THE ENDURING APPEAL OF SNAKES

AND LADDERS

17 Ibid. Part 6, Chapter 6, p. 518.

18 Ibid. Part 6, Chapter 6, p. 522.

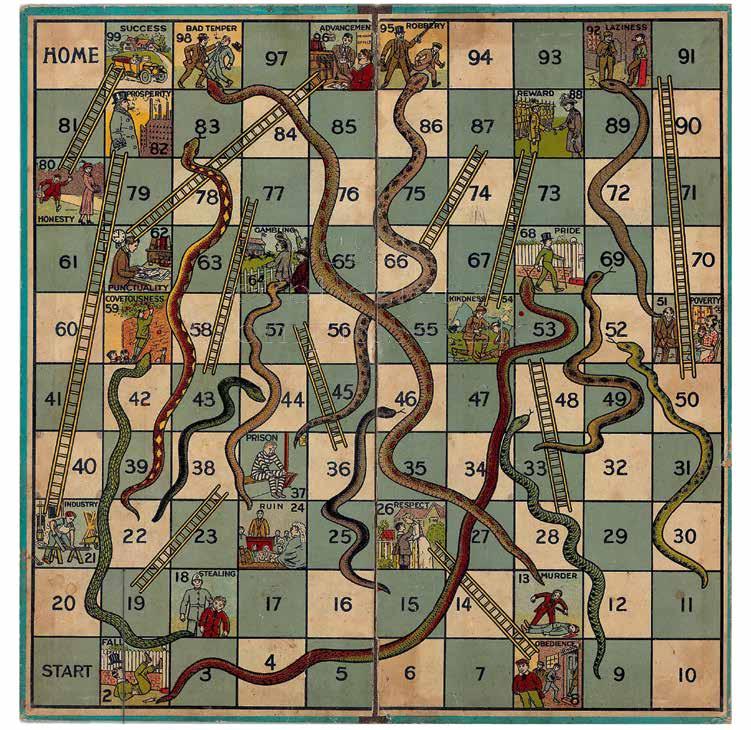

The popular dice-game Snakes and Ladders originated in India in the late 17th century in three sectarian variants: Jain, Hindu and, more rarely, Muslim.1 Players of all three versions competed to ascend to the highest level of spiritual enlightenment via ladders representing virtue, or righteous action as prescribed by scripture They could be cast down at any time if they landed on snakes, representing vice and folly. The game is notable for its balanced combination of devotional, didactic and recreational qualities, a rarity in games of chance. Some early versions of the game board were designed for display rather than use, thus serving a devotional purpose. Many are of considerable beauty, such as the Maharashtra gouache presented to the Royal Asiatic Society in 1831 by Major Henry Dundas Robertson.2 The widespread Hindu variant of Snakes and Ladders eventually found its way to the West from British India in the late 19th century. It was successfully marketed in Britain by Spears Games Ltd and in the USA by the Milton Bradley Company. In these Western versions, Christian values replaced Hindu ones, though the snakes and ladders, universal and instantly legible symbols, were retained. This is unsurprising: both ladder and snake gure as archetypes in the symbolism of a wide variety of cultures and belief systems3, including Christianity and Hinduism4. In his novel Midnight’s Children, Salman Rushdie interprets the game as a telling representation of the human condition.

All games have morals; and the game of Snakes and Ladders captures, as no other activity can hope to do, the eternal truth that for every ladder you hope to climb, a snake is waiting just around the corner, and for every snake a ladder will compensate. But it’s more than that; no mere carrot-and-stick a air; because implicit in the

1 Tops eld, Andrew (1985) “The Indian Game of Snakes and Ladders” in Artibus Asiae 46:3, pp. 203–26; pp. 85–86 and Tops eld, Andrew (2006) “Snakes and Ladders in India: Some Further Discoveries” in Artibus Asiae 66:1, pp. 143–79.

2 https://royalasiaticcollections.org/ras-051-001-snakes-and-ladders/

3 Eliade, Mircea. Patterns in Comparative Religion. London; New York: Sheed & Ward, 1958. pp. 102–108 ladders) and ibid. pp. 164–169 (snakes).

4 Judaeao-Christian examples are the Nachash the cunning serpent that tempts Eve (Genesis 3:1), and the Saraph, the ery serpents inhabiting the desert wilderness (Numbers 21:4-9) whose venom and its e ects represent the burning wrath of God. Notable Hindu serpents include Kāliya, a gigantic poisonous snake eventually subdued by Lord Krishna (Bhagavata Purana 10:16).

game is the unchanging twoness of things, the duality of up against down, good against evil; the solid rationality of ladders balances the occult sinuosities of the serpent; in the opposition of staircase and cobra we can see, metaphorically, all conceivable oppositions, Alpha against Omega, father against mother.5

The example shown here is a mid-20th century Indian version [Fig. 1], still in production by the Kreeda6 games company. It o ers a compelling Anglo-Indian fusion of Eastern and Western values and imagery, a departure from the Spears and Bradley editions, which had fully replaced Hindu with Judaeo-Christian concepts. The name, Paramapada Sopanam, literally means “Steps [sopanam] to the Highest Place [paramapada].7 This is often translated as the “Ladder to Salvation”, strikingly reminiscent of the Christian “Ladder of Divine Ascent”. In fact a more appropriate translation of sopanam would be not “ladder” but “staircase”. It is helpful to visualize the 134 squares on the board as steps, and the ladders as potential shortcuts from lower to higher steps. The ten ladders in this version are given English names, representing Christian virtues — honesty, concentration, hard work, courtesy, helpfulness, determination, dedication, compassion, wisdom and contentment. The thirteen snakes bear the Sanskrit names of demons, each embodying a fatal vice: lust, tyranny, cruelty, greed, ambition, sloth, jealousy, overcon dence, anger, pride, vengefulness and arrogance. It is easy to see how the game in this format might provide a useful point of departure for illuminating discussion between parents and children, or serve as an educational tool at a higher level, as well as being an enjoyable pastime.

In recent years the game has been adapted to accommodatea broad spectrum of secular aspiration — no surprise, given the archetypal appeal of its imagery, which isas adaptable to the material world as it is to the moral and spiritual. In these modern adaptations, the didactic quality of the game is retained, though reward and punishment are to be had in the here-and-now rather in the hereafter. However, despite the dramatic shift of emphasis, the symbolic potency of the snake and the ladder are undiminished. “Move Up In Life With Healthy Habits” features a ladder of Fruit and Vegetables and a snake of Fried Snacks and Bakery Products. “Corporate Snakes & Ladders” features a Work on Sunday ladder and a Lied on CV snake. The Mahila Housing Trust in Ahmedabad has developed a version designed to teach the urban poor how to combat unsanitary living conditions. Snakes include Drinking Contaminated Water, along with a ladder of Investment in Children’s Education. The University of Cape Town has devised a “Coming Out” Snakes and Ladders, designed to help gay men and women come to terms with their sexuality.

5 Rushdie, Salman. Midnight’s Children. London: Random House, 2006. p. 160.

6 https://www.amazon.in/Kreeda-Parama-Pada-Sopanam-Traditional/dp/B07XKCJ2XM

7 The game was known by various names in India. The Jain variant was known as Gyan Chauper (the game of wisdom), the Hindu variant Moksha Patam (the ascent to salvation), the Muslim variant Shatranj-al-Ari n (the chess of gnostics). See Tops eld op. cit. (1985 and 2006) for further elaboration.

Regardless of how purists might view these innovations, their existence certainly bears witness to the enduring power of the snake and ladder archetypes. The very orderliness of the game — its reassuring compartmentalization of good and evil, rise and fall, light and dark — lends itself to all manner of persuasive modi cation. On this seductive orderliness, Rushdie sounds a note of warning: “I found, very early in my life, that the game lacked one crucial dimension, that of ambiguity — because, as events are about to show, it is also possible to slither down a ladder and climb to triumph on the venom of a snake.”8 Dark though it is, one could argue that this remark enhances rather than diminishes the appeal and utility of the game, leading players to question the complexitiesof ascent or descent, whether spiritual, moral or material, embodied in the deceptively simple imagery.

Robin Saikia Historian, writer, author of “The Red Book” (Foxley Books)

Kismet. Historian, writer, author of “The Red Book” (Foxley Books) “Snakes and Ladders”. c. 1985, chromolithograph board game

8 Rushdie. p. 160 op. cit.

Co ee Plantations, Yemen

Ritual cleansing pools, Jami' al-Mansur Complex, Amran, Yemen, XIII century

Jami' al-Mansur Complex, Amran, Yemen, XIII century

Jami' al-Mansur Complex, Amran, Yemen, XIII century

Jami' al-Mansur Complex, Amran, Yemen, XIII century

Jami' al-Mansur Complex, Amran, Yemen, XIII century

Paul Strand , The Entrance from the book Un Paese: Portrait of an Italian Village, 1955, photograph

Etruscan stairs cut from the ground, Northern Italy, c. 500 BC, photograph

Steps, Malaysia, photograph

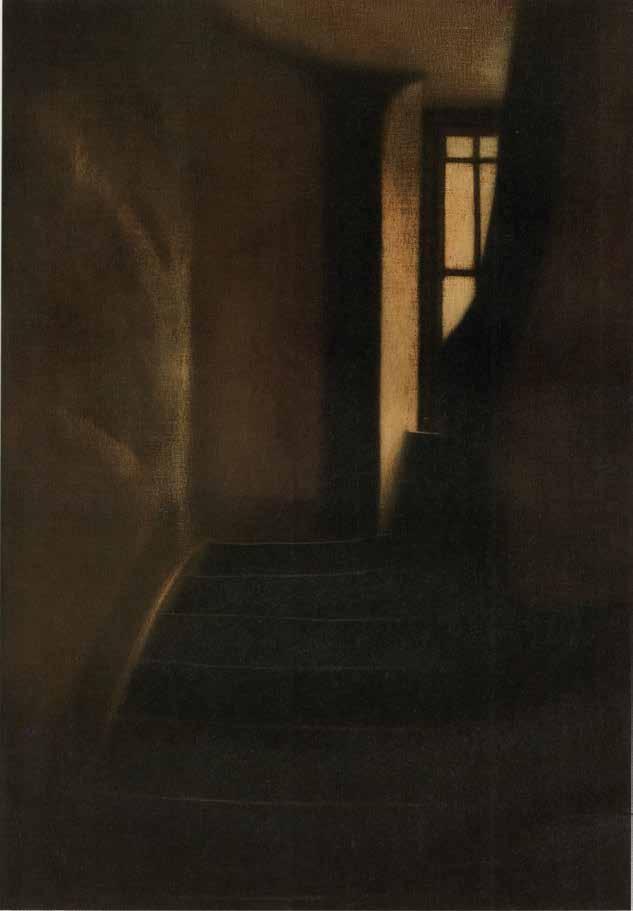

Sophie Walraven, Stairs, oil on canvas, 115 × 74 cm

Giuseppe Penone, Contour lines, 1989, cast iron, 50 × 150 × 200 cm

Bennett Greig, The summit of the Intihuatana Rock, Machu Picchu, 1938, photograph, 23.7 × 17.6 cm

Antoni Tapies, Ladder, 1988, chamotte clay, 57 × 77 × 81 cm

Susana Solano, Fontana № 3, 1985, iron, 88 × 208 × 196 сm

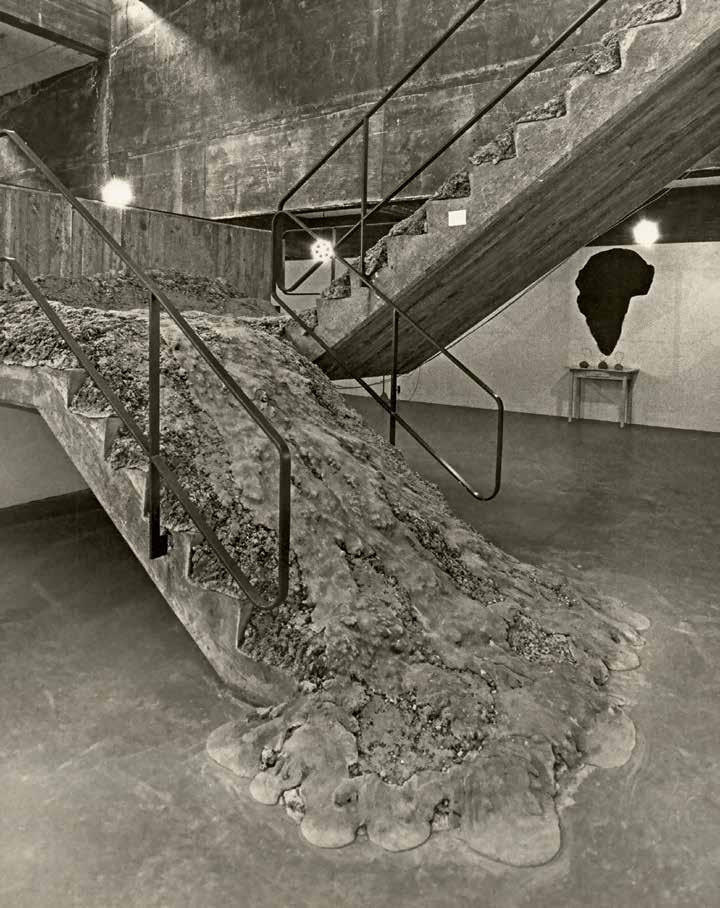

David Ireland, Smithsonian Falls, Descending a staircase for P.K. 1987, installation

Mihail Chemiakin, 2011, photograph

Jami' al-Mansur Complex, Amran, Yemen, XIII century

Jean-Marc Gourdon, 2007, photograph

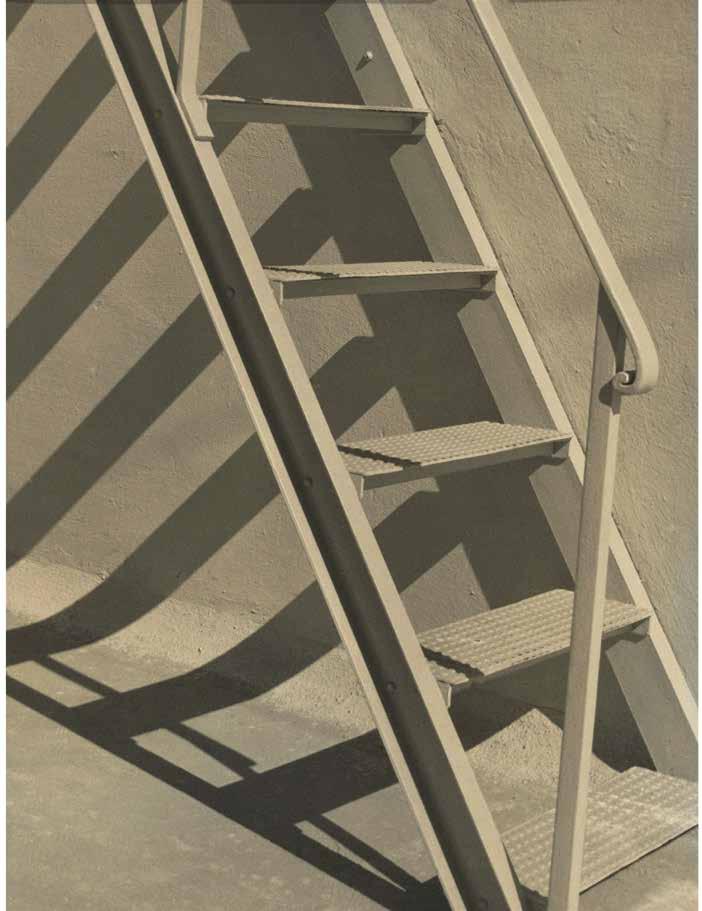

Alma Lavenson, Calaveras Dam II, 1932, printed 1983, photograph, 25.4 × 20.3 cm

Imogen Cunningham, Mills College Amphitheatre, c. 1920, photograph, 21.5 × 19.6 cm

Julia Szilagyi, Up or down? 1999, photograph, 28 × 32 cm

Mihail Сhemiakin, photograph

Jantar Mantar sundial, 1734, stone

Anselm Kiefer, H2O, 2005, oil, crayon and photo-collage on paper, 101.5 × 140 cm

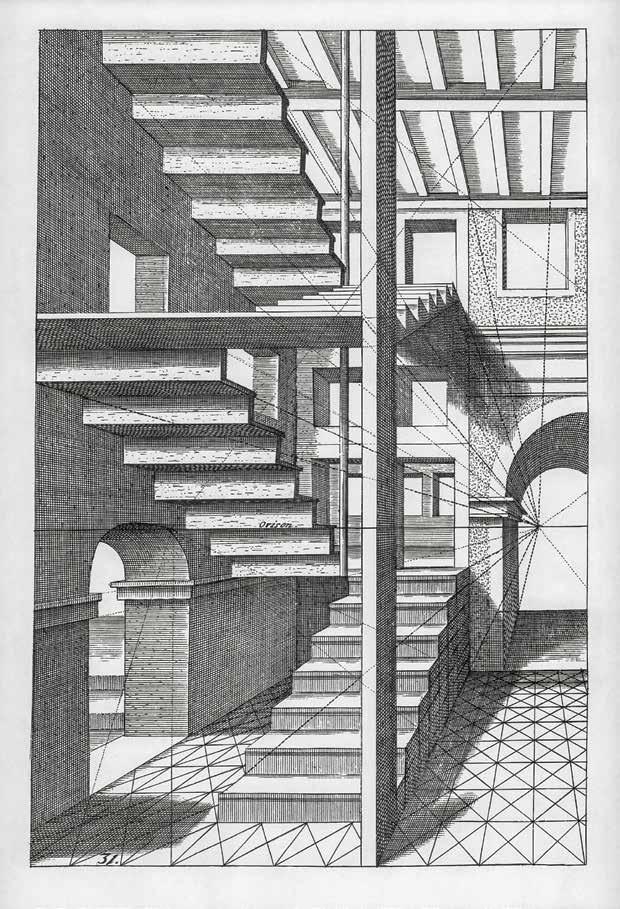

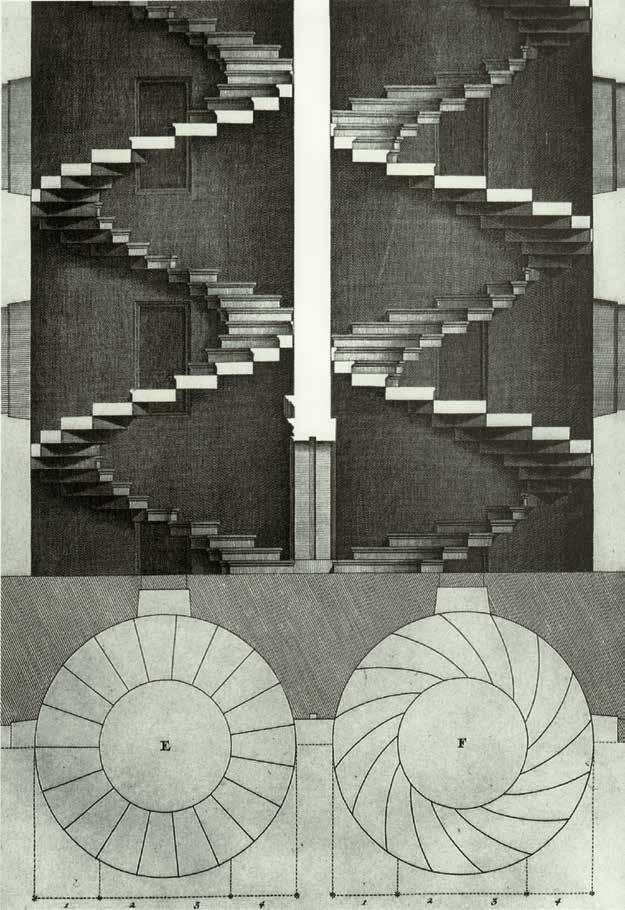

Hans Vredeman de Vries, Stairs in perspective, 1605, copper engraving on paper, 28.6 × 19.2 cm

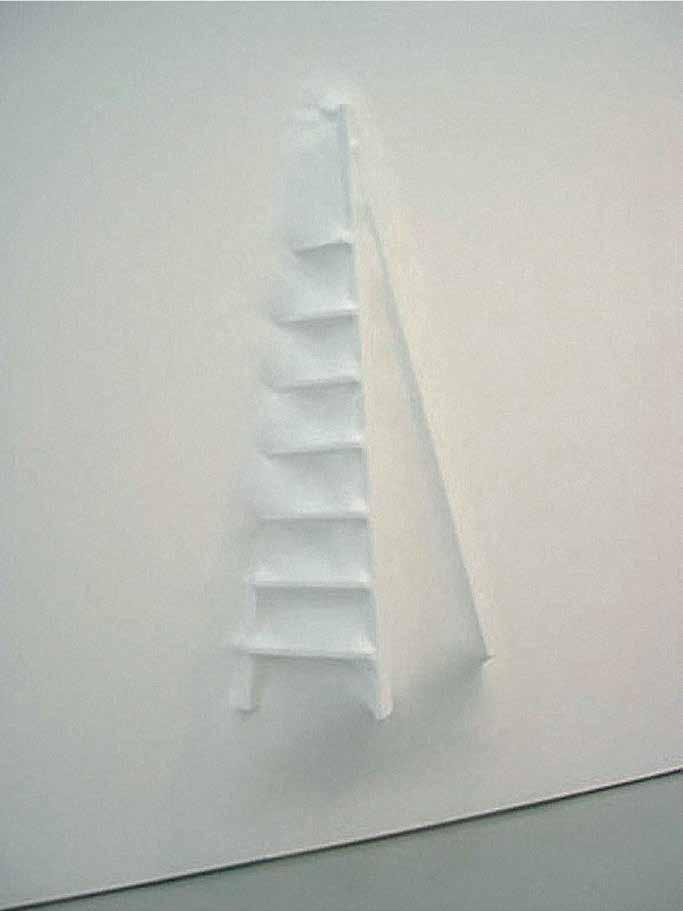

Rachel Whiteread, Untitled (Stairs), 2001, plaster, berglass, wood, 375 × 220 × 580 cm

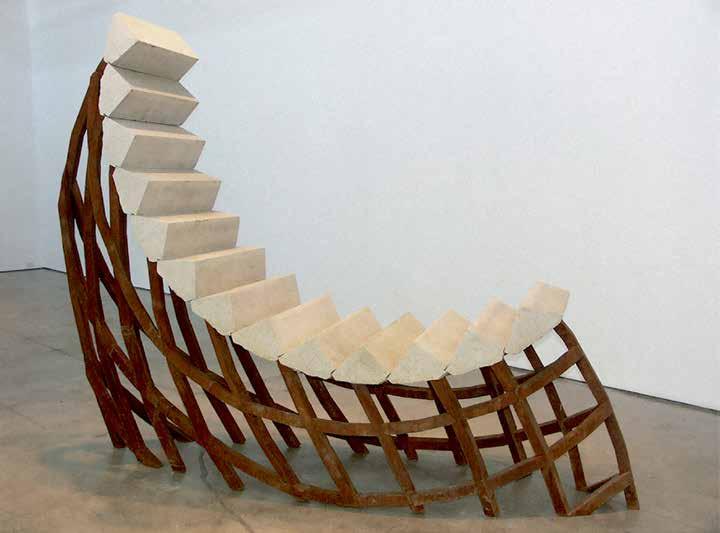

Magdalena Jetelova, Stairs, 1982–1983, wood, metal, 510 × 310 cm1*

Erik Johansson, Perspective Squarecase, 2009, photomontage

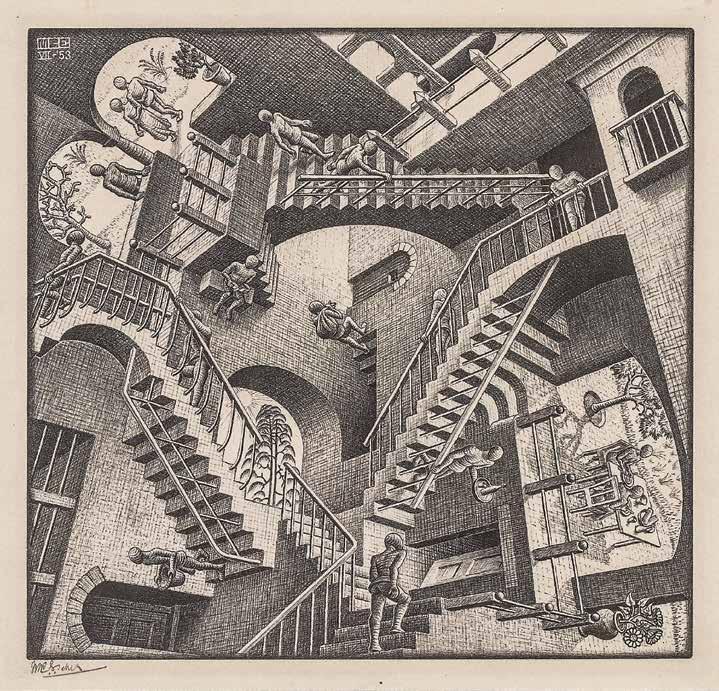

Martina Casey, Escher inspired scenography, 2017, paper, cardboard, scotch tape, sponge, brushes, scissors2

Maurits Cornelis Escher, Relativity, 1953, lithograph, 39.3 × 39.5 cm

Madalina Zaharia, Artist Talk I (twenty slides and two words), 2018, digitally printed canvas, metal shapes and curtain pole, 240 × 180 cm

Carlo Scarpa, Brion Cemetery, San Vito, Italy, 1968–1978, concrete

Adam McEwan, Staircase 2016, wood, steel, 570 × 390 × 120 cm

Rachel Whiteread, Untitled (Basement), 2001, plasticized plaster, 325.1 × 657.9 × 368.3 cm

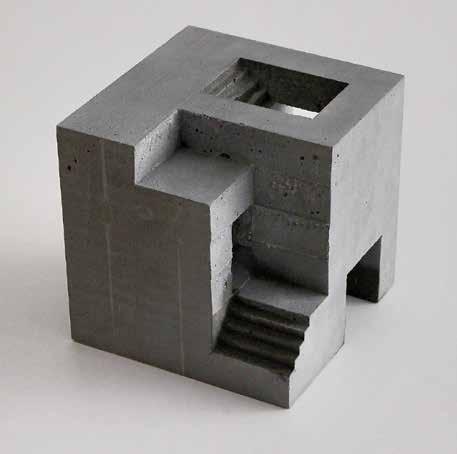

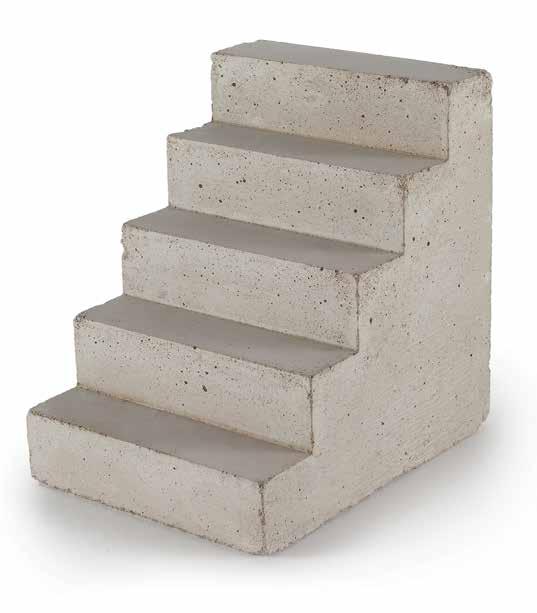

David Umemoto, Stairway to Nowhere, 2017, concrete, 22.9 × 7.6 × 30.5 cm

Rachel Whiteread, Untitled (Stairs), 2001, plaster, berglass, wood, 375 × 220 × 580 cm

Hubert Kiecol, Ways 1992, wood, paint, each 33 × 25 × 33 cm

Mimmo Paladino, Souvenirs, 1990, mixed media on wood, 63 × 62 cm

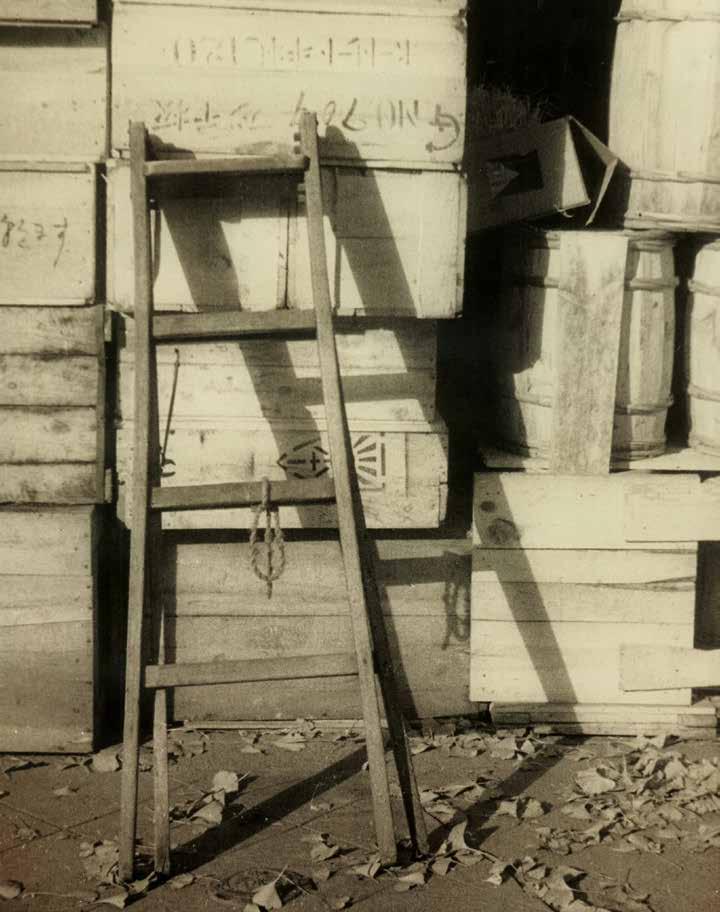

Edward Weston, MGM Storage lot (Stairs), 1939, photograph

Edward Weston, MGM Storage lot (Stairs), 1939, photograph

Charles Demuth, Stairs. Provincetown, 1920, watercolor and pencil on board, 59.7 × 49.5 cm

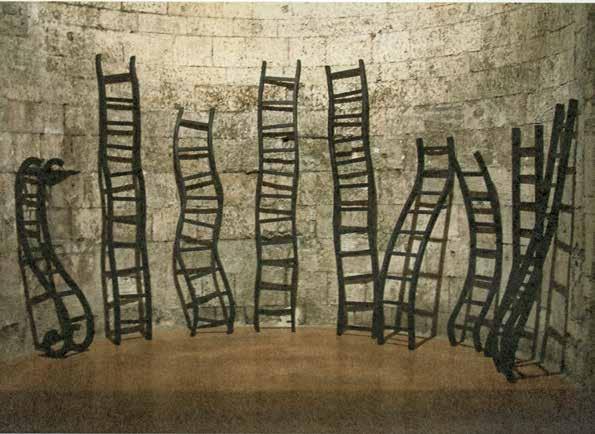

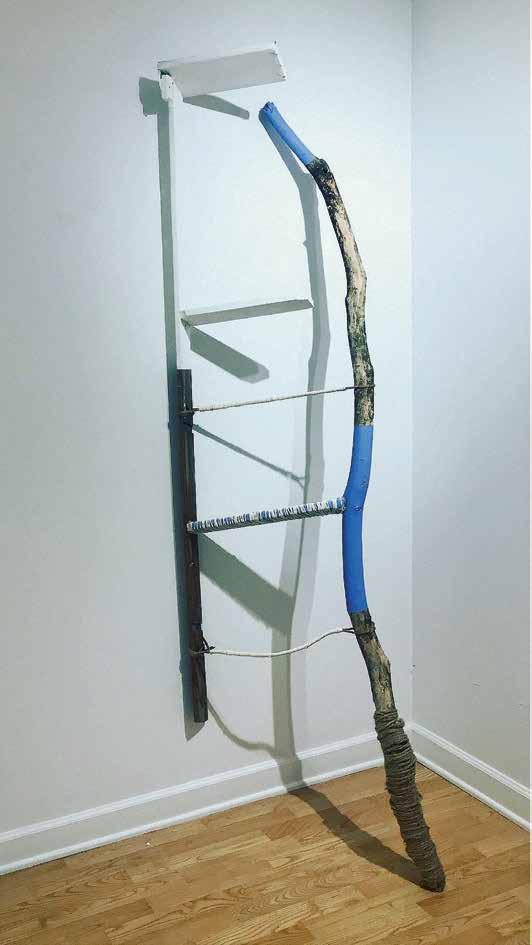

Walid Siti, Joined Ladder, 2016, twigs, acrylic, 280 × 100 × 100 cm

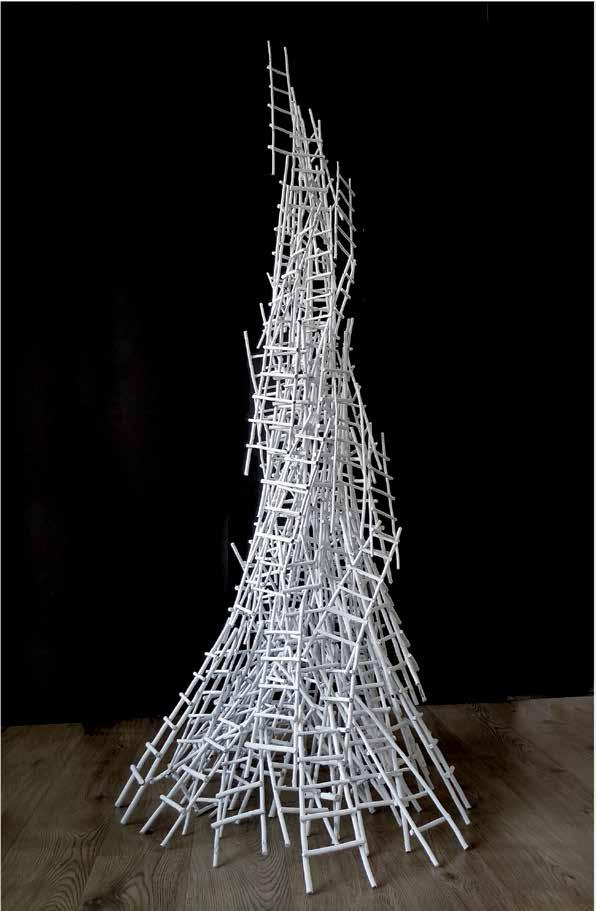

Francesco Carone, Totem, 2010, old wooden ladders, 410 × 120 × 120 cm

Charlie Brouwer, Rise Up Atlanta, 2011, ladders, heavy duty cable ties, and tags identifying lenders

Jo Coupe, Solid Air 2017, stepladders, colored nylon string, magnetic eld, rare earth magnets

Jo Coupe, Solid Air, 2017, stepladders, colored nylon string, magnetic field, rare earth magnets3

Yoko Ono, Skywatch Ladders, 2007, installation (wooden ladders various heights, white canvases with the word "Skyladder"), ladders: from 170 to 190 cm; canvases : each 34.5 × 24.5 cm

Peter Böhm, Lanxess Arena (Kölnarena), Cologne, Germany, 1995–1998

Peter Böhm, Lanxess Arena (Kölnarena), Cologne, Germany, 1995–1998

Do Ho Sun, Staircase-V, 2008, silk

Marco Tirelli, 2013

Jimmy Robert, Descendants of naked, 2016, installation detail (wood)

Hubert Kiecol, Bright сarrier, 2012, сoncrete, wood, 40.5 × 23 × 45 cm

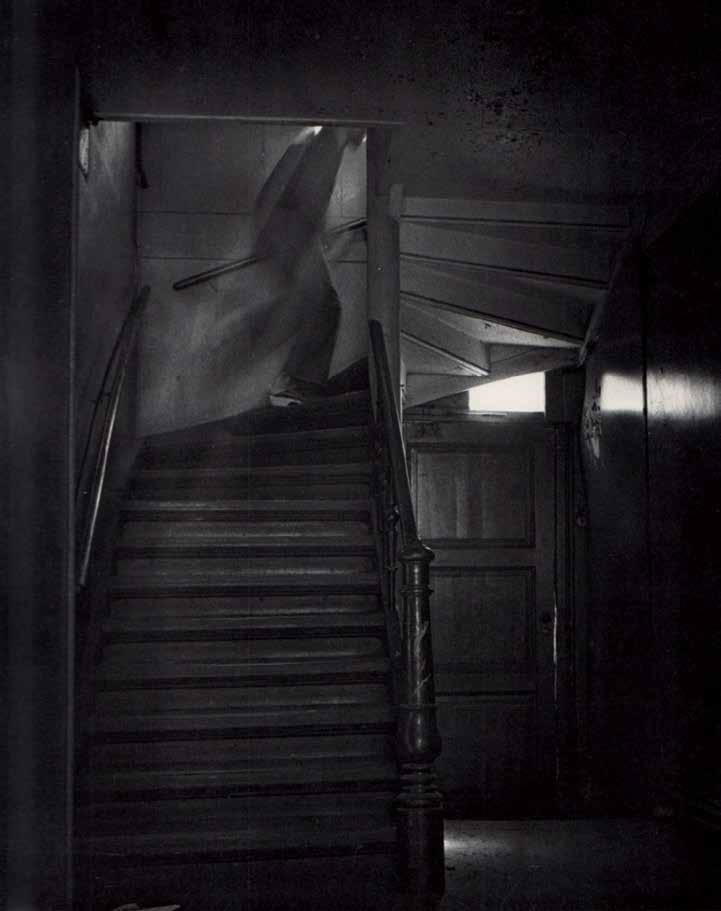

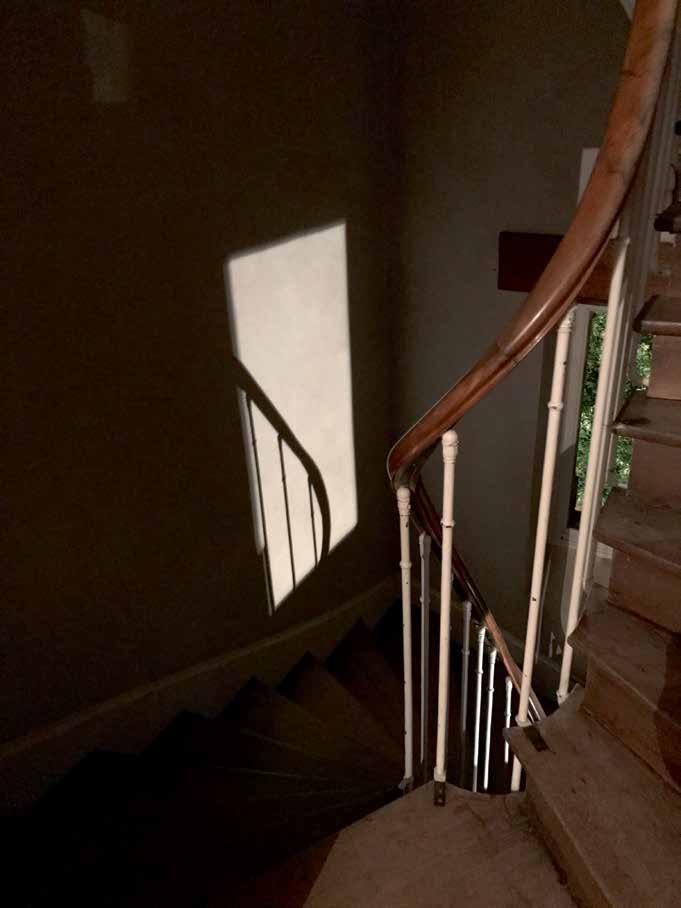

Charles Sheeler, Doylestown House — Stairs from Below 1917, photograph, 21 × 15 cm

Charles Sheeler, Doylestown House, Stairwell, 1914–1917, photograph, 24.2 × 16.8 cm

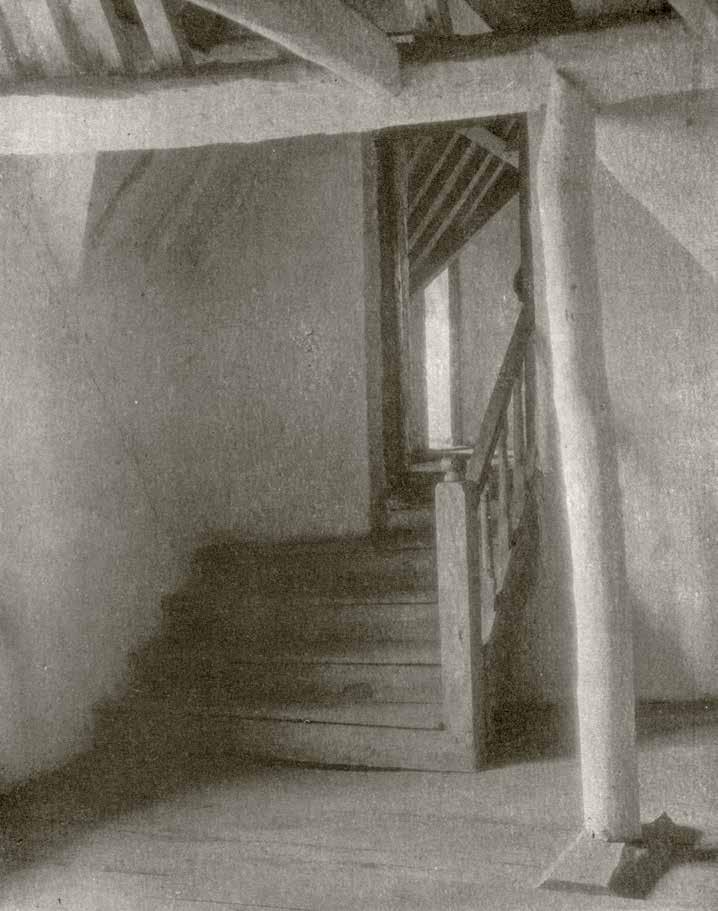

Frederick Henry Evans, Kelmscott Manor: in the Attics (2), 1896, platinum print, 19.9 × 14.9 cm

Theron Taylor, Denver, Colo, 1973, photograph

Xavier Mellery, Staircase, 1889, back and red chalk on paper, 57 × 45 cm

Charles Sheeler, Staircase, Doylestown, 1925, oil on canvas, 63.5 × 53.3 cm

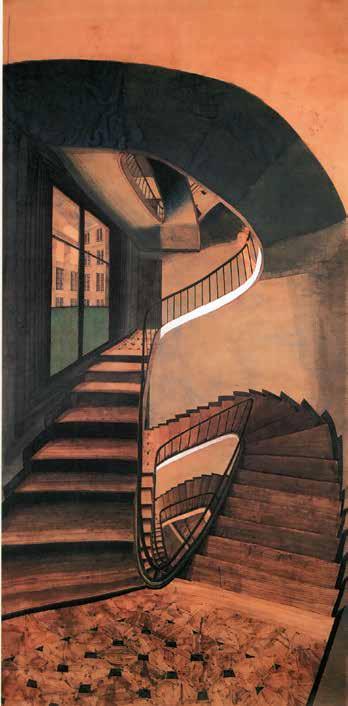

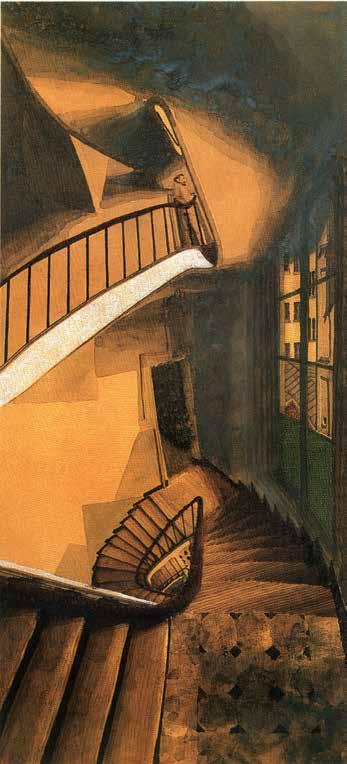

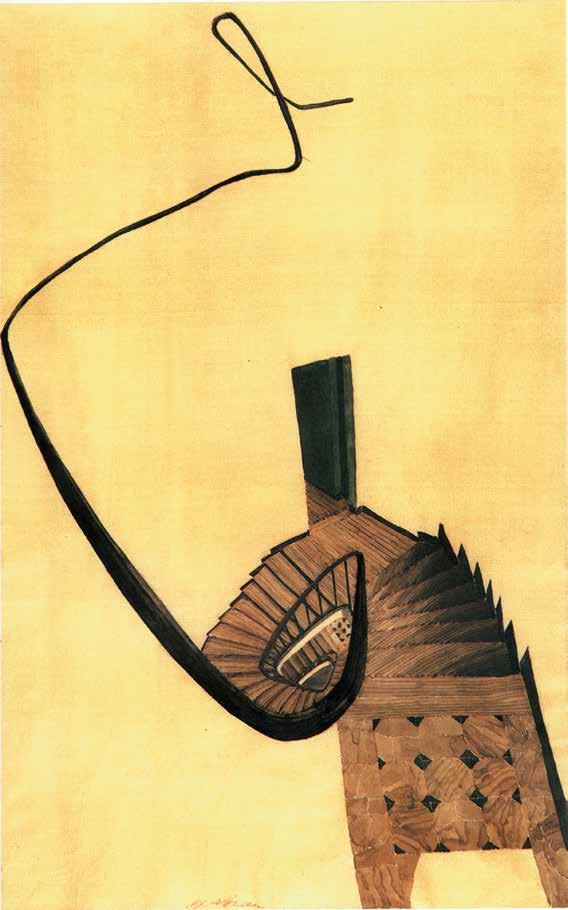

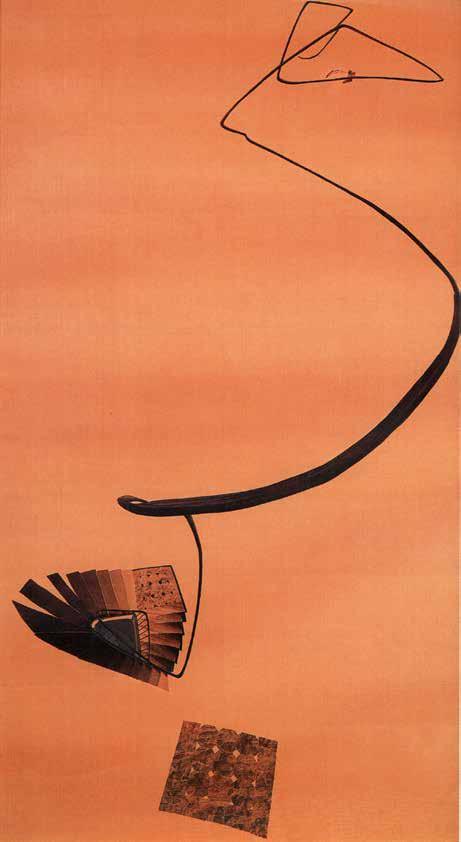

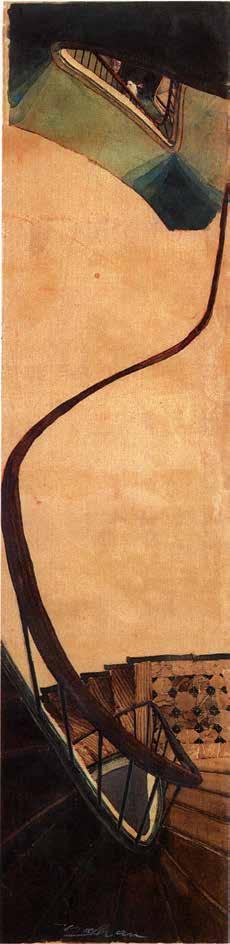

Sam Szafran, Staircase c. 1989, watercolor on silk

Sam Szafran, Untitled, 1990, watercolor on silk, 19 × 13.5 cm4

Sam Szafran, Staircase, 54 rue de Seine, c. 1992, watercolor on silk

Sam Szafran, 1990s

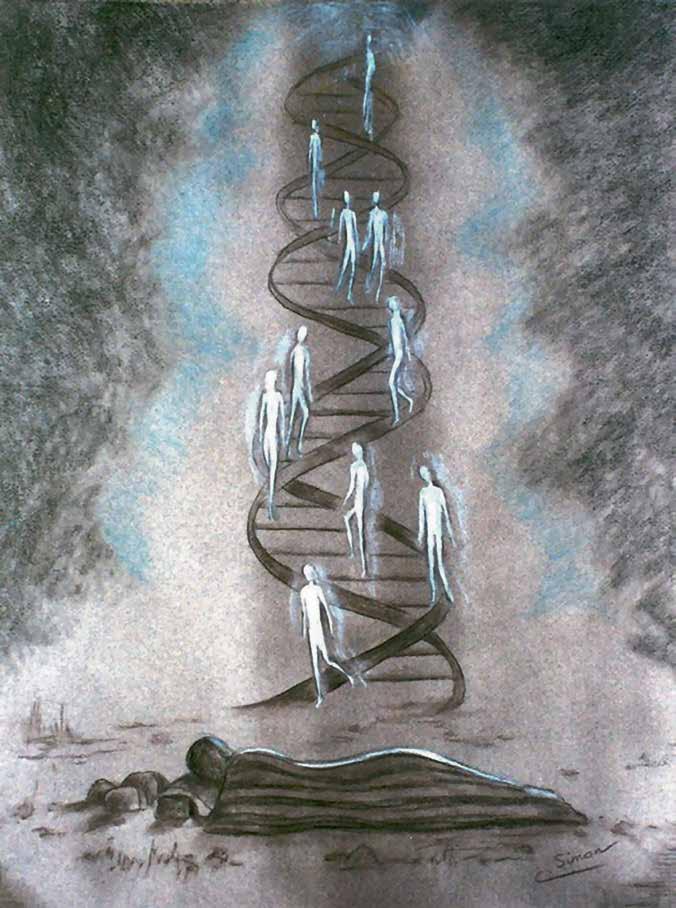

Katie Simon, Jacob’s Ladder, 2000s, pastel on paper, 50 × 40 cm

William Blake, Jacob’s Ladder, 1806, pencil and watercolor on paper, 39.8 × 30.6 cm

Devilliers the Elder, reproduction of Rembrandt’s Philosopher in Meditation, 1814, engraving

Andrea Palladio, Illustration for the book Four books about architecture, 15705

Hans Vredeman de Vries, illustration from book Perspective, 1604–1605, copper engraving on paper

Tom Kirsch, Staircase, Western State Hospital, Washington 2007, photograph

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, The Round Tower, from Imaginary Prisons, plate III, c. 1749–1750, etching, 63 × 49.5 cm

Filippo Juvarra, Scenography with stairs, end of the XVII, black ink on paper

Karl Blechen, Spiral staircase in Meiben, 1823, mixed media

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, View of a dungeon, from Imaginary Prisons, c. 1744–1745, pen in brown over black pencil, brown washed (feather in dark brown), 25.4 × 18.6 cm

Lourmarin castle stairs, XV century

Сastle stairs

Spiral staircase in the Old Royal Naval College Chapel, Maritime Greenwich, London, 1694

The Imperial Stairs — staircase between library and church, Melk Abbey, Austria, XVIII centuryвек

Cyril Edward Power, The Tube Staircase, 1929, color linocut on paper

Martine Rinder, Untitled, 1990s

Vincent Lamouroux, Heliscope 2007, steel construction, paint, 810 × 600 × 600 cm6

Architectural model, XIX century

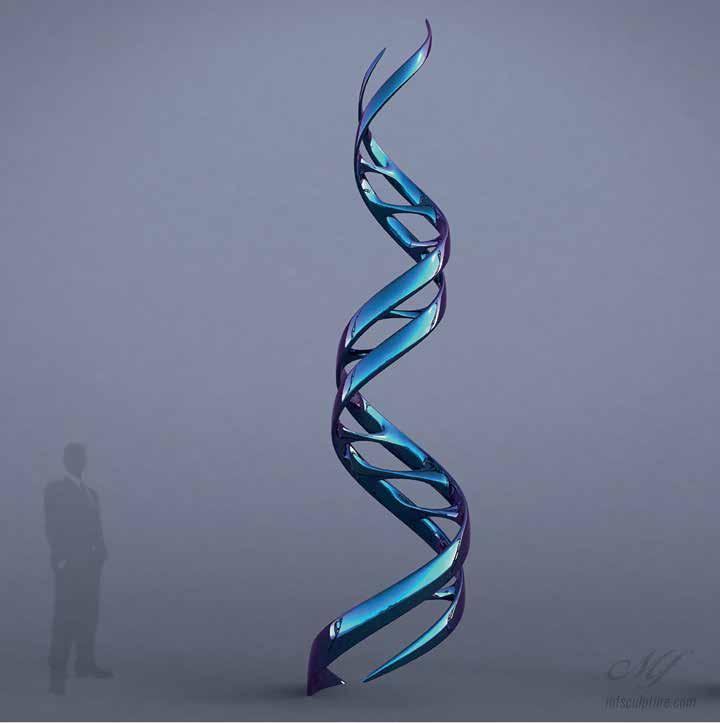

Mike Fields, Ribbon of life, stainless steel7

Benjamin Shine, Ascension — Twisted Ladder in Wood, 2015, wood

Olafur Eliasson, Rewriting, 2004

Hiroshi Nakamura, Ribbon Chapel, 2013

Isamu Noguchi, Slide Mantra, 1966–1985, marble, 69.2 × 61.6 × 70.5 cm

Isamu Noguchi, Slide Mantra, 1966–1985, marble, 49,8 × 56.2 × 60.3 cm

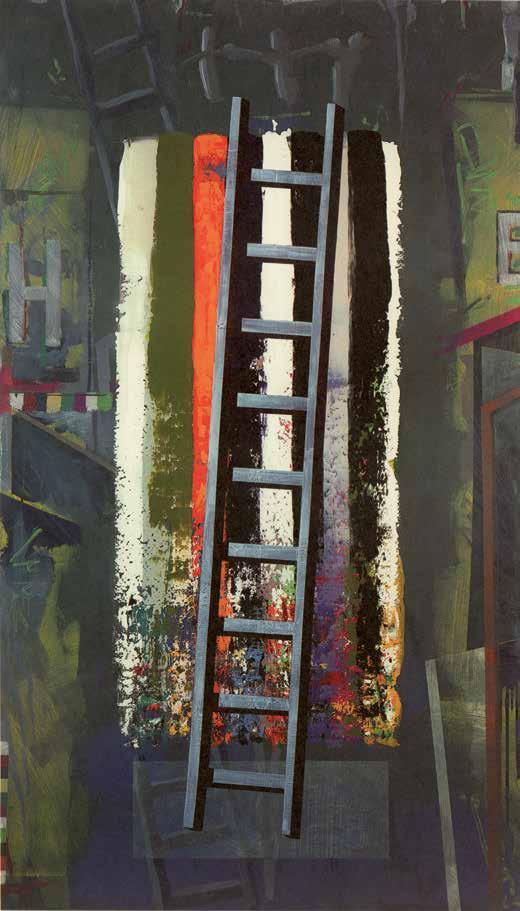

Tom Carr, The Ladder, 1980s

Robert Smithson, Spiral of Slate or Shale, 1970, graphite on board, 47 × 58.4 cm

< Oscar Tuazon, TBT, 2017, cement, brick, wood, 121.9 × 100.3 × 124.5 cm

Jene Highstein, Cedar Staircase, 1999, cedar, 487.7 × 104.1 cm

Marco Tirelli, Untitled, 2000s, plaster, wood, metal, 58 × 13 × 15 cm

Carmiel Van Breedam, Snow, 2005, 47 × 21.5 × 34.5 cm

Elizabeth Jaeger, Two owers and a Staircase, 2018, ceramics, 30.5 × 17.8 × 10.2 cm

Wolfgang Laib, Staircase 2003, lacquer on wood, 290 × 185 × 62 cm

Jackie Ferrara, Stacked Pyramid, 1972, cotton batting with glue on wood, 61 × 132.1 × 33 cm

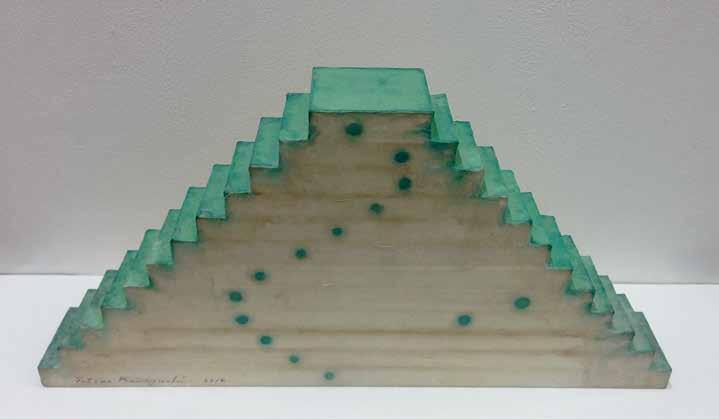

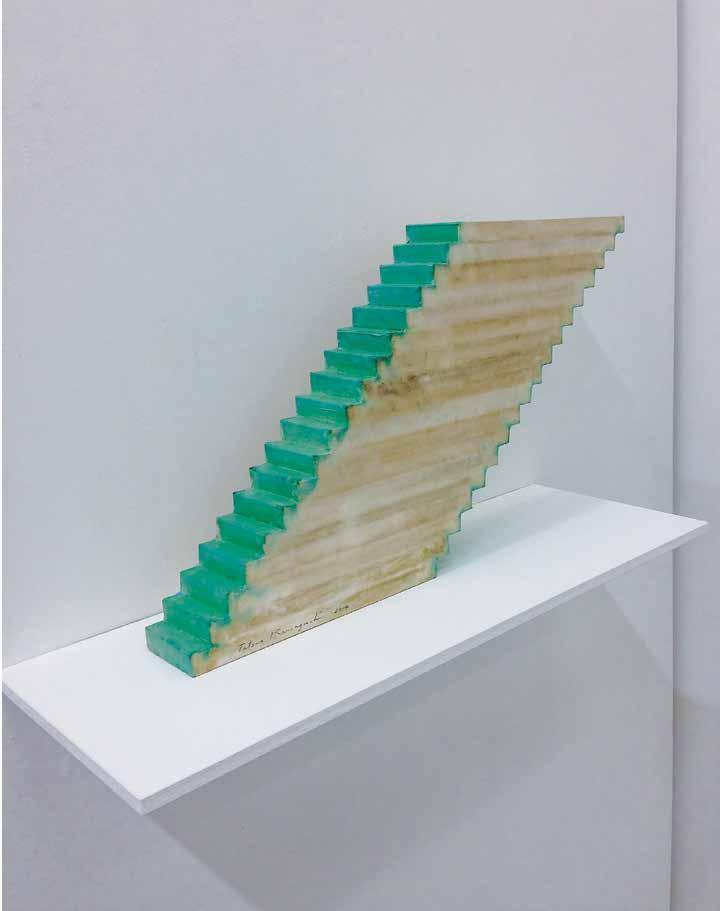

Tatsuo Kawaguchi, Relation — Optic Stairway Time, Verdigris and Upwards, Downwards, 2014, wood, paper, copper, varnish, 16 × 34 × 5.1 cm

Wolfgang Laib, Ziggurat, 2003, lacquer on wood, 238.8 × 317.5 × 66 cm

Isa Genzken, Untitled, 2017, concrete, 60.5 × 70 × 20 cm PYRAMIDIC

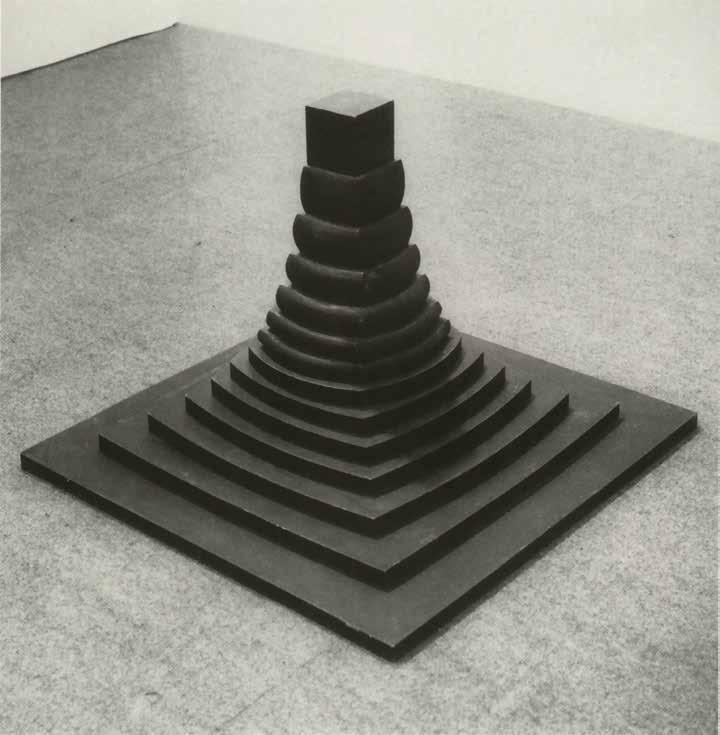

Vladimir Skoda, Untitled, 1984–1985, forged steel, 110 × 85 × 85 cm

Vladimir Skoda, Pyramid, 1987, forged steel, 80 × 80 × 100 cm

Vladimir Skoda, Untitled, 1984–1985, forged steel, 25 × 25 × 25 cm

Vladimir Skoda, Untitled, 1985, forged steel, 13 × 40 × 40 cm

Dani Karavan, Aliya (Ascent), 2014, Earth sculpture, 160 × 50 × 50 cm

Marco Tirelli, Untitled, 2013

Paul de Monchaux, Uxmal, 2008, bronze

David Umemoto, Cubic Geometry VI–II 2016, concrete, 15.2 × 15.2 × 15.2 cm

Marco Tirelli, Untitled, 2013, installation (plaster and wood)

Tatsuo Kawaguchi, Relation — Optic Stairway Time, 2014, styrene board, lotus seed, gesso, pencil, varnish, 20 × 22.5 × 16.5 cm

Inge Mahn, Balancing Towers, 1989, plaster on metal construction, 260 × 83 × 143 cm

Hubert Kiecol, Three houses with stairs, 1984, concrete, h. — 24 cm

Gao Weigang, Superstructure, 2010, stainless steel, titanium, 180 × 120 × 12.5 cm

Zarina, Ascent, 2014, paper printed with black ink and collaged with gold leaf paper, 46.4 × 43.2 cm

Michael Simpson, Squint 55, 2017, photograph

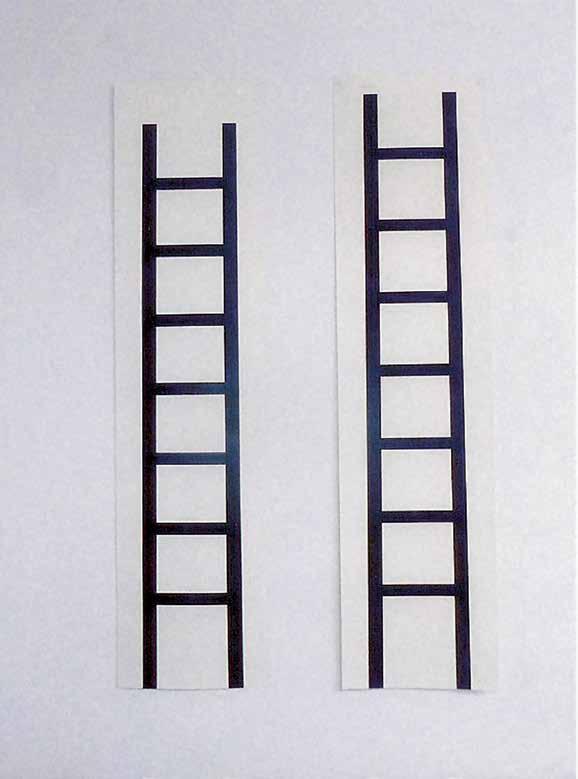

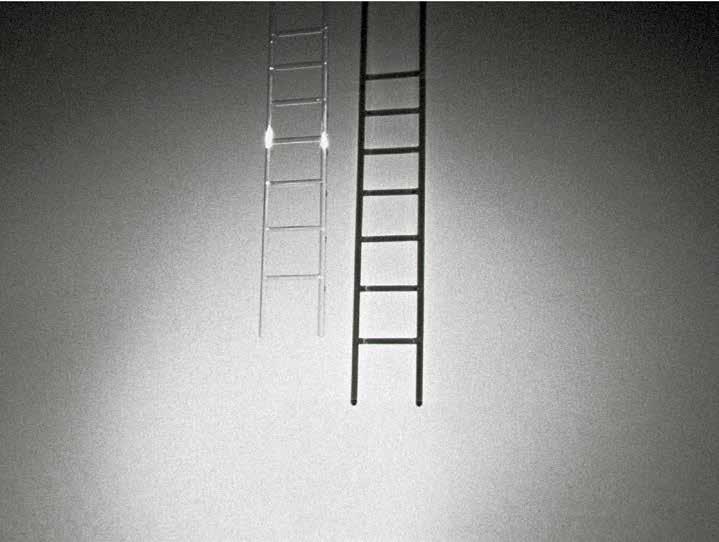

Hubert Kiecol, Two ladders, 1992, printing ink on cardboard, particle board, glass, 220 × 55 cm

Hubert Kiecol, The way up, 1994, oil on paper, 62 × 46 cm

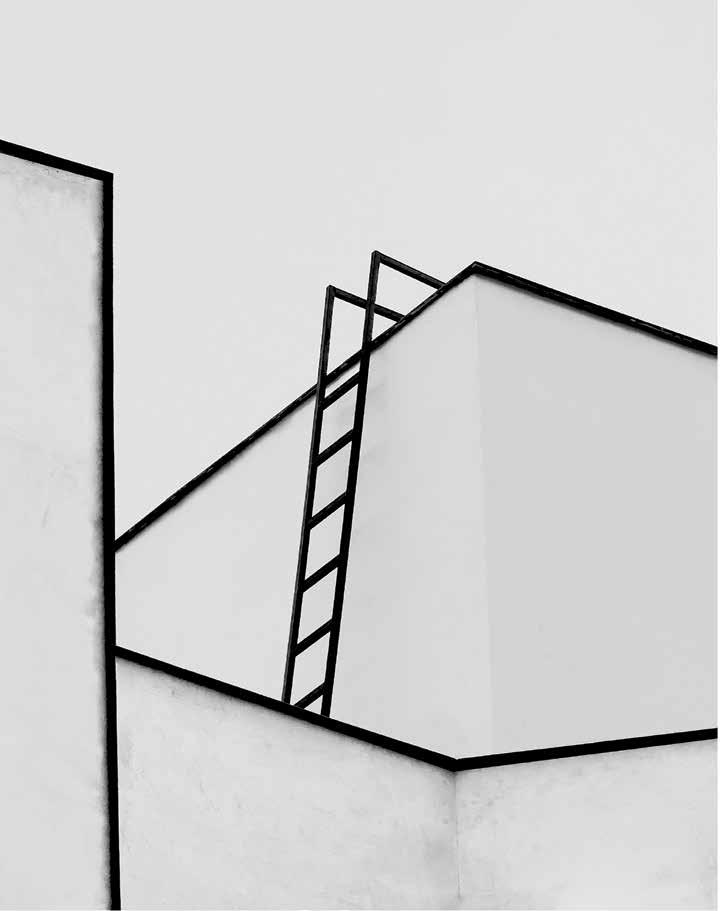

Yves Guillot, 2001, photograph

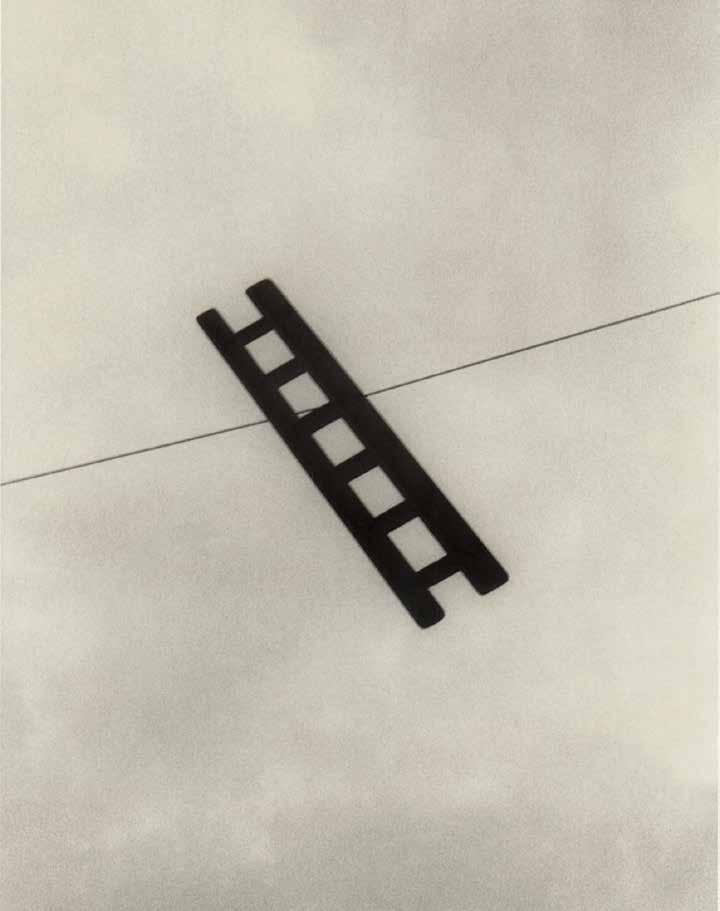

Javad Rooein, Ladder, 2016, photograph

Agusti Roque, Impossible, 1985

Hubert Kiecol, Untitled, 1980, concrete, 195 × 28 × 23 cm

Tatsuo Kawaguchi, Vertical Time, or Stairway Time, 2014, wood, paper, copper, varnish

Hubert Kiecol, Ladder, 1994, concrete, 14 × 14 × 11 cm

Concrete Steps and Railings

Yoko Ono, Ceiling Painting, Yes Painting 1966, text on paper, glass, metal frame, metal chain, magnifying glass, painted ladder, ladder: 183 × 49 × 21 cm, framed text: 64.8 × 56.4 cm

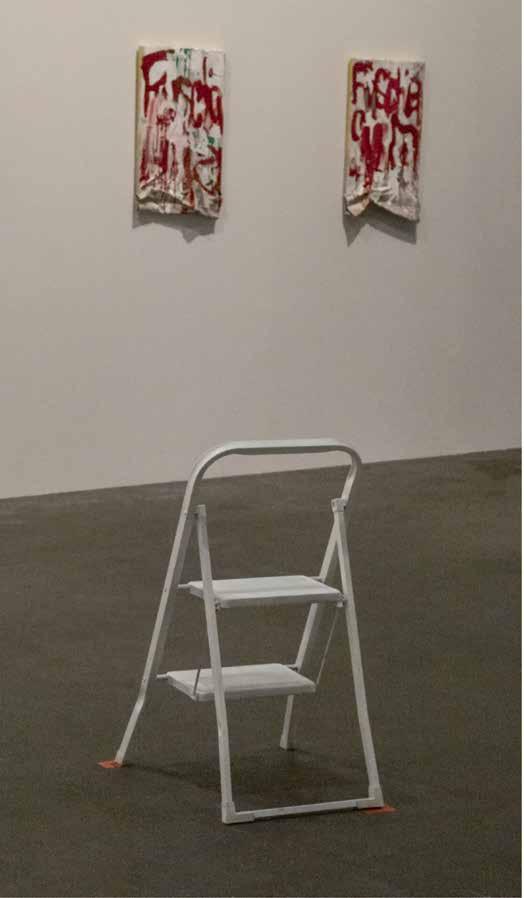

Pope L., Around, 2015, installation

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Wooden ladder, 1962–1983, silkscreen on stainless steel, 125 × 90 cm

Sylvie Fleury, Ladder, 2007, 23,5 carat gold layer, bronze, 196 cm

Gerwald Rockenschaub, Ladder Podium, 1993, aluminum, rubber wheels, 284 × 114 × 180 cm

Kirk Amaral Snow, When Transition Becomes Stasis, 2010, ladder, drywall, aluminum studs, adjustable clamps, joint compound and paint

Carmiel Van Breedam, Stair — stairs (Trap-trap), 2012, 47 × 21.5 × 34.5 cm

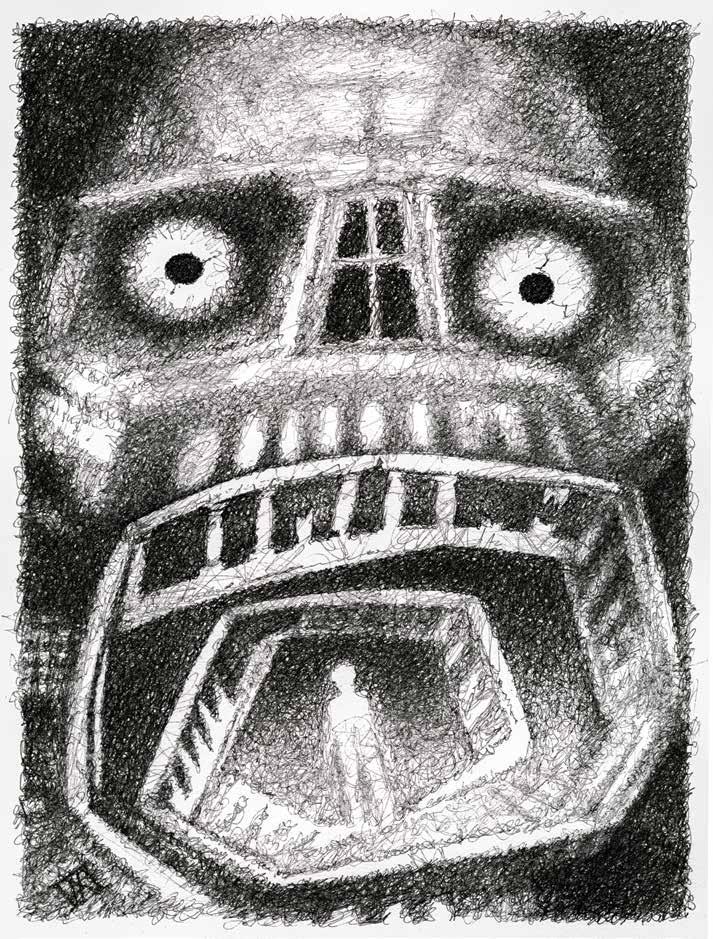

Robert Whitman, Dante Drawings 1974–1975, colored graphite, pastel, wax crayon and aluminum foil on paper

Zarina, Ascent, 2014, paper printed with black ink and collaged with gold leaf paper, 46.4 × 43.2 cm

Tatsuo Kawaguchi, Vertical Time, or Stairway Time, 2014, wood, paper, copper, varnish

Gordon Matta-Clark, Bingo, 1974, painted wood, metal, plaster, glass, 1.75 × 7.8 × 0.25 m

Sam Szafran, c. 1989–1995, watercolor, silk

Sam Szafran, Staircase, 1991, watercolor, silk, 28.5 × 10 cm

Sam Szafran, c. 1992–1995, watercolor

Sam Szafran, Staircase, c. 1992–1995, watercolor, 13 × 16.5 cm

Sam Szafran, c. 1992–1995, watercolor

Sam Szafran, c. 1989–1995, watercolor, silk

Sam Szafran, Staircase, 1991–1992, watercolor, silk

Sam Szafran, c. 1989–1995, watercolor, silk

Sam Szafran, c. 1989–1995, watercolor, silk

Sam Szafran, c. 1989–1995, watercolor, silk

Sam Szafran, c. 1989–1995, watercolor, silk, 50 × 31.5 cm

Sam Szafran, Untitled, 1997–1998, watercolor, ink, silk

Toblerusse, The Ones of '84 2010s, acrylic on canvas, 91.5 × 61 cm

Toblerusse, Apophenia 85:86 | 87:86, 2010s, acrylic on canvas, 101.6 × 76.2 cm

Toblerusse, Shark, 2010s, acrylic on canvas, 71.1 × 55.9 cm

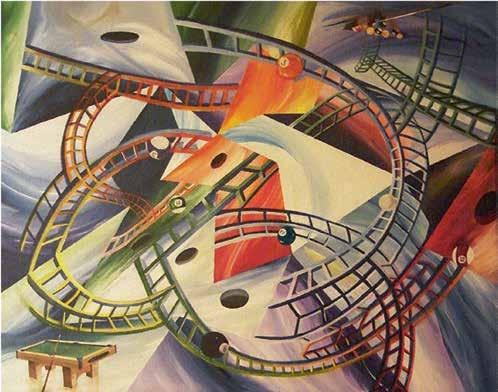

Toblerusse, Snakes and ladders, 2010s, acrylic on canvas, 61 × 61 cm

Toblerusse, Rollercoasterwater, 2010s, acrylic on canvas, 91.5 × 91.5 cm

Gregory Pototsky, Movie Director Luis Gasia Berlanga, 2009, bronze, 108 × 38 × 45 cm

Viktor Popovic, Untitled, 2008, iron, used motor oil, 92,5 × 150 × 175 cm

Steve Rossi, Reciprocal Ladder, 2012, wood and acrylic latex, 72 × 36 × 22 cm

Jacques Carelman, Vertical adhesive ladder, second half of the XX century, felt on paper, 25 × 15 cm

Alexis Blanc, Dream of 13.11.15, 2016–2018, steel, plywood, 180 × 307 cm

Alexis Blanc, Dream of 13.11.15, 2016–2018, steel, plywood, 180 × 307 cm

Daniel Dezeuze, Piece, 1972, slats of wood

Pablo Reinoso, Loop, 2016, carved wood and slate, 96 × 14.5 × 18 cm

Art Van Triest, Untitled 2010s, drawing

Alessio Albi, 2010s, photograph

Yunhee Min, Circular Ladder, 2018, ash, 134.6 × 134.6 × 43.1 cm

Ilan Averbuch, Steps, 2004, granite and steel, 233,6 × 294,6 × 91,4 cm

Art Van Triest, Mobius band, 2010s, drawing

Steve Rossi, Reciprocal Ladder to Roll, 2018, bronze, 15.2 × 21 × 20.3 cm

David Krynauw, Jeppestown play bench, 2016, wenge, 304.5 × 48 cm

Suzy Lelièvre, Stairs, 2006–2008, painted steel, rubber, 50 × 140 × 160 cm

Peter Co n, Untitled (Spiral Staircase) (detail), 2007, aluminum and steel, 670.6 × 670.6 × 213.4 cm

Peter Co n, Untitled (Rainbow), 2007, color photographs, d. — 4,3 m

Peter Coffin, Untitled (Spiral Staircase), 2007, aluminum and steel, 670.6 × 670.6 × 213.4 cm8

Monika Sosnowksa, Stairway, 2010, metal, PVC, 564 × 249 cm

Anonymous, Staircase from Blandecques tin factory, XIX century, walnut, 39.6 × 54.2 × 39.5 cm

Monika Sosnowksa, 2015

Monika Sosnowksa, exhibition at the Grand Palais, 2015, photograph by Mihail Chemiakin

Tamas Gaal, Body III, 1990, steel sheet, 72 × 150 × 90 cm

Jean-Luc Mouline, Mental Archaeology, 2010, metal

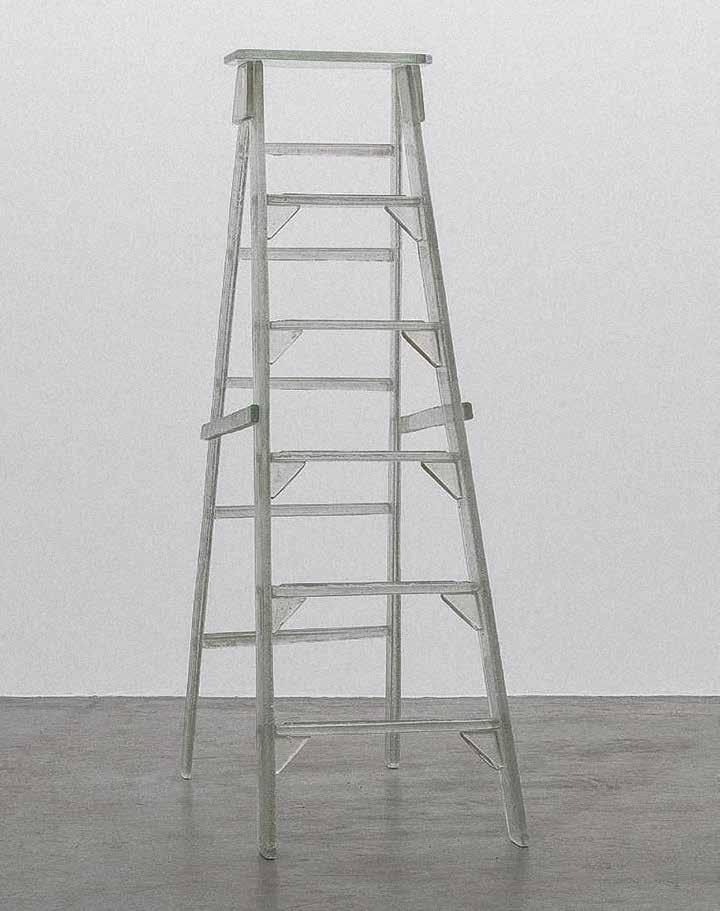

Scott Ball, Ladder rubber

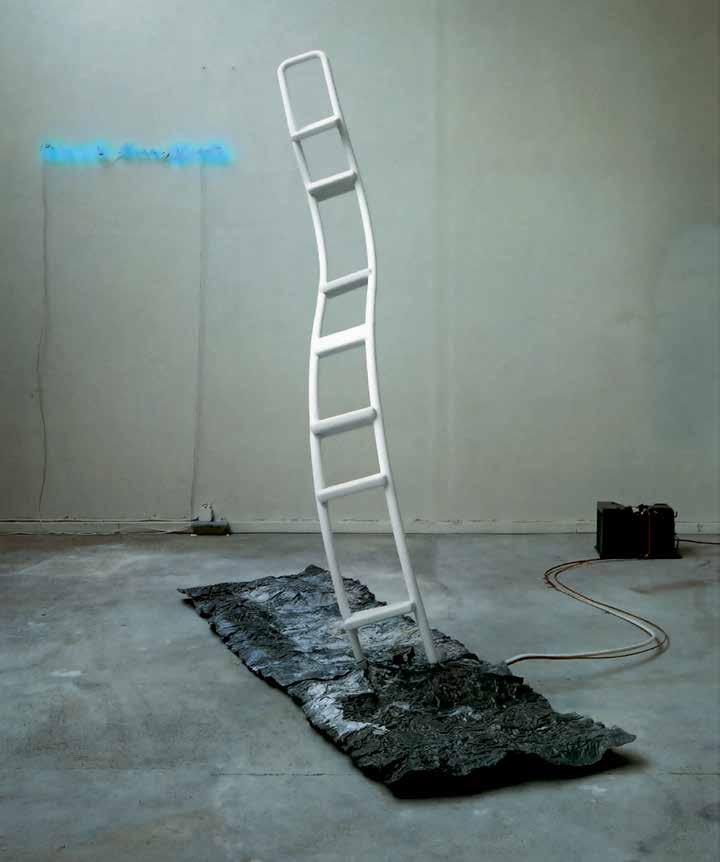

Loris Cecchini, Gaps (ladder), 2004, polyester resin, wall paint, 96 × 50 × 204 cm

Didier Fauguet, Indre, 2011, photograph by Mihail Chemiakin9

Richard Wentworth, 35°9,32°18, 1985, steel and aluminum, 413 × 113 × 127 сm

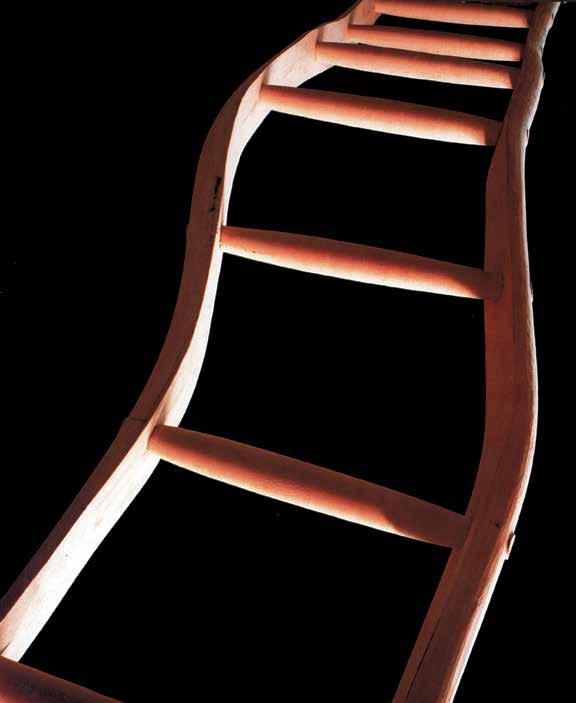

Martin Puryear, Ladder for Booker T. Washington, 1996, ash, 1112.52 cm

Martin Puryear, Ladder for Booker T. Washington (part of the installation), 1996, ash, 1112.52 cm

François-Xavier Chanioux, Blast, 2013, beech, gloss paint, 284.5 × 38 × 58.5 cm

François-Xavier Chanioux, Blast (detail), 2013, beech, gloss paint, 284.5 × 38 × 58.5 cm

Pier Paolo Calzolari, The air vibrates with the buzzing of insects, 1970, lead plates, copper ladder, motor, neon tube, 287 × 297 × 90 cm

Mihail Chemiakin, Ladder, 2019, fabric, 197 × 37 cm

Vanessa Billy, Flat Ladder II, 2015, aluminum

Piotr Klemensiewicz, Stairs Exhibition view in the chapel of Saint-Martin-du-Mejan, Arles, 2005

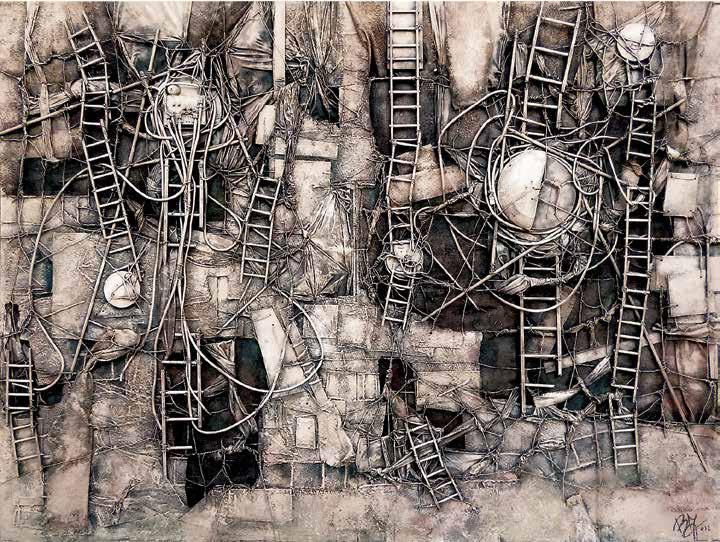

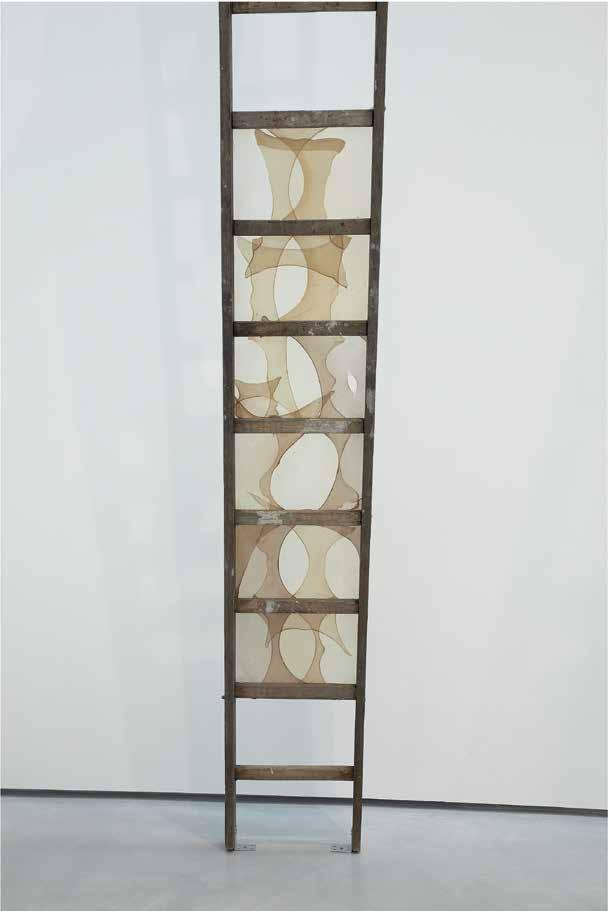

Hossein Valamanesh, Snakes and Ladders, 2007, crepe myrtle branches, gold leaf, 108 × 98 × 10 cm

Anselm Kiefer

Antoni Clave, maquette for the second act of Don Perlimplin staging, 1952, fabrics, woods, painted paper, 48 × 65 cm

Beppo Zuccheri, Scylla and Charybdis, 2012, mixed media on jute canvas, wood, iron, cement, rags, plastic, electric cables, acrylic, 150 × 200 cm

Monika Sosnowksa, 1:1 (detail), 2007, steel, 700 × 1400 × 600 cm

Art Van Triest, Ladder, 2010s, wood

Art Van Triest, Ladder, 2010s, wood

Art Van Triest, Ladder, 2010s, wood

Richard Tuttle, Ladder piece, 1967, dyed and cut canvas

Charlie Styrbjörn Nilsson, Ladders, 2014, wood

Clemens Auer, Ladder, 2009–2013, bentwood, lacquer

Bijoy Jain, Light Study, 2014, steel, electroluminescent wire, 55 × 32.5 × 150.5 cm

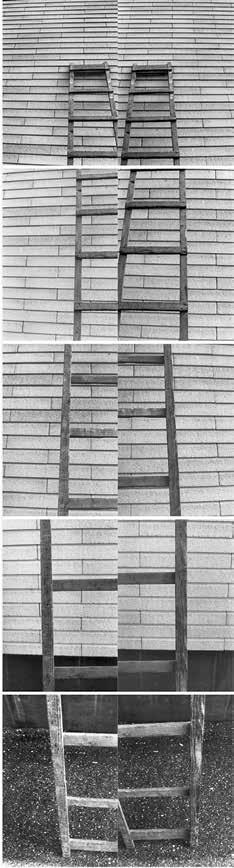

Leigh Warre, Ladder 2019, photograph

Leigh Warre, Ladder 2019, photograph

Kcho (Alexis Leyva Machado), The Worst of All Traps, 1990, wood, machete, di erent materials

Silvia Groebner, Jacob's Ladder, metal, 68 × 750 × 6 cm

Walter Pichler, Broken Ladder, 1969, plexiglass, aluminum, 248 × 50 cm

Art Van Triest, Ladder, 2010s, wood

Keith Bowler, Ladder Figure Large, 1987, wood, rope

Aniano Areco, Ladder from the Earth, 2013, wood, steel, acrylic paint, 250 × 45 × 7 cm

Valie Export, Ladder III, 1972, 10 black and white photos, 60 × 40 cm (each)

Nancy Fouts, Ladder, 2011, wooden ladder burnt and reformed with resin, 174 × 46 × 9 cm

Ceal Floyer, Taking a Line for a Walk 2008, line making machine and water-based marking paint on oor

Art Van Triest, Ladder, 2010s, drawing

Art Van Triest, Ladder, 2010s, drawing

Mateo Lopez, Ladder for Corner, 2015, oak LADDERS

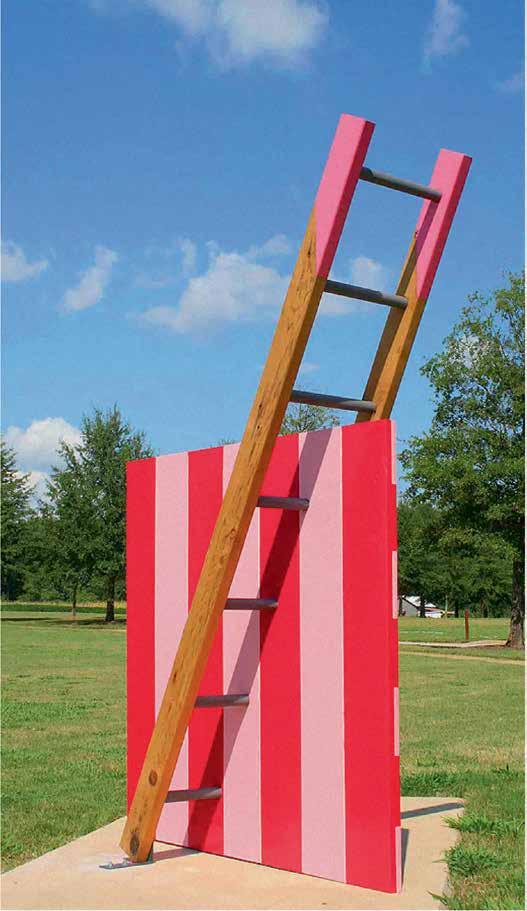

Brad Downey, The Ladder, 2012, aluminum, galvanized steel, plastic, hex-bolts, 252 × 46 × 10 cm

Art Van Triest, Ladder, 2010s, drawing

Ceal Floyer, Ladder (TBC), 2010, aluminum ladder, 278.5 × 37.5 cm

Maaria Wirkkala, As If TRA — Edge of becoming, 2008, glass ladder10

Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset, The Collectors, 2009, installation

Rob Good, Step II, 2010–2015, wooden stepladder, 120 × 100 × 50 cm LADDERS

Brent Fogt, Get Over It, 2017, found ladder, paint, gesso, wood, 66 × 76.2 × 213.4 cm

Tanguy Tolila, Ladder 3, 2016, wood and metal, 143 × 47 cm

Tanguy Tolila, Ladder 2, 2016, wood and metal, 134 × 46 cm

< Brent Fogt, Forward, 2018, found furniture, found ladder, jute, paint

Kaari Upson, MMDP (PUPILS), 2016, aluminum, stainless steel, 179 × 117 × 13 cm

Kaari Upson, MMDP (PUPILS) (detail), 2016, aluminum, stainless steel, 179 × 117 × 13 cm

Ladder cups, ceramics

Michael Snow, Of A Ladder, 1971, 10 black and white laminated photos, 34 × 50 cm (each)

Art Van Triest, Ladder, 2010s, metal, wood

Art Van Triest, Ladder, 2010s, metal, wood11

Werner Feiersinger, Untitled, 2013, 270 × 300.6 × 53.6 cm

Dmitri Obergfell, In nite Ladder, 2011, ladders, mirrors, 365.8 × 182.9 × 182.9 cm

Steve Rossi, Reciprocal Ladder to Intersect, 2017, cedar, acrylic latex, 72 × 54 × 16 cm

Mark di Suvero, Stairway to the Stars, 2008, steel, h. — 853.5 cm

Steve Rossi, Intersecting Descending Ladders, 2018, graphite on paper, 30.5 × 22.8 cm

Steve Rossi, Reciprocal Ladder for Four, 2014, wood, acrylic latex, 84 × 41 × 120 cm

Steve Rossi, Reciprocal Ladder for Three, 2014, wood, acrylic latex

Steve Rossi, Reciprocal Ladder for Three, 2014, wood, acrylic latex, 72 × 48 × 36 cm

Steve Rossi, Reciprocal Ladder for Four, 2018, bronze, 19.6 × 31.7 × 16.5 cm

Steve Rossi, Six Ladders, Two Flags, 2017, sequined fabric, wood, acrylic latex, 243.8 × 243.8 × 243.8 cm

Armando, The Ladder, 1992, oil on canvas, 70 × 50 cm

Johannes Tavenraat, Wooden ladder and a lying dog, 1839–1872, pencil on paper

Antoni Tapies, The Ladder, 1968, etching and aquatint, 154.9 × 118.1 cm

Clay Ketter, Sketch for Grey wall painting, 1995, gypsum wallboard, spackle, wood, steel edges, 110 × 110 cm

Armando, Ladder, 1993, bronze, 42 × 25 × 12 cm

Armando, Ladder, 1991, bronze

Armando, The Ladder, 1992, oil on canvas, 110 × 110 cm

Armando, Ladder, 1994, bronze, h. — 140 cm

Armando, Ladder, 1994, bronze, h. — 140 cm

Snakes and Ladders board game, England, 1920–1930s, paper, cardboard, 35 × 35 cm

Oxford Circus tube station Central line platform mosaic, based on the game Snakes and Ladders, photograph

Mihail Chemiakin, Pavement in Turin, 2019, photograph

Leigh Warre, Ladder, 2019, photograph

Mihail Chemiakin, Ladder on the Road, 2013, photograph

Leigh Warre, Ladder, 2019, photograph

Emi Ozawa, Tallest Ever, 2017, sculpture, 260.4 × 33 × 25.4 cm

Chema Madoz, Untitled, 1990, photograph, 106 × 103 cm

Mihail Chemiakin, 2017, photograph

John Signer Sargent, Staircase in Capri, 1878, oil on canvas, 80.01 × 44.45 cm

Gertrudes Altschul, Untitled, c. 1952, photograph, 38.3 × 29.2 cm

Mihail Chemiakin, 2017, photograph

Iwao Yamawaki, Stairs and Shadow 1933, photograph, 23.2 × 17.2 cm

Mihail Chemiakin, 2017, photograph

Mihail Chemiakin, 2018, photograph

ChrisMackey, Doorway, 1961, photograph

Chema Madoz, Untitled, 1990, photograph

Shikanosuke Yagaki, Sketch on the Street, 1930s, photograph, 29.2 × 22.5 cm

Tim Head, Elevation I and II, 1980, photographs, paper, 402 × 533 cm

Mel Bochner, Shadow, 1969, aluminum ladder, clamp-on light, tape

Hossein Valamanesh, Home of Mad Butter ies 1996, ladder, persian shoes, acrylic paint

Fabrice Samyn, Vanishing Point of View, 2012, wood

Svetlana Kopystiansky, The Story, 1989, oil, tempera, canvas, paper, tape recording, 330 × 600 x 300 cm

Michael Simpson, Leper Squint 16 2015, oil on canvas, panels, 381.8 × 736.7 cm

Sabine Marcelis, Brit van Nerven, Seeing glass tall iridescent, 2014, glass, mirror, colourfoil, 220 × 20 × 1.9 cm

Java Tarsis, Curves, Straight Lines 2011, photograph

Tim Head, Displacement 1975–1976, projectors, chairs, mirrors, bucket, clock, ladder, tape-measure, 487.7 × 891.5 × 891.5 cm

Andy Feltham, Boiler Room, 2016

Bunny Rogers, Ladder 13 (part of Brig and Ladder installation), 2017, wood and gel-based ink

Maaria Wirkkala, Beyond, 2013

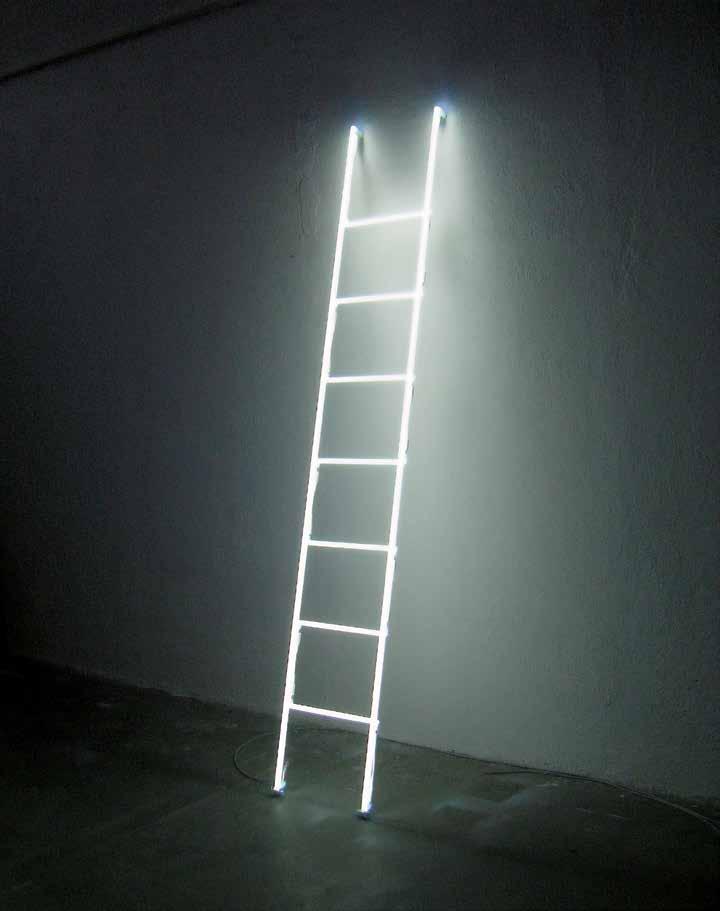

Stephen Dean, Single ladder 2007, aluminum, dichroic glass, 300 × 43 × 5 cm

Mihail Chemiakin, 2018, photograph

Piotr Klemensiewicz, Congestion — Terrace 1998, acrylic on canvas, 162 × 97 cm

Piotr Klemensiewicz, Congestion — Japanese Screen, 1999, acrylic on canvas, 195 × 114 cm

Piotr Klemensiewicz, Ladder — Congestion of Gray 2004, acrylic on canvas, 248 × 142 cm

Piotr Klemensiewicz, Congestion — January, 1998, acrylic on canvas, 203 × 82 cm

Piotr Klemensiewicz, Ladder — Congestion № 2, 2004, acrylic on canvas, 225 × 150 cm

Piotr Klemensiewicz, Ladder — Congestion № 4, 2004, acrylic on canvas, 225 × 150 cm

Steve Rossi, Reciprocal Ladder to Climb 2015, plywood and acrylic latex, 96 × 48 × 12 cm

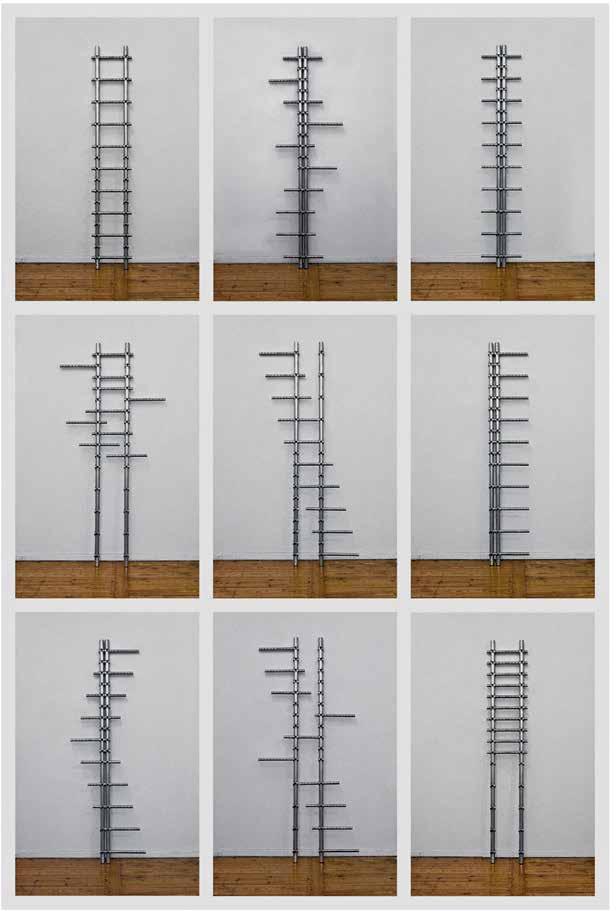

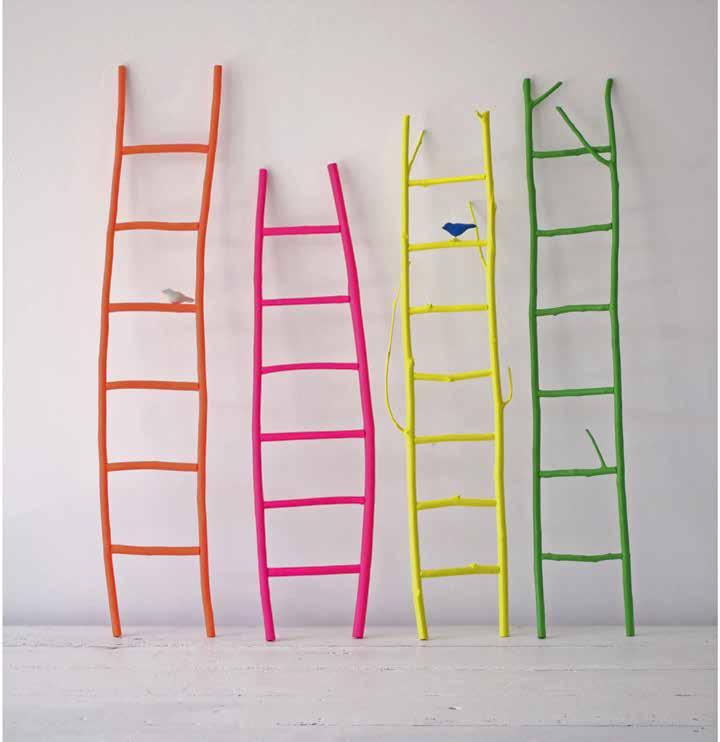

Ben Jones, Ladders series, 2010s, painted wood

Jim Lambie, Shaved Ice, 2012, wooden ladders, mirrors, household uorescent paint

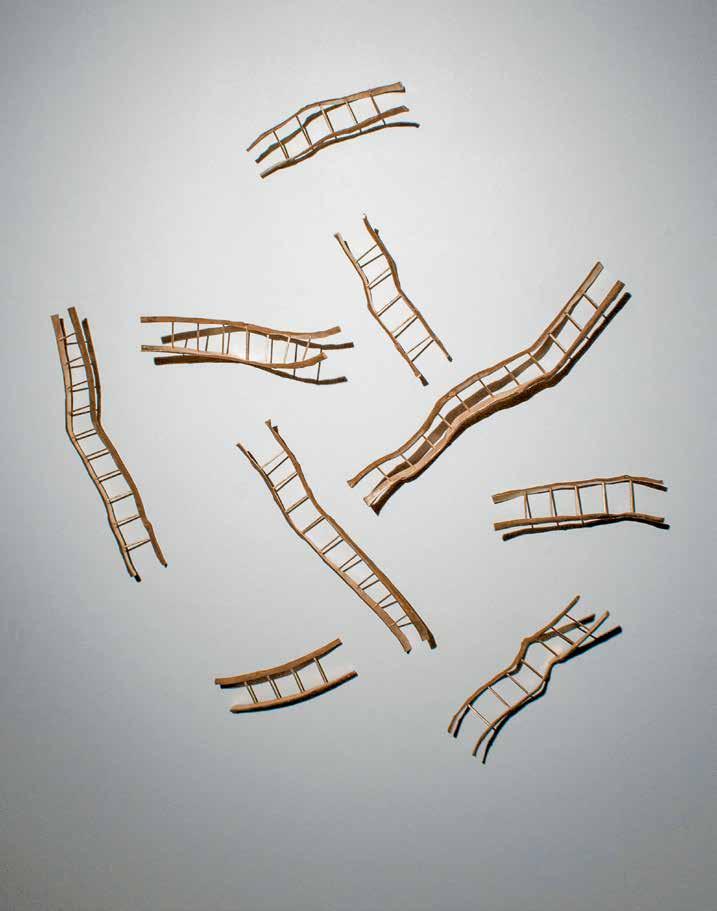

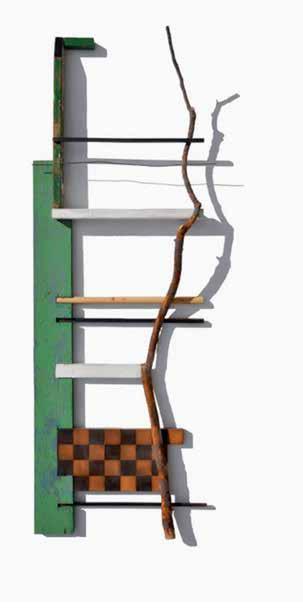

Anita Bell and Brian Bell, Twig ladders, natural twigs

Nancy OD Wilson, Green Ladder, ladder, stu ed fabric, 60.9 × 22.8 cm

Stephen Dean, 2000s

Stephen Dean, Ladder, 2018, dichroic glass and aluminum, 244 × 44 cm

Stephen Dean, 2000s, glass, metal

Nancy OD Wilson, I'll Build a Stairway to Paradise, ladder, stu ed fabric, 12.7 × 50.8 cm

Nancy OD Wilson, Narrow Climb, ladder, stu ed fabric, 116.8 × 12.7 cm

Ron Haselden, Ladder, 2018, pink ladder ascending to heaven atop St. Martin's in The Fields Church

Massimo Uberti, Untitled, 2014, neon, iron, transformer, 200 × 40 cm

Viktor Popovic, Untitled, 2012, uorescent light tubes, steel ropes, electrical ttings, 350 × 50 × 93 cm

Carmela Gross, Ladders, 2012, industrial ladders and white uorescent lamps

Michael Joo, Simultaneity Biases, 2018, installation

Maaria Wirkkala, TRA — Edge of becoming, As If project (detail), 2008, glass ladder

Gao Weigang, Where 2, 2015, stainless steel, gold, 216 × 53 × 7 cm

Gao Weigang, Where 2015, stainless steel, gold

Alexandra Bircken, De ated bodies (detail), 2014, installation

Nancy OD Wilson, Ascendant, 1980–2000s, crochet and wooden ladder, 193 × 31 × 5 cm

Gao Weigang, Yes, 2013, stainless steel, 236 × 300 × 75 cm

Gao Weigang, Yes, 2016, stainless steel, gold, 240 × 75 × 20 cm

Mateo Lopez, Stairs, 2013, stairs, lacquered metal ladder

Gao Weigang, Yes, 2016, stainless steel, titanium, iron, 380 × 300 × 270 cm

Guillaume Saalburg, design of the private apartment, ladder, 1997, wood, glass

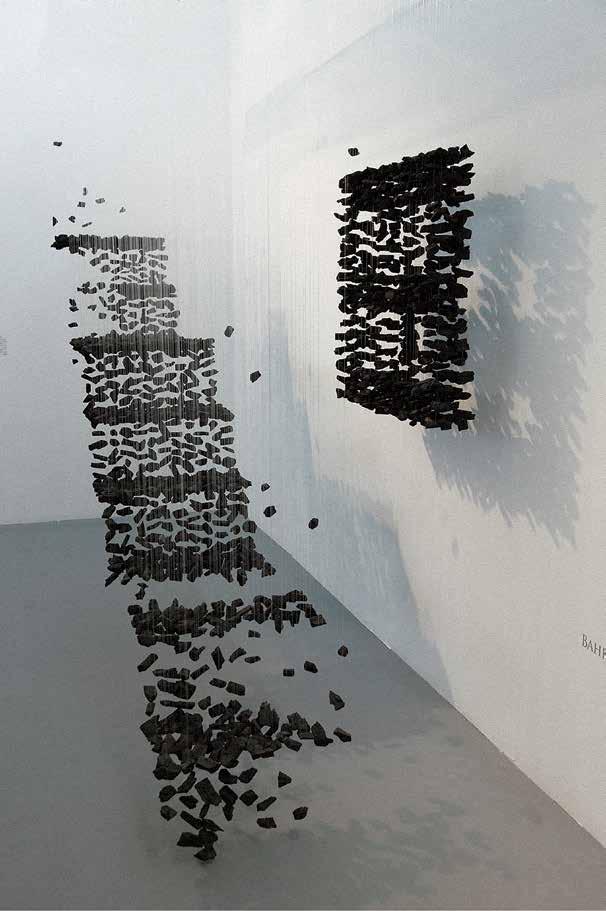

Seon-Ghi Bahk, Panorama (detail), 2007, charcoal, nylon threads, stone, h. — 300 cm

Louisa Chase, Brook, 1980, oil on canvas, 91.5 × 182.8 cm

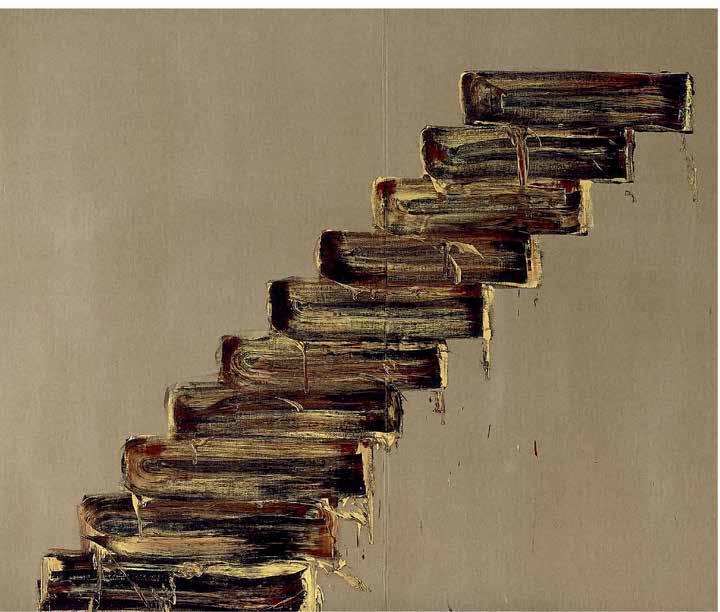

Basil Beattie, RA, Never Before, 2001, oil and wax on ax

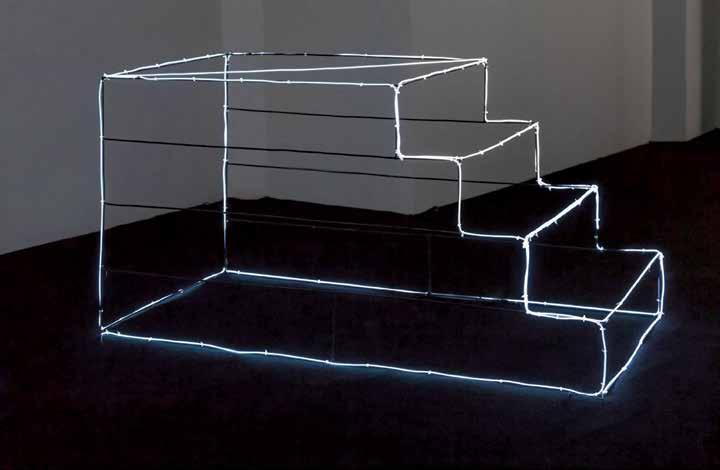

Bijoy Jain, Light Study, 2014, steel, electroluminescent wire, 123 × 62 × 62.5 cm

Monika Sosnowksa, Untitled, 2012, steel and lacquer, 75 × 67 × 39 cm

Nikolai Makarov, Untitled, 1988, acrylic on wood, 200 × 140 cm

Nikolai Makarov, Untitled, 2010, acrylic on wood, 180 × 130 cm

Urs Fischer, Chagall, 2006, polyurethane foam, nails, spray enamel, acrylic paint, expanding polyurethane foam, ller, polyurethane glue, electric motor, aluminum, control unit, battery, cables, 229 × 77 × 142.3 cm

Urs Fischer, Chagall, 2006, polyurethane foam, nails, spray enamel, acrylic paint, expanding polyurethane foam, ller, polyurethane glue, electric motor, aluminum, control unit, battery, cables, 229 × 77 × 142.3 cm

Ei’ichi Matsumoto, Shadow of Solidier and Ladder on a Wooden Wall (Nagasaki — 4,400 m from the hypocenter), 1945, photograph

Mihail Chemiakin, 2006, photograph

Walid Siti, Stairways 2013, acrylic on paper, 73 × 108 cm

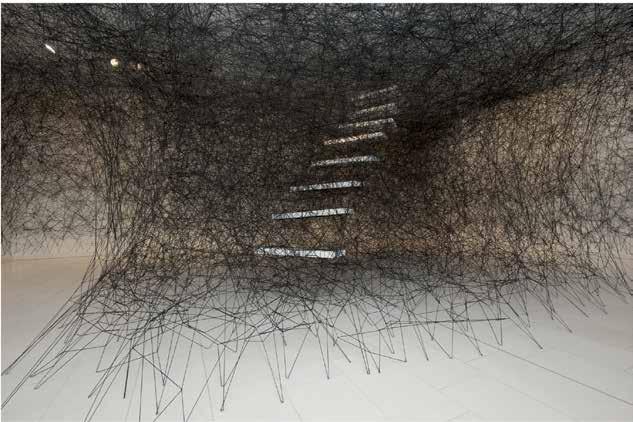

Chiharu Shiota, Stairway, 2012, blocks, blackwool

Nikolay Tikhomirov, Snow in March, 2010s, photograph

Marie Lund, Settings, 2012, silk fabric, aluminium frame, found objects

Loris Cecchini, Gaps (ladder), 2004, polyester resin, wall paint, 96 × 50 × 204 cm

<

Anonymous, after Aegidius Sadeler, Ladder to heaven / Ostrich feathers, from series Symbola Divina et Humana Ponti cum Imperatorum Regum 1666, engraving, 11.7 × 6.4 cm

Antoni Tàpies, The Ladder, 1974

Rob Good, Far away 2016, stone and oak, 70 × 46 × 30 cm

Rob Good, Far away, 2016, stone and oak, 70 × 46 × 30 cm

Rob Good, Once Upon, 2016, marble and oak, 65 × 25 × 40 cm

Gertrude Abercrombie, Two Ladders, 1947, oil on massonite, 30.5 × 40.6 cm

Leah Cross, Driftwood Ladder, 30.5 × 30.5 cm

Anselm Kiefer, Seraphim, 1983–1984, emulsion, gummillak, synthetic resin on canvas, 330 × 340 cm

Anselm Kiefer, At the beginning, 2008, oil, emulsion, lead and photo paper on canvas

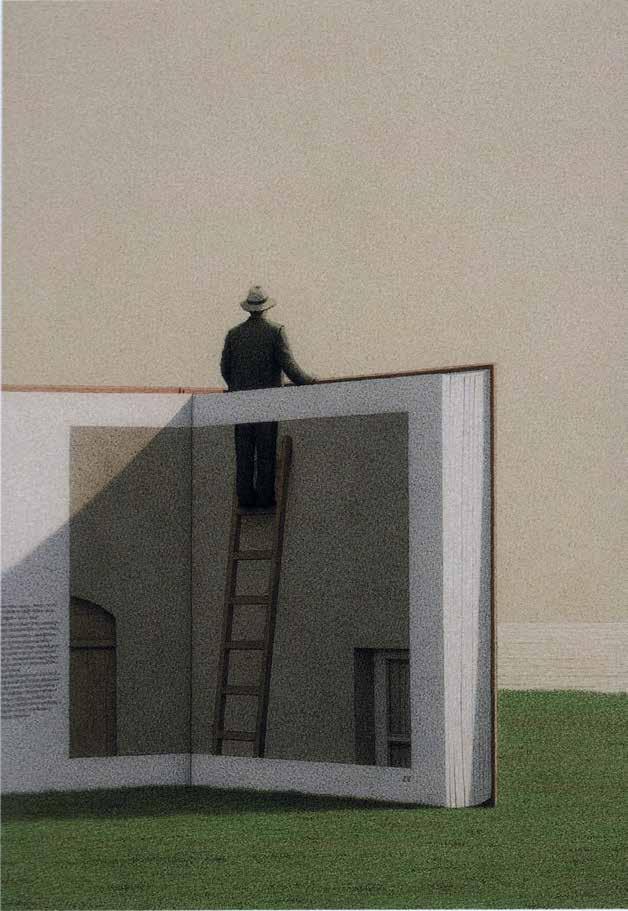

Quint Buchholz, Man on ladder, 1992

Stephen She eld, Ladder 33, 1980s, photograph, 45 × 61 cm

Jean Michel Folon, In space — Equilibrium, 1999–2000, resin and painted iron, controller, electrical system and audio, h. — 245 cm

Steve Rossi, Descending Ladders, 2018, graphite on paper, 30.5 × 22.9 cm

Maaria Wirkkala, A void me (part of the installation), 2001, glass ladder

Georgia O’Kee e, Ladder to the Moon, 1958, oil on canvas, 102.1 × 76.8 × 3.5 cm

David Austen, Cold, 1989, oil on canvas, 40.6 × 35.6 cm

Cai GuoQiang, Sky Ladder, 2015, h. — 500 m

Eugene Terwindt, The sky is the limit, 1997, aluminum, 26 × 1.2 × 0.6 m

Exhibition view “Steps, Ladders, Stairs in Art” , Mihail Chemiakin Centre St. Petersburg, 2019

(photograph by Ruslan Iskhakov)

1 (с. 49). Magdalena Jetelova, Stairs 1982–1983, wood, metal

The stairs of Magadalena Zhetelova — as a solution to the problem that other contemporary sculptors faced — are so fresh, so original and materially relevant that the question of the content and meaning of this sculpture is gradually disappearing. But what is for sure: the steps lead up, and not further, the path ends in non-existence. Stairs: steps that lead to nowhere.

2 (с. 50). Martina Casey, Escher inspired scenography 2017, paper, cardboard, scotch tape, sponge, brushes, scissors MARTINA CASEY: This is scenography in a model of a theater in scale. After seeing the theater representation of Amlet at the LAC, I came up with this idea of a concept of a simple scenography that bridged up the real important thing on the scene, the difference points of view, actor, audience, me and them. I took inspiration from the painting “relativity” from Escher. took the importance of the stairs in my scenography because they are a way of changing things, a medium to get somewhere else.

3 (с. 66). Jo Coupe, Solid Air , 2017, stepladders, coloured nylon string, magnetic field, rare earth magnets

Solid Air is a large-scale installation made from ladders, string and magnets. Activating the space between the gallery wall and ordinary domestic objects, Coupe engages our childlike fascination with magnetism. Anchored to a configuration of stepladders, metal discs tied to the opposite end of the string are pulled magically toward the wall of the gallery, causing them to float weightlessly in attraction. The architectural qualities of the stepladders are enhanced by the linear qualities of the taut string, which combine to map a complex and colourfully trembling matrix between a powerfully charged field beyond the wall, and the commonplace and functional resting on the floor.

4 (с. 80). Sam Szafran, Untitled 1990, watercolor, silk The very device of the ladder is designed to climb: it carries the burden of guilt or the hope of forgiveness. This is death or salvation, burial or flight, it causes rapture or disgust. Some companies will even say that dreaming of climbing the stairs is dreaming of strong power or, conversely, descending it: a nightmare of fading. A series of stairs will put an end to this dizzy theme. At the same time, this is the reason for the descent, which will renew and strengthen the falagella, the whip, the great imperative sign that scratches the page with the determination of Chinese calligraphy.

5 (с. 86). Andrea Palladio, Illustrations for the book “Four books about architecture” , 1570

Right Staircase designs from Book I of Palladio's Quattro libri, taken from the second, 1721 edition of Leoni's The Architecture of A. Palladio of 1715. As Eileen Harris has observed, “This lavish edition of Palladio's works... proved far too fanciful for the didactic perfection demanded by Burlington”. Campbell died after publishing only the first book of a new, more pedantically precise edition in 1728, and it was not until 1737 that an edition of Palladio appeared on which the Palladians could rely.

6 (с. 101). Vincent Lamouroux, Heliscope , 2007, steel construction, paint

Particularly interested in the relationship between sculpture and architecture, the utopias of modernism and their interpretation, Vincent Lamourou has devoted himself over the past ten years to creating objects, installations and settings, operating “machines” that set the viewer in motion. In the architectural context of Ivry, Vincent Lamourou's proposal is a form of reflection for all outdoor terraces designed by the architect Jean Reno (between 1970 and 1975). An exceptionally vertical, rare formula in Lamourou's advanced corpus, Heliscope / Perspective inclined (2007) is another feasible structure. It is a helicoidal staircase more than eight meters long, inclined at 10 degrees, the only work of the same name exhibition in the Chapel of Joan of Arc in Thouares. The user loses their balance under the influence of attraction. Concerned about his point of view, he struggles to find his bearings. A follower of hybrid and anachronistic formulas, which he himself calls the “retro future”, Vincent Lamourou, along with other artists of his generation, participates in the modern presentation of utopian, architectural and cinematic projections aimed at recreating a vision of the future as it could exist, but without nostalgia pointing out that this future is already worn out. Claire Le Resty.

7 (с. 103). Mike Fields, Ribbon of life , stainless steel “Ribbon of Life” is a modern representation of the DNA Double Helix which is at the basis of life. The Ribbon is extremely complex, with near infinite potential, yet is elegant in its design. The coupling of DNA marks a significant creative act. DNA is generative and therefore its ordered and infinitely diverse expression emerges through its cosmic relation.

8 (с. 182). Peter Coffin, Untitled (Spiral Staircase) , 2007, aluminum and steel

Peter Co n's recent exhibition looks like an allegory of iconism, in other words, the connection between sign and meaning, or an allegory of the creation of a sign. In other words, an image may make an impression because it is impressive, but it is at least as likely to be recorded for any other, less ennobled reason. And on the other hand, there is the artist’s latest stab at actually producing an icon. I refer to the in nitely looping, circular spiral staircase of grey-painted metal, nearly eight meters in height and leaned casually against the gallery wall. This is a piece which, if it rises to the cultural height of iconic status, would be the newest in a bevy of Co n’s works to produce astronomical reproduction statistics in the art-circulation machine. Like many of those works before it, the staircase is based on a simple idea, which Co n manifested without the sort of introspection that leads an artist to ask, “is this work invested with meaning? Does it re ect an original view of the world?”. What he asks of the piece is more accurately put as, does in the minds of those viewers themselves. Does it all mean that Co n has become suspicious of the nature of the iconic artwork as such, or rather of the nature of the artist who would make an icon of his or her genius? I would like to say so, but if I read criticality into Co n’s work, I must acknowledge that this is value I myself have generated, for to assume that the work itself is inherently critical is to fall prey to the mistake that this

art would lead us away from, in that criticism marks the return of the artist’s voice and the work’s speci c meaning. Co n’s art must be recognized as less rhetorical than that, more dumb and so more profound; I elsewhere wrote that it is more akin to a question than to a statement, but I see now that this art is closer still to the experience of having a question itself, a thing from no life but one’s own.

Abraham Orden

9 (с. 193). Didier Fauguet, Indre 2011

The work of the sculptor Didier Foge. Monsieur Baudouin, a member of the Endre Public Union, takes part in the creation of the metal part. Sculpture donated to Endra's TELETHON on the occasion of her 25 th birthday. Opened December 3, 2011.

10 (с. 226). Maaria Wirkkala, As If TRA — Edge of becoming 2008, glass ladder

Illusoire — as if. Alteration of moving image and daylight at the interface of exterior and the interior. During the day the landscape comes inside. At night, the work runs outside.

11 (с. 238). Art Van Triest, Ladder 2010s, metal, wood Visual artist Art van Triest confronts the viewer with a powerful visual language. With skilled craftsmanship and quirky humour, the artist transforms these into thought-provoking sculptures and installations. With his works, Van Triest unites a raw industrial style with a poetic manner of questioning social issues: the universal human tendency to strive for control and security in order to subdue our anxieties.

Previously published books in the “Mihail Chemiakin’s Museum of the Imagination” series