GREY CITY: From the Life of the Mind to Life on Wall Street

JANUARY 28, 2026 FOURTH WEEK VOL. 138, ISSUE 7 PAGE 8

GREY CITY: From the Life of the Mind to Life on Wall Street

JANUARY 28, 2026 FOURTH WEEK VOL. 138, ISSUE 7 PAGE 8

NEWS: Officers Detain Man in Hyde Park, Tasing Him and Pointing a Gun at His Head PAGE 3

VIEWPOINTS: Phones Are Incompatible with Art

ARTS AND CULTURE: AxLab Blends Art and Technology

SPORTS: UChicago Has a Rugby Team, and They’re Really, Really Good

By JINNY KIM | Data Editor

A student discovered a major vulnerability in the my.UChicago portal that may have exposed personal information of current and former students, faculty, and staff. The vulnerability allowed users unauthorized access to multiple databases, one of which included dates of birth, course grades, and possibly Social Security numbers.

Alan Zhu, the first-year student who found the vulnerability, reached out to the University’s Information Security Office on December 30. Zhu was notified on January 13 that the issue was resolved.

The discovery follows another vulnerability Zhu reported to IT last September, which also allowed my.UChicago users

access to others’ personal information, including dates of birth, campus IDs, and gender.

Matt Morton, UChicago’s chief information security officer, said in a statement to the Maroon that “the student accessed the page by following a link that pointed to an administrative area rather than the standard student interface. From there, they were able to reach a page that contained some personal data, like first and last name, that was not intended for student use.”

While Morton said that the University “initiated a broader review of this system to identify and address any comparable issues” after Zhu reported the initial vul-

“It’s Taking a Village”:

nerability in September, the second, more extensive data breach could be accessed through the same page on my.UChicago.

“It wasn’t like I was looking around to see, ‘Can I figure out everyone’s Social Security numbers?’” Zhu said. “I was just poking around, and I found it. Imagine [if] someone actually wanted to do this. Then they’d be able to find it really quickly, right?”

In response to a question about whether any my.UChicago users could have accessed the page, Morton said that “the configuration issue could have allowed other authenticated users to reach the same page.” The University did not respond to a follow-up question from the Maroon about who qualifies as an authenticated user.

The Maroon verified that multiple us-

ers were able to access the administrative page with others’ personal information before the vulnerability was fixed but was not able to verify that accounts other than Zhu’s allowed access to Social Security numbers.

“If it were that this entire website [was] open to anyone who clicked on that region of the web page, then clearly the potential risk will be much higher,” Ben Zhao, the Neubauer Professor of Computer Science, told the Maroon.

The University did not issue a public statement to alert the University community about the data breach incidents.

To report a possible compromise or other data security incident, contact the University IT Services Security team at security@uchicago.edu or (773) 702–2378.

By CELESTE ALCALAY | Senior News Reporter

On the South Side, in a room lined with racks of canned food and hygiene supplies stacked nearly to the ceiling, attorney Maureen Graves works at her desk while volunteers comb through file cabinets and families trickle in.

A year and a half ago, Graves began a volunteer-run legal aid clinic for recent migrants, many from Venezuela and Colombia, fleeing violent political persecution and economic crises in their home countries. Now, around 50,000 Venezuelans in Chicago are in limbo after the Trump administration rescinded their protected status, and some are still looking for legal assistance to complete asylum applications and obtain work permits.

“People are very scared,” Graves said. “A lot of them are barely going outside their houses.”

Work at the clinic has looked different since the deployment of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents to Chicago in September, sparking heightened anxiety among newly undocument-

ed immigrants. The clinic has tightened its security protocol out of concerns that clients could be arrested on site. For a while, volunteers patrolled the entrance. And Graves has seen “a lot more” people miss court dates out of fear after a summer surge in ICE arrests outside courtrooms after asylum hearings.

The Maroon has documented at least eight detainments in Hyde Park, and ICE has made over a thousand arrests in Illinois since October.

“So many of our clients are unable to work because they’re afraid of getting detained,” Bess Cohen, one of the clinic’s main organizers, said. “Not being able to go outside means you can’t pay your rent, you can’t get health care services, you can’t take your kids to school.”

The clinic is part of a larger aid effort and a 300-person organization, Neighbors United for Mutual Support. Volunteers have stepped up to fill different needs, delivering groceries and accompanying kids to school, Cohen said. Similar

Volunteers at the legal aid clinic work beneath a bulletin board displaying a pennant that reads, “We can do hard things.” Graves asked that the South Side religious institution where the clinic operates remain unnamed because of the vulnerable legal status of her clients. celeste alcalay

efforts across Chicago communities, like “magic school buses,” have tried to help undocumented immigrant families feel

safer in public places or avoid them altogether.

By ISAIAH GLICK | Deputy News Editor

Joyce Qi, a fourth-year in the College, passed away on Sunday due to injuries sustained in a car accident. She was 21 years old.

Dean of the College Melina Hale and Dean of Students in the College Philip Venticinque shared the news of Qi’s passing in an email later that day.

Qi was in a car that crashed on the 2500 block of South DuSable Lake Shore Drive early Sunday morning, the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office con-

firmed to the Maroon. ABC7 reported Sunday that the four other people in the car at the time were expected to recover.

Qi was born on March 25, 2004, and grew up in Northern Virginia, graduating from McLean High School in 2022 before attending the University of Chicago.

According to Hale and Venticinque, Qi was studying economics and data science. She was admitted to the University of California, Los Angeles School of Law last month.

Her friends said she was among the top-ranked students on Beli, a food ranking app, and enjoyed blue panda ice cream from Cathey Dining Commons.

A memorial was held on Qi’s behalf at 1:30 p.m. on January 19 in Bond Chapel.

The email from Hale and Venticinque referred students to resources on campus, including UChicago Student Wellness, the College Student Care and Support Team, and religious advisers. Students can also text the dean-on-call through the UChicago Safe app or call them through the University of Chicago Police Department

at (773) 702–8181.

Counselors at UChicago Student Wellness are available by phone at (773) 834–9355, and the therapist-on-call can be reached for immediate support at (773) 702–3625.

Editor’s note: We hope to follow up on this article with an obituary memorializing Joyce’s life and her time as a member of the University community. We ask anyone who has memories they want to share about Joyce to please contact us at editor@ chicagomaroon.com.

By ELENA EISENSTADT | Deputy Editor-in-Chief and NATHANIEL RODWELL-SIMON | News Editor

Law enforcement officers detained a man around 7 a.m. on January 14 in an alley between UChicago’s Community Programs Accelerator building and an apartment complex near East 53rd Street and South Maryland Avenue, according to two videos of the incident obtained by the Maroon

The alley between UChicago’s Community Programs Accelerator and an apartment complex near East 53rd Street and South Maryland Avenue. nathaniel rodwell-simon

In a post on Instagram, Hyde Park’s Rapid Response network called the detention “federal immigration activity” and said that officers “attempted to detain multiple people outside their homes” at the same location.

The incident marks the eighth im-

migration detainment near UChicago’s campus since October and the first of 2026.

When asked to confirm details about the detention, an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) public affairs officer asked the Maroon to provide footage of the incident and details about the detained individual. The Maroon declined to do so. ICE did not confirm to the Maroon whether it was responsible for the detention, nor did it provide details on what grounds the person was detained, but said it was looking into the request.

In a statement on January 14, Hyde Park Rapid Response told the Maroon that “one person was abducted in Hyde Park this morning, and his family has been contacted about his detention. We have not received reports of any other detentions or federal immigration enforcement activity in Hyde Park or surrounding neighbors today.”

“We encourage anyone who believes they are witnessing ICE or other federal immigration enforcement activity to contact ICIRR’s Family Support Network at (855)-435-7693,” the statement concluded.

The Maroon was not able to independently verify whether the detention was conducted by immigration officers,

nor was the Maroon able to verify where the person detained is currently being held in custody.

A UChicago student who witnessed the arrest from their apartment window

Tiffany Li, editor-in-chief

Elena Eisenstadt, deputy editor-in-chief

Evgenia Anastasakos, managing editor

Haebin Jung, chief production officer

Adam Zaidi and Arav Saksena, chief financial officers

The Maroon Editorial Board consists of the editors-in-chief and select staff of the Maroon

NEWS

Gabriel Kraemer, co-head editor

Anika Krishnaswamy, co-head editor

Nathaniel Rodwell-Simon, editor

GREY CITY

Celeste Alcalay, editor

Anika Krishnaswamy, editor

Vedika Baradwaj, editor

VIEWPOINTS

Sofia Cavallone, co-head editor

Camille Cypher, co-head editor

ARTS AND CULTURE

Nolan Shaffer, co-head editor

Shawn Quek, co-head editor

Emily Sun, co-head editor

SPORTS Shrivas Raghavan, editor

Josh Grossman, editor

DATA AND TECHNOLOGY

Nikhil Patel, editor

Jinny Kim, editor Emily Sun, editor

CROSSWORD

Eli Lowe, head editor

PHOTO AND VIDEO

Nathaniel Rodwell-Simon, head editor

DESIGN

Eliot Aguera y Arcas, editor

COPY

Mazie Witter, chief

NEWSLETTER Evgenia Anastasakos, editor

“... [W]e need a lot more people making sure that there are safe places for people to find support.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 2

The need for legal aid, too, is growing, as the Trump administration makes it increasingly difficult for asylum seekers to pursue legal status in the U.S. The government last year ended Temporary Protected Status for over 600,000 Venezuelans nationwide. A court challenge is pending, but protections have lapsed.

“It was this huge ‘de-documenting’ event where people who had protection suddenly didn’t have protection,” Graves said.

Ultimately, Graves said the goal of the grassroots effort has always been to “flatten the curve” by helping temporarily until immigrants can find immigration attorneys.

“We’ve gotten hundreds of people work permits,” Graves said. “We’ve averted lots of evictions, helped with sicknesses.” The clinic has had an 80 percent success rate of reopening deportation cases, she said.

Recently, the federal government has

employed a slew of different tactics in its immigration crackdown, which has added obstacles to legal processes.

The clinic helps clients respond to “third country” deportation orders, which attempt to deport people to countries where they have no connections. More asylum cases have been disrupted and sometimes dismissed because of the firing of judges, according to Bruce Tyler, the clinic’s paralegal, who began his current role in December.

“Trump did effectively close the border,” he said. Tighter border security has led him to see fewer new asylum applications.

Also, many asylum seekers were unable to work in the U.S. legally after the federal government revoked work permits granted through the Biden-era CBP One app, designed to streamline the entry process at the border. People who had paid over $400 for a work permit found that it was no longer valid, Graves said.

In response, Cohen has directed more

attention toward fundraising, chasing after philanthropic dollars to supplement the clinic’s existing donation program.

To raise money, volunteers have gone Christmas caroling and held square dancing functions. A detective fiction author held a talk at a local bookstore, which raised roughly $2,000 for the clinic, Graves said. The money can go toward loans for work permits and helping detainees contact their lawyers and families to file bond motions, she explained.

Cohen said now is “a big moment for people wanting to support immigration work.”

The clinic has raised enough money to pay for added help from a few people with experience, like Tyler, and roughly 275 people signed up to volunteer in the last year, according to Cohen.

About 50 volunteers are regularly active, and the leadership team consists of eight people, a more robust core than last year.

Still, Cohen wants to ensure that the

outpouring of support doesn’t disappear “if and when the public attention on immigration shifts away from immigration in Chicago.”

The clinic is looking for volunteers, organizers say. “Even coming in and filing for a few hours is very helpful,” Graves said. “Coming in and doing an interview in Spanish is even more helpful.”

Volunteer Ava Zhang discovered the clinic through Seeds of Justice, a University of Chicago community service program for first-year students. A Spanish speaker, she has helped clients fill out their housing histories for asylum applications.

Zhang said the heightened ICE presence in Chicago “is scary, and that’s why I feel like we need a lot more people making sure that there are safe places for people to find support.”

“It’s taking a village, and we have hundreds of people who are stepping up,” Cohen said. “But unfortunately, there are thousands of people who need help.”

“Good Old-Fashioned Imperialism”: Mearsheimer Talks Venezuela and Iran

By CLARA TRIPP | Senior News Reporter

The Chicago Center for Contemporary Theory (3CT) hosted a talk by John Mearsheimer, the R. Wendell Harrison Distinguished Service Professor of Political Science, on Thursday about the U.S. government’s January 3 capture of President of Venezuela Nicolás Maduro and his wife First Lady Cilia Flores.

His lecture, followed by 45 minutes of Q&A, covered three overarching topics: President Donald Trump’s overall approach to using military force, the invasion of Venezuela, and the recent protests in Iran.

Mearsheimer, who has taught at the University since 1982 and is known for his theory of offensive realism in international relations, focused on Trump’s selective willingness to use military force

to achieve foreign policy objectives. While Trump shies away from conflict with “great powers” like China and Russia, according to Mearsheimer, he threatens “middle and lower powers” and has attacked seven nations in his second term.

“He’s using military force liberally, with a light touch, and that allows him to use it often,” Mearsheimer said.

Trump justified the special forces operation in Venezuela with the Monroe Doctrine—an 1823 warning against European interference in the Western Hemisphere—which Mearsheimer believes is inapplicable.

Trump initially alleged that the invasion was a response to narcoterrorism, also claiming that “hostile regimes” were

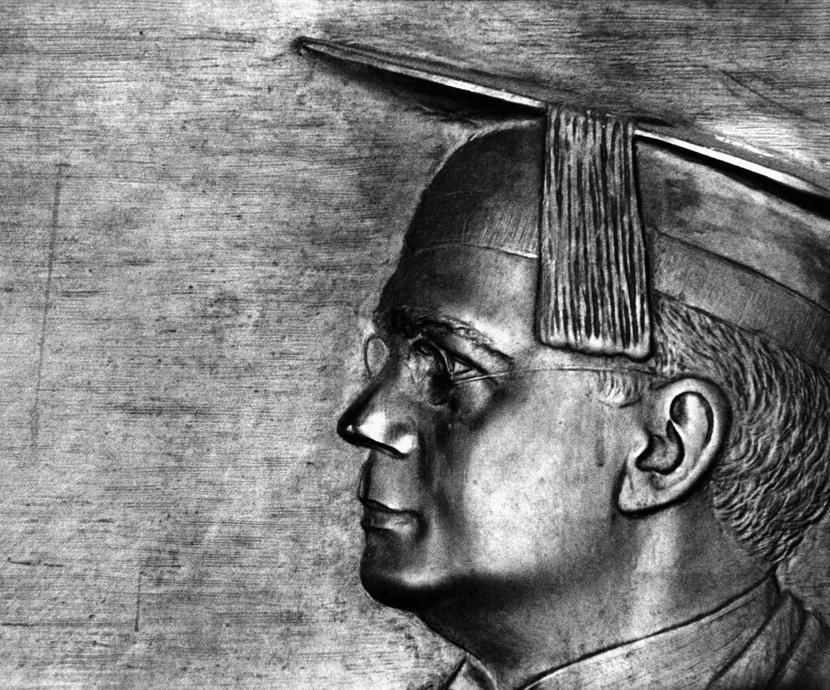

John Mearsheimer, the R. Wendell Harrison Distinguished Service Professor of Political Science, speaks during the 3CT event on January 22. olin nafziger .

CONTINUED FROM PG. 3

told the Maroon there were three officers and three different cars in the alley during the event. Only two officers and one vehicle are visible in the footage obtained by the Maroon

In the first video, an officer can be seen pushing the detained man up against the side of an unmarked, dark SUV with emergency vehicle lights. Another officer pulls out what appears to be a handgun from his holster and points it at the man’s head for several seconds before returning it to his side. The man then calls for help in Spanish.

In the second video from the same vantage point, one of the officers fires at the man with a taser. At the time, the man was being held against the side of the vehicle and did not appear to be resisting or attempting to flee.

Both videos can be viewed in the online version of this article.

After the man screamed and collapsed to the ground, the officers held him down, continuing to point the taser at his back.

One officer appears to use his foot on the man’s back to keep the man on the ground. The man again calls for help in Spanish.

Per Department of Homeland Security guidelines, “Use of force is necessary when it is reasonably required to carry out the Authorized Officer’s law enforcement duties in a given situation, considering the totality of facts and circumstances of a particular situation,” for example, when “the subject poses an imminent threat to the safety of the Authorized Officer or others” or “is actively resisting or attempting to evade arrest by flight.”

A document titled “Interim ICE Use of Force Policy” governing ICE’s use of tasers has recently been redacted from government websites. ICE’s current policy around use of force states that it must be done “in accordance with agency policy, procedure, and guidelines.”

The two officers in the video wore plainclothes and body armor. One was labeled “Police,” while the other was unmarked. The unmarked officer wore a

face mask. After putting the man in one of the cars, the officers fist-bumped each other, according to the student who witnessed the arrest.

“We’re in the alley, Maryland and 53rd, Maryland and 53rd. Hurry up,” one of the officers said, stepping out of frame before the video cuts off.

The detainment occurred one week after an ICE agent fatally shot Renee Good in Minneapolis. Amid heightened ICE activity in Chicago this fall, ICE agents also shot two people, Silverio Villegas-Gonzalez and Marimar Martinez, in individual, high profile cases.

Illinois and Chicago sued the Trump administration on Monday, alleging “unlawful and violent tactics” by federal agents during “Operation Midway Blitz”— the Department of Homeland Security’s name for immigration enforcement activities in Chicagoland since September. Last week, a federal judge cited the fatal shooting in Minneapolis in her decision to maintain limits on use of force during immigration enforcement activities.

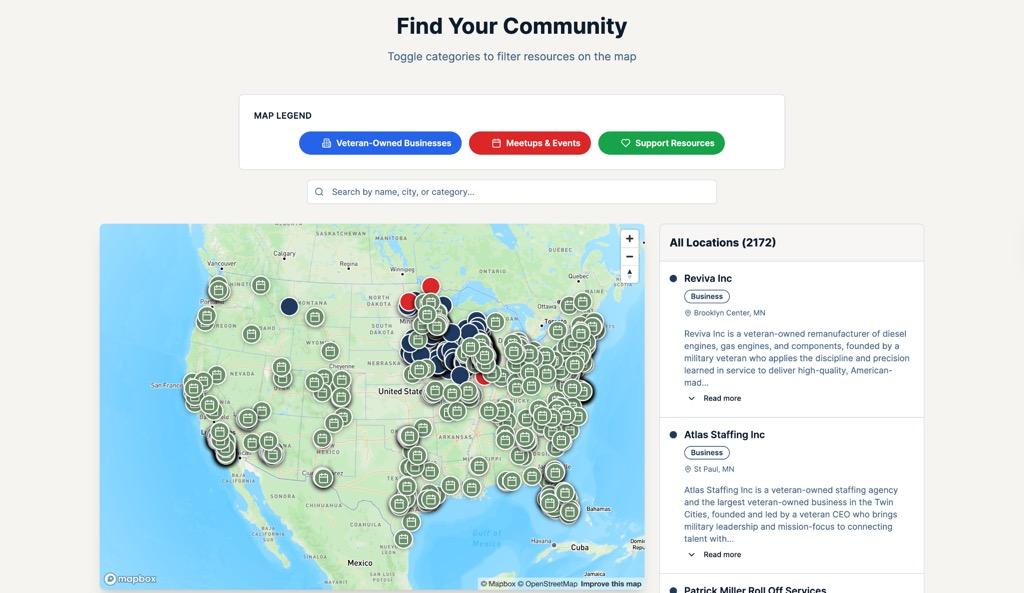

Editor’s note: The M aroon is documenting Federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) sightings in the Hyde Park, Kenwood, and Woodlawn neighborhoods on an interactive map following the launch of ICE’s Operation Midway Blitz in fall. This incident has been added to the map, which can be viewed online at chicagomaroon.com. This article was translated into Spanish by Elena Eisenstadt. Escanee el código QR para ver la noticia en español.

By SONIA BRADLEY | News Reporter

When his father returned from his tour of duty as a U.S. Navy commander in Jordan, first-year Henry Sabo noticed that he experienced difficulty reintegrating into his community. Sabo, who grew up in Minneapolis, Minnesota, felt that part of his father’s struggle was caused by the low number of veterans in the state.

“He didn’t really know where to look for things. Even the [Department of Veterans Affairs] was kind of chaotic and all over the place and was definitely not a resource,” Sabo told the Maroon

Inspired by his father’s experience, Sabo launched Veteran Atlas, a website that compiles resources and “helps veterans find community,” last October. The

website features an interactive map that allows visitors to find veteran-owned businesses, veteran-specific meetups and events, and counseling and mental health services in their area.

When he began researching resources for the map, Sabo said he “was surprised by the sheer number of resources there are and how scattered they are.”

“They’re all over, and if we’re being honest, I don’t know the capacity of veterans to go out and find those things on their own, especially because [the resources] aren’t advertised very well,” he said.

Sabo hopes Veteran Atlas can act as a “one-stop shop” for veteran-related community resources. While the site is

currently focused on resources in the Midwest, he hopes to eventually include the rest of the United States.

The website also allows visitors to submit information about their own veteran-owned businesses to be added to the map and contribute to the network of support.

“I’d like to set up a way for them to communicate, to have it be some kind of network,” Sabo said.

Sabo had no past experience coding but decided to teach himself the skills he needed to make the site. “I am trying to learn data scraping on my own,” he said.

Since its launch, the site has had 2,300 visitors according to Sabo, and he hopes to expand its reach as he continues developing it.

“At a very basic level, [I hope to have]

The interactive map on the Veteran Atlas homepage, which allows visitors to locate veteran-owned businesses, community events, and mental health support resources. courtesy of henry sabo.

“...

gaining influence in Latin America, notionally violating the Monroe Doctrine. Mearsheimer rejected this claim, noting that, while Russia and China have formed economic ties in the region, including in Venezuela, there is no evidence of military alliances. “The Monroe Doctrine is all about keeping military forces out of our backyard, not preventing economic intercourse,” Mearsheimer said.

While Mearsheimer initially assumed the invasion aimed to overthrow Maduro’s socialist regime, he now views it as “good old-fashioned imperialism.” But imperialism, Mearsheimer said, is “a losing enterprise,” in which the expense of resurrecting the Venezuelan oil industry will far outstrip the benefits.

Mearsheimer argued that, unlike presidents who pursued regime change to establish democratic governments, Trump has not made moves to depose Venezuela’s authoritarian government, due to what Mearsheimer views as his reluctance to put “boots on the ground.” Trump has not strongly pushed for opposition leader María Corina Machado to become acting

president and has said he will ensure cooperation using economic leverage, not military force, in the future.

“When things eventually settle in Venezuela, what’s he going to do?” Mearsheimer said. “There’s going to be a very powerful temptation to put boots on the ground to fix the problem—I think this is going to end up as a huge black mark on the United States and on the Trump administration.”

Mearsheimer ended his lecture with a discussion of recent protests in Iran, which were initially sparked by economic discontent and Iran’s 12-Day War with Israel in June but later expanded into wider criticism of Iran’s theocratic government. The government shut down all internet services on January 8 and declared that the protests had ended on January 21. Several thousand protesters were killed during the events.

Mearsheimer posited that U.S. strategy in Iran is a “tag team” operation largely driven by Israel’s desires. “What the United States and Israel want to do in Iran is get rid of the regime and then break the country apart—no democratization—because then it’s not a threat to Israel,” he said.

He made repeated comparisons to the

nearly 14-year Syrian Civil War, arguing that the U.S. typically destabilizes regimes through a four-step process.

First, Mearsheimer said, Trump applied a strategy of “maximum pressure” to cripple the economy and generate protests; second, CIA, Mossad, and Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) agents were inserted to fuel violence among demonstrators; third, the American mainstream media began to propagate a story about one-sided violence perpetrated by an evil regime; finally, when protests reached a tipping point, the U.S. planned to intervene as a savior.

“I don’t want to deny that there are some legitimate reasons for protests [in Iran],” Mearsheimer said. “But you have to understand that the U.S. has wrecked their economy for the purpose of creating [protests].”

Though Trump has repeatedly threatened to use military force in Iran, Mearsheimer believes he has been restrained by his advisors’ inability to guarantee a decisive victory.

Without protests, U.S. military intervention would only feed nationalism

in Iran, according to Mearsheimer. “The historical record is very clear on this: when you bomb a country, you bring the population together.”

Moreover, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu personally requested that Trump refrain from attacks. “Netanyahu understands well that very little has changed since June 2025, and Israel is no better able to defend itself [from Iran],” Mearsheimer said.

Trump has largely toned down his threats, though he announced on January 23 that “an armada” is headed to monitor Iran.

Mearsheimer predicted that U.S. policy toward Iran will remain an unresolved challenge, since sustained pressure risks pushing Iran further toward nuclear development. Venezuela, on the other hand, will worsen under continued U.S. involvement. He emphasized that, alongside a desire for swift, conclusive military victories, the president’s foreign policy approach is underpinned by a contempt for international law and multilateral institutions.

“He’s a unilateralist: he dislikes allies almost as much as he dislikes adversaries.”

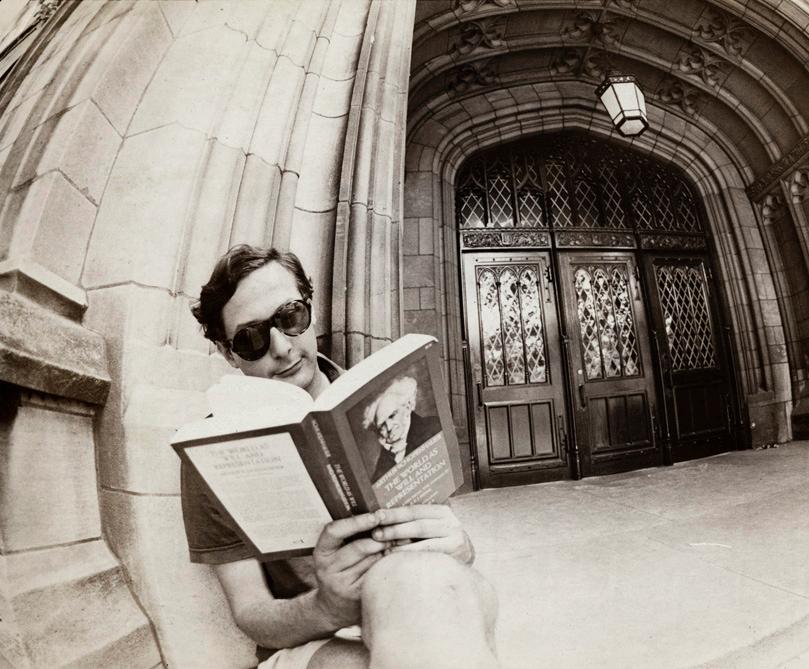

To celebrate 100 years of Swift Hall, Maroon photographers recreated archival photos of the building.

By DAMIAN ALMEIDA BARAY | Deputy Photo Editor and EMILY KIM | Staff Photographer

During a ceremony in early November 1924, University President Ernest DeWitt Burton remarked that “society still needs the spiritual and social leader, the man who not only has a message to utter from the pulpit, but is able every day in the week to take a leading part

with his fellows in the endeavor to make this a better world for children to be born into and to live in, a better world for all of us to spend our days in.”

Moments later, Dean of the Divinity School Shailer Mathews laid the cornerstone of the Theology Building, now

known as Swift Hall. Plans for a home for the Divinity School, UChicago’s oldest professional school and a reconfiguration of the Baptist Theological Union’s Morgan Park Seminary, were adopted as early as 1922. Construction was completed in 1926, with Bond Chapel and the cloister connecting the two buildings soon to follow.

Maroon photographers marked

the occasion of Swift Hall’s 100-year anniversary by recreating old sights and scenes from inside and around the building.

The full version of this photo essay can be found online at chicagomaroon.com.

Nathaniel Rodwell-Simon contributed reporting.

UChicago alumni and students discuss finance recruiting at the College.

By VEDIKA BARADWAJ | Grey City Editor

It’s 8 p.m. on a Wednesday evening, and suited silhouettes scurry out of Ida Noyes Hall after a seemingly long “Night on Wall Street.” The annual event, hosted by Career Advancement, allows select students the chance to exchange conversation and résumés with recruiters, giving them a glimpse into a career that looms large in UChicago’s professional imagination.

Recruiting—the months-long ritual of networking, interviewing, and studying for technical assessments to secure a coveted third-year internship—is a rite of passage for finance prospectives. It’s framed less as a process imposed on students and more as one they actively undertake. Suit jackets hang from the backs of lecture hall seats. Seated in the corner of Bartlett Dining Commons, a student, in hushed whispers, walks me through a discounted cash-flow model like it is a secret passageway. Another student rushes out of Saieh Hall with wired earphones in, not listening to music but taking a networking call as he crosses the quad.

It is not the firms who recruit students so much as the students who recruit for firms. The inverted subject-object usage of the verb is particularly revealing; according to Extern, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and J. P. Morgan had acceptance rates below 1 percent in the 2026 application cycle.

35 percent of the UChicago Class of 2025 entering the workforce chose the financial services industry, making it the most popular post-graduation industry, according to data from Career Advancement. This is an increase from the Class of 2024, of which 32 percent entered finance. It is also comparable to peer institutions considered more “preprofessional,” like the University of Pennsylvania, where 34 percent of graduating fourth-years in 2024 began work in financial services.

So what’s the appeal to finance that makes UChicago students willing to endure such a competitive process?

The Allure of Finance

For Hetav Mehta, a second-year cur-

rently going through recruitment for investment banking, the appeal of the field is its fast-paced environment and real-world relevance: “I came to UChicago because I wanted to do econ[omics] and math academia or something, especially when I applied. But when I looked into math academia, I realized that I couldn’t make a tangible impact with my research—it would take too much time. With investment banking, you get that outcome outright, and you get promoted for it.” As an investment banking analyst, Mehta could be staffed on projects or “deals,” which can materialize into real-life company mergers or public offerings in as little as three months.

Second-year Zander Lee took a liking to “quant” finance—a specialized branch that applies sophisticated mathematical models to the field of finance. “I thought I was pretty good at math. So, I came here assuming that I was a math major,” he said. “And a lot of my friends that I made early on were also math majors, and they were all interested in quant finance.”

S. (A.B. ’24)—who requested anonymity, citing a strict workplace policy—works as an investment banking analyst at a bulge bracket bank. She remembers the recruiting process very well. S. knew she was leaning toward business starting in her first year, so she followed the advice of her seniors in finance clubs and set out on a path that led her to investment banking. In her circles, it was considered a prestigious entry-level job that could advance her career trajectory.

S. specified how the rigorous and technical nature of the training shapes its prestige, “so whatever career you choose after, it opens up a lot of different paths.” Many choose to remain in the financial services industry in higher paying roles (private equity and asset management are considered common “exit paths”) or choose to pivot into entirely new fields such as product management or entrepreneurship.

But she points to another important ingredient in its prestige: exclusivity. “Just because of the sheer number of people that

are interested in investment banking versus how many slots there are, I feel like that is probably a reason why people think it is prestigious.”

Compensation, unsurprisingly, plays a central role in finance’s allure. New graduates in entry-level positions can earn six-figure incomes, typically ranging from $100,000 to $200,000. “Of course [pay] was a factor,” Lee said when asked about his interest in finance as a post-graduation career. “Anybody who says it’s not a factor at all is lying to you.”

“I’m at UChicago. Clearly, I Have Some Grind Tolerance.”

The high pay, however, comes at a cost. Investment banking is notorious for its demanding hours, with estimates ranging from 60–80 hours per week, even climbing to 100 during busy deal cycles. While the reality is hardly unknown to UChicago students, S. highlighted that the strain is not merely the length of the workday but its unpredictability. On some days, she is done with work at 4:30 p.m., “and then I don’t get my next round of work until 8 p.m. or 9 p.m. and I don’t necessarily expect when I’m going to get work, so that can be pretty challenging,” she said. “Clients can ask for things with a one-day turnaround.” This time pressure creates stress throughout the chain of command. “If your client has a crazy deadline, it puts a bunch of crazy deadlines internally as well.”

Still, for many students, the tradeoff seems fair. “I never really considered it to be a major, major issue. The work-life balance [in quantitative finance] isn’t as bad as working in other areas of finance. The work seems pretty interesting,” Lee said. “I’m at UChicago. Clearly, I have some grind tolerance.”

The nexus between the rise in preprofessional culture at the University, the creation of the business economics track of the economics major, and the track’s increasing popularity among undergraduates is not new campus discourse. Career preparation is a central part of the under-

lying philosophy of the business economics track; the Department of Economics website highlights how the curriculum is something students “will find useful in carrying out their day-to-day tasks.”

However, for S., the purported credential signaling of the business economics track does not translate into preparedness for work. “It’s good to take classes like accounting and corporate finance. It gives you a glimpse into some of the things you might do, but I don’t think any class really has translated to what I do day to day. Everything I’ve learned is on the job,” she said.

As an analyst, some of the tasks S. must perform include reading through hundreds of pages of filings or equity research reports to find specific estimate numbers; making presentations, reports, or “pitch books” summarizing industry trends; or even presenting new investment opportunities to clients on “marketing meetings.” More than specialized finance knowledge or market intuition, she stressed the value of learning how to produce polished written work like essays, papers, and memos, since this translates directly into making client-ready deliverables at work.

That is not to say that a preprofessional major does not have benefits. Business economics is touted as more forgiving on students’ GPAs, which are one of the most consequential recruiting metrics, according to alumni. S., who completed the standard track of the economics major paired with Booth School of Business classes, contrasted her experience to that of peers who graduated from schools with dedicated finance tracks. “They have an upper hand initially.”

She added that students from those programs may know specific accounting rules or specific financial modeling techniques that S., as a UChicago economics student, said she was not prepared for. But these initial advantages dissipate quickly. “There’s a bigger learning curve in the first six to eight months. But after that, I do think what UChicago really prepares you for is looking at the bigger picture, which is also important as an analyst.”

CONTINUED ON PG. 9

“... [T]he tension between intellectualism and the pursuit of these careers does not arise from finance itself, but the architecture of the recruiting process.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 8

According to S., UChicago’s academic culture, particularly the Core Curriculum, worked synergistically with the demands of her job. “UChicago prepares you well for the broader picture—things that other people struggle with. It’s harder to get these soft skills unless you [have taken] all of these Core classes that we got to take, or [to] be thinking very critically.” Her advice to students is straightforward: take classes out of genuine interest, “because those skills are more useful in the job than taking preprofessional-type classes.” S. believes that the Core, which enables students to think both abstractly and practically, synthesize dense material into theses, read closely, and work under time constraints, develops skills that are more transferable to finance than one might imagine.

At UChicago, the history of finance as a discipline is intertwined with academic tradition, thriving because of the University’s emphasis on intellectualism rather than in spite of it. In an essay titled “A Brief History of Finance and My Life at Chicago,” Eugene Fama, hailed the “father of modern finance,” writes: “Finance has its birth in 1952 with the PhD thesis of Harry Markowitz on portfolio theory that he did in the [UChicago] Department of Economics.” In his time, he says, UChicago, the Massachussetts Institute of Technology, and Carnegie Mellon University “were [the] only three serious finance groups [of faculty] in the world.”

With this legacy, it is not surprising that UChicago is considered a “target school” for many top banks. A study using public LinkedIn data ranks UChicago at sixth place for top feeder schools for investment banking when adjusting for undergraduate class size. According to popular finance forums for recruiting, intelligence and work ethic are treated as “givens” for UChicago students. As one contributor on the Wall Street Oasis forum put it, all a UChicago student must prove is that they’re “socially competent and someone that other people will want to be around 16 hours a day.”

Mehta, too, believes the caricatures of the “finance bro” and the corresponding

label of “anti-intellectual” are misrepresentative. He described the cerebral energy of one of the finance RSOs he is a part of: “We really emphasize intellectualism, where you’re constantly researching, you’re finding contrarian views, [and] you’re pitching stocks and different ideas.”

Lee had a similar experience with RSO culture. “I found that the interview questions that clubs would ask turned out to be pretty interesting, like brain teaser–wise,” Lee said, adding that “it seemed intellectually pretty engaging and kind of up my alley.”

Technical interviews for quantitative trading are known for being rigorous, often including probability puzzles, betting games like poker, and quick-fire mental math questions to test mathematical logical thinking under time pressure. Since some trading roles require developing models to execute trades at high speeds, technical interviews also test candidates through timed “trading simulations,” requiring them to estimate the expected value of a game or design a coin toss with bid and ask prices. According to Lee, it was this challenge that drew him to quantitative finance in the first place.

If anything, both Mehta and S. suggested that the tension between intellectualism and the pursuit of these careers does not arise from finance itself but the architecture of the recruiting process. The parallel curriculum of finance recruiting rewards formulaic rehearsal and fluency over creativity, and preparing for it demands developing a strong grasp on accounting principles, memorizing “good” answers, and practicing one’s delivery in a way that comes off as confident and self-assured. “Everyone’s really nerdy about the finance stuff,” Mehta said. “I guess conventional recruiting takes away from it.”

The preprofessional culture that comes with finance, for many students, is more of a response to the hefty demands of recruiting than a true reflection of their approach to education. The compressed and unforgiving process rewards early and sustained preparation, which eats away at time that could be spent on classes. “The competi-

tion is so intense—sometimes you have to recognize the opportunity cost and focus purely on recruiting, and I’m not very happy [about] that,” Mehta said.

Early timelines are fundamentally difficult to reconcile with intellectual exploration when career certainty is demanded so early. The shift reportedly began in 2015, when the starting timeline for financial services moved from fourth-year toward third-year fall. In 2017, it fell toward the summer before third year, and in 2018 it was pushed to the spring of second year. According to one Yale University investment banking recruiter, the rationale for doing so is to beat other banks in the race to recruit the best talent.

With less time to wander academically, the space for experimentation begins to narrow.

S., recalling her second-year fall, echoed the sentiment. “My classes were kind of my second priority. I wasn’t doing much socially or in clubs that weren’t finance-focused.” Students don’t necessarily pride themselves on being preprofessional but acquiesce to the system’s logic to optimize for the tight recruitment window. To complement technical interview preparation, “people end up taking classes like corporate finance and accounting,” S. said. “And then your GPA also matters, so people will take classes that they consider to be easier to get a certain grade.”

In finance lexicon, a “superday” denotes the grueling final round of interviews in the banking recruitment process (often six to eight hours of back-to-back case, technical, and behavioral interviews, along with problem-solving assessments, designed to test performance under pressure). For each bank, students must also demonstrate deep knowledge about its recent deals, favored industries, and broader investing philosophy. Preparation becomes totalizing; it is no surprise that, in the days leading up to a “superday,” students withdraw from public and academic life to concentrate on preparation for the high-stakes event.

It is true that early recruitment has undeniable perks: “I remember signing my summer offer and feeling such a sigh of relief because you almost kind of have a

job lined up after college as a sophomore, which is insane to think about,” S. said. But, as timelines inch increasingly closer to the start of college, S. worries that the recruiting logic no longer remains a transient, situational adaptation. “When I first joined UChicago, I met a bunch of seniors that were really doing classes out of passion. There was definitely a larger group of students going into academia, exploring classes out of interest rather than to meet a certain job requirement.” Students now have fundamentally different priorities, she says.

When S. returned to campus to host informational sessions, she also noted that some students had started career planning as early as high school. They had completed serious internships even before they began college, which was not the case when she had joined UChicago. “There’s definitely a rise in the number of students that want to do [investment banking], but also [in the] preparation [of those students],” she said. For Mehta, commitment should not precede self-discovery. He believes preprofessional culture is an unhealthy mindset “for the people who are doing finance just for the lucrative, monetary benefit” while remaining uncertain about their interests. “I genuinely like investing. At the end of the day, what are you doing? You’re disagreeing with the market. I like to do that—that’s something I enjoy.”

But he’s also seen peers get pulled into the career by momentum rather than curiosity, constantly worrying that they are not doing enough to secure a job.“What does a 19-year-old even know? You’ve barely taken Core classes; you’ve barely gotten enough time to prepare your stock pitches or understand finance,” he said. S. agreed: “It’s absurd how early recruiting is.”

The summer before his first year, Lee attended the New York Career Exploration Week in Finance—a four-day visit to industry offices for incoming first-years organized by Career Advancement—to test whether the career was for him. “I get there. Everybody is already [business economics]. They know. They already know they want to work in investment banking…. They really have it all seemingly figured

“I took [classes like]

those are the classes I talk about the most with my seniors when we’re sitting at lunch.”

out. And I come here and club applications start immediately.” The pace was not what he expected at UChicago. “It just seems opposite to the core values,” Lee said.

Many students worry about the all-consuming role that the recruiting process has come to play in the undergraduate experience.

But S. hopes prospective finance professionals can recover some of the curiosity displaced during recruiting later in their undergraduate degrees. “I took [classes like] South Asian Sensorium, Black Panther Party, South Asian Music, and, looking back, those are the classes I talk about the most with my seniors when we’re sitting at lunch… [and that] I can actually ap-

ply in my conversations with a client. I’m not thinking about my accounting class as much.” It is not purely the soft skills, but the content of these classes that have contributed unexpectedly to her job.

Yet, postponing intellectualism to students’ third or fourth year is easier said than done. Recruiting often creates sunk cost, continuing to demand time from upperclassmen due to competitive return offers and RSO obligations. Preprofessional RSOs function as both a symptom and catalyst of the pervasive, prolonged culture. “The asks for a lot of the clubs keeps increasing,” Mehta said. “And there’s so much hype around club recruitment in the fall of your freshman year.”

Preprofessional RSOs are central to the recruitment process, and their role extends beyond community-building;

they take it upon themselves to teach the vocabulary and grammar of professional life early on through coffee chats, multistage interviews, and alumni networks. The process is rather ambiguous to outsiders, so advice usually circulates through informal channels, with finance-oriented upperclassmen mentoring second- and third-years.

In a college without a finance major, clubs do the heavy lifting in terms of career preparation and education, but they also create social bubbles that persist even after recruitment. “When you’re in these preprofessional pipelines, you get siloed into these careers, and there’s a lot of opportunity out there that is often unexplored,” S. said. The result is a closed ecosystem where recruiting logic continues to surround students, leaving little room for

independent curiosity to reemerge.

For this reason, S. urged students to “think other options through before you fully commit to investment banking.” Two years as an analyst is a big commitment, she said; even if it feels counterproductive, students need to actively make time to explore other curiosities.

“When this [recruiting] gets over, I kind of want to focus again on my classes, take harder classes, explore economics more,” Mehta said. Lee, on the other hand, has been enjoying Classics of Social and Political Thought, his social sciences Core sequence and hopes to take more “random” classes later.

“At some point, I want to take a linguistics class. If I was here just for learning, I’d probably major in linguistics. I’ve always found it interesting.”

The Maroon’s Anika Krishnaswamy recounts an unathletic person’s experience of the winter staple.

By ANIKA KRISHNASWAMY | Grey City Editor

During the second week of winter quarter, well before the sun can blink open its eyes, Henry Crown Field House fills with animal noises. Hisses, barks, and howls echo periodically through wooden walls, spilling into the icy street and alarming passersby who have not yet learned what winter sounds like at this school.

No, it’s not a secret meeting of lizard people or a band of pet store fugitives. It’s something far more unexpected and far rarer: UChicago students exercising. (More specifically, doing yoga.)

Arriving at that point in the quarter when the world seems permanently swathed in gray, Kuvia is a hallmark of winter in the College, an institutional attempt to make the season something more than just survivable. For one week, students file into Crown at 6:30 a.m. to exercise together. It’s baffling, I know.

Their only reward is a free T-shirt and the knowledge that they have done something both unnecessary and unpleasant of their own free will.

The tradition has its roots in two concepts. The first, from which its name descends, is kuviasungnerk, Inuit for “the state of feeling happy,” which can be an elusive condition in the depths of a Chicago winter—made more elusive still by the Campus North Residential Commons’ wind tunnel. In 1983, then Dean of the College Donald Levine sought to alleviate the stress of the season with a series of activities, including knitting contests, lectures on Arctic food, and readings of winter poems.

The second pillar is kangeiko, Japanese for “winter training.” Levine, an aikido practitioner, also encouraged students to complete a week of early morning exercises, rewarding perfect attendance with a

commemorative T-shirt. Now, each session also ends with a free bagel, a far cry from the event’s culinary origins in “kelp and raw fish,” which students claimed helped “promote both the kuviasungnerk spirit and the sense of humor.”

To many, these ideas seemed to be at odds with each other, one emphasizing relaxation and the other discipline. Levine would disagree. “Both notions seem to me to do a splendid job of solving the key problem of the Winter Quarter…. The key problem is how to define winter in such a way that it is no longer seen as a ‘problem,’” he told the Maroon in 1984.

Today’s Kuvia is a strange amalgamation of the two concepts: alongside the more “physical” sessions hosted by sport and dance teams are workshops run by the chess and origami RSOs, all organized by the Council on University Programming as a series of hour-long, exercise-adjacent mornings. The days build up to Friday’s dip

into the oft-frozen Lake Michigan—the Polar Plunge.

Settling into the Kuvia Routine

The first morning begins with an alarm at 5:45 a.m.: Apple’s “Kettle” trickles into my ear. I pry open my eyes and reluctantly extract myself from my comforter, a task that feels excessively difficult given that this was my choice.

The walk to Crown feels a bit like the witching hour. There are no cars, no people, no squirrels. Inside, students sit on the rough rubber floor, silent under fluorescent lights as they await their friends.

Sun salutations begin, drowsily, at 6:42 a.m. During cobra pose, my neighbor hisses at me sharply, her tongue jutting out in an unconvincing imitation of a snake. I hiss back.

As the week progresses, the mornings blend together. A ballet workshop reminds

“... [T]here’s a peculiar comfort to be found in the act of choosing discomfort together.”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 10

me why my childhood dreams of becoming a ballerina were abandoned. A session with the women’s rugby team confirms that I should never be entrusted with any task requiring significant hand-eye coordination. (To anyone who had the misfortune of receiving one of my passes, I apologize.)

By the third morning, I have accepted the way of Kuvia as my new reality: rising before dawn and anticipating ever so slightly more physical activity than usual.

Race to the Tower

People will tell you Kuvia is not competitive. These people have never attempted to secure one of the 50 spots on the Guild of Carillonists’ sunrise tour of Rockefeller Chapel.

The 20 seconds after the workshop is announced are like a pre-pandemic Black Friday sale. Once the 50 of us are selected, we begin the journey to Rockefeller.

We pack into the front pews of the chapel like sardines, elbow to elbow, awaiting instructions before we can make our way, single-file, toward the narrow, winding staircase—a 271-step climb. The exertion is unexpected. Everyone is sweating; everyone is exhausted; and some of us have been convinced that bell-playing may be our true calling, if only for the view from the top.

The sun is hidden behind the clouds, of course, but splotches of warm yellows and oranges burst through the grey here and there. Without a doubt, this is the most ex ercise I complete all week.

The Plunge Kuvia ends at the lake.

On Friday morning, we walk the mile to the Promontory Point bundled tightly in sweaters and scarves, slipping occasionally on ice. Eventually, we line up on the rocks like migrating emperor penguins, staring at the water as snowflakes pelt our faces.

Dean of the College Melina Hale leads us through the sun salutations that day. The hundred or so of us who have made it this far, including a student dressed in a polar bear costume, carry out our final downward dogs.

Students complete their sun salutations at Promontory Point on the final day of Kuvia, led by Dean of the College Melina Hale. anika krishnaswamy

Then it is time for the plunge.

In 1984, after what organizers described as a “wimpy winter” the previous year, Kuvia staff were reportedly “hoping for bad weather.” Given the half-frozen lake and shards of ice that slice at legs and feet as they go white, then blue, from loss of circulation, it’s easy to see why.

Snow continues to fall. The rocks are covered in ice, sending Kuvia participants slipping into the freezing water below. Everything is cold and wet.

I barely make it to my ankles before retreating, my hands and feet burning. Feeling doesn’t return to them until my Uber reaches campus, and even then, the pins and needles linger in my fingers and toes. (As I write this, some time later, I am still cold.)

Kuvia doesn’t make winter quarter easier, by any means, but it does make it communal, and there’s a peculiar comfort to be found in the act of choosing discomfort together.

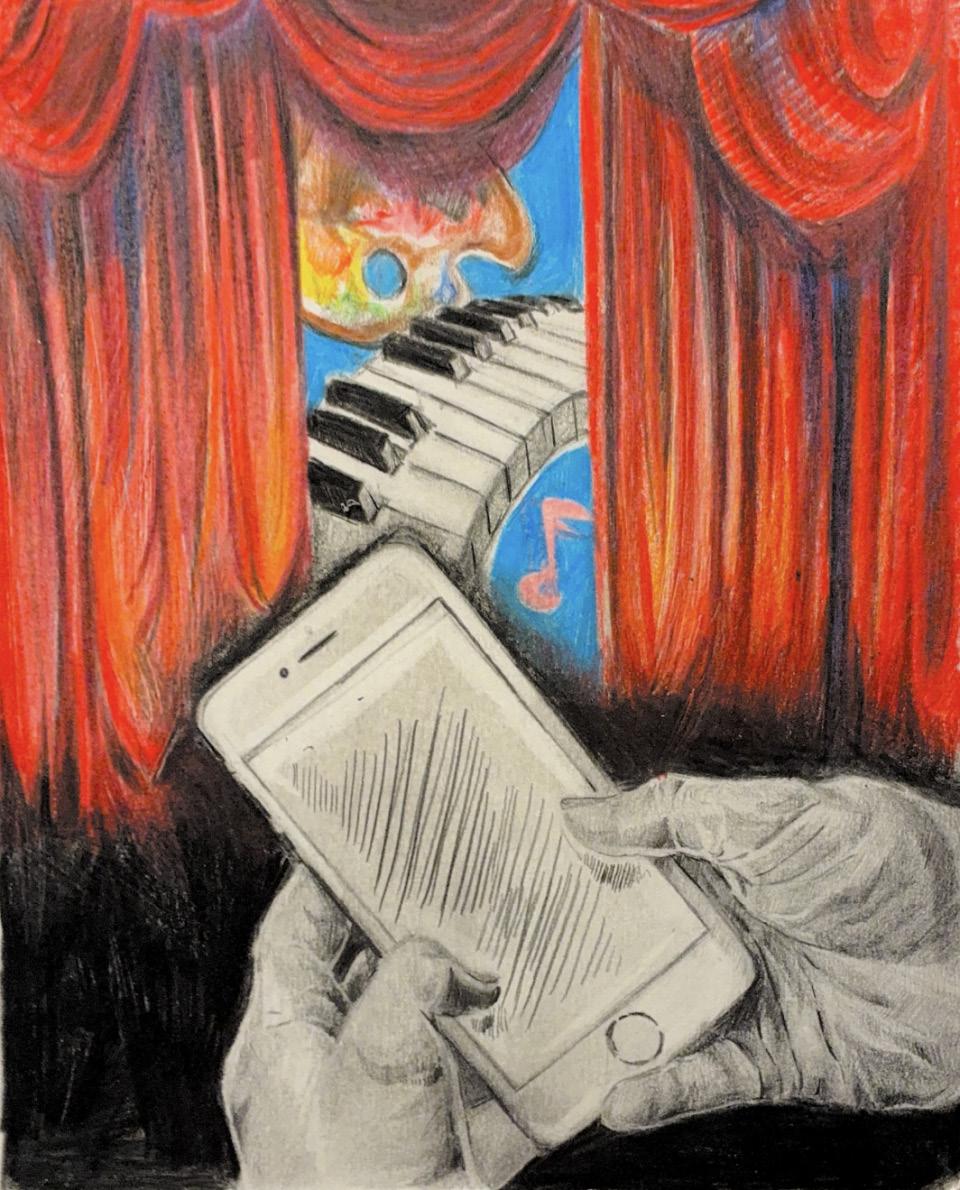

Devices should be left out of the parts of life where they do more harm than good.

By ALEK GIDEON

Earlier in the quarter, I attended a performance of The Lion King along with a cohort of students from my dorm. The musical was enthralling, yet every few minutes the conspicuous white glow of an iPhone’s home screen yanked my attention off the spectacle onstage and onto the stream of notifications quietly pinging in the lap of the student next to me. Disruptions of this nature are no longer uncommon, and we seem to have accepted the nagging presence of our phones as an unavoidable byproduct of our

attachment to the online world.

But I find it particularly worrisome how phones distract UChicago students—who chose to join a community rooted in the “Life of the Mind”—from fully experiencing the artistic dimensions of an intellectual life. UChicago’s curriculum theoretically attracts people with curiosity in all intellectual endeavors, from the hard sciences to the arts. For physics majors excited to explore the notion of human fate and English majors eager to enhance their computational reasoning, the Core Curriculum is an opportunity for growth rather than

a burden—a chance to expand one’s appreciation for subjects that they otherwise might never have explored and tap into interests they’ll never again have the chance to indulge. The arts Core, for instance, exists not to cultivate artistic mastery but to foster imaginative thought, contributing to a well-rounded intellect; nothing is expected of students who enroll in these classes beyond a willingness to explore. No matter what you intend to study here, approaching art with an open mind is central to making the most of the UChicago undergraduate experience.

As UChicago students, we must ask ourselves: Are we willing to let our phones invade the delicate spaces we reserve for creating and appreciating art? It’s true that our phones function as legitimately helpful tools. We rely on them for academic and social purposes, reflexively pulling them out between (and during) classes to refresh Outlook, take photos of the chalkboard, and coordinate dinner plans. But as these tools improve, especially amid the rapid development of AI, we must resist the inclination to integrate them into every aspect of our college routines. Instead, we

must separate them from the areas of life, such as art, where they do more harm than good.

To be clear, I’m not referring to art in its most broadly construed sense, which could reasonably include all types of creations, from TikTok videos to AI-generated images. I’m focused here on the kind of art that doesn’t heavily rely on phones or similar technology in its creation or presentation. There’s nothing inferior about crafts that use contemporary technology, but traditional art forms, such as printed novels, paintings, and live theater, have

CONTINUED ON PG. 12

“That shame springs from the part of our conscience that craves wonder... and recognizes that there is something hollow about an existence without art.”

existed for thousands of years without phones. We should keep them that way.

Aside from being addictive and distracting, like at The Lion King, phones undermine our engagement with these traditional art forms. For one, they weaken our curiosity. Search engines, and now AI chatbots, give us access to unfathomably vast amounts of information, which is collected, organized, and delivered to us within seconds of our search. While I celebrate the way the internet has made information more widely accessible, and I don’t dream of returning to a pre-internet era, the ease with which we find content online trains our brains to expect answers to all inquiries, atrophying the part of our mind that relishes sitting with the unknown.

Art, in contrast, thrives on the unknown. It contains not an abundance but a dearth of information. I was forced to deal with that scarcity when I first saw Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The painting depicts a man standing atop a mountain, his back facing the viewer as he takes in an immense landscape beyond. As I looked at the painting, I wished I could see the expression in the man’s eyes. I wondered if he feared the jagged expanse or admired it. Was he preparing to lean confidently over the edge or slowly back away? Of course, I could not search online for the answers to these questions. And though I found myself craving an online explanation to clarify the mystery of the painting, I ended up making my own story out of the clues that Friedrich provided. Just as the wanderer confronted the sea of fog, I squinted at the unsolvable painting, fighting the urge to find the right answer and instead em-

bracing the joy of finding the right question.

It’s difficult for our minds to embrace tough questions when we fill every bit of our free time with our phones. We doomscroll for hours straight, but we also fill the little pockets of unstructured time—time during which we’re meant to think without constraint—lost in our phones. Go to any dining hall and you’ll see a large number of students eating while hunched over their devices, even when sitting with friends. Our obsession with productivity, our desire to feel like we’re doing something, though usually a helpful mentality, hurts us by rationalizing this as time well spent that we would otherwise waste away in the solitude of our own thoughts.

But these short instances of free time, whether waiting for the elevator, eating a sandwich alone, or lying in bed at night, give us a chance to reflect. Usually, my uninterrupted thoughts consist of nothing more than catchy songs (such as “The Circle of Life”) and annoying recollections of the last stupid thing I said to someone. Yet, in other moments, I’ll mull over a confusing chapter of the novel I’m reading or, if I’m passing through the quad, spontaneously look up at University’s embellished rooftops. In these mini periods of reflection, I let my mind go where it pleases. There’s no pressure to think efficiently or make progress—the very notion of efficiency is antithetical to art. As New York Times Book Review critic A. O. Scott said during a panel on art and literature, we should not attempt to suppress our boredom because a wandering mind engages in the creative process of connecting disparate ideas. This isn’t to say that we should contemplate the meaning of life every time we see a sculpture. We must

not, however, deprive our minds of the space it needs to grapple with ideas it finds compelling. Perhaps most detrimental to our engagement with art is the way our phones weaken our ability to empathize. Social media boosts aspects of our communication by keeping us in contact with hundreds of people at once. Yet by dispersing our attention across so many profiles, we spend less time forging deep connections, which are central to creating and appreciating art. In a recent University Theater production of Our Town, I played a character named George Gibbs, who lived in a small New Hampshire town over a century ago. Embodying George meant imagining, partly through my own experiences, what it would feel like to be reproached by a close friend and reprimanded by a father. It meant genuinely caring for George, his family and friends, and the seemingly mundane yet entirely authentic world he inhabited. Rather than splitting my attention among hundreds of people online, I focused my thoughts on the other characters onstage. Rather than taking in endless streams of stimulating content featuring people and events around the world, I listened carefully to and cared deeply for a small but meaningful group of people. Kevin Otos and Kim Shively write in Applied Meisner for the 21st-Century Actor that actors (though it is true for audiences too) must learn to empathize with the play’s characters because “there is an element of love for anyone that is worth your full attention.”

How can we repair our relationships with art? We might take inspiration from the schools across the U.S. that have begun banning phones for students. By instating phone-free zones, kids learn to value thinking without

the distraction or assistance of technology. I appreciate my humanities Core class at UChicago for similar reasons. The class takes place in the Regenstein Library’s Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, which prohibits students from bringing most of their belongings into the classroom, giving me an incentive to part from my phone for a glorious 80 minutes. During class, I’m free to interpret the Iliad without the familiar weight of a phone in my pocket reminding me that ChatGPT could spit back an answer to every one of my questions.

But, while physically separating ourselves from our phones gets us closer to appreciating art, the habit alone won’t be enough to curb society’s unceasing push for technological integration. If we want to resist that push, we must shift our mindset toward phones by embracing the guilt we feel for our addictions. Most of us cringe when we check our screen time and calculate the hours per week, month, and year that we spend consumed by our devices—and we should feel ashamed. That shame springs from the part of our conscience that craves wonder, values empathy, and recognizes that there is something hollow about an existence without art. As UChicago students, with the privilege of attending a school dedicated in large part to the enrichment of the creative mind, we can either let our phones continue to encroach upon our lives or make an intentional decision to keep them out of certain spaces. At stake is our appreciation of art, which is to say, our appreciation of each other.

Alek Gideon is a first-year in the College.

Ken Nakagaki uses art and technology to help his audience see new perspectives.

By DENIZ KURDI | Arts Reporter

Can technology be art? The question has been gaining traction, especially as artists and installations melding the digital and the physical have entered the public milieu. On the third floor of John Crerar Library, where UChicago’s computer science department is based, one answer can be found from Ken Nakagaki and the AxLab. The lab is one of UChicago’s many computer science research labs, but it is distinguished by its unique specialty in tangible technology.

The “Ax” in “AxLab” stands for “actuated,” which has two meanings: to put into mechanical motion and to move to action. The lab uses both meanings of the word, building “actuated” technology to bring us out of our screens and into our lives. This clever word choice, which summarizes the philosophy of the lab, is meaningful for Nakagaki, the AxLab’s director and an assistant professor in the Department of Computer Science. He believes the actuated technology that AxLab is researching can actuate people to enact change in the world by shifting their relationship with technology.

At its core, AxLab’s mission is about creating a better future relationship with technology. In the world the AxLab is building, technology blends with our physical spaces, breaking free from the flat screens that suck us in. For Nakagaki and the AxLab, more interactive, physical forms of technology can help bring us back into our tangible reality.

Because their technology is all about physicality, it is often surprisingly artistic. Take AeroRigUI, which imagines how we can better use wasted space through robots which play on a ceiling and dispense lengths of string in a unified ballet. The robots demonstrate technology’s ability to change our relationship with our built environment, but they are also aesthetic and playful. The robots themselves have an appearance of danc-

ing fishing spools, which whir around to allow their held objects to float and sink.

Threading Space unites spatial interaction between the ceiling and the floor by connecting threads between them, allowing new expression through kinetic sculptures that can turn themselves in knots. Viewing the project leaves one with a powerful impression of unity in technology. It uses complicated robotics with simple ropes to create a unique artistic installation. The sculpture requires a great degree of precision since the robots have to move in perfect sync to keep the strings taut, and the result is a dance that rests on the razor’s edge of failure as the robots stutter around each other, binding themselves further together. This requires a great degree of thought into how to use technology and the physical space it inhabits.

Buoyancé explores novel ways to implement helium for robots to float in midair. This description does not convey the ethereal dancing balloons that you see when this technology is artistically showcased. A simple explanation about the project cannot do justice to the beautiful possibilities that it might hold for the future. Just describing the project as floating helium robots does not elicit the excitement for future possibilities that Nakagaki’s elegant exhibition evokes.

To better understand how art plays a role in his creative process for innovation, I spoke with Nakagaki. He said that the ability to switch perspectives between an artist and a researcher is extremely important: “It’s really cool to have an interdisciplinary view. You can wear a hat of the researcher, but once you wear a hat of the artist, you start to find a new value in research and technology.” Nakagaki finds that his different roles tend to build off each other, which is why he doesn’t really view art and technology as two separate things. “When I’m doing research, I come

up with a new idea that could be used for art. While I’m doing art, it gives me a new idea about technology.” Nakagaki is a believer in the power of art and technology to see new perspectives and holds that it can be useful to get people thinking about the world they’re going to live in—and especially about what the spaces they’ll inhabit will look like.

Nakagaki also believes in the ability of art to reach a wider audience and bring different perspectives into conversations about the future. This interest in interactivity began in Tokyo, where Nakagaki was inspired by a range of interactive media and art festivals. He realized he could use interactivity and art to go beyond the strictly pragmatic side of research. “I want [my exhibitions] to be a vehicle to look at the future, discuss the future, and give people inspiration about what the future could be,” Nakagaki said. It is his aim that his prototypes serve as “torches” to “illuminate the future” and inspire others to think differently about it.

Much of what Nakagaki envisions is physicalizing our interaction with tech-

nology. With most of our engagement with technology now taking place on a flat screen, Nakagaki misses the innovation and variety in some earlier technologies like flip phones. At its core, what’s lost in this change is creativity. The internet, much like the screens that it takes place on, has become too smooth for Nakagaki. It is too easy to stay online. Projects from the AxLab like the Attention Receipts strive to use physical objects to remind us of the real costs of the digital world. Using tangible interfaces in a creative and thought-provoking way can increase the tension in our relationship with technology, pushing us to spend more time in reality.

In our age of uncertainty about the future role AI and technology will play in our lives, Nakagaki explores a more optimistic vision. This vision is one where technology is brought out into reality instead of pulling us further away from it. Communicating this vision is no easy task, but Nakagaki understands that the best way to do so is by “wearing the hat of an artist.”

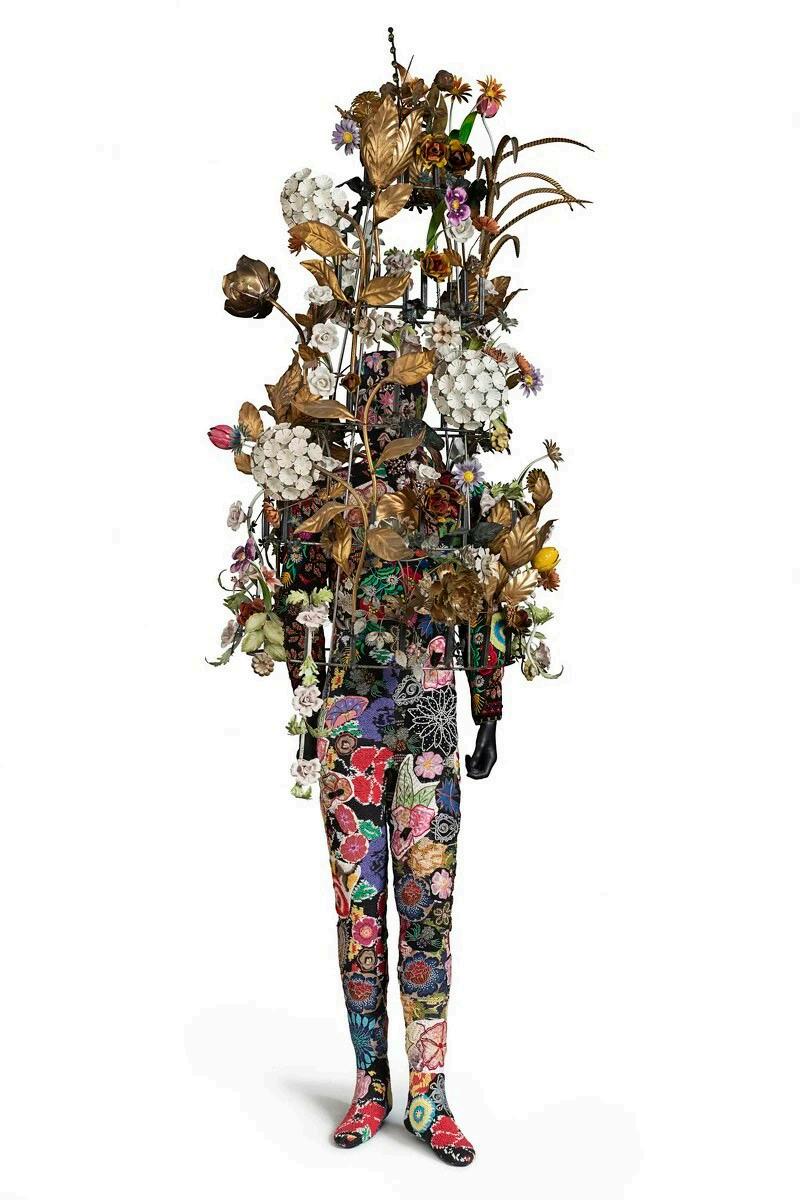

MCA Chicago’s newest group show offers an intergenerational look at art, activism, and the hidden sites of LGBTQ+ life in Chicago.

By ELIAS BUTTRESS | Associate Arts Editor

Chicago tends to think of itself as a city defined by its neighborhoods, movements, and grassroots organizing. A recent show at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA), City in a Garden: Queer Art and Activism in Chicago, posits that queer art and activism are key to Chicago history and belong squarely within the city’s civic identity—even if they have often been written out of the official record.

Per the exhibit’s wall text, City in a Garden is a group show about queer art and activism in Chicago from the 1980s to the present. The exhibition chronicles the LGBTQ+ community’s response to the AIDS crisis and the U.S. government’s mishandling of it. In the wake of this devastating event, LGBTQ+ artists and activists turned their anger and grief into art and activism. Through this radical shift in LGBTQ+ history—when visibility became unavoidable, the community expanded, and politics became paramount—activists reclaimed the historically pejorative epithet “queer” as a liberatory term to describe anyone who purposefully deviates from cis-heteronormative society. In doing so, activists made art that aimed to reclaim agency and open new paths to visibility and expression.

The exhibition explores queerness spatially, whether in private, public, or imagined spaces. These spaces, oftentimes hardwon and tenuously held, provide respite

from the hostile and restrictive aspects of society. The show is arranged into five galleries. The “garden” and “club” show spaces of community and care with various sculptures, photographs, and paintings; the “street” openly depicts the visibility and history of Chicago’s LGBTQ+ activists through film and protest materials. The “cinema” and “utopia,” meanwhile, consider the temporality of queerness through film and artworks. These spaces allow the featured artists to reveal quiet moments of intimacy and community, push back on traditional views of gender and sexuality, and thus blend their art with activism.

One of the show’s most visually striking pieces is Amina Ross’s 2021 short film Man’s Country. A massive screen situated in the corner of a gallery provides an enveloping experience. Inside, the disembodied viewer floats through a digital recreation of the titular gay bathhouse, once the oldest in Chicago, before it closed in 2019. Ross lived down the street from the site, using photos and footage to rebuild its interior. Multiple voice-overs speak poetically throughout, narrating a change to come. The rendering begins to break down as the film progresses, until it is nothing more than parts of the interior floating in the ether. Watching this installation piece, I found myself asking questions about the bathhouse’s history. Because the space is digitally recreated and dissolves, the film reflects on imper-

manence and community resilience. Man’s Country serves as a meditation on how queer communities navigate impermanence, memory, and survival from within the wreckage.

Through Ross and other artists, City in a Garden foregrounds histories of spaces and networks that shaped queer life in Chicago—many of which have been overlooked. A significant portion of the show highlights ACT UP/Chicago, the AIDS awareness activist group that forged networks of care, protest, and community throughout the city from the late 1980s to 1995. The group’s first and most popular T-shirt design, “Power Breakfast,” lies at the start of a lengthy vitrine full of flyers, news coverage, and press releases about the group. The title of the show is a reference to Chicago’s official motto, Urbs in Horto. It also alludes to a show motif: Montrose Point Bird Sanctuary, a discreet yet vital gathering place for Chicago’s LGBTQ+ community along the lakefront. In both Chicago generally and at Montrose Point specifically, urban spaces function as delicate yet crucial spaces of queer life and community.

The exhibition brings together the AIDS-era generation and post-AIDS generations of queer artists, juxtaposing archival footage with contemporary works that confront present threats to LGBTQ+ communities. Visibility and the fragility of queer spaces are themes transcending time, lending the show an undercurrent of urgency. From virtual recreations of historic sites

to new explorations of queer life, the works collectively emphasize the precariousness and resilience of LGBTQ+ spaces today, nurturing the same garden-like sanctuaries evoked throughout the show.

City in a Garden presents these histories and visions as a reminder that Chicago can still nurture intimate spaces where queer life, art, and activism flourish, even in the most uncertain of circumstances.

City in a Garden: Queer Art and Activism in Chicago is on display through August 16.

At the Museum of Contemporary Art’s sprawling retrospective, Yoko Ono commands a cacophonous presence.

By CIARA BALANZÁ | Arts Reporter

It’s not every day that a giant fly buzzing over a naked body is projected onto a screen. You can witness this characteristically provocative film until February

22 at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) in Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind. The seminal retrospective is an evolution from a Tate Modern exhibition that traces

the trailblazing artist’s career. Although best known for her artistically prolific and romantic partnership with Beatles

“What are the boundaries of the viewer and designer in creating art?”

CONTINUED FROM PG. 14

singer John Lennon, Ono’s creative oeuvre extends far beyond her late husband. That the 92-year-old’s pioneering work in contemporary art still feels fresh is a testament to this. A boundary-defying spirit pulsates through every curated artifact from Ono’s imaginative world.

Upon entering the sprawling exhibit at the MCA, I did in fact feel that I was exploring a previously unknown territory of my mind. The museum’s floor-to-ceiling windows and airport-like corridors evoke a liminal space perfectly suited to a famed conceptual artist. With art that poses a riddle for viewers to answer, Ono’s intention is to “induce music of the mind in people.” She labels the “mind-world” as a space where ideas transcend the confines of the individual and time. In this boundless territory, spectators are invited to explore their imaginations and memories.

In keeping with Ono’s artistic philosophy of provocation, the exhibition is structured to allow viewers to intimately partake in the worlds of Ono’s creations. Overtaking the hallway is a collection labeled “Personal Is Political.” In Wish Tree (1996–present), viewers are called to write their hopes on paper and hang them on a tree. The lush trees are a nexus of activity, and viewers become a part of the art piece as they mill about and hang their hopes. The sociality of the activity fulfills Ono’s desire for you to “ask your friend” to also make a wish.

The piece was surprisingly emotional, and I recalled memories of hawthorn trees in Ireland. I felt a visceral connection to my past wishes and my future

desires. One of Ono’s goals is to cultivate a personal relationship with art that exceeds typical boundaries. Wish Tree is a great example of this.

While the wishes were oriented towards the future, Ono’s other works implicate viewers in the present. In The Blue Room Event (1966), a white chamber recreates a show Ono has staged many times in her career, in places including New York, Lyon, and London. Participants walk through a room inscribed with scribbles that share a different interpretation about what the room could be like. By using imaginative powers, the viewer is bidden to extend the possibilities of the environment at hand. A gentle smile came on my lips as I read, “Find other rooms which exist in this space,” prompting me to create a blueprint in my mind’s eye. The room challenges the solid fabric of society but also summons us to participate in its fashioning. It exemplifies Ono’s driving question: “What are the boundaries of the viewer and designer in creating art?”