The Pilot TRINITY

Editorial

Welcome to the final instalment of the Pilot for this academic year. In order to celebrate the effort and achievement of our most able students in the sixth form, this edition includes the Howard and Mitchell Essay prise winners and runners up. For this internal competition, LVIth students are encouraged to submit an essay on a topic of their choice which showcases rigorous research and lively academic writing. The Howard prize, celebrates thinking in the arts and humanities whereas the Mitchell prize is awarded to students who have produced a STEM thesis.

Also included in this edition is an outstanding comparative essay produced as part of the A level English Literature course and an award winning entry to the ‘If I was an engineer…’ national competition

As always, we are grateful to Mr Edwin Aitken for his support in sharing some of the outstanding pieces of art that Chigwellians have produced. Within this edition, we have chosen to celebrate our young artists who have entered the Royal Academy Young Artists’ Summer Show and some our most outstanding A Level and GCSE pieces.

We wish you all a very happy summer.

CONTENTS

FRONT COVER:

PICASSO BLUE OR ROSE INSPIRED LANDSCAPE (watercolour + acrylic) MILA PARVAIS

2. EDITORIAL

3. MITCHELL ESSAY WINNER: BACTERIOPHAGES JAMES ISHERWOOD

11 PICASSO BLUE OR ROSE INSPIRED LANDSCAPE (watercolour + acrylic) ANONYMOUS

12. HOWARD ESSAY WINNER: OXFORD’S BENEFACTORS CINDY LYU

20. JOURNEY (mixed media on paper) MEHAKI CHAN

21 MITCHELL ESSAY RUNNER UP: RESOURCE ALLOCATION FORMULA ADAM CIRUS

32. OWL (ink and pastel on paper) AARYAN AGARWAL

33. HOWARD ESSAY RUNNER UP: IMPACT OF LATIN ON ENGLISH ANGELIQUE DAWSON

44. TROPICAL (digital media) MATTHEW JOHNSON

45. COCO’S JOURNEY (digital media) BLAKE IROW

46. HAIR (pencil on paper) LAWIN NAYIR

47. EXPIATION IN HARDY’S 1912 POEMS AND MCEWAN’S ATONEMENT THOMAS REA

58. MOVIES – BLACK SWAN/WHITE SWAN (pencil on paper) ROSALIE AITKEN

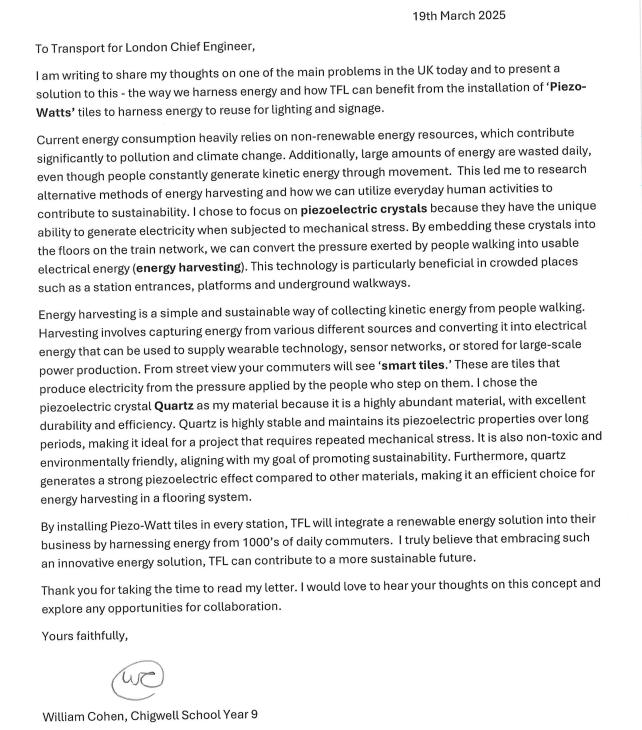

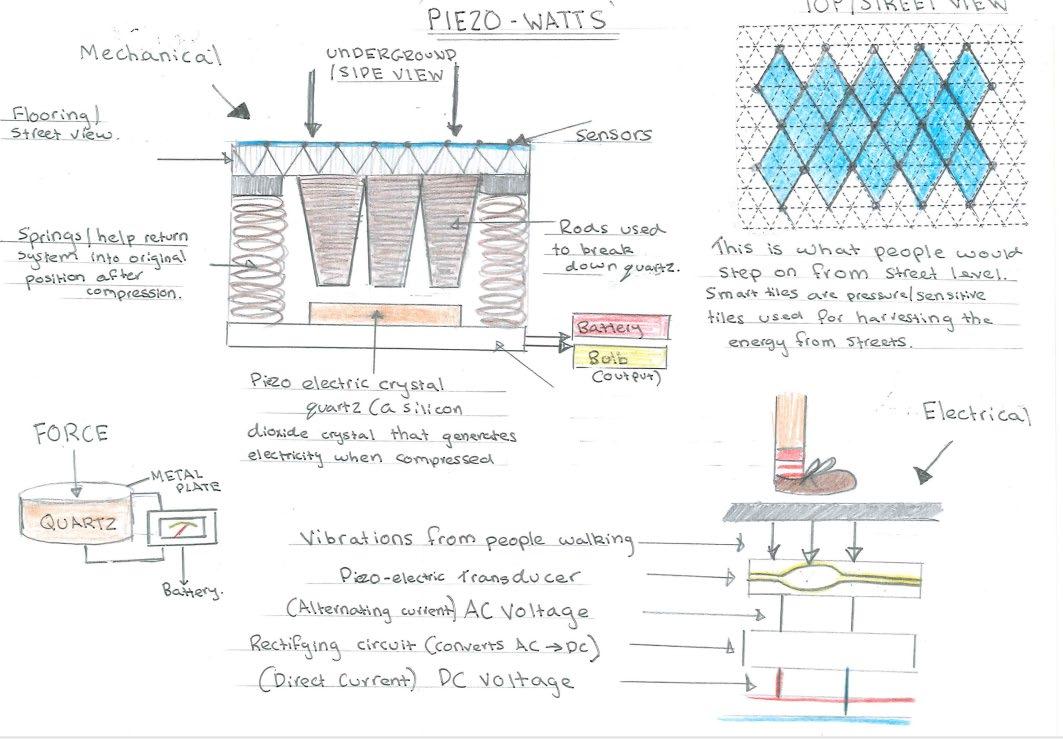

59. IF YOU WERE AN ENGINEER COMPETITION – EAST OF ENGLAND WINNER WILLIAM COHEN

61. PICASSO BLUE OR ROSE INSPIRED LANDSCAPE (watercolour + acrylic) AYAT MAHMOOD

In this prize winning Mitchell essay, James (LVIS) explores whether Bacteriophages can be a replacement for antibiotics

The discovery and use of antibiotics in the 20th century has transformed medicine, saving millions of lives. Alexander Fleming’s 1928 discovery of penicillin and its mass production during World War II turned many bacterial infections into treatable illnesses. Before antibiotics, common infections such as pneumonia or meningitis were often fatal. However, overuse and misuse of antibiotics (for example, failing to complete a prescribed course) has allowed many bacteria to evolve resistance over time and develop into ‘superbugs’. Resistant ‘superbugs’ now spread rapidly through populations, leading to severe health threats. Bacterial genes can be spread through the population via horizontal gene transfer; a complex mechanism explored later in this essay. Due to this method of gene sharing, new resistance can sweep through bacterial communities without antibiotic pressure. Bacteriophages are an abundant virus particle, specifically infecting bacteria. There is hope this precise targeting and the fact that the viruses evolve with the bacteria can be used and studied by microbiologists to help solve and prevent the increase in antibiotic resistance.

Bacteriophages (‘phages’) are viruses that specifically infect bacteria. Phages were discovered accidentally by Frederick William Twort, a bacteriologist working for the Brown Institute in London. Two years later, Félix d’Herelle independently discovered phages at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. When studying them, Félix d’Herelle coined the term bacteriophage, which literally translates to ‘bacteria eater’. The most surprising fact about phages is the sheer quantity of them, being the most prominent biological entity on the planet, with roughly 10^31 of these specialised viruses on earth. In comparison, that’s more than 1 trillion times the number of grains of sand on planet earth! Phages have multiple mechanisms to destroy

bacteria, thereby controlling/reducing bacterial populations. The two main mechanisms include the lytic and lysogenic cycles.

Thanks to complex molecular biology tools, scientists have been able to examine the structure of phages. The main techniques used have been transmission electron microscopy (‘TEM’), cryo-electron microscopy (‘Cryo-EM’), X-ray crystallography, genetic studies and biochemical analysis. The first images of phages were produced in 1939 by TEM, while more recent scientific tools such as Cryo-EM has allowed scientists to analyse phage viruses on an atomic level. The structure of phages comprises of a capsid, containing either double stranded DNA, or single stranded RNA. But, as with all viruses, cannot have both DNA and RNA. The primary role of the protein-made capsid is to protect the genetic material, preventing any damage from the external environment The role of the tail sheath is to contract and force the tail core into the host cell wall. The tail core provides a pathway for the genetic material to travel down and enter the host, to be incorporated into the bacterial nucleoid/plasmid. The base plate is a multiprotein structure at the end of the tail sheath, which adheres the phage to the host and enables attachment. The spikes/tail fibres are responsible for penetrating the cell wall and binding to specific receptors on the host, thereby controlling host specificity. Some spikes will also contain lysosomes, a specialised vesicle containing hydrolytic/digestive enzymes to break down and degrade the bacterial peptidoglycan cell wall.

Phages are highly specific particles, which makes them such an effective use to combat bacterial infections without disrupting the diverse range of ‘good’ bacteria in our bodies which we require to function.

However, this also means that a specific strain of bacteria must be identified correctly for phage therapy to be used effectively. Without precise targeting and the cause of the infection, phage therapy has little use. The reason phages are highly specific is that they can only attach to complementary structures on the bacterial peptidoglycan cell wall. Phages most commonly bind to glycoproteins, pili and other complex molecular structures in the cell wall. Phages will then inject their viral material and adhere to the bacterial membrane. Once the viral DNA is inside of the bacterial cell, it is incorporated into its DNA via two main mechanisms: transduction and integration.

Antibiotic resistance is not a new phenomenon by any means. As soon as antibiotics were introduced, resistant bacteria were already beginning to emerge due to the process of evolution by natural selection. Bacteria, like any other organism, will develop complex strategies to survive and reproduce. Darwin's book, published in 1858 on the ‘Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection’ explains how organisms adapt to their environment to survive and reproduce. An example of this begins with a simple mutation- A rare, spontaneous change in the bacterial DNA. The mutation leads to variation within the bacterial population. This mutation may be beneficial for the bacteria, such as decreasing the permeability of the peptidoglycan cell wall, thereby preventing drug entry into the cell. A selection pressure is applied to the population, killing the susceptible bacteria, while the resistant bacteria are

effectively immune, so therefore survive. The bacteria reproduce by binary fission, a type of asexual reproduction specific to bacteria, where their offspring will inherit the advantageous genes of resistance required for survival. Over time, the resistance genes are shared among the entire population by further reproduction and methods of horizontal gene transfer.

Conjugation is the main type of horizontal gene transfer (‘HGT’). Specifically, conjugation is a process where the donor cell carries a special plasmid, called the fertility (‘F’) plasmid. The donor bacterial cell forms a sex pilus, bringing the two bacteria in close proximity for the transfer of the plasmid. A strand of the plasmid is transferred through the conjugation bridge to the recipient bacteria. Both cells then replicate the strand to reform the complete plasmid, and then both cells involved are further capable of carrying out conjugation with other bacteria, meaning the resistance can be acquired by the entire population.

After Flemings accidental discovery of penicillin in 1928, medicine seemed to be changed for life. Antibiotics are easy to use, manufacture and have a broad range of targeting- making them ideal for treatment. Due to the discovery of antibiotics, much less resources and research went into phage therapy. Phages were seen as highly complicated ultra-microbes, and at the time it didn’t make sense for time and money to be invested into the potential uses of the intricate viruses. Therefore, in many areas of the world, the research and equipment was diverted towards antibiotics However, we now face the disaster of antibiotic resistance. The rise of resistance is largely down to overuse, misuse and overprescription. The problem has been identified- bacterial resistance is becoming increasingly common and we need to fix it. However, the process of finding a sustainable solution for this problem is far more

complicated. A 2016 UK study on antimicrobial resistance (AMR) predicted approximately 10 million deaths per year by 2050 if no action is taken to combat AMR.

Phages have two possible cycles for infection- lytic and lysogenic. In a lytic cycle, a phage attaches to a complementary receptor on the bacterial cell, inserts the viral DNA/RNA into the cell, and like a typical virus particle, hijacks the host cell machinery to mass produce phages. But, in a lytic cycle, it is important to acknowledge that the phage DNA remains entirely separate from the bacterial genome. When the bacterial cell bursts open, many phages are released out of the cell.

Alternatively, phages can undergo a lysogenic cycle, whereby the viral genome is incorporated into the bacterial plasmid, but the bacteria don’t immediately burst as it would do in the lytic cycle. The lysogenic cycle allows the host bacterial cell to live normally with the viral genome. The lysogenic cycle means bacterial cells can replicate by binary fission, the method bacteria use to asexually reproduce, while the viral DNA remains dormant inside of the bacterial genome- enabling the viral genome to be passed down multiple generations. During periods of stress, such as prolonged UV light exposure, lysogenic bacteria will enter the lytic cycle. This causes the bacteria to burst open (lyse) and release hundreds of phage particles which can continue the same cycle. Regarding phage therapy use, scientists are most interesting in the lytic cycle for combating AMR as this immediately destroys the infectious bacteria.

Each person receiving phage therapy would each require a unique ‘cocktail’ of phages to treat their infection. This is the reason phage therapy is describes as ‘personalised’- the dose is always individual and specific to meet that persons infection. In practice, the patient would

need to give a sample of the pathogenic bacteria to be cultured. Then, the isolated bacteria are tested against a ‘cocktail’ of phages from a phage bank When scientists have carefully chosen the correct cocktail of phages to target the bacteria, they are administered by varying ways depending on the type and location of the infection. Once administered, the phages will replicate inside of the bacterial host and burst open the bacterial cells via the lytic cycle pathway, causing a positive feedback loop where more phages are released to infect more bacteria. Once all the pathogenic bacteria have been destroyed by the phages, the phages are unable to reproduce or survive as viruses require a host cell to function. Phages are described to have a self-limiting property, meaning they naturally are removed from the body via excretion or the immune system once they have destroyed the infecting bacteria.

This picture is TEM image showing phages infecting a bacterial cell. The bar in the bottom right indicates the scale of the image, showing that the total size of a phage varies between 100 and 200nm. This image clearly shows the phages adsorbing to the bacterial wall, where it will then use the lytic or lysogenic cycle to infect the bacterium.

One of the most difficult challenges to overcome when developing new drugs is ensuring they are a safe option. Despite antibiotics being excellent at targeting bacteria, they have side effects to consider for the user, such as disrupting the gut microbiome and allergic reactions. On the other hand, Phage therapy is made a more appealing alternative to due to the safety studies conducted so far in clinical

trials. As phage are no-toxic to all human cells, they can’t produce any direct side effects that would harm the patient. In clinical studies, patients treated by phage therapy have noted rare, minor side effects, showing a general trend of fewer side effects in comparison to antibiotics. Bacteriophages have several key advantages over antibiotics, with the most important ones being their host specificity and their ability to co-evolve with the bacterium. Co-evolution is the process where two species evolve in response to each-other over time. In the context of bacteriophages and bacteria, the bacteria will mutate and evolve resistant to phages and the phages will develop new strategies to infect the resistant bacteria. For example, gram positive bacteria have a thick peptidoglycan cell wall, making it difficult for phages to penetrate. Some phages will produce specific enzymes such as endolysins to break into the tough cell wall and infect the bacterium.

Despite the many advantages phage therapy possesses, there are some challenges and limitations to consider before it is used globally. The fact that phages operate only on a specific host has huge benefits, as already explored in this essay, however this property of phages also comes with a challenge. The narrow host range of phages would mean an extremely accurate diagnosis of the bacterial strain causing the infection for the complementary phage to be selected and used in practise. Another challenge is using one specific phage to target the infecting bacteria, as the bacteria may mutate during the infection, causing the phage to stop working. However, microbiologists and bacteriologists have worked together to develop phage ‘cocktails’ that target the same bacterium in multiple ways, so even if the bacterium foes mutate, there are multiple phages that can combat this. As phages are foreign virus particles, the human immune system is triggered, and an immune response is developed against the phages. This is a significant challenge as human antibodies

may neutralise the phages before they reach the targeted bacteria, causing the phages to be removed from the body by phagocytosis or excretion before they have destroyed the pathogenic bacteria. Another challenge for phage therapy is the fact they can both spread and prevent antibiotic resistance. This is done by a process known as transduction where the phage may accidentally incorporate host bacterial resistant DNA instead of its own genomic DNA. When the phage infects the next bacterium, it will transfer these resistant genes, potentially spreading resistance. This is a major challenge as accidental biological processes could harm the reason phage therapy was being used in the first place.

In summary, bacteriophages offer many uses and will work best alongside antibiotics in order to combat the threat of antimicrobial resistance. Phage therapy shows many advantages, including specifically targeting one strain of bacteria, minimal disruption to the gut microbiome and the potential to treat antibiotic resistance. However, limitations such as immune clearance, the risk of horizontal gene transfer via transduction and the limited research, it is unlikely they will completely replace antibiotics. Instead, the most realistic future of phage therapy looks like a promising relationship, working alongside antibiotics to cure bacterial infections.

JAMES ISHERWOOD, LVITH

ANONYMOUS IV

In her prize winning Howard essay, Cindy (LVIL) explores whether Oxford should lower its admissions standards for the offspring of generous benefactors..

Some 24 years ago, Mr Philip Keevil a City banker and long-time Oxford benefactor who had donated over £100,000 to the university over 15 years was all set to cement his family’s legacy at Oxford. But fate (and Trinity College’s admissions office) had other plans: his second son was rejected, despite Mr Keevil’s substantial generosity (Cassidy, 2001). This anecdote highlights a persistent tension within elite university admissions: to what extent should financial contributions influence preferential access? The question centres on how universities allocate scarce educational resources, respond to financial incentives and balance equity against efficiency.

To explore these dimensions, this essay applies a macro-level PESTEL framework Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental and Legal to evaluate the potential benefits and risks of such a policy and whether it aligns with Oxford’s values and long-term institutional interests. It also conducts a supply-and-demand analysis and considers what Oxford’s admissions criteria ought to prioritise, particularly in light of its current use of contextual admissions, before drawing a conclusion.

Oxford University has a long history of accepting donations from controversial figures including slave traders, imperialists, fascists and arms dealers drawing considerable political and ethical scrutiny (Bhutani, 2021). Yet such individuals have clearly passed the university’s internal review process, which asserts that it “takes legal, ethical and reputational issues into

consideration 1” (SAGE, 2018). Despite sustained criticism of his business activities in postSoviet Russia and alleged ties to Vladimir Putin, Oxford accepted Leonard Blavatnik’s £75 million gift in 2010 then one of its largest donations to found the School of Government (Watkins, 2024).

This leads to a deeper dilemma. Given Oxford’s long-standing entanglement with politically sensitive philanthropy, should it now extend admissions flexibility to such benefactors’ children? Before answering, it is essential to recognise that donor influence does not stop at financial support. International examples illustrate this risk: at George Mason University, the Koch Foundation was allowed to appoint two of five faculty selectors (Barakat, 2018). Similarly, at the University of Pennsylvania, donor pressure over pro-Palestinian rallies prompted resignations and policy clarifications (Moody, 2023).

These examples underscore a broader political risk: large donations may invite subtle or, at times, overt external influence. Lowering entry requirements for major donors’ children could compromise Oxford’s institutional autonomy and political independence. The university must therefore remain vigilant when donations carry political, religious or ideological expectations.

From August 2021 to July 2022, Oxford received £249 million in philanthropic donations, just under 9% of its £2.78 billion annual budget (Oxford, 2022a; Oxford, 2022b). While there is no evidence that current donations influence admissions, the financial incentive is significant. In

1 Source: SAGE Publications. (2018). Ethical review in educational research: Challenges and concerns. Ethics in Educational Research, 25(2), 112–125.

the Ivy League, 4–5% of freshman admissions are linked to donations (Seigel, n.d.). Applying a 4.5% estimate to Oxford’s 2024 undergraduate population (12,375 students) suggests that over 550 places could be donor-influenced (Oxford, 2024). Assuming each donor contributed $500,000, this could generate an additional £206 million over 80% of Oxford’s current annual philanthropic income.

Although this scenario remains speculative, rising global wealth and growing investment in education among the affluent may pressure Oxford to monetise admissions (Micelle, 2025).

If such a shift occurs, it could create a timely opportunity to expand its endowment. With global economic growth forecast at 3.3% and a projected 8.6% annual return, such an influx could grow to £3.07 billion over the next decade, significantly boosting Oxford’s financial future (International Monetary Fund, 2024).

Yet such a policy could send the symbolic message of “pay-to-enter,” discouraging meritbased donors and damaging Oxford’s fundraising capacity and financial resilience. Amid heightened criticism of institutional privilege, a tarnished meritocratic image may also deter top academic talent, jeopardising Oxford’s academic competitiveness. The short-term financial gains from preferential admissions must therefore be weighed carefully against these potential long-term economic costs.

Oxford currently ranks 4th globally, with Harvard remaining 5th despite high-profile donation controversies (QS, 2025). Harvard’s continued global stature exemplifies the symbiotic relationship between philanthropic capital and scholarly excellence a pattern observed across 75% of the top 20 US institutions (Wood, 2025). Moreover, rejecting donations based

on hypothetical future controversies may induce strategic indecision, as universities cannot foresee the long-term reputational trajectories of alumni or donors. Examples include Yahya Jammeh’s post-dictatorship notoriety and Mikheil Saakashvili’s corruption downfall (Pearson, 2014).

Yet Oxford’s prestige ecosystem faces a graver social peril: weakening social mobility and educational equity, ultimately challenging its signalling function. In recent years, Oxford has invested substantial effort in widening participation through contextual admissions, targeted outreach, and scholarship programmes (Oxford, 2020). Introducing preferential treatment for donor heirs could be perceived as compromising these initiatives, entrenching structural advantages and accelerating educational aristocratisation, where wealth is layered atop existing legacy networks.

According to Spence’s signalling model, an Oxford degree certifies unobservable productivity through rigorous selection (Hopkins, 2005). Admitting donor-affiliated under-performers even marginally dilutes this credential by reducing signalling costs for high-wealth, lowability applicants. Once employers begin to suspect that degrees are “purchased” rather than “earned,” they may rationally discount any Oxford graduate’s competence, which reduces the return on investment for every degree holder. For high-ability students from underrepresented backgrounds who rely on that signalling power, this cascade would diminish the degree’s human capital value and impair the university’s role as a vehicle for upward mobility. Dropout risk adds a further concern. While Oxford’s 0.9% attrition rate (one-sixth of the UK average) suggests institutional resilience, admitting under-qualified cohorts carries hidden

costs (Kelly, 2022). US data show that students in the bottom SAT quintile (<990) face a 62.5% attrition rate (Westrick et al., 2022). Though scaling this to Oxford’s hypothetical 4.5% donor cohort implies a negligible systemic impact, the true cost is distributional injustice: every seat sold to an underprepared, economically advantaged applicant represents a lost opportunity for a deserving one whose life prospects hinge on access.

Oxford’s vulnerability to research-related security risks is not new. During the Cold War, the university was implicated in high-profile espionage cases involving KGB infiltration (Walker, 1992). Similar risks remain today.

Since 2017, Oxford has accepted over £99 million in donations from China-linked individuals and entities, supporting initiatives such as the Dickson Poon China Centre and more than 20 other affiliated projects (Cherwell Investigations, 2024). While international collaboration is essential to technological advancement, approximately 38% of these donors are linked to state-owned enterprises or sanctioned institutions, such as Sichuan University, which reportedly collaborates with the People’s Liberation Army (Tabba, 2025). Transparency issues also persist: some donor acknowledgment pages remain blocked from mainland China.

Preferential admissions for donors’ children could create privileged pathways into sensitive STEM programmes or cyber research hubs, increasing the risk of “trusted insider” threats. The China Scholarship Council currently funds over 640 PhDs in the UK, and around 15% of Chinese students in the US, many under limited vetting procedures (UK-China Transparency, 2023; Molloy & Johnson, 2025). These concerns are further compounded by Oxford’s collaborations with high-risk partners such as Huawei (Chen, 2019; DCMS, 2022).

Unlike traditional espionage, this influence is not stolen through covert operations but openly purchased through philanthropy. Donations fund research infrastructure, while admissions flexibility enables its potential exploitation. Upholding rigorous admissions standards is therefore not just a matter of academic integrity but also a security necessity.

Donors may attach legal stipulations to their contributions. In Lindmark v. St. John’s University, US courts held that university donations are typically treated as charitable gifts (Philanthropy Roundtable, 2021). However, in Robertson v. Princeton University, the court ordered a $100 million repayment after the university failed to honour donor intent (Philanthropy Roundtable, 2021). Legal enforceability may arise when institutional actions diverge sharply from stated donor expectations.

Should Oxford lower its admissions standards for donor families, it may invite more explicit assumptions regarding admissions outcomes. Over time, this could blur the line between philanthropic support and contractual obligation, thereby increasing legal exposure and constraining institutional autonomy.

Oxford’s Donor Charter emphasizes respect for donor wishes while maintaining operational flexibility (Oxford, n.d.a). Its donor stewardship programme further manages expectations and ensures alignment (Oxford University Endowment Management, 2024). To preserve both legal defensibility and institutional sovereignty, the university must maintain strict boundaries between admissions policy and fundraising strategy.

Donations have funded several of Oxford’s environmental innovations. From the Login5 Foundation’s support for precision agriculture to breakthroughs in photovoltaic efficiency, philanthropic funding has accelerated progress towards the university’s 2035 net-zero carbon emissions target and biodiversity net gain (Oxford, 2025). Yet funding remains a significant constraint, particularly as European universities frequently cite financial shortages as a primary barrier to environmental progress, suggesting a clear rationale for external support (Havergal, 2021).

However, relaxing admissions standards for “green donors” risks institutionalised greenwashing. Admitting a fossil fuel heiress with subpar academic credentials while her family funds carbon-capture research would undermine the integrity of Oxford’s climate commitments.

Ethical alignment is possible, as shown by the R21/Matrix-M vaccine lab, where philanthropy serves the public good without compromising admissions standards (Oxford, 2021). The imperative is clear: environmental urgency must not be used as leverage to dilute academic standards.

With undergraduate applications rising 21% from 19,000 to over 23,000 against fixed placements at around 3,700 since 2015, Oxford faces classic scarcity pressure (Oxford, 2020; Leland, 2025). Yet domestic tuition caps (£9,535/per year) and international student policy limits (now 43% of students) constrain revenue solutions (Oxford, n.d.b; Bolton & Gower, 2024). With supply relatively fixed and demand rising, economic theory suggests the potential

to raise the “price” of admission. Treating admissions as a pricing mechanism, however, misapplies microeconomic theory: unlike commodities, academic seats derive their value from exclusivity of merit, not exchange efficiency.

The Operation Varsity Blues scandal revealed how wealthy families exploited fraudulent schemes to secure admission for under-qualified students (US Department of Justice, 2019). A formalised donation-for-access framework may seem to redirect this persistent demand into a more regulated mechanism. In SFFA v. Harvard, families donating over $10 million saw a ninefold increase in admissions odds; at Stanford, a $500,000 gift may qualify a candidate as a “development case,” prompting relaxed standards (Parapadakis, 2023).

If Oxford must accommodate philanthropic interest, it should do so without compromising merit. One safeguard is to shield admissions panels from donor visibility, for example by partially anonymising applicant ties. Where donor-linked considerations are introduced, they must be narrowly applied to a small proportion of cases and subject to expiry. To ensure such generosity benefits the wider student body, all contributions should be ring-fenced for needblind financial aid. Crucially, any student admitted via this route must adhere to subjectaverage thresholds and maintain a minimum GPA after their first year to retain enrolment.

Such a model, driven by transparency and grounded in academic criteria, may offer a workable path forward: one that preserves Oxford’s integrity while channeling generosity into public good.

Oxford’s admissions policy sits at the intersection of competing priorities: academic merit, institutional independence, financial sustainability and social equity. As this essay’s PESTEL

analysis has shown, lowering standards for donor families may yield short-term gains but risks systemic vulnerabilities across multiple dimensions.

Total resistance to philanthropic interest may be idealistic, but uncritical accommodation would be economically myopic. While addressing the financial realities of global higher education, Oxford must resist commodifying its admissions gate. The £206 million annual allure pales against the existential cost: turning Dominus illuminatio mea from a beacon of wisdom to a cheque written by a rich dad.

CINDY LYU, LVI

Adam (LVIth L) was named runner up in the closely contested Mitchell essay prize competition. In this piece, he explores equitable solutions to resource allocations.

Resource allocation is a detrimental problem in the modern world and is part of the large economic problem faced by every country. Resource allocation in every economy is inefficient and wasteful of the finite and scare materials we have. It is the process of distributing limited resources across competing regions in a way that balances the three E’s. Efficiency, equity and effectiveness In this essay, I will discuss how the allocation of resources can be made more efficient, with minimal waste of resources and scarce materials in the situation of an emergency, perhaps due to a natural hazard or emergency healthcare needs.

Firstly, to optimise resource allocation, we must derive the factors that increase allocation in a certain region. Currently, the most significant factor is population size. Population size will determine the area that should be allocated the most resources, as larger populations require more resources to sustain and maintain a good standard of living. This can be measured through a consensus or by creating a population model to calculate an approximation of people in a region of need. However, it is important to note that urgency is imperative, as situational needs can affect priority of a region. For example, an earthquake in region 1 with multiple road blockages requires more resources compared to another region with a car crash. It may be wasteful to send multiple ambulances to the region with the car crash, whereas sending more help to a region with an earthquake would be more beneficial as a greater number of people may have been affected. Resource allocation can be measured by severity indices. These are tools or scores that measure how critically or urgently a region needs a resource. Efficiency refers to directing resources where they are more likely to make

a more substantial impact. The method used for this is cost effectiveness analysis, which is used to compare the costs and outcomes of different options to determine which provides the best results for the least cost. This will tell us how efficient resources are being used to achieve a specific goal. Resources can be allocated quicker in regions that are closer to the origin of the resource, this is called accessibility. This variable will impact how much will be allocated to each region based on how efficiently the resources can be transported, whether this is an emergency or long term. We can measure this through analysis of the terrain; if it’s in a mountainous area or in a desert.

Next, we must find the main factors that decrease resource allocation in a certain region. As the government must spend money on these resources and to transport them as well, if it’s not used efficiently then it is seen as wasteful expenditure. Therefore, cost can be derived as a big factor. Cost plays a big role in resource allocation as it ensures that resources are distributed efficiently within budgetary limits. The cost can be measured in several ways including delivery costs, labour costs and material costs. These are just the expenses of transporting, working and the resources themselves. Risk is a critical factor that includes challenges or external shocks that may blockade successful usage of resources. By including risk as a factor in decision making, fewer resources are allocated to regions of the likelihood of failure or when inefficiency is higher. This helps minimise waste and ensure that resources can be utilised in the most effective way possible to achieve the intended outcome. After establishing the main factors, we must now generate a number for each and their respective ranges. For each of these factors, a letter will represent them in the subsequent formulae.

1) Total Population size across all regions: N

2) Urgency: U

3) Efficiency: E

4) Accessibility: A

5) Cost: C

6) Risk: D

7) Total resources: R

8) Region i population size: ��������

We have generated an initial formula that can be added to throughout this essay:

We can create a number by using a range for each component:

1) 0< �������� ≤ ���� , where N is the total population across all regions

2) 0 ≤ U ≤ 1 , where 0 is no urgency and 1 is maximum urgency

3) 0 ≤ E ≤ 1 , where 0 is no efficiency and 1 is maximum efficiency

4) 0 ≤ ���� ≤ 1 , where 0 is inaccessible and 1 is fully accessible

5) 0 ≤����

6) 0 ≤ ���� ≤ 2 , where 0 is no risk and 2 is maximum risk

WHY DO THESE RANGES WORK?

Normalised 0-1 ranges allow all the components to be compared on the same scale, making calculations fairer and more proportional. In addition, the data can be adjusted or scaled to suit specific context or information. Flexibility is vital as it means the formula and its

components can adapt to scenarios based on available information. Values and ranges reflect real life metrics that ensure decisions are not biased and are data driven.

HOW CAN WE IMPROVE OUR FORMULA?

To achieve the most accuracy and a fairer result, we can incorporate smaller factors that alter the formula. Following this, we will now adapt the formula to include all possible improvements thus resulting in a final formula.

The first component to add to our formula is the total amount of resources multiplied by the fraction dedicated to a region. This can be:

Where i is the resources for the particular region and n is the number of regions. This summation tells us the total resources as all the possible resources that can be allocated to all regions added together is the total resources available.

We can include variability which captures fluctuations in needs over time. This is vital for our formula, as it adds the factor of fluctuating needs for regions over time; a regions needs are rarely static and can change due to population changes or external shocks, such as natural disasters. This is important as it accounts for dynamic needs, real time responsiveness and efficiency. This can be measured by the statistical variance in the spread or fluctuation of resource needs over a time period. A higher variance represents more unpredictable needs which may result in additional resources allocated as a buffer or in the case of emergencies.

Variance: ���� 2

To maintain consistency throughout the formula we will continue to use the range of:

0 ≤���� 2 ≤ 1

We can use integration to sum up the effects of the factors over a range. In this case it captures the total contribution of variables that vary continuously. We can use integration as it allows us to account for the entire cumulative impact rather than just isolated points. If you are trying to figure out how much food a village needs over a week, you don’t look at one day’s need, you add up the food needed for each day of the week. Integration does this by combining the small amounts over a range (the week) to find the total. This makes sure we are considering everything and not only one moment.

Partial derivatives. This helps measure how specific factor fluctuations change in response to a particular variable; time, while keeping other factors constant. We use this as resource needs change dynamically due to evolving conditions, emergencies or shifting risks. Partial derivatives allow the formula to respond to these changes by showing the rate of change of a variable. The partial derivatives time unit will be in months, so if the rate of change per month is 20 then by the end of the year, we will have 240 added on.

If �������� (����) represents resource allocation over time, ������������ �������� shows how the allocation is changing at any given moment. This enables the system to adapt in real time.

E.g. a natural disaster hits a region and (R) needs an increase. �������� �������� > 0 indicates that allocation must increase. Once the disaster is contained, �������� �������� < 0, shows that resources can be scaled back

To work this out we can create two formulas, a linear and exponential:

Linear formula:

This could be labelled as �������� where ���� is the proportional increase to ���� in months.

1 ≤ ����

1 ≤ ���� ≤ 12

This formula is for when resources grow per month.

Exponential formula:

Where: 0% ≤ ���� ≤ 100%

Then if we differentiate ������������������������ (����) with respect to ���� :

Our final formula with everything in it is:

We can put this into a word formula to understand what the formula is calculating:

USING THE FORMULA:

STEP 1: SETTING UP THE INTERGRAL

The integral term calculates the contribution of each region to the total resources based on the factors provided:

STEP 2: SOLVING THE INTERGRAL

Now we can deduce fractions for which each region will receive the part of total resources.

=

����2 = 0.00004536 0.00017914 ����3 = 0.00004978 0.00017914

Region 1: 4200 8957

Region 2:2268 8957

Region 3:2489 8957

STEP 3: INCORPORATE THE PARTIAL DERIVATIVE

Let’s assume the total resources are increasing linearly at a rate of 10 units per month (Δ���� = 10).

Rewriting this in words to make it simpler:

If we say that the time period is one month as there will be a need for Instant resources and long-term resources, then:

Finally, with each integral result we can multiply the total available resources with that, to get the total amount of resources per region.

Now we can round the numbers as we can’t have 30.56 cars or food

We must adjust the values so they all add up to the total, so:

31+28+51=110

WHY IS MAKING A FORMULA FOR FAIR RESOURCE ALLOCATION RELEVANT FOR REAL WORLD APPLICATIONS?

Resource allocation is mostly inefficient and as a result, causes wastage. This isn’t sustainable and could lead to shortages in the future. Creating a formula provides a fair and statistical approach based on numbers; this negates unconscious bias and any other factors affecting fairer decision making. Money, time, workforce and resources are often limited, a formula can help optimise their distribution and where they will make the most significant impact. This ensures there is the least amount of waste and the maximal efficiency. There is inequality in the allocation of resources, a formula helps incorporate factors such as population size, urgency, and priority to address the disparities between unequal regions or groups. This topic is mainly affected by cost and risk; factoring these into our formula supports complex decision making which helps in consistency and providing clarity. Dynamic fluctuating situations require flexible approaches to create a solution; a formula allows fluctuating data allowing decisions to be made quicker. By leveraging measurable data and balancing competing priorities, these formulas ensure ethical and impactful resource distribution, promoting sustainable and equitable outcomes across various fields.

WHAT RESOURCES DOES THIS FORMULA APPLY TO AND WHAT DOES IT NOT APPLY TO?

This formula only works for resources that are: quantifiable and divisible. Some examples are funding, medical supplies and food aid. These resources can be allocated in measurable numbers, allowing proportional distribution. It also works for resources that are costly or difficult to transport to different regions, requiring prioritisation based on accessibility, costefficiency and urgency. The formula does not apply to non-quantifiable resources. Some examples are electricity, water and access to clean air. In times of emergencies, it is largely about having a multitude of resources available rather than a specific amount. This makes these unquantifiable and therefore doesn’t apply to the formula.

To conclude “generating a formula for fair resource allocation” allows resources to be distributed efficiently, ethically, and proportionally in emergencies. The hardest factors by far to measure are urgency and efficiency due to it being a nonphysical thing. By using measurable factors such as urgency, efficiency, cost and risk, and applying tools such as integration and partial derivatives, the formula adapts to changing needs over time. This structured approach reduces waste, improves impact, and supports more equal, data-driven decision-making across regions.

ADAM CIRUS, LVI

Angelique was a highly commended runner up in the Howard essay prize. In this piece she explores whether writing in the English language would be enriched if more writers had studied Latin.

For over a millennium, Latin formed the backbone of Western education. From the candlelit monastic schools of the Middle Ages to the silk-robed scholars of Renaissance humanism, students parsed Cicero’s linguistic labyrinths and memorised Virgil’s formidable footfallsrarely without stumbling Even into the twentieth century, Latin remained ubiquitous in English secondary schools. Yet in the past fifty years its place has been eroded by an emphasis on modern languages, STEM subjects, and ‘communicative’ pedagogies that prioritise spoken fluency over grammatical analysis. Given Latin’s proven educational impact, it is essential that Latin continues to be taught because an understanding of even elementary Latin sharpens linguistic insight, enriches syntactic flexibility, and enhances intertextual craftsmanship, ultimately making English prose measurably richer.

Recent initiatives, such as the UK’s Latin Excellence Programme (launched 2022), aimed to reverse the trend of Latin decline; several diocesan trusts taught Latin from ages seven to eleven, reporting gains not only in literacy but in science and history attainment 2. Still, Latin remains largely optional, and its advocates warn that abandoning it risks losing more than vocabulary: its absence unpicks the very tapestry of how we once approached language, structure and narrative.

2 (Times, 2024)