AfullPTFEsmooth-borehose,manufacturedusingapatentedprocessthatcreatesconvolutionsonlyontheoutsideofthetubewall,wherethey belongforincreasedflexibility,notontheinsidewheretheycanimpedeflow.Thissmooth-boreracehoseandcrimp-onhoseendsystemissized tocompetedirectlywithconvolutedhoseonbothinsidediameterandweightwhileallowingforatighterbendradiusandgreater flowpersize. Tensizesfrom-4PLUSthrough-20.Additional"PLUS"sizesallowforevenlargerinsidehosediametersasanoption.

NEWXRPRACECRIMPHOSEENDS

Blackis“in”and itisourstandardcolor; BlueandSuperNickelareoptions.Hundredsofstylesareavailable. Benttubefixed,doubleO-RingsealedswivelsandORBends. Reducersandexpandersinboth37JICandClamshellQuickDisconnects. Yourchoiceoffullhexorlightweightturneddownswivelnuts.

ANTI-STATICPTFE COMPATIBLEWITHALL AUTOMOTIVEFLUIDSANDFUELS

Ahighlycompressed,non-porousmatrix thatisresistanttofuelpermeationanddiffusion.

SMOOTHINTERNALTUBE

Forsuperiorflowrates,minimum pressuredropsANDeaseofclean-out, notpossibleinconvolutedhoses.

YOURCHOICEOF OUTERBRAIDS

XS:StainlessSteel

CRIMPCOLLARS TwostylesallowXRPRace CrimpHoseEnds™ tobeusedontheProPLUSRace Hose™,StainlessbraidedCPEracehose,XR-31 BlackNylonbraidedCPEhoseandsome convolutedPTFEhosescurrently onthemarket.Black,Gold andSuperNickel.

XM:LightweightXtraTempMonofilament

XK:AramidFiber

XT:Tubeonlyforinsidefuelcells

EXTERNALCONVOLUTIONS

Promoteshoopstrengthfor vacuumresistanceand supportstightbendflexibility.

Formula 1 is the greatest challenge a manufacturer of mechanical components may ever be confronted with. We have embraced this challenge and have attained the status of top supplier with our high tech products.

At Kaiser we manufacture the Chassis-, Engine-, and Gearbox Components our customers require.

... JUST GOOD IS NOT GOOD ENOUGH FOR US!

Igrew up in Australia, and my attention focused on the highly popular top level of Touring Cars known now as Supercars, with legends such as Peter Brock, Dick Johnson and Jim Richards behind the wheel. Being born in what was effectively the ‘Ford town’ of Geelong, you can imagine my allegiances lay firmly with Ford, and therefore Dick Johnson.

Personal allegiances aside, Australians are well known around the world as sports lovers, and the domestic Touring Car series competes well against other national sports such as the AFL (Australian Football League), rugby and, of course, cricket. For me, effectively growing up in nearby Melbourne, we also had Formula 1, which has long been a draw for the population.

Away from the big league(s), grass roots motorsport is also incredibly important to the popularity of the sport in any country, and home-grown talent is one of the best ways to engage with the population. Good examples at the moment from Australia are Daniel Ricciardo, despite his position this year as a test driver, and Oscar Piastri, both of whom carry with them a strong national following.

It is well known that when a local sports personality hits the world stage, the sport from which they have come often generates many more keen young followers, some of which at least eventually head down the same path.

In my example, it was the Adelaide Grand Prix, and Alan Jones who sparked my interest in adding international motorsports to my radar. In parallel, I was spending my spare time at university working on Formula Fords, Borland Racing’s Spectrum 05b to be accurate.

Formula Ford was, and still is, an important part of the fabric of racing in Australia, with both state series and national series following the national Supercars Championship.

The big hitters may grab the headlines, but it is these grass roots racing series that are within economic grasp of many people to try and experiment with motorsport.

What I have also noticed while travelling the world since is that big national series often follow a vibrant local car manufacturing market. Super GT in Japan is a good example, but also NASCAR IndyCar, IMSA (plus many others) in the USA, the BTCC in the UK and DTM in Germany, although the latter is going through quite a change in identity at the moment.

What about single seaters vs roadgoing form factors? I would say it depends on local strength of manufacturing. Those countries with homegrown vehicles normally offer more roadgoing racing series because the manufacturers have a vested interest in that type of motorsport.

Take DTM as an example. With the big four manufacturers having high-end products that

Market size, number of dominant players and breadth of choice all make a lot of sense in the dynamics of local racing. This then leads on to high profile international meetings, such as the Macau Grand Prix for Formula 3 cars, using the best drivers and teams from domestic series around the world.

At certain times during the last few decades, various of these top national series have been broadcast worldwide. In Australia, we grew up watching IndyCar, BTCC and Formula 1, as well as our local favourites, of which the Bathurst 1000 was the domestic pinnacle.

The same is true of the Monaco GP, Indy 500 and 24 Hours of Le Mans, the trifecta of global motorsport events that only very few have been fortunate to witness in person. There are, of course, many other events that are hugely important to their local populations.

Much like Olympic athletes, who train extraordinarily hard for the chance to compete every four years against the very best in the world, it is important for those in motorsport to also compete against the best other countries have to offer.

World Champion, or Olympic gold medallist are the highest honours an athlete can attain.

The same is true of the FIA’s world championships in Formula 1, Formula E, the WEC, WRC, and also the MotoGP. Each one of these top-level championships requires a different type of skill set, and precious few have the ability to cross the boundaries between them.

matched the ethos of the series, the racing was strong, although ultimately costs spiralled out of control, and then support ran out, for reasons that can be explored in another column. That left manufacturers with the GT3 option that they adopted last year.

The situation is similar in Japan, with each of the country’s main manufacturers having highend sports cars suitable for racing in Super GT.

Where competition is not as strong for roadgoing vehicles is often where single seaters step in. Examples are Toyota in New Zealand, Ford in Australia and Formula Nippon in Japan,.

The bottom line, though, is that one cannot survive without the other. The national series around the world provide the roots, and the experience drivers develop racing within them is better when the competition around them is higher. This also provides the fan base for racing when the international series come to town.

In the case of the Melbourne Grand Prix, if it wasn’t for local drivers, Alan Jones, Mark Webber, Daniel Ricciardo and now Oscar Piastri leading the charge toward the international stage, the race wouldn’t sell out locally in the matter of hours it does now.

Market size, number of dominant players and breadth of choice all make a lot of sense in the dynamics of local racing

The FIA’s Rally2 (the category formerly known as R5) has been a resounding success, with manufacturers such as M-Sport and Skoda selling hundreds, if not thousands, of cars to customers since the cost-capped rule set arrived in 2012. However, at one step down from the top of the current rally pyramid, Rally2 can hardly be described as accessible, with contemporary machines coming in north of €200,000 (approx. $219,500) after tax. A bargain for what they are, but a significant jump from the 2WD vehicles present in the Rally4 class.

Since the effective demise of Group N4 (think Evos and Imprezas) there hasn’t been a logical stepping stone into 4WD competition. Enter Rally3, the new middle rung of the FIA’s much-vaunted progression pyramid.

Rally3 cars are cost capped at just over €100,000 (approx. $110,000), a significant saving over a Rally2, and compared to the few Group N4 cars still available.

As

its

the future looks

for

‘The technical regulations are quite open, which makes it interesting for us as engineers to work’

Yann Paranthoen, chief engineer and project manager on the Clio Rally3

The idea is that by ensuring commonality of many parts with Rally2 cars, but with the addition of a four-wheel-drive system and some extra power, cost can be kept bearable.

To date, only M-Sport has homologated a car (the Fiesta), but with the class presenting clear sales potential at both international and national rally level, there is plenty of interest from other manufacturers.

The front runner among these is Renault or, more specifically, its customer motorsport department, Alpine Racing (previously known

as Renault Sport), which, at time of writing, was finalising homologation of a Rally3 variant of the company’s popular Clio model.

According to Yann Paranthoen, chief engineer and project manager on the Clio Rally3, the class appealed from the outset.

‘We started looking at the regulations three years ago,’ he says. ‘They were very interesting because of the cost cap, which is good for customer racing. But the technical regulations are also quite open, which makes it interesting for us as engineers to work on.

‘We worked out we could sell a viable number of cars and, when we did the business plan, it was clear we could create a car that was enjoyable to drive and interesting for our customers to run. So we said, let’s go, and started the project.’

Though the starting point was the Rally4 variant of the Clio, Paranthoen is at pains to point out that Rally3 is more than just its junior sibling with two extra driven wheels. Equally, it is far removed from a Rally2 car, with the price kept in check partly by the cost

By ensuring commonality of many parts with Rally2 cars, but with the addition of a four-wheel-drive system and some extra power, cost can be kept bearable

cap, but also through the use of a significant proportion of series production parts.

‘I’d say 40-45 per cent of the components are production sourced,’ he confirms.

A good example of this mixing of factory and bespoke racing parts is the suspension. At the front, the crossmember, as is the case with Rally4, is taken directly from the production line, so is the hub, with the wishbones and caster rod the only parts produced by Alpine.

Evidently, at the rear, though, a departure from stock is necessary because the standard car has a beam axle. This is therefore replaced with a bespoke subframe and MacPherson struts, with the rules requiring commonality of many components front to rear.

‘You take the wishbone, hub carrier and damper and use them at the rear as well,’ explains Paranthoen. ‘This is a good approach because [the unit cost] of producing 100 wishbones is less than if you produce 50 [fronts and 50 rears] so it keeps the price down.’

Not only does this mean a lower overall car cost, it helps make spares inventory more efficient for teams, too.

‘We worked a lot on the kinematics at the front and rear,’ adds Paranthoen, caveating that this development had to be within the constraints of technical regulations dictating the use of ‘factory’ inboard locating points.

‘We can move the front and rear wishbone mountings and the top mounts within a 20 x 20mm cube. It is not as much as we would like, but within this displacement we were able to refine the kinematics,’ he adds.

One particular challenge was achieving sufficient wheel travel within the confines of the standard wheelarches, which must be retained by regulation.

‘It is hard to make a satisfactory suspension system with only 180mm of travel,’ states Paranthoen. ‘We did a lot of work to optimise the wheelarch and kinematics to [allow us to] increase the stroke of the dampers. We ended up with better wheel travel and kinematics, and the result is a car with good handling.’

He adds that exterior body panels must also remain entirely stock, so ‘optimising’ the ’arches meant careful adjustment of clearances between parts, hence the comment, ‘We found every millimetre we could.’

Life was made slightly easier at the rear, with some minor changes permitted in order to accommodate the new axle sub-system, though Paranthoen says suspension travel is the same front and rear, helping achieve a balanced handling platform.

The Clio is powered by a production-sourced, 1300cc, 16-valve, turbocharged I4 engine with direct injection. It’s the same basic engine as found in the Rally4 car, but with its power and torque increased to 260bhp and 415Nm respectively, following what Renault says were nearly 300 calibration runs.

Compared to the Rally4 engine, however, the four-wheel-drive version is fitted with a different specification of turbocharger, with mapping to suit, which is instrumental in liberating the extra power.

‘It is quite huge performance for 1.3-litres,’ remarks Paranthoen proudly, adding that driveability was a primary concern. ‘We wanted to have plenty of power between 3500 and 6500rpm, so that the driver can really push the engine. With the Rally4, they must shift up at around 5500rpm, whereas with this, they can push all the way to 7000rpm. The engine is a big part of the pleasure of driving this car.’

Of course, being a customer and budgetfocused machine, this performance, or pleasure for that matter, couldn’t come at the expense of reliability, and Renault is confident the Clio delivers on that front, too.

‘I’d say 40-45 per cent of the components are production sourced’ Yann Paranthoen

‘There is a small rebuild at 3300km, then a full rebuild, or engine change, at 10,000km. That means you can easily do two or three seasons of national or international rallies,’ says Paranthoen.

Contributing towards the impressive service intervals and performance are a selection of uprated internal parts, including a new crank, rods, pistons and bearings, as well as more aggressive cam profiles. Other than that, a large proportion of the engine is production specification, albeit assembled with particular care and attention.

Much like Rally2, the concept of production sourced does not necessarily mean the base vehicle, or even from the same manufacturer. The Clio’s charge cooler is a case in point.

‘The rules say you have to take one from a serial production car, of which there have been at least 2500 produced,’ says Paranthoen. ‘So we could have taken one from a Mercedes, or other make, but it is a Renault part, and we are happy with the cooling performance of the car.’

The engine is mated to a five-speed Sadev gearbox with limited slip differentials front and rear. The rules do not force a specsupplier transmission on manufacturers, but there are tight design constraints, and Sadev produces an off-the-shelf unit for Rally3.

For Alpine, the choice to go with a fellow French company was a logical one: ‘We have worked with Sadev for a long time. The transmission is mainly off-the-shelf, but we have worked with them on ratios and some areas of the casing design,’ notes Paranthoen.

Front and rear LSDs are supplied by ZF, but there are no centre differentials in Rally3, only a rear axle disconnect working in unison with the handbrake. The differentials are available with a choice of two different sets of ramps front and rear.

‘We were keen to have the same transmission and differential from gravel to tarmac,’ says Paranthoen, ‘so when you buy a gravel car, but you want to do a tarmac rally, you don’t have to change the differential. If the drivers want to play with differential behaviour, they have the choice of ramps and, of course, preload can be changed as much as the driver wants.’

‘There is a small rebuild at 3300km, then a full rebuild, or engine change, at 10,000km. That means you can easily do two or three seasons of national or international rallies’

Yann Paranthoen

As the cooling outlets in the bonnet are the only other area of aerodynamic development, a detailed study was made of these partsCar only has a 1.3-litre, four-cylinder engine, but uprated crank, rods, pistons and turbo, along with a new map, has liberated an impressive 260bhp / 415Nm output, with 10,000km reliability

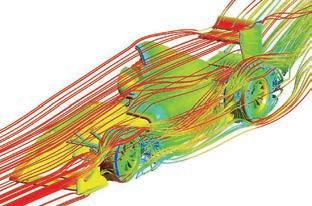

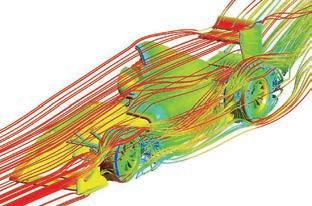

Take cutting-edge wind tunnel technology.Add a 180 mph rolling road. And build in the best in precision data acquisition capabilities.When we created the world’s first and finest commercially available full-scale testing environment of its kind, we did much more than create a new wind tunnel. We created a new standard in aerodynamics.

Take cutting-edge wind tunnel technology. Add a 180 mph rolling road. And build in the best in precision data acquisition capabilities. When we created the world’s first and finest commercially available full-scale testing environment of its kind, we did much more than create a new wind tunnel. We created a new standard in aerodynamics.

704-788-9463

With the idea of making a cost competitive package, rather than just a base car requiring many add-ons, the development team made every effort to minimise the number of changes needed to swap between tarmac and gravel specification.

‘We change some of the parts between the hub and the wishbone to adjust the kinematics a little bit from tarmac to gravel,’ summarises Paranthoen. ‘Of course, the brake discs change because you have 330mm tarmac discs and 294mm gravel disc for the fronts. On the rear, it’s the same [294mm] disc from gravel to tarmac. Of course, we change the dampers from gravel to tarmac and the wheels, from 15in to 17in on tarmac, so it’s mainly at the kinematic points we make changes.

‘All the other parts – the subframe, gearbox, rear differential, brake calipers, engine… remain the same.’

There is virtually no regulatory freedom for aerodynamic development in Rally3, but this didn’t stop Alpine Racing’s engineers leaning on the expertise of their Formula 1 colleagues in Enstone.

‘We worked with the Enstone factory on development of the rear wing but, beyond that, we are not able to work on any other areas,’ confirms Paranthoen. The result, he notes, is a very efficient design, and one that has a surprising impact on the overall car.

‘When we did the test with and without the rear wing, we found there was a significant difference in performance,’ he notes. ‘At the beginning of the process, I was not sure about the aerodynamic effect of the rear wing, because rally is not Formula 1; the average speed is quite low – just 80-90km/h. That’s very low compared to GT cars or Formula 1, so I thought the aero effect would also be very low, but I was wrong. It has a big

impact on the handling and car behaviour and is an area we have found to be important to the car. Not the main one, but important.’

The only other element of the design with any leeway for aero development is provision in the rules for cooling outlets in the bonnet.

‘We did quite a few studies around those openings, and of course we picked the best solution’ Paranthoen says. ‘Overall, although the aerodynamic freedom is small, you have to work on it.’

Testing of the Clio Rally3 began in May 2022, and the programme was completed six months later, after 22 days of running and more than 4500kms covered on a combination of tarmac and gravel surfaces, with eight different drivers and 11 co-drivers representing a broad range of experience. The development team was happy that the car met all the objectives set for it, including reliability and performance indicators on representative stages and conditions.

Given that the car will be piloted by everyone from young hot shoes to more mature, national rally drivers, it was imperative the programme account for this.

‘With the eight drivers, we worked to adapt the car to their different driving styles,’ says Paranthoen. ‘We were looking at the engine, and the handling, and set-up. When you are using so many drivers, of course [the final] car is easier to drive.’

There is also plenty of tuneability built into the car for drivers to fiddle with, if they so wish. Beyond the previously mentioned differential options, there are also four different engine maps available, selectable on the fly by the driver, as well as three settings for the anti-lag system.

‘The driver can easily change the behaviour of the engine quite significantly,’ says Paranthoen.

With the Clio’s homologation set to be completed by the end of April this year, deliveries of customer cars will commence shortly, though the car’s first semicompetitive outing was as the zero car on the Rallye Terres des Causses at the start of April.

‘The times were quite good and, in the next few weeks, customer cars will be delivered,’ confirms Paranthoen. ‘We will be looking to produce one car per week. The first official rally will be at the start of May, with cars competing in France, and one car will also be on the Targa Florio in Italy.’

Fittingly, a car will also be running in the Dieppe round of the French national championship in early May, the town where all of the Rally3 machines will be built.

Alpine Racing plans to build between 100 to 120 Clio Rally3s, and Paranthoen is positive they will be well received by customers.

‘It’s not only half the price of Rally2 to buy the car, our calculations put the cost at around €25 per kilometre on tarmac, and €29 on gravel, which makes it very competitive. The performance is not as high as Rally2 but, if we can be only one second per km slower, that is a very good result.’

There is virtually no regulatory freedom for aerodynamic development in Rally3, but this didn’t stop Alpine Racing’s engineers leaning on the expertise of theirThe Rally3 Clio has been deliberately designed to require minimal modification between gravel and tarmac stages, just the front brakes, dampers, wheels and a minor adjustment to front suspension kinematics

That the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA) is based in Paris is well known. That global motorsport’s governing body has offices in Geneva equally so. Little known, though, is that the Federation operates a third facility, this time based in the hamlet of Valleiry (population 4500), which virtually straddles France and Switzerland. Indeed, so small is the village, its only taxi driver needed to be pre-booked to take me to Geneva.

Opened in early 2014, the FIA’s double storey (4000m2 per floor) Centre of Excellence (CoE) is housed within the confines of a former fruit canning factory. Managed by Xavier Cahen, who has widespread experience in air freight and logistics, the state-of-the-art facility is a recognised freight consignor, meaning goods sealed in the building are accepted as having passed international customs and goods handling requirements.

You could easily pass through the tiny, quiet village of Valleiry on the French / Swiss border, missing the FIA’s Centre of Excellence entirely. Racecar stopped for a chatPhotos: FIA