China Hands

Spring

2023

Poetry

Translation Photography

Essays

Poetry

Translation Photography

Essays

Spring

Poetry

Translation Photography

Essays

Poetry

Translation Photography

Essays

Editor in Chief

Aurelia Dochnal

Managing Editor

Matt Kirschner

Editors

Roger Chenn

Amy Tang

Layout Designer

Aurelia Dochnal

3 Editor's Letter

4 translation "On the Road" by Bei Dao, trans. Jonathan Chan

5 poem "Grandma's String" by Meiting Chen

11 translation "I Walk Toward the Rain and Mist" by Bei Dao, trans. Jonathan Chan

12 translation "Colours of the Non-Essential" by Zhu Haoyue, trans. Jessica Yu

15 article "Flying Tigers" by Matt Kirschner

18 review "XIAOWU: The Cacophony of Alienation" by Aurelia Dochnal

19 translation "To the Tune of ‘Dotting Red Lips" by Li Qingzhao, trans. Jonathan Chan

21 article "Approaches to Erudition: ‘wen’ in Song China and ‘Adab’ in the Abbasid Caliphate" by Jonathan Chan

23 article "Paid to Cry: Chinese Professional Mourners at Funeral" by Ziling Chen

28 translation "The Letters of Wang Xiaobo: A New Translation" by Xinning Shao

34 translation "Love" by Eileen Chang, trans. Isabelle Qian

Cover photograph: Meiting Chen

Back cover photograph: Aurelia Dochnal

I eagerly welcome you into this new issue of China

Hands, filled with poetry, essays, photography, and more, all in some way related to China. Our hope here is always to inspire cross-border engagement and contribute to thoughtful intercultural exchange. Now more than ever it is time to bring the revolutionary power of art into our lives and our understanding of the world.

Yours,

Aurelia Dochnal (Editor in Chief)july. an abandoned quarry. a slanting wind and fifty paper sparrowhawks pass by. the people kneeling toward the ocean give up a thousand-year war.

i adjust for the time difference and through my life i pass.

shouts of freedom, the sound of golden sand comes from the water. restless infants kick the abdomen, their mouths full of tobacco, their mother’s heads trapped in thick fog.

i adjust for the time difference and through my life i pass.

this city is migrating. hotels, big and small, line up against the rails. straw hats rotate on the heads of their guests. somehow, others begin to shoot.

i adjust for the time difference and through my life i pass.

bees form into groups, swarms chasing wanderers, drifting flower gardens, singers, and the blind, doubled brightness used to stir the sky,

i adjust for the time difference and through my life i pass.

covering a map of death, a destination is a drop of blood. lucid stones are underneath my feet. i have already forgotten about them.

馆排在铁轨上 游客们的草帽转动 有⼈向他们射击 我调整时差 于是我穿过我的 ⽣ 蜜蜂成群结队 追逐着流浪者飘移的花园 歌⼿与盲⼈ ⽤双重光辉激荡夜空 我调整时差 于是我穿过我的 ⽣ 覆盖死亡的地图上 终点是 滴⾎ 清醒的⽯头在我的脚下 被我遗忘

Grandma used to dance the waltz in the park every morning. Her floral pleated skirt swirling and swirling

Like strings of unending ripples. She had a whole closet of beautiful clothes: Leather vest, corduroy jacket, long, delicious gowns of silk and velvet, Coats with crazy patterns that even mother didn’t dare to wear in public, But grandma would, after dancing, like a queen.

Strolling in the wet market with her little grocery cart, I could still count what was inside:

Smoked fish and sausage, snow peas, lotus roots, sweet potato veins, freshlyfried meatballs

She would teach me how to bargain, how to be sharp-eyed, how to make the vendor add a bundle of scallions for free.

Grandmas and grandpas mushroomed the streets with toddlers in their arms,

? Which one of your grandchildren is she?” They would ask

The one in America."

America.

What a foreign name. A land of opportunities?

But you have no one to take care of you over there.

Grandma cried one afternoon before I left for college.

We can never stretch our arms far enough to help you

When you are in trouble.

When you need help.

When you feel lonely.

When you are stressed

When you miss home.

When you miss us.

She took my hand with both hands.

How much I wish time would never move forward.

So you will never grow up, and we will never grow old.

How wonderful it would be that we forever stay this way.

A little girl sitting on a little stool in the backyard

waiting for her breakfast

Cicadas singing summer in sycamore trees

I believe that each time one travels far from home

A layer of callous grows around the heart

A slight nod of the head before disappearing from the security checkpoint

A smile of reassurance that I would eat well and sleep well

Eye masks, neck pillow, slippers, a few snacks,

An international student is a seasoned traveler, proficient at bidding farewells

An apprentice of long-distance relationships.

You coach yourself to be tough-looking, to sharpen your accent

To say “small de-caf iced latte with almond milk” and “a chicken bowl to go”

To pretend you have watched that childhood TV show someone mentioned;

To cook for Chinese New Year while finishing up a paper

To decide everything for yourself

You start to call your parents less and less often because they no longer understand your thoughts

To experience reverse cultural shock when going back home

To slowly realize that there are fewer and fewer friends in your hometown

To anxiously debate if you should get a job in the U.S or in China.

And you stay for one more year. Then another year. Then another year after that. Years would pass with a blink of an eye from the moment you first landed.

At some point, you start to wonder what difference does it make

To say that I grew up in China

Vs. I am from China

To say that I have studied in the U.S when I was 15

Vs. I have come to the U.S when I was 15

Is an international student also part of the diaspora?

The line between two homes, between being a student and an immigrant has become so thin

That you can simply cross if you will it.

But somehow that line has also always been a long, long string Grandma knitted it every time before I left for the airport

As I laid my hands on my suitcase, She gently tied it around my wrist

And as the cab moved away from her, she tossed and yanked it

Telling me that she would hold its other end as tightly as she could for as long as she could

And I flew like a kite, 7477 miles away.

Last month Grandma let go of the string.

Was I supposed to feel grief?

I only knew that actually I was falling

Spiraling down like a broken kite

How do you mourn when you are 7477 miles away?

When mother told me that she cleared out most of grandma’s closet, I cried for the first time since her death.

Inside my family we never say “I love you”

But I know grandma meant exactly that

And perhaps so much more

The way she looked at me

When she laid out piles of skirts she had bought and saved just for me

The way she watched me trying them on in front of the mirror

One by one

Before dinner was ready. ■

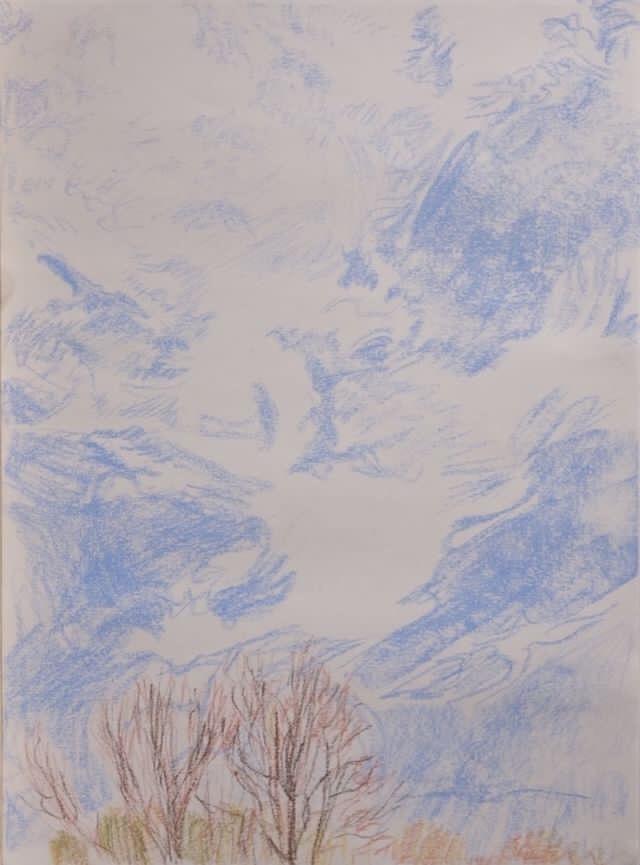

dark clouds are a time of ascent and landing. the birds scatter in all directions. a blue slash whips the sombre forest, as if it whips a thousand canes, whips a thousand hearts of the old. my heart, where is your home, where is your cover?

the leaves and grass sink in the stupor of their weeping, the daisy imitates what it means to awaken. the wind says to the rain: you were once water, you must return to water. and so, the rain weakens at its newest edge, resolving into a stream, pouring, entering a river. the noiseless lightning upon the ice, causes the two sinking coasts to rumble as they retreat, again, how sudden: they begin to close up.

Bei Dao 北岛 (b. 1949) is the pen name of Zhao Zhenkai 趙振開, a major writer and poet of modern China. His poems first appeared in Today 今天, a magazine he co-founded. His works have been translated into over thirty languages, including English translations of his poems in Unlock (2000) and Landscape Over Zero (1996); essays in Blue House (2000) and Midnight’s Gate (2005). Bei Dao was elected an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and has received a number of literary awards. He is currently Professor of Humanities in the Centre for East Asian Studies at The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Jonathan Chan 陈超义 is a writer, editor, and translator of poems and essays. Born in New York to a Malaysian father and South Korean mother, he was raised in Singapore and educated at Cambridge and Yale Universities. He is the author of the poetry collection going home (Landmark, 2022). He has an abiding interest in faith, identity, and creative expression. His translations of poems have been featured or forthcoming in Asymptote Journal, Journal of Practice, Research and Tangential Activities (PR&TA) and SingPoWriMo Magazine. More of his writing can be found at jonbcy.wordpress.com

translated by jessica yu, yale university

translated by jessica yu, yale university

internships&appointments&TOEFLcountas important,right?

butwhataboutcatchingshyglimpses ofacloudlingeringatdawn? ortwirlingthroughthestreetslaughing ‘causeyousnaggedthelastbagofchestnuts?

&whatabouthidingunderatree,coldraindrops kissingyourhair?ormeltingonabus, intothearmsofyourcrushascity skylinesblurbehindyou?

whatifthosecloudysnapshotsturninto all-timeclassics?whatifyouofferchestnutstoa hungrystranger-in-need?whatificyraindrops crystallizeintoapoet'sinspiration? whatiftheyaretheone?

thepandemichassimmeredanxiety overlossofthegrand,thenecessary.

butwhatislifeifnotcolours:akaleidoscope oftiny,non-essentialmoments?

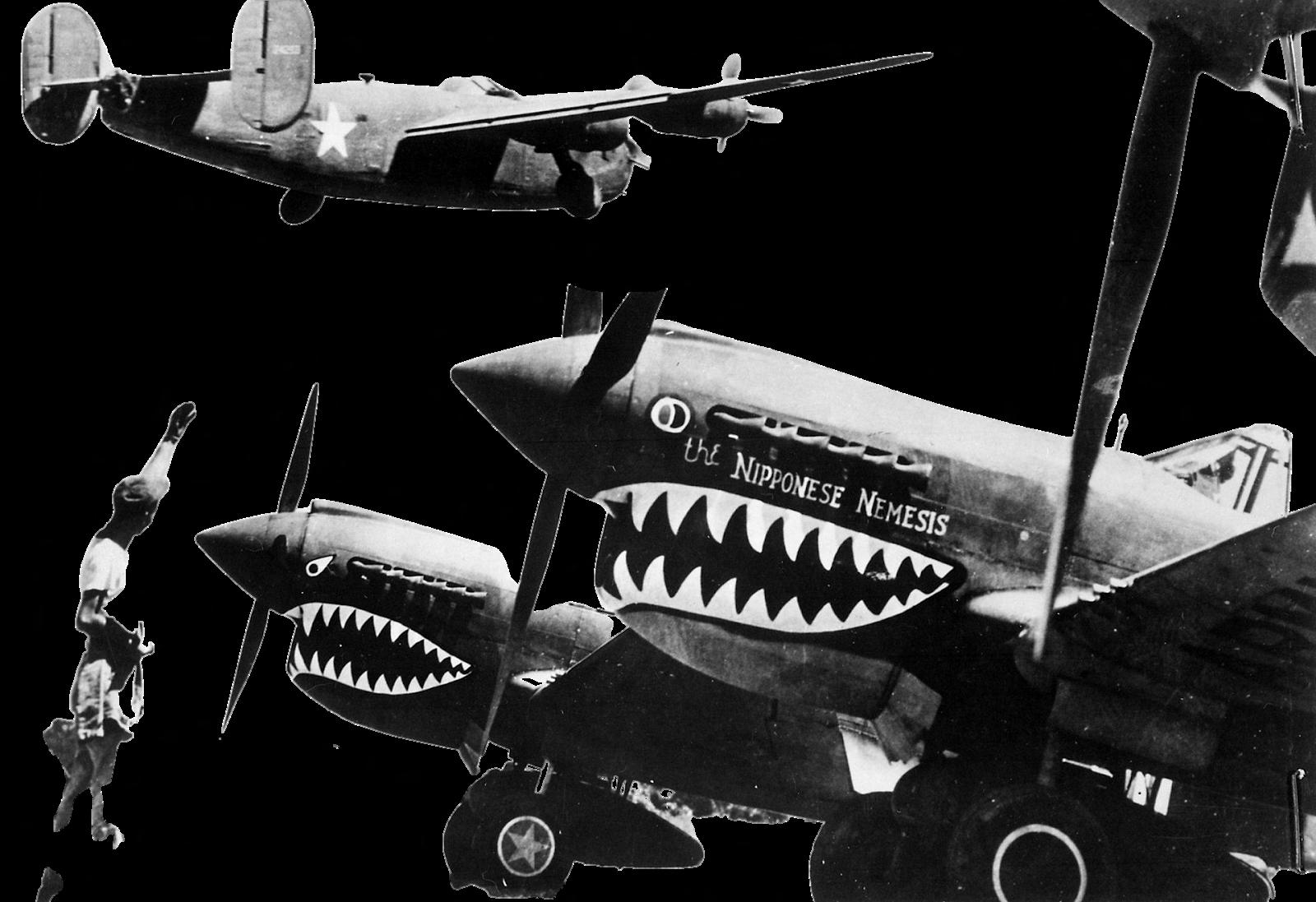

Liu Zhengde was seven years old when Japanese soldiers invaded his home in Wuhan, China in 1938. Leaving their belongings behind, Zhengde and his family fled Wuhan for Chongqing—the provisional wartime capital of China. Zhengde’s father worked to support his three children, wife, sister, brother, sister-in-law, mother, and aunt. Together they lived in a small, cramped house and ate a diet of rice and porridge. Every day Japanese planes bombed the city. Whenever the city’s sirens sounded, Zhengde and his family would run outside to hide in ditches. The bombings killed over 10,000 Chinese in Chongqing, most of them civilians.

This routine continued until 1941, when a group of about 100 American pilots recruited by President Franklin Roosevelt flew to China to help defend the country against Japanese invaders. They called themselves the Flying Tigers, a name derived from their aircrafts’ distinctive shark’s mouth paint scheme.

OnedayZhengde watchedandcheeredastheFlyingTigers shotdownaJapanesebomber.TheFlying Tigers shot down 299 Japanese aircraft and only lost 12 of their own. They helped stop the advance of the Japanese in China. When Japan surrendered in 1945, Chongqing hosted a celebration, duringwhichZhengdeshookhandswith theFlyingTigersandevenplayedsoccer with them. Zhengde developed a strong appreciation of peaceful relations between different cultures and peoples, and an especially strong sense of gratitude toward the U.S. Zhengde was mygrandfather.

There aren’t many people like Zhengde left to tell their stories. If there were, maybe tensions wouldn’t be so high betweenChinaandtheU.S.Eightyyears after the Flying Tigers helped defend China from the Japanese invasion, the U.S. and China find themselves on opposing sides of a brewing cold war. How did relations deteriorate? After China successfully defended itself from Japan, Mao Zedong and the Chinese CommunistParty(CCP)defeatedChiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang in the Chinese Civil War in 1949, leading to a rapid decline in Sino-U.S. relations— especially as the U.S. entered the Cold War with the USSR. The U.S. saw communism as a threat to freedom and democracy around the world. When the Korean War broke out in 1950, the People’sRepublicofChina(PRC)andthe U.S.foughtonopposingsides.Whenthe PRC bombed islands controlled by the Republic of China (ROC) in Taiwan, the U.S.activelyintervenedonbehalfofthe ROC. It wasn’t until 1979 that the U.S. established relations with and formally recognized the PRC as the sole governmentofChina.

The U.S. and China developed a strong economic relationship during the 1980s. AfterDengXiaoping—paramountleader

of the CCP following Mao Zedong’s death—opened China’s economy to foreign trade and investment, the U.S. and Chinabecame more and more dependent on one another.TheU.S.benefitedfromChina’s largesupplyoflow-costlaborandChina benefited from increased foreign investment,propellingthecountriesinto a marriage of convenience. The U.S. attitudetowardChinagrewoptimistic,as the country seemed on a path to becoming a democratic and capitalist country. This optimism proved to be short-lived.

SinceXiJinpingwaselectedpresidentof thePRCin2013,thecountryhasshown no signs of abandoning its communist roots, nor of embracing democratic institutions. Tensions have risen to new heights as the U.S. and China threaten each other’s international influence. On June 15, 2018, the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) released a list of $34 billion worth of Chinese imported products with “industrially significant technology” that would be subject to a 25% import tariff. The tariffs were a response to unfair trade practices by Chinese companies, including allegations of intellectual property theft. China responded immediately with tariffs on exports critical to America’s agricultural sector, including soybeans. Thus began a backand-forth economic battle involving tariffsandtradeembargos.Thetradewar quickly morphed into a battle for leadership in core technologies like 5G, artificial intelligence (AI), and semiconductors. When COVID-19 emerged, the U.S. politicized the pandemicwiththeTrumpadministration accusing China of spreading the virus, furtherescalatingtensions.Allthewhile, China grew increasingly ambitious in its attemptstoattackTaiwanforthesakeof “Chinese reunification”—as well as to controlTaiwan’sdominanceinsemicon–

–ductor production, which is key to AI development and the development of virtuallyallnewtechnology.

U.S.SpeakeroftheHouseNancyPelosi’s visittoTaiwanatthebeginningofAugust may just be the spark to set off real fireworks. The U.S. doesn’t officially recognize Taiwan as an independent countryundertheOneChinapolicybut has repeatedly vowed to help Taiwan protect itself against potential attacks. While attempting to prevent Chinese infringements against Taiwanese freedom and democracy, Pelosi may haveinadvertentlygivenChinaanexcuse to significantly ramp up their military presence surrounding Taiwan. After Pelosi’s visit, China reaffirmed its threat to use military force to bring Taiwan under its control, initiating a bombardment of missile firings into Taiwanese waters and airspace by Chinese warships and fighter planes. At this rate, the U.S. and China are on a collisioncourse.

AtatimeofrisingdivisioninU.S.politics, anti-Chinasentimentseemstobetheone thing gaining bipartisan support. AntiChina rhetoric and scapegoating of Chinese people for the spread of the COVID-19virushasledtoattacksagainst AsianAmericansintheU.S.andasharp increase in hate crimes. Hundreds of Chinese-American scientists were investigated solely because they are Chinese and had research collaborations with China. To add salt to the wounds, then-president Donald Trump joked aboutthe“kungflu,”furtherexacerbating tensions.ButChinaiscomplicitinedging the U.S. and China closer to conflict. In China, where there is virtually no freedom of the press, state media spews negativeviewsabouttheU.S.Duringthe COVID-19outbreakChinesestatemedia propagated false narratives about COVID-19originatingfromFortDetrick —a bioresearch lab 60 miles from Washington D.C.—and being brought to WuhanbymembersoftheU.S.military. Ifwarweretobreakout,bothsideswould bear responsibility for inflammatory rhetoricleadinguptothatpoint.

My grandfather Zhengde unfortunately isn’taroundanymoretotellstoriesabout theuniquehistoryhewitnessedbetween the U.S. and China. If we can gain perspective on relations between China and the U.S. by remembering moments of solidarity and cooperation, perhaps bothcountrieswillbemorelikelytofind common ground. My parents recently visited the WWII Pacific Memorial Hall MuseuminSanFrancisco’sChinatown,a small two room museum that highlights the heroism of Chinese and American soldiers during the war, with a special exhibit dedicated to the Flying Tigers. Themuseumismodest,andmyparents were the only visitors at the time. But I believethatit’ssmallreminderslikethis museum that play a large role in continuing my grandfather’s legacy of sharing positive stories and giving hope tothefutureofChina-U.S.relations. ■

As the camera aimlessly ambles around a dilapidated city, disjointed layers of popular tunes hang in the air. A karaoke bar; a locally-made stereo, one of the best on the market, blasts in the street; a lighter hums an electric rendition of “Für Elise.” The music in Jia Zhangke’s first feature film, Xiao Wu (1997), or Pickpocket as it’s known in English, follows the solitary wandering of the movie’s unhappy protagonist – who secretly loves to sing. Xiao Wu is haunted by his loneliness: he is alienated from his former business partner, his family, and even his short-lived romantic flame, Meimei, is swept away by dark-suited businessmen in a fancy car before he can say goodbye. The beep of his pager while he’s locked up in handcuffs at the tiny police station calls out to him from a cabinet – Meimei, his beloved karaoke waitress, is wishing him luck in his life. Each sound in this movie is an amplification of the alienation brought on by Fenyang’s rapid modernization. While Xiao Wu stalks around the city, director Jia Zhangke’s hometown, his best friend’s shop is being demolished. Cigarettes are constantly being lit, smoked, and discussed – their price, their origin, their quality. Cigarettes are how Xiao Wu’s former business partner made his fortune, and they are a mark of modern China, their stale smoke hanging in the air of each shot.

Watching Xiao Wu feels like watching a mournful farewell to its titular character, a last glimpse of his vagrant life before he’s again thrown into jail. There is no place for people like him, people who just can’t get it together, who can’t work the system for their own gain, in this new China, blue-tinted and ruthless. This is 1997 – China has opened up economically –there are opportunities to make it big, regardless of your chushen (family class background). Xiao Wu’s own family are peasants; his stooped and chain-smoking father sometimes tills the fields himself. Xiao Wu’s return to and subsequent expulsion from the countryside when he visits his family seems to be a way of saying: There is no room for you here. Pickpockets, who by the nature of their profession live as leeches on urban life, belong to some strange liminal space, idle in the busy city and worthless in the open country. This is Xiao Wu’s tragedy: he belongs nowhere, he belongs to no one. As the public loudspeakers in the center of Fenyang loop announcements of new official government policies, as the world around him transforms and warps into a series of sounds and flashing images, Xiao Wu is not quick or cruel enough to keep up with his surroundings. This mesmerizing film allows viewers to teeter on the cusp of the new millennium alongside Xiao Wu and experience the dread of the uncontrollable, unknowable impending future in a life adrift.

a review by aurelia dochnal

a review by aurelia dochnal

leaping down from a leather swing, she gets up, languid as she straightens her clothes, her fingers graceful, delicate. the dew has accumulated thick, the blossoms are emaciated and thin. thin sweat soaks her dress through.

upon seeing a guest’s arrival in her stockings, her gold hairpin slips. with shame, so bashful, she flees. stopping at the door, she turns her head, and smells the green plum in her grasp.

Li Qingzhao (1084-1155)

translated by Jonathan Chan

Li Qingzhao 李清照 (1084-c. 1155) was a Chinese poet and essayist during the Song Dynasty. She is considered one of the greatest poets in Chinese history. At the age of seventeen, she seems to have written two lengthy poems on the historical theme of a seventh-century stone inscription commemorating the “restoration” of the Tang dynasty upon the imperial defeat of the An Lushan 安祿⼭ rebellion. By the time she was eighteen, she had begun writing lyrics that displayed her innocence, her mental sharpness, and her love of nature. Her poetry was already known within elite circles before her marriage to Zhao Mingcheng. Upon the invasion of the Northern Song Capital by the Jurchens in 1127, Li and her husband fled South to Nanjing and her husband died of typhoid fever two years later. She was remarried to Zhang Ruzhou, but the marriage ended disastrously. Li eventually settled in Hangzhou, where her poetry became more focused on nostalgia for her husband and her hometown. Everything of hers that survives today survives because it was quoted or anthologized somewhere in the decades and centuries after her death.

InthedisparatecontextsoftheSongDynasty(960-1279) and the Abbasid Caliphate (750-1517), erudition and literary skill emerged as characteristics that were regarded as desirable and vital to the perpetuity of both geopolitical entities. As is visible not only with the example of the Islamic geographer Ibn Khurradadhbih but also the Song historian and politician Zhao Rukuo, thecapacityforrecordingandcompositionwascrucialas aformofknowledgeacquisition,whetherwithregardto geographic locales, ethnographic studies, or itemised inventoriesforbureaucraticuse.

These figures emerged from contexts that extolled erudition.Etymologically,theword‘erudite’arrivestous in English with roots in the Latin erudire, meaning to instruct or train, which itself is formulated against the word rudis, meaning rude or untrained.[i] The most proximateterminologywecanexamineintheSongand Abbasid contexts are wen ⽂ and adab respectively in ChineseandArabic.

In Song China (960-1279), wen was central to the intellectual culture of the literati. It referred to ‘refined, civil, or cultured qualities’ as well as the arts associated withit.[ii] In politics the early Song aimed to establish a civil (wen) order after a long period where military interests were paramount. It was held that its sociopoliticalordershouldapproximatethegreatestmodelsof thepast–theHanandTangempiresorantiquity.[iii] To accomplish this, it was thought necessary to have as officials those most knowledgeable and adept at using past forms, those schooled in the great texts of Chinese tradition.[iv] Hence, the most prestigious examination required skill in poetic composition: the ability to tie togetherreferencestopasttextsaroundgiventhemesand fitthemintheregulatedformofTangprosody.[v] This wasfollowedbyaproseessayonathemeand“treatises” on policy or scholarship.[vi] The best candidates drew uponthetextualtraditiontoconstructformallycoherent balanced compositions, just as the Song sought to unify and organize the realm into a coherent political order drawingonpastmodels.[vii] AsWangGungwuargues, "To the emperor-tianxia, it was enough that the wentexts supported central power and shaped the system’s collectivememory.Theyweremostusefulastheshi(史)

records of every dynasty. This shi-history went beyond mere utility. In its totality, it provided continuity for all ofChina’spast."[viii]

Overtime, wen accumulatedseverallevelsofmeaning.It was the manifest aspect of the cosmic, the forms of human society, the cumulative textual tradition that stemmed from antiquity, the complex of political and social values and normative cultural forms associated with sage-kings, and individual literary accomplishment. [ix] To govern through wen was to govern in a civil fashion, relying on proper forms, communication, and education rather than the coercion and violence of the previouscentury.[x] Officialswhoacquired wen could be trustedtorealizetheideaofacivilorderinpractice. Wen was regarded as crucial to the success of the Song dynasty, being described as the ‘pre-eminent value for theage.’ [xi]

Contrastingly, the reformer Su Shi contended in 1059 that wen of real value was the spontaneous composition of men, external expressions of what the individual had accumulated within.[xii] These were not calculated to satisfy existing standards, yet had value and could serve asmodelsforothers.[xiii] Ashedescribes: "Mywenislikeaten-thousand-gallonflow.Itdoes notcarewhere,itcancomeforthfromanyplace.Onthe flatland spreading and rolling, even a thousand miles a daygiveitnodifficulty."[xiv]

While wen concerned itself with ethical conduct and social relations, adab in the Abbasid context in its oldest sense, may be regarded as a synonym of sunna. The sunna was the sense of “habit, hereditary norm of conduct, or custom” derived from ancestors and in particular,theProphetMuhammed.[xv]

However, by the beginning of the Abbasid epoch (7501258), the concept ended up losing its humanistic acceptation and became the equivalent of the Latin urbanitas, the civility, courtesy, and refinement of the cities in contrast to beduin uncouthness.[xvi] It took on themeaningof“theknowledgenecessaryforgivensocial functions." Thus one could speak of an adab culture required for holding the office of secretary or vizier, the bureaucraticmanagerswhodependedoncaliphal

authority.[xvii] In contrast to Europe, India, and East Asia,theMuslimcommunitylookedtocreativemoments experiencedinanewlanguageandwithinanewreligious allegiance – the older Irano-Semitic traditions were no longer studied and the religious alienness of the Greek, Syriac, and Pahlavi traditions prevented their classics from achieving cultural authority.[xviii] As a comprehensive synthesis of high culture, adab gave a place for Shari’ah-minded learning and honoured the ulama, the transmitters of religious knowledge in Islam. [xix] By the time of the caliph al-Ma’mun in the ninth century, these patterns were given a classical form accepted throughout the Muslim domains. This new cultural tradition was crucial in assuring the prestige of the government and with it, the stability of the whole society.[xx]

Adab also became restricted to the rhetorical sphere of "belles-lettres": this included Arabic poetry and prose, maximsandproverbs,thegenealogyandtraditionofthe pre-Islamic Arabs, and oratory. It also included the correspondingsciences:rhetoric,grammar,lexicography, and metrics.[xxi] Al-Jahiz is an exemplar of this, as his longest surviving works display philological erudition, providingastorehouseofinformationthataclerkwould need to write elegantly, knowledgably, and exactly.[xxii] Another example is al-Masudi, who wrote on jurisprudence, comparative religion, political theory, medicine,andhistory.However,thereisnoevidencethat he ever occupied a government post, reflecting the culturalcurrentsemanatingfromcourtlycontexts.[xxiii]

A central position in adab was held by Arabic literature, especially poetry and rhymed prose. In the Abbasid context, the composition of shi’r poetry was the consummate skill of the adīb.[xxiv] Shi’r poetry was recitedasagracefulexpressionofsentimentscommonto a gathered audience. The form had to be held to exactly and the substance familiar enough to allow each listener tonotehowwellthethoughthadbeenput,withoutbeing distracted by the implications of the thought itself. [xxv] Thesecompositionsformedthecommonbackgroundof literary culture shared among those who maintained the normsofIslamicsociety.[xxvi]

Interestingly, exposure to external pressures means that the adīb broadened his range of interest to include Iranianandnarrativetraditions,Indianfables,andGreek philosophy, ethics, and economics.[xxvii] During this period the Muslim world became an intellectual centre for science, philosophy, medicine and education as the Abbasids established the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, where Muslim and non-Muslim scholars sought to translate classic works of antiquity from Rome, China, Greece, and elsewhere into Arabic and Persian and later intoTurkish,HebrewandLatin.[xxviii] In fact, Hodgson argues that Aristotle’s gentlemanly ideal in Arabic adaptationwasprominentamongtheadībs. [xxix]

To conclude, where the cultivation of erudition is concerned in Song China and the Abbasid Caliphate, erudition was seen as vital not only for its own sake, howeverromanticisedsuchanotionmaybe,butalsofor the utilitarian benefits provided in service to regimes presiding over vast tracts of land across linguistic and ethnic groups. We have seen how the Liao and Jin adopted the Chinese style of imperial examinations as well as the porous relationship between what we may nowregardasliterarywritingandIslamicgeographies.

The implications of this, in part, may lead to reflection on present systems of higher education in the humanities, bearing in mind the particular lineage that universities in the Western tradition draw upon: medieval scholasticism and Renaissance humanism. This may prompt consideration of how such systems of education are and are not enmeshed with projects of moralcultivationandutilitarianfunction.

Endnotes

[i] Oxford English Dictionary (Oxford: Oxford University Press,2020),s.v.“erudition,”accessedOctober22,2021.

[ii] A Student’s Dictionary of Classical and Medieval Chinese Online(Chinese–English),ed.PaulW.Kroll(Leiden:Brill, 2017),s.v.“⽂ wén.”

[iii] Kidder Smith Jr., Peter K. Bol, Joseph A. Adler, and Don J. Wyatt, Sung Dynasty Uses of the I Ching (Princeton: PrincetonUniversityPress,1990),58.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] PeterK.Bol, Neo-Confucianism in History (Cambridge: HarvardUniversityPress,2008),49;JinZhongshu ⾦中樞, “BeiSongkejuzhiduyanjiu,I 北宋科舉制度研究 I”inSong shiyanjiuji 宋史研究集,vol.11(Taibei:Guolibianyiguan, 1979),2-12.

[vii] SmithJr.,Bol,Adler,andWyatt, SungDynastyUsesof theIChing,58.

[viii] Wang Gungwu, “Professor Wang Gungwu’s Tang Prize 2021 lecture: China’s road from wen to shi,” ThinkChina,20November2021.

[ix] Bol, Neo-ConfucianisminHistory,51.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Xu Xuan 徐 鉉 , Xu Qisheng ji 徐 騎 省 集 , Guoxue jiben congshu(Changsha:Shangwuyinshuguan,1939),23.230.

[xii] Su Che, “Nan hsing ch’ien chi hsu” in Su Tung-p’o chi(Kuo-hsuehchi-pents’ung-shu),2.5.24-35.

[xiii] Peter K. Bol, “Redefinition of Literati Learning,” in Neo-Confucian Education: The Formative Stage, ed. Wm. Theodore de Bary and John W. Chaffee (University of CaliforniaPress:Berkeley,1989),172.

[xiv] Su Shih, “Tzu p’ing wen,” in Tung-p’o t’i pa (TSCC ed.),1:15.

[

xv] Francesco Gabrieli, “Adab” in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, ed. P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs (Leiden: Brill,2012),accessedOctober22,2021.

[xvi] Gabrieli,“Adab”.

[xvii] Gabrieli, “Adab”; Marshall G. S. Hodgson, The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization, Volume One: The Classical Age of Islam (Chicago:UniversityofChicagoPress,1974),452.

[xviii] Hodgson, TheVentureofIslam,445-447.

[xix] Ibid,445.

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] Gabrieli,“Adab”.

[xxii] Hodgson, TheVentureofIslam,467.

[xxiii] Paul Lunde and Caroline Stone, “Introduction” in Masudi, The Meadows of Gold: The Abbasids, trans. Paul Lunde and Caroline Stone (London: Kegan Paul International)11-20(13).

[xxiv] Hodgson, TheVentureofIslam,457.

[xxv] Ibid.

[xxvi] Ibid,75.

[xxvii] Gabrieli,“Adab”.

[xxviii] Vartan Gregorian, Islam: A Mosaic, Not a Monolith (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2003), 2627.

[xxix] Hodgson, TheVentureofIslam,451.

Professional wailers, or funeral mourners, are performers paid to present the eulogy at a funeral and lament the deceased through weeping and singing. Surprisingly, this seemingly out-of-no-where career has a history dating back 2000 years to the Han dynasty and is deeply rooted in traditional Chinese culture. On one hand, wailers still play a dominant role in Chinese funerals, but on the other, they are socially and culturally marginalized because whenever they work, they are exposed to death: China’s biggest taboo. They are excluded from attending merry events such as marriages, festival celebrations, and sometimes even family dinners. In this article, I will talk about what wailers do during services and argue that despite being threatened by social stigma and being once rallied against by the government, their persistence indicates they fulfill a deeper function: social service accords with mainstream philosophical and religious values, and catharsis via ritual performance.

Wailers have developed a professional routine of service. During funerals, wailers always wear white, just like the rest of the mourning family. Most wailers act as proxy children or parents of the dead during their performance, as if they were sending off their family members. They will often start the eulogy by howling “dad” or “mom,” and then kneel or kowtow in front of the coffin as children do. The eulogy is written specifically to recall the life paths of the dead, and praise their personalities, accomplishments, devotions to families, and contributions to communities. According to my interviews with professional mourners in Ningbo, the most frequently honored were the dead’s devotion to their families and their resilience through difficult times in their lives. In addition to being specially written for each funeral, eulogies also have a rhythmic cadence spicing up the performance.

The most important part of their jobs, wailing, comes during and after the eulogy, and must abide by specific rules. Three “golden standards” are followed according to the wailers I interviewed in Ningbo to be recognized as a great wail. First of all, tears must be present. While tears in many ways do not indicate authentic sorrow, they still function as the most direct medium for expressing sadness in daily life. Though everyone knows this is a performance, people still expect sincerity out of this forced grievance, just like audiences’ expectations of a play. Second, the crying should not interfere with other parts of the funeral. While conveying emotions is important, wailers are also there to organize funerals and cue for procedures. Especially since funerals serve to accrue mian zi (⾯⼦), the recognition of an individual’s or household’s social status and prestige by others, wailers must make sure they honor the dead through eulogies and dignify the whole family through other parts of rituals. The best wailers present themselves as the most wretched, meanwhile, staying the calmest at heart, making sure all pieces of information are delivered, emotions are communicated to an appropriate degree, and nothing is out of control. Third, you must move people with your wail. Just like other actors, wailers seek to reach the deepest part of souls by arousing emotions. My interviewee, Mrs. Mao, is especially proud of her ability to “move people to cry” and create a melancholy atmosphere at almost every funeral she worked in.

Mrs. Mao is especially proud of her ability to “move people to cry” and create a melancholy atmosphere at almost every funeral she worked in.

As mentioned before, wailer as a profession has every reason to die out. This job requires not only talent and effort to be recognized as good, but an ability to tolerate social stigma against people who work with or around death in Chinese society. Practitioners are ostracized, deliberately not invited to happy occasions because people believe they will infect them with their bad luck. Mrs. Mao, like many other wailers, has grown accustomed to the prejudice. She admitted, “Now I pretend I don’t know there’s a wedding going on, even of my friend’s children’s weddings, so I don’t make them look bad by putting them in a dilemma.” Historically, wailing has also been labeled as superstition and during the Cultural Revolution, it was strictly forbidden to practice. Yet due to the critical nature of the social service wailers provides and their performative effectiveness, they have outlasted the Cultural Revolution.

Wailers demonstrate a crucial social service ability in the context of traditional Chinese moral codes. Funerals in Chinese culture do not end the relationship between the living and the dead. Instead, they mark “an exchange relationship in which the living fulfill obligations to the deceased, often repaying them for their support and love while alive” (Watson 1988, 13; Ahern 1973; Cole 1998). In fact, both Buddhism and Confucianism, two central religious philosophies, emphasize the importance of “filial obligation” (xiao 孝). Confucian filial piety means a moral person should follow the teaching of the elders, obey their commands, and honor them no matter what. When the elders are deceased, one must remember how parents have devoted themselves to their progeny; people are thus obligated to hold the ceremonial duty to “care for the dead” and repay their devotion through a decent funeral. Similarly, in Buddhist moral teaching, the practice of filial piety is the chief good karma because children are paying back their debts to their parents. This doctrine has prevailed over thousands of years and is now in accord with the Chinese instinct to follow xiao and the orthodoxy of ritual practices to hire a wailer. This wailer then fulfills the filial duty of caring and honoring the deceased by acclaiming them through eulogy and expressing unreserved sorrow for their departure.

At the end of wailings, wailers turn to give peaceful condolence in which grief is no longer the theme.

Moreover, wailers highlight the fact that devotion between parents and children is mutual by serving as a medium between the living and the deceased. At the end of wailings, wailers turn to give peaceful condolence in which grief is no longer the theme. Instead, wailers communicate to and from the dead, confirming that the soul of the dead will bless the living to have health, wealth, and success. It is the last devotion of those who have died to their families, which quenches the sorrow of the living and turns their attention to the promising futures blessed by the dead.

As a performer myself, I find wailings to be a potent reminder of the healing power of performance. While the living can be completely occupied by their sense of loss, sorrow becomes a heavy stone that is stuck in their hearts, blocking all channels of relief. This is why “numb” can sometimes better describe a condition of loss than sadness does. At this time, wailers’ public display of vulnerability and intentional exaggeration of emotions turns people’s internal agony into an external tangible entity. When the content of pain is revealed through words of eulogy and wailing, people realize it is something outside of them, thus finding the ability to face it, care for it, and ease it. Performances help people release emotions by making the emotions palpable so that people can pump them through an outlet, which is crying together with wailers in the case of funerals.

Moreover, wailers help soothe the process of accepting the death of loved ones by bidding farewell repetitively in the eulogy. According to my documentation of wailers’ use of words in their eulogy, one of the top words used is “goodbye.” Through the farewells, people are engaging in the last interactions with the dead, making the withdrawal of the dead from their lives feel less abrupt. In other words, people learn to accept the demise of their loved ones by saying goodbye again and again. As performers, wailers are not just there to present themselves, but to actively engage with the audiences. In doing so, they provide closure by guiding people imperceptibly toward their healing journeys.

When the content of pain is revealed through words of eulogy and wailing, people realize it is something outside of them, thus finding the ability to face it, care for it, and ease it.

Bibliography

GALVANY, ALBERT. “Death and Ritual Wailing in Early China: Around the Funeral of Lao Dan.” Asia Major, vol. 25, no. 2, 2012, pp. 15–42, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43486144#metadata_info_tab_contents. Accessed 17 Oct. 2022. GUANG, XING. “THE TEACHING and PRACTICE of FILIAL PIETY in BUDDHISM.” Journal of Law and Religion, vol. 31, no. 2, 2016, pp. 212–226, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26336673#metadata_info_tab_contents. Accessed 18 Oct. 2022.

Martinsen, Joel. “Performing at Funerals: Professional Mourners in Chongqing and Chengdu.” Web.archive.org, 26 July 2010, web.archive.org/web/20100726055651/www.danwei.org/music/professional_mourners.php. Accessed 17 Oct. 2022.

Oxfeld, Ellen. “When You Drink Water, Think of Its Source”: Morality, Status, and Reinvention in Rural Chinese Funerals.” The Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 63, no. 4, 2004, pp. 961–990, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4133197#metadata_info_tab_contents. Accessed 17 Oct. 2022.

Ziling Chen is a Chinese high-school student in the US, a film/play director, an actor, a theater boundarybreaker, and the founder of the Youth Theater. Her narratives fight reductive representation, interrogate social taboos, and offer new takes on traditional practices via film/theater-based encounters.

For a long time, my most conspicuous quirk was to watch people sleep: a stranger next to me nodding away on a train, a security guard on night shift, hand-on-chin, giving in to exhaustion, a friend snoring on a sofa amidst booming party music. They curl up and soften, like a wild cat that has finally decided to surrender her taut posture, her dignified stride. In their sleep, people exhibit a physical sense of trust. They are rendered somehow secure in their vulnerability.

I used to believe Wang Xiaobo (1952-1997) was an author who would never sleep (or, at least, would never let people watch him sleep), until I read the letters he wrote to his wife, Li Yinhe. Wang was born into a family of logicians. Two months before Wang’s birth, his father Wang Fangming, a renowned professor of logic, was identified as a dissident and persecuted. His mother named the newborn Xiaobo — “small wave” — hoping the family could ride the political turmoil just like that. But the New China’s societal frenzy carried Wang further along the unruly waters. After spending twelve years in a rural village in Yunnan as an “educated youth,” Wang came back utterly disillusioned with the sheer chaos produced by human irrationality. Partially due to this experience, Wang writes extensively about the absurdity plaguing the Chinese 1970s. He portrays real irrationality with feigned irrationality, his critical attitude masked by his apparent light-hearted humor and play on logic. Within Wang’s effortless irony, his eyes are wide open, taking in everything, silently judging.

In Wang’s correspondence with his wife Li Yinhe, however, his gaze softens. To Li, Wang is just “like the child in The Emperor’s New Clothes: he shouts when he needs to.” Li was one of the few who appreciated Wang’s work before his sudden death and subsequent rise to posthumous literary fame. She was also the only one that saw, comforted, and brought out the child in Wang. Their first private meeting — which didn’t qualify as a “date” in the China of the seventies — was proposed by Wang around the pretense of returning to Li a Russian novel he’d borrowed from her (he lost it on the way to see her). Halfway through their chat about life and literature, Wang suddenly blurted out: “Do you have a boyfriend?” A little startled, Li said no. Wang then asked, rather innocently: “What about me? ” We don’t know how Li responded on the spot, but apparently, she thought it was an interesting idea. After four years of dating, the couple got married in 1980, the same year Wang made his lukewarmly received literary debut with Earth Forever. In 1984, Wang followed Li to the University of Pittsburgh: Li pursued a sociology PhD, while Wang studied Comparative Literature. They spent four years in the United States, traveling across the country before returning to China in 1988, both to teach at Peking University. In October 1996, Li Yinhe traveled to the University of Cambridge as a visiting scholar, and their brief embrace at the airport was the couple’s last meeting. Wang died of a heart attack in April the next year, alone in the couple’s apartment.

The collection of letters I’m translating was compiled by Li after Wang’s death. It dates from 1977 to 1980, the years when Wang was pursuing Li. In these letters, readers see Wang both as a learned liberal humanist and a young man passionately—sometimes almost childishly—in love. It is the natural synergy between Wang’s various identities that render his writing here particularly mesmerizing: we witness a thoughtfulness conveyed through forthright innocence. There’s a spontaneous, jazzy rhythm in his letters to Li. His tone is never formal, but an artistic sensibility is maintained throughout. Most strikingly, we catch a glimpse of Wang’s literary posture with his guard down, his piercing ironies retracted. From forceful social commentaries, Wang’s pen drifts to a more restful place. He speaks without defense, even though these letters are simultaneously personal and political — poignantly political, because they are meant to be personal. It is in Wang’s expressions of love that he manifests a fundamental, life-giving conviction in individual freedom, an adamant renunciation of top-down narratives. He is not in the posture of an armed-to-the-teeth warrior, but an unguarded lover, a literal humanist.

The one thing above all that I wish to convey in my translation is the grounded elegance in Wang’s expression of vulnerability. To this end, I tried to preserve Wang’s colloquial expressions and his whimsical turns of phrases by bringing readers closer to the author, rather than “foreignizing” Wang’s tone. That is, I sought to convey the lovely combination of playfulness, sincerity, and intelligence of Wang’s correspondence. However, I have kept the Chinese geographical and historical references as intact as possible to keep the couple rooted in the time and space that shaped their relationship. I hope these letters will appeal to readers’ intellects as well as to their emotions, to make them both think and feel about a topic as mundane and profound as love — how it thrives in time, how it resists time.Please don’t hesitate to contact me at xinning.shao@yale.edu if you have any thoughts, questions, or suggestions about my translation. I would love to hear from you, and I don’t mean this as a mere formality. In fact, you will be doing me a great favor in letting me know the unique ways you’ve engaged with my translation. Until then — thank you, and happy reading.

I didn’t realize until we parted ways that the whole process of loving you was completed in parting. That is, every time you walk away, the impression you leave on me makes my addled brain conjure up all the ways I might call out to you for the rest of time. For example, this time I keep thinking: Ah, Love, love. Please don’t blame me for this peculiar thought: Love, that is you.

When you’re not here, I see before me an ocean fogged over with gloom. I know you are on one of those islands out there, so I shout: “Ah, Love! Love!” And almost hear you respond: “Love.”

In the past, knights had to shout their war cries before entering combat. Knight of Sorrowful Countenance that I am,[i] how can I not have a war cry? So, with a silly air, I shout: “Ah, love, love.” Do you like people with a silly air? I’d like you to love me and like me.

Did you know? There was a road that knew me in the countryside. Once upon a time, clouds were as white as bulging fists in the deep azure sky, then down that road came an innocent, clumsy kid. He looked just like the photo I gave you. Then came a teenager, dark and thin. Then came a guy, tall and skinny and ugly, fatally slack in disposition, extraordinarily fond of fantasy. Then, after a few decades, he would never walk that road again. Did you like his story?

The following letters were written when Li was attending a meeting in southern China. Li was an editor at GuangMing newspaper, and Wang, a worker at a street factory in Xi Cheng district, Beijing.

Li Yinhe, Helloooo! Since you left, I’ve been rather gloomy, like Don Quixote longing for Dulcinea del Toboso every day. God forbid, I’m not making fun of you, and I’m definitely not comparing you to Dulcinea. I’m just saying I’m like that lovesick Knight of the Sorrowful Countenance. Do you remember how Cervantes described our old man going through those trials and tribulations in the black mountains? That’s how ridiculous I am right now.

I’ve developed a new habit: every few days I need to tell you something that I wouldn’t say to anyone else. Of course, there’s more that I don’t tell you, but as long as I bring those thoughts to you, I’m satisfied when I leave, and they don’t bother me anymore. It’s weird, right? I torture others when I vent my odd ideas, but I torture myself when I don’t. I think I should march on now. Someday I will try creating something beautiful. I will try every path until you come and say — “Forget it, Mr Wang. You can’t.” I feel hopeful, though, because I’ve gotten to know you — I really need to make some progress.

I’ve realized that I’d been a bit of a loser. Your dad wasn’t wrong at all. But I’m not anymore. I’ve got a conscience now. My conscience is you. Seriously.

I’ll remember what you said. I promise I’ll show you my true self one day. Why not now? Ah, the future me is going to be better. I’m already sure about that. Please forgive this bit of young man’s vanity, but don’t make me tell you my flaws. I’ll try to get rid of them on my own. I’m going to start improving myself. For you, I want to be the perfect man.

I’m afraid the weather in Hangzhou now isn’t very pleasant. I wish you a happy day in “paradise.”[ii] Please excuse my handwriting — which is as good as it gets.

20th May

Wang Xiaobo

Li Yinhe, helloooo! I concocted a “poem” today. For you. It’s not exactly presentable as a gift — I’m starting to feel very self-conscious now.

Today I feel especially dreary

I think about you

When darkness dawns

Walking with you on bright stars

When light falls onto the leaves

Walking on dancing light-shadows

When words linger on my lips

When I’m with you:

My comrade in arms

I think of you

When I step over all the drift and declare war on the eternal

You are the flag of my army

When I was with you, I might have come across as pretty standoffish. I have a sort of split personality. I might be aloof and flippant, but only on the outside. It’s rather embarrassing to admit this. As to what’s on the inside? Naivety and goofiness. Aha, I realize that you never showed me your poems, either. You might have a split personality too, who knows? A fantastic conversation in Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion gets to the crux of the matter:

HIGGINS Doolittle, either you’re an honest man or a rogue.

DOOLITTLE A little of both, Henry, like the rest of us: a little of both.

Of course you are none of either. I admit that I’m a little of both: remove the “rogue” part and I become a moderately kind “honest man”; remove the “honest man” part and I become a cynical rogue who hurts people with words. To you, I’ll be an honest man. Hope you have a good day.

21st

Wang Xiaobo

Hello, Yinhe! [iii]

I received your letter.

I think I get you now. You have a soul that’s whole, a bright, inspiring model. Beside it, mine seems a little dingy. Let me answer your question. You already know my love for you is a little selfish. Really, who could have such a jewel and not want to hold on to it forever? I’m no different. I know very well how amazing your love is (and how hard it is to find such a thing!). How could I bear to let you go?

That said, there’s an overarching belief of mine, it’s my secret, I’ve never told anyone about it: namely, one can’t know oneself easily, because our senses are all turned outward, in a way that lets us see others but not ourselves. We can have the most sensitive perceptions of others, but only fuzzy ones of ourselves. One can control one’s thoughts, but as for the sources of those thoughts — who can control them? Someone might be able to write fantastic novels or music, but not be able to tell you the reason why he can write them. No matter how great or humble a man is, when it comes to his deepest, most intricate “self” — he remains oblivious. This “self” stays silent in most people, and so do they themselves. They repeat the same lives on and on, living today just like the day before. In other people, though, the “self” foams and seethes, bringing ceaseless suffering to its owner. What would you say drove the blind Milton to labor on and on at his poetry? Nothing other than the “self.” You see, many people have made promises about it. Undershaft says he’d sworn, when he was still hungry, that nothing could stop him except a bullet. But what happened after he became a rich guy? His heart went quiet, and he stopped caring.[iv]

As for me, I hope my “self” will never be silent, whatever suffering it brings me. We’re all alive right now, but soon, when we look back, our “self” will only once have been living. I would rather keep it foaming and seething until my very last second. I would never wish for my heart to grow quiet, never to stop caring. I know — life and death; these are supposed to be each person’s own business. No one can save another’s soul, and in fact how fantastic it would be if everyone had a ceaseless soul! I really wish my soul could be, as you said, a source, an inexorable one (of course that’s impossible). I wish for my “self” to sizzle forever, to toss and turn, like a drop of maltose on charcoal.

I hope there will never be a day when I feel I have had enough wisdom to get by, enough to tell right from wrong. You already know I hope everyone has their own wisdom; you also know I believe people can only save themselves. That’s why I never want to seize souls that don’t belong to me. I only hope that our souls can interflow, like a shared body doubled in size. Do you know how lonely a solitary soul is, how much weakness humans carry (weakness that makes us weep) — and how much strength, how much warmth a soul like yours can impart? Open the gate to your soul, and let me in!

Based on such beliefs, I want absolute freedom for you. I want your soul to soar. Of course, if you were to fall in love with someone else someday, wouldn’t that darken my soul further? Aside from being jealous, wouldn’t it also declare that I’m doomed? If that day ever came, how could you still ask me to be in high spirits? No one would sing “Sailing the Seas Depends on the Helmsman”[v] after realizing he’s doomed, so, I mean, your request is kind of too much. Nonetheless, from my currently rational point of view, you’d better leave me alone when that day comes. If I change my mind then, that would just be me being bad. Just walk away — don’t give it another thought.

I ask for only one thing: if that day does come and I’m still who I am today, don’t turn your back on me, stay friends with me, and be tender with me. Try not to hurt me.

I don’t like being quiet and just “living a life”. Neither do I like being shameless and clinging on to other people. As for marriage and that sort of thing, I don’t even think about it. I need nothing deemed necessary by worldly standards. To “love” or be “indebted” or whatever, that all seems pretty trivial. I only want you to be with me. I only hope for us to be together, without suspicion, without having to worship each other: we’ll live, just that. You’ll talk to me as if you were talking to yourself. I’ll talk to you as if I were talking to myself. Talk — talk to me, will you?

Xiao Bo

Wednesday

And yes, about joining the Party, I’m afraid that I won’t. If I want to join, I’ll have to do some … stuff. Well, anyway, in our factory,[vi] Party members are either fifty-ish old women with unbound feet, or little girls who like to make a fuss over everything. Neither category will be easy for me to fit into, especially because, I’m afraid, it’s fundamentally impossible to change genders. Talking this way sounds frivolous, but what I’m saying is completely true. I’ll stop talking because if not I’ll want to tell you something else — so, until next time.

Hello, Yinhe!

I’ve been busy dealing with my midterm exams and waiting for you to return. How have you been? I saw you in my dreams a few times.

Beijing is getting really cold. It must be warmer down there in the south, right? Sometimes I wish we were migratory birds, so I could fly south with you when winter comes, or to a tiny island in the Southern Pacific.

If I were a composer, I could write a funeral march with overflowing inspiration right now. I’m miserable all day every day. If you come back though, I’ll be happy right away. I’ll light a firecracker that rocks all of Beijing.

I heard from our teacher in class today that Wuxi is the highest-income rural town in China. Hmph, you guys are in a good place indeed. I bet you must have seen a lot of quaint little houses and fancy, wood-carved beds by now. Something much less pleasing awaits you when you go to Henan later.

Sooner or later China will drown in its sea of a rural population. I know some young people nowadays want changes, but they’re being, in my opinion, a little reckless, like rats in a sinking ship. They want revolutions to save themselves and everyone else. But the captains want everyone to stay on that sinking ship like loyal sailors. Alas, loyalty can’t save you from drowning. People say that China’s ecosystem has all been disrupted. Eventually the day will come when there’s no fish in the pond, no firewood in the stove, and all the soil will be salinized, and all Chinese people will have to pile up on top of each other. There must be a change indeed.

Yinhe, I guess all this will only happen after we die. I love you, Yinhe, let’s live a happy life together! Yinhe, come back soon.

Hello, Yinhe!

You’ll be back on Saturday, right? That is, only two days left. Ah, I’ve been waiting for that day for too long! Your reply last time was really interesting. You spelled all the English words wrong — “Bye-bye,” “fool,” neither were correct — except “Party”. That’s pretty funny.

I’m drifting further and further away from the Party’s standards, Yinhe. Really, I’ve almost become a rebel. How do I put this? I’m more and more convinced that a mundane life, where everyone plays a role in this entire societal performance, will suck all the energy out of us. Every single thing we do is to fulfill a duty. Our personal values are already written out for us and carved in stone. Isn’t that pathetic — how little fun we can have being a person? No wonder some people would rather be a mad dog.

The most hideous thing of all is that one will then sink into a state of numbness. If everything you do has been done a million times by others, isn’t it nauseating? Let’s say you and I are a twenty-six-year-old man and woman, and by society’s standards, twenty-six-year-old men and women ought to do this and that. And so, we do this and that, leaving no stone unturned. What’s the point of being human then? It’s like licking a plate that a million people have already licked before. Disgusting to even think about.

These days, whenever I pick up my pen I want to write about people in love — arrogantly, self-sufficiently in love. This kind of love is anti-social. George Orwell was right, but his intuition was off. He thought it was just sexual drive. More often than not, “to love” is a basic sort of behavior of our fundamental selves, and we can only see people’s true colors when they love. All the rest they do is hollow, incapable of revealing anything. Perhaps it’s also because I’m too much of an imbecile to see it. Perhaps one day I’ll understand what human beings truly need. That is, what kind of life can we

build for ourselves, away from that dusty societal order (the damned repetitions, the boring and pointless disruptions), away from any religious devotion. If a person could reach a state where there aren’t any constraints, no tinge of worry about anyone’s judgment — just look at how wild he could be! My guess is that he would experience a kind of ecstasy, but of course whether they could reach that state is a matter of talent, too. For love, people can do the most beautiful things, a million times better than what could be done by the loveless.

To think that you will be back soon — what wonderful news! I miss you so much it’s killing me now. Now the wait is finally over. I will be with you soon.

I haven’t been writing novels for a while, because of the exams. And I feel it’s pretty dangerous to write novels just now. We should be focusing on the “Dou, Pi, Gai”[vii] and purging remnants of capitalist elements from our society. If I keep writing and somehow else is creating my own thought system, wouldn’t I be imprisoned and shot? And I write poorly. I don’t have the necessary talent — I’ve regressed. Nobody in the entire world thought highly of my novels, except you.

Love, Xiao Bo

I won’t write you letters anymore. I’ll tell you all about it when you come back.

[i] Wang calls himself “the Knight of the Sorrowful Countenance” after Don Quixote on multiple occasions.

[ii] Likely referring to the idiom praising the heavenly beautiful scenery in Hangzhou and Suzhou: “There is Paradise above and Suzhou and Hangzhou below. (上有天堂,

杭)”

[iii] Yinhe (银河) means “galaxy” in Chinese.

[iv] UNDERSHAFT “I was an east ender. I moralized and starved until one day I swore that I would be a fullfed free man at all costs—that nothing should stop me except a bullet.” (Major Barbara)

[v] Sailing the Seas Depends on the Helmsman(⼤海航⾏靠舵⼿)is a Chinese revolutionary song that was commonly sung by the public during the Cultural Revolution in praise of Mao Zedong Thought.

[vi] Wang put “街道⼚“ which most likely refers to, according to this article, ⼆⻰路街道⼯⼚(Er Long Street Factory) where Wang worked at during the Cultural Revolution [http://ny.zdline.cn/h5/article/detail.do?artId=37649]. The name was omitted here due to a lack of precise record and to not disrupt the reading.

[vii] “⽃Dou, 批Pi, 改Gai (To battle, to criticize, to change)” are the three main tasks of the Cultural Revolution proposed by Mao in 1966.

I would like to thank the following persons for their incredible literary sensibility and generosity: Professor Peter Cole, Spencer Lee-Lenfield, Baylina Pu, Elizabeth Raab, Adrienne Zhang, Eunsoo Hyun, Forrest LaPrade, Shi Wen Yeo, Adin Feder, Will Sutherland, Daevan Mangalmurti, Anne Northrup, and Grace Blaxill. Without these brilliant souls, this translation would have been impossible.

translated by Isabelle Qian

translated by Isabelle Qian

This is true.

There was once a girl-child from a wealthy village family, born beautiful, and many matchmakers came to marry her off, but none ever succeeded. That year, she must have been only fifteen or sixteen. It was a spring evening, and she stood at the back door, resting her hand against a peach tree. She remembers wearing a moon-blue shirt. The boy across the street had seen her before, but they had never exchanged words. He walked up to her, not too far, stood still, and softly asked, “Oh, are you here too?” She didn’t say anything, he didn’t say anything, only waited there awhile, and then each walked away.

Just like that, it was over.

Later on, the woman was kidnapped by a relative and sold far away as a concubine. She was resold again and again, bearing through the countless winds and waves of life. She has grown old, and yet she still remembers that long ago moment and speaks of it often — on that spring evening, under the peach tree by the back door, that young man.

You meet the person you meet among thousands of people, and in the thousands of years, that endless wilderness of time, there can be no step sooner, no step later. You just happen to catch upon them, and then there is nothing else to say, other than to softly ask, “Oh, are you here too?”