TRAVEL

Historic towns & dramatic landscapes at England's heart

TRAVEL

Historic towns & dramatic landscapes at England's heart

WIN a luxury stay on a country estate

Beauty secrets of Elizabeth I

Best Scottish castle stays

Country house opera

Helen Mirren's favourite places

New experiences at the palace

VE DAY 80

A veteran remembers

WORDS CAROLINE BUTTERWICK

North Staffordshire has a proud history of pottery, and Stoke, the historic capital of the Potteries, celebrates its centenary as a city this year. But as our writer discovers, it’s not all pots and plates

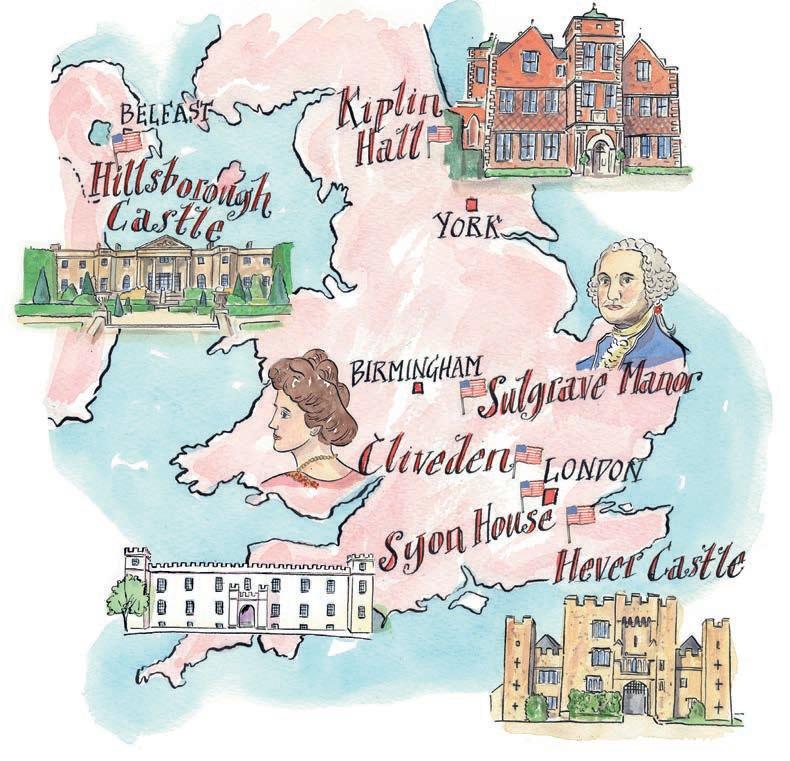

These English stately homes have American connections going back centuries, which continue to endure

WORDS FELICITY DAY

When the curtain rises on Glyndebourne’s first ever production of Richard Wagner’s final work Parsifal this summer, it will reveal a cast of nearly 200 world-class performers in a magnificent, purpose-built opera house deep in the rolling hills of East Sussex. Revellers in spangly gowns and black-tie finery will sip champagne and picnic on immaculate lawns during the sprawling, 90-minute intervals almost as famous as the performances themselves.

Glyndebourne’s summer festival, globally renowned for its excellence, is a far cry from the festival’s modest origins: an amateur entertainment dreamed up by an opera-lover and his muse on their honeymoon.

There has been a house at Glynde Bourne (as it was often spelled) since the 15th century. The present house’s appearance is mainly from the 1870s, when its Victorian owner William Langham Christie added an extension with bay windows and fancy brickwork to conceal the building’s 17th-century facade.

Glyndebourne’s most famous alteration, however, was made by Langham Christie’s grandson John, who came into legal possession in 1920. An obsessive music-lover, John added a magnificent organ room (usually open for audience members to enjoy) containing one of the largest non-cathedral organs in England. Alas, today this fabulous instrument is a beautiful shell, thanks to John’s generosity after the Second World War when he donated various internal workings to chapels and churches whose organs had been badly damaged in the Blitz.

That room is where it all began. John Christie held regular amateur musical evenings there, soon supplemented with professional musicians. One such evening in 1931, John met soprano Audrey Mildmay

The summer festival at Glyndebourne is a stalwart of the social season, where glamorous revellers attired in black tie picnic on the lawns before enjoying a spectacular night at the opera

Blenheim’s historic kitchens have been opened in a new permanent exhibition, shining a light on an up-till-now hidden world of servants and service

Legend has it that Blenheim Palace’s staff could tell which service bell was ringing simply by its tone, without even needing to look at the room to which it corresponded. No mean feat considering the iconic bell system, still partially in use today, is made up of no less than 50 bells. Maids and footmen could even be roused from their sleep by the bells installed in their rooms, at their master’s beck and call whatever the hour. Prerequisites of life as an employee here? Hard graft, dedication –and a good ear.

Designed by architect Sir John Vanbrugh (also of Castle Howard fame), Blenheim Palace was built in the early 18th century for John Churchill, the rst Duke of Marlborough, near the town of Woodstock in Oxfordshire. Churchill was awarded the money and land to build his amboyant Baroque residence by Queen Anne, who was delighted by his victory over the French at the Battle of Blenheim in 1704. The Battle changed the course of European history and helped to stop France from winning control of Spain. At a nal cost of £58m in today’s money, and no end of bust-ups between Sarah, the rst Duchess, and Vanbrugh, this “monument to victory” was eventually nished in 1733.

Blenheim is famous for being the only non-royal, non-episcopal country house in Britain bestowed with

the title ‘palace’, as well as being the birthplace of great wartime leader, Sir Winston Churchill. Its history has tended to focus on aristocratic extravagances and characters, from the pro igate 5th Duke of Marlborough known for his inability to pay his servants’ wages, to the glittering parties of the 9th Duchess, Consuelo Vanderbilt. But this spring, for the rst time, Blenheim’s historic kitchen and wider undercroft have been opened in a new permanent exhibition, shining a light on an up-till-now hidden world of servants and service.

Rather than run-of-the-mill information boards, the experience is utterly immersive. Beginning in the delivery area where goods are checked as they come into the palace, we’re thrown back in time, theatrically positioned as a new servant arriving to help the Blenheim Palace staff of the 1890s prepare for a royal visit. “That’s the loose theme as you go around,” says Emily Spencer, Head of Operations. “You get a sense that you’re working with [the staff], rather than simply observing.”

The then Prince of Wales (Queen Victoria’s eldest son, godfather of the 10th Duke of Marlborough, and later Edward VII) did indeed visit in 1896. He’d clearly enjoyed himself there previously, this being his fourth trip. Other royal visitors included King George III in

up and down the narrow staircase