25 26 SEASON

We’ve

25 26 SEASON

We’ve

We’re honored they’ve done the same for us.

Ranked

We believe the connection between you and your advisor is everything. It starts with a handshake and a simple conversation, then grows as your advisor takes the time to learn what matters most–your needs, your concerns, your life’s ambitions. By investing in relationships, Raymond James has built a firm where simple beginnings can lead to boundless potential.

ONE HUNDRED THIRTY-FIFTH SEASON

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

KLAUS MÄKELÄ Zell Music Director Designate | RICCARDO MUTI Music Director Emeritus for Life

Thursday, December 18, 2025, at 7:30

Friday, December 19, 2025, at 1:30 Saturday, December 20, 2025, at 7:30

Klaus Mäkelä Conductor

Yunchan Lim Piano

CHIN

subito con forza

First Chicago Symphony Orchestra performances

SCHUMANN Piano Concerto in A Minor, Op. 54

Allegro affettuoso

Intermezzo: Andantino grazioso—

Allegro vivace

YUNCHAN LIM

INTERMISSION

WIDMANN Con brio, Concert Overture for Orchestra

First Chicago Symphony Orchestra performances

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 7 in A Major, Op. 92

Poco sostenuto—Vivace

Allegretto

Presto

Allegro con brio

These concerts are generously sponsored by Zell Family Foundation. Bank of America is the Maestro Residency Presenter. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association acknowledges support from the Illinois Arts Council.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra thanks Zell Family Foundation for sponsoring these performances.

Born July 14, 1961; Seoul, South Korea

Suddenly with power. Beethoven often used this expression marking in his music, always writing it in Italian: subito con forza.

It is also the title that Unsuk Chin picked for her brief tribute to Beethoven, written to celebrate the 250th anniversary of his birth in 2020.

Chin, who was taught to read music by her father in her native Seoul, South Korea, and grew up intent on becoming a concert pianist, was drawn to Beethoven’s music early on, particularly after she began to compose music herself. “He was always looking for new directions,” she has said. “He was the first consciously modern composer, in the sense that every piece asked for original solutions, even if this meant breaking through existing forms.” For Chin, who has become one of our boldest, most restless, and inventive composers, that is also something of a mission statement for her highly acclaimed catalog of work. When she won the 2004 Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition, music’s most prestigious honor, for her Violin Concerto, the judges cited her “synthesis of glittering orchestration, rarefied sonorities, volatility of expression, musical puzzles, and unexpected turns.”

“What particularly appeals to me,” Chin has said of the quality in Beethoven’s output that inspired subito con forza, “are the enormous contrasts: from volcanic eruptions to extreme serenity.” She could be speaking of Beethoven or of her own artistic aesthetic. Subito con forza is a study in the kinds of quicksilver changes and dramatic shifts that regularly set Beethoven’s music apart from that of his contemporaries and that also dot the landscape of her own output, which is often driven by rapid changes in texture or tempo or mood. “Without inner conflict,” she once said, “I am nothing.”

In subito con forza, Chin begins with Beethoven: the stern unison C that opens his Coriolan Overture. And she writes for his standard orchestra—pairs of winds and brass (without trombones or tuba), with timpani and strings—but she augments it with a large,

COMPOSED

2020, revised May 2022

FIRST PERFORMANCE

September 24, 2020; Amsterdam, the Netherlands; Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Klaus Mäkelä conducting

INSTRUMENTATION

2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, percussion (vibraphone, crotales, cymbals, tam-tams, triangle, snare drums, tambourine, gongs, xylophone, marimba, tubular bells, whip, guiro), piano, strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME

5 minutes

These are the first Chicago Symphony Orchestra performances.

Unsuk Chin onstage at the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s Seoul Festival featuring a new generation of Korean composers, June 3, 2025. Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

modern-day battery of percussion instruments and the sound of the piano, the instrument that first brought Chin to Beethoven’s music. In the short span of subito con forza, Chin references Beethoven’s own music—the iconic opening of his Fifth Symphony, the piano flourishes in the Emperor Concert—within the modern soundscape of her own language. There is both the jolt of the contrast between the two disparate musical worlds and the continuity of fierce originality that characterizes both composers, writing more than two centuries apart.

Chin was struck by something Beethoven wrote in the conversation books he kept at hand so that he could communicate with visitors as his hearing left him: “Dur und Moll. Ich bin ein Gewinner.” (Major and minor. I am a winner.)

“Beethoven’s struggle to communicate and his hearing loss frequently resulted in an inner rage and frustration,” she says, recognizing the duality and the violent changes that drove his music more and more. “It profoundly and poignantly speaks of something fundamental about the human condition.”

ROBERT SCHUMANN

Born June 8, 1810; Zwickau, Saxony, Germany Died July 29, 1856; Endenich, near Bonn, Germany

When the eighteen-year-old Robert Schumann began his piano studies with Friedrich Wieck in 1828, his teacher’s daughter Clara was just nine and already a prodigy. Perhaps she peeked in on her father’s lessons as Robert played Johann Hummel’s A minor concerto, his first assignment. Eighteen years later, Robert Schumann would unveil his own A minor piano concerto, played by his young bride, the same Clara, now grown up and a major talent. We wouldn’t know from this effortless and exuberant music that their wedding in September 1840 met with her father’s fierce disapproval, or that Schumann had been struggling to write a concerto for nearly twenty years.

As early as 1827, Schumann’s diary mentions the “beginnings of a piano concerto in F minor.” That piece was completed in 1830 in a version for

piano alone and published as his op. 1, the Abegg Variations (named for the young woman who held Robert’s affections before Clara). There’s evidence of work on another piano concerto, in D minor, the year before his marriage to Clara. Then, secure in the strength of his love and following an extraordinary outpouring of song in the months surrounding his wedding, Schumann dashed off a fantasy in A minor for piano and orchestra—a one-movement work written in little more than a week. Clara played through the piece at a reading rehearsal in the Leipzig Gewandhaus in August 1841. (She gave birth to their first child, Marie, barely two weeks later, establishing the balance of career and family she would maintain for many years.)

The first year of his marriage was a remarkably productive period for Schumann— within a matter of weeks he wrote his first two symphonies, began other orchestral works, and turned his attention to opera and then

this page: Robert Schumann, daguerreotype portrait by Johann Anton Völlner, 1850. Hamburg, Germany | opposite page : Clara (1819–1896) and Robert Schumann, also by Völlner, 1850. Hamburg

chamber music, while the fantasy sat on a shelf, unpublished, for some time. In the summer of 1845, Schumann composed a rondo-finale and a middle movement to go with the fantasy to complete the piece we now know as his Piano Concerto in A minor. Clara gave the first performance of the concerto at the Leipzig Gewandhaus on New Year’s Day, 1846. This A minor concerto owes a debt to the concertos by his contemporaries Hummel and Ignaz Moscheles rather than to the classical Viennese models of Mozart and Beethoven. Schumann calls it “something between symphony, concerto, and grand sonata.” It’s not any of those, but an extensive work for piano solo with an indispensable orchestral commentary. Schumann ignores the powerful drama and delicate balance of orchestra and piano favored by Mozart and Beethoven—his orchestration is conveniently transparent, allowing the spotlight to fall on the piano in the opening measures and never shift thereafter. The concerto reflects the ebullient, unforced lyricism that marks Schumann’s work at its best. It is, in the admiring opinion of the often-stodgy nineteenth-century British critic Donald Tovey, “recklessly pretty.”

Although it relies on sonata form, the first movement was written as a fantasy, not as the opening of a concerto, and so it doesn’t feature the double exposition (one for orchestra alone, another in which the solo joins) common to early nineteenth-century concertos. It opens with a flamboyant piano flourish that establishes the prominence of the piano solo and continues with a plaintive four-note descending motif that will tie all three movements together. Although this is essentially the same motif often associated with longing and farewell in the music Schumann composed around this time, here it finds a home in one of the sunniest, most untroubled works ever written in a minor key.

The texture is a tapestry of brilliant, endless filigree in the piano part woven with the strong strands of melody that emerge in other instruments. Eventually, after a grand orchestral outburst, the piano ventures

COMPOSED

1841 (first movement)

1845 (movements 2 and 3)

FIRST PERFORMANCE

January 1, 1846; Leipzig, Germany. Clara Schumann as soloist

INSTRUMENTATION

solo piano, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings

APPROXIMATE

PERFORMANCE TIME

31 minutes

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

February 23, 1892, Auditorium Theatre. Maude Quivey as soloist, Theodore Thomas conducting (1. Allegro affettuoso)

April 19, 1893; Old City Hall, Pittsburgh. Fannie Bloomfield Zeisler as soloist, Theodore Thomas conducting

April 22 and 23, 1898, Auditorium Theatre. Laura Sanford as soloist, Theodore Thomas conducting

July 3, 1937, Ravinia Festival. José Iturbi as soloist, Sir Ernest MacMillan conducting

MOST RECENT

CSO PERFORMANCES

July 18, 2013, Ravinia Festival. Jorge Federico Osorio as soloist, James Conlon conducting

May 19, 20, 21, and 22, 2022, Orchestra Hall. Kirill Gerstein as soloist, Karina Canellakis conducting

CSO RECORDINGS

1959. Byron Janis as soloist, Fritz Reiner conducting. RCA

1960. Van Cliburn as soloist, Fritz Reiner conducting. RCA

1967. Artur Rubinstein as soloist, Carlo Maria Giulini conducting. RCA

into the unexpected key of A-flat to meditate on the first motif, now as expansive and eloquent as a Chopin nocturne (Schumann had already done an outright Chopin imitation in his great solo piano work, Carnaval). After a fairly standard recapitulation, the piano gathers momentum and plays on, right through music designed for orchestra alone, into a grand, written-out cadenza. Finally, orchestra and piano join forces in a snappy version of the main theme, which retreats into the distance until the bold, cascading final cadences. The entire movement, despite its headlong manner, is characterized by subtle shifts in color, frequent mood-swings, and the nuanced language of a true poet.

The brief slow second movement—an intermezzo between two powerhouse chapters— begins with halting exchanges between piano

Born June 19, 1973; Munich, Germany

and orchestra, like the careful conversation of new acquaintances, that soon opens into a lively, lyrical dialogue. The piano writing is pointed and eloquent, the orchestration magically restrained. After ghostly reminders of the concerto’s opening four-note motif, the full force of the finale’s rondo theme takes over without pause.

The finale has nearly a thousand measures of music, but it flies by as one coherent, nearly breathless statement. In addition to the boldly assertive rondo theme itself, Schumann tosses out a number of felicitous, rhythmically playful melodies, until the piano launches a long, propulsive coda—a dazzling display of pianistic virtuosity and compositional ingenuity, a pure demonstration of Schumann in his highest spirits—that seems almost unwilling to bring such exuberance to an end.

The simple directive Allegro con brio introduces some of the most extraordinary pages in Beethoven’s output: the opening of the Waldstein Sonata, the Third and Fifth symphonies—and the beginning of the finale of the Seventh Symphony that closes this week’s program. It is also the initial expression marking in Unsuk Chin’s subito con forza that opened this concert. That single word brio—Italian for energy, spirit, liveliness— carries the fast pace of a conventional allegro, the most familiar term in all of classical music, into a world of an unusually charged atmosphere.

Widmann wrote the concert overture he calls Con brio to open a program of Beethoven’s Seventh and Eighth symphonies given by the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra in 2008. It was Mariss Jansons, the conductor of the program, who asked him if he could find a way to write a piece that somehow referenced the Beethoven scores. “My Beethoven references start with the instrumentation,” Widmann said at the time, “which is

FIRST PERFORMANCE

September 25, 2008; Munich, Germany

INSTRUMENTATION

2 flutes (both doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME 12 minutes

These are the first Chicago Symphony Orchestra performances.

very special in these symphonies. He doesn’t have four horns or trombones the way he does in the Ninth Symphony. No, Beethoven makes this incredible ‘noise’ with just two horns, two trumpets, and timpani.” Widmann believes that it is precisely this limited instrumentation that gives these symphonies such concentrated power. “You compose differently if you have more choice,” he says.

As a musical child, Widmann hung a picture of Pierre Boulez on his wall; his sights were already set on becoming part of the challenging world of new music. Widmann grew up in a seriously musical family; he remembers going to see Weber’s opera, Die Freischütz, at an early age and listening to his parents play works by Haydn in their amateur string quartet. At the age of seven, he began to play the clarinet, on which he loved to improvise. But that led him to composition: “The reason why I started composing was that I was so angry with myself that I could not remember the beautiful moments of the improvisation of the day before,” he told the New York Times. “I had to find a way to notate it.” While he was still technically a clarinetist and not yet a composer, he studied composition with some of the biggest names in the business—Wolfgang Rihm, Hans Werner Henze, and Heiner Goebbels. (He eventually met and got to know Boulez.)

something that I feel very comfortable with: the idea of continuing because you love the music and its history so much.”

From the beginning, Widmann’s music, for all its experimental and even wild gestural quality, is a child of the past. His works have always found a way to exist in the space between the standard repertory and experimental contemporary composition. He points to Arnold Schoenberg— whose music resembles his not at all—who created a revolutionary new tonal system out of his profound understanding of music history. “The assumption that is inherent in that is

Beginning with its title, Con brio is indebted to Widmann’s love of music history. Con brio opens with a disjointed sequence of crisp, grand chords, like those that open Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony. “I don’t quote a single note,” Widmann says of Con brio. “It’s more about the gesture.” The entire score has a Beethoven-like spirit, and it is filled with Beethoven-like ideas, which Widmann treats with the kind of playful, kinetic, cheeky, and daring abandon that colors so many of Beethoven’s own fast movements. (In one of the performance instructions that prefaces the score, Widmann says “The metronome markings are deliberately selected at a fast speed to underline and encourage the ‘con brio’ character of the work.”) Con brio is Beethovenian in spirit and character, but Widmann is no mere traditionalist. This is music that translates the kinds of gestures that govern Beethoven’s work into our twenty-first century language. It is music that could only have been written in the past few years. But it is music that could not exist without the enduring and inspiring example of Beethoven.

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

Born December 16, 1770; Bonn, Germany

Died March 26, 1827; Vienna, Austria

Here is what Goethe wrote after he first met Beethoven during the summer of 1812:

His talent amazed me; unfortunately, he is an utterly untamed personality, who is not altogether in the wrong in holding the world to be detestable, but surely does not make it any more enjoyable either for himself or for others by his attitude.

We’re told that the two men walked together through the streets of Teplitz, where Beethoven had gone for the summer, and exchanged cordial words. When royalty approached, Goethe stepped aside, tipping his hat and bowing deeply; Beethoven, indifferent to nobility, walked on. This was a characteristic Beethoven gesture: defiant, individual, strongly humanitarian, intolerant of hypocrisy—and many listeners find its essence reflected in his music (although it is curious that throughout his life Beethoven clung to the “van” in his name because it was so easily confused with “von” and its suggestion of lofty bloodlines).

Beethoven’s contemporaries clearly thought he was a complicated man, perhaps even the utterly untamed personality Goethe found him to be. It is hard to know what Goethe thought of Beethoven’s music—his taste in music in general was far from advanced—but the general perception of Beethoven’s output at the time was that it was as unconventional as the man himself. This is our greatest loss today, for Beethoven’s widespread familiarity has blinded us not only to his visionary outlook (so far ahead of his time that he was out of fashion in

this page: Ludwig van Beethoven, copper engraving by Blasius Höfel (1792–1863) after a drawing by Louis René Letronne (ca. 1790–1848), 1814 | opposite page : The Incident at Teplitz, oil on canvas. Beethoven and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) encounter members of the Austrian imperial family while on a walk in the spa town of Teplitz (now Teplice, Czech Republic), July 1812, as imagined by Carl Röhling (1849–1922), 1887 | next spread : Dr. Struwe’s Drinking Hall in Teplitz-Schönau with Spa Guests in the Promenade Hall. Oil on canvas, 1822, by Karl Gottfried Traugott Faber (1786–1863), known for his works depicting spa towns and landscapes

COMPOSED

1811–April 13, 1812

FIRST PERFORMANCE

December 8, 1813; Vienna, Austria. The composer conducting

INSTRUMENTATION

2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME

41 minutes

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

October 28 and 29, 1892, Auditorium Theatre. Theodore Thomas conducting

July 3, 1936, Ravinia Festival. Ernest Ansermet conducting

MOST RECENT

CSO PERFORMANCES

March 1, and 2, 2024, Orchestra Hall. Petr Popelka conducting

July 20, 2025, Ravinia Festival. Marin Alsop conducting

CSO RECORDINGS

1954. Fritz Reiner conducting. VAI (video)

1955. Fritz Reiner conducting. RCA

1971. Carlo Maria Giulini conducting. Angel

1974. Sir Georg Solti conducting. London

1979. János Ferencsik conducting. CSO (Chicago Symphony Orchestra in the Twentieth Century: Collector’s Choice)

1988. Sir Georg Solti conducting. London

his last years), but also to the uncompromising and disturbing nature of the music itself.

His Seventh Symphony is so well known to us today that we can’t imagine a time that knew Beethoven, but not this glorious work. But that was the case when the poet and the composer walked together in Teplitz in July 1812. Beethoven had finished the A major symphony three months earlier—envisioning a premiere for that spring that did not materialize—but the first performance would not take place for another year and a half, on December 8, 1813.

That night in Vienna gave the rest of the nineteenth century plenty to talk about. No other symphony of Beethoven’s so openly invited interpretation—not even his Sixth, the self-proclaimed Pastoral Symphony, with its bird calls, thunderstorm, and frank evocation of something beyond mere eighth notes and bar lines. To Richard Wagner, Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony was “the apotheosis of the dance.” Berlioz heard a ronde des paysans (peasants’ round) in the first movement. The entire score, in fact, is filled with the rhythms of dance music; sometimes they are surprisingly obsessive and relentless, but they are never truly absent, even on the gentlest of pages.

Beethoven’s magnificent introduction is of unprecedented size and ambition. He begins decisively in A major, but at the first opportunity moves away—not to the dominant (E major) as one would expect, but to the unlikely regions of C major and F major—keys up a third and down a third. Beethoven will not be limited to the seven degrees of the A major scale, which contains neither C- nor F-natural. By the time he’s done, Beethoven will have proven not only that both keys sound comfortably at home in an A major symphony, but that A major can be made to seem like the outsider.

The true significance of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony is to be found in the notes on the page—in his distinctive use of rhythm and pioneering sense of key relationships. By the end of the symphony, it is difficult to hear the ordinary rhythm of a dotted eighth note followed by a sixteenth note in the same way again. And even if we see on the page how Beethoven has turned the conventional rules of harmony upside down, we are still dumbfounded at the ease with which he has done it.

First, we move from the spacious vistas of the introduction, with its plaintive oboe melody, into the joyous, dancing song of the Vivace. Making that transition is a challenge Beethoven relishes—and one that remains a landmark of compositional bravura—as a passage of stagnant, repeated Es (there are sixty-two of them) catch fire suddenly with the dancing dotted rhythm that will carry through the entire movement. The way he manages those repeated notes, halting and faltering and then bursting forth directly in the Vivace, is the mark of a composer who famously sketched, rewrote, and slaved over the precise placement and duration of every note until the rhythm, the pacing, and the long-range effect on the entire passage was just what he wanted. The development section brings new explorations of C and F, and the coda includes a spectacular, long-sustained crescendo, with churning repetitions over a rumbling pedal point E that is said to have convinced the composer Carl Maria von Weber, sixteen years his junior, that Beethoven was “ripe for the madhouse.”

The Allegretto is as famous as any music Beethoven wrote, and it was a success from the first performance, when a repeat was demanded. Like much great art, it is simplicity itself, yet it eludes explanation and has regularly defied other composers’ attempts to duplicate its plain power. It is not a true slow movement, but its marking, allegretto (moderately fast, but not as fast as allegro), assures that it is sufficiently slower than the music that precedes and follows, providing the necessary relief.

By designing the Allegretto in A minor, Beethoven has moved one step closer to F major; he now dares to write the next movement, a raucous scherzo, in that key. A major, when it arrives on the scene, is treated not as the main key of the symphony, but as a foreign visitor. It is a quintessential Beethovenian gambit—the kind of sleight of hand that only the truest of geniuses can pull off.

With nothing more than the two thundering chords that open the finale, we are firmly back in the land of A major. The rhythmic drive of the preceding movements now shifts into high gear, carrying the music to the brink of pandemonium, yet always strictly in control, which is what gives this final sweep of music its hair-raising charge. It is marked Allegro con brio, but the emphasis is on brio. When C and F major return, as they were destined to do, in the development section, they now sound as remote as they did in the symphony’s introduction, and we sense that we have come full circle. The final pages are a brilliant, exhilarating companion to the “madhouse” ending of the first movement.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association is grateful to Bank of America for its generous support as the Maestro Residency Presenter.

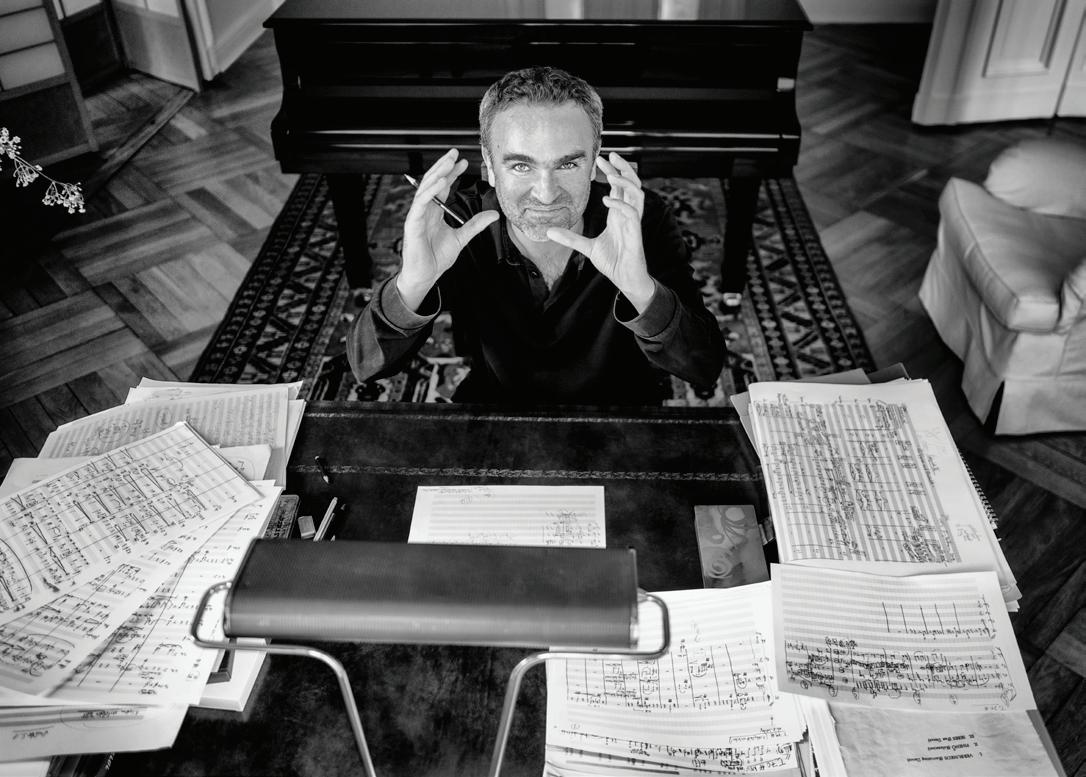

Klaus Mäkelä

Finnish conductor Klaus Mäkelä has been chief conductor of the Oslo Philharmonic since 2020 and music director of the Orchestre de Paris since 2021. He assumes the title of chief conductor of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam in September 2027 and, in the same season, begins his tenure as Zell Music Director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

An exclusive Decca Classics artist, Mäkelä has released three albums with the Orchestre de Paris, including Ballets Russes scores by Stravinsky and Debussy, as well as Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique and Ravel’s La valse. With the Oslo Philharmonic, he has recorded Sibelius’s symphonies, Sibelius’s Violin Concerto and Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto no. 1 with Janine Jansen, and Shostakovich’s symphonies nos. 4, 5, and 6.

With the Oslo Philharmonic, Klaus Mäkelä opened the 2025–26 season with Mahler’s Symphony no. 7 and closes with Magnus Lindberg’s 1985 tour de force, Kraft. Additional highlights include a January tour and residencies in Hamburg, Vienna, Paris, and Essen, with performances of Shostakovich’s Symphony no. 8,

Sibelius’s Lemminkäinen Suite, and the violin concertos by Tchaikovsky and Sibelius with soloist Lisa Batiashvili.

Mäkelä’s fifth season with the Orchestre de Paris features wide-ranging programs, from Beethoven’s Missa solemnis to Pascal Dusapin’s opera oratorio Antigone. With a continued focus on French repertoire and contemporary music, they also perform Bizet’s Symphony in C and Franck’s Symphony in D minor, as well as new works by Guillaume Connesson, Joan Tower, Anders Hillborg, Ellen Reid, and Sauli Zinovjev. His performances at the 2025 BBC Proms and Salzburg Festival with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra were followed by an extensive tour of South Korea and Japan in November. At home they celebrate together the fiftieth anniversary of the traditional Christmas matinee TV broadcasts and begin an annual residency at the 2026 Baden-Baden Easter Festival, taking over from the Berlin Philharmonic.

Klaus Mäkelä conducts the Chicago Symphony in four residencies this season and leads a U.S. tour, making his first appearance with the Orchestra at Carnegie Hall in February, performing Sibelius’s Lemminkäinen Suite and Strauss’s Ein Heldenleben. He returns to the United States in the summer of 2026 for his Ravinia Festival debut, leading the CSO in two programs. In addition, he appears as guest conductor with the Berlin Philharmonic and, as a cellist, partners with members of the Orchestre de Paris and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra.

Given the right pairing of orchestra and conductor, even listeners who know the work well will hear details they had somehow missed before. The CSO and Mäkelä were an ideal match.”

Learn more about Klaus Mäkelä at cso.org/klausmakela

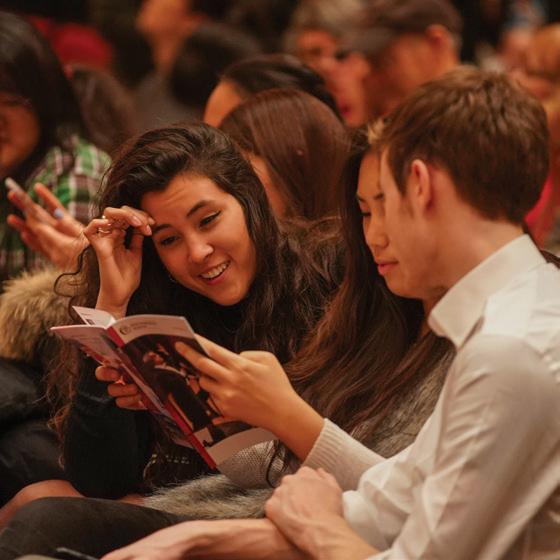

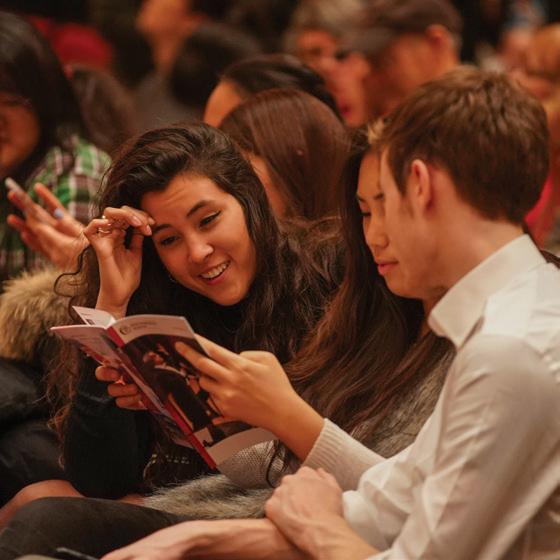

August 5, 2023, Ravinia Festival. Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto no. 3, Marin Alsop conducting These concerts mark Yunchan Lim’s subscription concert debut with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Since Yunchan Lim became the youngest winner of the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition in 2022 at the age of eighteen, his ascent to international stardom has been meteoric.

The video of his performance of Rachmaninov’s Concerto no. 3 trended globally on YouTube in the days after and has now become the mostwatched version of that work on the platform. In the years following his Cliburn win, Lim made debuts with the New York, Los Angeles, Munich, Tokyo, and Seoul philharmonic orchestras; the Chicago, BBC, and Boston symphony orchestras; and the Orchestre de Paris, among others. Recital appearances have included performances at Carnegie Hall in New York, the Verbier Festival, Wigmore Hall in London, the Royal Concertgebouw Amsterdam, and Suntory Hall in Tokyo.

Highlights of the 2025–26 season include debuts with the Philadelphia Orchestra, Staatskapelle Dresden, Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam, and the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, as well as returns to the New York and Los Angeles philharmonics, the Boston and Chicago symphonies, and the Orchestre de Paris. The season also includes recitals in Los Angeles,

Boston, New York (Carnegie Hall), and London (Wigmore Hall), among other major stages.

Yunchan Lim is an exclusive Decca Classics recording artist, and his acclaimed debut studio album, Chopin Études, went triple platinum in South Korea and topped the classical charts around the world. The album won the 2024 Gramophone Award for Piano, and Lim was named Young Artist of the Year, receiving a Diapason d’Or de l’Année and an Opus Klassik Award nomination. His other releases include Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto no. 3 live from the Cliburn Competition final and Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons. His previous releases include the award-winning Cliburn performance of Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes (Steinway and Sons), Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto (Universal Music Group), and his appearance on the Korean Broadcasting System’s 2020 Young Musicians of Korea album. Since 2024, Lim has been an Apple Music Classical Global Ambassador.

Born in Siheung, South Korea, Yunchan Lim began piano lessons at the age of seven. He entered the Seoul Arts Center Music Academy the following year and at thirteen was accepted into the Korea National Institute for the Gifted in Arts, where he met his teacher and mentor, Minsoo Sohn. In 2018, he won second prize and the Chopin Special Award in his first competition, the Cleveland International Piano Competition for Young Artists. That same year, he won the third prize and the audience prize at the Cooper International Competition, which afforded him the opportunity to perform with the Cleveland Orchestra. In 2019, at fifteen, he became the youngest person to win Korea’s IsangYun International Competition.

Lim currently studies at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston with Minsoo Sohn.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra—consistently hailed as one of the world’s best—marks its 135th season in 2025–26. The ensemble’s history began in 1889, when Theodore Thomas, the leading conductor in America and a recognized music pioneer, was invited by Chicago businessman Charles Norman Fay to establish a symphony orchestra. Thomas’s aim to build a permanent orchestra of the highest quality was realized at the first concerts in October 1891 in the Auditorium Theatre. Thomas served as music director until his death in January 1905, just three weeks after the dedication of Orchestra Hall, the Orchestra’s permanent home designed by Daniel Burnham.

Frederick Stock, recruited by Thomas to the viola section in 1895, became assistant conductor in 1899 and succeeded the Orchestra’s founder. His tenure lasted thirty-seven years, from 1905 to 1942—the longest of the Orchestra’s music directors. Stock founded the Civic Orchestra of Chicago— the first training orchestra in the U.S. affiliated with a major orchestra—in 1919, established youth auditions, organized the first subscription concerts especially for children, and began a series of popular concerts.

Three conductors headed the Orchestra during the following decade: Désiré Defauw was music director from 1943 to 1947, Artur Rodzinski in 1947–48, and Rafael Kubelík from 1950 to 1953. The next ten years belonged to Fritz Reiner, whose recordings with the CSO are still considered hallmarks. Reiner invited Margaret Hillis to form the Chicago Symphony Chorus in 1957. For five seasons from 1963 to 1968, Jean Martinon held the position of music director.

Sir Georg Solti, the Orchestra’s eighth music director, served from 1969 until 1991. His arrival launched one of the most successful musical partnerships of our time. The CSO made its first overseas tour to Europe in 1971 under his direction and released numerous award-winning recordings. Beginning in 1991, Solti held the title of music director laureate and returned to conduct the Orchestra each season until his death in September 1997.

Daniel Barenboim became ninth music director in 1991, a position he held until 2006. His tenure was distinguished by the opening of Symphony Center in 1997, appearances with the Orchestra in the dual role of pianist and conductor, and twenty-one international tours. Appointed by Barenboim in 1994 as the Chorus’s second director, Duain Wolfe served until his retirement in 2022.

In 2010, Riccardo Muti became the Orchestra’s tenth music director. During his tenure, the Orchestra deepened its engagement with the Chicago community, nurtured its legacy while supporting a new generation of musicians and composers, and collaborated with visionary artists. In September 2023, Muti became music director emeritus for life.

In April 2024, Finnish conductor Klaus Mäkelä was announced as the Orchestra’s eleventh music director and will begin an initial five-year tenure as Zell Music Director in September 2027. In July 2025, Donald Palumbo became the third director of the Chicago Symphony Chorus.

Carlo Maria Giulini was named the Orchestra’s first principal guest conductor in 1969, serving until 1972; Claudio Abbado held the position from 1982 to 1985. Pierre Boulez was appointed as principal guest conductor in 1995 and was named Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus in 2006, a position he held until his death in January 2016. From 2006 to 2010, Bernard Haitink was the Orchestra’s first principal conductor.

Mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato is the CSO’s Artist-in-Residence for the 2025–26 season.

The Orchestra first performed at Ravinia Park in 1905 and appeared frequently through August 1931, after which the park was closed for most of the Great Depression. In August 1936, the Orchestra helped to inaugurate the first season of the Ravinia Festival, and it has been in residence nearly every summer since.

Since 1916, recording has been a significant part of the Orchestra’s activities. Recordings by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus— including recent releases on CSO Resound, the Orchestra’s recording label launched in 2007— have earned sixty-five Grammy awards from the Recording Academy.

Klaus Mäkelä Zell Music Director Designate

Joyce DiDonato Artist-in-Residence

VIOLINS

Robert Chen Concertmaster

The Louis C. Sudler

Chair, endowed by an

anonymous benefactor

Stephanie Jeong

Associate Concertmaster

The Cathy and Bill Osborn Chair

David Taylor*

Assistant Concertmaster

The Ling Z. and Michael C.

Markovitz Chair

Yuan-Qing Yu*

Assistant Concertmaster

So Young Bae

Cornelius Chiu

Gina DiBello

Kozue Funakoshi

Russell Hershow

Qing Hou

Gabriela Lara

Matous Michal

Simon Michal

Sando Shia

Susan Synnestvedt

Rong-Yan Tang

Baird Dodge Principal

Danny Yehun Jin

Assistant Principal

Lei Hou

Ni Mei

Hermine Gagné

Rachel Goldstein

Mihaela Ionescu

Melanie Kupchynsky §

Wendy Koons Meir

Ronald Satkiewicz ‡

Florence Schwartz

VIOLAS

Teng Li Principal

The Paul Hindemith Principal Viola Chair

Catherine Brubaker

Youming Chen

Sunghee Choi

Wei-Ting Kuo

Danny Lai

Weijing Michal

Diane Mues

Lawrence Neuman

Max Raimi

John Sharp Principal

The Eloise W. Martin Chair

Kenneth Olsen

Assistant Principal

The Adele Gidwitz Chair

Karen Basrak §

The Joseph A. and Cecile Renaud Gorno Chair

Richard Hirschl

Olivia Jakyoung Huh

Daniel Katz

Katinka Kleijn

Brant Taylor

The Ann Blickensderfer and Roger Blickensderfer Chair

BASSES

Alexander Hanna Principal

The David and Mary Winton

Green Principal Bass Chair

Alexander Horton

Assistant Principal

Daniel Carson

Ian Hallas

Robert Kassinger

Mark Kraemer

Stephen Lester

Bradley Opland

Andrew Sommer

FLUTES

Stefán Ragnar Höskuldsson § Principal

The Erika and Dietrich M.

Gross Principal Flute Chair

Emma Gerstein

Jennifer Gunn

PICCOLO

Jennifer Gunn

The Dora and John Aalbregtse Piccolo Chair

OBOES

William Welter Principal

Lora Schaefer

Assistant Principal

The Gilchrist Foundation,

Jocelyn Gilchrist Chair

Scott Hostetler

ENGLISH HORN

Scott Hostetler

Riccardo Muti Music Director Emeritus for Life

CLARINETS

Stephen Williamson Principal

John Bruce Yeh

Assistant Principal

The Governing

Members Chair

Gregory Smith

E-FLAT CLARINET

John Bruce Yeh

BASSOONS

Keith Buncke Principal

William Buchman

Assistant Principal

Miles Maner

HORNS

Mark Almond Principal

James Smelser

David Griffin

Oto Carrillo

Susanna Gaunt

Daniel Gingrich ‡

TRUMPETS

Esteban Batallán Principal

The Adolph Herseth Principal Trumpet Chair, endowed by an anonymous benefactor

John Hagstrom

The Bleck Family Chair

Tage Larsen

TROMBONES

Timothy Higgins Principal

The Lisa and Paul Wiggin

Principal Trombone Chair

Michael Mulcahy

Charles Vernon

BASS TROMBONE

Charles Vernon

TUBA

Gene Pokorny Principal

The Arnold Jacobs Principal Tuba Chair, endowed by Christine Querfeld

* Assistant concertmasters are listed by seniority. ‡ On sabbatical § On leave

The CSO’s music director position is endowed in perpetuity by a generous gift from the Zell Family Foundation. The Louise H. Benton Wagner chair is currently unoccupied.

TIMPANI

David Herbert Principal

The Clinton Family Fund Chair

Vadim Karpinos

Assistant Principal

PERCUSSION

Cynthia Yeh Principal

Patricia Dash

Vadim Karpinos

LIBRARIANS

Justin Vibbard Principal

Carole Keller

Mark Swanson

CSO FELLOWS

Ariel Seunghyun Lee Violin

Jesús Linárez Violin

The Michael and Kathleen Elliott Fellow

ORCHESTRA PERSONNEL

John Deverman Director

Anne MacQuarrie Manager, CSO Auditions and Orchestra Personnel

STAGE TECHNICIANS

Christopher Lewis

Stage Manager

Blair Carlson

Paul Christopher

Chris Grannen

Ryan Hartge

Peter Landry

Joshua Mondie

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra string sections utilize revolving seating. Players behind the first desk (first two desks in the violins) change seats systematically every two weeks and are listed alphabetically. Section percussionists also are listed alphabetically.

Discover more about the musicians, concerts, and generous supporters of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association online, at cso.org.

Find articles and program notes, listen to CSOradio, and watch CSOtv at Experience CSO.

cso.org/experience

Get involved with our many volunteer and affiliate groups.

cso.org/getinvolved

Connect with us on social @chicagosymphony

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Board of Trustees

OFFICERS

Mary Louise Gorno Chair

Chester A. Gougis Vice Chair

Steven Shebik Vice Chair

Helen Zell Vice Chair

Renée Metcalf Treasurer

Jeff Alexander President

Kristine Stassen Secretary of the Board

Stacie M. Frank Assistant Treasurer

Dale Hedding Vice President for Development

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Administration

SENIOR LEADERSHIP

Jeff Alexander President

Stacie M. Frank Vice President & Chief Financial Officer, Finance and Administration

Dale Hedding Vice President, Development

Ryan Lewis Vice President, Sales and Marketing

Vanessa Moss Vice President, Orchestra and Building Operations

Cristina Rocca Vice President, Artistic Administration

The Richard and Mary L. Gray Chair

Eileen Chambers Director, Institutional Communications

Jonathan McCormick Managing Director, Negaunee Music Institute at the CSO

Visit cso.org/csoa to view a complete listing of the CSOA Board of Trustees and Administration.

For complete listings of our generous supporters, please visit the Richard and Helen Thomas Donor Gallery.

cso.org/donorgallery

MAR 5-6

Mäkelä Conducts The Rite of Spring

APR 16-18

Evgeny Kissin with the CSO

APR 23-26

Hisaishi Conducts Hisaishi

MAY 12

Samara Joy & the CSO

JUNE 23