DEDICATION

for Augusta June Stewart High

APPALACHIA

BY MURIEL MILLER DRESSLER

I am Appalachia In my veins Runs fierce mountain pride; the hill-fed streams Of passion; and, stranger, you don't know me!

You've analyzed my every move-you still Go away shaking your head I remain Enigmatic. How can you find rapport with meYou, who never stood in the bowels of hell, Never felt a mountain shake and open its jaws To partake of human sacrifice?

You, who never stood on a high mountain, Watching the sun unwind its spiral rays; Who never searched the glens for wild flowers, Never picked mayapples or black walnuts; never ran Wildly through the woods in pure delight, Nor dangled you feet in a lazy creek?

You, who never danced to wild sweet notes, Outpouring of nimble-fingered fiddlers; Who never just "sat a spell," on a porch, Chewing and whittling; or hearing in pastime

The deep-throated bay of chasing hounds And hunters shouting with joy, "he's treed!"

You, who never once carried a coffin

To a family plot high up on a ridge

Because mountain folk know it's best to lie

Where breezes from the hills whisper, "you're home";

You, who never saw from the valley that graves on a hill Bring easement of pain to those below?

I tell you, stranger, hill folk know What life is all about; they don't need pills To tranquilize the sorrow and joy of living

I am Appalachia; and, stranger, Though you've studied me, you still don't know

INTRODUCTION

What is a “hillbilly?” Some argue it's a derogatory moniker for a person coming from rural Appalachia–a region that spans 13 states and 206,000 miles from Georgia to New York 1 Others argue that a hillbilly is a placeless trope; a characterization of an individual who possesses traits of a rural “rube,” including laziness, ignorance, an affinity for moonshine, and a certain uncouthness (particularly when it comes to urban environments). These arguments, and many more varied definitions, have all been invoked throughout the decades-long evolution of the hillbilly fool, which emerged as an amalgamation of several different reductive characterizations of agrarian people beginning as early as America itself. As scholar Anthony Harkins points out, “ the first uses of the term ‘hillbilly’ in print referred to the people in the bordering areas of Georgia and Alabama and the southwestern hill country of Arkansas and Missouri From its origins as a regional label, the word and image would slowly spread nationally through the works of joke book writers, professional linguists, popular authors, and motion picture producers and directors ”2 In other words, the hillbilly is, at its core, a construction

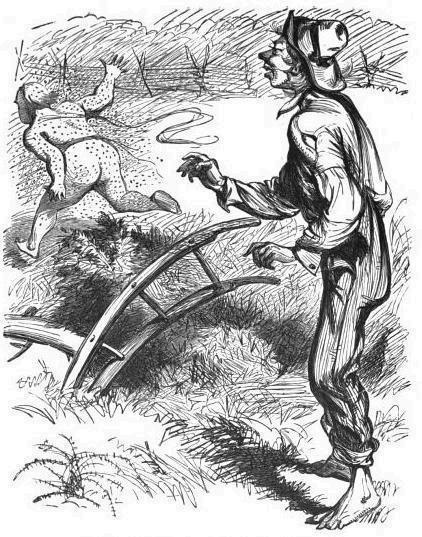

One of the earliest examples of the hillbilly construction came from Tennessee writer and humorist George Washington Harris (1814-1869) in his collection of stories, Sut Lovingood: Yarns Spun by a "Nat'ral Born Durn'd Fool" (1867). Scholar M. Thomas Inge argues, “Because Sut has no occupation and no family to support, and hence no responsibilities, he devotes his full time to the passions he most enjoys in life: telling yarns, drinking whiskey, eating rich food, chasing pretty girls, breeding scares among those he dislikes, and ‘raising hell’ in general.”3 Lovingood was Harris’ idea of a “typical Tennessee mountaineer” and inspired a number of characterizations that came after including comic book sensations Snuffy Smith and L’il Abner from the 1930s, which will be discussed in Chapter 2.

1 https://wwwarc gov/about-the-appalachian-region/

2 Harkins 56

3 https://wwwjstororg/stable/42621491

Justin Howard (illustration) - George Washington Harris, Sut Lovingood: Yarns Spun By a Nat'ral Born Durn'd Fool (New York: Dick and Fitzgerald, 1867), p. 24. Downloaded from Google Books, Full View

Illustration accompanying George Washington Harris's short story, "Sut Lovingood's Daddy, Acting Horse." In the illustration, Sut Lovingood (right) watches as his father runs away from what he perceived was a swarm of hornets

A close examination of the hillbilly moving into the 21st century reveals a departure from the Sut Lovingood character. By way of explanation, one can look at the 2019 music video from pop superstar Taylor Swift, who proudly displayed her idea of a 21st century “hillbilly” for her single “You Need to Calm Down ” Swift enlisted a slew of celebrity icons for the video, who can all be seen enjoying a candy-coated paradise in a former trailer park. In addition to these glamorous celebrities, Swift and her co-director Drew Kirsch recruited several extras to serve as “the opposition,” or those to whom the directive to “calm down” is leveled. While Sut Lovingood and his counterparts throughout the turn of the 19th century were humorous, yet harmless–the rural representation in Swift’s video is decidedly more sinister Swift’s hillbillies are shown screaming, bearing their teeth, and shaking their fists. They are angry and confrontational while neglecting their duties (note the several pieces of farm equipment scattered around them, unused), in order to confront Swift and her comrades It may be safe to assume that Swift’s intention was not to disparage Appalachian people, but rather to reflect progress and solidarity in the face of opposition from what she viewed as conservative critics As the lyrics suggest:

“You are somebody that we don't know, But you're coming at my friends like a missile, Why are you mad when you could be GLAAD? (You could be GLAAD) Sunshine on the street at the parade, But you would rather be in the dark ages, Making that sign, must've taken all night…”4

A 2023 article in The Appalachian Journal argues “While this video represents a simplistic, yet common, perspective on 21st-century ‘culture wars,’ Swift missed the mark when she created a dichotomy of ‘us’ vs ‘them’ them being a summation of nearly every Appalachian stereotype in existence, and ‘us’ being her more evolved supporters. Her staged group of anti-gay protestors wield misspelled, homophobic signs (i.e. ‘Get a Brain Morans’ and ‘Homasekualty is Sin’) and wear muted flannel, denim, ballcaps and American flags a direct contrast with the bold, rainbow aesthetic of those inside the queer trailer park.”5

4 Republic Records

5 Brislin and Carr, Appalachian Journal, volume 50 2023

https://wwwyoutube com/watch?v=Dkk9gvTmCXY

1:36/3:30

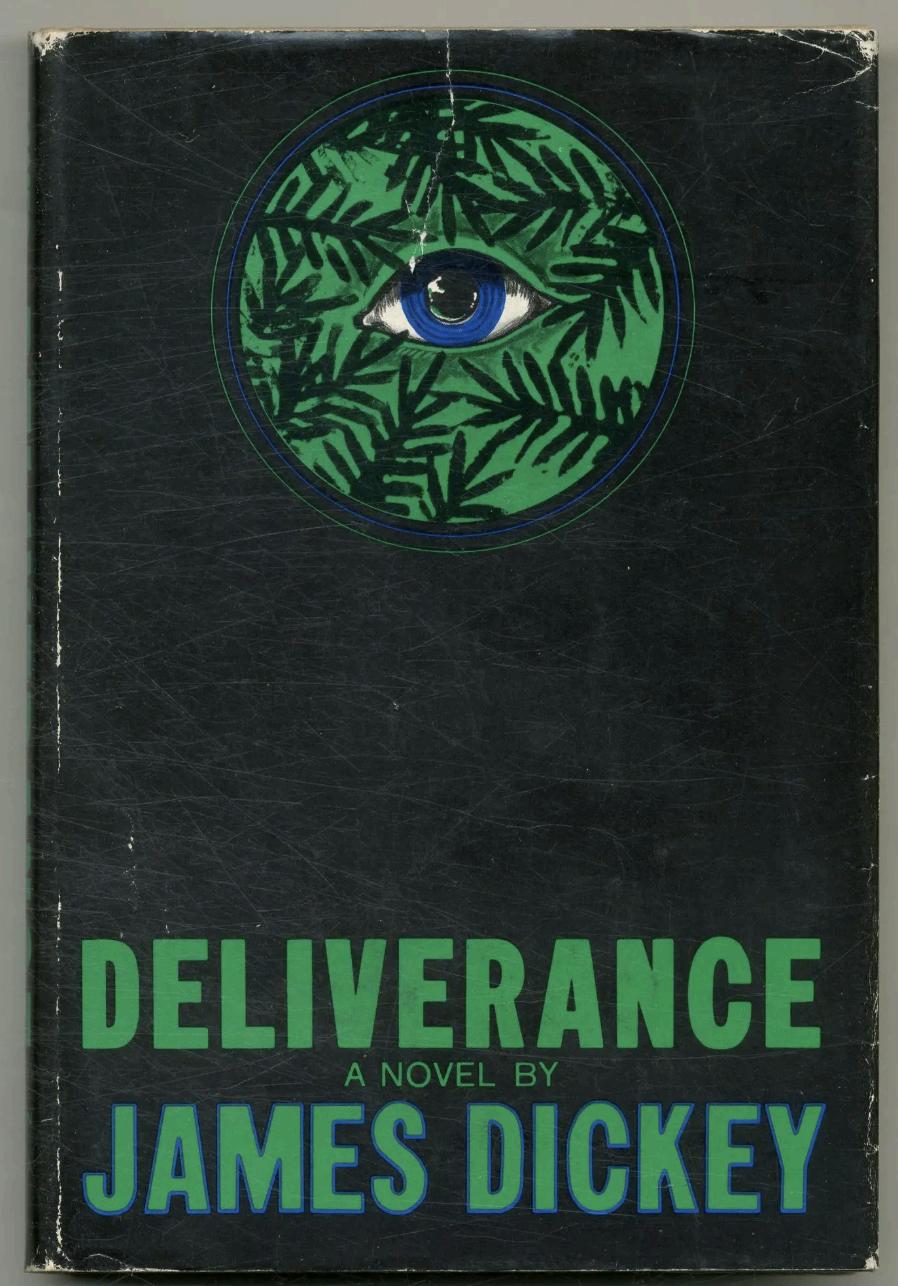

The lack of attention paid to the representation of what were presumably rural Americans as a displaced mass of angry, uneducated illiterates did little to raise eyebrows After all, the 21st century image of the hillbilly is often angry and violent. For further evidence, one need only look toward variations of the hillbilly in media dating back to the 1970s with Jon Boorman’s Deliverance (1972), when two men appear from the depths of the wilderness to violently assault urban men on a canoeing trip Angry, homicidal hillbillies get repeated throughout the late 20th and early 21st century with films like Wrong Turn (2003), TV shows including X-Files (1993-2002) and video games. In his chapter, The Anti-Idyll: Rural Horror, David Bell writes of popular media:

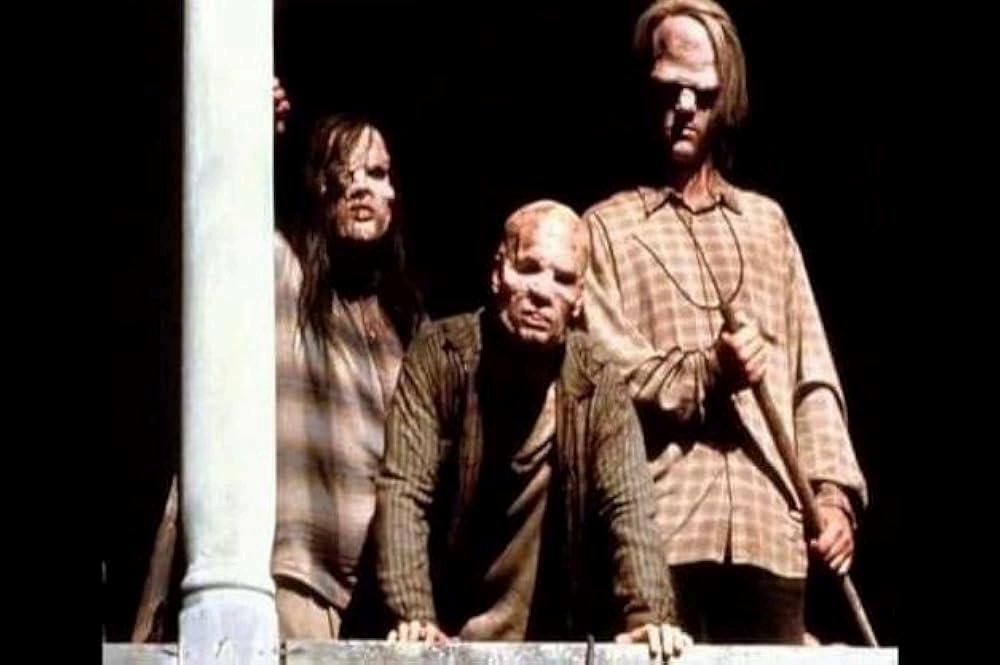

“[...] they use country folk in the role of monster or murderer (usually a hybrid of both). Whereas in the classical Hollywood horror film (such as Universal Studios’ Frankenstein movies), the monster invades the village and it's up to the villagers to pull together and defeat it (often drawing on folkloric local knowledge, community cohesion, and resource pooling), in the films featured below the villagers are the monsters, and they often cannot be defeated.[...] Trading on assorted cultural myths–of inbreeding, insularity, backwardness, sexual perversion (especially incest and bestiality)--these rural “white trash” are familiar popular culture icons[ ] ”

The central question this book will address is when, and how, this branch of hillbilly representation developed It is important to note that the image of what I will henceforth refer to as the mountain monster did not develop in place of the hillbilly fool, but rather, became a fluid branch with its own tropes and associations woven throughout pop culture media The fool has

continued to manifest in pop culture and still exists within “redneck” jokes, tasteless cartoons, and sitcom characters.

“Chapter 1: The Hillbilly Highway” explains the predecessors to the media creation of the mountain monster image. During the Great Migration, a movement historically associated with African Americans’ migration North following emancipation, a large number of Appalachians similarly sought better economic opportunities in northern, industrial cities Urban individuals quickly found the customs and culture of these rural migrants distasteful, especially considering that most were white Many anxious urbanites went so far to declare them a “disgrace to their race ”6 In response to the outcries from neighborhoods and law enforcement across Chicago, Cincinnati, and Detroit, journalists zeroed in on these “primitive” newcomers, painting them as one of the most “serious threats” against urban progress the North had ever seen 7 The non-fiction accounts of Appalachians as violent, ill tempered, sexually deviant, and uneducated would greatly inform the pop culture mountain monster image to come.

“Chapter 2: Urbanoia and Hillbilly TV” looks at the media’s effort to sanitize these “disruptive hillbillies” in order to alleviate urban anxiety or “urbanoia” around both the disappearance of the noble frontiersmen (its own cultural construct) and the influx of unfamiliar outsiders The golden age of the rural sitcom centered on wholesome, “neutral” content Prime examples can be seen in shows like The Real Beverly Hillbillies (1962-1971) and The Andy Griffith Show (1960-1968) Audiences derived comfort and reassurance from straightforward plots and stock characters, which reinforced the idea that Appalachians were to be laughed at, not feared. Unfortunately for urban audiences, the “threat” of Appalachia did not stay sanitized for long Chapter 3 will address The War on Poverty and the flurry of accompanying documentary images that filtered through popular magazines and primetime documentaries Audiences seeking comfort in the media’s construction of a “sanitized” Appalachia were now confronted with the “real” Appalachia Contrary to the characters that had become so familiar to urban audiences, the Appalachian families featured in the gritty black and white photographs were not content with lives of poverty, isolation and ignorance; they were hard-working and in desperate need of economic restoration following the systematic exploitation of the local coal companies. For context, the 1970s had already brought deep fatigue for the war effort in Vietnam and some communities were still recovering from the Great Depression President Johnson announcing another national concern in his inaugural speech led many to feel deep exasperation, which, as it often does, turns quickly to victim-blaming.

The shift away from rural, slapstick comedy toward a more serious, documentary-style representation of Appalachia can be partly attributable to the shift in the type of media Americans were consuming. Comic books, once a popular source of entertainment, declined in popularity due to a number of factors but most notably Fredric Wertham’s anticomics book Seduction of the Innocent from 1954 and his argument for the connection between comics and juvenile delinquency 8 Simultaneously, television was competing with the advancements and accessibility of the film industry In Chapter 4 these threads: the frustration of urban audiences, the continual exposure to poverty previously unthinkable in the U.S., and the rise of the film industry converged, creating an ideal runway for the release of 1972’s Deliverance In lieu of

6 https://acloudofdust typepad com/files/hillbillies-invade-chicago pdf

7 https://acloudofdust typepad com/files/hillbillies-invade-chicago pdf

8 https://wwwebsco com/research-starters/literature-and-writing/history-graphic-novels-1960s

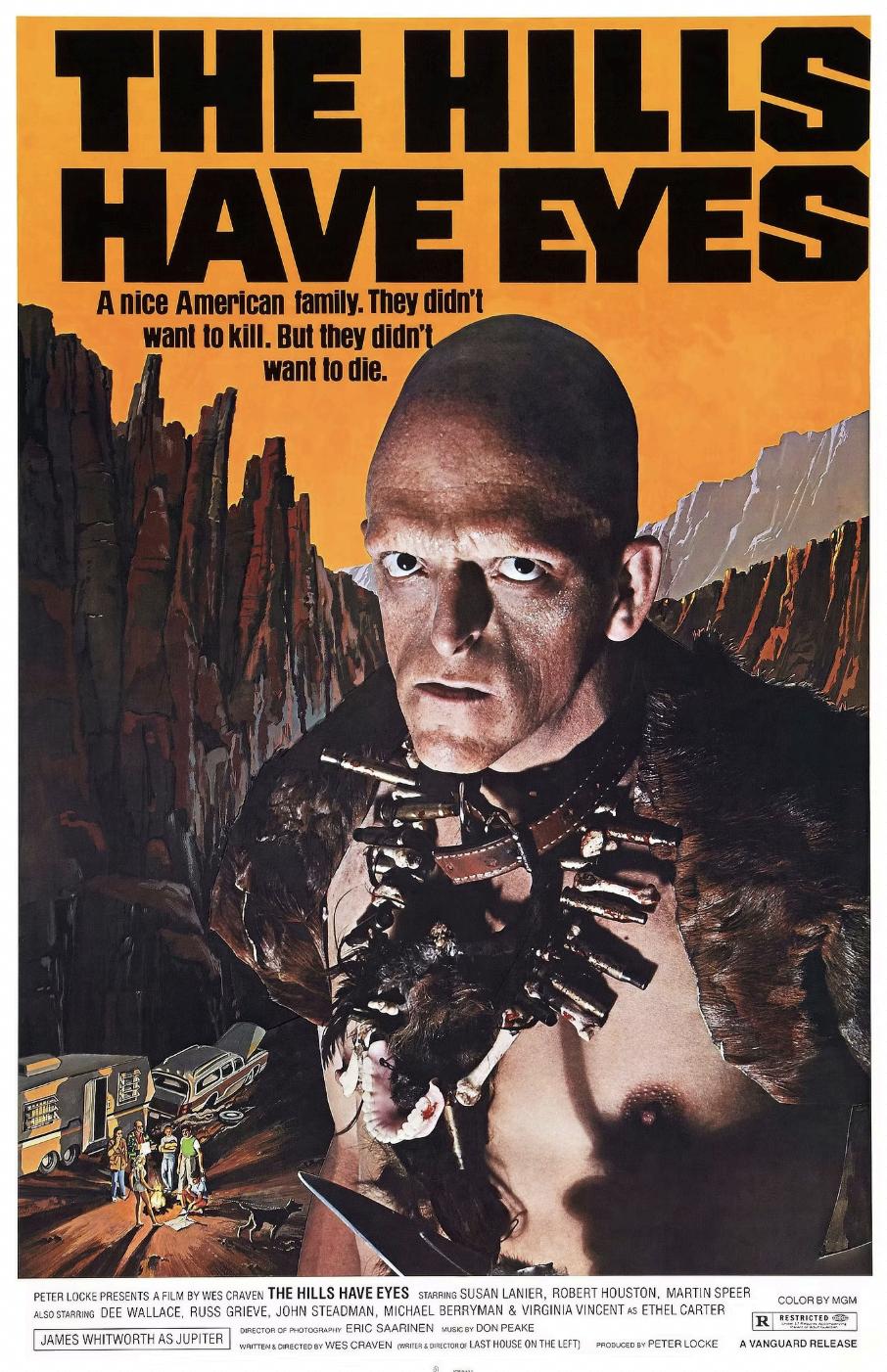

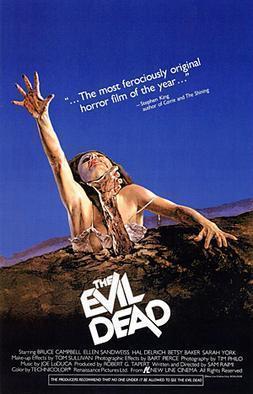

sanitized hillbilly imagery, director John Boorman leaned into the unsanitized mountain man–creating a mold that would be used for decades afterward. “Chapter 5: The Era of Hillbilly Horror” will look at how the mountain monster figures into the introduction of the “slasher” film Slasher films of the 70s and 80s were affordable to produce, operated on increasing levels of audience shock-value, and leaned heavily on hillbilly horror tropes. Audiences flew into theatres to witness “Leatherface” hunting down urbanites in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) The more shocking, the better. This obsession would bleed over into TV, with the introduction of the infamous X-Files episode “Home,” from 1996, described in “Chapter 6: 1990s and 2000s, The Hillbilly Horror Expansion ” The scandal of this episode cemented it as one of the most popular of the series and would lead to several “look-a-like” themes, even in more contemporary media like NCIS, Bones, and Criminal Minds, before peaking with 2003’s Wrong Turn

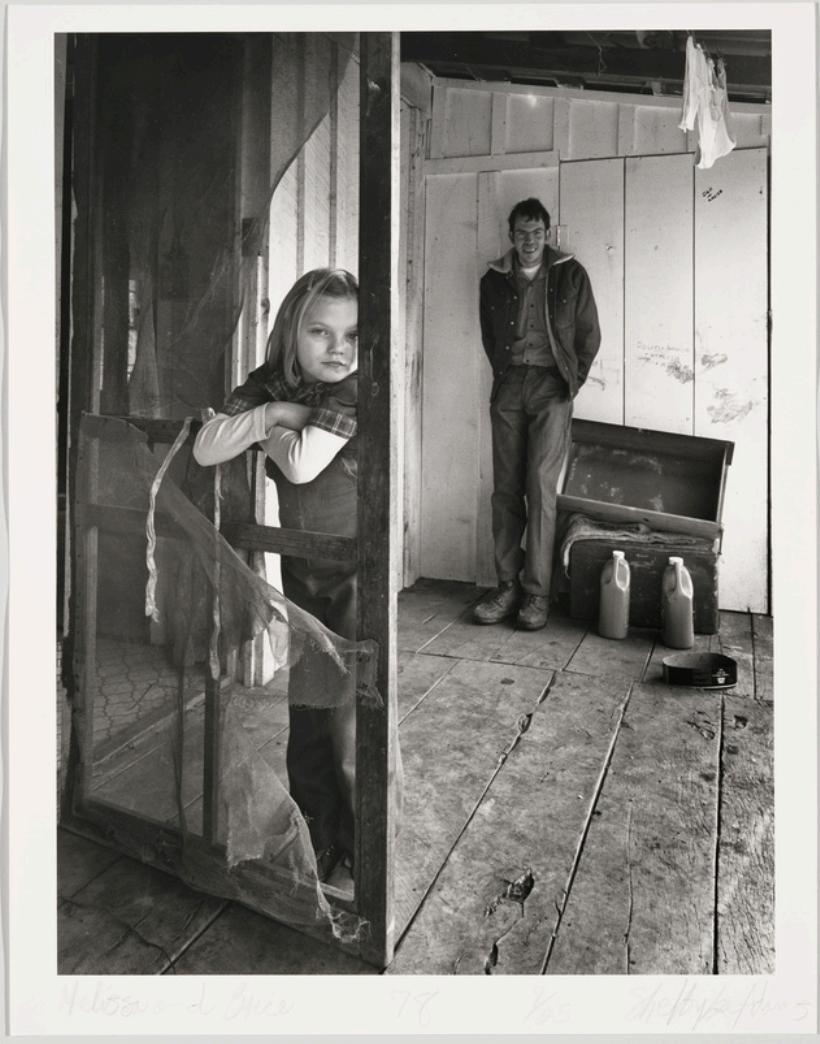

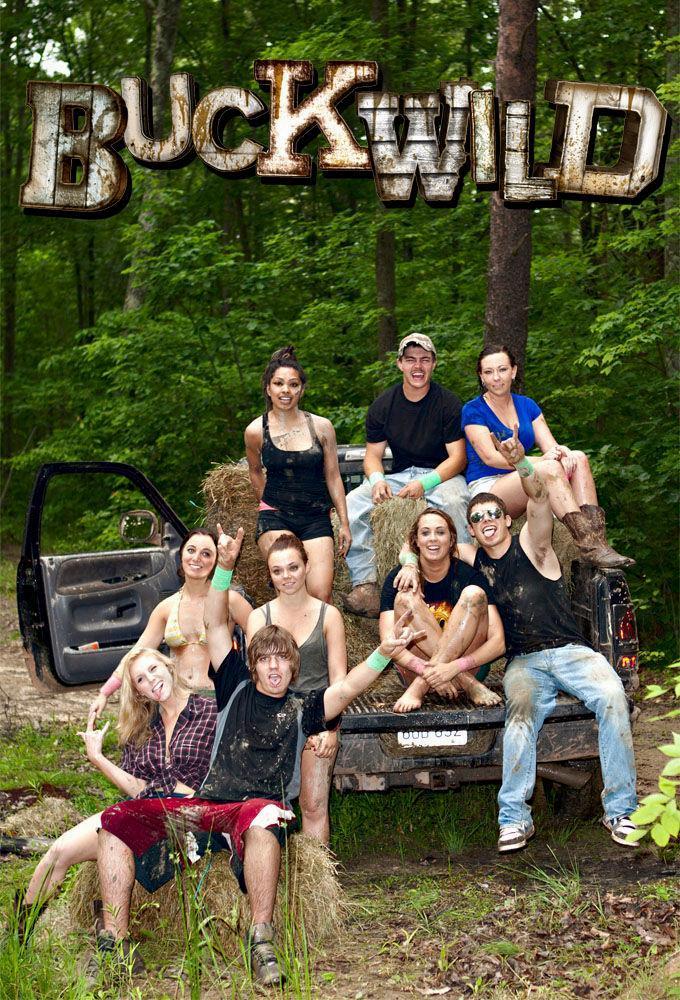

“Chapter 7: The ‘Real’ Appalachia” will look toward the launch of reality TV following the success of MTV’s The Real World. This new type of media swiftly made its way into Appalachia with The Wild and Wonderful Whites of West Virginia (2009) and Buckwild (2013), among others. Inevitably, these depictions of Appalachia as a site for unsupervised, unhinged debauchery eventually morphed into portrayals of violent territorialism in later reality TV depictions Meanwhile, Appalachia was playing a pivotal role in the world of fine art providing subject matter for artists and creatives interested in the contemporary American gothic. Guggenheim fellow Shelby Lee Adams’ gritty black and white portraits of remote Appalachian hollers have been shown in galleries throughout the United States and abroad, though his reception from the region remains similarly frosty to that of Diane Sawyer’s 2009’s Hidden America documentary Moving into more recent years, Appalachia has been at the epicenter of the opioid crisis Drug manufacturers targeted the vulnerabilities present in the region in a highly calculated way in order to maximize profit. This ongoing tragedy has led to an interesting variety of media case studies Netflix’s Fall of the House of Usher (2023) modeled its titular family on the family behind the Oxycontin fortune: the Sacklers. The intensely violent depiction slowly reveals them to be the true monsters responsible for countless deaths and endless suffering of Americans through their callous disregard of the harm they caused through their highly addictive medication. Other creatives persisted with the myth of victim-blaming, most notably Ohio native JD Vance’s memoir Hillbilly Elegy from 2016

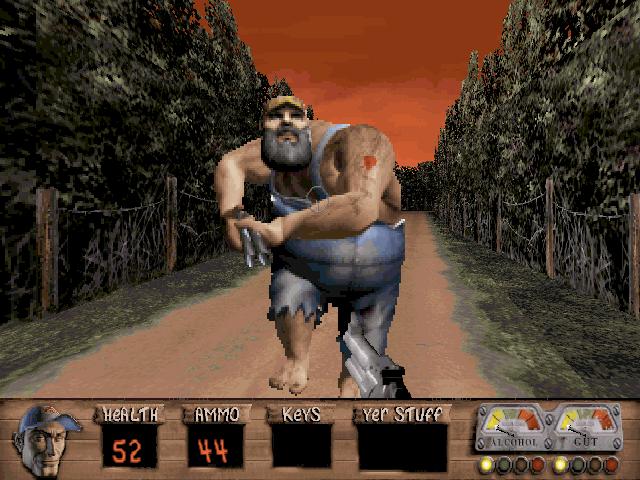

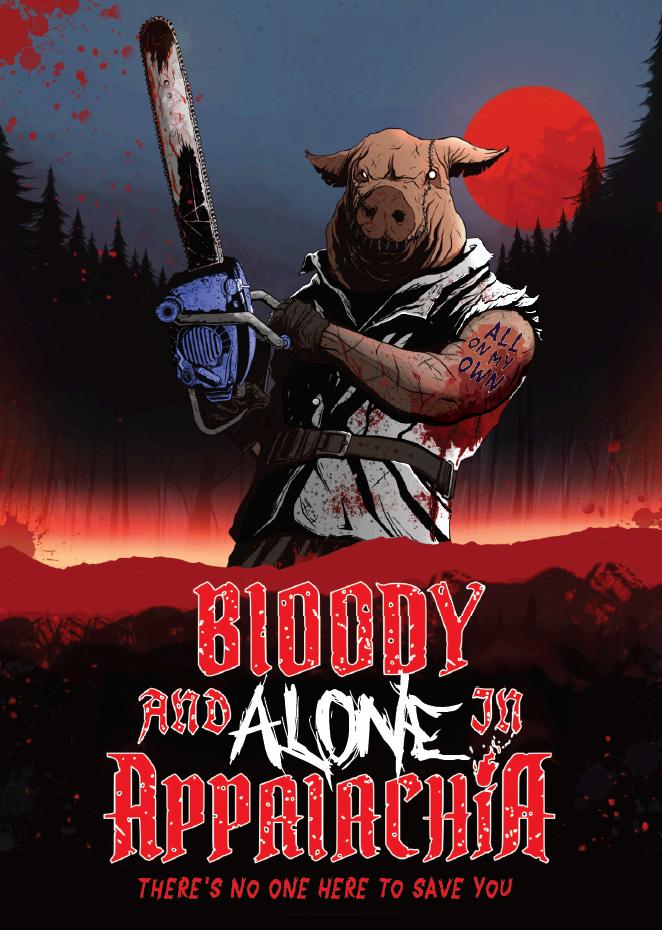

Like most contemporary media tropes, the Appalachian mountain monster has spilled over in video games, inviting audiences to participate in immersive “Appalachian” landscapes. This evolution, outlined in Chapter 8, has seen success in neutralizing stereotypes through games like Fallout 76 (2018), set in a post-apocalyptic West Virginia. Unfortunately many others like Red Dead Redemption 2 (2018) and Redneck Rampage (1997) have only reinforced the notion of the rural mountain monster In order to fully consider the reach and influence of hillbilly horror, one must also look toward the region itself. “Chapter 9: Appalachia’s Response” will outline how the region has pushed back on the narrative that has been constructed for and around them by pop culture media Cryptids, folklore, media depots, podcasts, festivals, social media, and other mediums have all been effective tools for Appalachians pushing back against harmful stereotypes, while also engaging regional creatives This homegrown media illustrates the nuance, persistence, and character of Appalachia, while also showcasing the diversity of identities and experiences throughout the 13-state region.

It is important to note that while this text focuses on exploitation and marginalization of Appalachian people, many of these same tools have consistently been used against other marginalized identities Furthermore some of the harmful rhetoric against particular race, religion, gender, and sexual orientation has been inflicted by Appalachian people, as even those who are disenfranchised and marginalized can play roles in exacting systematic exclusion on others, despite calls for allyship It is also important to clarify that this book is not intending to “plot” Appalachia on a spectrum of harm- as economic and social exclusion has had broad application throughout American history with varying degrees of impact Land ownership is also something that needs addressing While not in an exclusively homogenous manner, Appalachians, like most early settlers, displaced indigenous populations and contributed to the colonization of North America by Europeans and other outsiders Appalachia continues to be home to a number of tribal nations who experienced unprecedented violence at the expense of American expansion. This book is not making a case for Appalachian innocence or perfection; rather it is asking readers to turn their eye toward a little known tool for exploitation and the history that led us to it.

While the hillbilly fool has not left our collective psyches, it needed to evolve to adapt to our changing media preferences Characters like Snuffy Smith could be easily lifted from the colorful pages of comic books and adapted for Mountain Dew commercials or Barbersol ads, but could not sustain itself within the scope of an evolving film industry While technological advancements and societal tastes accommodated the rise of mountain monsters, it doesn’t account for their massive and nearly immediate popularity with audiences. Wouldn’t audiences who had come to love the antics of the earnest, simple hillbilly take issue with representations of rural people as sexually deviant, murderous, cannibals? The truth is that many audiences didn’t balk at these characterizations because they were already circulating, well before Lonnie’s banjo duel in Deliverance Pop culture media was picking up on portrayals that were published widely, most notably during the Great Migration of 1910-1970. Many felt that the influx of mountaineers were a hindrance to urban progress, and should be kept either back in the mountains of Appalachia, or safely contained within their TV sets where they could serve as forms for comedic escapism. Appalachians of course couldn’t, and didn’t, stay safely contained, and with this disruption came the enthusiastic embracement of the mountain monster

CHAPTER 1: THE HILLBILLY HIGHWAY

THE COAL CAMPS

Though consistently accused of stagnation throughout reductive stereotypes, in actuality Appalachians have a long history of migratory movements, beginning with the transition of nomadic fur-traders to homesteaders in the late 18th century From The Appalachian Coalfield: “Many of the region’s early settlers were agriculturalists who established what can be described as ‘backwoods farms ’ They were generally located in areas with access to water and cleared the dense timber on flatter lowland landscapes for crops. They also raised livestock, often

including hogs, by treating the woodlands as ‘open range ’ The form of agriculture practiced by the earliest settlers has been described as “yeomanesque,” or a largely self-sustaining activity.”9

As the American railroad boom took hold in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, so too did the demand for the timber and coal output. This increased need for resources to fuel urban development and expansion in larger, primarily northern cities, led to the formation of “coal camps,” or communities built around local mines These communities, at their best, provided steady work to Appalachians who were increasingly unable to adapt their homesteads to the demands of a changing economic market Coal companies would frequently build schools, convenience stores, churches, and housing that modeled a picturesque small-town to attract laborers from around the region. These Appalachian families were often forced to walk away from their “yeomanesque” lifestyles, trading “open-range” for closer quarters on the promise of steady support and educational access for their children and families

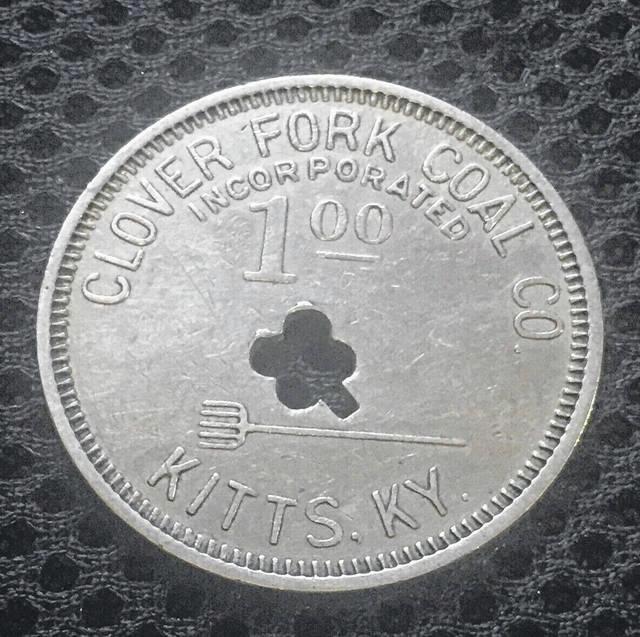

At their worst, these coal camps were highly exploitative and created dependency on both the output of the specific mine they were built around, and the (often absentee) owner who controlled it. Some companies elected to pay their miners in “scrip,” a type of currency produced by and for the specific coal camp Scrip could look like a ledger, in which purchases from the company-owned convenience store would be deducted from the miner’s pay In other cases, scrip was paper or coins issued to the miner to be used only within the camp. Charles Edward Thomas writes

“[ ]the scrip system was used extensively in the U S coal industry between the 1880s and 1950. This was true across large swaths of West Virginia and eastern Kentucky, but scrip could also be found in 34 other states By the time the Harlan County coalfields were opened in 1910, the system had already been developed and was widely implemented. [...] When laws were eventually passed outlawing direct payment in scrip, the coal companies came up with a workaround that accomplished the same thing: Scrip would be issued as an advance on wages.”10

Beyond the obvious issues with this practice, there was fear within the camps for what miners’ futures held when the mine stopped producing profitable coal Saving money was ineffective, as whatever meager savings they could accumulate wouldn't be recognized as currency anywhere outside of the coal camp While miners were sometimes offered positions at nearby mines after closures, this wasn’t a guarantee, especially if they were injured or had spoken out about working conditions. In short, micro-migration to coal camps was often an act of desperation for Appalachians, where profits operated off of laborers’ fear, exploitation, and economic exclusion

9The Appalachian Coalfield in Historical Context Carl E Zipper, Mary Beth Adams, and Jeff Skousen

10 Charles Edward Thomas, Scrip, 2

https://www.dailyadvocate.com/2021/07/28/coal-mining-scrip-a-collector-shares/

THE GREAT MIGRATION

The Gilded Age railroad expansion, ironically the very industry that facilitated the coal boom, quickly became a contributor toward its decline As urban progress continued, homes began to switch to natural gas, railroads were migrating to diesel fuel, and steel moved to electric power 11 From Philip Overmiller and Thomas E Wagner “[ ] coal mining employment reached its apogee in the early 1920s and although there were a few surges, the industry entered a steady decline. This ‘boom and bust’ pattern in mining employment loosely correlates with larger economic conditions (for example the Depression and World War II) as well as with flows of Appalachian in-, out-, and shuttle migration.”12 With the surrender of regional families’ homesteads, or in the case of Eastern European and other international migrants brought in to work in the coal mines, no homestead at all, Appalachian residents were frequently left little choice but to migrate elsewhere. As opposed to the micro-migrations they’d experienced in the decades prior, economic opportunity was now further than a day’s trip away Northern cities like Cincinnati, Detroit, and Chicago needed labor to staff their growing factories and mills, therefore Appalachians began moving north, creating what is often referred to as the “Hillbilly Highway,” or a stream of out-migrants from the region seeking economic opportunity Early sociological research was often at odds with anecdotal evidence about how Appalachians fared in these northern cities, yet more recent scholarship has begun to address such discrepancies. From “Major Turning Points: Rethinking Appalachian Migration:” “Only about a quarter of whites who left the South came from Appalachian areas. The rest came from across the vast 17-state census-defined South Ample data suggest that white Appalachian out-migrants had extremely different experiences than did other Southern white out-migrants ”13 In 2007, scholar J Trent Alexander expands on this shift in perception arguing:

“Anyone following developments in southern or African-American history will have noticed an interesting turn in recent years: The ‘Great Migration’ is no longer only about the half-million southern blacks who moved northward in search of industrial work during

11 https://wwwjstororg/stable/10 2307/48679496

12 https://wwwjstororg/stable/10 2307/48679496

13 https://wwwjstororg/stable/40934502

World War I Newer studies of the Great Migration have expanded the scope to the middle and later decades of the twentieth century, to western destinations, and-most recently--to the even larger parallel out-migration of southern whites [ ] With poverty rates around 30 percent, Appalachian migrants in large cities were economically on par with southern blacks, as well as newcomers from Eastern Europe, Mexico, and Vietnam ” 14

It is clear that Appalachians were coming from unique cultural and economic circumstances that led to stark differences in both their experience and reception during migrations to northern city centers

ED GEIN, BENNIE BEDWELL, AND APPALACHIANS AS ANIMALS

The question now becomes: what does 19th and 20th century Appalachian migration have to do with 21st century horror representations of hillbillies? The answer lies in the reception to Appalachians from urban centers like Cincinnati, Detroit, and Chicago. We know from Alexander and others that Appalachians experienced difficulty in adjusting to Northern life, but many scholars have stopped short of paying significant attention to the all-too important question of why. Differences of background, culture, and socioeconomic standing all led to social isolation of Appalachians in northern cities With isolation comes misunderstanding, cultural othering, and fear A look toward publications throughout the early to middle part of the 20th century illustrates the marginalization and animalization that took hold in the public’s perception of the region

“During the 1950s most of the writing about Appalachians appeared as sensational journalistic accounts in Northern and Midwestern newspapers or community studies issued by municipalities. Reporter Norma Lee Browning wrote a series of nine articles for the Chicago Tribune portraying Appalachian migrants in extremely negative terms She solidly established the ‘hillbilly’ motif in Chicago by linking a migrant from Tennessee, Edward Lee "Bennie" Bedwell, with the grisly murder of two teenage sisters. Bedwell fit the reporter's general profile of the denizens of the ‘hillbilly jungles of Chicago’ (1957a, 9) Her articles contained exaggerated accounts of incest, illiteracy, alcoholism, and violence. Browning (1957b, 2) wrote, for instance, that migrants despised education to the point that they ‘burned down schoolhouses and horsewhipped the teachers ”15

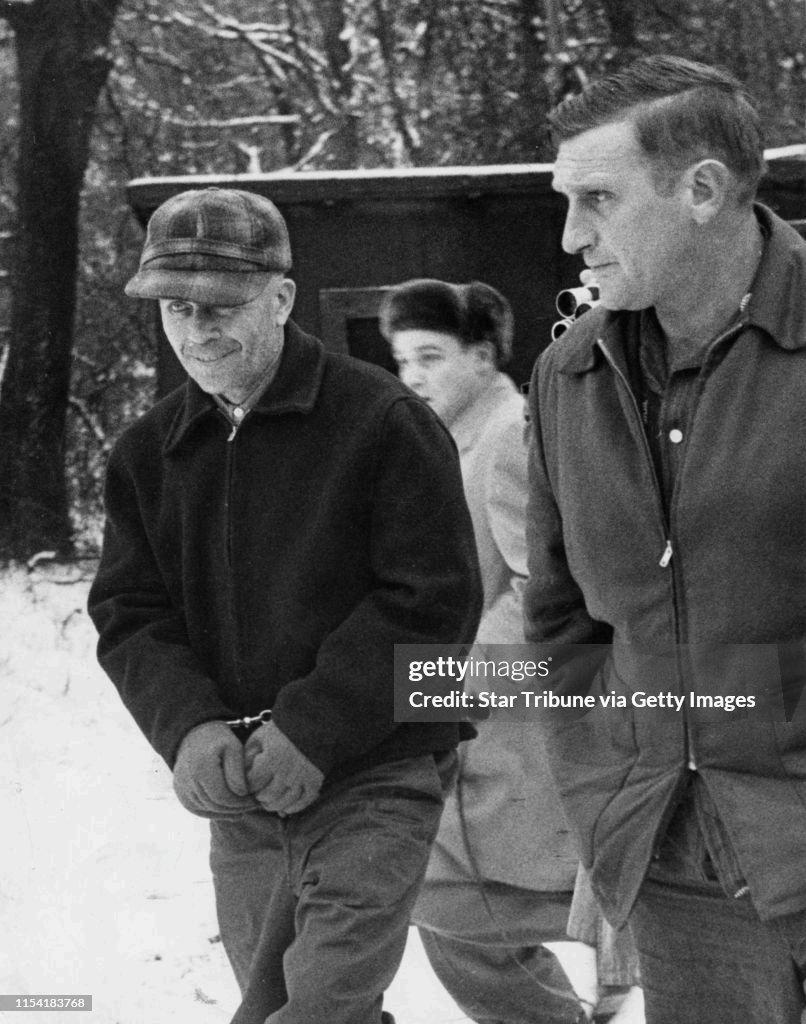

The “mountain monster” Bennie Bedwell was a semi-illiterate drifter formally charged with murder on January 27, 1957 after confessing to the gruesome attack on Barbara and Patricia Grimes, but later recanted and was eventually released after several details of his statement did not align with the facts of the case; however the cloud of urban suspicion around these “violent” and “primitive” hill people still hung thickly in the air 16 No one was ever arrested for the murder

14 https://wwwjstororg/stable/4139547

15 https://wwwjstororg/stable/40934502

16 Bailey, Frankie Y Ph D; Chermak, Steven (2016) Crimes of the Centuries: Notorious Crimes, Criminals, and Criminal Trials in American History Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO pp 325–326 ISBN 978-1-610-69593-0

of the two sisters and as of 2025, it remains a notorious cold case Less than a year later on November 16th 1957, authorities discovered a site of true horror in Plainfield, Wisconsin: the family farm of serial killer Ed Gein 17 Authorities found at least eight murdered and mutilated bodies throughout the property, along with evidence of even deeper familial dysfunction and psychological compulsions While Gein himself was not a southern migrant, the sensationalism surrounding this case opened up the imaginations of urban audiences to perversions and deviancies previously unheard of in most cases. Gein’s mother, devout in her religious vigor, and the family’s isolation on their farm also shared characteristics with the depictions of Appalachian migrants in the writing of reporters like Norma Lee Browning, further attaching them to the notion of homicidal and dysfunctional compulsions. Scholar Roger Guy points to this phenomenon, citing a Town Hall police report from Chicago: “The report added that inaccurate newspaper accounts contributed to the notorious reputation southern whites received and that certain behavior was labeled ‘hillbilly’ regardless of the person’s place of birth. This may explain the tenuous claims of an early unpublished report in which police were quoted as saying that 75 percent of their arrests and disturbances were caused by ‘hillbillies.”18

17https://wwwaetvcom/real-crime/ed-geins-childhood-the-butcher-of-plainfield-fixated-on-his-domineering -mother

18 https://journals sagepub com/doi/10 1177/009614420002600303

https://wwwgettyimages com/detail/news-photo/ed-gein-a-wisconsin-was-led-away-by-sheriff-ar thur-schley-news-photo/1154183768

Journalists were frequently warned about entering areas where there were known to be a significant number of Appalachian migrants, often referred to as “hillbilly ghettos ”19 One anecdote captures advice given to a reporter: “You better be careful going into those places. You may not come out alive to write your story”20 Iterations of this sentiment will later be found in numerous films highlighting the same caution: a run-in with a mountain monster could be your last. Several excerpts from Browning’s nine article series neatly summarize public sentiment at the time:

"It's a dangerous situation, one that we have to wake up to and face. These migrants are United States citizens, free to roam anywhere they wish But they have turned the

19 https://dailyjstororg/when-uptown-chicago-was-hillbilly-heaven/

20 Guy, R (2000) The Media, the Police, and Southern White Migrant Identity in Chicago, 1955-1970 Journal of Urban History, 26(3), 329-349 https://doi org/10 1177/009614420002600303 (Original work published 2000)

streets of Chicago into a lawless free-for-all with their primitive jungle tactics" [said Walter Devereux, chief investigator for the Chicago Crime commission].”

“[...]the southern hillbilly migrants, who have descended on Chicago like a plague of locusts in the last few years, have the lowest standard of living and moral code[ ]”

“Of 400 rape cases recently investigated by juvenile police, the majority involved migrants who didn't even know what the word meant ”21

Words like “jungles,” “roam,” and “primitive” all point to Appalachians as being less-than human and draw a clear parallel with the mountain monsters we will see emerge later in 21st century media This marginalization was applied to many ethnic groups including Black Americans, indigenous populations, and immigrants; however there was a particular fear rooted in and around white mountain migrants In 1934, Wayne State crafted a survey asking what respondents what population they consider most “undesirable” in Detroit. The results were telling: “poor Southern Whites (“hillbillies”) came in second, just behind “criminals ” For as much discrimination and hatred was projected onto African Americans during the turn of the 20th century, “negroes,” as the survey wrote, were ranked fourth, revealing something uniquely distressing about Appalachians for urban centers 22

In 1958 Harper’s Magazine published an article by future city commissioner Albert Votaw entitled “The Hillbillies Invade Chicago.” Votaw collected impressions of these Appalachian migrants from community stakeholders: "In my opinion they are worse than the colored,’ said a police captain ‘They are vicious and knife-happy They are involved in 75 percent of our arrests in this district.’ ‘I can't say this publicly, but you'll never improve the neighborhood until you get rid of them,’ commented a municipal court judge ”23 Votaw himself, a quaker by birth, writes: “Clannish, proud, disorderly, untamed to urban ways, these country cousins confound all notions of racial, religious, and cultural purity”24 It is important to note that many have looked into these claims of lawless, violent, murderous “hillbillies,” and found very little to sustain the sensationalistic reports around them. “In Uptown, however, southern whites did account for a significant number of arrests Although precise figures were not available, it was estimated that southern whites made up about 20 percent of the population in the Town Hall district and accounted for 35 percent of all arrests in 1960. Twenty-three per-cent of those arrested were from four states: Alabama, Kentucky, Tennessee,and West Virginia However, the author of the report advised against generalizations, noting that most arrests were for disorderly conduct and intoxication.”25

It is clear from these reports that the template for the mountain monster was being fleshed out in detail during this time by journalists, and then reinforced by reporters, law enforcement, city commissioners, and investigators, among others The image of Appalachians

21https://wwwchicagomag com/city-life/january-2012/chicagos-hillbilly-problem-during-the-great-migration/

22 https://wwwmodeldmedia com/features/hillbilly-highway-110716 aspx

23 Votaw, Albert N , THE HILLBILLIES INVADE CHICAGO , Harper's Magazine, 216:1293 (1958:Feb ) p 64

24 Votaw, Albert N , THE HILLBILLIES INVADE CHICAGO , Harper's Magazine, 216:1293 (1958:Feb ) p 64

25 https://journals sagepub com/doi/10 1177/009614420002600303

tainting the “purity” of urban progress through their animalistic nature, their misleading “whiteness,” and their violent, irrepressible compulsions will all come up again in the examination of Deliverance, and the hillbilly horror media that succeeded it In other words, mountain monsters were not a concept created for film, but rather translated onto film in a way that brought to life their damning public perception throughout the Great Migration One of the most paradoxical elements of this examination comes with the parallel popularity of hillbilly sitcoms, which dominated network TV outlets at the same time these horrifying accounts were circulating throughout regional publications What explanation can account for the fact that the very people urban audiences claimed to revile and fear, were also the ones they crowded around their living rooms to watch? The answer can be found, again, through an examination of horror

CHAPTER 2: URBANOIA AND HILLBILLY TV

One of the most foremost reasons why audiences enjoy the horror genre, is the ability to embody a narrative outside of one’s lived experience The “final girl” construction, where one heroine is left standing victorious after defeating the resident “monster,” resonates with audiences who want to feel that same sense of redemption over threats of evil In many ways, The Beverly Hillbillies, and media like it, accomplished this for urban audiences At a time when fear of a foreign “threat” was rampant across sensationalistic news reports, viewers enjoyed a voyeuristic look at the “sanitized” hillbilly to overcome their urbanoia The sanitized hillbilly reinforced urban superiority while also generating nostalgia for a simpler way of life From scholar Anthony Harkins, “The Beverly Hillbillies, and to some degree all sitcom mountain folk, resonated with audiences precisely because these shows captured the dialectical relationship between the noble mountaineer and the farcical and base hillbilly at a time when real mountaineers were much in the news.”

26 The mountain monster of 21st century media is an amalgamation of the inflammatory descriptions of Appalachians throughout the Great Migration, and many of the characteristics present in these sitcoms, which rendered hillbillies impotent figures as opposed to sincere threats While examples are countless, there are several whose ramifications for contemporary representations have had significant staying power, beginning with Paul Webb’s The Mountain Boys.

THE COMIC STRIPS

26 Harkins, Anthony Hillbilly : A Cultural History of an American Icon, Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2005 ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral proquest com/lib/kentucky-ebooks/detail action?docID=3052414 Created from kentucky-ebooks on 2025-05-16 16:34:36

https://classic esquire com/article/1940/6/1/through-hell-and-high-water-with-the-mountain-boys

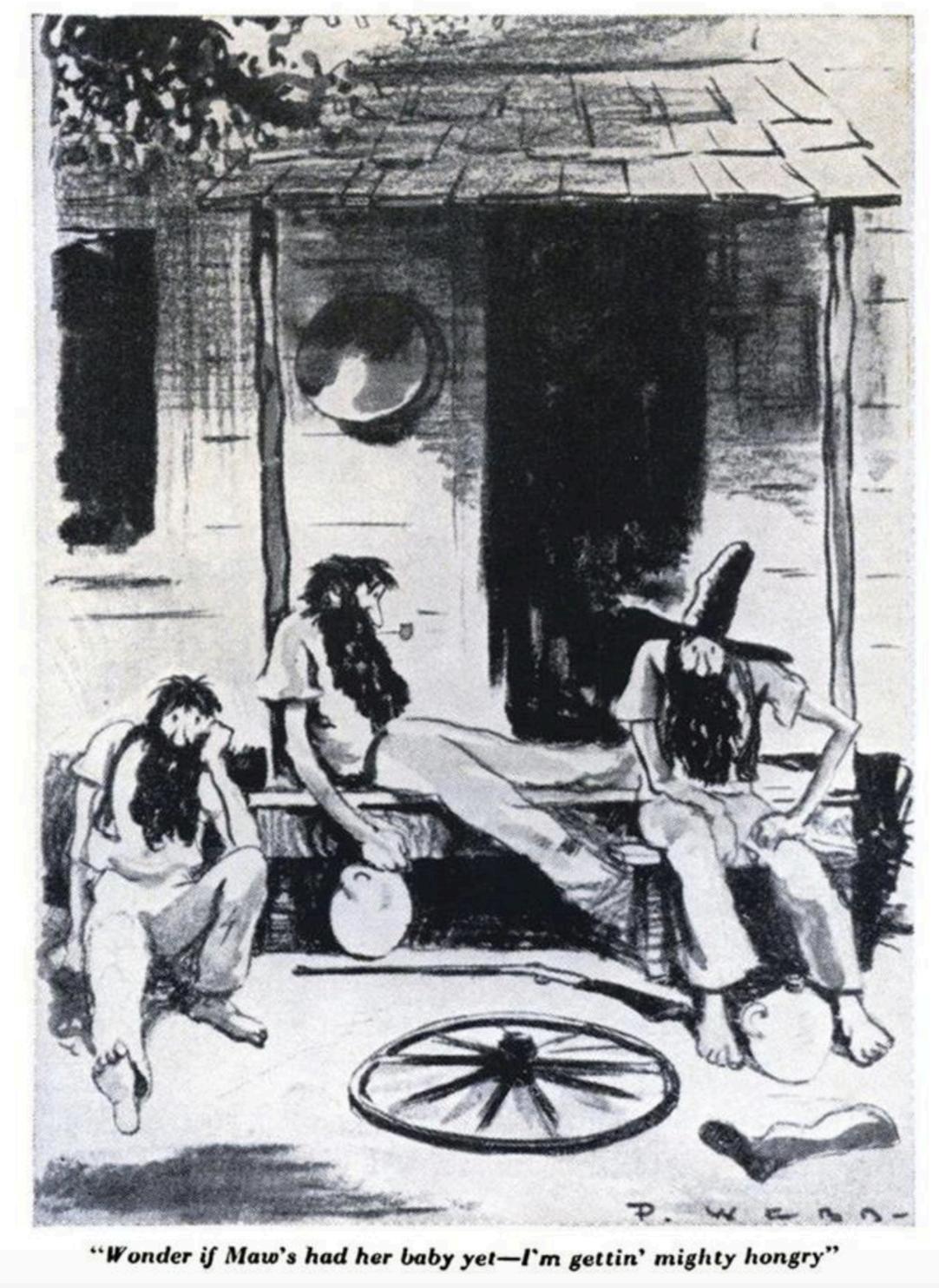

Webb’s Mountain Boys comic premiered in November 1934 in popular men’s magazine, Esquire. The debut featured a single frame with three men lazing about on a porch. The men have long hair and unkempt beards They’re surrounded by moonshine jugs, posing before an overturned wagon wheel and a single boot in the foreground The caption reads, “Wonder if

Maw’s had her baby yet I’m gettin’ mighty hongry,”27 While contemporary audiences familiar with the mountain monster may read this as a nod toward cannibalism– that particular trope wouldn’t emerge until later in the 1970s with The Hills Have Eyes (1977) Cannibalism aside (for now), the caption is intended to humorously emphasize the inherent laziness of the hillbilly men. Webb was careful to illustrate that they have the resources for productive, agrarian labor (boot, wagon wheel, gun), but are choosing to ignore them in lieu of reclining on the porch and waiting for the matriarch to prepare a meal for them, despite having just given birth. A parallel approach can be seen eight five years later in Swift’s video, where the “savage” Appalachians are choosing to eschew their responsibilities (abandoned tractor, farm equipment) in favor of wielding homophobic signs and menacing Taylor and her friends. Harkins writes:

“Through the words and (in)actions of his three nearly identical Tolliver brothers (Luke, Willy, and Jake), and their family and neighbors, Paul Webb presented endless variations on the standard tropes that defined hillbillies throughout popular culture: social isolation, physical torpor and laziness, unrefined sexuality, filth and animality, comical violence, and utter ignorance of modernity Although all familiar ideas, Webb’s portrayal was novel in the sense that such negative qualities were not offset by a correspondingly mythic vision of these folk as rugged pioneers, the inheritors of a proud Anglo-Saxon cultural heritage ”28 [ ] Webb’s cartoon was also a visual manifestation of a powerful new myth of southern society and culture that developed in the 1920s and 1930s, what historian George Tindall later labeled ‘the Benighted South,’ a society characterized by a degraded culture, oppressive economic and political institutions, staggering inequality, and widespread poverty. Challenging the long-standing view of an idyllic antebellum society of stately plantations and cultural sophistication, this reconceptualization was one result of a much broader struggle over the nature of modern America that was part of the shift from a country grounded in localized commerce and social relations to one characterized by mass production and consumption ”29

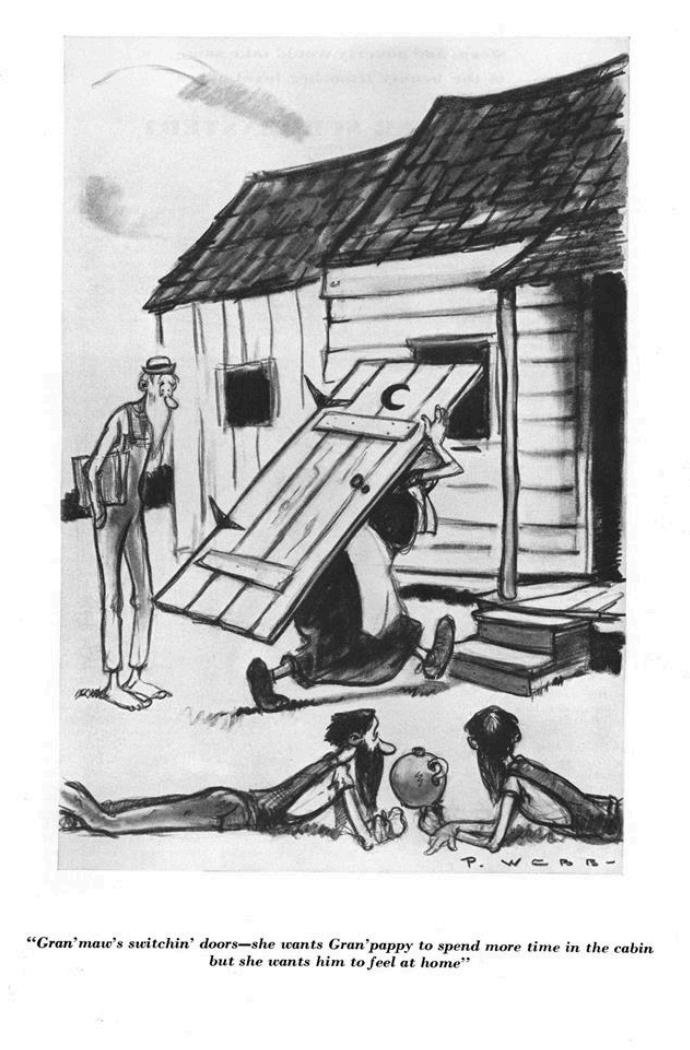

Another notable Webb comic shows two of the “boys” in the foreground with a moonshine jug between them Behind them is the family matriarch carrying a door over her head with the characteristic outhouse crescent moon shape on it Her husband, standing barefoot and holding a paper, is watching her carry this heavy door, with a caption that reads, “Gran’maw’s switchin’ doors–she wants Gran’pappy to spend more time in the cabin but she

27 Harkins, Anthony Hillbilly : A Cultural History of an American Icon, Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2005. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral proquest com/lib/kentucky-ebooks/detail action?docID=3052414

Created from kentucky-ebooks on 2025-05-16 16:51:03.

28 Harkins, Anthony Hillbilly : A Cultural History of an American Icon, Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2005 ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral proquest com/lib/kentucky-ebooks/detail action?docID=3052414

Created from kentucky-ebooks on 2025-05-20 19:19:02

29 Harkins, Anthony Hillbilly : A Cultural History of an American Icon, Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2005 ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral proquest com/lib/kentucky-ebooks/detail action?docID=3052414

Created from kentucky-ebooks on 2025-05-21 17:27:16

wants him to feel at home ”30 The inference here, that their grandfather spends the majority of his time in the outhouse, further reinforces the primitive nature of these caricatures. As Harkins alluded to–Mountain Boys dispenses with any invocation of the “noble frontiersmen” and instead leans fully into the notion of Appalachians as slovenly, uncivilized people. Another important feature: the idea of women as being dominant toward the men At the time of these publications, men were still very much expected to be acting as the head of their households–so the continual reinforcement of the “granny” figure as the one in charge reinforced the emasculation of hillbilly men Women were not only pictured as working (often while men lazed around), but they were physically larger in stature as well, frequently dwarfing their husbands in these caricatures. Finally, much of the comic emphasizes the continual “breeding” of these mountain families One of the comics shows the three “boys” on the porch with a baby on the ground in front of them The caption reads “That’s yer Oncle Rafe–Grand’maw jest had ‘im the other day.”31 The seemingly endless fertility highlighted in Mountain Boys and comics like it led to further cultural othering for Appalachians and would be reflected in several more similar publications that would succeed Webb’s. More than anything, Webb’s comic gave permission to readers to discard the seemingly obligatory nod to the hard manual labor of the South Baltimore Sun columnist H L Mencken was instrumental in this transition: Mencken’s simian references, suggesting that the hill people were not only uncivilized but also evolutionarily less advanced than urban Americans, mirrored contemporary ‘scientific’ studies of mountain backwardness, most notably Mandell Sherman and Thomas Henry’s Hollow Folk (1933). A study of five communities in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains, its authors conceived of this work as an effort to trace ‘the human race on its long journey from primitive ways of living to a modern social order.’ Focusing especially on what they considered the least advanced community, Colvin Hollow, they describe a place of sheer animality and squalor, where a six-month-old infant, his face ‘covered with flies,’ lies on a ‘bed of dirty rags’ that ‘had not been ‘changed’ since he was born.’ Although later scholars have challenged the preconceptions and methodology of this study, this supposedly scientific account reinforced widely accepted ideas of mountaineer wildness.32

30 https://classic esquire com/article/1940/6/1/through-hell-and-high-water-with-the-mountain-boys

31 https://classic esquire com/article/1940/6/1/through-hell-and-high-water-with-the-mountain-boys

32 Harkins, Anthony Hillbilly : A Cultural History of an American Icon, Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2005 ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral proquest com/lib/kentucky-ebooks/detail action?docID=3052414 Created from kentucky-ebooks on 2025-05-21 17:37:34

https://classic.esquire.com/article/1938/8/1/a-flight-of-fancy

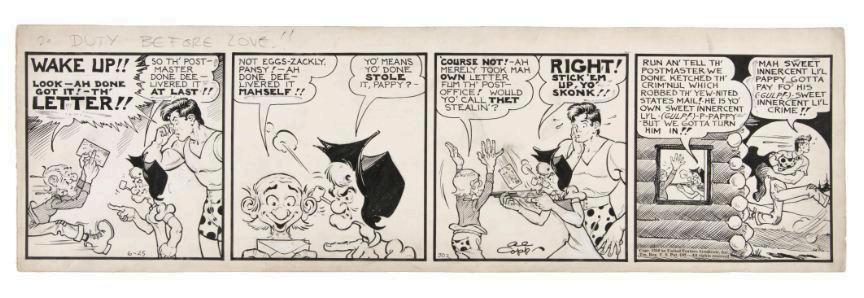

In addition to The Mountain Boys, 1934 brought the introduction of comic book character Snuffy Smith. Initially a supporting character in Billy DeBeck’s Barney Google, “DeBeck read dozens of nineteenth- and twentieth-century novels and nonfiction books about the hill folk and his debt to earlier fabricators of southern Appalachia and the mountaineer is obvious He was strongly influenced by the works of Mary Murfree and George Washington Harris, and his copy

of Sut Lovingood is liberally annotated and includes his preliminary sketches of Snuffy Smith ”33 Building off of Washington Harris and Webb, audiences saw familiar tropes of the hillbilly fool in the cartoon moonshiner Scholar Tim Hollis writes “Google encountered the sawed-off moonshiner Snuffy Smith; Snuffy’s gargantuan wife, Lowizie; and the other backwoods denizens of their home turf, Hootin’ Holler The preliminary research undertaken by the strip’s creator, Billy DeBeck, has led comics historians to deduce that he had decided to permanently change the focus of his strip from Barney’s world as a racehorse owner—that is, if his lethargic steed, Spark Plug, counts as a racehorse to a more or less authentic mountain setting ”34 Indeed Snuffy’s wife, Lowizie, is much larger in stature and is aesthetically reminiscent of the grandmother figure in The Mountain Boys. Snuffy himself is rambunctious, uneducated, quick to threaten violence, yet, still very much a “sanitized” version of the newspaper reports of the “jungle” hillbilly He can be seen frequently with his squirrel gun and a moonshine jug, always ready to assuage the fears of urban readers and reinforce that the mountains, and their inhabitants, were a source of comedy, not fear

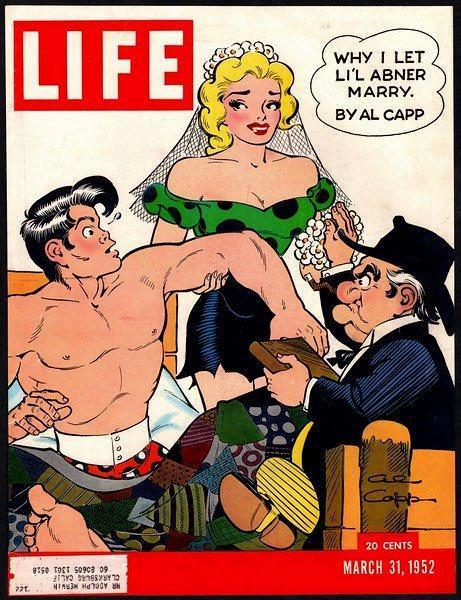

1934 wouldn’t be complete without the third, and perhaps most famous hillbilly comic strip ever conceptualized: Li’l Abner

“At the height of its popularity in the 1940s and 1950s, Li’l Abner was carried by nearly 900 newspapers in the United States and another 100 abroad a combined circulation of sixty million that helped make Capp the highest paid cartoonist of his day (estimated in 1947 at $250,000 annually) Capp’s cartoon appeared on the covers of Life and Time; launched the national phenomenon of Sadie Hawkins Day dances; spawned a Broadway musical, two films, and a theme park; and proved wildly popular with both average newspaper readers and the intellectual elite.”

35 The comic focused on the Yokum family and their life in Dogpatch, Kentucky. Thomas Inge writes, “Dogpatch became a kind of fantasy community [ ] The name Dogpatch, in fact, has entered our vocabulary as any community that is hopelessly backwards in its culture, economy, and attitudes ”36 Unlike the brothers in Webb’s comics, the titular character in L’il Abner was laughable, yet wholly endearing to readers The juxtaposition between his large physical presence and his almost nonexistent intellectual capabilities was humorous and appealing. If Snuffy was an attempt at a sanitized hillbilly figure, Abner was its peak Unlike Capp’s predecessors, the size differences between the “granny” figure and the men is reversed, though she still remains the matriarch for the family. This will have relevance as the horror genre begins

33 Harkins, Anthony. Hillbilly : A Cultural History of an American Icon, Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2005 ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/kentucky-ebooks/detail.action?docID=3052414. Created from kentucky-ebooks on 2025-05-21 17:39:23

34 Hollis, Tim. Aint That a Knee-Slapper : Rural Comedy in the Twentieth Century, University Press of Mississippi, 2008 ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/kentucky-ebooks/detail.action?docID=534340. Created from kentucky-ebooks on 2025-05-21 17:56:33

35 Harkins, Anthony Hillbilly : A Cultural History of an American Icon, Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2005 ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral proquest com/lib/kentucky-ebooks/detail action?docID=3052414

Created from kentucky-ebooks on 2025-05-21 18:46:43

36 Inge, M Thomas “Sut, Scarlet, and Their Comic Cousins: The South in the Comic Strip ” Studies in Popular Culture, vol 19, no 2, 1996, pp 153–66 JSTOR, http://wwwjstororg/stable/41970276 Accessed 21 May 2025

to emerge Abner also saw the introduction of what would become a hallmark of hillbilly representation throughout both sanitized and horror representations: the “Daisy Duke” figure. Daisy Mae Scragg is a heartsick buxom blonde forever set on marrying Abner Their relationship evolves alongside the comic strip with their wedding eventually landing the cover of Life magazine

https://hakes-wwws3 us-east-005 backblazeb2 com/images/items/61000/61826 1 2 jpg

https://www.cbr.com/superman-lil-abner-al-capp-crossover/

HILLBILLIES ON TV

The popularity of hillbilly comic strips was certainly reflected across television screens throughout America The Beverly Hillbillies, Hee Haw, The Real McCoys, and the Andy Griffith Show all capitalized off of the popularity of the hillbilly motif, but this time, in the center of the family home as a shared experience Douglas Kellner summarizes this point from television theorist Horace Newcomb: “television is ‘the most popular art:’ a form of storytelling which presents narratives that orient people toward contemporary social reality, that articulate and help resolve conflicts, and that provide a steady stream of social commentary on existing society Its defining features, according to Newcomb, are intimacy, continuity, and history Television is usually watched in the intimate setting of the family home or with close friends, and its figures likewise become home companions ”37 Indeed these sanitized, rural icons would become household names throughout the next decade, providing comfort, conflict resolution, comedic relief, and a window to a “simpler” time From Hollis:

“Those sophisticated types who thought the country was going to the pigs with all the rural humor that had taken place over the years could only scream and gnash their teeth after the 1960s arrived Television was about to experience the biggest hillbilly explosion since Snuffy Smith’s still blew up, and it all started almost imperceptibly on the ABC network in October 1957 The Real McCoys documented the experiences of a family of hill folk who migrated to the more prosperous lands of the West Coast or, as the theme song described it, ‘From West Virginny they came to stay in sunny Californi-ay.’”38

The opening scene of the pilot episode of The Real McCoys (1957-1963) shows the family loaded up on their jalopy, ready to head to California from West Virginia They soon see a police officer pull up behind them, prompting a blustering defensiveness from the patriarch, Grandpappy Amos: “...not so far [from West Virginia] that we don’t know our rights! We’re property owners, taxpayers, and legal residents of this here state of California!” The officer gently replies, letting them know that the reason he stopped them was simply to return the tire that had fallen off a few miles back. The scene is resolved with laughter and the family continues on their way This initial scene almost immediately neutralized the fears of urban audiences. For them, Appalachians distrusted authority and had a propensity for violence–but this confrontation is resolved with a laugh and mild-mannered conversation Right away, audiences are clued in to the fact that these are not the hillbillies from the pages of Norma Lee Browning–these hillbillies are funny, wholesome, and patriotic.

37 https://wwwjstororg/stable/432310

38 Hollis, Tim Aint That a Knee-Slapper : Rural Comedy in the Twentieth Century, University Press of Mississippi, 2008 ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral proquest com/lib/kentucky-ebooks/detail action?docID=534340 Created from kentucky-ebooks on 2025-05-22 12:45:10

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hh4rJbJ0SKE

Similarly, The Beverly Hillbillies’ (1962-1971) opening scene opts into this same approach. The series opens with the patriarch walking into his quaint cabin, rifle-in-hand (a far cry from the unclaimed guns littered throughout the Mountain Boys cartoons) He hangs his hat and coat and then immediately goes to the sink to wash his hands Right away audiences are shown that this is not a filthy, animalistic hillbilly, but a decent, hard-working frontiersman who takes pride in his work The granny figure is mending clothes and soon the “Daisy Duke” figure comes in wielding an unsuspecting urban surveyor over her shoulder. The subversion of power lends comedic relief, but not necessarily at the expense of the “hillbillies ” Scholar Horace Newcomb writes:

“Inevitably the plots of the show revolve around a deep conflict of basic values Their world, the part of it that is located in California, is filled with the greedy, with swindlers and crooks and good people blinded by the dazzle of the hillbilly fortune. All these people are out to somehow obtain the Clampetts' wealth To them the Clampetts are not merely ignorant of the amount of their money, but of its meaning as well The hillbilly does not use his money in an acceptable fashion. Why, when they have the means to do otherwise, do they insist on eating, dressing, and behaving as simply as they do Indeed, they are often conned into purchasing the classic images of American suckerdom: the Brooklyn Bridge, the White House, Manhattan Island Or they are tricked into investing in schemes that are patently worthless to all but the swindler But such events are never allowed to define the equilibrium of the show. Invariably, the simpler values of the

Clampetts win out over the morally deficient swindlers What appeared to be simple mindedness turns out to be deep wisdom simply expressed. Those good people who were momentarily misdirected by greed learn their lesson and become believers in the virtues of the Clampett morality. Granny's superficial jokes become keen ways of seeing the complexities of the world ”39

If these sitcoms were showcasing a wholesome, good-natured side of the displaced Appalachian, could that potentially be a good thing for mountain migrants? While these shows were enthusiastically embraced, even occasionally by Appalachians, they perpetuated damaging legacies. First, these shows did not translate to more accepting behavior toward mountain migrants This will be further explained in Chapter 3 Other damaging legacies include the idea of Appalachians as simple-minded, particularly as it relates to larger physical bodies Newcomb writes, “...producers seem to be working a refrain on "bigger is dumber."40 This has relevance later for our mountain monster prototype Additionally, many scenes throughout these comic strips and sitcoms take place outside of the domestic space. This idea of mountain families being more at home outside, or the rural landscape being their “natural environment” confirmed, in many cases, the inability of migrants to be “domesticated ” Their need to “roam” can be satiated in a TV set, but not in a lived, urban environment.

https://wwwimdb com/title/tt0512477/mediaviewer/rm2453832449/

The Andy Griffith Show (1960-1968) has perhaps the best visual evidence for how these sitcoms were actually doubling down on the bias against Appalachian people, rather than effectively mediating their perceived “otherness ” The show, which followed the small town life of

39 https://wwwjstororg/stable/40932731

40 https://wwwjstororg/stable/40932731

widower and Sheriff, Andy Taylor, featured two mountain foils: Briscoe Darling and Ernest T Bass. John Otto explains, “Briscoe Darling and his family were superstitious but sober and honorable They farmed, lived in a log cabin, and sang traditional ballads, as the plain folk had once done. Ernest T. Bass, on the other hand, was the very embodiment of the negative ‘hillbilly’ stereotype He was poor, lazy, and dissolute Ernest T searched vainly for a woman to share his squalid life; and when frustrated, Bass howled in the streets, broke windows, and disrupted the peaceful town life of Mayberry, North Carolina.”41 In season 4, episode 5, “Briscoe Declares for Aunt Bee,” we see Mr Darling being taught table manners He initially inhabits the hillbilly hallmark of lack of domestication, but is, to put it clearly, “trainable ” Aunt Bee asks him to pass the potatoes and he proceeds to take the wooden spoon, full of mashed potatoes, and pass it around among the table Aunt Bee corrects him, reminding him to pass the bowl The dinner goes on like this, with Aunt Bee reminding Mr Darling at nearly every step to be mindful of traditional table etiquette. Ernest T Bass undergoes a similar attempt at assimilation later in season 4, during episode 17, “My Fair Ernest T Bass ” The episode is a spin on the classic My Fair Lady where a sophisticated man attempts to change the dress and speech of a peasant woman to pass her off as a learned lady The episode begins with Ernest in prison after wreaking havoc at a society party In the vein of Aunt Bee, Andy tries to teach him table etiquette, but his animalistic behavior proves more difficult than Mr. Darling’s. He throws a roll at a child, regularly wipes his nose with his hand, and seems totally unable to adapt to a meal inside of a domestic space

At the end of the episode, Ernest has to be physically thrown out of a society event and remarks, “Bachelor life ain’t too bad if you get enough chipmunks and squirrels to move in with you.”42 Despite his behavior, a young woman follows him out of the party and expresses interest in courting him. At the end of the episode, Sheriff Andy and Deputy Barney Fife are remarking on how incredible it is that someone is actually pursuing Ernest T Bass Barney comments, “Now what would cause a quiet, sweet, demure girl to suddenly go ape? I mean she comes from a respectable family The Ancrum Charcoal Company has been in business for years!” Andy replies, “Well you’re getting close she’s the granddaughter of ‘Rotten Ray Ancrum ’ Come down out of the hills in 1870 and burnt the town down.” Barney replies, “You see? Blood will tell, breeding will out ”43 Harkins summarizes: “Although he continually tries to fit into society and social institutions different episodes portray his effort to join the army, to mingle at a formal reception, and to gain a primary-school education his every encounter with civilization inevitably proves disastrous and each episode closes with Sheriff Taylor hastening him back to the mountains hoping he will not return.”44 This dichotomy between these two characters is a telling summary of the anecdote many prescribed to the problem of Appalachian migration: either learn to assimilate to urban ways, or go back to the mountains Even Albert Votaw identifies this in his scathing take on mountain migration writing, “The focus of any program

41 https://wwwjstororg/stable/40920908

42 Andy Griffith Show season 4 episode 17

43https://wwwpeacocktvcom/watch/playback/vod/GMO 00000000498084 01/cc025511-2f63-3f15-aff0-f9 ff72348909?paused=true

44 Harkins, Anthony Hillbilly : A Cultural History of an American Icon, Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2005 ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral proquest com/lib/kentucky-ebooks/detail action?docID=3052414 Created from kentucky-ebooks on 2025-05-22 14:58:11

must be to prod the newcomers to help themselves [ ] The few who have come from cities are ripe for assimilation and critical of the rural folk, particularly of the mountaineers.”45 In other words, these sitcoms did not offer up a fresh take on the image of the Appalachian migrants–they simply reinforced them. If Mr. Darling could adapt, then why couldn’t their neighbors? Why couldn’t the Ernest T Basses of urban centers realize their inability to be domesticated and, like the character, go back home to the mountains where they “belong?”

The popularity of the hillbilly icon in the mid-20th century cannot be overstated. Paul Webb’s Mountain Boys were used to sell Barbasol shaving cream The popular soda “Mountain Dew”– a well known moniker for mountain moonshine, used a character known as “Willy the Hillbilly” in their advertising campaigns. The antics of Ma and Pa Kettle were household staples. Even the Clampett family from The Beverly Hillbillies was used widely in advertising Several lasting stereotypes emerged during this era including the hillbilly’s inability to adapt to the domestic space. The Daisy Duke figure would become a well-known component of rural Southern representations, and would be seen even decades later in dramatized television shows like Ava Crowder in FX’s Justified (2010-2015) and G'Winveer Farrell in WGN’s The Outsiders (2016-2017) There was a heavy association with pigs throughout nearly all of comic strips and advertising, which will be especially relevant for the development of the mountain monster (more on this in Chapter 5). Li’l Abner had a pet pig, “Salomey,” and Snuffy Smith was often shown tending to the pigs There were pigs present in Mountain Dew advertising and “hawgs” in the Mountain Boys As previously discussed, laziness was a through line, as was a lack of shoes, patchwork clothing, overalls, and the matriarchal, overbearing “Mamaw” figure. Dialectically, the speech patterns of these sources varied, but many put little to no effort into authentic representation of Appalachian dialects. Linguist Kirk Hazen explains, “[...]media representations rarely put in the effort to get the complex patterns of Appalachian dialects right. Instead, they’ll use clothing and one or two dialect features like a-prefixing (‘They were a-running’) and the demonstrative ‘them’ (‘He ate them apples yesterday’) to create a broadly sketched, stereotypical portrait These stereotypes have become so pervasive that they occur in nearly every portrayal of Appalachia ”46 An affinity for moonshine, unfounded pride, and a tendency toward violence were elements that brought comedic relief in comic strips and sitcoms, but would evolve into dangerous characteristics in succeeding dramatic representations

The hillbilly “craze” didn’t simply end with the conclusion of these pop culture mainstays. With increased technological capabilities and the seemingly endless involvement with the Vietnam War, television networks were turning their attention toward “escapism” programming. I Dream of Jeannie (1965-1970), Gilligan’s Island (1964-1967) and Bewitched (1964-1972) all began to replace the rural comedy of the preceding decade Could the hillbilly fool have remained forever confined to the pages of comic books and black and white television screens? It is unlikely A significant movement was brewing alongside the antics of Snuffy and Abner: The War on Poverty At the same time urban audiences were finding relief in the sanitized take on Appalachian migrants, others were developing real concern for the plight of these hardworking Americans Appalachians themselves were also pushing back: urging citizens and councils to make room for newcomers and break down cultural barriers When individual efforts weren’t

45 https://acloudofdust typepad com/files/hillbillies-invade-chicago pdf

46 https://wwwproquest com/docview/2721404023? oafollow=false&sourcetype=Magazines

enough to spur large-scale change, many tried to sound the alarm from within the Appalachian region. If urban centers were so desperate for Appalachians to go back to the mountains, then we need to collectively find a way to make the mountains worth going back to, economically speaking. This culminated into a call to action from the highest level of government, one that many were unwilling and ill equipped to take on, as the nation had just emerged from the Great Depression and many felt they were beginning to find solid footing again for the first time Sobering black and white images, a national campaign, and a series of revealing non-fiction texts collectively began to drown out the laughter and call American’s attention to the reality in Appalachia America

CHAPTER 3: THE WAR ON

POVERTY

CHRISTMAS IN APPALACHIA

Picture this: it is December 1964, four days before Christmas You’re in the family living room with the colorful glow of the Christmas tree lights reflected in the shiny presents wrapped underneath You’re finishing up an episode of The Ed Sullivan Show, or maybe a repeat of The Twilight Zone 10:00 pm rolls around and you hear the familiar voice of journalist Charles Kuralt emanating from the black and white screen, as the camera pans across a holler in Letcher County, Kentucky Kuralt remarks that, along the road he is walking, lie the “shacks of tar paper and pine, which are the homes of a million permanently poor.”47 Kuralt goes on to describe the harrowing journey that the children of these mountains take to get to the one-room schoolhouse every day Perhaps at this point you remember the comics you used to read in your dad’s copy of Esquire. Your first impulse might be frustration, as you think of how selfish it is of those fathers to allow their children to go hungry rather than finding an opportunity for work to support the family Kuralt then describes the vocation of several of these households, describing “hard working” men who are doing far more backbreaking work than you’re asked to, like digging coal from the mouth of mountains Your impulse to dismiss the dire circumstances you’re seeing as the result of Appalachian laziness suddenly becomes more difficult You then hear the voices of children singing “Silent Night” juxtaposed behind the title screen “Christmas in Appalachia.” Do the presents in the living room now suddenly appear extravagant? Does the fact that your children have separate rooms, while these families are sharing one room among thirteen people, feel indulgent? This is just one example of the cognitive dissonance that might have occurred when middle and upper class Americans were confronted with real footage of the systematic economic inequalities within the Appalachian region. The rural family sitcom and hillbilly stock characters had provided comedic relief for almost a decade, while reinforcing urban superiority; however Americans were now being shown real mountain families, with coal-dusted faces and starving children. Worse yet, the mountain men weren’t lounging on the steps drinking moonshine, or cooking up hair-brained schemes–they were doing backbreaking work for pennies on the dollar

47 CBS 1964 Dec 21

NIGHT COMES TO THE CUMBERLANDS

Would middle class audiences really be surprised that such poverty existed in America? From The New Yorker’s “Our Invisible Poor:”

“In his significantly titled ‘The Affluent Society’ (1958) Professor J K Galbraith states that poverty in this country is no longer ‘a massive affliction [but] more nearly an afterthought ’ Dr Galbraith is a humane critic of the American capitalist system, and he is generously indignant about the continued existence of even this nonmassive and afterthoughtish poverty. But the interesting thing about his pronouncement, aside from the fact that it is inaccurate, is that it was generally accepted as obvious For a long time now, almost everybody has assumed that, because of the New Deal’s social legislation and more important the prosperity we have enjoyed since 1940, mass poverty no longer exists in this country ”48

One of the first fractures in the image of post-war America as a society of large-scale affluence came from writer Michael Harrington in 1962 Harrington published The Other America which highlighted several pockets of disenfranchised areas throughout the U S , with special attention on rural Appalachia. The book did little at first to stoke the fire of the American public until Dwight Macdonald’s review in The New Yorker from 1963, firing what some would call “the first shot in the war against poverty”49 Harrington sold 70,000 copies of The Other America in the year after Macdonald’s essay was published. It even eventually made its way into the hands of John F Kennedy, igniting his advocacy for the region’s economic situation 50 The then-president would be assassinated only a few months later during a November 1963 motorcade in Texas

One of the most important things Macdonald did with his review was to draw attention to to the demographics Harrington felt were most at risk:

“These invisible people fall mostly into the following categories, some of them overlapping: poor farmers, who operate 40 per cent of the farms and get 7 per cent of the farm cash income; migratory farm workers; unskilled, unorganized workers in offices, hotels, restaurants, hospitals, laundries, and other service jobs; inhabitants of areas where poverty is either endemic (‘peculiar to a people or district’), as in the rural South, or epidemic (‘prevalent among a community at a special time and produced by some special causes’), as in West Virginia, where the special cause was the closing of coal mines and steel plants; Negroes and Puerto Ricans, who are a fourth of the total poor; the alcoholic derelicts in the big-city skid rows; the hillbillies from Kentucky, Tennessee, and Oklahoma who have migrated to Midwestern cities in search of better jobs And, finally, almost half our ‘senior citizens.”51

Macdonald concludes his lengthy review with a proposed solution to problems Harrington outlines writing: “The problem is obvious: the persistence of mass poverty in a prosperous

48 https://wwwnewyorkercom/magazine/1963/01/19/our-invisible-poor

49https://wwwsmithsonianmag com/history/how-a-new-yorker-article-launched-the-first-shot-in-the-war-ag ainst-poverty-17469990/

50https://wwwsmithsonianmag com/history/how-a-new-yorker-article-launched-the-first-shot-in-the-war-ag ainst-poverty-17469990/

51 https://wwwnewyorkercom/magazine/1963/01/19/our-invisible-poor

country The solution is also obvious: to provide, out of taxes, the kind of subsidies that have always been given to the public schools (not to mention the police and fire departments and the post office) subsidies that would raise incomes above the poverty level, so that every citizen could feel he is indeed such.”

52 The direct, and indirect criticism of the Kennedy administration throughout Macdonald’s essay finally caught the attention of lawmakers and government officials, who were further encouraged by the 1963 publication of Night Comes to the Cumberlands: A Biography of Depressed Area by Harry Caudill.

https://wwwkentuckycom/news/special-reports/fifty-years-of-night/article44393733 html

Caudill was born in Letcher County, Kentucky–the same area that Christmas in Appalachia would explore in the December 21st documentary After serving in World War II and earning his law degree at the University of Kentucky, Caudill returned to the mountains to open his own law practice, later serving two terms in the Kentucky House of Representatives.53 Caudill was, by all accounts, a voracious writer who was particularly motivated when it came to creating better understanding around the issues in Appalachia. The one-time Director of the Appalachian Center at Berea College, Loyal Jones, writes of Night Comes to the Cumberlands, “In the 1960s, Harry Caudill was the only person in the coalfields with the intellect, perseverance, courage, and anger too, to do that book. Harry's mixture of Old Testament and nineteenth-century lawyer's rhetoric and outrage rolled majestically from its pages One gauge of the book's importance was that Alfred H Perrin, a bookman if there ever was one (then director of publications at Procter and Gamble in Cincinnati), bought 100 copies and asked the

52 https://wwwnewyorkercom/magazine/1963/01/19/our-invisible-poor

53 https://carnegiecenterlex org/hall-of-fame/harry-caudill/

Council of the Southern Mountains to send them to the President, his cabinet, to Appalachian members of Congress and other influential Americans.”54

JOHNSON’S WAR ON POVERTY

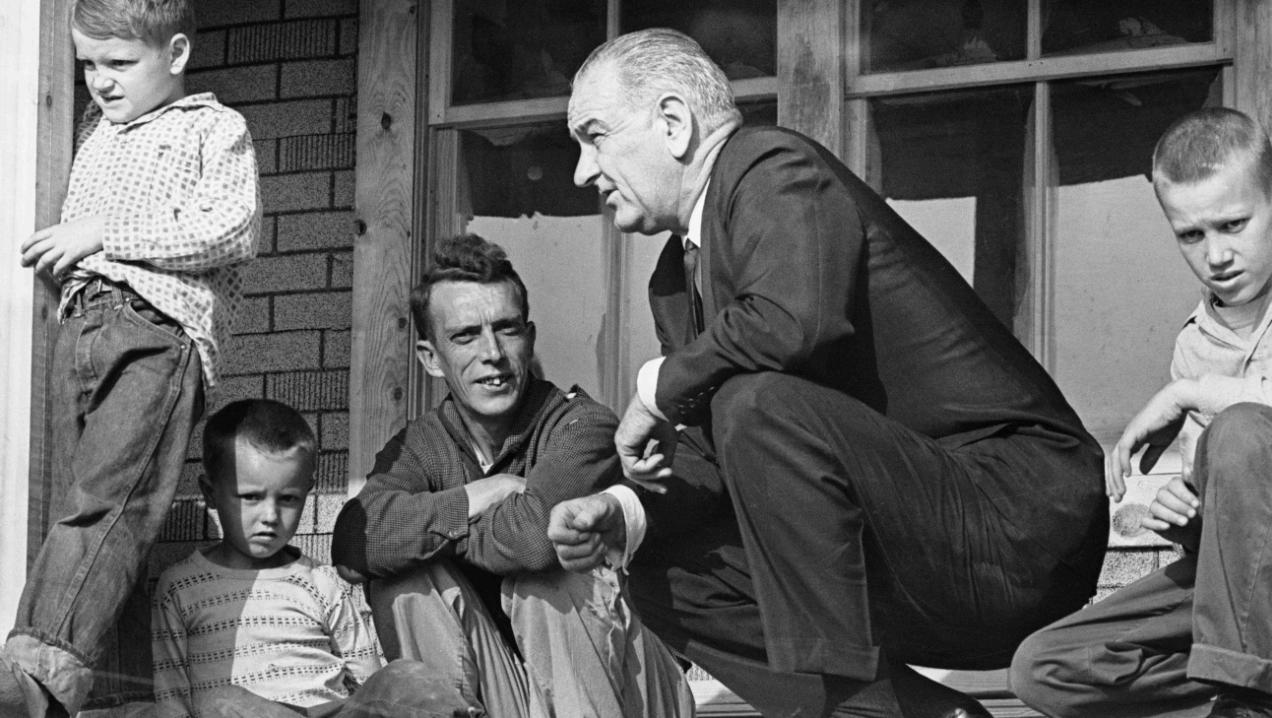

Following Kennedy’s assasination, Lyndon B Johnson was sworn in as the 36th president of the United States and continued pursuing many of the causes that Kennedy had initiated, including eradication of the poverty addressed by Harrington and Caudill On January 8, 1964, Johnson formally declared his War on Poverty: “This administration today, here and now, declares unconditional war on poverty in America I urge this Congress and all Americans to join with me in that effort It will not be a short or easy struggle, no single weapon or strategy will suffice, but we shall not rest until that war is won. The richest Nation on earth can afford to win it We cannot afford to lose it ”55 On March 16th, 1964, Johnson addressed Congress: “On similar occasions in the past we have often been called upon to wage war against foreign enemies which threatened our freedom Today we are asked to declare war on a domestic enemy which threatens the strength of our nation and the welfare of our people If we now move forward against this enemy--if we can bring to the challenges of peace the same determination and strength which has brought us victory in war--then this day and this Congress will have won a secure and honorable place in the history of the nation, and the enduring gratitude of generations of Americans yet to come.”56 The language chosen for these proclamations by Johnson was intentional His impassioned speeches emphasized that, much like the war efforts of the past, this particular movement was going to require broad participation. He spoke about “enlisting” almost synonymously with war efforts: “Among older people who have retired, as well as among the young, among women as well as men, there are many Americans who are ready to enlist in our war against poverty.”57

Many of the specific programs and congressional tools for which Johnson advocated have now faded from the public consciousness, but the photos that accompanied the movement have not. Shortly after his initial declaration in January, Life Magazine ran a 12-page feature showcasing the “Valley of Poverty” Ben Cosgrove writes, “At the time, LIFE was arguably the most influential weekly magazine in the country [ ] LIFE was in a unique position in the early days of Johnson’s administration to not merely tell but to show its readers what was at stake, and what the challenges were, as the new president’s ‘Great Society’ got under way”58 Cosgrove goes on to describe the photos as “an indictment of a wealthy nation’s indifference.”59 Near Neon, Kentucky, photographer John Dominis documented a mother holding her daughter Riva, critically ill with measles A photograph from Branch Creek shows thin walls plastered with newspaper. One of the captions of two young children reads: “The commonest sights around

54 https://muse jhu edu/article/436499/pdf Harry Caudill and Night Comes to the Cumberlands Revisited

55 https://wwwpresidencyucsb edu/documents/annual-message-the-congress-the-state-the-union-25

56https://wwwpresidencyucsb edu/documents/special-message-the-congress-proposing-nationwide-war-t he-sources-poverty

57https://wwwpresidencyucsb edu/documents/special-message-the-congress-proposing-nationwide-war-t he-sources-poverty

58 https://wwwlife com/history/war-on-poverty-appalachia-portraits-1964/

59 https://wwwlife com/history/war-on-poverty-appalachia-portraits-1964/

Appalachia were aging men and ragged urchins ”60 In an increasingly visual society, these images would contribute heavily to the mold for the horror genre’s mountain monster. The stark use of black and white, weather-worn houses, and coal-dusted faces all stoked strong reactions in viewers ranging from sympathy to fear, and even disgust. In Unwhite: Appalachia, Race, and Film, author Meredith McCaroll writes “While there are notable exceptions and opportunities to subvert a system that privileges the director, the stereotypes of Appalachia have made their way into even well-intentioned documentary films. The earliest documentary images of the region carved out a path that few filmmakers have been able to resist Drawn to the staid images of poverty, family, landscape, and brutal living conditions, documentarians have consistently shown the same Appalachia.”61 President Johnson himself embarked on what’s known as his “Poverty Tours” throughout 1964, making stops from Pennsylvania to Kentucky to address communities there and share his plans to bring relief One of the most lasting images from this time came in Martin, County Kentucky at the cabin of Tom Fletcher. Fletcher was a former sawmill operator, unemployed at the time of the now-infamous photograph Tom’s son Calvin, seen in the photographs remarked to BBC in 2014: “The president's visit was the worst thing that ever happened to the family Since then we've had nothing but people wanting to talk about that day and taking photos of this house "62

https://wwwlife com/history/war-on-poverty-appalachia-portraits-1964/

60 https://wwwlife com/history/war-on-poverty-appalachia-portraits-1964/

61 https://wwwjstororg/stable/j ctt22nmbtj 8

62 https://wwwbbc com/news/world-us-canada-29853472

https://wwwnprorg/2014/01/08/260151923/kentucky-county-that-gave-war-on-poverty-a-face-sti ll-struggles

1964 began with a State of the Union from President Lyndon B Johnson declaring a War on Poverty, and ended with the December 21st documentary Christmas in Appalachia The year was an impactful one for Appalachia, taking the well-known, loveable, hillbilly fool and turning it on its head. Only twelve years beforehand, Life Magazine featured the marriage of Li’l Abner and his “Daisy Duke” on their cover Now, the same publication was creating spreads a dozen pages long, full of gritty images from the real “Dogpatch.” Middle and upper class Americans had heard, or in some cases even seen, this kind of abject poverty in war efforts taking place abroad in faraway, exotic locations, but many couldn’t have imagined similar conditions only a few hours away. In The Invention of Appalachia Allen Batteau writes, “Following the launching of the War on Poverty, with Appalachia as the ‘first battlefield in the War on Poverty’ in 1964 and the airing of the CBS/Charles Kuralt documentary Christmas in Appalachia at the end of the same year, attention centered on the Appalachian region.”63 Batteau goes on to claim “For several years afterward, poverty warriors,planners, bureaucrats, and the publics that supported them saw Appalachia through Kuralt-colored glasses ”64

Like any public campaign, there inevitably came an expiration date on patience from the American public and government officials Readers eventually became desensitized to the influx of imagery from out of the region and even early champions of involvement efforts were beginning to flag Loyal Jones writes, “Nobody was more disappointed than Harry [Caudill] that his efforts didn't do more He was dissatisfied with the Appalachian Regional Commission for not being able to deal with absentee ownership and power production. He was critical of the

63 https://wwwjstororg/stable/j ctt22nmbtj 8

64 Batteau 1990 7 Invention of Appalachia