The Pilot

MICHAELMAS

MICHAELMAS

Editorial

Welcome to this term’s edition of The Pilot. As always, we are grateful to Mr Edwin Aitken for his support in sharing some of the outstanding pieces of art that Chigwellians have produced.

FRONT COVER Rosalie Aitken

2. EDITORIAL

2 FLOWERS (WATERCOLOUR + ACRYLIC)

3. ROMANTIC POETRY

6.OSKAR KOKOSCHKA INSPIRED PORTRAIT

Alice Arnold

Angelique Dawson

Verity Moore

7. QUEER RELATIONSHIPS IN ANCIENT GREEK ART Emmeline Lewton

13. PLACE Jagraj Hayer

14. MATHEMATICAL MODELLING AND HUMAN BEHAVIOUR Cindy Yingran Lyu

18. CLASSICAL CIVILISATION COMPETITION – ECHO AND NARCISSUS Teodora Gheorghe

19. REFLECTIONS

Harley Ay

19. CLASSICAL CIVILISATION COMPETITION – ECHO AND NARCISSUS Jasmine Kazim

20. LINO PRINT INSPIRED BY KEIFER AND LOCK

21. BELIEVE ME

24. PLACE

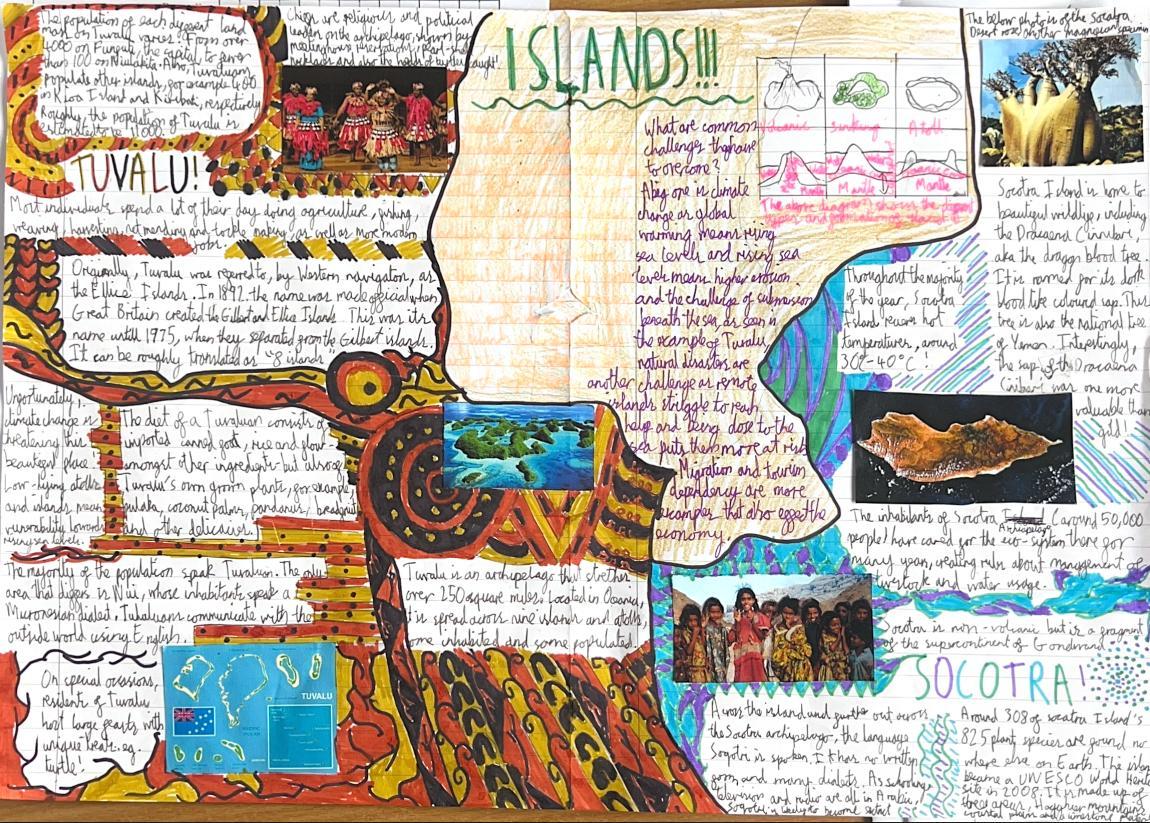

25. YOUNG GEOGRAPHER OF YEAR

Freya Fielding

Ada Nwankwo

Sarah Rehman

Alice Shaw, Maia Lalani, Ruhi Patel, Sienna Cohen

28. LINO PRINT INSPIRED BY KEIFER AND LOCK Zahra Khan

29. THE IMPACT OF GLOBALISATION ON MANGA

34. FLOWERS (WATERCOLOUR + ACRYLIC)

Joseph Rea

Samuel Caseiro

In her EPQ, Angelique explored to what extent Romantic music is more effective than Romantic poetry in conveying character and emotion. Here, she outlines her fascination with some poetry from the Romantic tradition and how it has affected her own poetry writing.

INTRODUCTION:

These poems arise from my fascination with the Romantic tradition, furthered in my EPQ, especially its ability to bind inner feeling to the natural world. I’ve been exploring how external landscapes, night skies, storms, seasons, can become mirrors for private emotion, revealing longing, loss, and transformation in heightened, lyrical form. Each poem is an attempt to inhabit that space where nature and emotion blur, and where silence, memory, and desire gain their own atmospheres.

In developing this small collection, I returned to several canonical Romantic poets whose work continues to shape my understanding of lyric intensity:

• John Keats, particularly “Bright Star” and “To Autumn,” for the way he fuses sensual imagery with emotional stillness and inevitability. His attention to fleeting beauty informs poems like Between the Stars and Silence and A Silent Flutter.

• Percy Bysshe Shelley, especially “Love’s Philosophy” and “To a Skylark,” whose airy musicality and yearning tonalities helped guide the cadence and movement of my lines.

• William Wordsworth’s explorationofmemory andtheemotional afterlifeof pastexperiences, found in poems like “Tintern Abbey", shaped pieces such as Echoes in the Silence, where recollection becomes both anchor and burden.

I was also interested in howRomantic poets elevate natural phenomena (stars, seasons, storms, wind) into emotional agents. In The Undertow of Silence, for example, the incoming tide functions as a metaphor for the collapse of a relationship, an approach deeply rooted in Romantic symbolism. My intention was not to imitate the Romantics, but to carry forward their concern with passion, transience, and the sublime, shaping these concerns through my own contemporary sensibility.

. Between the Stars and Silence

Where moonlight weaves a soft and glowing trail, I wait for you among the trembling blooms. The night breathes low with whispers, soft and frail, While petals catch the light and cast perfumes.

The stars cascade, a map of dreams divine, Their solace shining down eternally. Your words first spark, then soothe, then intertwine, But silence lingers where your voice should be.

Come find me where my tumbling thoughts reside, Where you, and only you, consume my soul, Where you can make the waterfalls subside, Where you can still the chaos; make me whole.

You fell, a hush upon the waiting earth, A silver breath where winsome Winter lay, As if the stars had shaped your soul at birth. A whispered dream that bid the world obey.

You touched my cheek and, for a moment brief, A thrill first froze, then burned, then bloomed within. A warmth enough to chase away all grief, A blaze that made the world around me spin.

Together, time and I, our breath we held. You took my hand and butterflies took flight. Their beating wings, our beating hearts a meld. And so, our journey started with delight.

There was no place for doubt, regret or fear. A single truth resounded on repeat, More certain than the tide, and crystal clear: My life transformed in one pure, fleeting beat

The Undertow of Silence

Dark clouds amassed, eclipsing fragile dreams, As thunder cracked, and light began to fade. Our silence now a shroud of soundless screams, With doubt infecting every choice we made.

The remnants slowly drifted from our reach As turning tides rose higher day by day. The last remaining sands wept on our beach, As finally our love was washed away.

Too many wounds, too many wrongs to right. Our once-harmonic melodies now clash. Did we, too young, ignite a flame too bright? Did passion’s fire turn Eden into ash?

The mundane years unspool with new paths laid, Yet still you roam amidst the dreamtime haze. My nonchalance, a bare-faced masquerade. Your constant absence haunts my empty days.

The Autumn wind surrenders with a sigh, And murmurs all the words we left unsaid. The tender memories always kept nearby, The sorrows left to fade away instead.

A willow shakes, and wakes me in the gloam. I feel the chill where once your warmth had lay. My hollow heart feels torn, and longs to roam, I know I can’t stay lost in yesterday

ANGELIQUE DAWSON, MVITH

In Art, Emmeline is exploring portrayals of divine punishment in Greek mythology. In this excerpt, Emmeline reflects on how Ancient Greek art forms portray Queer Relationships.

Throughout history, queer relationships have been evident in all areas of the world. A queer relationship is defined as a romantic, sexual, or emotional partnership that falls outside of typical sexuality and gender norms i.e. not between a cisgender man and woman. The term ‘Queer Relationship’ can be used to understand emotional, romantic, or sexual partnerships that fall outside of the dominant expectations that stem form cisgender and heterosexual norms. This includes unions between two women, two men, or anyone who’s gender identity or presentation challenges binary standards. In Ancient Greece, from the end of the Mycenaean civilisation in 1200 BCE to the death of Alexander the Great in 120 BCE, queer relationships were documented through various art forms, ranging from paintings to poetry. In particular, vase painting preserved thousands of male pairs, ranging from battlefield camaraderie or embraces clearly romantic in nature. These pieces of art help create a shared viewing experience of homoerotic desire, showing the possibility of intimacy outside of socially traditional relationships. Whilst it can be said that they often reinforced typical social norms by displaying same-sex relationships within accepted cultural roles. They have also helped normalise queer affection by displaying the similarities between queer and traditional relationships, showing they have the same tenderness and complexity. In doing so, the art both acknowledges the ‘otherness’ of queer relationships, whilst also working to subtly normalise them and dismiss the distinctions between queer and heteronormative expressions of live. Art in queer history has always functioned to challenge norms and express identity, as it is a medium through which marginalised identities or relationships could claim space.

In Ancient Greece, relationships between two or more men, were typically because of the system of pederasty. This would be where an older man, referred to as the erasres would lay with a younger man, called the eromenos. These relationships would last until the eromenos reached puberty and could become an erasres himself. This was portrayed through art in a multitude of types of media including murals on walls or painted pottery. Relationships between two men were also heavily depicted through mythology, such as through Achilles and Patroclus, or Apollo and any one of the male lovers he took. Achilles and Patroclus are one of the most well-known duos from Greeks mythology. Homer originally writes the two as friends, with a tender relationship, but it was later deemed pederastic by the Greeks. One of the most famous pieces depicting the two is a piece of pottery, a kylix, from 500BCE depicting Achilles binding Patroclus’ wounds by the Sosias Painter.

The detailed painting shows Patroclus, turned away and grimacing, at the hands of Achilles, who is wrapping a wound for the older man. On the kylix, Patroclus is shown to be unarmoured, in only a cap (a piece of lining to be worn underneath a helmet), with his shoulder plates open. On the contradictory, next to him, Achilles is wearing both his armour and a helmet, rendering Patroclus physically and socially vulnerable next to the younger man. This is furthered by Patroclus’ stance, reclining and partially unbalanced due to one leg being stretched and the other being tucked, this is not a hero-like stance, but rather a private and unguarded state. This vulnerability invites protection, from Achilles in this example, which is a classic erotic trope. This artistic choice creates a power and care role, where Patroclus has been stripped of the protection that defines him as a warrior, leaving him in the care of another man. The imbalance emphasises intimacy, where the stronger, armoured hero is tending to the weaker disarmed beloved. This is heightened by the fact that vulnerability and dependency were coded into male-male relationships consistently throughout ancient Greece through these asymmetries of status and power.

Furthermore, the posturing and proximity on the painting give way to intimate undertones. The two are drawn incredibly near to each other, with Achilles leaning over the older man, which is leaning slightly back with his body arranged in such a way that Achilles’ torso and arms partially overlap him. The sense of intimacy provided by the physical proximity and tender nature of their positions is furthered by Patroclus’ semi-nude form, as not only is he socially disempowered but he is also bodily exposed. Achilles leaning over this form and physically binding his wound creates a scene where touch is prolonged and tender. In typical Greek visual and literary culture, the combination of touch and nudity is used for erotically coded relationships, specifically desire in male pairs. Additionally, to their posture, their positioning also helps to give the painting a sense of intimacy. This is done by the spatial framing of the kylix, where the circular field centres the drama to pinpoint the viewer’s attention. Achilles’ body arcs over Patroclus’ wound, effectively encircling him. This enclosing motion is similar or adjacent in motion to an embrace, allowing the viewer to perceive a sense of protective containment as opposed to typical clinical distance between doctor and patient. Typically, in Greek art, scenes of washing, binding, or tending are recognised to mark affection. As these caregiving gestures are visual metaphors for love and devotion as they imply exclusive or private access to the body and therefore emotional responsibility. So, by Achilles using his hands to tend to and bind Patroclus’ wound shows both. This is supported

by the fact that Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic vase painters often depicted male pairs (e.g. teacher-pupil, comrades, or lovers) in ways that allowed for multiple meanings to be drawn from them. When painters composed two figures with any level of nudity, prolonged contact, or eyeline focus, readers are invited to read any relationship as deeper than being strictly platonic.

This painting is done on a kylix, a drinking cup that would have been used in a symposium, a type of drinking party where male intimacy, storytelling and even eroticised games were common. So, the visuals of Achilles’ tender touch to Patroclus on said cup shows the homoerotic connotations for their relationship. Additionally, because of this it means that the tondo (the circular interior image) would have been gradually revealed at the wine was drunk. This would have meant that the viewer’s gaze was drawn slowly towards the moment of intimacy, the performative nature of the viewing context adds a layer of sensuality to the piece.

Additionally, Harmodius and Aristogeiton, better known to some as the Tyrannicides for their joint assassination of a tyrant’s brother, were two male lovers in Classical Athens. Like Achilles and Patroclus, the two’s relationships is an example of pederasty, with Aristogeiton as the bearded erasres and Harmodius as the youthful eromenos.

The most famous art piece depicting the two is a sculpture, cast in Bronze, of the two. The first version was commission from the Sculptor Antenor following the establishment of the Athenian democracy after the lovers killed Hipparchus. This sculpture, originally created in 476 BC, displays the intricacies of sculpture from the early classical era. The positioning of the two, with Harmodius lunging forward with his arm raised, and Aristogeiton following closely behind him, creates a display of bodies that demonstrates harmony and unity as they move in sync. It shows a sense of trust between the two men as they trust each other to cover their weak spots/ vulnerable areas. The pairs bodies seem to be harmonised in both motion and rhythm, which creates a visual equality or balance that is unusual in Greek depictions of lovers. Here, the power dynamic between the eromenos and erastes collapses, instead showing a mutual agency between the two men, both of them

acting and striking. They also both physically embody the Athenian ideal, with defined musculature, limbs pulled taunt, and both in contrapposto, suggesting movement frozen at its most charged point. This reimages the statue to show the harmony and balance between the two, representing more than their physical consonance but also the intimacy between the two men. Altogether, instead of the typical asymmetry in depictions of pedastry, it shows shared purpose and embodied virtue.

The physical intimacy of the two men allows for the viewer to read the work as more than just a celebration of political heroism and activism but rather a display of the two’s unity. The encapsulating positioning and corresponding energy between the two men suggest a strong physical and emotional interdependence between the two, relying on each other to cover each other's backs when poised for battle. The two were not simply political assassins but lovers, their relationship, though framed within the pederasty system, was seen as the very source of their courage, their affection linked to their virtue and acts. This piece intertwines their legacy as political heroes with their affection and love for each other's, showing their loyalty not only to their people and country, but also to each other.

However, Ancient Greek art portrayed other queer relationships outside of just those between men. There are multiple instances of romantic, sexual or intimate relationships being shown between two women.

The above image shows a scene depicting two women reclining together, with one leant over the other, who tends to a bird. It’s a smaller section on an epinetron by the Eretria Painter, dating to around 420 BC, with a sculpted female bust attached at one end. The scene shows

several women in a gynaikonitis, which in ancient Greece was a portion of or a building entirely dedicated to women, lounging, with the two most central figures tending to each other. Overall, the composition, positioning and gestures of the two women allow for it to be read as subtly homoerotic. The placement of the four women draws attention to the centremost women, as both of the women on the outside are facing inwards towards them. This effect is furthered by the empty space around them, whilst a large portion of the depiction is cluttered with objects and background, the area around them is largely blank. The seated woman, Hippolyte, with her attention turned towards the bird on her hand is being leaned over by the woman behind her, Asterope, her body protectively bent over the seated woman. This positioning is significant as it shows vulnerability and trust between the two, proclaiming their closeness. It’s also a mimic of the positioning used in Ancient Greek art to show erotic nature or closeness between two men, where one man is vulnerable and seated, but the other is more stable and leant over them, a good example being in the aforementioned kylix depicting Achilles and Patroclus.

Asterope’s torso is angled towards Hippolyte, her head dipped and arms outstretched, this not only shows the viewer that she is relaxed, but it also shows their proximity is purposeful. Her body, diagonal, interrupts the painting, as it mainly consists of vertical lines, such as those in the background columns. The woman sitting balances this out, with torso curve over and forward, giving room for the woman to lean over her and into her space. The reciprocity between the two, their two bodies revolving around each other whilst the other women watch suggests an intimacy shared between the two that can’t be shared with the others. The seated woman has her attention focused on the bird sitting on her hand, a sparrow, which are regularly depicted in pieces revolving around eroticism between two women. In Song 1, a poem written by Sappho, the word strouthoui (meaning sparrows) is used, and the piece begins by speaking of their flight. On top of this, birds in women’s scenes were often used to symbolise desire, companionship and softness, throughout history acting as substitutes for expressions of love that couldn't have been depicted outright. Asterope has her hand placed over Hippolyte’s shoulder, resting on her breastbone in a mannerism that is tender. This is a tender embrace from behind, not a labour nor necessity, but rather an act of affection or closeness. She is not tending to Hippolyte’s clothing or preparing her, as there are no tools or objects in her hand, the gesture is just one of affection. The woman on the right of the two, Alcestis, watches onwards, reclined backwards with a hand raised to her cheek, only helps to further serve the idea of intimacy. As her pose is not one of indifference, but contemplation or observing playfully, as said by Gregory Nagy, (an American professor, specializing in archaic Greek poetry at Harvard). This is furthered by the woman on the fair left, who tends to a decorated Epinetron, she counterbalances Alcestis, giving the two privacy within the room. This further develops the sense of intimacy between Hippolyte and Asterope as it shows that their connection is both something private whilst also being playful or sweet.

The picture the Epinetron is setting is one of romance, Alcestis is the bride as this is a wedding piece, suspected by the CARC (classical art research centre) to be a celebratory vase of the wedding, most likely deposited in a grave as an heirloom of the bride. The scene takes place in a gynaikonitis, a woman only space, typically associated with textile work or intimate conversations and the social lives of women privately. They were known to provide spaces that were culturally acceptable for relationships between women. The viewer is brought into this private space, privileged to a moment of female intimacy. The placement of the emotionally charged scene in all of its tenderness allows for the viewer to read it with an idea of desire that wouldn't be viewed by the public.

Because homoeroticism was rarely formalised of acknowledged publicly, desire between women couldn’t be presented as openly. Where male homoeroticism has recognised social structures, found in the system of pedastry, Sapphics (women interested in other women) had to express affection in other means, like poetry. The most notable poet to fall into this category being Sappho. Sappho of Lesbos is thought to be the most significant ancient Greek voice expressing desire between two women, perhaps one of the most well-known across all time periods.

One of her best-known pieces, Fragment 31, was written on the island of Lesbos in the late 7th century BC. The poem depicts a woman becoming overwhelmed by the presence of another woman, who she loves, and then having an intense reaction when she sees her talking to a man. One of the most striking things about this poem is its use of physical language to express her reaction. Whilst describing her reaction to the other woman, she uses phrases that have been translated to the likes of “cold sweat comes over me” and “a subtle fire has run over my skin”. According to Andre Lardinois, the vocabulary used is the type from the classical eros – typically described a man’s longing for a woman, but Sappho has used it to describe her own longing for another woman. She uses pre-established depictions of romance and intimacy to convey her own same-sex attraction.

EMMELINE LEWTON, MVITH

Cindy entered the Marshall Society Essay Competition exploring to what extent mathematical modelling can capture the complexity of human behaviour.

The Classical Civilisation Myth Competition: Echo and Narcissus.

This competition asks students in year 7 and 8 to produce a creative response to a myth. This year, Yasmin and Eddie produced pieces of art inspired by the myth and were highly commended. The year 7 winner of the competition was Teodora with her art, below. The year 8 winner was Harley Ay who wrote a poem inspired by Echo and Narcissus.

As I reflect in my obsession, Unaware that my cruelty reaches far, I do not hear your pain, Your sorrow or your breaking heart.

Your words; they do not reach me, they echo in the air, You lose yourself, Your love unrequited, my vanity ignited.

My only true love reflected, It stares back at me unrejected, My attention, unwavered, ready, obsessive, My pride won’t allow me to accept this could be tragic.

My end is not joyous, My body consumed, It is the loss of us both, On different sides of narcissist rule.

HARLEY AY, IVTH

In this piece of creative writing, inspired by the Robert Browning monologue, My Last Duchess, Ada gives the Duchess a voice.

Believe me, the people sparkled that night. It was a gala- a masquerade ball. The string quartet by the bay window played the haunting overture which thrummed through the ballroom as the shadows of costumed revellers stretched onthewall byflickeringcandlelight. I watched you first, from the room’s periphery; marvelled at how you beckoned the waitstaff by just looking at them. I yearned for the power you exuded in a simple motion. The status in a look. I wanted to be wanted by you. I made sure to be in your line of sight that night. I made sure that you could find me. And find me you did. You sought me out, hovering near me, and stealing me away in a silent exchange. Like the shadows on the walls, the night seemed not to end. I was a butterfly that night- beautiful, fragile, foolish- and you wore the mask of a spider. You led me to a starlit conservatory where we sat and, oh, the webs you spun; the nectar that seemed to drip off of your tongue when you spoke- I lapped it up. You spoke of the Masters of Art, of your education in Sicily, of your passion for collecting things; and this scam, this con, this wicked trick of the heart, I fell for it. I revelled in it as you sealed it and called me ‘La mia farfalla’ - your butterfly, and my heart fluttered. Just to be yours, that was enough. The pretty little patterns in the webs you spun me, I relished the way they blinded me, and they ensnared me.

In the weeks leading up to the wedding, I heard rumours. High society spoke of the women before with the sort of dismissive pity I vowed would never be associated with my name. How wrong I was. I felt the looks and the judgement, though you had a funny way of making me forget. With nectar and silk and spices and incense, and little affections here and there. I was in a haze, comatose with your adulation. Between your travels, I would have done anything for just a morsel of you. I would have eaten myself alive for just a taste of the silk and the syrup that you whispered in my ear that first night. I remember the first night you returned from some far-off New World. The first time you raised your voice at me. Over a table setting. Over all things, a utensil out of place. I cried for hours that night. I wasn’t sure what I had done wrong. Nor how I could have made it any better than I had. But when you apologised, when you spewed that silk and honey, all over again, all was forgiven.

On the evenings we were surrounded by noblemen, powerful people and their submissive wives, you held me tighter, and you seemed to put on a show for them. Entertained them with hints of our love. An audience I was a part of. It was as if you held back until we had a suitable crowd. We weren’t

art- but we were a close forgery. That was what I realised one night, as you boasted raucously at the head of the table, in the Great Hall and I sat by your side, silent and smiling passively, as if one of the many dolls you had imported for me. That we were an exhibition. And that would make me your trophy; your gem. An artifact. I was a pinned butterfly, stuck under glass as taxidermy. And artifacts don’t get real love...Maybe at the start they do, but beautiful things are to be admired, casually spectated at a distance, but never truly understood. Maybe that was why, as the calendar drew away from the cool summer evening that we met, you drew away from me also. The trips grew longer, the spells of time at home grew shorter, and I grew lonelier.

You gave me enough affection to keep me docile, but I was malnourished. I was starved, having grown reliant on the large bouts of attention I was once offered, and for those next few months, I lived in a state of constant and total withdrawal.

The grip your web of words had on me only tightened, those next few months, and like a butterfly in a spider’s trap, the more I struggled, the more stuck I became. You’d give me the basest and most basic of compliments, or a simple smile, and like a fool, I’d fly back in happily. Even if you’d leave me again straight after- even if. I’d place the nails in my own wings and would lie obediently on my plinth, content to be your artifact. It seemed to me, artifact was better than nothing. But when you get so used to that constant state of playing roulette with your joy, you yearn not for love, but consistency. That was what I truly wished for.

And then the painter came.

If you were a spider, then the painter was a flower. And if you were me, then you’d understand that he was a breath of true air. His compliments were easy- kind words blossomed from his lips like water from a waterfall; I had only ever had drips of your nectar and this? There was no web, no scheme, no trapnorcon.Hiswordswereneverforgedorrecycled.Theyflowed recklessly.Onlyforme.Andmaybe it was a mirage caused by the famine you had created, or a trick of the light, but it felt like I had found a new source. A new supplier for my validation. An escape from the insistence of your grip on me. So of course I smiled. Of course I blushed over his praise. And of course, I began to flap my broken wings, wounds and all. I don’t think it was love- he pitied me. But it was something that could not be forgedand you only ever dealt in forgeries, you see. Maybe I thought that you would fight for me, when challenged, but all I received was the austere defiance of a man who simply didn’t care anymore.

It wasn’t love, but the painter opened my eyes. I needed people; the workers in the vineyards, scullery cooks, gardeners, to fill a gaping wound that the harshness of diamonds only increased. I was no longer the same butterfly you had chosen that night. You had ripped her fragile wings, watching the sinews tear as she struggled and resisted; and surrendered. She was lost to you that day, and I knew I had to leave. Anywhere but where I lived dose to dose, moment to moment, never knowingwhen you might snap. My wings were like cardboard, but my resolve was steel: I was leaving that night. I would become the lost Duchess. The artifact that stole itself. I crossed the garden barefoot, in only a nightgown against the dank Italian winter. I flapped and flapped down that set of stone steps, but you were closing in. You knew, somehow, you knew.

I heard that same haunting overture from the night that we met, felt your presence hovering above. I tasted nectar as you called me from the steps of your castle, but it was bitter now and soured with each step you took towards me. The masquerade was ending. Your mask was nearly gone, chipped away at by wear and tear. By every day of constant use, save the occasional crack. It had exhausted you. But for me to be yours forever? Easier, I suppose, to entrap me than to chase me. The corrupt furnace where you twisted your steel webs burned as the mask cracked and your clammy palm closed around my neck, and the overture played,louder and louder, as you squeezed tighter and tighter.

I was foolish to fall into your web, but more the fool to think I could escape it.

ADA NWANKWO, UVTH

Students were invited to enter this Young Geographer of the Year competition which, this year, had a focus on islands of the world and the challenges they face. Entrants had to design a poster to explore two different islands.

In his HPQ, Joe explored the effects of the globalisation of Japanese Anime and Manga.

Manga’ is the term used to describe “Japanese comic books or graphic novels with a twist... immersive storytelling through pictures where images rule supreme” (British Museum 2019). However, to fans around the world, manga means much more. In 1902, Rakuten Kitazawa’s manga series ‘Tagosaku to Mokubē no Tōkyō-Kenbutsu’ was published. Selling around 5 million copies in Japan, Kitazawa’s work is credited as the seminal piece of manga which is synonymous with Japan and its traditions. Fast-forward to the present day, and manga (and its moving image form, anime) is no longer the niche art form it once was. One of the fastest growing and most successful industries on the planet, its UK sales more than doubled between 2012 and 2019 with more Gen Zers watching anime than sports such as NFL (Vox Media Survey 2024). It has sent shockwaves through the global media industry, and has redefined perceptions of modern art. However, critics and industry insiders are divided about the impact of its diversifying to attract bigger audiences. Some suggest that manga has lost its uniquely Japanese nature, destroying the appeal of the art form in order to pander to Western sensibilities. The glamorisation of extreme violence and presentation of women, allied to the lack of an authentic exploration of Japanese cultural values and mythologies, are often cited objections to the globalisation of the genre leading Hayao Miyazaki to suggest that ‘almost all Japanese animation is now produced with hardly any basis taken from observing real people’ (Hayao Miyazaki 2017). However, other critics claim that its globalisation is a natural extension of an art form that has always evolved through its creative cross pollination. Moreover, some suggest that the fight to retain creative control is detrimental with Monty Oum (creator of web series RWBY) suggesting that “Some believe just like Scotch needs to be made in Scotland, an American company can’t make anime... [which] is a narrow way of seeing it. Anime is an art form, and to say only one country can make this art is wrong” (Monty Oum - 2013). In this piece, I will explore the impact of the West on manga and anime.

During the Nara Period (710-794 CE), illustrative narrative scrolls called emakimono were created. These scrolls, often considered the origin of manga, were unravelled from right to left, and contained hand-drawn or painted narratives, mostly displaying stories of ancient Japanese folklore and religion, particularly tales of heroism, romance, or the supernatural. However, the term ‘manga’ was not coined until much later – in the Edo Period (1603-1868) - by renowned ukiyo-e artist, Katsushika Hokusai. Unlike emakimono, Hokusai used the term to describe the sketches he made

to record ideas as he imagined them. These doodles, drawn into e-hon, did not follow a narrative arc but were sketches used as an aide memoire. This is evident in the choice of kanji Hokusai used to spell his creation, 漫 (man) and 画 (ga) meaning ‘whimsical drawings.’ Consequently, the earliest forms of manga – both emakimono and Hokusai’s ehon - reveal qualities that remain synonymous with it today: namely, its fantastical visual depictions of the Japanese imagination.

The West’s involvement in the Meiji Restoration and its effect on 19th century Manga

Four years after Hokusai’s death in 1849, US Navy Commodore, Matthew Perry, arrived in Tokyo Bay with a fleet of warships demanding Japan open its borders to trade after 200 years of isolation known as 鎖国 (Sakoku meaning closed/chained country) - a policy designed to bring peace and stabilise the leadership of the Shogunate after a 500-year feudal period. Perry’s arrival marked a pivotal moment in Japanese history giving birth to a new era: the Meiji Restoration – a period synonymous with Japan’s modernisation when “both art and forms of expression were evolving” (Japan Avenue –2021). At this time, manga, as we now know it, came into being which suggests that the West’s influence on Japan was, paradoxically, the catalyst for manga’s growth and increasing appeal.

Part of the West’s impact on manga at this time was the rapid industrialisation it brought to Japan. In 1853, new ports and foreign settlements were established, including in Yokohama where Japan’s first newspapers were printed, including Charles Wirgman’s ‘Japan Punch’ (1862-1887). Inspired by England’s Punch magazine and borrowing its satirical tone, Japan Punch was as popular with Japanese people as Western settlerssince its cartoons satirised Westerners and the difficulties they facedwhile trying to set up commercial and diplomatic relations in Japan. Wirgman’s use of word bubbles in the cartoons influencedmany Japanese artists with the newspaper having “amajor influence on Japanese artists and writers who, at the time, were concerned about Japan’s rapid modernisation, and established similar publications to satirise Japanese government policies” (British Museum –2018). Consequently, the impact of Europeans such as Wirgman and Ferdinand Bigot (editor of the satiricalmagazine Marumaru Chinbun) on theevolution of manga leads some critics to assert thatthe West’s influence on the art form is deeply entrenched at its inception.

However, the work considered by many to be the first ‘real’ manga was not released for another 15 years, in 1902, by Rakuten Kitazawa. Kitazawa was the first person after Hokusai to use the term manga to describe his work leading to him being the first mangaka (creator of manga.) Credited with reviving and professionalising the art form, one of Kitazawa’s most famous pieces was ‘The

Watered Sprinkler,’ which was inspired by a French film about the Lumière Brothers. Later influenced by the Anglo-Saxon Satirical Press, Kitazawa went on to create his own magazine, ‘The Tokyo Puck.’ In this way, although Kitazawa could be argued to be the grandfather of manga, paving the way for all mangaka whofollowedhim,hisinfluences -bothcreativeandtechnological-arehighlyEuropean.

The American occupation brought more American-style comics into Japan, particularly Disney characters such as Mickey Mouse and Bambi, and American Superhero comics. Japanese translations for comics like Superman became available in the early 1950s and acted as new inspiration for mangakas across the country. The impact of the war, especially the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, had wider reaching influences on the development of manga, influences that suggest it is difficult to separate the West’s influence on the art form. An inexpensive form of escapism for a people impoverished and broken, manga became even more popular within Japan. Moreover, it provided mangaka and their readers with a way of exploring the trauma of war. One such mangaka was Osamu Tezuka (1928 – 1989), often dubbed the ‘God of Manga’, who was obsessed with Walt Disney, allegedly watching Bambi over 80 times4 Inspired by Disney’s colourful animation and depictions of human suffering and emotion through allegory, Tezuka produced many successful works, popular both domestically and internationally, most notably his masterpiece, ‘Astro Boy,’ or, in Japan, ‘The Mighty Atom.’ Tezuka trademarked the cinematic feel of modernday manga and anime, viewing from different shots, angles and frames, along with its wide-eyed and expressive characters. First published as manga in 1952, Astro Boy sold 100 million copies worldwide and became the first ever manga with an anime adaptation, first televised in 1959. Likewise, Mitsuyo Seo’s ‘Momotaro: Sacred Sailors’ (1945), which borrows its protagonist’s name from a character in ancient Japanese mythology who grows from a peach and fights ogres to survive, tells the allegorical tale of four animals who join the navy to survive a catastrophic war. Consequently, Tezuka and Seo not only used American animation as inspiration for manga’s evolving artistry and storytelling but also used the art form to tackle the trauma of a country broken by Western aggression.

By the late 1950s, the manga industry was gathering global attention. More comics were written and mass-produced as new manga bookshops appeared around the world; over 30,000 manga rental bookshops existed in Japan by the mid 1950s (A Brief History of Japanese Comics Part 5:

1950’s Gekiga and Children Comics - 2016) However, there remained an imbalance between sales in Japan and the West, often due to criticism regarding its ostensible childishness. In response, mangakas like Tatsumi Yoshihiro became famous by creating a new form of manga, Manga Gekiga, which presented darker, grittier realities. Yoshihiro’s ‘Yurei Taxi,’ (1957), depicts taxi drivers’ encounters with ghostly passengers, many of whom were victims of 2011’s Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. This diversification and the break from the mainstream art form is often considered to be the main reason for anime and manga’s global success. Even now, manga continues to diversify, with more new genres evolving, such as Shonen, Seinen and Shojo. The consumption of anime and manga reached its peak in the late 1990s to early 2000s but digitalisation and the shift from live television and limited broadcast times to streaming services such as Netflix and Crunchyroll, has increased consumption of anime significantly, attracting more people than ever. A Netflix study suggests that over 50% of all Netflix account holders watch anime (Netflix – 2025) implying that the late 90s’ boom will soon be surpassed.

However, with the increasing popularity of manga and anime in the West, many critics and fans suggest that the Western influences that have helped its evolution have equally negative consequences. Concerns have been raised about manga’s themes, characterisation and storytelling becoming Westernised. Franchises such as JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure and Cowboy Bebop blend Western and Japanese storytelling, visual styles and animation, and some believe this causes manga to lose its uniquely Japanese appeal. Furthermore, some Japanese fans worry that the shifting focus on international success may overshadow the preferences of the domestic Japanese audience where studios attempt to make manga and anime with a focus on Western viewers. For example, ‘HakoMari’, ‘Rokka: Braves of the Six Flowers’ and ‘Mx0’ have received extremely negative ratings in Japan – the latter being cancelled due to low sales and reader interest. Critics such as Nic with no K, (youtuber, critic and creator of ‘The Nerdiest Podcast’) have also condemned the practice of foreign localisers and translators taking entire scripts from the manga and changing them to portray Western political views reminding them that “When [they] are a localiser, [their] job is to localise, not change.” An example of this is the English dubbed version of the hit anime series ‘Miss Kobayashi’s Dragon Maid’ where multiple lines were re-written to include contemporary Western gender politics, causing controversy among fans - such as when the female protagonist changes from wearing revealing clothes, ‘because she wants to,’ to covering up because of ‘those pesky patriarchal

societal demands.’ Such ‘adaptation’ creates deviations from characterisation as well as thematic concerns - all in the pursuit of appealing to a Western fanbase.

However, to dismiss modern manga on the grounds of its inauthenticity is to denounce the Western influence with which the industry’s success is predicated. Furthermore, some believe that, rather than removing traditional Japanese elements, the addition of Western aspects leads to ‘Creative Cross-Pollination’ (Flor Guzzanti - 2024) facilitating innovation by mixing different artistic traditions and cultural perspectives. Many extremely successful pieces have come about through this process, such as Studio Target’s ‘Cyberpunk Edge Runners,’ (2022) and Nickelodeon's ‘Avatar the Last Air Bender,’ (2005), with both shows reaching an IMDb score of over 8/10 (IMDb –2025). Furthermore, productions like ‘Spirited Away’ and ‘My Neighbour Totoro,’ centralise Shintoism and kami, Japanese tradition, yokai, and many other aspects of Japanese folklore. Despite being hugely popular in the West, with both films grossing well over 90,000,000 USD at the boxoffice, the films promote Japanese culture and creativity. Additionally, the global popularity of anime and manga has increased revenue: in 2024, the anime industry made 34.2 billion USD and is projected to make around 60.3 billion USD in 2030 with an annual growth rate of 9.8% from 2025 to 2030 (Anime Market Summary – 2025). Rather than decry the impact of globalisation, the revenue from it could be celebrated as a way of promoting creativity and Japanese culture. Moreover, although the issues inherent in localisation cannot be ignored, modern technology such as AI can mitigate against mistranslation and was used in ‘The Ancient Magus’ Bride,’ whichwenton to sell over 12 million copies.

In conclusion, while manga’s globalisation is not without controversy and vigilance is required to uphold its Japanese identity, its Western influences have helped the industry more than hindering it. Manga has always been influenced by the West, and its cultural and artistic crosscreativity is undeniable. Moreover, a resurgence in the popularity of narratives that promote Japanese values such as service, society and anti-capitalism, as seen with works like Spirited Away or My Neighbour Totoro, suggest that concerns about the art form losing its original Japanese values are invalid.

JOSEPH REA UVTH