NINETY-THIRD SEASON

Sunday, May 19, 2024, at 3:00

Piano Series

EVGENY KISSIN

BEETHOVEN

Sonata No. 27 in E Minor, Op. 90

I. Mit Lebhaftigkeit und durchaus mit Empfindung und Ausdruck (With liveliness and with feeling and expression throughout)

II. Nicht zu geschwind und sehr singbar vorgetragen (Not too swiftly and conveyed in a singing manner)

CHOPIN Nocturne in F-sharp Minor, Op. 48, No. 2

CHOPIN Fantasy in F Minor, Op. 49

INTERMISSION

BRAHMS

PROKOFIEV

Four Ballades, Op. 10

No. 1 in D Minor: Andante

No. 2 in D Major: Andante—Allegro non troppo— Tempo 1

No. 3 in B Minor (Intermezzo): Allegro

No. 4 in B Major: Andante con moto

Sonata No. 2 in D Minor, Op. 14

Allegro, ma non troppo

Scherzo: Allegro marcato

Andante

Vivace

This performance is generously sponsored by Martha C. Nussbaum. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association acknowledges support from the Illinois Arts Council.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Symphony Center Presents thank Martha C. Nussbaum for generously sponsoring this performance.

2

COMMENTS

by Richard E. Rodda

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

Born December 16, 1770; Bonn, Germany

Died March 26, 1827; Vienna, Austria

Sonata No. 27 in E Minor, Op. 90

COMPOSED

1814

Though 1814 was one of the most successful years of Beethoven’s life as a public figure—the revival of Fidelio was a resounding success, the Seventh Symphony was premiered to general acclaim, his occasional pieces for concerts given in association with the Congress of Vienna that year were applauded by some of Europe’s noblest personages, his arrangements of Welsh and Irish melodies appeared in Edinburgh, the clangorous Wellington’s Victory became an overnight hit—he produced little in the way of important new compositions during that time: the cantata Der Glorreiche Augenblick, Elegiac Song for Four Voices and Strings, Polonaise for Piano, and the Piano Sonata in E minor

were the only pieces from 1814 deemed worthy of opus numbers. After experiencing a miraculous burst of creativity during the first decade of the nineteenth century, the flood of masterpieces had begun to abate by 1809.

French troops invaded Vienna in May (the rigors of their occupation finally broke the fragile health of the aged Joseph Haydn, who died on May 31), and Beethoven frequently complained that the resultant social, political, and economic turmoil disturbed his concentration—and then went ahead and wrote his Emperor Concerto. His life, though, remained difficult, so much so that his American biographer Alexander Wheelock Thayer called 1810 “a disastrous year.” A pledge made during the previous year by the Princes Lobkowitz and Kinsky and Archduke Rudolph to provide him with a guaranteed annual wage had been diluted by the inflation caused by

from top: Ludwig van Beethoven, portrait in oil by Joseph Willibrord Mähler (1778–1860), 1815. Vienna Museum | Archduke Rudolph of Austria (1788–1831), student and patron of Beethoven and later archbishop of Olmütz (now Olomouc in the Czech Republic). Portrait in oil by Johann Baptist von Lampi the Elder (1751–1830). Vienna Museum Collection

CSO.ORG 3

the French invasion and the inability of Kinsky to uphold his part of the bargain. Money from the English publisher Clementi was long delayed because of Napoleon’s restrictions on international exchange. Beethoven’s deafness was nearly complete, his health increasingly troublesome, and his family seemed to bring him only grief. In a letter of April 1814 written during a fit of despondency to his old friend Dr. Franz Wegeler, he confessed, “If I had not read somewhere that no one should quit life voluntarily while he could still do something worthwhile, I would have been dead long ago and certainly by my own hand. Oh, life is so beautiful, but for me it is poisoned forever.” Looking for domestic comfort, he thought seriously of marriage for the first time in fifteen years, but his proposal to Therese Malfatti, then not even half of his forty years, was rejected. (The thought of Beethoven as a husband threatens the moorings of one’s presence of mind.)

A period of what critic and commentator Michael Steinberg called “postscripts to the heroic decade, postscripts of enormous potency” occurred between 1810 and 1812—Egmont, the Seventh and Eighth symphonies, the Archduke Trio, Quartet op. 95, the song cycle An die ferne Geliebte, the final violin sonata—followed by an almost complete creative silence in 1813. Like silence in a piece of music, however, this was a moment of great significance in Beethoven’s artistic evolution,

a juncture that would later be seen as the turning point in his compositional career that led to the incomparable series of towering masterworks he created during his last decade. The Piano Sonata in E minor, op. 90, his first work in the genre since his op. 81a (Les Adieux) of 1809, is one of the earliest evidences that this transformation was nearing completion.

The E minor sonata was composed in the late summer of 1814 between the revival of Fidelio in May and the convening of the Congress of Vienna in September. The work was dedicated to Count Moritz Lichnowsky, younger brother of Prince Karl Lichnowsky, Beethoven’s first Viennese patron, and seems to have been occasioned by the count’s engagement to one Fräulein Stummer, a singer at the court theater. (The noble Lichnowsky family disapproved of this match with a mere thespian, however, and it took Moritz two more years to bring about the marriage.) Beethoven cast the sonata in two contrasting and fully satisfying movements, which, he wrote to the count, depict “a struggle between head and heart” and “a conversation with the beloved.” Perhaps so. But, more significantly, the unconventional two-movement form, juxtaposition of grandeur and intimacy, harmonic originality, fluency and cogency of thematic development, terseness of expression, lack of overt virtuosity,

opposite page: Frédéric Chopin, detail from an unfinished double portrait with George Sand by Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), 1838

4 COMMENTS

poignant lyricism, seamless absorption of contrapuntal textures, and Germanlanguage performance rubrics mark this sonata as an entry point into the remarkable period of creative renewal and discovery that Beethoven enjoyed during his last decade.

The main theme group of the sonata’s opening movement comprises several germ cells: a broken-off, two-measure fragment that hints of a dance; a quietly flowing phrase; a bold unison motif in rising open intervals; and a downward sweeping scale. The second subject (in the darkly expressive key of B minor), more agitated because of its broken-chord accompaniment, shadows the open-interval motif of the main

FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN

theme but in inversion. The development section superimposes variants of the first two motifs of the main theme upon the broken-chord accompaniment of the second before a full recapitulation of the exposition’s materials brings formal balance and expressive closure to the movement.

The second movement is a rondo structured around what British composer and musicologist Sir Hubert Parry described as “the frequent and desirable returns of a melody of great beauty,” and Hans von Bülow, the eminent nineteenth-century pianist, conductor, and editor of Beethoven’s sonatas, thought that its poetic music perfectly balanced the “prose” of the opening movement.

Born February 22, 1810; Żelazowa-Wola (near Warsaw), Poland

Died October 17, 1849; Paris, France

Nocturne in F-sharp Minor, Op. 48, No. 2

COMPOSED 1841

Contemporary accounts of Chopin’s piano playing invariably refer to the extreme delicacy of his touch, the beauty of his tone, and the poetic quality of his expression, characteristics faithfully reflected in the twenty-one nocturnes he created between 1827 and 1846. Chopin derived the name and general style for these

works from the nocturnes of John Field, the Irish composer-pianist, who spent most of his life in Moscow and Paris. Both composers were influenced in the rich harmonies and long melodic lines of their nocturnes by the bel canto operatic style that was popular at the time, though Chopin’s examples exhibit a far greater depth of expression and a wider range of keyboard technique than those of Field. The introspective moods of the nocturnes pierced to the heart of the romantic sensibility, and along with

CSO.ORG 5 COMMENTS

the waltzes, they were Chopin’s most popular works during his lifetime.

The two nocturnes, op. 48 were products of 1841, the time of Chopin’s greatest happiness with the celebrated woman novelist George Sand, when he was at the height of his creative powers. They were published in Paris later that year and in Leipzig soon thereafter with a dedication to Laura Duperré, who inspired the following beguiling description in the memoirs of the composer’s friend Wilhelm von Lenz:

I always made my appearance [at Chopin’s apartment] long before the hour of my appointment and waited. Ladies came out one after another, each more beautiful than the others. On one occasion, there

FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN

Fantasy in F Minor, Op. 49

COMPOSED

1840–41

The title “Fantasy” in the early nineteenth century usually indicated a piece in the nature of a written-down improvisation, something whose structural divisions did not follow one of the usual formal species and whose character did not allow generic classification among the various dance or pedagogical types. As Chopin’s

was Mlle. Laura Duperré, daughter of Admiral Victor-Guy Duperré [commander of the French forces at the siege of Algiers in 1830], whom Chopin accompanied to the head of the stairs. She was the most beautiful of all and as slender as a palm tree. To her Chopin dedicated two of his most important nocturnes [op. 48]; she was his favorite pupil at the time.

The outer sections of the Nocturne in F-sharp minor, op. 48, no. 2, drape a tender melody upon an arpeggiated background of four-note figures, while the central episode, with its halting gait, provides formal contrast to the smoothly flowing music that surrounds it.

F minor fantasy makes abundantly clear, however, the name does not imply an amorphous meandering. Indeed, Herbert Weinstock called the piece “the crowning formal achievement of romantic piano music . . . Chopin’s greatest single composition.” Though its structure is complex (Weinstock devoted five pages to its analysis), the work is a superb example of Chopin’s unsurpassed ability to perfectly integrate the formal requirements of his materials with the emotional essence of its expression.

6 COMMENTS

JOHANNES BRAHMS

Born May 7, 1833; Hamburg, Germany

Died April 3, 1897; Vienna, Austria

Four Ballades, Op. 10

COMPOSED 1854

A ballad, according to the Random House Dictionary, is “a simple, narrative poem of popular origin, composed in short stanzas, especially one of romantic character and adapted for singing.” The term was derived from an ancient musico-poetic form that accompanied dancing (ballare in medieval Latin, hence ball and ballet), which had evolved into an independent vocal genre by the fourteenth century in the exquisitely refined works of Guillaume de Machaut and other early composers of secular music. The ballad was well established in England as a medium for the reciting of romantic or fantastic stories by at least the year 1500; it is mentioned by Pepys, Milton, Addison, and Swift, often disdainfully because of the frequently scurrilous nature of its content. The form, having adopted a more elegant demeanor, became popular in Germany during the late eighteenth century, when it attracted

no less a literary luminary than Goethe, whose tragic narrative “Erlkönig” furnished the text for one of Schubert’s most familiar songs. Chopin seems to have been the first composer to apply the title to a piece of abstract instrumental music, apparently indicating that his four ballades hint at a dramatic flow of emotions that could not be appropriately contained by traditional classical forms.

It was with this emotionally suggestive but essentially abstract meaning that Brahms applied the term, with one exception, to the four ballades he composed during the summer of 1854; they were published as his op. 10 two years later. The exception is the Ballade no. 1 in D minor, the only one of Brahms’s instrumental works with an overt literary program, which takes as its subject a grim Scottish ballad of patricide, “Edward,” which he knew in a German version from Herder’s collection of folk songs Stimmen der Völker (Voices of Nations). The three remaining ballades have no evident programs. The dominant lyricism of the Ballade no. 2 in D major is contrasted by the drama of its center section. The elfin Ballade no. 3

opposite page: Chopin, watercolor and ink drawing by fiancée Maria Wodzińska (1819–1896), 1836. National Museum, Warsaw, Poland | this page: Johannes Brahms, ca. 1855 portrait, Robert-SchumannHaus Zwickau, Saxony, Germany

CSO.ORG 7 COMMENTS

in B minor, subtitled Intermezzo, serves as the scherzo of the set. The Ballade no. 4 in B major, the largest in scale of

SERGEI PROKOFIEV

Born April 23, 1891; Sontzovka, Russia

Died March 5, 1953; Moscow, Russia

the series, is notable for its warmth of expression and the rich figurations of its inner voices.

Sonata No. 2 in D Minor, Op. 14

COMPOSED 1912

By 1912, just two years before he completed his formal studies at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, Sergei Prokofiev had established himself as a formidable prodigy of both piano and composition and the leading enfant terrible of Russian music. The first work upon which he bestowed an opus number, the Piano Sonata no. 1 of 1907 (he was sixteen), was good enough to win him an association with the prestigious publisher (of Tchaikovsky, among others) Jurgenson. Other compositions for solo piano, voice, and orchestra quickly followed the First Sonata, and Prokofiev’s performance of his own keyboard works established his reputation as a brilliant and powerful virtuoso and a composer in the most daring styles of the day, qualities matched by a fearsome egotism that enabled him to batter his way to critical and public

recognition. The most important of Prokofiev’s pregraduation creations was the Piano Concerto no. 1, which stirred spirited comment, pro and con, when he premiered it in Moscow on July 25, 1912. After playing the concerto again at the garden park in suburban Pavlovsk, he joined his mother at the Caucasian resort of Kislovodsk, where he balanced a rigorous schedule of composition with hiking in the mountains and reading. It was at Kislovodsk in August that he completed the Piano Sonata no. 2, begun the previous March. “Every morning, I go to the local drugstore to work,” he recorded at the time. “There is a good upright piano there, the room is comfortable, no one bothers me, and it doesn’t smell of medicine.” He sent the manuscript to Jurgenson with a note stating that in view of the interest excited by his recent appearances in Moscow and Pavlovsk, a new, higher scale of fees should be instituted. Two hundred rubles, he said, was his price for the new sonata, and he would accept nothing less. Jurgenson met his demand.

above: Sergei Prokofiev, ca. 1918, New York City. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

8 COMMENTS

Prokofiev gave the premiere of his Second Piano Sonata on January 23, 1914, in Moscow as part of a series titled Evenings of Modern Music. Though opinion was mixed, with the young iconoclast’s modernity eliciting strong comments, the prominent critic Y. Engel noted “the sonata’s powerful play of musical ideas, the energy of the creative will; it has a kind of angularity, harshness, and coldness, but at the same time a genuine freshness.”

The sonata opens with a precisely regulated sonata form that traverses a superbly built main theme of high rhythmic tension that rises through a stepwise pattern, a transition of quiet intensity, and a contrasting second subject in the style of a valse triste. A development built from motifs of the earlier themes is followed by a full recapitulation. The compact scherzo, with its central section of ostinato-like octave figurations, is a reworking of a piece Prokofiev wrote in 1908 for Anatoly Liadov’s composition class at the St. Petersburg

Conservatory. The Andante, whose depth of emotion masterfully balances the wit and verve of the surrounding music, is based on two themes. The first, presented after a gently rocking introduction, is a smoothly contoured melody of quiet motion; the second is more animated and wide-ranging. A repeated-note motif is introduced in the movement’s central portion, underpinning the varied repetitions of the two themes that occupy the closing section. The finale is another sonata form (the main theme is impetuous and leaping; the second theme is built from short phrases in longer note values) that recalls the valse triste theme of the opening movement at the beginning of the development section to strengthen the sonata’s overall formal unity.

Richard E. Rodda, a former faculty member at Case Western Reserve University and the Cleveland Institute of Music, provides program notes for many American orchestras, concert series, and festivals.

CSO.ORG 9 COMMENTS

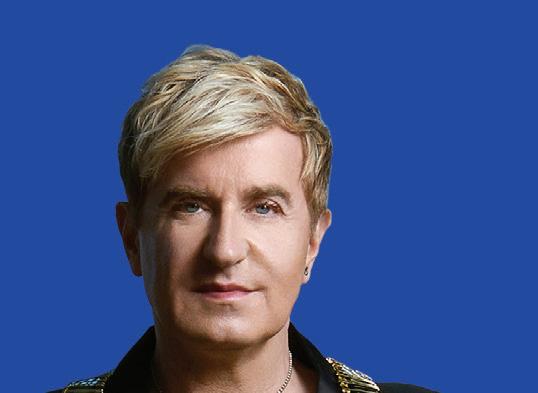

Evgeny Kissin Piano

Evgeny Kissin’s musicality, the depth and poetic quality of his interpretations, and his extraordinary virtuosity have earned him the veneration and admiration deserved only by one of the most gifted classical pianists of his generation and, arguably, generations past. He is in demand all over the globe, appearing with the world’s best orchestras under great conductors, including Abbado, Ashkenazy, Barenboim, Dohnányi, Giulini, Levine, Maazel, Muti, and Ozawa.

Born in Moscow in October 1971, Kissin began to play by ear and improvise on the piano at age two. At six years old, he entered a special school for gifted children, the Moscow Gnessin School of Music, where he was a student of Anna Pavlovna Kantor, who was to remain his only teacher. At ten, he made his concerto debut playing Mozart’s Piano Concerto K. 466 and gave his first solo recital in Moscow one year later. He came to international attention in March 1984 when, at age twelve, he performed Chopin’s piano concertos 1 and 2 in the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory with the Moscow State Philharmonic under Dmitri Kitayenko. This concert was recorded live by Melodia, and a two-LP album was released the following year. Given this recording’s astounding success, Melodia released five more LPs of

live performances in Moscow over the next two years.

Kissin’s first appearances outside Russia were in 1985 in Eastern Europe, and his first tour of Japan in 1986. In December 1988, he performed with Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic in the internationally broadcast New Year’s concert. In 1990 Kissin made his first appearance at the BBC Promenade Concerts in London and made his North American debut, performing both Chopin piano concertos with the New York Philharmonic, conducted by Zubin Mehta. The following week, he opened Carnegie Hall’s Centennial season with a spectacular debut recital, recorded live by BMG Classics.

This season, Evgeny Kissin returns to tour the United States with a recital program that includes the works of his beloved Chopin, Beethoven, Brahms, and Prokofiev. He also collaborates, for the very first time, with the baritone Matthias Goerne, touring Europe and the United States with a program of songs and piano pieces by Brahms and Schumann’s masterful song cycle Dichterliebe. He also appears in concert with major European orchestras, including the Berlin Philharmonic, Gewandhaus Orchestra, and the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, among others.

A recipient of numerous international awards, Evgeny Kissin received the Crystal Prize of the Osaka Symphony Hall for the Best Performance of the Year in 1986. In 1991 he received the Musician of the Year Prize from the

10 PROFILES

PHOTO BY MASCIA SERGIEVSKAIA

Chigiana Academy of Music in Siena, Italy. He was special guest at the 1992 Grammy Awards ceremony, broadcast live to an audience estimated at over one billion, and three years later became Musical America’s youngest Instrumentalist of the Year. In 1997 he became the youngest-ever recipient of Russia’s prestigious Triumph Award for his outstanding contribution to Russian culture. Kissin has been awarded an honorary doctorate by the Manhattan School of Music; the Shostakovich Award, one of Russia’s highest musical honors; an honorary membership of the Royal Academy of Music in London; and an honorary doctorate of letters from the Hong Kong University.

Kissin’s newest release is an album featuring sonatas by Beethoven on the Deutsche Grammophon label. His previous recordings have received numerous awards and accolades, having

contributed significantly to the library of masterpieces recorded by the world’s greatest performers. Past awards include the Edison Klassiek in the Netherlands and the Diapason d’Or and the grand prix of La Nouvelle Académie du Disque in France. His recording of works by Scriabin, Medtner, and Stravinsky won him a Grammy in 2006 for Best Instrumental Soloist. In 2002 Kissin was named Echo Klassik Soloist of the Year. His most recent Grammy for Best Instrumental Soloist Performance (with orchestra) was awarded in 2010 for his recording of Prokofiev’s piano concertos nos. 2 and 3 with the Philharmonia Orchestra, conducted by Vladimir Ashkenazy. His extraordinary talent inspired Christopher Nupen’s documentary film Evgeny Kissin: The Gift of Music, released in 2000 on video and DVD by RCA Red Seal.

CSO.ORG 11 PROFILES