my, albeit much more limited, experience meeting strangers, in which I was forced to change my perspective for a more positive one. I want to argue for strangers. What do I mean? In recent times, we have begun speaking to strangers less and less and thus alienating them more and more. Humans have an unfortunate tendency

in our fallen nature to dehumanize people that are not of the same group as us. This tendency shows up in nationality, religion, social class, and political orientation among other areas. In recent years we have especially seen a dehumanization going on in politics: left wingers are irrational degenerates who want to abuse children, while right-wingers are racists and misogynists. Each side thinks the other is evil and lacks good reasons for their beliefs. When was the last time you had a serious dialogue with someone who was on the opposite side of the political spectrum? Have you ever done this? If you haven’t, you are not alone. Many people have never had such an experience. Many simply assume they would not be able to have a dialogue with the other side, and as a result they never do. This allows dehumanizing stereotypes to remain untried in our minds. If you have had a conversation with someone of the opposite worldview, you were probably, like me, surprised at how they did not line up with any of the stereotypes that you had and, shockingly, seemed like normal people. Last November, several Christendom students and I attended the Women’s March in Washington, D.C., in order to dialogue with and evangelize feminists. Many people warned me before going to stay safe, assuming that we would be in danger by going to a pro-abortion march as pro-lifers. When we arrived at the march, my friend and I went off in a pair to go talk to feminists. We both ended up having great dialogues. One woman we talked to was

so touched by the fact we were willing to listen to her opinions on abortion that she afterwards asked us to tell her the pro-life side and proceeded to ask us many questions about why we were pro-life. When we separated, she even let us know that she respected our beliefs and the fact we were 100% against abortion. Later my friend and I approached a lesbian couple. We had a friendly conversation about how things have become too polarized in the political sphere, and they admitted that the left-wing news channels such as CNN were putting out propaganda. They did not hate us for being pro-life and reciprocated the respect that we showed them, even taking a photo with us afterwards.

None of these people were irrational. They all thought they were doing the morally correct thing by being pro-abortion. Other than their political opinions, when we talked to them about neutral subjects they responded just as any Christendom student might have. They were all normal people, worthy of deep sympathy, not hatred. They just needed help. In fact, why should we think that we would not hold the same pro-abortion beliefs as some of those women if we had been raised in the same household as them? When we returned to campus afterward, all of us agreed that it had been a moving experience and our picture of humanity had grown brighter.

Last year I made it a goal of mine to talk to as many strangers as I could, and by the end of 2024 I had talked to over 1000 strangers. I cannot remember more than a small handful of these people who did not give me a sense of their interior goodness. The more people I talked to, the more my picture of humanity became more realistic. I found that everyone is just trying their best to live their life and that they want to be good. I too previously had an image of the world as a dark and forsaken place, but now I have become very optimistic.

If you walk the beaches of Oceanside, California, you might run into Fr. Wallace, a priest who spends almost every afternoon street evangelizing. How does he do

it? He simply walks around and talks to strangers. After doing this as long as he has, Father knows vast numbers of people in the community, and as he befriends them he also evangelizes them. Fr. Wallace sees talking to strangers as the number one method of evangelization. He has told me something like the following:

“People don’t talk to strangers anymore, at a time when people are lonelier and more in need of being talked to than ever before. When I can talk to someone at the pier or on the sidewalk, I can plant a seed and brighten their day. This is what it means to be the salt of the earth. Salt makes a boring dish more interesting and appetizing. Likewise, the secular world is boring and devoid of meaning, and Christianity is the most interesting thing in the world. Christians have a duty to make the world a more interesting place with their presence. When we section ourselves off into Christian communities and avoid the secular world, we are shirking our duty to be the salt of the earth. A little salt can make a big difference.”

I agree with Fr. Wallace. We have this belief that strangers will be annoyed by us or will not want to talk to us, but this is very rarely the case. In all my encounters with strangers, I have almost never been flat-out rejected by someone. Very often people are thrilled to have someone to listen to them.

But how do we talk to strangers? Admittedly this can be an intimidating prospect. I propose that it is a skill learnable by anyone. It just takes a little patience. I recommend the article and short video footnoted below as a good introduction to learning about strangers.1 If you want more, you can read Joe Keohane’s book The Power of Strangers, notably the latter half which goes into specific techniques about talking to strangers.2 Go out and do it. Start with the person next to you in line somewhere. It is worth it; people are fundamentally good and worth getting to know. Go be the salt of the earth.

"When we section ourselves off into Christian communities and avoid the secular world, we are shirking our duty to be the salt of the earth"

Not Every Savage Can Dance

by PERPETUA PHELPS '28

The conversation with the reluctant boys at my high school was the same every time:

“It’s just not my thing.”

“She wouldn’t want to dance with me.”

“Last time I was encouraged to go swing dancing, I was taught by a sixty-year-old man in baggy bejeweled pants who made it way too cringey and I’d rather not suffer any more PTSD, thanks.”

For a long time, I could not understand why someone would not want to dance. My parents had put me in a Vaganova ballet academy, and in late middle school I rapidly became obsessed with swing dancing. My favorite types of dancing had always involved a partner, and yet, for many of my high school peers, the idea of dancing one-on-one with a member of the opposite sex was uncomfortable.

To remedy this, I decided to carry on a tradition at my high school, organizing the yearly “Sock Hop” themed Swing Dance. During that time, I found that those who hesitated to dance stood on the sidelines often due to one of two reasons:

1. They did not recognize any value in dancing and so remained disinterested.

2. They thought that dancing one-on-one with someone was a recipe for awkward disaster and preferred to stick to jumping up and down in a safe circle of friends.

Those of the former group could be persuaded to get out on the dance floor once or twice. When paired with a patient dancer, they ended up enjoying

themselves immensely (even the freshman boys). To those in the latter group, persuasion was usually futile.

In our grandparents’ youth, dance was a frequent way of uniting a community and becoming better acquainted with other individuals. However, these days, the idea of socially engaging all evening with those of the opposite sex is unpleasant to many, even the well-formed students at my high school. While many still attend dances, especially during their college years, the quantity and quality of these events has declined. What once involved an entire community engaging with each other in an artistic medium that everyone understood is now only a percentage of a community and often lacks the order and harmony which our grandparents enjoyed.

How, in merely two generations, did partner dancing become so difficult and awkward?

We have become increasingly disintegrated from ourselves and from each other. Instead of face-toface interactions, we resort to emails, texts, and the occasional phone call. Instead of relying heavily

Dancing reflects the truth that we are individuals created for communion with each other.

upon our local communities, we have the luxury of being able to live more independently. Young people struggle to properly engage with each other—both one-on-one and in larger social spheres. Some of us grew up only exposed to boomers in bejeweled pants dancing in an overly sexualized fashion and are reasonably repulsed by it. Because of this, high schoolers and young adults are lost, confused, and insecure on the dance floor.

In Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice , Mr. Darcy famously claims that “every savage can dance.” 1 Our modern culture claims the same through its raunchy, beat-heavy music and media. But not every savage can dance. Dancing is more than intense physical movement to a rhythm as Mr. Darcy or contemporary culture would have us believe.

Dance is a rational expression of the good, the true, and the beautiful through intentional physical movement in harmony with music. Partner dancing is a particularly elevated form of dance because it depends upon a lead-follow structure that embodies the elegance of God’s design. Dance integrates our physicality and rationality in a beautiful, artistic manner that unites us as soul and body, lead and follow, individual and community. Dance is powerful because it is an incarnational art.

Additionally, partner dancing highlights the relationships between men and women. Matt Mordini, creator of the Theology of Dance ministry, explains that “because [partner dancing] is based around the interaction of a man and woman in a complementary fashion, [it] has the ability to penetrate the mystery of being male and female in the image and likeness of God in a way that no other form of art has.”2 Our individual bodies are expressions of our souls and expressions of God Himself. The way that we use our bodies images Him. Thus, the way that we interact with each other can also reflect Him.

Good partner dancing deepens relationships, which depend on mutual engagement, trust, and rationality. Good dancing includes harmony between the steps and the music, one’s body and one’s spirit, but most importantly harmony between the partners. Dancing reflects the truth that we are individuals created for communion with each other. Dancing also strengthens beautiful relationships and embodies a supernatural order through intentional movement. This incarnated art deeply affects our souls.

For those who struggle with partner dancing or are terrified by its complexity, I recommend the following:

1. Learn the steps. Never underestimate the power of technique. Having an clear idea of dance steps can give you a great boost of confidence. Whether it is from a YouTube tutorial or a trusted friend, take the time to learn and practice. Everyone begins with duck feet. The more that you practice, the smoother your steps will become.

2. Find and keep a rhythm. Order is the first principle of beauty. Dance with the correct rhythm. Learn what steps match with which rhythms and types of music. Most importantly, dance coordinated with your partner. Read his/her body language and move at a pace in which he/she is comfortable and suits the music. From this an orderly, beautiful dance can flow.

3. Just ask her (or accept the offer). It is one dance, not a marriage proposal. Be comfortable out of your comfort zone. Men, be gentle, thank her for the dance, and walk her back to her companions afterwards. Ladies, be gracious and let him lead. Thank him for the honor of the dance.

Dancing has bound communities together throughout all of history. Today, the art of dancing well is slowly being replaced by a cheap counterfeit. We must restore it in Christ, not only for our sakes but for the sake of our communities and future generations.

We are invited to participate in a symphonic order that is greater than our mere physicality. We have been invited to participate in the Divine Order of Creation as men and women and as a community. We have been invited to image Christ —the incarnate God, the embodied Truth. This is no easy task, for not every savage can dance.

But we are more than savages.

True Leadership and the Feminist Problem

by LUCY SPIERING '27

In our society there is a distortion of the meaning of leadership, especially regarding women. The modern feminist movement has responded to male domination—both real and falsely perceived—by encouraging female domination instead. Modern culture has prided itself on allowing either sex to have equal opportunities to control people. This attitude has only given

In the Daoist tradition, the ruler is the framework that enables the people to thrive. The Daoist writings state that this sort of leader is not the center of the stage.2 Instead, he or she is the director behind the scenes, solving hundreds of little crises, calming the panicked crew, and making the arrangements so that the cast can shine. All leaders must remember that they have been

leaders, second wave feminism urges women to aggressively pursue status and authority as their right. The strong female character is portrayed as one who needs no one’s help but instead makes the men around her look ridiculous. Despite being disparaged and deemed unneeded, men are still expected to submit enthusiastically to female leadership or be further criticized as misogynistic and insecure.

“Leading by example rather than by empty commands, Joan’s victory turned the tide of the Hundred Years War."

Those who assert that women are getting their due by finally being put into leadership positions miss a key component in the nature of authority. No one is entitled to authority. It is a gift and a responsibility from Christ, the King of Kings and true Ruler of all. Confucian tradition holds that the authority of the king is given by Heaven through the people. When the people revolt against a tyrant it is because Heaven itself has decided the king has failed in his responsibility. He loses his right to rule because he has undermined the very nature of his authority by oppressing and corrupting the people. True authority, then, cannot be seized. It is both a gift from God and from the people over whom it is exercised.

The idea of a female leader who needs no one’s help is patently false. No leader should be unable to ask for help. If a leader is completely self-sufficient, there would be no point to a political system. Humans are meant for community and hierarchy. This is because humans are naturally interdependent—they need to support each other by filling different roles. No leader can accomplish everything on her own. She cannot do everything at once, nor does she have all the talents or skills necessary for every task. She must appeal to her people to lift some of the weight from her shoulders and delegate tasks to those best suited for them.

The feminist claim that women can be leaders is not problematic. The problem, rather, is the false idea that women should be dominators. Examples such as Deborah and Joan of Arc shine forth as testaments to

true female leadership. Women can be strong leaders, not by displaying their accomplishments and putting down anyone who criticizes them, but rather, by inspiring followers through their example.

In the Old Testament, the prophetess and judge Deborah did not take over the role of

Israel’s troops herself, but she inspired Barak to fulfill his responsibilities by her own faith and conviction. She went willingly to the battle site, standing with the Israelites against the most daunting odds. Through her, God inspired His army to bravery and liberated His Chosen People.

At Orleáns, Joan of Arc did not merely give the French soldiers an uplifting speech and ride away. Rather, she risked her life by riding into battle with them, refusing to leave them to encounter the enemy alone.

She inspired the respect of the men because she shared their danger and hardship. Leading by example rather than by empty commands, Joan’s victory turned the tide of the Hundred Years War.

The modern feminist idea of leadership ruptures the relationship between a female leader

and those she leads. It causes many female leaders to act entitled, pretend to be self-sufficient, and treat men around them disrespectfully because they are tormented by deep insecurity about their worth. Women are made to believe that men will never respect them and that they can only get authority by demanding it. This leads to petty disputes and causes all questions to appear as direct challenges to authority. Such a disposition harms both the leader and those she leads. It destroys any respect she might have been given by attacking those she is meant to serve. The false female leader attempts to appear strong by appearing faultless but instead lays the blame upon her subordinates and abandons them in difficult situations. By denying her flaws, she inspires hate, fear, and distrust.

Some solution must be found to this crushing insecurity that poisons leadership. Confucius gives a simple piece of advice: “When you see someone who is worthy, concentrate upon becoming their equal; when you see someone who is unworthy, use this as an opportunity to look within yourself.”4 By recognizing the good in her subordinates, the female leader appreciates their presence and their respect. She recognizes her own failings but does not allow them to destroy her selfconfidence. While acknowledging her good qualities, she strives also to emulate the good qualities of those around her. Instead of seeing a talented subordinate as a threat, a good female leader will be grateful that

The relationship between the good leader and those who are led is one of reciprocal respect and mutual service.

such a person is willing to serve under her. When a subordinate makes a mistake, the good female leader can empathize with the person and use the experience to gain wisdom about her own flaws and strengths.

The relationship between the good leader and those who are led is one of reciprocal respect and mutual service. As soon as one views the other as a threat, the system will be torn apart by internal strife. It is especially essential that men and women in the workplace recognize their relational roles. When both sexes treat the other with trust and respect, the natural complementarity of men and women benefits the community. Men who find themselves under a female leader should realize that their support makes good leadership possible. Women who find themselves in authority positions over men should treat them with respect, honesty, and gratitude. By becoming the servant of all and leading by example, the non-coercive leader, whether male or female, influences people more than any aggressive feminist could. The good female leader’s “actions are subtle but illustrious, brief but of long-lasting consequence, narrowly confined but of wide-ranging impact.”5 She is not always seen in every success, but she is always there making it possible.

Endnotes

THE INTIMACY OF IMAGINATIVE PRAYER

1. Genesis 3:9-14 (RSV).

2. John 15:16 (RSV).

TILL WE SLEEP THE SLEEP OF DEATH

1. "Why do we need sleep?" https://www.sleepfoundation.org/how-sleep-works/why-do-we-need-sleep.

2. Luke 9:24 (RSV).

STEPPING INTO ETERNITY

1. Ecclesiastes 3:11 (RSV).

2. T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets (New York: Harcourt, 1943), “Burnt Norton,” line 90.

SALT TO THE STRANGERS

1. “Talking to Strangers: Having a Meaningful Conversation” https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=ogVLBEzn2rk and “Why talking to strangers can make us smarter” https://www.bbc. com/future/article/20221026-why-talking-tostrangers-can-make-us-happier

2. Father Wallace recommends this book. Joe Keohane is fallen-away Catholic, but his book still contains a Catholic element in it, notably that of the dignity of the human person.

NOT EVERY SAVAGE CAN DANCE

1. Jane Austen. Pride and Prejudice. (London, England: Penguin Group, Penguin Books Ltd, 1813). 52.

2. https://www.theologyofdance.org/

TRUE LEADERSHIP AND THE FEMINIST PROBLEM

1. Confucius, The Analects, 12.19

2. Laozi, The Daodejing, Chapter 17

3. Mark 9:35 (RSV).

4. Confucius, The Analects, 4.17.

5. Xunzi, Chapter 9.