Follow the Money (II)

How Will the Expanded Learning Opportunities Program Funding be Spent in Los Angeles County?

By Chiara Parisi, Theo Zarobell, and Patrick Murphy

How Will the Expanded Learning Opportunities Program Funding be Spent in Los Angeles County?

By Chiara Parisi, Theo Zarobell, and Patrick Murphy

• Expanded learning programs are intended to go beyond the classroom to engage students in “enrichment, play, nutrition, and other developmentally appropriate activities.” CDE guidance emphasizes that the expanded learning program must include (1) a homework assistance or tutoring program and (2) an educational enrichment program.

• To help LEAs implement the program, the California Department of Education has allocated up to $5 million to the System of Support for Expanded Learning (SSEL) to provide assistance with planning, evaluation, and training.

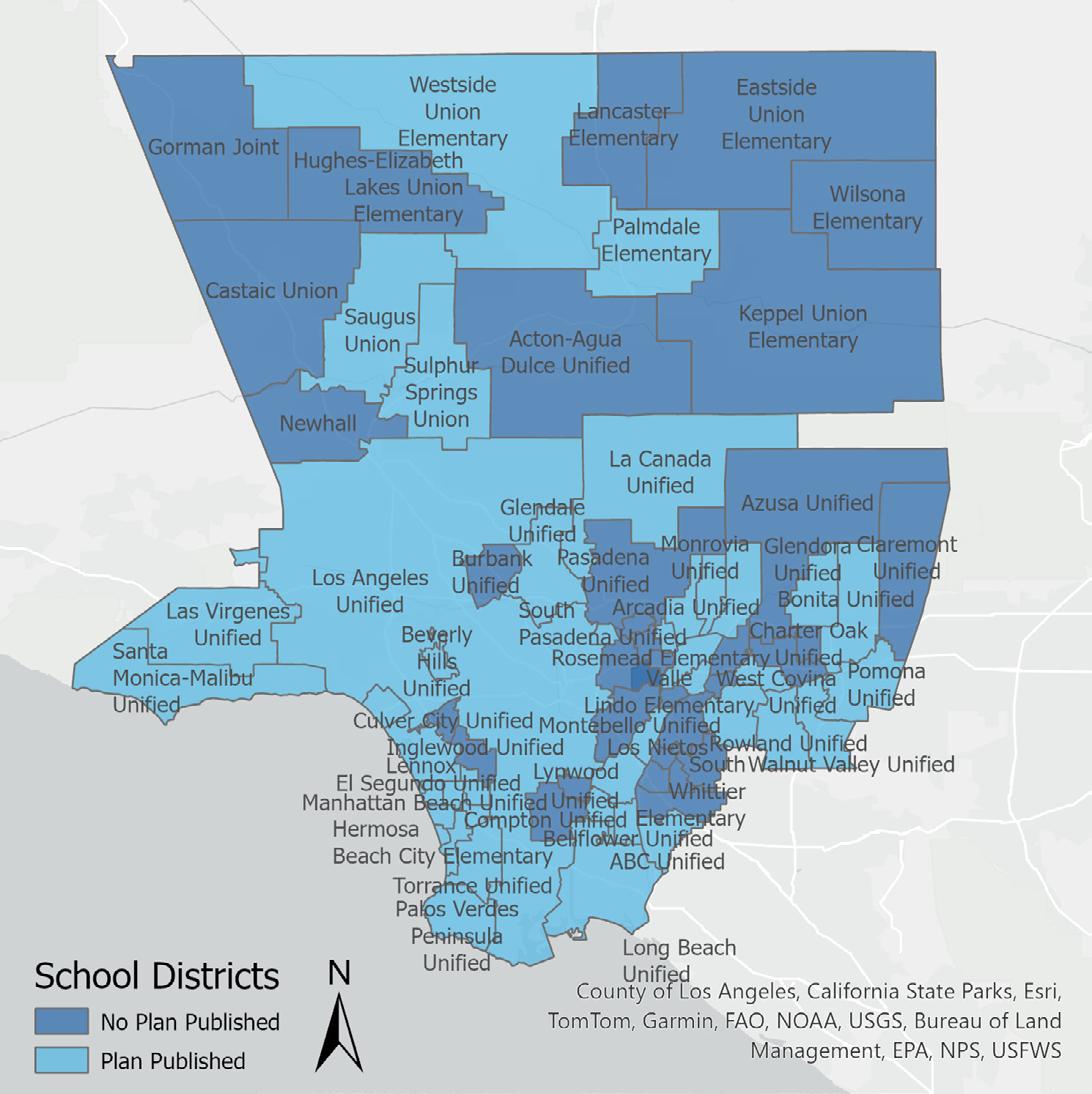

• Every three years, LEAs that receive funds through the ELO-P are responsible for creating, reviewing, and updating a program plan which is then approved by their board and posted on the LEA’s website. Out of the 79 school districts in Los Angeles County, we were only able to locate 40 plans via web searches.

• Our review of the available plans found that they are relatively broad in the description of how the LEA will apply the ELO-P resources. Although the overall approaches described in the plans reflect the guidance provided by the CDE, absent specifics or a budget breakdown, it is difficult to ascertain just how much emphasis the district intends to place on the different elements.

California has invested $13.75 billion in the Expanded Learning Opportunities Program (ELO-P) through 202425. ELO-P provides funding for before school, after school, summer, and intersession learning programs. The first round of funding was allocated to local educational agencies (LEAs) in 2021-22, and funding has been distributed every year since. When establishing the program in 2021, the Administration set a target of funding the program at $5 billion annually on an ongoing basis, and provides $4 billion in the current school year.

This series takes a close look at the ELO-P in Los Angeles County, recipient of just over one quarter ($1.1 billion/year) of the total state allocated funds. The goal of the series is to better understand how ELO-P funds are being distributed and spent with the aim of supporting policymakers in ensuring equity and efficacy in the distribution of current and future funding, and high quality program offerings for kids that meet the needs of families. In the first post, the Opportunity Institute provided an overview of the program and examined LEA funding amounts in Los Angeles County. In this second post, we will look into how LEAs in Los Angeles County propose to spend the apportioned funds.

The ELO-P provides funding for before school, after school, summer, and intersession learning programs to students in grades transitional kindergarten through 6th grade. Expanded learning programs are meant to go beyond the classroom to engage students in “enrichment, play, nutrition, and other developmentally appropriate activities.” Expanded learning opportunities are described as “pupil-centered, results driven, activities…that develop the academic, social, emotional, and physical needs and interests of pupils through hands-on, engaging learning experiences.”

More specifically, the expanded learning program must include (1) a homework assistance or tutoring program and (2) an educational enrichment program. The homework assistance initiatives might include literacy coaches, high-dosage tutors, and teacher’s aids. The educational enrichment programs could include fine arts, career technical education, recreation, physical fitness, and prevention activities.

To help LEAs implement the program, the California Department of Education has allocated up to $5 million to the System of Support for Expanded Learning (SSEL) to provide assistance with planning, evaluation, and training. The SSEL consists of the California Department of Education staff, sixteen County Offices of Education, and contracted Technical Assistance Providers, including the California Afterschool Network (CAN) and ASAPconnect. Additionally, the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence (CCEE) supports LEAs receiving ELO-P funding.

The SSEL bases its assistance on the Quality Standards for Expanded Learning in California (Quality Standards) to guide LEAs. The Quality Standards were developed in 2014 and are intended to “create a framework of clear expectations, and a shared vision of quality among multiple stakeholders.” They focus on point-of-service quality standards generally, such as safe environments, engaged learning, skill building, youth voice, healthy behaviors, and equity. They also include programmatic quality standards, like quality staff, clear vision, partnerships, continuous quality improvement, program management, and sustainability. While these standards provide a common starting point, there is considerable room for how they may be implemented in practice.

Every three years, LEAs that receive funds through the ELO-P are responsible for creating, reviewing, and updating a program plan. The Expanded Learning Division of the California Department of Education developed the Expanded Learning Opportunities Program Plan Guide (Plan Guide), based on the Quality Standards, to help LEAs developed their plans. The Plan Guide is intended to help LEAs engage in reflection and be intentional about program management practices and activities delivered to students.

Program plans need to be approved by the respective LEA’s governing board in a public meeting and posted on the LEA’s website. While there is no explicit due date for the program plan, LEAs should have their plans approved before the first day of program operation. LEAs are encouraged to collaborate with community partners when developing their plan and they can amend the plan based on changes in pupil needs

Out of the 79 school districts in Los Angeles County, we were only able to locate 40 plans via web searches. The following analysis is based on the 40 plans that have been made available. In addition, there are also 259 charter schools that received ELO-P funding (representing 12% of the funding for the county) that are not included in the analysis to the right.

Districts were asked to clearly define their “vision, mission, and goals” for how they plan to use expanded learning opportunities funding. Probably not surprisingly, the themes that emerged among participant plans were presented in broad terms. Many districts emphasized fostering a “studentcentered” approach to learning that addresses the diverse needs of students. Programs also mentioned taking a holistic approach to youth development, focusing on not only academic growth, but also on social, emotional, and physical well-being. Fostering skills like critical thinking, problemsolving, communication, and teamwork through experiential hands-on activities were included in some plans. A small number of districts linked their goals with broader district objectives to ensure coherence and synergy. For example, Bellflower Unified School District decided that their ELO-P goals should be the same as their LCAP goals in order to create an “overarching focus for all schools and programs”.

As stated above, each expanded learning program must include both a homework assistance or tutoring program and an educational enrichment program. Interestingly, the program plan guide published by CDE did not directly ask districts to outline how they would meet these program requirements. Nonetheless, we combed through district plans to try to identify whether and how the plans addressed these more specific elements.

Most program plans indicated that the district would offer tutoring and homework assistance in some form. A few districts, however, made no mention of tutoring or homework assistance initiatives in their program plan, including Los Angeles Unified School District. Among the districts that mentioned tutoring and homework assistance, the type of assistance discussed appeared to vary widely in terms of quality. For example, many districts only mentioned providing structured homework time. A subset of those referenced homework time with supervision from instructors or teachers. A few described group-based initiatives, such as peer-to-peer tutoring or interactive study groups. Others focused on developing a program that aligned with the Common Core Standards, including literacy-building initiatives or supplemental math and English lessons. A small number also mentioned formal one-on-one tutoring programs. For example, Lennox School District created the El Espejo program where Loyola Marymount University students mentor and tutor Lennox students.

Enrichment programs can include a variety of initiatives. One of the most common enrichment programs mentioned by districts was some sort of physical fitness activity. Activities such as sports clubs, yoga, outdoor recreation, or dance featured in the plans. Beyond physical fitness, plans frequently mentioned Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) related activities (coding, robotics, engineering, or website development) as well as art-based programming (arts and crafts, fine arts, graphic design, theater, and music). Other activities that emerged included gardening, nutrition and cooking, field trips, podcast development, and career planning. It was common for districts to emphasize integrating Social Emotional Learning (SEL) practices into their enrichment plans, including character-building activities, mindfulness curriculum, and service learning projects. Finally, programs typically provided snacks or meals to students during these activities at no cost, as well as transportation when needed.

As previously mentioned, expanded learning programs can be provided before school, after school, and/or during the summer/intersession. The pie charts below demonstrate the time of program offering of the 40 districts for which we reviewed program plans. A couple of districts did not indicate at what point in the day or year their program would be provided.

Districts were asked to describe how their program supports opportunities for students to play a meaningful role in the program. One common way districts indicated they would include youth voice was during the program design. Their plans described gaining input on what activities are desired through surveys, focus groups, and advisory teams. Many districts also identified opportunities for leadership roles within the program, like leading group projects, peer mentoring, and facilitating discussions. Some districts proposed fostering youth voice and leadership through community engagement activities including activities that allow students to address local and global issues, plan community events, and participate in meaningful community service projects. Last, consistent with the emphasis on SEL, certain programs focus on building positive relationships between students and staff so that students feel comfortable expressing their opinions, concerns, and ideas.

The types of collaborative partnerships outlined in program plans varied from district to district. Many mentioned partnerships with district agencies and administrators, like nutrition and housing services, special education, parks and recreation departments, and school psychologists. Several also mentioned collaboration with students, parents, and community members to solicit input and feedback. Others expanded to partnering with community-based organizations to provide components of their expanded learning program, such as mental health support, sports, arts activities, or health services. For example, nine of the 40 plans reviewed have mentioned collaborating with the YMCA. Other partners that were mentioned in program plans included STAR Education, LEARN, Boy and Girl Scouts, Boys and Girls Club, and Options for Learning. A few districts almost entirely give over their expanded learning program administration to an independent organization. For example, the organization Think Together manages the expanded learning program in Bellflower Unified and Duarte Unified. In Palmdale Elementary and Sulphur Springs Union, the organization RISE administers expanded learning activities.

Districts outlined a variety of methods for ensuring continuous quality improvement. There was a strong emphasis on engaging stakeholders such as staff, students, parents, and community partners. Most programs employ multiple methods of accumulating data to assess quality and identify areas for improvement, including surveys, focus groups, selfassessments, or attendance and academic records. Some districts also highlighted the importance of regular reporting of progress to stakeholders to promote transparency and accountability. Many districts mentioned professional development opportunities for their staff members to ensure they have the necessary skills and knowledge to maintain program quality. A large number of districts also mentioned supervision at implementation sites

and regular meetings with staff to control quality. Numerous districts mentioned tracking compliance by circling back to the Quality Standards to ensure that their initiatives are in line with recognized benchmarks for program excellence.

As mentioned in the first post of this series, the ELO-P prioritizes high needs students in the funding formula, with districts and schools with the highest of unduplicated pupil percentages (UPP) receiving the most resources. The program also is designed such that once a district or school receives funding, the highest needs students within that school are prioritized in receiving services.

Beyond this, ELO-P funding recipients were asked to describe the ways they plan to create environments that embrace diversity and equity. Many programs emphasized creating inclusive environments that celebrate individuality and diverse cultural backgrounds. This might involve providing opportunities for students to share their backgrounds, activities and curriculum that promote cultural awareness, and cultural heritage month celebrations. Some districts provided their staff with training on understanding biases and cultural competence. Other approaches to embracing diversity included hiring staff who reflect the community served, providing language support, and accommodating different physical and developmental abilities.

The program plans described various ways districts plan to create safe and supportive environments. Most districts emphasized implementing safety procedures, like conducting safety drills, CPR and First Aid training, and check-out procedures. Districts also mentioned integration of social emotional learning lessons to promote positive behavioral interventions, self-regulation, and emotional well-being. Further, districts also touched on policies against bullying, discrimination, sexual harassment, and substance abuse.

The plans detailed the management and oversight structures for each of their programs. Despite variations in organizational structures and specific roles, several themes emerge. Each program has administrative oversight, with individuals responsible for managing budgets, reporting, ensuring compliance with regulations, and designing program operations. The programs then have implementation staff involved in the day-to-day operations of the expanded learning program. Staff models often include a mix of full-time staff, part-time staff, and volunteers. As noted already, some districts essentially have out-sourced the provision of services and programming.

What other funding streams are being used in combination with ELO-P resources?

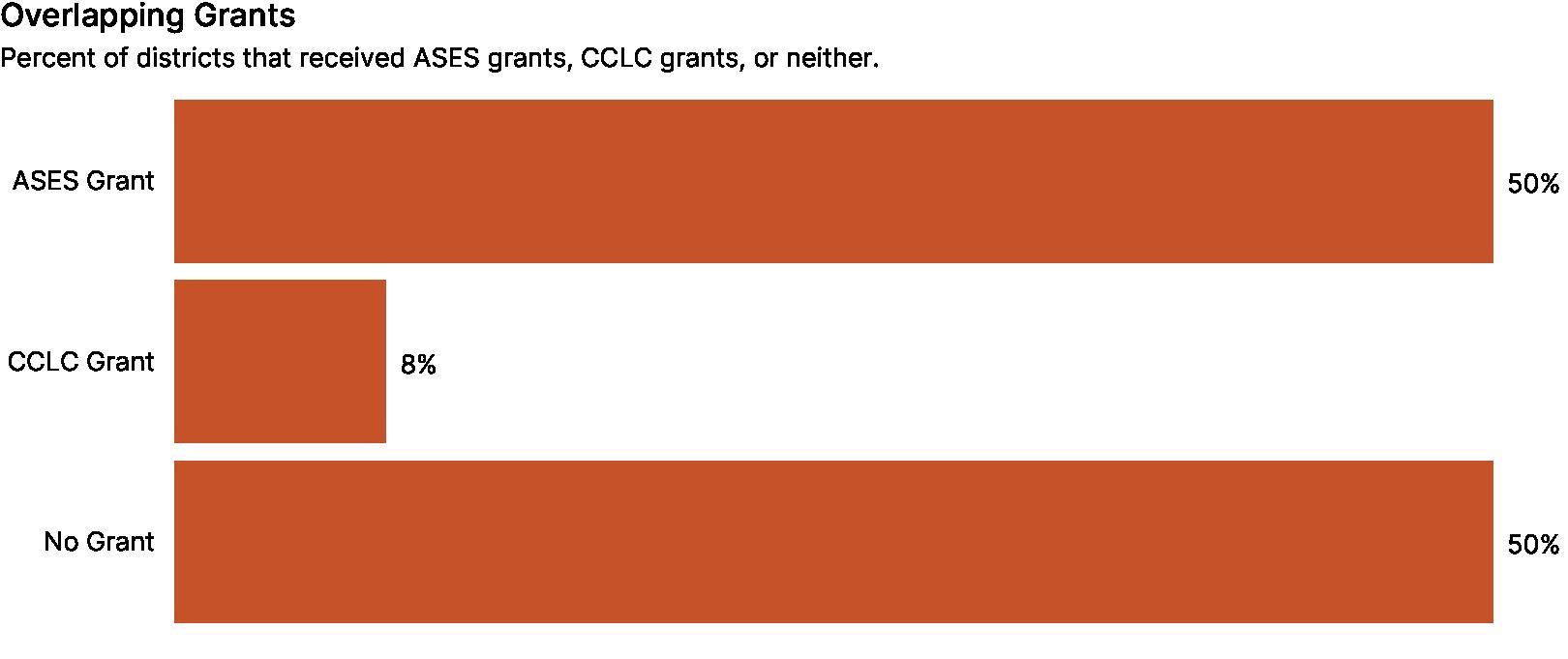

The After School Education and Safety (ASES) program and the 21st Century Community Learning Centers (CCLC) program are intended to work together with the ELO-P to form a single comprehensive program. Unlike the ELO-P, the ASES and CCLC Programs are competitively awarded grant programs at the school level. If the district received either of the grants, they were asked to describe how the ELO-P funding will be used to create one comprehensive and universal expanded learning program.

Of the 40 program plans we reviewed, 20 districts received ASES grants in addition to ELO-P funding. Only three of those districts also received CCLC grants. Most districts emphasized that all funding would be used to operate a single program. Nearly all districts indicated that they would use the newly received ELO-P funding to expand their existing expanded learning program to more students by adding programs to more campuses, eliminating waitlists, or removing program fees for non-unduplicated pupils. No districts mentioned how their program aligned with other funding streams that pursue complementary missions to the ELO-P, like the California Community Schools Partnership Program (CCSPP).

The ELO-P is a significant investment in California’s children and education system. Our goal in this series is to help policymakers and advocates continue to improve the program in order that its worthwhile goals be realized.

As the above description indicates, one overall takeaway from a review of the available plans is that they are long on generalizations and short on specifics. The broad approach does reflect the guidance provided by the CDE, though it makes it difficult to ascertain just how much emphasis the district intends to place on the different elements. Absent any budget breakdown, determining how resources are allocated even at a high level (e.g. how much is being spent on tutoring and homework vs. enrichment activities) is not possible.

In addition to this overarching concern, we note these specific issues.

• The core purpose of the ELO-P is to provide resources for tutoring/homework assistance and enrichment programs. However, the program plan guide did not ask districts to describe how their programs would meet these requirements. Instead, the program plans focused on smaller details of the program, like safety procedures or youth leadership strategies. As a result, there is not always a clear understanding of what districts are spending ELO-P resources on. For example, Los Angeles Unified School District is receiving nearly half of the county’s ELO-P funding, and there is no mention of tutoring or homework assistance initiatives in their plan. The program plan guide should be redesigned to ask districts to focus on the central components of the program – tutoring/homework assistance and enrichment programs – with a degree of detail that enables comparison to the standards.

• It is not clear from the plans that the districts benefited from the System of Support for Expanded Learning (SSEL). The SSEL should provide increased guidance and oversight to ensure that district programs are aligned with best practices. For example, the descriptions of the tutoring and homework assistance appeared to vary significantly in quality in the various district plans. Without guidance on how to put funding to the best use, there is a risk of hundreds of millions of dollars that could go to waste and miss the chance to help close opportunity gaps.

• While districts were asked to describe how their program aligned with ASES and CCLC grants, they were not asked to describe how their program would align with other funding sources that overlap with ELO-P. For example, expanded learning opportunities are a core component of the $4 billion investment in the California Community Schools Partnership Program (CCSPP). ELO-P funding recipients should be asked how they will braid and blend funding beyond ASES and CCLC grants.

In the next post, the Opportunity Institute will look into sustainability and how LEA plans align with what students, families, and community-based organizations say is needed. We invite CDE staff, state lawmakers, researchers, and advocates to consider how this research may inform both short and long-term improvements to the ELO-P.

The authors wish to acknowledge the helpful comments and input they received from their colleagues at Children Now, particularly Maria Echaveste (former president and CEO of the Opportunity Institute), Rob Manwaring, Jessica Sawko, and Vince Stewart. All errors, however, are ours. We also want to thank the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation and senior program officer Erica Lim, Ed.L.D. for their generous support of this project.

Children Now harnesses collective power to achieve transformational and systemic results for California’s kids.

We conduct non-partisan research, policy development, and advocacy reflecting a whole-child approach to improving the lives of kids, especially kids of color and kids living in poverty, from prenatal through age 26.

Learn More childrennow.org instagram.com/childrennow linkedin.com/company/children-now facebook.com/childrennow x.com/childrennow

10